Photo

The Irish word for “a man” is fear [FARR]. The plural is fir [FIRR], which is as irregular as it is in English.

The Irish word for “a woman” is bean [BAN]. The plural is mná, which again is as irregular as it is in English.

You might see “FIR” and “MNÁ” written over older public toilets in Ireland and draw the natural analogy with “M for male and F for female” which seems to hold good for so many other European languages. Alas, you would be sadly mistaken.

Irish people being what they are, no one will tell you about this beforehand, and people in there of the opposite sex will act as though everything is fine. Don’t be fooled. They are judging you.

114 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Here is a sign on a motorway in Ireland, I’m guessing somewhere near Kilcullen. It says Maraíonn Tuirse [mar-EE-in TIRR-sheh], which does indeed mean “tirednes kills” but there’s a problem.

The English verb “to kill” can be transitive or intransitive. “Transitive” means that it takes an object. It’s a fancy term for a verb that has to do something to something else.

“John killed Paul”: the killing is happening to Paul, and therefore the verb is transitive.

“John killed every night”: the killing is sort of left hanging in the air. Either he is massacring people indiscriminately or he is absolutely smashing his residency at the comedy club. The verb is intransitive.

Maraíonn is the the third-person present tense of the verb maraigh [MAR-igg]. It means “to kill” and it is a transitive verb. It takes an object. It has to do something to something else.

On the sign it’s just sort of left hanging there so when you’re zooming down the motorway, your first response is “kills what?”

169 notes

·

View notes

Photo

For decades, a legion of Gaeilgeoirí and government institutions told us that “the way it's being taught” was not the problem and sharing our experiences of mandatory depressing Irish classes was unhelpful. Now it looks like Irish language organisations and teachers are finally coming around.

Irish language organisations such as Conradh na Gaeilge and An Gréasán with the support of second and third-level student unions USI and ISSU, as well as teacher unions the TUI and ASTI, have said that Irish language education is a “broken system”.

The TL;DR is that learning Irish solves no problems. For more on this, see my previous blog posts:

Why No One Speaks Irish

My Position on the Irish Language

None Of This Is New

Marketing In Irish Advertises A Disaster

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irish Jokes

Someone on Instagram is posting jokes in Irish and you might like to follow them.

34 notes

·

View notes

Video

This is from the delightful corrections compilation of the Seth Meyers talk show from last week. Let’s leave aside the lazy “drunk” joke for the moment. And for ever.

As he says, the “correct” pronunciation of Taoiseach is [TEE-shokh]. I’ve got some pushback on Twitter from some professional Irish teachers for saying on here that the initial T there is more like a hard TH, like you’d find in the English word WIDTH, which would mean that it’s pronounced DTHEE-shokh.

Apparently that’s not the “official” pronunciation, but among native speakers, you’ll hear a lot of DTHEE-shokh, with the first hard TH sound and where the last syllable is less of an O and more of a schwa, i.e. the quickest, least disruptive way you can get your mouth from one consonant to another.

I’ll continue to mark out pronunciations as I have heard them rather than what they are “supposed” to be.

Related: Terms of Government

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Huge, as they say, if true. Of course it is true, in the sense that Duolingo’s data demonstrates that “over 1 million people” are “actively learning Irish every week” on it.

The question is: Does this represent a resurgence of Irish as a spoken language? Or can it be more easily explained by bored people adopting one more hobby to palliate the endless free time offered by a pandemic lockdown?

We won’t know the answer until much later, but I would obviously hope for the former.

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

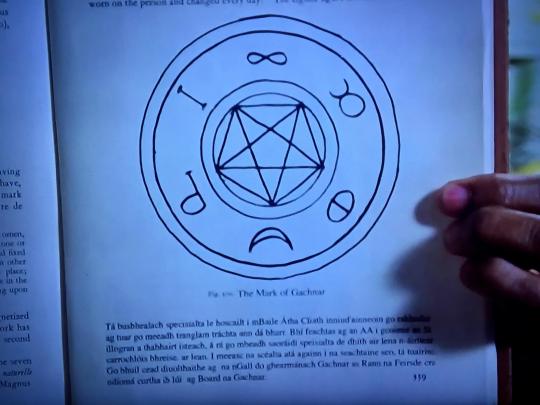

You remember Buffy the Vampire Slayer, right? It was a show about a Valley girl who was ordained by fate to kill vampires. It was a lot of fun.

In the fourth episode of the fourth season (Fear, Itself), a demon is accidentally summoned. The above is a screencap of the book with the summoning spell. The text under The Mark of Gachnar is Irish.

A translation starts like this: “A special bus lane is to be opened in Dublin...” and continues in a similar riveting vein.

Should Hollywood be lobbied to make Irish their go-to demon language in all their movies instead of Latin? Sure. Why not? It has to be more interesting than, "Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit..."

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Slagging

In Ireland, part of the social landscape is what we call “slagging”, various levels of mockery and sarcasm and personal abuse weaponised as affection among groups of friends and family.

If you accidentally wander into the field of fire, try to remember that we’re not making fun of you; it’s just how Irish people are. Or, to be more accurate, we are making fun of you but it’s just how Irish people are. If you’re able to give it back, feel free to do so, but it’s a fine line.

Reginald D. Hunter tells the extraordinary tale of how he met his manager when an Irish guy rolled up after a gig and introduced himself with, “Jesus you’re a big, mean-looking cunt!”

When Reg’s friends adopted a combat stance, he told them it was all right because “I speak Irish”.

Some of this may sound familiar to any Americans who are into underground comedy clubs, because it’s basically a roast battle, except you didn’t sign up to be the victim, and it might last forever.

If you object to the vituperative invective, you will be met with the riposte, “I’m only slagging,” and everyone in the room will side with your attacker. In fact, slagging is so much part of what we do, we find it unthinkable if someone objects.

So what can explain this culture of socially-sanctioned bullying?

Maybe it’s related to the fact that Irish people are among the most repressed in the world. We are uncomfortable talking about genuine feelings, sexuality, mental health, and Mark Twain’s two eminently avoidable conversation topic, politics and religion. You might think that everyone finds these things difficult to discuss, but Irish people have some next-level avoidance strategies (although we’re getting better).

The two greatest avoidance strategies have historically been alcoholism and freestyle abuse, both of which can be connected, and both of which will be presented as “a bit of craic,” i.e. the kind of thing that only an antisocial curmudgeon would begrudge his peers.

So, in the absence of actual meaningful dialogue, slagging has become a tool of communication. We all do it. I do it. And for all I know, it might be saving lives.

Just don’t take any of it personally.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

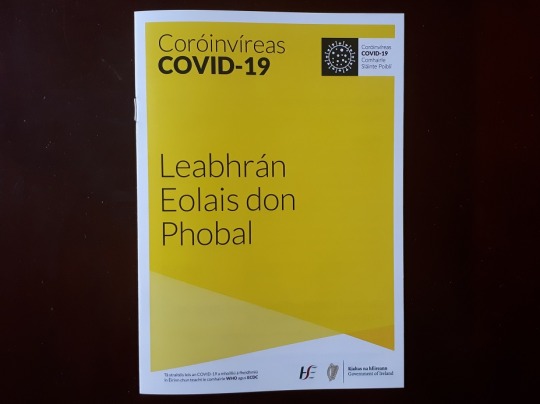

This came in the post today. It’s the Irish version of the booklet I received in the post last week about some basic Coronavirus protocols.

Coróinvíreas obviously means coronavirus. I sometimes criticise the Irish language for having ridiculous loan-words because they sound forced, but they get a free pass on this. Every language will have something similar.

There is no V in Irish. If you see a V in an Irish word, like this, it is a guaranteed sign that we’ve imported a word from a different language. The V sound, however, is very common in Irish and is made by adjusting the B sound (and sometimes the M sound) in a consonant weakening process called lenition. This process is marked with a H after the letter, called a séimhiú [SHAY-voo].

balla [BALLA] = a wall

sa bhalla [SUH VALLA] - in a wall

The Comhairle Sláinte Phobal in the white box at the top right means “Advice Health Public”, or whatever order you’d put that in for English. Pobal [PUBBLE] is the Irish for “public”, and the H is another lenition, so it’s [FUBBLE].

Leabhrán Eolais don Phobal means “Booklet Information for Public”, or whatever order you’d put that in for English. The Irish for “book” is leabhar [LAU-er] and even if you’ve never seen it before, if you have a basic handle on Irish, you’ll at least suspect that leabhrán [lau-RAWN] means “booklet”.

Follow the medical advice and stay safe!

12 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

This is a clip from the Irish version of First Dates, a reality television show about arranging blind dates for people and setting in motion a series of events which will result in the most painful experience of their lives.

Sorry. I’m going through a divorce. I’m fine. I’m a bit emotionally vulnerable right now, but everything’s going to be fine.

First of all, Ailbhe is delightful in every single way it’s possible to determine these things from a five-minute clip on YouTube. Everything about her is lovely. No notes. Keep doing what you’re doing, Ailbhe.

Secondly, she is a very rare sort of Irish person: a native Irish speaker from Donegal. This means, as she explains in the clip, she had to go to school to learn English. This is almost unheard-of in Ireland.

Thirdly, keep in mind that this version of the programme is exclusively broadcast in Ireland and Irish people are the intended audience.

As you watch, you will notice that her Irish dialogue is subtitled into English. This is not to make concessions for tourists, but so that Irish people can understand what she is saying. Despite the fact that her Irish is perfectly comprehensible, the producers (correctly) felt insecure enough to put subtitles on it.

This is the lived reality of the condition of the Irish language in Ireland.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello Fada

If you’re on a PC, you can get all the accented vowels by using CTRL+ALT+[letter].

CTRL+ALT+a = á

CTRL+ALT+e = é

CTRL+ALT+i = í

CTRL+ALT+o = ó

CTRL+ALT+u = ú

Please do not make fun of me for being a million years old, but I have literally been copying and pasting the accented letters from the character map. While I’m sure this “tip” is completely obvious to most of you, if it helps even one person type Irish more easily, then my work here is done.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ní Bheidh A Leithéid Ann Arís.

DISCLAIMER: This is an opinion piece and many of those interested in the Irish language will violently disagree with these opinions. Hopefully, even these people would concede, however reluctantly, that it is possible to be interested in the Irish language without buying into the mythology surrounding it.

Gaeilgeoirí are, according to the Irish Wikipedia, people who speak Irish, although it has heavy connotations of someone who is passionate about the language. Other people often view Gaeilgeoirí the same way other people view vegetarians, or atheists, i.e., that’s great, but keep it to yourself.

Although they themselves make up a diverse group, Gaeilgeoirí sometimes imagine that Ireland is divided into two types of people: those who are passionate about Irish, and those who are actively opposed to Irish. Even raising these questions can invite a tidal wave of abuse from a legion of passionate young people eager to put you in a box usually reserved for the Dúchrónaigh or Lord Trevelyan.

In fact, the vast majority of Irish people don’t think about the Irish language at all unless they are specifically asked to do so, which for most people involves lying on a census form once every six years. Even Gaeilgeoirí only ever seem to talk about (or in) Irish when the subject matter is the Irish language itself, and many of their responses to even the most uncontroversial realities seem to revolve around the idea that they’re victims of a mass gaslighting operation rather than presenting actual arguments in favour of their position.

Gaeilgeoirí refuse to accept that the Irish language is dead, and point to examples of people using Irish, signal-boosting Irish, Irish use in the media, and so on. In their defence, there is little consensus among linguists regarding the criteria for a dead language, but the reality is that literally every single person who speaks Irish also speaks English, and in the majority of cases, even native Irish speakers speak English better.

We are told by Gaeilgeoirí that Irish is a living language that just needs help, and that it’s almost on the verge of a come-back (often ironically by the same people who assure us that Irish is not in a place from which a come-back would be required). We are also told that the prevalence of English in ostensibly Irish-only areas is a new development which must be tackled urgently.

Because Gaeilgeoirí frame these issues as an urgent, existential matter, it can be surprising to learn that these problems date to the birth of the Irish Free State, as this government debate from 1928 demonstrates. There’s a fantastic bit around the middle where Patrick Hogan relates how his journeys in the Gaeltacht were met not only with widespread indifference, but hostile reactions to his insistence on speaking Irish.

None of this is new. Don’t let anyone tell you any different.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

There’s a lot to unpack here. Mainly because it’s a hamper of Irish-themed goodies for ex-pats to help them remember their homeland. There are lots of companies that provide this service. You can see bits of various consumer products redolent of an Irish childhood that I cropped out around the edge.

This blog was supposed to be about Irish language and culture. There’s probably too much language and not enough culture, so the plan is to go through those phrases one by one and explain what’s going on. As I have had an extremely sheltered and extremely middle-class upbringing, I did not write this post entirely on my own.

“It’s jammers in there”: The word “jammers” is Dublin slang for “crowded” (to an off-putting degree). You don’t need to say “in there”. Anywhere can simply be “jammers”. However, there is a greater than zero chance that this quote was specifically referring to “Copper’s” on Harcourt St. in Dublin, for reasons I don’t have time to explore.

“Come here to me”: this is something Irish people say before they tell you something they feel you should be listening to, instead of just cruising through on autopilot like you usually do.

“On the pull”: Actively searching for real-world romantic activity. Probably also in Copper’s.

“Bye, bye, bye, bye, bye, bye”: This is the standard end of a phone call with someone you know.

“Ya bleedin’ tick”: This is more Dublin slang, more properly rendered as “you bleeding thick”. (Dublin has about 50% of the population of the entire country, so it’s fine if there’s lots of Dublin stuff in something labelled “Ireland”.) This refers to someone doing or something something stupid. Not to be confused with “getting thick” which does not, as you may imagine, mean “putting on weight”, but “becoming angry”.

“Howiya?”: The standard Irish greeting: How are you? The only correct answer is: “Grand.”

“Ah, sure look”: This can be an invitation to end a conversation, or a non-committal attempt to empathise.

“Muck savage”: An urban pejorative term for someone from a rural area. The word “culchie” is also used here.

“Fire away”: This is said when someone wants to ask you something or tell you something. This gives them enthusiastic consent to do so.

“The craic is 90”: This just means we’re all having a lot of fun.

“Come on you boys in green”: Often shortened on Twitter to #COYBIG, this is an expression of support for any of our sports teams, including the women (as, apparently, “come on you girls in green” comes across a bit patronising).

“Jo Maxi”: I’m not entirely sure, but there was a programme on our national television station aimed at young people many years ago called Jo Maxi. Maybe it’s a reference to that. (Update: A kind follower below tells me it means “taxi”. Thanks, follower.)

“You’re taking the absolute piss”: This is to highlight a ridiculous situation, or to signal that the burden of proof is now on the shoulders of the other person.

Now you know.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

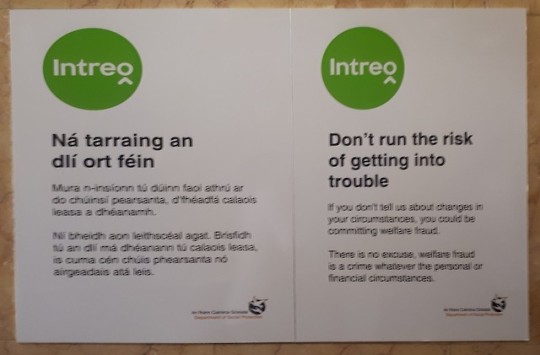

This is a sign in the unemployment office where I had to present myself to the elders of the village as “capable and actively seeking work” this afternoon.

This is the Irish text:

Ná tarraing an dlí ort féin

Mura n-insíonn tú dúinn faoi athrú ar do chúinsí pearsanta, d'fhéadfá calaois leasa a dhéanamh.

Ní bheidh aon leithscéal agat. Brisfidh tú an dlí má dhéanann tú calaois leasa, is cuma cén cúinsí pearsanta nó airgeadais ata leis.

The actual translation of the Irish text is a bit more abrupt than their translation indicates:

Don’t pull the law onto yourself

If you don’t tell us about changes in your personal circumstances, you could do (i.e. commit) welfare fraud.

You won’t have any excuse. You will break the law if you do welfare fraud, it doesn’t matter what personal or financial circumstances are with it.

This sort of thing happens quite often. From watching foreign TV shows on Netflix, it is not unique to Irish. It’s not a mistake, as such, but translators are professionally motivated to try to work out the meaning of a sentence and translate that rather than translating sentences directly.

While this results in far more readable translations, it often means that you’re getting what the translator thought it should have said rather than what it actually said.

This isn’t anyone’s fault. No one is “doing it wrong”. It’s just an observation about translations and to be aware that there are different approaches to it. Language is a slippery eel to nail down. All attempts so far have failed.

Related: To illustrate the nightmare of translation, take a journey with me when I tried to translate the first sentence of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis from German into English.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review of “Motherfoclóir”

This is my review of Motherfoclóir, by Darach O'Seaghdha, who maintains the The Irish For Twitter account, and an associated podcast. You can buy the book here.

There’s good news and there’s bad news. I’m going to start with the good news, and to be fair, most of the bad news is mean-spirited and deeply unnecessary punctiliousness, but, as my followers will be aware, that’s never stopped me before.

The Good News

This is a very good book. There is no doubt whatever about that. It’s written in a relatable, informal style, and it’s full of heartwarming stories from O'Seaghdha’s personal life without coming across as mawkish or twee. It’s a difficult balance for even veteran writers, but he manages it with ease.

The book is interesting and reading it is fun, full of little jokes, and self-referential ironic barbs at the expense of how awful Irish people can be, tempered with fairly straight-forward references to how great Irish people can be, which is exactly the sort of tone you need in a book like this.

I would recommend Motherfoclóir to anyone interested in the Irish language, or the Irish people, or anyone who wants to be entertained by a great read.

The Bad News

This book will be useless if you are expecting to learn how to speak Irish, or anything along those lines. In much the same way as the Old Testament should not be seen as a source of accurate historical information, but rather a stylised, metaphorical chronicle of the relationship between the Jewish people and their god, this book should not be seen as anything other than one man’s relationship with his ancestral language.

At the start of the book, O'Seaghdha claims that he won’t get into certain hot-button issues for both Gaeilgeoirí and non-Gaeilgeoirí, like the much-needed reformation of the education system, or various political matters surrounding the language, but then spends later pages doing just that. It was perhaps unavoidable.

There are lots of Irish phrases and explanations that I would personally disagree with, but I’m assuming that’s the result of his particular dialect (there are three main Irish dialects and sometimes they are wildly divergent). I’m certainly not going to get into a list of “corrections” that could afterwards turn out to not be corrections at all.

The central difficulty with the Irish language isn’t that it’s especially hard, or that people have an irrational dislike of it after negative experiences in the education system (although that might be some of it).

The central difficulty with the Irish language is that it doesn’t solve any problems. There is no one who can speak Irish who doesn’t also speak English (probably better), and the vast majority of Irish speakers will speak English far more than they speak Irish because they want to be understood. In fact, it’s a safe bet that every single person you meet or see who chooses to speak Irish is probably in some way involved in the promotion of the language, or has adopted the Irish language as a hobby.

The Irish language has been “on the verge of a comeback” and “experiencing a resurgence” at least since the dawn of the state (1921). There is no reason to assume that anything very dramatic is going to happen in the future.

This book is written in English, presumably not because O'Seaghdha loves English more than he loves Irish, but because he wants more than ten people to read it.

And hopefully they will.

Buy Motherfoclóir here.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doo Bee Dooby Doo

The Irish language has influenced how Irish people speak English in a number of famous ways.

1.

In rural areas, people say “I do be going to the shops of a Wednesday”, meaning “I go to the shops every Wednesday”. In Irish, there are two present tenses, one meaning something that’s happening right now, and another meaning something that’s happening in an ongoing sense.

If you say “I’m happy”, no one knows if this is an anomaly or an enviable life situation. In Irish, you have to choose. There is no way to express this in English, so they break it down into “I do be happy” (regularly) and “I’m happy” (for the moment but don’t get comfortable).

Something that has happened in the very recent past is indicated by using the form: present tense of “to be” + “after” + verb. “I’m after hurting myself” means “I’ve just hurt myself”.

2.

Irish people often have a hard time giving simple “Yes” or “No” answers, not because they are congenitally shifty, but because there is no simple “Yes” or “No” in the Irish language. There are only positive and negative forms of the verb. The question “Are you happy?” is as likely to be answered with “I am” as the otherwise more common “Yes”.

3.

Irish people of a certain stripe have a famous difficulty with pronouncing the th sound so beloved of the English. There are two th sounds in English: the soft th, such as you might find in words like “the” or “breathe”; and the hard th, such as you might find in words like “thought” and “breath”.

For an English soft th, these Irish people will pronounce a d instead, giving “de” and “breede” in the above examples, and for an English hard th, Irish people will pronounce a t instead, giving “tawt” and “bret” in the above examples.

The Irish language does not have a th sound at all. However, it does have a messy half-way-between sound in words like taoiseach, which would be pronounced “DTHEE-shockh”, where the initial consonant is closer to what English people might say in “width” to distinguish it from “with”. English efforts to pronounce this sound are a consistent source of amusement to any Irish person who listens to BBC Radio 4.

There are many other examples, but t(h)ree is enough for the moment, I should t(h)ink. The next time I do a post like this, I’ll talk about the prodigious swearing of my people. Until then, feck off.

101 notes

·

View notes

Photo

There is a common misunderstanding among Irish language activists that, in the words of celebrated nationalist Patrick Pearse, “when the Irish language disappears, Irish nationality will ipso facto disappear, and for ever.” It explains why the Gaeilgeoirí get so worked up over trivial statements of fact about our language use. They honestly believe they are fighting not just for a language, but the soul of a nation.

There is absolutely no evidence that any of this is true. If anything, the fact that over 90% of Irish people have been living, working and enjoying themselves through English for at least the last century demonstrates how wrong this idea is.

Here is a small sample list:

Country (national languages it has instead of its own)

Switzerland (French, English, German, Italian)

Sudan (Arabic, English)

Brazil (Portuguese)

Austria (German)

Mexico (Spanish)

Niger (French, Arabic)

Argentina (Spanish)

Egypt (Arabic)

Haiti (French)

Canada (English, French)

Nigeria (English)

Each of those countries has a vibrant and distinct culture and heritage even though they use, mostly for reasons of colonialism, what has historically been someone else’s language to express it.

I can only imagine that tourists from any of those places are bemused when they hear some of us talk about our language as though it were the only “authentic” vehicle for our culture.

If you’re interested in Irish, join the club and please follow this blog. But let’s talk about it honestly, not in a fog of aspirational gibberish.

4 notes

·

View notes