Note

Hi! I just read your analysis of the P&P 2005 costumes. I'm currently in the process of researching Regency-period fashion for fic purposes; I'm writing a f/f story in a slightly alternate Regency world in which on top of regular marriages, parents (especially in the higher classes) could and did arrange for gay marriages for those of their children who wouldn't inherit - the principle being that the parents could set these couples up with a part of the estate that, upon those couple's death, would revert back to the estate to be inherited onwards, and thus not mess with an entailed estate all that much.

Anyway, long story short, my thought was that in these marriages, there would *still* be a masculine and feminine role, just independent of gender - and there would be according fashions. So, for example, a man's three-piece suit for a woman who took the masculine role in a f/f marriage, just cut towards the female figure, and perhaps with other nods towards the wearer's gender too, and similar for a man who took the feminine role in a m/m marriage.

I just wanted to reach out and see what you think of this and see if you'd have as much fun thinking about this as I have!

Thank you for your message, this honestly sounds really cool!! I think it's very interesting idea to come up with reasoning how arranged same sex marriage would work in a Regency class and land ownership system. I absolutely had so much fun thinking about this, maybe too much fun because look at how long this post is :'D You are entirely free to ignore all of this, I just had a lot of ideas, since your story has such an interesting premise. If you any of this catches your fancy, use it however you like!

I think it makes sense that in a very patriarchal and gender essentialist Regency society the couple would be expected to perform heterosexuality even while literally being in a gay marriage. What you described, men's clothing fitted to women's undergarments, is basically what costumes for breeches roles were usually in theater, roles for female actors, usually as a young leading boy. (Reverse roles, male actors playing female characters, usually elder/motherly roles, were just as common.) Another approach could be to use the women's silhouette, skirt with empire waist, but otherwise the clothing is similar to men's fashion. While most women's Regency styles were particularly strongly contrasted with men's styles, there was quite a lot of masculine styles too, which might work for that purpose.

I think the approach that would make most sense depends on how you want the gnc people seen and understood in the althis society of your story. In Regency society cross-dressing, women wearing pants and men wearing skirts, was seen as stepping into the other gender role. Cross-dressing was not acceptable outside theater, and people who did it needed to be stealth. So if you vision them taking the role of the opposite gender fully and not just in their relationship - living as the opposite gender and treated like that gender (for example the gnc women are allowed men's education and gnc men are not etc.) - I think it makes more sense that they would be using similar clothing as the costumes of the cross-dressing roles in theater. In that specific position it would then become acceptable to cross-dress. But if you envision them more in the societal positions of their own/assigned gender, and just embodying some opposite gender roles, especially in their marriage, I think it might make more sense for them to use the basic silhouettes of the fashion of their gender but in style the opposite gender.

So if you're interested, here's some historical styles and some additional ideas that could work as inspiration.

Before Renaissance men and women's fashions were not separate, but they started drifting apart when wearing skirts became unacceptable for men (which I have a whole long post about). However, very quickly women's fashion started to take influence from men's fashion for certain styles. Riding habit was the first one of these masculine styles for women. It originated from 17th century as men's clothing but with a skirt. From very early on men's military uniforms were a huge influence. A distinctive feature compared to other styles is the long trail so when the woman sits on the horse, her legs are not too exposed. Here's some regency examples. First example is from mid 1797-98. The bodice is exactly in the style of men's fashion of the period. Second is from 1808 in a very militaristic style.

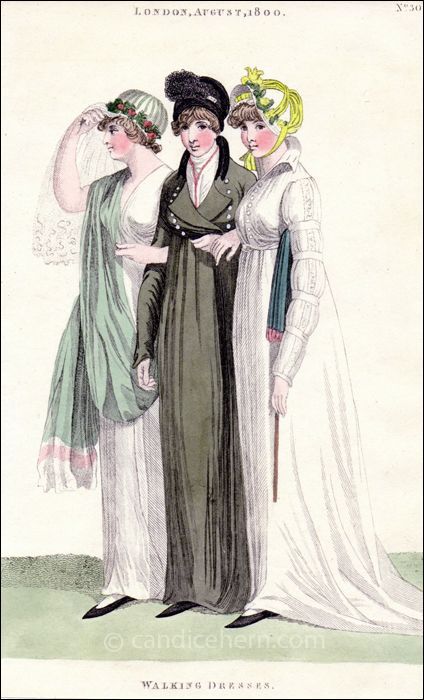

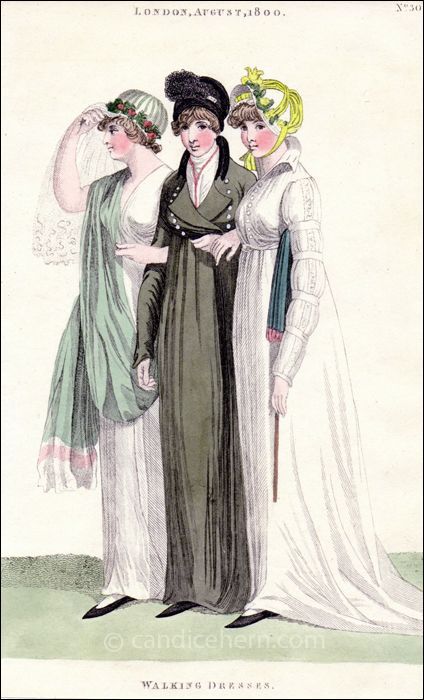

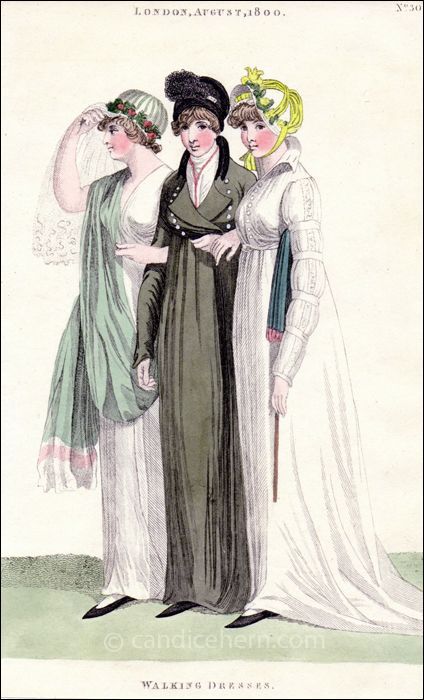

Redingote or pelisse was a long walking dress often in the masculine styles of the riding habit. It was adapted from riding habit to fashionable day wear for outdoors in 1780s. It started as very masculine in line with riding habits, but in 1800s styles without the masculine elements also appeared. Though masculine and military styles were still common. Here's first a redingote from 1800, which follows masculine fashion of the day very closely. The second is from 1810s and has collar from men's fashion and detailing and color are loose references to military styles. The third one is quite military inspired redingote from 1814. It has long train and was probably for carriage rides.

Spencer was a very short casual jacket, modelled after men's fashion again. It became fashionable in 1790s and in the following decades it gained many variations, some not at all masculine in style, and some for formal usage too. Here's very masculine styles as examples, first is from c. 1799, second from c. 1815.

One last trend I'll mention is very short hair imitating Roman men's hairstyles, which became very fashionable for men after the French Revolution, but very similar hair for women became a trend in late 1790s. It was a bold style but for couple of decades it was very popular. I think the woman in the first example above is growing out her Titus cut. There's a little tuft on top of her head, which makes it look like her hair isn't long enough for a bun but secured at the back anyway. Here's couple of actual examples. First is from early 1800s, specific date unknown, showing a slightly longer than usual version of the style. Second is from around the same time, 1798-1805, displaying very well how hair was cut to imitate side burns, which were fashionable for men. The third example from 1809 has the typical cut, where it's very short in the back of the head and little longer and curled in the front.

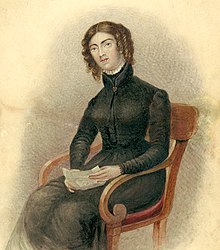

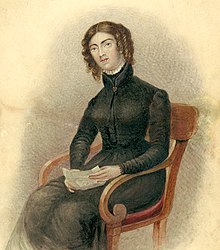

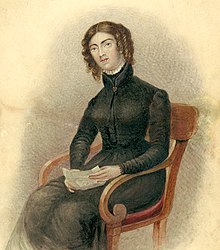

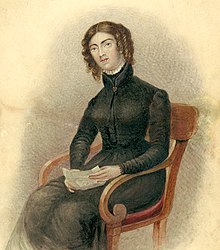

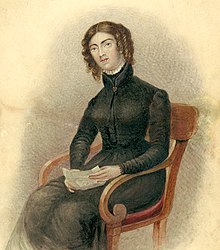

Many Regency sapphics did favour these styles, since they were acceptable ways to present in a more masculine manner. Anne Lister, perhaps the most famous Regency lesbian, presented very masculinely in her portraits. Below her outfit looks like a redingote in this 1822 painting. An infamous upper class Irish sapphic couple, Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, lived together for decades in Whales. Here's an illustrations of them from 1818 in their older age wearing masculine redingotes and sporting Titus hairstyles.

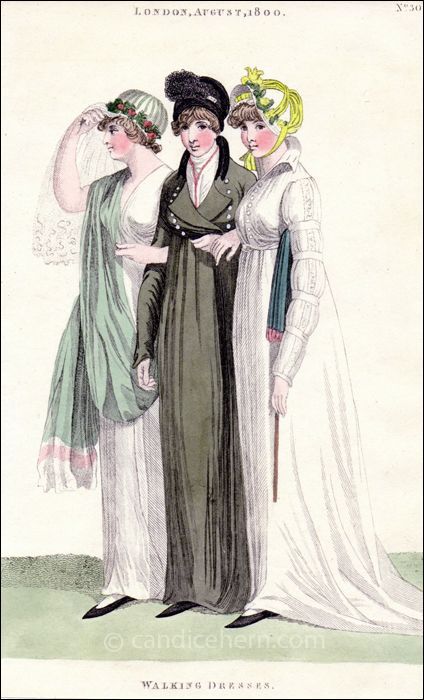

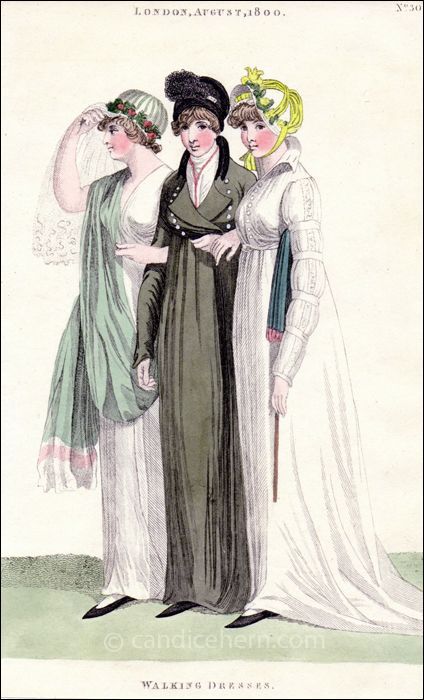

I think in a society where gnc queer people are part of the system, they might have their own slightly different dress codes. For the gnc women/afab people I'm thinking their evening dress might have redingote or spence or perhaps open robe in style of men's evening wear which was black with white cravat (second image below). The open robe could be something like the first image below but fully black, tailored, with large lapels, high collars in the white chemisette and white cravat.

Men's gnc fashion is much harder problem since femininity in men was much less (and still very much seems to be) accepted than masculinity in women. I think it's the old patriarchal superiority of masculinity issue (even if women shouldn't break gender roles at least they are "upgrading", while men would be "downgrading"). I think it might be interesting thought to take inspiration from the styles previous to French Revolution. Regency men's fashion (all Regency fashion really) was result of the French Revolution. I talk more about it in this post, but previously manhood and womanhood had only really been fully available for the upper classes and they were based mostly on displays of wealth. The revolutionaries rejected the aristocratic gender construction and instead created their own. It was based less on class and more on the gender (and racial, but we won't have the time to touch on that here) divide. Aristocratic gender expressions were deemed decadent and the bad kind of feminine. (French Revolution may not have been the origins of the Madonna-whore complex, but they certainly cemented it to the public conscience.) That's how men's Regency fashion was stripped out of colour, detailing and luxurious materials, the overt displays of wealth. New masculine styles were all about evoking militarism, country side and practicality of a working man. Most of it was aesthetic and the class structure remained, but altered heavier in the lines of gender and race/ethnicity. To show you how the fashion was seen, here's couple of satirical cartoons both from 1787 literally calling men wearing the more courtly flamboyant styles women. (First source, second source.)

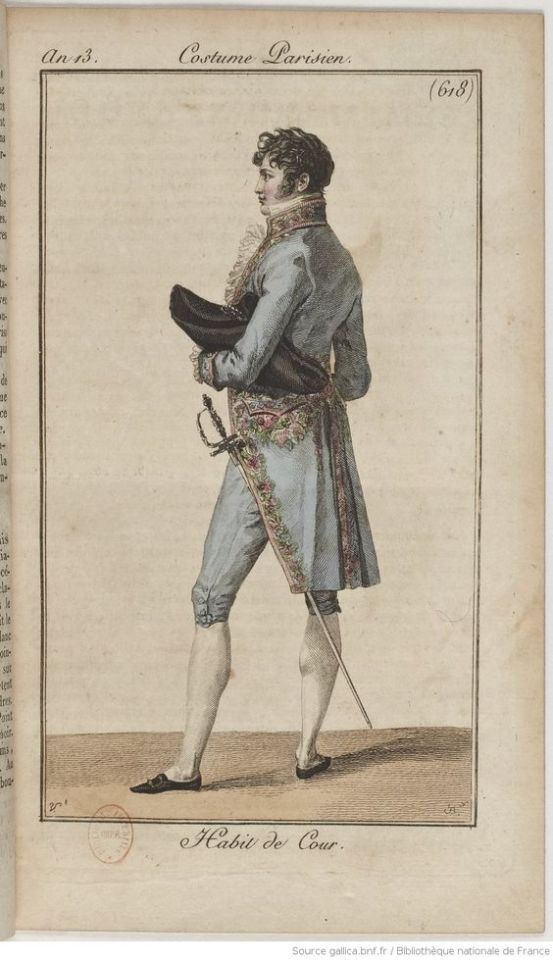

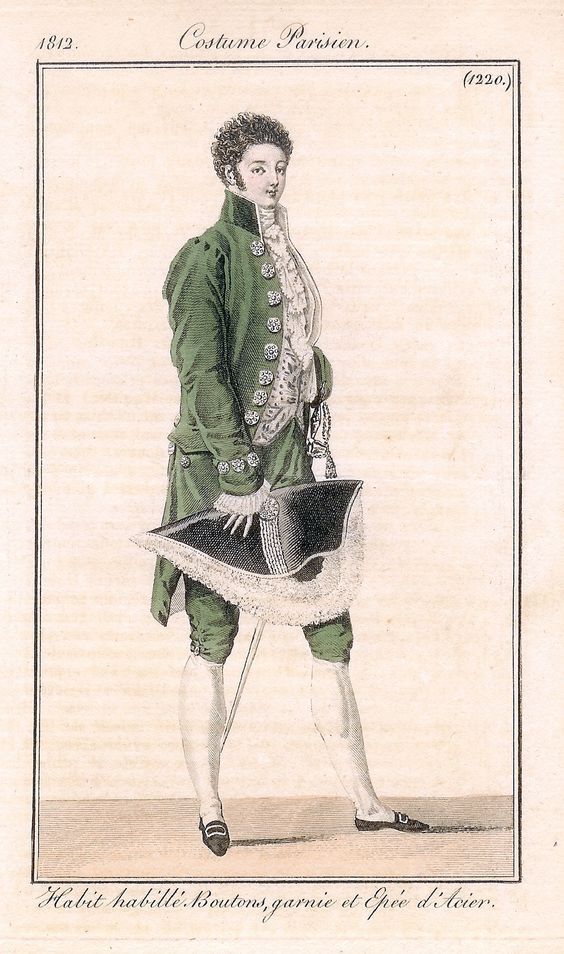

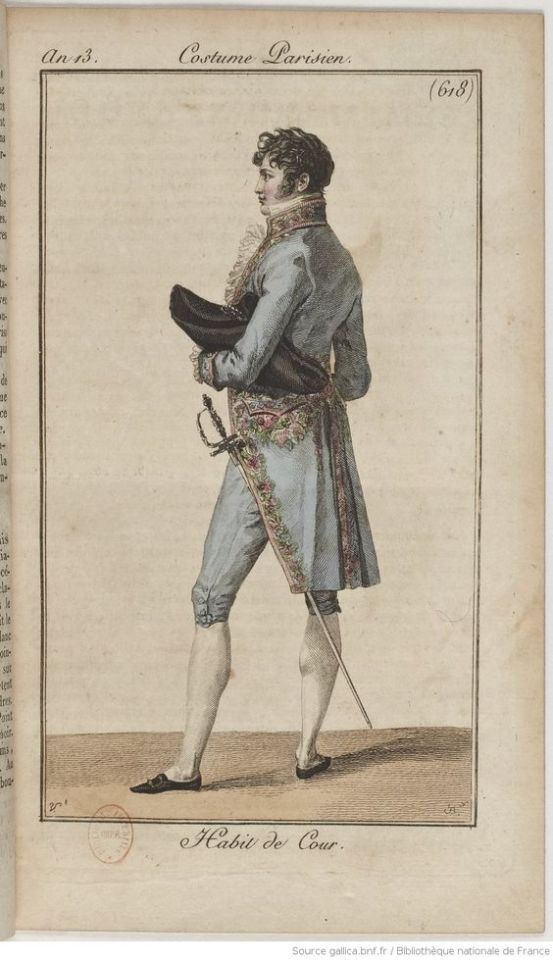

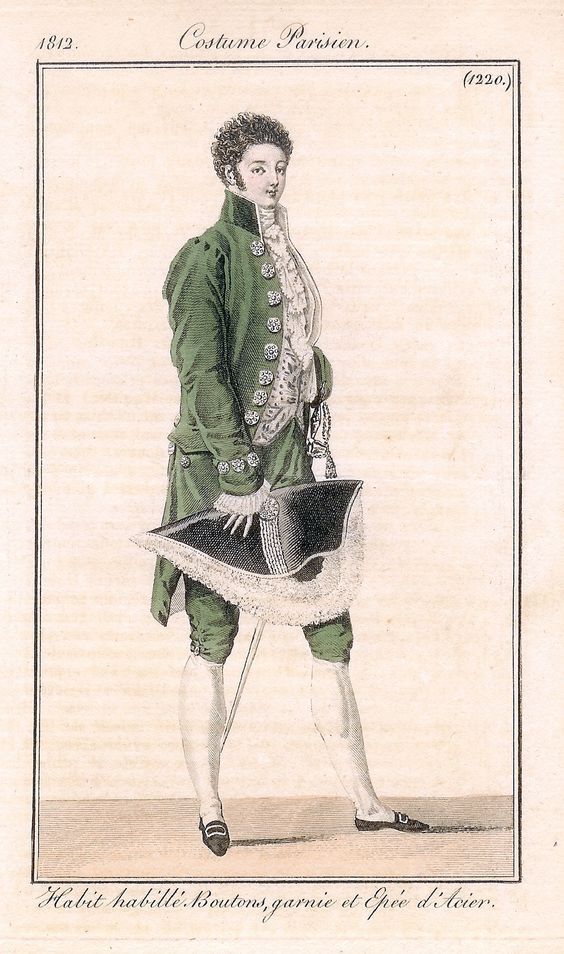

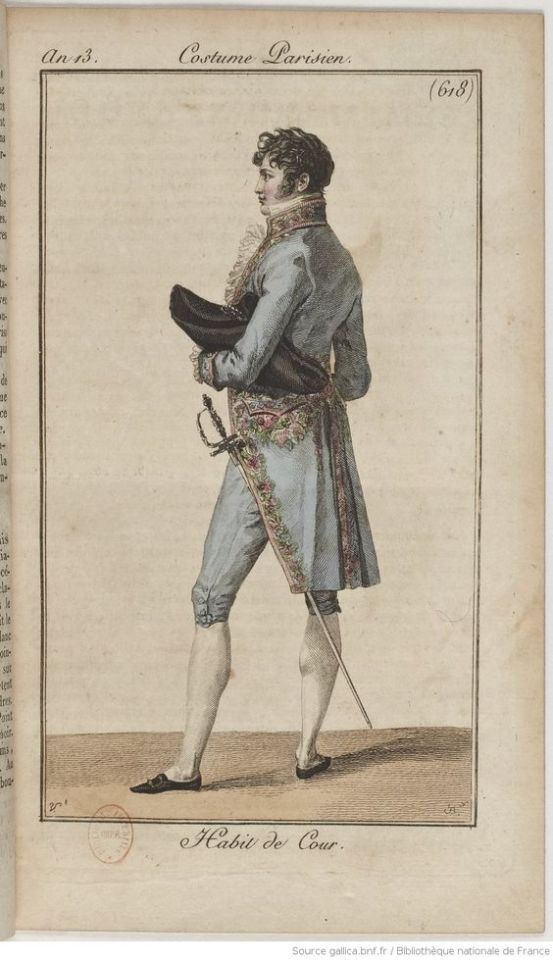

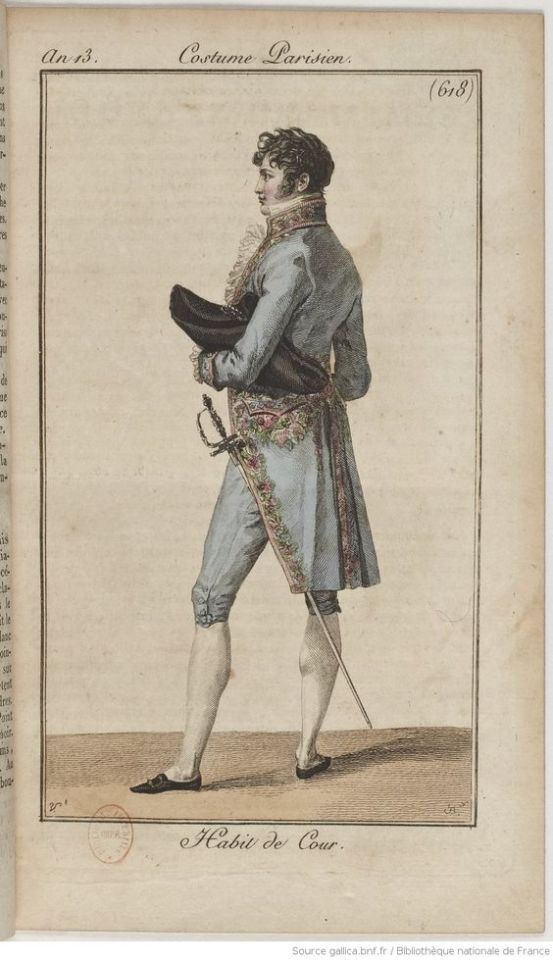

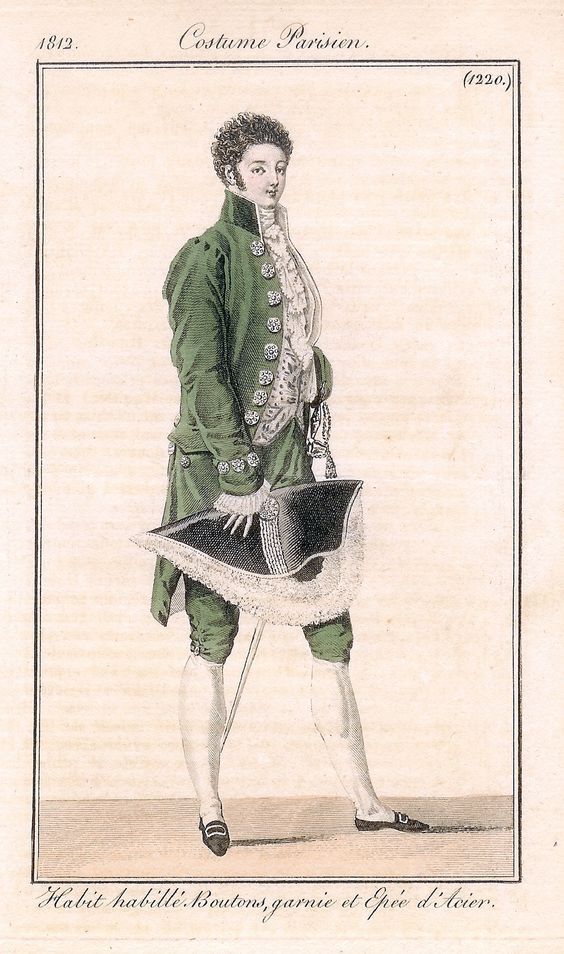

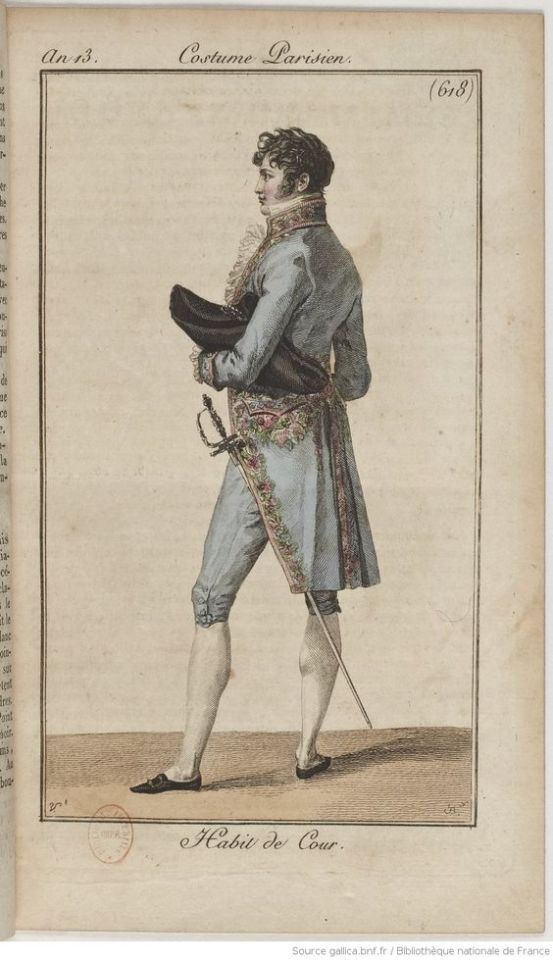

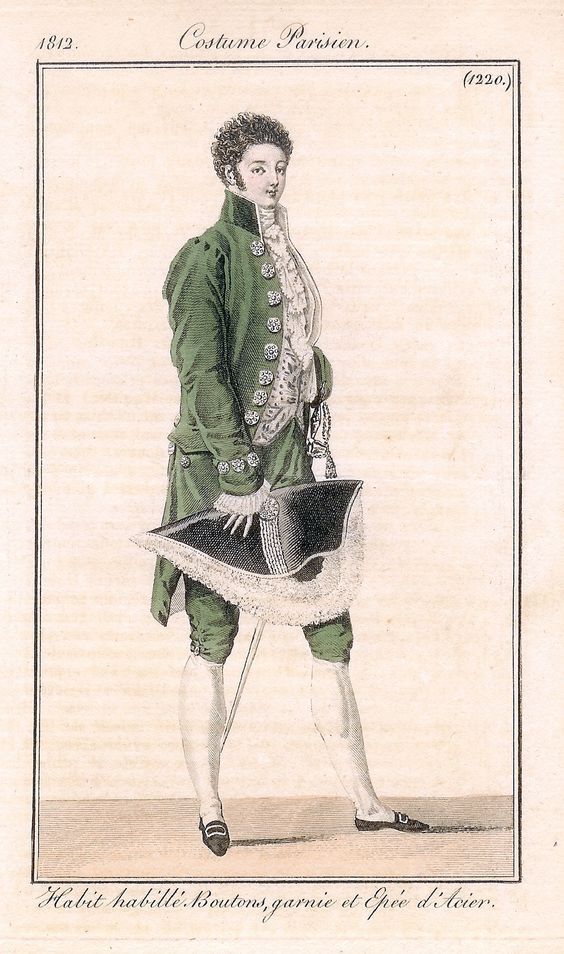

It's not entirely unrealistic that the outdated fashions would remain along the new styles. Courts were resistant to change (especially since the change had anti-monarchist implications) and upheld the outdated dress codes, so court suits were very much continuation of the fashion prior to the revolution (though court suits too started to become increasingly subdued by the 1820s). Here's examples from 1805 and 1813.

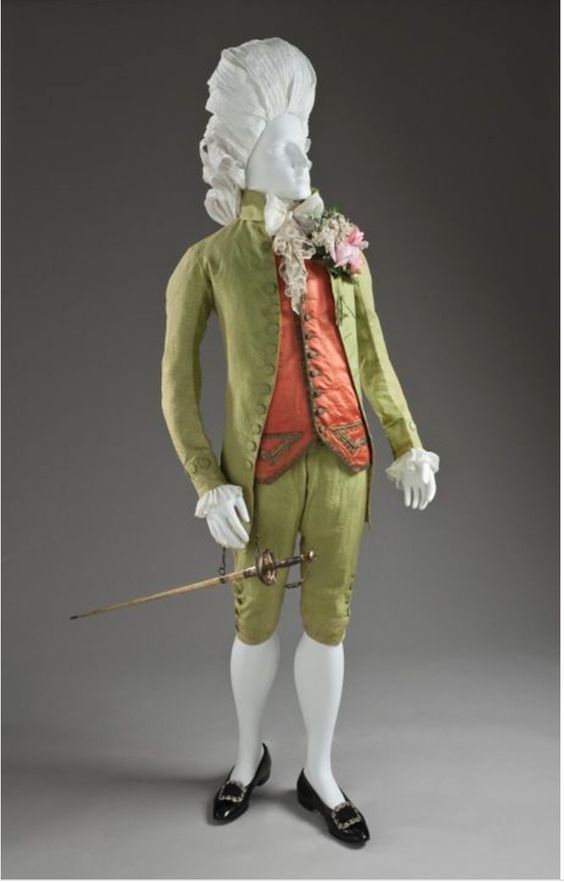

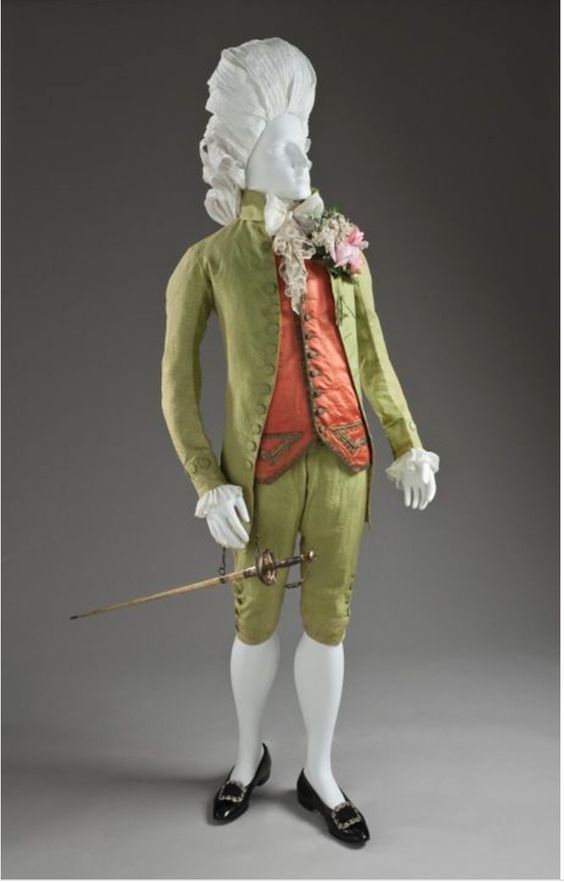

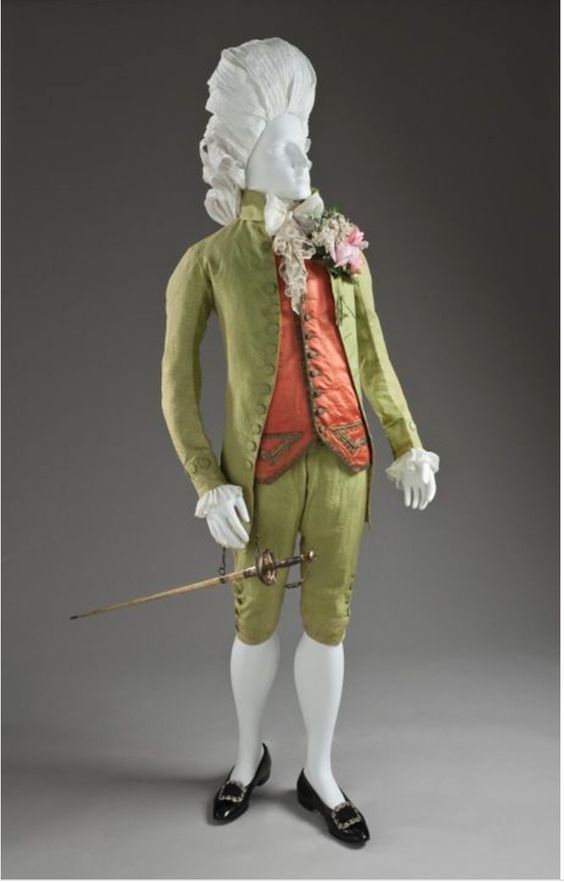

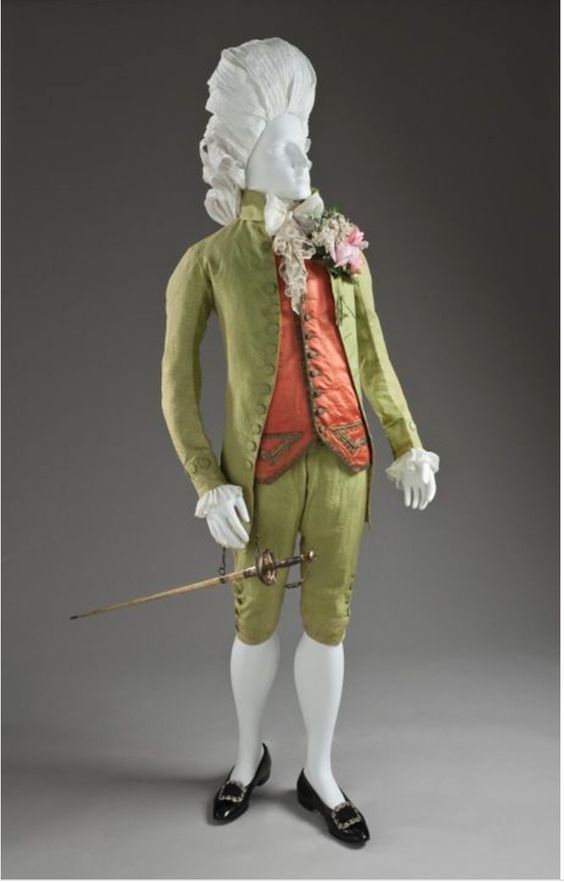

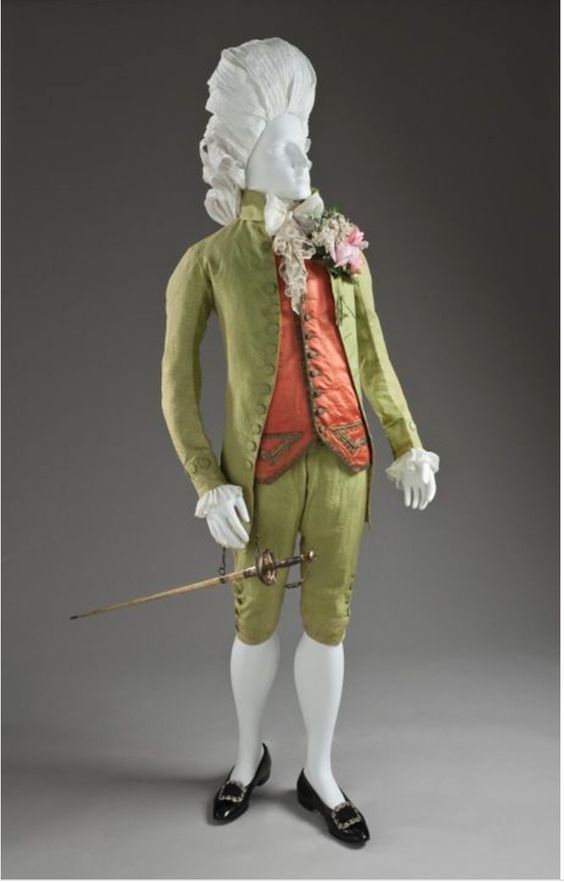

In an alternative historical world like this, I think the pre-revolution styles might have kept on and evolved as a more feminine version of the more general men's fashion. Since masculinity had been tied with rural areas and working class, I think the gnc men's style wouldn't have lapels or turned down collars, which originated from working class clothing, but upward collars like in the 18th century dress coats and Regency court suits (maybe downward collars in informal coats, but not lapels). Maybe they would keep on with the long hairstyles where they tie up their hair with a ribbon, though I don't think they would keep powdering the hair as it went out of fashion for women too. Instead they might style the front of the hair similar to women by cutting hair shorter in the front (basically a mullet) and curling the front of it to frame the face. I don't think they would be wearing the loose trousers, which were very strongly working class till the beginning of 1800s, when they started to be accepted as informal wear for upper class men. Though I think pantaloons would become informal part of feminine men's fashion after general men's fashion would start accepting them as formal wear around 1810s. Here's some examples from 1780s, which could be used as inspiration. First is from 1785-1790, second is from 1788 and the third is from c. 1770.

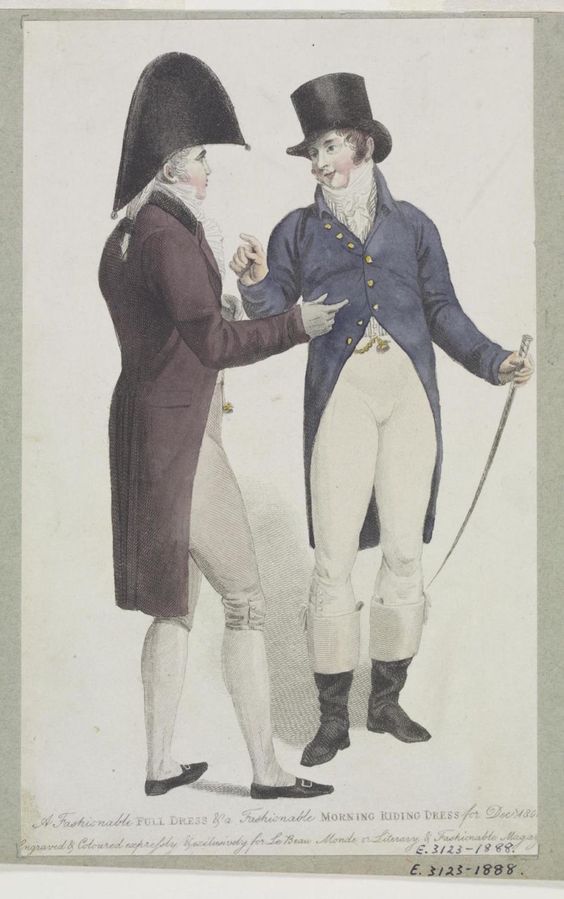

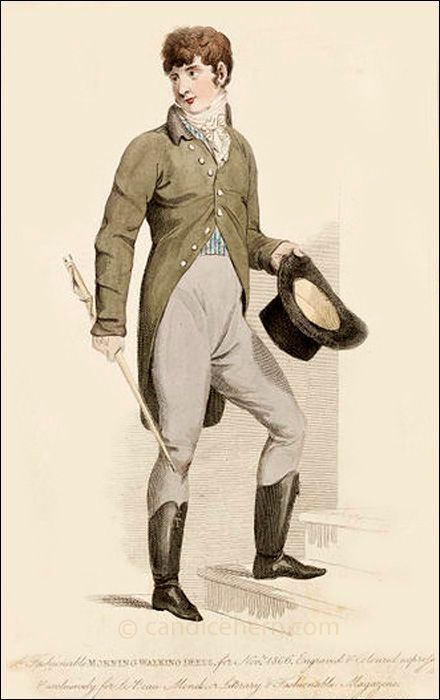

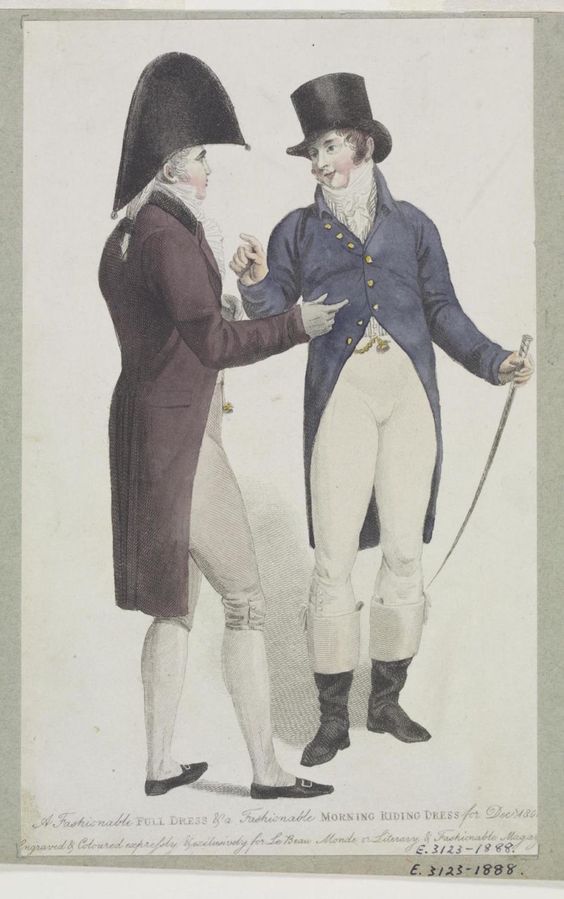

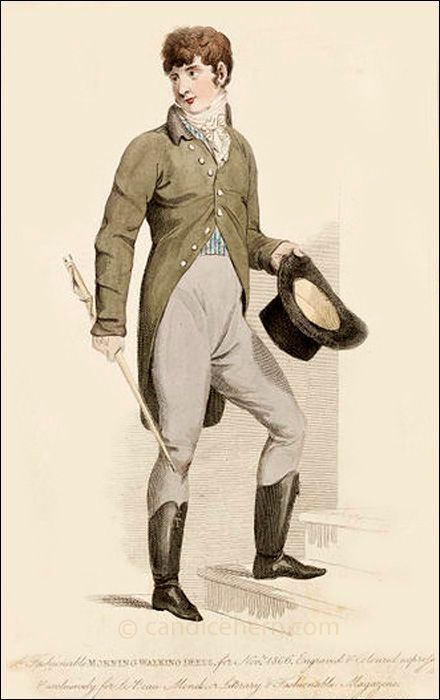

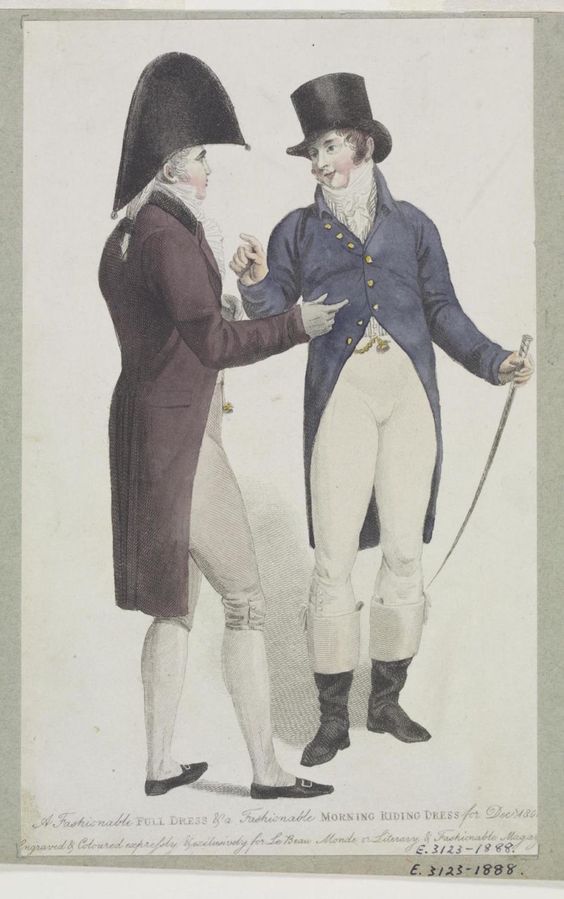

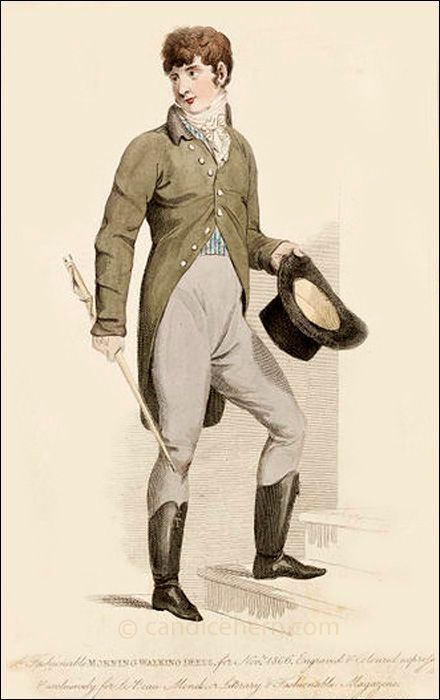

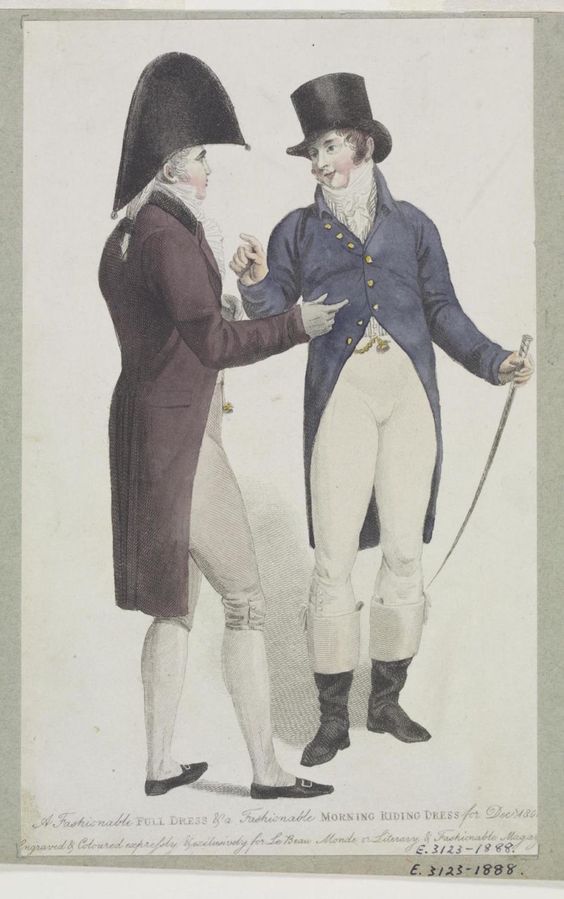

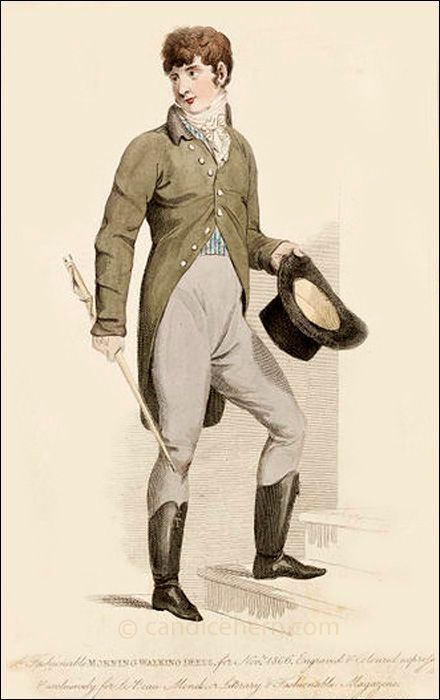

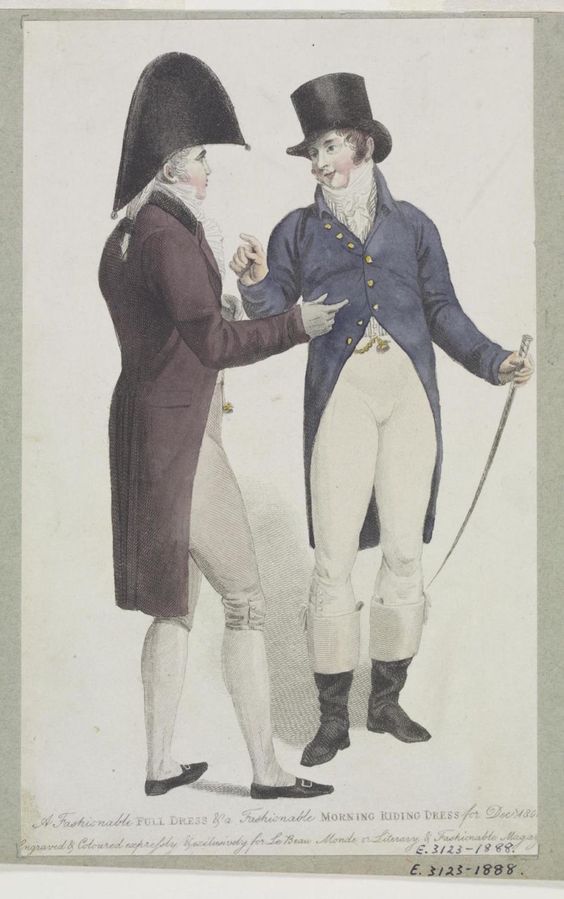

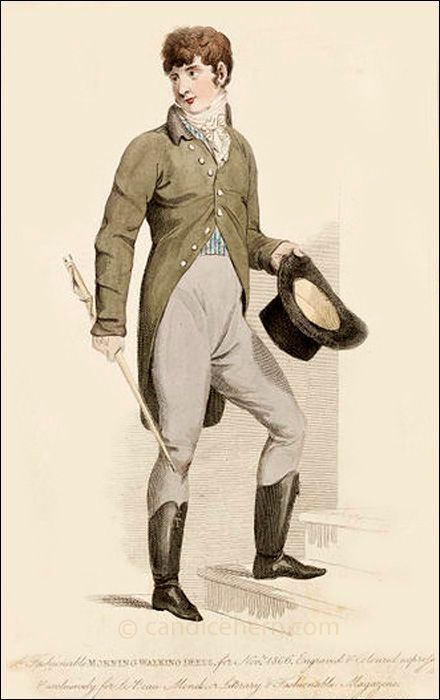

Dress coats were used still in the Regency era not just in court suits but also in morning dress. The cut and silhouette of men's fashion changed after the 1780s, most significantly with the shorter waistcoats. Here's couple of morning riding dresses (they have riding boots) from 1801 and 1806. I envision the feminine men's style as using the fashionable cuts and silhouette of the day, but combining them with the less structured and finer fabrics, patterns, colours and embelishments of pre-revolution styles. In evening wear I think they could wear white, like women, or at least light colours.

Okay, here's finally all my ideas, I had much more of them than I initially thought! It was so much fun to think about an alternative history like this, so thank you very much for your ask! I hope you found this fun or interesting to read at least, but please take my ideas as just my opinion and if any of it contradicts your vision, just ignore it. It's fiction and an alternative universe in addition so you can follow history just as much or little as you like.

Basically, your story sounds very cool, and I wish you good writing!

108 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I just read your analysis of the P&P 2005 costumes. I'm currently in the process of researching Regency-period fashion for fic purposes; I'm writing a f/f story in a slightly alternate Regency world in which on top of regular marriages, parents (especially in the higher classes) could and did arrange for gay marriages for those of their children who wouldn't inherit - the principle being that the parents could set these couples up with a part of the estate that, upon those couple's death, would revert back to the estate to be inherited onwards, and thus not mess with an entailed estate all that much.

Anyway, long story short, my thought was that in these marriages, there would *still* be a masculine and feminine role, just independent of gender - and there would be according fashions. So, for example, a man's three-piece suit for a woman who took the masculine role in a f/f marriage, just cut towards the female figure, and perhaps with other nods towards the wearer's gender too, and similar for a man who took the feminine role in a m/m marriage.

I just wanted to reach out and see what you think of this and see if you'd have as much fun thinking about this as I have!

Thank you for your message, this honestly sounds really cool!! I think it's very interesting idea to come up with reasoning how arranged same sex marriage would work in a Regency class and land ownership system. I absolutely had so much fun thinking about this, maybe too much fun because look at how long this post is :'D You are entirely free to ignore all of this, I just had a lot of ideas, since your story has such an interesting premise. If you any of this catches your fancy, use it however you like!

I think it makes sense that in a very patriarchal and gender essentialist Regency society the couple would be expected to perform heterosexuality even while literally being in a gay marriage. What you described, men's clothing fitted to women's undergarments, is basically what costumes for breeches roles were usually in theater, roles for female actors, usually as a young leading boy. (Reverse roles, male actors playing female characters, usually elder/motherly roles, were just as common.) Another approach could be to use the women's silhouette, skirt with empire waist, but otherwise the clothing is similar to men's fashion. While most women's Regency styles were particularly strongly contrasted with men's styles, there was quite a lot of masculine styles too, which might work for that purpose.

I think the approach that would make most sense depends on how you want the gnc people seen and understood in the althis society of your story. In Regency society cross-dressing, women wearing pants and men wearing skirts, was seen as stepping into the other gender role. Cross-dressing was not acceptable outside theater, and people who did it needed to be stealth. So if you vision them taking the role of the opposite gender fully and not just in their relationship - living as the opposite gender and treated like that gender (for example the gnc women are allowed men's education and gnc men are not etc.) - I think it makes more sense that they would be using similar clothing as the costumes of the cross-dressing roles in theater. In that specific position it would then become acceptable to cross-dress. But if you envision them more in the societal positions of their own/assigned gender, and just embodying some opposite gender roles, especially in their marriage, I think it might make more sense for them to use the basic silhouettes of the fashion of their gender but in style the opposite gender.

So if you're interested, here's some historical styles and some additional ideas that could work as inspiration.

Before Renaissance men and women's fashions were not separate, but they started drifting apart when wearing skirts became unacceptable for men (which I have a whole long post about). However, very quickly women's fashion started to take influence from men's fashion for certain styles. Riding habit was the first one of these masculine styles for women. It originated from 17th century as men's clothing but with a skirt. From very early on men's military uniforms were a huge influence. A distinctive feature compared to other styles is the long trail so when the woman sits on the horse, her legs are not too exposed. Here's some regency examples. First example is from mid 1797-98. The bodice is exactly in the style of men's fashion of the period. Second is from 1808 in a very militaristic style.

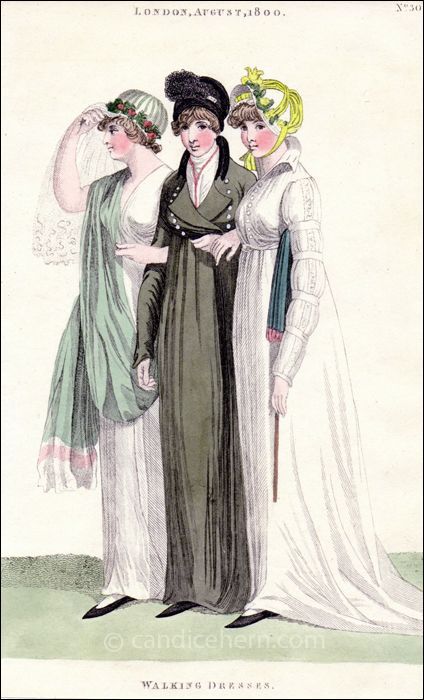

Redingote or pelisse was a long walking dress often in the masculine styles of the riding habit. It was adapted from riding habit to fashionable day wear for outdoors in 1780s. It started as very masculine in line with riding habits, but in 1800s styles without the masculine elements also appeared. Though masculine and military styles were still common. Here's first a redingote from 1800, which follows masculine fashion of the day very closely. The second is from 1810s and has collar from men's fashion and detailing and color are loose references to military styles. The third one is quite military inspired redingote from 1814. It has long train and was probably for carriage rides.

Spencer was a very short casual jacket, modelled after men's fashion again. It became fashionable in 1790s and in the following decades it gained many variations, some not at all masculine in style, and some for formal usage too. Here's very masculine styles as examples, first is from c. 1799, second from c. 1815.

One last trend I'll mention is very short hair imitating Roman men's hairstyles, which became very fashionable for men after the French Revolution, but very similar hair for women became a trend in late 1790s. It was a bold style but for couple of decades it was very popular. I think the woman in the first example above is growing out her Titus cut. There's a little tuft on top of her head, which makes it look like her hair isn't long enough for a bun but secured at the back anyway. Here's couple of actual examples. First is from early 1800s, specific date unknown, showing a slightly longer than usual version of the style. Second is from around the same time, 1798-1805, displaying very well how hair was cut to imitate side burns, which were fashionable for men. The third example from 1809 has the typical cut, where it's very short in the back of the head and little longer and curled in the front.

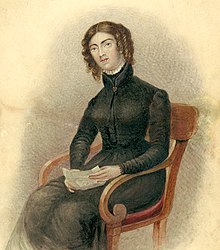

Many Regency sapphics did favour these styles, since they were acceptable ways to present in a more masculine manner. Anne Lister, perhaps the most famous Regency lesbian, presented very masculinely in her portraits. Below her outfit looks like a redingote in this 1822 painting. An infamous upper class Irish sapphic couple, Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, lived together for decades in Whales. Here's an illustrations of them from 1818 in their older age wearing masculine redingotes and sporting Titus hairstyles.

I think in a society where gnc queer people are part of the system, they might have their own slightly different dress codes. For the gnc women/afab people I'm thinking their evening dress might have redingote or spence or perhaps open robe in style of men's evening wear which was black with white cravat (second image below). The open robe could be something like the first image below but fully black, tailored, with large lapels, high collars in the white chemisette and white cravat.

Men's gnc fashion is much harder problem since femininity in men was much less (and still very much seems to be) accepted than masculinity in women. I think it's the old patriarchal superiority of masculinity issue (even if women shouldn't break gender roles at least they are "upgrading", while men would be "downgrading"). I think it might be interesting thought to take inspiration from the styles previous to French Revolution. Regency men's fashion (all Regency fashion really) was result of the French Revolution. I talk more about it in this post, but previously manhood and womanhood had only really been fully available for the upper classes and they were based mostly on displays of wealth. The revolutionaries rejected the aristocratic gender construction and instead created their own. It was based less on class and more on the gender (and racial, but we won't have the time to touch on that here) divide. Aristocratic gender expressions were deemed decadent and the bad kind of feminine. (French Revolution may not have been the origins of the Madonna-whore complex, but they certainly cemented it to the public conscience.) That's how men's Regency fashion was stripped out of colour, detailing and luxurious materials, the overt displays of wealth. New masculine styles were all about evoking militarism, country side and practicality of a working man. Most of it was aesthetic and the class structure remained, but altered heavier in the lines of gender and race/ethnicity. To show you how the fashion was seen, here's couple of satirical cartoons both from 1787 literally calling men wearing the more courtly flamboyant styles women. (First source, second source.)

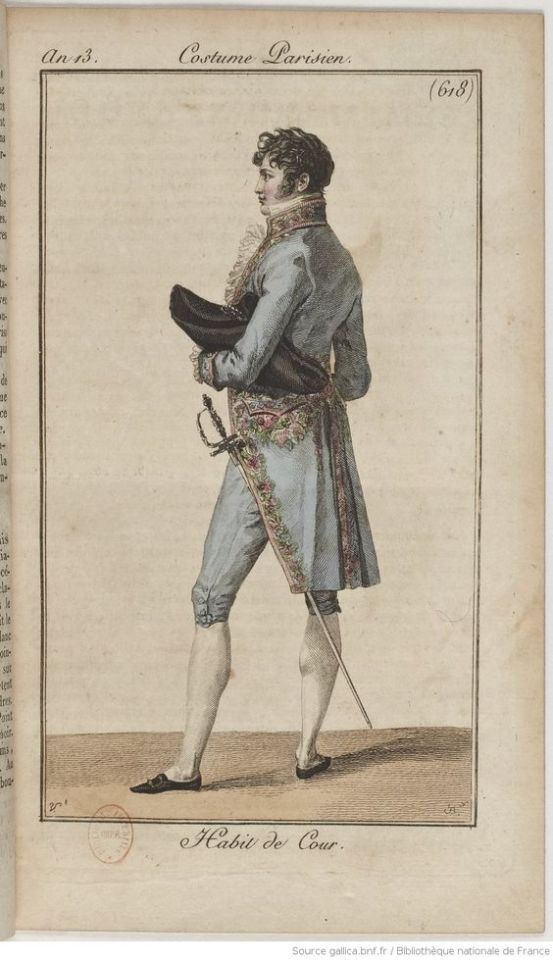

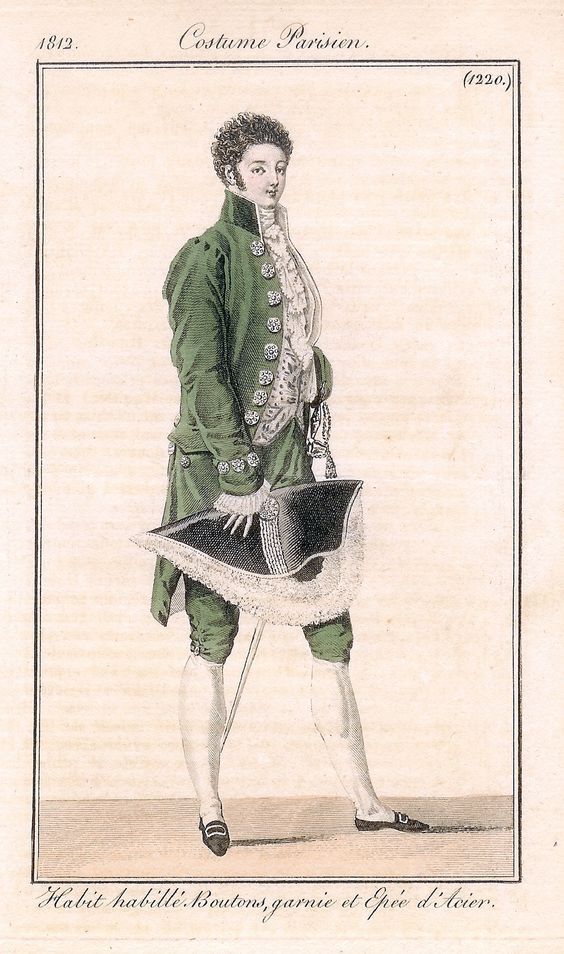

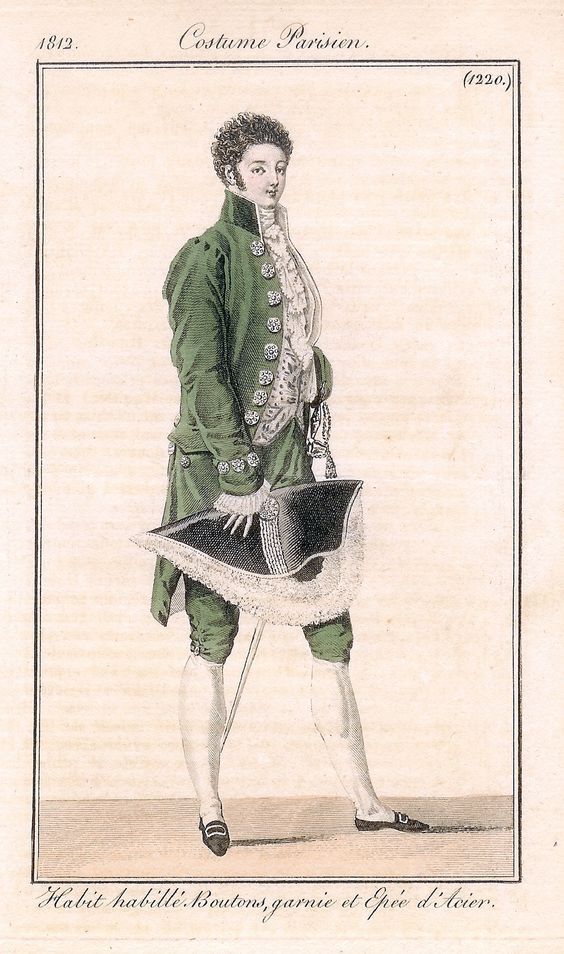

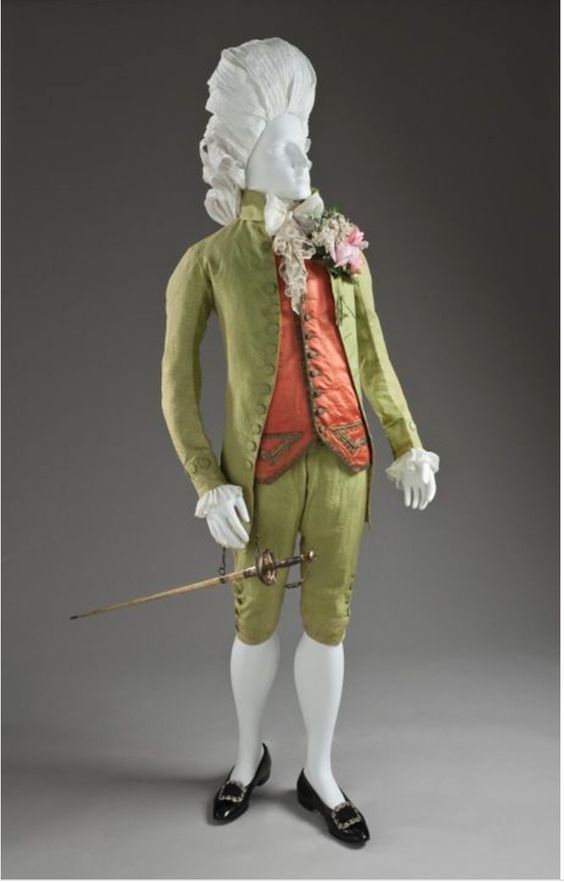

It's not entirely unrealistic that the outdated fashions would remain along the new styles. Courts were resistant to change (especially since the change had anti-monarchist implications) and upheld the outdated dress codes, so court suits were very much continuation of the fashion prior to the revolution (though court suits too started to become increasingly subdued by the 1820s). Here's examples from 1805 and 1813.

In an alternative historical world like this, I think the pre-revolution styles might have kept on and evolved as a more feminine version of the more general men's fashion. Since masculinity had been tied with rural areas and working class, I think the gnc men's style wouldn't have lapels or turned down collars, which originated from working class clothing, but upward collars like in the 18th century dress coats and Regency court suits (maybe downward collars in informal coats, but not lapels). Maybe they would keep on with the long hairstyles where they tie up their hair with a ribbon, though I don't think they would keep powdering the hair as it went out of fashion for women too. Instead they might style the front of the hair similar to women by cutting hair shorter in the front (basically a mullet) and curling the front of it to frame the face. I don't think they would be wearing the loose trousers, which were very strongly working class till the beginning of 1800s, when they started to be accepted as informal wear for upper class men. Though I think pantaloons would become informal part of feminine men's fashion after general men's fashion would start accepting them as formal wear around 1810s. Here's some examples from 1780s, which could be used as inspiration. First is from 1785-1790, second is from 1788 and the third is from c. 1770.

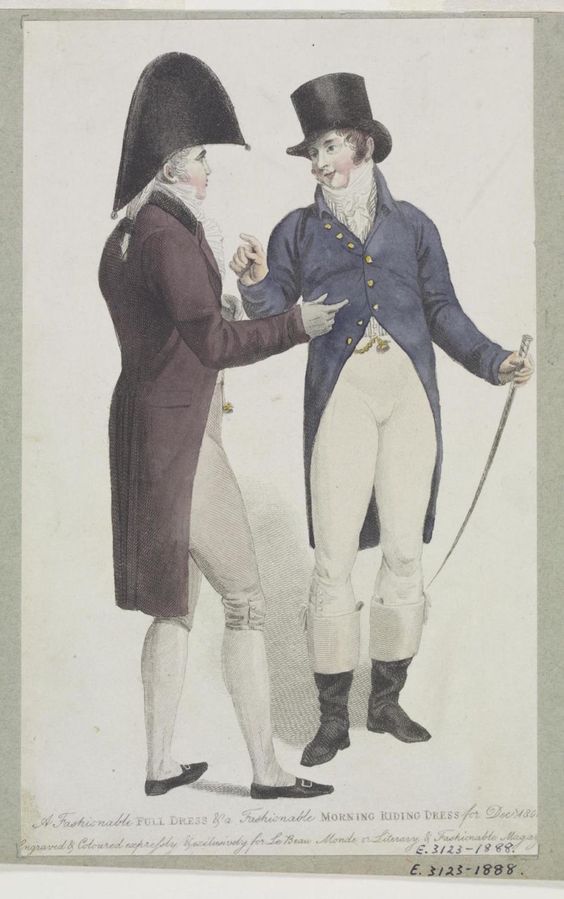

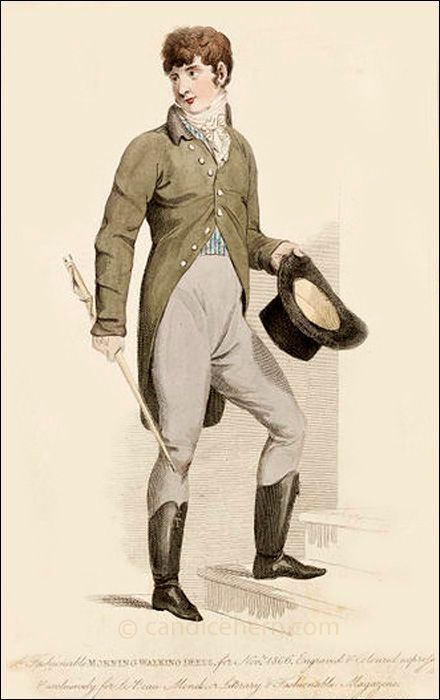

Dress coats were used still in the Regency era not just in court suits but also in morning dress. The cut and silhouette of men's fashion changed after the 1780s, most significantly with the shorter waistcoats. Here's couple of morning riding dresses (they have riding boots) from 1801 and 1806. I envision the feminine men's style as using the fashionable cuts and silhouette of the day, but combining them with the less structured and finer fabrics, patterns, colours and embelishments of pre-revolution styles. In evening wear I think they could wear white, like women, or at least light colours.

Okay, here's finally all my ideas, I had much more of them than I initially thought! It was so much fun to think about an alternative history like this, so thank you very much for your ask! I hope you found this fun or interesting to read at least, but please take my ideas as just my opinion and if any of it contradicts your vision, just ignore it. It's fiction and an alternative universe in addition so you can follow history just as much or little as you like.

Basically, your story sounds very cool, and I wish you good writing!

108 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I just read your analysis of the P&P 2005 costumes. I'm currently in the process of researching Regency-period fashion for fic purposes; I'm writing a f/f story in a slightly alternate Regency world in which on top of regular marriages, parents (especially in the higher classes) could and did arrange for gay marriages for those of their children who wouldn't inherit - the principle being that the parents could set these couples up with a part of the estate that, upon those couple's death, would revert back to the estate to be inherited onwards, and thus not mess with an entailed estate all that much.

Anyway, long story short, my thought was that in these marriages, there would *still* be a masculine and feminine role, just independent of gender - and there would be according fashions. So, for example, a man's three-piece suit for a woman who took the masculine role in a f/f marriage, just cut towards the female figure, and perhaps with other nods towards the wearer's gender too, and similar for a man who took the feminine role in a m/m marriage.

I just wanted to reach out and see what you think of this and see if you'd have as much fun thinking about this as I have!

Thank you for your message, this honestly sounds really cool!! I think it's very interesting idea to come up with reasoning how arranged same sex marriage would work in a Regency class and land ownership system. I absolutely had so much fun thinking about this, maybe too much fun because look at how long this post is :'D You are entirely free to ignore all of this, I just had a lot of ideas, since your story has such an interesting premise. If you any of this catches your fancy, use it however you like!

I think it makes sense that in a very patriarchal and gender essentialist Regency society the couple would be expected to perform heterosexuality even while literally being in a gay marriage. What you described, men's clothing fitted to women's undergarments, is basically what costumes for breeches roles were usually in theater, roles for female actors, usually as a young leading boy. (Reverse roles, male actors playing female characters, usually elder/motherly roles, were just as common.) Another approach could be to use the women's silhouette, skirt with empire waist, but otherwise the clothing is similar to men's fashion. While most women's Regency styles were particularly strongly contrasted with men's styles, there was quite a lot of masculine styles too, which might work for that purpose.

I think the approach that would make most sense depends on how you want the gnc people seen and understood in the althis society of your story. In Regency society cross-dressing, women wearing pants and men wearing skirts, was seen as stepping into the other gender role. Cross-dressing was not acceptable outside theater, and people who did it needed to be stealth. So if you vision them taking the role of the opposite gender fully and not just in their relationship - living as the opposite gender and treated like that gender (for example the gnc women are allowed men's education and gnc men are not etc.) - I think it makes more sense that they would be using similar clothing as the costumes of the cross-dressing roles in theater. In that specific position it would then become acceptable to cross-dress. But if you envision them more in the societal positions of their own/assigned gender, and just embodying some opposite gender roles, especially in their marriage, I think it might make more sense for them to use the basic silhouettes of the fashion of their gender but in style the opposite gender.

So if you're interested, here's some historical styles and some additional ideas that could work as inspiration.

Before Renaissance men and women's fashions were not separate, but they started drifting apart when wearing skirts became unacceptable for men (which I have a whole long post about). However, very quickly women's fashion started to take influence from men's fashion for certain styles. Riding habit was the first one of these masculine styles for women. It originated from 17th century as men's clothing but with a skirt. From very early on men's military uniforms were a huge influence. A distinctive feature compared to other styles is the long trail so when the woman sits on the horse, her legs are not too exposed. Here's some regency examples. First example is from mid 1797-98. The bodice is exactly in the style of men's fashion of the period. Second is from 1808 in a very militaristic style.

Redingote or pelisse was a long walking dress often in the masculine styles of the riding habit. It was adapted from riding habit to fashionable day wear for outdoors in 1780s. It started as very masculine in line with riding habits, but in 1800s styles without the masculine elements also appeared. Though masculine and military styles were still common. Here's first a redingote from 1800, which follows masculine fashion of the day very closely. The second is from 1810s and has collar from men's fashion and detailing and color are loose references to military styles. The third one is quite military inspired redingote from 1814. It has long train and was probably for carriage rides.

Spencer was a very short casual jacket, modelled after men's fashion again. It became fashionable in 1790s and in the following decades it gained many variations, some not at all masculine in style, and some for formal usage too. Here's very masculine styles as examples, first is from c. 1799, second from c. 1815.

One last trend I'll mention is very short hair imitating Roman men's hairstyles, which became very fashionable for men after the French Revolution, but very similar hair for women became a trend in late 1790s. It was a bold style but for couple of decades it was very popular. I think the woman in the first example above is growing out her Titus cut. There's a little tuft on top of her head, which makes it look like her hair isn't long enough for a bun but secured at the back anyway. Here's couple of actual examples. First is from early 1800s, specific date unknown, showing a slightly longer than usual version of the style. Second is from around the same time, 1798-1805, displaying very well how hair was cut to imitate side burns, which were fashionable for men. The third example from 1809 has the typical cut, where it's very short in the back of the head and little longer and curled in the front.

Many Regency sapphics did favour these styles, since they were acceptable ways to present in a more masculine manner. Anne Lister, perhaps the most famous Regency lesbian, presented very masculinely in her portraits. Below her outfit looks like a redingote in this 1822 painting. An infamous upper class Irish sapphic couple, Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, lived together for decades in Whales. Here's an illustrations of them from 1818 in their older age wearing masculine redingotes and sporting Titus hairstyles.

I think in a society where gnc queer people are part of the system, they might have their own slightly different dress codes. For the gnc women/afab people I'm thinking their evening dress might have redingote or spence or perhaps open robe in style of men's evening wear which was black with white cravat (second image below). The open robe could be something like the first image below but fully black, tailored, with large lapels, high collars in the white chemisette and white cravat.

Men's gnc fashion is much harder problem since femininity in men was much less (and still very much seems to be) accepted than masculinity in women. I think it's the old patriarchal superiority of masculinity issue (even if women shouldn't break gender roles at least they are "upgrading", while men would be "downgrading"). I think it might be interesting thought to take inspiration from the styles previous to French Revolution. Regency men's fashion (all Regency fashion really) was result of the French Revolution. I talk more about it in this post, but previously manhood and womanhood had only really been fully available for the upper classes and they were based mostly on displays of wealth. The revolutionaries rejected the aristocratic gender construction and instead created their own. It was based less on class and more on the gender (and racial, but we won't have the time to touch on that here) divide. Aristocratic gender expressions were deemed decadent and the bad kind of feminine. (French Revolution may not have been the origins of the Madonna-whore complex, but they certainly cemented it to the public conscience.) That's how men's Regency fashion was stripped out of colour, detailing and luxurious materials, the overt displays of wealth. New masculine styles were all about evoking militarism, country side and practicality of a working man. Most of it was aesthetic and the class structure remained, but altered heavier in the lines of gender and race/ethnicity. To show you how the fashion was seen, here's couple of satirical cartoons both from 1787 literally calling men wearing the more courtly flamboyant styles women. (First source, second source.)

It's not entirely unrealistic that the outdated fashions would remain along the new styles. Courts were resistant to change (especially since the change had anti-monarchist implications) and upheld the outdated dress codes, so court suits were very much continuation of the fashion prior to the revolution (though court suits too started to become increasingly subdued by the 1820s). Here's examples from 1805 and 1813.

In an alternative historical world like this, I think the pre-revolution styles might have kept on and evolved as a more feminine version of the more general men's fashion. Since masculinity had been tied with rural areas and working class, I think the gnc men's style wouldn't have lapels or turned down collars, which originated from working class clothing, but upward collars like in the 18th century dress coats and Regency court suits (maybe downward collars in informal coats, but not lapels). Maybe they would keep on with the long hairstyles where they tie up their hair with a ribbon, though I don't think they would keep powdering the hair as it went out of fashion for women too. Instead they might style the front of the hair similar to women by cutting hair shorter in the front (basically a mullet) and curling the front of it to frame the face. I don't think they would be wearing the loose trousers, which were very strongly working class till the beginning of 1800s, when they started to be accepted as informal wear for upper class men. Though I think pantaloons would become informal part of feminine men's fashion after general men's fashion would start accepting them as formal wear around 1810s. Here's some examples from 1780s, which could be used as inspiration. First is from 1785-1790, second is from 1788 and the third is from c. 1770.

Dress coats were used still in the Regency era not just in court suits but also in morning dress. The cut and silhouette of men's fashion changed after the 1780s, most significantly with the shorter waistcoats. Here's couple of morning riding dresses (they have riding boots) from 1801 and 1806. I envision the feminine men's style as using the fashionable cuts and silhouette of the day, but combining them with the less structured and finer fabrics, patterns, colours and embelishments of pre-revolution styles. In evening wear I think they could wear white, like women, or at least light colours.

Okay, here's finally all my ideas, I had much more of them than I initially thought! It was so much fun to think about an alternative history like this, so thank you very much for your ask! I hope you found this fun or interesting to read at least, but please take my ideas as just my opinion and if any of it contradicts your vision, just ignore it. It's fiction and an alternative universe in addition so you can follow history just as much or little as you like.

Basically, your story sounds very cool, and I wish you good writing!

108 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I just read your analysis of the P&P 2005 costumes. I'm currently in the process of researching Regency-period fashion for fic purposes; I'm writing a f/f story in a slightly alternate Regency world in which on top of regular marriages, parents (especially in the higher classes) could and did arrange for gay marriages for those of their children who wouldn't inherit - the principle being that the parents could set these couples up with a part of the estate that, upon those couple's death, would revert back to the estate to be inherited onwards, and thus not mess with an entailed estate all that much.

Anyway, long story short, my thought was that in these marriages, there would *still* be a masculine and feminine role, just independent of gender - and there would be according fashions. So, for example, a man's three-piece suit for a woman who took the masculine role in a f/f marriage, just cut towards the female figure, and perhaps with other nods towards the wearer's gender too, and similar for a man who took the feminine role in a m/m marriage.

I just wanted to reach out and see what you think of this and see if you'd have as much fun thinking about this as I have!

Thank you for your message, this honestly sounds really cool!! I think it's very interesting idea to come up with reasoning how arranged same sex marriage would work in a Regency class and land ownership system. I absolutely had so much fun thinking about this, maybe too much fun because look at how long this post is :'D You are entirely free to ignore all of this, I just had a lot of ideas, since your story has such an interesting premise. If you any of this catches your fancy, use it however you like!

I think it makes sense that in a very patriarchal and gender essentialist Regency society the couple would be expected to perform heterosexuality even while literally being in a gay marriage. What you described, men's clothing fitted to women's undergarments, is basically what costumes for breeches roles were usually in theater, roles for female actors, usually as a young leading boy. (Reverse roles, male actors playing female characters, usually elder/motherly roles, were just as common.) Another approach could be to use the women's silhouette, skirt with empire waist, but otherwise the clothing is similar to men's fashion. While most women's Regency styles were particularly strongly contrasted with men's styles, there was quite a lot of masculine styles too, which might work for that purpose.

I think the approach that would make most sense depends on how you want the gnc people seen and understood in the althis society of your story. In Regency society cross-dressing, women wearing pants and men wearing skirts, was seen as stepping into the other gender role. Cross-dressing was not acceptable outside theater, and people who did it needed to be stealth. So if you vision them taking the role of the opposite gender fully and not just in their relationship - living as the opposite gender and treated like that gender (for example the gnc women are allowed men's education and gnc men are not etc.) - I think it makes more sense that they would be using similar clothing as the costumes of the cross-dressing roles in theater. In that specific position it would then become acceptable to cross-dress. But if you envision them more in the societal positions of their own/assigned gender, and just embodying some opposite gender roles, especially in their marriage, I think it might make more sense for them to use the basic silhouettes of the fashion of their gender but in style the opposite gender.

So if you're interested, here's some historical styles and some additional ideas that could work as inspiration.

Before Renaissance men and women's fashions were not separate, but they started drifting apart when wearing skirts became unacceptable for men (which I have a whole long post about). However, very quickly women's fashion started to take influence from men's fashion for certain styles. Riding habit was the first one of these masculine styles for women. It originated from 17th century as men's clothing but with a skirt. From very early on men's military uniforms were a huge influence. A distinctive feature compared to other styles is the long trail so when the woman sits on the horse, her legs are not too exposed. Here's some regency examples. First example is from mid 1797-98. The bodice is exactly in the style of men's fashion of the period. Second is from 1808 in a very militaristic style.

Redingote or pelisse was a long walking dress often in the masculine styles of the riding habit. It was adapted from riding habit to fashionable day wear for outdoors in 1780s. It started as very masculine in line with riding habits, but in 1800s styles without the masculine elements also appeared. Though masculine and military styles were still common. Here's first a redingote from 1800, which follows masculine fashion of the day very closely. The second is from 1810s and has collar from men's fashion and detailing and color are loose references to military styles. The third one is quite military inspired redingote from 1814. It has long train and was probably for carriage rides.

Spencer was a very short casual jacket, modelled after men's fashion again. It became fashionable in 1790s and in the following decades it gained many variations, some not at all masculine in style, and some for formal usage too. Here's very masculine styles as examples, first is from c. 1799, second from c. 1815.

One last trend I'll mention is very short hair imitating Roman men's hairstyles, which became very fashionable for men after the French Revolution, but very similar hair for women became a trend in late 1790s. It was a bold style but for couple of decades it was very popular. I think the woman in the first example above is growing out her Titus cut. There's a little tuft on top of her head, which makes it look like her hair isn't long enough for a bun but secured at the back anyway. Here's couple of actual examples. First is from early 1800s, specific date unknown, showing a slightly longer than usual version of the style. Second is from around the same time, 1798-1805, displaying very well how hair was cut to imitate side burns, which were fashionable for men. The third example from 1809 has the typical cut, where it's very short in the back of the head and little longer and curled in the front.

Many Regency sapphics did favour these styles, since they were acceptable ways to present in a more masculine manner. Anne Lister, perhaps the most famous Regency lesbian, presented very masculinely in her portraits. Below her outfit looks like a redingote in this 1822 painting. An infamous upper class Irish sapphic couple, Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, lived together for decades in Whales. Here's an illustrations of them from 1818 in their older age wearing masculine redingotes and sporting Titus hairstyles.

I think in a society where gnc queer people are part of the system, they might have their own slightly different dress codes. For the gnc women/afab people I'm thinking their evening dress might have redingote or spence or perhaps open robe in style of men's evening wear which was black with white cravat (second image below). The open robe could be something like the first image below but fully black, tailored, with large lapels, high collars in the white chemisette and white cravat.

Men's gnc fashion is much harder problem since femininity in men was much less (and still very much seems to be) accepted than masculinity in women. I think it's the old patriarchal superiority of masculinity issue (even if women shouldn't break gender roles at least they are "upgrading", while men would be "downgrading"). I think it might be interesting thought to take inspiration from the styles previous to French Revolution. Regency men's fashion (all Regency fashion really) was result of the French Revolution. I talk more about it in this post, but previously manhood and womanhood had only really been fully available for the upper classes and they were based mostly on displays of wealth. The revolutionaries rejected the aristocratic gender construction and instead created their own. It was based less on class and more on the gender (and racial, but we won't have the time to touch on that here) divide. Aristocratic gender expressions were deemed decadent and the bad kind of feminine. (French Revolution may not have been the origins of the Madonna-whore complex, but they certainly cemented it to the public conscience.) That's how men's Regency fashion was stripped out of colour, detailing and luxurious materials, the overt displays of wealth. New masculine styles were all about evoking militarism, country side and practicality of a working man. Most of it was aesthetic and the class structure remained, but altered heavier in the lines of gender and race/ethnicity. To show you how the fashion was seen, here's couple of satirical cartoons both from 1787 literally calling men wearing the more courtly flamboyant styles women. (First source, second source.)

It's not entirely unrealistic that the outdated fashions would remain along the new styles. Courts were resistant to change (especially since the change had anti-monarchist implications) and upheld the outdated dress codes, so court suits were very much continuation of the fashion prior to the revolution (though court suits too started to become increasingly subdued by the 1820s). Here's examples from 1805 and 1813.

In an alternative historical world like this, I think the pre-revolution styles might have kept on and evolved as a more feminine version of the more general men's fashion. Since masculinity had been tied with rural areas and working class, I think the gnc men's style wouldn't have lapels or turned down collars, which originated from working class clothing, but upward collars like in the 18th century dress coats and Regency court suits (maybe downward collars in informal coats, but not lapels). Maybe they would keep on with the long hairstyles where they tie up their hair with a ribbon, though I don't think they would keep powdering the hair as it went out of fashion for women too. Instead they might style the front of the hair similar to women by cutting hair shorter in the front (basically a mullet) and curling the front of it to frame the face. I don't think they would be wearing the loose trousers, which were very strongly working class till the beginning of 1800s, when they started to be accepted as informal wear for upper class men. Though I think pantaloons would become informal part of feminine men's fashion after general men's fashion would start accepting them as formal wear around 1810s. Here's some examples from 1780s, which could be used as inspiration. First is from 1785-1790, second is from 1788 and the third is from c. 1770.

Dress coats were used still in the Regency era not just in court suits but also in morning dress. The cut and silhouette of men's fashion changed after the 1780s, most significantly with the shorter waistcoats. Here's couple of morning riding dresses (they have riding boots) from 1801 and 1806. I envision the feminine men's style as using the fashionable cuts and silhouette of the day, but combining them with the less structured and finer fabrics, patterns, colours and embelishments of pre-revolution styles. In evening wear I think they could wear white, like women, or at least light colours.

Okay, here's finally all my ideas, I had much more of them than I initially thought! It was so much fun to think about an alternative history like this, so thank you very much for your ask! I hope you found this fun or interesting to read at least, but please take my ideas as just my opinion and if any of it contradicts your vision, just ignore it. It's fiction and an alternative universe in addition so you can follow history just as much or little as you like.

Basically, your story sounds very cool, and I wish you good writing!

108 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I just read your analysis of the P&P 2005 costumes. I'm currently in the process of researching Regency-period fashion for fic purposes; I'm writing a f/f story in a slightly alternate Regency world in which on top of regular marriages, parents (especially in the higher classes) could and did arrange for gay marriages for those of their children who wouldn't inherit - the principle being that the parents could set these couples up with a part of the estate that, upon those couple's death, would revert back to the estate to be inherited onwards, and thus not mess with an entailed estate all that much.

Anyway, long story short, my thought was that in these marriages, there would *still* be a masculine and feminine role, just independent of gender - and there would be according fashions. So, for example, a man's three-piece suit for a woman who took the masculine role in a f/f marriage, just cut towards the female figure, and perhaps with other nods towards the wearer's gender too, and similar for a man who took the feminine role in a m/m marriage.

I just wanted to reach out and see what you think of this and see if you'd have as much fun thinking about this as I have!

Thank you for your message, this honestly sounds really cool!! I think it's very interesting idea to come up with reasoning how arranged same sex marriage would work in a Regency class and land ownership system. I absolutely had so much fun thinking about this, maybe too much fun because look at how long this post is :'D You are entirely free to ignore all of this, I just had a lot of ideas, since your story has such an interesting premise. If you any of this catches your fancy, use it however you like!

I think it makes sense that in a very patriarchal and gender essentialist Regency society the couple would be expected to perform heterosexuality even while literally being in a gay marriage. What you described, men's clothing fitted to women's undergarments, is basically what costumes for breeches roles were usually in theater, roles for female actors, usually as a young leading boy. (Reverse roles, male actors playing female characters, usually elder/motherly roles, were just as common.) Another approach could be to use the women's silhouette, skirt with empire waist, but otherwise the clothing is similar to men's fashion. While most women's Regency styles were particularly strongly contrasted with men's styles, there was quite a lot of masculine styles too, which might work for that purpose.

I think the approach that would make most sense depends on how you want the gnc people seen and understood in the althis society of your story. In Regency society cross-dressing, women wearing pants and men wearing skirts, was seen as stepping into the other gender role. Cross-dressing was not acceptable outside theater, and people who did it needed to be stealth. So if you vision them taking the role of the opposite gender fully and not just in their relationship - living as the opposite gender and treated like that gender (for example the gnc women are allowed men's education and gnc men are not etc.) - I think it makes more sense that they would be using similar clothing as the costumes of the cross-dressing roles in theater. In that specific position it would then become acceptable to cross-dress. But if you envision them more in the societal positions of their own/assigned gender, and just embodying some opposite gender roles, especially in their marriage, I think it might make more sense for them to use the basic silhouettes of the fashion of their gender but in style the opposite gender.

So if you're interested, here's some historical styles and some additional ideas that could work as inspiration.

Before Renaissance men and women's fashions were not separate, but they started drifting apart when wearing skirts became unacceptable for men (which I have a whole long post about). However, very quickly women's fashion started to take influence from men's fashion for certain styles. Riding habit was the first one of these masculine styles for women. It originated from 17th century as men's clothing but with a skirt. From very early on men's military uniforms were a huge influence. A distinctive feature compared to other styles is the long trail so when the woman sits on the horse, her legs are not too exposed. Here's some regency examples. First example is from mid 1797-98. The bodice is exactly in the style of men's fashion of the period. Second is from 1808 in a very militaristic style.

Redingote or pelisse was a long walking dress often in the masculine styles of the riding habit. It was adapted from riding habit to fashionable day wear for outdoors in 1780s. It started as very masculine in line with riding habits, but in 1800s styles without the masculine elements also appeared. Though masculine and military styles were still common. Here's first a redingote from 1800, which follows masculine fashion of the day very closely. The second is from 1810s and has collar from men's fashion and detailing and color are loose references to military styles. The third one is quite military inspired redingote from 1814. It has long train and was probably for carriage rides.

Spencer was a very short casual jacket, modelled after men's fashion again. It became fashionable in 1790s and in the following decades it gained many variations, some not at all masculine in style, and some for formal usage too. Here's very masculine styles as examples, first is from c. 1799, second from c. 1815.

One last trend I'll mention is very short hair imitating Roman men's hairstyles, which became very fashionable for men after the French Revolution, but very similar hair for women became a trend in late 1790s. It was a bold style but for couple of decades it was very popular. I think the woman in the first example above is growing out her Titus cut. There's a little tuft on top of her head, which makes it look like her hair isn't long enough for a bun but secured at the back anyway. Here's couple of actual examples. First is from early 1800s, specific date unknown, showing a slightly longer than usual version of the style. Second is from around the same time, 1798-1805, displaying very well how hair was cut to imitate side burns, which were fashionable for men. The third example from 1809 has the typical cut, where it's very short in the back of the head and little longer and curled in the front.

Many Regency sapphics did favour these styles, since they were acceptable ways to present in a more masculine manner. Anne Lister, perhaps the most famous Regency lesbian, presented very masculinely in her portraits. Below her outfit looks like a redingote in this 1822 painting. An infamous upper class Irish sapphic couple, Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, lived together for decades in Whales. Here's an illustrations of them from 1818 in their older age wearing masculine redingotes and sporting Titus hairstyles.

I think in a society where that's part of the system, they might have their own slightly different dress codes. For the gnc women/afab people I'm thinking their evening dress might have redingote or spence or perhaps open robe in style of men's evening wear which was black with white cravat (second image below). The open robe could be something like the first image below but fully black, tailored, with large lapels, high collars in the white chemisette and white cravat.

Men's gnc fashion is much harder problem since femininity in men was much less (and still very much seems to be) accepted than masculinity in women. I think it's the old patriarchal superiority of masculinity issue (even if women shouldn't break gender roles at least they are "upgrading", while men would be "downgrading"). I think it might be interesting thought to take inspiration from the styles previous to French Revolution. Regency men's fashion (all Regency fashion really) was result of the French Revolution. I talk more about it in this post, but previously manhood and womanhood had only really been fully available for the upper classes and they were based mostly on displays of wealth. The revolutionaries rejected the aristocratic gender construction and instead created their own. It was based less on class and more on the gender (and racial, but we won't have the time to touch on that here) divide. Aristocratic gender expressions were deemed decadent and the bad kind of feminine. (French Revolution may not have been the origins of the Madonna-whore complex, but they certainly cemented it to the public conscience.) That's how men's Regency fashion was stripped out of colour, detailing and luxurious materials, the overt displays of wealth. New masculine styles were all about evoking militarism, country side and practicality of a working man. Most of it was aesthetic and the class structure remained, but altered heavier in the lines of gender and race/ethnicity. To show you how the fashion was seen, here's couple of satirical cartoons both from 1787 literally calling men wearing the more courtly flamboyant styles women. (First source, second source.)

It's not entirely unrealistic that the outdated fashions would remain along the new styles. Courts were resistant to change (especially since the change had anti-monarchist implications) and upheld the outdated dress codes, so court suits were very much continuation of the fashion prior to the revolution (though court suits too started to become increasingly subdued by the 1820s). Here's examples from 1805 and 1813.

In an alternative historical world like this, I think the pre-revolution styles might have kept on and evolved as a more feminine version of the more general men's fashion. Since masculinity had been tied with rural areas and working class, I think the gnc men's style wouldn't have lapels or turned down collars, which originated from working class clothing, but upward collars like in the 18th century dress coats and Regency court suits (maybe downward collars in informal coats, but not lapels). Maybe they would keep on with the long hairstyles where they tie up their hair with a ribbon, though I don't think they would keep powdering the hair as it went out of fashion for women too. Instead they might style the front of the hair similar to women by cutting hair shorter in the front (basically a mullet) and curling the front of it to frame the face. I don't think they would be wearing the loose trousers, which were very strongly working class till the beginning of 1800s, when they started to be accepted as informal wear for upper class men. Though I think pantaloons would become informal part of feminine men's fashion after general men's fashion would start accepting them as formal wear around 1810s. Here's some examples from 1780s, which could be used as inspiration. First is from 1785-1790, second is from 1788 and the third is from c. 1770.

Dress coats were used still in the Regency era not just in court suits but also in morning dress. The cut and silhouette of men's fashion changed after the 1780s, most significantly with the shorter waistcoats. Here's couple of morning riding dresses (they have riding boots) from 1801 and 1806. I envision the feminine men's style as using the fashionable cuts and silhouette of the day, but combining them with the less structured and finer fabrics, patterns, colours and embelishments of pre-revolution styles. In evening wear I think they could wear white, like women, or at least light colours.

Okay, here's finally all my ideas, I had much more of them than I initially thought! It was so much fun to think about an alternative history like this, so thank you very much for your ask! I hope you found this fun or interesting to read at least, but please take my ideas as just my opinion and if any of it contradicts your vision, just ignore it. It's fiction and an alternative universe in addition so you can follow history just as much or little as you like.

Basically, your story sounds very cool, and I wish you good writing!

#embarrasing!!#i forgot to link the post about how men stopped wearing skirts#it's like 'i have a whole long post about but i'm not going to tell you which post lool'#amazing#now it's there

108 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I just read your analysis of the P&P 2005 costumes. I'm currently in the process of researching Regency-period fashion for fic purposes; I'm writing a f/f story in a slightly alternate Regency world in which on top of regular marriages, parents (especially in the higher classes) could and did arrange for gay marriages for those of their children who wouldn't inherit - the principle being that the parents could set these couples up with a part of the estate that, upon those couple's death, would revert back to the estate to be inherited onwards, and thus not mess with an entailed estate all that much.

Anyway, long story short, my thought was that in these marriages, there would *still* be a masculine and feminine role, just independent of gender - and there would be according fashions. So, for example, a man's three-piece suit for a woman who took the masculine role in a f/f marriage, just cut towards the female figure, and perhaps with other nods towards the wearer's gender too, and similar for a man who took the feminine role in a m/m marriage.

I just wanted to reach out and see what you think of this and see if you'd have as much fun thinking about this as I have!

Thank you for your message, this honestly sounds really cool!! I think it's very interesting idea to come up with reasoning how arranged same sex marriage would work in a Regency class and land ownership system. I absolutely had so much fun thinking about this, maybe too much fun because look at how long this post is :'D You are entirely free to ignore all of this, I just had a lot of ideas, since your story has such an interesting premise. If you any of this catches your fancy, use it however you like!

I think it makes sense that in a very patriarchal and gender essentialist Regency society the couple would be expected to perform heterosexuality even while literally being in a gay marriage. What you described, men's clothing fitted to women's undergarments, is basically what costumes for breeches roles were usually in theater, roles for female actors, usually as a young leading boy. (Reverse roles, male actors playing female characters, usually elder/motherly roles, were just as common.) Another approach could be to use the women's silhouette, skirt with empire waist, but otherwise the clothing is similar to men's fashion. While most women's Regency styles were particularly strongly contrasted with men's styles, there was quite a lot of masculine styles too, which might work for that purpose.

I think the approach that would make most sense depends on how you want the gnc people seen and understood in the althis society of your story. In Regency society cross-dressing, women wearing pants and men wearing skirts, was seen as stepping into the other gender role. Cross-dressing was not acceptable outside theater, and people who did it needed to be stealth. So if you vision them taking the role of the opposite gender fully and not just in their relationship - living as the opposite gender and treated like that gender (for example the gnc women are allowed men's education and gnc men are not etc.) - I think it makes more sense that they would be using similar clothing as the costumes of the cross-dressing roles in theater. In that specific position it would then become acceptable to cross-dress. But if you envision them more in the societal positions of their own/assigned gender, and just embodying some opposite gender roles, especially in their marriage, I think it might make more sense for them to use the basic silhouettes of the fashion of their gender but in style the opposite gender.

So if you're interested, here's some historical styles and some additional ideas that could work as inspiration.

Before Renaissance men and women's fashions were not separate, but they started drifting apart when wearing skirts became unacceptable for men (which I have a whole long post about). However, very quickly women's fashion started to take influence from men's fashion for certain styles. Riding habit was the first one of these masculine styles for women. It originated from 17th century as men's clothing but with a skirt. From very early on men's military uniforms were a huge influence. A distinctive feature compared to other styles is the long trail so when the woman sits on the horse, her legs are not too exposed. Here's some regency examples. First example is from mid 1797-98. The bodice is exactly in the style of men's fashion of the period. Second is from 1808 in a very militaristic style.

Redingote or pelisse was a long walking dress often in the masculine styles of the riding habit. It was adapted from riding habit to fashionable day wear for outdoors in 1780s. It started as very masculine in line with riding habits, but in 1800s styles without the masculine elements also appeared. Though masculine and military styles were still common. Here's first a redingote from 1800, which follows masculine fashion of the day very closely. The second is from 1810s and has collar from men's fashion and detailing and color are loose references to military styles. The third one is quite military inspired redingote from 1814. It has long train and was probably for carriage rides.

Spencer was a very short casual jacket, modelled after men's fashion again. It became fashionable in 1790s and in the following decades it gained many variations, some not at all masculine in style, and some for formal usage too. Here's very masculine styles as examples, first is from c. 1799, second from c. 1815.

One last trend I'll mention is very short hair imitating Roman men's hairstyles, which became very fashionable for men after the French Revolution, but very similar hair for women became a trend in late 1790s. It was a bold style but for couple of decades it was very popular. I think the woman in the first example above is growing out her Titus cut. There's a little tuft on top of her head, which makes it look like her hair isn't long enough for a bun but secured at the back anyway. Here's couple of actual examples. First is from early 1800s, specific date unknown, showing a slightly longer than usual version of the style. Second is from around the same time, 1798-1805, displaying very well how hair was cut to imitate side burns, which were fashionable for men. The third example from 1809 has the typical cut, where it's very short in the back of the head and little longer and curled in the front.

Many Regency sapphics did favour these styles, since they were acceptable ways to present in a more masculine manner. Anne Lister, perhaps the most famous Regency lesbian, presented very masculinely in her portraits. Below her outfit looks like a redingote in this 1822 painting. An infamous upper class Irish sapphic couple, Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, lived together for decades in Whales. Here's an illustrations of them from 1818 in their older age wearing masculine redingotes and sporting Titus hairstyles.

I think in a society where gnc queer people are part of the system, they might have their own slightly different dress codes. For the gnc women/afab people I'm thinking their evening dress might have redingote or spence or perhaps open robe in style of men's evening wear which was black with white cravat (second image below). The open robe could be something like the first image below but fully black, tailored, with large lapels, high collars in the white chemisette and white cravat.

Men's gnc fashion is much harder problem since femininity in men was much less (and still very much seems to be) accepted than masculinity in women. I think it's the old patriarchal superiority of masculinity issue (even if women shouldn't break gender roles at least they are "upgrading", while men would be "downgrading"). I think it might be interesting thought to take inspiration from the styles previous to French Revolution. Regency men's fashion (all Regency fashion really) was result of the French Revolution. I talk more about it in this post, but previously manhood and womanhood had only really been fully available for the upper classes and they were based mostly on displays of wealth. The revolutionaries rejected the aristocratic gender construction and instead created their own. It was based less on class and more on the gender (and racial, but we won't have the time to touch on that here) divide. Aristocratic gender expressions were deemed decadent and the bad kind of feminine. (French Revolution may not have been the origins of the Madonna-whore complex, but they certainly cemented it to the public conscience.) That's how men's Regency fashion was stripped out of colour, detailing and luxurious materials, the overt displays of wealth. New masculine styles were all about evoking militarism, country side and practicality of a working man. Most of it was aesthetic and the class structure remained, but altered heavier in the lines of gender and race/ethnicity. To show you how the fashion was seen, here's couple of satirical cartoons both from 1787 literally calling men wearing the more courtly flamboyant styles women. (First source, second source.)

It's not entirely unrealistic that the outdated fashions would remain along the new styles. Courts were resistant to change (especially since the change had anti-monarchist implications) and upheld the outdated dress codes, so court suits were very much continuation of the fashion prior to the revolution (though court suits too started to become increasingly subdued by the 1820s). Here's examples from 1805 and 1813.

In an alternative historical world like this, I think the pre-revolution styles might have kept on and evolved as a more feminine version of the more general men's fashion. Since masculinity had been tied with rural areas and working class, I think the gnc men's style wouldn't have lapels or turned down collars, which originated from working class clothing, but upward collars like in the 18th century dress coats and Regency court suits (maybe downward collars in informal coats, but not lapels). Maybe they would keep on with the long hairstyles where they tie up their hair with a ribbon, though I don't think they would keep powdering the hair as it went out of fashion for women too. Instead they might style the front of the hair similar to women by cutting hair shorter in the front (basically a mullet) and curling the front of it to frame the face. I don't think they would be wearing the loose trousers, which were very strongly working class till the beginning of 1800s, when they started to be accepted as informal wear for upper class men. Though I think pantaloons would become informal part of feminine men's fashion after general men's fashion would start accepting them as formal wear around 1810s. Here's some examples from 1780s, which could be used as inspiration. First is from 1785-1790, second is from 1788 and the third is from c. 1770.

Dress coats were used still in the Regency era not just in court suits but also in morning dress. The cut and silhouette of men's fashion changed after the 1780s, most significantly with the shorter waistcoats. Here's couple of morning riding dresses (they have riding boots) from 1801 and 1806. I envision the feminine men's style as using the fashionable cuts and silhouette of the day, but combining them with the less structured and finer fabrics, patterns, colours and embelishments of pre-revolution styles. In evening wear I think they could wear white, like women, or at least light colours.

Okay, here's finally all my ideas, I had much more of them than I initially thought! It was so much fun to think about an alternative history like this, so thank you very much for your ask! I hope you found this fun or interesting to read at least, but please take my ideas as just my opinion and if any of it contradicts your vision, just ignore it. It's fiction and an alternative universe in addition so you can follow history just as much or little as you like.

Basically, your story sounds very cool, and I wish you good writing!

#historical fashion#fashion history#history#fashion#historical costuming#dress history#extant garment#costuming#regency fashion#fashion plate#painting#answers#queer history

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Period dramas dresses tournament: Grey/Silver dresses Round 2- Group A: Elizabeth I, Mary queen of Scots (pics set) vs Milady De Winter, The three musketeers (pics set)

Propaganda for Milady's dress

#vote for milady's campy 1630s dress!!!!#it has Sleeves curly mullet fun silhouette and period accurate tits out#if you're not convinced check the propaganda link#it's so much more fun and interesting than elizabeth's dress

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://t.co/tQNM37KsB0

111K notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve seen this GFM be endorsed by multiple Palestinians on Instagram - it is to help two craftspeople and their families to escape Gaza into Egypt. They had initially denied requests from people to offer money as it felt useless in the situation, but two are now looking to evacuate. Preserving traditional Palestinian crafts in the face of genocide is vital, but I’ll let the description of the fundraiser explain better than I could.

6K notes

·

View notes

Note

Borderline begging you to not erase the gender non conformity of historical women by applying contemporary lenses of gender roles to them. Gender non conforming women existed then and still exist now. Wearing “men’s clothing” does not make me less of a woman and it’s incredibly insulting to see people in 2024 call women “they” and “he” because they wrote extensively about the misogyny they faced on a daily basis and chose to address and protect against by disguising their female form. Clothing does not a gender make—social roles do. Let’s respect historical women by referring to them correctly—not assuming what they would like to be called these days when we have long since dismissed European invert theory.

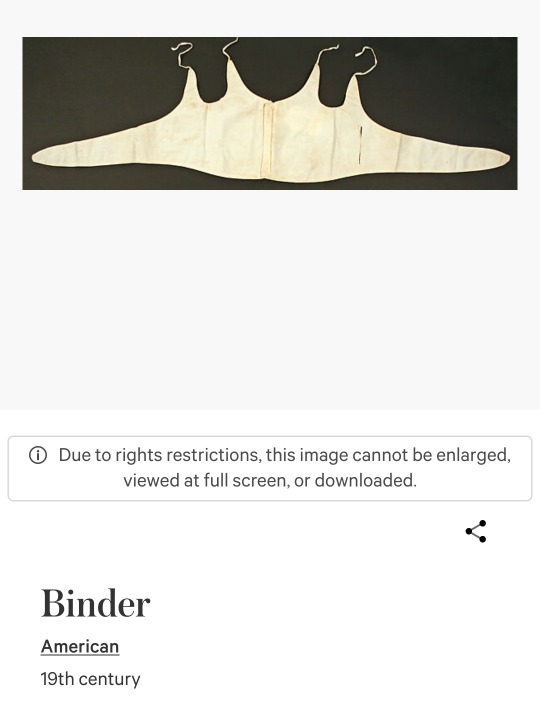

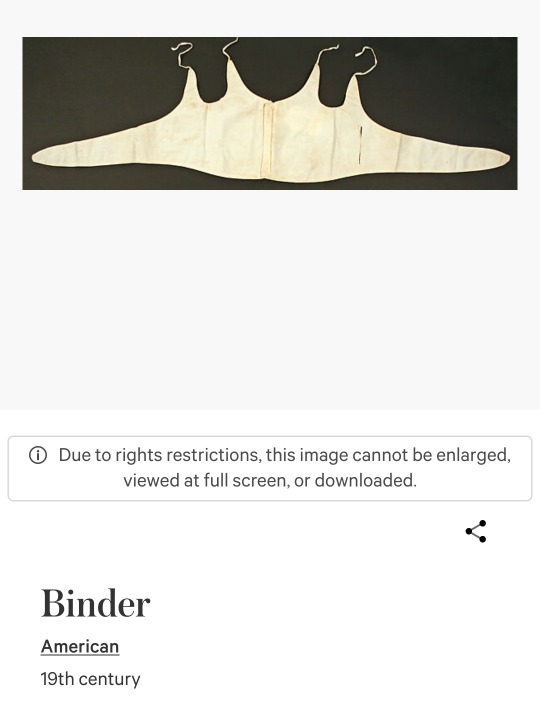

I'm assuming you are referring to that historical binder post and specifically this part:

Westner was also buried in men's clothing by their own request.

Firstly, I didn't call Ella Westner "he", not sure why you are implying that. I haven't read much about Westner, but I did try to look quickly if we have any record or second hand information of them talking or writing about their gender. I didn't find it, so I don't know what would be the correct way to refer to them. I referred to them with "them" since that is the pronoun in English language when you don't know someone's gender. By all means if you have any evidence to share how they liked to be referred, do share.

This is for all intents and purposes the same ask I got after my Julie d'Aubigny post so I'm going to link my response here (and the answer to the follow up ask) instead of rehashing the same points all over again. But I will rehash couple of main points since it seems they bear repeating. Firstly, I'm not talking about you, you are not Elle Westner and you have just as little access to her mind as I do. I don't have to assume your gender, you said you're a woman, and certainly I believe nothing you do makes you less of a woman. But I can't ask Elle Westner can I? For most historical people, I think it's fair to assume their gender to be the one assigned to them, but if there is evidence that might suggest otherwise, we should not assume. Of course we should neither assume it's not their assigned gender, it's entirely possible it is, but the possibility should not be discarded that their gender is different.

It's a little silly tbh to say I'm erasing gender non-comforming historical women, when literally in the same paragraph I mention how it was quite common for queer *women* to dress in masculine clothing. This is literally what I wrote:

Queer women and trans masc people, who dressed in masculine clothing, (which was pretty common) also sometimes bound their chests, but unsurprisingly that was not exactly celebrated like drag performances were, so there weren't binders made for queer people specifically.

(I admit I didn't mention the "mannish" feminists, who dressed masculinely, but they rarely bound their chests, and like many of them were queer also.)

What I will not do (even if you borderline beg) is to erase trans masc and non-binary people from history. Assuming all historical queer and gnc people were their assigned gender without extensive evidence to the contrary (for some people no amount of evidence is ever enough) effectively erases all trans and non-binary people from history, since the way gender was talked about, understood and allowed to express, was often so different from our current understanding and usually erased from historical evidence. That is in fact imposing our understanding of gender to historical people. Yes some women did cross-dress in order to escape misogyny, but that's certainly not the only reason people cross-dressed. Especially since many of them, those who couldn't or didn't try to pass, faced even more misogyny for cross-dressing, but they did it anyway because they had other reasons to cross-dress. The reason why cross-dressing can be evidence of queer gender identity (though of course as said, there are other possible reasons) especially in 19th century, is because in their culture the understanding of gender was heavily tied to gender expression. Even today, when gender and gender expression are seem much more as separate things, if you see a person who looks like a woman, but is dressed in men's clothing, you shouldn't immediately dismiss the possibility that they might not be a woman. Yes, they might be a woman who for one reason or another likes to dress in masculine clothing, or they might not be.