#potts

Text

Tony, looking at a baby monitor: You know... I can never tell if she’s breathing on this thing.

Tony, nonchalant: Is she dead?

Pepper: ...!????!?!

#source: orange is the new black... kinda#pepper potts#potts#pepper#pepper x tony#tony stark#pepperony#stark#avengers#domestic avengers#incorrect avengers#incorrect marvel quotes#incorrect iron man quotes#incorrect mcu#incorrect quotes

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Potts from Florida

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

-✨Shop Update: The new prints are no longer in a separate listing and have been added to the original listing- so you can pick and choose between independant prints or bundles without worrying about extra shipping~ the 8x10 prints are in one listing and the 12 x 16s in another!! Enjoy these lovely shiny darlings!!✨-

#otgw#overthegardenwall#wirt#greg#beatrice#enoch#thebeast#the beast#jason funderberker#potts#pottsfield

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love skullgirls and couldn't make palettes for my favorite characters again

(I know there is a palette of Gum on Squiggles)

#jet set radio#jet set radio fanart#skullgirls#beat#beat jsr#corn#corn jsr#zero beat#zero beat jsrf#yoyo#yoyo jsr#mew#mew jsr#potts#pots jsr#skullgirls valentine#skullgirls ms fortune#skullgirls robo fortune#skullgirls filia#skullgirls annie#crossover#fanart#art

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh, is that who I am now? Well, it was never that far from the surface, mate.

#dwedit#doctor who#usertennant#userteri#usertoph#ninth doctor#tenth doctor#eleventh doctor#twelfth doctor#thirteenth doctor#fourteenth doctor#jack harkness#william shakespeare#martha jones#jacobi!master#simm!master#rory williams#clara oswald#bill potts#yasmin khan#dan lewis#donna noble#best enemies#*#i'm sure there are lots more these are just the ones i could remember <3#emphasis on doctor/master bc well. i'm me#i was going to make a set like this in... feb of last year?#picked out the scenes & had the frames all ready and then i was like. actually that's too much work#so i bailed fjlkdsjls i giffed like three of them individually but that was all#and now a year n a half later here we are.....

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

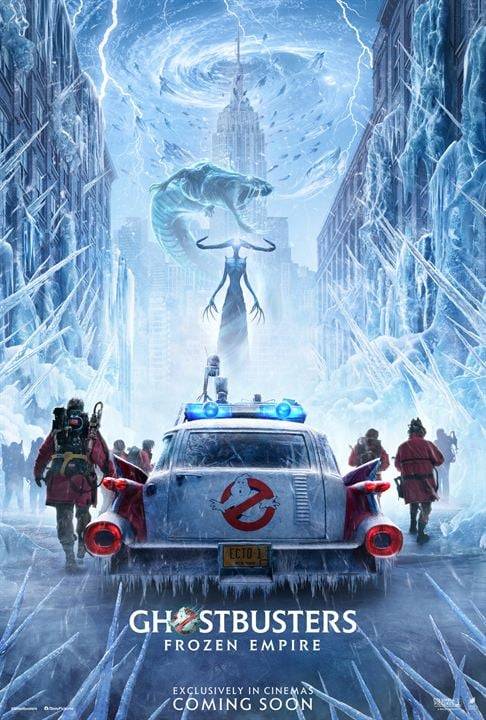

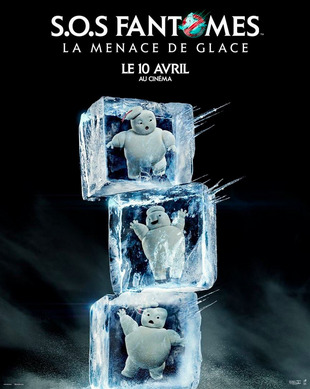

“SOS Fantômes : La Menace de Glace" de Gil Kenan - 5e opus de la série de films “SOS Fantômes” (1984) et suite de “SOS Fantômes : L'Héritage” de Jason Reitman (2021) - avec Paul Rudd, Carrie Coon, Kumail Nanjiani, James Acaster, William Atherton, Patton Oswalt, les jeunes Mckenna Grace, Finn Wolfhard, Logan Kim, Celeste O'Connor, Emily Alyn Lind, et les participations des “Ghostbusters” Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd, Ernie Hudson et Annie Potts, avril 2024.

#films#fairies#Kenan#Reitman#Rudd#Coon#Nanjiani#Acaster#Atherton#Oswalt#Grace#Wolfhard#Kim#OConnor#Lind#Murray#Aykroyd#Hudson#Potts

0 notes

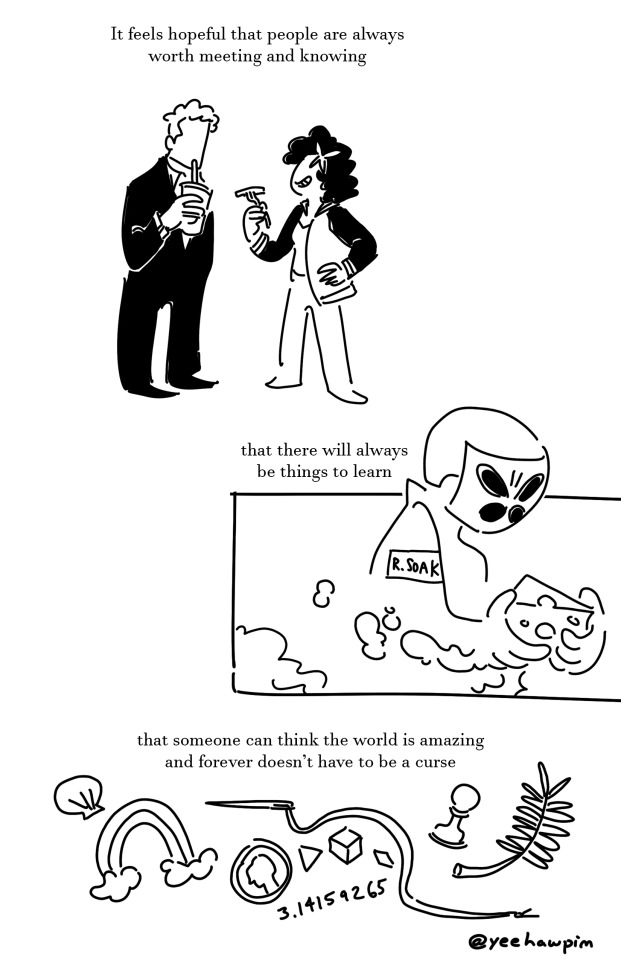

Text

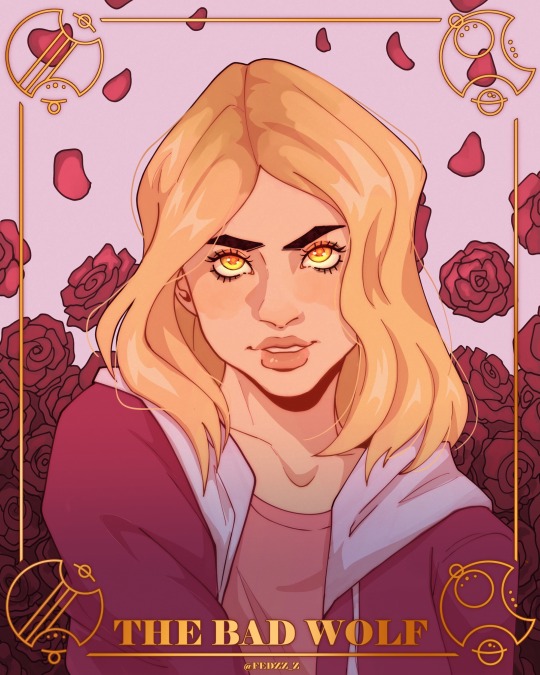

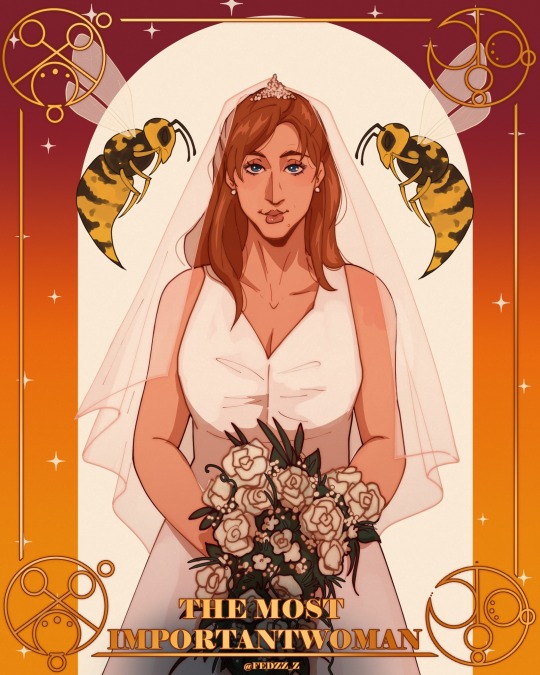

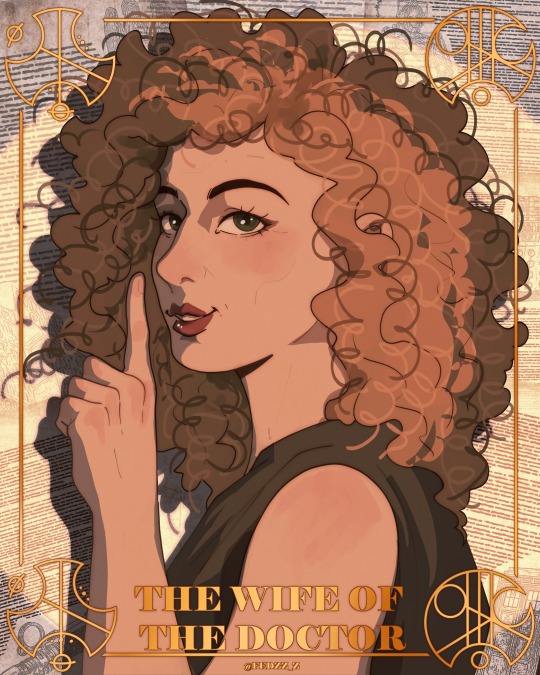

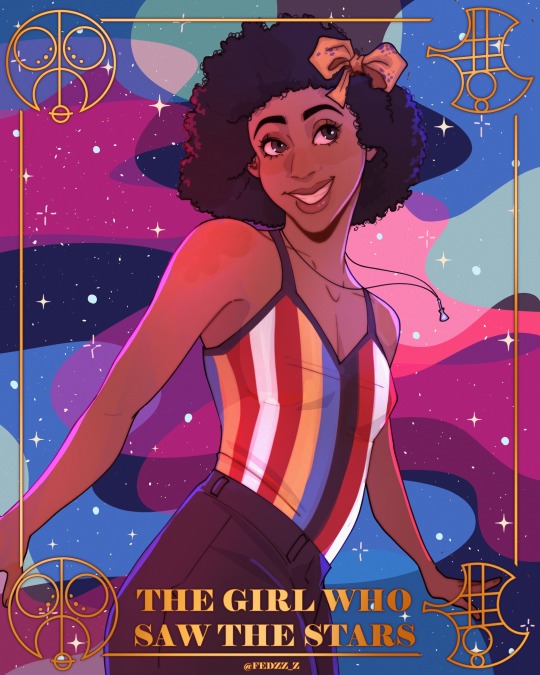

COMPANIONS

aaaaaah looking at them all together is so satisfying!! and i’m so proud of actually finishing this🥰

#doctor who#doctor who fanart#doctor who companions#rose tyler#martha jones#donna noble#amy pond#clara oswald#river song#bill potts#missy#the master#yaz khan

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

Twelfth doctor era of doctor who was incredible because it was basically just:

Clara: I can fix him (makes him worse)

Missy: I can make him worse (accidentally fixes him)

Bill: Well, I'm a lesbian and I'm going to be his friend :)

12K notes

·

View notes

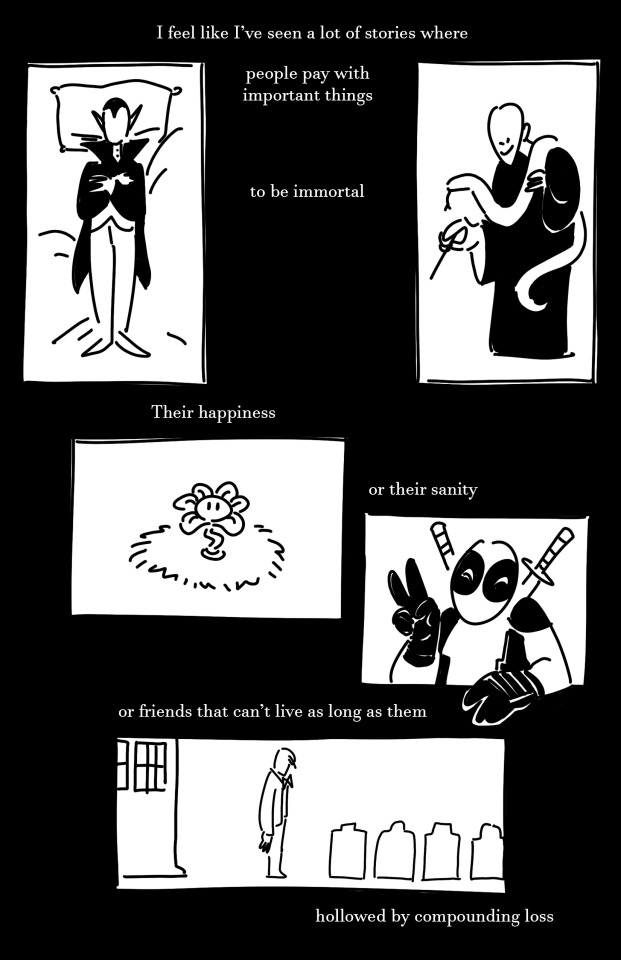

Text

I know some of these characters can be killed but

you get my point lol 😂

#original comic#comic#harry potter#voldemort#tom riddle#asriel dreemurr#flowey#undertale#wade wilson#marvel#deadpool#dr who#11th doctor#good omens#aziraphale#12th doctor#bill potts#discworld#kaos#ronnie soak#my art#my comic

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

Nefarious things are happening on twitter rn

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

Potts from Missouri

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Fall Hullo from Jack Potts

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Few American writers are simultaneously as popular and as unpopular as Cormac McCarthy. Those critical of McCarthy’s work generally form two camps: the more pedestrian, who find McCarthy’s writing simultaneously plotless and repulsive, and the more sophisticated, who believe McCarthy is running some kind of sham, and that all his spiraling descriptions conceal the dark truth that he has nothing to say. I have greater sympathy with one of these camps than with the other, for McCarthy’s plots are often meandering—sometimes even petering out entirely after several hundred pages, as in The Passenger—and the violence, especially in Blood Meridian, The Road, and No Country for Old Men, is gut-wrenching. But the more sophisticated critics, with their suspicions that McCarthy’s voice is merely schtick, are sensing something important about McCarthy’s work, though they interpret it wrongly. They sense that McCarthy is indeed writing about a void, and at the end of the day he truly does have nothing to offer to fill that void.

Does this make McCarthy’s work a waste of time? Only, I believe, if we consider human existence a waste of time. McCarthy is obsessed with the futile offering, the empty gesture, but even as his characters demonstrate the pointlessness of the gift, he himself makes it over and over again: the gift of attending to the world, of looking, of listening, until we become convinced that even if what we attend to is loneliness, if what we look at is collapse, if what we hear is the wind whistling through an abandoned house, our attention becomes a little participation in the death of the world—a participation that, in keeping with the mystery of faith, may become some kind of atonement.

(…)

The first of these themes is certainly the more noticeable in his novels, which are famous for their gruesomeness. McCarthy is not merely interested in evil; he is interested in violent evil, in evil that seeks to rend and skin and rip and gut, evil that wants not merely to annihilate but to dismember slowly, joint by joint, the world.

(…)

Yet there is another theme, quieter yet persistent, that exists alongside—often within—the violence: faith in God. I have chosen those words carefully, because the theme is not God Himself, or His existence or presence, but faith in God. McCarthy does not often ask whether God exists; throughout his many works, that question is generally beyond dispute. Even the atheists, like White in The Sunset Limited, reveal eventually that they do not really disbelieve in God’s existence; it is just that they want nothing to do with Him. “Why can’t you people just accept that some people don’t want to believe in God?” Whether or not McCarthy himself assumes there is a God, his characters do, because the question of whether God exists is not within the scope of language.

(…)

What we can consider, however, is faith in God. Asking if God exists is not the role of the poet or the novelist, according to McCarthy. It may not even be the role of the human. The real question, the question McCarthy’s characters face over and over, is what do you believe about God? For example, in Cities of the Plain, John Grady Cole speaks with a blind man about his intense but conflicted love for the prostitute Magdalena. The blind man urges him to pray, then the dialogue runs as follows:

Will you?

No.

Why not?

I dont know.

You dont believe in Him?

It’s not that.

For McCarthy heroes (and even many villains), it is never “that.” Even the ragman in Suttree won’t deny God. “I always figured they was a God,” he says after getting Suttree to agree to burn his body with gasoline after he dies. “I just never did like him.”

These questioners are Job, not Sartre. It is not a lack of belief in God’s existence; often it is not even a lack of faith in prayer. It is always something else, something connected with the inescapable violence of the world, that draws such a thick veil between us and God that McCarthy’s characters often doubt whether it is worthwhile to seek to draw it back. Looking around at the world, McCarthy concludes it is a fearful thing to imagine the God who made it.

(…)

This section closes with Bobby’s sister Alicia, for whom he harbors an incestuous but unconsummated passion, writing to him in a letter, “God was not interested in our theology but only in our silence.” Horror, McCarthy indicates, is no proof that God does not exist.

(…)

McCarthy’s writing is poetic. By that I mean that many of McCarthy’s sentences do not appear to exist to serve some purpose outside themselves: their language, the texture of the sounds, the relations (often ironic, in his case) between the words and their meanings—all this is the province of poetry.

Specifically, his writing is elegiac. An elegy is a poetic song of something lost or passing away; it is an act of deliberate, careful recording, a close look at what is gone so we can fix its virtues in our mind before time obliterates even the memory of what used to be.

McCarthy is a master of the elegiac sentence, the vivid description that is itself a piling up of themes (in his case, almost always tragic themes), the sentence in which the metonymy or the synecdoche or the metaphor is so perfectly realized that there is no linguistic bridge between what is and what is meant, in which the description is a farewell. As the description of a landscape unfolds across the page, a corresponding description of the human condition, or our situation in the universe, or our muddled relationships with God and each other rises simultaneously in our minds.

(…)

For McCarthy, violence is the signature of God: God, who cannot be seen, who is only indicated by an absence, who no amount of experimenting or observing will reveal, but whose existence is in evidence all around us, every day, through the apocalyptic and apophatic violence that makes up the very stuff of the world.

“Curse God and die,” says the beggar in The Road, quoting Job’s wife from that most bewildering of Old Testament tales. The beggar’s words exemplify one of the possible responses to the intermingling of God and violence, death and the Divine: despair.

(…)

White gives us the best example of an intellectual atheist’s response to suffering in the world, declaring, “The one thing I won’t give up is giving up. I expect that to carry me through,” indicating his determination to commit suicide—to curse God, if you will. But even White does not spend his energy arguing that God does not exist; instead, he insists, “I don’t believe in God. … Can’t you see the sound of the clamor and din of those in torment has to be the sound most pleasing to His ear?” He does not believe in God, not because he has been convinced rationally that God does not exist, but because the world around him indicates that whatever God is, He is not good. His disbelief is a choice, a refusal to associate with a God who, to White’s eyes, is simply violence omnipotent.

(…)

That is no coincidence. Rather, it is the shadow we all live under: it is possible that this is the truth. It is imaginatively possible that God is a sadomasochistic entity whose delight in creation is a perverse delight in creation’s suffering. Even for those of us who have staked everything on a different story, there are things in this world that do not make sense, realities of violence and suffering that we must seek to accept as mysteries, not to understand. Even within Christian doctrine, God has a special affinity for agony. Think of when He asks Abraham to sacrifice his own son; does God’s intercession at the last second atone for the anguish Abraham (and Isaac, presumably) bore? Think of the Flood, when God annihilates the mankind He created, a mankind He will later die to redeem; does God’s later intervention in history somehow balance the scales for what came before?

(…)

McCarthy knows all this. In All the Pretty Horses, Alejandra’s grandmother says to John Grady Cole that in a Spaniard’s heart there is “a deep conviction that nothing can be proven except that it be made to bleed. Virgins, bulls, men. Ultimately God himself.” If this is so, we are all Spaniards; we are all convinced of the deepest truths only by blood.

“This is a thirsty country. The blood of a thousand Christs. Nothing.”

So says an aged Mexican father watching his son bleed out after a pointless barroom brawl in Blood Meridian. This world is endlessly thirsty, McCarthy believes: thirsty for blood and for tales of blood. At one point in The Sunset Limited, Black offers to tell White a “jailhouse story,” a tale of gore and blood and violence such as rightly lives in a Cormac novel, if only White will stay and not go kill himself. It works—for a while. This gives us a clue to McCarthy’s own novels: Could it be that he offers these as his own jailhouse stories, stories from the prison of the world, to keep his readers with him, as it were, to keep them alive?

And within those jailhouse stories, there are glimmers of something else, something from beyond the prison walls. In Cities of the Plain, John Grady Cole says “he believed in God even if he was doubtful of men’s claims to know God’s mind. But that a God unable to forgive was no God at all.” Debussy, the glamorous transsexual in The Passenger, admits to Bobby, “I don’t know who God is or what he is. But I dont believe all this stuff got here by itself. Including me.”

These passages do not necessarily reflect McCarthy’s own beliefs—in fact, I think it is fairly clear that they do not, or at least do not sum up his beliefs. But they exist. They were written, and written clearly and beautifully, without irony, each of them set as a gleaming thorn in the crown McCarthy is weaving, and that tells us something.

(…)

For McCarthy, then, the whole world is Job kneeling in the dust, pleading for God to come and explain Himself, which God will not do. As the book of Job shows, when God does come at last, it is not to explain Himself but simply to be there.

As should be obvious by now, McCarthy’s books, from The Orchard Keeper to Stella Maris, do not offer simple answers to questions of faith. Instead, they weave faith and violence together so closely that, where there is one, we must reckon with the other. McCarthy’s characters blaspheme often; none of them has what I would call a reconciliation with God. Yet still, despite all this, his world is truly God-haunted: haunted by the ghost of God, God the Creator, God the Judge, God the Victim. The Catholic Church, into which McCarthy was baptized, teaches that Christ’s Wounds will never heal. This world can indeed hold the blood of a thousand Christs—and Christ will keep giving it, even unto the end of the age. That is the only ray of light, one that pierces even the bleak world of Cormac McCarthy.”

“Potts remained enthralled for almost two decades. Now, that feeling has gained shape and texture. The Harvard Divinity School professor and Episcopalian priest recently published an academic book about his favorite writer.

“Cormac McCarthy and the Signs of Sacrament: Literature, Theology, and the Moral of Stories,” draws on both postmodern theory and Christian theologies of sacrament to analyze McCarthy’s use of religious images and the moral significance of his stories.

(…)

One of the things McCarthy helps me see is that Christian sacramental tradition raises the question of what it means for the holy to be present in the here and now. Take the Eucharist, for example. There are longstanding and intractable arguments in Christianity over what it means for Jesus Christ to be present at communion. Some say the bread and wine must go away to make room for Jesus, that they only appear to be bread and wine but have actually become body and blood. Others say the bread and wine can only be symbols, because how could God really be present in bread and wine? In either case, however, there is a worry over allowing these ordinary things, bread and wine, to be recognized as holy. I think McCarthy wants to challenge that worry, to ask what holiness without transcendence might look like.

(…)

McCarthy is often interpreted, in popular culture, as agnostic or a nihilist or an atheist, and he might be all of those things. It’s clear that he’s really impatient with institutionalized religion and doesn’t believe in any idea of a sweet hereafter or a great beyond. But I think he does want to insist that even if we can’t hold onto a notion of transcendent goodness, we can hold some notion of goodness in the here and now.

(…)

In an interview, when he’s asked whether he was religious, he said, “I wish I were,” which is interesting. It’s not no, it’s not yes. Michel de Certeau, the Jesuit scholar, said once, “The desire for faith is the same thing as faith.” For McCarthy to say, “I wish I were religious” raises the question whether or not he is. I wouldn’t call him religious or Christian just because I don’t know. I doubt he’d call himself one. But I think he’s useful to Christians and religious people.

(…)

In his books, there are moments when people risk a difficult thing for the sake of love, and even if they may not be rewarded for it, they do it because it’s the right thing to do. I think when he writes such violent things, what’s he’s doing is asking us to think seriously about what the stakes of goodness are. Just because you’re good doesn’t mean the world is going to be good, just because you do the right thing doesn’t mean all is going to be OK. He makes the world not OK precisely in order to ask the question, “Is this still worth doing?”

(…)

Just read him. I think they should read McCarthy and not be put off by the violence. There are many moments in his novels when one might want to stop reading because there is too much violence. I’d encourage people to keep reading. I really do think that McCarthy is trying to ask questions of meaning in a violent world, and if we stop after reading the violent parts without asking the question of meaning, then the violence simply stands. If we keep reading, we may find a way to stand up to it.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

you know bill is fighting for her life in the immortal(ish) queer ex-companion squad

#bill potts#clara oswald#jack harkness#river song#mios#doctor who#dw + text posts#immortal ex companions polycule#500#1k#3k#5k

6K notes

·

View notes

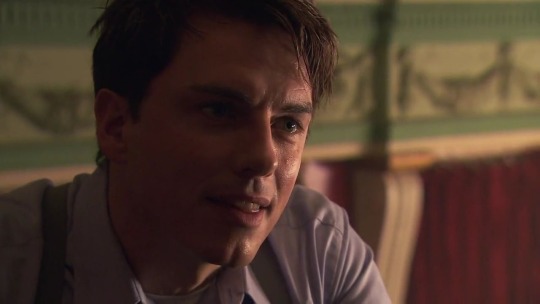

Photo

DOCTOR WHO | The Lie of the Land

#dwedit#dwgif#doctor who#timelordgifs#tvedit#scifiedit#userveronika#userlanie#usersugar#twelfth doctor#bill potts#peter capaldi#pearl mackie#s10#the lie of the land#mine#my gifs#sobbing a bit tbh i miss them

5K notes

·

View notes