#war in afghanistan

Text

Much of the public discussion of Ukraine reveals a tendency to patronize that country and others that escaped Russian rule. As Toomas Ilves, a former president of Estonia, acidly observed, “When I was at university in the mid-1970s, no one referred to Germany as ‘the former Third Reich.’ And yet today, more than 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, we keep on being referred to as ‘former Soviet bloc countries.’” Tropes about Ukrainian corruption abound, not without reason—but one may also legitimately ask why so many members of Congress enter the House or Senate with modest means and leave as multimillionaires, or why the children of U.S. presidents make fortunes off foreign countries, or, for that matter, why building in New York City is so infernally expensive.

The latest, richest example of Western condescension came in a report by German military intelligence that complains that although the Ukrainians are good students in their training courses, they are not following Western doctrine and, worse, are promoting officers on the basis of combat experience rather than theoretical knowledge. Similar, if less cutting, views have leaked out of the Pentagon.

Criticism by the German military of any country’s combat performance may be taken with a grain of salt. After all, the Bundeswehr has not seen serious combat in nearly eight decades. In Afghanistan, Germany was notorious for having considerably fewer than 10 percent of its thousands of in-country troops outside the wire of its forward operating bases at any time. One might further observe that when, long ago, the German army did fight wars, it, too, tended to promote experienced and successful combat leaders, as wartime armies usually do.

American complaints about the pace of Ukraine’s counteroffensive and its failure to achieve rapid breakthroughs are similarly misplaced. The Ukrainians indeed received a diverse array of tanks and armored vehicles, but they have far less mine-clearing equipment than they need. They tried doing it our way—attempting to pierce dense Russian defenses and break out into open territory—and paid a price. After 10 days they decided to take a different approach, more careful and incremental, and better suited to their own capabilities (particularly their precision long-range weapons) and the challenge they faced. That is, by historical standards, fast adaptation. By contrast, the United States Army took a good four years to develop an operational approach to counterinsurgency in Iraq that yielded success in defeating the remnants of the Baathist regime and al-Qaeda-oriented terrorists.

A besetting sin of big militaries, particularly America’s, is to think that their way is either the best way or the only way. As a result of this assumption, the United States builds inferior, mirror-image militaries in smaller allies facing insurgency or external threat. These forces tend to fail because they are unsuited to their environment or simply lack the resources that the U.S. military possesses in plenty. The Vietnamese and, later, the Afghan armies are good examples of this tendency—and Washington’s postwar bad-mouthing of its slaughtered clients, rather than critical self-examination of what it set them up for, is reprehensible.

The Ukrainians are now fighting a slow, patient war in which they are dismantling Russian artillery, ammunition depots, and command posts without weapons such as American ATACMS and German Taurus missiles that would make this sensible approach faster and more effective. They know far more about fighting Russians than anyone in any Western military knows, and they are experiencing a combat environment that no Western military has encountered since World War II. Modesty, never an American strong suit, is in order.

— Western Diplomats Need to Stop Whining About Ukraine

#eliot a. cohen#current events#politics#ukrainian politics#american politics#warfare#strategy#tactics#diplomacy#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#war in afghanistan#vietnam war#ukraine#usa#toomas hendrik ilves

477 notes

·

View notes

Text

America was playing 3D chess by withdrawing and we were all just too dumb to see it

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

It Didn't Have to Be Like This (OLD ESSAY)

This essay was originally posted on September 15th, 2021, and is another one of those "nearly broke me to write" ones.

This essay reflects on the War in Afghanistan after the Fall of Kabul and all that entailed - leading to the Taliban regaining power in the country. Needless to say I have some complicated feelings on it.

(Full essay below the cut).

So.

Let’s talk about Afghanistan.

It’s hard to believe it’s been a month since Kabul fell to the Taliban, bringing down with it what was left of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Like with so many other things from the past couple years, it simultaneously feels like that event occurred only yesterday and also years ago, both at the same time. It was one of those events where time seemed to lose all meaning as you watched it happen in real time over the matter of a few days.

I had considered writing something about Afghanistan sooner, but I had decided to wait until the next monthly essay to do so, mainly because I was emotionally and physically exhausted both by those events and other events in my own life, but also because I was still mentally processing it and figuring out how I felt about it. I was still in elementary school when 9/11 happened and we first went into Afghanistan and we’ve been occupying that country for the majority of my life so far. Needless to say, watching the Taliban roll in produced a number of powerful, conflicting feelings – especially given how my politics have changed in adulthood.

I was actually struggling for a few days trying to figure out what exactly I was going to say about Afghanistan. Certainly, there’s been no shortage of think pieces and op-eds about big, brained columnists and pundits trying to score political points or cover their own asses and what have you (I’d give you some examples to share here, but I value my sanity and your own to inflict psychic damage of that caliber on you all so if you really want to see they’re not that hard to find). I wasn’t sure what I could contribute that would be different or of any value. In the end, what I decided to write about is centered around the phrase I’ve kept finding myself repeating to myself and others as I’ve watched Afghanistan disintegrate over the past few weeks and the United States and the West completely fuck up its endgame to a long, bloody, pointless war:

It didn’t have to be like this.

I keep finding myself thinking that both about the fact we went into Afghanistan in the first place, the way in which we went in after we decided we had to, all the decisions we made along the way, and then the way we left. I think about these things, and all the ways in which we made decisions and undertook actions disrupted, destroyed, or outright ended the lives of countless Afghans – as well as U.S. and allied troops – wasted countless resources, and other actions I may not even be able to comprehend, and think “it didn’t have to be like this at all.”

That’s the most frustrating, heartbreaking, enraging, depressing thing about watching everything unfold in Afghanistan now, as the Taliban establishes its new government as it attempts to snuff out any remaining resistance and is engaging in reprisals and punishments against those who had opposed it. The most frustrating thing as I watch people in my field that actually mean well – if maybe misguided at times – grappling with how the twenty years of blood, sweat, tears, riches, and more meant absolutely nothing. The most frustrating thing as I watch others who shamelessly plugged and supported the war over the years bend over backwards to explain how they weren’t wrong but were let down by whoever their favorite scapegoat has to be – Afghan soldiers who “didn’t fight hard enough” in the case of Joe Biden, apparently.

This was all so avoidable, in so many ways, to so many extents. So completely and totally unnecessary. And yet, we plowed ahead.

How very American of us, right?

Going In

I wasn’t quite old enough to really understand the invasion of Afghanistan. After the initial shock of 9/11 wore off, I went back to the pre-middle school age distractions of playing video games, building LEGO sets, and walking the dog. When we invaded Afghanistan, I didn’t even really know it was occurring until it was already almost over. Once it was over, I assumed that was that and proceeded to stop paying attention to it as Iraq eventually overshadowed it, until Afghanistan began to make its presence known again more forcefully some years later.

What I did understand – and still thought to a degree until a few years ago – growing up, was that compared to Iraq, Afghanistan was “the Good War.” While Iraq seemed so clearly to be unjustified and a bad decision to liberal-progressive households like the one I grew up in, Afghanistan was either seen as being “done” (at least in the early 00s), or even after it began to heat up more, it was still the war that was justified and necessary to embark upon given the events of 9/11. As time went on, we found other justifications for being there to build upon that “Good War” narrative that made Afghanistan somehow different from Iraq, whether it be promoting democracy, the rights of women, or what have you.

This is something I’ve grappled with and had to fight years of bias on as I’ve grown older and more politically self-conscious. The conclusion I tentatively arrived at only recently is that, while there are people who genuinely thought we were doing the right thing in Afghanistan and wanted to help, they weren’t the ones who made the decision to go in and the ones who made the decision to go in or engineered our long stay. Those people were decidedly not as idealistic and pure of heart and mind as some of the rank-and-file people I know who are torn up about Afghanistan. Those who made the call likely made it for far more cynical political reasons – both domestically and internationally – and committed us to something that did not need to happen.

Now, it was next to impossible to argue that the invasion of Afghanistan was unnecessary or even wrong back in 2001 if you wanted any hope of not being a pariah – or unless you were Congresswoman Barbara Lee and cast the sole ‘no’ vote against invading Afghanistan. But now, as a national security professional with the benefit of age and wisdom it seems pretty clear that to me that it wasn’t absolutely necessary. There were multiple, direct and indirect measures at our disposal short of invasion and occupation that could have gotten us the desired effects or something close.

I’m going to try and not go as far as the certified big brain genius who opined “if only we had just killed Bin Laden right after 9/11,” But I am going to engage in a similar kind of exercise here. What I am going to try and do is look over some credible or plausible alternatives to the path we went down to drive home that the path we took wasn’t the only one. Please keep in mind that while I’ll try to keep these somewhat grounded, they are just musings at the end of the day with a fair amount of wishful thinking on my part. What I’m really trying to do is drive home how unnecessary this all was with all the potential options that were available as a whole (and maybe cope and vent a bit).

First of all, we could have launched a campaign of air and missile strikes that stopped short of an actual ground invasion. Obviously, this may not seem like an improvement given when you consider the thousands of civilian fatalities from US and Allied airstrikes over twenty years of occupation in Afghanistan (over 2,000 just between 2016 and 2020). But even then, a short but intense campaign of bombing against al Qaeda and Taliban military facilities probably could have done just as well in damaging both of those organizations capacity to threaten the United States and others as twenty years of occupation would have. If necessary, those could have been followed up in the future as well. It may have softened the Taliban up for the Northern Alliance without ever needing any boots on the ground. It wasn’t even unprecedented, as we had done the same thing in Afghanistan just several years prior. The entire Afghan invasion initially started out just as a campaign of airstrikes before troops were sent in a couple weeks later. An air-only campaign wouldn’t have defeated al-Qaeda of course (we still haven’t done that regardless) but it probably could have weakened them enough in Afghanistan to prevent them using that country as an effective base for an extended period of time – maybe even force them out of Afghanistan indefinitely, in combination with Northern Alliance pressure on the ground.

On that note, what if you want to go further and keep U.S. military power (directly) out of the equation, completely? Then we could have provided more extensive material support to the Northern Alliance in their battle against the Taliban (rather than taking our ball and going home not long after the Soviets were forced out in 1989). We could have provided them with more and better weapons, training, political and diplomatic support, and so on. We could have worked to try and help them find broader appeal across the rest of Afghanistan and muster more support within the country. We could have coordinated with the Northern Alliance’s supporters in the Central Asian republics bordering them in carrying out that support. We could have worked to more actively muster support throughout the world for the anti-Taliban resistance. That may not have been as ‘shock and awe’ as going in on the ground or bombing from the air, but it still likely would have been the better choice both for ourselves and the Afghan people even with how much of a prolonged bloody conflict it still might have been.

But we can go even farther. Did we need to have any military involvement at all, period? Regardless of whether it was us directly shooting, or supporting someone else in shooting? One narrative is that we could have had Usama Bin Laden right then and there after 9/11 if we had struck a deal with the Taliban. Initially the Taliban refused any demands to turn over Bin Laden to the U.S. government when being threatened with military action, but it left the door open to negotiation. This willingness to negotiate increased once the bombs started falling, by which point President George W. Bush dismissed it out of hand. This raises two questions, the first being; was there more room for negotiation or even coercion short of military action prior to embarking on military action in Afghanistan? Was there a stick or carrot that may have been able to convince the Taliban to sell out al Qaeda before a shot was fired? Or even after the first bombs were dropped, once the Taliban were more willing to discuss terms, may we have been able to get Bin Laden right then and there without committing to an invasion and regime change? And could we have explored these options without completely setting aside the threat of invasion as leverage? It seems to me that all of these could have been plausible options – but weren’t. For one reason or another – a desire for revenge, a desire for a war, and other reasons that would take too long to explain here – we cast all of those aside and embarked on a path to invasion and occupation.

Being In

So, we’ve seen that there were at least some plausible alternatives to avoid an invasion or even potentially avoid military action outright. But let’s assume we couldn’t avoid a ground war no matter what. That then raises the question, did the ground war have to pan out the way it did? Did it have to turn into a twenty year long bloody quagmire.

Very quickly: I’m not suggesting in any shape or form the war was “winnable,” because it absolutely fucking was not. There was no way we were ever going to win in Afghanistan. Like with the vast majority of counter-insurgencies – as I’ve mused in the past – the most an occupying power or COIN force can ever hope for is to not lose and try and stave that off indefinitely if they’re not willing to make political concessions. We were never going to “win”, if the objective was to completely get rid of the Taliban or any other anti-government insurgent force and create a friendly client-state that wasn’t necessarily in tune with the feelings and desires of the Afghan people as a whole. That was never going to be achievable. As I also have said, regime change enforced from the outside is largely unachievable except for the biggest of outlier cases (your World War II Germany and Japan for example, which have ruined the curve in my opinion).

But what if we had kept our objectives and campaign limited? What if we had stayed focused purely on going in to root out some or all of al Qaeda and to try and track down bin Laden and other al Qaeda leadership? What if once we had either accomplished our objective, or it became obvious that Bin Laden was gone and al Qaeda no longer had a significant presence in the country, we pulled out our troops and continued the search elsewhere? We could have maybe maintained support of the Northern Alliance against the rest of the Taliban that we hadn’t defeated yet, maybe even had some limited special forces operators on the ground, but not the thousands of troops we ended up with at the peak of the occupation.

If you so desire, we can even modify this idea a bit. Regardless of whether or not we found Bin Laden or fully defeated al Qaeda or the Taliban (all things we didn’t do – well, we did find Bin Laden, just not in Afghanistan), we could have continued to fight alongside the Northern Alliance in their battle against the Taliban and then once they had removed the Taliban from power we could have then withdrawn our troops. We could have left the Afghans to their own affairs once the Taliban were no longer in charge of the country as a whole and were much reduced in their capacity to provide safe haven to al Qaeda and Bin Laden. We could have continued to provide indirect support – military or non-military – without being near as involved as we ended up being in their internal affairs. In that case, we could have walked away even if we hadn’t gotten Bin Laden while still having it be a “win” if that’s what Bush really wanted.

To be clear, I don’t necessarily think that whatever Afghan government that would have arisen if we had pulled out immediately after the fall of the Taliban would have been able to do much better then the one propped up by our occupation there. We probably still would have seen a civil war of some kind erupt again and also certainly see corruption and other issues remain endemic. My point here was, there was still a window for some time after the initial invasion that we may have been able to withdraw during which we would have felt like we accomplished more and not done as much harm to Afghanistan as we would end up doing. I won’t go as far to say we would have left Afghanistan a better place – I’m not going to discount it but say that I’m skeptical and also that it’s impossible to say. But what we could have done is left an Afghanistan that, despite the problems it still undoubtedly would have had, may have had more hope today than we find it having now after the path we chose to go down instead.

Getting Out

Speaking of how we left Afghanistan in August of 2021.

If you’ve listened to anything I’ve written in these essays, or posted on Twitter, or if you’re one of my friends and heard me rant and rave in DMs, you know that I think leaving Afghanistan was the right thing to do and we should have done it a long time again (hence, this entire essay in itself). I don’t regret that we left, only that we didn’t do it sooner and smarter.

It is on that note, I have to say, seeing the way we left Afghanistan and how we treated the Afghan people in the process made me some of the most ashamed I have ever been of my country and my government in my entire adult life – right up there with the way it responded to the George Floyd Protests in Summer 2020. Part of the reason I was glad I didn’t have to write this essay right away is its honestly taken an entire month to square away the feelings it invoked in me watching what was happening to Afghans as we left. It felt awful to watch and I can only imagine how it felt for the people living there and trying to survive, as well as people who served there and earnestly thought they were trying to do good only to see how it was all for nothing. Even not being Afghan or a servicemember or veteran, I felt overcome by watching the way in which the war that made up most of my life so far come to a tragic and hubris ridden end. Quite frankly, if watching someone fall from a C-17 after clinging on in a desperate attempt at fleeing for your life doesn’t affect you profoundly in some way, I don’t know what to tell you.

But could we have avoided our exit being as much of a shitshow as it was? Short answer: yes. Longer, angrier answer: of course, we fucking could have we just decided not to.

The moment Joe Biden decided he was going to stick to the Trump Administration’s deal with the Taliban to withdraw, he could have started taking measures right then and there to try minimize the amount of harm that was going to be done no matter what. We could have made the Special Immigrant Visas for Afghans easier to obtain and start flying refugees out immediately. As a matter of fact, we could have forgone the visa program all together and simply offered to fly out anyone and everyone who wanted to leave the country at pretty much any point between Biden made his call and when the downfall of the old Afghan government was looking all the more certain. We could have attempted to work with allies and partners ahead of time on the issue of resettlement. We could have marshalled far more of the U.S. military much earlier to evacuate vulnerable people from the threat of harm or death. We potentially even could have considered going back to the negotiating table and trying to get a better deal with the Taliban – still committing to a withdrawal but under terms that would have gotten more breathing space. Oh, and since Biden claims he planned on seeking a withdrawal regardless of Trump’s deal with the Taliban, we could have started doing all of these things and more way sooner.

Again, let me be clear on something: I don’t think there was a way we could have kept the Afghan government from collapsing. That was inevitable from the way it had developed. I think anyone in national security field with more than a passing familiarity with the situation knew that sooner or later after we withdrew, the Afghan government would fall. Those of us who were a bit more in the know felt that it would happen sooner rather than later. Not to be ‘I told you so’ about it, but I was very much in the ‘sooner rather than later’ camp, but even then, I was still shocked at how soon it all unfolded (I had given them until the end of the year, maybe a month or so into 2022 at the most, but apparently I was being too generous even then). The Taliban winning was always going to happen once we gone. Full stop.

What makes me ashamed and outraged is, knowing this, we could have done so much more to protect the people that we knew for a fact were going to be in danger once the inevitable happened. We had the time, we had the knowledge, we had the resources and opportunity, but we didn’t. We left it until the last minute and as a result, so many more people are in danger of death or harm or who knows what else because we simply chose not to do anything. I could give you a laundry list of reasons why we didn’t do this: racism, political ineptitude, racism, self-delusion, racism, overconfidence, racism, and etc. But whatever the reason, we just didn’t.

That reality makes my cry of “it didn’t have to be like this” even more forlorn here than with the other sections. My other “what ifs” thinking about the road not taken in Afghanistan had to do more with having a better handle on the political-military problem and the geopolitical landscape we were walking into. Morality and ethics certainly weren’t divorced from it but weren’t the only force at play. When it came to the evacuation from Afghanistan, we knew damn well what was coming and the right thing to do was obvious to anyone with a semblance of a heart in their chest. But we didn’t anyway. Because of that, I’m never not going to feel some degree of shame in my life for who and what we left behind. It didn’t have to be like this.

It didn’t have to be like this. But it is.

And here we are. The Taliban have announced their new interim government, all the while Afghanistan’s economy continues to take a nosedive and basic services break down. The resistance in Panjshir appears to have been largely conventionally defeated though it has promised to continue the fight (something that I sincerely hope happens). Dark days definitely seem ahead for a country that has had forty years’ worth of very dark days from one source or another. It didn’t have to be like this, but it is. So now what?

There are some actionable things that we can do as individuals to try and help those who have managed to escape Afghanistan, as well as those that remain. We can donate time and money to organizations that are trying to help people survive – whether its back in Afghanistan or trying to forge a new life elsewhere. We can also try our best to the extent that we are able to hold our elected officials responsible for creating this mess over the course of twenty years (if I’ve found anything out on social media in the last year or two, its that bullying upwards can actually work).

Aside from these examples, however, there’s not a lot we can do other than hope for something better someday. We can hope that the resistance does not die out and returns in another shape or form and receives the outside support it needs in order to someday overthrow the Taliban (though I don’t think that should involve any new invasions, suffice to say). We can hope that, just as they’ve overthrown the Taliban and other regimes in the past, the Afghan people will eventually overthrow this one and maybe someday have a government and a system in their country that will bring them peace and safety and the human rights and more that they justly deserve. We can hope for a better system in our own country and others and continue to try and work towards that system – one that wouldn’t create the circumstances that led to August 2021 and interact with the rest of the world in a more just and less imperialistic way.

And finally, tied to all this, we can’t forget. The shame, the regret, the anger, the sadness, and more that I and others feel at watching what has happened – the capstone of twenty years of bad decisions and malintent – we can’t forget any of that. We have to remember what we did and have it fuel our desire for change. Things are going to get worse before they get better, for Afghanistan, for us, for the world. But instead of giving into despair and doomerism and being blackpilled or what have you, we need to take those painful memories and feelings and have them be a motivation to someday, somehow, make a better world. Not a perfect world, but a better one. We need to remember what those in charge now did, so we can try to avoid those actions and make any meaningful attempt at atoning for them. We need to realize we have these feelings because we have empathy for all people the world over and realize we have inflicted awful pain on them and that we want the pain to stop; that we don’t want things like this.

It didn’t have to be like this, and it doesn’t have to be like that again.

#essay#War Takes#War Takes Essay#leftism#leftist#socialism#democratic socialism#international relations#IR#national security#national defense#international security#foreign policy#foreign affairs#Afghanistan#War in Afghanistan#Fall of Kabul#Taliban#insurgency#counterinsurgency#war#9/11#September 11th#September 11#terrorism

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

I Hope you are well,

There a whole bunch of famous movies about the war in vietnam, such as first blood, apocalypse now, and full metal jacket. But while there seem to be a whole glut of war movies about Afghanistan and Iraq, I don’t know if I would say that there are any that capture the popular consciousness to the extent Vietnam war movies do. Am I mistaken? If not, why do you think so?

Have a nice day

I think part of it is that there is a disconnect between members of the military and civilians in a way that there really wasn't in Vietnam due to the abolition of conscription. During the Vietnam era there were approximately 2.6 million troops that served, nowhere close that number for both wars combined among a much larger population. Whereas by 1973, it was tough not to have a friend or relative who went to Vietnam, the US military is a little more insular now that it's all-volunteer, and much smaller (I'm not advocating for a return to conscription, just FYI, it's just how that is).

Another part of it is that Vietnam, culturally speaking, was tough to make sense of, but people wanted to know. Artistic efforts could help find a way to soften the gap without a veteran expressing a personal, uncomfortable piece of their own traumatic memory. These days, the civilian public largely isn't interested in hearing it.

And of course, for those that do speak and want to hear, the internet is around. For the few who are interested, they can read personal stories in a way you simply couldn't before the cyber revolution, either through personal writings or podcasts or what have you. That's just a function of the times and technology.

That's just what I think, though.

Thanks for the question, Fang.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Flugt [Flee] (Jonas Poher Rasmussen - 2021)

#Flugt#Flee#drama film#Denmark#Afghanistan#refugees#Jonas Poher Rasmussen#European cinema#Riz Ahmed#life#Nikolaj Coster-Waldau#Amin Nawabi#2020s movies#history#war in Afghanistan#European society#self-discovery#talibans#unaccompanied minor#life story#Copenhagen#gay marriage#withdrawal of US troops#US defeat#Kabul#Joe Biden#2021#US–Taliban deal#CIA#Antony Blinken

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

#GuyRitchiesTheCovenant, on demand war #action #thriller #movie set toward the end of the #WarInAfghanistan in 2018, follows an Afghan local interpreter risks his own life to carry an injured American sergeant across miles of grueling terrain.

#fiction #Afghanistan #Taliban

0 notes

Text

The Attacks of September 11th and its Aftermath

The attacks of September 11th were a grievous wound inflicted upon the moral, and intellectual psyche of the United States, and its government. It was incumbent going forward, for the United States to take the fight to the terrorist. That meant preempting

The Attacks of September 11th and the Aftermath

The attacks of September 11th were a grievous wound inflicted upon the moral, and intellectual psyche of the United States, and its government. It was incumbent going forward, for the United States to take the fight to the terrorist. That meant preempting the threat of violent extremism before it foments into violence. This also meant bringing…

View On WordPress

#22nd Anniversary#Arab Spring#Attacks of 9/11#bashar al assad#Diplomacy#internal security#middle-east#New York City#politics#Syria#Taliban#United States#Wahabihism#War in Afghanistan#War in Iraq

1 note

·

View note

Text

#free palestine#israel#democrats#republicans#politics#free gaza#war crimes#middle east#afghanistan#yemen#usa

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Mr. Xi is the son of an early Communist Party leader who in the 1980s supported more relaxed policies toward ethnic minority groups, and some analysts had expected he might follow his father’s milder ways when he assumed leadership of the party in November 2012.

But the speeches underscore how Mr. Xi sees risks to China through the prism of the collapse of the Soviet Union, which he blamed on ideological laxity and spineless leadership.

Across China, he set about eliminating challenges to party rule; dissidents and human rights lawyers disappeared in waves of arrests. In Xinjiang, he pointed to examples from the former Soviet bloc to argue that economic growth would not immunize a society against ethnic separatism.

The Baltic republics were among the most developed in the Soviet Union but also the first to leave when the country broke up, he told the leadership conference. Yugoslavia’s relative prosperity did not prevent its disintegration either, he added.

“We say that development is the top priority and the basis for achieving lasting security, and that’s right,” Mr. Xi said. “But it would be wrong to believe that with development every problem solves itself.”

In the speeches, Mr. Xi showed a deep familiarity with the history of Uighur resistance to Chinese rule, or at least Beijing’s official version of it, and discussed episodes rarely if ever mentioned by Chinese leaders in public, including brief periods of Uighur self-rule in the first half of the 20th century.

Violence by Uighur militants has never threatened Communist control of the region. Though attacks grew deadlier after 2009, when nearly 200 people died in ethnic riots in Urumqi, they remained relatively small, scattered and unsophisticated.

Even so, Mr. Xi warned that the violence was spilling from Xinjiang into other parts of China and could taint the party’s image of strength. Unless the threat was extinguished, Mr. Xi told the leadership conference, “social stability will suffer shocks, the general unity of people of every ethnicity will be damaged, and the broad outlook for reform, development and stability will be affected.”

Setting aside diplomatic niceties, he traced the origins of Islamic extremism in Xinjiang to the Middle East, and warned that turmoil in Syria and Afghanistan would magnify the risks for China. Uighurs had traveled to both countries, he said, and could return to China as seasoned fighters seeking an independent homeland, which they called East Turkestan.

“After the United States pulls troops out of Afghanistan, terrorist organizations positioned on the frontiers of Afghanistan and Pakistan may quickly infiltrate into Central Asia,” Mr. Xi said. “East Turkestan’s terrorists who have received real-war training in Syria and Afghanistan could at any time launch terrorist attacks in Xinjiang.”

Mr. Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao, responded to the 2009 riots in Urumqi with a clampdown but he also stressed economic development as a cure for ethnic discontent — longstanding party policy. But Mr. Xi signaled a break with Mr. Hu’s approach in the speeches.

“In recent years, Xinjiang has grown very quickly and the standard of living has consistently risen, but even so ethnic separatism and terrorist violence have still been on the rise,” he said. “This goes to show that economic development does not automatically bring lasting order and security.”

Ensuring stability in Xinjiang would require a sweeping campaign of surveillance and intelligence gathering to root out resistance in Uighur society, Mr. Xi argued.

He said new technology must be part of the solution, foreshadowing the party’s deployment of facial recognition, genetic testing and big data in Xinjiang. But he also emphasized old-fashioned methods, such as neighborhood informants, and urged officials to study how Americans responded to the Sept. 11 attacks.

Like the United States, he said, China “must make the public an important resource in protecting national security.”

“We Communists should be naturals at fighting a people’s war,” he said. “We’re the best at organizing for a task.”

The only suggestion in these speeches that Mr. Xi envisioned the internment camps now at the heart of the crackdown was an endorsement of more intense indoctrination programs in Xinjiang’s prisons.

“There must be effective educational remolding and transformation of criminals,” he told officials in southern Xinjiang on the second day of his trip. “And even after these people are released, their education and transformation must continue.”

Within months, indoctrination sites began opening across Xinjiang — mostly small facilities at first, which held dozens or hundreds of Uighurs at a time for sessions intended to pressure them into disavowing devotion to Islam and professing gratitude for the party.

Then in August 2016, a hard-liner named Chen Quanguo was transferred from Tibet to govern Xinjiang. Within weeks, he called on local officials to “remobilize” around Mr. Xi’s goals and declared that Mr. Xi’s speeches “set the direction for making a success of Xinjiang.”

New security controls and a drastic expansion of the indoctrination camps followed.

The crackdown appears to have smothered violent unrest in Xinjiang, but many experts have warned that the extreme security measures and mass detentions are likely to breed resentment that could eventually inspire worse ethnic clashes.

— ‘Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims

#austin ramzy#chris buckley#‘absolutely no mercy’: leaked files expose how china organized mass detentions of muslims#current events#racism#islamophobia#politics#chinese politics#terrorism#history#communism#surveillance#uyghur genocide#xinjiang conflict#war in afghanistan#war on terror#china#xinjiang#east turkestan#uyghurs#xi jinping#hu jintao#chen quanguo

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books of 2023

Book 6 of 2023

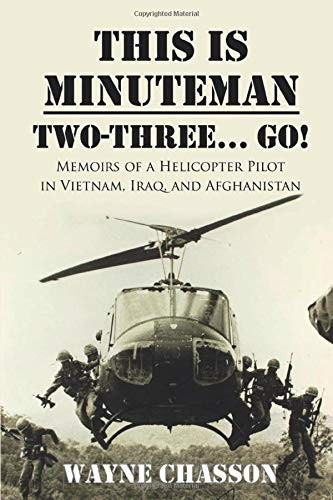

Title: This is Minuteman Two-Three... Go!

Authors: Wayne Chasson

ISBN: 9781676785644

Tags: AFG Afghanistan,AFG FOB Shank (OEF),AFG FOB Tellier (OEF),AFG Kabul,AFG Operation Enduring Freedom (2001-2014),CH-54 Tarhe,IRQ Iraq,IRQ Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003) (Iraq War),KWT Kuwait,OH-23 Raven,OH-6,SA 330 Puma,UH-1 Huey,US CIA Central Intelligence Agency,US Erickson Helicopters,US Evergreen Helicopters,US USA 11th Light Infantry Brigade,US USA 176th Assault Helicopter Company,US USA 176th Assault Helicopter Company - Minuteman,US USA 176th Assault Helicopter Company - Muskets,US USA 196th Light Infantry Brigade,US USA 198th Light Infantry Brigade,US USA 1st Aviation Brigade,US USA 23rd ID - Americal,US USA 23rd ID (Americal),US USA 71st Assault Helicopter Company,US USA ANG 126th Aviation Regiment,US USA ANG 126th Aviation Regiment - 3/126,US USA ANG 126th Aviation Regiment - 3/126 - A Co,US USA ANG Army National Guard,US USA ANG Massachusetts National Guard,US USA Fort Hunter-Stewart GA,US USA Fort Polk LA,US USA Fort Rucker AL,US USA Fort Wolters TX (1963-1973),US USA LRRP Team (Vietnam War),US USA United States Army,US USA USSF Green Berets,US USA USSF Special Forces,US USAF ANG Otis Air National Guard Base MA,US USMC United States Marine Corps,VNM An Khe,VNM Chu Lai,VNM CIA Air America (1950-1976) (Vietnam War),VNM Command and Control North/FOB-4 (Vietnam War),VNM Dragon Valley,VNM DRV NVA North Vietnamese Army,VNM DRV VC Viet Cong,VNM FSB Baldy (Vietnam War),VNM FSB Mai Loc (Vietnam War),VNM Highway 1,VNM LZ Baldy (Vietnam War),VNM LZ Bowman (Vietnam War),VNM LZ East (Vietnam War),VNM LZ Minuteman (Vietnam War),VNM LZ Stinson (Vietnam War),VNM LZ West (Vietnam War),VNM Marble Mountain,VNM Million Dollar Hill,VNM My Lai,VNM Mai Loc Special Forces Camp (Vietnam War),VNM Operation Ranch Hand (1962-1971) (Vietnam War),VNM Route 9,VNM RVN ARVN Army of the Republic of Vietnam,VNM RVN Chieu Hoi Program/Force 66 - Luc Luong 66 (Vietnam War),VNM RVN Kit Carson Scouts (Vietnam War),VNM RVN SVNAF South Vietnamese Air Force,VNM Tam Ky,VNM Tien Phuoc,VNM US Agent Orange (Vietnam War),VNM US MACVSOG (1964-1972) (Vietnam War),VNM US USA 27th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (Vietnam War),VNM US USMC CAP Combined Action Platoon (Vietnam War),VNM US USMC DHCB Dong Ha Combat Base (Vietnam War),VNM Vietnam,VNM Vietnam War (1955-1975),VNM Vinh Thanh Valley (Happy Valley)

Rating: 3 Stars

Subject: Books.Military.20th-21st Century.Asia.Vietnam War.Aviation.US Army.Helos.Gunships, Books.Military.20th-21st Century.Asia.Vietnam War.Aviation.US Army.Helos.Slicks, Books.Military.20th-21st Century.Middle East-SWA.Afghanistan.US, Books.Military.20th-21st Century.Middle East-SWA.Iraq.OIF.US Army

Description:

Relive six decades of flying helicopters including an extended tour in Vietnam and the mountains of Afghanistan, with a little Iraq, Kuwait, and National Guard thrown in. This is Minuteman: Two, Three… Go! recounts Wayne Chasson’s times, from the early, young, and dumb days to a more seasoned pilot of Huey and other helicopters in three American wars and the National Guard here at home. From the tragic to the ridiculous, it’s all here in refreshing candor and lifelike detail, and told in the voice of the author. Chasson relives it all for us in this gritty and honest memoir—with humility, humor, and gratitude—as he himself is still trying to figure out how he made it through alive.

Review: It was a decent book, a quick read that really is more of his look back on things. It gives you some good stories, some good anecdotes, and it’s semi-polished enough to give it readability and flow. It won’t give you the same experience as Chickenhawk or others in the same genre, but it will give those who know him - family and friends and such - a good insight into what he wants them to know about his time in Vietnam, and later Iraq and Afghanistan.

#Books#Booklr#Bookblr#ebooks#vietnam war#iraq war#war in afghanistan#operation iraqi freedom#operation enduring freedom#helicopters#history#nonfiction#us army

0 notes

Text

Counterinsurgency: The Impossible War? (OLD ESSAY)

This essay was originally posted on May 5th, 2021.

Written after President Biden announced that the United States and its allies would be withdrawing the last of its troops from Afghanistan that year (but before the infamous collapse that would happen some months later), this is where I started to lay out my theory on the nature of insurgencies and attempts to counter them.

(Full essay below the cut).

The time has finally come, apparently. After almost twenty years of turning many purported corners towards victory, the United States and its allies have decided to withdraw their combined military forces from Afghanistan. President Joe Biden announced this move on April 14th, 2021, with the intent of completing the withdrawal by September 11th, 2021 (a weird choice as that date that holds no symbolic significance insofar as I can remember). This withdrawal has already begun in earnest at the time of writing this essay and is due to pick up in the coming months.

I for one, am all in favor of this withdrawal – assuming we actually follow through on it. Lord knows that an entire army of think tank personalities, politicians and both current and former government and military officials have been mobilizing since the announcement was made in order to offer every reason under the sun why withdrawing from Afghanistan would be a tragic and horrible mistake. If you can imagine a reason to stay forever, someone has probably written an op-ed about it by now in one of the broadsheet newspapers or for one of the major news networks.

But if we actually do leave, I think its way past time. Don’t get me wrong, I am by no means indifferent to the fate and plight of the Afghan people once we do leave. I’m not blind to what will probably happen to the fragile Afghan state and military in the face of the Taliban and other armed groups once Western forces are no longer propping them up, and I dread the thought of what will happen to ordinary Afghans in the face of what will likely be unleashed upon them after the withdrawal is complete. What is almost certainly going to happen is horrible and tragic – that is one thing I agree with all the talking heads on in this situation.

That is about the only thing I agree with them on, however. The fact that the Afghan state will almost certainly collapse after we leave is indicative of the fact that twenty years of U.S. and NATO counterinsurgency (COIN) operations in Afghanistan to defeat the Taliban and other armed groups have been an abject failure – as have any related measures in the realm of nation-building. Our being there hasn’t helped anything, but has only made things worse through our own ineptitude or callousness (or sometimes both). While things will very likely get worse for Afghanistan in the near-term – and that is awful – our being there will only be worse for their country and our own in the long-run. It is arguable whether we even had to be there in the first place to accomplish our original reason for going in. It is time to leave, end of story.

Now, we could have a long, in-depth political discussion about why we stayed in Afghanistan for so long and underlying reasons for why we choose to go in to begin with – aside from going after Osama bin Laden (who was a fucking horrible person by the way, make no mistake; rest in piss, Osama). But that’s not what I want to focus on in this essay. Sorry if you’re disappointed.

Instead, I feel the withdrawal from Afghanistan is an excellent opportunity to talk about another obvious question: why the United States and its allies couldn’t “win” the war in Afghanistan after twenty years occupying it, thousands upon thousands of lives lost and people maimed, and billions of dollars spent. This in turn opens up a wider discussion about whether or not you can actually win what has been dubbed “counterinsurgency” to begin with, especially when you draw a long line through the myriad of other attempted COIN campaigns throughout recent history.

Strap yourselves in. This is gonna be (another) long one, people. Another heads up, I’m obviously will work to back my historical claims with some evidence, but a lot of my general musings on insurgency as a form of warfare are basically just my own mental vomit in text form. I haven’t served in uniform, and my experience as a defense profession has focused on conventional war. I’m just trying to offer my perspective looking in after growing up in the shadow of these wars, trying to point out what seems obvious to me after twenty something years.

Chasing the COIN Dragon

When I titled this essay, I was very careful to put a question mark after “the impossible war” because as an analyst, I try to avoid absolute certainties and black and white reads of a situation. A truly successful COIN campaign may be achievable, but I feel like the number of circumstances that would have to line up to make such a victory possible would be so unique and specific to any given situation (as well as rare) as to be unrepeatable and un-useful as a template. So, while I leave myself open to that possibility, such a war – even if feasible – would be the exception, not the rule. With that in mind, whenever I say that COIN is “impossible”, why don’t’ you just assume I mean “next-to-impossible” or “practically impossible” in reality.

But all that being said, I started writing this piece in late 2020 and in that time, I’ve tried to think of some actual “wins” in COIN. By win, I mean where the COIN side of the conflict actually won the war wholesale, completely defeating the insurgent adversary. I consider myself a fairly astute student of modern military history, and as I searched my mental databank of 20th and 21st century insurgencies, I couldn’t think of a single goddamn one where the COIN force actually won. Oh, I can think of at least a handful of insurgencies that eventually grew to the point they successfully overthrew the government they were fighting: Cuba, Vietnam, There still aren’t a ton of instances where the insurgents fully win either – something I’ll touch on later – but there’s still more of those instances I can think than ones where COIN forces won.

I expect someone may disagree with me here and try and offer up their favorite COIN campaign as proof I’m wrong. One potential COIN “victory” that may get brought up is the Malayan Emergency where the British supposedly helped wage a successful COIN campaign against Malayan communists. Well, two problems for me with that campaign: 1.) the success was only fleeting, as within a decade or so of it ending a fresh insurgency had cropped up, going on for decades until ending with a peace accord in 1989; and 2.) it required some methods that quite frankly would be war crimes today (and arguably would have been that even at the time), and I think the moment you need to resort to war crimes to be “successful” in any war you’ve lost the plot completely.

There may be other conflicts someone might bring up to say “the government won this civil war here, so ha ha.” The thing is that a civil war and an insurgency are not necessarily the same thing to me. Most insurgencies are civil wars, but you can have an insurgency that isn’t a civil war – when its solely against a foreign occupying power. You can also have a civil war that is mostly conventional in nature, with both sides fighting in open warfare. An insurgency can grow into a full-scale civil war or rebellion, but that is not guaranteed to happen and depends on a lot of factors – another thing I’ll touch on in a bit. Since I harp on about definitions a lot, the definition of insurgency I’m using is the Merriam-Webster definition of “a condition of revolt against a government that is less than an organized revolution and that is not recognized as belligerency.”

So, now that we know what we’re talking about with insurgencies, why is it that there doesn’t seem to be any real COIN victories? That is a question I feel the U.S. military hasn’t asked enough – if at all. They’ve focused so much on trying to find a “theory of victory” for COIN I don’t think they ever stopped to really consider why they haven’t been able to win already if they’re supposedly doing all the “right” things. The U.S. military establishment has put a lot of time, money, and effort into devising ways to try and prosecute COIN, including a whole-ass manual written by everyone’s favorite four-star philander General David Petraeus (Ret.) along with Trump’s formerly favorite Marine General James “Chaos”/”Mad Dog”/”Warrior Monk” Mattis (Ret.) back in 2006.

This approach really illustrates the heart of the matter, which is a lot of times people who think about COIN think about it purely in the sense of fighting a war in the tactical sense, focusing on killing hostiles and what have you – even if they pay lip service to hearts and mind. I bet a lot of the “successful” COIN campaigns some people would offer to me in rebuttal would be ones where the COIN force showed some success at least in finding and kill insurgents or temporarily disrupting their operations at a tactical level – but still failed to bring the conflict to a conclusion. What these approaches miss is that insurgency is inherently a political issue, not purely a military one, and therefore cannot be solved by military means on their own.

And so, we reach the main point of my article (half-way in): COIN is almost impossible to win because at the end of the day, the only way you can make it stop permanently is by offering some kind of political concession to the insurgents – which inherently involves admitting defeat in the conflict to some degree.

But why is that the case? Again, I’m not a COIN expert by profession (arguably, no one is), but the best way I can figure an insurgency or any kind of rebellion or armed uprising or civil war usually begins because there is a group of people within a territory with certain demands or needs that are not being met by the power in control – whether that be a government or an occupier. The group feels that any other avenue through which change could feasibly be achieved has been closed off to them or rendered ineffectual, and that they have been left with no other recourse than to resort to armed conflict in order to try and force those in power to answer their grievances – whether those be a limited set of policies or actions or the removal of the authorities themselves from power and their replacement with new leaders.

It’s important to note before we go any further that these demands or needs don’t necessarily have to be legitimate or reasonable or altruistic or even potentially based on reality, but they have to be ones that the group feels strongly enough about to go to war over for whatever reasons. It’s also important to note that none of this is assuming the insurgents are going to be the “good guys” by default. I can think of more than a few insurgent groups from history that started out with good intentions only to become as bad as or worse than the governments they were fighting – or insurgent groups that started out bad and had bad opinions from the get-go only to get even worse over time. However, we’re not debating the justness of insurgencies here. What we’re looking at is the mechanics of why winning them is next to impossible.

“We’ve Always Been at War With East Insurgentia”

Getting back on track: in an ideal world, you either would have everyone’s needs met, or if they weren’t, the people would at least feel they had other mechanisms through which to enact change short of armed violence. Of course, we live in a less than ideal world. States are often not only deaf to the requests or pleas of their citizens, but also often react to those pleas with violence as a punishment for ever questioning their authority in the first place. This is to say nothing of how an occupying power may react. When people feel that the system is broken – or there is no system for them to work through in the first place – it’s no wonder why rebellions and insurgencies so often occur. What is more surprising is why governments and their supporters or backers are often so surprised that they can’t seem to end an insurgency when the cause and the solution to their problem has been in front of their face the entire time.

As long as the original grievances that were bad enough to cause an insurgency to exist continue to do so, and the system to address grievances remains broken or non-existent, and the grievances go unanswered, an insurgency will likely continue. It doesn’t matter how many insurgents are killed, weapons caches seized, hearts and minds attempted to be won – as long as that original cause is still there the fighting can linger on for decades. After all, when people are willing to take up arms for a cause, chances are they’re willing to die for it or hold out until they see some results. There may be pauses or lulls, but at the end of the day they are only that: pauses. So, the only way you will ever conclusively end the fighting is to either give the insurgents what they want or reach some kind of compromise that they find amenable and fair and in which you are giving up something that is acceptable to you and you are willing to part with in negotiations.

This is why you can’t “win” a counterinsurgency in the same way you can defeat an invading army or other conventional aggressor. You can avoid flat-out losing in COIN indefinitely, but because an ultimate end to an insurgency requires some kind of appeasement to insurgent demands, total victory is impossible. If you are not willing to concede and accept a loss, or compromise and accept some form of a draw, the best-case scenario is to be locked in a forever war that maybe you can maybe keep locked down from expending a vast number of lives and resources – if you’re lucky. Even then, the best you can hope for is to essentially keep a house fire limited to one corner of one room, with the ever-constant threat hanging over you that it may suddenly flare up again and having to keep expensive firefighting equipment on standby at all times to manage the fire and be prepared for a spread.

This is also the reason that while I consider a counterinsurgency unwinnable, I do not think the same of a more conventional civil war. This speaks to a paradox or irony of insurgency I’ve noticed when it comes to the insurgent side. When your rebellion remains limited to an insurgency, disparate and spread out in small disconnect groups, it’s really hard for you to lose but – much like the COIN guys have a hard time winning – it’s also hard for you to win if your goal is overthrowing the government or throwing out the occupier. With a foreign occupier, you may still be able to win as a low level insurgency if you’re just willing to sit tight and wait it out for a few decades until they finally realize it’s not worth it and withdraw. But, if you’re also fighting your own government, they may hang on harder because they stand to lose more if you’re seeking to kick them out or hold them to account or lop off a sizeable chunk of their territory and secede as your own country.

This is why Mao Tse-Tung (who I’m not a fan of but does understand this subject fairly well) divided guerilla warfare into three different phases, as detailed in his own book on the subject, translated by the U.S. Marines. The first phase consists of organizing, training, equipping, and consolidating your forces out of harm’s way, before escalating to insurgency in the second phase. It was only in the third and final phase when the guerilla force reached critical mass and the enemy was weakened that the insurgency would cease to be an insurgency and shift into a conventional war of maneuver against the enemy forces.

Therein lies the paradox that, by increasing your forces and shifting your strategy to focus on conventional warfare, while your chances of victory increase, so do your chances of defeat. It’s a lot easier for your army to be defeated when you have to maneuver in the open, massing your formerly disparate forces where they can be spotted and hit with artillery and airstrikes if you don’t remain dynamic and flexible as a commander. That’s why, while there are arguably no cases where a COIN force outright defeated an insurgency, there are still more than a handful of cases where the government or governing power in a conventional civil war defeated the rebel force. Escalating to that level carries obvious risks to the insurgent force if done at the wrong time or under the wrong circumstances and maybe that’s why many insurgencies appear to stay as insurgencies indefinitely.

This brings up an interesting point that, while its ultimately easier for an insurgent force to win an insurgency than a COIN force to win a counter-insurgency, it’s still damn hard for the insurgents to win. More often than not, it seems insurgencies just drag on indefinitely, only occasionally resulting in a definite conclusion. Otherwise, what you get are what we now know as “forever wars”, with the death and destruction and senseless waste crawling on across decades to the point you have entire generations who have only ever known the war.

The unwinnable nature of counterinsurgency is especially obvious when you consider the core reasons why counterinsurgency efforts to preserve colonial empires ultimately failed. The French were never going to win in Algeria or Vietnam, nor the Portuguese in Angola and Mozambique, or the Dutch in Indonesia, and so on and so on. The original grievance of the local people was the very fact that those foreign colonial empires had control of their lands, and the only way it was ever going to end was with the imperial powers leaving.

Even some of the counterinsurgency “victories” among this era of the final gasps of colonialism that someone might bring up to challenge my argument aren’t really victories when you look closer. We already saw this with the Malayan Emergency, but it can be found in another British example from that period in Africa. The British “defeated” the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya – after spending £55 million in 1950s money and the largest wartime use of capital punishment in the history of the British Empire – only to turn around and give Kenya independence some three years after the uprising had supposedly ended. Who really won there in the end?

This brings us back to Afghanistan, the muse for this piece. However bad the Taliban and al Qaeda are – and they are in fact very bad – at the end of the day, we invaded Afghanistan. We were never invited in with the consent of its people to help them to push back an invader or to undertake some other altruistic task. While military planners and think tank ghouls scratch their hands and agonize over how their various COIN tactics and strategies haven’t panned out, the point flies over their head. They ignore or forget that the key reason why the Taliban still attracts support and is able to fight back against us is because ultimately, more than enough Afghans do not want us there and will not stop until Western militaries are no longer in that country.

This is by no means an apologia for the Taliban or al-Qaeda or Islamic State or any of the other groups that brutalize and oppress Afghans – let me be crystal clear, fuck those guys. But at the end of the day, other ideology aside, enough Afghans oppose a U.S. military presence in Afghanistan and the government that we established after the invasion that until we are gone, and changes are made to the way that Afghanistan is governed, conflict there will never end. It’s that simple. If COIN is already extraordinarily difficult to win as a state fighting its own population, it must be truly impossible as an imperial power that has assumed control of an area – especially when you consider how many empires have tried and failed to conquer Afghanistan in particular, earning it its moniker of the “Graveyard of Empires.”

“The only winning move is not to play”

Ok, so counterinsurgency is practically unwinnable. I could walk away just at that and call it an essay. But I feel it’s worth trying to end this with something actionable here instead of just dealing with this purely in a “not even once” negative message.

If COIN is unwinnable, the real “winning” strategy is a preemptive one. (i.e., ensuring that you create the conditions that would prevent an insurgency from breaking out in the first place). Having a political system that is truly free, democratic, just, transparent and responsive to any grievances from its citizens seems like a good and obvious starting point – so they have avenues to go down to try and change things that are actually working and available and have a shot of success. Likewise, working to create a system where the basic needs of your citizens are provided for seems like it would stop a lot of people from having serious grievances to begin with, let alone resorting to taking up arms to seek redress. Granted, I am a pie-in-the-sky lefty, so what the fuck do I know, right? This would never make it in a McKinsey slide deck.

But even when the will to do this is present, there’s the question of “but what good does this do for a country like Afghanistan?” Fair point, honestly. It’s easy to say all this living in a developed, Western country – even with all the many, many problems those have these days. All I can say to that is, even if other countries are willing and able to offer the assistance to try and make that happen, at the end of the day the people of that country also have to want a different system and be willing to take action to make that happen. It’s not something that can be forced upon them, nor should it be forced upon them (this is part of the reason I am very much opposed to regime change by outside forces, something I want to write about in another essay, so stay tuned). It is up to the people in a given polity to decide when enough is enough. It may be hard to watch people suffering from the outside in – I know it is for me when I look at the world today – but ultimately that choice is theirs and theirs alone. Decades of sunk costs in Afghanistan should be proof of that. A people have to decide for themselves when it’s time for a change, not foreign entities. All you can do in the meantime from the outside is do what you can to help them survive until they make that choice themselves.

The flip side to this may be “what about when a foreign power or entity is supporting an insurgency”, artificially inflating its power and capabilities and influence when it otherwise may not have that much or even exist to begin with. That’s another valid question and to be honest I don’t have a good answer to that. This is part of why I put a question mark after “unwinnable” in the title of this essay. There’s a lot of uncertainty. I don’t pretend to have all the answers here, and this is something that is worth some additional study. What happens when a foreign power is supporting an insurgency with malintent? I’d probably argue to an extent that the ability to be able to create an insurgency or inflate the powers of one still shows there is some kind of underlying grievance or issue in the country at hand, but that still may not be the case depending on the motivations of the intervening powers or powers supporting the insurgency. All I can say to that is, this is an idea I want to stick a pin in and think of later, because it is something that could become an issue in the future for new democratic socialist governments across the world that come to power and are faced with hostile forces unwilling to let them govern by any means available to them.

This admission by me in a way shows how little supposed defense analysts like myself understand about insurgency, despite the fact it has seemingly become the most common form of armed conflict in the world. Many so-called experts have knowingly or unknowingly misunderstood or misinterpreted the underlying issues of insurgency for decades now. As we finally, hopefully withdraw from Afghanistan after spending the majority of my life so-far fighting a fruitless and bloody war there, I can only hope that this leads to an awakening in understanding the reasons for why insurgencies begin in the first place, the pointlessness in trying to win them militarily, initiatives to try and remove the conditions that cause them to start in the first place.

Being the cynical bastard that I am, I don’t hold out a lot of hope that these concepts will sink in anytime soon. But maybe someday. You have to hold out hope for something these days, right?

#essay#War Takes#War Takes Essay#leftism#leftist#socialism#democratic socialism#international relations#IR#national security#national defense#international security#foreign policy#foreign affairs#peace#insurgency#counterinsurgency#COIN#Afghanistan#war in afghanistan#Operation Enduring Freedom#Taliban#the Taliban#nation building

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm gonna try to compile a list of resources for the genocides and humanitarian crisis going on so people will at least have a place to start so they can stay informed

Each place will have a link and then just click on the link to go to the resources. If yall have any you wanna recommend say it under the post of that place

Pls reblog the original posts so more people can see what’s been added

Hope this helps someone

Syria

Lebanon

Palestine

Sudan

Congo

Yemen

Iran

Morocco

Western Sahara

Armenia

Afghanistan

West Papua

Haiti

Tigray

Ukraine

Yezidi People

#congo genocide#free congo#democratic republic of the congo#congo#justice for palestine#free palastine#palestine#support palestine#save palestine#free sudan#sudan crisis#sudan genocide#sudan#free syria#syria news#syrian civil war#syria#lebanon#yemen#free yemen#yemen war#morocco#western sahara#armenia#afghanistan#west papua#free haiti#haiti crisis#haiti#save tigray

2K notes

·

View notes

Link

Is this a legit quote? Supposedly said by Carl Gershman, president of the National Endowment for Democracy from 1983 to 2021.

0 notes

Text

you can’t follow, know, recognize, react to, and mourn every mass tragedy and mass conflict and mass killing on earth, but you can avoid using language that talks about them being “not that bad” or “not so many children died” or “imagine if this happened in [somewhere This absolutely has happened]” or “nothing like this has ever happened” because it gaslights the experiences and realities of the people for whom it is real, right now

#Everyone deciding to make the case that the Syria Ukraine iraq and Afghanistan wars Weren’t That Bad on Twitter im in your walls#There’s also just been like massss disavowel and historical revisionism of a lot of things still affecting the survivors and descendants of#Survivors

2K notes

·

View notes