Photo

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nitzavim: You Have A Choice

youtube

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#shabbos#shabbat#sabbath#torah study#nitzavim#deuteronomy#oneshul#shabbat shalom

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

OneShul will cease active operations at the end of 5779.

Reasons here: http://oneshul.org/

All of us thank you for the pleasure of your company these past nine years. We wish you a joyous and richly blessed 5780.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ki Tavo: Blessings, Curses, and a Holy Marriage

youtube

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#shabbos#shabbat#sabbath#torah study#ki tavo#deuteronomy#oneshul#shabbat shalom

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ki Teitzei: When You Go

youtube

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#shabbos#shabbat#sabbath#torah study#ki teitzei#deuteronomy#oneshul#shabbat shalom

1 note

·

View note

Text

Shoftim: Justice, Justice Shall You Pursue

youtube

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#shabbos#shabbat#sabbath#torah study#shoftim#deuteronomy#oneshul#shabbat shalom

0 notes

Text

Reeh: A Blessing and A Curse

“See, I give before you this day a blessing and a curse. The blessing, that you will listen to the Commandments of the Lord your God, which I command you this day. And the curse, if you will not listen to the Commandments of the Lord your God, and you turn from the Way which I command you this day, to follow other gods, which you have not known” (Deut. 11:26-28, translation mine).

The Sefat Emet (Pen name, “The Tongue of Truth,” of the Chasidic Rabbi Yehudah Leib Alter of Ger, 1847-1905), in commenting on these verses, states that “[In] the blessing it says, ‘that you listen,’ but in the curse it says ‘if.’ Goodness exists within the Jewish people by their very nature; sin is only incidental. …Even if there is some sin—and indeed ‘there is no one so righteous as to do good and never sin’ (Eccles. 7:20)—it is only passing” (Green, 1998, pp. 302-3).

Rabbi Arthur Green, from whose masterful The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of the Sefat Emet, Rabbi Yehudah Leib Alter of Ger (Phila., PA: JPS, 1998), the above is taken, universalizes the above reference by stating that, although only we Israelites can claim the Covenant dating from Mt. Sinai, all of Humanity “must contain that essential goodness.” In other words, all mortal beings who profess to follow a moral code have a share in the above statement. The veneer of civilization is very thin, and it is easy for immoral leaders and followers to destroy it. Humanity must work all the harder to preserve our world.

As a species, we are more divided than ever before. Yet we all share the same drives for survival, happiness, success in life, and safety for ourselves and our loved ones. Rather than reinforcing what divides us, we must seek what we hold in common as human beings: feelings, dreams, and aspirations.

At the time that Moses gave the above speech, he was mortally concerned that the Lord’s people were entering a society in which they would be a minority. As free men and women, nomadic in heritage, able to make their own decisions about where to live and whom to marry, they might swiftly assimilate among the more settled, agricultural peoples of Canaan, and, within a few generations, vanish as a unique people. Ironically, this remains a major concern for us Jews, thousands of years later—still separate, still asking the same questions.

As Jews, we are proud of our tribal, religious, cultural, and nationalistic differences, but, as human beings, we must always aim towards a common goal. As we aspire to political freedom, so must we work to understand similar political yearnings in others, provided that the debate is peaceful. The Golden Rule which we gave the World must guide the steps of all right-thinking humanity: if we cannot love all of our neighbors, let us, at least, respect them, and insure that we receive that same respect—neither as victors or victims, but as equals.

There is an old story about a woman—call her Ms. Richter—who invites her rabbi to visit her home, serving him a cup of tea on her best china, while they sit in the sun room which faces the back yard. Making small talk, the rabbi notices the fence separating the woman’s yard from her neighbor’s, Ms. Jones; he remarks about the freshly-washed sheets and clothing Ms. Jones has hung in the yard, and asks if they are friendly with one another.

“That woman?” scoffs Ms. Richter, “I wouldn’t give you the time of day with her. Why, look at the laundry she hangs out there, on her line. It’s filthy!”

The rabbi gets up, walks to the window, runs his finger along it, and replies, gently,

“Ms. Richter, there is nothing wrong with your neighbor’s laundry. I’m sorry to tell you that the problem is your windows: they’re dirty.”

When we look at the faults of other people, other nations, are we so quick to judge their shortcomings, or should we take the trouble to look beneath the headlines, beyond the shrill cries of their politicians, and see that, beneath the “dirt” which separates us, they are, perhaps, just people—not far different from ourselves, hoping for a Better Tomorrow for themselves and their children? Or are we satisfied with simply looking at them through a dirty window of stereotyping? It’s not easy: we are, after all, all human beings, not Angels—but God gave the Torah to us. What are we to do with it?

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbos#shabbat#sabbath#torah study#re'eh#reeh#deuteronomy#oneshul#shabbat shalom

1 note

·

View note

Text

Eikev: Joshua Rebukes Moses

I am Joshua ben Nun; orphaned in Egypt—my parents perished while building the pyramids that dotted the Valley of the Kings. It was Jochebed, mother of Moses, who took me in, may she rest in peace. I recall being a small child, when Moses was already a teenager—Jochebed often took me to the Pharaoh’s Palace to visit him. I thought of him as a mix of an older brother and a kindly uncle. I wept when she told me Moses that had fled from Egypt, fearful of the punishment that would follow his having killed a slave driver.

Moses has been my mentor and guide for all these years in the Wilderness; I was fortunate to be with him when he climbed Mt. Sinai, there to commune with the Almighty and receive the Ten Commandments. I did not join him on the mountaintop; I hid amid the boulders along the path. There, I witnessed the battle between Moses and the Angels who did not wish to relinquish the Torah, until God intervened.

The Generation of the Exodus is gone; now, he and I lead the Generation of the Wilderness. I was happy to hear that My Lord Moses wished to teach Torah to these youngsters. He and I had had such high hopes for them! After all, they were not tainted by the slavery experience; they had been nurtured in freedom, under God’s protection, who fed them with manna, and so much more. Unfortunately, it is not unusual for headstrong young people to spurn their elders’ instruction, and these Israelites had not hesitated to participate in the riotous orgy brought on the Midianites and their god, Baal Peor. Sadly, many of them paid for their sins with their lives.

Nonetheless, could there not be a time for reconciliation? I looked forward eagerly to Moses’s Torah lecture; surely he would find a way to make peace between the people and their somewhat testy deity. Was He not a God full of mercy and compassion, extending forgiveness to the thousandth generation? Instead, Moses lectured them about their backsliding:

“If you do forget the LORD your GOD and follow other gods to serve them... I warn you this day that you shall certainly perish... because you did not heed the Lord your God.”

--Deut. 8:19-20

And that was not all: Moses recounted all of their sins for them, and laid it on very thick. It disturbed and frightened me.

When Moses was done with his teaching, bitter as it was, I gave him my strong right arm on which to lean, as I escorted him to his tent.

“What think you of my address to the people, hey Joshua?” Moses asked me.

“May I speak frankly, My Lord?” I answered. When he nodded, I responded to him quickly and precisely: “It seems to me, Rabbi Moses, that you might have sweetened your words a little. When I behold this people, the work of God’s hands, I consider that they are unlettered, unsophisticated—have they not been living in the wilderness for all of their lives? Since their parents perished in this great and savage desert, they have no one except you, Sir, to teach them the proper way for Jews to live.”

Moses stopped walking, and looked directly at me: I swear, it was as though he could see straight into my heart and soul.

“You are right, my disciple, to question me; never fear—I am not angry. Yes, you are right; I did speak harshly with the people. But life is very hard, and one must be steeled to difficulties in order to overcome them. Hear me, Young Joshua: in days to come, there will be many Jews who behave un-Jewishly, who cheat and lie and forget their heritage. My duty is to warn them of the consequences. And those who heed me will understand how to act.”

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbos#shabbat#sabbath#torah study#ekev#eikev#deuteronomy#oneshul#shabbat shalom

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vaetchanan: God and Moses

Scene: a windswept mountaintop, named Pisgah. Tumbleweeds fly about in the strong wind; autumn is coming. A thin, tired-looking man with a long grey-white beard, our Moses, is struggling to attain the heights. He finally succeeds, panting; he takes a deep breath, sips from his leathern water-flask, and stands, waiting. And waiting.

Moses: Lord God? It is I, your humblest servant, Moses. Will it please You to speak to me.

The lightning cracks and the thunder rolls, but there is no answer.

Moses (sighs): Lord God, it is not like I don’t have things to do. I am the only one commanded to ascend and speak with You. I have no time; I must go down to judge the people’s litigations. They are stubborn and stiff-necked; I had thought that this Generation of the Wilderness would be more—pliable, but I was wrong. They are as sinful and full of pride as their departed ancestors, who perished at—at Baal Peor, or the Golden Calf, or Korach’s Rebellion—I would rather speak to you of their successes, but cannot recall any.

The Voice of God: I am here, Moses. Where are your judges of tens, judges of twenties, and so on? Did you not remind the Israelites of your appointing them, just a short time ago?

Moses: My judges—pah! A bunch of self-centered good-for-nothings—You killed them (as they rightly deserved) for taking part in the People’s various orgies. And only am I escaped to tell You, and afterwards judge the saving remnant of my people.

God: Shall I send lightning-bolts to fry these rebels, Moses? Let me prepare them—

Moses: No, Lord God, no. I can handle them, and Joshua, my successor, will be able to deal with them, too. I only beg You to deal with them in compassion. Yes, they have faults enough, but who else will be Your treasured nation, and the apple of Your eye, if not them? You chose them long ago; yes, when you ordered Abram and Sarai, “Get thee out of Haran, you and your household, and go to a land of which I will tell you.” That covenant must stand.

God: Thank you for reminding Me. I had not forgotten, but I have a great deal to remember, what with plagues in Egypt, volcanic eruptions in Santorini, and answering the prayers of the natives in North America....

Moses: Where is that?

God (hastily): Never mind. There. So. What is your next step?

Moses: I know, Dear Lord, that You have ordered me not to enter the Land; I will die on this side Jordan. I am reconciled, but it is hard, so hard, Lord....

God: Take heart, My Servant. I will let you down easy. Your passing will be like a hair removed from a cup of milk. But you have a great deal more to do, before you go to be with Me, forever.

Moses: And what is that?

God: Tell My people that the penalty for backsliding and idolatry will be exile. If they sin, I will scatter them among the nations. Tell them that, when they look into their hearts and examine their souls, they will know that I will not abandon them forever. It may be hard for mortals to comprehend, but I am compassionate at the core: I will not forsake them, but will be with them in the countries where they come. Tell them that, Rabbi Moses. Teach them....

Clouds settle over the mountaintop, obscuring Moses from view

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbos#shabbat#sabbath#torah study#va'etchanan#vaetchanan#deuteronomy#oneshul#shabbat shalom

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tu B’Av starts at sunset. More information below.

https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/tu-bav/

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tisha B’Av starts at sunset. More information below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAoSODDghE8

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

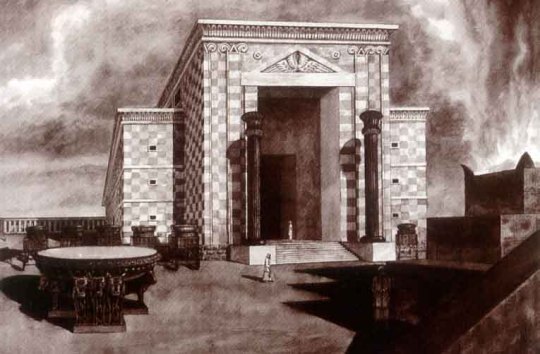

Devarim: Meet the Deuteronomist

We enter the dog days of summer: the sun burns fiercely; our forays outdoors are humid and steaming. And we prepare for Tisha B’Av, the Ninth Day of the Month of Av, the most tragic day in the Jewish calendar. This Shabbat, we begin our reading and study of the fifth book of the Pentateuch/Chumash: Sefer Devarim, the Book of Deuteronomy.

As a child, my Orthodox rabbis taught me that the Torah—that is, the Five Books—were written in a complete unit by Moshe Rabbeinu, Moses our Rabbi. At this point in the overall narrative, he seems to have gained a renewed strength, both in body and purpose: to educate the Dor HaMidbar, the Wilderness Generation—those Israelites with no personal memory of Egyptian slavery or the Sinai Theophany. He does so by recounting the entire Wilderness History of our nation, beginning with this, our parsha.

Moses’s central theme is the urgency of obedience to God, lest Israel risk His wrath and punishment. The only assurance is to remain eternally faithful. Moses recounts his appointment of judges of thousands, of hundreds, fifties, and tens—oddly enough, he seems to have forgotten how Jethro, his Midianite father-in-law, assisted him in establishing the roots of Jewish jurisprudence. But then, Jethro’s tribal status would perhaps not make him worth remembering, in light of the Israelites’ struggles with Midian in the previous parsha.

All of this discourse and exhortation occurs in a way station of “that great and terrible wilderness” (Deut. 1:19). It must have been awe-inspiring: the assembled multitudes of Israel, all young, idealistic, eager to cross the Jordan and attack their Canaanite foes. Indeed, this same indoctrinating style persists throughout the entire Book of Deuteronomy, but it does not stop there: it continues into Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings, as well as parts of the Book of Jeremiah. It is, indeed, a deep and long-winded discourse by Moses, in a windswept, sun-baked plain of the Sinai Peninsula, the Aravah. Highly dramatic, too—except that it never happened.

Modern Biblical scholars hold, for the most part, that an anonymous scholar (or school of scholars) whom they label the Deuteronomist, wrote the above works. He emerged following the destruction of Israel, the Northern Kingdom, by Assyria in 721 BCE. Jewish refugees of the catastrophe, as tragic and infamous in its day as the Holocaust to us, came to the Southern Kingdom of Judah for refuge. They brought with them a strong need for our people to survive, along with a bedrock belief in the concept of Adonai as the only God to be served. This was news to the sinful people of Judah, engrossed in idolatry.

The movers and shakers in Judean society were the aristocrats who owned land, and who furnished the governmental administrators in the capital of Jerusalem. Skimming over that era’s history of regicide (King Amon, 640 BCE) and the aristocrats’ placing his then eight-year-old son Josiah on the throne, as well as Assyria’s downfall and its replacement by harsh and ruthless Babylonia, we encounter the signal tragedy which we mourn, the Destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE.

All of these court intrigues and external pressures weighed on the consciences of our ancestors: if God loved Israel so, why was He allowing their destruction and suffering? Here is where the Deuteronomist emerged, with a simple but weighty reason and solution: God had decided to punish His people for their many sins of ignoring Him, oppressing the poor and the Stranger, and neglecting the Temple for idol worship.

Given that the overwhelming weight of Jewish History is tragic, it was heartening when Babylonia fell and the Persian Empire under Cyrus allowed the Israelites, along with other captive peoples, to return to their homelands (539 BCE). From there to us post-modern Jews of today, with our streaming services and virtual Judaism, seems a breath of fresh air.

Following the fateful Ninth of Av, we enter the High Holy Day season, time for the strongest and largest temple attendance of the year. We look around at one another and note that we have survived an old year with its calamities, to welcome a new year with its blessings.

Never forget to thank the Deuteronomist, who worked so hard to ensure our faith and our survival. And, see you in temple this Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur!

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbat#shabbos#sabbath#torah study#devarim#deuteronomy#oneshul#shabbat shalom

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

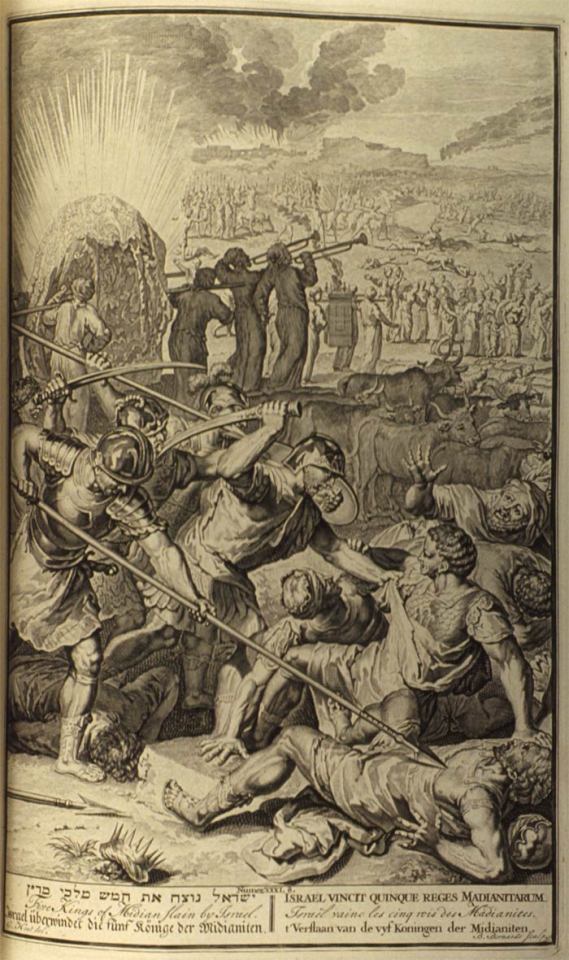

Mattot-Masay: The Midianite Tragedy, and Us

The LORD spoke to Moses, saying, “Avenge the Israelite people on the Midianites.” Moses spoke to the people, saying, “Let men fall upon Midian to wreak the Lord’s vengeance.” [The Israelite warriors] fell upon Midian, and slew every male, including male children, and [afterwards] slew every married woman. And they took much booty, for the priests and the Lord.

--Num. 31:1-18 (adapted)

There are many scapegoats for our sins, but the most popular one is Providence.

--Mark Twain, 1898

Why is this portion of Torah so war-mongering, and so bloody? Rabbi Michael Lerner, Ph.D, writes of “A Torah of Love and a Torah of Hate,” and this is clearly an example of the latter.

Who wrote the Torah? Why, Moses, clearly and without a doubt. This was, and is, the Traditional viewpoint, embraced today by only the Orthodox. Perhaps, however, the Documentary Hypothesis has crept in among them, as well: I recall participating in the very first class on Scientific Bible Criticism to ever be taught at Yeshiva University, my long-ago alma mater. According to this school of thought, it was a Kohen, a Priest, who wrote the Book of Numbers, which we are shortly concluding. Scholars call him P, for obvious reasons.

There were other authors, listed in many a book of Biblical scholarship: J, E, D, and others. Each had a particular style and language. There was also P.

The question, according to James Kugel, Ph.D, in his How to Read the Bible (2007, pp. 299-306), is, when did P live? Dr. Kugel, of Harvard University and currently Emeritus at Bar-Ilan University (and who identifies as Orthodox), explains that the older scholarly opinion was that P was post-exilic. P was well aware of the Destruction of the First Temple, and the Israelites’ being kidnapped to Babylonia.

Following Babylon’s defeat by the Persians, the victors allowed the Israelites to return to Israel. Significantly, most of them did not. Think of the paltry number of American Jews who moved to Israel following its independence; American fleshpots were more tempting than a Spartanlike kibbutz. More recently, it is believed by several of them that P actually lived in the pre-exilic period, when the tiny kingdom of Judah was threatened, both within and without.

Against these sad and tragic backgrounds, P, possibly a Priest without a temple, wrote the Book of Numbers. Which returns to my central question: why is Mattot-Massay so bloody? Why the massacres of Midianite prisoners, and the acts of looting, all on the tired excuse that Midian and Peor enticed the people to idolatry? I cannot excuse the violence, but I believe that P was trying to harken back to a period when his nation was powerful, rather than refugees at the hands of Babylon and Persia. It is inexcusable, by our modern standards, that the bloody tales of these Torah portions were inflated and aggrandized. Well, yes: but please note that various nations, the US chief among them, possess sufficient nuclear missiles to annihilate humanity more than five times over. Note also that our nation is top among arms merchants to the world; in various Third World countries, a submachine gun is cheaper than a loaf of bread.

In the end, what remains? I hold with Rabbi Lerner’s comment: our Book contains both love and hatred. It is left to us to comprehend the difference, and, in spite of our tragic past, endeavor to work for a peaceful humankind.

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbat#shabbos#sabbath#torah study#matot-masei#mattot-massay#oneshul#shabbat shalom

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love movies? Here's a list of 253 Jewish movies compiled by rabbis.

Go 'way beyond Fiddler On The Roof... Learn a little, enjoy a lot! - https://rabbiatthemovies.com/

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pinchas: A Daughter of Tselophechad Stands Up for Her Rights

The daughters of Tselophechad, of the Tribe of Menashe...came forward to Moses for judgment, regarding property they had inherited from their father. Their names were Machla, Noa, Chogla, Milka, and Tirza. ...They said, “Our father died in the wilderness. ...He has left no sons. Let us inherit his property!” And Moses brought their case before the LORD.

--Numbers 27:1-5

I am Milka, next-to-the-youngest of our father Tselophechad. In the Torah Rabbi Moses wrote—or dictated by God’s command—that we, though being mere women, should inherit our father Tselophechad’s property. It was then, and still is, a milestone in Jewish legislation that a woman should inherit property. However, in the end, all my sisters except me married our cousins, also Menashites. This kept the property in our little tribe, that of Menashe, son of Joseph, who rescued Pharaoh and the Kingdom of Egypt from famine. It is hard to remember Joseph fondly, because, by bringing our ancestors down to Egypt, he also condemned them to the fate of slavery: a four-hundred-year sentence.

But that is all behind us, now; the Holy Land awaits our conquest, and I am eager to participate. Nonetheless, I refuse to submit to the judgment of Moses and his God; I wish to hold on to my paltry share of Papa’s property, alone.

Before he died, Papa took each of us alone into his bed-chamber. When it was my turn, he told me: “You, Milka, despite being neither firstborn nor last-born, have always been my favorite,” he said, his voice made weak by the illness that killed him—and where was God then, to rescue a man about whom no one could any ill?

“I wish for you to retain this small bit of property that I leave you.” And he presented me with a silver ring, with a red stone in it. Is it a ruby or garnet? It does not matter: it was a gift from my Papa, who chose me to be his favorite. I am content.

So, when we went before the great Moses—how thin he was, and how frail! It is hard to believe that the Word of Almighty God could reside in such a skinny body—bossy Machla, my eldest sister, spoke for all of us, as she always does. I kept my peace. I knew I was the favorite; Papa had told me so.

The days and moons have passed; my sisters have married our cousins, and I wish them well in their choices. I cannot say that any of my new brothers-in-law impress me; they prefer not to work, instead spending their days guzzling beer in the tavern, and bothering Uncle Emir for pocket money.

For myself, I have chosen to live my life with my lovely girl companion, Ahava bat Emet, who has been my friend for all of our lives together, since we met years ago in the little children’s Torah class. I love when she looks at me—her eyes are golden-brown, like the soil of Canaan which we will enter shortly, like the sun when it sets over the wildnerness. We take long walks, and talk for hours. I much prefer her company and her love over that of any man—and no one need know. Why, what business is it of theirs?

When Moses dies and Joshua takes over, our citizen-troops will win us a holding in the New Land, Ahava and I will build a small house, on the outskirts of Menashe’s tribal portion. We will spin and dye wool together to sell in the marketplace. When the day grows cool, I will take my beloved’s hand, and we will walk through the country which God has gifted to us.

When we grow old and our time comes to depart this life, we will be buried, side by side. Our love will never die.

Bloom forever, O Israel, from the dust of my bosom!

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbat#shabbos#sabbath#torah study#pinchas#oneshul#shabbat shalom

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hear a 3-min explanation of the word "Kabbalah" at the link below.

No hocus pocus or confusing terms, just a basic explanation of the word used to describe the possibilies for our receiving from The Infinite. http://jewishnews.com/2014/11/27/jewish-rabbi-explains-what-the-word-kabbalah-means/

0 notes