Note

I think this blog is amazing and would love to submit my story sometime, but I am a white transracial adoptee, taking in by a black family. I was wondering if y'all would be alright with that since this lovely blog is primarily for poc adoptees and their experiences, or if you know of any other active adoptee blogs I could visit? Almost all of the ones I have seen seem to be inactive. Anyway, I completely understand if you are not comefortable with this request, and I hope y'all have a good week

You are welcome here, just be aware that as a white person you occupy a space of privilege relative to the adoptees of color and be careful to stay in your lane.

- Mod R

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

i had no idea there was a place for transracial adoptees ok tumblr i thiught we were forgotten and im so god damn happy omg bless this blog im gonna go through it tomorrow thank u for existing lol 💓💓

Thank you for writing us!

- Mod R

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi sorry if this is a bit uhh..... inappropriate bit i feel like suicidal. i miss my chinese mom so mich even tho i dont even remember her. i feel isolated and misudnerstood. i cant feel anyones live bc i just want hers. ive been angry my whole life. i came as an angry and anxious baby but no one knew how to handle me. i never learnt how to deal with my anger and loss in a healthy way because no one cared and now im this monster

Hey anon,your feelings are not inappropriate! i understand your pain and anger and your emotions are totally valid.

it took me a long time to fully process the trauma of losing my ties to my biological family and the culture of my birthland. lots of adoptees struggle with anxiety and depression too. it doesn’t make you a monster - you are a real human being with real, valid struggles.

i’m not sure if this is an option for you, but a caring therapist can really help you to process your feelings and find healthy coping mechanisms. You also should work on developing outlets for your anxiety. when you feel like you’re losing control, what helps to calm you down? Do you like to color or draw? listen to music? is it possible to take a walk or do some stretches or other exercises? sometimes tactile experiences can help jolt you out of an anxiety or panic attack.

please feel free to reach out again if you are still struggling. we are here to help!

- Mod R

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Lots of transracial adoptees have this feeling too - where you didn’t grow up with Asian culture and thus didn’t experience the prejudice or oppression associated with Asian cultural practices, but still experience racism. Additionally, transracial adoptees often feel like they exist in a liminal space between and outside of both the dominant culture (white, in this case) and their birth culture (Asian).

If you’re interested, you can follow our blog for more information!

-Mod R

can you whitepass like culturally? i mean i didnt grow up with asian culture at all, i dont know anything. i obviously still look asian and experience racism bc the ppl who claim that ”assimilation is everything” are asshats. but is there a word for this?

I have no idea lol. I feel like there could be a word for that or there should be.

Angry Asian Guy

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Adoption Story

I was born in August of 1999, in Mixco, Guatemala. In the time between my birth and my final destination of US, I had a total of four different maternal figures. To the best of my knowledge, my birth mother took care of me for a short time, and then another woman when my birth mother was unable to look after me during the day (work?). Then, for whatever reason, I was put up for adoption and was delivered into the care of my foster mother, who did a tremendous job looking after me. Final, I ended up in the loving arms of my mom, who then, after the adoption was finalized, took me home to America. I have spent the rest of my life up until this point in the American Midwest.

I will first say that I am tremendously lucky. I have a loving home, and my adoption was never something that was held over my head, my parents were never of the mindset that they had rescued me from my original country or belittled me because my birth mother had given me up. In fact, my mom is herself adopted, so she is herself acutely aware of both the struggles that come with adoption, and that missing or wondering about ones birth family in no way detracts from their love for their adopted family. Mom had even reunited with her birth mother and I am very close to that side of the family, having grown up knowing them and celebrating birthdays and holidays with them. Adoption was always a subject that was open for discussion in my house, and my brother (also adopted) and I were encouraged to ask questions and share concerns about where we came from. It has always just been a part of who I am.

That said, even has happy as my story is, there are still struggles that I have to deal with, scars that are still healing. Due, I believe, to the rapid changes in a maternal figure at such a young age, I have deep seated trust issues and, outside of my family, I have yet to form a deep, lasting bond with another person. I enjoy the company of others, and I do have friends, but those relationships are based primarily on proximity, such as attending the same school or youth group. When I leave that environment, those relationships slip away. I have yet to figure out how to fix that broken piece inside me that allows me to watch years of friendship fall apart.

Ever since my senior year of high school, I have been dealing with some identity issues as I discern where I belong in terms of culture and ethnicity. I was born and lived out my infancy in Guatemala, and am therefore most definitely Guatemalan. At the same time, I can’t speak the language beyond a little over half a semester of college Spanish at this point, I don’t share the same cultural experience as my peers who were raised in a more Hispanic environment growing up as my family is very much white. I want to belong to a my ethnic group, but I share basically nothing in common with them as far as social background and to top it all off, I even look pretty white. Over the past year, it has caused feelings of loss and confusion as I try and figure out where I belong, where it is I have a place. When an internet search failed to turn up any satisfying articles on the subject, I turned to the tumblr community. As you may have guessed, I was not disappointed, and thus this blog which pretty much brings us full circle :)

My adoption story is not a tragic one as some of the ones I have come across, but is mainly one of trying to find a place, define my identity, and overcome the damage caused by trauma at such a young age.

26 notes

·

View notes

Link

One Million Moms: How can we demonstrate to the American people that we’re pro-family values?

Conservatives: Hmmm…maybe you could shame and attack a sweet little eleven-year-old girl simply for having two dads?

One Million Moms: OMG YASSSSS NAILED IT

585 notes

·

View notes

Quote

“In a context in which 95 percent of adoptees are girls, it is important to address questions of how racialized desire might intersect with the construction of Asian female bodies. Cheung (2000), for example, argues that in American cultural history Asian women have been endowed with an “excess” of womanhood (alongside the full manhood denied Asian men). And in China/U.S. adoption, mothers Deena Houston and Jackie Kovich were not alone in conjuring the image of beautiful, enthralling Chinese girls. Adoption agencies consistently use photos of cute, dolled-up Asian girls in their advertising; some use phrases such as “From China with Love” to attract would-be parents. Some of those prospective parents said they had become enchanted with their friends’ or neighbors’ Chinese girls. Margaret Jennings said she saw a photo of a Chinese adopted girl in the paper and “knew I wanted to adopt from China right then.” Some expressed embarrassment at what they suspected hinted at “racist love”— embrace of the “acceptable model” of the racial minority (Chan 1972, quoted in Cheung 2000: 309). Just days after she had met her daughter, Barbara and I were discussing what seemed among some new adoptive mothers an obsession with dolling up their daughters, when Barbara stopped to say in a low tone, “I hate to ask this, but are all the children beautiful? It seems like they’re all beautiful.”

Sara Dorow, “Why China?: Identifying Histories of Transnational Adoption,” Asian American Studies Now (2010) (via wocinsolidarity)

652 notes

·

View notes

Link

“A few months ago, in therapy, I found myself uttering the following words: “But if I’m not a good girl, who will want to keep me?” I am 31 years old and I still feel as though I owe this picture, my white parents, something impossible: my silent gratitude. I still feel that if I dare to question, challenge, or speak truth to my snapshots as a black transracial adoptee, I will be “sent back” or “unadopted” for being ungrateful. What happens if I say to them:

Look, I have often felt unseen in your home, your home in which I was in many ways expected to live up to the myth of colorblindness. Your love alone does not protect me from the fact of my black skin.”

Necessary Reading. Required reading. Especially if you plan to transracially adopt or foster. Get uncomfortable. Have the conversations. Reposting and will post again. Please share.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

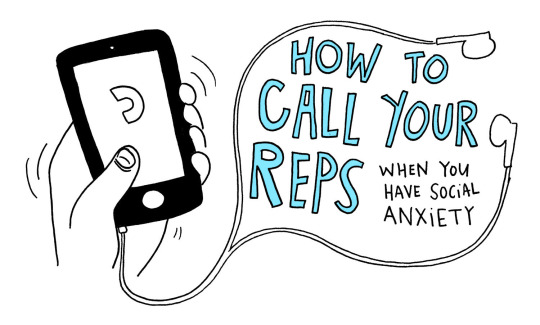

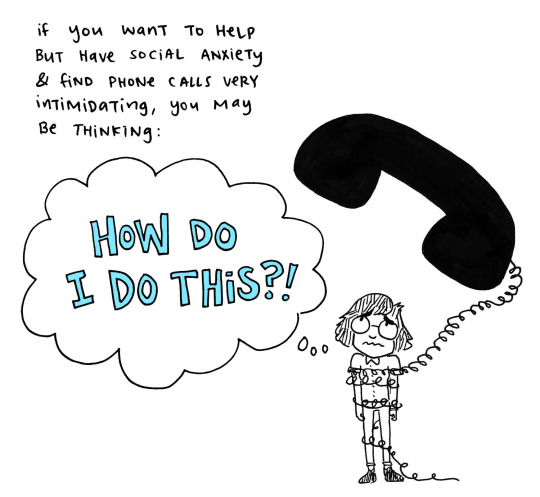

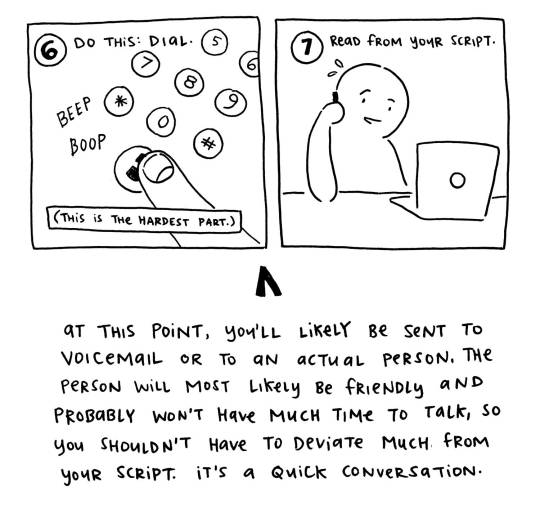

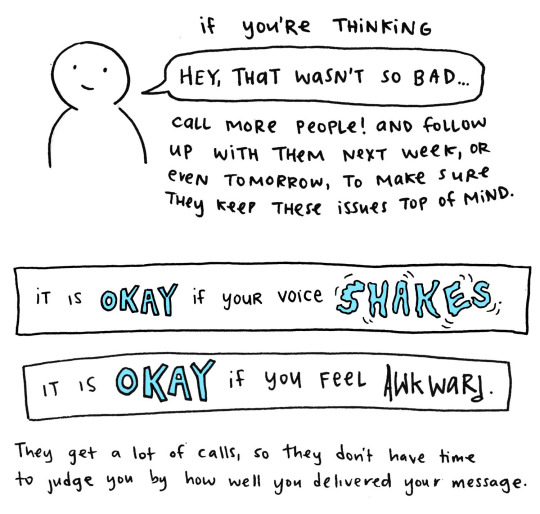

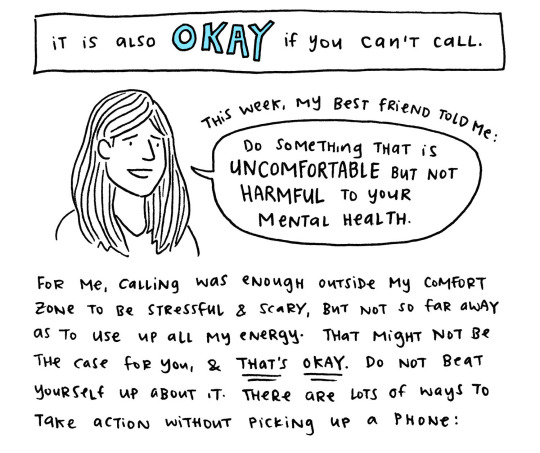

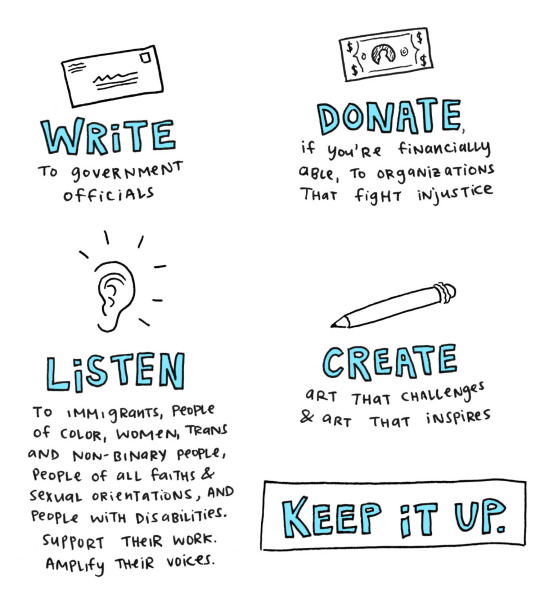

How to call your reps when you have social anxiety

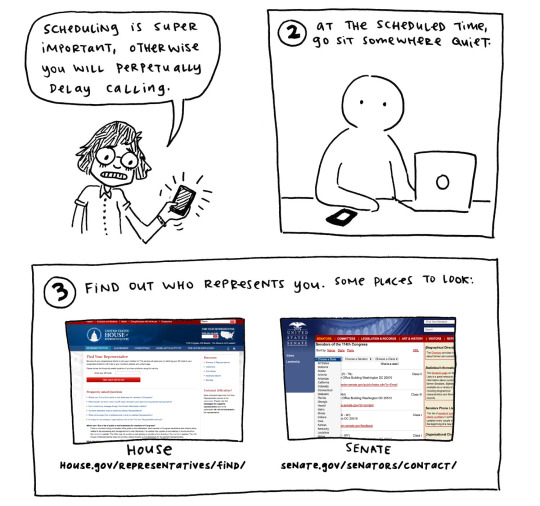

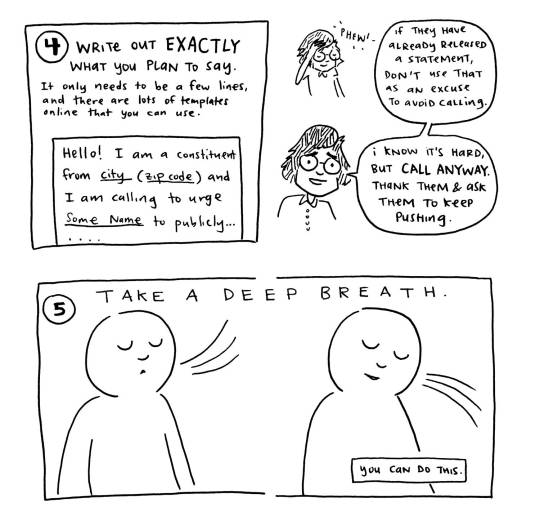

When you struggle with your mental health on a daily basis, it can be hard to take action on the things that matter most to you. The mental barriers anxiety creates often appear insurmountable. But sometimes, when you really need to, you can break those barriers down. This week, with encouragement from some great people on the internet, I pushed against my anxiety and made some calls to members of our government. Here’s a comic about how you can do that, too. (Resources and transcript below.)

Motivational resources:

There are a lot! Here are a few I really like:

Emily Ellsworth explains why calling is the most effective way to reach your congressperson.

Sharon Wong posted a great series of tweets that helped me manage my phone anxiety and make some calls.

Kelsey is tweeting pretty much daily with advice and reminders about calling representatives. I found this tweet an especially great reminder that calls aren’t nearly as big a deal as anxiety makes them out to be.

Informational resources:

There are a lot of these, as well! These three are good places to start:

Find your representative at house.gov

Find your senators at senate.gov

Use the “We’re His Problem Now” scripts when calling (or write your own!)

Keep reading

71K notes

·

View notes

Quote

I first found out that I was supposed to have a teddy bear when I unsealed my uncensored adoption file[…] I remember pouring through those records and stopping at the place where an adoption worker had recorded something to the nature of ‘the birth mother has purchased some things she would like to go with the baby. A small stuffed bear and a few outfits.’

I immediately telephoned my adoptive mother and the first words out of my mouth were ‘mom, do you know where my bear and outfits from my first mother are?’ She told me that she was never given a bear or any outfits that were specified as being gifts from my first mother. I realize now she was caught off-guard by how devastated I seemed about a bear and clothing from nearly 25 years before.

A lot of adoption-related literature that I have read carries the conventional wisdom that at the time, it was not considered appropriate for the adoptive family to accept gifts and items from the original family. One source even said it was OK for adoption workers to tell the adoptee’s first mother they would give an item to the adoptive parents to appease the mother. However, to actually do it was not acceptable because it was thought to be disturbing to the adoptive family.

I am aware of how insignificant this must seem to outsiders ‘looking in’ and perhaps how trivial it seems for me to be upset about, of all things, a teddy bear.

Amanda H.L. Transue-Woolston

Read the whole story of how the author finally found her birth mother and learned the teddy bear intended for her was a one of a pair that her birth mother had carefully selected, giving one to her daughter and keeping one for herself so that they “would always be connected.” /FEELS

(via

brandx

)

So, it’s not okay to take a stuffed animal, but it is okay to take a baby?

Horrendous.

(via crypticomega)

414 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adoptees’ stories are not yours.

Maybe I shouldn’t be angry; I’ve seen this kind of nonsense so many times. But I’m still angry. You cannot claim you’re for birth mothers, adoptees, and unborn life when a) plenty of birth mothers don’t/didn’t have many choices, if any, and b) many adoptees are pro-choice.

I’m so tired of seeing adoptees’ stories co-opted as an “adoption, not abortion!” mantra. Most of the time, these folks have no clue how hard adoption really is, how much it costs, and how much emotional labor is needed from everyone involved.

For me, the bottom line is: our stories are not yours to steal for your own anti-choice purposes. They are not yours to tear apart and use parts of to fit your own agenda. They are ours, and for many of us, they’ve been difficult and even painful to share. Leave adoptees alone.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

To my white mother:

When I was 10 months old, you brought a Punjabi Indian and Cantonese Chinese girl to America. You raised her as one of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

When I was 5, you took me to a party hosted by Chinese people. When you found out it was a holiday, you told me we had to leave because it was a celebration of a false religious holiday. When I cried, you yelled about pleasing Jehovah and not worshipping the devil. We never went to any cultural events again and you acted like my cultures didn’t exist.

When I was 13, you made me throw away the bindis my friend gave me and told me Jehovah was proud of me for throwing away a symbol of false religion and standing up for him.

When I was 14, the elders in your congregation told me I couldn’t wear sarees and Punjabi suits. You packed them away instead of standing up for me. Even though the elders later revoked their decision after the circuit overseer* told them to, I still remember how you went along with them. You scrubbed the mehndi off my arm for an hour because a congregation elder told you I couldn’t participate in preaching activities because it looked like a tattoo.

When I was 15, you let me wear sarees to an assembly*, where dozens of white people stopped and took pictures with me as if I was a zoo exhibit. You told me to smile and be polite.

When I was 17, we moved to a more racially diverse area where the people didn’t care about my clothing and mehndi and you let me wear them again.

Last week, you decided to start learning Hindi with me, forgetting the legacy you left me.

Last week, you decided you could use me as a path to convert people. You decided my heritage is convenient for you.

Yesterday you told me I could only spend time with the Desi kids at my college if I tried to preach to them.

Today I am declaring that I will be Desi with or without your permission. I am immune to your paintbrush, white as snow, caustic as bleach.

Today I am declaring that you don’t get access to my people’s dances, mehndi, clothing, food, bindis, holidays, languages and jewelry when you tore them from me to conform to the standards of white, male Jehovah’s Witnesses. I might not even want to share any of it.

You can rub the mehndi off, toss away the bindis, break the bangles, tear off my salwar kameez, hold my shoulders down, but the strength of my people will always flow in my blood like the Five Rivers.

*a circuit overseer is a man who travels to congregations of Jehovah’s Witnesses and gives them council. An assembly is a big meeting of Jehovah’s Witnesses, this one was 3 days and in the summer.

6K notes

·

View notes

Note

So I'm not even 20 yet but I've always wanted to adopt ( my family has a history of things going wrong on both ends) but lately I've been seeing things online and reading up on it and so much can go wrong it's really discouraging any advice?

the most important thing to start with is to educate yourself. read stories from adoptees and families, international and domestic. read up on the agencies that exist where you live. talk to adoptees about their experiences. all this will help you make an informed decision that will help you be the best parent whether you eventually adopt or not.

a second very important thing to remember is: you are not owed a baby. the world/the adoption agency or service/the biological mother does not owe you a child. you are not entitled to a baby, so make sure you keep in mind that you are treating the system, and the child, with respect.

if you decide to adopt internationally: PLEASE do your research and make sure that the country and agency are reputable and will allow for future contact should your child decide they want to find their biological family, if possible. different countries have varying levels of ability in this regard, but they should prioritize the health and well being of the child above anything else.

if you adopt transracially: your child should not be your first friend of that race. before you adopt, try to spend time with members of that community and learn about their experiences. this will help you prepare to support your child as they navigate through the world, because their experiences will be different from yours.

adoption can be a wonderfully rewarding experience, but don’t expect it to be 100% fun and sunshine. there will be struggle, and disappointment, and painful experiences. that’s all part of the parenthood journey. you have plenty of time to make decisions about how and when you want to become a parent, so use that time to be as educated as possible so you can make the best decision.

-Mod R

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

i watched this video with my mother, who is white, over the weekend. it made her cry. and then this was her reaction: “I’m still not sorry i brought you over here.”

i think one of the biggest struggles as a transracial adoptee is that when we express our frustration with our experiences, our adoptive parents can read that as criticism of them as parents. it’s so hard to explain that yes, i love my family and i am so glad that i was adopted, but that doesn’t mean my life is all sunshine and rainbows all the time. i still face racism in a variety of ways, and as much as i love my parents, i don’t think they were 100% prepared to answer the tough questions about race and prejudice that came up at several points during my childhood and early adulthood.

i can criticize the structure and the deficiencies of international adoption and still appreciate that i wouldn’t be here if it didn’t exist.

More on this later as i gather my thoughts. others want to weigh in?

- Mod R

NY Times video about racism against Asian Americans is facing a backlash from the Asian community

On Thursday, the New York Times published a video about the racism that Asian-Americans face every day, a compilation of stories gathered from the hashtag #ThisIs2016. But because the video erases the complex reality of being Asian American, two marginalized groups are not on board.

follow @the-movemnt

3K notes

·

View notes

Link

Rachel: Why was it important to you to write this book, offering it to not only parents by adoption, but also adoptees, siblings of adoptees, educators, social workers, and therapists? What are you reading, seeing, and hearing in the transracial adoption community that inspired you to write your book?

Ms. Roorda: In the last twenty years as I have traveled across country listening to transracial adoptive parents (most who have been white), white non-adopted siblings, and transracial adoptees from various racial and cultural backgrounds, I have found that most of the transracial adoptive families that I interacted with lived in predominately white communities, had primarily white social networks, and attended mostly white places of worship. This pattern is reflected in over 40 years of research on transracial adoption and documented in the Simon-Roorda trilogy of books on transracial adoption. The bottom line is that most of these families did not have meaningful and sustainable relationships with persons that looked like the children they adopted.

As the transracial adoption movement has matured, there has been more emphasis, compared to the early ’70s and ’80s, on carving out tangible avenues for transracial adoptive families to learn more about their child of color’s racial and ethnic background(s) and grappling with the challenges that face adult transracial adoptees such as through attending culture camps, reading books by and about transracial adoptees and other people color, and watching documentaries featuring adult transracial adoptees. Still most transracial adoptees from all racial/cultural backgrounds raised in white homes rarely see someone who looks like them sitting at their dinner table, partnering with their parents in equitable ways, or investing in their lives as mentors or even godparents. This striking gap in the long (and short) run negatively impacts every member of the transracial adoptive family unit. Why? Because we now know from research that when there is minimal immersion and comfort level among transracial adoptive families in the communities of color in which these adopted children come from, members of the family, particularly the transracial adoptee, are left to rely on stereotypes and shattered images of their true selves.

I wrote In Their Voices: Black Americans on Transracial Adoption to narrow the experiential gap between white transracial adoptive parents and members in the black community. I wanted to show that black Americans are just as diverse in thought and action as white Americans, and that everyone has a story.

In the process of writing this book and interviewing incredible people, from the first black Mayor of Philadelphia to the great Grandson of W.E.B. DuBois and to a foster care alumna and transracial adoptee, I too learned that I was going to have to replace my own colorblind glasses with more multidimensional ones.

The biggest lesson I learned was that the answers or struggles many white transracial adoptive parents eventually will have to come to terms with are the same realities that black parents raising black children deal with. Transracial adoptive parents are craving to find answers on ways to help prepare their black and brown children to grow into successful adults… of color. Sadly, for over forty-five years, the transracial adoption world has looked only in white spaces for these answers. Truly absorbing this reality as a transracial adoptee myself nearly put me in a fetal position. It simply does not make sense!

In Their Voices is an attempt to bring incredible men and women of color into the living rooms of our transracial adoptive families in this country and around the world. It allows the reader to hear from these individuals the challenges they struggle with in raising black children in a society that still measures someone’s character by the color of their skin and not by the content of their character; and how they work to move forward in positive ways going around this obstacles. The reader gets to feel the rhythm of each person I talk with, their intensity around issues of race and discrimination, their joy of who they are, and their deep concern and support of transracial adoptive families. The words of wisdom each one of the people I interviewed shares is of tremendous value to our families. This book for me is a gift to my inner child. It allows me to breathe…

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t talk about it much on this platform, but there are times when I’m really overwhelmed by being a brown person raised by white people in a predominantly white culture. Transracial adoption can be tough to figure out. It’s hard to feel like I’m ‘allowed’ to have feelings about being ‘brown’ when I think about how I often feel as though I was raised ‘white’, when I think about how I’m very much aware of my white privilege every day, when I think about how fortunate I am for my incredible family in addition to the ‘how in the hell does one get so lucky’ type of life I’ve had…it’s just there are these moments where I feel like I struggle to be OK with allowing myself to take part in identifying as ‘brown’, as ‘latina’, as ‘Colombian’. It’s hard when you feel like you don’t truly belong in either a brown or white culture, but you’re somewhere in between.

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top Ten List for Transracial Adoptive Parents

Adoption is not like purchasing a Prada bag. It is not hip and trendy. You are not cool for adopting. You are becoming a parent. This is a child - a human being. This child is an enormous blessing that should not be taken for granted or used to fulfill your need to feel good about yourself. If this about “saving the child,” you are adopting for the wrong reasons. You are not the child’s superhero. You are, for all practical purposes, stripping this child from their country of origin, family, culture, and everything else that matters. Regardless of how difficult their life may be in the country of origin, this is still the reality. I hope you are ready to deal with issues related to this reality.

I have engaged in numerous conversations with transracial adoptees who feel their adoptive families and parents do not understand them. They feel invalidated regarding issues related to loss and abandonment and discounted for their experiences with racism. Many believe their parents adopted them so they could show others how sacrificial they are - the ultimate points on a parenting scorecard. Some speak of parents who expect them to be thankful for “saving them from a life of destitute.” It doesn’t matter that the adopted child has questions about their country or culture of origin, biological parents, details about the adoption, etc. It only matters to the parents that they rescued them. Every story, at some level, resonates with me. We have more information regarding how to support transracial adoptees now – this means parents are even more accountable. I never blame people for ignorance. You don’t know what you don’t know. But once you are aware, you are responsible for that information. You can no longer say, “I didn’t know.”

After conducting over 4 years of research in this area and continuous conversations with many transracial adoptees, I think it is time for adoptive parents to hear our perspective. I hope that this list encourages dialogue between you and your adopted child, compassion and empathy for their life experiences, and an open mind to truly listen and support.

For White parents adopting non-White children…

1. Before adopting, educate yourself on racial dynamics in the U.S. - your child WILL experience racism and how you respond will be pivotal to how they perceive you as a support person or just another White person who chooses to believe race is no longer an issue.

2. Do NOT raise your child to be color blind. Color is beautiful. When you say, “I don’t see color,” you are saying you don’t see your beautiful child. Talk about race. Do not make race a taboo topic; that sends the message to your child that race/color is bad, and therefore there must be something wrong with them.

3. Do not let the first person to show support be a peer or teacher. Your child should be getting emotional and psychological support at home. When your child comes home crying and tells you that a kid teased him/her about their skin color, facial features, hair texture, etc. PLEASE DO NOT respond with, “Just ignore them” or “It’s okay, Jesus loves you.” Call it what it is. VALIDATE your child’s experience. It’s called racism and it is unacceptable. Then discuss appropriate ways to respond to ignorant people.

4. Encourage your child to explore their identity. My research (2011 showed that ethnic/racial, White, and adoptee identity are all salient identities for transracial adoptees. This means that (Korean adoptees as an example), many transracial KAAs identify with being a racial and ethnic being, may “feel white,” and have a strong connection to being adopted. Transracial adoptees experience life in a unique way because they are being raised by families and in communities that do not look like them. This is not a bad thing, but you must be open to the uniqueness of their experience and validate their feelings in times of identity crisis.

5. If they decide to seek out their birth parents, do not make this about you. Guilt-tripping a child for wanting answers is sick and wrong, and that’s a reflection of your own insecurities. As a parent, you should WANT your child to be healthy and whole.

6. Introduce them (if they are open) to their culture of origin so they have an appreciation of and connection to their heritage. My research showed that adoptees felt they were “missing” something because they could not speak their language of origin and/or knew nothing or little about Korean culture. They didn’t feel Korean or Asian enough around other Koreans and Asians, and they weren’t white, either. “Missing pieces” also included lack of medical records or an incomplete story regarding their adoption. Adoptees live in “the in-between.” If your child is not interested in finding answers (which may be the case because they are not emotionally or developmentally ready), this is fine - but at least offer the opportunities. Make it their decision. Empower them.

7. Connect them to other adoptees. Shared experiences are powerful.

8. Just be open. Open to dialogue, open to tough conversations, open to their exploration. The best gift you can give is support. Again, DO NOT make this about you. That is a reflection of your own insecurities.

9. Your children are NOT White. They may have a strong connection to White culture, but they do not benefit from White privilege. The sooner you accept them as racial beings and understand how your racial experiences are different because you are not brown, the more supportive you can be.

10. If you do not believe in White privilege, you should not be adopting a non-White child. If you are willing to pour hours into parenting books, you should be open to learning about how your child’s life experiences will differ from yours, simply because they have brown skin.

© Joy Lynn Song Hoffman, 2013

Adopted through Holt International, 1968

1K notes

·

View notes