Photo

9 Thermidor

Today is the anniversary of the Thermidorian Reaction, which caused the fall of Robespierre, Couthon, Saint-Just, Le Bas, Augustin Robespierre and many of their friends & supporters. In memory of this day, here is a list of posts & sources referring to Thermidor.

Thermidor Project

The Thermidorians: Paul Barras

The Thermidorian Reaction (Françoise Brunel)

Robespierre’s speech of 1 Thermidor

Barère’s speech of 2 Thermidor

Augustin’s speech of 3 Thermidor

Session of the Jacobin Club on 3 Thermidor

Élisabeth & Philippe Le Bas (~4 Thermidor)

Joint session of the Committees (5 Thermidor)

Couthon’s Speech of 6 Thermidor

Barère’s report of 7 Thermidor

Robespierre & Barras (7 Thermidor)

Robespierre’s speech of 8 Thermidor

Aftermath of Robespierre’s speech of 8 Thermidor, Year II

Robespierre: Death is the beginning of immortality.

9 Thermidor (Françoise Brunel)

Robespierre’s Policies and the 9 Thermidor (Albert Mathiez)

Session of 9 Thermidor

Robespierre in the Convention, 9 Thermidor

The 9 Thermidor (Jean Jaurès)

The Hôtel de Ville, Night of 9th Thermidor

Bulletin des Lois (#29): 9 Thermidor, Year II

Robespierre’s books on 9 Thermidor

Hanriot’s letter to the adjutant general of the 6th legion (9 Thermidor)

Proclamation of the National Convention (9 Thermidor)

Proclamation of the Commune to the French People (9 Thermidor)

Procès-verbal of the session held by the General Council of the Commune (9 / 10 Thermidor)

Letter from M. Robespierre, A. Robespierre & Saint-Just to Couthon

La réaction thermidorienne (Albert Mathiez)

Thermidor: Another Point of View

The famous letter to the Section des Piques

Table on which the injured Robespierre lay

Robespierre’s Fall (Ralph Korngold)

Augustin Robespierre’s last moments

Execution of Robespierre and his accomplices

Records & primary sources on Robespierre’s execution

Thermidor: In memory of the citizens who have died or were executed during the Thermidorian Reaction

Thermidor & revolutionary violence

Report of the Committees of Public Safety & General Security on the “conspiracy of Robespierre etc.” (10 Thermidor, Year II)

Le dix thermidor ou la mort de Robespierre

Fell free to add links of your own, citizens!

448 notes

·

View notes

Note

what is danton

A mythical creature! Rumour has it, if you turn of the lights and whisper ‘Robespierre was the hero of the French revolution’ three times into a mirror he’ll appear out of nowhere and fight you

253 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy 259th Birthday, Maximilien Robespierre!

[S]o long as the French Revolution is regarded, not as the “suicide of the eighteenth century” but as the birth of ideas that enlightened the nineteenth, and of hopes that still inspire our own age; and so long as its leaders are sanely judged, with due allowance for the terrible difficulties of their task; so long will Robespierre, who lived and died for the Revolution, remain one of the great figures of history.

Robespierre and the French Revolution (J. M. Thompson)

Check out my Robespierre tag to find out more about him!

182 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Thermidorians: Paul Barras

The Thermidorian Reaction is one of the most complex and controversial events of the French Revolution ; accordingly, its primary actors & initiators (commonly known as “Thermidorians”), coming from diverse social and political backgrounds, often had very different reasons & motives for participating in the events of Thermidor.

In order to elucidate the history of Thermidor, I intend to focus on prominent Thermidorians in the course of this research project, examining their political & ideological background, as well as their respective reasons for taking part in the Thermidorian Reaction.

In traditional historiography, Barras has commonly been portrayed as a staunch opponent of Robespierre ; according to this narrative, Barras, having been recalled from his mission with Fréron by Robespierre due to violent excesses in terms of repression, feared for his life and took part in the Thermidorian conspiracy in order to save himself. This account, however, particularly prominent in the historiography of the 19th century, has been called into question in more recent studies. [1]

First of all, clarifications concerning Barras’ mission to Toulon and Marseille are necessary. Contrary to what is commonly said, Barras and Fréron were not recalled because their measures were considered excessively violent or brutal by their colleagues in Paris ; rather, they were reproached primarily for their failure to cooperate with the revolutionary institutions of Marseille (Barras went as far as to have Maillet, the president of the Revolutionary Tribunal of Marseille, arrested ; Maillet, however, was ultimately acquitted by the Paris Tribunal), as well as for the débaptisation of Marseille (provisionally named “Sans-Nom”, in accordance with the order of 17 Nivôse Year II). [2] The latter measure, incidentally, caused particular outrage, as the city’s name was considered symbolic due to its connection to La Marseillaise and due to the role of the Marseillais fédérés in the events of 10 August 1792. [3] It is also important to remember that it was not Robespierre who recalled Barras and Fréron to Paris, but Billaud-Varenne, who signed the order of the Committee of Public Safety on 4 Pluviôse Year II along with Collot d’Herbois ; in said letter, Billaud and Collot openly challenge the representatives’ decision to change the name of Marseille:

You have believed that Marseille had to change its name. And here, citizens colleagues, the Committee of Public Safety stops (s’arrête).

The name Marseille recalls immortal memories to the mind of free men ; criminals, under the mask of republicanism, have outraged it ; but the monsters who sought to ruin it have ceased to be Marseillais.

Has one not been forced, in order to lead it to federalism or monarchy, to incessantly present the sacred words of the Republic One and Indivisible to it?

Could history, when writing our annals, not let a name escape which marches into posterity alongside the fall of kings? [4]

Returning to Paris in early March 1794, Barras and Fréron found themselves rather isolated and disoriented after having been absent for over a year. “Ce qui se passe ici est de l’hébreu pour nous”, Fréron is reported to have said [5] ; Barras, in turn, was met with distrust and hostility by the Committee of Public Safety. While his hostility towards several members of the CSP (such as Carnot, Billaud-Varenne and Collot d’Herbois) is well-known, there is no sign of Barras being opposed to Robespierre in particular, as post-Thermidorian historiography seeks to affirm ; on the contrary, there is circumstantial evidence suggesting a relationship of mutual respect between the two men. (On a side note, one could speculate if and how the confrontations between Barras and Augustin Robespierre on their mission to the Army of Italy impacted Barras’ relationship with Maximilien, although there is little historical data on this to begin with.) [6] Barras, in a handwritten note, mentions the following encounter with Robespierre:

Robespierre accosted me on the [day after Carnot had vainly tried to send Barras on a mission to the armies], and said to me, “You feel the necessity of remaining in the Convention ; it is time the Convention should take measures to free itself from the factious majority of the committees.” My reply was embodied in these few words: “Well, then, ascend the tribune, and disclose to the Convention its usurpation of power and the bloody measures it daily takes against good citizens.” Robespierre answered, “It might, perhaps, be dangerous to make these things public, but the time is not far off when it can be done.” [7]

While there is no historical evidence for the authenticity of this story, its atmosphere does certainly not seem to indicate hostility and suspicion. (It has to be considered that such passages only appear greatly altered in the Mémoires de Barras, as these have not been written by Barras himself, but by his friend and secretary Rousselin de Saint-Albin ; Rousselin, a former friend of Danton, took liberties when writing the memoirs based on notes and manuscripts of Barras, often misrepresenting the latter’s thoughts and attitudes on important issues, such as his relations to Robespierre). [8] Furthermore, in a later passage of this note, Barras describes Robespierre’s efforts of moderation in a quite sympathetic manner:

[L]astly, the committees […] decided upon making common cause with the Thermidorians […] and casting on Robespierre the odium of all the crimes committed by them. Robespierre was not an ordinary man. Swept away by the torrent of the Revolution, he had allowed himself to have recourse to extreme measures. He had become convinced that the system of terror and death carried out to the highest degree of bloody barbarity was devouring all men truly Republican ; he sought to put an end to these atrocious executions ; he opposed the arrest of several deputies, of a number of respectable citizens, paid homage to divinity, talked clemency, and ended by perishing […] through this very return to the principles of justice. [9]

These words, of course, were only written in hindsight long after Thermidor, and the experience of the Consulate and Empire may have altered Barras’ perception of Robespierre. Nonetheless, it can be concluded that the image of Barras being a staunch opponent of Robespierre is but a myth.

Based on this, and considering the relative political isolation of Barras after his return, it can be assumed that he was not involved in the preparation of the Thermidorian conspiracy (contrary to the traditional narrative of 19th century historiography, wherein he is depicted as one of its initiators). Indeed, by all accounts, it seems that, like the majority of the deputies, he was genuinely surprised by the Thermidorian Reaction. This would also explain his apparent hesitation in the face of the events: not once did he intervene during the stormy session of 9 Thermidor, and it was only reluctantly (according to his own account) that he accepted his appointment to commander of the Convention’s forces during the evening session. [10] His nomination was not based on political considerations, but rather due to technical reasons: the Convention was in need of a strategist to command the National Guard ; Barras, being a former officer and possessing considerable military experience due to his missions to the army, fulfilled these requirements perfectly. [11] (Incidentally, according to Courtois, it was Fréron who nominated Barras for this position.) [12]

Barras’ role in the military operation was considerable, albeit purely organisational: it was Léonard Bourdon who led the troops storming the Hôtel de Ville, whereas Barras only arrived on the scene afterwards. Yet, his contribution is not to be underestimated: intending to avoid direct combat, he suggested outlawing Robespierre and his allies in order to weaken their defence ; this caused a significant number of soldiers to defect from the Commune’s troops, which was a considerable factor in the victory of the Thermidorians. [13] Accordingly, Barras was afterwards celebrated as the “saviour of the Convention” ; he seized this opportunity and ultimately managed to secure himself an influential position in the new regime. [14]

In conclusion, while Barras certainly played a considerable role in the events of Thermidor and particularly in their aftermath, his motives were by no means comparable to the ones of leading Thermidorians such as Fouché. Barras was not, contrary to what is commonly said, a staunch adversary of Robespierre ; nor was he involved, in all probability, in the preparation of the Thermidorian conspiracy. Therefore, his status as a “Thermidorian” (in the classical sense) has to be reconsidered and reexamined critically.

What do you think, citizens? Feel free to add your thoughts.

Further reading

P. BARRAS: Memoirs of Barras, t. 1.

H. MONTEAGLE: Barras au Neuf thermidor, in: Annales historiques de la Révolution française, n° 229, p. 377-384.

J.-R. SURATTEAU: BARRAS Jean Nicolas François de Barras-Clumanc, in: ALBERT SOBOUL: Dictionnaire historique de la Révolution française, p. 80-83.

Keep reading

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Revolutionary fan

Depicting Robespierre in a scene from the Festival of the Supreme Being (middle), as well as Lepeletier (left) and Marat (right).

Keep reading

108 notes

·

View notes

Photo

RBZPR: 600 Followers Celebration

Hello, citizens! I am glad to announce that I have reached 600 followers, and I want to take this opportunity to thank all of you for following me!

First of all, to mark the occasion, I would like to ask you, citizens, for some feedback, so please let me know what you think about this blog, what you like / do not like about it, what could be improved, or what projects you would like to see in the future! Feel free to reblog or comment this post, or send me a message here.

Furthermore, I am planning a small give-away! The prize will be Slavoj Žižek’s “Robespierre: Virtue and Terror”.

On 6 May (which is Robespierre’s birthday), the winner will be determined at random among those of my followers who have reblogged this post. Thus, if you want to participate, you have to be following me and to reblog this post before 6 May 2017. I will announce the winner soon after.

Have a nice day, citizens, and again, thank you!

If you are interested, check out these links to find out more:

RBZPR: Introduction

My Works & Projects

Couthon: History Project

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

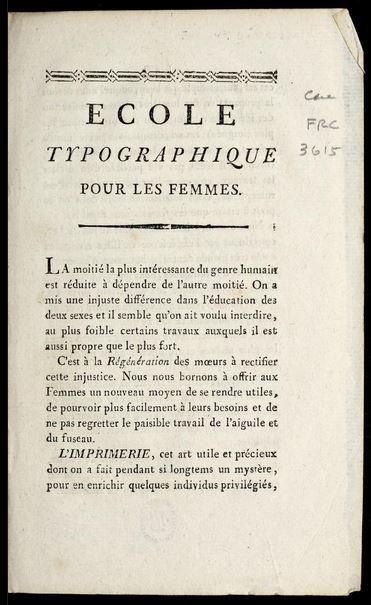

This pamphlet, published sometime around 1790 near the beginning of the French Revolution, advertises a printing apprenticeship exclusively for women. The anonymous writer notes that “the more interesting half of the human race has been reduced to depending on the other half” and asserts that offering women an opportunity to engage in useful work would “rectify this injustice.” Many women–widows of master printers, in particular–ran print shops before and during the Revolution. One example is Anne Félicité Colombe, proprietor of the Henri IV print shop in Paris and member of the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women, who published Jean-Paul Marat’s radical periodical L’Ami du peuple [The Friend of the People].

Read this pamphlet in its entirety and thousands of others in our free collection of French Revolutionary pamphlets on Internet Archive.

129 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Danton and the terminology of the « terror » (Annie Jourdan)

If, in historiography, Danton does not embody the Terror, he nevertheless pronounced the term and its derivations. There is nothing original about this. From the beginnings of the Revolution onwards, the contemporaries were particularly fond of this word in order to describe the fear that was felt and the reply or reaction which imposed itself. And this not only applied to France. In London, for example, it was the government which threw « a great terror among all friends of the French nation ». In Paris, the Girondin Lasource complained that the inaction of the French armies in May 1792 was such that « one will [never] inspire terror to our enemies ». Browsing the pages of the Moniteur universel, one will discover the diverse usages that were in vogue at the time. Divine terror, judiciary terror, military terror or the terror that is proper to despotism. Gustav III, the king of Sweden, assassinated in March 1792, thus only owed his successes to the terror which he inspired. His brutal death, however, proved that « the terror is not the safeguard of the princes ». The petition of 17 June 1792, presented by the section of Croix-Rouge, demonstrates well that « terrorist » speech could be diverted and harnessed by another cause, as it proposed to « transfer the terror into the soul of the conspirators ». What is particularly new here – as in Danton’s speeches – is that it is not God, the prince or the judge would inspire terror, but the people – through its sections, its legions or its representatives. This usage would become popular in the course of the Revolution and produce the expression « the terror is the order of the day ». Being a « magic » formula in a way, conceived in August 1793 in order to appease the popular sections, it would be used by various revolutionaries en mission or by some deputies at the tribune of the Assembly, in order to designate the inflexible policy that was established from this date onwards, while it was never officially proclaimed by the Convention. On 5 September 1793, in fact, it was not the terror that was decreed, but the creation of a revolutionary army. It was it, and it alone, that would carry the terror into the insurrectionary departments. This is also what results from Bar��re’s speech, while the decree of the same day did not refer to said terror at all, when it ordered that « the revolutionary army will execute, everywhere where it will be needed, the revolutionary laws and the measures of public safety ». Concentrating on this formula too much can thus lead to an error. This does not mean that synonymous or derivative terms have not been frequently invoked in order to invite to action, to designate the measures that were taken or to be taken, to sanction committed acts and to frighten the enemies. One will see that it is justly in the mouth of Danton that these are most recurrent. The rule of conduct of the Convention wanted to be very different, as the decree of 2 Germinal Year II (22 March 1794) demonstrates, which proclaims that justice and probity are the order of the day. And this is understandable. The dignity of France and the legitimacy of the Revolution was at stake. Fighting against the counter-revolution could not be done to the cost of either of them.

Terroriste avant‑la‑lettre ou terroriste à temps partiel ? (Annie Jourdan), in Danton: le mythe et l’Histoire (Michel Biard & Hervé Leuwers)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

March 18, 1965 — The first spacewalk in history performed by cosmonaut Alexey Leonov

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

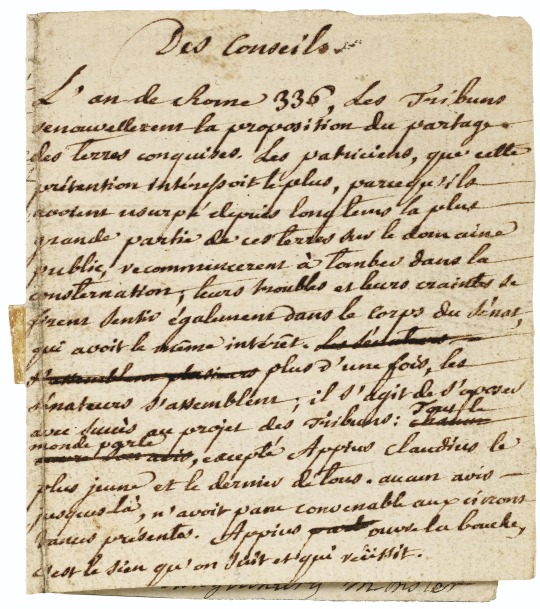

On councils (Maximilien Robespierre)

In the year of Rome 336, the tribunes renewed the proposal of sharing the conquered lands. The patricians, whom this aim affected the most, because they had usurped the greatest part of these lands on the public domain for a long time, started to fall into consternation again ; their troubles and their fears also caused this to be felt in the body of the senate, which had the same interest. […] more than once, the senators assembled ; it was a matter of successfully opposing the project of the tribunes : everybody spoke, except for Appius Claudius the youngest and the last of all. Up to this point, no opinion had appeared suitable to the present circumstances. Appius opened his mouth, it is his which one followed and which succeeded.

The incident reported by Robespierre on this small piece of paper concerns the agrarian law voted by the tribunes of the plebs, against which the patricians and the Senate fought “because they had usurped the greatest part of these lands on the public domain for a long time”. But more than the redistribution of land, a popular demand which had to be reflected on from the beginnings of the Revolution onwards, what seems to fascinate Robespierre the most in this point of history had to do with the personality of the consul Appius Claudius, who succeeded in reversing the vote in favour of the Senate : “it was a matter of successfully opposing the project of the tribunes : everybody spoke, except for Appius Claudius the youngest and the last of all. Up to this point, no opinion had appeared suitable to the present circumstances. Appius opened his mouth, it is his which one followed and which succeeded.” One cannot help bringing this ambitious and skilful Roman figure closer to the one of Robespierre, whose modest, quiet appearance, whose patient poise and whose timely interventions during the debates of the Convention were unanimously reported in the memoirs of numerous deputies. […]

Keep reading

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

La Maison de Robespierre

Some time ago, I shared the petition of the ARBR for the creation of a Robespierre museum in the Maison Robespierre in Arras, where Robespierre lived with his sister Charlotte and his brother Augustin from 1787 to 1789 ; said petition, launched in 2012, has gathered more than 6,000 signatures from 49 different countries.

During the Conseil Municipal of 12 December 2016, the mayor of Arras has tasked Gérard Barbier, president of the Université pour Tous, with establishing, presiding over and leading a scientific committee that is charged with defining the historical, historiographical and museographic project of the Maison Robespierre.

This scientific committee held a press conference on 9 February 2017 ; its members are Gérard Barbier, Martine Aubry, Catherine Dherent, Charles Giry-Deloison, Jean-Pierre Jessenne, Hervé Leuwers, Guillaume Mazeau, Alain Nolibos and Bernard Seneca.

The committee will deliver a first report on 6 May 2017 at the Hôtel de Ville of Arras. In case you are interested in learning more about this project, you can read the press statement of the ARBR, as well as the article by La Voix du Nord.

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The « Girondins » : Moderates?

In modern historiography, the Girondins are often referred to as “the last moderates of the Revolution” or in similar terms, whereas the Montagnards are regarded as authoritarian radicals ; in general, the juxtaposition of the “moderate” Gironde and the “radical” Montagne seems to have become a commonplace in the historiography of the French Revolution, although recent works have put this view into question. The purpose of this article is to examine the terminology of “moderate” & “radical”, and to determine whether it is appropriate to describe the policies of the Girondins as “moderate”.

Before going into detail, it is of course necessary to clarify the terminology. First of all, when speaking of “the Gironde” or “the Girondins”, it has to be stressed that these terms and the meanings attached to them are historiographical constructions: the Girondins at no point constituted a party in the modern sense (hence the quotation marks in the title) ; rather, they were a loosely defined group that was centred around a few “key players”. The term “Girondins” itself has been popularised by the romanticists of the 19th century, whereas its use during the Revolution itself was quite marginal (rather, the contemporaries of the Revolution used words such as “Brissotins”, “Rolandins” or “Buzotins”). Nowadays, it is used as a kind of umbrella term to define a loosely connected group of around 150 persons, centred around political leaders such as Brissot, Monsieur and Madame Roland, Buzot, Pétion etc. ; although some of them had personal connections, they by no means acted as a political party or had a universally shared programme. [1]

Secondly, it is necessary to define the meaning of the terms “moderate” and “radical” in this context ; from the days of the Revolution to our days, these terms, too, have been subject to a fundamental semantic shift. Today, “radical” is used as a pejorative term to describe movements or attitudes that are considered to be exaggerated or excessively violent, whereas the term “moderate” evokes positive connotations of peacefulness, reasonability and temperateness (this perception, in turn, is based on a massive cultural bias, as I will elaborate later). During the Revolution, however, the situation was quite different: while the term “radical” was not very common in political discourse, the term “moderate” was widely used and was, at certain times, perceived negatively and even employed as an accusation (e.g. against Augustin Robespierre in the summer of 1794). [2] For the sake of simplicity within this article, I will define “moderateness” centred around three basic criteria: aversion to violence, opposition to centralisation of power and commitment to democracy.

On this basis, I will examine whether it is accurate to use the term “moderate” to describe the policies of the Gironde ; the analysis will be focused on three specific aspects: violence, power and democracy.

violence

Historiography often presents the Girondins as staunchly opposed to any kind of political violence, in contrast to the “terrorist” Montagnards ; yet, as soon as one examines the positions of prominent Girondins closer, this position becomes contradictory.

The most obvious example is the Girondist position on war, which is the ultimate exertion of violence. Already in late 1791 and early 1792, prominent Girondins were advocating a full-scale war against the rest of Europe, a “crusade of liberty” (cf. Brissot’s speech of 31 December 1791 at the Jacobins). Later, prominent Montagnards would join their cause (whereas few, such as Robespierre, remained opposed to the war), and while the Girondins were not the only forces calling for a war (the party of the Court, for instance, did so, too, albeit for very different reasons), the War had always been (and was always perceived as) the project of the Gironde. Correspondingly, once the war had had begun, military defeats played a great role in the decline of the Gironde’s popularity among the people. [3]

The case of the September Massacres (2-7 September 1792) is also interesting in this context. In classical historiography, the Girondins are regarded as moderates who, from the beginning, opposed the Massacres, while the Montagnards are viewed as the driving force behind the killings ; this view is largely based on later claims of prominent Girondins well after the events of 2-7 September 1792. Yet, if one considers the attitudes displayed by prominent Girondins during the September Massacres, this view soon becomes contradictory. I recently published a post focusing on the public writings and journals of prominent Girondins that were published between 2 and 7 September 1792 or in the immediate aftermath of the events, which can be found here. Some Girondins, such as Gorsas, Carra or Concordet, justified or actively encouraged the massacres ; others (e.g. Louvet, Brissot) mostly remained silent during the Massacres and would only come to criticise them later when accusing the Montagnards. The case of Roland is particularly interesting, as it is often misrepresented in historiography: his famous letter of 3 September was not a denunciation of the massacres, but of Marat and the Paris Commune. Roland in fact admitted the necessity of the massacres in said letter, while proposing to laisser un voile on the events (interestingly, he was reproached for this by Gorsas in his issue of 5 September). [4] Additionally, one has to consider that many prominent Girondins held public offices at the time of the Massacres, so the role & responsibility of prominent Girondins as ministers and public officials during the events is significant (according to Charlotte Robespierre’s mémoirs, her brother Maximilien even reproached Pétion, who was mayor at that time, for his inaction during the Massacres). [5] If one considers all of this, it becomes clear that many Girondins either tacitly accepted or openly justified the Massacres when they took place. It was only later, in their campaign against the Montagnards, that many of them, such as Louvet, would distance themselves from the Massacres and attempt to blame the Montagnards for the bloodshed. [6]

Another significant example is the role of violence in language ; while prominent Montagnards such as Marat (although the classification of Marat as a Montagnard is quite controversial, per se) or Saint-Just are often criticised for what is perceived to be an excessive use of violent rhetoric, such language is by no means exclusive to the Montagne. There are numerous examples (e.g. Guadet’s speech of 12 May 1793: “All the departments will send into oblivion this handful of traitors and anarchists, who are far more to be feared than the emigrant armies or the rebels of the Vendée.” [7] ), but the most obvious one is Isnard’s famous threat against Paris, which is the culmination of his continued diatribes against the capital. In his speech of 25 May 1793, he proclaimed that if an attack were made on any of the deputies, “Paris will be annihilated. Soon, men will walk the banks of the Seine and wonder if the city ever existed.” [8] When examining the revolutionary press of 1792-1793, one will soon find that violent rhetoric was as frequent among Girondins as it was among Montagnards.

If one considers all of these facts, it becomes evident that the depiction of the Gironde as moderate and strongly averse to violence is not tenable. Instead of opposing violence, the Girondins made use of it themselves when it served their purposes. Therefore, the first criterion of “moderateness” as defined above, aversion to violence, does not apply to the Girondins.

power

When speaking of power & centralisation, one often encounters the juxtaposition of the “federalist Girondins” and the “centralist Montagnards”. Especially in recent works, this view has increasingly been called into question, and it has become clear that the classical depiction of “Girondin federalism” does not stand up to scrutiny. As a specific analysis of this would exceed the scope of this article (and may be subject to examination in a future writing), I want to content myself with recommending Marcel Dorigny’s work on this, which you can find here.

What is essential is that the Girondins were by no means opposed to a centralised power, but merely to any kind of power that was not controlled by themselves ; they did not intend to establish a federal state or to “federalise” France, but to give another centre to it (hence the continued proposals for an assembly of deputies in Bourges). Buzot constitutes the exception to this, as he was the only one among the Girondin leaders who outlined a truly federal state ; yet he himself regretfully admits that this was by no means the motivation of his allies who opposed Paris. [9]

This also becomes clear when considering the role of the Gironde in the early legislative processes of centralisation. The Commission of Twelve, for example, was a project that was exclusive to the Gironde, and during its brief existence, it was solely dominated by Girondins. Having been created on 18 May under the pretext of an alleged conspiracy to destroy the Convention, the Commission targeted prominent “radicals” and members of the Commune, such as Hébert ; it was abolished on 27 May, just to be re-established on the following day. The Commission was ultimately suppressed in the course of the insurrection on 31 May 1793. [10] Apart from that, many prominent Girondins were also involved in the creation of the first Committee of Public Safety and the Revolutionary Tribunal. [11] It is also quite telling that the Girondins, while some of them originally had opposed the creation of a Revolutionary Tribunal, where among the first to make use of it and of the abolition of parliamentary immunity when indicting Marat and sending him before said Tribunal. [12]

In brief, one can conclude that the Gironde did not seek to split up power, but to overthrow the one of the Montagne and to assume control themselves. They were by no means opposed to centralising measures (as long as these were under their own control) and even supported them when it furthered their cause. Thus, the second criterion of “moderateness”, opposition to centralisation of power, also fails.

democracy

Finally, let us examine the Gironde’s position on democracy. While the Montagnards are often regarded as “populists” or “demagogues”, the Girondins are seen as the advocates of “true democracy” (as such, they were idealised by the social democrats and liberals of the 19th century), having come to represent the concept of “moderate republicanism”. Yet, this narrative does not hold up to scrutiny, as the Girondin attitude on the demos was often characterised by elitism and scorn for the lower classes.

Many Girondins, coming from a bourgeois background and being “men / women of order”, valued culture & labour and severely judged individuals who did not earn their living ; wanderers and bohemians, perceived as “idlers”, did not fit into their vision of an active and ordered society. [13] As this image of social hierarchy was very common among the Girondins, they preferred to ally themselves with the bourgeoisie of the province, viewing protests and riots as “complots” against social order (which does not mean, however, that the Girondins categorically opposed violent insurrections, as examined above ; when these riots served their purposes and/or were controlled by themselves, the Girondins were not hesitant to embrace them). The Girondins’ emphasis on social order is demonstrated, for instance, by the extent of the ceremonies that were held in memory of Simoneau in the spring of 1792. [14] Thus, one can often find a certain underlying current of elitism in Girondin writings, as many prominent Montagnards already perceived during the Revolution.

Furthermore, one has to consider the Gironde’s policy of economic liberalism in this context ; the Girondin social policy, as Mathiez puts it, comes down to “absolute freedom of trade, and to the use of bayonets in order to enforce this freedom”. [15] While the Montagnards were depicted as disorganisers and anarchists, many Girondins presented themselves as the defenders of property and order (cf. Brissot’s A tous les républicains de France, 29 October 1792). This led many Montagnards to judge the Girondins as agents of the rich and the “bourgeois”. Robespierre, for instance, in the first issue of his Lettres à ses commettants, accuses them of only wanting to “establish a Republic for themselves … and to govern only in the interest of the rich and of the public officials.” Madame Jullien, the wife of the Montagnard deputy Jullien de la Drôme, writing in a letter to her son on 24 October 1792, judges similarly: “The Brissotins want a republic for themselves and for the rich and the others want [it to be] entirely popular and entirely for the poor, and this, along with human passions, is what scandalously divides our senate.” [16]

Additionally, instead of frequenting popular societies, many prominent Girondins met in private homes or “salons” in order to discuss their policies ; the most prominent examples are the salons of Mme Roland or Valazé, but also the home of Mme Dodun, were Vergniaud received guests, or Clavière’s hôtel in Suresnes. This enforced the popular image of a “Girondin party”, and can be regarded as a proof for a certain elitism. [17]

Apart from that, many Montagnards have accused the Gironde of scorning the common people, particularly the people from the Parisian faubourgs. While this is certainly not an universal view among Girondins (Concordet, for example, seems to constitute a notable exception), historians such as Jacqueline Chaumié have concluded that many of them adhered to the classical distinction between “la plèbe” (the Parisian sans-culottes from the faubourgs) and “le peuple” (the merchants, artisans and peasants from the province). Based on this, many prominent Girondins dreaded popular manifestations, as they perceived the “mob” as irrational, incontrollable and vulgar. [18]

It has to be stressed that this mindset was neither exclusive to the Gironde, as many other contemporaries of the Revolution shared it, nor was it universally shared among Girondins. Nonetheless, this casts doubt on Gironde’s commitment to democracy, at least in the way it is depicted in classical historiography. It can be concluded, then, that the third and final criterion of moderateness, unwavering commitment to democracy, does not fully apply to the Gironde, either (at least not in the sense of our understanding of democracy).

conclusion

In summary, the policies of the Gironde do not correspond to our modern understanding of “moderateness” ; as demonstrated above, the dichotomy of the “violent, centralist and demagogic” Montagnards and the “non-violent, federalist and democratic” Girondins does not hold up to scrutiny. In general, I think that the perception of the Gironde as moderates in modern historiography is the result of a false dichotomy of “radicalism” and “moderateness”, which is in turn based on a simplistic conception of politics as a “spectrum”. To be brief: in my eyes, the Girondins were by no means “moderates” ; in their own way, they were as “radical” as the Montagnards. The struggle for hegemony in early 1793 was therefore not a conflict between “moderate” & “radical” forces, but simply between actors & “factions” (again, as elaborated above, not in the sense of modern “parties”) with fundamentally different policies.

Finally, as I mentioned earlier, I think that the perception of the Gironde as “moderate” and, generally, the dichotomy of “moderateness” and “radicalism”, as well as the negative connotation attached to the latter, are results of a massive cultural prejudice. This, in turn, is based on the central position that liberalism holds in our society and on the liberal theory of extremism. Liberalism is seen as democratic, non-violent and centred around “economic freedom”, while in reality, is has always entailed the prioritisation of market interests over individual freedom (and the use of violence against those who seemed to threaten the interests of capital), as well as a certain distrust towards the “popular masses” (often expressed in elitist / classist rhetoric) and "not-too-democratic republicanism” (as @valeria-lagrimas expressed it in a message to me ; thanks to her for the advice on this!), as opposed to more radically democratic models such as the Commune of 1871.

Furthermore, according to the liberal consensus, liberalism is the only position that is not “ideological” or “radical”. Consequently, the Girondins, whose policies are often in line with our modern conception of liberalism, are depicted positively, i.e. as “moderates”, whereas the Montagnards, for instance, are considered “radical” or “extremist”. This dichotomy can be found in the classical historiography of all major revolutions of the 18th and 19th century, and it is deeply embedded in our perception of history & politics. Nonetheless, as I attempted to demonstrate in this article, it has to be examined critically and re-evaluated, as it tends to distort history in order to make it fit into this narrative.

Further reading:

Federalism (Marcel Dorigny)

The Gironde (Marcel Dorigny)

Girondins et Montagnards (Albert Mathiez)

Actes du colloque Girondins et Montagnards (Albert Soboul)

The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution (Timothy Tackett)

Finally, I want to thank @montagnarde1793, @valeria-lagrimas and @revolution-avec-revolution for their generous help and advice!

What do you think, citizens? Feel free to add your thoughts!

Keep reading

211 notes

·

View notes

Link

I suspect this is of interest to some here…

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Oval medallion containing a lock of Maximilien Robespierre

From Charlotte Robespierre, with documents certifying its authenticity.

Source: Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris

150 notes

·

View notes

Photo

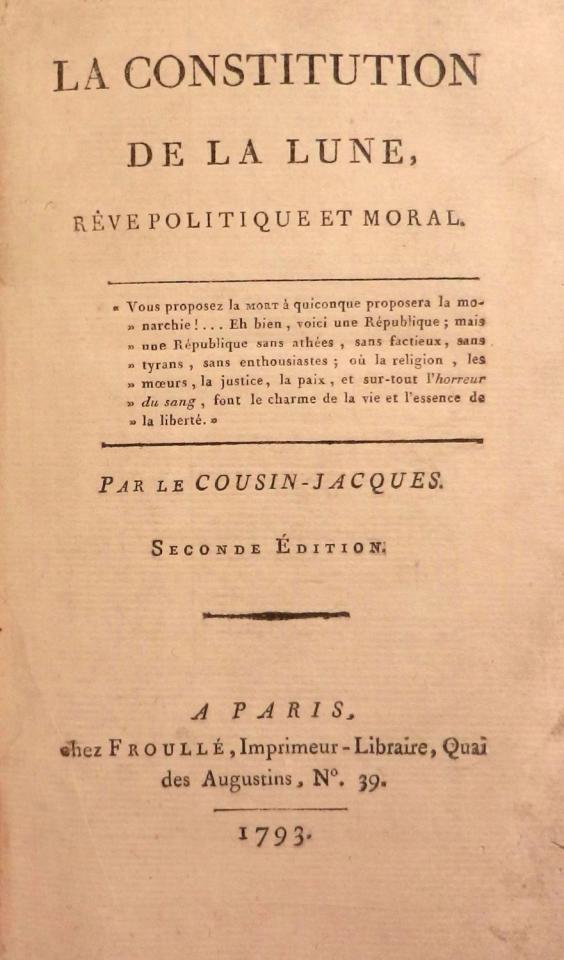

La Constitution de la Lune (Louis Abel Beffroy de Reigny)

Recently, when doing research on the Constitution of 1793, I stumbled upon this interesting work: La Constitution de la Lune, rêve politique et moral by Louis Abel Beffroy de Reigny, also known as “Le Cousin-Jacques”. The title made me curious, so I did some research on the work and its author.

Beffroy was a dramatist and writer during the French Revolution. He was born in Laon on 6 November 1757 and came to Paris in 1770 in order to attend the Collège Louis-le-Grand, where Robespierre, Fréron and Camille Desmoulins also studied. His pseudonym, “Cousin Jacques”, must have emerged at that time ; according to some sources, it was given to him by young women when gambling. After having served as a professor in several cities in the province, he married in 1780 and abandoned teaching in order to become a journalist, poet and dramatist. In 1783, he was imprisoned in the Bastille for having published Les Petites Maisons du Parnasse. [1]

Between 1785 and 1791, he released a monthly journal, alternately going by the names Les Lunes du Cousin Jacques, Le Courrier des planètes and Les Nouvelles Lunes du Cousin Jacques ; therein, he published satirical texts, songs, poems and sketches, but also more serious articles and writings. [2]

What is striking is the frequent invocation of metaphors from the field of astronomy in Beffroy’s work ; the “lunar allegory” allowed the author to place his observations on the political and social transformations of his time in a Utopian context. Personally, I also suspect that there is a play on words involved, as the term “revolution” was originally used to describe the revolving motion of celestial bodies.

Anyways, in 1787, Beffroy was welcomed at the Rosati, a literary society in Arras, to which Robespierre and Carnot also belonged. [3] As Barras recalls in his memoirs, Carnot was fond of Beffroy and would frequently defend him:

Carnot, who, although mathematics seems to be his vocation, is none the less more frequently a creature with an imaginative turn of mind, has his weak points in this respect; and, as weak points constitute passions it is difficult to explain, I will not say that it is impossible to conceive his passionate liking for one Beffroy, known among the masses by the name of “Cousin Jacques,” who believes that he has political ideas because he daily writes Les Constitutions de la lune. He is free to be as much as he chooses the publicist of another planet ; but like the priests, who are forever speaking of heaven and never troubling themselves about the earth, this fellow, while seeking to make us believe that he is in the moon, in order to draw our attention in that direction, is none the less engaged in subversive intrigues. [4]

Beffroy entered politics in October 1790, albeit with a polemic spirit. In November of the same year, he published his play Nicodème dans la lune, ou la Révolution pacifique, folie en prose et en 3 actes, mêlée d'ariettes et de vaudevilles, which would come to be his greatest success. In it, two villagers, Frérot and Lolotte, complain about the tyranny exercised by the lunar government, while an ethereal traveller, Nicodemus, arrives ; speaking with the Emperor of the Moon, he extols the benefits of the revolution which has taken place in the distant country of France. [5] In the following years, Beffroy continued to publish capricious comedies of this kind ; these, however, were torn apart by critics and quickly began to bore the public. [6]

In 1793, Beffroy published La Constitution de la Lune, rêve politique et moral, which was intended to be a “model” for France and a criticism of the political situation in 1793 ; again, Beffroy invokes the lunar metaphor in order to transfer his observation and proposals into a explicitly Utopian setting. In the “Observations” preceding this constitution, the author is quite frank about his motivations: he asserts belonging “to a single party, the one of moderation”. Presenting France as beset by anarchy and violence, Beffroy offers a précis historique of the Revolution of the Moon. The lunatiques (another play on words) nearly fell prey to demagogues. Yet, being “wiser” than the French, the citizens of the Moon managed to pass from Empire to Republic without much bloodshed ; the emperor had died out of sorrow. What followed was a draft for a Constitution of the Moon that was consciously Utopian ; nonetheless, it was a call for moderation and a criticism of the government’s policies. [7]

As a result of this publication, Beffroy was arrested on 26 November 1793. His brother, Louis-Étienne Beffroy de Beauvoir, who was a deputy at the Convention, intervened in his favour, whereupon he was released on 26 January 1794. The printer of Beffroy’s Constitution de la Lune, Jacques-François Froullé, however, did not escape a trial ; being reproached for having printed a work containing an “uncivic” account of the death of the king in April 1793, he was sentenced to death by the Revolutionary Tribunal and executed on 4 March 1794. [8]

While I am not particularly fond of the movement of “moderation” that emerged in the winter of 1793 / 1794, I found this work and its premise to be quite interesting, which is why I intend to translate parts of it.

What do you think, citizens?

Keep reading

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Danton and the Third Republic (Michel Biard & Hervé Leuwers)

At the time of the Third Republic, Danton was celebrated way more than Robespierre, and the opposition between the memory of these two major protagonists of the Revolution developed. In Paris, in front of the Cour du Commerce and at the same place where the building rose in which the Dantons had lodged, the city erected a bronze statue in honour of the tribune (1891) ; on the occasion of the centenary of the Revolution, he was one of those that were honoured by the Republic. On its pedestal, two quotations allude [to Danton], the one being his call for audacity in the heat of the military tensions of the summer of 1792, and the other his conviction that the Republic had to provide education to the people in addition to guaranteeing the supplies that were supposed to nourish it. In France after 1870, while all eyes turned to Alsace and « la Lorraine », lost territories whose future reconquest had to become a national certainty, the figure tallied with the political ambitions of the moment … Once everything that could stand in the way was erased, the September Massacres and the accusations of corruption among others things, the portrait that was imposed was the one of the hero, of the great man of the Patrie en danger, of the martial tribune whom the young volunteers surround in the group sculpted by Auguste Paris. Some decades later, however, the offensives of Mathiez against Aulard, his former master, would revive the image of the corrupt politician and thereby shatter the hope of the republicans for a « consensual » Danton.

Danton: le mythe et l’Histoire (Michel Biard & Hervé Leuwers)

64 notes

·

View notes

Photo

French Revolution: Research Kit

Hello, citizens! This is a collection of tools, archives and primary sources that can facilitate research on the French Revolution ; all of them are accessible online for free.

primary sources

Histoire parlementaire de la Révolution française (40 volumes): parliamentary history of the French Revolution ; includes primary sources such as records, speeches, decrees etc.

Histoire du tribunal révolutionnaire de Paris (6 volumes): history of the Revolutionary Tribunal of Paris ; includes primary sources such as records, writings, orders etc.

La Société des Jacobins (6 volumes): Aulard’s history of the Jacobin Club ; includes primary sources such as records, speeches, writings etc.

Collection complète des lois, décrets, ordonnances, règlemens et avis du Conseil d'État (34 volumes): collection of the laws, decrees and orders that were issued between 1788 and 1830

Réimpression de l'ancien Moniteur (31 volumes): reprint of Le Moniteur Universel, which was one of the most prominent newspapers during the Revolution

Papiers inédits trouvés chez Robespierre, Saint-Just, Payan, etc. supprimés ou omis par Courtois. précédés du Rapport de ce député à la Convention Nationale (3 volumes): collection of documents that were found in the course of Courtois’ investigation ; includes many notes, letters and manuscripts written by Robespierre, Saint-Just, Couthon etc.

Archives Parlementaires (101 volumes): collection of the procès-verbaux of the legislative sessions during the French Revolution

Recueil des actes du Comité de salut public, avec la correspondance officielle des représentants en mission et le registre du conseil exécutif provisoire (30 volumes): collection of the orders and correspondences of the Committee of Public Safety

Œuvres de Robespierre (11 volumes): collected writings, letters and speeches of Maximilien Robespierre

Œuvres de Saint-Just (2 volumes): collected writings, letters and speeches of Louis Antoine Saint-Just

Œuvres de Marat (1 volume): collected writings, letters and speeches of Jean-Paul Marat

Œuvres de Danton (1 volume): collected writings and speeches of Georges Jacques Danton

Œuvres de Desmoulins (2 volumes): collected writings, letters and speeches of Camille Desmoulins

archives

French Revolution Digital Archive: project set up by the Stanford University Libraries and the Bibliothèque nationale de France ; offers free access to the Archives Parlementaires, as well as to an archive of images that were created during the French Revolution

Gallica: digital archive of the Bibliothèque nationale de France ; offers free access to images, writings and documents of the French Revolution

Guillotinés de la Révolution Française: portal searching the index of the people that were guillotined during the French Revolution

Condamnés à mort pendant la Révolution: portal searching the index of the people that were sentenced to death during the French Revolution

Emigrés de la Révolution Française: portal searching the index of the people that emigrated during the French Revolution

dictionaries

Dictionnaires d'autrefois: portal that searches Dictionaries from the 17th to the 20th century ; the fifth edition of the Dictionnaire de l'Académie française from 1798 is particularly helpful when researching terms in connection to primary sources of the Revolution

Dictionnaire de la révolution française: dictionary of institutions, persons and events in connection to the French Revolution

Dictionnaire des parlementaires français: dictionary of the French deputies from 1789 to 1889, offering brief biographical sketches of the representatives ; particularly useful when researching relatively obscure deputies

Feel free to add things, citizens. Have a nice day!

685 notes

·

View notes