#Loyola University New Orleans

Text

"I'm someone." 🐊🌡

I am Floridian and grew up in New Orleans longer than just when I was a teenager. It was a long time.

People in Cleveland are so bossy, but I like them and think the nice ones are smart. They are mistaken I need correction more than anyone else. They act like I'm the shyest one, "on the spot." They know me and see me as in trouble, like New Orleans. I suspect my dad did that then, as later in college when I was pulled out for no reason but told I was shy. They called me to the office with my parents/dad and counselor more than once in my 3rd of 4 years of high school, just because they were "ticked off" at me, for no reason, me being labeled "withdrawn."

So, other Floridians people are interested in, though I'm more of a Northerner at heart I'm sorta not really talked to or "educated."

0 notes

Text

Loyola University New Orleans.

October 2022.

0 notes

Audio

How are your plans for this year going? Good? Not so good? Luckily, it’s not too late to reset, break any unhealthy patterns, and get on track so you can live a life in passion and purpose. And guess what? This week’s guest, Justin Shiels, is just the person to help you make that happen.

We talked about his theme for this year — intentional growth — and Justin spoke about the big life change that inspired him to not only take a break, but to write a book to help others experience a breakthrough. Justin also shared what it was like coming of age in New Orleans, how his stint as a creative director in the advertising agency shaped his current work, and talked about how he finds joy and maintains his creativity. Justin is a real ray of sunshine, and his energy for changing hearts and minds is what we need more of in this world!

For extended show notes, including a full transcript of this interview, visit revisionpath.com.

DONATE TO REVISION PATH

For 10 years, Revision Path has been dedicated to showcasing Black designers and creatives from all over the world. In order to keep bringing you the content that you love, we need your support now more than ever.

Click or tap here to make either a one-time or monthly donation to help keep Revision Path running strong.

Thank you for your support!

Revision Path is brought to you by Lunch, a multidisciplinary creative studio in Atlanta, GA.

Executive Producer and Host: Maurice Cherry

Editor and Audio Engineer: RJ Basilio

Intro Voiceover: Music Man Dre

Intro and Outro Music: Yellow Speaker

☎️ Call 626-603-0310 and leave us a message with your comments on this episode!

FOLLOW US: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify

#Revision Path#Justin Shiels#entrepreneur#creative consultant#creative coach#The Reset Workbook#Austin#Texas#Loyola University#University of New Orleans

0 notes

Text

“I don’t know of another time in history where so many courts in so many different levels all over the globe [have been] tasked with dealing with a similar overarching issue,” said Karen Sokol, law professor at Loyola University New Orleans College of Law.

Research also continues to unearth more about the fossil fuel industry’s knowledge of climate change. A January study revealed that Exxon had made “breathtakingly” accurate climate predictions in the 1970s.

The vast majority of climate-focused cases in the US have previously focused on the regulation of specific infrastructure projects, such as individual pipelines or highways, said Michael Gerrard, founder and faculty director of Columbia Law School’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.

But the new forms of climate litigation are different, as they grapple not with particular projects’ emissions, but on responsibility for the climate crisis itself. Sokol, who dubbed these new suits “climate accountability litigation”, says though they will not alone lower emissions, they could help reshape climate plans.

750 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heyy

So, this is mostly just a fun timeline I made with little research backing it, but I thought it might be cool to share?

It goes through what historical events happened throughout Alastor’s life that might have impacted him and sets the stage for what his life might have looked like. It does hinge quite a bit on US history, so I will also touch on parts of that for our friends who aren’t from the US and don’t know : D

Now keep in mind that this is more of just a list of fun facts that i’ve shoved into a readable outline, than anything put together lol.

Alastor is said to be in his 30’s or 40’s when he died in 1933, this puts his year of birth at a rough range of 1890-1900. For the purpose of this timeline, I will be assuming that Alastor was born in the year 1902 because I want to. This would make him 31 at the time of his death.

In 1892, the supreme court ruled on Plessy vs Ferguson, which was what established the idea of ‘Separate but Equal’ <- (i'm assuming people know what that is and stuff, if you don’t know, feel free to ask, I can give more of a history lesson)

From 1900-1909, education past the 5th grade did not EXIST in New Orleans for black children. This is a large part of why I believe a birth year of at least 1900 would be more accurate for Alastor, as he would have been 7-9 (2nd-4th) when middle school (6th-8th) became available to him.

In 1917, McDonogh No. 35 High School became the first public high school for black teens. Alastor would have been 15 in my timeline. This means that he would have likely been out of school for a year under the assumption that he wouldn’t be able to go anymore. (There were a couple private schools, but those were Expensive!!)

1920: KKK reemerged in Louisiana <- (again, assuming people know the history on this, if you would like a quick history lesson, lmk!!)

In 1921, Alastor graduated! Yay!! He is now 19!

Now, a fun fact! Throughout all of this, radio has not existed as a Thing in New Orleans. Alastor would not have grown up listening to the radio. It would have been new tech for him!!

In 1922, the first radio station came to New Orleans!!! It’s called WWL and it runs … drumroll please … ADS!!! In an attempt to raise funds for Loyola University! Exciting, right? : D

By 1927, the Federal Radio Commission was established in an effort to help organize airwaves, which had become messy and disorganized from the abundance of unlicensed, random people broadcasting.

1933: Alastor dies D:

Also 1933, oddly enough, A newspaper somehow managed to get radio stations in New Orleans legally banned from airing news from the last 24 hours?????

An interesting note. This ban went through in the summer. Deer season is in the winter (Dec-Jan), so it was either banned 6 months before or 6 months after Alastor’s death

1934: FRC is replaced by the Federal Communications Commission

This is pretty much all I have. I also am including some of the links to sources that I thought were interesting. Super open to discussions and questions lol. Hope someone enjoyed reading all this lmao

And also @nunalastor cause you seemed interested and I finally got everything together lol

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

ANGOLA, La. (AP) — A hidden path to America’s dinner tables begins here, at an unlikely source – a former Southern slave plantation that is now the country’s largest maximum-security prison.

Unmarked trucks packed with prison-raised cattle roll out of the Louisiana State Penitentiary, where men are sentenced to hard labor and forced to work, for pennies an hour or sometimes nothing at all. After rumbling down a country road to an auction house, the cows are bought by a local rancher and then followed by The Associated Press another 600 miles to a Texas slaughterhouse that feeds into the supply chains of giants like McDonald’s, Walmart and Cargill.

...

They are among America’s most vulnerable laborers. If they refuse to work, some can jeopardize their chances of parole or face punishment like being sent to solitary confinement. They also are often excluded from protections guaranteed to almost all other full-time workers, even when they are seriously injured or killed on the job.

...

Many of the companies buying directly from prisons are violating their own policies against the use of such labor. But it’s completely legal, dating back largely to the need for labor to help rebuild the South’s shattered economy after the Civil War. Enshrined in the Constitution by the 13th Amendment, slavery and involuntary servitude are banned – except as punishment for a crime.

That clause is currently being challenged on the federal level, and efforts to remove similar language from state constitutions are expected to reach the ballot in about a dozen states this year.

...

While most critics don’t believe all jobs should be eliminated, they say incarcerated people should be paid fairly, treated humanely and that all work should be voluntary. Some note that even when people get specialized training, like firefighting, their criminal records can make it almost impossible to get hired on the outside.

“They are largely uncompensated, they are being forced to work, and it’s unsafe. They also aren’t learning skills that will help them when they are released,” said law professor Andrea Armstrong, an expert on prison labor at Loyola University New Orleans. “It raises the question of why we are still forcing people to work in the fields.”

The article goes on, but this is sickening enough. It's slavery. I hate this. I hate that my food is grown using slavery. I want to boycott every company that uses slavery.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

An important article of Pr. Robert Karl Gnuse about the possible influence of the ancient Greek Classics on the Hebrew Bible (with Herodotus playing a major role in it)

“ Greek Literature and the Primary History

In recent years, however, a number of scholars have dated the biblical books in the Primary History (Genesis through 2 Kings) very late. Thus, they have raised the possibility that the authors of these books might have been very familiar with Classical Greek texts down to 300 BCE and Hellenistic Greek texts after 300 BCE, and perhaps they even used some Greek texts to craft plot-line and imagery in the books of the Primary History.

See Also: Hellenism and the Primary History. September, 2020 Forthcoming by Routledge.

By Robert Karl Gnuse

Chair of the Department of Religious Studies

Loyola University New Orleans

June 2020

Comentators have observed for years how biblical authors might have used Greek texts or reflected Greek thought in their writings. Generally, these observations were connected with biblical works authored after 300 BCE. One thinks especially of the Wisdom of Solomon, dated around 50 BCE, which was loosely connected to the Middle Platonic philosophical tradition and often compared to the writings of the Jewish author Philo, who wrote in Greek. The two books of Maccabees were occasionally compared with historiography generated by the Greeks. Various Jewish novels were sometimes discussed in connection with Greek novels. Koheleth was associated with Greek stoicism and epicureanism.

In recent years, however, a number of scholars have dated the biblical books in the Primary History (Genesis through 2 Kings) very late. Thus, they have raised the possibility that the authors of these books might have been very familiar with Classical Greek texts down to 300 BCE and Hellenistic Greek texts after 300 BCE, and perhaps they even used some Greek texts to craft plot-line and imagery in the books of the Primary History. They are often called “minimalists” for dating the biblical texts so late, and they usually believe that most of the biblical narrative does not reflect the actual history that happened in the pre-exilic period down to 586 BCE. These “minimalists” have been called the “Copenhagen School” because leading authors come from the University of Copenhagen, although sometimes faculty from England (including Sheffield University) are included with them. “Minimalists” also fall into two groups. Some suggest that Genesis through 2 Kings arose primarily in the Persian period (540-330 BCE), while others stress the Hellenistic era, after 300 BCE, as the time of origin for most or all of the Primary History.

The possibility for such an interface between Greek and biblical texts late in the post-exilic period was raised by several authors. Significant works have been written by authors who raise the larger questions of a later date for biblical literature: the likelihood that the texts are fictional narratives driven by theological perspectives and the influence of Greek literature upon the texts.

Very early in the discussion, Giovanni Garbini suggested that the Primary History arose in the second century BCE slightly before the translation of the Greek Septuagint. The biblical text was fiction; the historiography was inspired by contemporary literature in the Hellenistic world (1988; 2003).

Nies Peter Lemche, the most well known advocate for the Hellenistic origins of the Primary History, maintained that only in the Hellenistic era could Jews produce such a significant historiographical work with an eye to the writings of Herodotus and other Greek historians. The literature was mostly fictional and highly ideological. The origin of this literature could have been in Seleucia of Syria during the second century BCE (1993; 1994: 174-87; 2000; 2001; 2008; 2011; 2015). His seminal article for the later discussion of Greek influence was “The Old Testament—A Hellenistic Book?” (1993).

Of equal significance in the debate was Thomas L. Thompson, who also located the Primary History in the second century BCE. He viewed some biblical narrative as reflections of Greek myths and history. Of his many examples, he suggested that Abraham’s travels are inspired by the wandering of the Greek hero Aeneas; David, Hezekiah, and Josiah are allegories of the Maccabean king John Hyrcanus; and Solomon symbolizes Alexander the Great (1999: 66, 77-78, 207-08, 273). He has written massively on the ideology of history writing and placed it in the context of Greek historiography. Lemche, Thompson, and Philip Davies of Sheffield University were the leading representatives of the Copenhagen School of minimalists.

Some scholars wrote comprehensive volumes covering a wide range of literature seeking to demonstate the dependence of bbilical literature in the Primary History upon Greek literature.

Russel Gmirkin believed that the Hebrew Bible and the Greek Septuagint were produced by Jewish intelligentsia in the library of Alexandria in the third century BCE at the request of Ptolemy II. Genesis 1-11 was inspired by the Babyloniaca of Berosus in 278 BCE, not Mesopotamian stories like the Enuma Elish, as we often taught in the past. The account of the exodus and Moses was designed to counter the Greek writings of Manetho (History of Egypt) in the early third century BCE about the Jews (2006: 91-239; 2014). The laws in the Pentateuch were inspired by Plato’s Laws (2017: 77-139, 183- 234).

Lukasz Niesiolowski-Spano described parallels between narratives in the Primary History and stories throughout Greek Classical and Hellenistic Literature. He suggested a Maccabean monarch authorized the creation of this literature in the second century BCE. His work focused closely upon the accounts of the shrines in the Old Testament (2011). He also believed that Genesis 1-11 reflected influence from the writings of Plato (2007).

Philippe Wajdenbaum produced a massive volume tracing the connections between hundreds of biblical narratives and a host of Greek Classical and Hellenistic texts (2011). That all these Greek authors knew the Bible, written by obscure Jews, is not possible, but that Jews would be familiar with the writings of the Greeks, whose culture overshadowed the world at this time, is much more likely. He also sought to demonstrate a connection between biblical laws and Plato’s Laws (2010). If only one-tenth of Wajdenbaum’s observations are correct, he has marshalled a tremendous amount of evidence for Greek influence in the Primary History.

Some scholars have focused upon the Deuteronomistic History, a significant part of the Primary History, and they maintain that this corpus of literature shows dependence upon the writings of Herodotus (Histories) in the fifth century BCE. This would locate the biblical material at least in the late Persian period, if not the Hellenistic era after 300 BCE.

Flemming Nielsen believed that Herodotus imparted to the Deuteronomistic historian an emphasis upon the tragic dimension in history. By tragic, Nielsen meant that both authors emphasized the distance between people and the divine, the need for humans to keep their place in the order of life, and how pride and overstepping one’s boundaries brings punishment or destruction. Though his arguments might suggest a late Persian period origin, he suggested that the biblical materials were generated in the Hellenistic era after 300 BCE, for in his opinion, this was the only logical era when a biblical author had access to the writings of Herodotus.

Jan-Wim Wesselius wrote a monograph demonstrating how the books of Genesis and Exodus reflect the writings of Herodotus, especially the latter’s narration of the lives of Persian kings. He compared in great detail the similarities between Joseph and Cyrus, and especially between Moses and Xerxes. Joseph and Cyrus both have dreams, are exposed to die, go into foreign exile, are hidden for a time, and become ascendant when their identity is revealed. Moses and Xerxes go forth to conquer either Canaan or Greece and cross water with their people. Many other details are mentioned, as well as comparisons between Terah and Phraortes (a Median king), Abraham and Cyaxares (a Median king), Isaac and Astyges (a Median king), and Jacob and Mandane (mother of Cyrus) (Wesselius 1999: 24-77; 2002: 6-47). Though Wesselius theorized these books were crafted in Nehemiah’s Jerusalem in the late fifth century BCE and placed the origin of the Primary History between 425 BCE and 300 BCE, later minimalist authors have referred to his detailed research as evidence that these books more likely were written in the Hellenistic era after 300 BCE.

A number of authors have written articles that focus upon a more limited range of biblical texts. Often these segments of literature come from the Deuteronomistic History with its clear composition from the diverse corpora of literature.

Philippe Guillaume maintained that scribes during the second century BCE in Alexandria inserted Judges into the Deuteronomistic History, reflecting the ideological needs of the Hasmonean rulers in Palestine. Judges was inspired by Hesiod’s Works and Days, especially the section on the heroes, which Hesiod inserted into the four ages of metal. This parallels how Judges was inserted into the Deuteronomistic History. Stories about heroic judges before David and Solomon undermine the claims of the Davidic Dynasty, which, in turn, helped the Hasmonean dynasts who had no Davidic ancestry behind their claims of messianic rule (147-64).

Katherine Stott observed that the rise of David, as depicted in 1 Samuel 16-31 and 2 Samuel 1-8, might be inspired by the narrative that describes the ascendancy of Cyrus to the throne of Persia and Media in the text of Herodotus’ Histories. She saw the following parallels: 1) Cyrus and David have humble beginnings, 2) they enter the court of the previous king, 3) that king is jealous of both young men, 4) they are threatened with death by that king, 5) they flee the court, 6) they become leaders, 7) there is a defection of an ally, 8) they usurp rule of the kingdom, 9) they succeed due their military prowess, 10) the old king’s life is spared for a time, 11) there is a tragic element in the fall of the previous king, and 12) the result is the formation of a new political entity. Stott noted that only in the Hellenistic era would this Greek text have been available for the biblical author (62-71, 77-78).

Daniel Hawk noted that the Orestia of Aeschylus and 1 Samuel 8 through 2 Kings 8 share similar structure and characters. Both have a tripartite scheme and use metaphors to reflect the transition from a kinship society to a civic society. Agamemnon and Saul reflect the old order, Orestes and David show the transition, and Athena and Solomon inaugurate the new order. The Deuteronomistic Historian used the Orestia as a model for his “received traditions concerning the Israelite monarchy.” Hawk believed the Hellenistic era would have been the time when the biblical author had access to the writings of Aeschylus.

Articles have been written by some scholars which speak in general terms of how Hellenistic literature shaped the Primary History after 300 BCE or even after 200 BCE in the Maccabean era.

Gerhard Larsson observes that there are great similarities between Berossus (Babyloniaca) and the biblical narratives about the creation of humanity, the flood, and ancient rulers with great longevity. Manetho (History of Egypt) divides history into significant eras, as does the biblical history. Larsson concluded that the biblical accounts were created in Ptolemaic Egypt during the second century BCE and influenced by significant third century BCE Greek historians such as Berossus, Manetho, and Eratosthenes.

Emanuel Pfoh believed that though the Primary History was created in the Hellenistic era, some traditions did come from the Assyrian and Persian eras and were developed by scribes over the years. But essentially the text was shaped under Hellenistic influence (23, 33-35).

Etienne Nodet affirmed that the Pentateuch arose in the early third century BCE, but the Prophets and some of the Writings were created in the second century BCE. These texts were generated in Alexandria under Hellenistic influence.

Finally, there are articles which focus on individual texts, or shorter segments of biblical literature. These studies are able to compare more closely biblical texts with classical texts in greater detail, and provide some concrete examples for the more general theories of authors just mentioned.

Hesiod’s Theogony and Catalogue of Women, in part, were influential sources respectively for the creation account in Genesis 1 and the geneaologies found throughout Genesis 1-11 (Gnuse 2017c).

Narratives in Genesis 1-11 can also be shown to have significant parallels with acounts recorded in Greek Historians, such as Hecateus of Miletus (Periegesis and Genealogies) and Herodotus of Halicarnassus (Histories), including references to human accomplishments (Gen 4: 20-22), the three sons of a flood hero who are ancestors of humanity (Gen 9:18-19; 10:1-32), and the planting of a vineyard (Gen 9:20-27) (Gnuse 2019a).

Older Latin traditions which lie behind the accounts in Ovid’s Fasti 5, 493-544 and Metamorphoses 8, 625-725 may have inspired the narratives of the messengers who tell Abraham of his coming son and the messengers who warn Lot to leave Sodom in Genesis 18:1-15; 19:12-26 (Gnuse 2017b).

A narrative about Democedes of Croton in Histories 3,125-132 of Herodotus may have given rise to the narrative about Joseph interpreting the dreams of the pharaoh in Gen 41:1-36, which in turn inspired the dream reports in the book of Daniel (Gnuse 2010a).

The short narrative about the noble talking horses of the great warrior Achilles in the Iliad 19, 395-424 may be loosely spoofed by the account of Balaam’s donkey in Num 22: 22-35, wherein a simple donkey shames a foolish prophet. Talking animals are far more common in Greek literature than the Bible (Gnuse 2017d).

The sacrifice of Iphigenia in two plays by Euripides around 400 BCE, Iphigenia among the Taurians and Iphigenia in Aulis, might have inspired the account of Jephthah’s sacrifice of his daughter in Judges 11:30, 34-40, which appears to be inserted into the account of Jephthah’s battles (Gnuse 2019b).

A great number of diverse Greek legends about Heracles appear to have influenced the Samson narratives in Judges 13-16, at a late date, most likely the Hellenistic era. There are far too many Greek parallels within these four chapters than can be dismissed as mere folkloristic coincidences (Gnuse 2018).

“The Rape of the Sabine Women” as an old tale recalled by Livy (History I, 9,1-16) and Plutarch (Lives: Romulus XIV, 2-8) may be the template for the abducted girls in Judg 21:1-24 (Gnuse 2007).

Arrian’s account of Alexander the Great and the spilt water in the Anabasis of Alexander 6.26.1-3 may have inspired a similar story of David in 2 Sam 23:15-17. David’s action of pouring out the water that his brave soldiers retrieved from behind enemy lines does not make a sensible story as does Alexander’s action in the Gedrosian desert where thirst is truly an issue (Gnuse 1998).

The narratives about Joseph, Balaam, and Jephthah may have been placed in the biblical text during the Persian period shortly after 400 BCE, as well as biblical texts in Genesis 1-11 with Hesiod, Hecateus, and Herodotus as sources of inspiration. but the other four narratives more likely seem to have a Hellenistic era origin. Ultimately, one might argue that all these texts arose in the Hellenistic era. Wajdenbaum discussed all of these same accounts, making many of the same observations and suggesting Hellenistic origins, but Gnuse provided greater detail in the analysis of the passages. These essays by Gnuse have collected together in a single volume (Gnuse 2020).

As we reflect on the evaluation of individual accounts that have received special attention by critical scholars, especially by Wajdenbaum and Gnuse, certain patterns seem to emerge as to which particular accounts might have been late and heavily influenced by Greek classical and Hellenistic narratives. There are those accounts found at the end of biblical books that appear to have been attached to the book with only a loose connection to the rest of the book. This is especially true in the book of Judges, where the Samson narratives of Judges 13-16 appear to have a completely different style than the rest of the book of Judges. Then the chapters that follow in Judges 17-21 have the appearance of an appendix to the rest of the book, and there we find the account of the women kidnapped from Shiloh. 2 Samuel 21-23 also appears to be an appendix, and herein we find David pouring out the water received from his warriors. Judges 13-21 and 2 Samuel 21-23 could have been added to the Deuteronomistic History at a very late date. The Joseph Novella in Genesis 39-50 is often seen as a late addition to the book of Genesis around 400 BCE or thereafter (consider, for example, the reference to coinage), so that the influence of Herodotus upon Joseph’s dream interpretation is likely. Other accounts also have the appearance of having been inserted somewhat unevenly into their narrative context. This is most evident with the account of Jephthah’s sacrifice of his daughter, which appears inserted into the middle of Jephthah’s battles in the Transjordan, and the narrative about Balaam and his donkey, which totally portrays Balaam with a different persona than is found in the rest of Numbers 22-24. The story of the three angels who visit Abraham and suddenly become only two in number when they visit Lot begs us to look at parallel Roman accounts in which there are three and two angels respectively in the narratives from Ovid. Furthermore, the nuanced details of the dialogue in Genesis 18-19 also betoken the writing style of a later age. Thus, the influence of Classical and Greek accounts seems most plausible in stories that appear to be later additions and insertions into the narrative sequence in the Primary History.

Where this scholarly research will go in the future is difficult to say. Will these minimalist conclusions become the future consensus of the scholarly guild or will these observations be forever connected to a few members of the Copenhagen School and be ultimately relegated to obscurity? Only time will tell.

Bibliography

Garbini, Giovanni. 1988. History and Ideology in Ancient Israel. Translated by John Bowden. New York: Crossroads.

———. 2003. Myth and History in the Bible. Translated by Chiara Paul. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 362. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

Gmirken, Russell. 2006. Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch. Library of the Hebrew Bible 433. Copenhagen International Seminar 15. London: T & T Clark.

———. 2014. “Greek Evidence for the Hebrew Bible.” Pages 56-88 in The Bible and Hellenism: Greek Influence on Jewish and Early Christian Literature. Edited by Thomas Thompson and Philippe Wajdenbaum. Copenhagen International Seminar. New York: Routledge.

———. 2017. Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible. New York: Routledge.

Gnuse, Robert. 1998. “Spilt Water: Tales of David (II Sam 23:13-17) and Alexander the Great (Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander 6.26.1-3).” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 12: 233-48.

———. 2007. “Abducted Wives: A Hellenistic Narrative in the Book of Judges?” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 22: 272-85.

———. 2010a. “From Prison to Prestige: The Hero who helps a King in Jewish and Greek Literature.” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 72: 31-45.

———. 2017b. “Divine Messengers in Genesis 18-19 and Ovid.” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 31: 66-79.

———. 2017c. “Greek Connections: Genesis 1-11 and the Poetry of Hesiod.” Biblical Theology Bulletin 47: 131-43.

———. 2017d. “Heed Your Steeds: Achilles’ Horses and Balaam’s Donkey.” International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Sciences 4 (6): 1-5.

———. 2018. “Samson and Heracles Revisited.” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 32: 1-19.

———. 2019a. “Greek Historians and the Primeval History.” International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Sciences 6 (1): 20-25.

———. 2019b. “Jephthah’s Daughter and Iphigenia in the Plays of Euripides.” International Journal of the Arts and Humanities 5 (1): 16-23.

———. 2020. Hellenism and the Primary History: The Imprint of Greek Sources in Genesis-2 Kings. Copenhagen International Seminar. London: Routledge.

Guillaume, Philippe. 2014. “Hesiod’s heroic age and the biblical period of the Judges.” Pages 146-64 in The Bible and Hellenism: Greek Influence on Jewish and Early Christian Literature. Edited by Thomas Thompson and Philippe Wajdenbaum. Copenhagen International Seminar. New York: Routledge.

Hawk, Daniel. 2003. “Violent Grace: Tragedy and Transformation in the Orestia and the Deuteronomistic History.” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 18: 73-88.

Larsson, Gerhard. 2004. “Possible Hellenistic Influence in the Historical Parts of the Old Testament.” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 18: 296-311.

Lemche, Niels Peter. 1993. “The Old Testament—A Hellenistic Book.” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 7: 163-93.

———. 1994. “Is It Still Possible to Write a History of Ancient Israel?” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 8: 163-88.

———. 2000. “Good and Bad in History: The Greek Connection.” Pages 127-40 in Rethinking the Foundations: Historiography in the Ancient World and in the Bible. Essays in Honour of John Van Seters. Edited by Steven McKenzie and Thomas Römer. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die altestamentliche Wissenschaft 294. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

———. 2001. “How Does One Date an Expression of Mental History?” Pages 200-224 in Did Moses Speak Attic? Jewish Historiography and Scripture in the Hellenistic Period. Edited by Lester Grabbe. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 317/European Seminar on Historical Methodology 3. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

———. 2008. The Old Testament between Theology and History. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox.

———2011. “Does the Idea of the Old Testament as a Hellenistic Book Prevent Source Criticism of the Pentateuch?” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 25: 75-92.

———. 2015. “When the End is the Beginning: Creating a National History?” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 29: 22-32.

Nielsen, Flemming. 1997. The Tragedy in History: Herodotus and the Deuteronomistic History. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 251. Copenhagen International Seminar 4. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

Niesiolowski-Spano, Lukasz. 2007. “Primeval History in the Persian Period?” Scandinavian Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 21: 106-26.

———. 2011. Origin Myths and Holy Places in the Old Testament. Translated by Jacek Laskowski. London: Equinox.

Nodet, Etienee. 2014. “Editing the Bible: Alexandria or Babylon?” Pages 36-55 in The Bible and Hellenism: Greek Influence on Jewish and Early Christian Literature. Edited by Thomas Thompson and Philippe Wajdenbaum. Copenhagen International Seminar. New York: Routledge.

Pfoh, Emanuel. 2014. “Ancient historiography, biblical stories and Hellenism.” Pages 19-35 in The Bible and Hellenism: Greek Influence on Jewish and Early Christian Literature. Edited by Thomas Thompson and Philippe Wajdenbaum. Copenhagen International Seminar. New York: Routledge.

Stott, Katherine. 2002. “Herodotus and the Old Testament: A Comparative Reading of the Ascendancy Stories of King Cyrus and David.” Scandinavian Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 16: 52-78.

Thompson, Thomas. 1999. The Bible in History: How Writers Create a Past. London: Jonathan Cape.

———. 1999. The Mythic Past: Biblical Archaeology and the Myth of Israel. New York: Basic Books.

Wajdenbaum, Philippe. 2010. “Is the Bible a Platonic Book?” Scandinavian Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 24: 129-42.

———. 2011. Argonauts of the Desert. Structural Analysis of the Hebrew Bible. Copenhagen International Seminar. Sheffield: Equinox.

Wesselius, Jan-Wim. 1999. “Discontinuity, Congruence and the Making of the Hebrew Bible.” Scandinavian Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 13: 24-77.

———. 2002. The Origin of the History of Israel: Herodotus’ Histories as Blueprint for the First Books of the Bible. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 345. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.”

https://bibleinterp.arizona.edu/articles/greek-literature-and-primary-history

Robert Karl Gnuse

Chair of the Department of Religious Studies

Loyola University New Orleans

Dr. Robert Gnuse is the James C. Carter, S.J./Bank One Distinguished Professor of the Humanities in the Religious Studies Department. He received his Ph.D. from Vanderbilt University in the area of Old Testament, and he is the author of 12 books and approximately 80 articles in the field of biblical studies. He has been at Loyola since 1980. Courses taught by him include Introduction to World Religions and various courses in the Bible.

Source: http://cas.loyno.edu/religious-studies/bios/robert-k-gnuse

So, as I see there is a whole school of academics who believe that the Old Testament as we know it today was composed at least partially during the Hellenistic times and under Greek influence, with Herodotus having a major role in this influence. Personally I am still rather inclined toward the more traditional point of view, which sees and understands the Bible mostly in a Near Eastern context. However, although of course I am not a Biblical scholar, I see with much interest the “Greek” approach of Pr. Gnuse and of the other authors of the same school of thought.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

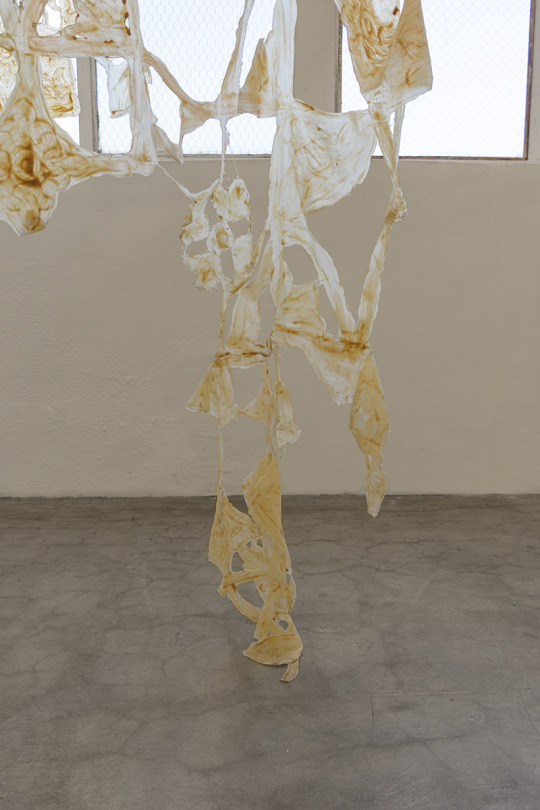

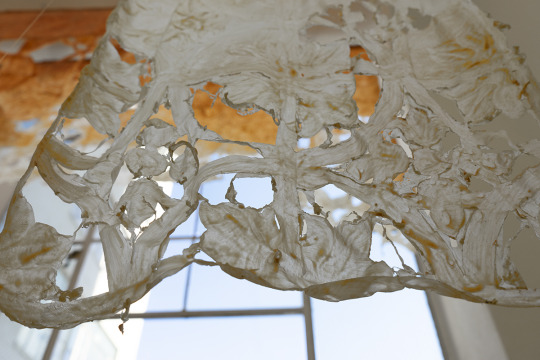

LA / Carlie Trosclair: a semblance of b r e a t h . . .

Carlie Trosclair: a semblance of b r e a t h . . .

November 19 - December 11, 2022

a semblance of b r e a t h . . .

a liminal space,

of longing between~

a living archive.

vignettes of time.

Tiger Strikes Asteroid LA is proud to present a semblance of b r e a t h . . . a solo exhibition by Carlie Trosclair. Approached through a lens of reordering and discovery, Trosclair’s work contemplates the living and transitional components of home. Architectural bodies carry with them the layered histories of previous residents. These become the shells we leave behind; Relics of habitation and home-making.

From structural cracks in a building, the palimpsest of paint, or footprint of rust these surfaces are connected by the ways they mark time. Echoes of the familiar are absorbed into the membrane of each latex body, crystallizing textures and detritus of place. Combining structure and fluidity with cycles of expansion and contraction, the narrative of home shape shifts from a secure space into one that is permeable and ephemeral: both structurally and in our memory.

Carlie Trosclair’s sculptural installations create new topographies and narratives that highlight structural and decorative shifts evolving over a building’s lifespan. Growing up in New Orleans as the daughter of an electrician, Trosclair spent her formative years in historic residential properties at varying stages of construction and deconstruction. She found that even when abandoned, the presence of the body still lingered. Reflexively her work reimagines the genealogy of home using latex as an architectural skin. Thin ghostlike imprints mark an in-between space that is transient and ever changing: both structurally and in our memory. Trosclair’s select artist residencies include: Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts (NE), Joan Mitchell Center (LA). Loghaven Residency (TN), Tides Institute & Museum of Art (ME), chashama (NY), Vermont Studio Center (VT), and The Luminary Center for the Arts (MO). Trosclair’s work has been featured in Art in America, The New York Times, ArtFile Magazine, and Temporary Art Review, among others. She is the recipient of the Riverfront Time‘s Mastermind Award, the Creative Stimulus Award, Regional Arts Commission Artist Fellowship and the Great Rivers Biennial Award. Trosclair earned an M.F.A from the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, a B.F.A from Loyola University New Orleans, and is an alumni of the Community Arts Training Institute in St. Louis.

photos by Gemma Lopez

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Loyola New Orleans Volleyball

#Loyola University New Orleans#LoyNO#LoyNO Wolfpack#volleyball girls#college volleyball#athlete#female athletes#college athlete#college girl#bikini#athletes in bikinis

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quiana Lynell (born April 16, 1981) is a blues and jazz singer, arranger and songwriter.

She was born in Tyler, Texas. During high school, she was in the all-state choir. She earned a BA in Vocal Performance from Louisiana State University.

She began her singing career as a classical singer and was a member of the St. James Episcopal Church choir in Baton Rouge. After meeting Janelle Brown, lead singer of the zydeco group 2 Da T, she began exploring additional musical genres, including zydeco and R&B. She has been mentored by notable artists such as Aaron Neville, Germaine Bazzle, and Wendell Brunious.

She won the Sarah Vaughan International Jazz Vocal Competition, she received a recording contract with Concord Records.

She has performed with Nona Hendryx, Terence Blanchard, Jon Cowherd, Marvin Sewell, Eric Harland, Herbie Hancock, Patti Austin, Bilal, and Ledisi, and with local artists and bands in Louisiana. She performs at venues in New Orleans and Baton Rouge, including at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. She has performed with the Baton Rouge Symphony Orchestra as a principal Soprano. She performed a tribute concert to Ella Fitzgerald, celebrating her 100th birthday. She was a featured artist with Bernard Purdie’s All-Star Shuffle, and Bobbi Humphrey, at Brooklyn Academy of Music’s R&B Festival in Brooklyn.

She released the EP Loving Me (Q Sound) and the single Baton Rouge (Q Sound). She has been a featured soloist on studio albums.

She has developed the educational program, “Made in America: Lyrically Speaking: Breaking Down Jazz, Blues, and Soul in American Music, from the Vocalist Perspective”, which has been used in clinics across the US to educate students on jazz, blues and traditional American music from the vocalist perspective. She is the founder of the running club, Musicians Run, aimed at promoting running to local musicians in Baton Rouge.

She has held several teaching positions, including as band director in elementary and middle schools. She has been a private vocal instructor and an adjunct professor at Loyola University New Orleans.

She has two children. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

Facebook

Another idea...

High School Year 1

1 - English II

2 - Geometry

3 - Biology I

4 - Career Orientation | Civics

* 5, 6, 7 - NOCCA - Violin

High School Year 2

1 - English III

2 - Algebra II

3 - Chemistry I

4 - World History

* 5, 6, 7 - NOCCA - Violin

High School Year 3

1 - English IV

2 - American History

3 - PE

4 - PE / Health

5 - NOCCA - Violin

College

Loyola University New Orleans

Violin Performance

BM, MM

I guess I'll go for a BM in Violin Performance at Loyola and the MM in Violin Performance there. I'm already a music student, just have to submit a violin audition and get accepted. I was also in Honors, which seems to be easier but maybe more "gifted" often and sometimes okay in many ways.

It's sad nothing else is involved, but there will be a lot involved in a college major itself. I was gonna do Composition, but to get a degree in an instrument is a lot to invest, too. The schedule is built around it. If I wanted to do something else later for some reason could work around, like conducting, which is often a Masters degree. I also really liked Music Education. You can get a Masters or Doctorate in that without a Bachelors, which there is only one or so schools with it online, The Baptist College of Florida is all I have now.

I want to be a top orchestral violinist, not a concert master, moreover but also a soloist. In fact, I want to be 2nd violin. I wonder what 3rd violin would be like.

0 notes

Text

Tuesday Issue

I graduated from Loyola University New Orleans and an issue with that is how massive my home sickness for the South is when the entire Internet shows me photos of how great was the Mardi Gras party I just missed. If I can’t get to my old apartment it is a reminder to get out to events more in the towns near me.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

"Bring Back the Good Ol' Days"

Should we bring back the days of MySpace, Twitter, the Facebook with apps, Photobucket, Flickr, YouTube, etc.?

My story is unique. I was going to college at Loyola University New Orleans, where I lived, and having the best of times. Suddenly, "out of nowhere," I was kicked out of my specific major of Music Education among other things I did, just because I didn't seem to fit, leaving me to think it's because I couldn't finish a hard piano piece I started that semester, as opposed to easier ones the semester before where I got an A. They acted like my college education was merely a favor to me to prove I could do it, and then I was disposed of like I could just go back to my parents's for good. I had various excursions that summer. I went to Catholic University of America to take a 3 credit hour course for 1 week in Foundations of Education. I didn't get enough to eat at their cafe and had to walk for to it, so I couldn't finish the course and got no grade. When school started at Loyola and I was probably an Organ Performance major I just realized just now, Hurricane Katrina hit and the schools closed the whole semester, offering a free Spring II, digging into the Summer. We moved to Orlando, Florida, where my dad had already gotten a job after 2 years, and my parents would split up so my younger brother could keep his connections. We didn't want to. We stayed with my aunt Barb, too. She always seemed to have a spare room or so, at least after awhile. I found 2 colleges with a dance minor, one in the Cleveland area and one in New Jersey. I chose Cleveland, not sure why. I was Up North and never lived there but have relatives there, in a neighboring state/area. They're my dad's mom's and all I know but not too well for long periods of time. So, I've made friends with girls from Up North living in Florida. The ones here asked me to go on MySpace and Friendster, I think, and maybe Facebook. I didn't. I didn't even have my phone number for later. It was nice, and I didn't have to take General Studies. If I go back would not take Music History. So, after not being successful wanting to return to Loyola, I went home and was on MySpace and Facebook 24/7 and IMDb and film|boards until now.

0 notes

Text

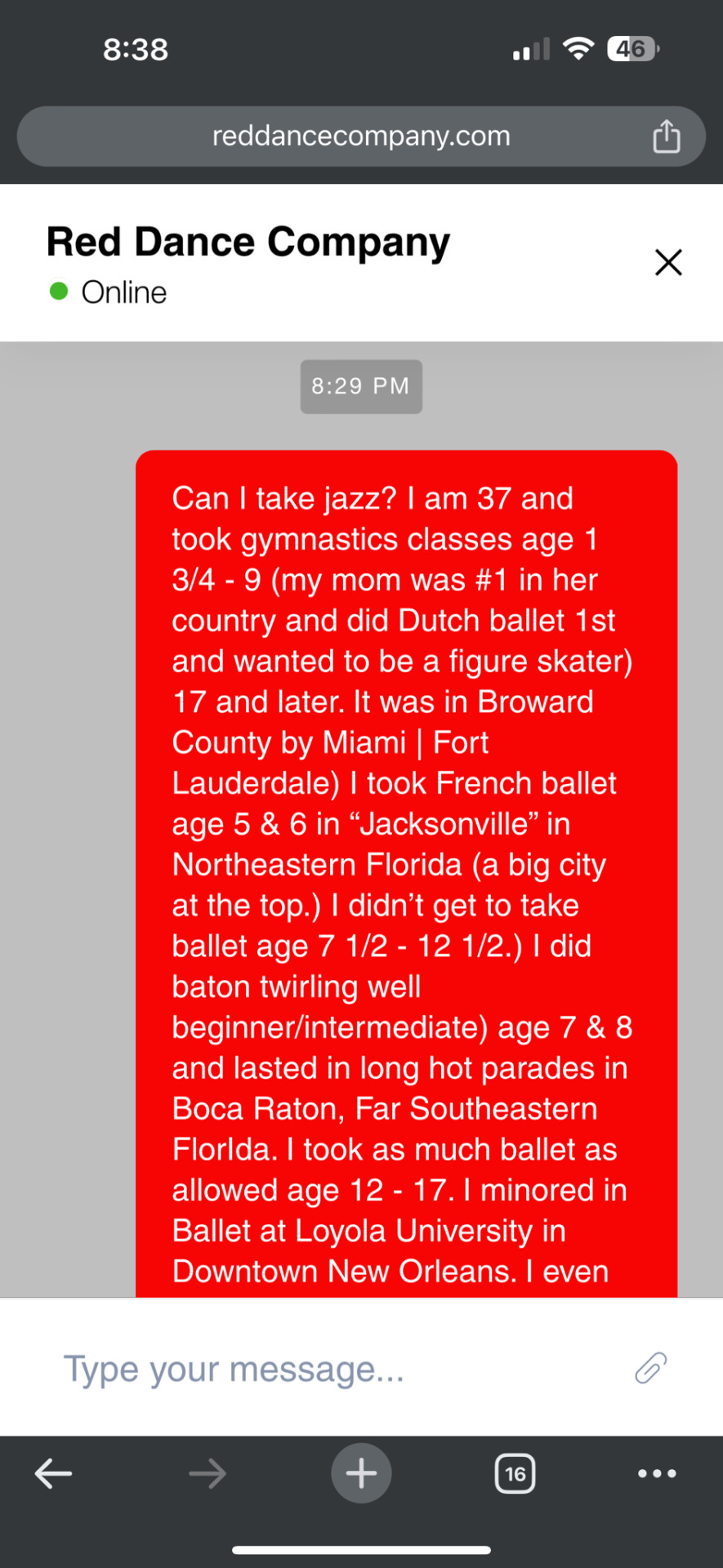

Request 🌹

(Complete Text “Screenshots” Below This Text)

k gymnastics classes age 1 3/4 - 9 (my mom was #1 in her country and did Dutch ballet 1st and wanted to be a figure skater) 17 and later. It was in Broward County by Miami | Fort Lauderdale) I took French ballet age 5 & 6 in “Jacksonville” in Northeastern Florida (a big city at the top.) I didn’t get to take ballet age 7 1/2 - 12 1/2.) I did baton twirling well beginner/intermediate) age 7 & 8 and lasted in long hot parades in Boca Raton, Far Southeastern FlorIda. I took as much ballet as allowed age 12 - 17. I minored in Ballet at Loyola University in Downtown New Orleans. I even added the preparatory program one semester my 2nd year. I had to go to ballet at 3 schools maybe 4 days a week age 20-21. I took a break to grow taller. I’ve jogged a lot slowly for a long time. I want to be in a company and be in The Nutcracker someday and looking at the ^sheep herder^. I also like the “Mother” dance if they do kids fancy. I like to study books and pictures of dance positions. I’m good at balancing tumbling and like trapeze solo best. If I ever did trapeze would like to be flexible and have a long spine with a tail. My feet point straight and I stand well with my feet together and don’t get dizzy spinning and need to look in the mirror. Another favorite is to match in a parade with pom poms and might ask the city. I can practice gymnastics alone in a “gym.”

0 notes

Text

Loyola University of New Orleans/Jesuit Social Research Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship in African American History and Mass Incarceration

Deadline:

Unstated; posted on H-Net 11/29

Length/Track:

Two years

Description:

“In addition to pursuing their own research agenda, the postdoctoral fellow will work to catalog the locations and descriptions of primary source materials related to the history of incarceration in Louisiana, ultimately creating a digital resource for humanities instructors to access and use these materials in…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

“Walker Percy of course did not ultimately embrace (fully, at least) Uncle Will’s blend of Stoicism, ethical Christianity, and eclectic mysticism. The challenges posed by his Southern, aristocratic roots would come to the fore in the 1950’s. Although he was not naturally a political animal, his interest in civil rights and social justice grew in this decade. He had always been compassionate and aware of the plight African Americans. Still, as Jay Tolson notes, not unlike most “white southerners of his class, he had believed that segregation was a necessary part of the southern way of life.” Reconstruction, after all, offered proof that legal and political solutions were inadequate. The racial problem, so he thought, was rooted in people’s hearts and would have to change slowly over time (250). He would begin to reconsider this presupposition in the early 1950’s. Perhaps the Southern Stoicism of Uncle Will carried dangers and prejudices not fully seen before. The influence of Shelby Foote can be detected in this realization, but even as Foote admitted, Percy’s Catholic faith played a more decisive role. As a convert, Percy took seriously the social message of the Gospels; he was aware of the mission of Dorothy Day, Fr. Louis Twomey, and Fr. Fichter at Loyola New Orleans, who produced a newspaper called “Christian Conscience.”[26] Although he would never become an activist in the strictest sense, “the words and actions of committed Catholic reformers forced him to question and revise his older assumptions about what needed to be done.” Add to this, the ruling on Brown v. Board of Education, the school desegregation in Little Rock, Arkansas, and his own brother Roy’s fight for civil rights in Greenville, Mississippi, Percy realized that the “old mixture of paternalism and well-intentioned gradualism was not enough.”[27]

Percy expressed his outrage in a Commonweal article entitled “Stoicism in the South.”[28] He began the article with an admission: “It is always hard to generalize about the South, harder perhaps for the Southerner, for whom the subject is living men, himself among them, than for the Northerner who, in proportion to his detachment, can the more easily deal with ideas” (83). He also expressed a dose of humility: “no white Southerner can write a j’accuse without making a mea culpa; no more is the average Northerner, either by the accident of his historical position or by his present performance, entitled to a feeling of moral superiority” (84).

One of the realities that Percy brings to light is that the South always had “a stronger Greek flavour than it ever had a Christian. Its nobility and graciousness was the nobility and graciousness of the Old Stoa.” He highlights the words of Marcus Aurelius as capturing the best of the South: “Every moment think steadily, as a Roman and a man, to do what thou hast in hand with perfect and simple dignity, and a feeling of affection, and freedom, and justice.” In relation to this tradition of Stoic virtues, the Beatitudes and the doctrine of the Mystical Body” sound rather foreign to Southern ears. “The South’s virtues,” Percy writes, “were the broadsword virtues of the clan, as were her vices, too—the hubris of noblesse gone arrogant.” As for the Christian layer, the “Southern gentleman did live in a Christian edifice, but he lived there in the strange fashion Chesterton spoke of, that of a man who will neither go inside nor put it entirely behind him but stands forever grumbling on the porch” (84). His allegiance was more to Pericles, Hector, and Marcus Aurelius, and less to Abraham and Paul: “When he named a city Corinth, he did not mean Paul’s community. How like him to go into Chancellorsville or the Argonne with Epictetus in his pocket; how unlike him to have had the Psalms” (85).

The Stoic way best suited to the agrarian landscape of the 19th century South. It was based on a particular hierarchical structure that could and did not survive. What survived was a “poetic pessimism” and “social decay” that privileged the “wintry kingdom of the self”—creating the conditions for different forms of human alienation and the vagaries of consumerism (85). The Stoic response in such a situation is “to sit tight-lipped and ironic while the world comes crashing down around him” (86). This response, as Percy submits, is a far cry from a Christian response; hence we have two rival traditions at work:

It must be otherwise with the Christian. The urban plebs is not the mass which is to be abandoned to its own barbaric devices, but the lump to be leavened. The Christian is optimistic precisely where the Stoic is pessimistic. What the Stoic sees as the insolence of his former charge—and this is what he can’t tolerate, the Negro’s demanding his rights instead of being thankful for his squire’s generosity—is in the Christian scheme the sacred right which must be accorded the individual, whether deemed insolent or not. For it was not the individual, after all, who was intrinsically precious in the Stoic view—rather, it was one’s own attitude toward him, and this could not fail to specified by the other’s good manners or lack of them. If he became insolent, very well: let him taste the bitter fruits of his insolence. The Stoic has no use for the clamoring minority; the Christian must have every use for it (86).

(…)

The Stoic-Christian Southerner is offended when the Archbishop of New Orleans calls segregation sinful (or discusses the rights of labor). He cannot help feeling that religion is overstepping its allotted area of morality. In the comfortable modus vivendi of the past, he had been willing enough to allow Christianity a certain say-so on the subject of sin—by which he understood misbehaviour in sexual matters, or in drinking and gambling. He is therefore confused and obscurely outraged when Christian teaching is applied to social questions. It is as if gentleman’s agreements had been broken. He does not want the argument on these grounds, but prefers to talk about a “way of life,” “states’ rights,” and legal precedents, or to murmur about Communism, left-wing elements, and infiltration (87).

(…)

Percy’s reckoning with the rival traditions of Stoicism and Christianity did not end in the mid 1950’s; it was a tension that surfaced sometimes in significant ways in his works of fiction. His National Book Award winning novel, The Moviegoer, just to take one example, portrays the protagonist Binx Bolling’s rejection of his influential Aunt Emily’s brand of Stoicism.[29] In a letter to Binx, Aunt Emily paraphrased the words of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus: to think at every moment “as a Roman and a man, to do what thou hast in hand with perfect and simply dignity, and a feeling of affection and freedom and justice” (78). Aunt Emily exhorted Binx to live a life of simply duty, to go to medical school, and to usefully serve humanity. She argued, in good Stoic fashion, that a “man must live by his lights and do what little he can and do it as best he can.” Although in this world “goodness is destined to be defeated,”—notice the tragic view—a man “must go down fighting”—a habit of mind that constitutes its own kind of victory (54). At the end of the novel, Aunt Emily, in her speech of abandonment to Binx, expresses dismay at his failure to fully embrace the “natural piety” of Stoicism on which he was raised. Binx’s love for Kate, in all her brokenness—drug use, suicidal tendencies, and paralyzing fear—violated Aunt Emily’s high hopes.

(…)

Whereas Aunt Emily’s tragic Stoicism—despite its noble intentions—nurtured a rejection of outcasts and an embrace of the defeat of goodness, Binx’s openness to the religious meaning of the ashes, which symbolize death and the salvific mystery of the cross, indicates the possibility of religious hope.

Conclusion

Nodding to the fabric of Stoicism that runs deep in American culture, this essay asked how one ought to navigate the relationship between these two systems of thought and modes of life. Rowe challenged us not to fall too easily into an easy blending of ideas and practices in the manner of a cosmopolitan modernity. A further question remains for me: How might such an integration look when grounded in an “authentic cosmopolitanism” or in global communitarian networks committed to cognitional, volitional, and existential authenticity? But this further question will have to wait. My limited claim is that we cannot ignore understanding these life-visions as robust rival traditions in MacIntyre’s sense of the term. They emerged historically as “ways of life”—as lived traditions of formation, practice, thinking, healing that stand in so many ways in existential and narrative rivalry. This existential and narrative rivalry came to life in the example of Walker Percy. Percy never renounced Stoicism tout court; in fact, he often defended its virtues. Still, it was not enough and did not offer him the resources for navigating the pressing questions and dilemmas that arose in his own life (and his region). Stoicism, after all, could not adequately resist his longstanding family heritage of melancholy, depression, and suicide. Nor could it rid him of the patriarchal and hierarchical deficiencies of slavery and racism in the South. The rivalry of traditions was captured in his community’s resistance to Brown v. Board of Education, in his literary dichotomy between Binx Bolling and Aunt Emily, and in his depiction of the Southern gentleman who lived surrounded by a Christian edifice, but who would not go inside. He was content, as Percy noted, to stand forever grumbling on the porch.”

1 note

·

View note