Text

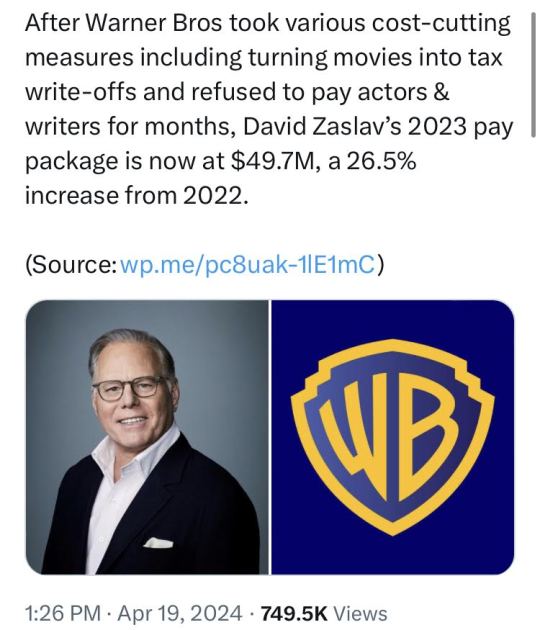

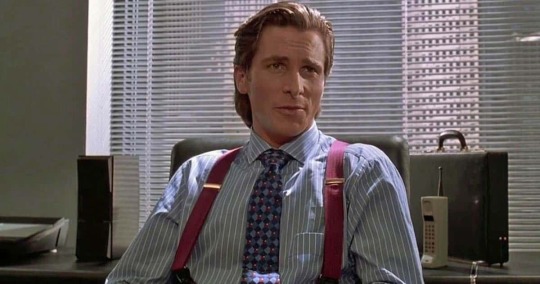

Random Thought Before Bed: My Informal Pitch for a Modernized, Mixed Media Parody of A Christmas Carol

Synopsis: Christian Bale plays Silas Croodge, a greedy, miserly, out-of-touch corporate executive that has recently acquired a popular new streaming service. In an effort to cut costs, he not only cancels several animated projects, but also completely purges any evidence that they ever existed from the internet—thus depriving their creators of royalties and residuals.

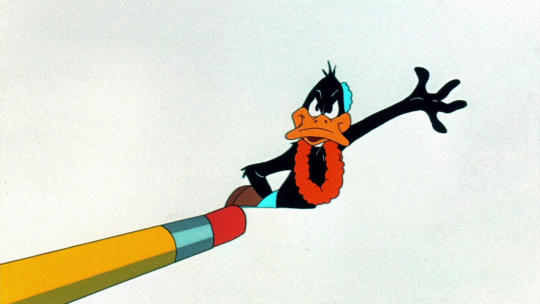

Shortly thereafter, he is haunted by a trio of cartoon ghosts. Their mission: to “scare him straight” by forcing him to confront the consequences of his actions. Will this encounter with the supernatural convince Croodge to change his wicked ways?

As it turns out, the answer is a resounding “No.” He dismisses the experience as a bizarre nightmare and immediately continues pinching pennies. Fortunately, he can’t avoid karma forever. His mismanagement of his company soon leads him to ruin: customers unsubscribe, employees go on strike, and advertisers withdraw their support en masse.

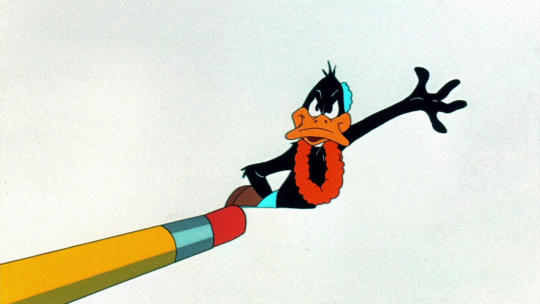

As Croodge wanders the streets in a daze—haggard, destitute, and disgraced—he curses the heavens, blaming everybody but himself for his misfortune. A giant pencil then descends from the sky and literally erases him from reality.

And everyone else lives happily ever after.

#David Zaslav#Warner Brothers#Warner Bros#WB#running out of witty commentary#just praying for the giant pencil to erase this parasite from existence

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently Viewed: Dreadnaught

[The following review contains MINOR SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

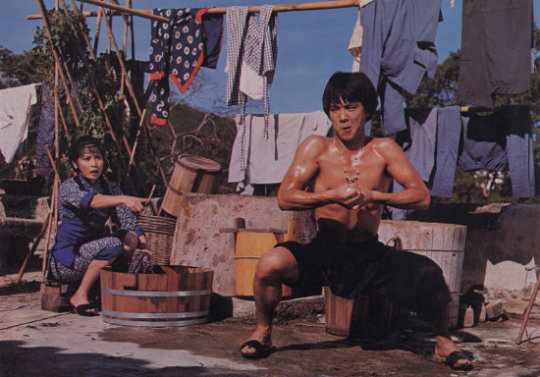

Although the Criterion Channel’s description neglects to advertise it as such, the 1981 kung-fu horror-comedy Dreadnaught belongs to Yuen Woo-ping’s loosely connected Wong Fei-hung series. Whereas the original Drunken Master featured the historical figure turned folk hero as a mischievous student (portrayed by the inimitable Jackie Chan) and Iron Monkey explored his childhood (as the son of professional badass Donnie Yen), this film depicts him as a wise old mentor—played, appropriately enough, by Kwan Tak-hing, who starred as the character in approximately seventy-seven movies (according to the notoriously reliable Wikipedia’s undoubtedly accurate count, anyway).

The plot (minimalistic as it is) revolves around Mousy, a meek, cowardly youth constantly terrorized by local thugs, corrupt cops, and… adorable puppies. Since it’s his job to collect on overdue bills for his sister’s struggling laundry business, his timid demeanor is a significant problem; thus, at the insistence of a sympathetic friend, he seeks tutelage under the esteemed Master Wong. The perceptive teacher quickly intuits that his reluctant disciple is a naturally gifted martial artist; he merely lacks the confidence required to effectively utilize his innate skills. When a convoluted sequence of events makes him the target of a deranged, bloodthirsty assassin, however, necessity might yet transform our pussycat of a protagonist into a courageous lion.

Yuen’s greatest talent lies in his ability to convey story and characterization through fight choreography, and Dreadnaught certainly delivers in that regard; every punch calls back to a narrative seed introduced in an earlier scene—a deliciously satisfying display of setup and payoff reminiscent of Edgar Wright’s Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz. During the climactic showdown, for example, Mousy discovers that his family’s trademark “two-fingered grasp” technique is useful for more than just drying clothes; his firm grip strength—developed from years of wringing out wet fabric—gives him an unexpected advantage whilst grappling with his savage opponent… until his foe simply rips off the tattered remnants of his shirt, at least.

That deft juggling of tones—effortlessly transitioning between humor and suspense—elevates Dreadnaught, compensating for its relatively superficial flaws (particularly its uneven pacing). Yuen is justifiably renowned for his contributions to The Matrix and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, but I hope that more of his work as a director becomes (legally) available in the West; while his movies may not be conventionally “prestigious” or stylistically polished (compared to those produced by, say, King Hu), they are consistently entertaining.

#Dreadnaught#Yuen Woo-ping#Yuen Woo Ping#Wong Fei-hung#Wong Fei Hung#Kwan Tak-hing#Golden Harvest#kung-fu film#kung fu film#kung-fu cinema#kung fu cinema#Criterion Channel#Criterion Collection#Criterion#film#writing#movie review

1 note

·

View note

Text

Recently Viewed - The Art of the Benshi: Program IV

When I previously wrote about benshi—the live narrators that would contextualize (and, on occasion, totally reinterpret) the silent images onscreen in the nascent days of film exhibition in Japan—in my review of Masayuki Suo’s Talking the Pictures, I never imagined that I would eventually have the opportunity to actually see one perform in person; after all, the advent of the talkie essentially rendered the profession irrelevant and obsolete. There are, however, a dedicated few working tirelessly to preserve the increasingly rare art, several of whom recently showcased their talents at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

The selection of movies screened for the demonstration was as eclectic as it was remarkable: The Dull Sword, an animated short (featuring both hand-drawn frames and paper cutouts reminiscent of Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Achmed) about a bloodthirsty samurai constantly thwarted and humiliated by hubris; The Oath of the Sword, a newly rediscovered romantic melodrama starring a predominantly Asian-American cast; and The Vindictive Snake, a moody tale of ghostly vengeance (which owes an obvious thematic debt to Yotsuya Kaidan) set in the ramshackle sugar plantations of Hawaii and the seedy brothels of Okinawa. Surprisingly, amidst these obscure treasures, the true gem of the program was a widely available Hollywood classic: Charlie Chaplin’s The Immigrant; Kumiko Omori’s energetic delivery—replete with cartoonish voice acting and charmingly silly sound effects (a squeaky toy, for example, was utilized to approximate the noise of hiccups)—enriched and elevated the familiar plot and gags, adding a fresh layer to the comedic tone. Not to disrespect or underestimate the skills of her fellow benshi, of course; Ichiro Kataoka and Hideyuki Yamashiro each displayed his own distinctive style and flavor. Indeed, the trio’s cooperative rendition of Masao Inoue’s 1916 adaptation of Not Blood Relations (or what little remains of it, anyway; like far too many productions of that era, it currently exists only in fragmentary form) was an impressive feat of theatrical collaboration.

Purchasing the ticket for The Art of the Benshi (a $20 expense that feels pretty darn substantial in the aftermath of the SAG and WGA strikes) was an extremely spontaneous decision on my part—one that I second-guessed during every excruciating moment of my forty-minute-long subway ride to the venue. Fortunately, I needn’t have fretted; the most memorable cinematic experience of 2024 was well worth the relatively paltry price of admission.

#The Art of the Benshi#Benshi#Japanese cinema#Japanese film#Japanese culture#The Dull Sword#Not Blood Relations#The Oath of the Sword#The Vindictive Snake#The Immigrant#Junichi Kochi#Masao Inoue#Frank Shaw#Charlie Chaplin#benshi#Brooklyn Academy of Music#BAM#film#writing#movie review

1 note

·

View note

Text

Recently Viewed: Ken (The Sword)

[The following review contains MAJOR SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

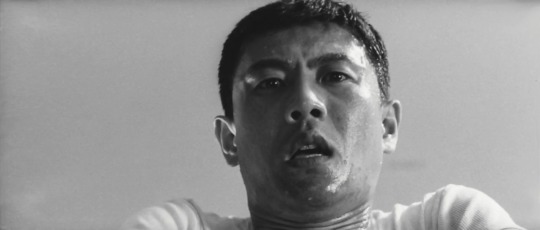

Kenji Misumi’s Ken (or The Sword, if you prefer translated titles) opens with an exquisitely crafted montage depicting excruciating physical exertion. The sun blazes blindingly overhead, shining more brilliantly than it did in Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon. Cold, steely eyes narrow with unwavering resolve. Beads of sweat glisten on the subject’s forehead, soaking the furrowed brow. Muscles tense with effort, so firm and taut that they threaten to tear the skin. And through it all, a bamboo sword slices the air, as rhythmic and relentless as the labored beating of a heart.

Such imagery recurs throughout the film. A later training sequence, for example, frequently cuts to disorienting POV shots as the characters do dozens, then scores, then hundreds of push-ups; the ground repeatedly rushes up to meet the camera, grit and pebbles blurring in and out of focus as perspiration drip-drip-drips onto the soil. Between sets, the exhausted athletes collapse, panting and thoroughly drenched; when they reluctantly rise to resume their monotonous, Sisyphean task, damp silhouettes of their bodies remain imprinted on the wooden planks of the dojo’s floor.

While they appear straightforward self-explanatory on the surface, these scenes are pregnant with deeper significance, elegantly conveying pretty much every one of writer Yukio Mishima’s thematic preoccupations via movement and action alone: his admiration of the human (masculine) physique, especially when it’s meticulously sculpted and/or strained to the absolute limits of fitness; his reverence for such “traditional Japanese values” as discipline, honor, and loyalty; his glorification of what I’ll charitably refer to as “youthful simple-mindedness” (a topic that he discusses in almost uncomfortably candid detail in Confessions of a Mask); and his obsession with the perverse, paradoxical overlap between violence and sex. Indeed, Misumi even addresses the subtextual—and sometimes blatantly, brazenly textual—homoeroticism that permeates the author’s work, staging an audacious bathhouse brawl that anticipates David Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises (albeit sans the graphic full-frontal nudity).

Of course, considering this is Mishima that we’re talking about—for further context, see Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, a sublime biopic that revolves around the controversial novelist’s very public seppuku—it’s hardly a spoiler to reveal that the movie also (somewhat regrettably) unapologetically romanticizes suicide. After the protagonist (played by Raizo Ichikawa, who personifies Mishima’s core philosophy with a cool, aloof, enigmatic stoicism) is duped into believing that he’s utterly failed in his duties as captain of his university’s kendo club, he chooses to end his life on his own terms, preserving his “purity” and “dignity” by leaving behind a corpse so angelic and radiantly beautiful that it causes spurned lovers, stern mentors, bitter rivals, and envious subordinates alike to weep tears of remorse.

Misumi’s visual style perfectly complements the melodramatic narrative. The stark black-and-white cinematography, with its deep, moody shadows, mirrors our hero’s rigid, inflexible worldview. The compositions are equally evocative: the cramped, claustrophobic framing and oppressively symmetrical blocking (which mimic the surrounding architecture) trap the characters both figuratively and literally, lending the tragic conflict a palpable atmosphere of inevitability. This bleak, somber tone distinguishes Ken as a major departure from the director’s usual fare—particularly his numerous contributions to the chanbara genre, including most of the Lone Wolf and Cub series and some of the best installments in the Zatoichi franchise—and it’s more compelling for it. Misumi was, after all, a lifelong workhorse for Daiei (alongside such esteemed contemporaries as Kazuo Mori and Kazuo Ikehiro); how delightful, then, to learn that he occasionally helmed the studio’s “prestige” projects in addition to churning out countless B-pictures.

I first discovered the existence of Ken over a decade ago, when I encountered a brief summary of its plot in the pages of critic Patrick Galloway’s essential Warring Clans, Flashing Blades, and I’ve been desperately searching for a (legal) copy ever since. I’m glad that I was able to finally experience it on the big screen—in borderline pristine 4K to boot, thanks to Janus Films’ gorgeous restoration—courtesy of MoMA. Hopefully, a home video release will follow in the near future; despite its obvious flaws, it is a story that demands multiple viewings and reevaluations.

#Ken#The Sword#Ken (The Sword)#Kenji Misumi#Daiei#Raizo Ichikawa#MoMa#Museum of Modern Art#Janus Films#Japanese cinema#Japanese film#film#writing#movie review

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Check out what arrived in the mail today!

0 notes

Text

Recently Viewed: Kenji Misumi’s Yotsuya Kaidan (1959)

[The following review contains MAJOR SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

Yotsuya Kaidan is Japan’s most popular and frequently adapted ghost story. While the core premise is basically consistent from version to version—penniless ronin Tamiya Iemon falsely accuses his wife of adultery as a pretext to divorce her and marry a wealthier woman, culminating in violence, regret, and vengeance from beyond the grave—the precise details of the narrative vary wildly between cinematic interpretations.

Shintoho’s 1959 film (helmed by Jigoku director Nobuo Nakagawa), for example, is a relentlessly dark (albeit vibrantly colorful) and bleakly cynical morality play; the protagonist is casually cruel and unrepentantly vile, with his grisly fate framed as karmic justice that the audience is intended to enthusiastically applaud. Keisuke Kinoshita’s 1949 duology, on the other hand, depicts Tamiya far more sympathetically; despite his (thoroughly reluctant) complicity in the terrible crimes committed against his spouse, he’s motivated primarily by economic factors beyond his control and the corruptive influence of his slimy, manipulative, verminous “friend,” Naosuke. Indeed, it is implied that the “haunting” is merely psychological—a subconscious manifestation of the central character’s guilty conscience. (Ironically, this “social realism” makes Kinoshita’s movie feel more subversive and revolutionary than Nakagawa’s comparatively lurid and gory effort.)

Kenji Misumi’s radically revisionist spin on the classic tale, however, probably takes the most liberties with the surprisingly malleable source material. Here, Tamiya (played by megastar Kazuo Hasegawa—which goes a long way towards explaining the particular “quirks” in his portrayal) is borderline heroic—an archetypal gruff-yet-chivalrous swordsman cut from the same cloth as Zatoichi and Tange Sazen. He’s also so passive and devoid of agency that he resembles the eponymous “specter” in Hammer’s The Phantom of the Opera, remaining virtually blameless for the (unnecessarily convoluted) series of events that result in his tragic downfall. He’s totally unaware of Naosuke’s devious conspiracy to humiliate, defame, and ultimately murder his wife, and although he still participates in an extramarital affair, the relationship appears to be purely transactional (and may not be overtly sexual; the extent of the “lovers’” physical intimacy is left deliberately ambiguous)—driven to desperation by poverty, he only indulges his mistress’ affections in exchange for money and lavish gifts. The editing, in fact, at one point explicitly juxtaposes his infidelity with that of his sister-in-law, who works part-time as a “waitress” at a “bathhouse” in order to supplement her husband’s meager income. Naturally, Tamiya’s relative “innocence” completely recontextualizes the story’s climax and denouement; whereas the character usually suffers an appropriately shameful, pathetic, undignified demise, Misumi allows him to achieve a measure of redemption via his glorious, honorable, beautiful death—sprawled at the feet of a bronze Buddha statue, wrapped in his wife’s favorite kimono, bathed in heavenly sunlight.

Pulpy, unsubtle, and unapologetically melodramatic even by Daiei’s standards, Yotsuya Kaidan isn’t the “best” adaptation of the original kabuki production, but Misumi’s various audacious departures from the “traditional” formula certainly distinguish it as one of the most interesting, unique, and undeniably compelling. For fans of chanbara and J-horror alike, it is essential viewing.

#Yotsuya Kaidan#Yotsuya Kwaidan#Ghost Story of Yotsuya#Kenji Misumi#Kazuo Hasegawa#Daiei#Japanese film#Japanese cinema#Japanese horror#J-horror#J horror#chanbara#Film Forum#chambara#film#writing#movie review

0 notes

Text

Recently Viewed: Demon Pond

[The following review contains MINOR SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

At times, Masahiro Shinoda’s Demon Pond feels like two different films awkwardly stapled together.

The first is a hauntingly atmospheric arthouse horror movie about forgotten folklore, self-destructive superstitions, and the conflict between “traditional values” and “modern rationality.” The opening montage is particularly impactful, elevated by the immaculate sound design: the oppressive howl of the scorching, dusty wind; the mocking “crunch” of parched, cracked earth underfoot; and the resounding “thud” of a stone hitting the bottom of a bone-dry well elegantly convey the borderline post-apocalyptic desolation of the setting—a remote mountain village ravaged by poverty and drought.

The second is a fairly conventional Japanese ghost story reminiscent of Daiei’s 100 Monsters and Daimajin, with all of the tropes that one would expect from the genre: morally corrupt humans desecrating the natural order, wrathful gods and guardian spirits exacting terrible revenge, cataclysms of every conceivable variety (floods, typhoons, tsunamis), and hapless innocents caught in the crossfire. Shinoda’s unmistakable authorial voice, however, enriches this familiar narrative structure. The scenes depicting the Dragon Princess’ heavenly court, for example, deliberately embrace the inherent artificiality of live theater—much like the director’s earlier effort, Double Suicide (in that case, he was emulating bunraku puppetry; here, kabuki serves as the primary influence). The relatively simple yet dazzlingly colorful makeup and costuming of the monstrous retinue—lumbering ogres, grotesque Cyclopes, wizened Shinto priests sporting fleshy catfish whiskers—reminded me of Tomu Uchida’s equally evocative The Mad Fox.

While I enjoyed each of these plots on its own merits, as a whole, Demon Pond never becomes quite as compelling as its individual components. The inconsistencies in style and tone create a sense of dissonance and disharmony; the frequent shifts between the mundane and fantastical worlds feel contradictory rather than complementary. Ultimately, it’s just a muddled, confused, incoherent cinematic experience—occasionally enjoyable, but difficult to recommend.

0 notes

Text

The message that Akira Toriyama left for his kids in Chrono Trigger

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

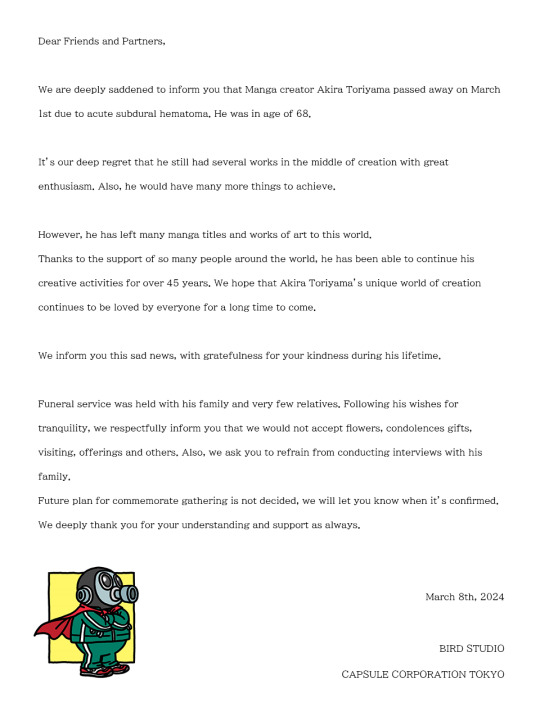

Rest in peace, Akira Toriyama.

He didn't need the Dragon Balls—his work made him immortal.

Recently Viewed - Dragon Ball Super: Super Hero

[The following review contains MAJOR SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

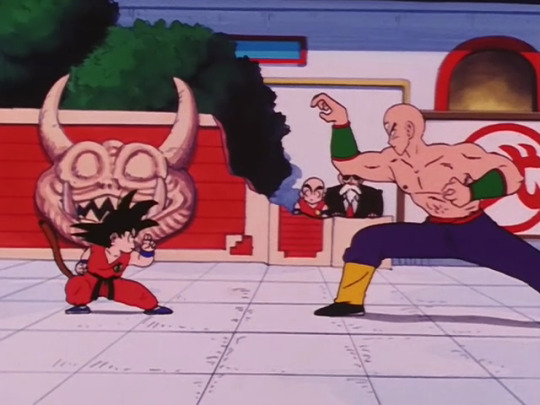

In light of Dragon Ball’s enduring popularity—indeed, the franchise’s cultural relevance only seems to be growing, considering the unprecedentedly wide theatrical release of its latest feature film—it’s easy to forget how much of its overarching narrative was shaped by editorial interference. Whenever the villain of the week raises the stakes by powering up into his “final form,” or the rules of the setting are abruptly altered in order to once again miraculously revive Son Goku from what should have been a permanent death, or the humorous tone suddenly evaporates in favor of yet another explosive battle, it’s usually the result of the publisher “encouraging” author Akira Toriyama to return to the proven—i.e., profitable—formula.

So it feels like Dragon Ball Super: Super Hero is sending a very intentional message when it makes its central antagonist a puny, spineless, unrepentantly corrupt corporate executive that is singularly obsessed with creating a bigger, meaner, stronger version of Cell. Especially when the derivative bio-android turns out to be incapable of speech and devoid of personality; it simply screams incoherently and mindlessly obliterates everything in its path.

This meta-commentary permeates the movie’s entire plot, which deconstructs many of the series’ recurring tropes and clichés. Both the audience and the characters, for example, are accustomed to Goku and Vegeta arriving just in time to vanquish the indestructible foe du jour and save the day. Here, however, the two Saiyan warriors are too preoccupied with their training to answer the call to adventure, forcing Piccolo—everyone’s favorite grumpy green grandpa—to literally beat his fellow Z Fighters out of their complacency. And because the remaining available heroes are all either past their prime or out of practice (or, in one case, an actual toddler), they must learn to rely on tactics beyond brute force—including stealth, deception, infiltration, subterfuge, and good old-fashioned diplomacy—if they hope to prevail against the resurrected Red Ribbon Army.

Dragon Ball Super: Super Hero is far from perfect—the story is bloated with fan service and exposition, the quality of the computer-generated animation is inconsistent at best, and even the title is awkward and cumbersome—but it earns points for departing from convention. In an industry that tends to enforce predictability, it dares to take some real risks. I admire that irreverence; it’s what allows blockbusters to evolve, thus exceeding viewers’ expectations.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rest in peace, Akira Toriyama.

He didn't need the Dragon Balls—his work made him immortal.

Recently Viewed - Dragon Ball Super: Broly

[This review contains SPOILERS. You have been warned.]

Dragon Ball Super: Broly feels like the culmination of everything that the legendary franchise has accomplished so far. It features the triumphant return of several fan favorite characters (albeit slightly recontextualized in order to better fit the notoriously forgetful author’s revised canon), including Bardock, Gogeta, Paragus—and, of course, Broly himself. That last one is particularly noteworthy: whereas he was previously depicted as little more than a mindless plot device, this reboot emphasizes the eponymous Saiyan warrior’s tragic backstory (abandoned on a hostile and inhospitable planet, abused and brainwashed by his own father), transforming him into a sympathetic figure and contributing some much needed personal stakes to the conflict—underneath his tough, cold exterior, our “villain” remains a lost, frightened child; we don’t want to see him sacrificed as a pawn in Frieza’s vendetta.

Which brings me to my next point: Broly beautifully reinforces the series’ central theme (yes, contrary to its reputation for straightforward storytelling and moral simplicity, this children’s battle manga does have thematic concerns). Despite his obsession with increasing his physical power, Son Goku’s greatest strength has always been his ability to forgive, turning former foes into steadfast allies (see: Yamcha, Tenshinhan, Piccolo, and Vegeta). Thus, it is appropriate that the climactic showdown of this film ends not with a flashy eleventh-hour martial arts technique… but with an act of compassion that manages to quell Broly’s blind rage—an unexpectedly elegant and succinct expression of Akira Toriyama’s belief in redemption and second chances.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rest in peace, Akira Toriyama.

He didn't need the Dragon Balls—his work made him immortal.

Random Thought Before Bed: My 3 Favorite Fights from the Dragon Ball Franchise

Recently, I’ve been playing a lot of Dragon Ball FighterZ, and the game’s fast-paced, explosive action has inspired me to reflect on what made me fall in love with Akira Toriyama’s beloved manga (and its equally renowned anime adaptation) in the first place. To that end, I’ve compiled a short (and by no means complete) list of my favorite fights from the series, taking into account not only choreography, but also the narrative context that makes them so emotionally resonant:

3. Son Goku & Piccolo vs. Raditz

Despite its relative brevity, the first battle in the Saiyin Saga remains one of the franchise’s most memorable, if only because it heralded such a dramatic shift in tone. Son Goku had faced superior opponents before, but had always managed to discover some miraculous means of closing the gap in power (training with Korin, drinking the Ultra Divine Water, etc). His villainous brother, however, is on a different level entirely, forcing our hero to enter into a (supposedly) temporary alliance with his deadliest foe: the reincarnation of the Demon King Piccolo. And even that nearly isn’t enough: our protagonists are on the ropes from the beginning of the fight to its bittersweet conclusion, and their eventual victory costs them dearly. Packed with iconic moments that have been endlessly imitated but rarely improved upon—Goku and Piccolo shedding their weighted clothing; Raditz charging, only to suddenly vanish and attack from the rear; Goku’s ultimate sacrifice—this brutal brawl deserves recognition for its historical significance alone.

2. The Z Fighters vs. Vegeta & Nappa

Although it’s often overshadowed by Son Goku’s spectacular one-on-one showdown with Vegeta, I’ve always preferred the slow and suspenseful buildup to his belated arrival; much like Seven Samurai, it’s the perfect underdog story, with a small (and dwindling) group of warriors standing firm against insurmountable odds. All of the supporting players get an opportunity to shine—Krillin’s rage-fueled decimation of the remaining Saibamen, Chiaotzu’s bold kamikaze gambit, Tenshinhan’s dramatic last stand—while the evolving mentor/pupil relationship between Piccolo and Gohan lends the action some much-needed personal stakes; the former would-be world conqueror’s decision to throw himself in front of a fatal blast meant for his archenemy’s son serves as the culmination of the series’ most compelling character arc.

1. Son Goku vs. Tenshinhan

The championship bout of the 22nd Tenkaichi Boudokai is more than a mere fight; it’s a debate on the nature and purpose of martial arts, with each blow elegantly reflecting the participants’ personalities. Ruthless, arrogant Tenshinhan—who, true to his Crane School upbringing, values power and dominance above all else—is always the aggressor, unleashing a series of increasingly devastating techniques in an effort to overwhelm his opponent with sheer force. Son Goku, on the other hand—embodying the Turtle School’s philosophy of patience and discipline—stays on the defensive, continually countering or enduring his foe’s attacks, gradually chipping away at his stamina. Ultimately, the younger fighter’s grit and tenacity convince Tenshinhan to abandon his wicked ways and embrace martial arts as a means of self-improvement, rather than a blunt instrument for crushing his enemies. And that inextricable link between conflict and characterization makes this battle one of the finest Toriyama ever crafted.

[Click here to see more of my countdown lists.]

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Akira Toriyama, creator of Dragon Ball and Dragon Ball Z, dies at 68. Absolutely tragic. Rest in peace Legend.

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

Akira Toriyama's work was, for me and many others, a major formative influence on art style, character design, and all around creativity.

Some of my earliest passion for drawing came from doodling Dragon Ball OCs at school, and trying to replicate the dynamic poses and fights from the manga and anime.

His ability to interchange so well between goofy and serious tones, and introduce endearing and interesting characters, was consistently impressive.

His legacy will endure across many mediums, stories, and childhoods.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently Viewed: Perfect Days

Perfect Days is a film about cherishing small pleasures. It’s about ordinary people living ordinary lives. It’s about the soothing familiarity of a routine and the sudden disruption (either unwelcome or surprisingly refreshing) thereof. But most importantly, it’s about finding unexpected beauty in things that are overlooked and undervalued.

The protagonist, Hirayama, is a janitor, cleaning toilets around Tokyo’s various public parks. In many ways, he is painfully average, albeit a bit old-fashioned: he collects cassette tapes, used books, plants, and photographs of nature. His days are defined by mundane rituals: his alarm clock is the rhythmic scrape of broom bristles sweeping the sidewalk beneath his window; before driving to work, he always quietly enjoys a can of Boss Coffee while the engine of his van warms up; and the handful of restaurants that he frequents consistently have his usual order ready as soon as he enters.

His profession, of course, means that he is often unnoticed at best and disrespected at worst—in one particularly uncomfortable scene, for example, the mother of a lost child fussily scrubs the boy’s hand immediately after Hirayama reunites them. Still, if he resents his lowly status, he refuses to show it, greeting the sunrise with a bright smile that only occasionally falters. Indeed, his relative invisibility has caused him to develop an appreciation for the brief, fleeting moments of peace that society at large has learned to ignore—leaves swaying in a gentle breeze, shadows dancing on a weathered concrete wall, reflected light shimmering on the ceiling of a bathhouse.

The movie’s craftsmanship mirrors the meticulousness with which its central character approaches both his menial labor and his personal hygiene (that mustache is immaculately maintained). Wim Wenders’ direction is intentionally unspectacular and unobtrusive; with very few exceptions, he merely observes the action, allowing the story to unfold at its own pace—at seventy-eight, the esteemed auteur (whose credits include Paris, Texas and Wings of Desire) obviously has nothing left to prove, and can therefore afford to be patient and minimalistic in his style. The editing is equally accomplished; each cut is delicate and sublime, making even seemingly inconsequential frames feel essential and impactful, especially during the surreal dream sequences—hypnotic, abstract montages in which black-and-white images dissolve and cross-fade and otherwise overlap, delighting and dazzling the senses.

But it is Koji Yakusho’s phenomenal performance that truly anchors the narrative. Because the role is predominantly nonverbal, the actor must rely on his eyes alone to convey emotion; the result is absolutely devastating in its subtlety—a compelling portrait of a wounded man desperately struggling against the inherent loneliness of self-imposed solitude, hiding his private suffering behind a friendly grin and an optimistic attitude.

Perfect Days is, in conclusion, a perfect cinematic experience. Hopefully, its recent Oscar nomination will attract a wider audience; this is the type of production that deserves commercial success as well as critical acclaim.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

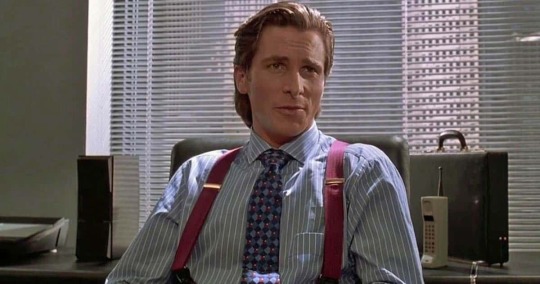

Okay, new plan: I am now going to reblog this post every time David Zaslav commits an unforgivable crime against cinema.

Random Thought Before Bed: My Informal Pitch for a Modernized, Mixed Media Parody of A Christmas Carol

Synopsis: Christian Bale plays Silas Croodge, a greedy, miserly, out-of-touch corporate executive that has recently acquired a popular new streaming service. In an effort to cut costs, he not only cancels several animated projects, but also completely purges any evidence that they ever existed from the internet—thus depriving their creators of royalties and residuals.

Shortly thereafter, he is haunted by a trio of cartoon ghosts. Their mission: to “scare him straight” by forcing him to confront the consequences of his actions. Will this encounter with the supernatural convince Croodge to change his wicked ways?

As it turns out, the answer is a resounding “No.” He dismisses the experience as a bizarre nightmare and immediately continues pinching pennies. Fortunately, he can’t avoid karma forever. His mismanagement of his company soon leads him to ruin: customers unsubscribe, employees go on strike, and advertisers withdraw their support en masse.

As Croodge wanders the streets in a daze—haggard, destitute, and disgraced—he curses the heavens, blaming everybody but himself for his misfortune. A giant pencil then descends from the sky and literally erases him from reality.

And everyone else lives happily ever after.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently Viewed: Winchester ‘73

Winchester ‘73 features an intriguing narrative gimmick. While the overarching plot is a bog-standard revenge thriller—with Jimmy Stewart’s disillusioned sharpshooter relentlessly, obsessively pursuing his father’s killer across the Wild West—the film deemphasizes that particular thread, instead following the journey of the eponymous rifle as it passes from one supporting character to the next (the gun's ill-fated owners include: a shifty traveling merchant, a cowardly rancher, a Sioux war chief—played, naturally, by a Caucasian actor—and multiple bloodthirsty bandits). This broadens the otherwise conventional story considerably, transforming it into a sprawling odyssey that guides the viewer through the various strata of frontier society.

Despite having aged poorly in certain regards—particularly in its depiction of Native Americans as villainous (albeit not entirely unsympathetic) savages, its implicit glorification of Confederate values (both our protagonist and his plucky sidekick fought for the South), and its use of the egregiously problematic “save the last bullets for the womenfolk” trope—the movie's novel structure makes it an essential genre classic. Of equal interest is Stewart’s charismatic performance, which represents a transition from the wholesome, “golly gee” Boy Scout roles with which he had previously been associated to the morally ambiguous, psychologically complex antiheroes that would later define his career. If you can accept Winchester '73 as a relic of a less enlightened era (and honestly, it's positively progressive by 1950s standards, even taking its "cowboys versus Indians" conflict into consideration), it’s a handsomely crafted picture, elevated by lush black-and-white cinematography and suspenseful action scenes.

#Winchester '73#Antony Mann#James Stewart#Jimmy Stewart#Criterion Channel#Western#film#writing#movie review

2 notes

·

View notes