#rabbi david hartley mark

Text

Chukat: The Brass Serpent

“The LORD sent fiery serpents against the Israelite People [for the sin of doubting Moses]. They bit the people, many of whom died. The people came to Moses and begged him to help them, by interceding with God. The Lord said to Moses,‘Make a fiery serpent—Seraph of brass, and mount it on a standard. If anyone is bitten looks upon it, they shall recover.’ Moses did so, and the people were healed.”

--Numbers 21: 6-9

I am Nechushtan, the Brass Serpent, Healer of the Israelites from the plague they brought down upon themselves. How dared they to doubt the leadership of Moses, as well as complain about the manna, the bread from heaven? Well, God told Moses to construct me, and I healed them from the fiery bites of the serpent-plague.

And yet, I daresay that you have never heard of me, nor ever seen my like before! For a God Who forbade the practice of idolatry, is it not strange that He authorized the building of an idol—myself? Yes, yes, I hear you say; the purpose of Nechushtan was not to be an object of worship; it was to be a source of healing, albeit a dramatic one. How long do I appear in the text of the Torah? For five verses only—that is a short episode, indeed.

Never forget that Torah is not like your post-Modernist literature. A character or object may appear for just a few verses, and then vanish just as quickly. I, Nechushtan, do reappear later in the text—not the Torah’s, but in Prophets, during the reign of the reformist King Hezekiah:

“Hezekiah abolished and destroyed all forms of idolatry. He broke into pieces the brass serpent that Moses had made, for the Israelites had been making offerings to it; it was called Nechushtan.”

--II Kings 18:4

So, clearly, despite my long absence from the text, I still managed to influence Israelite worship—or, at least, idolatry. What is the lesson?

It is in the nature of you human beings to collect and venerate objects you deem sacred, blessed, or just lucky. Whether or not the plague of the fiery serpents actually occurred, whether Moses constructed me, only to have Hezekiah destroy me, centuries later—I served my purpose. I gave some mystical quality to the text—how many times can one read of the Israelites angering their short-tempered Deity, and His punishing them? Instead, I began a body of legend that still persists, today. All glory to me, Nechushtan, the Brass Serpent!

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#torah study#drash#parsha#weekly parsha#chukat#hukath#chukkas#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbos#shabbat#sabbath#oneshul#shabbat shalom

26 notes

·

View notes

Link

Mephiboshet; or The Little Lame Prince Adapted by Rabbi David Hartley Mark While Saul’s son Jonathan lived, he and...

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eikev: Joshua Rebukes Moses

I am Joshua ben Nun; orphaned in Egypt—my parents perished while building the pyramids that dotted the Valley of the Kings. It was Jochebed, mother of Moses, who took me in, may she rest in peace. I recall being a small child, when Moses was already a teenager—Jochebed often took me to the Pharaoh’s Palace to visit him. I thought of him as a mix of an older brother and a kindly uncle. I wept when she told me Moses that had fled from Egypt, fearful of the punishment that would follow his having killed a slave driver.

Moses has been my mentor and guide for all these years in the Wilderness; I was fortunate to be with him when he climbed Mt. Sinai, there to commune with the Almighty and receive the Ten Commandments. I did not join him on the mountaintop; I hid amid the boulders along the path. There, I witnessed the battle between Moses and the Angels who did not wish to relinquish the Torah, until God intervened.

The Generation of the Exodus is gone; now, he and I lead the Generation of the Wilderness. I was happy to hear that My Lord Moses wished to teach Torah to these youngsters. He and I had had such high hopes for them! After all, they were not tainted by the slavery experience; they had been nurtured in freedom, under God’s protection, who fed them with manna, and so much more. Unfortunately, it is not unusual for headstrong young people to spurn their elders’ instruction, and these Israelites had not hesitated to participate in the riotous orgy brought on the Midianites and their god, Baal Peor. Sadly, many of them paid for their sins with their lives.

Nonetheless, could there not be a time for reconciliation? I looked forward eagerly to Moses’s Torah lecture; surely he would find a way to make peace between the people and their somewhat testy deity. Was He not a God full of mercy and compassion, extending forgiveness to the thousandth generation? Instead, Moses lectured them about their backsliding:

“If you do forget the LORD your GOD and follow other gods to serve them... I warn you this day that you shall certainly perish... because you did not heed the Lord your God.”

--Deut. 8:19-20

And that was not all: Moses recounted all of their sins for them, and laid it on very thick. It disturbed and frightened me.

When Moses was done with his teaching, bitter as it was, I gave him my strong right arm on which to lean, as I escorted him to his tent.

“What think you of my address to the people, hey Joshua?” Moses asked me.

“May I speak frankly, My Lord?” I answered. When he nodded, I responded to him quickly and precisely: “It seems to me, Rabbi Moses, that you might have sweetened your words a little. When I behold this people, the work of God’s hands, I consider that they are unlettered, unsophisticated—have they not been living in the wilderness for all of their lives? Since their parents perished in this great and savage desert, they have no one except you, Sir, to teach them the proper way for Jews to live.”

Moses stopped walking, and looked directly at me: I swear, it was as though he could see straight into my heart and soul.

“You are right, my disciple, to question me; never fear—I am not angry. Yes, you are right; I did speak harshly with the people. But life is very hard, and one must be steeled to difficulties in order to overcome them. Hear me, Young Joshua: in days to come, there will be many Jews who behave un-Jewishly, who cheat and lie and forget their heritage. My duty is to warn them of the consequences. And those who heed me will understand how to act.”

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbos#shabbat#sabbath#torah study#ekev#eikev#deuteronomy#oneshul#shabbat shalom

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vaetchanan: God and Moses

Scene: a windswept mountaintop, named Pisgah. Tumbleweeds fly about in the strong wind; autumn is coming. A thin, tired-looking man with a long grey-white beard, our Moses, is struggling to attain the heights. He finally succeeds, panting; he takes a deep breath, sips from his leathern water-flask, and stands, waiting. And waiting.

Moses: Lord God? It is I, your humblest servant, Moses. Will it please You to speak to me.

The lightning cracks and the thunder rolls, but there is no answer.

Moses (sighs): Lord God, it is not like I don’t have things to do. I am the only one commanded to ascend and speak with You. I have no time; I must go down to judge the people’s litigations. They are stubborn and stiff-necked; I had thought that this Generation of the Wilderness would be more—pliable, but I was wrong. They are as sinful and full of pride as their departed ancestors, who perished at—at Baal Peor, or the Golden Calf, or Korach’s Rebellion—I would rather speak to you of their successes, but cannot recall any.

The Voice of God: I am here, Moses. Where are your judges of tens, judges of twenties, and so on? Did you not remind the Israelites of your appointing them, just a short time ago?

Moses: My judges—pah! A bunch of self-centered good-for-nothings—You killed them (as they rightly deserved) for taking part in the People’s various orgies. And only am I escaped to tell You, and afterwards judge the saving remnant of my people.

God: Shall I send lightning-bolts to fry these rebels, Moses? Let me prepare them—

Moses: No, Lord God, no. I can handle them, and Joshua, my successor, will be able to deal with them, too. I only beg You to deal with them in compassion. Yes, they have faults enough, but who else will be Your treasured nation, and the apple of Your eye, if not them? You chose them long ago; yes, when you ordered Abram and Sarai, “Get thee out of Haran, you and your household, and go to a land of which I will tell you.” That covenant must stand.

God: Thank you for reminding Me. I had not forgotten, but I have a great deal to remember, what with plagues in Egypt, volcanic eruptions in Santorini, and answering the prayers of the natives in North America....

Moses: Where is that?

God (hastily): Never mind. There. So. What is your next step?

Moses: I know, Dear Lord, that You have ordered me not to enter the Land; I will die on this side Jordan. I am reconciled, but it is hard, so hard, Lord....

God: Take heart, My Servant. I will let you down easy. Your passing will be like a hair removed from a cup of milk. But you have a great deal more to do, before you go to be with Me, forever.

Moses: And what is that?

God: Tell My people that the penalty for backsliding and idolatry will be exile. If they sin, I will scatter them among the nations. Tell them that, when they look into their hearts and examine their souls, they will know that I will not abandon them forever. It may be hard for mortals to comprehend, but I am compassionate at the core: I will not forsake them, but will be with them in the countries where they come. Tell them that, Rabbi Moses. Teach them....

Clouds settle over the mountaintop, obscuring Moses from view

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbos#shabbat#sabbath#torah study#va'etchanan#vaetchanan#deuteronomy#oneshul#shabbat shalom

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Balak: A Misunderstood King

When people read the Story of Balaam, they always focus on the Talking Donkey. I can’t understand why. The Torah Portion is named after me, King Balak of Moab, and, after all, talking donkeys are nothing unusual. I daresay, Reader, that you may have heard one or two, or several, mainly in politics, which we had in my day, as well, albeit in a minor, less dangerous form. And the fact is that the Donkey showed a great deal more intelligence than either its rider, hapless Balaam, or my several messengers, who keep returning to Balaam and offer him riches, only to be refused. The story reads like a fairytale, which it well might have been.

Let us examine the facts of the tale, eliminating Balaam—yes, yes, I know that he composed a few lines of poetry—quite a few, in fact—but only a smallish fragment made it into your prayerbook:

How goodly are your tents, O Jacob,

Your dwelling-places, O Israel!

Is that it? Is that all? I suppose that it’s a big deal when a pagan prophet’s verse makes it into an ethically monotheistic people’s prayerbook.

When I read it, I asked Balaam, “Why are you praising this pesky bunch of nomadic interlopers?”

“The God of Israel touched my heart,” he replied, getting all moony, “and I was inspired to write poetry on His behalf.”

“Not a great deal of poetry,” I huffed, “and after all, I was the one who hired you.”

“Are you going to pay me, Majesty?” he asked.

Can you imagine—he still believed that I was going to pay him for the non-curse which he did not deliver to the Israelites. The nerve of him!

Dear Reader, I hope that you will listen while I make my case. The fact is that Israel and Moab are related—we were originally produced by that—um—unfortunate liaison between Lot and his daughter. About that I can only say, “The less said, best said.”

Furthermore, Bible scholars, who know a great deal more about these things than I do, believe that the relationship between Moab and Israel was mixed—you either accepted us as neighbors, or you warred against us, often for most confusing reasons. I cannot figure out the points in our mutual history where you oppressed us, especially when we were living in peace. I hired Balaam in the first place because my god, Chemosh, ordered me to curse the Israelites. I think. How can one converse with a god of stone? And didn’t your God inform you not to take advantage of or destroy the weak?

When all is said and done, however, remember that the Torah Portion is named after me—not that foolish, greedy prophet; not the angel (though that would have been nice; I like angels), and certainly not the donkey. It is named after me, and why? Because, in my misguided attempt to curse Israel, I contributed to their legend—that of an unstoppable, eternal people. It’s not as though they will always be right, however. I can only pray to their God that they not oppress other nations.

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbat#shabbos#sabbath#torah study#balak#oneshul#shabbat shalom

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pinchas: A Daughter of Tselophechad Stands Up for Her Rights

The daughters of Tselophechad, of the Tribe of Menashe...came forward to Moses for judgment, regarding property they had inherited from their father. Their names were Machla, Noa, Chogla, Milka, and Tirza. ...They said, “Our father died in the wilderness. ...He has left no sons. Let us inherit his property!” And Moses brought their case before the LORD.

--Numbers 27:1-5

I am Milka, next-to-the-youngest of our father Tselophechad. In the Torah Rabbi Moses wrote—or dictated by God’s command—that we, though being mere women, should inherit our father Tselophechad’s property. It was then, and still is, a milestone in Jewish legislation that a woman should inherit property. However, in the end, all my sisters except me married our cousins, also Menashites. This kept the property in our little tribe, that of Menashe, son of Joseph, who rescued Pharaoh and the Kingdom of Egypt from famine. It is hard to remember Joseph fondly, because, by bringing our ancestors down to Egypt, he also condemned them to the fate of slavery: a four-hundred-year sentence.

But that is all behind us, now; the Holy Land awaits our conquest, and I am eager to participate. Nonetheless, I refuse to submit to the judgment of Moses and his God; I wish to hold on to my paltry share of Papa’s property, alone.

Before he died, Papa took each of us alone into his bed-chamber. When it was my turn, he told me: “You, Milka, despite being neither firstborn nor last-born, have always been my favorite,” he said, his voice made weak by the illness that killed him—and where was God then, to rescue a man about whom no one could any ill?

“I wish for you to retain this small bit of property that I leave you.” And he presented me with a silver ring, with a red stone in it. Is it a ruby or garnet? It does not matter: it was a gift from my Papa, who chose me to be his favorite. I am content.

So, when we went before the great Moses—how thin he was, and how frail! It is hard to believe that the Word of Almighty God could reside in such a skinny body—bossy Machla, my eldest sister, spoke for all of us, as she always does. I kept my peace. I knew I was the favorite; Papa had told me so.

The days and moons have passed; my sisters have married our cousins, and I wish them well in their choices. I cannot say that any of my new brothers-in-law impress me; they prefer not to work, instead spending their days guzzling beer in the tavern, and bothering Uncle Emir for pocket money.

For myself, I have chosen to live my life with my lovely girl companion, Ahava bat Emet, who has been my friend for all of our lives together, since we met years ago in the little children’s Torah class. I love when she looks at me—her eyes are golden-brown, like the soil of Canaan which we will enter shortly, like the sun when it sets over the wildnerness. We take long walks, and talk for hours. I much prefer her company and her love over that of any man—and no one need know. Why, what business is it of theirs?

When Moses dies and Joshua takes over, our citizen-troops will win us a holding in the New Land, Ahava and I will build a small house, on the outskirts of Menashe’s tribal portion. We will spin and dye wool together to sell in the marketplace. When the day grows cool, I will take my beloved’s hand, and we will walk through the country which God has gifted to us.

When we grow old and our time comes to depart this life, we will be buried, side by side. Our love will never die.

Bloom forever, O Israel, from the dust of my bosom!

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbat#shabbos#sabbath#torah study#pinchas#oneshul#shabbat shalom

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Devarim: Meet the Deuteronomist

We enter the dog days of summer: the sun burns fiercely; our forays outdoors are humid and steaming. And we prepare for Tisha B’Av, the Ninth Day of the Month of Av, the most tragic day in the Jewish calendar. This Shabbat, we begin our reading and study of the fifth book of the Pentateuch/Chumash: Sefer Devarim, the Book of Deuteronomy.

As a child, my Orthodox rabbis taught me that the Torah—that is, the Five Books—were written in a complete unit by Moshe Rabbeinu, Moses our Rabbi. At this point in the overall narrative, he seems to have gained a renewed strength, both in body and purpose: to educate the Dor HaMidbar, the Wilderness Generation—those Israelites with no personal memory of Egyptian slavery or the Sinai Theophany. He does so by recounting the entire Wilderness History of our nation, beginning with this, our parsha.

Moses’s central theme is the urgency of obedience to God, lest Israel risk His wrath and punishment. The only assurance is to remain eternally faithful. Moses recounts his appointment of judges of thousands, of hundreds, fifties, and tens—oddly enough, he seems to have forgotten how Jethro, his Midianite father-in-law, assisted him in establishing the roots of Jewish jurisprudence. But then, Jethro’s tribal status would perhaps not make him worth remembering, in light of the Israelites’ struggles with Midian in the previous parsha.

All of this discourse and exhortation occurs in a way station of “that great and terrible wilderness” (Deut. 1:19). It must have been awe-inspiring: the assembled multitudes of Israel, all young, idealistic, eager to cross the Jordan and attack their Canaanite foes. Indeed, this same indoctrinating style persists throughout the entire Book of Deuteronomy, but it does not stop there: it continues into Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings, as well as parts of the Book of Jeremiah. It is, indeed, a deep and long-winded discourse by Moses, in a windswept, sun-baked plain of the Sinai Peninsula, the Aravah. Highly dramatic, too—except that it never happened.

Modern Biblical scholars hold, for the most part, that an anonymous scholar (or school of scholars) whom they label the Deuteronomist, wrote the above works. He emerged following the destruction of Israel, the Northern Kingdom, by Assyria in 721 BCE. Jewish refugees of the catastrophe, as tragic and infamous in its day as the Holocaust to us, came to the Southern Kingdom of Judah for refuge. They brought with them a strong need for our people to survive, along with a bedrock belief in the concept of Adonai as the only God to be served. This was news to the sinful people of Judah, engrossed in idolatry.

The movers and shakers in Judean society were the aristocrats who owned land, and who furnished the governmental administrators in the capital of Jerusalem. Skimming over that era’s history of regicide (King Amon, 640 BCE) and the aristocrats’ placing his then eight-year-old son Josiah on the throne, as well as Assyria’s downfall and its replacement by harsh and ruthless Babylonia, we encounter the signal tragedy which we mourn, the Destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE.

All of these court intrigues and external pressures weighed on the consciences of our ancestors: if God loved Israel so, why was He allowing their destruction and suffering? Here is where the Deuteronomist emerged, with a simple but weighty reason and solution: God had decided to punish His people for their many sins of ignoring Him, oppressing the poor and the Stranger, and neglecting the Temple for idol worship.

Given that the overwhelming weight of Jewish History is tragic, it was heartening when Babylonia fell and the Persian Empire under Cyrus allowed the Israelites, along with other captive peoples, to return to their homelands (539 BCE). From there to us post-modern Jews of today, with our streaming services and virtual Judaism, seems a breath of fresh air.

Following the fateful Ninth of Av, we enter the High Holy Day season, time for the strongest and largest temple attendance of the year. We look around at one another and note that we have survived an old year with its calamities, to welcome a new year with its blessings.

Never forget to thank the Deuteronomist, who worked so hard to ensure our faith and our survival. And, see you in temple this Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur!

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbat#shabbos#sabbath#torah study#devarim#deuteronomy#oneshul#shabbat shalom

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

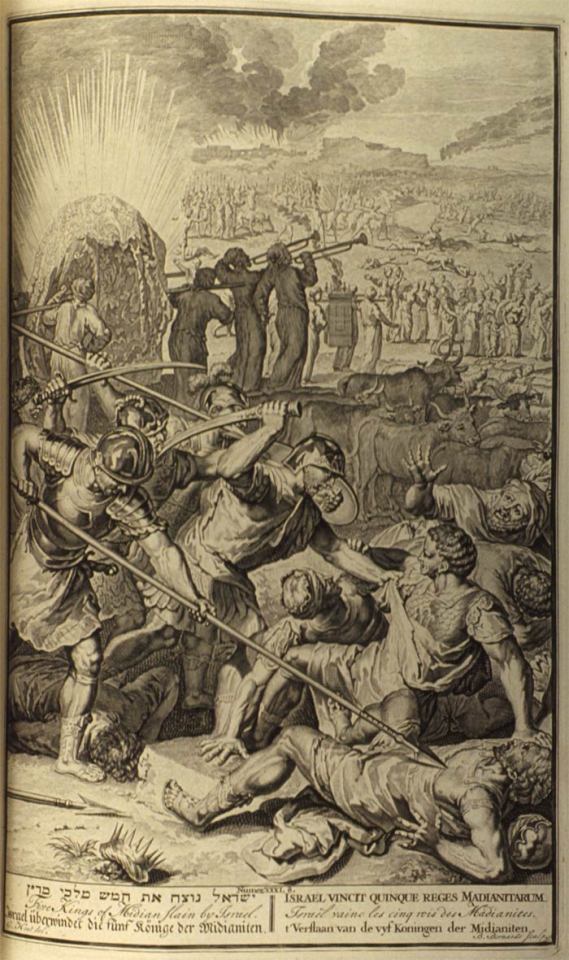

Mattot-Masay: The Midianite Tragedy, and Us

The LORD spoke to Moses, saying, “Avenge the Israelite people on the Midianites.” Moses spoke to the people, saying, “Let men fall upon Midian to wreak the Lord’s vengeance.” [The Israelite warriors] fell upon Midian, and slew every male, including male children, and [afterwards] slew every married woman. And they took much booty, for the priests and the Lord.

--Num. 31:1-18 (adapted)

There are many scapegoats for our sins, but the most popular one is Providence.

--Mark Twain, 1898

Why is this portion of Torah so war-mongering, and so bloody? Rabbi Michael Lerner, Ph.D, writes of “A Torah of Love and a Torah of Hate,” and this is clearly an example of the latter.

Who wrote the Torah? Why, Moses, clearly and without a doubt. This was, and is, the Traditional viewpoint, embraced today by only the Orthodox. Perhaps, however, the Documentary Hypothesis has crept in among them, as well: I recall participating in the very first class on Scientific Bible Criticism to ever be taught at Yeshiva University, my long-ago alma mater. According to this school of thought, it was a Kohen, a Priest, who wrote the Book of Numbers, which we are shortly concluding. Scholars call him P, for obvious reasons.

There were other authors, listed in many a book of Biblical scholarship: J, E, D, and others. Each had a particular style and language. There was also P.

The question, according to James Kugel, Ph.D, in his How to Read the Bible (2007, pp. 299-306), is, when did P live? Dr. Kugel, of Harvard University and currently Emeritus at Bar-Ilan University (and who identifies as Orthodox), explains that the older scholarly opinion was that P was post-exilic. P was well aware of the Destruction of the First Temple, and the Israelites’ being kidnapped to Babylonia.

Following Babylon’s defeat by the Persians, the victors allowed the Israelites to return to Israel. Significantly, most of them did not. Think of the paltry number of American Jews who moved to Israel following its independence; American fleshpots were more tempting than a Spartanlike kibbutz. More recently, it is believed by several of them that P actually lived in the pre-exilic period, when the tiny kingdom of Judah was threatened, both within and without.

Against these sad and tragic backgrounds, P, possibly a Priest without a temple, wrote the Book of Numbers. Which returns to my central question: why is Mattot-Massay so bloody? Why the massacres of Midianite prisoners, and the acts of looting, all on the tired excuse that Midian and Peor enticed the people to idolatry? I cannot excuse the violence, but I believe that P was trying to harken back to a period when his nation was powerful, rather than refugees at the hands of Babylon and Persia. It is inexcusable, by our modern standards, that the bloody tales of these Torah portions were inflated and aggrandized. Well, yes: but please note that various nations, the US chief among them, possess sufficient nuclear missiles to annihilate humanity more than five times over. Note also that our nation is top among arms merchants to the world; in various Third World countries, a submachine gun is cheaper than a loaf of bread.

In the end, what remains? I hold with Rabbi Lerner’s comment: our Book contains both love and hatred. It is left to us to comprehend the difference, and, in spite of our tragic past, endeavor to work for a peaceful humankind.

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbat#shabbos#sabbath#torah study#matot-masei#mattot-massay#oneshul#shabbat shalom

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Schlach: And the land had rest for forty years....

The LORD spoke to Moses, saying, “Send men to spy out the Land of Canaan, which I am giving to the Israelite people; send one man from each of the ancestral tribes, each one a prince of his tribe. So Moses sent them out from the Wilderness of Paran....”

--Num. 13:1-3

As I recall it—though it happened only last month, it feels like a year ago—Moses did not ask whether we wished to cross the Jordan River—more like a rivulet, actually; one of us, Gaddiel ben Sodi, was a tall, strapping fellow, and he was able to straddle the river from side to side. “Mighty Jordan,” indeed! Well, from that inauspicious beginning of our spy mission, things got only worse.

My name? Oh, since you asked—I am Shammua ben Zacur, of the Tribe of Reuven. Yes, that tribe. Our forebear’s reputation was never sterling, especially after he seduced his own aunt, Bilhah, in a failed attempt to gain control of the tribes after Jacob’s death. Jacob was then very much alive, and, angry against his eldest son, he banished Reuven for a time.

But I digress: what of our mission? It did not begin well. We were hungry; Moses had virtually chased us out of the camp, so eager was he to fulfill the Lord’s prophecy of conquest. And so, when we discovered a field of berry-bushes, we fell upon them with a will. That was foolish, and dangerous: we all suffered from a griping of the guts soon after—the berries were not for human consumption; we later on saw wild pigs and kites scarfing them down, while we lay in hiding from the Canaanites. We all groaned from our stomachs—Geuel ben Machi, of the Tribe of Gad, cried out so loudly with pain, that we threatened to leave him there.

Moses had enjoined upon us the task of seeing whether the Canaanites lived in open or in walled cities, but, I admit, we feared to go near, and so could only estimate the size of their castle-dwellings. We later reported to him that it would take our entire military strength to conquer such thickly-walled bastions as Jericho and Ai—it turns out that the walls were three feet thick! Our rabbi-leader—he was then old and weak— just looked down at the ground, disappointed, and mumbled something like, “The Lord will protect His People; the Lord will bless His people with peace.”

Well, you know what you can do with such prayers—give me a sword and shield any day, and I will formulate some scheme to make the inhabitants open their gates of stone and pursue my platoon, while our other infantry race inside and set the grain-stocks afire. Stampede the donkeys, slay their fighters, and kidnap the women and children—yes, that will win us the city, more quickly and efficiently than prayers to the Lord.

Mind you, I was not one of the croakers who told the people of imaginary giants or city-walls reaching up to the heavens. It is true that the Amalekites dwelt in the Negev Desert. Grr—they are a shifty, treacherous people—I yearn to eradicate them from the face of the earth! But that never happened. They are here to this day, a constant thorn in our side.

Caleb, bless him, took my part—he believed with all his heart, and, with help from God, that we could conquer the land. But, you know what happened in the end? Rather than storming across the Jordan and battering the walled cities to dust, we instead filtered across slowly, slowly—so that, one day, the locals looked out their windows and doors and saw us there, settling in. That was when they fled: their own prejudice and hatred of us Israelites drove them away.

And the land had rest for forty years....

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#torah study#drash#parsha#weekly parsha#shlach#shelach#sh'lah#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbat#shabbos#sabbath#oneshul#shabbat shalom

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reeh: A Blessing and A Curse

“See, I give before you this day a blessing and a curse. The blessing, that you will listen to the Commandments of the Lord your God, which I command you this day. And the curse, if you will not listen to the Commandments of the Lord your God, and you turn from the Way which I command you this day, to follow other gods, which you have not known” (Deut. 11:26-28, translation mine).

The Sefat Emet (Pen name, “The Tongue of Truth,” of the Chasidic Rabbi Yehudah Leib Alter of Ger, 1847-1905), in commenting on these verses, states that “[In] the blessing it says, ‘that you listen,’ but in the curse it says ‘if.’ Goodness exists within the Jewish people by their very nature; sin is only incidental. …Even if there is some sin—and indeed ‘there is no one so righteous as to do good and never sin’ (Eccles. 7:20)—it is only passing” (Green, 1998, pp. 302-3).

Rabbi Arthur Green, from whose masterful The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of the Sefat Emet, Rabbi Yehudah Leib Alter of Ger (Phila., PA: JPS, 1998), the above is taken, universalizes the above reference by stating that, although only we Israelites can claim the Covenant dating from Mt. Sinai, all of Humanity “must contain that essential goodness.” In other words, all mortal beings who profess to follow a moral code have a share in the above statement. The veneer of civilization is very thin, and it is easy for immoral leaders and followers to destroy it. Humanity must work all the harder to preserve our world.

As a species, we are more divided than ever before. Yet we all share the same drives for survival, happiness, success in life, and safety for ourselves and our loved ones. Rather than reinforcing what divides us, we must seek what we hold in common as human beings: feelings, dreams, and aspirations.

At the time that Moses gave the above speech, he was mortally concerned that the Lord’s people were entering a society in which they would be a minority. As free men and women, nomadic in heritage, able to make their own decisions about where to live and whom to marry, they might swiftly assimilate among the more settled, agricultural peoples of Canaan, and, within a few generations, vanish as a unique people. Ironically, this remains a major concern for us Jews, thousands of years later—still separate, still asking the same questions.

As Jews, we are proud of our tribal, religious, cultural, and nationalistic differences, but, as human beings, we must always aim towards a common goal. As we aspire to political freedom, so must we work to understand similar political yearnings in others, provided that the debate is peaceful. The Golden Rule which we gave the World must guide the steps of all right-thinking humanity: if we cannot love all of our neighbors, let us, at least, respect them, and insure that we receive that same respect—neither as victors or victims, but as equals.

There is an old story about a woman—call her Ms. Richter—who invites her rabbi to visit her home, serving him a cup of tea on her best china, while they sit in the sun room which faces the back yard. Making small talk, the rabbi notices the fence separating the woman’s yard from her neighbor’s, Ms. Jones; he remarks about the freshly-washed sheets and clothing Ms. Jones has hung in the yard, and asks if they are friendly with one another.

“That woman?” scoffs Ms. Richter, “I wouldn’t give you the time of day with her. Why, look at the laundry she hangs out there, on her line. It’s filthy!”

The rabbi gets up, walks to the window, runs his finger along it, and replies, gently,

“Ms. Richter, there is nothing wrong with your neighbor’s laundry. I’m sorry to tell you that the problem is your windows: they’re dirty.”

When we look at the faults of other people, other nations, are we so quick to judge their shortcomings, or should we take the trouble to look beneath the headlines, beyond the shrill cries of their politicians, and see that, beneath the “dirt” which separates us, they are, perhaps, just people—not far different from ourselves, hoping for a Better Tomorrow for themselves and their children? Or are we satisfied with simply looking at them through a dirty window of stereotyping? It’s not easy: we are, after all, all human beings, not Angels—but God gave the Torah to us. What are we to do with it?

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#parsha#weekly parsha#drash#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbos#shabbat#sabbath#torah study#re'eh#reeh#deuteronomy#oneshul#shabbat shalom

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pesach Day 1

Scene: Land of Goshen, the Israelite Neighborhood of Egypt. Moses is examining every dwelling to make certain that all is in keeping with the LORD’s commands. He is accompanied by one Lieutenant Djer, of the Royal Egyptian Cavalry, “Vision of Ibis” Regiment, Commanding. Moses is hale and hearty, eager to fulfill the Lord’s dicta, in order to free the People from 400 years of Egyptian Slavery. Lt. Djer is there to observe, and later report to his generals, that the Hebrews were behaving themselves.

Moses: I cry you all to gather, O Elders of Israel! Come unto me, and hearken to the Word of the Lord!

Lt. Djer: Why do you not sound a sennet on ceremonial or military horns? That is how we do it in the cavalry.

Moses: We favor the Old Ways, Lieutenant. Gather, gather unto me, all ye Elders!

Djer: Hm. It does appear to be irregular and inefficient. It surely wouldn’t be acceptable to our cavalry.

Moses (sardonically): I believe that our God has plans for your cavalry, Lieutenant.

Djer: Plans? What plans? Whatever are you talking about, Moses? By the rays of Ra, ever since you denounced your Egyptian identity and became an Israelite peasant, it’s almost impossible to carry on a simple conversation with you.

(Meanwhile, the Elders have come, and form acircle around Moses and Djer.)

Eldad, a Senior Elder: We are here at your command, O Moses! Tell us what to do.

Moses: Let each family kill a Passover Lamb.Take a bunch of hyssop, dip it into the lamb’s-blood, and smear the blood over the door, lintel, and the two mezuzote, the side-posts of every Israelite dwelling’s door (Drops his voice so that the Egyptian Djer will not hear). For the Lord will pass over the Israelite houses, and smite only the Egyptians, or those so foolish as not to have smeared the blood, before the Plague arrives. Simple enough, hey? And the Lord will work for you all yet another miracle, for you are His People, the apple of His eye!

Medad, Eldad’s Brother: Um—Moses—

Moses: What’s that? Can you not follow such easy instructions?

Medad: Well, you see, it’s just that—well, we’re vegetarians. We don’t eat meat. Fact is, my little ones get nauseous if they even smell roasted meat. Is there, perhaps, some way to work around the Paschal Sacrifice?

Moses: This is a conundrum. Can you not borrow blood from a neighbor, or your brother Eldad?

(The Elders mutter among themselves: “Well, what nerve! How dare that Medad rebel against the works of the Most High!” And another: “I don’t agree. My wife and I have been thinking about going vegetarian for some time. Perhaps now is the time, given by God.”)

Moses: Medad, Elder of Israel! How do you propose to fulfill this most sacred commandment, given to you by God?

Medad: Well, my wife Sophonisba and I were talking, and we propose using a beet. It’s red; it has juice, and it will color the door nicely, if we mix it with a bit of matzo meal.

Djer: Moses! Why do you not strike down this rebel? Only by obedience can you hope to create a people. Here: you may borrow my sword. Kill this Medad now!

Moses: No, Lieutenant, that is not the way we do things among our people. We debate, and argue, even to the point of anger. But we always part as friends.

Djer: I cannot abide such milquetoast behavior! I must leave. This is all going into my report (He exits).

Moses (to Medad): Tell me again about your Beet Proposal. Perhaps we can save the lives of many lambs this first year.

(Medad nods happily at having his proposal accepted. Other Elders mutter beneath their breath: “God will never settle for a vegetable over good, honest meat!” “Oh, I’m not so sure of that—for God is compassionate, is He not?”)

Moses: Silence! And now, go ye forth and execute the Word of the Living God. Tell all the People that you see, and let them smear a beet, or slaughter a lamb!

(Exit the Elders.)

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#torah study#drash#pesach#passover#parsha#weekly parsha#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbos#shabbat#sabbath#oneshul

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bamidbar: Into the Wilderness

(Enter Moses into the Wilderness outside the Israelite camp, alone. He looks fatigued and worn-out; suddenly, his legs buckle, and he slumps to the ground. He looks up to the Heavens in an accusing manner.)

Dear God, can you not ease my burden of this People? It is not enough that they are always quarrelling—Issachar, Zebulun, and Reuben conjoin to gang up on Judah. I know through prophecy tells me that they will be the leading tribe in the future, though I certainly will never live to see it.

(He cocks his head, as if listening to a Heavenly Echo, a Whisper of Prophecy.)

Yes, yes, I know Your future plans for this People: that they will become mighty in the region, but then, alas! They will go down to conquest, fire and ruin. Today, meanwhile, it pains me that You commanded me to take a census; You know that no good ever follows a census—why? That is Your affair, not mine—apparently, You too follow the old superstition that no one should ever know exactly how much they possess, whether money, land, or people. Approximations must serve, to fend off evil.

And there are other flashpoints which I must disarm, Lord, with or without Your help. When we spoke on Mt. Sinai, You commanded me to appoint the firstborn of each tribe to serve You in the Mishkan-Sanctuary. That was difficult enough to enforce—most of the People know full well that You prefer the last-born—as I am; as were Isaac and Jacob. Thank You for agreeing with me—we do not always see eye to eye, You and I.

But Your decision to cast the firstborn aside from Your service in favor of the Levites, my own tribe—that was difficult for the firstborn to reconcile. They willingly accepted the blame for the sin of the Golden Calf, and all did penance for it—indeed, many died for it, slain by my tribe, the Levites who had displaced them as Your principal servants. Assisted by my Brother Aaron and Colonel Joshua, I labored mightily to convince the firstborn that, like it or not, they had been displaced. Why? Well, You Yourself are a firstborn, so to speak—“The first to be, though never He began.”

Forgive me that last statement, Lord; I am well aware that You were never born. But I am growing older, and it is becoming more difficult to lead and direct this stubborn and stiff-necked people. Yes, yes; I know that the time is not yet ripe for Joshua to replace me—and the prophecy is cloudy: I do not know when and how that change in leadership will occur.

(Moses struggles to his feet, using his shepherd’s crook to assist him. He cocks an ear to the sky—again, hearing prophecy from the Most High.)

So, so, Lord—what is left to me? I have no progeny; Gershom and Elazar, the sons I neglected in Your service, are gone off, somewhere—I heard rumors that they remained in Egypt, and are doing their best to achieve citizenship, but the Royal Egyptian Immigration Office is making it extremely hard for non-native-born Egyptians to do so. And Pharaoh is strongly considering a wall to prevent refugees like Your people to return—well, that is all for the good, I suppose, though I am not sure. All is confused and bleak—

(Looks up to Heaven,one more time.)

Stand by me, Lord. I am Your faithful servant, come what may. But there is a reciprocity, here: You must help me to help the people. Ah well—Thy will be done. Amen!

(A rumble of distant thunder. Moses smiles, grimly, and exits.)

______________________________________________________________

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#torah study#drash#parsha#weekly parsha#bamidbar#bemidbar#b'midbar#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbos#shabbat#sabbath#oneshul#shabbatshalom

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shabbat Zachor: Amalekites, Egyptians, and a Promise

The Sinai Desert was still pitchy-black when Lt. Djer’s adjutant, Corporal Tem, shook his commander’s shoulder to awaken him. The lieutenant immediately arose—his training at the Royal Egyptian Army Military Academy (Heliopolis) stood him in good stead. He sat on the edge of his cot, blinking and collecting his thoughts.

Today, we pull patrol-duty in our Northwestern Sector, he thought, I must set a good example for my troops.

“It will be blasting-hot today in the wilderness, Sir,” whispered the corporal.

The lieutenant smiled ruefully. “It’s always hot in this furnace, Corporal,” he said, tersely. “Have the sergeant-major rouse the troops—quietly. We are on full combat alert, as befits us fortunate soldiers who guard the Blessed Boundaries of Holy Mother Egypt from any invaders or ravagers.”

The corporal nodded, saluted, and disappeared into the dark.

The lieutenant did his morning toilet, dressed in his cotton undergarment, and began buckling on his bronze body armor. Djer’s armor fitted a bit more snugly than usual. He had gained a few pounds on his last leave to his home village. His parents raised sweet dates, plums and figs on a little farm close to the Nile River. Pa’s sweet melons were legendary for their size, heft, and color, and he regularly won first-prize in the farmers’ market. Patting his belly, Djer left the tent to inhale the pure, sweet desert air, tinged by a salty breeze from the Sea of Reeds to the north.

“We await your orders, Sir,” came a voice from the shadows, which he recognized as that of Sergeant-Major Joser, his aide-de-camp in commanding 18th Regiment, Royal Egyptian Cavalry (“Jaws of Anubis”). “Will you be desirous of mounted chariots, Sir? It would not take but a half-hour to ready them for patrol and possible combat.”

Djer had thought about this the previous evening, and decided. “It will not do for the sake of maintaining mounted silence to take the chariots,” he replied, “on the chance that we encounter a desert tribe of Bedouin, and require a surprise attack. No, Sgt-Major; this day, our troopers will ride their mounts.”

“Very good, Sir,” said Sgt.-Major Joser, “I will have the troops ready their horses. All will prepare the saddles meant for warfare, not parade.”

“Do so,” commanded Lt. Djer.

Less than a hour later, the copper bugles sounded, and the 18th Regiment was under way.

“Which direction, Lieutenant?” asked the Sergeant-Major.

“Let us head towards the Sea of Reeds,” answered the lieutenant, “just to find any stragglers from that escaped mob of Israelite slaves. We are under orders to—deal with them.”

“Deal with them by what means, Lieutenant?” asked the Sergeant-Major. He was a grizzled veteran of many encounters with Egypt’s many enemies. An eye-patch gave evidence of the Old War with the Nubians.

“By any means necessary—including killing,” returned the lieutenant. I hate to think of murdering innocent women and children, even if they are Israelite, he thought. Still, we are under the orders of Capt. Sobek, who is in constant touch with the High Command at Royal Egyptian Army Headquarters. I have no choice.

The soldiers rode along in silence, whispering only when necessary. A blood-red sun was rising in the east. There was no sound, except the creaking of saddlery and the clank of lances against bronze armor.

“Sir,” said the Sergeant -Major, “We must halt, to allow Siptah, the Jebusite Scout, to study the trail and tell us what to expect.”

The lieutenant nodded. Siptah, agile and alert despite his advanced years—he was at least forty—practically vaulted over the head of his horse, and, lying on the ground, began sniffing eagerly, like a desert dog. Djer looked on in disgust—how could a human being, made in Osiris’s image, degrade himself into sniffing at the offal of passing animals? Still, he had to grant Siptah some credit—the scout was nearly always correct in his trail-judgment, and—besides an uncomfortable, earthy smell the scout had—Why can’t he wash more often? Djer would ask, holding his breath while he spoke with him—he was a pleasant enough fellow, and a great warrior, besides.

“What news, Scout?” he asked.

The elderly Jebusite grinned and rose, not bothering to dust the desert-sand off of his arms and legs. Arms akimbo, he stood before the lieutenant, not bothering to salute.

“If it please the Lieutenant, Your Worship—” began Siptah.

“Just Lieutenant will do, Siptah,” said Djer, fanning the air before his face. How can the poltroon live with himself? he thought, breathing through his mouth, “Give your report, please.”

“Israelites passed by—oh, perhaps one-two hours ago,” said Siptah.

“Good; we will shadow them, and make certain they are moving well out of Imperial Territory,” answered Lieutenant Djer.

Siptah raised one gnarly hand. “I have more to report, Lieutenant,” he said, and his grinning face grew grim, “There is also a war-party of Amalekites following the Israelites, perhaps just one-half hour behind.”

A voice from behind Djer called out gleefully, “What luck! Let the Amalekites finish what we ought to have done to those evil Israelites!”

Without turning, the lieutenant called out, “At ease, Corporal Henut! I called for silence in ranks!”

“Begging your pardon, Lieutenant,” returned Henut, “but I have more than a bone to pick with those abominable Israelites—they laid waste to my homeland, including my father’s little idol-shop! That Invisible God of theirs, jealous no doubt of my father’s stock-in-trade, caused it to be crushed beneath the weight of that insidious hailstorm. I hate those Israelites with every fibre of my being.”

Nodding at the Sergeant-Major, Djer ordered the detachment to halt.

“Military Police Detail!” ordered the lieutenant, “Apprehend Corporal Henut, and bring him to me.”

Henut found himself bound in papyrus-ropes, standing before his commander.

“Corporal Henut,” said the lieutenant, “for speaking out in ranks, and for contravening a direct order—”

“Begging the lieutenant’s pardon,” interrupted Henut, “What order was that?”

“Our orders are to shadow the Israelites, not to attack them,” answered the lieutenant, “nor to aid or abet any other people or nation who choose to attack them. We are merely in an observatory capacity.”

“Yes, Sir,” said Henut, sullenly.

“And for your outburst,” answerered Djer, “I am reducing you in rank to Private, and fining you your next three weeks’ wages. I run a strong, proud outfit, Private, and I will not have rapscallions such as yourself besmirching our unit’s record. MPs! Keep him under close guard, and, once we return to the Forward Operating Base, he is to go into the stockade for one week.”

The MPs led Henut away; because the unit was in the field, he was allowed to re-mount his horse, under their watchful guard. The detachment spurred on, again.

“What is that noise I hear, Sir?” asked the Sergeant-Major, “Is it the sound of rejoicing? Are the Israelites observing one of their pagan festivals?”

Lt. Djer listened. “It is not the sound of rejoicing or singing,” he returned, “It is the sound of war—hear the women’s screams!”

As the cavalry detachment mounted the hill, they beheld a ghastly sight: a band of Amalekite Bedouin marauders were attacking an Israelite refugee line—only, instead of attacking in front of the line, where the soldiers and young men were, the Amalekites were deliberately slaughtering helpless elderly, women, and even children.

“What shall we do, Sir?” asked the Sergeant-Major, “Our orders are explicitly to shadow the Israelites, and not interfere with their Exodus from our nation.”

“Still,” mused the lieutenant, “The orders said nothing about the deaths of the innocent.”

“What are you suggesting, Sir?” asked the old sergeant-major, already guessing what was on his young commander’s mind.

“Sergeant-Major!” commanded Lt. Djer, himself unstrapping his bronze short sword, as well as his cavalryman’s knife and shield, “I order you to have the bugler sound the ‘charge,’ so that we can redress the imbalance between civilian Israelites and armed desert bandits.”

“You heard the Lt. Djer,” called out the Sergeant-Major to the young bugler, “Prepare to sound the charge, on his order!”

“Wait a second,” said Djer, half-turning in his saddle to face his troops.

“Soldiers of Imperial Egypt,” he said in a stentorian voice, “I am commanding you to join me in defending a group of helpless elderly, women and children from a mob of murderous Amalekites. You know our enemy: he is merciless, and so must we be. If you bear any ill will towards the Israelites, you may remain under guard back here with our Military Police, and I will arraign you later for refusing a direct order from me, your commander. But I hope and expect that every man-jack of you will gain great honor for both our Mother Egypt this day, and for Anubis, for whose ferocity and fairness our regiment is named. Will you join me?”

Sadly, the remaining record of the 18th Regiment of Horse (“Jaws of Anubis”), Border Patrol Detachment, Royal Egyptian Army, has been lost. May Osiris welcome their glorious dead,and give plaudits to their triumphant heroes.

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#torah study#drash#shabbat zachor#shabbos#sabbath#amelek#parsha#weekly parsha#rabbi david hartley mark#oneshul#purim

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vayakhel: Putting God into a Box

(Scene: An open, bare field in the middle of the Israelite Camp, blocked off from the rest of the camp by an elaborate fence, consisting of wooden pillars fitted into brass sockets, ringed and crowned with silver hooks. These hold white linen sheet-curtains, designed to conceal the construction activities within. There is also a half-built tent, covered with cloths of goats’ hair, wool dyed blue, scarlet, and purple, and the skins of both rams and dugongs. The foundation of an unfinished brass altar stands before the tent.

Sitting on the ground, taking a break, are the two builders: Bezalel ben Uri and Oholiav ben Achisamach. They are sipping at clay water-jugs, and mopping the sweat off their foreheads—it is thirsty work, indeed. But they are proud to gaze upon the median stage of their labors: this is soon to be the Mishkan, or the Shrine of their LORD GOD.)

Bezalel: Another day of successful planning, building, sawing and casting metal, hey, Oholiav?

Oholiav: Weren’t those Danites supposed to come help us, today? Why haven’t they shown up?

Bez: As much as the Zebulunites showed, yesterday.

Oho: ‘Tis clear, my comrade-in-architecture: these Israelites lack the skills and patience to build.

Bez: Ironic, isn’t it? What, after all, were they doing in Egypt for four hundred years, if not building?

Oho: Well, there’s a difference between building a Shrine to God, and being whipped into hauling great blocks of sun-dried mud, or sandstone.

Bez: Never mind: I will speak to the head of the Danites—what’s his name?

Oho: Oh—I must remember: Amiel ben—ben—

Bez: Gemali. Well, Mr. Amiel will have my temper and my strong right arm to answer to, he will.

Oho: Oh, what’s the use? The most one can expect of these Israelites is complaining, stuffing their faces with Manna, and bragging about how religious they are, or learned—not that I ever see any of them actually studying the Torah.

Bez (soothingly): Calm yourself, Avi. I will speak to the Prince of the Danites. I may even push him around—just a little, for breaking his promise.

Oho: Only, don’t hurt him. We must not, as builders of the Tabernacle, permit innocent blood on our hands, even if the tribesman was supposed to be here, to help. And the truth is, we do better when it’s just you and me: these others tend to be bossy, especially when it’s something about which they know nothing. Really and truly, these Israelite men, by and large, know nothing about fixing things around their tents, let alone construction.

(There is a knock on the pillar nearest the two.)

Bez: What’s that? Who’s there?(Upon seeing who it is, he snaps to attention, as does Oho) Sir, yes Sir, Major Joshua!

Joshua: At ease, Holy Architects of the Lord God. Ahem. Pleasure to be here, in our soon-to-be dedicated Shrine. Well. May I enter?

Oho: If the Danite volunteers, had they shown up, were to be permitted to enter our Sacred Precincts, how much moreso may an Officer of the One True God?

Joshua (squeezing between the barrier-poles): Yes, yes. I was sent by Rabbi Moses to ask you when the Shrine will be ready for both sacrifice and worship. After that—um—unfortunate incident with the Golden Calf, Moses thinks a Shrine would be an excellent preventative to idolatry; it would give the People of Israel some focus.

Bez: Um—two weeks.

Oho: Or four. At most, five weeks.

Joshua (disappointedly): Can you not speed things up, a little?

Bez: Well, there are only the two of us. If the various work-parties promised to us on a daily basis were to actually show up to help, it would speed things up.

Joshua (frowning): Let me understand this. You have been building, crafting, smelting, and designing this entire complex—by yourselves?

Bez & Oho (proudly): Yes, Sir; so we did.

Joshua (shaking his head): That’s not the way it’s supposed to be, at all. Let me look into this. There must be a better way (Saluting, he exits by squeezing between the poles).

Oho (to Bez): Think that anything will change?

Bez: Doubt that. You know these bureaucrats: Promise much, but Deliver nothing.

Oho (sighs): Well, break’s over: let’s get back to work. Where is that brush and pot of golden paint that I was using before?

Bez: Wasn’t it—over by the south side of the Altar?

Oho: Can’t find it, now—and I really, really wanted to get that gold trim on the edges of the Altar by end of work, today.

Bez: Avi, look over there!

Oho: Where?

Bez: That same corner you just told me was wanting gold paint. There is a fresh coat, right where you were going to paint it!

Oho: Why, so there is! Did you paint it, Bezalel?

Bez: Not I.

Oho: Nor I.

Bez: Do you know what this means?

Oho: What?

Bez: There are Invisible Assistants helping us, that’s what. Angels. Spirits.

Oho: If that’s true—and I have never before witnessed such a miracle—it means that God Himself is eager to complete the work, and has sent Angelic Messengers to assist. A miracle! And you can—

Bez (finishing his sentence): Send to Major Joshua, and assure him that we will make that two-week window. Praise the Lord, from Whom all Builders benefit!

(They fall to their knees and worship)

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#torah study#drash#vayakhel#wayyaqhel#Va-Yakhel#Vayak'hel#Vayak'heil#Vayaqhel#parsha#weekly parsha#shabbat#shabbos#sabbath#rabbi david hartley mark#oneshul

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

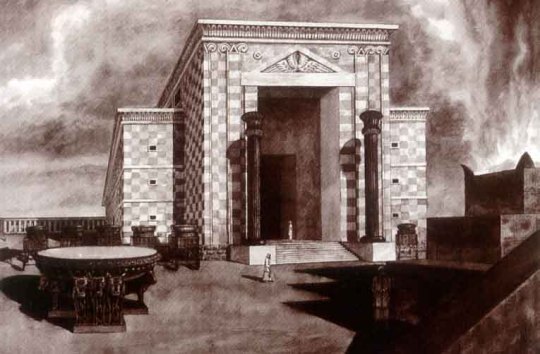

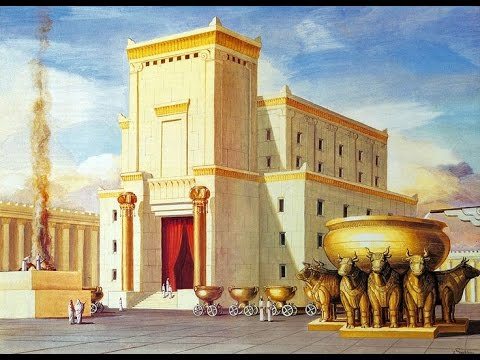

Pekuday: The Report of Hiram, King of Tyre

(Please note: this week's drash covers the haftorah for Parshat Pekudei -- I Kings 7:51-8:21.)

I, Hiram, was king of Tyre, back around—oh, 1,000 BCE in your reckoning. King Solomon of Israel was my liege lord—your Scriptures may state he was “my friend,” but this is not entirely accurate. Had I not supplied him with the bulk of the building materials he required to build the Holy House for his Invisible GOD, he would have angered quickly, and, at the head of his horse and foot, come thundering up the Mediterranean Coastal Road to invade my lands, take me prisoner, and despoil my people. I therefore thought it meeter to supply him with—well, whatsoever he requested.

Solomon’s father, King David, was my original Israelite ally, but I feared him far less than his son, so far-famed for his wisdom. David was always too involved with the Philistine Wars, and with various palace intrigues (David had a large, selfish, big-headed family)—not to mention his hunger for women who happened to be married to other men. Leastways, he tended to ignore me, though we did cooperate in our foreign trade. Our triremes reached so far as India, and, I believe, the Philippines.

Chief among the materials I supplied Solomon were our famous Cedars of Lebanon; I understand that they made a strong and spiritual impression on you people, you Israelites. Why, your poets and psalm-singers included them in several psalms, which I appreciate—sort of my own, personal contribution to the development of your—would you call it a faith? I will never be able to fathom this faith, Brother Hebrews. Your Holy Temple, as I believe it is called, was and is a burden on your taxpayers—who does this for an Invisible God? If He is invisible indeed, what need has He for a House? It is too complex for a mere pagan like myself to fathom.

What we Tyrians do is to worship idols. Idols are reliable; they stand by you, and you can always purchase some for home use. As for a temple—what need have we of a temple? I myself, as king, am High Priest of Baal; there is a massive pile of stones and clay just outside my palace, and my people gather there regularly to worship.

To return to your temple--remembering the Israelite threat of invasion were I not to make my freewill offering to Solomon and his God, I freely appointed squads of woodcutters and wood-carvers to provide my headstrong lord with howsoever many logs and poles he required. along with much gold and jewels—we Tyrians are traders, and trade has been good.

The most peculiar feature of Solomon’s Temple was the “Molten Sea”—a vast bronze tub held aloft on the backs of twelve brazen bull-statues—meant to represent the months of the year, as Solomon told me. Still, I found it both grandiose and peculiar. I asked my royal friend, Solomon, “What is the purpose of this mighty bathtub?”

He looked at me askance—I have a tendency to speak sarcastically, but, take me as I am—and replied, “To provide water for the Priests and Levites to lave themselves, to purify themselves prior to engaging in Service of the Lord.”

“And what is this Service?” I queried further.

His brow narrowed, and he said, “Hiram, you are my friend—that is, as long as your people pay me their taxes—but you are, forgive me, a dolt. Should not my priests be spiritually pure, before they offer sacrifice?”

Just my point, you see: if these hapless servants of Adonoi—I believe that is one of His many Names—are about to slaughter, cut up, and burn chunks of meat before their God, why can they not wash only afterward? And why not have a series of smaller bowls and jugs from which to wash? Still, I know my royal lord’s predilection for spectacle and magnificence—that day, he was wearing, not one, but several cloaks, all silk, flax-and-wool, and cloth-of-gold atop all.

I kept my peace.

The construction of the entire Temple—building, walls, decorations, and all—took 143 years, I understand, meaning that there was preliminary work, even during David’s time, despite denying this in the Israelites’ Holy Books.

Finally, the work was done. I recall how relieved all the workers and artisans looked—Solomon was something of a martinet, and not the easiest monarch to work for. Besides being king, military commander-in-chief, and nominal High Priest, he was also a judge. People feared his judgments—we once discussed his handling of a case involving two harlots who were arguing over a live babe. Which one had borne it?

Solomon pondered a bit—he had a way of twisting his fingers in his beard which convinced all that he was in deep thought, but I knew he was receiving prophecy from his Invisible God—and announced, “Let the baby be sliced in half.”

Well, what an uproar arose! One of the women cried: “Oh please—give the baby to the Other; I relinquish all rights to my child—only, please don’t hurt him!”

While the Other had a ghastly grin on her face as she called out, “Slice the babe, slice him; let neither of us have him.”

At which point Solomon intoned: “The babe belongs to the woman who demands we not hurt him. Take your child, Woman; go in peace.”

As for the Other, he fixed a steely eye on her and said in stentorian tones: “You, jealous and a would-be murderess; you shall walk the treadmill of my wheat-grinders, for the rest of your life.”

Later—I was visiting on a state embassy, and had to get back to my own quarrelsome nation the very next day—Solomon and I stood on the balcony of his father’s palace (In the very room in which David had decided to have Joab murder Uriah the Hittite, and steal his wife, Bathsheba—strange indeed were the ways of these Israelite rulers!)—I turned to my friend, the ruler to whom I was subservient,, Solomon, and asked:

“Tell me truly, Solomon. Would you honestly and—forgive my saying it—bloodthirstily have murdered that tiny babe, if only to prove a point and settle the argument of two gutter harlots?”

Solomon turned his eyes on me, blue as the Great Sea (You call it the Mediterranean) and deeper still than that mighty ocean:

“I can only say and do what the Almighty commands me. Not for myself do I act, but only for the Greater Glory of God.”

As I say, he was a strange duck, that Solomon, King of the Israelites. I was glad to return home.

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#torah study#pekudei#pekude#pekudey#p'kude#p'qude#parsha#weekly parsha#shabbat#shabbos#sabbath#rabbi david hartley mark#oneshul

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Metzora: The Leper Recovered

This is the man

Who may have been a leper.

These are the living birds, all pure,

Brought by the man

Who may have been a leper.

This is the wood

From a cedar green,

Two living birds

With feathered sheen

Brought by the man

Who may have been a leper.

This is band of scarlet wool

Wrapt round the wood

As the living birds

Sing to the man

Who may have been a leper.

Here is the hyssop for sprinkling

The living blood of the slaughtered bird,

Drips a saucer of blood for surviving bird,

With the scarlet wool

And the cedar wood

For the man

Perhaps a leper.

Here is the Kohen

With the hyssop-plant

Who flecks the blood

Of the now-dead bird,

Winding round the red

And bloody wool

And stirring it up

With the cedar-wood,

For the man

No longer a leper.

Here is the man

Who releases the bird

Dripping blood from the air,

Symbolizing new life

And departing the old

(The dead bird lies),

Life precious as wool,

Life strong as the cedar,

As he cuts off his beard

Shaves his eyebrows off

As bald as a newly-hatched human egg

Bathes in living water

Puts on clean clothes

And continues life:

A man no longer a leper.

But soft! He takes lambs

One female, two male

And a lug of oil.

One the Kohen takes

And waves a lamb

As a wave-offering.

One the Kohen kills,

Daubs the man with its blood

On his erring right ear,

His right big toe,

His right-hand thumb,

To banish the blemish

And begin a new life

For the man who was once

A leper.

And when you hear of this ceremony,

Cause it to be written

In the Holy Scroll

Of the Judeans.

Rabbi David Hartley Mark is from New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended Yeshiva University, the City University of NY Graduate Center for English Literature, and received semicha at the Academy for Jewish Religion. He currently teaches English at Everglades University in Boca Raton, FL, and has a Shabbat pulpit at Temple Sholom of Pompano Beach. His literary tastes run to Isaac Bashevis Singer, Stephen King, King David, Kohelet, Christopher Marlowe, and the Harlem Renaissance.

#progressive judaism#judaism#jewish#torah study#drash#metzora#metzorah#m'tzorah#mezora#metsora#m'tsora#parsha#weekly parsha#rabbi david hartley mark#shabbat#shabbos#sabbath#oneshul

1 note

·

View note