Text

thou shalt find the winter’s rage freeze thy blood less coldly

On Christmas Day, Marius returned late from his daily wanderings to find a package on his bed.

There was no question of who it was for, as his name was on it, but there was no hint as to the sender. Slightly perturbed, Marius opened it. Inside was a thick scarf of blue wool, finely made and soft. This confused him even more. It was not hard to guess how the giver had gotten in, since he left his key in the door, but who would go out of their way to give him something? There were only a few people who knew where he lived. It was certainly not his grandfather, he could not imagine that it was Ma’am Bougon, and M. Mabeuf had never visited his home. And such a gift would not have been too cheap. Could it have been Her? His heart leapt at the thought, but it was impossible; she did not know his name, much less where he lived.

There was, however, one other person he could think of.

Marius put on his hat again, put the scarf under his arm, and left his apartment again. The December wind bit bitterly at his face, and his worn coat offered little protection. It was only becoming more worn as the months got colder, Marius thought ruefully, since the absence of a fireplace in his apartment made it necessary for him to wear it almost constantly. The scarf was nice. Still, he turned onto the rue Saint-Jacques.

As he expected, he saw Courfeyrac coming down the street from the hotel, and ran to meet him.

“Did you break into my room to give me this?” Marius asked.

Courfeyrac bowed. “Good day to you too, Baron Pontmercy. And I did not break into your room. You left your door unlocked.”

Of course.

“It is very generous of you, Courfeyrac, but—”

Courfeyrac held up his hand. “I won’t hear a word. My dear, I know you hate to accept anything from me, but it’s winter, your coat is wearing thin, you don’t even have a fire; it is frightful. I cannot bear to think of you catching your death in that dreadful place. Please just accept it, as a personal favor to me.”

“But I did not get you anything, and I owe you a great deal already,” Marius said peevishly. “You don’t owe a thing to me.”

Courfeyrac crossed his arms and suddenly looked serious. “Marius, has it ever occurred to you that I might actually like you?”

Marius blinked.

“I mean it. That there is more between friends than—than just debts and owing?” He took Marius’s arm and gestured with his cane. “I know all about your principles and your honor. But a friendship is not precisely calculated with debts and payments like a bank loan. Do not aspire to rid yourself of debts, you will rid yourself of brotherhood also—I myself have owed some sum of money to Bahorel for years, and for that reason he dines with me every day,” he laughed. “And since he dines with me every day we are good friends, and for that I have gone to the trouble of bailing him out of the police station once or twice.”

“Ought we to calculate exactly what is owed and avoid running up a debt of favors? Or is it better just to be good to each other as well as we can? I myself think the balance will work itself out. You have not studied your Desmoulins, young man. Fraternité means that we are all obliged to our fellow man. It is no shame to rely on the goodwill of others so long as we offer goodwill to others in our turn. That is what we all owe to the common brotherhood of man—it is the nature of the Republic, you know. And you have been a fine friend to me. I don’t help you because I expect anything else in return,” Courfeyrac said. “In other words,” he said, taking his hand, “your friendship is enough. You owe me nothing more.”

Marius pondered this idea in silence. It did not seem quite possible.

“And,” Courfeyrac added, as though reading his mind, “I am sorry if you have ever been taught otherwise.”

“It’s just that you have given me so much,” Marius said quietly. “And you ask for so little. And…I have so little to give you.”

“Your friendship is enough,” Courfeyrac repeated kindly.

Marius hesitated, then wrapped the scarf around his neck. He stared at the ground. “You are always so good to me,” he said. “Thank you. Truly. I don’t know how I’ll ever be able to repay you.”

Courfeyrac clapped him on the back. “Marius,” he said bracingly, “it’s only a scarf.”

Marius shook his head and began to turn away. “Merry Christmas,” Courfeyrac said, waving. “I suppose I’ll see you around?”

“Merry Christmas,” Marius responded vaguely. He took several steps in the opposite direction before stopping suddenly. He walked back up to Courfeyrac, who looked at him inquisitively. He embraced him.

Courfeyrac was caught off guard, but wrapped his arms around him warmly. “This is a welcome gift,” he laughed. “You never fail to surprise me.”

“Thank you,” Marius murmured. “For everything. I will make it all up to you. Someday.”

Courfeyrac sighed and patted his hair. “I’m sure you will. In the meantime, will you consent to having dinner with me?”

Marius released him. “I will.”

“And you can tell me about this girl you’ve been pining over for months,” Courfeyrac said, grinning.

Marius blushed and said nothing.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…thought flowers good for nothing except to conceal the sword.”

On the French Republican calendar:

June 6th— poppies

9 Thermidor— blackberries

22 Prairial— camomile

Lilies— fleur-de-lis, symbol of the Bourbons

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

the first drops of a storm

Dawn, the sixth of June

Enjolras had left the barricade half an hour ago—more or less, time seemed to move differently between these walls, Combeferre thought.

He’d slipped out quietly after whispering to him and Courfeyrac that he intended to survey the area, assess the present situation. He had promised to return within half an hour. “Be careful,” Combeferre had murmured, but Enjolras had already disappeared, catlike, into the shadows.

Thinking about Enjolras, how he could be captured or shot and them never even knowing left an anxious pang in his chest, so Combeferre returned to tending to the wounded. There were no very serious injuries, and the wounded men were adamant about being well enough for the next fight.

“I would not miss it for the world,” a young Southerner insisted, gritting his teeth from the pain. “This will be a history-making battle, the whole of the city is alight. By this time tomorrow we shall have a Republic and I will not miss my chance to be a part of it by sitting around in here.”

Combeferre could not help but smile at his enthusiasm. “Then at least rest for now, the bleeding is not heavy but you may aggravate it if you move too much. There’s still time before the next fight.”

The boy conceded this, and Combeferre left the wine-shop to ask Joly for more bandages. The sky was lightening. It was difficult not to share in their high spirits; the situation was hopeful. The fortification was good, they had ammunition. Above all, the bell of Saint-Merry rang out, reminding them that they were not alone.

As he passed the rue Mondétour, a figure appeared from the darkness, and he started.

A glimpse of blond hair, and the figure gestured for him to come closer—it was Enjolras, evidently back from his reconnaissance. Combeferre ran into the rue Mondétour, and Enjolras pulled him back into the shadows. He was uninjured, he noted with relief.

“Well? What news?" Combeferre said, wiping his hands on his apron. "The men are in high spirits, the Saint-Merry tocsin has not ceased for a moment. They are saying by sunset it will be a revolution. And by daybreak tomorrow—" he broke off, but could not repress a small smile. "But first tell me what you've seen."

Enjolras held his gaze steadily for a moment, then lowered his eyes. He shook his head.

Combeferre’s smile faded.

“A full third of the army is headed in this direction. They are bringing cannons.”

Combeferre began to feel the heavy weight of dread sinking in his chest. But there were other barricades remaining, surely.

“And the National Guard,” Enjolras added.

This was a blow. “They will not join us?”

“No.” Enjolras raised his eyes in meditation. “We have, perhaps, an hour before the attack, by my estimation.”

“But the faubourg,” Combeferre said, grasping.

“—is silent. Windows and doors shuttered. Nothing.” He exhaled, and Combeferre heard the smallest quaver in his breath. “There is no one coming. By daybreak tomorrow we will be dead.”

Combeferre found it necessary to lean against the wall for support. His head felt light, and a terrible numbness began to spread throughout his body. He turned to look past the intersection where the insurgents were engaged in preparation for the coming fight. The light of the torches and the joyful chatter of the men lent the scene almost the air of a street carnival, and he shuddered to picture the horrors that would befall them in such a short time.

“I will need to tell them,” Enjolras said softly. “I—”

Combeferre turned to look at him again, and for a moment Enjolras seemed to falter under the weight of the grief and exhaustion.

To know their fate, and then to deliver that fatal blow to hope. It was an unspeakable burden. “You are the bravest man I will ever know,” Combeferre finished for him. He took his hands. “What you have done—you could not ask more from any man.” He pulled him into an embrace, and Enjolras lay his head against his shoulder wearily.

“In the rue du Cygne I saw a window with a light in it on the fifth floor,” Enjolras murmured. “It was an old woman with a candle. I thought to myself, she may have spent the night in waiting.”

It struck Combeferre peculiarly that this was something that Enjolras had noticed, that was not something Enjolras would have noticed years before.

He drew him close and pressed their foreheads together. A lifetime of dreams had passed through them. There was a certain finality to this gesture, as he knew he would likely not have another chance to speak to Enjolras in confidence before the end came. For the last time he traced the features he knew so intimately with his thumb: the line of his jaw, the curve of his lips, the softness of his cheek. Enjolras clung to him tightly, as though he feared falling.

“It will come,” Combeferre said, his voice tight, but it was a promise.

“Yes,” Enjolras breathed. He pulled away, and drew himself upright once more.

The sky was now painted with broad swaths of color, fresh and resplendent. Their last sunrise, Combeferre thought. Yet there would be many more sunrises.

He turned, and was surprised to see Enjolras also gazing upwards. “It is beautiful,” he commented, but Combeferre knew he was not seeing the sky.

Enjolras stepped back towards the barricade, but Combeferre grabbed his wrist. One moment more, he pleaded.

“You know I would not be parted from you,” he said, “in life or in death.”

Enjolras smiled. “Yes,” he said. He stopped, then closed his eyes, as though readying himself.

They walked back into the rue de la Chanvrerie, towards the abyss, towards the dawn.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

generally speaking when someone new and super inexperienced but with their heart in the right place is introduced to your political group and starts talking about napoleon it is a bad idea to roast them so hard that they never come back. but it is, admittedly, kind of hot.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyone wanna be boy best friends

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

and every day is like a battle but every night with us is like a dream

new romantics // taylor swift

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

the caesar problem

Happy Ides of March and it is a lovely night to talk about the Caesar motif in Les Misérables, don't you think?

Caesar is not really important in his own right despite being regularly name dropped, the important thing is what he represents (arguably like Shakespeare's.) In this case, abstractly, glorious despotism, or specifically, Napoleon.

It was not a new comparison, and certainly not inherently derogatory, as it was frequently espoused by Napoleon's supporters—including his nephew Napoleon III, who later wrote a biography of Caesar in which he explicitly compared the two. Napoleon himself wrote commentaries on Caesar's battles, comparing himself and defending Caesar's dictatorship.

So the Caesar-Napoleon image was well formed in the French consciousness when Hugo published Les Mis. And Hugo plays along with it, and you'll find that comparison made in the Waterloo chapters and during Marius's "discovery" of Bonapartism—and, as is best remembered, in his speech to Les Amis.

You all know it (and Combeferre's response) and I've written about it before here.

The biggest thing to keep in mind is that Les Mis was published during the reign of Napoleon III while Hugo was in exile. He was in exile was for declaring the new Emperor a traitor to France, then published political pamphlets against him (one titled "Napoleon the Little") which were promptly banned, but smuggled into France.

Napoleon III himself was quite concerned with upholding his uncle's veneration in order to maintain the legitimacy of his own rule. So Combeferre and Marius's argument is not only about Napoleon's historical legacy, but highly relevant and provocative in the context the book was published.

This is only part of a broader dialogue about Caesar, though, partly narrated between Combeferre and Grantaire.

In fact Grantaire is the first to bring up Caesar in the chapter, as part of his first drunken ramble:

"Whom do you admire, the slain or the slayer, Caesar or Brutus? Generally men are in favor of the slayer. Long live Brutus, he has slain! There lies the virtue."

And again in "Preliminary Gaieties":

"Great accidents are the law; the order of things cannot do without them; and, judging from the apparition of comets, one would be tempted to think that Heaven itself finds actors needed for its performance. At the moment when one expects it the least, God placards a meteor on the wall of the firmament. Some queer star turns up, underlined by an enormous tail. And that causes the death of Caesar. Brutus deals him a blow with a knife, and God a blow with a comet. Crac, and behold an aurora borealis, behold a revolution, behold a great man; ’93 in big letters, Napoleon on guard, the comet of 1811 at the head of the poster."

In both cases he's being characteristically sarcastic, describing the inanity of these so-called great events, and as usual, the hypocrisy and wretchedness of the world.

On the other hand we have Combeferre, who is an interesting ideological objector here—first of all because he is the exact opposite of Grantaire with his utter belief in pure progress, but also because Combeferre is not necessarily the one you would expect to be a staunch defender of Caesar's assassination.

“Caesar,” said Combeferre, “fell justly. Cicero was severe towards Caesar, and he was right. That severity is not diatribe. When Zoïlus insults Homer, when Maevius insults Virgil, when Visé insults Molière, when Pope insults Shakespeare, when Frederic insults Voltaire, it is an old law of envy and hatred which is being carried out; genius attracts insult, great men are always more or less barked at. But Zoïlus and Cicero are two different persons. Cicero is an arbiter in thought, just as Brutus is an arbiter by the sword. For my own part, I blame that last justice, the blade; but, antiquity admitted it. Caesar, the violator of the Rubicon, conferring, as though they came from him, the dignities which emanated from the people, not rising at the entrance of the senate, committed the acts of a king and almost of a tyrant, regia ac pene tyrannica. He was a great man; so much the worse, or so much the better; the lesson is but the more exalted. His twenty-three wounds touch me less than the spitting in the face of Jesus Christ. Caesar is stabbed by the senators; Christ is cuffed by lackeys. One feels the God through the greater outrage.”

But there's his answer to Grantaire's first question. Combeferre, pacifist, lover of peaceful progress and frequently a mouthpiece for Hugo's own beliefs, thinks Caesar's assassination was justified. This lines up with a broader theme that starts all the way back with the Conventionist—that revolutions may be a necessary and justifiable part of progress, and that tyranny must not be tolerated despite the glories and greatness Marius points out, and despite the human costs of doing so. Combeferre himself is preparing to die on the barricade when he says this, so it feels like a justification for themselves and their actions.

And Combeferre gets the last word on this. Caesar isn't mentioned again in the book.

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Tell me more about simping for Hapgood.

I just...don't think it's that bad! (But I'm biased because it's the first translation I read.)

The main criticisms are that there are some errors (especially with numbers/dates) and cut lines, which is fair. There is some weird phrasing and mistranslations, but that's certainly not unique to this translation. (And I've written in the past about why one well known mistranslation may not be as straightforward as it seems.)

Another complaint is the use of thou to indicate the familiar second-person prounoun tu, as it does sound archaic and unnatural in English. However, it's not all the time--she uses it for situations where the familiarity of the dialogue is significant, such as the way Marius talks to Eponine or Valjean speaking to Cosette on his deathbed. And it really is important! Other translators have tried to find less clunky ways around it but are not particularly successful in my opinion. I think not acknowledging it at all removes a lot of the nuance in translation, so using thou is actually a decent approximation if you get what she's trying to do.

Basically it is a very literal, no-frills translation. And it's not particularly tailored to give English speakers an easy read, if that makes sense, which is not necessarily a bad thing.

To illustrate, one line everyone is familiar with:

Combeferre complétait et rectifiait Enjolras.

FMA and some other translations translate it as:

Combeferre completed and corrected Enjolras.

There's nothing wrong with this translation, I like it just fine. The alliteration sounds very pretty and rolls off the tongue easily, and it's still perfectly faithful to the original meaning.

Hapgood translates it considerably less prettily:

Combeferre complemented and rectified Enjolras.

But there is a slightly different connotation between "rectified" and "corrected". And Hugo does say "rectifiait". I think "rectify" sounds more amending, less punitive. "Correct" sounds harsher.

Possibly popular interpretations of these characters are influenced by this. Who knows?

Interestingly, in chemistry "rectify" also means "to refine or purify by repeated distillation or sublimation," which could be relevant.

Please note I am not saying "ooh if you're analyzing the book use Hapgood" Definitely do not use this translation without actually referring to the original for like, academic purposes due to the aforementioned errors, cut lines etc. (But like if you're doing Serious Academic Things you should be doing your own translation, every other translation also has its own drawbacks that could potentially cause problems.)

I am not writing this to be like Actually Hapgood is the Best Translation. It is not. it doesn't have fancy notes or updated language or the prettiest turns of phrase. But it is extremely accessible, it gets the job done just fine for the most part, and there are things about it that I do like better than other translations.

Also I like the nice covers you can get.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

All flocked around Marius. Courfeyrac flung himself on his neck.

“There you are!”

rolling up a day late for @courfeyracweek with an iced coffee

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

enjolras does not appreciate not getting attention…combeferre seems to think this is funny for some reason.

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

fuck around and find out

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

canon era dining

for @midasinc, who asked about food!

It's definitely not a dumb question! Sometimes the small details are the hardest to write and research, but they really add a lot of depth to your setting.

One of my primary motivations for learning French was because I HATE reading British sources on France from this period, which seemingly cannot go more than a few paragraphs without expounding on the superiority of British culture and civilization, and of course, complaining about the French. For example: French people are too happy. French women are too confident and converse with men too easily. French meat is too seasoned.

However, British travel guides are actually great resources for things like this, because they're actually meant to educate readers who aren't already familiar with 19th century Paris. So you can get lots of information about lodgings, culture, entertainment, and yes, food.

So what kinds of foods are we looking at? These are just a few examples of what you might find on Parisian menus in the 1820s-30s:

Meat and poultry: beef, mutton, ham, chicken, goose, duck, turkey, veal, partridge, quail, pigeon

Seafood: salmon, carp, turbot, mackerel, sole, oysters by the dozen

Vegetables: beans, potatoes, spinach, lettuce, asparagus, artichoke, celery, sorrel, cabbage

Fruits: lemon, pear, apple, apricot, cherry, plum, orange, grape, peach, strawberry, raspberry

Sauce: above British writer also complains that the French put sorrel sauce on everything.

And of course, bread, cheese, and wine. For actual meals, please refer to the menus.

One thing that struck me about the high-end fine dining establishments is the sheer size of the menus, which could have upwards of 100-250 dishes! I was originally going to post an actual menu, but that would make this post way too long, so you can just find them in my linked sources. For dinner at one of these restaurants, you might order a bottle or half-bottle of good quality wine, bread, a potage (thick soup), meat and fish, a vegetable entremet, dessert, and a small glass of liqueur. An English writer estimates the average cost of this meal at a fashionable restaurant to be about 9 francs, though one may be able to get a similar meal at other restaurants for 5-7 francs.

These prices, however, should not be considered the average cost of a meal in general, as it is noted that cheaper restaurants serve "four dishes, half-a-bottle of wine, a dessert, and as much bread as the guest chooses to eat, for 30 sous" (less than 2 francs.*) Meals could be bought at nearly any price point, from under 1 franc to over 10. At the low end of this range (though they varied widely), you could find traiteurs, eating houses where you could eat in or order food to be delivered to your house or apartment at a fixed time and price. You could also order cooked meats from a rotisseur, or apparently buy the meat yourself and send it to the rotisseur to have it seasoned and cooked.

An English writer notes of the people who live in Parisian apartments, “Many people living in this way keep no servant at all to themselves; they depend on the porter for taking any message which may come for them when they are not at home; they have their dinner sent by a traiteur at a fixed price by the day, and hire a woman by the week to come and make the beds and sweep the room.” This does sound very much like how Marius lives in the Gorbeau house, and Les Amis probably live similarly. Sometimes traiteurs would be attached to a certain lodging house or hotel, but even without it was sometimes possible to get your meals from wherever you lodged, cooked by the proprietress or her cook, as at the Thénardier inn.

It would of course be remiss to ignore the two locations most prominent in Les Mis—the Café Musain and the Corinthe cabaret. The word "cabaret" had not yet come into its modern usage and is typically translated into English as a public house, or pub. Cafés served coffee, liqueur, breakfast and lunch, with "sandwiches, chops, sausages, eggs, pates, with Burgundy, or some other excellent wine." It is noted that cafés do not usually serve dinner or supper.

Could they cook for themselves? Putting aside the question of should they cook, the answer is...it depends? A writer from the 1860s claims that nearly every apartment had a kitchen, albeit a very small one, basically a tiny room or alcove with a fourneau. But even if you don't have a kitchen, if you have a fire, you can theoretically cook. (And even if you don't, I guess—Marius doesn't have a fire but cooks his own meat, so presumably he uses Mme. Burgon's kitchen?)

Sorry for the long post, but we are talking about food…in France.

* 1 franc = 20 sous, 1 sou = 5 centimes

The New Picture of Paris, from the Latest Observations (includes menu for Grignion's)

Peter Hervé, 1829

A Narrative of Three Years' Residence in France, Principally in the Southern Departments, from the Year 1802 to 1805

Anne Plumptre, 1810

Bentley's Miscellany, Volume 54

1863

Tait's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 1

1834

The Student's Guide to the Hospitals and Medical Instituions of Paris

John Wiblin (M.R.C.S.), 1839

A Rough Sketch of Modern Paris

John Gustavus Lemaistre, 1803

A New Picture of Paris, Or, The Stranger's Guide to the French Metropolis (includes menu for Very's)

Edward Planta, 1831

Galignani's Picture of Paris, Being a Complete Guide to All the Public Buildings (includes menu for Brizzi's and Les Trois Frères Provençaux)

1818

Edited 1/27/22: a correction, added another source

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

university in canon era

for @sapphicfolch, who asked about school dates!

Since most of Les Amis are (ostensibly) students, it helps to have a grasp of what that actually looked like in 1820s/30s France. There weren’t a ton of choices for courses of study, so I'll only be talking about the law and medical schools here, because those are where we know at least some of the Amis are studying.

both schools have two months of vacation, 1 September to 1 November

possible days off: Sundays, 1st of the year, fête du roi (November 4 for Charles X, May 3 for Louis-Philippe,) Easter Monday, Whit Monday, Shrove Monday and Shrove Tuesday, feast day of Saint-Louis, presumably Christmas?*

*these are the days off for the colléges royaux, not the universities, but since they're mostly religious holidays, I think it's reasonable to assume that at least some of them would be the same?

law school

students must be at least 16 years old at registration

3 years of courses to be a licentiate, plus one optional year to obtain a doctorate

year 1, 1st trimester: natural law, international law, general public law. 2nd trimester: first course in the French Civil Code. 3rd trimester: history of Roman law and French law

year 2, 1st trimester: institutes of Roman law. 2nd trimester: second course in Civil Code. 3rd trimester: course in civil procedure

year 3, 1st trimester: third course in Civil Code. 2nd trimester: course in commercial law. 3rd trimester: course in administrative law.

however, it was completely possible that this process could take more than three years due to failing examinations, losing inscriptions, etc.

what happened to Bossuet was a real thing. Professors had to do a roll call twice a month. If a student answered for another student, they lost their inscription. If they failed to answer twice in three months, they lost their inscription.

medical school

two sessions, winter (1st Monday of November - 31 March) and summer (first Monday of April - 31 October) (vacation occurs during summer session)

dissections limited to the winter session, for obvious reasons

two weeks off for Christmas and between sessions

four years of courses with 16 terms, plus one year for examinations and thesis

year 1, winter session: anatomy, physiology, chemistry. summer session: medical pathology or hygiene, external pathology, botany.

year 2, winter: anatomy, physiology, practical medicine. summer: hygiene, pharmacy, external pathology, external clinics.

year 3, winter: practical medicine, external clinics. summer: materia medica, internal clinics.

year 4, winter: internal clinics, history of medicine, internal pathology. summer: legal medicine, clinique de perfectionnement, midwifery.

Some notes on the internat, since we know Combeferre was an interne:

In order to get hands-on hospital experience, students could take the highly competitive examinations for the externat and internat in November. Internes were lodged in the hospital, monitored patients, did night duties, assisted surgeons and physicians, and could act in their place in case of emergency. They received a stipend of 500 francs a year. Externes were not lodged in the hospital and performed more minor tasks, and were not paid.

must be at least 18 and provide proof of enrollment to take the exam to be an externe

internes are chosen from the existing pool of externes in a separate examination

must have at least one year of service as an externe to take the exam to be an interne

role of externes lasted two years, role of internes lasted 4 years

internes moved around to different hospitals to learn the different specialties and experience in both medicine and surgery

about 100 externes, 20-40 internes appointed each year. Selection of internes was highly competitive and political, aspiring students sought support from professors and doctors to gain an advantage.

I strongly recommend all of these sources to anyone hoping to go into more detail on this topic, they're a wealth of information and I couldn't put everything into this post.

Medical Students in England and France, 1815-1858

Florent Palluault, 2003

Code universitaire, ou Lois, statuts et règlemens de l'Université royale de France

Ambroise Rendu, 1835

A General View of the Present System of Public Education in France

David Johnston, 1827

Medical Guide to Paris: A description of the principal Hospitals of Paris

Félix Séverin Ratier, J. Rutherford Alcock, 1828

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

writing canon era dialogue

for @fennecfett and @juliensorelisoverparty who asked about canon era dialogue!

To be honest, there is not a ton of advice I can give on this front because at the end of the day, it's a personal stylistic choice. Especially in English there is no one right way to do it. Even just looking at actual translations of Les Mis, you'll see there's a wide variety of language used--from the overly archaic to the highly modernized. And if you read current historical fiction, you'll find that it's not necessarily written in the style of the period--or sometimes it is! It's completely your choice as a writer.

But for most writers, you probably want to find a happy medium between using super modern slang or throwing around "thee" and "thou" like Hapgood does. Some basic tips:

It is generally a more formal style, but again, the extent of this is really your choice. If your intent is to sound more authentic, you may want to imitate the style of your translation or other works from the period.

Remember that characterization isn't just what's said, but how they say it--and this holds for any fanfiction, not just in canon era. Grantaire's style of speaking is long and rambling, Combeferre's is short and cutting (think long rants vs snappy comebacks.) Enjolras is ordinarily quite taciturn, but his speeches are lyrical and soaring. Etc.

One of the hallmarks of how Hugo writes Les Amis is their wit! Hugo and his characters love puns and wordplay.

If you're not sure whether or not a word or phrase was used back then, Google Books Ngram viewer is your best friend, since it can show you the frequency of its occurrence over time.

One specific thing I will caution against is the idea that a shortcut to making speech sound "old fashioned" is to just omit contractions (making every "don't" into "do not," "wouldn't" into "would not," etc.) It's not true that contractions weren't used in English in the 19th century, and of course French uses plenty of contractions. You may want to use them less often to preserve the formality of the language, but omitting them entirely will just make your dialogue sound stilted and unnatural--and very distracting to modern readers.

I'd also love to see more acknowledgement that most of Les Amis would not only speak French, and may not speak French as a first language. Being from the South (except Lesgle), it's likely they would have also spoken a variety of regional dialects of Occitan.

Now for the actual sources!

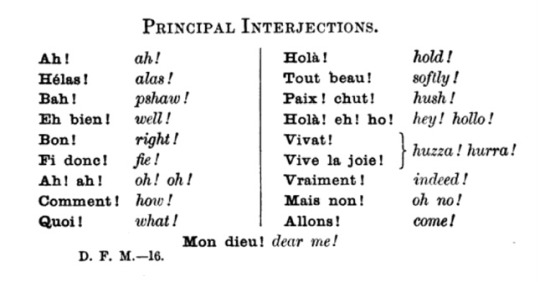

Since French in English language fanfiction is typically restricted to interjections or basic phrases, here's some from a French textbook from 1881.

(And of course, Courfeyrac's Pardieu!)

I also found something SO COOL while researching this: a French-English dictionary of idioms and proverbs, from 1830! Some examples:

"Does he expect that larks are going to fall roasted into his mouth?" > Does he expect a sudden fortune to fall to him?

"That's an ugly hat he's got there." > That's a bad mark on his character.

"He's in debt to God and the Devil." > He's up to his ears in debt.

"He drinks like a sponge." > He's a heavy drinker.

+ so many more! This is such a cool resource for canon era language, and definitely useful for adding a little color to your dialogue! The only thing is that the English translations in this book are NOT literal translations of the French, so it will help to have at least some knowledge of French.

For good measure, I've got two dictionaries of slang here too, although I'm not sure how useful they are for English language fic.

A Dictionary of Idioms, French and English

William A. Bellenger, 1830

New French Method

F. Duffet, 1881

Dictionnaire du jargon parisien: l'argot ancien et l'argot moderne

Lucien Rigaud, 1878

Argot and Slang: A New French and English Dictionary of the Cant Words, Quaint Expressions, Slang Terms and Flash Phrases Used in the High and Low Life of Old and New Paris

Albert Barrère, 1889

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

genuinely curious though, what kind of questions do people have about canon era or for writing canon era?

i know some older fandom resource posts have broken links or are hard to find so i’d love to put some new ones together, but i’d really like to hear what people are interested in learning about first!

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

some enjolras hair studies

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

“enjolras killed his friends and was also dumb and wrong”

The interpretation that Enjolras was a “naive little rich boy who got all his friends killed” is…certainly not new to this fandom, but it sometimes pops up in such an atrociously misinformed incarnation that I feel obliged to address it.

This interpretation itself is of course completely wrong, though perhaps encouraged by certain adaptations. But the idea that the rebellion failed because Enjolras “had no idea how to organize a revolt” and he just “ran around wearing a sash and shouting slogans at people”, and particularly that he “thought he could tell the working classes how to live better” is, frankly, appalling.

Enfranchisement during the July Monarchy was severely restricted, as voting rights were only given to males over 25 who paid 200 francs in direct taxes a year. So only about 1% of the population could vote—considerably less than even just the population of Paris alone. Since the voting pool was limited to wealthy, landowning men, elections swung conservative, and the regime supported policies intended to enrich the wealthiest bourgeoisie.

Not only were Enjolras and his friends disenfranchised, but they lived under an authoritarian regime and faced political repression and censorship. Do you have something called “freedom of speech” or “freedom of assembly”? Republican publications were routinely shut down by the government, and clubs and assemblies such as theirs were illegal. Members faced police raids, potentially large fines and months in prison.

Republicanism in the 1830s was a primarily working class movement. The majority of insurgents in the June Rebellion were working class. Enjolras, apart from also being a fictional character, is not a major player in the movement. He is the leader of a very small group that is affiliated with a few other groups in the area, and becomes the leader of a minor barricade during the June Rebellion. He is certainly not the orchestrator of the entire revolt, and it is ridiculous to suggest that, even fictiously, the reason for its failure is his own personal naivety.

You can debate the causes of the failure of the June Rebellion—of the insurgents to not march on the Hôtel de Ville or of the National Guard to not join the insurgents, or the brutality of the government’s reaction—it was not the failure of “the People” to rise, of whom an estimate of almost 400 were killed or wounded. Nor was the cause naive students running around inciting complacent workingmen to riot—rather a cholera epidemic that killed thousands, exacerbated poverty, and killed two prominent politicians.

If the failure of any people to rise is to be blamed, it might be the bourgeoisie, whom Hugo suggests were content with the gains of the liberal July Monarchy.

Enjolras is a highly effective leader. He’s a logical commander who takes care to not sacrifice more resources or men than necessary and is an exceptional (and most likely experienced) street fighter. His fictional barricade is inspired by the famous battle of the Cloître Saint-Merry in the same rebellion, which was used as symbol of republican martyrdom by later republicans. Hugo wrote it that way in order to illustrate what he saw as the sublimity of these men and the moment—he certainly did not see it as pointless or “ridiculous”.

Finally, the idea that Enjolras was responsible for the deaths of his friends or “dangerous to himself and his compatriots” is my most beloathed fandom invention. They were grown ass men who were just as devoted to the cause and just as willing to die for their ideals. Combeferre explicitly expresses his and the group’s willingness to die, and Grantaire obviously chooses to die with him. They were all capable of making their own decisions and it is weirdly infantilizing to suggest otherwise.

Why are people are so eager to make a mockery of Enjolras and his ideals?

Sources:

Ballots and Barricades, Aminzade

Barricades, Harsin

Proletarian Nights, Rancière

636 notes

·

View notes