#U.S. Foreign Policy

Text

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Brett Wilkins

Common Dreams

April 5, 2024

"The Biden administration's ongoing support for Israel's genocidal policies implicates it directly in the relentless targeting and massacring of journalists in Gaza, including hundreds of our colleagues and their families."

Palestinian journalists this week issued an appeal to their U.S. counterparts urging them to boycott the April 27 White House Correspondents' Association dinner over the Biden administration's complicity in Israel's genocide in Gaza.

"In the past six months alone, the Israeli military has executed over 125 Palestinian journalists in Gaza—10% of Gaza's community of journalists," notes the appeal, which is being organized with the help of Adalah Justice Project and the U.S. Campaign for Palestinian Rights. "The year 2023 marked the bloodiest year for journalists worldwide in over a decade, with over 75% of killed journalists targeted by Israel’s attacks on Gaza."

"As Palestinian journalists, we urgently appeal to you, our colleagues globally, with a demand for immediate and unwavering action against the Biden administration's ongoing complicity in the systematic slaughter and persecution of journalists in Gaza," the authors wrote.

"We bear the enormous burden of exposing the realities of Israel's genocidal campaign to the world while living through it in real-time. Israel has killed more than 32,000 Palestinians as we watch on," the journalists said. The death toll in Gaza now exceeds 33,000—mostly women and children—with at least 75,550 other Palestinians wounded since October 7.

The appeal continues:

In Gaza, journalism is synonymous with putting our lives on the line as Israel methodically targets us in its desperate bid to silence our voices and obscure the grim reality of its genocidal actions and its project of ethnic cleansing in Palestine. For Palestinian journalists in Gaza, the blue press vest does not offer us protection, but rather functions as a red target.

The Biden administration's ongoing support for Israel's genocidal policies implicates it directly in the relentless targeting and massacring of journalists in Gaza, including hundreds of our colleagues and their families.

"Western media has played an integral role in manufacturing consent for Israel's ongoing violence against the Palestinian people, while obfuscating U.S. complicity," the journalists continued. "Over the past six months, the mainstream press has become the mouthpiece of the homicidal Israeli regime, promoting dehumanizing anti-Palestinian propaganda and platforming genocide apologists and perpetrators, while simultaneously ignoring, downplaying, and underreporting Israel's war crimes against Palestinians."

"The White House Correspondents' dinner is an embodiment of media manipulation, trading journalistic ethics for access," the appeal argues. "For journalists to fraternize at an event with President [Joe] Biden and Vice President [Kamala] Harris would be to normalize, sanitize, and whitewash the administration's role in genocide."

"As journalists reporting from the belly of the beast, you have a unique responsibility to speak truth to power and uphold journalistic integrity," the Palestinians implored U.S. journalists. "It is unacceptable to stay silent out of fear or professional concern while journalists in Gaza continue to be detained, tortured, and killed for doing our jobs."

The appeal's authors noted that American media professionals have demanded justice for journalists like Palestinian American Al Jazeera reporter Shireen Abu Akleh—who numerous probes found was intentionally killed by Israeli forces in 2022—and Jamal Khashoggi, the Saudi Washington Post columnist gruesomely murdered in 2018 by Saudi Arabian operatives in Turkey.

"It is past time journalists take action for journalists in Gaza," the Palestinians asserted. "We call on all journalists of conscience to stand with us and uplift our call to boycott the White House Correspondents' dinner."

#white house correspondents' association dinner#joe biden#u.s. foreign policy#journalism#israel hamas war#genocide#adalah justice project#jamal khashoggi#shireen abu akleh#u.s. campaign for palestinian rights#israel#gaza#palestine

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Once you’ve been to Cambodia, you’ll never stop wanting to beat Henry Kissinger to death with your bare hands. You will never again be able to open a newspaper and read about that treacherous, prevaricating, murderous scumbag sitting down for a nice chat with Charlie Rose or attending some black-tie affair for a new glossy magazine without choking. Witness what Henry did in Cambodia – the fruits of his genius for statesmanship – and you will never understand why he’s not sitting in the dock at The Hague next to Milošević."

- Anthony Bourdain on Henry Kissinger (1923-2023)

#henry kissinger#u.s. foreign policy#vietnam#cambodia#warmonger#war criminal#murderer#rot in hell#about damn time#thank god that son of a bitch is finally dead#good to know jimmy carter will get to outlive that scumbag piece of shit#somewhere in heaven anthony bourdain is smiling

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Except for Palestine Paperback Release

Except for Palestine Paperback Release

On May 31, the paperback version of Except for Palestine: The Limits of Progressive Politics by myself and Marc Lamont Hill will be released. If you were waiting for the paper version to get your copy, well, your time has come! Order it here from Uncle Bobbie’s Coffee and Books, Marc’s independent bookstore. If you already have one, tell your friends to buy it now.

You can see the description of…

View On WordPress

#Ahmad Abuznaid#BDS#Cornel West#Except for Palestine#Gaza#Khaled Elgindy#Lara Friedman#Marc Lamont Hill#Palestine#Peter beinart#Rashid Khalidi#U.S. Foreign Policy

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unveiling the Secret World of Privacy Breaches and Espionage Among Allies

**Introduction:**In a world where the lines between ally and adversary blur, the recent revelations of Google’s $5 billion settlement for infringing on user privacy and the intricate web of espionage among friendly nations have ignited a global conversation. This article delves into the clandestine world of privacy breaches and espionage, unearthing the uncomfortable truths that define our modern…

View On WordPress

#2023#Allies and Rivals#Corporate Accountability#Cybersecurity#Data Privacy#Digital Ethics#Digital Trust#Economic Espionage#espionage#France#Geopolitical Landscape#Germany#global economy#Google#Incognito Mode#International Relations#Privacy Breach#Strategic Dominance#Tech Industry#U.S. foreign policy#User Trust

0 notes

Text

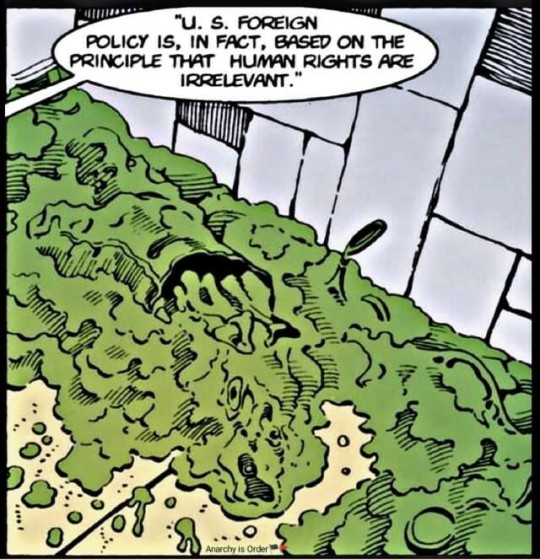

I don't know what comic this panel is from, but it speaks the truth about U.S foreign policy

#u.s. foreign relations#u.s. foreign policy#foreign policy#usa news#comics#comic#cartoons#cartoon#made in usa#usa#united states#unitedstateofamerica#unitedsnakes#united states of america#unitedstatesofhypocrisy#amerika#americans#native american#america#class war#classwar#humanrights#fascism#imperialism#fuck the gop#fuck the police#fuck the supreme court#fuck the patriarchy#ausgov#politas

0 notes

Text

How The World Sees Us ...

How The World Sees Us …

We’ve all heard people say that the United States is “the leader of the free world”, right? We grew up being told that we were that shining example of democracy that other nations hoped to emulate. Looking back, I don’t know if that was ever quite true, but I strongly suspect that at one point we were respected more than we are today. Until last night, I don’t recall ever reading anything by…

View On WordPress

#Christine Emba#Fareed Zakaria#Fred Upton of Michigan#Iraq War#January 6th attempted coup#Senator Bernie Sanders#the Big Lie#U.S. foreign policy

0 notes

Note

Why isn't "just move out" an acceptable answer to America's bad city planning?

"Just move" is, in general, a terrible answer to any large-scale economic/political problem, because it assumes where you live is totally fungible and moving is relatively low-friction--which ignores the cost of moving, of being separated from your social networks, assumes you are equally employable anywhere in the country, etc., etc.

But in this case--move where? Aside from a handful of cities, mostly in the northeast (which even then have in many cases been affected by similar urban planning issues, if not to the same degree--Robert Moses did tons of damage in NYC), every city in North America underwent a period of rapid expansion when the fiscally-unsustainable transport-neglecting school of urban planning was dominant such that every city in the country has the same issues. Some cities can endure the resulting condition a little better, for now, as a result of particular local circumstances--Nashville was one of the fastest-growing cities in the country for many years, and may still be (IIRC Sun Belt cities have in general had pretty good immigration numbers for the last decade at least)--but that doesn't make their planning policies wise. They could be doing a lot better!

And I know I've been accused of being some European snob who thinks everybody should do things the way they're done over here, but really, I don't think that dense, walkable, well-connected city planning in the US would necessarily result in cities that were carbon copies of European ones. The U.S. is different, has different cultural inclinations, and different geographic constraints--U.S. cities are always going to look different from cities in Europe, for the same reason they look different from cities in East Asia or w/e. But right now U.S. city planning is a major drag on both the economy and local government, and while shooting itself in the foot and somehow staggering on despite the injury is a very American thing to do, I want more for the U.S. and its people!

#sometimes i really do think americans could actually earn their smugness and sense of superiority#if they tweaked just a few things about city planning#government#and foreign policy#the U.S. could be a force for enormously positive change in the world!

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

At Davos, Blinken calls a pathway to a Palestinian state a necessity for Israeli security

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken reiterated the need for a “pathway to a Palestinian state” during a talk Wednesday at the World Economic Forum’s annual ...

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A newly released memo shows federal officials warned last spring that expanding a bilateral refugee pact to the entire Canada-U.S. border would likely fuel smuggling networks and encourage people to seek more dangerous, remote crossing routes.

Officials feared the development would also strain RCMP resources as irregular migrants dispersed more widely across the vast border.

The April memo, made public by Public Safety Canada through the Access to Information Act, was prepared in advance of a Cross-Border Crime Forum meeting with American representatives.

Under the Safe Third Country Agreement, implemented in 2004, Canada and the United States recognize each other as havens to seek protection.

The pact has long allowed either country to turn back a prospective refugee who showed up at a land port of entry along the Canada-U.S. border — unless eligible for an exemption — on the basis they must pursue their claim in the country where they first arrived. [...]

Continue Reading.

Tagging: @politicsofcanada, @vague-humanoid

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genuinely baffling to me how so many people seem to conflate Zionism and Judaism, seeing as the vast majority of Zionists in the U.S. are Christian...

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this date in 1973.

…and then two years later

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Absurd Plot: When International Espionage Meets Comedic Irony

In a world where reality often surpasses fiction, a recent U.S. indictment reads like a dark comedy script. Picture this: an Indian intelligence officer orchestrates an assassination plot, only to accidentally hire an undercover DEA agent as the hitman. The target? A Sikh separatist in New York. You can’t make this up!#### The Shadowy World of Espionage: Not So Smart After All?It’s a narrative…

View On WordPress

#2023#assassination plot#counter-intelligence#dark comedy#DEA agent#espionage#geopolitical irony#Global-Politics#India#India-U.S. relations#intelligence blunder#International Relations#Satire#Sikh separatist#transnational operations#U.S. foreign policy

0 notes

Text

“ Given present circumstances, there are three possible alternatives to the two-state solution [...]. First, Israel could expel the Palestinians from its pre-1967 lands and from the Occupied Territories, thereby preserving its Jewish character through an overt act of ethnic cleansing. Although a few Israeli hard-liners —including current Deputy Prime Minister Avigdor Lieberman— have advocated variants on this approach, to do so would be a crime against humanity and no genuine friend of Israel could support such a heinous course of action. If this is what opponents of a two-state solution are advocating, they should say so explicitly. This form of ethnic cleansing would not end the conflict, however; it would merely reinforce the Palestinians' desire for vengeance and strengthen those extremists who still reject Israel's right to exist.

Second, instead of separate Jewish and Palestinian states living side by side, Mandate Palestine could become a democratic binational state in which both peoples enjoyed equal political rights. This solution has been suggested by a handful of Jews and a growing number of Israeli Arabs. The practical obstacles to this option are daunting, however, and binational states do not have an encouraging track record. This option also means abandoning the original Zionist vision of a Jewish state. There is little reason to think that Israel's Jewish citizens would voluntarily accept this solution, and one can also safely assume that individuals and groups in the [American Israel] lobby would have virtually no interest in this outcome. We do not believe it is a feasible or appropriate solution ourselves.

The final alternative is some form of apartheid, whereby Israel continues to increase its control over the Occupied Territories but allows the Palestinians to exercise limited autonomy in a set of disconnected and economically crippled statelets. Israelis invariably bristle at the comparison to white rule in South Africa, but that is the future they face if they try to control all of Mandate Palestine while denying full political rights to an Arab population that will soon outnumber the Jewish population in the entirety of the land. In any case, the apartheid option is not a viable long-term solution either, because it is morally repugnant and because the Palestinians will continue to resist until they get a state of their own. This situation will force Israel to escalate the repressive policies that have already cost it significant blood and treasure, encouraged political corruption, and badly tarnished its global image.

These possibilities are the only alternatives to a two-state solution, and no one who wishes Israel well should be enthusiastic about any of them. Given the harm that this conflict is inflicting on Israel, the United States, and especially the Palestinians, it is in everyone's interest to end this tragedy once and for all. Put differently, resolving this long and bitter conflict should not be seen as a desirable option at some point down the road, or as a good way for U.S. presidents to polish their legacies and garner Nobel Peace Prizes. Rather, ending the conflict should be seen as a national security priority for the United States. But this will not happen as long as the lobby makes it impossible for American leaders to use the leverage at their disposal to pressure Israel into ending the occupation and creating a viable Palestinian state. “

John J. Mearsheimer, Stephen M. Walt, The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy; 1st edition by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, N.Y., 2007.

#John J. Mearsheimer#Stephen M. Walt#Middle East#politics#The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy#Israel#Palestine#Occupied Territories#Palestinians#ethnic cleansing#peace#two-state solution#extremism#jewish people#Israeli Arabs#crime against humanity#democracy#Zionism#South Africa#American Israel lobby#apartheid#Zionists#Cisgiordania#Palestinian territories#Gaza strip#West Bank#segregation#human rights violation#Palestinian refugees#nationalism

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"What Should It Look Like?" Part V: The Air Force

This essay was originally published on January 27, 2023 and is a continuation of the "What Should It Look Like?" series.

In this entry, we go into the DANGER ZONE and I explain how drones aren't going to solve everything (I go into some other stuff too but that's a big part of it).

(Full essay below the cut).

Greetings, folks. We return once more to my “What Should It Look Like” series and oh boy, it’s time to go Up into the Wild Blue Yonder with the United States Air Force.

Air power is one of the most important aspects of modern warfare. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that, in a large-scale war between two state armies, air power is essential for victory. As we’ve seen in Ukraine, even if you can just deny your enemy’s control of the air and prevent either side from gaining dominance – as Ukraine has, you can buy yourself some serious breathing room and seriously frustrate their efforts. In that particular case, ground-based air defense assets also play a major role – but as Ukraine consistently asking for more combat aircraft (among other things) has shown, the planes themselves remain important.

With the absolutely critical nature of airpower established early on in this essay, I’m going to give you all a warning: this is going to be another long one. Because of how important air power is in modern war and because of all the facets to it, it was hard for me to cut things out for this one because so much felt important. So, if you’re feeling a little drowsy, now is probably not the time to dive into this essay – unless you want to brew some coffee first. But if you’re ready, willing, and/or caffeinated, let’s dive right in.

Quality vs. Quantity (and vice versa)

In the scenario we’ve been using throughout this series (I won’t rehash it completely again, so you can go read the original essay to refresh your memory), aircraft play a crucial – if not, arguably, the most crucial role. In particular, tactical aircraft (“TACAIR”; i.e. “fighter” aircraft and other smaller combat aircraft) are essential due to the fact they can cross long distances quickly to get to the theater of war and immediately begin operations to slow and hopefully halt the enemy advance, by providing Combat Air Patrols (CAP) to contest enemy air superiority and Close Air Support (CAS) to friendly ground forces to hold back enemy forces, conducing Suppression of Enemy Air Defense (SEAD) missions to help secure air superiority by destroying enemy anti-air, and other missions. In the study that served as one of the sources of inspiration for this planning scenario we’re using, air power is flagged as absolutely critical (and the centerpiece of the study). Within the first week of conflict breaking out in this scenario, air power is arriving to take on all the missions I just described and more, and to set the stage for all other operations occurring and to follow. Without air power in general and TACAIR in particular, nothing else we’ve discussed or will further discuss can really happen.

In order for a country like the United States to be able to do what I just describe in support of our scenario, they need to generate something we call “mass.” Simply put, you need to be able to muster up enough of something to do the job – or in military terms, “create the effect” – that you want them to do, successfully. This is all being done while keeping in mind that you’re doing that while being opposed by a peer or near-peer adversary military. This probably won’t come as a surprise, but in that kind of scenario, you’re going to need to generate a lot of mass in terms of TACAIR given the amount they’ll have to do – and also factoring in the unfortunate reality of combat losses and other forms of attrition that inevitably occur in warfare.

Now, you’d think that probably wouldn’t be an issue for the United States, as it possesses one of the largest air forces on the planet (technically, it has four of them – in terms of total aircraft numbers – if you count the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps as well). But that’s increasingly becoming a problem for them for a variety of reasons – with two major ones standing out: a shortage of pilots, and an issue we call “gold plating.”

The USAF has been struggling with a persistent shortage of pilots, so much so that it’s had to force higher ranking officers to fly in more junior positions or even bring pilots back from retirement. A key driver for this has been an issue with retaining pilots, as many simply get tired of the poor quality of life and culture that the USAF imposes on them, turning to much more attractive offers from private sector airlines. The USAF has already attempted some changes here in terms of increasing that quality of life and doing more to support service members and their families in general.

My only real input or suggestion here would be to go further and not bite around the edges and half-ass it as the services are want to do. Like I said regarding the Navy and its toxic Surface Warfare culture, and with military culture in general, “if you build it, they will come.” Maybe if the Air Force follows that maxim, they’ll find themselves hemorrhaging less pilots. Also, I’m going to beat my usual drum here that “maybe if we weren’t a sprawling empire trying to be everywhere at once that the strain on the services would not be near as high – nor would the resulting demands on personnel.” Finally, I do (begrudgingly) have to admit there’s some areas where the Air Force could benefit from utilizing more drones in place of crewed aircraft (more on that later), but that still require skilled service members, so the retention and quality of life issue continues to take center stage. Just make it suck less for them. Easy.

Now that we got the boring “human” dimension out of the way, we can talk more about what we are really nerds for: hardware. Specifically, the over-designing of it, something we call in the biz “gold plating.” It’s a tale as old as time in my field, but since the end of the Cold War it’s gotten particularly bad. When designing new platforms and systems, the United States has had a tendency to give in to “scope creep” and try and make these new weapons do anything and everything under the sun – and do it the best they possibly can. The result is you get weapon systems that are insanely expensive to produce and maintain (if they even make it to production without being cancelled) and often come with a host of various technical issues to boot. You also are likely to end up with far fewer of what you need – as well as with expensive weapons that commanders may be risk averse in putting in dangerous situations because they don’t want to lose them. In addition to costing more, it also tends to take longer these days to develop and field a new weapon than it traditionally has, for a variety of reasons. All of these factors fly directly in the face (ha ha, flying pun) in the imperative of generating sufficient mass for TACAIR.

As an example of this gold plating issue, I’m going to bring up everyone’s favorite high-tech aviation punching bag: the F-35. I’ve already talked at length in a prior piece about the entire debacle of the F-35 Lighting II Joint Strike Fighter, so I’ll try not to just rehash that whole piece here and give you some highlights. One of my major takeaways in that piece is that, while a 5th generation multirole combat aircraft is by no means a dumb idea – and in fact, a necessary one in a future fight against a peer adversary, the USAF made a crucial mistake by going “all in” on the F-35 making up the vast majority of its TACAIR fleet of the future.

Why was this a mistake? Two main reasons: first, because the F-35 in particular is essentially a gold-plated camel (a camel, the old joke goes, being a “horse designed by committee”). While it is not completely useless (the original concept of a 5th generation multi-role fighter was and remains valid) and some of its issues have been fixed, the F-35 is still plagued with issues that are often surrounded by DoD obfuscation. It also remains incredibly expensive and finicky to maintain and sustain even when operating correctly and even as some costs have been brought down over time. The F-35 has been made to do try and do too many things all at once, turning it into a flying complex of software bugs that loves to try and kill its pilots.

Second, while stealth combat aircraft are absolutely crucial in a peer-on-peer conflict, they are by no means infallible. Stealth has never been invincible, even when the United States had a monopoly on the technology back when it was first introduced. This was evidenced by the shoot-down of a stealth F-117 Nighthawk over Serbia during NATO’s Operation Allied Force in 1999 – with another F-117 being hit as well (though that one managed to make it back to base without crashing). These attacks were undertaken with 1960s-era Soviet-made surface-to-air missiles and radars – which, when utilized correctly, could detect stealth aircraft. Technology has come a long way since the 1990s (or the 1960s for that matter). While some like to downplay the risk to U.S. stealth aircraft, it’s never as simple as they depict it. It’s not unreasonable to expect a technologically sophisticated peer adversary (like China) could develop tools enabling it to better find, fix, target, and attack stealth aircraft – if not now, in the near to mid future. Stealth absolutely has a use case but depending upon that as the sole advantage of a platform – or a fleet – at the expense of qualities like speed, range, maneuverability, payload, and more, is very risky.

Even without the risk, there are areas where you encounter situations where an expensive, high-end aircraft seems like overkill when it comes to the mission its undertaking. For example: why would you want to assign a high tech, penetrating stealth fighter to a mission like air defense of friendly territory? Why does it matter (outside of showing off) if the fighters you’re scrambling are stealthy or not when you know an enemy is on the way and they know you’ll scramble to meet them? In that case, what may matter more are sensors – either on board the aircraft or linked to it – and its ability to carry a lot of ordinance and fuel. The same could apply to stand-off strike or air defense missions where the aircraft doesn’t necessarily need to penetrate enemy air defenses to fire ordinance like long-range missiles. This is to say nothing of a fight against an adversary that isn’t as technologically advanced. A high-end stealth fighter isn’t required for every mission and there are efficiencies to be gained from an appropriate mix of high-end, more exquisite platforms, and less advanced platforms that you can get more of and do the job “alright” and may actually have advantages over high-end platforms in key areas like range or payload. We call that sort of thing a “high-low” mix in the biz and its nothing new.

The USAF also seems poised to potentially make this mistake again with its bomber fleet as it prepares to introduce the new B-21 Raider bomber that has been developed as a replacement for its B-1B Lancer and eventually for the B-2 Spirit bomber. In the B-21’s defense, while it is a high-end stealth bomber like the infamously expensive B-2 Spirit, it is (on paper) supposed to be far cheaper than that aircraft was (though it will also be smaller and thus have a smaller payload capacity). But the key question is, why does the majority of the USAF’s bomber fleet need to be made up of penetrating stealth bombers, when the enemy we plan on fighting against has a large air-defense network that is only growing larger and more sophisticated? Maybe having some of the bomber fleet be aircraft like B-21s makes sense, but is the juice really worth the squeeze in terms of having the majority of the fleet be made up of them?

This is one of those areas where the USAF may be doing the right thing at the same time its doing (maybe) the wrong thing, as at the same time its introducing the B-21 it is also preparing to keep the B-52 Stratofortress in service into the 2050s. With new engines giving it renewed life, the B-52 could be assigned to the role of primarily being a bus to carry long-range missiles it can fire at stand-off distance (though oddly enough it still can drop ‘dumb’ bombs and still practices how to do that which is kinda cool). While some instance sin war may call for a bomber that will attempt to penetrate enemy air defenses, do you really need every bomber to do that when what you may need more of is a big, dumb, missile bus that has a long range and long-range ordinance that can launch its ordinance and go home? Hell, we even thought about doing this with 747s back in the day (among other, crazier ideas) and I’m starting to wonder if we shouldn’t bring that idea back. Sometimes you need something expensive and stealthy, but sometimes you just need something big to carry stuff.

This is an area where we may be able to learn something from China’s approach to a high-low mix in combat aircraft, as they’ve been doing a lot of things that I think we should be doing. Even as they’ve designed and are now producing 5th generation fighters like the J-20 – and soon the smaller J-31/FC-31, an analogue to the F-35 that is also intended for export as well as domestic military use – they’ve continued to produce 4.5 generation fighters like the J-16 (a Chinese analogue to the Russian Su-35 “Flanker”) and the smaller and cheaper J-10 – another tactical aircraft that is also directed at the export market as well as the People’s Liberation Army. Even as they work to develop their own stealth bomber, they’re still actually producing new versions of the 1950s vintage H-6 “Badger” bomber that are capable of firing cruise missiles – and even air-launched ballistic missiles – in a role similar to that of the “missile bus” B-52 or 747 described prior. While appreciating the value of high end, low-observable aircraft, China seemed to hedge their bets in adopting that technology and now it may very well put them in a better position to generate mass in terms of airpower in a potential high-end conflict.

Ultimately, I don’t know what the right “high-low” mix is if you’re looking for an exact number – whether it be for bombers or fighters or whatever. That’s something that would need more careful study and examination than I can provide here. What I can say with some degree of confidence is that while high-end stealth aircraft definitely have a role, they probably should not make up the majority of a combat aircraft fleet. This is yet another area where the services – and the air force in particular – have either bit around the edges or danced back and forth on making the right choice. While the Air Force was planning on buying more of the 4.5 generation F-15EX, those buys are now being curtailed. And while the Chief of Staff of the Air Force identified a potential need for a “budget conscious” 4.5 generation fighter a couple years ago to replace aging F-16s, he then had the gall to claim in the same breadth to suggest that we need to do a “clean sheet” (i.e. brand new) design from scratch, taking up time, money, and my sanity in the process. This was despite the fact that, in addition to the F-15EX, we have other 4.5 generation fighters in production now in the form of the F/A-18E and the F-16V. Thankfully, it seems that the Air Force has now walked back this “clean sheet” idea and is instead looking at the more sensible plan of upgrading around 600 of its F-16s to this new model, but I swear to God sometimes the military makes me feel like I’m taking crazy pills with how they act.

I’m going to try desperately to wrap this section up now so I can move on to the next one by giving you a very high-level idea of what we should do regarding combat aircraft in general – both for TACAIR and for bombers (keeping in mind I don’t have exact numbers for you). First, buy fewer exquisite, gold-plated systems like the F-35 (while acknowledging you’re still going to need a fair amount of them). Second, buy more modernized versions of proven systems or upgrade packages to bring existing systems up to that standard. Third, and finally, for the love of God try not to make the same mistakes we’ve made with things like the F-35 and more when it comes to the new 6th Generation of TACAIR that is currently under development – in the form of Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) for the USAF and F/A-XX for the Navy. We literally cannot afford it – both in terms of money and resources, but also in terms of the potential consequences if we screw up yet again and create another gold-plated camel. Yes, systems like that are going to be expensive no matter what, but we can still do more to make it so they can be a bit more cost effective and at least be good value for money in doing their jobs well (and maybe not trying to actively kill their pilots in the course of doing their duties).

Droning on and on

Before I start off this section, I want to make something clear: I am not inherently anti-UAV (UAVs of course being Unmanned or Uncrewed Aerial Vehicles – commonly referred to as “drones”). As I will explain in this section, I think there are plenty of uses for drones in modern military operations and I would be pretty dumb and shortsighted to argue against their use whole-cloth. My issues with drones are with the idea of them taking on every role, replacing most – if not all – crewed aircraft. I am very firmly against this for both legal, ethical, and moral reasons, as well as concerns about the actual military risk involved from a variety of vectors. But I’ll got into that more shortly. I just wanted to put that disclaimer right up front.

Drones have already been a hot topic in every sense of the term since they came more into the public eye during the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), but they’ve become even more of a topic du jure in recent years due to their prominence in conflicts occurring in places like that between Yemen and the Saudi-led coalition on the Arabian Peninsula, between Armenia and Azerbaijan, within Ethiopia, and – of course, by both sides in Ukraine. Drones of various types have played key roles in those conflicts, and have been highly publicized in that regard, which has led a number of self-proclaimed “experts” to extrapolate from those conflicts to make sweeping generalizations and wild predictions about the future utility of drones in combat and the “obsolescence” of crewed aircraft and various other legacy military platforms.

The first thing you need to realize about drones in order to come to a more sensible understanding of their strengths and limitations, is that they are just aircraft that don’t have a person on board. That’s it. The first advantage they gain by not having a crew on board is that its more space you can add for other things like more fuel, sensors and optics, weapons, and more. The second obvious advantage of a drone is you can send it into dangerous situations without putting a human air crew in danger – which is good both in the sense that its nice when people don’t have to die, but also in that you’re not having to spend time, money, and energy to replace that air crew. You also have to realized that a lot of the footage we’ve seen of drones in combat on social media places like Ukraine – or really, combat footage we see in general – are brief snapshots in time of a particular aspects or moment in a war. You’re rarely seeing the whole picture, but it can be all too easy to make sweeping judgements based off of a series of these snapshots without additional context. This is something that all analysts can fall prey to.

Ok, so we’ve established that drones are a hot topic these days. We’ve established that a lot of big brains on the internet have very strong opinions about how great they are. While I could spend a whole essay writing about how they are dumb and wrong (and I probably will at some point – I’m surprised I haven’t already), now I’m going to jump to telling you why – in my opinion – it’s a bad idea for you to have an air force that is almost entirely drones, even if they should be used in some capacity for some roles.

First, it’s a bad idea because of the ethical, legal, and moral implications. I should clarify here that, when I’m talking about this, I’m talking specifically about full or partial automation of a drone and its decision-making process on using force, not just some guy piloting it from a shipping container in Arizona. Obviously, human beings are not infallible, and the United States has had more than its share of black stains on its soul for unpunished war crimes that occurred due to incompetence, malice, or what have you, when it comes to undertaking aerial warfare. That being said, a human – especially if they are properly trained and are coming out of an environment that doesn’t encourage them being a psychopath – is very likely to make decisions or judgement calls that an AI automated drone would not, like potentially showing mercy.

Second, having an entirely drone based air force is a bad idea due to the fact that drones – just like any aircraft or any military platform in general – have inherent weaknesses and shortcomings that a peer enemy will actively be trying to exploit. If you want a drone to fly more than a couple hundred kilometers away from the ground station that is controlling it by line-of-sight data-link, than you need satellites. With that in mind, the U.S. military has already made it abundantly clear that in a war against a peer adversary it is expecting all of its command, control, communications, and intelligence (C3I) capabilities to be disrupted by the adversary – especially space-based assets like satellites. This could make operating drones at long or short distances varying degrees of challenging to impossible.

This is to say nothing of the ways you can disrupt an individual drone aside from going after the broader C3I network enabling it. We’ve already seen insurgents hack U.S. reconnaissance drone feeds in the past, with Iran claiming to have done the same thing – and also claiming to have brought down a drone through hacking. Drones, just like any other computerized system reliant on outside data, are going to vulnerable to disruption, be it by hacking, or by electronic warfare (i.e. EW or “jamming”) disrupting its sensors, its datalink back to its command, or its link to the global positioning system so it doesn’t even know where it is, where it’s going or what time it is (yeah, GPS helps coordinate time; did you know that? Well now you do). Drones are not only just as vulnerable to these disruptions as any crewed platform, in some ways you could argue they are actually more vulnerable to them. A pilot in an aircraft should – if said pilot is properly trained and equipped – be able to respond to these disruptions in a way a drone is unable to. Putting all your eggs in one basket by not having any crewed aircraft that could do the same job seems like a huge liability to me.

A final subset of my second point here that I wanted to call out, is also the fact that true artificial intelligence (i.e., “AI”), still hasn’t been achieved and its arguable if it is even real or technically feasible or capable of making certain decisions. A lot of what passes for “AI” these days isn’t actually truly “AI” in the science-fiction case. What it usually amounts to is something “dumber” than an AI, or – as one of my favorite podcasts, Trashfuture, loves to point out: often is “just a guy” (in that it’s just a human doing the things you think AI is doing or faking that an AI is doing it). Additionally, what passes for AI today (and is arguably not actually AI) is also surprisingly easy to trick or fool or lull into patterns that may not be helpful, even without hitting it with hacking or jamming. Just look at how we’ve made “AI” sexist and racist just by interacting with them. Suffice to say, full automation may not even be possible, or at least may not be possible for decades or generations, which is just another reason not to go all-in on drones as the backbone of an air force as they may not even be capable of doing the things that “Drone Bros” think they are (or at least won’t be able to do them worth a damn)

There are absolutely areas in which drones could take over a large amount of the work – if not all – from humans, that are primarily in combat support areas that don’t necessarily involve being a “trigger puller.” We’ve already seen this to a large extent with UAVs becoming the primary intelligence gathering aircraft for the US military – though we still retain a number of Cold War-era platforms like the famous U-2 “Dragon Lady” spy plane.

But intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) aren’t the only areas where drones can either lighten the load or take it over. Take airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) aircraft that help direct fighter aircraft at incoming threats. Those are typically converted airliners that require a large number of skilled personnel to man, and in a wartime scenario would be in high demand with a lot of strain placed on them. Those traditional AEW&C platforms could be supplemented by drones equipped to do the same role. You could also purpose task AEW&C drones to be on the lookout for certain threats over others, like missiles and stealth aircraft. As early as 2015, China had already built a prototype UAV that could fulfill an AEW&C role. The same idea has been mooted in the US – though it’s been met with some degree of skepticism by traditionalists (I should be one to talk though I suppose). The bigger point here though, is even if AEW&C UAVs can’t do the job quite as well as a legacy platform and don’t replace them entirely, they could be assigned to lower risk areas to monitor for aerial threats to allow the more capable crewed platforms to operate in higher-priority areas. And remember how I was talking about drones being vulnerable to EW? Well, turns out they could actually be used to dish it out as well as take it – another thing that China has been working on.

This is the logic I extend to drones in combat too – in the limited capacity that I would accept them as such. When it comes to combat, the main contribution that drones could make is not replacing crewed aircraft, but by supplementing and supporting them. This is the idea of the “loyal wingman” Uncrewed Combat Aerial Vehicle (UCAV), which is where you take several UCAVs and link them under the control of a pilot or aircrew in a crewed aircraft as they proceed on a mission. This is sort of the happy medium between letting drones do whatever they want, and not using them in combat roles at all. The drones have some amount of autonomy, but ultimately follow the orders of the crewed aircraft and don’t use lethal force without the crewed aircraft’s permission. Their role here is to supplement and augment the crewed aircraft to add that additional mass we talked about earlier that is necessary for a successful air campaign (especially if pilot shortages continue to persist). Losing a UCAV that is (ideally) cheaper to build than a plane and doesn’t result in the death or grievous injury of a pilot is also a more acceptable loss – especially when you’re going into a contested area.

This isn’t just about satisfying LME concerns or dealing with pilot shortages and losses, however. It’s also about hedging your bets and preventing yourself from being vulnerable. I already mentioned how drones and the C3I networks supporting them can be vulnerable to electronic warfare and hacking among other things, and that the U.S. military is preparing to fight a peer conflict with severe disruptions to C3I. By having a pilot flying with UCAVs and still being in the loop, that can mitigate some of these disruptions. If you can’t connect to a communications satellite to give a drone orders, it won’t matter as much because it’s not trying to contact a distant ground station, it’s trying to reach the fighter jet flying right next to it. Same applies if GPS is disrupted. A properly trained and equipped pilot can still use a compass and a map to get to their target, and the drones just need to tag along and follow them. It’s not foolproof, of course. Drones could still be disrupted in other ways that we’ve already covered earlier, but it reduces the degree to which drones could be disrupted. In a worst-case scenario, if the “loyal wingmen” fail completely, you still have one or two crewed aircraft that can respond to a developing situation more dynamically and make a judgement call on whether to continue on mission or not. It’s about making sure you have redundancy and haven’t gone “all in” on something that is more vulnerable.

“…and The Rest!”

There’s only so much I can write about in these essays before they start to become a thesis or a book (though maybe I should write one someday). A good portion of this essay so far has been taken up by me discussing the high-low mix and drones. This was a conscious but difficult choice on my part to focus on these areas because I think these are two that are going to be highly consequential, but I didn’t want to allow you to talk away thinking those were the only main issues to consider when thinking about what an effective air force should look like in the future for the type of scenario we’ve been using as our benchmark.

For our scenario, strategic airlift (i.e., long-range cargo planes) will play a key role. While most of the troops, equipment, and materiel will get to a warzone by ship, airlift will play a key role in quickly transporting the first wave of combat troops into a theater, as well as other high-priority logistics. Airlift is an area in which the United States still is the undisputed champion, but while facing persistent issues. Like with many areas of the military, the airlift fleet has been operating at a high tempo as aircraft available have decreased. I feel the easy answer here is to reduce the strain put on the airlift fleet day today by the demand of constant global operations. This ties back to our overall philosophy of not being an imperial power and trying to enable allies and partners across the globe to provide for their own defenses as much as possible on a day-to-day basis so we don’t have to try and be everywhere at once and can reduce the demand on key assets like airlift – leaving more available for when a major war pops up.

I also find it kind of interesting now that strategic airlifters like the C-5 and C-17 are out of production that the United States is producing no heavy airlifters and there hasn’t yet been a serious discussion by the USAF of what comes after the C-5 and C-17. That’s definitely something to be thinking about, given how important airlift is and will remain – and perhaps an opportunity to incorporate nascent technologies allowing for fuel efficiency – which not only may ease financial and resource strain but could ease the strain on the environment.

Another key capability for this scenario are tanker aircraft. Capable of refueling other aircraft in mid-flight, tankers are essential to being able to fight across the globe. Without tankers, you’d have to rely on leapfrogging between various airfields to refuel and reach your destination – something that is neither efficient, nor would you be guaranteed access to. Again, this is an area where my main suggestion is to reduce the strain by trying to reduce our global footprint so we have more forces available for a major contingency, but this also an area where the main problem is not just imperialism but capitalism and the military industrial complex. Also, much like with airlifters, the USAF has had some issues here.

Trying to procure new tanker aircraft has been something of a white whale for the USAF for years. Its newest tanker – the Boeing KC-46 A Pegasus – has been plagued with technical issues with key refueling systems (as well as just generally shoddy production practices). Meanwhile, a decade’s long quest to try and procure an off-the-shelf “bridge” tanker before it designs a clean sheet tanker of the future has also faced an uphill climb and now may not even happen, with the possibly opting to buy more troubled KC-46As. This speaks to wider issues with both procurement and the state of the industrial base (both of which deserve essays in their own right – I’m deciding if they’ll occur in this series or not). One way or another though, given how critical tanker aircraft are to our scenario, its something that will need to be unscrewed and quickly if it is to be at all viable. We need tankers, and specifically we need tankers that actually work most of the time. Additionally, in regards to future tankers, much like with stealth bombers and “missile trucks” we’ll need to think about how many tankers need to be stealthy and fancy and how many just need to be big flying fuel tanks. Likewise, this is another area where drones can play a role to add additional mass – and already are, in fact.

Likewise, I think strategic forces (i.e., nuclear weapons) will need to be an essay in their own right due to the interdependent nature of the nuclear triad of land-based missiles, aircraft, and submarines. I actually suddenly realized as I was thinking about the USAF’s fleet of intercontinental ballistic missiles and aircraft-deployed nuclear bombs that I completely forgot to talk about this in my essay on the Navy and I mostly overlooked their ballistic missile submarines. I’m still figuring out the best way to broach my thoughts on nuclear weapons in general too, so that’s another reason I’m going to punt talking about them until a later date and stick to the conventional forces for now. Rest assured, however, that they will be addressed. Same with special operations forces, which I’m also going to be dealing with in a separate essay dealing with them as a whole across the joint force. So, stay tuned on that front.

I’m sure there are other things I’m missing, but as I repeatedly say, I’m trying to avoid writing a book here so I’m trying to limit myself to the most important concepts and capabilities – which are purely subjective opinions on my part. For example: I was reminded the other night that I haven’t really covered the culture issues within the USAF – in particular, its history with Evangelicalism and religion in general. I already touched on culture a bit in a more general sense in my recruitment essay that I linked earlier in this essay (what was that a thousand y ears ago?), but forgive me for not diving into it here in detail with how much this thing keeps growing. Very briefly: I think it’s a problem and that it needs to be dealt with – along with many other cultural issues in the Air Force and elsewhere (yet another thing to deal with in another essay).

At any rate, if I haven’t talked about whatever your area of expertise or hyper-fixation is in, I apologize. Rest assured, I probably think it’s important and something that we should have in the future, but there’s just only so much ground I can cover in one of these before both peoples’ eyes – including my own – start to glaze over. Sorry.

Finishing this up before I pass the hell out

I’ve been rambling on for what has to be an all-time War Takes record, so I’m going to keep this conclusion short and sweet.

I’ve already said it multiple times in the body of this essay: air power is essential to success in a modern war. While air power alone does not guarantee victory (something we’ve seen in wars past where one side tried to win almost solely through air power and found out the hard way that’s not possible), it cannot be achieved without it either. Control of the air is vital, and you need a large and robust mix of capabilities and competencies to do that – not just one “silver bullet” that happens to be the flavor of the week on Twitter.

If we’re at all serious in this fantasy better world I’m imagining of being able to reach across the globe to help like-minded allies and partners who come under attack in the spirit of democratic socialist internationalism, if we don’t build the proper air force for it there’s no point in bothering. Air power will be the first wave that will blunt the enemy attack and then set the conditions for a counterattack that will push them out of friendly territory and neutralize them as a threat for the immediate future. Air power is absolutely critical to the success of any campaign and I’m going to leave it at that before I repeat myself further.

That’s all for now. I know this one was a slog to write, but I hope it’s useful in some way to those of you who made it all the way to the end. After two years or so of writing this “What Should It Look Like” series, we’re (maybe) getting close to the end, so let’s hang in there and see if we can make. I’m gonna go turn my brain off for a bit after writing this, but as always, all of you stay safe out there until next time.

#essay#War Takes#War Takes Essay#leftism#leftist#socialism#democratic socialism#international relations#IR#national security#national defense#international security#foreign policy#foreign affairs#united states air force#usaf#us air force#U.S. Air Force#UAVs#unmanned aerial vehicles#drones#F-35#F-35 Lightning II#Joint Strike Fighter#Loyal Wingman

7 notes

·

View notes