#maximum security

Text

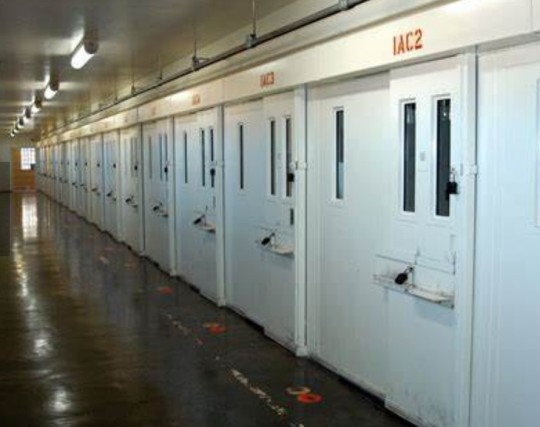

Orange and White, but no stripes

Lucasville, Ohio

Google maps: https://maps.app.goo.gl/HZ1LaaNafvajzkQC9

Note the leg irons held by the guards.

From: Hard Time, Prime Video S2 E8 - Worst of the Worst

And: Maximum Security | Hard Time National Geographic https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=97JvUUBG-00

#orange and white#no stripes#maximum security#prisoners#Lucasville#Ohio#Southern Ohio Correctional Facility#Prison#leg irons

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cuffed and locked.

#convict#prisoner#locked up#jail#prison#inmate#handcuffed inmate#handcuffed prisoner#maximum security

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maximum Security

Vol. 2

Eddie Munson X Fem!Reader

A/N: sorry it took me so long to write this 🫣 i hope you guys still enjoy reading!! thank you for all the love 🫶🏽

Vol.1

TW// mentions of violence, m*rder

The morning after is mostly a blur. You were still wrapping your head around everything that had happened just hours before. Getting out of bed was one of the hardest things you’d had to do in months. Harder than giving birth, you’d say. But you had a child to take care of, and now a husband to bail out of jail.

You got Leila changed and dressed for the day, sitting her in her highchair for breakfast while you made a quick phone call to Joyce. You asked her when Hopper’s shift started so that you could be there as soon as he came in.

Hopper had known both you and Eddie nearly your entire lives. For both good reasons, and some bad ones. But he always treated you both like his own children. Maybe it was because Wayne was one of his best friends in high school, or maybe it was because he just wanted you both to feel like you had someplace or someone to call home, since neither of you had that growing up. But, no matter what the circumstance was, he was always there to help and protect both of you.

Joyce told you he should be at the station in about 30 minutes and that he would be expecting you. She gave you her sympathy and told you if you needed anything you and Leila were always welcome at their house.

You hung up the phone, quickly getting dressed and looking somewhat presentable before loading Leila in the car and practically racing to the police station.

You see Hopper pull into the lot just seconds before you do. He clocks you as soon as he gets out of the van, standing and waiting for you.

Putting the car in park, you load Leila into her stroller before walking to meet with Hopper.

“Hey kid.” He pulls you in for a hug, a little longer than his usual. “How you holding up?”

You shake your head, trying not to let the tears that have been brewing all morning fall. “Been better.”

Hop just nods, leading you into the building. He greets everyone at the door and tells you to wait in his office as he makes you a cup of coffee. You’re sure he can tell you need it by the dark rings around your puffy eyes.

Sitting in his office for what feels like an eternity, all you can do is stare at your sleeping baby. Thinking about how the love of your life could do this to you, to your daughter, even to himself. He was supposed to be bettering himself. Walking down the right path, the path of a wholesome family man. Not the path of attempted murder.

You’re pulled away from your thoughts as you hear the door open, Hopper walking in with two coffee cups, setting one on the table in front of you before plopping down into his chair.

You both sit in silence for a moment, enjoying your fresh cups of coffee and the morning breeze. The slightest moment of peace you’ve been able to get in the last 12 hours.

“How old is she now?” Hopper asks, smiling at Leila.

“6 months.” You smile, combing her hair with your fingers. “It’s been hard… but I know it’ll be worth it one day.”

“It’s worth it now. You’ve got a beautiful baby.”

“And a husband in jail.” You respond, looking back to him. He sighs, a sympathetic look crossing his face.

“So how much is the bail?” You reach down for your purse, rummaging through your wallet. “I brought my checkbook and I know I don’t have much, but I could at least put somewhat of a down payment down if that would work.”

“Y/N…” He breathes.

“Or if it’s too much I could look into a bondsman I guess.”

“Y/N.”

“I could call my dad. He doesn’t like Eddie but I know he’d rather not have me raise a baby alone.”

“Y/N.” His volume gets a little louder, but you choose to ignore it.

“Or- or Steve! I feel bad asking him for so much but I know he’d help at the drop of a hat and-“

“Y/N!” Hopper shouts, stopping you dead in your tracks. “Eddie’s not getting bailed out.”

“Of course he is, that’s why i’m here Hopper.” You scoff.

“He is the prime suspect in a murder, kid.” You shake your head, not wanting to listen.

“No- no they said- they said he was okay. He got hurt but he was at the hospital and he was going to be okay.” Your chest starts to tighten, as your breathing become shallow.

Hopper takes your hand in his. “Jason died this morning. They tried their best but… he didn’t make it.”

Wait, What? Jason? As in Jason Carver? God dammit, Munson.

“Jason… Jason who?” You ask Hopper, your breathing becoming shallow once again.

“You know which one. Carver.” You scoff, looking away. Sure, they never liked each other but for Eddie to kill him? You would’ve thought it would be the other way around. “What was their… relationship like?”

You chuckle. Out of all people, Hopper should know the answer to that question. “They hated each other, Hop. You know that. But, I thought we all grew up and forgot about it…”

“So there wasn’t anything after school? No fights or anything like that?” He questions you further.

“No, no. Nothing like that. Trust me, if Ed would’ve run into him I would’ve been the first person to know.” You respond. “If either of them would’ve gotten hurt, I always thought it would be Eddie. He wouldn’t hurt a fly…”

The only reaction you can let out are a few tears. The information of your husband, the father of your child, being a murderer, becoming all too real at this moment.

“You know… when I first moved into the trailer with him and Wayne, there- there was this stray cat that would roam the park. She didn’t look like she was taken care of very well. But Eddie, Eddie always left food and water out for her. He took her inside when it would rain. He made her our unofficial child.” You laugh, remembering the way he treated that little kitten. But, you were soon brought back to reality. The tears formed once again as you remembered where Eddie was now. “Where is he? Can I see him?” You ask, wiping the stray tear off of your cheek.

Hopper nods, opening the door and leading you to the few holding cells in the back of the building. He looks at you, silently asking if you’re sure you want to do this, before you send a nod his way. Before he’s able to turn the door handle, you interrupt him.

“Wait.” Hopper stops, looking back at you. “Can I leave Leila with someone out here? I don’t want her to… see him… like that.” He looks back at one of the officers behind you, nodding for him to come over.

“Can you watch the little girl while we go talk to Eddie?” The officer agrees, grabbing hold of the stroller before Hopper ushers you into the holding room.

Walking in, you’re immediately met by Eddie. He’s sitting on the cold metal bench behind the metal bars, his eyes dark and heavy, he’s probably spent most of his time in there crying.

“Baby…” His eyes light up slightly, taking in your presence. “Thank god you’re here baby, i’m so sorry. I’m so sorry for putting you and Leila through this, I- I just wanna go home. Can we go home now?”

You fight the tears beginning to form before walking closer to the cell. “What… the fuck. Wha- what the actual fuck is wrong with you, Munson?” Eddie flinches slightly, knowing you only call him by his name when you’re angry. “We were in a good place. Everything was great and then- then you went and- and you… you killed someone, Eddie! And Jason of all people? What were you thinking?” He furrows his brows, and you realize that Hopper hadn’t told him the news yet. “You’re not getting out. Not any time soon. I don't know what the fuck was going through your head but… we can’t help you this time.”

You walk away, heading for the door as you hear Eddie mumble jesus christ. You turn to look at him. He’s taken a seat on the cold bench, head in his hands as you hear soft cries leave his mouth.

“I love you, Eddie Munson. But you really did it this time.”

taglist: @choke-me-eddie @paranoidmunson @quinnypixie @joejoequinnquinn @kayleeelena97 @the-valkyrie-writes @darcyglewis @ceriseheaven @lovejosephquinn @aysheashea @reanimated-alice @lma1986 @expiredcum21 @munsonslure @avobabe87

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

If it were a crime to think of oneself as HILARIOUS, I would be in a maximum-security prison...

#comedian#lock me up#maximum security#evil#freak#hilarious#text post#lol#funny#humor#haha#original post#textpost#shit post#shitpost

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

evil lair

*congratulations you've reached LV 20! you're now qualified to start a colony!

sans: wtf.

sym: oh, yeah! yay! promotion! I can make a nest now!

sans: ... nest?

sym: when some of us grow beyond a certain point we become monarchs! kinda like the queen bees of the hivemind! LETS GO EAT MORE UNSUSPECTING VICT-

*air horn*

JOKE! IT WAS A JOKE! JESUS... anyways I think we really need a hide out. it was a joke. you're more than enough. a one monster army. I don't need any more underling- *air horn* BOSSES I DON'T NEED MORE BOSSES, you're the boss, boss! yessir!

[they are two homeless ass none human entities hiding from humans on the surface]

[sym made a nest, in a tiny hidden cave]

sans: I'm not going in hell's butthole.

sym: *offended* IT'S COMPLETELY SANITARY! I kill the bacteria that grows on the walls n stuff you know? it's completely clean and safe. the slime is just there for me to get around easier. besides I AM THE ENTIRE house. I can protect us and be aware of everything that goes on around the hide out! it's the minimum requirements for a monarch symbiot like me-

sans: I am not going in there.

sym: well I'm not sleeping on a bench! bones aren't exactly warm you know! you're not exactlywarm blooded! I would sleep in a bone made house, why can't you sleep in a blob made house?

sans:... *air horn threat*

sym: OKAY OKAY FINE, YOU WHINEY BITCH. JEEZ. we'll do it the "normal" boring way. we'll go see if there's an abandoned house. MUST YOU ALWAYS be a joy kill?

sans:my world, my rules. if you wanna stay you gotta do it my way. if I see you making a mess I'm installing speakers all over the walls with AMP and high-pitched music playing.

sym: ... dammit. at least leave the cobwebs

sans: why?

sym: evil lair aesthetic!

sans:...

sym: evil lair! evil lair! evil lair!

sans: can you just... be normal for one minute-

sym:SCREEEEEEEEEEE

#i mafe this into a comic!#will post it soon lol#symbiot au#sym would creep around the walls keeping watch#maximum security#the house would run on it's own power#biologically haunted house lmao#IMAGINE the automatic doors opening closing or the floor flattening as a trap#yeah you do not wanna go there without being invited#fr tho the house would CLEAN itself#what else do you need?

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

rush basado 😶

#rush doors#ambush doors#doors roblox#doors rush#doors ambush#prisoner jumpsuit#jumpsuit prison#prisoner#prison au#maximum security#adriana4ever#my art

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

If it was a crime to call grown ass men “babygirl” I’d be put in solitary confinement at Guantanamo Bay.

#ds9#tng#star trek#text post#all jokes here#maximum security#solitary confinement type beat#i specifically am referring to Garak#and data#also Julian#AND PICARD!!#Quark too#matter of fact#all of them

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHERUB HEADCANONS BECAUSE YES

(Also it's just lgbtqia+because yes)

Yeah it's just these cause they were the only characters I had headcanons for

(Also keep in mind that I'm only like in the first 100 pages of mad dogs so)

I'll probably make more tho

(Template by @jacksonsdiaryaddicted )

#robert muchamore#cherub series#cherub#cherub book series#the recruit#class a#maximum security#the killing#divine madness#man vs beast#the fall#mad dogs#cherub books

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maximum Security

(x)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"...despite all the mystery, there is simply no question that prisons were places of pervasive brutality, so pervasive as to make a Progressive model of community, school, or hospital less than relevant to their functioning. It is true that regulations outlawing corporal punishment of inmates did become prevalent in the twentieth century. By the 1930s, most systems prohibited the use of the whip as well as the ingenious nineteenth-century torture devices. Instead, solitary confinement became the permissible punishment of last resort, that is, at least officially. Lacking a calculus for pain, it is not always easy to measure one kind of punishment against another. But in no simple sense can the substitution of solitary for the whip be automatically considered a “reform.”

There were in fact two kinds of solitary: administrative segregation, where the prisoner was locked into a regular cell (lighted and ventilated, equipped with a bed, blanket, and toilet facilities ), fed three regular meals a day, and confined in this way for long periods of time, months rather than weeks. Then there was “solitary confinement” proper, the “hole” or the “pit” or the “cage” or the “dungeon,” as prison jargon called it. Every prison had one: the inmate was kept in a starkly bare concrete cell, unlighted and unventilated, and fed bread and water; at most, he received blankets and a bucket for his bodily needs. Confinement here was supposed to last for shorter periods - a week or two. Some regulations placed an upper limit of six or seven consecutive days in solitary, but wardens often violated them, in spirit if not in letter. They would keep prisoners in the hole for six days, release them for one, then put them back into the hole again for another six days, and the routine could stretch for months. Thus, even prisons nominaIIy obeying formal regulations administered a punishment that was hardly humane.

How often were the formal regulations themselves obeyed? How frequently did prison guards and wardens inflict punishments that the state had defined as cruel and unusual? Although no quantitative answer is possible, it is useful to explore one incident in detail, the response to a food strike in San Quentin. Not that the beatings there are an index to beatings elsewhere. Rather, the underlying assumptions of the prison staff, presented in defense of their actions, reveal with remarkable clarity how in the name of institutional security all punitive measures became legitimate: how, ultimately, a custodial prison was unable to exercise fair or humane discipline

In 1939, forty-one inmates in San Quentin went on a hunger strike to protest the quality of the institution’s food. They would not enter the mess hall or go to work until they had the chance to talk with the captain or warden. Punishment was immediate and the principal keeper sent them to solitary; what happened to them there became the subject of investigation. The San Quentin prison Board first conducted closed hearings and exonerated all the guards of charges of brutality. But then the state’s prison director reopened the case, and in November of that year, the governor himself heard testimony. No one, guards, inmates, or prison Board, disagreed on what had actually taken place; a number of the strikers were removed from solitary and forced to stand in a circle twenty-two inches across, and those who refused to follow this order were beaten. And no one denied that the California constitution prohibited cruel and unusual punishments in general, and corporal punishments specifically. But then how had such a violation occurred and why had the Board not taken more vigorous action?

The defense that guards and Board members offered is significant not as an accurate statement of motives, but as a presentation of a line of argument that they believed to be creditable and legitimate. Without such harsh action, the Board insisted, San Quentin would have become a “circus prison.” To discharge any of the guards who administered the beatings would “not only shatter the morale of every reformatory in California, but will undermine the discipline of every prison in the United States.” Were a new warden to be appointed, “he will inherit a situation where he must fight for the mastery of his prison or surrender to the convicts.” Indeed, “certain gang leaders within the walls are already celebrating their coming victory over rules and discipline.” And the guard responsible for the beatings was no less adamant in making this point. Had the core of troublemakers not been beaten, “it would have encouraged others to have done the same thing until there would have been a general disregard of the rules.” The issue was simple: “Was the prison to be run by the Warden or by the prisoners?"

Moreover, the very fact that the governor was now holding an open meeting threatened the good order of the prison. “A public hearing,” argued the defense lawyer, is “probably the most dangerous type of hearing that could be held . . . because of its effects on the convicts, on the prisoners, and on the people all over the State.” The Board had been right to hold its earlier investigation in secret; the most that the governor should do was to meet privately with prison managers. Calling inmates to testify weakened the internal security of the prison, and at the same time reduced its legitimacy among the general public.

Further, the governor lacked the authority to hold such a hearing, for the Board and its warden had “complete jurisdiction” over the prison. No one could second-guess them. “There is no authority by which you can limit the amount or the severity of the punishment, provided the circumstances in the original instance required it or justified it.” Such a doctrine as cruel and unusual punishment had no meaning within a prison: everything depended upon the amount of provocation and the staffs need to maintain control

To buttress these contentions, the guard in charge of solitary, one Lewis, explained the dynamics behind the escalation of punishment. A back-up sanction was always necessary behind the walls. If one penalty did not work, a harsher one had to come next - and this was true not only for this riot, but in the daily administration of the institution. When Lewis first arrived at San Quentin, solitary had been too lax: “It had been a failure . . . the men had no fear of solitary. . . . The men would lay back in there; they would talk and laugh and raise all the trouble that they cared to. . . . Solitary to them was a joke.” When the warden put him in charge, “the only orders I received was to keep order in solitary. I went at it very slowly and carefully.” First he instituted a rule of silence, then he took away all reading material, then the right to smoke. Still “they didn’t mind solitary.” So he “pinched down a little harder.” Beds were to be made in military fashion and could not be sat upon during the day. “But I still found that some men would stay there week after week.” So he tried an experiment: drawing a twenty-two inch circle and having the men stand in it for five hours a day, without turning about. “They were made to stand all in one [way] -facing in one direction.”

These procedures, seemingly adequate for ordinary circumstances, were not sufficient in the extraordinary case. Thus, when the food strikers sent to solitary refused to enter the circle, the only thing to do was to whip them. The circle too, in other words, needed a back-up, and that was flogging. Accordingly, Lewis beat them until they would stand on the spots. “If I had failed for one minute down there, we would have had rioting and bloodshed in San Quentin.” For final effect, he added a “thank-you” theory. “Even Ted Burns - one of the lowest degenerates here - two days after I had trouble with him, he called for me, and he said: ‘Mr. Lewis, I am almost glad you gave me that licking; in fact, it made me think; I haven’t been respectful to officers here, but I will be from now on.’ And he didn’t come back to solitary any more.”

The Board concurred with the thinking in this presentation. When the governor asked one member directly if whipping was a good prison practice, he responded: “I couldn’t let you put that in my mouth, Governor; but I can tell you this. I think that any restraint that the guards administered to the prisoners to the point of compelling them to obey the rules is justified, and that no prison can be conducted otherwise.” The argument had come around again to the good order of the prison.

Neither the assumptions nor the practices revealed in this case were unique to the California system. The need for a back-up sanction to solitary was felt almost everywhere. The Kentucky penitentiary abolished corporal punishment in 1920; but the National Society of Penal Information visited the institution nine years later to discover that the dozen men in solitary “were ‘in chains,’ that is, standing with one hand cuffed to the cell door and the other cuffed to the post supporting the upper gallery. They remained in that position throughout the working hours for periods of 5 to 20 days.” In Rhode Island, the Wickersham Commission reported that inmates “are cuffed by one arm to a ring in the wall about shoulder high. A strait jacket may be used.” In Joliet, Illinois, and Stillwater, Minnesota, inmates in solitary “were cuffed to the door of the cell about 12 hours a day.” Another popular practice was to confine men to a semicircular cage so tight that they could not sit down or move about. The solitary cells, reported an investigator of the Jackson, Michigan, prison, “(are equipped with so called ‘cage doors’ in addition to the solid steel plate forming the outer door. The cage door is a semi-circular, barred affair, so constructed that a person may be placed between it and the outer door of the cell. With both doors closed the victim is forced to stand upright, can’t turn around, or crouch.’’ The Ohio penitentiary at Columbus had a similar solitary and cage arrangement. “Confinement alone has never proved very effective,” observed the Attorney General’s survey, but prison administrators were well equal to the task of devising supplementary punishments.

The idea that prison officials ought to be free to run their institutions as they chose prevailed through the pre-World War 2 period and right up to the mid-1960s. Even before the recent prisoners’ rights movement, inmates had petitioned the courts for relief from one or another disciplinary practice, but judges invariably dismissed their cases, adhering strictly to a “hands off policy." As late as 1951, a federal judge hearing an appeal on a prisoner’s right to correspond summarily declared: “We think it is well settled that it is not the function of the courts to superintend the treatment and discipline of persons in penitentiaries, but only to deliver from imprisonment those who are illegally confined.” Courts assumed not only that wardens had administrative expertise but that prisoners enjoyed “privileges,” not “rights.” The courts had neither the inclination nor, as they saw it, a cause to intervene.

...

In effect, the state and the prison had struck a mutually agreeable bargain: As long as the warden ran a secure institution which did not attract adverse publicity (through a high number of deaths or riots or inhumane practices becoming publicly known), he would have a free hand to administer his prison as he liked. And most of the time, wardens fulfilled their side of the arrangement. The number of escapes from the state prisons was low. In the mid-1930’s, no breaks occurred from Attica or Clinton or Sing-Sing, or from Western Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Minnesota, Colorado, or Folsom. Less than five prisoners on the average escaped from Auburn, Menard in Illinois, Virginia, Eastern Pennsylvania, Maryland, Huntsville in Texas, or San Quentin. To be sure, wardens could not always prevent prison riots or the circulation of horror stories about cruel and inhumane punishment. But in the end, it was security that counted, not rehabilitation; and the prison administrators knew it, fashioned their routine accordingly, and survived in power.

The image that captures the essence of the American prison in these decades, then, is not one of inmates exercising in the yard or attending classes or taking psychometric tests, but of the physical presence of the walls. And the walls were incredible, rising twenty to thirty feet above the ground and going down another five to twenty feet below the ground, with anywhere from five to fifteen towers jutting out above them. The occasional legislator who questioned the enormous expense of erecting these structures was told in no uncertain terms that thirty feet was better than twenty-five feet for preventing inmates from scaling the walls, and that every extra foot below the ground was a necessary safeguard against their tunneling out. In the end, reformers, with all their grand hopes of transforming the institution, were up against the wall."

- David J. Rothman, Conscience and Convenience: The Asylum and Its Alternatives in Progressive America. Revised Edition. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 2002 (1980), p. 150-158

#penal reform#progressive penology#progressive politics#rehabilitation#penal modernism#american prison system#penology#prison security#maximum security#corporal punishment#prison discipline#prison routine#solitary confinement#history of crime and punishment#prison guards#academic quote#reading 2023#david rothman

0 notes

Text

Convict in Florida Prison Blues

Florida Prison cell and Transport Chains

Sliding solid door. Maximum security cell.

Striped pants. Two person cell.

Back of shirt.

#Florida Prison#Florida Prison Blues#Two person cell#Transport chains#Maximum security#inmate#convict

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maximum security for you.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

prison furniture

#prison#maximum security#installation art#brutalism#brutalist#brutalist architecture#furniture#concrete#urban exploration#haikyo#interior design#eldritch

1 note

·

View note

Photo

maximum security

0 notes

Text

112. Maximum Security, by Robert Muchamore

Owned: No, library

Page count: 277

My summary: Another mission for James Adams, and it's his most dangerous one yet. He's got no adult supervision, no backup, and no safety net. Just him and another agent, trying to bust out of Max with another prisoner so they can find that prisoner's criminal mother. But when the other CHERUB agent gets too badly injured, James finds himself all alone in a high-security prison...

My rating: 3/5

My commentary:

More CHERUB! I still don't know how to feel about this series. Part of it I think is that it's just a bit too young for me. When I was reading this originally I must have been somewhere between the ages of six and eight - teenagers to me seemed impossibly old. Now I'm twenty-seven, and anyone under the age of twenty is basically a baby. As such, I think I remember it as being more complex than it actually is, which makes the slightly more simplistic storytelling stand out to me as strange. It's not that I'm not enjoying them. Far from it, it's a nostalgic little trip through stories I genuinely used to like. It's just that their flaws are a lot more glaring, these days.

Ah, James. You misogynistic little boy. James has gotten over his homophobia in between books - well, sort of. His attitude now is 'Kyle being gay is still gross, but so long as I don't see it, it's fine', which is I suppose better, if still not good. He's making up for it in the shittiness stakes, however, by cheating on his girlfriend! Yep, James has gotten with Kerry, she's off on a mission in Japan, and he starts fooling around with the daughter of someone they're hiding out with. Lauren sees him and tries to get him to stop, for Kerry's sake, but he doesn't. The narrative doesn't really treat him as being wrong? He experiences no consequences in this book, and it's almost played for laughs, as Kerry immediately accuses him of cheating on her when he returns…only to find that she's referring to an incident with Kyle before he left. Ha ha, hilarious, except James still treats women as property. Ew. And despite the whole 'ew Kyle is gay' thing, James doesn't appear to have a problem joining skinheads in prison? Granted, he has to do it for the mission, but he doesn't seem to have much of an issue there.

The mission itself ups the stakes a little bit more. Now James is in a maximum security prison in America, attempting to get close to the son of a criminal mastermind. Adult agents are monitoring him, but unlike earlier where he was posing as their foster child, he has little contact with them and cannot easily get help. He has an older agent, Dave, with him - but Dave is injured early on and has to be evacuated. Lauren, newly qualified, is also on this one. She's not in the prison, but is a contact on the outside and is joining them for the breakout. Because, oh yeah, the mission is to escape from prison with this kid, then see if they can locate his mother based on what he does and who he calls. It's intense, and there's a lot that could go wrong. The agents have intelligence that the mother is loyal to those who do her a good turn, but she's also experienced in covering her tracks and turns on James and Lauren, promising them a foster home but asking her men to kill them. Lauren almost dies, suffocated in a motel, but manages to take down her attacker and get help from the others. And before that, the trio are completely alone after the breakout. The American police can't call off or half-ass the manhunt for two missing prisoners, so until they get to safety they are liable to be re-arrested or even killed. It's a minor miracle that they make it!

The politics of this series continue to intrigue me. Other than the issues I've already noted with James' characterisation and how he gets away with being kind of terrible, there's also the undercurrent that children being used for spy work is, you know, fine. Again, it is an escapist fantasy for children, so it's not exactly meant to be realistic in that regard. But it disturbs me how much is justified to the CHERUB kids under the banner of 'catching the bad guys'. Every villain in this series so far has been shown as something of a monster. The terrorists from the first book, the drug lord in the second, now the criminal mastermind here. Oh, James feels sympathy for them - he's got that unique perspective of them being the parents of his friends. But the undercurrent is still that the government is justified in everything it does to try and bring them down. Which is a problem when we consider it in the context of justifying police brutality and the underhanded methods of undercover agents. Other kid-spy books of a similar reading age from around the time (I am thinking of Alex Rider) still had the guts to go into how messed up the concept of a child spy is.

Next, Australia's rocky history, as a girl finds herself an unwilling foster family, and a woman is sent far from home.

1 note

·

View note

Text

new post

#rush doors#doors rush#doors roblox#maximum security#prison au#prisoner jumpsuit#prisoner#jumpsuit prison#prison#adriana4ever#my art#mugshot

10 notes

·

View notes