#social ecology

Text

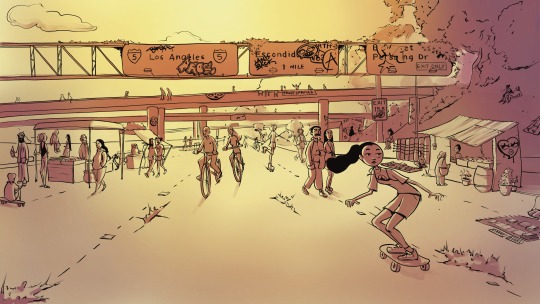

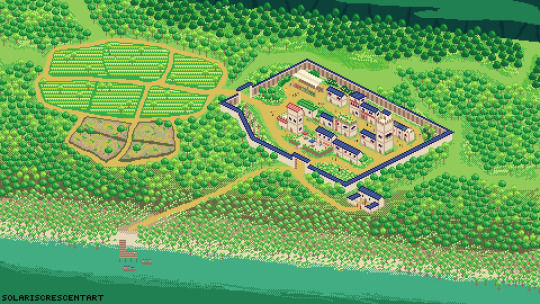

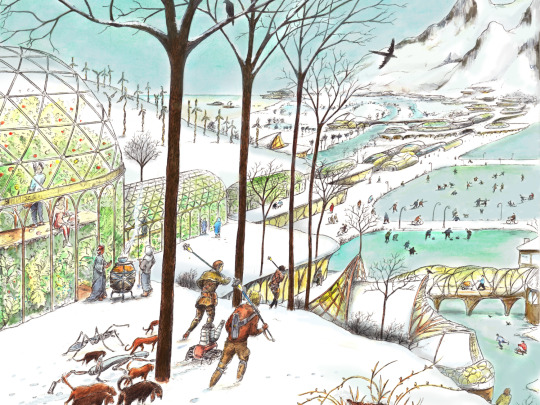

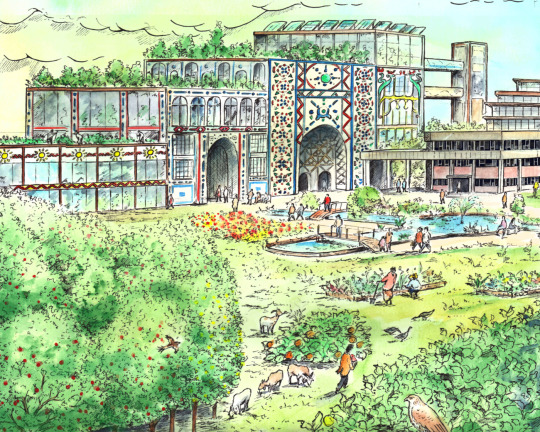

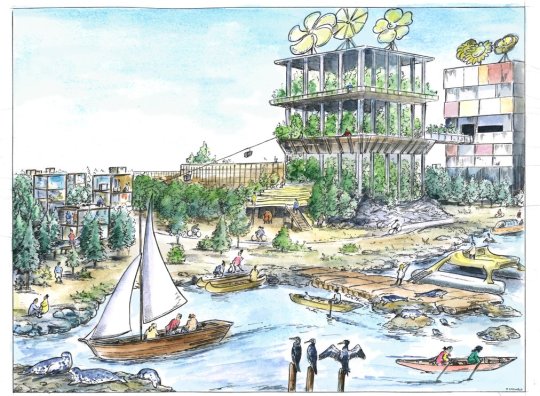

Solarpunk Art 2023 (BIOREGIONS)

Temperate Grassland in Ukraine by @the.lemonaut.

Desert/Xeric Shrublands in South Africa by @draakart

Mediterranean Forests/Scrubs in Southern California, USA by @helentadesseart

Boreal Forest by @_frandszk.

Mediterranean Forest/Scrubs in Tijuana, Mexico by Limonarte

Subtropical Evergreen Forests in South China & Vietnam by @solariscrescentart

Tropical & Subtropical Moist Broadleaf Forests in the Philippines by @lacan.lacapat

Temperate Broadleaf & Mixed Forests in the Ozark Highlands of the USA by Xiantifa

Temperate Broadleaf & Mixed Forests by Arikadough

Temperate Broadleaf & Mixed Forests in Indiana, USA by Toby Raab

Subtropical Evergreen Forests in South East Asia by @erisdar_art

Various Bioregions by Dustin Jacobus (@solarpunkart)

696 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes Toward Finding Community, Or, How to Find Community When You Feel Isolated

Neoliberalism sucks for a ton of reasons. From the enclosure of every common, to the commodification of every creation, it feels like a muzzle on humanity that gets tighter and tighter. One of the most underexplored aspects of neoliberalism is the way in which it creates and reinforces isolation. People don’t really have communities outside of consumption or compulsion. This is problematic for a ton of reasons, namely that it prevents us from fulfilling our basic needs. Humans are social creatures. People need to have connections with folks. People may not all need the same levels or intensity of connections, but connections are important nonetheless. To lack in the ability to socialize meaningfully is to ensure worse health outcomes, mentally, emotionally, and physically. But, I don’t mean to freak you out. I think that there are steps we can take to star building community, bridging gaps with the people around us.

Think About What You Want

When folks feel very isolated, it can be easy to accept anything. If we’re in a vulnerable state, that could leave us open for ending up in precarious situations. One way to fight against this is to start from the position of imagining what community looks like. Is the type of space we want to occupy based around interests (fandom, hobbies)? Religions, spiritualities, social issues? If we are able to list the things that excite us, we have a good idea of what to look for, and can focus our efforts towards finding those spaces.

Find the Watering Holes

With the spaces we’re interested in on hand, youcan find where folks gather. Every community has virtual and/or in-person spaces. For example, if you’re a film fan, you can look for indie cinemas, folks putting on screenings, or look into film societies where you live. For activism, I’ve written a whole guide on how to get started. Looking for those spaces will allow you to start getting integrated in the space. Really think about how you can occupy the same physical and digital spaces of people who are into what you’re into.

Go Meet Folks

Now, this may be difficult, depending on your disposition. The quickest way to meet folks is to put yourself out there. It’s always vulnerable to put yourself on the line in this way, but it’s super necessary. When you’re in spaces with similar folks, you have talking points built in! You don’t have to worry if the folks around you will like movies at film club. If you are enjoyable to be around, through being nice, interesting, and/or being an active listener, you’ll be making connections in no time. If you’re not willing to talk to folks, it’ll be hard to make connections. Being open is an asset towards the end of getting connected. At the very least, consistently go to events and spaces in your interest area(s). Maybe you’ll bump into an extroverted person that can show you the ropes.

Be the Change You Want to See

As you get out there, think about how you can start catalyzing community. Maybe you host a dinner for neighbors. Maybe you start a book club. Or even a neighborhood garden, or cleanup event. In this way, you’re flipping the issue on its head. You’re creating the space to meet folks yourself. It’s like being a magnet, drawing others to you.

We need community. It’s a necessary thing, you know? So, hopefully, keeping these things in mind helps in that regard.

#economics#economy#econ#anti capitalists be like#neoliberal capitalism#late stage capitalism#anti capitalism#capitalism#activism#activist#direct action#solarpunks#solarpunk#praxis#socialism#sociology#social revolution#social justice#social relations#social ecology#organizing#complexity#resist#fight back#organizing 101#radicalization#radicalism#prefigurative politics#politics

526 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta said, “Everything depends on what people are capable of wanting.” I have to agree with this. If we cannot develop the imagination to conceptualize a qualitatively different world, we are doomed.

Dan Chodorkoff, Social Ecology: A Philosophy for the Future

227 notes

·

View notes

Text

#civilization#murray bookchin#book is cities without urbanisation#anarchism#social ecology#anthropology#urban planning#urbanism

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Social Fabric; Clothing in a Free Society.

A Speculative Fiction Essay.

_

Amongst the anarchists, there are great collective lending libraries of clothes, and accompanying them are great collective laundries. Most clothes that are washed in the collective laundry are held communally, and can be selected from the whole on a basis that anyone can use them, but no one is allowed to destroy them.

Those who do not wish for a great variety of clothing will often go to the seamstresses and tailors and have constructed for them a few perfectly chosen items, or will select a few items from the whole which are close enough to be made over to their needs. Often, these choice items are of a form of traditional dress; those articles that have proven themselves under the wide test of history; kimonos, saris, chitons, the great plaid and shirt, shift and petticoats and stays with an over dress, the various robes of the various monks and nuns - although, there are some more recent designs which serve the function just as well, such as the common overdress. Many of these traditional and custom dressers have very few total articles of clothing, but also rarely share them. In a majority of these styles, there is an under layer that is easy to launder, and most individuals have 2 or 3 of these under layers, and launder only them frequently and often by hand or in smallbatch guilds, creating little strain on the great laundries of the clothing libraries.

With these two main ways of organizing one’s dress, the society manages to keep overall production rather low. Those who wish for variety hold their variety in common. Those who wish for more custom design tend to need little more in the sake of variety. In any case, the total number of clothing articles someone from either group may be using at any one moment is fairly comparable.

Those in society who are at the outlier of size and shape interact similarly to the rest, just in an expansive system of time. New articles of clothing are almost always brought into the fold because an individual cannot find something that suits their exact desires or needs, and there is nothing available which would be appropriate to make over and reshape for the wearer. Items are returned when they are no longer suited, and then they are kept in common till they are suited to another, or made over, or worn out. When one is very large, or needs medically assistive clothing, or is very tall, they have clothing made if there is none available. However, because there is less of a demand on these more specific articles of clothing, they are also worn out less, and take up relatively little in storage space. And so, the clothing of these outliers is also in the library system, just checked out less often- just as a specialized book might be. If something is so particular that after a few generations it still sees no use, it can be made over completely or scrapped for stuffing, and new items can be made for those who come along.

Due to the nature of bodily change; that we will grow, that we will shrink, that we will convert to new religions and reembrace old ones; that we will give life and be taken from it, there are always a fine number of perfectly crafted custom clothes being returned to the share houses and clothing libraries.

Having worked in the laundry, and having worked in the cotton fields and flax thrashery, and in the hunt or slaughter, and understanding of the limitations of production, those who make clothes take great care to make them to last. But that is not the only way that they ensure that their uses can be long in years and multitudinous in function. Clothing that is being made for general use is often made with removable panels to adjust the sizing, and over cloths are often pieced together and held by a great many laces, easily stripped stitches, or zippers. The sleeves are often designed such that many are in great bell shapes, with fastening cuffs that can adjust to a variety of sizes. Buttons and loops can be used to bunch or loose the large folds and plumes of fabric, or to hold them higher and short, which creates a vast array of looks and shapes and configurations of one garment. The same is true of many of the great skirts of the common overdress, which is designed to be floor length, but which can be easily folded and set to rest just past the crotch in a great petticoated cone; or nearly any length in between. These adaptations, along with the lacable panels on the bodice, mean that these dresses can sometimes be worn from child to elder in many configurations, sometimes even by the same individual across a lifetime.

The lower total articles needed by the society, and the immense length of time that many articles stay in circulation, means that garment workers can take much more time for the planning, drafting, patterning, and stitching of each garment. To assist them with this task are the vast collections of patterns, tucked away by generations of previous stitchers, and curated by the many librarians, historians, researchers, and other everyday individuals who take their interests there. There are also a great many people in the society who seek something to fill their minds and their hands, and whom are willing and eager to assist with the hand sewing and embroidery and button hole stitching; but not everything is done by hand. Where it is of no sacrifice to the garment's quality, mechanical means of stitching, riveting, and weaving are used. Those within the society are not against such machinery; they are only against its application for the sheer purpose of speed when speed is not warranted, or the purpose of abundance when clothes already abound. In this society, it is seen as the duty of everyone, the most sacred duty, to use resources in the best ways possible. To intentionally make an easily-exhausted garment is seen as a great disrespect to the cotton, linin, wool, or hide that gave itself for the production, and it is seen as a great disrespect to the others who helped harvest it, weave or tan it, stitch it, store it, and wear it.

The clothes are maintained with regularity, often by each wearer, and also by those who take their work at the laundry. At the great communal undertakings, such as a large harvest or construction, it is not uncommon to see groups take long lunches and darn each other's nipped clothes. In the community houses and eateries, there are also a great many people whose fidgeting hands turn just as gladly to mending as to creating. Objects being moved from one repository to the next are often passed along with people on the rail lines - and often, they reach the new destination having been embellished, cherished, and turned over several times by several hands looking to find where they are weary.

There are many regional variations in dress that develop to suit the climate and culture of the wearer. However, the overlays of climate and culture tend to be rather expansive and slow, not reaching sudden shifts upon some border. And so interchange between the local systems of depositories takes place in overlocking regional scales, with each library of clothing taking its exchange and refreshment from those nearby. The microcommunities of regular laundering and stitching and curating in any area tend to have some overlay with one another, and that overlay allows them to contact one another to ask for specific patterns, fabrics, skill sets, or garments to be shared or exchanged or gifted.

All members of the society participate in the production of attire, as the production of attire is a result of all the interlocking elements of the society itself. Urine collection assists in the processing of wool and leather. Leather and wools themselves are a byproduct of ecosystem management tactics. Sheep eat away at invasive and aggressive plants, and they form a coat to keep themselves warm. They do not shed the coat of their own accord, and those who assist them are left with the need to dispose of it. Not wanting to be wasteful, they turn it towards the purpose of fabric. The textile it makes is incredibly useful; it is warm when wet, it is water resistant, it can hold its shape, or it can be felted into new ones.

This is the general principle of the anarchist’s, that all society is in process, and that the meeting of one need is always in process of the meeting of others. Interlocking systems, in which each individual does what is most helpful for the least effort given their personal and social circumstances, and in which the whole of the society takes on together that work which no one likes to do very much, leads to little begrudging in labor. And the complementary design of the ever changing social systems leads to new innovations being constantly added into the system. The ecological project of invasive species removal leaves a grand number of seeds which cannot be planted; and so the largest are turned over by jewelers as beads, and rendered sterile, whereas others are pressed as dyes, or sterilized as coat stuffing. Many other parts of this flora rendered into cordage or fiber, assisting in making the body of clothes that can be selected for different purposes, but also in the weaving of baskets, which aid in the transport of many things besides the clothes themselves.

Overall, the relationship to clothing amongst the anarchists is their relationship to a great many things. It is complex, as the needs and desires of the community are complex. It is seen at scale, as the management of resources must always be done. Each individual playing their part, the day to day small scale of weaving, wearing, washing, and darning; and the social organism as a whole managing the long term store and circulation. And even then, the social organism and the individual being on the same continuum of self, each covers where the other cannot.

Basic mending skills -in relationality and in fabric- are acquired by most through mentorship, sometimes with relatives, but most often mentorships develop out of the simple connection between one who knows and one who will come to know. The communal holding of labor creates a great many opportunities to ask questions of artisan crafters, and the slow nature of production, and the abundance of skilled crafters, lends to no shortage of time for education. These mentorships often create lifelong structures of support and kinship, and can serve as a primary social means for transference and norm setting, but not all are so long term. Some last but just a single moment, in a single stitch. The informality and overlapping of the mentorship structure leads to many students and many teachers, and often one is a student of one craft and a teacher in another, reversing the roles of knowledge giver and receiver, flattening the power between. And when that is not enough to flatten the hierarchy of knowledge, the simple giving of knowledge over time, and the gathering of one’s own skill, brings the mentor and the student together in talent and regard. If one teacher is a jealous guard of their hardwon tradeskills, the student simply moves on and learns from another, or watches and interprets the actions to recreate them.

Those who are less socially skilled, or who find themselves no compatible mentor, or simply desire extra or specific training, often attend lectures and workshops and such that are arranged by other crafters. Often, these workshops are organized out of a sheer exuberance with one's work, an utter yearning to share information about it. Occasionally however, some person or group will ask of someone to share in an open setting, and this is rarely refused.

There are of course a great many people who participate little to none in the direct social production of clothing, but whose very existence, and whose feedback and desires, inform the trends and advancement of production. There are those with little use of their hands, or an inability to learn motor skills, for whom laundering and stitching and patterning are most often out of reach. The abundance of high quality garments, seamsters of all skill levels, and the length of time in which clothes can remain all lead to their being plenty extra to go around. In fact, it is in designing assistive clothing for these individuals that many crafters take their finest joys, and sharpen their design skills towards greater invention. In building a dress suited for all seasons, not abrasive to the skin, and which can be put on and adjusted with the use of only one finger, for instance, even the greatest crafters must return to thoughtfulness, experimentation, and research. For this reason, those circles of high craft and artisanry spend many meetings and byside conversations discussing the nuances of clothing the disabled. Disabled people themselves, especially those who cannot participate in social clothing, often host the most widely attended lectures and roundtables within the halls of the great laundries and pattern libraries.

Babies also do very little to participate in laundering or stitching, except occasionally bring smiles to the eyes of those doing such work.. And yet it is the babies' clothes that wear out the fastest. They often do not notice the holes to be darned, nor do they ask others to darn them. They take no care when catching the nape of their jumper on a twig, and move blithely forward regardless of the damage. Their exemplary quick growth often means things are quickly returned to the library of attire. However, babies rarely suggest new designs, or give clear and concise feedback on flaws or opportunities, and they almost never order custom designs. This is all of little concern to the stitcher, in spite of it all. Babies' clothes are easy to make, famously small, and can be incredibly entertaining. A swaddling cloth designed to look like a fish becomes, when worn, a stunning image of a baby being eaten by a fish. When the baby is sad, the baby looks sad about being eaten by this fish, and this is heart wrenching and sympathy driving. If the baby is happy, the baby looks happy to be eaten by the fish, and this is silly and jovial. In this way, design can be used to help assure appropriate reactions to the baby's behavior, ensuring socialization and emotional coregulation. The babies being dressed very funny also serves as a good impetus to look at them with regularity and rigor, forming one line of care in the overlapping fabric of child rearing. For all of these reasons, it is not uncommon for the tired milliner to lay down their dress form, and take a restful opportunity to stitch some baby clothes. There are a great many festivals and art fairs in which baby clothes are shown as fun and enriching representations of the collective’s ability. The novelty also rarely wears away, as babies grow so quickly and baby clothes are exchanged so widely that one is always seeing new babies in new fun fits, doing new silly things.

Still, though, the novelty and sweetness of a babe does little to assuage the dread of laundering the baby's diapers. There are a few in the society, however, who don’t quite mind the smell, or who cannot smell it at all. They cannot alone handle the masses of baby breech clothes, but as everyone does what is most helpful for the least effort, there's a lot of effort left over for the more difficult and undesirable tasks. When each knows it has been done for them, and -should things go well enough into age- will be again, it is not hard for most to swallow their pride. But still, some cannot handle it, and turn themselves to other unloved tasks to take their share in the whole.

The menstrual pads and rags and cups are much less challenging, as most can be rinsed or boiled and then washed aside the rest. The blooded water is often boiled down for meal, to be used in the fertilization of soils, just as the wastewater of the babies and the incontinent are processed into the greater waste treatment for ecological return. All things, even the least desirable things, are revitalized to make part of a complete system. The laundering can circle back to the growing of the very fibers from which the laundry came, making them thrive alongside their niche neighbors and other biologic users, such as the butterflies and flowers and vines that form the very dyes that are then represented again in the clothes embroidery and patterns.

There are, of course, some items of particular sizing and customization which must reliably be returned to each individual for whom they were made, until such time that they are no longer of direct use to them. The low sorting pressure applied from the communality within other aspects of the laundry system leaves this a much less daunting task. Those working in the laundries do not have to return each item to its preferred wearer; infact, relatively few and relatively small items are returned. Injury preventing daily support items like bras and corsets, and medical assistive items like splints and braces, take the first priority in both washing and in sorting. Many of these items are also designed to need fairly irregular washing, but the labor required to make them, and the changing nature of the body, often means that wearers rarely have multiples that suit their exact specifications. In this case, the library laundries also keep on hand more general purpose items that perform the same functions, if not quite as specifically. General adjustable braces, a selection of corsets that previous users have given over to the system, a variety of wrap bras, compression bras, and retired bras all serve the intermediate function whenever a custom item is in the wash, awaiting repair, or under construction. The sorting of other items is not unavailable, just rarely used. The most common requesters for this are those who wear underdresses and undershirts, and these being relatively easy items to launder and to sort, this request is most often obliged by simply placing a hold on the item in question. However, something given over to the larger system always has some risk of being missorted, or mistakenly checked out to another, and this is understood by those who choose to handover such important items for general laundering. Hand laundering or small batch laundering are often tactics used to mitigate sorting pressure and ensure diligent return.

Small batch laundering forms a layer of communal organization and laborsharing that is far more personal, and used for more personal items. Crotched underwear is one item for which many wearers have their own personal or near-personal supply. Except in the coldest of environments, these items are rather small, and not difficult to hand wash or small batch launder. These items are often shared between small groups of friends, family, or partners, but just as often held individually. Within the larger laundry system, there are often undergarment guilds which co wash and sort together. This smaller scale tends to provide more comfort and ease than sharing such personal items with a whole library's worth of users, but also helps benefit from the pooling of labor. Still though, there are those who hold these garments in full commons, taking from the library whatever will fit their body and their use, and returning it with no desire for privacy. It is the nesting of larger scale and smaller scale systems that makes the meeting of all of these seemingly conflicting needs simultaneously possible.

There are also some for whom crotched underwear is rarely worn, such as those who primarily wear skirts and underskirts, or shifts or other underdresses, and they often hand launder out of a sense of ease. A couple shifts can take only a moment to rinse, and are often set in soapy bathwater, then rinsed in clean water, then hung to dry. This process fits so neatly within the routine of many wearers that it forms almost no extra labor. However, any particular stains or longwear smells are often requiring of a more specialized removal, and so shifts are then sent to the laundries. This rare return makes individualized sorting somewhat unnecessary. In the great rooms and halls and closets of the libraries, there are sections for different categories of items. One room or wall may be devoted to underdresses, with each section sorted by color, then circumference of the garment's fabric at its waist point, and then from shortest to longest. The measurements of each are typically then sewn in tags to the outer hem. This creates an ease for those seeking to find something in their particular size and use, often such ease that one can find the exact item they left to be laundered just days before. One can even send a message ahead to hold an item, and each item’s tag has a unique identifier. Occasionally these are barcodes, but most libraries have their own systems of identification tagging. The selection of underdresses may be large, but the selection which meets one's needed measurements is often concentrated to a few racks per type of clothing item. In this way, very little time is needed to actually find desired items, especially considering most members in any given community have worked at least a few hours stocking their library’s shelves and becoming familiar with its methods and its collections.

Perhaps the most abundant particular clothing item is socks. In appropriate climates, many individuals wear sandals and slides much of the year, but even so, socks add that extra layer of friction and size adjustment which allows for wear during even hard labor. The greatest extent of clothing mechanization takes place in the weaving of these thinner, warm weather socks. These wear out extremely quickly. A pair of thin socks may only last the dedicated wearer 5 or 10 years, and then, that is with less than weekly wear. Those socks held communally often last even less time, being worn near daily, and get worn out in about a year. The society does have an ethos of repair; however, these items being so thin, and also so easy to produce, they are one of very few items in the society where repair is less sensical than disposal. This quick disposal does form an abundance of easy rags. The society does also have purpose made rags, often those made of old clothes converted to new lives, but the socks fill a different role, especially in cleaning those things that are rather unpleasant. It is no great loss if they are sent to an early life in the compost, but many are used and reused as rags for longer than they ever survived in their intended purpose, as is with many things. The abundance does also lead to them being seen as wonderful test items and craft supplies. A learner trying out a new stitch may use an old sock, and worry less about ruining it and more about learning. This allows breathing room for mistakes within a society where the proper use of resources is the most prized social virtue. These socks are often embroidered with strange frills, and are taken with the others and made into craft items. Dolls of sock are a common children's craft. Sock coats and capes are a pleasant and fashionable adornment, especially for the many festivals, which themselves are lined with sock garlands.

The abundance of socks, however, does not speak to a great uniformity of them. Many cuts, shapes, sizes, thicknesses, and materials are used. For the purpose of laundering, socks are separated from the rest of the clothes, and then themselves are split into batches by cut. From there, they are sorted by size. Different localities have their own standardizations of sock sizing and therefor their own sorting methods. One of the most common methods is that socks of a certain size have a certain number of horizontal lines across the toe. This method makes machine storting and hand sorting both fairly simple and reliable, as well as adding little extra to production. It does sometimes clash with other intended designs of the sock, however, and so is not universal. The interchange of people can also occasionally cause socks of one standard to enter into a sorting system of another standard. These tend to be placed in their own sections at the clothing library, and those who wish for a little more variety in their life often spend time digging through these to find the most different and unique examples, often saving them as personal items to hand launder. Most of the rest, though, are sorted by system type, and, if feasible, used as packing material when a shipment is made to a nearby area that uses that system. If there is no shipment to be made, or if there is more relevant and needed resources to be sent as packing material, then the socks are simply retired early. Even a near wasteless system must balance between reuse, return, and efficacious material and energy management. In such a case, having a few select categories of items which are generally exhaustible and low priority can free up the system to more easily prioritize everything else.

The rest of the worn out clothes are not treated with such abandon as the humble summer sock. The respect of the labor put into them creates little incentive to waste. Trimmings and leavings, the cabbage of the patternmaker, is used to stuff sleeping pillows and mattresses or coats, still being of high quality and not inundated with allergens. Old clothes worn to thinness find new homes in the cookeries and kitchens, assisting in the straining of broths and cheeses, or as the cover of steaming vegetables. The leftovers of cloth, after spending many years in their function with the body, can continue to serve for even longer after. The stuffing of seating, the control of erosion, the wrapping of fruit trees in a harsh winter, lining, all are beloved uses of the clothes of a great granfparent's generation. Work clothes are drawn from those items who are close to being put to these purposes, but whom still hold some rigor. Those tasks which may be most compromising to the cloth are often done in near dressup, emulating the visages of the past. This occasionally leads to rips and tears in the clothing, but it is seen as no great waste, and in the lack of worry, laborers are able to take joy and laughter in the mild embarrassment of a crotch seam bust open. Otherwise, many of those fabrics which are beautiful -but well worn- are turned towards quilting, or used as patches. This creates a fine degree of adornment and expression, with those who do keep personal garments being able to customize to the extreme, and with those socially held garments each having their unique quirks and flourishes.

It is the entropic nature of things to decay, and decay does reach the usufrutuctian society. However, this decay is made use of, slowed, understood, and worked with. Each moment where material reality causes a breakdown in the system becomes an adaptation within the system, increasing complexity and diversity, preparing for the next breakdown, and innovating for new uses. Moments of waste are turned over to become the foundation of other systems, or to be used as input. The very waste of death; that we may die and leave behind that vessel which has made us, is undone in its revamping towards use. The body is processed, with that which is meat serving the ecological role in carnivore rehabilitation, or in feeding those animal domestics which require it. The skin is turned over to leather, often making up shoes, or strong gloves. The same is done with those animals which must be harvested, either for the purpose of ecological management, medicine, materials harvest, research, or cultural use. Those items which would be contaminated if made from one another are made from the other living things; bog tanned hide and organ bags for food and water storage being the most common need. The usufructians do not harvest from animals what they will not harvest from their own dead, feeling no justification in holding only one species’ life sacred. Still, however, the human body does not provide for all services, and the death of animals is inherent to ecological systems. Some, not wishing to take life, utilize glass for drinking and food storage purposes, and avoid all leather whenever possible. But those who can not bear such heavy material,, often require the use of the more light and durable animal derived bags and wraps. These items are treated with even greater care than the fabrics. It is not uncommon that when one sees people sitting down to eat on the sides of the lush walkways, one will notice them spending more time looking over their packing materials than actually eating from them.

The use of animal products, human and otherwise, is treated with both graciousness and solemnity. A great deal of meditations and spiritual practices revolve in part around this posthumous use of the body. Usufructian funeral services are varied, with hundreds or thousands of regional, cultural, individual, and religious options to discern between; but even so, a great majority of them speak of the return. Not all return their body through leather and fed flesh; a great many are composted, returning to the soil which fed them. Some are burned in the great forest fires that bring the flowers. Bones are turned to field powder. All things that come from return to. From ashes to ashes, from life to life, from body to body, from soil to soil, from all to all; to be a usufructian is to eternal only borrow, to never completely own. The anarchist takes what they need, and gives to their ability; and in death, there is alway the last giving.

A central premise of anarchist philosophy is “From Each Their Ability, To Each Their Need”. In the world of the anarchists, the near complete overlap of hobby and labor, alongside complementary labor facilitation systems, social principles of nondestruction, and production paced to an abundant sustenance allows for this to be accomplished. “We who waste not want nothing. We who do not destroy are never led to destruction. We who meet needs are met in abundance,” goes the song the launderers sing to pass the time.

Amongst the usufructians, most beloved is the social relationship.This is the relationship of the individuals to one another, the individual to the society, the society to the ecology, and so on. The social relationship is, in essence, the whole relationality between all parts of reality, interconnected, caring and providing for each other. In this regard, all are cared for and all are accounted for. One who allows their clothes to tatter unmended will be doted upon by the community, offered a great deal of help in repairing them, and in stabilizing whatever aspects of their life must be out of order for such a tragedy to occur. One who does not maintain their leather storage wraps will be repeatedly brought food in glass containers, with many people offering to bring them food each meal, up to their mouths if needed, and to take the storage items to be cleaned afterwards. This is done with a special caution against condescension, and the work is passed amongst the abled participatory community as to not fatigue one anothers compassion. In this way, neglect is managed by understanding that it comes from a place of inability. Those few who are able, but unwilling, often find the hassle of being cared for more exhausting than caring for themselves, and tend to begin maintaining their resources once again. Unable and unwilling is rarely the case however. Most neglect comes from an inability in other respects, throwing one off of balance and out of systemic living. Those who are in greater need are offered care, and offered it with regularity and without shame. This care is like water, and sinks to the low places in them, filling them up, rendering them unneeding; needs continuously being met.

There are occasionally those who seek to accumulate, not wishing to return their clothes. This is often met without issue. A few hoarded items by a few people is not enough to break such an abundant and cared for system, and most of these individuals return their hordes eventually, after community support and care drives them to unlearn their anxieties of scarcity or fear of noncontrol. However, occasionally, one or a few people will attempt to checkout a great sum of the most desired and necessary clothing, setting themselves up as lords of such a resource, and demanding that others give to their whim in order to attain things. In the many upstartist attempts of this nature, this is thwarted simply by those users of a library going to another library for whatever items are now locally scarce. Those whom have such hoarded abundance are then denied the access to remove further items of the type they took, and are given only standards that meet whatever real gap in need they have. Eventually, their whims not being sated, and their laundering now needing to be done individually, they almost always end up returning the clothes to a laundry, and quietly returning to society as though nothing had happened. In those few cases where individuals hold out for their entire lives, the clothes are simply reclaimed upon their death. In rare instances, some small familial groups have established long lineages of holding on to hoards of checked out clothes. However, much of what they know is the library model, and seeing its practicalities, they often emulate its customs and systems. Having no input aside from their own craft, they care for the clothes just as diligently. Within a few generations, they become indistinguishable from the collective laundries and libraries around them, and begin to slowly open exchange and public services. These more isolated library systems do tend to create new systems and innovations in storage, sewing, distribution, and laundering, so, in this way, those who dissent become great contributors to library society. On the scale of time, their return is as blessed as any return to the collective while.

The same principle is applied to any area within the whole that does not seem to be in alignment with the usufructian values. There are those materials that seem more time or labor intensive than their fibers or substance could possibly be worth. However, to a utopian, one who views all society on the great scale of the fullness of time, it is known that ease comes through careful work, not through abandon. The ecologist knows that it is complementarous diversity which brings ecosystemic tranquility. The anarchist knows that it is noncontrolling complexity, each acting in their best towards a shared future, that drives all of reality into collaboration. Each being all three, they clothe themselves not just in the simplest of fibers, which are easiest to mechanize, have the most history and example, and are most comfortable. With such a great portion of labor assuaged, and such a great portion of discomfort brought low, these people find themselves with extra tolerance to bare labor, and extra tolerance to bare discomforts, and they measure these tolerances out and find ways to use them towards the greater social good, and the greater good of themselves. If there is a great waste in hickory nut shells, for instance, one may practice methods of grinding them down into a fine powder, and pressing them with adhesive to form the shape of a sandal. This is not ideal for daily wear. It is too hard and uncomfortable. But the wearer finds themselves building familiarity with the material, seeing where it chips and what surfaces it is assistive to walk on. This process is intended to be personalizing and generative. Even if hickory nut shells never become a meaningfully useful clothing material, their temporary adoption as such allows individuals to build a relationship with them as a material, and explore what they could be used for. All things and all people have their place in the society; so long as careful attention is given, with understanding of needs, through personalization and diversification of the relationships that are had with them.

The society is not, however, in any lack of materials. There are a great many fibers grown in the great many biomes, and much of global dispersement of goods is in textiles, used as packing inbetween medical components and other fragile specialities, and bedding in the rooms of travelers. The great diversity of communities - and the uniqueness of each bioregion- leads to a multitude of fabric fibers, an abundance of processing methods for each, and then still a great many more use cases constantly being developed and discarded and elaborated upon. The many cotton species in the world are referenced in guides for their strengths and weaknesses and sourcing and abundance. Yucca, nettle, wool, cashmere, linin, seagrass, straw, mulberry bark cloth, jusi, silk, river cane, and hundreds more are grown in mixed ecological systems around the world, mostly in their places of origin or long term cultivation. This variety means that crop failure, blight, or other disruptions in one area do little to depress the collective supply of textiles.

To avoid species invasiveness, new crops are introduced slowly and carefully into the ecology of desired regions. The primary focus of new introductions is to provide redundancy in local and regional food systems, ensuring that all nutrients are available in multiple forms at every time of year, preempting crop failures, and ensuring that allergies and other health conditions can be easily dietarily accounted for. However, the longscale nature of society, and the ability to selectively breed native crops towards different seasonality, nutrition, and shelf ripening, often mean that there is little desire to import new food crops. Many ecological maintenance systems are built to expect new species introduction every generation or so (with some more fragile ecosystems being on much longer time scales). While crops suiting some ecological niche besides food are also often needed, such as to hybridize a beloved blighted local species, there still, on the grand scale of time, comes moments where the opportunity to naturalize a new species for the explicit purpose of human use and human joy arises. In these moments, new base fibers for textiles are considered by the sortion selected councils and ecological research syndics, and occasionally are selected.

The clothing arts, being widely shared and thoroughly understood practices - weaving, stitching, drafting, patterning, grommeting, buttonholing, thrashing, and all the rest - all help form the shared cultural motifs by which metaphor, aphorism, and wisdom can be drawn. Young lovers first separating compare themselves often to the grommetted panels of the common overdress; coming apart, fitting together, finding their way into new patterns that suit the body. To unfold one's skirts can mean to be growing, or otherwise, to be seeking more warmth, both emotionally and practically. Similarly, to raise one’s skirt often means one is preparing for hard work, acting unencumbered and uninhibited; tho sometimes it can take on other, more sensual meaning. In the great stories of the many peoples, one often finds motifs of dress demarcating the overall plot of the story, giving character insight, or implying new layers of rich meaning. This shared understanding of material culture is often generative in individuals' attempts to further interpret their own experiences, and in the describing and shaping of relationality between one another.

In this metaphorical approach, it is said that all reality is the fabric resulting from the tension of the threads of dialectical synthesis; overlapping and informing and supporting one another. Physics is the loom. Society wears the fabric. Individual consciousness is the act of looking in the mirror. Social consciousness is the act of looking over the fabric to see how it is made, and to understand its construction. To darn is to reform. Revolution is the act of changing the drape of the fabric, often requiring the ripping of many seams, experimentation, and many practiced and skilled hands to sew it up right.

The richness of metaphors that arise from such a multi-skilled population is a driving force for innovation and communication. Familiarity with the methods of weaving allows for consistent innovation in data storage, requiring less and less resources to store more and more information, which further feeds back into the accessibility of reference material for further garment drafting. The fine motions of needlework teach movements of the hand that carry forwards into music, facilitating unique styles of plucked tremolos, allowing those so inclined to play and bring joy to the laundries with their sweet songs. Experimentation in waterproofing outerwear and soft shoes has led to the invention of canvas boats, as well as patches that can be applied to fix leaks, further assisting in the safe and ecologically sound transport of materials.

All aspects of the society overlap to form a cohesive and coherent whole. Each process is entangled with one another. The waste from one becomes the bedrock of another. Each skill learned in the pursuit of a task is then applied to the next task, and each lesson learned in the specific is then analogically applied to the general.

The society is clothed together in the great cloth of interdependence, woven in the ten thousand strands formed by the tensions of material life. It does not come to pass without thought, or planning, or intention; just as a length of flax left loose will tangle. But together, each giving and using, but none destroying, all are cool in summer, warm in winter, and cozy all year round.

#anarchism#rose baker#text post#clothing#historical costuming#utopia#library socialism#speculative fiction#anarchy#leftism#socialism#library of things#usufruct#social ecology

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

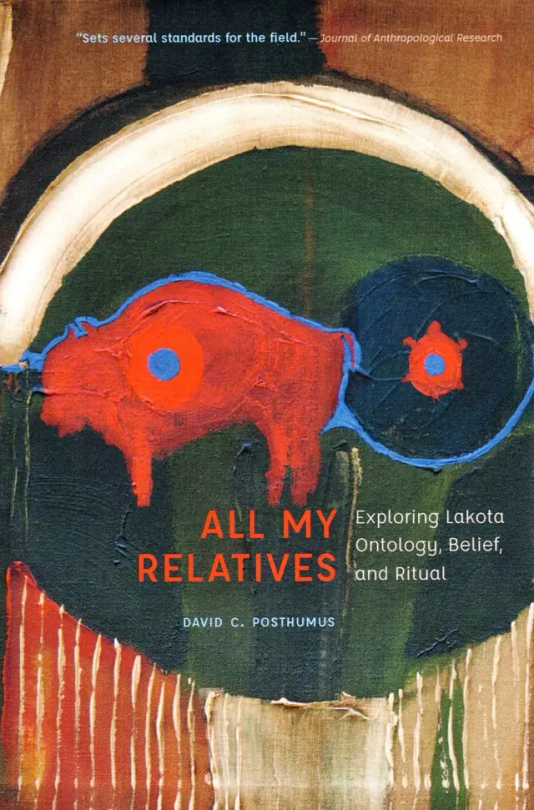

All my relatives: Exploring Lakota ontology, belief, and ritual. Posthumus DC (2022)

This is a book all about Lakota traditional beliefs and therefore has a lot of information connected to Mitakuye Oyasin. “At the heart of both Lakota religious continuity and innovation is an underlying animist ontological orientation, a basic way of seeing, understanding, and being in the world that extends personhood— in the form of a soul or spirit— to nonhuman life- forms.” This is expressed with ‘Mitakuye Oyasin’ –meaning ‘all my relatives’ or ‘we are all related’, which refers not only to human kinship but also to the relationship shared by all life-forms, both human and nonhuman, and the reciprocal obligations, responsibilities, and mutual respect that naturally extend from it” (14).

This repeats much of the ideas from similar definitions: belief in the connection between all life, relationships, the power the phrase has. It also gives a lot of words to help define these beliefs in academic language. Another important thing to point out is the way mitakuye oyasin is recognized as being part of Lakota innovation; my goal here is to use mitakuye oyasin to an innovation of queer ecology–hopefully add to the conversation.

“The normative cultural values encompassed by mitákuye oyásʾį are the very foundation of kinship, relational ontology, and the overarching interspecies collective, of which humans are only one hoop, one oyáte ‘people, nation, tribe’, in the company of many others. The key constituents of this animist ontology and worldview, of mitákuye oyásʾį, are persons, a category that extends beyond human beings to nonhuman or other- than- human persons. [...] Importantly, the Lakota worldview sees humans as the least knowledgeable and powerful beings, requiring the most aid and pity, upending the common Western biblical assumption that humans have dominion to rule over all other life- forms and subdue the earth (see V. Deloria 1999, 50; 2009, 99– 100). For the Lakotas, the seed of all life is wakʿą ‘sacrality, mystery, divinity’; ́ hence all life- forms share a generalized interiority, whether human or nonhuman.”

This is important information to support my argument. Queer ecology is very critical of Western beliefs and dichotomies that separate humans from nature and thereby present mankind as the ultimate lifeform (anthropocentrism). There are many essays and articles that examine the influence Christianity has had on the colonialist project (Gaard is the first that comes to mind). The Lakota worldview of being the ‘younger siblings’ of creation are supported by science in that ‘humans’ as a 'species' haven’t existed all that long in comparison to other 'species' and like many indigenous cultures, Lakota people knew the key to knowing nature was to learn from the world around us, as the author later confirms:

“Deloria explains that “the oldest traditions say that humans learned politeness and courtesy from the animals. . . . Generations of elders had already observed the behavior of birds . . . and decided that emulating them was the proper way for humans to act” (V. Deloria 2009, 123). Standing Bear (2006a, 56) substantiates this, writing, “The Lakota enjoyed his association with the animal world. For centuries he derived nothing but good from animal creatures. From them were learned lessons in industry, fidelity, and many virtues and much knowledge.” (50-51)

In the author’s footnotes is Vine Deloria’s examination of mitakuye oyasin that is, I feel, a great support of my claim:

“Vine Deloria refers to mitákuye oyásʾį as the ‘Indian principle of interpretation/observation,’ calling it “a practical methodological tool for investigating the natural world and drawing conclusions about it that can serve as guides for understanding nature and living comfortably within it. . . . We observe the natural world by looking for relationships between various things in it. . . . This concept is simply the relativity concept as applied to a universe that people experience as alive and not as dead or inert” (1999, 34). (Posthumus 2022 p219 f)

Queer ecology’s goal in many ways is to critique the ways the Western scientific paradigm has created inequity. Many are seemingly searching for solutions and answers to the problems that have been perpetuated by the colonial empire, supported as it is by western science.

While we must always, always be careful of appropriation and misappropriation–I contend that the solutions are not ones that need to be ‘discovered’ or solved in the way that Western science is so often searching for–advancement, the future…but rather, the answers are in what has always been there…and it’s simply a matter of observation.

#queer ecology#mitakuye oyasin#queer theory#ecofeminism#critical ecology#colonialism#all my relatives#lakota#indigenous studies#postcolonial theory#ecology#science#traditional ecological knowledge#queering ecology#ecosystems#environment#social ecology#long post

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Humanity is nature becoming self-conscious." -Élisée Reclus

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

A really good, albeit not in-depth, summary and introduction to Bookchin's ideas.

Highly recommend listening if you're at all interested in ecosocialism or green anarchism

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

He talked about returning so many things to the hands of the people, like economic power. He thought that the economy needed to be put in the hands of bottom up, self-governing bodies based on the assembly. He wanted technology to be decentralized—he would have loved Apple computers, maybe not the company, but the decentralization that the laptop computer brought about was just remarkable to him. He wanted automation to be small scale. It was about decentralizing and breaking up cities to small-scale cities that are integrated with agriculture.

So, the theme that I found when I was working on the biography was so many of his ideas were about decentralizing different parts of society and reintegrating them into a new whole. I call it eco-decentralism in the book, but that’s not a term he used. It was decentralizing for the purpose of restoring control to people. When I looked at what happened with him and anarchism, I wondered, “Why was he attracted to this ideology that he later broke with?” When I read his actual reasons for embracing anarchism in his earlier writings, I noticed that it’s because the state makes people passive. He admired that active political engagement in the Athenian polis, where people could actively be involved in their society, rather than be passively turned into anonymous faceless crowds of the New York that he was living in.

And I think, regardless of what you think about anarchism or not, that’s something that we need to preserve from him. He agreed with Aristotle that we are political animals and we need to engage. That was, I think, one of his main driving features was to create the engaged citizen, engaged at the local level, and in the surrounding regions, instead of just turning over their minds to the state.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is no greater act of terror that any human has ever done than the systematic destruction of ecosystems perpetuated by the ruling classes, capitalists and those who defend them.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 40-year study links Amazonian deforestation to reduced Tibetan snows and Antarctic ice loss. Both carry serious consequences, respectively, loss of nature’s water towers for millions of people as sea levels rise everywhere.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Get Organized!

I recently made a post about how to get started in doing radical stuff. Said otherwise, that post was meant to answer the question, “Where do I go, when I know the world is fucked?” This post covers similar ground, but is more interested in the theoretical side of things. Not to say it won’t be practical. It’s just saying that if you’re not the kind of person that can read a little bit and feel confident to act, or you like having a little bit more scaffolding, that you also deserve a resource. I’m hoping to contribute to that today. As the title says, we’re going to be focusing on organizing. This is one of those things that is said a lot, but is actually defined much less often. Tangentially, you should be aware and ready for this for literally everything relating to politics. Any word that you hear used, you should always ask for a definition. Many a movement would have gone differently if folks spent more time trying to find semantic alignment. Anyway.

When I say organizing, I mean catalyzing the energy of folks, acting from a specific theory of change. A theory of change is a thought process or method to create some kind of social impact in a particular context. When the world sucks in some particular way, and you want it to stop sucking, the answer is to organize, in the way defined above. By organizing, we lean on the idea of collective power to create changes that are currently only afforded to those with authoritarian power. It’s a game of evening the odds.

I will also note that this assumes that you are going to be framing your work around broad-based movements, that have (mostly) aboveground (as in “legal”) tactics. This is not necessarily a statement of what is correct; small groups that are in concert with larger movements are also able to be successful, even when doing more confrontational tactics.

So, to organize, I’d say it would be useful to be involved in movements already. You can look at my radicalism 100 post to see how that could look. Either way you have to know what your where your niche(s) lie. In other words, what sits in the middle of the intersection between what you like to do, what you are good (or can become good/have a willingness to become good) at, and what is needed in your context. I tend to center the local level, because that is the area where influence is more tangible, and fits into how I see a resilient world coming to fruition. So, you have to ask yourself, “What can I do, that I would enjoy doing, in my community?” Then, you should find some other people who are in that same vibe. Depending on your approach, this may take no time at all, or a lot of time. I listed some ideas for finding folks in radicalism 100, but to reiterate: look for social medias and IRL presences of people who are into the same topics, and connect with them. See where you can plug in, and see where the contours of organizing in your local contexts are. Ideally you can see places where gaps can be filled.

Once you find an issue that you think has potential, and you have a couple of people to do some organizing with, you have what I think of as a catalyst group. This group is meant to start (or assist) in a certain kind of reaction, but not lead it. Trying to control movements is both futile and antithetical to liberation. So, to ground us, we have two very important ingredients: a topic/issue/area of focus to organize around, and a group of folks to work with. Once this is in place, you can co-create a strategy with your organizing team. I’d recommend employing an encircling strategy as your long-term or meta strategy, where multiple sub-strategies and campaigns happen within this frame. Essentially, this allows you to employ campaigns across a matrix of tactics. Within the encircling frame, you can create a campaign (what I consider a “short-term” strategy). Campaigns are a series of actions over time. Strategies are a series of campaigns over time.

A useful way to think of strategic planning is by separating the process into stages, grouped by movement size.

Small: Organize small actions/protests, figuring out ways to build movement visibility and interest

Medium: Focus on scaling up the participation, through mobilizing efforts. Promote your actions, get people involved, and encourage meaningful action.

Large: Create a movement. The kind of thing people hear about.

To organize on the smallest level, the easiest thing might be to just do plan actions that are well within your team’s capacity, organize those actions, and execute. If you can swing it, I’d really recommend to not lean too much into symbolic actions. There are risks with every action, no matter what legal frameworks your locality has. If you’re going to do something, you have to be very intentional with:

what you hope to accomplish through the action

a high likelihood of success for the action

doomsday planning in case something goes wrong

If you’re able to do this, then you will be leagues ahead of a lot of other folks. This is not to make it a race or a competition, but it is moreso to say you can symbolically represent and catalyze action without becoming a martyr.

As you’re doing actions, you should be refining your idea of who’s impacted by the issues more and more. As that picture gets clearer, you should spend more and more time understanding and listening to those folks. Ideally, you get to a point of co-creation, where you are enabling people to fight for themselves and build their autonomy. That is the kind of thing that prevents movements from dying. Organizers should be trying to put themselves out of business, in a sense. Catalysts should be able to come from anywhere.

To scale up, I’d recommend a focus on meeting folks. Take the ideas of deep canvassing, where you empathetically have conversations with whoever is impacted by the issue you’re responding to, through the lens of giving power to those people. Rather than asking them to feed into some established system of power, encourage them to take action into their own hands, as a collective.

I’d also recommend that as capacity grows, build a “positive” or “constructive” power. This can look like a lot of things. Whether it is a block club, neighborhood pod, community council, or community assembly, dedicate energy into creating spaces where people can start building their democratic and consensus muscles. These can simultaneously act as the training ground and alternative governance structure that allows folks to start making decisions for themselves in a very specific way.

This will ideally allow the movement to really start to be intersectional. It should be intersection minded from the outset, but that can be difficult to meaningfully actualize in the early stages of the movement. since single-issue movements are inherently brittle (if your movement revolves around getting something on a ballot, winning or losing just ends the movement)—there are throughlines that connect all movements, and those lines should be made visible and traveled. Environmentalists should fight for housing rights, LandBack, Reparations, and a host of other things. The more developed our networks, the stronger our movements will be.

#economics#economy#econ#anti capitalists be like#neoliberal capitalism#late stage capitalism#anti capitalism#capitalism#activism#activist#direct action#solarpunks#solarpunk#praxis#socialism#sociology#social revolution#social justice#social relations#social ecology#organizing#complexity#resist#fight back#organizing 101#radicalization#radicalism#prefigurative politics#politics

264 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Then & Now -- "Our Consumer Society"

Fantastic analysis of consumerism and its historical/political context.

This ought to remind us why anti-capitalist critique must go beyond mere deconstruction of the status quo; it must also reawaken authentic self-directed desires in people (desires not fostered by a top-down advertising apparatus), and be a creative force that builds a new world in the shell of the old and actively de-alienates us. ("De-alienation" is a central piece of the post-capitalist puzzle, alongside de-colonization and de-growth.)

Situationism posits that this is possible through situations -- broadly-defined communal moments throughout life where people are no longer confined to capitalist realism and other oppressive mind prisons imposed from above, and where life can be experienced as a convivial adventurous flow state with others in a self-directed radical democracy. Social ecology speaks a lot about needing a playful desire-based society in a context liberated from consumerism, where work becomes play and where organic desires strike a healthy balance between individual pleasure and collective joy.

The end of capitalism will mean a lot fewer manufactured gadgets and gizmos being pumped out every year, and it will also mean a "bottom-up" reclamation of desire and leisure and public space. Let's hope we can defeat it before climate change makes the planet largely unlivable.

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Defense Of "Anti-Work"

Many people attempt to justify Neo-Calvinist Work Ethic, which is a self-contradicting piece of pseudo-religious dogma stating that all people must work for religious purposes, but not equally. The philosophy also pushes the belief that the wealthy inherited the earth and became wealthy only by way of innate virtue and should only perform unburdened laborless management and collect the majority of the wealth produced by others, and that the poor must perform hard labor and hand the money up the societal ladder to save their souls.

Early Calvinist Work Ethic dogma was used as a justification for serfdom and slavery from the late 1500s (AD) till today. Neo-Calvinist ideology forms much backbone for much of gatekeeping in Western society; as it is related to System Justification, victim-blaming and "societal weeding".

Contrary to current Western common belief, most of the world didn't belive in anything even remotely close to this concept until fairly recently. While serfdom and slavery had existed in pockets and within waxing and waning empires (with various restructuring of labor beliefs and practices), it wasn't part of a universal belief that humans were required to access the resources of the world they were born on solely through repetitious labor associated with pyramid'esque-scheme systems.

In fact the "work week" wasn't invented until the 1800s and the idea of standardization of Brute Capitalism didn't exist until the 1950s (which lead to economic downfalls and crime waves during the 1960s and 1970s).

People often assume that the majority of the world's idea of work and taxes has been standardized for millennia, and pretty much look the same across all of history, but this is simply not true.

---

Side note: The anti-work isn't a movement in opposition to task completion, but in opposition to fallacies associated with ideologies that claim human beings should naturally be treated as machines used for repetitious labor in order to support classist structures and to restrict social and economic mobility.

The current systems aren't about maximizing everyone's potential, nor about focusing on justice and accuracy.

It's simply about creating and maintaining a series of networked exploitation-focused pyramid schemes. This is ensured mostly by way of early indoctrination, and encouraged via peer pressure (pride, shame, etc).

#antiwork#history#world history#capitalism#communism#socialism#economics#epistemology#slavery#serfdom#money#living#sociology#social ecology#humanism#social mobility#economic mobility

17 notes

·

View notes

Link

It is the relation within the human and the natural and the god and the geese and the past, present, future, body-self-other. A queer ecology is a liberatory ecology. It is the acknowledgment of the numberless relations between all things alive, once alive, and alive once again. No man can categorize those relations without lying. Categories offer us a way of organizing our world. They are tools. They are power.

The field of queer ecology has a HUGE overlap with solarpunk values, theories, and goals. Of course the solarpunk movement must be inclusive of queer people, but it must also account for the queerness of what we call nature and the environment. We must also be able to queer our own perspectives: What borders and boundaries are we constructing, who/what do they effect, and how? Here’s a good primer on one thing that queer ecology can mean.

#solarpunk#punk#queer#queer ecology#social ecology#solarpunk movement#activism#lgbtq#ecology#environment#nature#article#link#original post

141 notes

·

View notes