#macroeconomics

Text

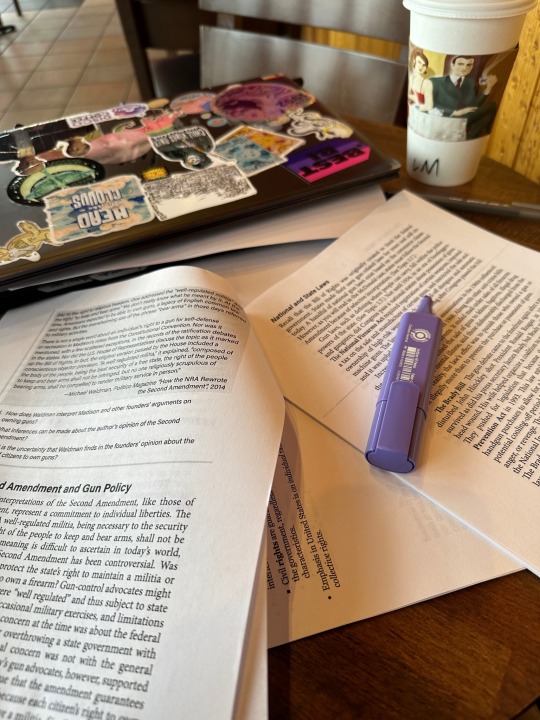

january 22, monday

-> it hasn't stopped raining all week. forced myself to take a lot of government and economics notes.

🎧the metamorphosis, franz kafka

#ap economics#studyblr#studying#aesthetic#studyspo#macroeconomics#mathblr#100 days of productivity#dark academia#study#reading

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why the Fed wants to crush workers

The US Federal Reserve has two imperatives: keeping employment high and inflation low. But when these come into conflict — when unemployment falls to near-zero — the Fed forgets all about full employment and cranks up interest rates to “cool the economy” (that is, “to destroy jobs and increase unemployment”).

An economy “cools down” when workers have less money, which means that the prices offered for goods and services go down, as fewer workers have less money to spend. As with every macroeconomic policy, raising interest rates has “distributional effects,” which is economist-speak for “winners and losers.”

Predicting who wins and who loses when interest rates go up requires that we understand the economic relations between different kinds of rich people, as well as relations between rich people and working people. Writing today for The American Prospect’s superb Great Inflation Myths series, Gerald Epstein and Aaron Medlin break it down:

https://prospect.org/economy/2023-01-19-inflation-federal-reserve-protects-one-percent/

Recall that the Fed has two priorities: full employment and low interest rates. But when it weighs these priorities, it does so through “finance colored” glasses: as an institution, the Fed requires help from banks to carry out its policies, while Fed employees rely on those banks for cushy, high-paid jobs when they rotate out of public service.

Inflation is bad for banks, whose fortunes rise and fall based on the value of the interest payments they collect from debtors. When the value of the dollar declines, lenders lose and borrowers win. Think of it this way: say you borrow $10,000 to buy a car, at a moment when $10k is two months’ wages for the average US worker. Then inflation hits: prices go up, workers demand higher pay to keep pace, and a couple years later, $10k is one month’s wages.

If your wages kept pace with inflation, you’re now getting twice as many dollars as you were when you took out the loan. Don’t get too excited: these dollars buy the same quantity of goods as your pre-inflation salary. However, the share of your income that’s eaten by that monthly car-loan payment has been cut in half. You just got a real-terms 50% discount on your car loan!

Inflation is great news for borrowers, bad news for lenders, and any given financial institution is more likely to be a lender than a borrower. The finance sector is the creditor sector, and the Fed is institutionally and personally loyal to the finance sector. When creditors and debtors have opposing interests, the Fed helps creditors win.

The US is a debtor nation. Not the national debt — federal debt and deficits are just scorekeeping. The US government spends money into existence and taxes it out of existence, every single day. If the USG has a deficit, that means it spent more than than it taxed, which is another way of saying that it left more dollars in the economy this year than it took out of it. If the US runs a “balanced budget,” then every dollar that was created this year was matched by another dollar that was annihilated. If the US runs a “surplus,” then there are fewer dollars left for us to use than there were at the start of the year.

The US debt that matters isn’t the federal debt, it’s the private sector’s debt. Your debt and mine. We are a debtor nation. Half of Americans have less than $400 in the bank.

https://www.fool.com/the-ascent/personal-finance/articles/49-of-americans-couldnt-cover-a-400-emergency-expense-today-up-from-32-in-november/

Most Americans have little to no retirement savings. Decades of wage stagnation has left Americans with less buying power, and the economy has been running on consumer debt for a generation. Meanwhile, working Americans have been burdened with forms of inflation the Fed doesn’t give a shit about, like skyrocketing costs for housing and higher education.

When politicians jawbone about “inflation,” they’re talking about the inflation that matters to creditors. Debtors — the bottom 90% — have been burdened with three decades’ worth of steadily mounting inflation that no one talks about. Yesterday, the Prospect ran Nancy Folbre’s outstanding piece on “care inflation” — the skyrocketing costs of day-care, nursing homes, eldercare, etc:

https://prospect.org/economy/2023-01-18-inflation-unfair-costs-of-care/

As Folbre wrote, these costs are doubly burdensome, because they fall on family members (almost entirely women), who have to sacrifice their own earning potential to care for children, or aging people, or disabled family members. The cost of care has increased every year since 1997:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/18/wages-for-housework/#low-wage-workers-vs-poor-consumers

So while politicians and economists talk about rescuing “savers” from having their nest-eggs whittled away by inflation, these savers represent a minuscule and dwindling proportion of the public. The real beneficiaries of interest rate hikes isn’t savers, it’s lenders.

Full employment is bad for the wealthy. When everyone has a job, wages go up, because bosses can’t threaten workers with “exile to the reserve army of the unemployed.” If workers are afraid of ending up jobless and homeless, then executives seeking to increase their own firms’ profits can shift money from workers to shareholders without their workers quitting (and if the workers do quit, there are plenty more desperate for their jobs).

What’s more, those same executives own huge portfolios of “financialized” assets — that is, they own claims on the interest payments that borrowers in the economy pay to creditors.

The purpose of raising interest rates is to “cool the economy,” a euphemism for increasing unemployment and reducing wages. Fighting inflation helps creditors and hurts debtors. The same people who benefit from increased unemployment also benefit from low inflation.

Thus: “the current Fed policy of rapidly raising interest rates to fight inflation by throwing people out of work serves as a wealth protection device for the top one percent.”

Now, it’s also true that high interest rates tend to tank the stock market, and rich people also own a lot of stock. This is where it’s important to draw distinctions within the capital class: the merely rich do things for a living (and thus care about companies’ productive capacity), while the super-rich own things for a living, and care about debt service.

Epstein and Medlin are economists at UMass Amherst, and they built a model that looks at the distributional outcomes (that is, the winners and losers) from interest rate hikes, using data from 40 years’ worth of Fed rate hikes:

https://peri.umass.edu/images/Medlin_Epstein_PERI_inflation_conf_WP.pdf

They concluded that “The net impact of the Fed’s restrictive monetary policy on the wealth of the top one percent depends on the timing and balance of [lower inflation and higher interest]. It turns out that in recent decades the outcome has, on balance, worked out quite well for the wealthy.”

How well? “Without intervention by the Fed, a 6 percent acceleration of inflation would erode their wealth by around 30 percent in real terms after three years…when the Fed intervenes with an aggressive tightening, the 1%’s wealth only declines about 16 percent after three years. That is a 14 percent net gain in real terms.”

This is why you see a split between the one-percenters and the ten-percenters in whether the Fed should continue to jack interest rates up. For the 1%, inflation hikes produce massive, long term gains. For the 10%, those gains are smaller and take longer to materialize.

Meanwhile, when there is mass unemployment, both groups benefit from lower wages and are happy to keep interest rates at zero, a rate that (in the absence of a wealth tax) creates massive asset bubbles that drive up the value of houses, stocks and other things that rich people own lots more of than everyone else.

This explains a lot about the current enthusiasm for high interest rates, despite high interest rates’ ability to cause inflation, as Joseph Stiglitz and Ira Regmi wrote in their recent Roosevelt Institute paper:

https://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/RI_CausesofandResponsestoTodaysInflation_Report_202212.pdf

The two esteemed economists compared interest rate hikes to medieval bloodletting, where “doctors” did “more of the same when their therapy failed until the patient either had a miraculous recovery (for which the bloodletters took credit) or died (which was more likely).”

As they document, workers today aren’t recreating the dread “wage-price spiral” of the 1970s: despite low levels of unemployment, workers wages still aren’t keeping up with inflation. Inflation itself is falling, for the fairly obvious reason that covid supply-chain shocks are dwindling and substitutes for Russian gas are coming online.

Economic activity is “largely below trend,” and with healthy levels of sales in “non-traded goods” (imports), meaning that the stuff that American workers are consuming isn’t coming out of America’s pool of resources or manufactured goods, and that spending is leaving the US economy, rather than contributing to an American firm’s buying power.

Despite this, the Fed has a substantial cheering section for continued interest rates, composed of the ultra-rich and their lickspittle Renfields. While the specifics are quite modern, the underlying dynamic is as old as civilization itself.

Historian Michael Hudson specializes in the role that debt and credit played in different societies. As he’s written, ancient civilizations long ago discovered that without periodic debt cancellation, an ever larger share of a societies’ productive capacity gets diverted to the whims of a small elite of lenders, until civilization itself collapses:

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2022/07/michael-hudson-from-junk-economics-to-a-false-view-of-history-where-western-civilization-took-a-wrong-turn.html

Here’s how that dynamic goes: to produce things, you need inputs. Farmers need seed, fertilizer, and farm-hands to produce crops. Crucially, you need to acquire these inputs before the crops come in — which means you need to be able to buy inputs before you sell the crops. You have to borrow.

In good years, this works out fine. You borrow money, buy your inputs, produce and sell your goods, and repay the debt. But even the best-prepared producer can get a bad beat: floods, droughts, blights, pandemics…Play the game long enough and eventually you’ll find yourself unable to repay the debt.

In the next round, you go into things owing more money than you can cover, even if you have a bumper crop. You sell your crop, pay as much of the debt as you can, and go into the next season having to borrow more on top of the overhang from the last crisis. This continues over time, until you get another crisis, which you have no reserves to cover because they’ve all been eaten up paying off the last crisis. You go further into debt.

Over the long run, this dynamic produces a society of creditors whose wealth increases every year, who can make coercive claims on the productive labor of everyone else, who not only owes them money, but will owe even more as a result of doing the work that is demanded of them.

Successful ancient civilizations fought this with Jubilee: periodic festivals of debt-forgiveness, which were announced when new monarchs assumed their thrones, or after successful wars, or just whenever the creditor class was getting too powerful and threatened the crown.

Of course, creditors hated this and fought it bitterly, just as our modern one-percenters do. When rulers managed to hold them at bay, their nations prospered. But when creditors captured the state and abolished Jubilee, as happened in ancient Rome, the state collapsed:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/07/08/jubilant/#construire-des-passerelles

Are we speedrunning the collapse of Rome? It’s not for me to say, but I strongly recommend reading Margaret Coker’s in-depth Propublica investigation on how title lenders (loansharks that hit desperate, low-income borrowers with triple-digit interest loans) fired any employee who explained to a borrower that they needed to make more than the minimum payment, or they’d never pay off their debts:

https://www.propublica.org/article/inside-sales-practices-of-biggest-title-lender-in-us

[Image ID: A vintage postcard illustration of the Federal Reserve building in Washington, DC. The building is spattered with blood. In the foreground is a medieval woodcut of a physician bleeding a woman into a bowl while another woman holds a bowl to catch the blood. The physician's head has been replaced with that of Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell.]

#pluralistic#worker power#austerity#monetarism#jerome powell#the fed#federal reserve#finance#banking#economics#macroeconomics#interest rates#the american prospect#the great inflation myths#debt#graeber#michael hudson#indenture#medieval bloodletters

464 notes

·

View notes

Text

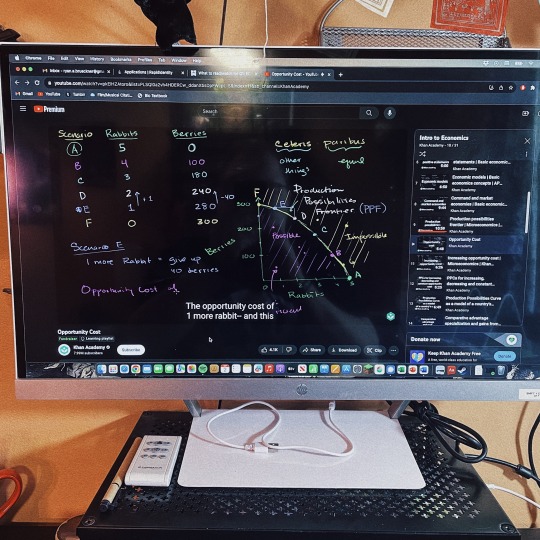

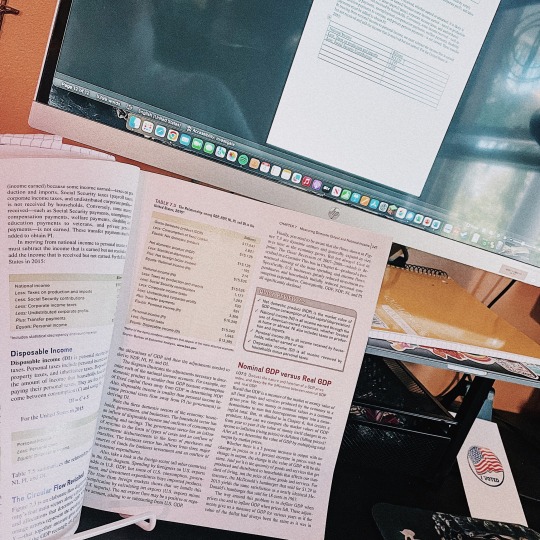

Day 63 • 100 Days of Productivity

today was a macroeconomics speed study! i haven’t had time to do my macro work because my other (in person) classes are taking up a lot of my time and i haven’t had much time for my online classes. fortunately i got everything done and i still have tomorrow before everything needs to be turned in so i can do some more responses on the discussion board to get more credit. todays work was about PPFs and opportunity costs

🎶 dear future self (hands up) - fall out boy 🎶

#studyspo#studyblr#100 days of productivity#collegeblr#studentblr#uniblr#studying#study#inspiration#motivation#motivator#inspo#study aesthetic#student#student life#college student#uni student#macroeconomics#greenhouse.txt#university student

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

I get my money back from hospitals in condoms.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

29.03.2024

There's nothing much decrease or increase in study sessions. I am just completing notes which i had postponed till i get a perfect idea and clarity of concept/topics. There's a lot of writing and i worry if I will even be able to learn all that what I'm writing. Every night my fingers gave out, from continuously writing. But over all its good.

Things I did:

Macroeconomics: notes writing

Song of the day: drunk text by Henry Moodie

Good luck to me for tmr

#study with me#studyblr#studyblr community#study motivation#study space#study aesthetic#study blog#study inspo#study stuff#macroeconomics#study notes#student life#student#revision#long reads#writing notes#notes#numerical

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

#socialism#capitalism#economics#macroeconomics#anti capitalism#anti capitalist#democratic socialism#leftism#leftists#leftist#replace the constitution

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The geraniums have been clamoring for affection and insisting I take their pictures. I said, I've got to pay attentions to the daisies and the coleus, the rockroses and the lilies, the trumpet flowers mandevilla and coneflowers too. But no.

So here's a geranium dump to liven your day.

Sorry for the long post, but hopefully the geraniums will leave me alone for a bit and let me do my chores.

#lotta flowers#inner life of flowers#macro flower#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#flowers of tumblr#macro photography#macrolove#macroeconomics#flowers on tumblr

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ko-Fi Prompt from adam:

macroeconomics, how stuff affects LRAS + SRAS? doesn't necessarily need to be ELI5 if it's easier for you to reference other econ terms

I actually had to check what "ELI5" means and apparently it's "Explain Like I'm Five." Never seen that before but it does make sense.

Here's (significantly more than) five hundred words on macro econ.

I cannot promise that this is how your teachers want you to view things. A lot of this is being processed through "cynical business major that came out the other side of college with a grudge against other business majors."

LRAS: Long run aggregate supply. This is a theoretical model that allows for multiple elements of the economy to be variable in the larger context. We are looking at long-term effects to shifts in the economy. LRAS assumes that aggregate supply is functionally unchanging in the long run, and only ever shifts temporarily. If one element shifts, the others will compensate (e.g. a rise in prices will result in lower quantities, but the total sold in dollar amount will be the same). This is in part because the model assumes that production is working optimally.

SRAS: Short run aggregate supply. This is a theoretical model that fixes most variables and looks at only the effects of individual aspects. Think of it as viewing only the immediate effects of a change to one element, with the assumption that nothing else will change.

What is aggregate supply?

Aggregate supply is, functionally, 'the total price of everything we can sell in a country during a given time.' All the money that is spent, on basically anything, combined. Your rent, your groceries, your tuition, your phone, and anything else (that is not imported), only for everyone in the country. All the money that changes hands is included except imports... and maybe wages.

People seem very keen to not include wages unless it's for direct-to-consumer services. I wasn't sure and tried to look it up for you, and people are very concerned with how wages affect AS, and not very concerned with explaining if "the $20k I paid my employee" is something that gets counted in this whole process.

"Wow that sounds like the GDP." It is. You can mince words about things like imports and exports, taxes, and so on, but GDP is one form of measuring aggregate supply (not including unreported income or illegal sales of drugs, etc).

What is Aggregate Demand?

The reverse! It is the amount of money people are willing to spend. Does that sound confusing? It is.

Aggregate Supply is the collective sales of goods produced, so it includes everything we make, including exports, like integrated circuits, petroleum, and cars.

Aggregate Demand is the collective sales of goods demanded, so it includes everything we buy, including imports, like Korean skincare, pharmaceuticals, and cars.

What affects Aggregate Supply?

AS is affected by numerous factors, but primarily labor, wage rates, general prices, and available financial capital.

(Assume everything is adjusted for inflation.)

Labor

If labor sharply decreases (e.g. COVID hits and unemployment skyrockets), then the Aggregate Supply nosedives, even if Aggregate Demand doesn't dip as sharply.

For our COVID example: People still need food and toilet paper, so the Demand for physical goods isn't affected as severely, but Supply goes down, and Services outside the medical industry take a nosedive; people are much less likely to get a non-necessity service (like massages, live entertainment, or housecleaning) when the people doing that work are often unable to work legally at all, due to legal restrictions.

LRAS assumes that either product costs will rise, or that labor will return to normal after a period of time, and that Aggregate Supply will return to equilibrium after a period of time. On a small scale, things that can affect labor are certification (e.g. if the government suddenly requires a certain license to practice a trade, labor will dip until people have that certification), wages (lower wages mean fewer employees), and worker safety (the revelation that a common element of production is highly carcinogenic and requires greater safety precautions means fewer people are willing to work for a minimum wage... in theory).

Of course, those last two are a lot less influential when the minimum wage is so low that people have to take any job they can find just to afford groceries, but that's another rant.

Price

This is most noticeable with luxury goods. In a traditional supply and demand curve, an increase in cost will lower demand for a product. However, many products do not respond to prices in that manner, due to being necessities. People cannot go without insulin, gas for their commute, or food (even shitty food), and so an increase in general costs can lead to a short bump in Aggregate Supply on the basis of people paying more across the board for things they can't go without, even if they have to take out loans to do it. In the long run, though, AS eventually shifts back to equilibrium, either through market costs being forced down by public outcry or government intervention, or through the people who couldn't afford these things just... dying off.

Fun fact: the lipstick effect is used to describe people in economic downturns ceasing to buy large luxuries (like a new car), but still buying small luxuries (like lipstick) to keep up morale, since it's a much smaller hit to the bank account, but provides a similar dopamine boost in a bad situation.

Wage Rates

If you're like me, your first instinct is that a depressed wage means fewer purchases across the board. Surprisingly, this is not what the usual use of wages in SRAS is.

AS theories assume that a rise in demand will lead to companies seeing a rise in sales, and thus hiring more workers at slightly higher wages in order to meet that demand.

In AS theory, higher wages mean greater labor, mean greater production, and thus higher AS.

(Same result, different reasoning. I view wages as being an element of how much people are able to purchase, and thus how AD affects AS.)

Available Financial Capital

This is an easy one: the more money a company has available, to spend on wages, supplies, and equipment, the more they can produce. If all companies are given more capital (see: stimulus bills, loosened restrictions on banks giving out small business loans, a miracle in which all of Jeff Bezos's money is seized and redistributed to the many small businesses he was cannibalizing), then Aggregate Supply rises.

----

Anyway, that ended up much longer than the 500 words I promised. If you enjoyed this "Economics for Dummies" segment, please toss me a donation on Ko-fi, or sign up for my patreon! I promise I'll appreciate it. (Prompts not necessary, but open.)

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction to Economics Vocabulary

Economics

-- study of how people satisfy their needs and wants

-- people must make choices

Scarcity

-- there are limited amounts of goods and services

-- people have unlimited wants

Factors of Production

-- abbreviated FOPs

-- resources used to make goods and services

-- includes capital, labor, and land

Capital

-- manmade resources

-- used to produce goods and services

Physical Capital

-- manmade objects

Human Capital

-- knowledge and skill of a worker

#studyblr#notes#economics#economics notes#economics vocabulary#economics vocab#vocab#vocabulary#introduction to economics#econ#econ notes#macroeconomics#macroeconomics notes#capital#human capital#physical capital#factors of production

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just got a solid hour of Spotify without an ad… I totally flunked the multiple choice this morning.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is the only currency I am accepting from now on:

@gretasmokerising

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tim "Smashed Avo" Gurner

Hey Folks,

If you're wondering where this bell-end comes from in the world, he is unfortunately an Aussie. He is also one of our more loathed form of capitalist jerkwads: The Property Developer. Plus he's the wangrod who decided that...

When talking about property prices 3 years before the pandemic was responsible for the equally out of touch shit-take of... "The young folks shouldn't be buying avocado toast if they want to buy a home..."

So yeah, he's just full of shit takes.

The more amazing thing about this kind of shit take is that Gurner is basically saying the 'Neoclassical/Neoliberal Quiet Part Out Loud'.

Unemployment is the only way neoclassical economics thinks to control inflation. And it's a bit Rube Goldberg at the same time.

Buckle in folks, we're going for a deep dive into a land of wild fantasy and nonsense: mainstream macroeconomics.

But how do we stop the inflations?!

In the Neoclassical pattern, you need to remember the fantasy starts with how they describe the economy already as it is and how prices happen.

Step 1: The economy will already be producing everything it can and prices are directly linked to the amount of Government Money.

Yep, you read that right... the main pile of economic thinking says that economies around the world are already making as much stuff as they could. They're importing everything they could, and the people who are here are already making as much as they possibly could.

This gets glued into the next thing which is The Equation of Exchange; MV = PQ. You'll see this bandied around and from a maths sense this is the most boring mundane crap of an equation possible but once you start trying to make it match RL goings on makes zero sense. M = the government money out there, V = Velocity of money (put a pin in this one! Oh boy!), P = prices, Q = the number of times people pay those prices.

It has variations where the PQ will be "P = Average Price, Q = All transactions in the average" or "PQ is actually the sum of every price P and the Q times that price was paid". They work out to be the same in the long run: the total of all the things people bought/sold. Now, remember the first half... we are already making the most stuff we can which means that Q is basically 'fixed' (we don't have more stuff to buy and sell) for any given period of time. They also tend to assume that 'Velocity of Money is constant' (which yeah oh boy... just oh boy). So if you change M (government money) there's only one thing that can happen: Prices move. If you spend more government money, then Prices have to go up. That's part of the logic, which is why they keep scaring you with Spending More Government Money Will Make The Inflations.

(Velocity of Money is meant to represent some kind of how often the money moves between people, but this is bonkers because everything is done on spreadsheets now and editing values is spreadsheets creates and destroys stuff constantly, so how fast is money moving? Also, banks settle net transaction not every single transaction. If your bank needs to send $10m to another bank, but that bank needs to send $11m to your bank, then the other bank sends $1m to your bank... that's it job done. They don't pass all the millions back and forth. So this whole idea of the velocity of money as a thing is nonsense, and then on top of it if you're at all scientifically inclined... try do a unit-substitution on MV=PQ, notice the units for V and realise what that would mean if you were doing that in Chem or Physics... let your brain melt on that one).

Step 2: But the Wage Price Spirals! Supplies and Demands!!!

Supply-and-Demand curves have something super wild going on. It gets glossed over a lot, but...

Supply and Demand curves assume the whole economy has only one thing in it, and everyone wants that one thing exactly the same as each other.

Yep. A supply and demand curve assumes everyone in Australia likes Victoria Bitters beer as much as everyone else AND that the only beer available in this fine nation of indigenous folks, migrants, forced migrants, and colonialist fucks, is Victoria Bitters. There is one beer: VB, and everyone wants it exactly the same amount. Welcome to Neoclassical/Mainstream economics.

What does this mean for inflation? If people have more money to buy stuff, then they'll push up prices! The demand (wanting a thing PLUS having the cash to buy it) will beat supply (which remember is already maxxed out) and push up prices!!!

How do we stop this?

Make sure people don't have as much money to spend on things.

Yep, you stop this by making people broke.

What is a great way to make people broke? Increase unemployment.

How do you go about doing that?

Central Bank Interest Rates... it's all a bit Rube Goldberg, but this is the monetarist solution to everything in the economy... fuck with the rates.

If you push up rates, loan costs go up, people and businesses have to spend more to cover their loans. That means people can't buy as much stuff. That means their rents potentially go up. That means food prices go up. And businesses can't afford to keep on as many staff. Unemployment goes up. That's the trick. Rates go up (insert bowling balls playing pianos to knock a switch to drive a remote control car) and then unemployment goes up.

Then when people aren't buying, inflation slows down. Then they drop rates.

But notice the funny thing... generating more unemployment requires the prices of stuff to go up because the rates go up. They make inflation to stop inflation... it's so fucking bonkers. We will crash this car into a tree faster now so we don't maybe crash into that cliff wall up ahead.

So yeah, Tim "Smashed Avo" Gurner isn't lying because that is the goal: to crush inflation by crushing employment.

#tim gurner#economics#macroeconomics#neoliberalism is a disease#neoclassical economics is a fantasy world

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The problem with economic models

When students of statistics are introduced to creating and interpreting models, they are introduced to George Box’s maxim:

All models are wrong, some are useful.

It’s a call for humility and perspective, a reminder to superimpose the messy world on your clean lines.

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this article to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/03/all-models-are-wrong/#some-are-useful

Even with this benediction, modeling is forever prone to the cardinal sin of insisting that complex reality can be reduced to “a perfectly spherical cow of uniform density on a frictionless plane.” Partially that’s down to human frailty, our shared inability to tell when we’re simplifying and when we’re oversimplifying.

But complex mathematics are also a very powerful smokescreen: because so few of us are able to interpret mathematical models, much less interrogate their assumptions, models can be used as “empirical facewash,” in which bias and ideology are embedded in equations and declared to be neutral, because “math can’t be racist.”

The problems with models have come into increasing focus, as machine learning models have increasingly been used to replace human judgment in areas from bail assessment to welfare eligibility to child protective services interventions:

https://memex.craphound.com/2018/01/31/automating-inequality-using-algorithms-to-create-a-modern-digital-poor-house/

But even amidst this increasing critical interrogation of models in new domains, there is one domain where modeling is all but unquestioned: economics, specifically, macroeconomics, that is, the economics of national government budgets.

This is part of a long-run, political project to “get politics out of budgeting” -a project as absurd as “getting wet out of water.” Government budgeting is intrinsically, irreducibly political, and there is nothing more political than insisting that your own preferences and assumptions are “empirical” while anyone who questions them is “doing politics.”

This model-first pretense of neutrality is a key component of neoliberalism, which saw a vast ballooning of economists in government service — FDR employed 5,000 economists, while Reagan relied on 16,000 of them. As the jargon and methods of economics crowded out the language of politics, this ideology-that-insisted-it-wasn’t got a name: economism.

Economism’s core method is reducing human interaction to “incentives,” to the exclusion of morals or ethics — think of Margaret Thatcher’s insistence that “there is no such thing as society.” Economism reduces its subjects to homo economicus, a “rational,” “utility-maximizing” automaton responding robotically to its “perfect information” about the market.

Economism also insists that power has no place in predictions about how policies will play out. This is how the Chicago School economists were able to praise monopolies as “efficient” systems for maximizing “consumer welfare” by lowering prices without “wasteful competition.”

This pretense of mathematical perfection through monopoly ignores the problem that anti-monopoly laws seek to address, namely, the corrupting influence of monopolists, who wield power to control markets and legislatures alike. As Sen John Sherman famously said in arguing for the Sherman Act: “If we will not endure a King as a political power we should not endure a King over the production, transportation, and sale of the necessaries of life.”

https://marker.medium.com/we-should-not-endure-a-king-dfef34628153

Economism says that we can allow monopolies to form and harness them to do only good, enforcing against them when they abuse their market dominance to hike prices. But once a monopoly forms, it’s too late to enforce against them, because monopolies are both too big to fail and too big to jail:

https://doctorow.medium.com/small-government-fd5870a9462e

Today, economism is helpless to do anything about inflation, because it is ideologically incapable of recognizing the inflation is really excuseflation, in which monopolists blame pandemic supply shocks, Russian military belligerence and supposedly overgenerous covid relief programs for their own greedy profiteering:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/03/11/price-over-volume/#pepsi-pricing-power

Mathematics operates on discrete quantities like prices, while power is a quality that does not readily slot into an equation. That doesn’t mean that we can safely discard power for the convenience of a neat model. Incinerating the qualitative and doing arithmetic with the dubious quantitative residue that remains is no way to understand the world, much less run it:

https://locusmag.com/2021/05/cory-doctorow-qualia/

Economism is famously detached from the real world. As Ely Devons quipped, “If economists wished to study the horse, they wouldn’t go and look at horses. They’d sit in their studies and say to themselves, ‘What would I do if I were a horse?’”

https://pluralistic.net/2022/10/27/economism/#what-would-i-do-if-i-were-a-horse

But this disconnection isn’t merely the result of head-in-the-clouds academics who refuse to dirty their hands by venturing into the real world. Asking yourself “What would I do if I were a horse?” (or any other thing that economists are usually not, like “a poor person” or “a young mother” or “a refugee”) allows you to empiricism-wash your biases. Your prejudices can be undetectably laundered if you first render them as an equation whose details can only be understood by your co-religionists.

Two of these if-I-were-a-horse models reign invisibly and totally over our daily lives: the Congressional Budget Office model and the Penn Wharton Budget model. Every piece of proposed government policy is processed through these models, and woe betide the policy that the model condemns. Thus our entire government is conducted as a giant, semi-secret game of Computer Says No.

This week, The American Prospect is conducting a deep, critical dive into these two models, and into the enterprise of modeling itself. The series kicks off today with a pair superb pieces, one from Nobel economics laureate Joseph Stiglitz, the other from Prospect editor-in-chief David Dayen and Rakeen Mabud, chief economist for the Groundwork Collaborative.

Let’s start with the Stiglitz piece, “How Models Get the Economy Wrong,” which highlights specific ways in which the hidden assumptions of models have led us to sideline good policy (like increasing spending during recessions) and make bad policy (like cutting taxes on the rich):

https://prospect.org/economy/2023-04-03-how-models-get-economy-wrong/

First, Stiglitz sets out a general critique of the assumptions in neoclassical models, starting with the “efficient market” hypothesis, that holds that the market is already making efficient use of all our national resources, so any government spending will “crowd out” efficient private sector activity and make us all poorer.

There are trivially obvious ways in which this is untrue: every unemployed person who wants a job is not being used by the market. The government can step in — say, with a federal jobs guarantee — and employ everyone who wants a job but isn’t offered one by the public sector, and by definition, this will not crowd out private sector activity.

Less obvious — but still true — is that the private sector is riddled with inefficiencies. The idea that Google and Facebook make “efficient” use of capital when they burn billions of dollars to increase their surveillance dragnets is absurd on its face. Then there’s the billions Facebook set on fire to build a creepy dead mall it calls “the metaverse”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EiZhdpLXZ8Q

Then we come to some of the bias in the models themselves, which consistently undervalue the long-run benefits of infrastructure spending. Public investments of this kind “yield very high returns,” which means that even if a public sector project reduces private sector investment, the private investments that remain produce a higher yield, thanks to public investment in a skilled workforce and efficient ports, roads and trains.

A commonplace among model users is that we must make “The Big Tradeoff” — we can either reduce inequality, or we can increase prosperity, but not both, because reducing inequality means taking resources away from the business leaders who would otherwise build the corporations whose products would make us all better off.

Despite the fact that organizations from the OECD to the IMF have recognized that inequality is itself a brake on economic growth, fostering destructive “rent seeking” (seen today online in the form of enshittification), the most common macroeconomic models continue to presume that an unequal society will be as efficient as a pluralistic one. Indeed, model-makers treat attention to inequality as an error bordering on a mortal sin — the sin of caring about “distributional outcomes” (that is, who gets which slice of the pie) rather than “growth” (whether the pie is getting bigger).

Stiglitz says that model makers have gotten a little better in recent years, formally disavowing Herbert Hoover’s idea of expansionary austerity, which is the idea that we should cut public spending when the economy is shrinking. Common sense tells us that this will make it shrink faster, but expansionary austerity (incorrectly) predicts that governments that cut spending will produce “investor confidence” and trigger more private investment.

This reliance on what Paul Krugman calls the “Confidence Fairy” is tragically misplaced. Hoover’s cutbacks made the Great Depression worse. So did IMF cutbacks in “East Asia, Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Ireland.”

Expansionary austerity is politics dressed up as economics. Indeed, the political ideology subsumed into our bedrock models has caused governments to fail to anticipate crisis after crisis, including the 2008 Great Financial Crisis.

The politics in modeling are especially obvious in the process running up to the Trump tax cuts (as is often the case with Trump, he draws with a fisted crayon where others delicately shade with a fine pencil, making it easier to see the work for what it is) (see also: E. Musk).

Axiomatic to model-building is the idea that if you tax something, you’ll get less of it (“incentives matter”). The theory of corporate tax cuts goes like this: “if we tax corporations for the money they might otherwise use to build new plant and hire new workers, they will do less of those things.”

That’s a reasonable assumption — which is why we don’t tax companies on capital investments and their payrolls. These expenses are deducted from a company’s profits before it calculates its taxes. Corporate taxes are levied on profits, net of spending on labor and plant.

But when the CBO modeled the Trump cuts, it operated on the assumption that the existing tax system was punishing companies for hiring people and expanding operations, and thus concluded the reducing taxes would lead to more of these activities. On that basis, the tax cuts were declared to be expansionary, a means of driving new private sector activity. In reality, all they did was create more profits, which rich people used to bid up the prices of assets, creating a dangerous asset bubble — not investment in productive capacity.

In “Hidden in Plain Sight,” the other Prospect piece that dropped today, Dayen and Mabud tell us just how wrong the models were about the Trump cuts:

https://prospect.org/economy/2023-04-03-hidden-in-plain-sight/

The CBO predicted that the cuts would drive a 0.7% increase in GDP over a decade, while Penn Wharton predicted 0.6–1.1% growth. Both were very, very wrong:

https://www.npr.org/2019/12/20/789540931/2-years-later-trump-tax-cuts-have-failed-to-deliver-on-gops-promises

Despite the manifest defects of these models, we still let them imprison our politics. When Elizabeth Warren proposed a 2% wealth tax on assets over $50m, she asserted that this would reduce billionaires’ fortunes by $3.75T over 10 years, but the Penn Wharton model knocked $1T off it, and declared that the real impact of the policy would be a reduction in investment, depressing long-run growth. The politics of a wealth tax are sound — the kind of politics that wins elections and restores faith in democracy — but the economism of models sweeps the proposal off the table and into the dustbin of history.

The Penn Wharton model simply refuses to factor in absolutely key aspects of a wealth tax plan, from the impact of increased enforcement to the economic benefits of universal child care, increased education funding, student debt cancellation and other programs that could be enacted with the fiscal space opened up by reducing billionaires’ spending power.

The Warren policy is rare because we got to hear about it — through a national election campaign — before it was strangled by the model-makers. More often, proposals like this are quietly snuffed out even before they’re introduced to the legislature, when they are run through the model and told Computer Says No.

Modeling isn’t intrinsically bad, but “all models are wrong” and what determines whether a model is useful are the politics of its assumptions. Economism insists that there are no politics in model-making, which creates unfixable flaws in its models.

One core political assumption in economism’s models is that government shouldn’t exercise power to produce outcomes — rather, it should “nudge” markets with incentives (which, we are constantly reminded, “matter”). This means that we can’t ban pollution — we can only offer “cap and trade” systems to incentivize companies to pollute less. It means we can’t do Medicare For All, we can only “bend the cost-curve” with minor interventions like forcing hospitals to publish their rate-cards.

Economism — and its institutions, like the CBO — are “short-run Keynesian and long-run classical” — that is, they only consider the benefits of public spending over the shortest of timespans, and assume that these evaporate over long time-scales. That’s exactly backwards, as anyone who’s ever traveled on a federal highway or visited a national park can attest:

https://prospect.org/politics/congress-biggest-obstacle-congressional-budget-office/

All of this is worsened by politicians, who exploit the primacy of economism to attack their adversaries. When the CBO or Penn Wharton release a report on a policy, they often wrap their conclusions with caveats about uncertainties and ranges — but these cautions are jettisoned by opportunistic politicians who seize a single headline figure and use it as a club against their opponents.

In the coming week, the Prospect will run deep dives into the defects of CBO and Penn Wharton, along with other commentary. It’s very important work, throwing open the doors to the inner sanctum of economism’s sacred temple. I’ll be following it eagerly.

Have you ever wanted to say thank you for these posts? Here’s how you can: I’m kickstarting the audiobook for my next novel, a post-cyberpunk anti-finance finance thriller about Silicon Valley scams called Red Team Blues. Amazon’s Audible refuses to carry my audiobooks because they’re DRM free, but crowdfunding makes them possible.

Image:

bert knottenbeld (modified)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/bertknot/8375267645/

CC BY-SA 2.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

[[Image ID: A Tron-like plane of glowing grid-squares. Two spherical cows roll about on the plane, chased by motion lines. The gridlines are decorated with complex equations from the Penn-Wharton Budget Model.]]

#pluralistic#the american prospect#penn wharton budget model#some models are useful#congressional budget office#macroeconomics#all models are wrong#joseph stiglitz#economism#inevitabilism

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

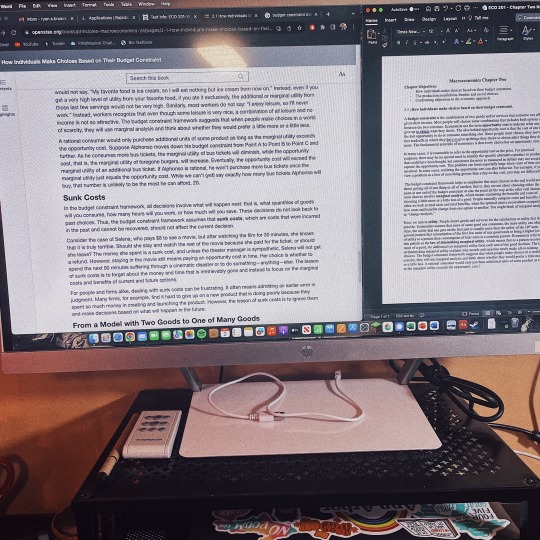

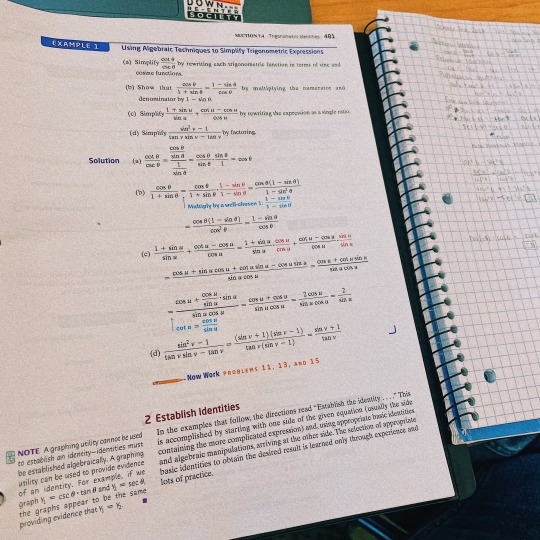

Day 72 • 100 Days of Productivity

i currently have a 100.87% in precalc ii and i have no fucking clue how. math has never been my strong suite but i guess that’s turning around. i mean, my lowest grade is a 94% so it’s not like im failing my other classes but i’ve never been a math person lol. lots of studying this week, midterms are coming up soon.

🎶 icarus & apollo - ripto 🎶

#studyspo#studyblr#100 days of productivity#student aesthetic#study aesthetic#studying#study#greenhouse.txt#collegeblr#inspiration#uniblr#college#uni#university#studentblr#student#study blog#study with me#math#macroeconomics#studystudystudy#studyblr community#student life#100dop#motivation#study motivation#study inspiration#study inspo#inspo

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why America is Losing the World to China: A Deeper Understanding

Welcome to our blog post, where we delve into the intriguing topic of why America is losing the world to China. In this thought-provoking piece, we aim to provide you with a deeper understanding of the dynamics at play, exploring various factors that have contributed to China’s rise and America’s decline in global influence. Through examining the economic, political, and cultural aspects, we hope…

View On WordPress

#brics#brics vs g7#china#china brics#china saudi arabia#china us dollar#china us treasuries#china vs united states#china vs usa#de-dollarization#dollar#economic news#economic war#fed rate hikes#gold#investing news#macroeconomics#petrodollar#petroyuan#recession 2023#sean foo#us china#us china economic war#us china relations#US China trade war#us dollar#us dollar hegemony#us treasury dump#why america is losing to china#why china is winning against america

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

19.03.2024

Everything is going with the flow in my study related aspects but there is a storm in my social life at school. My classmates that used to be my friends hates me now and i dont give two fucks about it but it is mentally tiring to go to school and be in that toxic environment for hours. But nonetheless i gotta do what I need to. So whatever it takes.

Things I did:

Political science: Textbook reading

Human Geography: Human development -- textbook reading

Macroeconomics: solving practical questions (mostly numericals)

Song of the day: anything 4 u by LANY

Good luck to me for tmr.

#study with me#studyblr#studyblr community#study motivation#study space#political science#study aesthetic#study blog#study inspo#study stuff#study notes#student life#student#human geography#macroeconomics#textbook#reading#numerical

8 notes

·

View notes