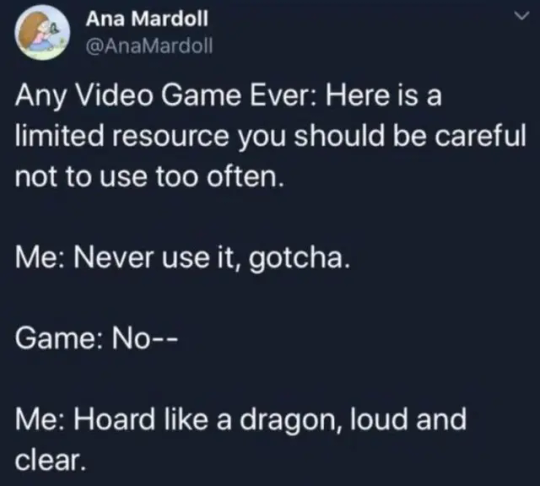

Text

Me consuming any form of media 🤣

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Vigil - 2x02

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

--- Come home.

--- I can`t.

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

Text ID:

I have love in me the likes of which you can scarcely imagine and rage the likes of which you would not believe. If I cannot satisfy the one, I will indulge the other.

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

There's people for whom "we're leaving in the morning" means "we ride at dawn motherfuckers, you can finish waking up and getting dressed in the car, we'll grab breakfast somewhere along the way", and there's people for whom it means "we'll get going somewhere before noon".

And then they get married.

93K notes

·

View notes

Text

I just discovered foodtimeline.org, which is exactly what it sounds like: centuries worth of information about FOOD. If you are writing something historical and you want a starting point for figuring out what people should be eating, this might be a good place?

195K notes

·

View notes

Video

TED LASSO SEASON 3 TEASER!

Season 3 premieres on 15th March 2023!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hit another milestone 105k on the petition! We should give it a bit more love today - please sign & share if you haven’t already.

Tagging other fandoms - let me know if there’s a petition we can sign in exchange. We’re all in this fight together!

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

For someone who is tired 100% of the time, I sure am bad at sleeping.

245K notes

·

View notes

Photo

trying to write a comment on an awesome fic is really hard

108K notes

·

View notes

Text

A technocrat’s paradise: how the supremacy of the algorithm is killing Netflix’s success

I resisted, for years, to get a Netflix subscription. I do not own a TV, and am not a regular television watcher: if I watch a TV show, it’s because I am looking for something specific, and decided to take time out of my day on televised, scripted content. When the second season of Warrior Nun was finally announced, I decided to get a Netflix subscription. Just for a month, and only because I enjoyed season 1 so much I felt I owed it to the show creators to watch it legally. (My general cost/benefit analysis for getting subscriptions, as a European non-regular television viewer watching shows that are all too often not legally watchable where I live, usually tends towards piracy.) So I signed up, entered my email address, billing information, and then was requested to pick three shows. This part, I hated. As a tumblr regular, I have a healthy suspicion towards algorithms, and this was no exception. Since I only signed up to watch one show, however, I did not need to have a functional algorithm: I already knew what I was looking for, after all. So I selected three mostly at random and signed up for a single month, after which I vowed to cancel the subscription. (Which I did.)

The morning of November 10 arrived, I watched, I loved, and I had no regrets about signing up: I got exactly what I came for. Then I rewatched for a month, never once watching anything else. It’s hard, being a viewer with such highly specific tastes, but Warrior Nun checked all my boxes in a way no other show had ever done, and I will stick with it for a very long time, in spite of its cancellation (whether or not that cancellation remains permanent).

In the wake of the Warrior Nun cancellation, however, I, like many of the fans, was left feeling confused: the show had spent three weeks in the top ten (two weeks more than season 1 did, which did get renewed) and had a record-breaking audience score on Rotten Tomatoes. The show’s renewal chances were defeated by data, the announcement seemed to suggest, but without any details, both fans and the showrunner were left hanging on the rationale behind the cancellation. And then, a more gnarly question: if the numbers weren’t good enough, why didn’t Netflix spend even a dime on promotion to begin with?

Nor was Warrior Nun the first, either: premature cancellations seem part and parcel of Netflix’s model, though never before had it seemed more puzzling and less transparent. Many viewers cried lesbophobia, since the shows getting cancelled most are ones featuring female characters with a female love interest. Though I refused to believe that the platform which hosted Orange Is The New Black would make a business decision based purely based on such a bias—maybe against good business sense, given the data we had—it was a hard conclusion to avoid. Nevertheless, I went searching for answers, and found a few pieces of information which offered enlightening insights. The first was this, an article on screenrant, decrying Netflix’s business model. Because my biggest question wasn’t why Warrior Nun didn’t get the numbers: though the thresholds for renewal were certainly not transparent, and the metrics hidden, I can understand a certain cost/benefit analysis comes into such a decision, especially since sci-fi shows are more expensive to produce with all that VFX, and I know Netflix shows become more expensive to produce after two seasons (though that is a part of Netflix’s own model to attract creatives: a strange self-own which may do nothing to attract creatives at all in the long term because the raise in fees becomes an incentive for Netflix to cancel, and the incentive for creatives to sign with them disappears). What I didn’t understand was why Netflix was setting its own shows up for failure by not even promoting them so they wouldn’t even get the chance to reach whatever nebulous numbers it would need to earn a renewal.

The article—which is worth a read—revealed that “Netflix generally depends on [its] algorithm rather than upon marketing” to drive viewers’ engagement with its original content. This is a strategy which distinguishes it from other streamers and networks, which do appear to invest in marketing for all of its original shows. The logic is simple: you watch a show on Netflix, the algorithm decides what your preferences are based on your viewing history, and suggests new content. Netflix’s main concern is to keep subscribers, and the strategy they have decided on to do that is to write an algorithm which keeps suggesting more and more content similar to everything you’ve watched up until then. It is a strategy which relies on quantity, not quality. Netflix has something for everyone, supposedly, and unlike a cable network, where you just change the channel if you don’t like what the network has on, on Netflix you can simply watch a different show and still be on Netflix. This strategy, however, means that, unlike cable network, which can only invest in shows for as many hours of the day as there are available, Netflix has no time limitation, and all of its original content is competing with each other for audience engagement. (Though these days also, somewhat hopefully, increasingly with other streamers.) Cable networks, who are competing with other cable networks, have an incentive to promote their original content as much as possible, because they need to make sure it’s more engaging than whatever other channels have on at the same time for ad revenue. Netflix has no such incentive, therefore their only incentive is to produce as much as possible without necessarily promoting anything: as long as there’s an algorithm which can suggest more content to an interested viewer, Netflix, so the theory goes, can succeed in retaining audiences, and therefore subscribers.

The appeal of relying solely on an algorithm to drive audience engagement is clear, of course: you only have to write a code once, whereas marketing campaigns require an investment for each season of each show you produce. Reliance on an algorithm appears like a technocrat’s dream. But it is a false utopia: having worked in pharma, I know what solid, reliable data looks like. But the idea that you could capture the human soul, the erratic movements of pop culture, and the whims of societal interest in a single piece of code really requires an astonishing amount of hubris. On top of that the algorithm is not an impersonal engagement production center: it is written by people, and people, as we know, are not objective, and have biases. The idea that reliance on an algorithm implies objectivity is a serious logical fallacy, but one managers who have to satisfy shareholders and investors with figures and data sheets may have a tough time grasping. Or at least, the managers at Netflix do.

The number of variables that determine a show’s success are mind-boggling even when you are a network doing old-fashioned marketing. A book published at the end of 2021 about Ukraine suddenly became a hit bestseller in 2022, but was written long before there was any hint of Putin’s plans to invade. The opposite can also happen: a show can look like it has all the ingredients for success in a particular cultural environment, and then the environment changes abruptly, and the show tanks. No one can control these externalities, of course, and everyone who works in media production understands this well enough. But when you add to that natural variability the whims of an algorithm which adds to all these external variables an additional heaping of internal variability, you end up with a media environment where creatives have even less control over what gets traction and what doesn’t, for the simple fact that the algorithm is determined by (1) a reductionist categorization of complex stories, (2) simplistic assumptions about what a particular viewer might want to see, (3) an insulting belief that if audiences have to choose between not watching anything and watching whatever Netflix suggests, they’ll watch what Netflix suggests without any additional information, and (4) an ever-revolving landscape of other media popular at the moment of release. All of these factors combined mean that a show’s popularity on Netflix, when Netflix does rely solely on its algorithm for it to be promoted, is so far beyond creatives’ control that there is no telling what’s going to happen with your show at any given point. A classic like Lord of The Rings, if it were produced by Netflix and relying on its algorithm, would probably have bombed because it was only noticed by people who are already inclined to watch fantasy.

This is the weakness of a technocratic model: the algorithm is written by a programmer who often knows little to nothing about the content, has to put complex stories into little boxes which naturally reduces the story and limits the many audiences that potentially could be reached. Managers make renewal decisions based on viewership figures which are based on this algorithm they themselves probably know little about, and then claim their decision is purely data driven. Which it is: but no one questions whether the data is representative of a show’s potential to begin with. Rather than cancelling shows for failing to perform according to a flawed algorithm neither creatives nor Netflix managers appear to understand, then, maybe Netflix should review its “data-driven” approach. There’s nothing wrong with having an algorithm to suggest different content to viewers who are already on Netflix, of course: social media everywhere does it, and with marked success. But it should not be the only thing which is relied upon to drive audience engagement, and certainly not for original Netflix content that it spends millions to produce every year. If it spends that much money on original content, it seems strange that Netflix is so stingy about basic marketing. Knowing the particular brand of arrogance and concomitant blind spots that come with being an industry disruptor, though, and a certain managerial naivety about the objectivity of “data”, I am not surprised that Netflix has now become so reliant on its algorithm for anything other than its flagship shows. Having an extensive data collection on audience engagement is an easy way to attract investors who don’t have a lot of literacy in the matter, after all, and do not have the critical thinking skills to question the relevance of that data to important business decisions like cancellation and renewal which, at the end of the day, also have a big human impact, both on creatives that sign with Netflix and the fans who sign up for Netflix’s original content.

More criticism may be leveled: the choice of which shows Netflix does choose to market, betrays a bias. Because aside from audience retention, Netflix also seeks to attract new subscribers, and this it means to do with its big flagship shows. Relying on an algorithm to promote your shows only works for people who are already on Netflix, after all: people who aren’t already on Netflix, or who only go on Netflix to watch specific, predefined content and do not use the algorithm to browse (see: yours truly), will never find these shows because there is nothing external to Netflix to promote this content. This approach means that a great number of potential viewers never get in touch with high-quality shows that they may very well want more of, but did not find in time to affect the metrics Netflix uses to impact its renewal decisions. So when Netflix does market a show to potential non-Netflix audiences, there is always a bias in the selection process, because only a few of its shows are flagships, which means many Netflix shows which have the potential to bring in new subscribers (as I did for Warrior Nun) never get the promotion to do exactly that. This is a tremendous waste of resources, and a wasted opportunity for Netflix to attract more subscribers.

They make up for some of that by means of social media activity, of course, and a reliance on fandom to make the noise for them. This is not a strategy specific to Netflix either, and it explains why, for example, as Warrior Nun showrunner Simon Barry revealed in an interview, Netflix initially wanted to have the season 2 post-credit scene cut: the story would have had a less satisfying ending, and a more heartbreaking one, without the post-credit scene, and in a day and age when negative emotion registers as engagement with human attention dealers like Netflix, encouraging a more wrenching ending to the show rather than a more fulfilling one are all too often labeled a strategic choice: fans take to social media to voice their heartbreak, engagement goes up, and Netflix gets fandom engagement while not giving anything back to these fans who are essentially promoting the show for them. I will not hide my disdain for the rage-is-engagement model, which, I repeat, is not unique to Netflix, but it’s certainly not sustainable, because generally people do not enjoy being heartbroken or enraged by shows for no good reason, and if you repeat this same strategy over and over again, people will figure out sooner or later that they’re being used and stop engaging. It’s a losing strategy in the long term.

Another curious strategy unique to Netflix: their model to order a show straight-to-series rather than, as traditional networks do, first order a pilot. This approach has quite a few downsides: it’s riskier, because you are less certain of the quality of what you’re going to get, and if you make a bad investment you’re spending more money on something without payoff than if you’d only ordered a pilot and filtered out the bad investments during an initial, private selection process. The disappointment of not getting picked up is also decidedly less: a pilot episode is only viewed by the network, and has no chance to disappoint a potential new fandom which is liable to become angry with you on cancellation; if you only order a pilot, the only disappointed party will be the creatives, who will have only spent time producing a pilot, rather than getting emotionally invested in an entire season. The additional step seems like a worthwhile one to heighten the chances of producing a good product, making a solid investment as a business, and lowering the emotional stakes for both creatives and potential fans.

Another point of critique is the “binge” model which is Netflix’s standard: the ideal Netflix viewer watches a show in one go, episode after episode, until the season is done, and they get a suggestion for watching something else. It’s a model to keep an audience hooked, but it’s not necessarily the model which will get original content the most engagement, nor is it sustainable. The separation between a television show and a film used to be that a TV show is a long story, told in many different episodes, that you can watch after a workday to relax, whereas a film is something you watch over the weekend for a special occasion; you have to take time out of your day to do this. The binge model assumes that you’re going to take time out of your day, and a lot of it. It also means that an eight or ten episode show, according to the Netflix strategy, only has about a month to get audience uptake (which is fairly little if you are a person with a long to-watch list and, you know, a life), contrary to weekly releases used by other streamers, where after each episode the show has the time to spread organically week by week via both fans and casual viewers, and a chance for a show to pick up new viewers every week. For people who prefer binge-watching, that is still possible: the content remains available after airing to do exactly that, on their own time, but the metrics which determine a renewal decision can be made within a more reasonable, humanly workable timeframe. It takes time for a hype to pick up speed, after all, especially when you refuse to apply basic marketing. In a hectic society which has only so many hours in the week to spend on entertainment, the binge model is a recipe for burnout. Add that to Netflix’s tendency to leave a story unfinished, and many casual viewers are already saying they refuse to watch a show if its story is not done yet because they refuse to get invested in something which is likely to get cancelled. This, then, creates a vicious cycle: the first and/or second season of a new show does not get the numbers because audiences increasingly refuse to engage with something unfinished, the show gets cancelled because the numbers are bad, strengthening the audience’s case for no longer engaging with new shows, and so on.

The bottom line is this: if you’re a company and you decide to invest in something, you want to know you get the most out of your investment. I do not know why Netflix decided to cancel Warrior Nun, but currently my belief is that either they’d made the decision to cancel before season 2 even aired due to the additional cost of renewal (and Netflix, as any company, needs to cut costs these days): a decision I might understand from a business perspective, but one which is extremely unfair to creators, and misses many chances for a solid, high-quality show to get as much audience reach as it possibly could. The second option is that Netflix managers truly do believe that a strict reliance on their algorithm for their original shows to be promoted should be enough for their content to make whatever metrics they determined the show needed to make for it to get renewed. I personally maintain that Warrior Nun did astonishingly well, given the promotion it was given, and while a “data-driven” model may seem attractive from a business perspective, it is defective, and the consequences of a blind adherence to it does affect real people. Creatives who sign with Netflix like to know that they won’t invest their efforts into something they will never be able to bring to a good end due to an arbitrary metric they have no control over which says nothing at all about a show’s ability to engage an audience, especially when the show may well have done better on a different streamer, which does invest in traditional marketing for all their original content. In a media landscape that is constantly in flux, creatives like to know that what little can be done to contribute to a show’s success, will be done, and Netflix’s adherence to its algorithm means that entire swaths of original Netflix shows are essentially being thrown into the jungle left to fend for themselves (a jungle made more hostile due to Netflix’s own strategy)—hardly an attractive proposition when there are networks who do give shows that additional support in the form of marketing. What Netflix appears to be doing with its current model, based on a flawed algorithm, is throwing eye-watering amounts of money away, disappointing both fans and creatives, and chasing away potential subscribers. Given the financial uncertainty of the times, and Netflix’s recent losses, one might wonder at which point investors decide that Netflix’s approach is wasting money, and it might be best to invest in a streamer which understands why marketing, rather than an edgy tech-approach, still works better at bringing in new and retaining old audiences for all of its original content.

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reads a fanfic: that was good, I'll leave a kudos

AO3: You have already left kudos here

Me:

57K notes

·

View notes

Text

super simple low-effort ao3 summary methods that are 1000% better and 1000% less annoying than just saying you suck at summaries:

copypaste the first few lines of the fic. u already wrote ‘em. let ‘em be their own damn hook

if ur feeling fancy & don’t mind showing ur hand a bit, copypaste the first few lines of the fic that u feel are esp. Important or Interesting - the ones where u first start getting into the real meat of things

state the main tropes! theyre probably already in ur tags - just say them again - maybe as a full sentence if ur feelin fancy. or with a joke if ur feelin Extra fancy

ask a question. pose a hypothetical. eg what happens if u take [character] and put them in [situation]?

make an equation. [character] + [thing] = [outcome]

just write like a one-sentence summary of what the fuck is going down. just one (1) sentence. doesnt matter if it doesn’t cover every important aspect. or if it sounds bland. any summary sentence is gonna be miles better than “idk i suck at summaries”

just…explain the fic like u would to a friend? it doesnt have to be a polished back of the book blurb. it can just be “[pairing] coffee shop au, but like, still with murder, and also i made everyone trans. enjoy”

just stick a meme in there

honestly who cares

just put literally anything but a self deprecating comment in there & ur golden

47K notes

·

View notes

Photo

New! Josie Gleave brings us a guide to sexual grooming that can protect you and your friends from online abusers.

3K notes

·

View notes