#disney fox merger

Note

Big Wolf On Campus was such a great show! :D

Oh my Gosh, you watched it? People i know look at me like i have 5 heads when i bring up things i used to watch.

I think I used to watch a lot of the shows airing on that channel back in the day.

The kind of annoying show Angela Anaconda I believe was on that one, and like strange days at blake holesey high? which i think was canadian (rumored to have daniel clarks brother in it) and I saw a familiar face from one of those RFR or degrassi era crossover kinda kids on (or from lifetime movies), also a music driven talent kind of show with fergie's band wild orchid (? for clarity) which was pre-black eyed peas on most saturday mornings. i recall that show being ultra corny tbh, cringier than star search from the 90s, and lastly i remember some show about s club (a band at the time) where they'd sing and have random adventures in miami, florida for some reason and they're like European with thick euro accents but high energy singing and such, i loved them and was obsessed naturally, and still bop to them if they come on spotify.

At night like on my dinky vhs tapes, i would tune in or record movies like Casper meets Wendy (with a young Hilary Duff) or whatever they had on, during their October blocks of Halloweenish shows and films which they still do when they changed over to ABC family & now more recently Freeform.

Aw so nostalgic right now, such good times in the late 90's and early 2000's. Thanks for messaging me, I don't feel so alone in remembering that show.💌😊

#asks#stardustviolet#💌 tysm for the ask#i guess i wanna say with all this remember: i may love a lot shows made by canadians and stuff but i live in the USA lol#and like idk if these shows were made for us audien or were like brought to use thru merger like with the-n/teennick or viacom/abc idk tbh!#no clue tbh but yeah i'm american so i saw this stuff on cable#2000s#shows#tv#abc family#fox family#tadio disney used to play a lot of the music from these shows#especially sclub#i guess they had a deal with their record compay#idk if there were commercials#i no longer have those tape recordings#if i still do i have no vhs or why to convert#none of these shows are steaming haha#but like its just funny that some people share similar memories!#my friends and i used to make up dances for sclub songs when it was on#like we had legit crushes on the dudes#cringe#90s/00s era fox/abc family/freeform was so different/low budget than it is now#still plays 700 club at night and then i switch channels lmao idk don't wanna know! why do they do that?#might wanna rewatch the fosters soon though my bf and i were talking about it yesterday

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am the worlds luckiest comic book fan because every time a company has attempted to put one of my faves in a tv show or make a movie about them it gets stuck in production limbo and then dies before even beginning to film. I am loved

#chats#gambit channing tatum movie i am so glad you died in the disney-fox merger#i dont love that disney is a massive media conglomerate but um. thank u g-d for putting an end to that

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Let's give you Venom~

marvel character asks

venom: what non-mcu marvel character would you love to see in the mcu?

phoenix

phoenix

PHOENIX

MARVEL YOU HAVE X-MEN NOW PUT JEAN IN THE MOVIES GIVE ME A GOOD PHOENIX ADAPTATION I KNOW YOU CAN DO IT GIVE HER TO ME

#musings#cobaltstarling#bandit answers questions#meme response#am i still pissed at them for meddling in the last one because of captain marvel similarities and use of the skrull#and the disney-fox merger?#yes#BUT ALSO I WANT A GOOD PHOENIX ADAPTATION GIVE ME MY GIRL

0 notes

Text

CALL TO ACTION to support WGA/SAG-AFTRA: Submit a comment about the corporate monopoly crisis.

August 18, 2023: You can personalize the template message included in the above link, or simply just add your name & email. Seems like it's US only; please boost if you can't sign yourself.

From the WGA:

"More than 100 days into our strike, as we continue to fight for the sustainability of our profession, events in Washington, D.C. provide an opportunity for writers to shine a light on one of the root causes of the strike: media consolidation.

For decades, the WGA has advocated for stronger antitrust oversight, bringing attention to the ways that mergers and vertical integration in our industry – from AT&T-Time Warner to Warner Bros.-Discovery to Amazon-MGM to Disney-Fox – have consolidated the power of our employers and harmed writers as well as the diversity of content.

In numerous reports and policy filings – including a new report called The New Gatekeepers: How Disney, Amazon and Netflix Will Take Over Media, released yesterday – the WGA has documented the threat to our industry from past and future consolidation and called for more aggressive antitrust enforcement.

Our current strike highlights the urgency of the issue; studios gained power through anti-competitive consolidation and vertical integration and then used that power to push down wages and impose more precarious working conditions for writers while profiting off of their work, and currently – together – refuse to bargain a fair contract for writers to mitigate those harms.

Last month, the FTC and DOJ jointly released proposed revisions to their Merger Guidelines, a policy document designed to guide law enforcement around consolidation. These new Draft Guidelines are part of an effort by these agencies to reinvigorate antitrust enforcement. Compared with prior versions of Merger Guidelines, they give significantly more weight to the ways that mergers can be harmful and, for the first time, explicitly direct agencies and courts to consider how mergers can hurt workers.

The Draft Guidelines have been released for public comment, and the FTC and DOJ want to hear from people who have been affected by consolidation – people like you.”

The FTC and DOJ are accepting comments on their revisions of the Merger Guidelines until September 18.

#sag-aftra strike#sag strike#actors strike#fans4wga#union solidarity#wga strong#sag-aftra strong#i stand with the wga#wga strike#writers strike

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Disney: So Wanda is the antagonist of MoM. She wants to steal her children from another universe-

Fans: Oh I get it! It’s like a reverse “House of M”, right? Wanda tries to pull Billy and Tommy into her universe, and accidentally brings mutants into the MCU, easily integrating the X-Men franchise you got the rights to from the Fox merger with the Avengers. That explains why Professor X is in the movie.

Disney: Oh. No, that isn’t it…

Fans: Oh. Well, what’s the plot of MoM then?

Disney:

#don’t get me wrong i liked the movie a lot but this is what i would’ve done#ds mom spoilers#doctor strange#multiverse of madness#scarlet witch#wanda maximoff#x-men#mcu#marvel

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

Monday, July 3.

Nimona! *spoilers*

*WARNING! Major spoilers for Nimona follow.*

It's colorful, queer, and finally here. Trials and tribulations can make the victories all the sweeter, or so we are told. Only it seems there is some proverbial proof in the pudding: #nimona has finally made its way to Netflix after something of a bumpy ride, to put it lightly—and we are here for it. It's been a long time coming, too, with years and years spent in development hell.

Since its inception in June 2015, the film has survived a mega media merger between The Walt Disney Corporation and 20th Century Fox Animation (and delayed twice); in February 2021, one year before its projected release, Disney announced it was shutting down Blue Sky Studios, and production of the film was canceled entirely; it was then revived by Annapurna and Netflix; experienced several changes in creative leadership and a global pandemic (you may have heard of it) and a studio shutdown just as the film was finally coming together.

Now, the story that started life in ND Stevenson's beloved webcomic finally has made its way into silver screen heaven with its arrival on Netflix these past days. And it seems the dashboard's faultlessly loyal, long-time fandom can't get enough of this wild, wonderful, and life-affirming adaption.

#today on tumblr#nimona#nimona netflix#nimona film#ambrosius goldenloin#nimona comic#nimona spoilers#spoilers nimona#nimona spoiler#nimona movie#nd stevenson

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Deadline’s Read the Screenplay series spotlighting the year’s most talked-about scripts continues with Nimona, Netflix‘s animated feature based on ND Stevenson’s 2015 National Book Award-nominated graphic novel about finding friendship in the most surprising situations and accepting yourself and others for who they are.

Nick Bruno and Troy Quane (co-directors of Spies In Disguise) directed the film, which was adapted by Big Hero 6 scribe Robert L. Baird and Spies co-writer Lloyd Taylor and features the voices of Riz Ahmed and Chloë Grace Moretz in the lead roles. Frances Conroy, Lorraine Toussaint, RuPaul Charles, Eugene Lee Yang, Indya Moore, Sarah Sherman and Beck Bennett also have voice roles.

A family-focused film with authentic queer themes set in a vibrant techno-medieval world (credit to teams at Blue Sky Studios and DNEG Animation), the plot centers on Ballister Boldheart (Ahmed), a knight in a futuristic medieval world, who is framed for a crime he didn’t commit. The only one who can help him prove his innocence is Nimona (Moretz), a mischievous teen with a taste for mayhem — who also happens to be a shapeshifting creature Ballister has been trained to destroy.

Baird and Taylor said their main challenge in the adaptation was to stay true to Stevenson’s story while morphing it from the episodic form of the novel to a feature-length narrative – in itself a process of shapeshifting that mirrors one of the novel’s core themes.

Nimona, which was just nominated for Best Animated Film at the Critics Choice Awards, had a long path to travel to get to its world premiere at the Annecy Animation Festival in June, followed by a theatrical run ahead of its release on Netflix on June 30.

Then-20th Century Fox’s Blue Sky originally optioned Stevenson’s novel the year it was published, and the project moved forward despite the Disney-Fox merger and then the pandemic. But it almost didn’t survive a third blow: Disney shuttered Blue Sky in April 2021, halting Nimona mid-production.

Blue Sky principals Baird and Andrew Millstein kept pushing on the the project however and eventually found a partner in Annapurna’s Megan Ellison, who sparked to its themes. Baird and Millstein became EPs and created Shapeshifter Films to complete the movie, which then landed at Netflix. The pair have since joined Ellison at her company, forming Annapurna Animation.

Click here to read the script.

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

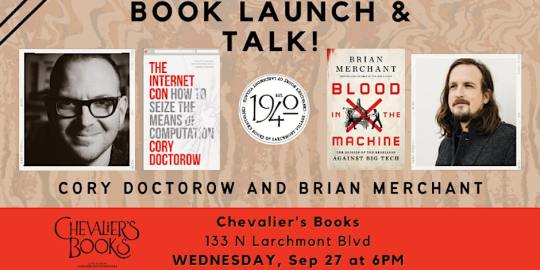

On September 22, I'm (virtually) presenting at the DIG Festival in Modena, Italy. On September 27, I'll be at Chevalier's Books in Los Angeles with Brian Merchant for a joint launch for my new book The Internet Con and his new book, Blood in the Machine.

It's been 21 years since Bill Willingham launched Fables, his 110-issue, wide-ranging, delightful and brilliantly crafted author-owned comic series that imagines that the folkloric figures of the world's fairytales are real people, who live in a secret society whose internal struggles and intersections with the mundane world are the source of endless drama.

Fables is a DC Comics title; DC is division of the massive entertainment conglomerate Warners, which is, in turn, part of the Warner/Discovery empire, a rapacious corporate behemoth whose screenwriters have been on strike for 137 days (and counting). DC is part of a comics duopoly; its rival, Marvel, is a division of the Disney/Fox juggernaut, whose writers are also on strike.

The DC that Willingham bargained with at the turn of the century isn't the DC that he bargains with now. Back then, DC was still subject to a modicum of discipline from competition; its corporate owner's shareholders had not yet acquired today's appetite for meteoric returns on investment of the sort that can only be achieved through wage-theft and price-gouging.

In the years since, DC – like so many other corporations – participated in an orgy of mergers as its sector devoured itself. The collapse of comics into a duopoly owned by studios from an oligopoly had profound implications for the entire sector, from comic shops to comic cons. Monopoly breeds monopoly, and the capture of the entire comics distribution system by a single company – Diamond – was attended by the capture of the entire digital comics market by a single company, Amazon, who enshittified its Comixology division, driving creators and publishers into Kindle Direct Publishing, a gig-work platform that replicates the company's notoriously exploitative labor practices for creative workers. Today, Comixology is a ghost-town, its former employees axed in a mass layoff earlier this year:

https://gizmodo.com/amazon-layoffs-comixology-1850007216

When giant corporations effect these mergers, they do so with a kind of procedural kabuki, insisting that they are dotting every i and crossing every t, creating a new legal entity whose fictional backstory is a perfect, airtight bubble, a canon with not a single continuity bug. This performance of seriousness is belied by the behind-the-scenes chaos that these corporate shifts entail – think of the way that the banks that bought and sold our mortgages in the run-up to the 2008 crisis eventually lost the deeds to our houses, and then just pretended they were legally entitled to collect money from us every month – and steal our houses if we refused to pay:

https://www.reuters.com/article/idINIndia-58325420110720

Or think of the debt collection industry, which maintains a pretense of careful record-keeping as the basis for hounding and threatening people, but which is, in reality, a barely coherent trade in spreadsheets whose claims to our money are matters of faith:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/08/12/do-not-pay/#fair-debt-collection-practices-act

For usury, the chaos is a feature, not a bug. Their corporate strategists take the position that any ambiguity should be automatically resolved in their favor, with the burden of proof on accused debtors, not the debt collectors. The scumbags who lost your deed and stole your house say that it's up to you to prove that you own it. And since you've just been rendered homeless, you don't even have a house to secure a loan you might use to pay a lawyer to go to court.

It's not solely that the usurers want to cheat you – it's that they can make more money if they don't pay for meticulous record-keeping, and if that means that they sometimes cheat us, that's our problem, not theirs.

While this is very obvious in the usury sector, it's also true of other kinds of massive mergers that create unfathomnably vast conglomerates. The "curse of bigness" is real, but who gets cursed is a matter of power, and big companies have a lot more power.

The chaos, in other words, is a feature and not a bug. It provides cover for contract-violating conduct, up to and including wage-theft. Remember when Disney/Marvel stole money from beloved science fiction giant Alan Dean Foster, whose original Star Wars novelization was hugely influential on George Lucas, who changed the movie to match Foster's ideas?

Disney claimed that when it acquired Lucasfilm, it only acquired its assets, but not its liabilities. That meant that while it continued to hold Foster's license to publish his novel, they were not bound by an obligation to pay Foster for this license, since that liability was retained by the (now defunct) original company:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/04/30/disney-still-must-pay/#pay-the-writer

For Disney, this wage-theft (and many others like it, affecting writers with less fame and clout than Foster) was greatly assisted by the chaos of scale. The chimera of Lucas/Disney had no definitive responsible party who could be dragged into a discussion. The endless corporate shuffling that is normal in giant companies meant that anyone who might credibly called to account for the theft could be transfered or laid off overnight, with no obvious successor. The actual paperwork itself was hard for anyone to lay hands on, since the relevant records had been physically transported and re-stored subsequent to the merger. And, of course, the company itself was so big and powerful that it was hard for Foster and his agent to raise a credible threat.

I've experienced versions of this myself: every book contract I've ever signed stipulated that my ebooks could not be published with DRM. But one of my publishers – a boutique press that published my collection Overclocked – collapsed along with most of its competitors, the same week my book was published (its distributor, Publishers Group West, went bankrupt after its parent company, Advanced Marketing Services, imploded in a shower of fraud and criminality).

The publisher was merged with several others, and then several more, and then several more – until it ended up a division of the Big Five publisher Hachette, who repeatedly, "accidentally" pushed my book into retail channels with DRM. I don't think Hachette deliberately set out to screw me over, but the fact that Hachette is (by far) the most doctrinaire proponent of DRM meant that when the chaos of its agglomerated state resulted in my being cheated, it was a happy accident.

(The Hachette story has a happy ending; I took the book back from them and sold it to Blackstone Publishing, who brought out a new expanded edition to accompany a DRM-free audiobook and ebook):

https://www.blackstonepublishing.com/overclocked-bvej.html

Willingham, too, has been affected by the curse of bigness. The DC he bargained with at the outset of Fables made a raft of binding promises to him: he would have approval over artists and covers and formats for new collections, and he would own the "IP" for the series, meaning the copyrights vested in the scripts, storylines, characters (he might also have retained rights to some trademarks).

But as DC grew, it made mistakes. Willingham's hard-fought, unique deal with the publisher was atypical. A giant publisher realizes its efficiencies through standardized processes. Willingham's books didn't fit into that standard process, and so, repeatedly, the publisher broke its promises to him.

At first, Willingham's contacts at the publisher were contrite when he caught them at this. In his press-release on the matter, Willingham calls them "honest men and women of integrity [who] interpreted the details of that agreement fairly and above-board":

https://billwillingham.substack.com/p/willingham-sends-fables-into-the

But as the company grew larger, these counterparties were replaced by corporate cogs who were ever-more-distant from his original, creator-friendly deal. What's more, DC's treatment of its other creators grew shabbier at each turn (a dear friend who has written for DC for decades is still getting the same page-rate as they got in the early 2000s), so Willingham's deal grew more exceptional as time went by. That meant that when Willingham got the "default" treatment, it was progressively farther from what his contract entitled him to.

The company repeatedly – and conveniently – forgot that Willingham had the final say over the destiny of his books. They illegally sublicensed a game adapted from his books, and then, when he objected, tried to make renegotiating his deal a condition of being properly compensated for this theft. Even after he won that fight, the company tried to cheat him and then cover it up by binding him to a nondisclosure agreement.

This was the culmination of a string of wage-thefts in which the company misreported his royalties and had to be dragged into paying him his due. When the company "practically dared" Willingham to sue ("knowing it would be a long and debilitating process") he snapped.

Rather than fight Warner, Willingham has embarked on what JWZ calls an act of "absolute table-flip badassery" – he has announced that Fables will hereafter be in the public domain, available for anyone to adapt commercially, in works that compete with whatever DC might be offering.

Now, this is huge, and it's also shrewd. It's the kind of thing that will bring lots of attention on Warner's fraudulent dealings with its creative workforce, at a moment where the company is losing a public relations battle to the workers picketing in front of its gates. It constitutes a poison pill that is eminently satisfying to contemplate. It's delicious.

But it's also muddy. Willingham has since clarified that his public domain dedication means that the public can't reproduce the existing comics. That's not surprising; while Willingham doesn't say so, it's vanishingly unlikely that he owns the copyrights to the artwork created by other artists (Willingham is also a talented illustrator, but collaborated with a who's-who of comics greats for Fables). He may or may not have control over trademarks, from the Fables wordmark to any trademark interests in the character designs. He certainly doesn't have control over the trademarked logos for Warner and DC that adorn the books.

When Willingham says he is releasing the "IP" to his comic, he is using the phrase in its commercial sense, not its legal sense. When business people speak of "owning IP," they mean that they believe they have the legal right to control the conduct of their competitors, critics and customers:

https://locusmag.com/2020/09/cory-doctorow-ip/

The problem is that this doesn't correspond to the legal concept of IP, because IP isn't actually a legal concept. While there are plenty of "IP lawyers" and even "IP law firms," there is no "IP law." There are many laws that are lumped together under "IP," including the big three (trademark, copyright and patent), but also a bestiary of obscure cousins and subspecies – trade dress, trade secrecy, service marks, noncompetes, nondisclosues, anticirumvention rights, sui generis "neighboring rights" and so on.

The job of an "IP lawyer" is to pluck individual doctrines from this incoherent scrapheap of laws and regulations and weave them together into a spider's web of tripwires that customers and critics and competitors can't avoid, and which confer upon the lawyer's client the right to sue for anything that displeases them.

When Willingham says he's releasing Fables into the public domain, it's not clear what he's releasing – and what is his to release. In the colloquial, business sense of "IP," saying you're "releasing the IP" means something like, "Feel free to create adaptations from this." But these adaptations probably can't draw too closely on the artwork, or the logos. You can probably make novelizations of the comics. Maybe you can make new comics that use the same scripts but different art. You can probably make sequels to, or spinoffs of, the existing comics, provided you come up with your own character designs.

But it's murky. Very murky. Remember, this all started because Willingham didn't have the resources or patience to tangle with the rabid attack-lawyers Warners keeps kenneled on its Burbank lot. Warners can (and may) release those same lawyers on you, even if you are likely to prevail in court, betting that you – like Willingham – won't have the resources to defend yourself.

The strange reality of "IP" rights is that they can be secured without any affirmative step on your part. Copyrights are conjured into existence the instant that a new creative work is fixed in a tangible medium and endure until the creator's has been dead for 70 years. Common-law trademarks gradually come into definition like an image appearing on photo-paper in a chemical soup, growing in definition every time they are used, even if the mark's creator never files a form with the USPTO.

These IP tripwires proliferate in the shadows, wherever doodles are sketched on napkins, wherever kindergartners apply finger-paint to construction-paper. But for all that they are continuously springing into existence, and enduring for a century or more, they are absurdly hard to give away.

This was the key insight behind the Creative Commons project: that while the internet was full of people saying "no copyright" (or just assuming the things they posted were free for others to use), the law was a universe away from their commonsense assumptions. Creative Commons licenses were painstakingly crafted by an army of international IP lawyers who set out to turn the normal IP task on its head – to create a legal document that assured critics, customers and competitors that the licensor had no means to control their conduct.

20 years on, these licenses are pretty robust. The flaws in earlier versions have been discovered and repaired in subsequent revisions. They have been adapted to multiple countries' legal systems, allowing CC users to mix-and-match works from many territories – animating Polish sprites to tell a story by a Canadian, set to music from the UK.

Willingham could clarify his "public domain" dedication by applying a Creative Commons license to Fables, but which license? That's a thorny question. What Willingham really wants here is a sampling license – a license that allows licensees to take some of the elements of his work, combine them with other parts, and make something new.

But no CC license fits that description. Every CC license applies to whole works. If you want to license the bass-line from your song but not the melody, you have to release the bass-line separately and put a CC license on that. You can't just put a CC license on the song with an asterisked footnote that reads "just the bass, though."

CC had a sampling license: the "Sampling Plus 1.0" license. It was a mess. Licensees couldn't figure out what parts of works they were allowed to use, and licensors couldn't figure out how to coney that. It's been "retired."

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/sampling+/1.0/

So maybe Willingham should create his own bespoke license for Fables. That may be what he has to do, in fact. But boy is that a fraught business. Remember the army of top-notch lawyers who created the CC licenses? They missed a crucial bug in the first three versions of the license, and billions of works have been licensed under those earlier versions. This has enabled a mob of crooked copyleft trolls (like Pixsy) to prey on the unwary, raking in a fortune:

https://doctorow.medium.com/a-bug-in-early-creative-commons-licenses-has-enabled-a-new-breed-of-superpredator-5f6360713299

Making a bug-free license is hard. A failure on Willingham's part to correctly enumerate or convey the limitations of such a license – to list which parts of Fables DC might sue you for using – could result in downstream users having their hard work censored out of existence by legal threats. Indeed, that's the best case scenario – defects in a license could result in downstream users, their collaborators, investors, and distributors being sued for millions of dollars, costing them everything they have, up to and including their homes.

Which isn't to say that this is dead on arrival – far from it! Just that there is work to be done. I can't speak for Creative Commons (it's been more than 20 years since I was their EU Director), but I'm positive that there are copyfighting lawyers out there who'd love to work on a project like this.

I think Willingham is onto something here. After all, Fables is built on the public domain. As Willingham writes in his release: "The current laws are a mishmash of unethical backroom deals to keep trademarks and copyrights in the hands of large corporations, who can largely afford to buy the outcomes they want."

Willingham describes how his participation in the entertainment industry has made him more skeptical of IP, not less. He proposes capping copyright at 20 years, with a single, 10-year extension for works that are sold onto third parties. This would be pretty good industrial policy – almost no works are commercially viable after just 14 years:

https://rufuspollock.com/papers/optimal_copyright.pdf

But there are massive structural barriers to realizing such a policy, the biggest being that the US had tied its own hands by insisting that long copyright terms be required in the trade deals it imposed on other countries, thereby binding itself to these farcically long copyright terms.

But there is another policy lever American creators can and should yank on to partially resolve this: Termination. The 1976 Copyright Act established the right for any creator to "terminate" the "transfer" of any copyrighted work after 30 years, by filing papers with the Copyright Office. This process is unduly onerous, and the Authors Alliance (where I'm a volunteer advisor) has created a tool to simplify it:

https://www.authorsalliance.org/resources/rights-reversion-portal/

Termination is deliberately obscure, but it's incredibly powerful. The copyright scholar Rebecca Giblin has studied this extensively, helping to produce the most complete report on how termination has been used by creators of all types:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/10/04/avoidance-is-evasion/#reverted

Writers, musicians and other artists have used termination to unilaterally cancel the crummy deals they had crammed down their throats 30 years ago and either re-sell their works on better terms or make them available directly to the public. Every George Clinton song, every Sweet Valley High novel, and the early works of Steven King have all be terminated and returned to their creators.

Copyright termination should and could be improved. Giblin and I wrote a whole-ass book about this and related subjects, Chokepoint Capitalism, which not only details the scams that writers like Willingham are subject to, but also devotes fully half its length to presenting detailed, technical, shovel-ready proposals for making life better for creators:

https://chokepointcapitalism.com/

Willingham is doing something important here. Larger and larger entertainment firms offer shabbier and shabbier treatment to creative workers, as striking members of the WGA and SAG-AFTRA can attest. Over the past year, I've seen a sharp increase in the presence of absolutely unconscionable clauses in the contracts I'm offered by publishers:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/06/27/reps-and-warranties/#i-agree

I'm six months into negotiating a contract for a 300 word piece I wrote for a magazine I started contributing to in 1992. At issue is that they insist that I assign film rights and patent rights from my work as a condition of publication. Needless to say, there are no patentable inventions nor film ideas in this article, but they refuse to vary the contract, to the obvious chagrin of the editor who commissioned me.

Why won't they grant a variance? Why, they are so large – the magazine is part of a global conglomerate – that it would be impractical for them to track exceptions to this completely fucking batshit clause. In other words: we can't strike this batshit clause because we decided that from now on, all out contracts will have batshit clauses.

The performance of administrative competence – and the tactical deployment of administrative chaos – among giant entertainment companies is grotesque, but every now and again, it backfires.

That's what's happening at Marvel right now. The estates of Marvel founder Stan Lee and its seminal creator Steve Ditko are suing Marvel to terminate the transfer of both creators' characters to Marvel. If they succeed, Marvel will lose most of its most profitable characters, including Iron Man:

https://www.reuters.com/legal/marvel-artists-estate-ask-pre-trial-wins-superhero-copyright-fight-2023-05-22/

They're following in the trail of the Jack Kirby estate, whom Marvel paid millions to rather than taking their chances with the Supreme Court.

Marvel was always an administrative mess, repeatedly going bankrupt. Its deals with its creators were indifferently papered over, and then Marvel lost a lot of the paperwork. I'd bet anything that many of the key documents Disney (Marvel's owner) needs to prevail over Lee and Ditko are either unlocatable or destroyed – or never existed in the first place.

A more muscular termination right – say, one that kicks in after 20 years, and is automatic – would turn circuses like Marvel-Lee/Ditko into real class struggles. Rather than having the heirs of creators reaping the benefit of termination, we could make termination into a system for getting creators themselves paid.

In the meantime, there's Willingham's "absolute table-flip badassery."

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/09/15/fairy-use-tales/#sampling-license

Image:

Tom Mrazek (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:An_Open_Field_%2827220830251%29.jpg

CC BY 2.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

--

Penguin Random House (modified)

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/707161/fables-20th-anniversary-box-set-by-bill-willingham/

Fair use

https://www.eff.org/issues/intellectual-property

#pluralistic#fables#comics#graphic novels#dc#warner#monopoly#publishing#chokepoint capitalism#poison pills#ip#bill willingham#public domain#copyright#copyfight#creative commons#licenses#copyleft trolls

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watched Nimona. That was a really good movie! On the one hand, absolutely crazy that Disney scrapped it after the Fox merger. On the other hand, seeing the end result, I'm kind of glad that it got to a different studio. Would Disney have been able to do this justice? They still think "don't get married on first sight" is edgy critique and subversion of fairy tales that deserves a standing ovation.

This one is way more out there, partly in subject matter, partly in how gay it is, but perhaps most notably in style and in how crazy it allows itself to get. The details of Nimona's character and her weird friendship with Bal are at least as important to the story as its overall message of accepting people who are different, if not more so.

I had previously read some of Nimona back when it was still a webcomic (this made me finally go out and buy the graphic novel that it became). This is certainly very different in both content and style, but everything about it feels like an appropriate and very fun take on the subject matter.

Anyway, go watch it. Very fun, very energetic and anarchic and a lot of fun. Lovely subway station as well.

(This movie is what my previous post is about, by the way. The city behind the walls that does not trade with anyone and doesn't seem to grow its food anywhere does not make any objective sense, but it's perfect from a thematic point of view.)

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

275 - The Woman in the Window (Patreon Selects)

We're wrapping up our run of Patreon Selects episode with a real doozy! Originally intended for 2019, The Woman in the Window was meant as a prestige adaptation of a popular thriller, packing quite the pedigree. With the attached talents of director Joe Wright, writer Tracy Letts, and star Amy Adams (along with a stellar supporting cast), the film follows an agoraphobic who witnesses a murder across the street, setting off a mystery of mistaken identities and skewed perceptions of reality. Then, it was hit by a rapid succession of misfortunes including the Disney-Fox merger, a cringe-inducing exposé on author A.J. Finn, and, well, the pandemic.

This episode, we talk about what went wrong and what might have been watered down by the Tony Gilroy reshoots. We also discuss Adams' recent run of disappointing roles, our hopes for Nightbitch later this year, and Jennifer Jason Leigh joins our Six Timers Club!

Topics also include the emergence of Fred Hechinger, Julianne Moore's brief boozy performance, and the film's somewhat unceremonious Netflix drop.

The 2021 Academy Awards

Vulture Movies Fantasy League

#The Woman in the Window#Joe Wright#Amy Adams#Julianne Moore#Fred Hechinger#Jennifer Jason Leigh#Gary Oldman#Brian Tyree Henry#Tracy Letts#Anthony Mackie#Wyatt Russell#AJ Finn#thrillers#movies#Academy Awards#Oscars

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I see people getting mad at Deadpool 3 being unable to have improvised lines because of the strike, I think of how people were also mad at the Disney-Fox merger because they were "afraid" that Deadpool would have to be toned down, now that he's a Disney character.

I don't know, it's a bit funny how there's people that put "a major shake-up is occurring in the movie industry" on one side of the scale, and then "Ryan Reynolds in a red and black superhero costume might not be as funny as he should be" on the other, and somehow act like the heavier side is the second.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

In a move that surely made the Succession theme play in the heads of all who got the push notification, Rupert Murdoch announced today that the “time is right” for him to step down as chair of Fox Corporation and News Corp, ending his seven-decade reign as mastermind of the media landscape. His retirement won’t begin until November, but the great unbundling of his media empire has already begun.

Still, what an empire it is, or was. Murdoch, 92, got his start at 21 years old, when his father died and left him in charge of his relatively small Australian newspaper company. On taking the helm, he upped circulation by shifting their coverage to be more tabloidy. Throughout the 1960s and ’70s he continued to build that portfolio, gobbling up everything from The Sun in the UK to The Village Voice and New York magazine in the US.

By the 1980s, Murdoch was casting his gaze toward film and TV, taking over regional news stations and the movie studio 20th Century Fox. The Fox broadcast network launched in 1986, Fox News a decade later. By the early aughts, Murdoch set his sights on new media, writing a Scrooge McDuck–sized $580 million check to then-superhot social network Myspace.

Soon, a spark lit a fuse that set the whole dumpster on fire.

It’s an easy shorthand to say “Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp ruined discourse,” but that’s also not far from the truth. (The notion of “truth” is also something Murdoch’s empire has had a hand in destabilizing.) News Corp ownership effectively ruined Myspace, making way for platforms like Facebook and Twitter to host the public square, but the influence of Murdoch and his companies spread regardless. As WIRED reporters Vittoria Elliott and Peter Guest noted earlier this year, Fox News hosts like Tucker Carlson “helped bring often dangerous misinformation into the mainstream around the world.” Murdoch may have never controlled Facebook or Twitter, but the people his companies platformed dominated the conversation on them anyway.

“For Rupert Murdoch, all of his media empire was a way of trying to push certain ideas,” says Dan Cassino, a professor of government and politics at Fairleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey.

In the US, this was most evident in the way Fox News wed itself with the Trump administration, a marriage that was for a long time beneficial to both parties but also led to Fox News agreeing to pay $787 million to settle a lawsuit from Dominion Voting Systems that “would have exposed how the network promoted lies about the 2020 presidential election,” as the Associated Press put it. It also led to revelations that Carlson, in the lead-up to the January 6 insurrection, sent texts saying that he hated Trump “passionately.” Carlson was canned by Fox News in April.

Murdoch newspapers in the UK backed Brexit and got caught up in a phone hacking scandal. In Australia, where his family’s news empire still holds massive influence, Murdoch periodicals showed skepticism about climate change. Today, as news spread that Murdoch was stepping down, Angelo Carusone, the CEO of watchdog group Media Matters for America, issued a statement saying, “The world is worse off because of Rupert Murdoch. No one should sugarcoat the damage he caused.”

Still, the empire Murdoch built, though vast, is dwindling. Murdoch pushed out Roger Ailes, the man behind the ascent of Fox News, in 2016. (Ailes died a year later.) News Corp sold off 21st Century Fox to Disney in 2019 for $71.3 billion. (Fox News and the Fox broadcast network were spun off into Fox Corporation as a result of the deal.) As of this summer, News Corp profits are down 75 percent year over year. As the media industry goes through a series of massive shake-ups ranging from the Warner Bros. and Discovery merger to the increasing dominance of Apple and Amazon, everything is getting unbundled and rebundled, including Murdoch’s empire.

Not that Murdoch hasn’t tried to have a hand in how those bundles come together. Murdoch abandoned a plan earlier this year to consolidate Fox Corporation and News Corp, a move he said could give the entertainment and publishing business better scale, after shareholders opposed it. “Fox is certainly diminished,” Carusone says. “I don’t think they’re going to be able to keep this big thing together.”

When Murdoch steps down in the fall, his son, Lachlan, will become chair of News Corp and remain Fox Corporation’s CEO and executive chair. (Cue the “eldest boy” memes.) It remains to be seen where Lachlan will take the empire from here or whether he’ll be able to maintain the same hold on political messaging as his father. Following the transition, Rupert Murdoch plans to stay on as chair emeritus of the companies, and in a message to his staff today said that in his new role he would still “be involved every day in the contest of ideas.” Perhaps, though, with his empire shrinking, that contest will no longer be an all-out war.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone might ask me about this for next year’s QnA, but what the heck.

My immediate thoughts regarding the tentative Warner/Paramount merger.

I’m no business expert, but I’m educated enough to know that merging two already huge media companies will be a bad thing for workers. Remember what happened when Disney bought Fox 5 years ago? Content from both companies has become more homogeneous since then.

Just thinking about the idea that Cartoon Network and Nickelodeon could share the same parent company has me worried. They’ve already been dealing with identity crises since the streaming bubble took people’s attention away from cable, and if they both have the same executives controlling them, that’ll just make the situation worse. Think about how low their viewership has gotten in the past decade. If they’re both under the control of the same company, one or both of them will have the plug pulled. And with Cartoon Network Studios shutting down recently, I bet it’s going to be them.

I’m spitballing here, getting paranoid over a hypothetical outcome that only exists in my head right now, but if Cartoon Network is no longer a studio, channel or active brand identity by 2025 or 2026, that’ll make me really sad. Sure I don’t follow their new stuff as much as I review their old stuff, but I focus on their old stuff for a reason. It’s a symbol of the animation renaissance of the late 80s, 90s and early 2000s. The medium was in crisis before then, but an impassioned new wave of animators brought it back, with the help of a business tycoon and his channel that actually saw value in the art form. I can’t see that happening again when there’s less companies and less job opportunities for animators. Time isn’t always cyclical. This could very well be the end what we currently consider the Modern Era of Animation.

And the possibility of Warner Bros. owning SpongeBob has me even more concerned about its future. They could do one of two things:

-Cancel everything in the franchise as a tax write-off (can you blame anyone for thinking they’ll do that?)

-Dip even harder into movies and spin-offs, making Nickelodeon’s current strategy seem quaint

Here’s the thing. I wouldn’t be so apprehensive about movies (beyond the first two) and spin-offs if the main show was over already. I’m not saying Season 13 and 14 are bad and shouldn’t exist, just that Nickelodeon should only be doing one or the other, the main show or subsequent media. At this point, I’ve come to terms that SpongeBob is like Mickey Mouse and Looney Tunes, this animated mascot that’s outlived the creator and so will always be a symbol of the corporation it came from. But notice how with Mickey Mouse and Looney Tunes, their original serieses ended decades and decades ago. We’ve been getting spin-offs, film appearances and complete reimaginings for far longer than their original theatrical shorts were in production.

I’m fine with SpongeBob still being around as a mascot in 50 years like them, but not if the show is going to be in its 44th season and a virtually different production with different people behind it. There is the likelihood that Warner Bros. Discovery Paramount will look at the ratings it’s getting on Nick and put it to rest, leaving behind spin-offs and reimaginings. As harsh as it is to say, that’s the safest possible outcome, but I don’t think that’ll be what they do. They’ll either do even more to oversaturate the brand, or throw it all away like it’s worthless. Sorry if this spiel has been pretty cynical, but I have no reason to be optimistic if this goes through.

The only thing people are excited about with all this is all the crossover possibilities if all the NickToons and Cartoon Network Originals were owned by the same people. And while they seem tantalising, those old franchises were only so good because the creators were encouraged to compete, encouraged to experiment, encouraged to make what they wanted to watch, and encouraged to leave a lasting impact. If the merger goes through, that might not be the case. Crossovers are literally the only positive people seem to be gleaming from this, so fair enough. Have those happy thoughts, because you’re really gonna need them. A SpongeBob/Looney Tunes crossover will break everyone’s brains though, and I mean that in bad and good ways.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Programming note: MGM100

Having already missed out on Columbia Pictures' 100th anniversary this last January, I wasn't about to ignore yet another - and arguably more historically important - anniversary upcoming.

The upcoming marathon will be tagged MGM100 and will appear Tuesdays and Wednesdays this month (beginning later this evening). Featured films will be posted/queued in roughly chronological order.

This April marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), the result of a merger between three silent film-era production companies in Metro Pictures, Goldwyn Pictures, and Louis B. Mayer Pictures. Within a decade, MGM became one of the major Hollywood studios*, boasting that it had contracted "more stars than there are in heaven".

By the end of the 1930s, it was undoubtedly the biggest, most stable, financially successful, and most powerful of all of those studios. Some of the most lavish productions in film history were shot on its Culver City lot (which is now Sony Pictures Studios for Columbia's use, as well used by the American versions of Jeopardy! and Wheel of Fortune) and MGM's reputation for being the home of the greatest Hollywood movie musicals (1939's The Wizard of Oz, 1952's Singin' in the Rain) was unrivaled. Not until the Walt Disney Studios of the 2010s would Hollywood ever see a studio so dominant in the industry.

The good times did not last. Following the spectacular Ben-Hur (1959), MGM embarked upon a misguided financial strategy of releasing one big-budget epic film ever year and releasing fewer movies per year. Upon Kirk Kerkorian's purchase of MGM in 1969, Kerkorian decided to slowly convert MGM into a real estate and hotel and casino company and approved of the near-complete disposal of the studio's music library - thrown into a landfill now underneath a golf course.

MGM ceased being a major studio in 1986 upon Ted Turner's purchase of the studio and decision to almost immediately resell the studio back to Kerkorian (Turner, crucially, kept the rights to the pre-May 1987 MGM library, which formed the original basis of Turner Classic Movies, TCM). Multiple financial crises since 1986 (including a 2010 bankruptcy) have seen MGM fall even further from its once-lofty perch. Amazon purchased MGM (including the less cinematically interesting post-May 1987 library, although this includes the rights to the Rocky and James Bond series) in October 2023; only time will tell what Amazon plans to do with the studio.

***

So please join me this month as my blog features a celebration for a century of MGM. From epics such as Ben-Hur (1925 original and 1959 remake) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); romances such as Waterloo Bridge (1940) and Three Thousand Years of Longing (2022); comedies such as The Thin Man (1934) and American Fiction (2023); animation such as the Tom and Jerry series and The Secret of NIMH (1982); and musicals such as Meet Me in St. Louis (1944) and Victor/Victoria (1982), MGM's history is among the richest of any studio out there. I certainly hope you enjoy the marathon coming to your dashboards soon!

* MGM was considered a major studio alongside Paramount, RKO, 20th Century Fox, and Warner Bros.; Columbia, United Artists, and Universal were considered the "Little Three"; Disney would not be a major studio until the 1990s.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writers Guild West Official: Era of Hollywood Mergers Hastened the Strike

August 10, 2023

Laura Blum-Smith, the Writers Guild of America West’s director of research and public policy, considers the strike a result of a tsunami of Hollywood mergers that has handed studios and streamers the power to its exploit workers.

“Harmful mergers and attempts to monopolize markets are a recurring theme in the history of media and entertainment, and they are a key part of what led 11,500 writers to go on strike more than 100 days ago against their employers,” Blum-Smith said on Thursday at an event with the Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice over new merger guidelines unveiled in July.

She pointed to Disney, Amazon and Netflix as companies that “gained power through anticompetitive consolidation and vertical integration,” allowing them to impose “more and more precarious working conditions, increasingly short term employment and lower pay for writers and other workers across the industry.” But she sees revisions to the merger guidelines that address labor concerns a key part of the solution to prevent further mergers in the entertainment industry moving forward.

“The FTC and DOJ’s new draft merger guidelines are part of a deeply necessary effort to revive antitrust enforcement,” she added. “Compared with earlier guidelines, the new ones are much more skeptical of the idea that mergers are the natural way for companies to grow. And they focus more on the various ways mergers hurt competition, including how mergers impact workers.”

In July, the FTC and DOJ jointly released a new road map for regulatory review of mergers. They require companies to consider the impact of proposed transactions on labor, signaling that the agencies intend to review whether mergers could negatively impact wages and working conditions. FTC commissioner Alvaro Bedoya, who was joined by agency chair Lina Khan, said in a statement about the guidelines that “a merger that may substantially lessen competition for workers will not be immunized by a prediction that predicted savings from a merger will be passed on to consumers.” Historically, transactions have been considered mostly through the lens of benefits to consumers.

The guidelines lack the force of law but influence the way in which judges consider lawsuits to block proposed transactions. They also tell the public how competition enforcers will assess the potential for a merger’s harm to competition.

Antitrust enforcers have steadily been taking notice of negative impacts to labor as a result of industry consolidation. “We’ve heard concerns that a handful of companies may now again be controlling the bulk of the entertainment supply chain from content creation to distribution,” Khan said last year during a listening forum over revisions to the guidelines, in a nod to anticompetitive conduct by studios that led to the Paramount Decrees. “We’ve heard concerns that this type of consolidation and integration can enable firms to exert market power over creators and workers alike.”

Adam Conover, writer and WGA board member, said in that April 2022 forum that his show Adam Ruins Everything was killed by AT&T’s acquisition of Time Warner in 2018 when TruTV’s parent company forced the network to cut costs. He stressed that a handful of companies “now control the production and distribution of almost all entertainment content available to the American public,” allowing them to “more easily hold down our wages and set onerous terms for our employment.” It’s not just writers that are impacted by an overly consolidated Hollywood either, he explained. After Disney acquired 21st Century Fox in 2019, he said that the studios pushed the industry into ending backend participation and trapping actors in exclusive contracts preventing them from pursuing other work.

Blum-Smith said that aggressive competition enforcement is necessary as “Wall Street continues to push for more consolidation among our employers despite the industry’s history of mergers that failed to deliver any of the consumer benefits they’ve claimed that left writers and audiences worse off with less diversity of content and fewer choices.”

“More mergers will leave writers with even fewer places to sell their work and tell their stories and the remaining companies will have even more power to lower pay and worsen working conditions,” she warned. “Strong enforcement against mergers is essential to protect workers in media and workers across the country and these guidelines are an important step in the right direction.”

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

How has the MCU impacted Wanda in the comics?

Well, there are a few different things which typically happen when a character debuts in the M C U, or they have a new movie come out.

One is market synergy. Comic book characters often get more exposure or visibility when their MCU counterpart is having a big moment. That's definitely happened to Wanda-- between AXIS and her solo series, Wanda was very busy the year that Age of Ultron came out, and her current era, starting with Trial and Darkhold, kicked off around the same time as Wanda//Vision.

The other thing that happens sometimes is that the comic character will get a makeover, or bring back an older costume, to look more like their movie counterpart. Some characters, especially the more obscure ones, will be changed pretty radically to bring them more in line with the version films audiences know-- Peggy Carter is one of the earliest examples. Fortunately, this hasn't ever happened to Wanda. I don't think she's anything like the MCU version-- her costumes, powers, and personality were very different in the 2016 Scarlet Witch, and right now she's going through a major renaissance where she's actually being represented as a woman of color.

But the biggest impact was obviously the AXIS retcon. It's, like, 99% confirmed that the retcon only happened because of an IP dispute between Marvel Studios and Fox, who, at the time, held separate film rights for X-Men and all mutant characters. This was before the Fox/Disney merger, of course. Marvel changed Wanda and Pietro's backstory so they could continue using them in the MCU, and it had a major, lasting impact. Some of the things which have come from this change actually good, but a some of them are bad, and it really messes with continuity.

13 notes

·

View notes