Text

‘Review: Hive City Legacy’ by Ummi Hoque

After 2018’s sell-out run, Hive City Legacy returns once again at the Roundhouse to activate, pollinate and liberate. Nine femmes of colour were selected from 250 applicants to collaborate with Australian collective ‘Hot Brown Honey’ to unapologetically strike back to the societal marginalisation of femmes of colour. Director Lisa Fa’alafi put together a marvellous fusion of hip-hop, breakdance, mime, aerial acrobatics, spoken word and plenty of twerking.

The hour-long show consists of snapshots of the daily struggles femmes of colour encounter in ordinary settings such as a morning commute on the Tube or an office party. Whether it’s a fetishizing gaze from a white man or the ignorant, offensive comments like “is that your hair... or did it get electrocuted?” Hive City Legacy does not downplay the rawness and realness of their individual experiences.

There is something quite liberating and empowering to see a show where every element of production and the cast is a femme of colour. To be given a platform, a space, a stage to share their story but also as an audience member to relate to their stories. I can assure you that Hive City Legacy is not afraid to absorb all that space and project their voices loud and clear. In fact, I think the show deserves to be on a bigger scale. Each performer exudes with infectious energy, bringing out a mixture of emotions from the audience from various scenes. There are moments where you’ll have a lump in your throat but there are moments where you’ll cackle with laughter. The one that got me was ‘What do you know about rhythm Sharon?’ A cherry on the cake was Krystal Dockery’s surprise appearance of nipple tassels on her arsecheeks, also wittily known as ‘assels’. Love that.

Taking my seat in the compact studio space was accompanied by upbeat, hip-hop jams, which seamlessly set the mood for the play. A beehive serves as a symbol for femme empowerment and costume designer, Sabrina Henry, and set designer, Emily Harwood, most certainly incorporate the running theme of a beehive through the individualistic costume, the large LED sign placed high up on the wall and the hexagonal block structure of the set. Although the cast reflect a beehive collective, particularly through their punchy, fierce choreography, they simultaneously tell stories of individual lived experiences as femmes of colour. What I love about this show is that it explores intersectional black femme identity and utterly defies the homogenization of black and brown women.

Hive City Legacy quite literally invites the audience to dance with them on stage, twerking and skanking to great music and to end on a celebratory note. No play has managed to get me out of my seat ever so I applaud Hive City Legacy for being the first.

The play does not have a consistent narrative which left me confused at times as the sporadic structure made it difficult to know when a new scene was introduced. Nevertheless, the message still comes across clearly and it successfully challenges patriarchy, institutionalised racism, chauvinism and fetishizing women of colour. But it also uplifts and celebrates the power of melanin and how individual stories can come together to create a collective or in this case a beehive. To activate, pollinate and liberate.

I recently read this quote which I think perfectly relates to Hive City Legacy: ‘If you’re not uncomfortable then you’re not listening’. This is an integral purpose of the play, particularly for white and non-femme audience members to actively listen to the stories from powerful femmes of colour and to feel uncomfortable.

Ummi Hoque is an 18 year old theatre enthusiast and aspiring writer

@ummihoque

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘A reformation of drama in schools: Young people need to be exposed to backstage theatre roles’ by Omolade Ojo

You are in the audience for the most revered, acclaimed play in London. It has received praise from publications, social media platforms and your friends have been biting your ear off to watch. It’s started off great and you are understanding just why the hype was so big. Then the lights flicker, the sound distorts, the microphones cut out and the back drop falls down. Everyone is confused and suddenly, your experience has degraded about 99% - the story is lost and the moment gone.

The work that happens backstage is the heart and soul of every show. If an actor is said to be the icing on the cake, what goes on behind the scenes is the ingredients and the cherry on top. The roles that exist backstage are incredibly important yet this not widely taught in everyday schools. There are a lot of young people that love theatre/ drama who do not see themselves as actors yet are not aware of the multitude of roles available to them. Before I started exploring this industry, my understanding of theatre was limited to once-a-week drama classes that lasted 50 minutes – not enough to explore a text and do a practical lesson and much less than the time and energy schools place into Maths, English and the Sciences. In those drama lessons, everyone got to be an actor, director and occasionally a writer. Those were the roles we had seen on TV and on stage and those were the roles that were actively encouraged. Little did we know that our knowledge was only of a minute section of the industry.

The world of stage management, lightning, sound, costume, makeup, props (and so much more) are vital to the running of any show. They transform the way a show is understood and interpreted by the audience, adding depth and insight. Schools and their respective boards of Education must do more to actively encourage creative routes as they do the more ‘traditional’ ones. Young people need to be made aware of all the roles in theatre otherwise it is a missed opportunity to engage the next generation of talented youth of diverse backgrounds who offer fresh perspectives. The spotlight needs to be shifted from those we can see on stage, to the work that happens off stage as they are equally important. Schemes like the National Theatres’ Young Technicians course, the Theatre Craft careers fair and the increasing number of apprenticeships available are a huge step in the right direction.

My true appreciation for the work that happens backstage begun 10 weeks ago when I started a Production Arts course. It has given me a new understanding and gratitude of the way I see theatre. Now when I see a one man show, I know there were numerous amounts of people ensuring the smooth run of the production.

If Schools’ help assist those interested in finding their perfect role in theatre, educating them about all the roles available, we will continue to see passionate and excited young people in this industry - even if they aren’t underneath the spotlight.

Omolade Ojo is a Writer from London with a passion for food, theatre and books.

Twitter: @omoeats // Blog: www.omoeats.wordpress.com

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘The Canary and the Crow’s Daniel Ward: “There’s a lot of gig theatre out there now but Middle Child were one of the first companies that championed it”’ by Lizzie Akita

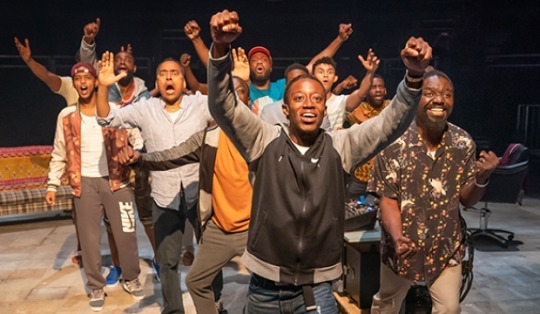

Hull-based theatre company Middle Child are making a name for themselves as creators of gig theatre. Theatre that combines original live music with new writing; it’s an immersive experience that many may not have seen before. Their latest offering is ‘The Canary and the Crow’ which made its debut at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival this year. Before one of its evening performances, I met with writer and lead performer, Daniel Ward, to discuss the show and the exciting space that gig theatre currently occupies.

In many theatres that you enter, the stage is concealed by a curtain; it’s a decorative barrier which keeps the audience at a distance. But when you take your seat at the Roundabout @ Summerhall to see ‘The Canary and the Crow’, there’s a different kind of atmosphere. Prez 96 who plays ‘The Cage’, hypes up the crowd in the in-the-round theatre, dancing and getting the audience to chant along just as an act would do ahead of a gig. It’s inviting, liberating and charges you up for the evening ahead.

“Gig theatre is quite an exciting space to work in because nobody really understands what it is. I think people understand if you’re going to go and see musical theatre what it is. If you go see a traditional play, or a comedy gig or a music gig, people kind of inherently understand what it is. It’s an exciting space to work in because no one has the answers.”

In Ward’s semi-autobiographical piece, directed by Paul Smith, a black ten-year-old boy secures a scholarship to a prestigious private school. The boy, known as ‘The Bird’ and played by Ward, is thrust into a world where the majority of the students and teachers are white and he is seen as an ‘other’.

“I started writing to music with the idea of two conflicting [types of] music in mind. The classical cultural music verses the grime, jungle hip hop that we used to listen to.” Ward explains. The conflicting music styles described captures this tension where The Bird is at odds and out of step with the majority. As he attempts to adjust, there is a cost as he starts to lose touch with those he grew up with. “In the play, there are the lessons which make up the piece and there are the tracks. Every time I wrote a lesson, I wrote it to a musical track.”

When Middle Child agreed to take on the show, shaping the production and the music was a collaborative process. “Sometimes I could play the music or give an impression of what kind of feel the track should have and then James Brewer [co-composer], would go okay and make something based on that feel or Laurie [actor-musician] may pick up a cello and Nigel [co-composer aka Prez 96] would say I think I get this beat. It was a real ensemble effort where we kept trying things out. It was a lot of fun and trial and error. I’m not trained in music, I can only say it feels like this and then they understood it, that’s all they needed.”

Ward’s first experience of gig theatre was four years ago at the Edinburgh Fringe when he saw ‘Weekend Rockstars’ created by Luke Barnes and Middle Child. “It was on at midnight and it was rock music. They were playing their guitars and were angry, talking about how there was nothing to do in their town. But at the weekend, they’d grab a pint and be able to go out and be rockstars. It wasn’t my experience, but I knew this was how I wanted to tell my story.”

“There’s a lot of gig theatre out there now but Middle Child were one of the first companies that championed it. A music gig appeals to broader audiences while theatre doesn’t. Middle Child’s goal is to look at the elements of a comedy or a music gig and see how we can incorporate this to bring new audiences and younger audiences into the theatre.”

In the opening of the show, Ward takes us back to the experience which inspired its creation. A black guest speaker specifically requests to talk to the BAME (black, asian and minority ethnic) students at Ward’s drama school. A friend of the speaker, also a black actor, had suffered a breakdown and an identity crisis which stemmed from his experience at drama school years before. The speaker was worried that the students in the room were at risk of having something similar happen to them.

The person in question is British actor David Harewood. Originally from Birmingham, Harewood trained at RADA in London where he was one of the very few students from a minority background. He has spoken publicly about his identity crisis and mental health breakdown, most recently in the BBC documentary ‘Psychosis and Me’. This experience planted the seed for ‘The Canary and The Crow’. “When that conversation happened, I was thinking about it and I wanted to write something that acknowledged this weird feeling that I couldn’t quite articulate about my educational experience, both at drama school and at Wilson’s [Ward’s secondary school]. But I didn’t know what it was.”

This weird feeling which is explored in the play is the idea of becoming an ‘acceptable black’. This is the notion that when in the minority, you leave your cultural identity behind to become tolerable to the majority. This feeling of not belonging is one which Ward is more than familiar with. Ward comes from a working-class background and a single parent family household and went to a grammar school where he was surrounded by people who were different to him. “I was always aware that people were very affluent. Wallington is a catchment area of private schools and grammar schools, all in really close proximity to each other. It’s a really nice area and I guess there’s just a lot of wealth around.”

This experience is not just unique to Harewood or Ward, but can be said of anyone who finds themselves in a setting where a certain characteristic or feature places them in the minority. Do you talk a certain way? Is your hair ‘neat’? This all determines whether the majority will warm to you or not. Through the lens of a young boy, Ward touches on the daily confrontations you are likely to face when you don’t quite belong with painful accuracy.

At various points in the play, Ward returns to this analogy where a comparison is drawn between the canary and the crow. The canary sings a pleasing melody, representing that which is ‘acceptable’ and the screeching crow irritates and has a harder time fitting in. This idea originates from fables and can be found in French and Turkish literature, Hebrew texts and even in native American folk tales. “Fables are magical and exist for a reason. Dehumanising the story allows people to have their own interpretations of what it means to them. I didn’t want it to be preachy and I didn’t want it to be definitive. But people should be able to come away and form their own ideas and opinions.”

Since Ward first finished writing the show, it has travelled a long road before eventually being picked up. “It was a long process of getting rejected, being told that it didn’t have an audience and that it would need to broaden its target demographic. And I thought nahh don’t think so.” The flood of positive responses that the show has already received from people from various backgrounds being able to connect with Ward’s story suggests that he was right to stick to his guns. Do you have any advice for aspiring writers out there? “I would say just get to the end of your play and send it out, get some feedback and just persevere. All it takes is one, one person to say that this is good and I believe in it, to become something and for it do well. Then all the other rejections don’t matter. It’s an industry of rejection and people have to be prepared to deal with that”.

Following its run at the Paines Plough Roundabout @ Summerhall, The Canary and The Crow will embark on a UK tour starting on 7 Sep 2019 at the time of writing.

Photo Credits: © The Other Richard

Lizzie Akita

Website: https://myfairtheatregoer.com/ , Theatre Reviews and Why We Tell The Story interviews // Twitter: @myfairtheatre // Instagram: @myfairtheatregoer

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘Review: Hive City Legacy’ by Jasmine A. Samura

Farrell Cox flashes a coy grin, as she attempts to literally and figuratively catch the spotlight. Opening the show, she single-handedly captivates the audience with her mime-like performance, usingevery inch of the hive-shaped set to tell her story, as she limberly scales the multi-levelled city designed to reflect London’s skyline. Sharaya J’s Shut It Down blasts as Farrell looks to stage left. Therein enters Hive City Legacy. Seven multi-talented young femmes of colour who ask you to lend them your ears for an hour of pure entertainment.

A year after its initial debut, Hive City Legacy is back. It’s bigger. It’s louder. It hits closer to home. And it comes with a brand new wardrobe! The insatiable femmes of Hive City Legacy return to The Roundhouse with their new and improved performance addressing the femme of colour experience in all its unfiltered glory.

The thought-provoking performance, written and directed by Lisa Fa’alafi and Yami Löfvenberg of the critically acclaimed Hot Brown Honey, brings a refreshed perspective on the everyday inward thoughts, experiences and emotions that many femmes of colour know so well and have grown accustomed to. There is something comforting about their ability to address topics that so many have encountered, but may not have acknowledged.

The writing fluctuates between hard-hitting subjects and genuine side-clutching gags, scenes softened with humour or dragged into the harsh and unforgiving spotlight. The whisper scene is especially gripping; multiple voices in hushed tones cascade from behind the set, crescendoing into a flurry of offense. Quotes all too familiar to femmes of colour; the good ol' “I’ve never been with a black girl before, “want some white chocolate?” or “want mixed race babies?” and lest we forget the racial slurs, sprinkled with a dash of misogyny. This, counteracted with a begrudging recital of “God Save The Queen” effectively demonstrates Fa’alafi and Löfvenberg’s ability to immersive their audience, leaving us second-guessing, It can be difficult to balance the two and can easily leave an audience emotionally spent, however, Hive City Legacy execute this with clever quips, gut-wrenching monologues and some of the rawest chemistry Roundhouse’s Sackler Space has seen.

Nothing and no one is safe. These femmes don’t shy away from the taboo, whether approached and softened with humour or dragged into the harsh and unforgiving spotlight.

The septet each bring their own creative areas of expertise to the stage. The aerial performance is especially enticing. Rebecca Solomon effortlessly scales the rope, smoothly cutting shapes in the air, with the ease and grace so many of could only dream of with both feet on the floor. Shakaiah is picturesque – her voguing, paired with her traditional Maori poi performance are refreshing to see. Krystal Dockery is beauty, she is grace with her gimmicky numbers and her hypnotic twerking skills (exposing most of the audience to their first encounter with ‘assels’ – tassels attached to the buttocks) leave you wishing your two left feet could be more forgiving.

‘We’re allowing our grandmothers to be ingested. Digested’, pleads Dorcas Stevens as Farrell Cox struggles with an elongated English flag. The commentary on the BAME-British experience is loud. It is unapologetic and it doesn’t care who hears about the ‘hours spent in Kentish Town library learning your history’ or encounters with white men ‘drenched in sweat and privilege…who want me for dinner during their evening commute.’

Hive City Legacy is an examination and a breakdown of society’s attitude towards women of colour and an invitation into their makeshift fortresses in a form that is digestible for all—even if the pill itself is hard to swallow. ‘Who writes this stuff? Probably some black artist who won’t get credit, anyway!’

Noteworthy Quotes:

‘You didn’t 4C that coming!’

‘I don’t remember who I was before arriving.’

‘Dripping in culture…pink and purple lights melting into her brown skin.’

‘I am not a fetish. I am not a shape, a style or fit into any box.’

‘Am I the Rosa Parks of theatre stalls?’

Jasmine A. Samura is a London-based writer of words and aspiring music journalist

Insta: ServeTheServants95 / Blog: themusicmosaic.blogspot.com

0 notes

Text

‘“It feels like there are no barriers”: David Webber and Maynard Eziashi on life in the Barber Shop Chronicles’ by Jenna Mahale

Inua Ellams’ Barber Shop Chronicles is a new kind of theatre. This theatre scoffs at the stuffiness of the old guard. It flings its arms wide open to newer audiences, younger audiences, blacker audiences. Between sound bites of Skepta and J Hus, Barber Shop Chronicles takes us on a whistle-stop tour through Lagos, Nigeria, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Ghana, Uganda, and Peckham; we gain a piercing insight into the inner lives of black men, and the importance of community hubs in shaping them. As such, the production holds a very special place in the hearts of its actors, many of whom are thrilled at the opportunity to explore their culture and identity in a setting as vibrant and lovingly-crafted as the one Bijan Sheibani has created for them.

David Webber and Maynard Eziashi are two such actors. As the gloom of the early evening pushed through the windows, I sat down with them pre-performance in the café of the Roundhouse to talk about their experiences with the show and its strikingly original material.

Tell me a bit about your characters.

David Webber: I play Abram, I play Ohene, and I play Sizwe. Abram is a barber in Ghana, Accra, and he has a really sweet scene with a young man who is about to have a baby. It's one of the quieter, more intimate scenes. Then there’s Ohene, who is very opinionated and sometimes a bit loud. He's a Ghanian again, and he's in the London scenes. I also play Sizwe, who's an older gentleman. He's Zimbabwean, but he has scene in London towards the end. He's a bit nostalgic, always looking back.

Maynard Eziashi: I play three characters. There’s Musa, a Nigerian man from the Hausa tribe, who is a linguist. He's just come back from Mexico, where he's written a dictionary translating Swahili to Spanish. I also play Mensah, who is a Ghanian man who's very interested in football and getting his hair cut. And I also play Andile, who is a South African barber who is fulfilling his role as a kind of therapist to Simphiwe, who comes into his store slightly agitated: it's to do with the relationship that he has with his father.

Do you have any favourites?

Maynard Eziashi: Andile is probably my favourite character. I like the fact he's a very knowledgeable elder gentleman. He listens to people, but he doesn't judge, and hands out little nuggets of advice that people can choose to take or not.

David Webber: It's very hard to pick a favourite. It's like asking, 'Which is your favourite child?' I love them all, I love them equally, but I would say I feel a lot of love for Sizwe. I think the only time he gets to speak to people is when he goes into the barber shop. I find that very poignant.

Lots of critics have praised Barber Shop Chronicles for itsdiscussion black masculinity. Have your conceptions of masculinity changed at all since doing the show?

David Webber:It's not necessarily changed how I see masculinity, but it's maybe reaffirmed some things in a wonderful way. There are 33 black characters on stage, played by 12 of us. I'm really happy that the audience gets to see such a range of African masculinity, and hopefully it will mean people find it more difficult to put us into boxes. I think this show is a good way of looking at our culture and seeing it in a broad and diverse sense.

Maynard Eziashi: Although we're dealing with men's barbers, I think a lot of the topics are universal. They're about identity, they're about belonging, they're about dating! I think those things extend to everyone, really.

Obviously, the ethnic make-up of the cast is quite revolutionary for a show of this size. Tell me a bit about what it’s been like to work in such a large cast of black men.

Maynard Eziashi: One of the things that it's meant is that I no longer have to censor myself, or put myself through a filter. Because we all have a kind of shared experience. So if I come in and say, 'Oh, someone in a shop looked at me funny', people aren't going to turn around and say: 'Were you just imagining that though?' or, 'Are you sure that really happened? Maybe they were just having a bad day!' Instead, there is that understanding. It's wonderful to be in a company where we can share stories and experiences. It feels like there are no barriers.

What was the audition process like?

David Webber: I was called in to meet Bijan [Sheibani], and Inua [Ellams] and the casting director at the time at the National Theatre for a read-through. To be perfectly honest, I can't remember what characters I read. All I remember is that we had a big laugh about barber shops and stories, and how I'd share stories with my barber. I've got a Jamaican barber in Manchester where I'm from, who’s full of stories, and I've had a barber in London for a few years now, called Ninjaman. He'll be cutting your hair and then go off to the bookies in the middle of it, and leave you with half a haircut so you can’t leave. You meet characters like that over the years. We just laughed about our barbershop stories, and it didn't really feel like an audition, it just felt like sharing stories with friends.

How does this role compare to the other characters you’ve played?

Maynard Eziashi: It's probably not so much the role, but this story is quite different from a lot of the other stories that I've helped portray before. It's a story that shows you 33 different characters, none of them stereotypes, and they all have the same hopes, dreams, and fears, as all of us. It kind of shows a normality, but also the breadth of character. Because we often tend to get put in a box where we can only be one sort of person, which tends to be angry, violent, or highly sexual. In other shows I've been in, that breadth hasn't been there. Although the character I've played will have an arc, because you have many characters here, you can show much more.

David Webber: A lot of the things I've seen about black men have focused on quite negative things. And they're sometimes the plays or stories that get highlighted. The plays that are often produced feature black men in crisis, black men leaving their kids, black men stabbing each other, murdering each other, violence, that kind of thing. And that's very sensational, and those shows often make headlines. This show is not about that. I think that's a very powerful thing.

What would you like people to take away from the show?

David Webber:I'd like people to take away the fact that sometimes the differences between the races are actually smaller than the similarities. We have many, many things in common as human beings. I think that's why the show works for everybody. It's a celebration and an affirmation of humanity.

Maynard Eziashi: I suppose I'd like them to walk away, and perhaps question their notions of blackness. To look inside, and think, 'Do I make certain assumptions? Do I judge unfairly? How can I rectify and change that?' That's what I want.

Jenna Mahale is a freelance journalist and editor from London

Twitter: @jennamahale / Contently: https://jennamahale.contently.com/

0 notes

Text

‘Is commissioning work by Black artists enough to make Black audiences feel welcome in predominantly ‘white’ theatre spaces?’ by Shanaé Chisholm

Before I became explicitly aware of my own positioning in society, going to the theatre was a treat. It was an experience that made me feel special. One where class structures and racial difference didn’t appear to matter, as essentially, we, the audience, were simply watching a play. Yet, once the relationship between the colour of my skin and the way I was treated emerged, I realised that certain demographics are made to feel more comfortable than others. I learnt that the discriminative hierarchies of society didn’t disappear in the theatre environment.

To finishing reading this piece, go to the Roundhouse website, here: https://www.roundhouse.org.uk/blog/2019/10/is-commissioning-work-by-black-artists-enough-to-make-black-audiences-feel-welcome-in-predominantly-white-theatre-spaces/

Shanaé Chisholm is a Theatre Critic, recent Goldsmiths Graduate, and Development Operations Assistant at the National Theatre.

Twitter @rihmariec // Blog: ‘Keeping It Naé’ - (found at) naewrites.wordpress.com

0 notes

Text

‘The value of black and PoC-led theatre festivals and seasons’ by Tenelle Ottley-Matthew

The British theatre industry is still marginalising its non-white talent and failing to give them the opportunities and recognition they deserve. This marginalisation has prompted some artists to take matters into their own hands, by forming collectives and programming festivals and seasons created with artists and theatre lovers of colour in mind, for example.

Take This Is Black, a festival curated by Steven Kavuma that is running until 25 August at Bunker Theatre. For and by black artists, This Is Black consists of four new plays and an accompanying art exhibition curated by Sophia Tassew. Kavuma’s motivation for creating This Is Black is fairly simple: to give black writers and creatives a platform to tell their own stories. A need, that he says, felt even more important due to the lack of inclusion and visibility that has been commonly experienced by non-white artists at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. The issues surrounding exclusion, lack of visibility and isolation at Edinburgh Festival Fringe have been well documented in recent years. As non-white people living in the UK, most of us are too familiar with such feelings as a result of being in predominantly white spaces.

To finishing reading this piece, go to the Roundhouse website, here:

https://www.roundhouse.org.uk/blog/2019/10/the-value-of-black-and-poc-led-theatre-festivals-and-seasons/

Tenelle Ottley-Matthew is a writer from London with bylines in Huck, Hal-dem, Pride magazine and more. She will soon be working in book publishing.

Twitter: @misstenelle / Blog: tenelleottleymatthew.com

0 notes

Text

An interview with Barber Shop Chronicles cast member Elmi Rashid Elmi by Shanaé Chisholm

Barber Shop Chronicles dismantles the hegemonic construction of Black masculinity, allowing its definition to include vulnerability, political intelligence and musical performance. Taking us on a journey across Africa and back to London again, Barber Shop Chronicles explores themes of fatherhood, identity and relationships. Yet, at its core, is the tale of collectivity. Ingeniously framed by a Chelsea vs Barcelona match, Barber Shop Chronicles sheds light on an international community of Black men, who unknowingly share the same experiences and the same joke!

Elmi Rashid Elmi joins me for an interview about his experience as a member of the cast and his career so far.

What role does your character Ethan, play in the narrative?

He’s an 18-year-old boy, turning 18 actually, and he’s struggling with what it is to be a man, a strong Black man. He’s mixed race, never really knew his father like that, he lives with his mum, he’s an actor and he’s just trying to find himself. We’ve all be there at some point; I’ve been their personally, which is why it’s a big pleasure for me to be able do this role.

How has your experience been so far with the cast and rehearsals, and in general?

It’s been great, it’s been fantastic. Most days it feels like I’m not even working. You know, you come, you’re vibesing with people that you get along with. There’s no awkwardness, no weirdness, people that you identify with, 12 black brothers that all have relatable stories. You come from the same place, somehow, anyhow. It’s been a great experience. Especially for me. I just finished university about three months ago. I did acting, I did that for three years at the London College of Music. This was one of my first jobs, after graduating. To have this as one of my first jobs, it’s been amazing, it’s a blessing and it’s been great everyday ever since.

What was your journey into this role? Were you always going to be an actor?

See, I’m East African, I’m Somalian and in my culture, being an actor of the creative arts as a whole, is not really encouraged. After the civil war that happened in Somalia, people migrated here in the early 90s and first generation parents here were just grinding, and it was all about getting secure jobs and stuff like that. So, kids never got encouraged to do something that was not…well they thought wasn’t stable or was a bit risky.

I realised I wanted to act when I came back from Somalia at the age of 16. I didn’t have enough time to prove myself academically, I was just lost for thought, I was like what can I do, what should I do and I always was into acting and I used to do a bit of acting back home to get by. I came here and I was like what should I do, what should I do? So I ended up doing a three-week Prince’s Trust course. That led me to the Bristol Old Vic Young Comedy Theatre, I did my first show there.

What was your first show?

It was a little devised ensemble piece, called Everyone’s Scared. We did that over a week, it was fun, it was great, it was like ‘wow, this is for me, this is what I like’. At the time, I was struggling to learn English again as well, because I was away for ten years, so I forgot how to speak it.

I decided to move to London about six years ago. I came here, I applied for drama schools and stuff, and it’s been a rough journey. Went back to Bristol, because I’m the oldest in my family as well. So it was a lot of back and forth but I never lost hope because it was something I was really fixated on.

I ended up going to the London College of Music. Did that for three years and luckily after my final production Sing Yer Heart Out For the Ladsby Roy Williams, I managed to get a few agents come in and I received two offers. Ever since, it’s been great. I ended up getting cast in a Hollywood film that’s coming out next year. After that, I ended up getting a role in a BBC TV show, did one episode of that, and then just a week later, I landed the role in Barber Shop Chronicles. So that happened over the last three months, when I graduated and it’s just been crazy, it’s been mad, and here I am.

Do you say yes to certain shows based on its theme/genre/message? is there work that you want to do in particular?

As an artist, you gotta know what type of work you wanna do, and how you wanna paint yourself and what kinda career you wanna have. So you have to be conscious about these things and be aware of it. Especially in the beginning when you’re new to the game, you’re not really in a position to be picky and it’s tough. You might get like one opportunity, which is good, but it’s not necessarily what you imagined, and if you turn it down, then it’s a tough one, you don’t know when the next opportunity might come.

If a big opportunity comes, where it’s a massive opportunity for me and my career, but it’s a role I don’t really wanna do, personally, I think I’d just turn it down. God is with me, and if I wanna do this, I wanna do it not losing what I stand for, who I am, my values. I represent me, I represent my family, young people, I represent the Somali people, the East Africans. So, I want people to know that they can do whatever they wanna do, without having to change who they are and that’s the point. What is the point of doing something that you’ve been meaning to do, or you wanted to do for a long time, if you’re gonna lose yourself in it, and that’s how I see it. For that reason, I am a bit picky about what I do.

What can we look forward to seeing you do next?

I’m writing a play right now, it’s just telling a Somali story that I’ve always wanted to tell and I have the opportunity, but still early days, that’s still in the works, I can’t really say much on it. The next thing, that I’ll probably be seen in, are those two things that I filmed about a month ago. The Hollywood film, which will be out next year November time, and the BBC thing which will be out early next year, hopefully. Hopefully that will be the next stuff that I’ll be in, and hopefully more, pray for me and I’ll pray for you.

Although the London performances of Barber Shop Chronicles has ended, you can still catch performances across the UK until the 23rdNovember!

Shanaé Chisholm is a Theatre Critic, recent Goldsmiths Graduate, and Development Operations Assistant at the National Theatre.

Twitter @rihmariec // Blog: ‘Keeping It Naé’ - (found at) naewrites.wordpress.com

0 notes

Text

“There's no one way to be a femme of colour” - An Interview with Hive City Legacy by Amal Abdi

Hive City Legacy is a collective of nine femmes of colour. Their show is an electric exploration about what it means to be a woman of colour living in Britain today. It travels through microaggressions at office parties, harassment on the tube, mental health issues and so much more. It does all of this through multidisciplinary art forms. You never really know what kind of show you’re watching. But this format breaking it what makes it so exciting. Even with the surprising elements, the core message is clear. All these women are inspiring and empowering in their separate ways.

From the show, it is clear that the key message is that femmes of colour are not a monolith. As cast member Aminita Francis puts it, “There's no one way to be a femme of colour, there isn't a mould you have to fit into. There isn't a stereotype that you have to fulfil. You can literally be anything you want to be.”

If there is one thing that Hive City Legacy shows us it is that “You can literally be anything you want to be.” All the performers use their skills in such different ways. While Elsabet Yonas has a background in hip-hop dance, Rebecca Soloman and Farrell Cox are aerialist just as Dorcas A. Stevens performs a spoken word monologue in the show.

Aminita continues “Everyone [in the cast] is so different. And also so talented in completely different ways. I absolutely wish as a young person, I could have seen something like this. Not just femmes of colour, everybody should take that away from the show”

While watching the show, you feel the presence of the performer's lives influencing the show. Actress Krystal Dockery who performers a burlesque-like segment notes that the casting was both long and gratifying. She says of the audition process; “we had to do different random things. We had to give ourselves super names and send in videos. We had to lip-sync for our lives. A speed dating of everything we could do. I’ve never been in an audition that was so supportive. It was wicked. And everyone was smiling. Everyone was rooting for the other person.”

For Hive City Legacy, it makes total sense that the performance is influenced so much by the performers. As Krystal explains “As an actor, you spend so much time exploring other characters and you rarely get to explore yourself.”

The performers are even able to express themselves in their costumes. As the cast explains, their costume designer Sabrina Henry devised their outfits after asking them to send her a picture of them in their favourite outfit. As a result, Krystal can wear a bright pink skirt while Shakaiah Perez can show her tattoos which highlight her Polynesian ancestry. The set design itself, designed by Emily Harwood is inspired by director Lisa Fa’alafi tattoos and the London tube. Importantly, everybody that has taken part in devising this has been a woman or a woman of colour.

Throughout the show, a point is made to make the audience feel uncomfortable. As Shakaiah Perez puts “We do a lot of things that could make a lot of people who aren't people of colour uncomfortable.

When white people experience life, they don't get to see the things we see as people of colour. And when they are faced with nine femmes of colour in front of them going at it and doing it full-on it can be quite intimidating but I think that that is kind of the point. You are only uncomfortable for an hour in the show, we are uncomfortable for the rest of our lives."

In one segment, Aminita monologues about being the only black person in a theatre full of white audience members. She confidently says “I am the Rosa Parks of theatre stalls”. The cast of Hive City Legacy are aware of the cultural barriers people of colour feel towards the theatre.

As Aminita explains Hive City Legacy is a show made with women of colour in mind. She says “There’s plenty of times in the show when we make reference to things that if you’re not people of colour, you might not get it. And that’s not my fault. We are catering to the audience that we want to cater for.”

Koko Brown is defiant that Hive City Legacy is a safe space for women of colour. She speaks clearly to women of colour; “we want black brown women to come in. Even if you’re nervous and you’ve never been to a show before, DM me and I’ll tell you what to expect. If you can’t afford a ticket, and I’ll buy you one. By saying you are wanted in this room not just come see this show.” Her welcoming audience members into the theatre is in keeping with the show which invites the audience to dance on stage at the end of each performance.

Hive City Legacy is doing important work and the cast knows this. As Shakaiah expresses “It’s like we are doing theatrical activism. We talk about so many deep things, but we also put it in a way that is quite digestible. For us, ensuring that we are sending a message to young people and people of all ages. [We are] challenging the patriarchy all the time. Just constantly challenging it by being ourselves.”

Amal Abdi is a writer from London, and a film reviewer at Risen Zine.

Twitter: @amoollie_ // Blog: https://amalabdi.contently.com/

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘Review: Hive City Legacy’ by Jenna Mahale

There’s been a lot of debate about the phrase ‘people of colour’ lately. The term has been widely used since the late 1970s, often to encompass the issues faced by those who move through the world without the shelter of white privilege. It’s a useful little term that doesn’t assume much about its subject, but this sometimes works to its detriment. Words like that can too easily gloss over things like colourism within non-white cultures. Words like that can forget specific issues, like anti-blackness in the South Asian community, or Islamophobia among Hindus. Some argue that we should do away with the phrase entirely, that it erases the range and the nuance of experience contained within each ethnicity.

If there is one thing about Hive City Legacy that can be criticised, it’s that it spreads itself a little too thin in trying to capture everyone’s experience. The multidisciplinary show runs for just over an hour, and jumps between snippets of people’s lives that have shaped by their identity and, more often than not, their diversion from the presumed norm in the UK. The result is a starburst of energy, emotion, and information for and by ‘femmes of colour’, another sprawling category. However, it’s undeniable that Hive City Legacy must also account for a white audience and, to that end, potentially aim to educate it.

These are burdens that, arguably, every forward-facing, non-white production feels a need to shoulder. Inclusion is a noble goal, but a near impossible one. But what can we really expect from these shows when these stories have been stifled for so long?

To its credit, Hive City never feels excessively didactic. It manages to successfully embody the ‘show don’t tell’ adage of good art, and does so through an impressive variety of mediums. We are treated to forms of performance ranging from song to spoken word to rap; from Poi ball dance to twerking to aerial rope.

Farrell Cox plays a child-like audience proxy, stumbling through the stories of the Hive City collective’s members, and eventually coming to grips with the significance and weight of her heritage as a femme of colour. She begins the show alone, clambering over the columns of Emily Harwood’s malleable, honeycomb-shaped set. An aerialist by trade, Cox is agile, expressive, and quietly comic.

Once all nine performers are on stage, the atmosphere quickly becomes electric and emotional. The pulse of the music quickens, the choreography is strong, solid, united movements. This is not to say that anything feels same-y. Really, the result is more like being in a small, hot club with all of your friends, and feeling the beauty of watching them break it down in their own way. While the non-linear format can feel disjointed at times, it allows the individual performers to shine, and offers each femme a platform to talk about the experiences closest to their heart. This is valuable, if not the most cohesive to watch. Hive City’smost powerful moments emerge when the ensemble comes together to collaborate.

Krystal Dockery’s ‘ode’ to Britain is a stand-out performance. The actress and voice-over artist gets to exercise the full range of her abilities in a mash-up of song, dance, and physical comedy involving the whole cast. Koko Brown’s solo performance, centred around the subject of mental health, also brings in the other femmes in arresting, synchronised choreography. Brown mixes spoken-word, rap, and song to express a rattling combination of emotions; her frustration is made palpable, her pain is made familiar.

Hive City makes some salient points, but for activists who have been following the issues discussed for a number of years now, some can feel a little tired. By providing a catch-all discourse about the ‘experience of femmes of colour’, Hive City writes itself into a corner, and is forced to somewhat condescend to its better-informed audiences, namely being femmes of colour themselves, spotlighting perspectives that have had a platform for a number of years now.

‘People of colour’ is a flawed term. But its usefulness can’t really be dispensed with just yet, because there are still experiences that unite us in diasporas, as ‘the other’. Hive City Legacy doesn’t perfectly encapsulate the experience of femmes of colour, but what it does manage to do, I think as I dance on the stage, under ultraviolet light, surrounded by the cast and other audience members, is perhaps something more special.

Jenna Mahale is a freelance journalist and editor from London

Twitter: @jennamahale / Contently: https://jennamahale.contently.com/

0 notes

Text

‘The need for authentic, vulnerable Black men on stage' by Omolade Ojo

“Barbershops have always been a safe haven for Black men. This has always existed as our community, being passed down from generation to generation.” Ade Dee Haastrup tells me. We are sitting in the Roundhouse overlooking the view from Chalk Farm Road, where in a few hours, both Haastrup and Demmy Ladipo will be performing Barbershop Chronicles for the second time that day. They throw words back and forth to describe the play. “It’s fun.” “Energetic.” “Colourful.” “A rollercoaster.” “Uncomfortable and Comfortable.” Haastrup chirps in with “Rollercoaster” again, setting off a round of laughter, but it is summed up by Ladipo who finishes with “It’s a celebration”.

To finishing reading this piece, go to the Roundhouse website, here:

https://www.roundhouse.org.uk/blog/2019/10/the-need-for-authentic-vulnerable-black-men-on-stage-/

Omolade Ojo is a writer from London with a passion for food, theatre and books.

Twitter: @omoeats // Blog: www.omoeats.wordpress.com

0 notes

Text

‘The Hive City Legacy cast on prioritising people of colour and disrupting the overwhelming whiteness of theatre’ by Tenelle Ottley-Matthew

Something special often happens when black women come together and take up space. I have told myself this for years, even though I was unsure of how to articulate this when I was younger. Almost every day, I am reminded of the power of our many voices and stories. They rile me up and fill me with a plethora of emotions including, but not limited to, joy, hope, validation, sadness and anger.

The idea of “taking up space” is one that has been increasingly encouraged by and for those belonging to oppressed and marginalised groups. Taking up space means different things to different people. Within the arts, taking up space can perhaps be tied to increasing the representation and visibility of underrepresented groups and people from those groups telling the stories they want to tell in the way they want to tell them. In an age where words like diversity are often thrown around in public discourse without much substantial meaning or intent behind it, the current interest in black women’s experiences and stories can sometimes feel like a trend. It’s almost as if the music, film, TV, theatre and book publishing industries are eager to get a piece (and some profit?) of the ever-endearing #blackgirlmagic pie.

The last couple of years have seen a noticeable increase in the number of theatre productions, particularly among smaller, indie theatres, addressing black British identity and experiences and what its like to be a black woman in Britain. In 2018, shows such as Queens of Shebaand For A Black Girl at Camden People’s Theatre left a major impression on those who were fortunate enough to see them (including me). Likewise, the more recent, much-talked-about and much loved seven methods of killing kylie jennerat the Royal Court had a huge impact on its audience during its run at the Royal Court, and no doubt it will long afterwards.

In a similar vein to the aforementioned shows, Hive City Legacy is a masterful and refreshing theatre production that explores what it means to be a femme of colour today. One that proudly centres and celebrates black and brown women. Hive City Legacy defies both genre and stereotypes with a near-perfect blend of hip-hop, spoken word, comedy, dance, acrobatics and much more. It tells the stories of nine femmes of colour, played by cast members Aminita Francis, Rebecca Solomon, Krystal Dockery, Farrell Cox, Dorcas Ayeni-Stevens, Koko Brown, Elsabet Yonas, Shakaiah Perez and Azara Meghie. It’s the kind of show that immediately makes you feel at home as a black woman or woman of colour. This, as I found out from the Hive City Legacy cast, is very much what those involved in the show hoped to achieve. By appealing directly to people of colour, they hoped to somewhat disrupt the overwhelmingly white, middle/upper-class spaces that theatres often are.

As Koko Brown puts it, “We invited people [of colour] in by putting it out there on our social media and saying, we want women, brown women, black women, black non-binary folks, black trans folks to come and see this. We don’t just go, ‘Hey the cast is full of black people. How cool?’ By saying ‘We want you here. You are wanted in this room. You are needed in this space.’”

All cast members are aware that the nature of Hive City Legacy is bound to make some audience members, particularly those who are not people of colour, feel uncomfortable. This, they agree, is something those people will just have to deal with for an hour. After all, it’s merely a tiny taste of the discomfort they all feel in their lives, navigating this world as black and brown women.

“…there are plenty of times in the show where we refer to things that, if you’re not a person of colour, you’re probably not going to understand…and that’s not my fault!” Amanita Francis states matter of factly, immediately prompting audible agreement and hearty laughter. “There are plenty of majority-white shows that I go to see and there are references that I don’t get and that’s fine on their side. We’re catering to the audience that we want to cater for and that’s people of colour.”

The nine-strong cast of Hive City Legacy seems to have built a solid, sisterly bond between themselves and the rest of the creative team. It’s a bond that no doubt began to form in the early stages of the unconventional audition process. They effortless laugh and banter among each other and sometimes finish each other’s sentences. “Everybody that has taken part in devising this and making this happen has been a woman of colour, or at least, it’s been a woman,” says movement artist Elsabet. For Elsabet, Hive City Legacy is the first time she’s worked solely alongside women. It’s an experience that has changed her outlook and given her a renewed sense of self-belief. “…between last year and this year, I’ve taken so many more risks when it comes to creating work and I feel empowered to trust myself as a leader.”

2019 is the second year that Hive City Legacy has blessed The Roundhouse. The show opened for the first time in summer 2018 following a casting call that was put out online in search of performers. For a show that contains a multitude of performance art forms, it would be correct to assume that the cast was put through their paces and expected to keep an open mind throughout the audition process. The women were asked to do “random” things like give themselves a superhero name before showing up to the audition to perform lip-sync. “We had to sing for our lives!” recalls Krystal Dockery as the other cast members erupt into laughter. Krystal offers some of the show’s stand-out moments, thanks to her masterful twerking and burlesque numbers. The cast also participated in a catwalk, took part in a speed-dating exercise, learnt choreography with Yami Lofvenbergand came up with creative responses to a Maya Angelou poem. While it was intense and off-the-wall at times, it was an audition like no other, as Krystal explains. “I’ve never been in an audition that was so supportive. It was weird… it felt like everyone was rooting for the other person which was incredible.”

Talking to the cast, it’s clear that there’s a strong rejection of the single story and narrow representations of black women and women of colour. One of the aims of the show is to remind the world that there is no one way or right way to be a femme of colour while highlighting the challenges they continue to face in 2019. “It’s like challenging the patriarchy all the time. Challenging white men, white fragility, white supremacy, all of that shit. We’re out there constantly challenging it by just being ourselves - and by performing as well - by doing things like this [Hive City Legacy] which we should alreadybe getting but we’re having to fight to get these opportunities,” says Shakaiah.

While the show has certain aims and messages it hopes audience members will take away, the deeply personal aspects of a show like Hive City Legacy means that it’s highly unlikely that two people will react to it in the same way. Koko Brown puts it perfectly. “I think the show has multiple messages depending on your background, where you come from and what bits resonate more with you. There’ll be a message you get that the person sitting next to you won’t get and vice versa… It’s a really personal thing.”

Ultimately, this is the beautiful thing about Hive City Legacy. Boy, do the performers know how to put on a dazzling and electrifying show. They command your attention with their talent and individual skills, yet they connect with their audience on an emotional level in a way that feels incredibly effortless and authentic.

I’ve known for a long time that something special often happens when black women come together. That special thing isn’t always easy to describe or communicate but it certainly looks like the nine Hive City Legacy performers dancing their hearts out and revealing their various layers and complexities on stage. Collectively and individually, they exude that special, magical thing that is powerful and meaningful beyond words.

Tenelle Ottley-Matthew is a writer from London with bylines in Huck, gal-dem, Pride magazine and more. She will soon be working in book publishing.

Twitter: @misstenelle / Blog: tenelleottleymatthew.com

1 note

·

View note

Text

Brainchild Festival 2019 @BrainchildFest [Nkechinyere Nwobani-Akanwo @NNwobani]

Brainchild Festival – it’s a vibe?

Brainchild 2019; 8 years after the idea was conceived and 6 festivals later in a field in East Sussex 3000 people formed an intimate community united in just having a really good time.

I’d not been before but I’d seen the line-up every year, heard of other people’s good time there, and been tempted. This year I made it, with the insight from one friend mentioning it was the highlight of their year, and another saying it was basically South East London—my long-loved born and bred home turf—in a field. Bar set!

It’s a vibe is all I kept hearing; on the coach, in the queue as groups of friends recognised other friends, while scouting out the perfect pitching spot, while eavesdropping on stewards’ conversations. Those words, a truly ambiguous phrase and redundant without context, were flung left right and centre repeatedly. Like when someone says ‘you know what I mean’ after every half-baked sentence giving no space to agree or question what they mean. You know what I mean? What is this vibe that it is? How can everyone be on and recognise the vibe? Where can I find the vibe, or does the vibe find you? I wanted in.

A few hours and several circuits of the site later, and having taken in the numerous delicious sounding offerings of the food stalls, I plotted when I’d try what (priorities). I’d become familiar with the different venues and appreciated the artistic offerings in the instillations on the landscape, some to be viewed, some interacted with, some thought over. I began to recognise people: their voices, styles and mannerisms, like that community/village feel estate agents are always trying to describe and developers are always trying to forcibly create. I’d clocked characters, those archetypes you find in ever situation and heard enough people refer to Nunhead, Camberwell, New Cross Gate and Herne Hill as Peckham (it’s the place to be from now) to know this was the ‘up and coming area’ ‘redevelopment scheme’ South East London in a field.

As the first day came to a close with the deep rhythms of percussion playing with syncopated brass, and solo flourishes from the masterful musicians of Maisha that undeniably ooze a vibe. I got lost in the rhythm and heart, the soul of it all, that was laid bare on the stage. The energy was undeniable. It didn’t matter who you were, where you were, who was there, it was that middle bit of a Venn diagram that all these various types of people occupied and found pleasure in. As I made my way to bed—old lady lightweight—to the sounds of Touching Bass’ eclectic set, each sound accompanying the movements of the revellers as though they were in deep rooted cahoots, I thought, it’s not bad, this, I could do more of this.

I approached Saturday with more gusto, up at 10am for the very gentle yoga, which had a stellar turn out considering how late the partying went. Consequently, the coffee queue was an hour long and an Instagram overheard page’s paradise. People freely exchange tales of how gross it is trying to having sex with a random in a tent. Throwing up in a peg bag (turned out to me mine) through to the woes of having a well-paid office job which you might pack in to be a barista. The hardship of having to go away on a lush sounding holiday with your family, and clusters of conversations speaking of and for the working classes, people of colour and LGBT+ community—with none of them present. These are the people I’d eyeball h a r d at home and then keep it stepping to find my peace but there was no respite here.

I wandered from talk to workshop, all of them filled with passion and knowledge, a refreshing combination. I listened to captivating tones and heartfelt lyrics, energy raising sets all giving me food for thought at every turn, and here there was space to mull and chew over the thoughts without having to get something done, be somewhere, talk to someone, be someone. I can see the attraction for people choosing this space to be a holistic time out.

I’d earmarked Dylema collective having no prior idea what I was in for…

And then. I found the vibe. No, not just the vibe. My vibe.

That Saturday night I found my vibe.

From the band’s first bar, it was different. It felt tailored, like they were here to perform for us, giving over the gift of their songs. Hand-crafted for our pleasure. Side-stepping any blasphemy, it was akin to that feeling people speak of when church is on point. All the sermons hit home and passages reveal answers to your queries and the hymns raise you up. All before Dylema named and carved space for the black girls, with rhythmic chants of ‘What If A Black Girl Could’. A moment being seen and lauded with no expectations or entry requirements, the purest of offerings.

It’s not collective. It’s not about everyone being in it together, feeling the same thing. It’s personal, it’s a first person feeling, indescribable, hence why it so vague, why it’s just referred to as ‘a vibe’. A phrase that truly means something unique to the author of the words. And that’s what this place is. Brainchild is a Vibe because at some point, for many several points during the weekend, you find your vibe. It charges you up and tops up your tolerance and reinvigorates your soul. No longer would the conversations by the [insert P.C phrase for gentrifiers] weigh heavy, or the couple audibly digging for treasure down each other’s throat grate on me, or the pseudo intellectuals playing buzz-word bingo incite near violence. I had power now. I was unbothered.

That air moved with me even as the festival began to wind down on Sunday. The palpable reality of real life crept in as conceptual conversations about capitalism turned to thoughts of ones practical contribution to the system, all underscored by soulful jazz, hypnotic drum and bass and heart thumping hits. I found small pockets of enjoyment in spoken word, book readings and theatre.

And a cheeky mid-week top up shop vibe, in the form of Brainchild Poetry Showcase’s Bridget Minamore and Vanessa Kissule’s performances. Poems of love and octopus’, a deep clean breath void of politics, gender and oppression. All important and worthy of taking up physical and mental space, but the breath I needed all the same. Just listening, face value, and laughing.

The party waged on till near 6am; like punters saying farewell to their local pub that they’d take for granted was always going to be there (even if they all abandoned it for the wine bar). I found delight in making these observations and comparisons, and looked forward to wielding my new-found energy in my real-life endeavours.

People come back year after year after year, to slip back in with their alternate community among the parched grass, in the protection of the woodlands or beneath canopies of canvas. Without losing their mind, friends or tent, they find their guaranteed vibe.

0 notes

Text

Critics of Colour in 2019 (and hopefully beyond)

Last week, two thirds of the Critics of Colour team went to see The Convert at the Young Vic. The play—a blistering exploration of faith and family, anchored by great performances and stunning set design—feels like a parable about change. Is change possible, the play seems to ask? Can we change not only ourselves, but also the people and structures around us? How much change do said structures have on the way we try to enact change, whether we accept them or not?

Change has always been a key component of the reasons why Sabrina, Georgia and I decided to come together and set up Critics of Colour. Misty, the play that changed everything, was the catalyst for us to attempt to change a theatre industry that for so long has felt deeply reluctant to shift in even the slightest of ways. 2018 has been a beautiful year for so many theatre lovers who value a diversity in the voices and the stories on our stages, but, as ever, the standard critical voice has often been deeply frustrating for so many.

There have been more plays by and ‘for’ (whatever that means) people of colour than ever before. However to put it bluntly, what hasn’t changed much over the past year are the type of people reviewing this work. If anything, the greater diversity on our stages has made the lack of diversity in our theatre publications more and more frustrating.

Critics of Colour received an amazing reaction when we launched in April—one that, if I’m honest, I was wholly unprepared for. The barrage of emails and the pull between people, press officers, tickets, and Tumblr were far more than any of us anticipated. If we’re honest, the three of us had relatively straightforward aims: 1) get some free tickets, 2) send people of colour to see some shows, and 3) publish the reviews on our blog.

Simple, right? Not so much.

As [the months went by we found ourselves thinking more and more deeply about Critics of Colour, and wondering if the relatively limited yield we were putting out into the world was enough. It’s been a while, but thanks to the help of some long chats between ourselves and with some lovely, helpful people in the industry (you know who you are), we’ve come to a conclusion. Is Critics of Colour, in its original incarnation, enough? It wasn’t. It isn’t. But soon? We’re hoping the changes we make will be.

So, some news. If it hasn’t been obvious, Critics of Colour has gone, and is going quiet for a few months. There are lots of reasons behind this, but the main one is that we’ve realised that the changes we want to make? They’re much, much bigger and bolder than we first imagined. We don’t only want to publish a few reviews from people of colour on a blog. We don’t even necessarily want to gather non-white writers and help to get them writing for major outlets, or force the white, middle class theatre establishment to consider writers of colour to be ‘as good as’ the big names who have commandeered British theatre writing, often for decades. We want more than change—we want the standard critical voice that reviews British theatre to get flipped on its head, and we want to try to question the very nature of what a review can and should be.

Instead of writers of colour deemed ‘just as good’, we want new voices—from working class, disabled, female, and queer POC backgrounds—to be seen as what they are: necessary. I believe this industry won’t survive if we don’t change the way theatre journalism is seen. Instead of tension-filled take-downs or basic ‘go and watch this’ promo, reviews should always aim to expand conversations about a production, and entice the many people in this country who don’t consider themselves regular theatergoers to jump face first into the magic of the stage. To try and help this along, we will be spending the next few weeks and months applying for various things, doing call-outs for people to get involved, and reaching back into our networks, and making offers to the many amazing writers who have written for us already.

On that note, we’d like to express our massive and overwhelming thanks to everyone who has supported us this year, as well as everyone who offered us tickets or who sat us down for meeting and interviews.

Most importantly, thank you also to the many people of colour who took a risk and sent their writing over to us to publish on the Critics of Colour blog: Marianne Tatepo, Ava Wong Davies, Fabia Turner, Abi McIntosh, Sarudzayi Marufu, Nkechinyere Nwobani-Akanwo, Saalene Sivaprased, Youness Bouzinab, JN Benjamin, Jamel Alatise,Casey Spence, Lucy Chau Lai-Tuen, Mia Georgis, Pearl Esfahani, Nina Reece, Darrel Blake, Naomi Joseph, Roberta Wiafe, Adanna Oji, Jude Yawson, Shamima Noor, and Jamal Simon. Thank you for your words. When we know for certain what is happening next, and what specifically we can do for you, you will be the first people we tell.

This is a statement of intent, but also one of promise. To everyone who’s been so supportive in ways both big and small, see you in the Spring! and we hope to be telling you about some exciting news then.

All our best,

Bridget, Sabrina and Georgia

0 notes

Text

An Adventure, Bush Theatre [Jamal Simon @CJSimon123]

An Adventure, currently starting a 5-week run at the Bush Theatre, is all at once a story of love, growth, choice, and life in a post-colonial world.

Vinay Patel opens his play with this comical and intimate back and forth between protagonists Jyoti (Anjana Vasan) and Rasik (Shubham Saraf) setting up a near-on epic story which spans 64 years as we follow their lives from 1954 through to 2018. An Adventure is named as such because it takes you on a journey which spans three hours, in three acts, across three continents in such a well done manner. The matching of Patel’s well-paced script and Madani Younis’ driven direction means that what might have felt like a dreary slog, leaving the audience uncomfortably drowsy in their seats, was actually incredibly gripping and at some points had the audience reeling back and gasping in shock – it was the first time I’d ever been in such an audibly responsive audience.

Despite the setting of this Adventure, Patel didn’t let a period piece limit his method of expression. Our characters speak with their own voice, use current colloquial terms and reference modern movies long before they were conceived. This builds upon the understanding that the past still bleeds into the present and highlights the tact Patel has for thematic exploration.

The space provided by The Bush Theatre’s black box which had the audience on two sides of the action created this comfortable close feel which persisted throughout. This eased the audience into becoming immersed in the worlds of these characters. We sit mesmerised as the stage is transformed from Indian home, to Kenyan farm, to London flat, to Danson Park in a series of well crafted, colourful, and hypnotic movement sequences. At one point my eyes were drawn to these black silhouettes contrasted on bright yellow walls dancing fantastically back and forth.

Younis and his refreshingly diverse cast command the stage with such ease in a space where it’s easy to have one side of the audience miss a syllable or an emotion. It’s safe to say our heroine Jyoti and the actress whom embodied her, Anjana Vasan, steals the show with such an empowering and empowered performance bringing to life the adventure of a woman attempting to defy the restrictions of her society and is left to face her successes and her failures.

Where the show falters began with the connection between actors. Despite some superb individual performances there were moments where it seemed that I wasn’t watching two people in the same room but rather two sperate scenes where the words followed some understandable audience by happenstance without maintaining a mutual emotional response. So came about mere moments where I was drawn out of the moment of this world.

Despite some brilliant moments of dialogue where Patel confronts the truths of colonialism and the establishment as the show came to close I had one question. Patel asks ‘When you look back at the story of your time together, can you bear to ask yourself: was it worth it?’ And as the lights went down I asked myself the same thing. Was it wort it? After three hours, I couldn’t say no but I couldn’t jump to say yes either. An Adventure felt more like a long enjoyable walk through a museum, you learn a lot, you see some fantastic things, but as you leave you know it’s unlikely you’ll revisit it for a few years.

It’s probably true that I’d have appreciated the piece more if I had a larger knowledge of Empire. Still, the story of a migrants making a better life for their children, a country in conflict, and a new generation learning from their parents past is something that deserves the spot it has on the stage.

Three and a half stars ***

Jamal Simon // I'm Jamal, currently a second year sixth former and aspiring playwright who dabbles in acting and singing. I've performed in a variety of venues from the Southwark Playhouse and the Young Vic, to Soutwark and St Pauls Cathedral. Proud to be able to watch and review so many politically fused and creatively brilliant shows. // Twitter: @CJSimon123, Instagram: @CJSimon123

0 notes

Text

An Adventure, Bush Theatre [Fabia Turner @Kwia35]

From an initial encounter in post-Partition India to an intrepid venture into war-torn colonial Kenya, domestic disputes in discontented ’70s London to wistful twilight years in the present day, Vinay Patel’s ambitious marathon charts the trajectory of an Asian couple’s marriage over six decades.

It’s a promising comedic start as gawky Kenyan-born Rasik (Shubham Saraf),

dressed in an oversized Western suit, struggles to woo razor-sharp Jyoti (Anjana Vasan). Impulsive Jyoti with her caustic wit teases Rasik to discern whether he’s an acceptable match for her inescapable arranged marriage, and when he eventually manages to semi-impress her their romantic journey begins.

The rush of the early scenes reflects the nervous energy of two strangers

becoming acquainted, though this hurried pace means much of the hilarity is

lost. Soon the chemistry between the young lovebirds dwindles and it’s

uncertain whether this is deliberate or not.

On arrival in Nairobi, Rasik secures a job with the British Department of Public

Works and from here the play takes a darker tone. He befriends enigmatic

David Wachiri (Martins Imhangbe), a Kikuyu displaced from his fertile lands,

by European settlers, to the city suburbs. David’s distinct function is to narrate

key events from Kenya’s socio-political history including the state of

emergency caused by the Mau Mau revolt in 1952. This factual interlude,

although highly informative, sits peculiarly within the play, and subsequent

details about Rasik’s purchase of Kikuyu farmlands are tedious.

Fleeing violent Nairobi to seek domestic bliss in London, middle-aged Rasik

reveals to his politicised wife that he’s deeply unhappy playing second fiddle.

Other than a brief tussle over a paint pot and protest placard, there is no hint of

his budding resentment. The superfluous, confusing scene after Ba’s funeral

does little to clarify – a device contrived simply to transport the couple to India

and then to Nairobi rather than adding any real flavour or insight.

Sally Ferguson’s beautifully appropriate lighting and Rosanna Vize’s

wonderfully uncomplicated set give the densely-packed dialogue space to

breathe and makes it easier to unpack. Equally, lovely transitional moments

flow and interweave well, such as the graceful emptying of grain bags to

transform the stage into a coffee-drying patio. Use of multimedia screens ensure the play is rooted in the present as well as the past, though the accompanying electro-funk motif was perhaps a step too far and seemed incongruous.

Overall Madani Younis does a confident job directing what is a mammoth play with no real plot, which would be fine if it were not for the lack of tension or intrigue. The play felt unnecessarily long – more show less tell would have helped as much of the action happens offstage: Jyoti’s picket-line demos, daughter Sonal’s (Aysha Kala) racial abuse and Mau Mau rebels’ horrific torture by the British military are some examples.

The last scene between the elderly couple is the most touching as they reveal,

with uncensored honesty, their true hearts’ desires. Their vulnerability is

palpable and believable thanks to Selva Rasalingam’s endearing portrayal of

Older Rasik combined with Older Jyoti’s (Nila Aalia) painfully harsh lines: ‘I

thought you were a joke, but a slightly better joke than the others.’

Fundamentally this play is not meant to be a history lesson: it’s a warning about

what happens if you marry for the sake of marrying, about the wishes and

values that get swallowed up by compromise, and the bitter resentment that

builds if ambitions are buried. On this Patel is exceptionally strong, showing an

acutely mature understanding of the core issues in spousal relationships.

Fabia Turner // Fabia has worked as a teacher and books editor. She has a keen interest in theatre which includes producing plays at the Brighton Fringe and the Arcola. // @ Kwia35

Title of show: An Adventure

Venue: Bush Theatre

Dates: 13 September–20 October 2018

Writer: Vinay Patel

Director: Madani Younis

Associate Director: Deborah Pugh

Designer: Rosanna Vize

Lighting Designer: Sally Ferguson

Sound Designer: Ed Clarke

Production Manager: Michael Ager

Company Stage Manager: Eleanor Dear

Assistant Stage Manager: Ana Carter

Producer: Bush Theatre

Cast: Nila Aalia, Martins Imhangbe, Aysha Kala, Selva Rasalingam, Shubham

Saraf, Anjana Vasan

Running time: 3hrs 15 (including intervals)

1 note

·

View note

Text

BLAK WHYTE GRAY, Barbican [Darrel Blake @darrel__blake]

Gil Scott Heron once said "The revolution will not be televised", he was right... it will be performed. BLAK WHYTE GRAY takes on the role of decolonising the system, broken into 3 parts that express stages in the struggle in overcoming the challenges in society, fuelled by the idea of radicalism.

Dance and Art have played a vital role in British and Black culture, these forms of expression have been used as tools to reject European Nationalism, Neo Liberalism and Racial Discrimination for centuries. What B.W.G does is, appeal to your conscious appetite by keeping your focus on the minimal lit stage, giving each dancer a moment to shine.

In part 1, 3 dancers exploded on stage with an ecstatic sharp routine. Restricted due to wearing straightjackets, they manoeuvred in sync to a heart thumping melody. Showing the signs off physical entrapment, they also personified the mental slavery that many suffer from. What was exquisite about this part was, the dancers showed unity and it oozed with tribalism in the fight against the restraints. Kicking off the show in such a powerful way, only got us excited for what's to come.

Part 2 was a collective of performers on stage, using body language and facial expressions to tell their story of how they felt. Each dancer told their truths and through harmonised choreography, they all agreed on oppression being their enemy. Using the jurisdiction of the stage, as each routine was performed, they showed frustration at the authorities of what came across as the political institutions formed against humanity. From rhythmically dancing together into a compact mass of energy, to transitioning that spirit into one voice of rebellion.