Text

How Elwing Lost A Silmaril

The first letter—sealed with an eight-pointed star pressed into red wax and delivered just before dawn—left Elwing trembling in her small office, stomach rolling and the taste of bile thick on her tongue. What was she to do? What could she do? Her parents’ murderers were coming here.

The letter didn’t say as much outright. The writer (Maedhros, she’d learned his name eventually, but he would always be the red-haired orcish monster that took her home away and haunted her worst nightmares) veiled every threat behind eloquent lines of meaningless placations and enteritis for the silmaril. He asked her, granddaughter of a thief, to return it to him, eldest son of its maker and rightful heir. But she could read what he did not say: that if she did not bend to his will he would do to Sirion as he did to Menegroth. He would come with his fell army and slaughter everyone in his way.

But how could she give up the jewel? It protected them, kept the forces of darkness at bay just enough for the refugees to eke out a living on the shores. And should Eärendil, her dear, brave husband, find a path to Aman, its light might be the only thing that could stay the Valar’s Doom long enough for them to listen to him. She could not give up their hope.

The second letter—sealed in red wax and delivered as the barley fields were harvested—brought more promises of horrors unnamed falling upon the settlement. She wept after throwing it in the fire. She could not do this on her own. The city council was terrified into inaction at the thought of what lay before then, and Eärendil was still out at sea. She missed him. She missed him so terribly when the councilors looked at her with fearful eyes and asked for her decision.

The fifth letter arrived in the hands of an underfed Mannish girl as the first winds of winter blew in from the sea. Elwing gave her food and a family offered a spot in their home, but the girl said her lord instructed her to go nowhere else until she had a reply for him. Elwing thought of banishing her from the city unanswered, of telling the guards with their rough-made weapons to see that the Fëanorian did not return. She regretted the thought nearly as soon as she had it. The girl was young and it was not her fault that her parents joined themselves to a mighty Elf lord. She could stay for a day.

Tell me whatsoever you desire, the greatest or smallest need of your heart.

The letter said in handwriting that was fast becoming too familiar.

I will give unto you that thing and greater still if you would part with my father’s Silmaril. I would bring you all the provisions of my camp, all the weapons of my army, every other precious thing of power left in this land if you would but willingly part with that one small thing that I must otherwise be driven to take by force in the spring.

Tell me your desire, and I will give it unto you.

Let this not end with blood.

She fumed in her office, angrily pacing the thin rug gifted to her by the weary-eyed wife of one of her father’s guards who fell in the tunnels of Menegroth. She does not need anything from the murdering bastard! Sirion has all it requires. They would be safe if only they were left alone. How can Maedhros think that he could ever give her anything to make up for what he’s done, to convince her to do what he wants? He’s a monster and a coward who wishes to soothe his conscience by acting as if the attack is all her fault, an inevitable consequence of her resistance. He wishes to absolve himself of yet more evil.

She will not let him. If it is the only thing she can do, she will defy him.

Elwing takes up precious ink and paper. She throws herself into her chair and leans over the beaten desk, pouring her anger and helplessness into the words she scratches across the page.

You’ve taken everything from my people. You wish to take everything from me again. You are monstrous, servant of Morgoth. May the Valar stand against you as I cannot.

What would I have, you ask? I would have what you’ve taken from me restored: I would have Dior, my father, and Nimloth, my mother; I would have Eluréd and Elurín, my brothers, alive again and in my arms. But I shall never have them for they died at your hands and at your command.

You cannot give me my parents. You search for my little brothers but still cannot give them to me.

So, what would I have?

I would have your brothers. Give me your two youngest. I have lost my twin brothers for this gem. You must do the same.

She signed the bottom with a vicious strike that split the quill’s nip, blotting the page with ink as dark as orc blood. Her heartbeat in her chest, thumped against her ribs under her breast as though it would escape fate. Her letter would change nothing and she hesitated for a moment before dripping wax from a flickering candle for the seal, tempted to throw the paper to the fire.

She’d written in a tantrum, a final kicking of her feet against what would come in an impotent rage. But what did it matter? Did she not deserve to beat her fists against the Doom once? Everyone looked to her for leadership and guidance as Dior’s heir but she felt like little more than a child. This would be so much easier to handle with Eärendil at her side but he still had not returned and at times she doubted he ever would (what Doom had befallen him on the waters? What lonely fate for him and the crew on the waves?). She would send this letter then say goodbye to all childishness and face what came bravely as her parents and grandparents did.

Resolved, she dripped the wax and sealed the letter. She’d give it to the messenger tomorrow with what small food they could spare so the girl did not starve on the journey. And then…

And then all would be out of her hands and fate would fall as it would.

The sixth letter came in the hands of two red-haired Elves on tall horses. The men sat straight and tall in the saddle, their heads held high. Elwing would have called them haughty if they hadn’t dismounted and bowed deeply before her, falling to one knee as one might before royalty. A third Elf, dark-haired and somber-eyed, rode with them, though he kept himself aside and astride his steed.

“Queen Elwing,” one of the red-heads said, his face fire-scarred. He paused, waiting for permission to go on.

She nodded and waved her hand impatiently, wondering what new trick Maedhros was playing or if this was how he announced an impending slaughter.

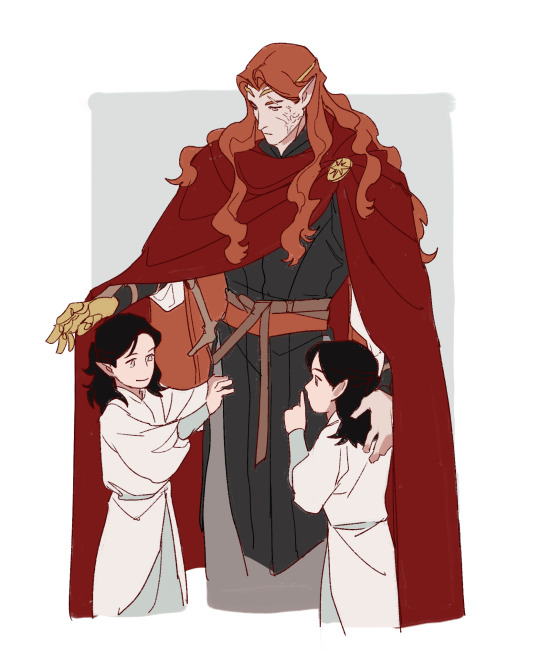

The speaker went on, looking up slightly though he stayed kneeling. “We are Ambarussa–” he gestured to the other– “youngest sons of Fëanor. We give ourselves up at your request in exchange for the silmaril.”

Elwing stood in frozen silence as he continued, icy sea breeze biting at her fingers and face.

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

gay people can never be normal it always gotta be some shit like and the thought of their ancient friendship stung his heart

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not going to be normal about them

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

#!!!!!!!!!!#this Finrod is one of the Finrodest of Finrods that has ever Finroded!#I love them!#i love C&C too!!!#Tell them off Mae#they deserve a good smack

674 notes

·

View notes

Text

the fairest stars: post vi

Beren and Lúthien steal two Silmarils, everything spins out of control, et cetera: we are 78k words and 30 parts into this monster bullet point AU now! Masterpost with links to all previous parts on tumblr and AO3 here.

Part 31: on saving people.

Lúthien finds Maglor in the rose garden.

"I came as soon as I heard," she says, sitting down beside him.

(It isn't a lie – she knows Maglor needs a friend right now. But it is true, also, that Barad Eithel is easier at the moment than thinking of the dull unhappy look in Beren's eyes as they departed Morwen's house, and begged shelter like outlaws with others of the Hadorians.)

Maglor does not look at her. He is staring at his lap, very still.

"Maglor," says Lúthien. She dares to put an arm around him, and then tenses, thinking of Morwen's blank and silent grief, and how she rebuffed all Lúthien’s attempts at comfort.

But Maglor shivers, when she touches him, and then leans against her gratefully.

"I didn't know," Lúthien says. "I'm sorry – I would have stopped him, had I known—"

"How could you have known?" Maglor asks, very heavily. Maglor does not wear his grief gracefully: it is an awful frozen thing, numbing his tongue and coarsening his tuneful voice.

Lúthien thinks of those dreadful days after Beren died, and her heart twists again with pity.

"I did not know, either," Maglor says. "You would think – you would think I would have known, if anyone had."

"I am sorry," Lúthien breathes. "I am so, so sorry."

Maglor manages the faintest of smiles for her, but says nothing else.

They sit in silence for a while.

Lúthien does not want to ask the question burning on her tongue, but ask it she must. "Have you any idea where he might have gone?"

"Do you think I would be here, if I did?" Maglor asks, wearily.

He and Fingon have spent hour upon hour pacing around Fingon's study, fruitlessly turning over the same half-questions: why and how and could we have— before returning, inevitably, to the most pressing of the lot: Where is he, where is he, where is he?

They do not know. They have no idea what Maedhros was thinking in the hours before he disappeared, which frightens them almost more than the rest of it.

Lúthien takes a breath. "Do you think – is there any chance – might he have gone to Doriath? My father still has the Silmaril he took from you."

Maglor barely flinches at the reminder of that past failure. "It's possible," he says. "What makes you think of it?"

"He spoke to me," says Lúthien, "just before I left. He asked me if I might not try to persuade my father to relinquish that Silmaril – for your sake."

"For my sake!" Maglor says. He laughs, bitterly. "For my sake! How very considerate of him. What did you answer him?"

Lúthien meets his gaze unhappily. "That I would not try," she says. "If I had only spoken differently..."

“If only, if only, if only,” Maglor says. “Do not blame yourself, Lúthien. Fingon and I have gone down that path too many times already – but the truth is that I do not think anything could have stopped Maedhros, once he had made up his mind.” He shrugs. “Or perhaps I did not know him as well as I thought.”

“You speak of him as though he is dead,” Lúthien breathes.

“He could be,” Maglor says, matter-of-factly.

“You are very angry,” Lúthien murmurs, “are you not?”

Maglor is quiet for a moment. “This is the third time Maedhros has left me to go after a Silmaril,” he says. “In Mithrim, when Morgoth made his false offer of parley. In Menegroth, when he went hunting for Carcharoth. And now this! Yes – yes, I am very angry. It is the Oath – were it not for the damned Oath—”

“I asked you once before,” Lúthien murmurs, “if you would un-swear it, if you could.”

Maglor looks at her with anguished eyes. “I would,” he says. “In an instant, if only I knew how – look what it has taken from me!”

His breath catches. Lúthien puts her arms around him again.

“Maedhros loves you,” she says quietly, after a moment. “He was – I do not think he was very well, when I spoke to him – but even so it was clear to me how well he loved you. You must not doubt that.”

Maglor thinks of Maedhros whispering, What would it take, to make you hate me? and his own low voice answering, If you left me.

How much easier it would be, he thinks sometimes, not to understand! How comforting bewilderment would feel, to say, I know not why he has done this – what a burden, to know Maedhros as he does, to know what drove him to leave and know that it is, at least in part, Maglor's own fault, that Maglor, utterly trusting, handed his brother the very weapon he turned against him.

Useless, all useless: for all that matters is where Maedhros is now, and he does not know that.

"If he did go to Doriath," he says, attempting to return to Lúthien's question, "he would not have been able to get through your mother's Girdle, anyway." He means to explain, He left the Silmaril with me, but his voice catches halfway through the sentence – he who has always claimed such mastery of words – and all that comes out is, "He left – me, he left me, he left me."

"Oh, Maglor!" Lúthien exclaims. She flings her arms around him again, and Maglor hides his face in her shoulder until he has recovered some of his composure.

(Important, these days, to be composed, to show Fingon's shocked and doubting court that the sons of Fëanor can yet be relied upon – and Maglor's world might have fallen to pieces around him, but he is still good at performing.)

“You must not lose hope,” Lúthien says. She squeezes his hand. "He lives yet, does he not?"

"We cannot tell," Maglor says dully. "He has closed his mind – to me and Fingon both."

It is an awful, suffocating thing, to reach instinctively for the part of his heart that belongs to Maedhros and come up every time against nothing but a smooth impenetrable wall – to cry out, again and again, Where are you? Come back to me, and receive only endless uncaring silence in response.

"I am sure he lives," Lúthien says resolutely, "and you will see him again."

"I have thought him dead once before," says Maglor, "for thirty years, I thought him dead. He was not – and yet—"

Fingon, his voice flat and strange, said once, Makalaurë, is there any chance – he could have – there is a Silmaril in Angband still—

Don't say that, Maglor cried, quicker than thought, don't say that, Finno!

Neither of them have mentioned the possibility since; and so it has lingered, as unspoken things tend to, lurking just beneath the surface of every frantic circular conversation.

"It was not a happy homecoming," he says, "when he was returned to me."

"But he was returned!" Lúthien says. "And he will be again – I am certain of it."

Maglor says, his voice very dreamy, "Celegorm used to shout at me, in those years Maedhros was lost. He said I was a coward, for not attempting a rescue." He shrugs. "He was not wrong – and perhaps little has changed. Am I – am I always to be left behind, waiting for him to return to me?"

"You do not have to be," Lúthien murmurs. She thinks of Hírilorn, and pacing helplessly between its great boughs while Beren lay suffering in Sauron's dungeons.

"Perhaps," Maglor says, "that is the way the story goes, after all – and there is nothing I can do about it. Perhaps unshackling the chains of doom are not as easy as you made it appear, for us."

Lúthien looks at him. "I do not think you really believe that," she says softly.

Maglor meets her gaze, his eyes bright with despair. "I do not believe anything, any more," he says; and when Lúthien, her heart aching, presses a kiss to his cheek she tastes salt.

Meanwhile in the Halls of Mandos:

Withdrawn into the depths of the Halls, where he can nurse this new hurt in peace, Finrod is surprised to sense another approaching him.

For a moment he thinks Celegorm has come to apologise for his harsh speech; but the resemblance between the two spirits is merely superficial.

"You are hard to find, cousin," says Amrod. "I began to think you had taken Mandos up on his offer, and returned to life after all."

Finrod laughs hollowly. "I swore to remain here," he says, "and so I shall – until the breaking of the world, should your brother have his way."

"Is forever always forever?" Amrod asks, dreamily. "Queen Míriel once swore that she would never leave these halls; but she had taken up her body again by the time I arrived here."

"The line of Míriel," says Finrod, "is rather more prone to faithlessness than I."

He regrets the words as soon as he speaks them; barbed, unkind things, more suited to Celegorm than himself.

But Amrod looks at him with pity. "Don't let him make you cruel, Ingoldo," he says. "He did not win when he forced you from your kingdom – nor when he threw all your mercy in your face – but he will, if you grow to imitate him."

Finrod makes an effort to follow this advice. "I would have thought you would be on his side," he says.

"I am," says Amrod. "Why else do you think I want you to save him?"

"I am not sure that is possible, anymore," Finrod says bitterly.

"Neither am I," says Amrod, with a shrug, "but you did swear to try."

Finrod hesitates.

Amrod's story has always horrified him. How bitter a monument to the folly of the sons of Fëanor – how incriminating, that they did not realise after their brother's death that their Oath was pointless, their project Doomed before it could begin!

But Amrod was not just a morality tale: he was Finrod's little cousin, too.

And they have both suffered at Fëanorian hands.

"Why did you stay on the ship?" he asks. "Did you think the Valar would show you mercy, if you returned to these shores?"

"No," Amrod says neutrally. He offers Finrod the edge of a smile. "Only that I had to try."

"I didn't," Finrod says quietly. "I could have turned back with my father, after Alqualondë. I think it would have been better if I had."

"Beren would have died, then," says Amrod, "in the darkness in Tol-in-Gaurhoth. To say nothing of what other good you wrought in Middle-earth."

Finrod thinks of Lúthien, who thanked him for his sacrifice.

"To evil end shall all things turn that they begin well," Amrod muses. "I knew what I was facing, when I decided not to set foot on the beach at Losgar! Not – not that my father was already so consumed by madness – but I did not expect any mercy from the Valar, no." He laughs slightly. "And now here I am. Tyelko tells me it was all for nothing."

"He might not be the best judge of that," says Finrod.

"The brother I remember was kinder than this," Amrod says, thoughtful. He worries at his fingernails as he talks. Sometimes the light, such as it is, shifts and his form becomes that of a charred corpse, his skin crumbling away to reveal the blackened bones beneath. "Was it the Oath that made him so, do you think?"

"The Oath was his own folly," says Finrod. "You do not need to delve so deeply for his motivations: he told me himself that he cast me out of my kingdom because he wanted to, and he does not regret any of it."

“Yes,” Amrod says with a sigh, “it was our own folly, was it not? I was afraid of it, in truth. Afraid of what it might make me become – what it had already made me become, in Alqualondë. And poor Tyelko has gone much further down that dark and lonely path.”

“He killed you,” says Finrod, “and yet you pity him.”

“He killed you, too,” says Amrod, “or as good as – and you pity him too, I think.”

“I do,” Finrod admits. "But he will not accept any pity from me."

Amrod looks at him carefully, and then says, "You ask me why I was willing to turn away from my Oath. Why are you not willing to turn from yours?"

Finrod bristles. "What?"

"You didn't have to go with Beren," says Amrod. "And you didn't have to vow not to leave Mandos until Tyelko can. What made you do it, then? Is it naught but pride – let them add more verses to their songs about Finrod the Faithful, so pure of heart that he forgave his own usurper?"

"No!" Finrod says. "No."

"A hard thing," says Amrod, "to pity someone who does not want or deserve it."

"Quite," Finrod murmurs. "Perhaps that is why I pity him."

"It is a difficult task you have chosen," Amrod warns, "and a thankless one, with little hope of success: even I his brother can tell you that."

"So was the path you chose, when you stayed aboard the ship," says Finrod. "All the same – I have to try. For my sake, perhaps, as much as his." He looks at his cousin again. Amrod's spirit is a pale, flickering thing. "And yours."

"Mine?" says Amrod, sounding truly surprised for the first time.

"It matters, does it not?" Finrod says softly. "That you grieved your deeds – that you were willing to turn back, and face the consequences for them."

"It didn't do anything," says Amrod. "It didn't save anyone."

O for the solidity of a body! Finrod would clasp that small unhappy form to his own, if he could, and squeeze his shoulder comfortingly.

"Then let me save you," he says instead.

Amrod's smile is sad. "I don't think it's that easy," he says.

Back in Barad Eithel:

Before she leaves, Lúthien seeks out the High King.

Fingon is expecting to find one of his lords at the study door, ready to harry him some more about his terrible life choices; so seeing Lúthien is something of a relief.

Even so, he is very tired.

"Is there something I might help you with, lady?" he asks.

"I rather thought I might help you," says Lúthien, tilting her head and offering him a winning smile as she sits down. "But first I owe you my thanks."

Fingon thinks, absurdly, of his abortive promise to behead Curufin. "For what?"

"We have never really spoken, you and I," Lúthien says slowly. "And yet we have rather a lot in common, I think." She smiles at him again. "It was the story of Thangorodrim I was thinking of, when I saved Beren in Tol-in-Gaurhoth."

"I am glad some good came of it, then," Fingon answers bitterly.

Lúthien's eyes on him are sad. "I thought you might say that."

Fingon forces a smile. "Do not mistake me!" he says. "I was pleased indeed to hear how you saved Beren: and pleased, too, that you avenged Finrod my cousin in doing so."

He breaks off. Lúthien's face has filled with sudden pain, hearing Finrod's name.

"I mourn him, too," she says simply, noticing the question in his eyes. "I wish I could have saved him."

At some point you will have to learn that you cannot save everyone, Maglor told Fingon, during the fall of Himring.

Afterwards Fingon thought it mere Fëanorian dramatics; Maedhros had survived the battle, and against all odds so had Maglor, and even Curufin's head was still attached, after all.

Now he thinks perhaps there was a grain of truth to his cousin's words.

Maedhros' distant half-smile and his wide bright eyes and the little tremble in his mouth when Fingon kissed him that last evening—

How did Fingon not see it? How could he have been so blind?

"It is all very well," he says wearily, "to go into the dark armed only with a song, and free one you love from his chains."

Lúthien shudders. She can smell the blood – can feel it, warm and sticky, lapping about her ankles.

"But what can I do," Fingon continues, "if he goes back to the shackles? Am I to break them anyway, against his will?"

"Do you think he has?" Lúthien asks. "Do you think he went to Angband?"

"I don't know!" Fingon exclaims. "How can I not know? I have told myself – I have told him that we are as good as wed – but it is not true! I don't know where he is. How am I to find him, if I don't know where he is – if he has hidden himself from me, deliberately?"

"You can," says Lúthien. "You will. You found him on Thangorodrim, after all. Oh, you of all people must not lose hope!"

"No," Fingon says hollowly. "A High King must not be allowed to despair, after all."

Easier, these days, to understand what drove his father to the breaking point.

"Believe me," says Lúthien, "I know what it is to give your heart to one set on his own destruction." She offers him a faint, comradely sort of smile, but Fingon cannot bring himself to return it. "But is not love about following whether you are wanted or not – about saving them, as many times as it takes?"

Fingon looks at her carefully. Maglor speaks highly of Lúthien, and so did Finrod, but Fingon thinks he would take a liking to her even were it not so: beneath all her ethereal loveliness it seems to him there is a spirit rather akin to his own, both cheerful and practical.

"You do not understand," he says, and closes his eyes.

How is it that this dull defeated voice is his own? Look what you have done to me, he might tell Maedhros; look what you made of me. But the truth is that he left bruises on Maedhros too, with his grasping, over-eager fingers.

"It is not," he says, "it is not merely that I do not know where to follow him this time. It is that – how can I even know whether he wishes me to find him? How do you save someone who does not want to be saved?"

Lúthien thinks of Beren, who heard her singing outside Sauron's tower, and lifted his own voice in response.

She thinks of Maglor telling her that perhaps he need not be bound forever.

"I don't know," she admits.

Fingon tries to master himself. Lúthien may be trustworthy, but all the same he cannot afford to grieve too openly these days.

Is this Maedhros' vengeance on him, to make Fingon's proud and foolish declaration of love into a public stain – to have branded on his cheek, The High King is bound to a traitor?

(There are very few people in Barad Eithel who view Maedhros' disappearance without suspicion.)

"Your story is a happy one, and I am glad of it," he tells Lúthien. "But in truth I know not if its like will be told again – and not of the Noldor, certainly."

Lúthien looks at him unhappily. "Yours is not over yet, either," she says. "Maedhros told me once that I had brought hope to all Elvenkind with my deeds. But you did that long before I."

Fingon smiles at her, practised and kingly, without meeting her gaze.

(to be continued)

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally! I can show you a picture that I drew about six months ago for the Antagonist GameBook. And I still kinda like it..

#Orsino#Hail First Enchanter!#Yeah but no chantries he blew up#alas#and i firmly believe no harvester happened#it was all varic protecting him

873 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt: “Introduction”, Gold Does Not Always Glitter: Analyzing Friction Among the Noldorin Feanorians, written by Elrond Peredhel (T.A. 120)

‘To be a follower of Feanor’s sons was, by the time of the Second Kinslaying of Doriath, to be, to a certain extent, a conscious devotee of blood-stained murderers.’

So said Pengolodh in his widely-circulated account of the tragic, unnecessary attack by the sons of Feanor on the great kingdom of Doriath, held by King Dior Eluchil. While Pengolodh’s historical record has received a thousand years of fame for many valid reasons, not least of which is his meticulous attention to detail and his reliance upon first-person accounts and interviews which formed the basis of his research, it is nevertheless my intention to prove these words misguided if not utterly incorrect.

The first part of this book will analyze the lives of soldiers, merchants, and artists, all of whom claimed to be devoutly loyal to the sons of Feanor and believed that their service was important and purposeful, but did not necessarily hold uncomplicated and blind loyalty toward their lords. Some of these followers now dwell as refugees in the Homely House in Imladris, and following in Pengolodh’s footsteps I have included extra information for further context, including interviews, first-person accounts, and such small details as these individuals permitted.

I have chosen to focus much of the second half of my record on the lives of Feanor’s eldest sons, Maedhros and Maglor—not out of any sense of personal feeling, it must be made clear, but for the simple fact that, having some first-hand knowledge of the individuals involved, I hope to bring new information to this analysis regarding Noldorin customs, their worldview toward language and creation, and their potential motivations.

I am aware that my unique understanding regarding certain aspects of my subject matter will send my critics rushing to their history books and flinging accusations of personal bias. To these I can offer no satisfying refute, as the knowledge of my upbringing is widely known. This book, I must remind the more opinionated reader, is not an attempt at explaining or examining the psychology or cosmology which drove the sons of Feanor to commit any of the actions for which they have gained such infamy, but the discussion shall inevitably arise in brief. I hope that this book instead adequately does justice to my intention, which is to present an account of the daily lives of the sons of Feanor and their followers in order to deepen our understanding of the diverse, often internally divisive, always creative lives of the Feanorian faction of Noldorin elves.

#Elrond#I absolutely love this writing!#and now there is more!#i am so happy!#Elrond as my favorite academic

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Every time Sean Astin makes a statement on whether or not Sam and Frodo were indeed gay for each other in lord of the rings he’s always like “well we have to acknowledge that attitudes around sexuality have changed dramatically over the past several decades and since authorial intent is only up to speculation, the story is open to multiple readings, some of which might have different significances for different groups of people also they kiss on the lips because I said so”

72K notes

·

View notes

Text

=•☀️ ️Solicitude and Solace ☀•️=

Can't believe my meant-to-be-stress-relief-doodles somewhat turned to 2-month-stress-mixed-art-projects are finally complete!

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

My daily dose of serotonin.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

have to say Fëanor did hit the mark with “through sorrow to find joy, or freedom at the least” like yeah man I’d live by that!

325 notes

·

View notes

Text

hide and seek

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm so gullible i see literally any redhead covered in blood and i'm immediately like 👀 Maedhros? 👀👀 my king Maedhros? my love Maedhros?? and i'm only right like. 70% of the time. what do you mean there's other bloodsoaked redheads who allowed this

301 notes

·

View notes

Text

A long awaited return to Valinor

364 notes

·

View notes

Text

Y'all are amazing. Reblog to hug the person you’re reblogging from.

86K notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 1: childhood

187 notes

·

View notes