Text

So recently I was listening to one of my favourite podcasts while on a business trip by train through the Swiss Alps to Zurich. 'The Rest Is History' hosted historians Dominic Sandbrook and Tom Holland were quite topical talking about France under de Gaulle and the student riots of 1968 as well as its legacy towards France’s current troubles with civil disorder.

The recent riots starting in Nanterre and beyond were troubling and significant. However outsiders not knowing the French or their culture and history thought it was either the fall of the Fifth Republic or start of the collapse of Western civilisation itself. It was nothing of the sort. For the most part the French think it healthy to blow off steam and have a jolly good riot in the same way people in England blow off steam by writing an angry letter to the editor of the Times. It’s just how things are. As predicted, things have gotten quiet now.

In their podcast Sandbrook and Holland cheekily suggested that the fizzling out of les evénéments – the student protests of 1968, during which it seemed that another of France’s periodic revolutions might ignite - had something to do with the Whitsun holidays. Realising that their Parisian parents were setting off for their holiday homes in the French countryside or the southern coast, the elitist student leaders put down their high minded revolutionary leftist philosophical slogans aside for the bourgeois comfort of vacances en famille. There is a lot of truth to that.

All this is to say les grandes vacancies have already begun in France. The grand vacation of July and August is an entrenched tradition in the French psyche. So ingrained is this tradition that until 2015 there were regulations still in place dating back to the French revolution that governed when bakers in Paris could take their holidays, so as not to deprive the city’s populace of their daily bread (not quite baguette, because that was invented later by the Austrians camped out in the Champs de Mars after the fall of Napoleon - but that’s another story).

That France is in the middle of les grandes vacances can be seen here in Paris. Parisians are leaving their apartments and heading out to the countryside or down south to the Med - to be offfeeling handedly rude and entitled towards the locals. Schools have been closed since June. Many shops are closed or not nearly as crowded as usual, most of the people wandering the streets have cameras around their necks. Of course not everyone goes and those that stay can feel freer until the first glut of tourists arrive.

For many France in August is definitely their favourite time of the year. And every summer I’m reminded just how much French language and culture are inseparable by the fact that there are words for people who take their annual vacation in July, les juillettistes, or in August, les aoûtiens.

Most French people have 5 weeks of paid vacation per year, and some have even more time off with the inclusion of their RTTs (essentially, personal days) for those who work more than 35 hours per week. I work close to 80 hours a week, so I'm ready for my break from the corporate treadmill.

So my blog will be shut down for the rest of the summer as I go away on vacation. I’ll be back in early September.

I use this time to switch off my phone and strictly no social media as I go off grid. It's a question of valuing one's mental health. I hope you can do the same.

Thank you for following my blog and appreciating my eclectic posts.

I wish you all the best.

Have a great summer!

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

ἆρʹ “ἀπίτω” τόδʹ ἔπος προσέφη; τάχʹ ἐθαύμασα πολλά.

τὸν δ᾽ ἀπαμειβομένη "ποῦ δεῖ μ᾽ άπίμεν;" τὸ προσηύδα.

καὶ τάδε δὴ ἔπεα μάλ' ἔτ' ἄξια φαἰνεται ὄντα.*

Homer, The Illiad

Go away? I was amazed.

Go away where? I said.

This still seems to me a good question.*

#homer#greek#classical#quote#literature#femme#beauty#outdoors#nature#countryside#journey#wanderlust#travel

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

Of the gladdest moments in human life, methinks, is the departure upon a distant journey into unknown lands. Shaking off with one mighty effort the fetters of habit, the leaden weight of routine, the cloak of many cares and the slavery of civilisation, man feels once more happy.

- Sir Richard Francis Burton, explorer and author

#burton#sir richard burton#quote#explorer#travel#traveller#exploration#suitcases#wanderlust#femme#adventure

409 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous ask: What do you think of the new Indiana Jones movie? And of Phoebe Waller-Bridge?

In a nutshell: From start to finish ‘Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny’ is watching Indiana Jones being a broken-down shell of a once great legacy character who has to be saved by the perfect younger and snarky but stereotypical ’Strong Independent Woman’ that passes for women characters in popcorn movies today.

I went in to this film with conflicted feelings. On the one hand I was genuinely excited to see this new Indiana Jones movie because it’s Indiana Jones. Period. Yet, on the other hand I feared how badly Lucasfilm, under Kathleen Kennedy’s insipid woke inspired CEO studio direction, was going to further tarnish not just a screen legend but the legacy of both George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. The cultural damage she has done to such a beloved franchise as the Star Wars universe in the name of progressive woke ideology is criminal. The troubled production history behind this film and its massive $300 million budget (by some estimates) meant Disney had a lot riding on it, especially with the future of Kathleen Kennedy on the line too as she was hands on with this film.

To me the Indiana Jones movies (well, the first three anyway, the less we say about ‘Kingdom of the Crystal Skull’ the better) were an important part of my childhood. I fell in love with the character instantly. Watching ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ (first on DVD in my boarding school dorm with other giggly girls and later on the big screen at a local arts cinema retrospective on Harrison Ford’s stellar career) just blew me away.

As a girl I wanted to be an archaeologist and have high falutin’ adventures; I even volunteered in digs in Pakistan and India (the Indus civilisation) as well as museum work in China as a teen growing up in those countries and discovering the methodical and patient but back breaking reality of what archaeology really was. But that didn’t dampen my spirit. Just once I wanted to echo Dr. Jones, ‘This belongs in a museum!’ But I happily settled for studying Classics instead and enjoyed studying classical archaeology on the side.

I couldn’t quite make sense why Indiana Jones resonated with me more than any other action hero on the screen until much later in life. Looking like Harrison Ford certainly helps. But it’s more than that. I’ve written this elsewhere but it’s worth repeating here.

‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ is considered an inspiration for so many action films yet there’s a very odd aspect to the film that’s rather unique and rarely noticed by its critics and fans. It’s an element that, once spotted, is difficult to forget, and is perhaps inspiring for times like the one in which we currently live, when there are so many challenges to get through. Typically in action films, the hero faces an array of obstacles and setbacks, but largely solves one problem after another, completes one quest after another, defeats one villain after another, and enjoys one victory after another.

The structure of ‘Raiders’ is different. A quick reminder:

- In the opening sequence, Indiana Jones obtains the temple idol only to lose it to his rival René Belloq (Paul Freeman).

- In the streets of Cairo, Indy fails to protect his love, Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen), from being captured (killed, he assumes).

- In the desert, he finds the long-lost Ark of the Covenant, only to have it taken away by Belloq.

- Indy then recovers the ark only to have it stolen a second time by Belloq, this time at sea.

- On an island, Indy tries to bluff Belloq into thinking he’ll blow up the ark. His bluff fails. Indy is captured.

- The climax of the film literally has its hero tied to a post the entire time. He’s completely ineffectual and helpless at a point in the movie where every other action hero is having their greatest moment of struggle and, typically, triumph.

If Indiana Jones had done absolutely nothing, if the famed archeologist had simply stayed home, the Nazis would have met the same fate - losing their lives to ark’s wrath because they opened it. It’s pretty rare in action films for the evil arch-villains to have the same outcome as if the hero had done nothing at all.

Indy does succeed in getting the ark back to America, of course, which is crucial. But then Indy loses the ark, once again, when government agents send it to a warehouse and refuse to let him study the object he chased the whole film. In other words: Indiana Jones spends ‘Raiders’ failing, getting beat up, and losing every artefact that he risks his life to acquire. And yet, Indiana Jones is considered a great hero.

The reason Indiana Jones is a hero isn’t because he wins. It’s because he never stops trying. I think this is the core of Indiana Jones’ character.

Critics will go on about something called agency as in being active or pro-active. But agency can be reactive and still be kinetic to propel the story along. It’s something that has progressively got lost as the series went on. With the latest Indiana Jones film I felt that Indiana Jones character had no agency and ends up being a relatively passive character. Sadly Indiana Jones ends up being a grouchy, broken, and beat up passenger in his own movie.

Released in 1981, ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ remains one of the most influential blockbusters of all time. Exciting action, exotic adventure, just the right amount of romance, good-natured humour, cutting-edge special effects: it was all there, perfectly balanced. Since then, attempts have been made to reproduce this winning recipe in different narrative contexts, sometimes successfully (’Temple of Doom’ and ‘the Last Crusade’), usually in vain (’Crystal Skull’).

What are the key ingredients of an Indiana Jones movie? There are only four core elements - leaving aside aspects of story such as the villain or the goal - that you need in place before anything else. They are: the wry, world-weary but sexy masculine performance of Harrison Ford; the story telling genius of George Lucas steeped in the lore of Saturday morning action hero television shows of the 1950s; the deft visual story telling and old school action direction of Steven Spielberg; and the sublime and sweeping music of the great John Williams. This what made the first three films really work.

In the latest Indiana Jones film, you only have one. Neither Lucas and Spielberg are there and arguably neither is Harrison Ford. John Williams’ music score remains imperious as ever. His music does a lot of heavy lifting in the film and let’s face it, his sublime music can polish any turd.

This isn’t to say the ‘Dial of Destiny’ is a turd. I won’t go that far, and to be honest some of the critical reaction has been over-hysterical. Instead I found it enjoyable but also immensely frustrating more than anything else. It had potential to be a great swan song film for Indy because it had an exciting collection of talent behind it.

In the absence of Spielberg, one couldn’t do worse than to pick James Mangold as next best to direct this film. Mangold is a great director. I am a fan of his body of work. After ‘Copland’, ‘Walk the Line’, ‘Logan’ and ‘Le Mans 66’ (or ‘Ford vs Ferrari’), James Mangold has been putting together a fine career shaped by his ability to deliver stories that rediscover a certain old-fashioned charm without abusing the historical figures - real or fictional - he tackles. And after Johnny Cash, Wolverine and Ken Miles, among others, I had high hopes he would keep the flame alive when it came to Indiana Jones. Mangold grew up as a fanboy of Spielberg’s work and you can clearly see that in his approach to directing film.

But in this film his direction lacks vitality. Mangold, while regularly really good, drags his feet a little here because he’s caught between putting his own stamp on the film and yet also lovingly pay homage to his hero, Spielberg. It’s as if he didn't dare give himself away completely, the director seems too modest to really take the saga by the scruff of the neck, and inevitably ends up suffering from the inevitable comparison with Steven Spielberg.

Mangold tries to recreate the nostalgic wonder of the originals, but doesn't quite succeed, while succumbing to an overkill of visual effects that make several passages seem artificial. The action set pieces range from pedestrian to barely satisfying. The prologue sequence was vaguely reminiscent of past films but it was still a little too reliant on CGI. The much talked about de-ageing of Harrison Ford on screen was impressive (and one suspects a lot of the film budget was sunk right there). But Indiana’s lifeless digitally de-aged avatar fighting on a computer-generated train, made the whole sequence feel like the Nazi Polar Express. Because it didn’t look real, there was no sense of danger and therefore no emotional investment from the audience. You know Tom Cruise would have done it for real and it would have looked properly cinematic and spectacular.

The tuk tuk chase through the narrow streets of Tangiers was again an exciting echo of past films, especially ‘Raiders’, but goes on a tad too long, but the exploration of the ship wreck (and a criminally underused cameo by Antonio Banderas) was disappointing and way too short.

The main problem here is the lack of creativity in the conception of truly epic scenes, because these are not dependent on Ford's age. Indeed, the film could very well have offered exhilarating action sequences worthy of the archaeologist with the whip, without relying solely on the physicality of its leading man. You don't need a Tom Cruise to orchestrate great moments but you could do worse than to follow his example.

Mangold uses various means of locomotion to move the character - train, tuk tuk, motorbike, horse - and offers a few images that wouldn't necessarily be seen elsewhere (notably the shot of Jones riding a horse in the middle of the underground), but in the end shows himself to be rather uninspired, when the first three films in the saga conceived some of the most inventive sequences in the genre and left their mark on cinema history. There are no really long shots, no iconic compositions, no complex shots that last and enrich a sequence, which makes the film look too smooth and prevents it from giving heft to an adventure that absolutely needs it.

And so now to the divisive figure of Phoebe Waller-Bridge.

It’s important here to separate the person from the character. I like Phoebe Waller-Bridge and I loved her in her ‘Fleabag’ series. She excels in a very British setting. I think she is funny, irreverent, and a whip smart talented writer and performer. I also think she has a particular frigid English beauty and poise about her. When I say poise I don’t mean the elegant poise of a Parisienne or a Milanese woman, but someone who is cute and comfortable in her own skin. You would think she would be more suited to ‘Downton Abbey’ setting than all out Hollywood action film. But I think she almost pulls it off here.

In truth over the years Phoebe Waller-Bridge, known for her comedy, has been collecting franchises where she is able to inflict her saucy humour into a hyper-masculine space. I don’t think her talent was properly showcased here.

Hollywood has this talent for plucking talented writers and actors who are exceptional in what they do and then hire them do something entirely different by either miscasting them or making them write in a different genre. I think Phoebe Waller-Bridge is exceptional and she might just rise if she is served by a better script.

In the end I think she does a decent stab at playing an intriguing character in Helena Shaw, Indy’s long lost and estranged god daughter and a sort of amoral rare artefacts hustler. Phoebe Waller-Bridge brings enthusiasm, charm and mischief to the role, making her a breath of fresh air. She seems to be the only member of the on-screen cast that looks to be enjoying themselves.

To be fair her I thought Waller-Bridge was a more memorable and interesting female character than either Kate Capshaw (’Temple of Doom’, 1984) and Alison Doody (’Last Crusade’, 1989). She certainly is a marked improvement on the modern woke inspired insipid female action leads such as Brie Larson (’Captain Marvel’), or any women in the Marvel universe for that matter, or Katherine Waterson (’Alien Covenant’). Waller-Bridge could have been reminiscent of Kathleen Turner (’Romancing the Stone’) and more recently Eva Green, actresses who command attention on screen and are as captivating, if not more so, than the male protagonists they play opposite.

To be sure there have been strong female leads before the woke infested itself into Hollywood story telling but they never made it central to their identity. Sigourney Weaver in ‘Alien’ and Linda Hamilton in the ‘Terminator’ franchise somehow conveyed strength of character with grit and perseverance through their suffering, while also being vulnerable and confident to pull through and succeed. Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s character isn’t quite that. She doesn’t get into fist fights or overpowers big hulking men but she uses cheek and charm to wriggle out of tight spots. She’s gently bad ass rather the dull ‘strong independent woman’ cardboard caricatures that Marvel is determined to ram down every girl’s throat. If Waller-Bridge’s character was better written she might well have been able to revive memories of the great ladies of Hollywood's golden age who had the fantasy and the confidence that men quaked at their feet.

What lets her character down is the snark. She doesn’t pepper her snark but she drowns in it. All of it directed at poor Indy and mocking him for his creaking bones and his entire legacy. It’s a real eyesore and it is a real let down as it drags the story down and clogs up the wheels that power the kinetic energy that an adventure with Indiana Jones needs. ‘The grumpy old man and the young woman with the wicked repartee set off across the vast world’ schtick is all well and good, but it does grate and by the end it makes you angry that Indy has put up with this crap. I can understand why many are turned off by Waller-Bridge’s character. As a female friend of mine put it, we get the talented Phoebe Waller Bridge’s bitter and unlikable Helena acting like a bitter and unlikable man. But it could be worse, it could be as dumb as Shia LaBeouf‘s bad Fonzie impersonation in 'Crystal Skull’.

I would say there is a difference between snark and sass. Waller-Bridge’s character is all snark. If the original whispers are true the original script had her way more snarkier towards Indy until Ford threatened to leave the project unless there were re-writes, then it shows how far removed the producers and writers were from treating Indy Jones with the proper respect a beloved legacy character deserves. It’s also lazy story telling.

Karen Black gave us real sass with Marion Ravenwood in ‘Raiders’. Her character was sassy, strong, but also vulnerable and romantic. She plays it pitch perfect. Of all the women in Indy’s life she was good foil for Indy.

Spielberg is so underrated for his mise-en-scène. We first meet Marion running a ramshackle but rowdy tavern in Tibet (she’s a survivor). She plays and wins a drinking game (she’s a tough one), she sees Indy again and punches him (she’s angry and hurt for her abandoning her and thus revealing her vulnerability). She has the medallion and becomes a partner (she’s all business). She evades and fights off the Nazis and their goons, she even uses a frying pan (she’s resourceful but not stupid). She tries on dresses (she’s re-discovers her femininity). Indy saves her but she picks him up at the end of the film by going for a drink (she’s healing and there’s a chance of a new start for both of them). This is a character arc worth investing in because it speaks to truth and to our reality.

The problem with Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s character is that she is constantly full on with the snark. Indy and Helena gripe and moan at each other the entire film. Indy hasn’t seen her in years, and she felt abandoned after her father passed, so there’s a lot of bitterness. It’s not unwarranted, but it also isn’t entertaining. It’s never entertaining if the snark makes the character too temperamental and unsympathetic for the audience to be emotionally invested in her.

I think overall the film is let down by the script. Again this is a shame. The writing talent was there. Jez and John-Henry Butterworth worked with James Mangold on ‘Ford v. Ferrari’ and co-wrote ‘Edge of Tomorrow‘ while David Koepp co-wrote the first ‘Mission: Impossible’ (but he also penned Indiana Jones and the ‘Kingdom of the Crystal Skull’, and the 2017 version of ‘The Mummy’ that simultaneously started and destroyed Universal’s plans for their Dark Universe). I love the work of Jez Butterworth who is one of England’s finest modern playwrights and he seemed to have transitioned fine over to Hollywood. But as anyone knows a Hollywood script has always too many cooks in the kitchen. There are so many fingerprints of other people - studio execs and directors and even stars - that a modern Hollywood script somehow resembles a sort of Ship of Theseus. It’s the writer’s name on the script but it doesn’t always mean they wrote or re-wrote every word.

Inevitably things fall between the cracks and you end up filming from the hip and hoping you can stitch together a coherent narrative in post-production editing. Clearly this film suffered from studio interference and many re-writes. And it shows because there is no narrative fluidity at work in the film.

Mads Mikkelsen’s Nazi scientist is a case in point. I love Mikkelsen especially in his arthouse films but I understand why he takes the bucks for the Hollywood films too. But in this film he is phoning in his performance. Mads Mikkelsen does what he can with limited screen time to make an impact but this character feels so recycled from other blockbusters. Here the CIA and US Government are evil and willing to let innocent Americans be murdered in order to let their pet Nazi rocket scientist pursue what they believe to be a hobby. But to be fair the villains in the Indy movies have never truly been memorable with perhaps Belloq, the French archaeologist and nemesis of Indy in ‘Raiders’, the only real exception. It’s just been generic bad guys - The Nazis! The Thugee death cult! The Nazis (again)! The Commies! Now we’re back to Nazis again which is not only safer ground for the Indy franchise but something we can all get behind.

However Mads Mikkelsen’s Dr. Voller, is the blandest and most generic Nazi villain in movie history. At the end of World War II, Voller was recruited by the US Government to aid them in rocket technology. Now that he’s completed his task and man has walked on the moon, he’s turning his genius to his ultimate purpose, the recovery of the ‘Dial of Destiny’ built by Archimedes. Should he find both pieces of the ancient treasure, he plans to return to 1930s Nazi Germany, usurp Hitler, and use his advanced knowledge of rocket propulsion to win the war. In a sense then he was channeling his inner Heidegger who felt Hitler had let down Nazism and worse betrayed Heidegger himself.

So there is a character juxtaposition between Voller and Indy in the sense both men feel more comfortable in the past than the present. But neither is given face time together to explore this intriguing premise that could have anchored the whole narrative of the film. It’s a missed opportunity and instead becomes a failure of character and story telling.

Then there are the one liners which seemed shoe horned in to make the studio execs or the writers feel smug about themselves. There are several woke one lines peppered throughout the film but are either tone deaf or just stupid.

“You trigger happy cracker”- it’s uttered without any self-awareness by a black CIA agent who is chaperoning the Nazi villain. Just because white people think it’s dumb and aren’t bothered by it doesn’t make it any less a racial slur. If you want authenticity then why not use the ’N’ word then as it would historically appropriate in 1969? The hypocrisy is what’s offensive.

“You stole it. He stole it. I stole it. It’s called capitalism.” - capitalism 101 for economic illiterate social justice warriors.

“[I’m] daring, beautiful, and self-sufficient” - uttered by Helena Shaw as a snarky reminder that she’s a strong independent woman, just in case you forgot.

“It’s not what you believe but how hard you believe.” - Indiana Jones has literally stood before the awesome power of God when the Ark of the Covenant was opened up by the Nazis, and they paid the price for it by having their faces melted off. Indy has drunk from the authentic cup of Christ, given to him by a knight who’s lived for centuries, that gave him eternal life and heal his father from a fatal bullet wound. So he’s figuratively seen the face of God (sure, he closed his eyes) and His holy wrath, and has witnessed the divine healing power of Christ first hand. And yet his spews out this drivel. It’s empty of any meaning and is a silly nod to our current fad that it’s all about the truth of our feelings, not observable facts or truth.

For me though the absolute worse was what they did to Indiana Jones as a character. Once the pinnacle of masculinity, a brave and daring man’s man whose zest for life was only matched by his brilliance, Henry Jones Jr. is now a broken, sad, and lonely old man. Indiana Jones is mired in the past. Not in the archaeological past, but in his own personal past. He's asleep at the wheel, losing interest in his own life. He's lost his son, he's losing his wife. He's been trying to pass on his passion, his understanding to disinterested people. They're not so interested in looking at the past. He remains a man turned towards the past, and then he finds himself confronted by Helena, who embodies the future. This nostalgia, this historical anchoring, becomes the main thread of the story.The film tries to deconstructs Indiana Jones on the cusp of retirement from academia and confronts him with a world he no longer understands. That’s an interesting premise and could have made for a great film.

It’s clear that the filmmakers’ intention was for a lost and broken Indiana to recapture his spirit by the film’s end. However, its horrible pacing and meandering and underdeveloped plot, along with Harrison Ford’s miserably sad demeanour in nearly every scene, make for a deeply depressing movie with an empty and unearned resolution.

By this I mean at the very end of the film. It’s meant to be daring and it is. There’s something giddy about appearing during the middle of siege of Syracuse by blood thirsty Romans and then coming face to face with Archimedes himself. The film seems to want to justify the legendary, exceptional aura and character of Indy himself by including him in History. Hitherto wounded deep down inside, and now also physically wounded, Indy the archaeologist tells Helena that he wants to stay here and be part of history.

It's a lovely and even moving moment, and you wonder if the film isn't going to pull a ‘Dying Can Wait’ by having its hero die in order to strengthen its legend. But in a moment that is too brutal from a rhythmic point of view, Helena refuses, knocks out her godfather and takes him back to the waiting plane and back to 1969. The next thing Indy sees he’s woken up back in his shabby apartment in New York.

I felt cheated. I’m sure Indy did too.

After all it was his choice. But Helena robbed him of the freedom to make his own decisions. She’s the one to decide what’s best. In effect she robbed him of agency. Even if it was the wrong decision to stay back in time, it’s so important from a narrative and character arc perspective that Indy should have had his own epiphany and make the choice to come back by himself because there is something worth living for in the future present - and that was reconciling with Marion his estranged wife. But damn it, he had to come to that decision for himself, and not have someone else force it upon him. That’s why the ending feelings so unearned and why the story falls flat as a soufflé when you piss on it.

‘Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny’ feels like the type of sequel that aimed to capture the magic of its predecessors, had worthwhile intentions, and a talented cast, but it just never properly materialised. In a movie whose pedigree, both in front and behind the camera, is virtually unassailable, it’s inexcusable that this team of filmmakers couldn’t achieve greater heights.

The film was a missed opportunity to give a proper send off to a cinematic legend. Harrison Ford proving that whatever gruff genre appeal he possessed in his heyday has aged better than Indy’s knees. He may be 80, but Ford carries the weight of the film, which, for all its gargantuan expense, feels a bit like those throwaway serials that first inspired Lucas - fun while it lasts, but wholly forgettable on exit.

I wouldn’t rate ‘Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny’ as the worst film in the franchise - that dubious honour still lies with ‘Kingdom of the Crystal Skull’. Indeed the best I can say is that I would rate this film at the benchmark of “not quite as bad as Crystal Skull”.But it’s definitely time to retire and hang up the fedora and the bull whip.

For what’s worth I always thought the ending of ‘Last Crusade’ where Indy, his father Henry Jones Snr., and his two most faithful companions, Sallah and Marcus Brody, ride off into the sunset was the most fitting way to say goodbye to a beloved character.

Instead we have in ‘Dial of Destiny’ the very last scene which is meant to be this perfect ending: Indiana Jones in his scruffy pyjamas and his shabby apartment. Sure, the exchange between a reconciling Indy and Marion is sincere and touching. But that only works because it explicitly recalls ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’. That's what Nietzsche would call “an eternal return”.

I shall eternally return to watch the first three movies to delight in the adventures of the swashbuckling archaeologist with the fedora and a bull whip. The last two dire films will be thrown into the black abyss. Something even Nietzsche would have approved of.

Thanks for your question.

#ask#question#indiana jones the dial of destiny#dial of destiny#indiana jones#lucasfilm#harrison ford#phoebe waller bridge#james mangold#steven spielberg#george lucas#john williams#kathleen kennedy#disney#film#cinema#movies#arts#cancel culture#personal

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

On ne lit jamais un livre. On se lit à travers le livre, soit pour se découvrir, soit pour se contrôler.

Claude Roy

387 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music is the poetry of the air.

Jean Paul Richter

A lot of you have asked me where I am. I am currently at the Verbier Festival, high up in the ski resort of Verbier in the Swiss Alps, with my family.

My family has had a home here since my grandparents time and this has always been a place to escape to ski in the winter season but also for the summer for its fantastic hiking, mountaineering, and biking. Verbier doesn’t have the glitz of Gstaad or the snob appeal of St. Moritz, which are both close by, that’s just fine by everyone who has a chalet here. People come to ski and just chill out.

The Verbier Festival has largely gone under the radar for the past 30 years as that’s the way many of the people wanted it. It’s only now very recently has it got a more public exposure and while that’s all well and good I hope it doesn’t grow bigger. It’s still small compared to other festivals and by virtue being high in the Swiss Alps space is limited so that venues have to be sequestrated from existing buildings and new stages or venues built - but can either be dismantled like an IKEA flat pack or not too big or too much of an eyesore. To date the festival now has grown to about 300,000 people over the two week period in July. Not bad when it started from scratch 30 years ago.

The festival was the brainchild of Martin Engstroem, a brilliant Swede who first came to the resort to ski with his family. But he was already in the classical music business as an influential music agent; indeed he has worked with some of the biggest names and rising talents in classical music.

Back in the early 1990s he shared this idea of inviting some musicians to just play in a very informal setting with other residents and the municipal authorities and the idea took off from there. In effect he just opened his address book and musicians came wanting a break from the madness of the concert circuit. It soon attracted some corporate support too as the visibility of the festival and the names it can headline has gotten bigger. And it’s grown from there, but not too much and not too fast. I think there is a feeling not to let it become a Frankenstein’s monster, and not to lose touch with its original ethos of keeping things simple.

But what’s different about Verbier from other more glamorous music festivals (like Salzburg for example), is how down to earth it is despite being so high up in the Alps. Musicians from all over the world love coming here because they love the unique setting high up in the Swiss Alps and they can be at ease and dress casual. There’s no barrier between performer and audience and there is plenty of intimate interaction too as musicians freely mix with the public in cafes and bars or just walking one the roads. There is no exclusionary atmosphere here (like the Royal Opera House or even Glyndebourne) because if you want that there are plenty of festivals that can give you that snob appeal.

Even better there is that there is so much going on outside the official concert venues. There are music workshops and talks peppered around the ski resort. There are also buskers from all over the world playing in cafés and open spaces. These are rising rock stars in the classical music world and yet they’re playing in very un-concert like settings in casual clothing, to get in touch with their inner child.

Speaking of which and perhaps best of all, children are spoiled with workshops and activities to install a love of music (be it classical or jazz or world music). My nephews and nieces love it.

Those youth with immense professional talent are given mentorship by some of the leading musicians in the world - Yo-Yo Ma if you are a cellist or Bryn Terferl if you’re an opera singer, Yuja Wang if you’re a pianist. And the list goes on. Much of the festival is to bring up and coming classical musicians with established rock stars together.

I don’t know of any other place go from watching world class musicians just jam together on the stage right in front of you, and then go get a drink in bar or café afterwards, before going on a glorious walk in the Alps to take in the beauty of nature; and then to finish the night with a performance by French iconic actress Isabelle Huppert reading, in a gorgeous gallic smoky voice, extracts from Marquie de Sade’s body of work in an intimate setting.

Whenever I find myself losing faith in humanity, I come back to the classical music and to the Verbier Festival. They are a great reminder that we are also able to produce beautiful things made out of strong and barely controllable emotions.

#verbier festival#music#classical music#family#concert#arts#culture#switzerland#swiss alps#musicians#personal

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wine is not just an object of pleasure, but an object of knowledge; and the pleasure depends on the knowledge.

Sir Roger Scruton, I Drink Therefore I Am

Si tu te souviens bien, il existe cinq bonnes raisons de boire : L'arrivée d'un hôte, la soif présente et à venir, le bon goût du vin et n'importe quelle autre raison.

#scruton#roger scruton#quote#wine#grape#drink#du vin#drinking#grapes#wine making#vitculture#oenology#french

499 notes

·

View notes

Text

Μικρού δ’ αγώνος ου μέγα έρχεται κλέος.

Sophocles

Little effort will not bring much glory.

#sophocles#greek#classical#quote#sports#effort#team work#beach volleyball#femme#beach#competitive#glory

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

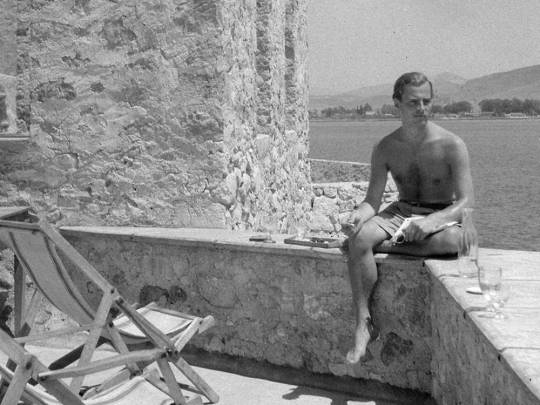

‘Pimpernel of the Hellenes’, ‘Major Paddy’, ‘Enchanted maniac’: Will the real Paddy Leigh Fermor please stand up?

Paradox reconciles all contradictions.

- Patrick Leigh Fermor

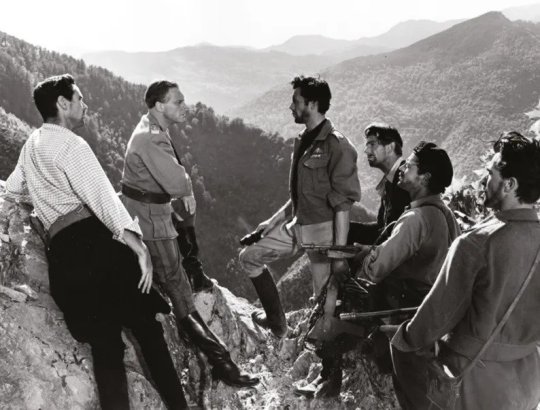

So one evening I was baby sitting my nephews and nieces here in our family chalet in Verbier, high up in the Swiss Alps. It was my turn to baby sit as the rest of my family enjoyed the fantastic classical music concerts and events showcased at the two week long Verbier 30th Festival. The little scamps had gone to bed and my father and I watched an old British war movie on DVD, ‘Ill Met By Moonlight’ (1957). It was filmed by the legendary team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger based on the 1950 book ‘Ill Met by Moonlight: The Abduction of General Kreipe’ by W. Stanley Moss.

I’ve seen the film a couple of times before, but until now never really paid attention to where the title came from. My father said it was from Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream’ And so it was. In the play, Oberon, the king of the fairies and the Queen are having a fairly bitter drawn-out fight over custody of a changeling Indian child, and this is how the pissed off king greets the queen when they run into each other, “Ill met by moonlight, proud Titania”. Oberon is basically saying "Oh Lord, it's you..." and Titania's response is basically a flippant middle finger. One of the best modern reasons to read Shakespeare: to throw playful erudite shade at others.

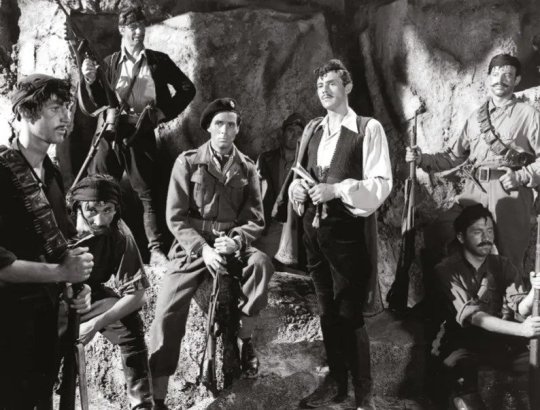

Anyway, the historical background of the film is the German invasion of Crete in May 1941. After an intense ten-day battle, Allied troops were driven back across the island, and many were evacuated from beaches along the southern coast. Some Cretans and British officers took to the mountains to organise resistance against the occupying forces. The German occupation that followed was especially brutal. Dreadful reprisals followed every act of resistance. The German commander, General Müller, insisted on taking 50 Cretan lives for every German soldier killed; he became known as ‘The Butcher of Crete’.

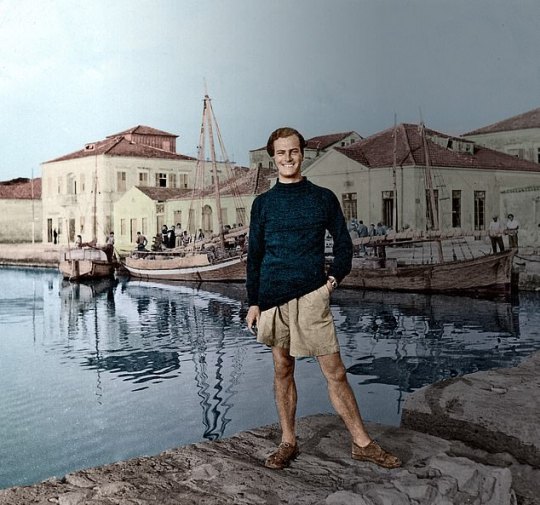

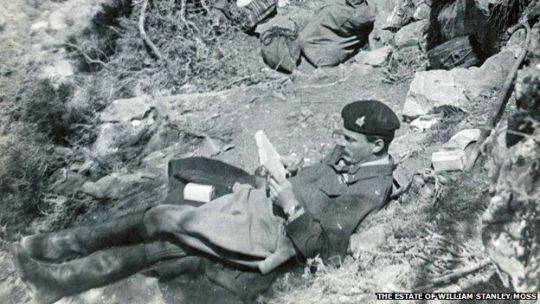

As a Classicist side note, there had been a close association between Britain and Crete since the early 20th century, when archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans had uncovered the sensational remains of a Minoan palace at Knossos. The headquarters of the British archaeological school in Crete was a large villa alongside the site, known as Villa Ariadne. Several archaeologists, who knew the island and its people well, went underground after the German occupation to aid the Cretan resistance. Continuing in this tradition, scholar and travel-writer Patrick Leigh Fermor, who had got to know Greece in the 1930s, joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

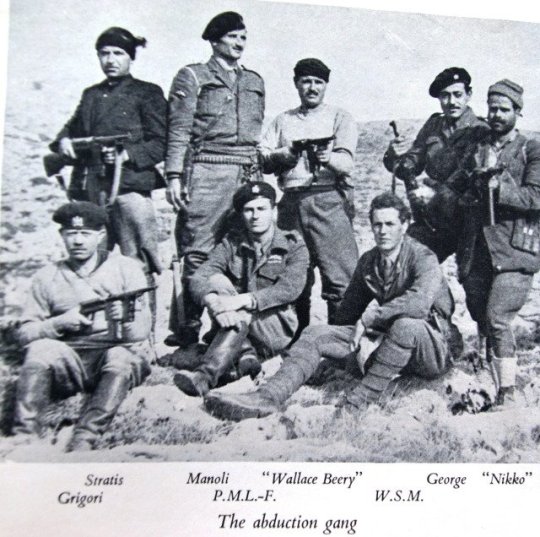

During the German occupation, Major Paddy Leigh Fermor travelled to Crete three times to help organise local resistance against the hated German occupation. On the third occasion, in February 1944, he was parachuted in with a specific mission to kidnap German commander General Müller, to boost morale on Crete along with his erstwhile SOE comrade Capt. W. Stanley Moss MC (aka Billy Moss) of the Coldstream Guards. However, just after they parachute in, General Müller was replaced by General Heinrich Kreipe, who transferred from the Russian Front. Thinking that capturing one general was as good as another, Fermor merrily go ahead with the daring kidnap operation.

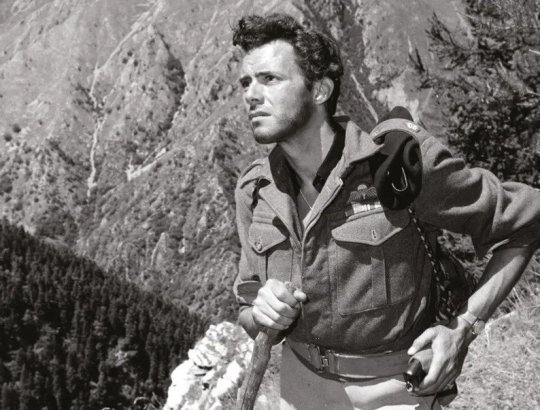

It’s at this point that the narrative of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s ‘Ill Met by Moonlight’ (1957) picks up. Dirk Bogarde plays Paddy Leigh Fermor, David Oxley plays Moss, and Marius Goring plays the taciturn German paratroop general. Blink and you’ll miss the late great Christopher Lee making a cameo appearance as a German officer in the dentist’s room scene.

The film naturally takes some liberty with the facts but it’s a cracking yarn of high adventure and drama. Xan Fielding, a close friend of Leigh Fermor from the SOE in Cairo, was taken on as technical adviser. The fact the film was shot in in the Alpes-Maritimes in France and Italy, and on the Côte d'Azur in France, far away from the craggy valleys and mountains of Crete itself. The director Michael Powell spent some time walking in Crete to get to know the island, but decided that, with the confused and volatile state of Greek politics, it was not suitable to film there.

Looking back years after he had directed it Powell didn’t think much of his own film. By contrast, Paddy Leigh Fermor, who was on set throughout the film shoot, was very happy with Bogarde’s portrayal of him with Byronic glamour. Watching the movie again ‘Ill Met by Moonlight’ remains a classic and stands out from many British war films of the 1950s because of its realism. The British SOE men and the Cretan guerrillas look absolutely right for their parts. It is dramatic and full of suspense while filled with much boyish humour.

I was disappointed with one notable omission in the film that did happen in real life. According to Patrick Leigh Fermor, at dawn one day during the journey across the mountains, General Kreipe was looking at the mist rising from Mount Ida and began to recite, in Latin, the opening lines of Horace’s ninth ode:

Vides ut alta stet nive candidum

Soracte nec iam sustineant onus

silvae laborantes geluque

flumina constiterint acuto?

Behold yon Mountains hoary height,

Made higher with new Mounts of Snow;

Again behold the Winters weight

Oppress the lab’ring Woods below:

And Streams, with Icy fetters bound,

Benum’d and crampt to solid Ground

(John Dryden 1685)

Leigh Fermor picked up on the General, and recited the remaining stanzas of the Ode. ‘Ach so, Herr Major,’ said Kreipe when Leigh Fermor had finished. Both men were amazed to realise they shared a classical education and a love of ancient Latin poetry.

Leigh Fermor later wrote that it was as though the war had ceased to exist for a moment, as ‘We had both drunk from the same fountains before.’ It brought captor and captive together with a strange bond. The scene was not reproduced in the film, as Powell and Pressburger probably thought it would make the men sound too academic for a popular cinema audience.

Leigh Fermor and Kreipe met again in the early 1970s, on a Greek television show, and got on famously together. The General said Leigh Fermor had treated him chivalrously as a captive. They remained friends until Kreipe’s death.

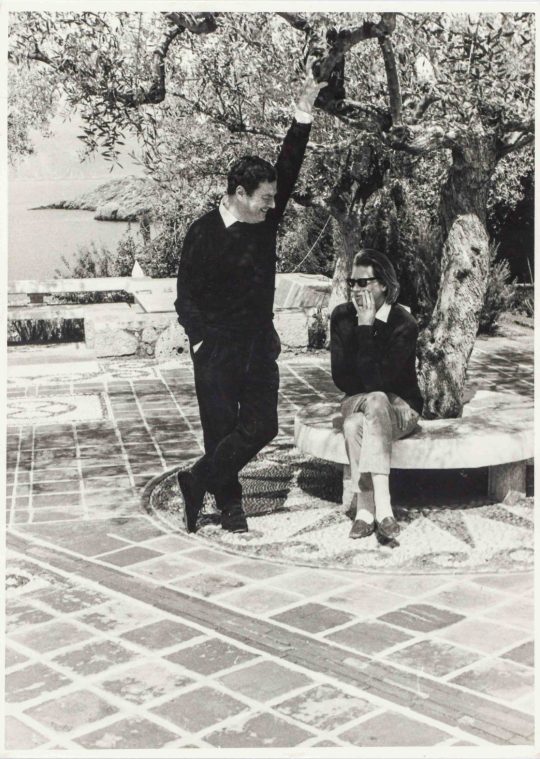

After sharing a late night drink with my father after the film, I began to muse on the figure of Paddy Leigh Fermor, a family friend and someone I met along with his wife, Joan, as a little girl. My grandparents, and especially my grandmother, knew Paddy briefly from their days during and after the Second World War.

My father shared a few stories about him when he and my mother visited his beautiful home in Greece, where even at his advanced age he remained the most generous of hosts and the most outrageous flirt.

One of my memories was getting into his battered old Peugeot in the drive way and trying to drive it when my feet could barely touch the pedals. It wouldn’t have mattered in any case as the brakes didn’t work as he cheerfully said later as we careened around a dirt road to go around the mountains for a drive.

Many years later in April 2022, I tried to visit the home of the late Patrick and Joan Leigh Fermor - a sort of pristine shrine to their memory that one can also stay in any of the rooms as a vacation rental - in the coastal fishing village of Kadarmyli in the Peloponnese, as part of a hiking and mountaineering sojourn around Greece with ex-Army friends. We couldn’t stay there as it was already rented out to other guests, and so we stayed higher up the mountain in a villa, but we swam in front of the Fermor’s home which was on the water’s edge.

You could never put your finger on Paddy Leigh Fermor. He hid behind his gift for telling yarns, and pulling Ancient Greek verses out of the thin air, as well as boisterously singing local Greek songs with a drink in his hand.

Even after his death in 2011, the question keeps nagging as to who was Paddy Leigh Fermor?

The Dirk Bogarde film too seems to ask, who exactly is the ‘real’ Patrick Leigh Fermor - or the real anyone? Taking its title from a Shakespearian play concerned with dreams and disguises, magic and power, ‘Ill Met By Moonlight’ is all about questions of identity.

Under the film credits, we see Dirk Bogarde in uniform; then, unexpectedly, we see him in the flamboyant outfit of a Cretan hill-bandit. A title informs us that Major Leigh Fermor was also known by the Greek code-name “Philidem.” In other words, there are two of him (at least), and on one level the adventure the film is about to unfold reflects a conflict in his personality. It’s a conflict shared, unknowingly, by his Nazi opposite number, the fierce, arrogant General Kreipe (an unlikely “proud Titania,” but it’s true that he “with a monster is in love” – the monster of Nazism). Kreipe’s human side is so rigorously repressed by the demands of war and “glory” that he is genuinely unaware of it; ironically, this humanness, which constitutes the true manhood of this Teuton warrior, is revealed by a boy (equivalent to Shakespeare’s Indian Prince?) - who, in turn, is the most grown up person in the movie.

If “Philidem” appears under the credits, caped and open-shirted, a romantic dream-figure out of an operetta or a storybook, he is first seen in the film proper as a coarser, more down-to-earth version of the same thing – an ordinary Cretan peasant in a shabby suit, waiting for a bus. When he makes contact with the Resistance, his personality fragments further.

To some, he is the mystical Philidem, Pimpernel of the Hellenes and righter of wrongs. To others he is “Major Paddy,” the happy-go-lucky Englishman of popular movie myth conducting war as if it were a branch of amateur theatricals, a gentleman adventurer relying on breeding to get him through and making fun of the whole business. To Bill Moss (David Oxley), the newly arrived junior officer sent to assist him, he is the cool, fast-thinking professional soldier. And to himself? In his quietly passionate defence of Cretan life and culture, he seems someone else again: a scholar and aesthete outraged by the barbarism and folly of war, and by the moronic arrogance shown by his captive toward the Cretan people.

Whatever his persona, Leigh Fermor is a chameleon who never seems to change very radically in himself. Perhaps because he has this quality of seeming all things to all men – and being those things - he remains unfazed by the monolithic might of the German military machine. Fluent in Greek, he can also speak German like a German and is easily able to assume another disguise, that of a faceless Nazi officer. Although he and Moss make fun of themselves - “If only I had a monocle!” muses Moss when Leigh Fermor tells him he “looks like an Englishman dressed like a German, leaning against the Ritz bar” - they are able to effect the kidnapping with an ease that seems appropriately Puckish. General Kreipe is ignominiously thrust onto the floor of his own limousine, gagged, and sat upon by a couple of the peasants he so despises. Kreipe’s rage is compounded by his firm conviction that he has been snatched by “amateurs” - a belief Leigh Fermor and Moss slyly make no objection to, knowing how it will gnaw at his already shaky Master Race self-confidence.

Patrick Leigh Fermor, aka Major Paddy, aka Philidem, in the film’s closing moments, is far from being self-assured intellectual or dashing amateur adventurer or legendary outlaw of the hills. He’s just a tired man who wants to go home and rest up. “How do you feel?” asks Moss. “Flat” is the reply. “You look flat!” says Moss. “I know how I’d like to look …” murmurs Leigh-Fermor wistfully. Moss knows what he’s going to say, and joins in the litany: “Like an Englishman dressed like an Englishman – and leaning against the Ritz bar!” It’s easy to imagine them ordering drinks at that renowned watering-hole with all the suavity required by this little fantasy.

Still, the film’s last images of Crete receding in the distance, until all we can see is the sea, suggests that maybe Major Paddy’s heart is really back in those hills in the “fair and fertile” land that has become as much a Powellian landscape of the mind for us as the studio-built Himalayan convent of ‘Black Narcissus’ or the monochrome Heaven of ‘A Matter of Life and Death’. And, as the film POV closing shots departs both Crete and this film, I began to think that being “dressed like an Englishman and leaning against the Ritz bar” would, for Patrick Leigh Fermor constitute yet another disguise. After all, he said he was of Irish aristocratic stock.

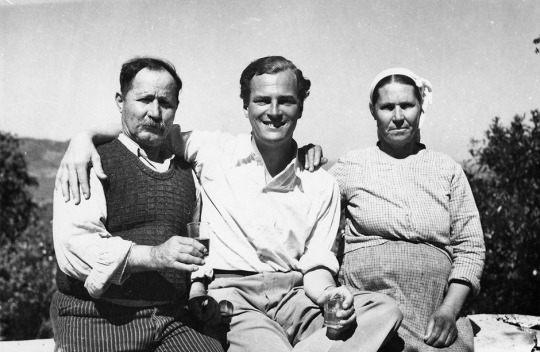

Traveller and writer Paddy Leigh Fermor is best known for two events. He’s known for leading the commando group in occupied Crete to kidnap General Kreipe. But he is also known for the boy who, at a mere 18 years old, set off with little money and a lot of nerve in 1933 to walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople.

Patrick Leigh Fermor was, in the words of one of his obituaries, a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene. Self-reliance and derring-do were lessons learnt from the cradle. When Fermor’s geologist father was posted to India, he and his wife left the infant with family in Northamptonshire and did not return until his fourth birthday. In retrospect, he took great delight in being sent to a school for difficult children and getting himself expelled from the King’s School, Canterbury, when he was caught holding hands with a greengrocer’s daughter eight years his senior. His school report infamously judged him ‘a dangerous mix of sophistication and recklessness’.

Sharing a flat in Shepherd’s Market, one of Mayfair’s seedier corners, Leigh Fermor schooled himself in literature, history, Latin and Greek.

He honed his character with the company of extraordinary people and the words of great writers - he had a prodigious memory for prose as well as poetry. He befriended literary lions such as Sacheverell Sitwell, Evelyn Waugh and Nancy Mitford. His travels began aged ‘eighteen-and-three-quarters’ when he rejected Sandhurst Royal Military College in order to walk the length of Europe from Hook of Holland to Constantinople. He took with him Horace’s Odes and the Oxford Book of Verse though Leigh Fermor could recite Shakespeare soliloquies, Marlowe speeches, Keats’s Odes and as he modestly put it ‘the usual pieces of Tennyson, Browning and Coleridge’ from memory.

Leigh Fermor was then a self-made man in the most literal sense.

Setting off from England in 1933, Fermor resolved to traverse Europe living like a hermit; sleeping in bars and begging for food. But his manly charms and boyish good looks found him being passed like a favourite godson from Schloss to palace by European nobility and he developed a lifelong penchant for aristocratic company. I his own words, ‘In Hungary, I borrowed a horse, then plunged into Transylvania; from Romania on into Bulgaria’. Having reached Constantinople in January 1935, Fermor continued to explore Greece where he fought on the royalist side in Macedonia quelling a republican revolution. In Athens Leigh Fermor met Balasha Cantacuzene, a Romanian countess with whom he fell in love. They were living together in a Moldovan castle when World War Two was declared.

Fluent in Greek, Leigh Fermor was posted as a liaison officer in Albania. Recruited as a Special Operations Executive (SOE), he was shipped from Cairo to German-occupied Crete where he lived disguised as a shepherd in the mountains for two years. On his third expedition to Crete in 1944, Leigh Fermor was parachuted alone onto the island and made connections in the Cretan resistance movement. While waiting for his compatriot Captain Bill Stanley Moss to land by water from Cairo, Leigh Fermor hatched a plot to kidnap German Commander General Heinrich Krieple. He liaised comfortably with Cretan partisans and bandits to pull off one of the war’s greatest coups de théâtre.

Disguised as German soldiers, Leigh Fermor and Moss stopped Krieple’s car at an improvised check point en route back to Nazi HQ in Knossos. Abandoning the General’s car after a two-hour drive, Leigh Fermor left a note indicating that the kidnappers were British so that there wouldn’t be reprisals against Cretan nationals. When the abduction of the unpopular commander was discovered, a German officer in Heraklion allegedly said ‘well, gentlemen, I think this calls for champagne’. It turns out that General Kreipe was despised by his own soldiers because, amongst other things, he objected to the stopping of his own vehicle for checking in compliance with his commands concerning approved travel orders. It’s why for instance the German troops, both in the film and in real life, dare not stop the General’s car as it drove through the check points at Heraklion.

Krieple was evacuated and taken to Cairo and Leigh Fermor entered the annals of World War Two’s most devil-may-care heroes. With characteristic panache, when he was demobbed Leigh Fermor moved into an attic room at the Ritz paying half a guinea a night. But his first travel book, ‘The Traveller’s Tree’, was not about the European odyssey or the Cretan escapades and centred on Leigh Fermor’s adventures in the Carribbean. Published in 1950, ‘The Traveller’s Tree’ was an inspiration for Ian Fleming’s second James Bond novel ‘Live and Let Die’ (1954).

As a host and house guest, Paddy Leigh Fermor was much sought-after. At one of his parties in Cairo, he counted nine crowned heads. He was a confirmed two-gin-and-tonics before lunch man and smoked eighty to 100 cigarettes a day. His party pieces included singing ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ in Hindustani and reciting ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’ backwards. In Cyprus while staying with Laurence Durrell, Leigh Fermor apparently stunned crowds in Bella Pais into silence by singing folk songs in perfect Cretan dialect. As Durrell wrote in ‘Bitter Lemons’ (1957), ‘it is as if they want to embrace Paddy wherever he goes’.

He struck up a partiuclar friendship with the famous Mitford sisters, especially Deborah Mitford, later ‘Debo’, the Duchess of Devonshire. It was at the Devonshires’ Irish estate Lismore Castle that ‘Darling Debo’ and ‘Darling Pad’ met and began to correspond. A characteristic letter from the Duchess in 1962 reads ‘The dear old President (JFK) phoned the other day. First question was ‘Who’ve you got with you, Paddy?” He’s got you on the brain’ to which Fermor replies of a broken wrist ‘Balinese dancing’s out, for a start; so, should I ever succeed to a throne, is holding an orb. The other drawbacks will surface with time’.

After the war he travelled widely but was always drawn back to Greece. He built a house on the Mani peninsula - which had been, significantly, the only part of Magna Graecia to resist Ottoman colonisation since the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Before his death in 2011 at the age of 96, he wrote some of the most acclaimed travel books of the 20th century.

His books contain some of the finest prose writing of the past century and disprove Wilde's maxim that "it is better to have a permanent income than to be fascinating".

Charm, self-taught knowledge and enthusiasm made up for the lack of a university degree or a private income. His teenage walk across Europe and subsequent romantic sojourn in Baleni, Romania, with Princess Balasha Cantacuzene are proof enough of that. But the difficulty of capturing such an unconventional and glamorous life is made harder by the certainty that Fermor was an unreliable narrator.

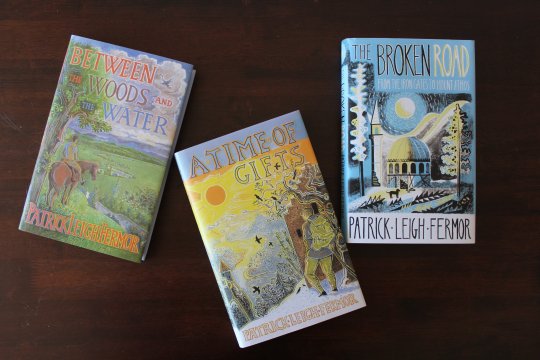

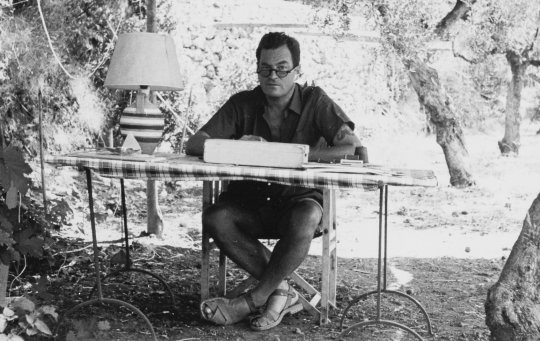

He was also an infuriatingly slow writer. Driven by a life-long passion for words yet hampered by anxiety about his abilities, Leigh Fermor published eight books over 41 years.

‘The Traveller's Tree’ describes his postwar journey through the Caribbean; ‘Mani‘ and ‘Roumeli’ (1958 and 1966) draw on his experiences in Greece, where he would live for much of the latter part of his life. But it is the books that came out of his trans-Europe walk that reveal both the brilliance and the flaws. ‘A Time of Gifts’ was published in 1977, 44 years after he set out on the journey. ‘Between the Woods and the Water’ appeared nine years later. Both describe a world of privilege and poverty, communism and the rising tide of Nazism, and end with the unequivocal words, "To be continued". Yet the third volume hung like an albatross around the author's neck. As the years passed, Fermor found it impossible to shape the last part of his story in the way he wanted.

Leigh Fermor was that rarest of men: a man determined to live on his own terms, if not his own means, and who mostly - and mostly magnificently - succeeded. Always popping off on a journey when he should have been writing about the last one, always ready to party, he was forever chasing beautiful, fascinating or powerful women, even when with his wife, Joan Raynor. She was the great facilitator who funded his passion for travel and writing, as well as women, from her trust fund. His love affairs were discreet but legendary.

Leigh Fermor was happiest among the rogues. Over a lifetime on the road, he sought them, and in turn they responded to his charm, nose for adventure, and his famous wit. He was a keenly-anticipated dinner guest - once outshining Richard Burton at a London society soirée, who he cut-off midway through a recital of ‘Hamlet’. As Richard Burton stormed out, the pleading society hostess said, “But Paddy’s a war hero!” to which Burton grouchily replied, “I don’t give a damn who he is!”

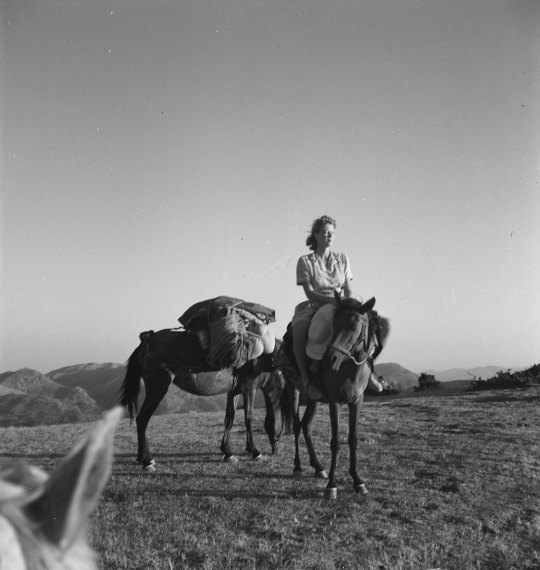

His partnership with and then marriage to Joan Raynor was an open relationship, at least on Leigh Fermor’s side. Paddy saw in Joan his kindred spirit. Like him, she spent much of her youth travelling to where she pleased; largely in France, where the photographer and literary critic Cyril Connolly became besotted by her. Joan was the daughter of Sir Bolton and Lady Eyres Monsell of Dumbleton Hall, Worcestershire. She was not only stunningly pretty but also 'a beautiful ideal, with the perfect bathing dress, the most lovely face, the most elaborate evening dress', as the Eton educated Connolly described her. Joan also stood out from the upper-class beauties of her day in that she supplemented her mean rich father's allowance by earning her living as a decent photographer.

In 1946, she met Leigh Fermor in Athens, while he was deputy director of the British Institute. Joan met him at a time when he was then in a relationship with a French woman called Denise, who was pregnant with his child, which she aborted. The pair would travel to the Caribbean together under the invitation of Greek photographer Costas, falling madly in love.

She was the only woman that - after decades of sexual scandals - matched his own erratic behaviour. Stories of how they dined fully-clothed in the Mediterranean, dragging a table into the sea, as well as their myriad cats and olive groves, paint a restless couple, who, when not out articulating the peoples of their adopted homeland, kept themselves very busy.

The attraction between Paddy and Joan was instant. So many love affairs that Paddy indulged in seemed about as brief as the flame from a burning envelope and you expected this one with Joan to be too. But somehow, miraculously, it lasts.

The two were apart a great deal, but in their case, absence did make the heart grow fonder. While Paddy was staying in a monastery in Normandy, supposed to be thinking monk-like thoughts that he would eventually put into his masterpiece A Time To Keep Silence, he was also writing sexy letters to Joan: 'At this distance you seem about as nearly perfect a human being as can be, my darling little wretch, so it's about time I was brought to my senses.' And: 'Don't run away with anyone or I'll come and cut your bloody throat.'

She tantalised him with descriptions of Cyril Connolly making passes at her; but she, like Denise, sounded a rather desperate note when she wrote: 'I got the curse so late this month I began to hope I was having a baby and that you would have to make it a legitimate little Fermor. All hopes ruined this morning.'

Fiercely independent - a trait that must have enamoured Paddy - they were best imagined as two pillars of a Greek temple, beside one-another but capable of holding up the roof of the world that they had built for themselves through the lens of ancient history and Hellenic culture. Indeed, it was said that they had a special ‘pact of liberty’. It is this unconquerable aura that led poet laureate John Betjeman to declare his love for her (he called her ‘Dotty’ and remarked that her eyes were as large as tennis balls). For Cyril Connolly, the photographer she shadowed, and with whom she had a scandalised affair during her first marriage, she was a “lovely boy-girl” and Laurence Durrell named her the ‘Corn Goddess’ because of her slender figure and short hair. But of all of these worthy candidates, it was the warrior-poet Patrick Leigh Fermor who finally won her heart.

To Joan, who described herself as a ‘lifelong loner’ in her diaries, her companionship with the uncomplicated Paddy was a relief. They had no children, nor did they want any - or so Paddy claimed. But those who knew Joan suspected she did want children but it never came to pass; and so she became a devoted aunt or dotted on other friends’ children. For both of them their dozens of cats gave them the next best thing to paternal satisfaction. Still, her morbid fascination with photographing cemeteries painted a much darker side.

Joan Raynor’s inheritance subsidised his peripatetic life at least until the enormous success of ‘A Time of Gifts’ in the late 1970s, which in turn created a new market for his previous volumes about Greece, ‘Mani’ and ‘Roumeli’.

With Joan’s tacit consent, Paddy enjoyed amorous flings, discrete sexual affairs with high society women and sampled the low delights of the brothel. This activity rarely made it into his private letters, but the exceptions could be piquant. Writing in 1958 from Cameroon, where he was on the set of a John Huston movie, he told a (male) friend: “ Errol Flynn and I . . . sally forth into dark lanes of the town together on guilty excursions that remind me rather of old Greek days with you.” In a 1961 letter to the film director John Huston’s wife, Ricki, with whom Leigh Fermor had been having sex with (and would die in a car crash in 1969). “I say,” the passage begins, “what gloomy tidings about the CRABS! Could it be me?” Riffing on pubic lice and their crafty ways, he conjectures that, during a recent romp with an “old pal” in Paris, a force “must have landed” on him “and then lain up, seeing me merely as a stepping stone or a springboard to better things” - to Mrs. Huston, that is. As comic apologies for venereal infection go, the passage is surely a classic.

Like most high flying lives, it was far from blameless. Wounded women were littered in his wake. Some British visitors to Athens were less than impressed by this Englishman who posed as “more Greek than the Greeks”.

Some Greeks shared their disdain. Revisionist historians criticised his role in wartime Crete, and warned their fellow Hellenes that for all his fluency and charm, Leigh Fermor was no latter day Byron. His unoccupied car was blown up outside his Mani house, probably by members of the Greek Communist Party which he had vocally opposed. The accidental fatal shooting of a partisan in Crete led to a long blood feud which made it difficult for Leigh Fermor to re-enter the island until the 1970s, and possibly explains why he chose to settle in the Peloponnese rather than among the hills and harbours of his dreams.

His own books had already eclipsed those incidents, not only among readers of English but also in Greece, where in 2007 the government of his adopted land made him a Commander of the Order of the Phoenix for services to literature.

Travel writers such as the great Jan Morris have described Leigh Fermor as the master of their trade and its greatest exponent in the 20th century.

When ‘A Time of Gifts’ was published in 1977, Frederick Raphael wrote: “One feels he could not cross Oxford Street in less than two volumes; but then what volumes they would be!”

They are not for everyone. Leigh Fermor wrote that written English is a language whose Latinates need pegging down with simple Anglo-Saxonisms, and some feel that he personally could have made more and better use of the mallet. His exuberance is either captivating or florid. It is certainly unique among English prose styles.

Artemis Cooper, his patient and careful biographer wrote that “Paddy had found a way of writing that could deploy a lifetime’s reading and experience, while never losing sight of his ebullient, well-meaning and occasionally clumsy 18-year-old self … this was a wonderful way of disarming his readers, who would then be willing to follow him into the wildest fantasies and digressions”.

Those fantasies and digressions took decades to express. ‘A Time of Gifts’ had arguably been 40 years in the making when it was published in 1977. Its sequel, ‘Between the Woods and the Water’, did not appear until 1986. The third and final volume has been awaited ever since. Following Leigh Fermor’s death, a foot-high manuscript was apparently found on his desk.

Once he knuckled down to it, Leigh Fermor loved playing around with words. He was one of our greatest stylists and he was devoted to producing un-improvable books. But writing did not come easily to him, at least partly because it was something of a distraction from the main event, which was living an un-improvable life of unrepentant gaiety and fun.

For forty odd years, a legion of friends and admirers would beat a path to Paddy and Joan’s door. Artists, poets, royalty and writers came, all taking inspiration from their erudite hosts. A visit was an act of communion, a sharing of ideas and stories.

Leigh Fermor influenced a generation of British travel writers, including Bruce Chatwin, Colin Thubron, Philip Marsden, Nicholas Crane, Rory Stewart, and William Dalrymple. Indeed when Bruce Chatwin died, it was Paddy who scattered Chatwin’s ashes near a church in the mountains in Kardamyli.

When I was there in April 2022, I went to that same church to pay my respects.

But some of Paddy’s life energy was sucked out of him when Joan died in Kardamyli in June 2003, aged 91. It was related that Joan said to her friend Olivia Stewart, who was visiting: 'I really would like to die but who'd look after Paddy?' Olivia said that she would. A few minutes later, Joan fell, hit her head - and died instantly of a brain haemorrhage. Joan had often quoted Rilke: 'The good marriage is one in which each appoints the other as guardian of his solitude.' Now Paddy Leigh Fermor was all alone.

Leigh Fermor was knighted in 2004, the day of his birthday which he delighted in like a giggling schoolboy. But he missed Joan terribly.

For the last few months of his life Leigh Fermor suffered from a cancerous tumour, and in early June 2011 he underwent a tracheotomy in Greece. As death was close, according to local Greek friends, he expressed a wish to visit England to bid goodbye to his friends, and then return to die in Kardamyli, though it is also stated that he actually wished to die in England and be buried next to his wife, Joan, in Dumbleton, Gloucestershire. He stayed on at Kardamyli until the 9th June 2011, when he left Greece for the last time. He died in England the following day, 10th June 2011, aged 96. It was reported that he had dined in full black tie on the evening of his death. Paddy had style even unto the end.

A Guard of Honour was formed by the Intelligence Corps and a bugler from his former regiment, the Irish Guards, delivered the ‘Last Post’ at Paddy’s funeral. As had been his wish, he was buried beside Joan. On his gravestone in Dumbleton cemetery is an inscription in Greek, a quote from Constantine Cavafy: “In addition, he was that best of all things, Hellenic.”

Although Joan had passed away at the age of ninety-one, after suffering a fall in the Mani. Her body was repatriated to Dumbleton, the place of her birth - ironic that her dream was to be as far as she could possibly go from the rolling humdrum Worcestershire hills. But perhaps she intended to return all along. When Paddy was buried beside her it seemed that the ‘pact of liberty’ that these two lonely souls had forged themselves could be tested in the great elsewhere. Joan was more than his muse (as many of her obituaries were at pains to declare) but his greatest adventure.

To come around full circle from the movie ‘Ill Met By Moonlight’ (1957) that I saw that night in Verbier, my father told me that rather poignantly, General Kreipe, the German commander Leigh Fermor had captured - once an enemy, and later a friend - left behind notes and photographs from across his life. On one of those notes, it was discovered, the following was scribbled from a brief visit to Greece: “Somewhere, amidst all the disarray, was the story of Joan and Paddy, and” it concluded, “…of their lives together.”

His life with Joan and all that she meant to him was one part of the mosaic of who Paddy Leigh Fermor was. But it’s incomplete.

Paddy didn’t like the idea of a biography, and neither did Joan when she was alive. But friends had persuaded them that unless Paddy appointed someone to write his life, he might find himself the subject of a book whether he liked it or not. In Artemis Cooper they couldn’t have chosen a better writer to chronicle Paddy’s life as a man of action and letters. Cooper, was the daughter of another accomplished diplomat and historian, John Julius Norwich, and grand-daughter of Duff and Diana Cooper. As the wife of the historian Antony Beevor, she became a trusted friend of the Leigh Fermors. Cooper was too good of a historian to let her friendship lead her astray from being a faithful but serious biographer. Knowing this, she was told she could go ahead, but she had to promise not to publish anything until after they were both dead.

Paddy did not like being interviewed, and would keep her questions at bay with a torrent of dazzling conversation. He was the master at deflecting discussions away from himself.

He was also very unwilling to let Cooper see many of his papers, though the refusal always couched in excuses. ‘Oh dear, the Diary…’ It was the only surviving one from his great walk across Europe, and I was aching to read it. ‘Well it’s in constant use, you see, as I plug away at Vol III,’ he would say. Or, ‘My mother’s letters? Ah yes, why not. But it’s too awful, I simply cannot remember where they’ve got to…’ It was quite obvious that he and Joan, while being unfailingly generous, welcoming and hospitable, were determined to reveal as little as possible of their private lives.

While they were more than happy to talk about books, travels, friends, Crete, Greece, the war, anything - they would not tell her any more than they would have told the average journalist. But she persisted and got closer than most. He showed particularly gallantry in not talking about his romantic entanglements. But she soon twigged that anytime he described a woman as ‘an old pal’ it was a sure bet that he had an affair with her.

Intriguingly, Paddy liked to claim he was descended from Counts of the Holy Roman Empire, who came to Austria from Sligo. Paddy could recite ‘The Dead at Clomacnoise’ (in translation) and perhaps did so during a handful of flying visits to Ireland in the 1950s and 1960s, partying hard at Luggala House or Lismore Castle, or making friends with Patrick Kavanagh and Sean O’Faolain in Dublin pubs. He once provoked a massive brawl at the Kildare Hunt Ball, and was rescued from a true pounding by Ricki Huston, a beautiful Italian-American dancer, John Huston’s fourth wife and Paddy’s lover not long afterwards.

And yet, a note of caution about Paddy’s Irish roots is sounded by his biographer, Artemis Cooper, who also co-edited ‘The Broken Road’, the final, posthumously published instalment of the trilogy. “I’m not a great believer in his Irish roots,” she said of Leigh Fermor in an interview, “His mother, who was a compulsive fantasist, liked to think that her family was related to the Viscount Taaffes, of Ballymote. Her father was apparently born in County Cork. But she was never what you might call a reliable witness. She was an extraordinary person, though. Imaginative, impulsive, impossible - just the way the Irish are supposed to be, come to think of it. She was also one of those sad women, who grew up at the turn of the last century, who never found an outlet for their talents and energies, nor the right man, come to that. All she had was Paddy, and she didn’t get much of him.”

And I think that’s the point, no one really got much of Paddy Leigh Fermor even as he only gave a crumb of himself to others but still most felt grateful that it was enough to fill one’s belly and still feel overfed by him.

Paddy never tried to get to the bottom of his Irish ancestry, afraid, no doubt, of disturbing the bloom that had grown on history and his past, a recurring trait. “His memory was extraordinary,” Artemis Cooper noted, “but it lay dangerously close to his imagination and it was a very porous border.”

Within the Greek imagination many Greeks saw in Paddy Leigh Fermor as the second coming of Lord Byron. It’s not a bad comparison.

Lord Byron claimed that swimming the Hellespont was his greatest achievement. 174 years or so later, another English writer, Patrick Leigh Fermor - also, like Byron, revered by many Greeks for his part in a war of liberation - repeated the feat. Leigh Fermor, however, was 69 when he did it and continued to do it into his 80s. Byron was a mere 22 years old lad. The Hellespont swim, with its mix of literature, adventure, travel, bravery, eccentricity and romance, is an apt metaphor for Leigh Fermor’s life. Paddy Leigh Fermor was the Byron of his time. Both men had an idealised vision of Greece, were scholars and men of action, could endure harsh conditions, fought for Greek freedom, were recklessly courageous, liked to dress up and displayed a panache that impressed their Greek comrades. Like a good magician it was also a way to misdirect and conceal one’s true self.

What or who was the true Paddy Leigh Fermor?

Like Byron, Leigh Fermor appeared as a charismatic and assured figure. He was a sightseer, consuming travel, culture, and history for pleasure. He was an aristocrat moving in the social circles of his time. He was a gifted amateur scholar, speculating on literary and historical sources. Leigh Fermor, Byron’s own identity, is subject to textual distortion; it emerges from a piece of occasional prose in his books and is shaped by the claims of correspondence on a peculiarly fluid consciousness.

There is no hard and fast distinction to be drawn here between real and imagined, only a continuity of relative fictions that lie between memory and imagination as his biographer asserted. If there is a will to assert identity here, to disentangle fact and fiction, to give things as they really are and nail down the real Leigh Fermor then it is somewhere between the two. This is where we will find Paddy.

For many his death marked the passing of an extraordinary man: soldier, writer, adventurer, a charmer, a gallant romantic. As a writer he discovered a knack for drawing people out and for stringing history, language, and observation into narrative, and his timing was perfect. Paddy often indulged in florid displays of classical erudition. His learned digressions and serpentine style, his mannered mandarin gestures, even baroque prose, which Lawrence Durrell called truffled and dense with plumage, were influenced by the work of Charles Doughty and T.E. Lawrence. But one can’t compare him. I agree with the acclaimed writer Colin Thurbon who said, “There is, in the end, nobody like him. A famous raconteur and polymath. Generous, life-loving and good-hearted to a fault. Enormously good company, but touched by well-camouflaged insecurities. I would rank him very highly. ‘The finest travel writer of his generation’ is a fair assessment.”

As a child I didn’t really know who Paddy Leigh Fermor was other than this very cheerful and charismatic old man was kind, attentive, and took a boyish delight in everything you were doing. Only later on in adulthood was it clear to that Paddy was not only among the outstanding writers of his time but one of its most remarkable characters, a perfect hybrid of the man of action and the man of letters. Equally comfortable with princes and peasants, in caves or châteaux, he had amassed an enviable rich experience of places and people. “Quite the most enchanting maniac I’ve ever met,” pronounced Lawrence Durrell, and nearly everyone who’d crossed paths with him had, it seemed, come away similarly dazzled.

I am equally dazzled - more smitten in retrospect - for alas they don’t make men like Paddy any more. But every time I dip back into his books I think I discover a little bit more of who Paddy Leigh Fermor was because I find him some where between my memory and my imagination.

#essay#paddy leigh fermor#leigh fermor#joan raynor#joan leigh fermor#greece#crete#second world war#SOE#war#british army#history#general kreipe#stanley moss#literature#author#writer#travel#explorer#wanderlust#travel writing#europe#mani#peloponnese#kardamlyi#lord byron#ill met by moonmight#film#movie#personal

110 notes

·

View notes

Video

Tango is the only dance that can express the sadness and the joy of life in one breath.

- Carlos Gavito

639 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nothing behind me, everything ahead of me, as is ever so on the road.

- Jack Kerouac, On the Road

Take only memories, leave only tyre tracks.