#kyrgyz art

Text

ooeeoo

#hatsune miku#miku hatsune#vocaloid#vocaloid fanart#my art#THE LITTLE MIKU IS KYRGYZ MIKU#since her birthday is on kyrgyzstan independence day

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Otoyomegatari

#turkic#turkish#traditional#türk#nomad#artwork#art#anime and manga#manga#otoyomegatari#turkmen#turkic culture#kazakh#kyrgyz#azerbaijani#chuvash#gagauz#uzbek#bashkir#girl

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyrgyz girl

#asian#artist#my art#artists on tumblr#art#girl#green#dia schleife#drawing#behance#asian girl#plant#kyrgyz girl#kyrgyzstan#illustration#sketch#sketches#sketching#dianabow#digital art#digital illustration#aesthetic

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

kyrgyzstan

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyrgyz girl

A drawing of a kyrgyz girl in traditional kyrgyz outfit.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

i noticed that your banner is art of a (kazakh or kyrgyz?) falconer with a golden eagle. do you have a interest in falconry or have you ever practiced it?

Yes! I love cultures from various countries around the world, but among them, I have a special appreciation for Mongolian and Central Asian cultures. The traditional falconry culture of the Kazakh people, using majestic Golden Eagles, has left a profound impact on me. I'm truly fascinated by them.

Although I haven't had the opportunity yet, it's my dream to one day visit and experience the nomadic life of Mongolia and learn from the Kazakh falconers.

By the way, the ethnic groups featured in my creations are fictional and are a blend of various real-world cultures, incorporating elements that don't actually exist. So, please keep that in mind.

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

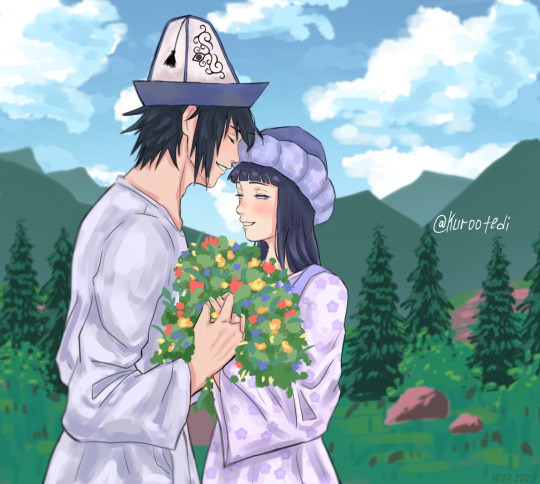

Day 14:

“Bouquets”, “Enjoying a story together”

Belatedly drew art for #sasuhinamonth2023 and on the 14th day I chose two topics at the same time~

I decided to dress them in Kyrgyz national costumes 🤗 This is my homeland (‾◡◝)

💜💜💜💜💜💜💜💜💜💜💜💜

Brief description of the plot:

Sasuke and Itachi are the sons of the head of the Uruu (Uruu is something like a clan or tribe) "Uchiha". Fugaku, the head of the Uchiha, decided to marry his sons to the daughters of other uruu, and as you already understood, the eldest daughter Hyuga was chosen for Sasuke. He did not want to marry, like Hinata, but they did not have the right to vote and they had no choice but to silently accept.

A lot of things will happen, both good and bad, they will begin to experience love feelings for each other, but this will not happen immediately, but gradually)

16.07.2023

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Boris Nikolaevich Bezikovich (1917 - 1978).

Winter forest. 1948.

Oil on cardboard. 15.5x19.5 cm.

Boris Nikolaevich Bezikovich (1917-1978) - painter. In 1934-1939 he studied at the Moscow State Academy of AshU in memory of 1905. In 1941-1944 and in 1958-1962 he taught at the Kyrgyz Art School. Since 1940 - participant of exhibitions of works by young Moscow artists, MOIF of the USSR, etc. Personal exhibitions were held in Frunze (1959), Stupino (1962), Moscow (1966). Member of the USSR Union of Artists. The works are stored in the Tver KG, the Kyrgyz Museum of Fine Arts, KhM Pereslavl-Zalessky, etc.

Alters

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russian Colonialism in Central Asia 1860-1890

From 1860 to 1890, Russia conquered Central Asia. What started as crafting a strong border along their Siberian territories grew into the conquest of most of modern day Central Asia.

Russia and Central Asia have a long, intertwined history that altered between coexistence and conflict. The Russians didn’t start expanding eastwards until the 1500s and they didn’t ’t really consider invading the region until the 1700s and even then, it’s contained to the Steppe lands. We don’t really see engagements with major Central Asian powers until the late 1700s/early 1800s. Their approach isn’t systematic or well planned. The Russians are responding to events unfolding, both in the region and from the around the world, as much as they are trying to shape events to fit their own priorities. They don’t fully subdue the region until the 1880s and roughly 30 years later WWI begins. By 1917 the Tsarist Empire collapses, and Russia loses all control over their conquered territories, including Central Asia. It would be up to the Bolsheviks and the various Central Asian republics to determine what relations would look like during the rest of the 20th century.

Early Russian Incursions (1580s-1700s)

As we mentioned, Russia and the various peoples of Central Asia traded and interacted with each other for most of their early history. The Russians did not consider expanding eastwards until the 1500s, starting with the overthrow of the Kazan khanate in 1552 and Astrakhan khanate in 1556 (two main centers of trade for people from all over the world). In 1580, they overthrew the Khanate of Sibr, opening up Siberia and introducing Kazakh peoples to Cossacks and Slavic merchants, and officials.

Peter the Great

[Image Description: A colored painting of a white man with curly brown hair and a mustache leaning against a chair. Behind him is a grey sky. The man is wearing a dark blue military frock coat with a light blue ribbon and a golden and green metal at his thought. His collar and cuffs are a bright red. He holds a sword with his right hand and a map with his left.]

Up until Peter the Great’s reign in 1682, the Russians and Central Asians spent their time learning about each other and establishing centers of trade. Neither saw each other as a source of danger since the Central Asians khanates were more concerned about fighting each other and resisting pressures from Safavid Iran and China whereas Russia was establishing itself as a state.

It was Peter the Great who turned Russia into an empire and pushed into the Central Asia region, sparking conflict with the Bashirs, Astrakhans, Khiva Khanate, and even Iran. Peter ordered several forts to be built along the current Kazakhstan border and took the Volga and Ural lands, encircling Central Asia. Their first proper incursion into the region was within Steppe lands. The Russians tried to implement tribute and oaths of loyalty, but the Kazakh people either resisted or manipulated Russian demands to fit their needs. They often played the Russians against their other enemies such as China, the Zunghar people, and the different Uzbek Khanates. However, the more involved they became with the Russians, the more restricted their political freedom became and by 1730 they officially asked the Russians for their protection.

Kazakhs and Kyrgyz peoples 1700s-1800s

The first Tsarina to truly interact with her Muslim subjects was Catherine the Great. She chose a position of tolerance while enforcing methods of police control. Catherine believed that if she could use the Islamic hierarchy to manage the people, she could instill law and order in the region. As long as she controlled who was recognized by the state as a legitimate source of religious authority, she could control the people and bind Islamic ideals to the Tsarist system. She implemented this policy with the Muslims in Siberia, the Volga and Ural regions, and the Crimea, utilizing the indigenous Tatars. When Russia tried to implement this system with the Kazakhs they ran into issues.

Catherine the Great

[Image Description: A colored painting of a white, big woman with grey hair pinned up and held in place by a golden crown. She is wearing a tan furred dress and a silver necklace with ornaments in the shape of snowflakes.]

Lack of knowledge is a key component in the Russian rule, and they were aware of this. As they incorporated the land, they sent several expeditions into the region to understand the territory, the people, and the benefits they could reap from the area. Ian W Campbell’s book Knowledge and Ends of Empire goes into great detail how much the Russians didn’t know as they conquered the Steppe lands and the efforts, they went through to fill in their knowledge gap.

Since the Kazakhs were nomads, they did not practice a type of Islam recognized by the Russians, so they were unable to utilize any existing religious structure, like they did with the Tatars. Instead, they had to engage with the different tribal leaders and indigenous informers and spies to manage the steppe peoples and enforce a form of sedentary lifestyle (with mixed results).

In an effort to “bring civilization” to the Kazakh people the Russians abolished the hordes and reorganized the land along tribal lines into three regions. They implemented a heavy bureaucracy consisting of auls, townships, and districts. In 1844, the Kazakhs traditional courts were stripped of authority over serious criminal cases and subjected Kazakhs to Russian military courts.

Authority was maintained by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and military governors, which tried their best to manage the theft and abuse the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz peoples experienced from Russians officials and the Cossacks. This abuse seems to have been driven by the lawlessness common to vast frontiers (one can think of the US’s own Wild West as an example) and because most Russians looked down on the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz as inferior people.

Uzbek Khanates 1800-1900

Driven by mistreatment, starvation, and fear of the Russians, many Kazakh peoples found shelter in the Uzbek khanates. By the 1800s, all three khanates were experiencing civil wars and intense rivalries with each other and either ignored or were disinterested in the Russian encroachment. They were vaguely curious about the increase of British visitors but didn’t seem to realize that it meant trouble for their people. To be fair, the British were notoriously bad at trying to enlist the aid of the khanates as can be seen with the Conolloy-Stoddart-Nasrullah affair.

Nasrullah, Khan of Bukhara

[Image Description: An ink drawing of a man in a turban and long, wispy black beards. He also had a drooping black mustache and a white long dress shirt. The paper the painting is drawn on is tan and below the man are words written in Arabic]

Charles Stoddart was sent to Bukhara by the East India Company to win over the emirate, Nasrullah. Instead Nasrullah found him so insulting, he threw him into a bug pit for a few days. Stoddart remained in Bukhara for three years before the Company sent Captain Arthur Connolly to rescue him. Connolly traveled disguised as a merchant, but the Emirate was on alert since Britain was invading Afghanistan at the same time. Around the time Connolly was arrested, the Afghans organized a revolt that drove the British out of their country (only one British survivor made it back to India). Nasrullah wasn’t impressed and felt even more insulted by Connolly’s and Stoddart’s behavior, so he beheaded them when he caught them trying to smuggle letters to India.

Modern historians have poked several holes into the Great Game narrative, and it may be safe to say that the Great Game is more of a reflection of Britain’s own insecurities and fears than reality (with the Russians taking advantage of said fears). At the same time, Russia was feeling insecure compared to the other European states, had a need to make up for the humiliating defeat suffered during the Crimean War, were concerned about the security of their southern frontier, and held racist beliefs about the inferiority of the Central Asian peoples.

Their first attempt was to invade Khiva in 1839, but that ended in disaster. They would not try again until 1858, pushing southward, along the Syr Darya. By 1860 they had taken and established forts in what is modern day Almaty, Kazakhstan and Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. In 1864 Colonel Mikhail G. Cherniaev finished the conquest of the land along the Syr Darya by taking the towns of Yasi and Shymkent. In 1865, he took Tashkent from Kokand, conquering the last bit of Kazakh land.

At this point, we can organize the Russian conquest around three major events: the subjugation of the Bukhara and Khiva Khanates, the abolishment of the Kokand Khanate, and the slaughter of the Turkmen people in the Ferghana valley

Conquering the Bukharan Khanate

However, conquering Tashkent dragged them into the rivalry between Kokand and Bukhara. The Russians wanted to turn Tashkent into a buffer state between themselves and Bukhara while Bukhara hoped the Russians would return the city to them. When Emir Muzzafar sent an envoy to embassy to the Tsar, he was arrested and Muzzafar was told he no longer had the right to speak to the Tsar directly. Muzzafar was stunned and furious so he arrested a Russian diplomat sent from Tashkent. The Russians attacked the Bukharan town of Jizza but returned from lack of supplies. The Bukharans responded by marching on Tashkent but were defeated by the Russians at Irjar. The Russians then took Khujand, cutting off communications between Bukhara and Kokand, preventing a coordinated resistance.

Konstantin Petrovich Von Kaufmann

[Image Description: A black and white lithograph of a white man with a receding hairline. He has a grey bushy mustache. He wears a grey military tunic with epaulettes and several medals. His hands rest on his shoulder hilt.]

To neutralized Kokand, further the Russians a treaty with Kokand granting Russian merchants free trade rights in the khanate and vice versa in Russian Turkestan. However, since Russia’s economy was bigger, this made Kokand an economic vassal.

Bukhara tried to resist the Russians but because of a divided military, internal rebellions, and antiquated technology, Muzzafar was forced to surrender in June 1868. The treaty restored Muzzafar’s sovereignty but took Samarkand away, controlling Bukhara’s main water source. Russian merchants were allowed to conduct business in Bukhara with the same rights as local merchants and Bukhara had to pay a compensation for Russia’s expenses during the war.

While the conquest of the Syr Darya basin and Tashkent had been approved by ministers in St. Petersburg, the Bukharan conflict was decided by officers on the ground. They actually recalled Cherniaev in 1866 only for his replacement, Romanovskii to attack Khujand. In 1867, Romanovskii was replaced by Konstantin Petrovich Von Kaufmann (who was a bit of an asshole) who served as Turkestan’s first governor-general. Despite the fact that its military had gone rogue, the Russians could not tolerate retreating or returning the land. Think about how it would affect its standing amongst the European powers (sarcasm)

Kaufman called his conquered territory Turkestan and made Tashkent as its capital. Given its distant from St. Petersburg, Kaufman enjoyed remarkable independence and was more like an emperor than a civil servant.

Conquering the Khivan Khanate

By 1859, Russia had conquered the North Caucasus and created a port in modern day Turkmenboshi, Turkmenistan. This allowed the Russians to transport goods via the river, instead of making the long and dangerous journey from Khiva to Orenburg. This deeply hurt Khiva’s income and cut into the incomes of the Turkmen who protected or raided the traveling merchants.

That, combined with the Russian conquest of Kokand and Bukhara and Khiva was in serious trouble. Khivan Emir Muhammad Rahim, learned from Bukhara, released all Russian prisoners, and negotiated with Russia for peace. Kaufman, however, wasn’t interested in peace. Instead, he sent message after message to Alexander II to complain about Khiva’s insolence and the danger it posed to Russian merchants, finally getting his permission to launch a military campaign to punish Khiva. In 1872, Kaufman led an invasion of four columns, consisting of over 12,000 men and tens of thousands of camels and horses and attacked Khiva from three directions. The Khivans did not resist vigorously whereas the Turkmen fought viciously.

On June 14th, Muhammad Rahim surrendered and Kaufmen forced him to govern under a Russian led council while he ransacked the palace for personal prizes. On August 12th, 1873, Rahim signed a stricter treaty then the one Muzzafar signed. The treaty forced the khan to acknowledge he was an obedient servant of the Tsar, granted control of navigation over the river Amu Darya to the Russians, and granted extensive privileges to Russian merchants. They also agreed to pay Russian 2.2 million rubles over the course of twenty years.

The Turkmen

While Khiva was subdued, the Turkmen were as rebellious as ever and Kaufman jumped at the opportunity to expand his power and earn more “glory”. In July 1873, he required that the Turkmen pay 600,000 rubles with only two weeks to deliver, knowing it would be impossible to do. When they failed, Kaufman launched an attack on the Yomut, a Turkmen tribe. American journalist Januarius MacGahan reported the following:

This is war such as I had never before seen, and such as is rarely seen in modern days…I follow down to the marsh, passing two or three dead bodies on the way. In the marsh are twenty or thirty women and children, up to their necks in water, trying to hide among the weeds and grass, begging for their lives, and screaming in the most pitiful manner. The Cossacks have already passed, paying no attention to them. One villainous-looking brute, however, had dropped out of the ranks and leveling his piece as he sat on his horse, deliberately took aim at the screaming group, and before I could stop him, pulled the trigger. Fortunately, the gun missed fire, and before he could renew the cap, I rode up and cutting him across the face with my riding-whip, ordered him to his sotnia. - Januarius MacGahan

By end of July, the Turkmen agreed to pay and Kaufman extended the deadline.

Even though Russian conquered Kokand, they had a hard time implementing political control, having to deal with a still strong khanate and an angry populace. The death of the old khan, Alim Qul, allowed Khudoyar Khan to return to rule. However, his close ties with Russia inspired a revolt amongst the Kokandi Kyrgyz nobles who drove him out in August 1875. The Russians placed his son, Nasruddin on the throne, but another revolt drove him out as well and Russia was stuck with a region deep in civil war with no clear factions.

Kaufman, worried that Bukhara or the British would take advantage, launched another military campaign. This campaign was particularly bloody, with Major-General Mikhail D. Skobelev making it a point of murdering civilians to crush all future rebellions. Vladimir P. Nalivkin, a young officer serving under Skobelev wrote the following of an incident where Skobelev ordered his Cossacks to charge fleeing civilians while their divisional commander countermanded the order. He then told Nalivkin to chase after a Cossack bearing down on an unarmed man carrying his child. Nalivkin wrote the following:

“With a cry “leave him alone! Leave him alone!” I rushed towards the man (sart), but it was already too late: one of the Cossacks brought down his sword, and the unfortunate two or three-year-old child fell from the arms of the dumbfounded, panic-striken man, landing on the ground with a deeply cleft head. The man’s arms were apparently cut. The bloody child convulsed and died. The man blankly stared now at me, now at the child, with wildly darting, wide eyes. God forbid that anyone else should have to live through the horror I lived through in that moment. I felt as though insects were crawling up my spine and cheeks, something gripped me by the throat, and I could neither speak nor breathe. I had seen dead and wounded people many times; I had seen death before, but such horror, such abomination, such infamy I had never been seen with my own eye: this was new to me.” - Vladimir P. Nalivkin

The war ended in 1876 with the bombing of Andijan, which Skobelev described himself as a pogram. Kaufman abolished the Kokand Khanate on February 19th, the same day as the anniversary of Alexander II’s ascension to the throne. He renamed the region the Ferghana District and named Skobelev its governor.

Finally, the Russians finished their conquest by subjugating the Turkmen Tekke tribes who lived around the oases in the Qara Qum desert. The reason for the attack was geopolitical. The Russians had won a war against the Ottoman Empire in 1878 but the British prevented the Russians from seizing Constantinople, so Kaufman was ordered to march on India.

Kaufman sent three columns towards Afghanistan and Kashmir and a fourth column heading towards the town on Kelif on the Amu Darya. To get there, they had to march through Tekke Turkmen territory. The attack was called off a week later, but the Russians continued south to establish a line of forts on the border of Iranian Khurasan. These forts were vulnerable to Turkmen attack, so the Russians laid siege to the town of Gok Tepe.

Their artillery was devastating but the Russians were defeated by fierce Turkmen fighting when they decided to storm the town. Skobelev led a revenge campaign in November 1880, finally blowing up the walls of Gok Tepe in January 1881. He ordered the Cossacks to pursue and kill anyone fleeing. The total cost was 14,500 Turkmen killed, including many non-combatants, destroying the Tekke Turkmen for decades and finalizing Russian control over Central Asia.

References

For Prophet and Tsar: Islam and Empire in Russia and Central Asia by Robert D. Crews Published by Harvard University Press, 2006

The Rise and Fall of Khoqand: Central Asia in the Global Age 1709-1876 by Scott C. Levi Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017

The Bukharan Crisis: a Connected History of 18th Century Central Asia by Scott C. Levi Published by University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020

Tatar Empire: Kazan’s Muslims and the Making of Imperial Russia by Danielle Ross Published by Indiana University Press, 2020

Russia and Central Asia: Coexistence, Conquest, Coexistence by Shoshana Keller Published by University of Toronto Press, 2019

Russia’s Protectorates in Central Asia: Bukhara and Khiva, 1865-1924 by Seymour Becker, Published by RoutledgeCurzon, 2004

Tournament of Shadows: the Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia by Karl E. Meyer and Shareen Blair Brysac Published by Basic Books, 1999

#Season 2: Central Asia#Central Asia#Central Asian History#Russian Colonialism#Podcast Episode#Blog Post#history blog#queer historian#queer podcaster#Spotify

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

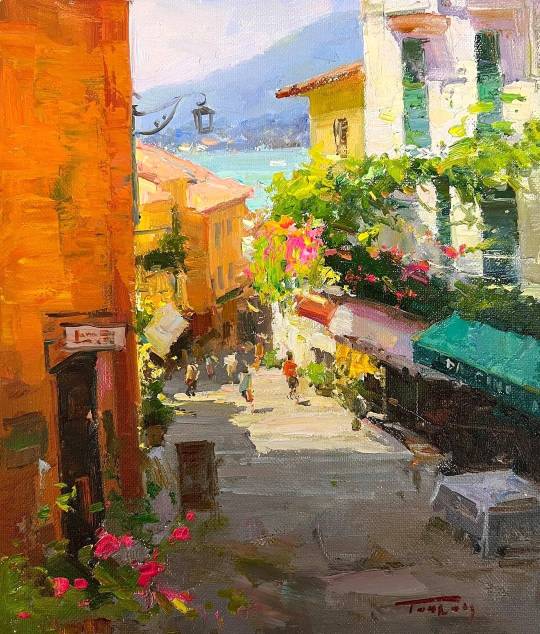

Wonderful Kyrgyz impressionist artist Taalaibek Musurmankulov. I have published his paintings several times. He was born in Kyrgyzstan in 1985, graduated from the National Academy of Arts of Kyrgyzstan, faculty of easel painting. In general, this Academy has grown a whole galaxy of modern impressionists, who are very successful with the public.

Since 2009, Taalaibek Musurmankulov lives and works in St. Petersburg, is a member of Russian and Kyrgyz creative unions. I also really like his St. Petersburg landscapes.

"Beautiful day" is the name of the painting. I think, I'm not mistaken, this is the Italian Bellagio - the famous descent to Lake Como. In general, there are many sightseeing places in Bellagio, but tourists from all over the world like this most of all. We lived closer to Villa Serbelloni, so we went up Via Roma.

#impressionism #impressionismo #impressionisme #impressionismart #impressionismpainting #painting

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

: . fountain with surrounded space occupied by a private cafe behind museum complex . Gapar Aitiev Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts, designed by architects: S. Dschekshenbajev, V. Nazarov, A. Jussupov, D.Yryskulov, built in 1974. . . #doc_film_inprogress #studycase_fineartsmuseum #transformationofpublicspace #publicspaces_bishkek #publicspace #urbanism_bishkek #socialistarchitecture_kyrgyzstan #kyrgyzmodernism #modernismtour_kyrgyzstan #socialistarchitecture #sovmod #sovietmodernism #modernismtour #bishkek #frunza #socialistkyrgyzstan . ©stefanrusu . (at Frunze, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bo3aY8vB_U6/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#doc_film_inprogress#studycase_fineartsmuseum#transformationofpublicspace#publicspaces_bishkek#publicspace#urbanism_bishkek#socialistarchitecture_kyrgyzstan#kyrgyzmodernism#modernismtour_kyrgyzstan#socialistarchitecture#sovmod#sovietmodernism#modernismtour#bishkek#frunza#socialistkyrgyzstan

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything about Turkic ✨

My Twitter acc https://x.com/TURK1CCULTURE?t=7REqXlqRla9r1OpaHbp-yw&s=09

My Pinterest acc

#turkic#turkish#turkiye#türkiye#traditional#türk#art#nomad#artwork#ottoman#kazakh culture#kazakh#kazakhstan#azerbaijani#azerbaycan#azerbaijan#kyrgyzstan#kyrgyz#chuvash#gagauz#sakha#yakutsk#uzbek#uzbekistan#turkmen#turkmenistan#yurt#yörük#wolf#bashkir

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meduza's The Beet: More than a name

This week, journalist Katie Marie Davies returns with the story of how one activist’s quest to change her children’s names challenged deeply rooted social and cultural norms in Kyrgyzstan and beyond.

More than a name

Why the battle for matronymics in Kyrgyzstan matters

By Katie Marie Davies

In December 2020, art curator and activist Altyn Kapalova embarked on a personal crusade under an unforgiving public eye.

It began with an attempt to give her children a matronymic: a second or middle name derived from her own given name. In Kyrgyzstan, where children traditionally receive only patronymics — a name derived from their father’s first name — the idea sparked fierce social debate, including condemnation from religious and political leaders.

For Kapalova, the creation of a matronymic was a long-held ideal. Her children’s biological fathers were stripped of their parental rights in a lawsuit in 2020. But long before then, mother and children had often discussed changing their names so that they shared a single surname.

“We didn’t just talk about it— we dreamed about it,” Kapavola told The Beet. “And when we talked about [changing our surname], the idea came up of having a matronymic to match. It was just logical.”

In reality, the process was far from straightforward.

When Kapalova first visited the registration office in Bishkek, she managed to change her children’s names without any significant problems. But when officials realized what she had done, they filed a lawsuit against her, which resulted in a Bishkek court reinstating the children’s patronymics. Undeterred, Kapalova filed an appeal.

The case made it all the way to Kyrgyzstan’s Supreme Court, which upheld the original ruling in April 2022. Then, unexpectedly, a final order from the Constitutional Court in June 2023 gave Kapalova a partial victory. It decreed that citizens would be allowed to adopt matronymics, but only at the age of 18 — a move that the court argued would mitigate “various kinds of stigma and bullying” that might occur in traditional Kyrgyzstani society.

“Despite everything, I consider this a win. Women still can’t give their own name to their children at birth, but adult children can take their mother’s name,” Kapalova wrote in a statement after the verdict. “I believe the country has taken a huge step towards justice and gender equality.”

The reaction to the case has been mixed and passionate, consisting of largely positive real-world interactions and a torrent of hate online, says Kapalova. “Women have stopped me on the street; they’ve sent me gifts as a sign of their support; and strangers have hugged me and thanked me,” she recalls.

Critics, meanwhile, have accused Kapalova of opening her children to ridicule and undermining the country’s long-held values. Kyrgyzstan’s most senior Islamic cleric, Zamir Rakiev, argued that matronymics would rob children of the chance to know their ancestors, claiming that “such dangerous initiatives destroy the roots of the nation.” The head of Kyrgyzstan’s State Committee for National Security, Kamchybek Tashiev, called for the annullment of the court’s decision. “Knowing your ancestry means preserving your genetics and origins,” he told RFE/RL’s Kyrgyz Service. “To know the names of your ancestors, we need to preserve your father’s surname.”

But Kapalova argues that the ruling is about something more important: the right for families to choose what’s truly best for them. Even when she lost her initial court cases, Kapalova did not doubt the importance of what she was doing, she says.

On a broader scale, the case and its fervent discussion have captured a nation in flux. Like other countries across Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan is grappling with its own identity and re-examining the legacy of Soviet imperialism by re-embracing old traditions and charting new paths.

In this context, Kapalova’s case challenges norms that have long been taken for granted — pushing the boundaries of how Kyrgyz society remembers its roots and the forms that families can take.

Language and legacy

Patronymic names have deep roots in Kyrgyzstan and across Central Asia. Ancestral and clan ties play an important role in Kyrgyz society; traditionally, Kyrgyz people are expected to be able to recite the names of their ancestors along their father’s line going back at least seven generations.

Before the Soviet Union’s forced settlement and collectivization program in the 1930s, most Kyrgyz families lived nomadic lifestyles, so lineage, rather than place, was key in determining a person’s identity. Traditionally, Kyrgyz children would take their father’s name as their surname and the patronymic particle “kyzy” for daughters or “uulu” for sons.

But these are not the patronymic names that Kapalova hoped to challenge. Her battle focused on the Russian-style patronymics introduced in Central Asia as the region came under imperial Russian, and then Soviet, control.

Russian patronymics consist of a father’s given name and a gendered suffix and are usually given to children in addition to their first name and family name. For example, if a man has the name Aleksander, then his sons would take the patronymic “Aleksandrovich,” and his daughters would take “Aleksandrovna.” In Kapalova’s case, she hoped to use her first name, Altyn, to give her sons the matronymic “Altynovich” and her daughter “Altynova.”

Introducing these patronymics in Kyrgyzstan coincided with a larger campaign of Russification during the Soviet period. Kyrgyz citizens were pressured to add Russian-style endings to their surnames or adopt new Russian first names. Doing so often made it significantly easier to secure well-paid jobs or avoid uncomfortable questions about political loyalty at school or university. For other families, changing their names was necessary to protect themselves from persecution, as relatives were ostracized for their ties to individuals whom officials deemed “enemies of the people.” At the same time, the Soviet authorities worked hard to discourage traditional clan or kinship ties, viewing them as a threat to Moscow’s authority.

Following the Soviet Union’s collapse, these changes were slowly undone, with many people across Central Asia reclaiming their traditional names over the past three decades.

Diana T. Kudaibergen, a Kazakh political and cultural sociologist based at the University of Cambridge, was previously known by the last name “Kudaibergenova.” She decided to remove the Russian-style suffix from her name just recently.

“It made me feel uncomfortable. I moved abroad when I was barely 21, and it felt like people read my name and immediately expected to see some blue-eyed, blonde-haired Russian lady. I don’t mind it, but the Russification of my name rarely gave me a chance to be someone non-Russian,” she told The Beet.

Kudaibergen says that she had wanted to remove the Russian ending from her name since she was a teenager, but Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine had made questions of identity and Russian imperialism even more pressing. It’s a feeling shared by many across Central Asia today.

“Personally, I didn’t want to speak Russian [after the 2022 invasion]; I didn’t want to listen to anything Russian, and I didn’t want to sound Russian. I’m still processing it — because I know that the Russian I speak is something else, but it still makes me uncomfortable,” she says. “And those three letters were there on your passport defining you, defining your legacy, and your present and future in a very unfortunate way.”

Fighting within the system

Against this backdrop, it may seem surprising that the creation of a matronymic name has met so much resistance. Many believe that it’s the feminist nature behind the idea that has made it so controversial. “In my view, people — including these politicians and public figures — are defending not their patronymics, but their patriarchal values,” says Kapalova.

It’s precisely this gendered backlash that has made Kapalova’s victory so meaningful. Previously, mothers in Kyrgyzstan could simply choose not to give their child a patronymic at all. But the legal existence of a matronymic isn’t just about signaling the absence of a father figure from a person’s life; it’s about celebrating mothers’ contributions and officially recognizing them in the public sphere.

Erica Marat, a professor at the National Defense University in the United States, is one of the many Kyrgyz women who say that Kapalova’s victory has held real resonance for them.

“For me, the greatest significance of this victory is that it emphasizes the reality that a lot of women face: being forced to raise kids on their own because the fathers are absent. It’s about reclaiming what is considered ‘normal’ by society,” she told The Beet. “In a way, she’s reclaiming the empty part of her kids’ names.”

This emphasis on making women’s contributions more visible in everyday language has been a particularly pressing topic for Russian-speaking activists in recent years. The most obvious change, particularly in Russia and Belarus, has been a new emphasis on using “feminitives”: the gendered title for jobs or roles, such as “poetess” or “directoress.”

But while the legacy of Soviet imperialism means that many people in Kyrgyzstan — predominantly in urban areas — do speak Russian as a second or first language, that doesn’t mean that these models could (or should) work in Central Asia. Most Turkic languages, such as Kyrgyz and Kazakh for example, don’t use gender markers for such words at all.

Rethinking ideas such as how lineage is celebrated could open the door for women and their contributions to be honored more publicly — and in a way that is more meaningful and authentic in Kyrgyzstan and across Central Asia.

For now, that may include putting a feminist twist on imperial relics, such as Russian naming conventions.

Kapalova hopes that Kyrgyzstani society will one day abandon Russian naming customs altogether. But she also acknowledges that conscious decolonization began only recently and that millions of Kyrgyzstani people still have these names. Her victory is about working with the reality that exists in the country today, Kapalova explains.

“In any civic struggle, there are certain barriers you can’t jump over — you have to go through them,” she says. “I am fighting against the system, but within the current system.”

‘Tradition is what we make it’

Ultimately, each small step also encourages other kinds of change. Kudaibergen is already seeing signs of a shift in Kazakhstan. She remembers leafing through her family’s genealogy books as a child, which only recorded her male relatives. “I used to pencil myself into the book next to my father’s name,” she says. “I used to try and write my name down in history because shezhire [the Kazakh family tree] is so important. I used to try and write [in] my mother’s name, too.”

At the time, these DIY additions weren’t met with great enthusiasm in the community at large, but attitudes have since evolved. The same books where Kudaibergen would pencil her name now include the family’s maternal line. “They wrote out biographies of outstanding women who were musicians or scholars — and in one of those books, there’s now my biography and my photo, saying that I am my father’s child,” Kudaibergen explains.

For societies in Central Asia to keep moving forward, says Marat, court cases such as Kapalova’s in Kyrgyzstan are vital. While the ruling has attracted fiery rhetoric, it has also opened new possibilities. “Of course, there’s always a pushback, but that’s okay,” Marat told The Beet. “These initiatives matter, and they set new milestones in what people think and understand in terms of what is possible.”

The way Kapalova sees it, pushing the boundaries of what is possible is critical; families freed from strict social norms can forge their own paths and identities. “If you can have a patronymic, then why shouldn’t you have a matronymic?” she asks rhetorically. “It’s about the right to choose.”

At the same time, those possibilities include new ways of recovering, celebrating, and honoring one’s heritage. “It is so absolutely important to keep our traditions, especially as much was erased after the Bolshevik Revolution. Families are grappling right now, trying to remember who was there,” Marat says.

“Tradition is what we make out of it and how it serves us today,” she adds. “It might be tradition to take your father’s name — but it should be absolutely okay to use your mother’s name and to make that a tradition as well.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm sure the Heartstopper fans will say this makes me as bad as an anti but as a 40 year old genderqueer Kyrgyz man, stories about American teenagers just tend not to land with me. I know you have to like it or you're a hateful asshole (among non-antis) or a bigot (among antis) but not everyone can relate to every piece of media. It's not bad as art. But it's so far from my lived experiences that I struggle to find it engaging - and that is not a moral failing on my part, that's just life.

--

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some ideas and plans on what to write/draw about my OCs next:

-Turkey headcanon during Ilkhanate era and I have an actual historical paper to back my claim but I feel bad about writing it tbh because it developed into a totally horrific direction so currently its only kept in discord chat (I’m doing this to my little meow meow 💔)

-Continue on that Kazmon fic I’ve been neglecting for a week

-I’ve been vaguely thinking about Mongolia and Kyrgyzstan and I should write hcs on them someday like. They actually are a lot compatible and fun with each/other, 11/10

-More Kyrgyz headcanons hopefully

-Sketch Gokturk and more headcanons

-Sketch new OCs Samarkand and Bukhara

-A vague idea forming in my head of chibi Horde + Vanya + Blue Horde art

-More and more and more Kaz headcanons as he’s actually one of my most elaborate OCs and if I make a hc post out of him it will quickly grow into 100

-More Mongolia brats headcanons

3 notes

·

View notes