#tEchNicalLy

Note

joel smallishbeans, or like jizzie even :point_right: :point_left:

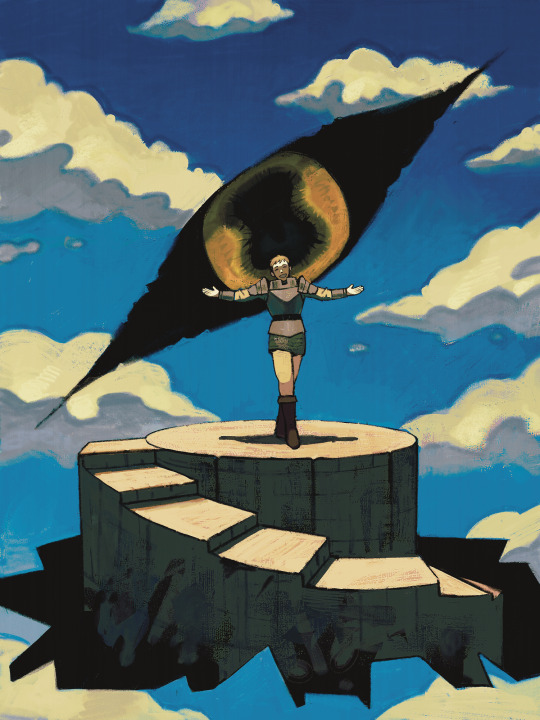

inspired by jc leyendecker

#my art#mcyt#hermitcraft#technically#if it works it works#lizzie ldshadowlady#ldshadowlady#joel smallishbeans#smalishbeans#jizzie#hc joel#request

979 notes

·

View notes

Text

DPxDC Prompt #8

Danny was practicing shapeshifting with Amorpho when he felt the tug of a summoning and heard the distant words drifting into his mind.

Normally Danny would just ignore it. Or if it seems like this was a group that needed some sense scared into them, he'd shift into his Horror form and terrify them into never pulling this shit again. But then he heard them mention live sacrifices, and Danny just had to step in before that happened. So he let the summoning pull him on through, briefly forgetting he was shapeshifted into a... less than ideal form.

Danny lands in the circle right on top of one of the intended sacrifices, a group of people in weird outfits and, is that guy green? Irrelevant. Immediately Danny on knows something is very wrong. His powers feel muted and far away. His form suddenly feels, locked somehow.

He casts his gaze across the summoning circle and, to his horror, recognizes the binding ritual. These cultists wanted to bind and seal him in one of these mortal's bodies after they were sacrificed. But they fucked up the spell. Or maybe Danny fucked it up by coming in too soon? Irrelevant again.

What matters is the spell went sideways. Instead of locking Danny into one of the sacrifice's bodies, it locked him into his own form while pulling most of his abilities just out of reach. Now he's here. In the shape of- He's stuck as-

"Dude, is that a pigeon? Did the Ghost King, like, send you to voicemail?"

#DPxDC Prompt#DPxDC#technically#DPxTeen Titans#The tv show version#With Robin Starfire Cyborg Raven and Beast Boy#I've seen a lot of Danny shapeshifted as different animals prompts#Cat bat duck goose dragon raccoon seal#Don't think I've seen pigeon though#And I got the line 'Did the Ghost King send you to voicemail?' about Pigeon!Danny showing up in the Ghost King's summoning#And I just had to throw that out here#Also Danny is supposed to look like a normal pigeon here#Maybe some slightly odd coloration#But part of the shapeshifting practice was learning how to shift into something that would pass for normal in the Mortal Realms

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am obsessed with ghost king Danny but specifically like spooky inhuman monster ghost king Danny so here is my interpretation. I love like serpent or biblical angel ghost king but like hear me out- sphinx kitty ghost king Danny!!!

#my art#beetlelemonade art#danny phantom#dp#ghost king danny#ghost king au#technically#dp x dc#cause I want to use this design in a dp x dc fic#I have so many thoughts on this design btw#like a million thoughts

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

tiny dnp

#phan#dan and phil#dan and phil games#TECHNICALLY#dnp#dpgdaily#daniel howell#phil lester#dnp gifs#fetus dnp

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

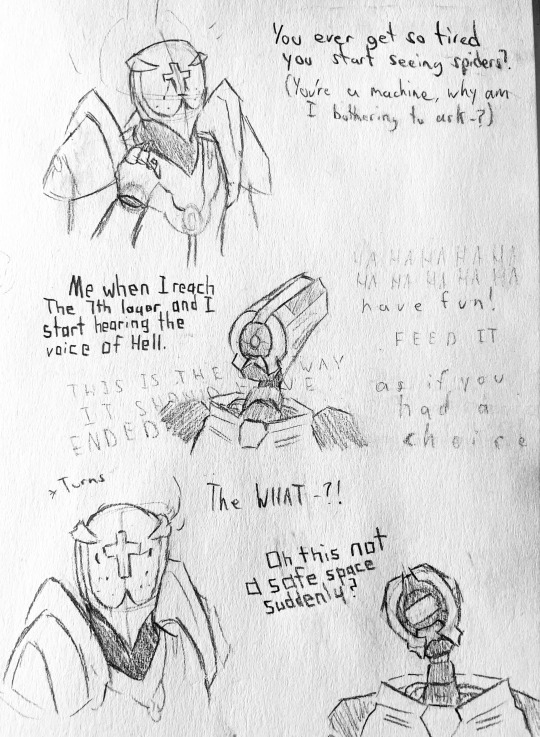

I did a thing while on call with a friend. I thought it was funny plus it gave me more motivation to try drawing V1 again (this time I used references :D).

#my art#fanart#ultrakill#ultrakill fanart#gabriel ultrakill#v1 ultrakill#ultrakill v1#v1#v1 fanart#gabriel#ultrakill art#ultrakill spoilers#technically#shitpost#meme#meme redraw#traditional art#traditional illustration#traditional sketch

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

and um what if Nacho looked a little like q!jaiden what if theylooked like her and

#qsmp#qsmp fanart#qsmp nacho#qsmp cucurucho#qsmp jaiden#technically#anyways q!jaiden reincarnated believers where you at#lovepups silly art#cw eye contact#imso silly about this egg!!!!

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hmm hmm

parallel, me think 😏😏*falls on the ground, Vomiting and crying*

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

i am once again: chiss

#swtor#chiss#swtor art#imperial agent#chiss ascendancy#artists on tumblr#character art#oc art#vi’rialla#sketchy#semi wip#technically#vi#star wars art#star wars the old republic#chiss art

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is who’s sitting in ur lap. Btw

#congratulations you have rabies now#souls in the sand#sits#my ocs#rue#I guess#technically#souls sillies#souls ask#myketheartista#art escapades

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think at this point I've headcanoned the gaang sexualities/ gender identities so hard that I forget it isn't canon. Like what do you mean Sokka and Zuko aren't bisexual? What do you mean Katara isn't pan? What do you mean Toph isn't aroace and had kids? What do you mean Suki isn't bi with a preference towards girls and doesn't go by she/they pronouns? What do you mean Aang isn't celibate and doesn't go by they/them pronouns? It's real in my head and that's all that matters.

#atla#avatar the last airbender#sokka#zuko#katara#toph#suki#aang#the gaang#anti kataang#technically#he's a monk idk what to tell you

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

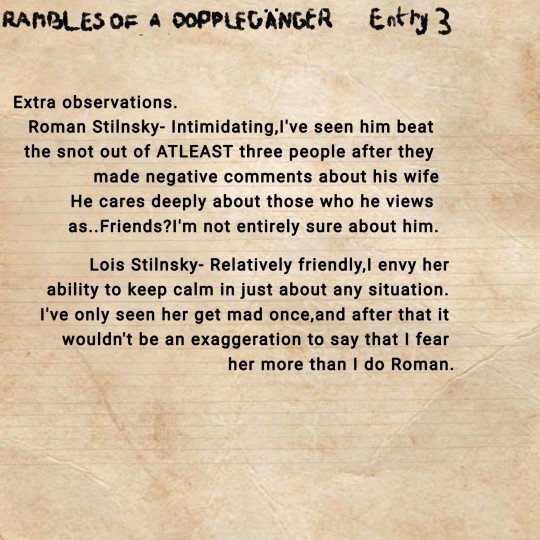

RAMBLES OF A DOPPLEGÄNGER

-Hyde likes doodling the neighbors. It helps him memorize their faces.

-He's scared shitless of both Stilnskies(?)

#he's scared of like 40% of the residents to be fair#either scared or creeped out#this is deadass just an excuse for me to draw the neighbors lol#tnmn#tnmn fanart#tnmn oc#technically#thats not my neighbor#roman stilnsky#lois stilnsky#Rambles of a dopplegänger

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

needing affirmation

#should i have a sheduled tag#...nahhhhh#just assume i am always awake#sth#Sonic#sonic the hedgehog#miles tails Prower#miles prower#tails#tails the fox#tails prower#soncic#sonic & tails#amy#amy rose#amy the hedgehog#sonic & amy#shadow#shadow the hedgehog#sonic & shadow#my art#technically#toki drawz

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

I havw never had artblock so bad . Hi guys

#fuucckk my life i hate everything#.art#this is my blog and i will vent as much as i want#i loev u all#spamano#technically#idk how ill develop thos#hetalia#hws romano#lovino romano vargas

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Comes Naturally

Fandom: The Silmarillion

Characters: Indis, Miriel

Summary: Two queens of the Noldor discuss motherhood.

Length: 2.9k

AO3 | Pillowfort | SWG

“What a trial motherhood was,” said Míriel in the understatement of several Ages, leaning back with a huff, so that she almost knocked Indis’ nose with the back of her head. “Not that you would know.”

“Not that I would know?” Indis echoed, her brows arched. However, she refrained from further remark, and Míriel elaborated. Since Míriel’s return, Indis had gathered that at times, Míriel would give explanation only if you kept quiet. (Other times, she would explain regardless of whether one wished it or not, but this was likely only with technical matters. On Míriel’s first day in the palace, Indis had received a three hour lecture on the function of various parts of a loom after fatefully inquiring how Míriel found her old tools.)

“Well,” said Míriel, and despite her dismissive tone, Indis felt something rawer in her voice now, facing away from Indis, than she had heard from her all that day, more even than when she’d had Indis’ hands between her legs. “Elfinesse the realm over praises your sweetness and care; I assumed that motherhood and nurturing came naturally to you.”

�� Indis resumed combing through Míriel’s sleek silver hair. Beyond the open windows, a dove whistled. The rest of the house was still and relaxed in the warmth of the sunlight as the day eased towards evening; perhaps the slowness of the day had led to this thoughtful (for so it was, even if Míriel feigned otherwise) conversation.

“Perhaps,” Indis allowed slowly. “Though ‘naturally’ does not mean ‘wholly without effort.’ The joy of it came naturally, certainly.” Míriel said nothing else, and Indis, with great restraint, held back from probing or trying to change the subject.

“For my part, I believe pulling teeth would have been a simpler and more rewarding task,” Míriel said at last into the silence of the bedroom.

“Surely it was not so terrible,” Indis objected, then cringed. Míriel snorted mirthlessly.

“Whatever Finwë told you of my efforts, certain I am that he was kinder to me than I deserve.”

Indis worked carefully through a small knot near the ends of Míriel’s hair. “You were ill, Míriel,” she said gently, at length. Míriel grunted.

“Yet still I was a terrible mother,” she said. “Even Fëanáro knew it, though he has since forgotten.” Indis opened her mouth, but Míriel silenced her before she could get in the air to disagree. “He always preferred Finwë,” she said. “Even as a babe in arms. How he wailed when I held him! And nothing could I do to calm him! At times I thought at the least he would eventually tire himself and then be content, but he seemed to have an endless reserve of energy for screaming, and the volume!” Míriel winced. “He could drive me to tears for want of a moment of quiet! So of course in the end I would give him over to Finwë, and it seemed at once he would be smiling and reaching out with his little hands and laughing! I cannot recall that he ever laughed for me. He must have, I suppose, but I…” Míriel trailed off, almost confused. Indis was not sure if her memories were muddled by virtue of her rebirth or the illness which preceded her death, or both.

“Finwë had a way with children.”

“I was told and told and told how naturally motherhood came, once the babe was born,” said Míriel, and Indis could picture the wrinkle of her flat nose. “Naturally! Not to me, but to Finwë, certainly. He seemed always to simply know what Fëanáro wanted, and if he did not, he would figure it out, or find some suitable substitute.” She shook her head.

“You would have come into it,” Indis insisted. “If you had had the time. You would have learned.”

“Perhaps. But if I must learn, then it was not natural.” Doubt shadowed her words. Again, she fell silent, and Indis forced herself not to fill it. Early evening light slanted through the windows, turning the mantle to gold, lighting up the dust motes floating around the bed curtains. Míriel lifted a hand as if to chase them with her touch; there were still times when she seemed amazed to be in the world again, to have physical sensations like touch and sight and sound (Indis, in the very new days, had found her by the fountain in the yard, weeping profusely over the sound the water made burbling up in the bowl of it, and often early she had touched Indis as if expecting her to dissipate beneath her fingertips.)

“I cannot say I was ever one who weathered failure gracefully,” Míriel said then, as Indis slid off the bed and went to the bottles and jars on her vanity. “I was failing at motherhood and I could see it, and I felt sure the baby and the rest of the city knew it too. And do you know? I resented him. I gave everything of myself to this child, and he would only smile for his father, and he made everyone whisper behind my back—or so I thought, I haven’t an idea if it was actually true—and even when he was quiet for me, he looked at me with these great accusing eyes as if to say he knew I was the worse parent.”

“Míriel…” Indis began uneasily, fingers lingering over the cosmetics. “Babies don’t…”

“I know, Indis, I know,” Míriel snapped. “But as you say, I was ill, and in my illness I was convinced this child whom I had given so much to bring into the world loved me not, nor would, and every day it seemed I could not escape my failures. I asked for him less and less; I felt the more I left to Finwë, the better for the child.

“Still he would come and see me, but even then I felt he disliked me. A-times I could hear him in the yard with his nursemaids, running and shouting and laughing as children do, but when he came to me, he had to play quietly, or not at all, for Mother’s head hurt, and Mother was tired, and Mother needed to rest. What joy is there for a child, sitting in a dark sick-room with a feeble shade of a woman who never knew how to be a mother?” Míriel lapsed into silence, scowling.

“You know he loved you,” Indis said quietly, returning to the bed with a small vial. She dabbed a bit of osmanthus oil from the vial onto her fingers to brush through Míriel’s hair. “You were his mother, and he loved you without thought for your condition.”

“What does a toddler understand of love? They know only safety and joy, or the absence of them. Love? What complexities of love could be grasped by such an infant? He knew that his father made him happy, and I did not; for him, what deeper considerations could exist?”

“I disagree,” Indis said. “I think he loved you even then. Perhaps he did not understand it, but he did.”

“Truly you think a babe can comprehend some notion of love?” Míriel asked, twisting around to look in skeptical astonishment at Indis.

“I do,” she said firmly. “Truly you believe they cannot?”

“A child who can barely string together a sentence, know love? Next you shall tell me mice and horses know it!”

“Must one be able to articulate the feeling to feel it?” Indis asked.

“I believe one must be able to understand it!”

“I disagree,” was all Indis said.

Míriel shook her head. “Yours is a gentle spirit I think,” she said. “Better not to comprehend an absence of love. I see why Finwë chose you.”

“Gentle, perhaps, but I should think not naïve,” Indis replied with a hint of an edge. “I do not speak out of blind hope, Míriel.”

Míriel regarded her a moment, and then said: “No, I did not think so. I would not accuse you of that. Perhaps it is only that I have grown cynical. No—perhaps that I always was.”

There were things Indis could have said then—about the vain effort of cynicism to protect a weary heart, about Míriel’s struggles, about the necessity of not closing oneself off to feeling—but instead she just took Míriel’s hand and squeezed it.

“I will not say I have never felt it, for that would be a lie. But you were telling me of Fëanáro’s infancy,” she said, and Míriel nodded. Still she was quiet a moment, and Indis thought the interruption would be the end of Míriel’s sharing, but then she continued.

“Yes…the more my illness took me, the less reason girded my thoughts, as you can see. As my weariness grew, I convinced myself that I was doing him a favor; that he would, truthfully, be better off without me. One can always convince oneself that one’s desired course of action is also, coincidentally, the best for everyone else, isn’t it so?”

Indis bit her lip against the desire to interject that that it could never have been that Fëanor or anyone else would have been better off if Míriel were dead.

“What a little fool he was, too,” Míriel went on crabbily. “To think he had the fortune of a mother such as yourself walking into his life, and he pushed you away for want of me! I should pinch him if I could. The real tragedy would have been if you and I had traded places!”

“I think you are too hard—”

“All of that rather makes it sound like I cared not for him, doesn’t it?” Míriel let out another long sigh. “It isn’t so. He was the flesh of my flesh, how could I not love him? Or at least…in the beginning. At the end, I do not believe I loved anything. I had not the capacity any longer.” Indis was neither combing nor braiding, simply running her hands through Míriel’s hair in hopes of soothing her. “But there it is, you see? I think no matter how ill you were, Indis, you could not watch your children sobbing at your bedside, could not hear them begging for you to come home, to be a mother, and feel nothing.”

“I do not think you felt nothing,” said Indis quietly. Míriel’s shoulders tensed.

“Was it not near enough? Nothing he said, nothing Finwë said, would change my course. I broke his heart, and I knew I was going to do it. And out of sheer stubbornness, I refused to return once I had done it.”

“You were—”

“Yes, yes, I was unwell,” Míriel said forcefully. “And yet, I was myself still. I was not deprived of my faculties. I was aware of the consequences of my actions.”

“Such knowledge may become subordinated to extended pain and discomfort,” said Indis. “We are, after all, still physical beings. True thought is difficult when one’s mind is focused on the struggles of the body.” When Míriel said nothing, Indis added: “I know not that I could have done otherwise in your place. I have never felt as you did then.”

“I feel quite assured you would have borne it with more grace.” Míriel’s tone was breezy, and Indis could not discern if there was something heavier beneath it or not.

“I know that you bore it a long time,” said Indis, beginning to weave Míriel’s hair into a set of braids. “I tend to doubt very much I could have managed so long.”

Míriel leaned back slightly into Indis’ touch, relaxing a little. “It felt like a long time,” she murmured. “Stars, it felt like such a long time. It was only a few years. But it felt so terribly, terribly long.”

“I think ‘tis a credit to your love,” said Indis, “for Finwë and for Fëanáro, that you endured so long as you did.”

Míriel said nothing, and Indis worked the second braid down to the tie. She thought back to what Míriel had said earlier. It had never occurred to her, in all her morose anxiety that she would never live up to the exalted former queen of the Noldor, that there was anything Míriel might have felt similarly about, looking at Indis.

“I know you would have been a good mother to Fëanáro, if he had permitted it,” Míriel said at last. She twisted around on the bed to look at Indis. “And I am grateful, for what you did do.”

“It was not much,” Indis demurred. Fëanor had not allowed it to be much, and at some point, Indis had given it up as a lost cause.

“I fault you not for that,” Míriel said with a wry twist of her mouth. “When I died, I had hopes that Fëanáro would turn out to be like his father. Everyone likes Finwë. How could anyone not? In fact, I believe he was sometimes overconcerned with how well he was liked. And Fëanáro looked so like him, even as a child! Unfortunately, it seems he took after myself, and so I have great pity for you.”

Indis could not help but giggle at this, try as she might.

“I see you trying not to laugh,” said Míriel. “But you ought; ‘tis true. Finwë was liked and I was a bitch.”

“You were liked!” Indis exclaimed. “Even still, you have scant idea how the Noldor lamented your absence.”

“Mm. Liked, perhaps, but likeable? No, that was never me. If anything, I was liked in spite of myself. I never did understand why Finwë chose me.”

“He was amazed by you,” said Indis with a smile. It was good, when they could speak comfortably of their pasts this way, without rancor or injury. “That never changed. Nor do I disagree with him.” Míriel’s lips curved into a smile as well, softly fond, and Indis found herself saying: “Do you remember how he would smile, that one particular way, where you could just imagine what he might have looked like as a child?”

Míriel’s smile grew. “Yes, I know the look,” she said, flashing teeth. “Ah, but how he charmed me with that! He was a beautiful thing, wasn’t he?”

“I will tell you,” said Indis, “I saw it very rarely, but once or twice, I have seen Fëanáro smile that way.”

Míriel’s eyes grew distant, as if she were drawn into a dream, but her smile remained, close-lipped once more. There was such a silent ache about her that Indis could not resist throwing her arms around Míriel’s shoulders to embrace her from behind, squeezing her tightly as if to give physical reassurance that she was not alone. Míriel’s loose robe slipped down her shoulders at Indis’ touch.

“But he was clever like you,” Indis whispered to her. There had been a time when she could not have spoken of Fëanor this way, when her anger and bitterness against him overbore any of the sympathy she had harbored for him in his youth. Half of her children and all her grandchildren he had stolen from her, and never had he missed a chance to spit in her face if he could. Yet there had been a time too when she had seen the better in him, and empathized with his pain, and there was almost relief, in speaking of him with Míriel, in purging the acidity of her wrath. It did little good, she reminded herself, to dwell perpetually in anger, even if the object of it would walk no more among them. Nothing in her garden grew of her anger. “I saw it in the work you left behind. Your minds ran the same paths.”

“Pity the boy,” said Míriel ruefully. “And his father too!”

“I think neither of them would have had it any other way.”

Míriel put a hand over Indis’, and rubbed the back of Indis’ hand, slowly returning from that dreamy place where she at times withdrew to, as if her mind were still making sense of how much had changed since she last lived in truth. It was some moments before she spoke again.

“I understand he was difficult for you,” said Míriel. “And for that I apologize...I am still…still learning of the full extent of all that transpired…” Míriel’s voice had grown thicker, and Indis could catch a glimpse of the grief that the queen tried so doggedly to shield from view. “I spoke again with your grandson several days past; he told me a little more of the fortunes of the Noldor in Middle-earth…” A place they never would have been but for Fëanor’s rebellion. Indis knew that Finrod would be cautious in what he shared, but Míriel was sharp enough to fill in many gaps. She knew how much ruin had come of Fëanor’s actions, if she did not yet know every detail of it.

“And I have spoken a short while with his wife.” Indis had hoped that Míriel and Nerdanel might share something of a grief the rest of the Noldor were not keen in hearing of, but as neither of them was particularly inclined to spill their hearts to a stranger, she could not say yet if introducing them had done any good. “But ‘twas you that knew him in his youth. Could you—would you—tell me something else of him, of my son?”

“Of course,” said Indis, loosening her hold on Míriel. She eased back down onto the mattress and sat beside Míriel so that she could still hold her hand. “What would you like to know?”

“Anything,” said Míriel. “Everything.”

#miriel#indis#mindis#the silmarillion#tolkien tag#fanfiction#tolkien fanfiction#rocky writes#sapphictolkien#technically

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

in the kingdom of the blind the one-eyed are kings

#dungeon meshi#delicious in dungeon#mithrun#marcille donato#thistle#yaad#technically#laios touden#(not)#art tag

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Bad idea: Age gap discourse but in a fantasy land where there's multiple races who have vastly different lifespans and life styles.

Is it wrong for a 27 year old human to date a 140 year old stone elf, considering most stone elves don't get out of diapers till their 30s?

Is it wrong for a 80 year old dwarf to date a two year old fire wisp, when fire wisps only live up to 5 years (between the eruptions) and have memories of their past lives, so in a way they're "born" at age 400,000+? That octogenarian dwarf is way younger than the fire wisp that's only physically younger than some of the socks the dwarf has!

Is it wrong for a chronomancer who was never born to date, well, anyone? They are zero years old and infinity years old and negative one hundred and seventeen years old all at once. They look like an old human, sure, with the long white beard and the wrinkly skin, but as far as anyone can tell, they've always looked like that. We've seen the cave paintings.

Is it wrong for a 30 year old lizardman (that's old in lizardman years) to date a human who is 60 years old in biological years (because of aging spells), 26 years old in lived-experience years, but only 13 years old in calendar years? (ie, they were born 13 years ago, but spent some of that time in sideways timelines, so they've lived more years than have passed in their home timeline?)

Is it wrong for a 12,000 year old dragon date a pile of 400 kobolds when kobolds only live like 10 years on average, but reach full maturity in one year? And if you disagree, can you do anything about it? You do know what happened to the last policeman who tried to arrest a dragon, right? Their city is still smoldering, 50 years later.

Is it wrong for anyone to date the time worm? It's the same age, every year. So the age gap can only intensify. If you start dating the time worm when you're both the same age, when do you break it off because you've become too much older than them?

And most confusing of all... What about the fairies? They could be anything between a thousand and a day old, they would lie about their age either way, and they can look like whatever they want. There's fairies we know for a fact have been around since the founding of The City of Towers, who met the silent mother herself, and also look like they're at most ten years old. Is it wrong to date them, or just really uncomfortable for everyone who sees it? And on the other side there's fairies who are "born" (hatched? They come from plants, I'm not sure what the verb even would be. Seeded? Sprouted, maybe) this week who are already appearing like middle-aged men and dancing with widows in what looks like a scheme to run off with her fortune but they never take the money, because what would a fairy want with worthless metal discs? Maybe fairies have a hive mind or genetic memory or reincarnation with full memories, they'd never tell you or give you a straight (or consistent) answer anyway.

Stonefolk are really the only inter-race dating situation anyone can agree on. They're unthinking & unmoving solid rock during the day, so those hours don't count. Thus their "real age" is a nice even half of their true age. So if you meet a stonefolk who was dug out 30 years ago, watch out: that's a 15 year old, and if you're a 25 year human, that's too young for you, even though their dig-date is five years before your birth-date.

EDIT: 2024/01/12: Changed the name of the Stonefolk

16K notes

·

View notes