Text

10 Common Reactions to Trauma

This form describes some of the common reactions that people have after a trauma. Because everyone responds differently to traumatic events, you may have some of these reactions more than others, and some you may not have at all.

Remember that many changes after a trauma are normal. In fact, most people who directly experience a traumatic event have severe problems in the immediate aftermath. Many people then feel much better within 3 months after the event, but others recover more slowly, and some continue to experience debilitating symptoms. The first step toward recovery is becoming more aware of the changes that you have undergone since the trauma. Some of the most common problems after a trauma include the following.

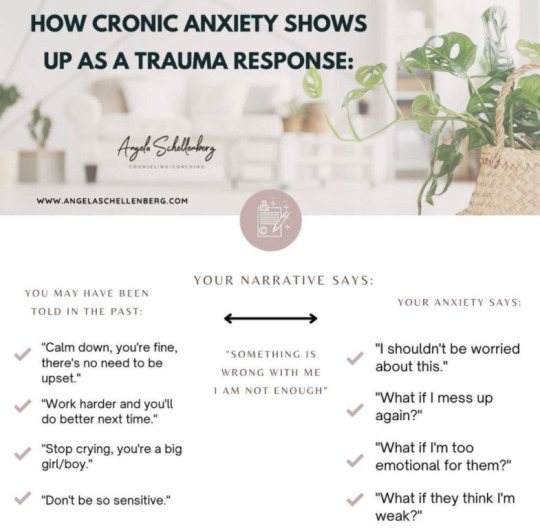

Anxiety and fear. Anxiety is a common and natural response to a dangerous situation. For many people it lasts long after the trauma ended. This happens when views of the world and a sense of safety have changed. You may become anxious when you remember the trauma. But sometimes anxiety may come from out of the blue. Triggers or cues that can cause anxiety may include places, times of day, certain smells or noises, or any situation that reminds you of the trauma. As you begin to pay more attention to the times when you feel anxious, you can discover the triggers for your anxiety. In this way, you may learn that some of the out-of-the-blue anxiety is really triggered by things that remind you of your trauma.

Re-experiencing of the trauma. People often “re-experience” the traumatic event. For example, you may have unwanted thoughts of the trauma and find yourself unable to get rid of them. Some people have flashbacks, or very vivid images, which can feel as if the trauma is occurring again. Nightmares are also common. These symptoms occur because a traumatic experience is so shocking and so different from everyday experiences that you can’t fit it into what you know about the world. So in order to understand what happened, your mind keeps bringing the memory back, as if to better digest it and fit it in with your experiences.

Increased vigilance is also a common response to trauma. This includes feeling “on guard,” jumpy, jittery, shaky, nervous, on edge, being easily startled, and having trouble concentrating or sleeping. Continuous vigilance can lead to impatience and irritability, especially if you’re not getting enough sleep. This reaction is due to the freeze (e.g., deer in the headlights), fight or flee response in your body, and is the way we protect ourselves against danger. Animals also have the freeze, fight or flee response when faced with danger. When we protect ourselves from real danger by freezing, fighting or fleeing, we need a lot more energy than usual, so our bodies pump out extra adrenaline to help us get the extra energy we need to survive.(p. 139) People who have experienced a traumatic event may see the world as filled with danger, so their bodies are on constant alert, always ready to respond immediately to any attack. The problem is that increased vigilance is useful in truly dangerous situations, such as if you are in a war zone or you are being robbed. But increased vigilance becomes harmful, when it continues for a long time even in safe situations.

Avoidance is a common way of trying to manage PTSD symptoms. The most common is avoiding situations that remind you of the trauma, such as the place where it happened. Often, situations that are less directly related to the trauma are also avoided, such as going out in the evening if the trauma occurred at night, or going to crowded areas such as the grocery store, shopping mall or movie theatre.

Another common avoidance tactic is to try to push away painful thoughts and feelings. This can lead to feelings of numbness or emptiness, where you find it difficult to feel any emotions, even positive ones. Sometimes the painful thoughts or feelings may be so intense that your mind just blocks them out altogether, and you may not remember parts of the trauma.

Many people who have experienced a traumatic event feel angry. If you are not used to feeling angry, this may seem scary as well. It may be especially confusing to feel angry at those who are closest to you. People sometimes turn to substances to try and reduce these feelings of anger.

Trauma may lead to feelings of guilt and shame. Many people blame themselves for things they did or didn’t do to survive. For example, some assault survivors believe that they should have fought off an assailant, and blame themselves for the attack. Others who may have survived an event in which others perished feel that they should have been the one to die, or that they should have been able to somehow prevent the other person from dying. Sometimes, other people may blame you for the trauma.

Feeling guilty about the trauma means that you are taking responsibility for what occurred. While doing so may make you feel somewhat more in control, it is usually one-sided, inaccurate and can lead to feelings of depression.

Grief and depression are also common reactions to trauma. This can include feeling down, sad, or hopeless. You may cry more often. You may lose interest in people and activities that you used to enjoy. You may stay home and isolate yourself from friends. You may also feel that plans you had for the future don’t seem to matter anymore, or that life isn’t worth living. These feelings can lead to thoughts of wishing you were dead, or doing something to try to hurt or kill yourself. Because the trauma has changed so much of how you see the world and yourself, it makes sense to feel sad and to grieve for what you lost because of the traumatic experience. If you have these feelings or thoughts, it is very important that you talk to your (p. 140) therapist. Your therapist is trained in how to handle these thoughts and experiences and will help you get through this.

Self-image and views of the world often become more negative after a trauma. You may tell yourself, “If I hadn’t been so weak this wouldn’t have happened to me.” Many people see themselves in a more negative light in general after the trauma (“I am a bad person and I deserved this”).It is also very common to see others more negatively, and to feel that you cannot trust anyone. If you used to think about the world as a safe place, the trauma may suddenly make you think that the world is very dangerous. If you had previous bad experiences, the trauma may convince you that the world is indeed dangerous and others are not to be trusted. These negative thoughts often make people feel they have been changed completely by the trauma. Relationships with others can become tense, and intimacy becomes more difficult as your trust decreases.

Sexual relationships may also suffer after a traumatic experience. Many people find it difficult to feel intimate or to have sexual relationships again. This is especially true for those who have been sexually assaulted, since in addition to the lack of trust, sex itself can be a reminder of the assault.

Many people increase their use of alcohol or other substances after a trauma. Often, they do this in an attempt to “self-medicate” or to block out painful memories, thoughts, or feelings related to the trauma. People with PTSD may have trouble sleeping or may have nightmares, and they may use alcohol or drugs to try to improve sleep or not remember their dreams. While it may seem to help in the short term, chronic use of alcohol or drugs will slow down (or prevent) your recovery from PTSD and will cause problems of its own. Fortunately, there are treatments, such as this one, that can help you recover from PTSD and experience long-term relief from symptoms without the use of alcohol or drugs.

Many of the reactions to trauma are connected to one another. For example, a flashback may make you feel out of control, and will therefore produce anxiety and fear, which may then result in your using alcohol or drugs to try to sleep at night. Many people think that their reactions to the trauma mean that they are “going crazy” or “losing it.” These thoughts can make them even more anxious. As you become aware of the changes you have gone through since the trauma, and as you process these experiences during treatment, the symptoms will become less distressing and you will regain control of your life.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is Trauma?

Emotional Trauma, Psychological Trauma

By Ashley Olivine, Ph.D., MPH | Published on January 04, 2022

Trauma is an emotional response that is caused by experiencing a single incident or a series of distressing or traumatic emotional or psychological events, or both.1 Just because a person experiences a distressing event does not mean they will experience trauma.

This article will cover the types of trauma a person may experience, symptoms, the five stages of trauma, treatment and coping options, and when to seek help from a professional.

What Is Trauma?

When a person experiences a distressing event or series of events, such as abuse, a bad accident, rape or other sexual violence, combat, or a natural disaster, they may have an emotional response called trauma.

Immediate reactions after a traumatic event include shock and denial, while more long-term reactions may include mood swings, relationship challenges, flashbacks, and physical symptoms. These responses may be concerning to the person experiencing them and those around them, but they are normal responses to traumatic events.

While the trauma itself was unavoidable and the responses are normal, they can still be problematic and dangerous. Professional support from a mental health professional such as a psychologist or psychiatrist can help with coping and recovery.

Types of Trauma

Trauma can either be physical or emotional. Physical trauma is a serious bodily injury. Emotional trauma is the emotional response to a disturbing event or situation.1 More specifically, emotional trauma can be either acute or chronic, as follows:

Acute emotional trauma is the emotional response that happens during and shortly after a single distressing event.

Chronic emotional trauma is a long-term emotional response a person experiences from prolonged or repeated distressing events that span months or years. Additionally, complex emotional trauma is the emotional response associated with multiple different distressing events that may or may not be intertwined.

Emotional trauma may stem from various types of events or situations throughout infancy and childhood, as well as adulthood.

Types of Traumatic Events

Traumatic events include (but are not limited to):

* Child abuse

* Child neglect

* Bullying

* Physical abuse

* Domestic violence

* Violence in the community

* Natural disasters

* Medical trauma

* Sexual abuse

* Sex trafficking

* Substance use

* Intimate partner violence

* Verbal abuse

* Accidents

* War

* Refugee trauma

* Terrorism

* Traumatic grief

* Intergenerational trauma

Symptoms

Symptoms of trauma can be both emotional and physical. The emotional response may lead to intense feelings that impact a person in terms of attitude, behavior, functioning, and view of the world. A person may also experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or an adjustment disorder following a traumatic event. This is a disorder characterized by a belief that life and safety are at risk with feelings of fear, terror, or helplessness.

Psychological Symptoms of Emotional Trauma

Emotional responses to trauma can be any or a combination of the following:

Fear

Helplessness

Dissociation

Changes in attention, concentration, and memory retrieval

Changes in behavior

Changes in attitude

Changes in worldview

Difficulty functioning

Denial, or refusing to believe that the trauma actually occurred

Anger

Bargaining, which is similar to negotiation (e.g. "I will do this, or be this, if I could only fix the problem.")

Avoidance, such as disregarding one's own troubles or avoiding emotionally uncomfortable situations with others

Depression

Anxiety

Mood swings

Guilt or shame

Blame (including self-blame)

Social withdrawal

Loss of interest in activities

Emotional numbness

Physical Symptoms of Emotional Trauma

Emotional trauma can also manifest in the form of physical symptoms. These include:

Increased heart rate

Body aches or pains

Tense muscles

Feeling on edge

Jumpiness or startling easily

Nightmares

Difficulty sleeping

Fatigue

Sexual dysfunction, such as erectile dysfunction, difficulty becoming aroused, or difficulty reaching orgasm

Appetite changes

Excessive alertness

Grief and Trauma

Grief is a feeling of anguish related to a loss, most often a death of a loved one. However, the loss is not always a death. It is possible to experience both trauma and grief following a distressing event, especially when the event involves the death of a close friend or family member.

A person experiencing trauma may go through the five stages of grief described by psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. These stages are:

Denial

Anger

Bargaining

Depression

Acceptance

While the stages are often explained in this order, it's important to recognize that a person may move from one stage to another in any order, and they may repeat or skip stages.

Treatment

The effects of trauma can be treated by a mental health professional such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, or therapist.

Psychotherapy, or talk therapy, is the primary treatment option for trauma. There are types of psychotherapy that focus specifically on trauma, such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy, which are effective in treating trauma. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is a method that involves small, controlled exposures to elements related to the traumatic experience to help overcome the trauma.

Treatment plans for those with PTSD regularly include medications to help with mood and sleep.

In addition to professional support, there are many strategies that can be used to cope with and overcome trauma. Talking and spending time with trusted friends and family members can be helpful. There are also support groups specifically for trauma.

It also is important to maintain routines, eat regularly, exercise, get enough quality sleep, and avoid alcohol and drugs.8 Stress plays a role in trauma, so stress management and relaxation can make a big difference.

When to Seek Professional Help

While trauma can be a normal response to a distressing situation, it is sometimes important to seek professional help. There are things that can be done to alleviate symptoms and provide support for coping and moving forward in life. Additionally, without professional help, it is possible for symptoms to escalate and become life-threatening.

Anyone experiencing symptoms of trauma that affect daily life should seek help from a psychiatrist, psychologist, or other mental health professional. Trauma increases the risk of PTSD, depression, suicide and suicide attempts, anxiety, and misuse of substances, so it is a serious mental health concern.

Suicide Prevention Hotline

If you are having suicidal thoughts, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255 for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database.

Summary

Trauma is an emotional response that is caused by experiencing a distressing or traumatic event. This emotional response may be present only during and right after a traumatic event, or it could be prolonged. Some traumatic events such as child abuse may be ongoing, or a person may experience complex trauma, which is exposure to multiple traumatic events.

Symptoms of trauma can be both emotional and physical and include feelings of fear, helplessness, or guilt, mood swings, behavior changes, difficulty sleeping, confusion, increased heart rate, and body aches and pains. It may also become more serious as those who experience trauma may develop PTSD and are at an increased risk of suicide.

Treatment is available. A mental health professional may provide psychotherapy and other support to help overcome the trauma. It is important to seek help if trauma symptoms impact daily life.

FAQs

Can you have trauma but not PTSD?

It is possible to experience trauma without post-traumatic stress disorder. When a person experiences a distressing event, they may experience trauma, which is a long-lasting emotional response to that event. PTSD involves flashbacks, nightmares, avoiding situations connected to the traumatic event, and ongoing symptoms of physiological arousal.

How do I know if I have emotional trauma?

Emotional trauma is the emotional response to experiencing a distressing event. This can be diagnosed by a healthcare professional such as a psychiatrist or psychologist.

Some signs and symptoms of emotional trauma are feelings of hopelessness, anger, fear, disbelief, guilt, shame, sadness, or numbness, mood swings, confusion, disconnectedness, self-isolation, and experiencing the five stages of grief and trauma.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

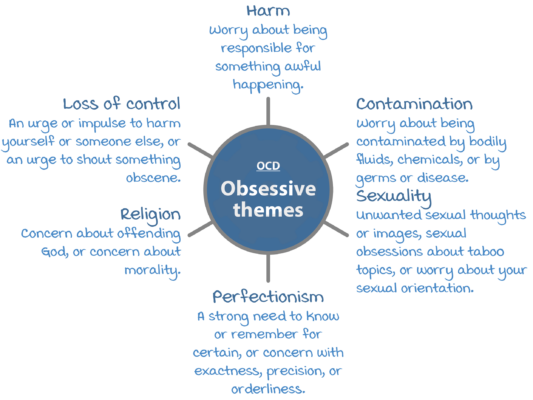

Types of Unhelpful Interpretations of Obsessions

When it comes to having obsessive thoughts, a lot of people automatically assume that they must have OCD. It's important to make the distinction between obsessive thinking or anxious thinking and OCD. Obsessions are purely mental, while compulsions are behavioral. Unless you are acting upon your mental obsessions, you likely do not have OCD. However that being said, having obsessive thoughts can lead to compulsions (behaviors) if not managed accordingly.

Here are some examples of some of the more common unhelpful interpretations or meanings that people give their obsessions or obsessive thoughts to:

𝐓𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐠𝐡𝐭-𝐀𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐅𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧

This is when we think that our unwanted or "bad" thoughts:

Are just as wrong as committing "bad" deeds. (Example is having a thought about maybe beating up your elderly neighbor for no reason and thinking it's just as bad as actually committing the act.)

Increase how likely the "bad" thought will actually happen. (Example: someone dying in a plane crash)

𝐈𝐧𝐟𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐑𝐞𝐬𝐩𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐛𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐲

This is when our obsession involves overestimating or exaggerating the amount of responsibility we have about the outcome of a certain event. (Example: "If I don't wash my hands frequently or carefully, it'll be my fault if someone around me gets sick.")

𝐎𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐓𝐡𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭

This is when we believe or are convinced that our worst fears are extremely likely to happen. (Example: "If I don't wash my hands after touching this door know, I'm going to get AIDS and die.")

𝐌𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐚𝐥 𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐨𝐥 𝐅𝐚𝐢𝐥𝐮𝐫𝐞

This is when we believe that we should be able to always control our thoughts at all times, and when we're not able to be in complete control of them, then it will lead to terrible consequences. (Example: "If I can't control all of my thoughts, then I will go crazy and have a nervous breakdown.") Some people may think things like, "If I can't control my thoughts, then ..."

The thought must have some sort of meaning to it (e.g. "Why else do I keep having these kinds of thoughts?")

The thought must show that I'm flawed (e.g. "I must be weak, otherwise I would be able to control these thoughts")

I will lose control of myself and my behaviors. (e.g. "If I don't stop having the thoughts of stabbing my partner, then I will end up actually doing it.")

𝐏𝐞𝐫𝐟𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐦

This is when we believe that there is only one "perfect" way of doing something or everything, and when anything is less than the idea of perfection that we hold in our mind, it is unacceptable or we're seen as failures.

𝐈𝐧𝐭𝐨𝐥𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐔𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐲

This is when we believe that we have to be 100% certain that something bad will or won't happen in order for us to feel safe or to continue on with our day.

Adapted from Anxiety Canada

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Managing OCD (Part 2)

3. Build Your OCD Management Toolkit

Managing our OCD is best when we begin building our toolkit of strategies to help us deal with our obsessions as they arise in the long run. Breaking this vicious cycle will involve: 1) Learning to increasingly eliminate our unhelpful coping strategies (compulsions), and 2) Learning to think of our obsessions in a more balanced/helpful way.

Tool #1: EXPOSURE & RESPONSE PREVENTION (ERP) - FACING OUR FEARS. Learning to gradually face our fears is one of the most effective ways to help break this cycle for us. This technique is known as Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) or Exposure Therapy. It is done by:

Exposing ourselves to the situations that triggers our obsessions

Not engaging in unhelpful coping strategies like avoidance or compulsions

How?

1. Getting to know our OCD better:

In order to face our fears, it's helpful to know what we are thinking (our obsessions) and to identify what triggers our obsessions and compulsions. We can do so by monitoring and tracking them on a daily basis for a week by keeping a journal to document them.

Because obsessions can happen on a frequent basis, writing 3 triggers a day can be enough to help give us an overview of our obsessions and compulsions. Also rate each trigger/obsession on a scale from 0-10 where 0 = no fear, and 10 = extreme fear.

Also take note of the coping strategies used in response to them. It's important to take note of both behavioral and mental strategies used.

Try and record them as soon as they happen and are fresh in the mind so you have a more accurate idea of what you did.

2. Make a Fear Ladder

After the week of tracking obsessions and compulsions is complete, start making a list of all the feared situations, ranked in order from the least scary to the most scary. You can find an example of how this might look here.

TIP: Make a separate ladder for each obsessive fear

3. Climb that ladder — Exposure & Response Prevention

After putting the fear ladder together, we're now ready to face each fear by putting ourselves in those situations that trigger our obsessions (exposure), while resisting the temptation to control them and the related anxiety (response prevention)

TIP: It's normal to feel anxious when trying these exercises out. It's a good indication that we are on track.

To expose ourselves: Start from the bottom/easiest item on the ladder and then work your way up. Track your progress and anxiety levels throughout the exercise in order to visually see how you gradually decline in fear of a particular situation. Try not to avoid the situation, even by using subtle avoidance (e.g. thinking about other things, talking to other people, touching the door knob with 1 finger instead of your whole hand). Avoidance makes it harder to get over the fear in the long run. Don't rush yourself. It's important to remain in the situation until fear drops by at least half. Focusing on overcoming one fear at a time is a goo idea, as well as exposing yourself frequently until the first item on the ladder doesn't cause as much as a problem anymore. Be patient with yourself.

To do response prevention: Resist the urge to carry out your compulsion either during or after the exposure therapy. The whole point is to learn how to face our fears without having compulsions. Although it's hard to be in a situation without doing a compulsion, it can be helpful to ask a friend or family member to show you how to do it and then model their behavior. It will be hard at first to resist the urge to carry out the compulsion, so if you're struggling with this, try to delay acting on the compulsion rather than not doing it at all. The idea is to get to a point where you don't have to do it anymore. If you do find yourself repeating the compulsion, try to re-expose yourself to the same situation right away and repeat the practice until fear is dropped by half. Once you reach a point where there's only a little anxiety when completing an exercise, it's okay to move onto the next one. Remember these 2 keys for ERP: gradual and consistent!

REMEMBER: It's okay to ask for help! Talk with someone who's supportive of you when you're having the urge to carry out compulsions and feel like you won't be able to resist them. Ask this person to stay with you or go somewhere with you until the urge decreases to a manageable level. You don't have to do this alone!

Tool #2: CHALLENGE UNHELPFUL MEANINGS/ INTERPRETATIONS OF OBESSIONS. This is good to use in combination with ERP in order to address our upsetting and distressing thoughts that are a part of OCD.

Tool #3: STRESS MANAGEMENT. Learning to manage our OCD will come with its challenges and stresses. This is to be expected. Our OCD will also likely be a lot stronger and more difficult to manage when we're under stress or stressed out. In this case, it's super helpful to develop a list of potentially stress-inducing situations that may make our OCD worse. We'll then need to anticipate our stressors so we can feel more prepared when they do happen (and they likely will). It's also a good idea to work on actively reducing our stress and work towards leading a healthier lifestyle.

4. Building on Bravery

Anxiety management is no easy feat, but it's absolutely possible to do. It'll take a lot of hard work. If we're noticing improvements, we should make sure we take some time to give ourselves credit and reward ourselves for our effort.

What's the best way to maintain our progress? Practice!! The skills presented in these 2 parts were designed to help teach us new and more effective ways to deal with our obsessions and compulsions. If we practice these skills often, we will find that our obsessive fears will eventually have a weaker hold on us. Learning to manage our anxiety is a lot like exercise: we need to make sure we "keep in shape" by practicing these skills regularly. After all, it took how many of our years to develop our current frame of mind and thinking? It'll take some time to reverse and rewire it. It helps to try and make it a habit, even after we start feeling better and have reached our goals.

Adapted from Anxiety Canada

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Managing OCD (Part 1)

Just like any disorder that one may be struggling with, the best way to manage it effectively starts with educating yourself on it. When we come to understand how things work and why they happen, the better we're able to figure out how to work with it or to overcome it.

OCD is considered by some to be a type of anxiety disorder. This is because anxiety often plays a huge role in fueling our obsessions and compulsions.

1. Learning About Anxiety

It doesn't matter what type of anxiety any of us are dealing with, it is important that we come to understand the facts about anxiety as it is applicable to all:

Fact #1: Anxiety is a normal response from the body's adaptive system. It tells us when we're in danger. It's our own personal radar that lets us know that we need to respond to a threat. That being said, dealing with anxiety will NEVER involve eliminating it completely. Anxiety can be used for good, but when it's in a disorder, learning how to manage it effectively will help us go from survival mode into thriving mode.

Fact #2: Anxiety becomes a problem when the mind sends us signals that there is danger when there actually isn't. The Amygdala, the part of the brain responsible for sending these signals cannot tell the difference between a real threat or a perceived/thought of one.

Just keep in mind that by understanding that all our worries, fears, and physical feelings are all a result of anxiety. Anxiety manifests in the body in more ways than just our thoughts! Now that we're able to identify and put a name to the problems we're having, we can start dealing with it.

2. Learning About OCD

A lot of people tend to confuse their anxiety for OCD since they are very closely related and the distinction between the 2 can almost seem nonexistent. People with OCD have a tendency to:

Give unhelpful meaning/interpretations to their obsessions, and

Use unhelpful coping strategies to handle the obsessions

NOTE:

* EVERYONE has unwanted or unpleasant thoughts sometimes—it's normal and doesn't mean you have OCD

* Just because we think about something doesn't mean it'll happen. Thoughts can be powerful, but it doesn't mean that these "predictions" or assumptions will come true

* Thinking thoughts that we deem "bad" doesn't mean we are bad people or that we want to do bad things. The kinds of thoughts we have do not define us as good/bad.

Unhelpful Meanings/Interpretations

You might be thinking: if everyone has unwanted or intrusive thoughts, then how come everyone isn't diagnosed with OCD? This is usually because it's the kinds of meanings/interpretations that people give to these kinds of thoughts that set them apart. The meanings we give to these unwanted thoughts can turn into obsessions, which means they'll happen a lot more frequently and with great intensity.

Example: Intrusive thought—"What if I pushed someone into traffic?" If you told yourself something like, "That's a bad thought to have! I know I wouldn't do anything like that though, so I know it doesn't really mean anything," then we are likely not going to develop OCD. If we did end up saying something like, "Why did I think that? Maybe this means I'm a dangerous and horrible person!" then we are likely going to increase our chances of developing OCD if we fixate on how much of an obsessive loop we can get ourselves into on that thought alone. Our interpretation of a thought as being meaningful, important, or dangerous can further perpetuate these unwanted thoughts. That being said, there is still a distinction between obsessive thoughts and thinking and then the compulsions involved as a result of thinking them.

Unhelpful Strategies to Control Obsessions

When we're ill-equipped with strategies to combat our unwanted thoughts and obsessions, we end up doing what we think we can to take care of them and eliminate them. This is only natural. However, because we don't have the right tools to take care of them, we end up inadvertently pushing ourselves into thinking traps that can make the OCD worse.

Trap #1: Things like seeking reassurance, washing things, avoiding things, checking on things won't work. This is because it only eliminates our anxiety for a limited amount of time, so it'll come back again. However, it's because they do work temporarily that we believe that they do work and why we continue to do them every time anxiety pops up. By doing this, we never get a chance to learn a more effective way to manage these obsessions, and the cycle continues.

Trap #2: Using these unhelpful strategies doesn't give us a chance to find out whether or not the meaning/interpretation that we gave to the obsession was actually true.

Trap #3: Using these unhelpful strategies end up having the opposite effect of what we want to achieve. Even though we hope that these things will help us to feel like we are controlling our obsessions, they actually end up making us think more about the obsessions.

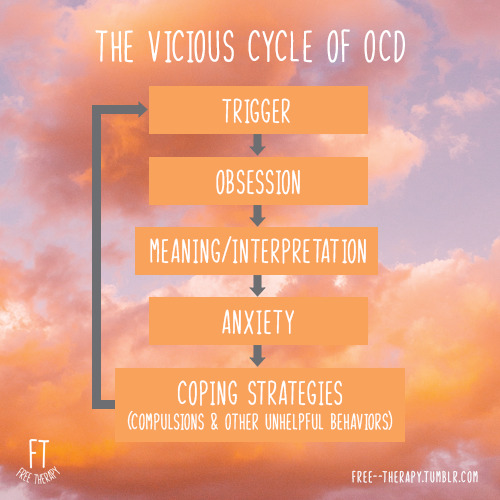

The Vicious Cycle of OCD

When an intrusive thought pops into our head (example: thinking about stabbing your spouse) and we attach an unhelpful meaning/interpretation to it (ex: having this kind of thought means I'm evil for thinking about killing someone I love), we end up feeling quite anxious as a result. Because anxiety is very uncomfortable to us, we will likely find ways to try and lessen it (ex: repeatedly checking to make sure the drawer of sharp objects is locked and maybe saying a prayer) every time this bad thought comes up.

Even though we may feel like these behaviors and strategies will help to lessen the anxiety for a brief moment in time, we will find that we have to do them more and more because that "bad" thought we're having seems to happen more frequently when we try not to think about it. We end up feeling trapped because we don't know what else to do but the same strategy over and over. Before we know it, our live if being consumed by this "bad" thought and our constant efforts to control it. Every hear the expression that insanity is trying to do the same thing over and over and expecting different results?

Adapted from Anxiety Canada

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Managing Obsessions Effectively

Sometimes having unwanted or unpleasant thoughts is normal and everyone has them from time to time. While some people can get quite bothered by them, there are others who don't. The extent at which we are bothered by such thoughts depends on the meaning/interpretation that we give to each thought. Those who deal with OCD generally tend to view these thoughts as either dangerous, meaningful, or important in some way, whereas those without OCD don't give much meaning to the unwanted thoughts and observe them as merely something they know is not real.

Here's an example: "What if touching this door handle at the mall is going to give me some sort of serious disease?"

Those without OCD would probably say something to themselves like: "Nah, that's a weird thought. I'm pretty sure that's not possible for me to catch a deadly disease from a door handle." As a result, there likely wouldn't be any anxiety involved and they would go on about their day.

Those with OCD would probably say something to themselves like: "What if I do contract some sort of disease and then spread it to my loved ones and get them very sick? What kind of person would I be if I didn't wash my hands?" As a result, a spiral of anxiety would ensue, making this person want to engage in the compulsion (likely obsessive hand washing) and the cycle of OCD would begin.

In order to manage these sorts of obsessions or obsessive thinking, the unhelpful thoughts about the obsession would need to be challenge by replacing the negative, unhelpful thinking patterns (cognitive distortions) into more helpful ones. The method is usually most effective when used in combination with Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP).

How to Challenge the Obsessive Thoughts

Step 1: Be mindful of the thoughts you're having

To be able to challenge our unhelpful thoughts or interpretations that we give to our obsessions, we need to be able to know and recognize what they are. How do we start doing this? We need to be aware (mindful) of 2 things in particular: 1) our obsessions, and 2) the meanings we give to the obsessions. A good way to keep track of them is to start by recording some of the obsessions we may have in a day. We can start by recording 2 or 3 of them in order to give ourselves a better idea of what we think about and when it happens in the day.

Here are some things we can ask ourselves to help identify our obsessions:

What makes this obsession so upsetting?

What do I feel like this obsession is saying about me? (ex. my personality)?

If I didn't do anything about this obsession, what kind of person would I be?

What could happen if I didn't do anything about this obsession?

Step 2: Manage the Obsessions

Once we've identified our obsessions and the meanings we've given to them, we can now start to manage them. Here's how:

🔨 Know the Facts

Remember that it's normal to have unwanted or unpleasant thoughts and that just because we have these kinds of thoughts, it doesn't mean that they are true or that we are a bad person. Thoughts are not facts! Anxiety comes as a result of faulty or irrational thinking, which means we are easily believing something that's usually not true. Remember that even though these thoughts may trigger anxiety, they are harmless in nature. A good way to help us manage our obsessions is to keep reminding ourselves of all of this.

🔨 Thinking Realistically

Those of us who are dealing with OCD, just like any other type of anxiety disorder, are prone to falling into thinking traps, a.k.a cognitive distortions. These are unhelpful ways of looking at things or thinking of things, and we're usually all likely to use more than one of these too. It's extremely helpful to be aware of which cognitive distortions we are inclined to use in order to know how to combat it. Learning how to think realistically will also help to challenge our negative thinking patterns.

🔨 Challenging unhelpful interpretations of our obsessions (General Strategies)

Using these questions can help us to come up with a more helpful way to look at our obsessions:

What's the evidence for/against this interpretation?

What are the advantages/disadvantages of thinking this way?

Did I confuse a thought for a fact?

Are these interpretations of this situation realistic and accurate?

Am I using the cognitive distortion of black-and-white/all-or-nothing thinking?

Do I know for 100% sure that _______ will actually happen?

Am I confusing certainties with possibilities?

Is the judgment I'm making based on feelings instead of actual facts?

If a friend told me this interpretation, what would I tell them?

What would a friend say to me about this?

Are there more rational ways of looking at this situation?

When we are able to challenge our initial interpretation about an obsession we're having, then we are much better equipped to give a more balanced meaning to it and see things a little more realistically. We'll also be able to calm ourselves down better when anxiety surrounding the obsession arises again (because they usually don't go away right away).

Remember: It may be difficult at first to challenge and replace our old interpretations of our obsessions. Don't be discouraged about this. Because it took so long for our minds to form them, it'll take some time and repetition to rewire our brains to not think about them as much. It may also be difficult to believe the helpful/more positive interpretations because it feels foreign to us. This is normal and to be expected. We cannot allow it to discourage us and our progress, as it'll get easier the more we practice implementing them. Our belief in the new interpretations will grow stronger over time as we repeat them.

🔨 Challenging unhelpful interpretations of our obsessions (Specific Strategies)

Here are some additional and more specific strategies we can use to challenge some of the more common misinterpretations of certain obsessions:

1. Calculating the probability of actual danger: This helps us to be more realistic about the likelihood of our worst fear actually happening.

How?

a) Predict how likely our fear will actually happen.

b) Figure out the steps needed to make it come true for real. What would need to take place?

c) Estimate the chance of each of the aforementioned steps happening (ex. 5% chance). Don't worry about getting the percentages right. What matter is coming up with what we think the chances are.

d) Calculate the overall change of the fear coming true by multiplying together the changes of each separate event.

e) Compare the overall chance with the original prediction.

By calculating the realistic probability of danger actually happening, we will be able to see that the likelihood of it actually happening is a lot lower than we initially thought.

Remember: Just because we think something bad will happen, doesn't mean it will. This is why we need to look at our thoughts and decide whether our OCD thoughts are wrong/unhelpful.

2. Responsibility pie: This helps us to challenge our excessive sense of responsibility that we think we have regarding a certain situation.

How?

a) Write down how responsible you'd feel is something you fear actually happened.

b) Write down all the possible factors that can contribute to this event that are outside of your own reach.

c) Draw a pie graph that represents all of the percentages of responsibility for every factor involved and assign a slice for each

d) Assign a slice for yourself as well. How does this percentage compare to the original prediction made?

3. Continuum technique: This helps us to gain better perspective of how "bad" we really are for having a thought that we think may be "bad". To challenge our beliefs, we can create a list of people who could fit on either side of a continuum that ranges from maybe the most gentle/good person you can think of on one end, and the most awful/bad person on the other. Figure out where you fit on the continuum. You may feel inclined to put yourself at the worst end of it, but eventually you'll think about other people who have committed more horrible acts (as opposed to having just bad thoughts) than yourself. Then your position would change.

Using this technique may also come to show us how harsh we are on ourselves than we are on other people. We may believe it's okay for other people to have "bad" thoughts and not act on them, but tell ourselves it's not okay for us to ever have a bad though, even though we don't act on them.

4. Survey method: This can help us to challenge our need for certainty. We can do something like asking our friends and families about something. An example could be asking them how well they remember everything that they read or how well they remember how a certain chore or task they perform. Comparing the results to our initial prediction can give us a lot more perspective on how other people may not think like we do and that's okay.

Adapted from Anxiety Canada

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)?

By Sherry Christiansen | Updated on February 07, 2021

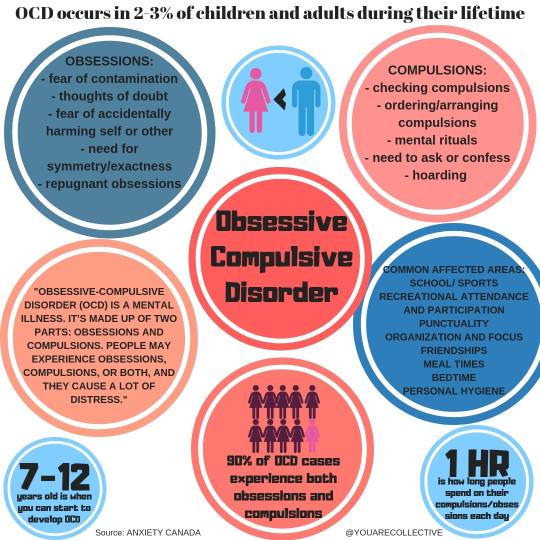

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is considered a chronic (long-term) mental health condition. This psychiatric disorder is characterized by obsessive, distressful thoughts and compulsive ritualistic behaviors. Those with obsessive-compulsive disorder are known to have a variety of symptoms and behaviors that are a characteristic of the disorder.

A person with OCD commonly performs the same rituals (such as handwashing) over and over and may feel unable to control these impulses. These repetitive behaviors are often performed in an effort to reduce distress and anxiety.

Characteristics / Traits / Symptoms

The symptoms of OCD may involve characteristics of obsessions, behaviors that would indicate compulsions, or both. Symptoms are often associated with feelings of shame and concealment (secretiveness).

Common Obsessive Symptoms

In OCD, obsessions are defined as repetitive thoughts, urges, impulses, or mental images that cause anxiety or distress. These obsessions are considered intrusive and unwanted.

The person attempts to ignore or suppress the thoughts, urges, or images via some other thought or action (such as performing compulsive actions).

Common obsessions exhibited by those with OCD may include:

Fear of getting germs by touching items perceived as being contaminated (exhibited by fear of touching things that others have touched, the fear of shaking hands, and more)

A strong need for order exhibited by feelings of extreme anxiety when things are out of order or asymmetrical or when objects are moved by someone else and/or difficulty leaving the house (or the room) until objects are deemed perfectly placed

Taboo thoughts which often involve very troubling thoughts about topics such as sex or religion

Aggressive thoughts which often involves fear of harming others or self and may manifest as compulsive behaviors, such as being obsessed with news reports about violence

Common Compulsive Symptoms of OCD

Compulsions can be defined as specific types of repetitive behavior or mental rituals that a person with OCD often engages in (to the point of being ritualistic). These repetitive behaviors help reduce distress that comes from obsessive thoughts.

There is a very strong compulsion to perform these repetitive actions and behaviors, and over time, they become automatic. A person feels driven to perform these repetitive behaviors as a way of either lowering anxiety or preventing a dreaded event from occurring.

Compulsive behaviors may include repeatedly checking things, handwashing, praying, counting, and seeking reassurance from others.

Specific examples of common compulsions in people with OCD include:

Excessive handwashing or cleaning (which may include taking repetitive showers or baths each day)

Excessive organizing (putting things in exact order or having a strong need to arrange things in a very precise manner).

Ritualistic counting (such as counting the numbers on the clock, counting the number of steps taken to reach a certain place or counting floor or ceiling tiles)

Repetitively checking on things (such as checking doors and windows to ensure they are locked or checking the stove to make sure it’s turned off)

Most people (even those without OCD) have some mild compulsions—such as the need to check the stove or the doors a time or two before leaving the house—but with OCD, there are some specific symptoms that go along with these compulsions such as:

The inability to control the behaviors (even when the person with OCD is able to identify the thoughts or behaviors as abnormal)

Spending at least one hour each day on the obsessive thoughts or behaviors or engaging in behavior that results in distress or anxiety or erodes the normal function of important activities in life (such as work or social connections).

Experiencing a negative impact in day-to-day life as a direct result of the ritualistic behaviors and obsessive thoughts

Having a motor tic—a sudden, quick, repetitive movement —like blinking the eye, facial grimacing, jerking of the head, or shoulder shrugging. Vocal tics that may be common in those with OCD include clearing the throat, sniffing and other sounds.

Common Traits of People With OCD

Some adults, and most children with OCD, are unaware that their behaviors and thoughts are abnormal. Young children are not usually able to explain the reason they have disturbing mental thoughts or why they perform ritualistic behaviors. In children, the signs and symptoms of OCD are usually detected by a teacher or a parents.

Commonly, people with OCD may use substances (such as alcohol or drugs) to lessen the stress and anxiety associated with their symptoms. The symptoms of OCD may change over time; for example, some symptoms will come and go, others may lesson or they may get worse over time.

Diagnosis or Identifying OCD

There are no diagnostic lab tests, genetic tests, or other formal tests for diagnosing OCD. A diagnosis is made after an interview with a skilled clinician (a professional who has been trained in diagnosing mental health conditions). This could be a licensed clinical social worker, a licensed psychologist, or a psychiatrist (a medical doctor specializing in the field of psychiatry).

The qualifications for who can make a formal diagnosis varies from state to state. For example, in some states, a diagnosis can be made by a licensed professional counselor (LPC) in addition to other licensed professionals. Be sure to check your state’s mandates on who can make a diagnosis in your geographic location.

Here are the traits and symptoms that a qualified clinician will look for when formulating a diagnosis of OCD:

Does the person have obsessions?

Does the person exhibit compulsive behaviors?

Do the obsessions and compulsions take up a significant amount of the person’s time/life?

Do the obsessions and compulsions interfere with important activities in life (such as working, going to school or socializing)?

Do the symptoms (obsessions and compulsions) interfere with a person’s values?

If the clinician finds that the obsessive, compulsive behaviors take up a lot of the person’s time and interfere with important activities in life, there may be a diagnosis of OCD.

If you suspect that you, or a friend or family member may have OCD, be sure to consult with your healthcare provider about the symptoms as soon as possible. When left untreated, OCD can impact all aspects of a person’s life. Also, keep in mind that early diagnosis and intervention equates to better treatment outcomes.

Causes

The exact cause of OCD is unknown, but new research is uncovering some strong evidence that points to why OCD occurs. This may help to provide insight into successful treatment of OCD in the future.

Studies

A 2019 study discovered new data that enabled researchers to identify the specific areas of the brain and the processes associated with the repetitive behaviors of those with OCD.

Researchers examined hundreds of brain scans of people with OCD and compared them with the brain scans of those who did not have OCD. This is what the researchers discovered:

MRI brain scans revealed structural and functional differences in neuronal (nerve) circuits in the brains of those with OCD.

The brains of those with OCD were unable to use normal stop signals to quit performing the compulsive behaviors (even when the person with OCD knew they should stop).

Error processing and inhibitory control are important processes that were altered in the brain scans of those with OCD. These functions (error processing and inhibitory control) normally enable a person to detect and respond to the environment and adjust behaviors accordingly.

According to the lead study author, Luke Norman, Ph.D., “These results show that, in OCD, the brain responds too much to errors, and too little to stop signals. By combining data from 10 studies, and nearly 500 patients and healthy volunteers, we could see how brain circuits long hypothesized to be crucial to OCD are indeed involved in the disorder,” says Norman.

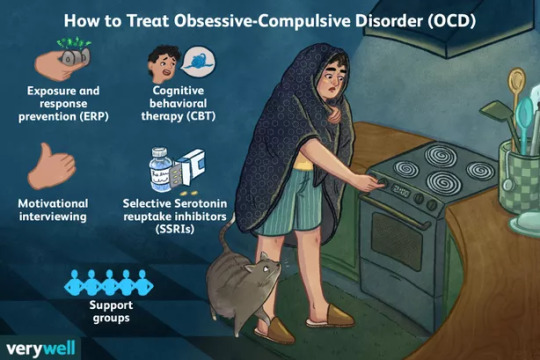

Treatment

Early identification and prompt treatment of OCD is important. There are some specific types of treatment as well as medication that may be more effective when the disease is diagnosed early on.

But, in many instances, a diagnosis of OCD is delayed. This is because the symptoms of OCD often go unrecognized, partially because of the wide range of diverse symptoms. Also, many manifestations (such as obsessive thoughts) are kept secret by the person with OCD.

In fact, according to an older study published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, it takes a person on average of 11 years to start treatment after meeting the diagnostic criteria for the disease.

A 2014 study, published by the Journal of Affective Disorders, discovered that early detection and treatment are known to result in better treatment outcomes.

Often, people with OCD realize significant improvement in symptoms with proper and timely treatment, some people even achieve remission.

Cognitive Therapy

There are a variety of cognitive therapy modalities used to treat OCD.

Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP)

Exposure and response prevention is one type of cognitive therapy that is used to treat OCD. This type of therapy encourages people with OCD to face their fears without engaging in compulsive behaviors. ERP aims to help people break the cycle of obsessions and compulsions to help improve the overall quality of life for those with OCD.

Exposure and response therapy begins with helping people confront situations that cause anxiety. When a person has repeated exposure, it helps to lower the intensity of anxious feelings associated with certain situations that normally engender distress.

Starting with situations that cause mild anxiety, the therapy involves moving on to more difficult situations (the ones that cause moderate and then severe anxiety).

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Cognitive behavioral therapy is a type of therapy offers elements of ERT, but also includes cognitive therapy, so it’s considered a more all-inclusive type of treatment, compared to ERP alone.

Cognitive therapy is a type of psychotherapy that helps people change their problematic thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, improving skills such as emotional regulation and coping strategies. This helps people to more effectively deal with current problems or issues.

The therapy can include 1-to-1 sessions with a therapist or group therapy; it’s also offered online by some providers.

Motivational Interviewing

Using motivational interviewing is thought to increase engagement in therapy and improve outcomes for people with OCD.

In contrast to cognitive therapy, psychotherapy has not been proven effective in the treatment of OCD.

Medication

There are several types of medication commonly prescribed to treat OCD. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the preferred initial pharmacotherapy for OCD.

SSRIs include Prozac (fluoxetine), Zoloft (sertraline), and Luvox (fluvoxamine). Tricyclic antidepressants such as Anafranil (clomipramine) may be used.

When taking SSRI’s, there are some basic guidelines that apply, these include:

People with OCD need a higher dosage of SSRIs compared to those with other types of diagnoses.

The dosage should start low and gradually increase over a four- to six-week time span until the maximum dosage is reached.

Careful monitoring by the prescribing physician is important (particularly when higher than usual dosages are given).

The medication should be given for a trial period of eight to 12 weeks (with at least six weeks of taking the maximum dose). It usually takes at least four to six weeks and sometimes up to 10 weeks to see any type of significant improvement.

If first line treatment (such as Prozac) is not effective for symptoms of OCD, it’s advisable to consult with a psychiatrist (a doctor who specializes in treating mental illness and who can prescribe medications). Other medications, such as the atypical antipsychotics or clomipramine may be given to help potentiate the SSRI medication regime.

If you are prescribed medication for OCD, it’s important to:

Be closely monitored by a healthcare provider (such as a psychiatrist) for side effects and symptoms of comorbidities (having two or more psychiatric illnesses at one time) such as depression, as well as being monitored for suicidal ideation (thoughts of suicide).

Refrain from suddenly stopping your medication without the approval of your healthcare provider.

Understand the side effects and the risks/benefits of your medication. You can find some general information about these medications on the NIMH (Mental Health Medications) website.

Report any side effects to your healthcare provider as soon as they are noticed, you may need to have a change in your medication.

Coping

As with any type of mental health condition, coping with OCD can be challenging, for the person who is diagnosed with OCD, as well as for the family members. Be sure to reach out for support (such as participating in an online support group) or talk to your healthcare provider or therapist about your needs.

You may need to educate friends and family members about OCD. Keep in mind that OCD is not some type of dark behavioral problem, but rather, a medical problem that is not the fault of anyone who is diagnosed with the disorder.

7 notes

·

View notes