Photo

The reconstructed face of the “Cheddar Man” (c. 7,000 BCE) compared to his living descendant, Adrian Targett

The Cheddar Man is a Mesolithic skeleton that was recovered from England’s Cheddar Gorge in 1903. At around 9,000 years old, the Cheddar Man is the oldest complete skeleton ever discovered in the UK, and has long been hailed as the “first Briton.” DNA analysis on the Cheddar Man from 2018 indicated that he was lactose intolerant, had light-colored eyes, dark brown or black hair, and had a dark to black skin tone. Although the discovery of the Cheddar Man’s dark skin tone was surprising for both scientists and the public alike, it corresponds with recent research suggesting that genes linked to lighter skin only began to spread into Europe about 8,500 years ago - approximately 32,000 years later than what was previously believed.

In addition to the development on his skin tone, the Cheddar Man surprised scientists in 1997 when DNA analysis revealed that he had a living descendant - a retired history teacher named Adrian Targett. Targett and the Cheddar Man share the same mtDNA, which is inherited through the mother. In other words, they share a common maternal ancestor. What is even more remarkable is that Targett lives in Cheddar, only a half mile away from where his 9,000-year-old ancestor was discovered.

Targett was not invited to the initial reveal of his ancestor’s new facial reconstruction, but he has since seen it and has commented on the family resemblance. “I do feel a bit more multicultural now,” he once joked in an interview “And I can definitely see that there is a family resemblance. That nose is similar to mine. And we have both got those blue eyes.”

The development of the Cheddar Man’s skin tone has generated resistance, especially among far-right and white supremacist circles. Targett, however, is unbothered by it, stating that it is “marvelous what scientists can reconstruct once they sequence the DNA.” When asked if he thought whether the findings affected the way people think about race, Targett responded: “Yes, I do think it’s significant. Not many people in Cheddar mind it. But the lesson is that we’re all immigrants, whether you’ve been in a place for 10 minutes or 9,000 years. We’ve all come from somewhere.”

34K notes

·

View notes

Photo

On December 6th, 1912, the famous bust of Nefertiti was discovered at Amarna, in the ruins of the workshop belonging to the sculptor Thutmose. The discovery was made by a team from the German Oriental Company, led by an archaeologist named Ludwig Borchardt, who described the find in his diary:

Suddenly we had in our hands the most alive Egyptian artwork. You cannot describe it with words. You must see it

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Piney Island “Face Rock,” c. 4000 BP

This 5 inch diameter river cobble was uncovered in 1973 during excavations of Piney Island, located on the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. The object is from the Transitional Period of Pennsylvania Prehistory, which occurred approximately between 2700 and 4300 years ago. Sometimes known as the Terminal Archaic , the Transitional Period represents a transition in lifeways between Archaic Period foraging and Woodland Period sedentary Agriculture.

The Face Rock may have been created by the Native Americans who lived on Piney Island during the Transitional period, or it may have come to the inhabitants by trade. The object may have been painted and even decorated with feathers, but this is just conjecture. The Face Rock is considered to be the earliest nonutilitarian object to be found in Pennsylvania, indicating that three to four millennia ago people in this region were beginning to portray likenesses of human features on objects, creating a form of art.

The Piney Island Face Rock is on display in the Hall of Anthropology and Archaeology at The State Museum of Pennsylvania.

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Pitfalls of “Charismatic Archaeology” - Part One: What’s in a Name?

All right, as promised, we’re going to take a look at the phenomenon of “charismatic archaeology” (Munawar 2017, 41) as it applies to the so-called Arch of Triumph in Palmyra, which was destroyed by Islamic State militants in 2015 and whose modern cultural context has seemingly superseded its archaeological context in the years since. Because there’s a lot to go over here, I’m going to have to split this up into a few parts. But the main takeaway of this series is that this arch—or tripylon—is still fascinating, even if it isn’t necessarily as ‘Roman’ as we are led to believe and that branding it as such does a disservice to the local Palmyrene builders responsible for its innovative construction in the late second to early third centuries AD (but more on that in later installments).

We already encounter an issue with the classification of this monument as a triumphal arch. Once it was torn down by the Islamic State in October 2015, the tripylon was introduced to the public on a global scale. In their reporting, numerous international news outlets used this term to describe the structure. However, this inaccurate classification pre-dates the arch’s destruction: my thesis advisor told me that when she last visited Palmyra in 2005, the archaeological park guided tourists to the monument and the adjacent section of the city’s Great Colonnade with a sign that read “Triumph Arc (sic) and the Long Street.” That said, the vast majority of the archaeological literature that was written prior to 2015 more accurately designates it as simply a monumental arch or, more commonly in the German-speaking world, a tripylon.

Other common misattributions the monumental arch is given are those of “Hadrian’s Arch/Gate” and the “Arch of Septimius Severus,” though the former is more often a fixture in the German-speaking world (where it’s called the Hadrian Bogen or Hadrianstor). In AD 129/130, Hadrian did himself travel to Palmyra, and during his stay, he granted the city his name (Hadriana Palmyra; Browning 1979, 27). And while it is true that there was an uptick in monumental civic construction and ‘Romanization’ in the city afterwards, the tripylon had not begun to be built until roughly the late Antonine period, around AD 175/180 (Barański 1995, Fig. 1; Tabaczek 2001, 128), so it could not have feasibly been built for Hadrian (in contrast to Hadrian’s Arch in Gerasa, Jordan). Similarly, this start date places its chronology too early to have been built for Septimius Severus, either, as his reign lasted from AD 193–211. That said, a number of scholars do date its construction to his reign or to post-212 more broadly (e.g. Browning 1979, 88; Burns 2017, 245; or Will 1983, 74). However, in doing so, they fail to take into consideration that a structure as large and complicated as the tripylon (more on that later) would have taken years and years to complete, and it was most likely finished sometime in the late Severan period (Tabaczek 2001, 38. 130). Therefore, any commemorative/honorific purpose for this arch is called into question (though statues to Odenathus and his family were placed in niches in the central passageway well after its initial construction in the mid-late 3rd century AD; Burns 2017, 245).

The monument’s designation as a ‘triumphal’ arch or the Arch of Hadrian/Septimius Severus immediately brings it firmly into the realm of ‘Roman’ archaeology, but naming it as such ignores the tripylon’s indigenous Palmyrene context, which in itself tells a much richer story than its apparent association with the Roman Empire. It should be stressed that the term ‘triumphal arch’ was seldom used in antiquity (Cassibry 2018, 246) and that scholars from over a century ago had even expressed the need to use caution when defining these monuments as such (Densmore Curtis 1908, 27). Not only does this term signal the ‘Romanness’ of these structures, but it tends to evoke a sense of particular importance or gravitas to the modern layperson on account of how modern Western powers have adapted the architectural form and used it to express their own “cultural statement,” whether at home or abroad in colonized territories (e.g. the Arc de Triomphe in Paris or the Gateway of India in Mumbai; Ball 2016, 286).

In reality, the eastern Roman territories of Syria and Provincia Arabia have no known ‘true’ triumphal arches, such as those that we’d associate with the city of Rome itself (e.g. the Arch of Septimius Severus or the Arch of Constantine; Ball 2016, 286), but there are three known commemorative/honorific arches to the emperors Trajan (Dura Europos) and Hadrian (Jerusalem and Gerasa; Segal 1997, 131). The point of such monuments was to serve as imperial propaganda “in Wort und Bild” (“in word and image”; Kader 1996, 184). As we will see in later parts of this series, this was not necessarily the case where Palmyra’s tripylon is concerned.

Speaking of cultural statements and propaganda, it is also possible that the concept of triumph was used to the advantage of the Institute for Digital Archaeology of Oxford and Harvard Universities when it decided to use digital methodologies to create a physical reconstruction of the tripylon in 2016 (and believe me, there will be an entire separate post about everything that was wrong with this replica). The IDA’s branding of the tripylon as such in the wake of the Islamic State’s retreat from Palmyra may have delivered a different kind of political message in the sense that the arch and its subsequent reconstruction could represent a triumph of the Syrian people and their cultural heritage over the militants and their wanton destruction of it—perhaps as a 21st-century parallel to Zenobia’s liberation of Palmyra from the Roman Empire (Munawar 2019, 152). Whatever the reason, the emphasis on the monument’s charismatic ‘triumphal’ nature obfuscates its ancient urbanistic context, which will be discussed more in detail in the next part of this series.

Thanks for reading!

Works Cited:

W. Ball, Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire, 2nd Edition (London 2016).

M. Barański, The Great Colonnade of Palmyra Reconsidered, Aram Periodical 7(1), 1995, 37–46.

R. Burns, Origins of the Colonnaded Streets in the Cities of the Roman East (Oxford 2017).

I. Browning, Palmyra (Park Ridge 1979).

K. Cassibry, Reception of the Roman Arch Monument, AJA 122 (2), 2018, 245–275.

C. Densmore Curtis, Roman Monumental Arches (New York 1908).

I. Kader, Propylon und Bogentor. Untersuchungen zum Tetrapylon von Latakia und anderen frühkaiserzeitlichen Bogenmonumenten im Nahen Osten (Mainz am Rhein 1996).

N. Munawar, Reconstructing Cultural Heritage in Conflict Zones: Should Palmyra be Rebuilt?, EX NOVO Journal of Archaeology 2, 2017, 33–48.

N. Munawar, Competing Heritage: Curating the Post-Conflict Heritage of Roman Syria, Bulletin - Institute of Classical Studies 62(1), 2019, 142–165.

A. Segal, From Function to Monument: Urban Landscapes of Roman Palestine, Syria and Provincia Arabia (Oxford 1997).

M. Tabaczek, Zwischen Stoa und Suq. Die Säulenstraßen im Vorderen Orient in römischer Zeit unter besonderer Berücksichtigung von Palmyra (Diss. University of Cologne 2001).

E. Will, Le développement urbain de Palmyre, Syria 60, 1983, 69–81.

Image Source: x (the first is from a PowerPoint I presentation I gave in January)

#archaeology#classical archaeology#syrian archaeology#palmyra#ancient history#ancient rome#syria#mod s#the irony is not lost on me that i'm tagging this as classical/roman archaeology

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

So to clarify why this blog has been on semi-hiatus for a while: S and I have been very busy in school. S has recently finished up grad school and wrote her master’s thesis on Palmyra’s monumental arch while assisting at a database for ancient coinage from the regions of Thrace, Moesia Inferior, Mysia, and the Troad. I have been working in cultural resource management and historic preservation in America, and I am currently in grad school about to start a thesis on material sourcing lithic tools dating to the Monongahela Cultural Tradition. S has already promised to share her material, I will have to share some of mine when I finally get into the meat and potatoes of my thesis.

~A

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

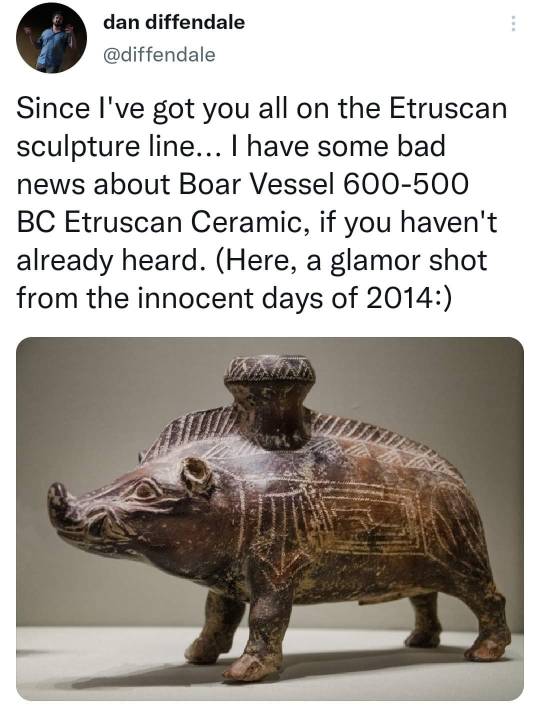

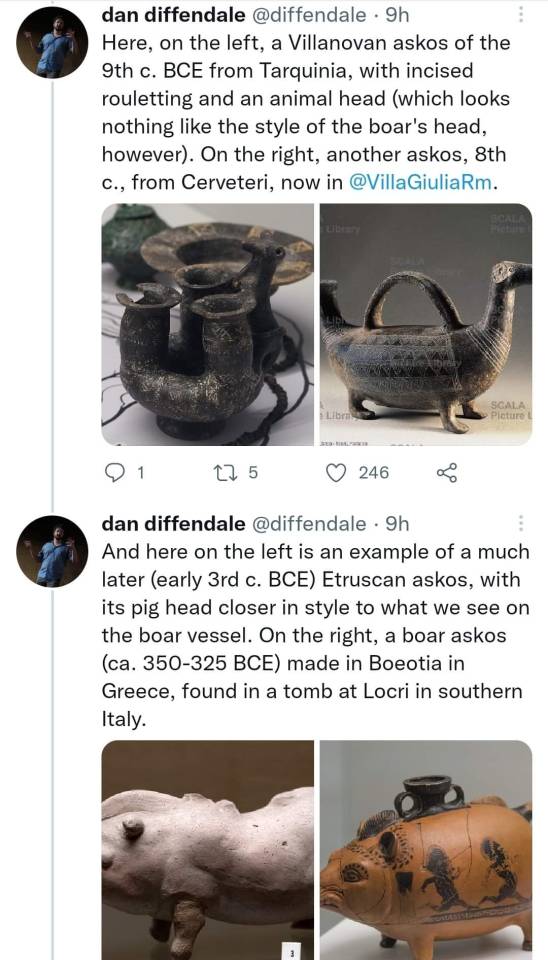

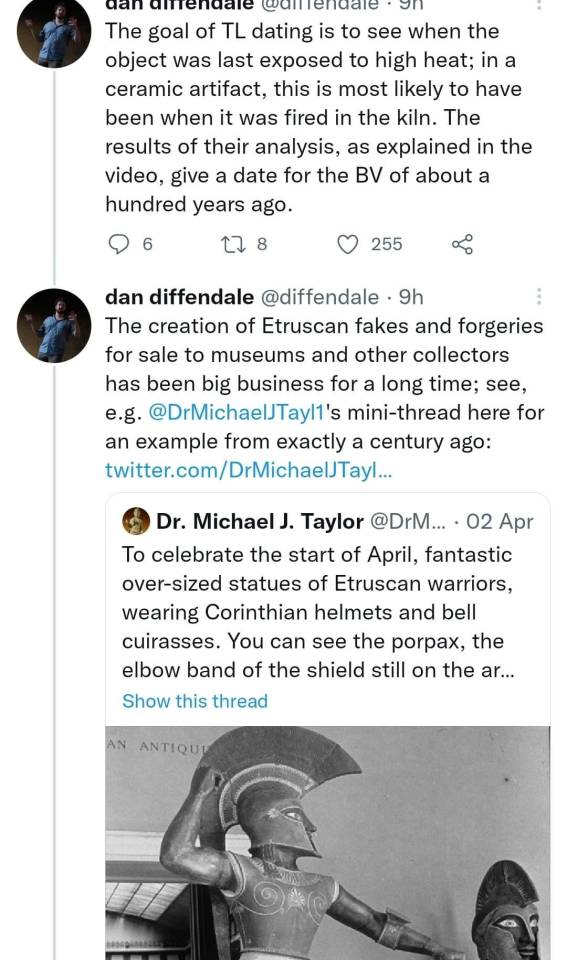

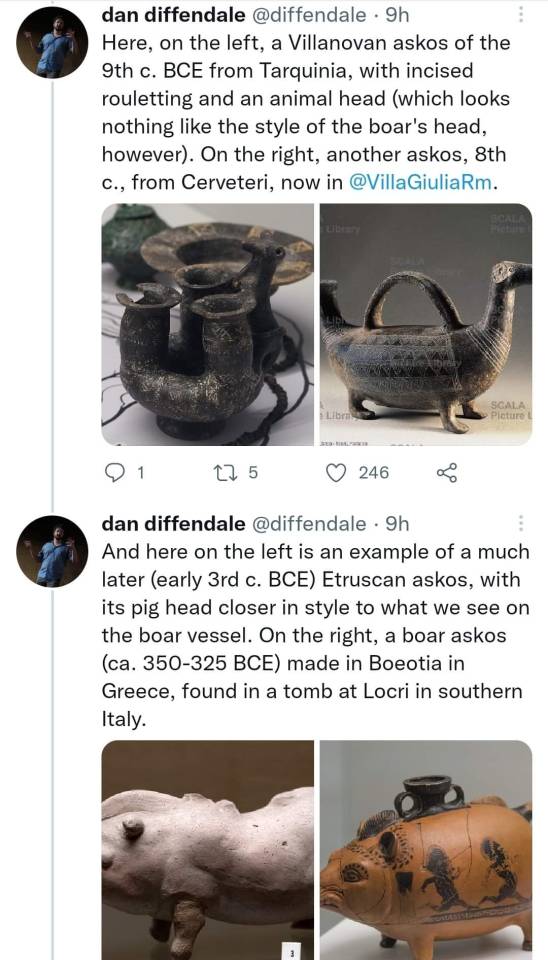

Also, I went straight to the source to ask if diffendale regrets ruining boar posting for everyone and they said yes. Sometimes archaeology be dropping truth bombs no one wants.

Y'all hear that Boar Vessel 600-500 BC Etruscan Ceramic is fake?

In all seriousness, this thread was written by a classical archaeologist from the University of Michigan. Very interesting thread about antiquities and authenticity. I just wish boar posting could have been spared. 🐗

Link to original twitter thread

809 notes

·

View notes

Text

Y'all hear that Boar Vessel 600-500 BC Etruscan Ceramic is fake?

In all seriousness, this thread was written by a classical archaeologist from the University of Michigan. Very interesting thread about antiquities and authenticity. I just wish boar posting could have been spared. 🐗

Link to original twitter thread

809 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m coming out of my even longer hiatus on this blog to follow up on A’s point, which is a very good one, and one which was ever-present as I was working on my master’s thesis earlier this year.

The field of conservation biology has a term that describes a similar phenomenon: “charismatic megafauna.” Species that fall under this umbrella include elephants, polar bears, wolves, and all sorts of other (mostly) large animals that have high symbolic value and receive widespread attention to the exclusion of others that may be even more critically endangered but don’t quite grasp the public’s interest (because let’s face it: a mussel isn’t ever going to be put on the same pedestal as a panda bear; for more on the classification of “charismatic” species, see: Ducarme et al. 2012 or Glas 2016). Syrian archaeologist Nour A. Munawar (2017, 41) has adapted this idea and coined the term “charismatic archaeology” in response to the treatment of Palmyra’s cultural heritage in the wake of the site’s destruction in 2015.

So, just as most of us know that one kid who had a major wolf phase, many others (including me, and probably a lot of you) had an Egypt phase or an ancient Greece phase because these are the “charismatic” civilizations that we (or at least those of us growing up in a WEIRD society) had exposure to. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that! But, as A said, there are so many other civilizations that have been largely ignored despite being just as interesting and awe-inspiring, and they also deserve our attention.

Before this turns into even more of a novel, I’m going to work on a separate post about the pitfalls of charismatic archaeology using the monumental arch of Palmyra as a case study (because I literally wrote 98 pages about this one structure and have a lot of feelings about how its historical/archaeological context has been misrepresented out of the desire to portray it as a “Roman” monument above all else). So, stay tuned for that.

-S

To be honest, the only reason I still post egyptology and classical archaeology content on this blog (when i actually feel motivated to post something) is because it's what gets notes on here. It's ironic because I see so much discourse on tumblr about how they want to see more non-western history and archaeology, but when that content is actually delivered to them it gets a fraction of what the boring Egyptian shit gets.

This isn't inherently tumblr's fault, it's part of a larger societal issue of how the public views archaeology. It's just a shame because precolumbian North America is incredible and amazingly sophisticated. I wish more people could see that.

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

To be honest, the only reason I still post egyptology and classical archaeology content on this blog (when i actually feel motivated to post something) is because it's what gets notes on here. It's ironic because I see so much discourse on tumblr about how they want to see more non-western history and archaeology, but when that content is actually delivered to them it gets a fraction of what the boring Egyptian shit gets.

This isn't inherently tumblr's fault, it's part of a larger societal issue of how the public views archaeology. It's just a shame because precolumbian North America is incredible and amazingly sophisticated. I wish more people could see that.

90 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm strictly an amateur but it seems to me that researcher Murat Bardakçı's rendering of the skeleton mosaic text as “You get the pleasure of the food you eat hastily with death” communicates essentially the same sentiment as "eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die"

I mean, maybe? I can see why you think that. Honestly, I wrote that post years ago and I'm not even in classical archaeology anymore (I study prehistoric North America now and quite frankly I enjoy it a lot more). I don't remember why I included Bardakçı's interpretation to that post. I'm sure there was a reason, but at this point I can't be bothered to reread my sources and edit the post accordingly 🤷♀️

~A

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yes, this a real publication and it's amazing. I literally came out of hiatus to share this. You're welcome.

Archaeology: We are a serious scientific discipline that can implement technologies that are used in STEM fields

Also archaeology:

850 notes

·

View notes

Text

Man finds 3,400-year-old Egyptian anchor during his morning swim

Rafi Bahalul was taking a morning swim off the shores of Atlit, Israel, when he spotted hieroglyphs in the seabed.

“I saw it, kept on swimming for a few meters, then realized what I had seen and dived down to touch it,” Bahalul told Haaretz. “It was like entering an Egyptian temple at the bottom of the Mediterranean.”

Bahalul had discovered a 3,400-year-old Egyptian stone anchor, confirmed by Jacob Sharvit, head of the Israel Antiquities Authority’s maritime archaeology unit.

The anchor is currently on loan from the Israel Antiquities Authority to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem and is on display as part of its Emoglyphs: Picture-Writing from Hieroglyphs to the Emoji exhibition. Read more.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Detail of a Roman floor mosaic depicting Oceanus, on display at the Museo archeologico nazionale delle Marche in Ancona, Italy

607 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mausoleum of Pozo Moro

Pozo Moro, Iberia, Spain

6th century BCE

10 m. high

The Mausoleum was found in pieces in an Iberian necropolis, strewn over a 12 x 12 m. The Mausoleum, which was erected by an Iberian king around 500 BCE, is the oldest known Iberian grave monument. The find spots of the rectangular blocks enabled an accurate reconstruction of the structure, which must have been about 10 metres high and have stood atop a three-level square pedestal 3.65 m wide. Four stone lions stood on the corners of the mausoleum, whose walls were decorated with reliefs depicting deities. These sculptures belong to the orientalising phase of Iberian art and are heavily influenced by Hittite and Syrian art

530 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Two Dog Palette

The head of one of the dogs that frame the top of the palette is missing, and two drilled holes at the base of the neck suggest that it was repaired in antiquity. On the reverse of the palette, a mixture of fabulous and real wild animals occupy the left-hand side of the scene from where they attack a range of herbivores native to North Africa. From the top, there are a pair of lions, a serpopard, a leopard, a hyena and a griffin with comb-like wings. At the bottom is a long-tailed dog-like creature wearing a belt and playing an end-blown flute.

Presumably some of the imagery was carried to Egypt along trade routes, perhaps as seal impressions on containers, and the exotic creatures were adopted by Egypt’s early kings to express their otherworldly status and power.

Predynastic Period. ca. 3300-3100 BC. Siltstone. From Hierakonpolis (Nekhen). Now in the Ashmolean Museum. Oxford. AN1896-1908 E.3924

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Field Gear Masterpost

Help!

Can anyone make field school supply recommendations? Specifically things you wouldn’t think about your first time in the field. I’ll be in SW Ohio. What shoes do I wear? I obviously have my trowels and such from the supplies list but I feel like there are things I am missing. What works better in the field, a ball cap or bucket hat? I need help from experienced professionals or at least people who know more than me.

——

Hi, so I don’t know how long this has been in the inbox. If it has been a long time then I deeply apologize and hope that you had a great time at your field school and that you had access to all the equipment you needed! The reason I’m choosing to address this now is because “What are some good field supplies for beginners” is probably the most asked question this blog, so I wanted to make a masterpost concerning field gear.

So this is my field kit, or like 80% of it. I’ve been doing this for over five years, but when i first started I had a small fraction of what you see here. I’m sure if I keep doing this job for another five years my kit will double in size.

Some field schools actually might provide you with supplies, or at least a list of what to bring. But if you plan on consistently doing archaeological fieldwork (ie actually working outside and not in a lab or office) then these five things are essential for your field kits:

Trowel (Obviously). Marshalltowns are the standard and the generally the easiest to get, but there are other brands such as WHS and Battiferro. I own both Marshalltown and Battiferro trowels and love both brands. My advice for trowels is that you should try to avoid getting a blade that is too big because it doesn’t allow you to have as much control over what you’re troweling. I wouldn’t go bigger than 4.5″

Folding ruler or tape measure. The unit of measurement is going to depend on the type of site. For prehistoric sites in the US and sites in the rest of the world, you will need a ruler using metric. For historic sites in the US you will need a ruler using tenths.

Brushes. Pretty self-explanatory. Although I personally don’t use brushes a lot they can be useful and every archaeologist owns at least one. A wider paint brush like this one is a good for novices.

Compass. If you’re a student going to a field school, then you won’t have to worry about bringing a compass. I only added it to the list of essentials because they are very important for Phase I surveys, which are a big component of non-academic archaeology. During Phase I surveys, you will have to hike several miles of land within a specific path of Limit of Disturbance (LOD). A compass will help you to stay on course when the LOD isn’t well-marked. A compass is also essential to setting up a site grid when you don’t have a total station handy. They are a very underrated piece of field gear and we hire a lot of newbies straight out of undergrad who get a rude awakening as to how necessary they actually are.

Pencils and Sharpies. These are like gold to archaeologists. You can never have enough of them because they ALL will be either lost or stolen.

Are you that person who has to be over-prepared for everything? Here’s a list of some additional gear you might want:

Bastard file, for sharpening your trowel. Now sharpening your trowel is a practice that is controversial in the archaeological community. It’s not a common practice overseas, and a lot of archaeologists will tell you to never sharpen your trowel because you could potentially damage the artifacts. But if you’re going to work in the clayey floodplain soils of the US, you aren’t going to be able to dig nice units without a sharp trowel.

Spoon. just a normal spoon. Spoons are really good for scooping up dirt crumbles in features which are too small and difficult for your trowel to access.

Line Level. for your datum string. You will use the datum string for measuring and drawing your site profiles, so it is very important that your datum line is level.

Wooden sculpting tools. If you know you’re going to be working with human remains or articulated faunal remains, then it will be good to get yourself a pack of these since the metal blade of your trowel is harmful for human bone.

Clippers. Roots are going to be the bane of your existence. Trust me.

So that’s your rundown of basic tools. Now let’s talk about what to wear.

Your choice of clothing is going to really depend on where you’re working, what you’ll be doing, and personal preference. Generally you’re going to be okay with a T-shirt and some cargo pants or hiking pants. If you want some extra protection from the sun you can get a handkerchief for your neck or a long sleeve shirt made from a light, breathable fabric. It’s not totally unheard of to wear shorts at a dig, but wouldn’t recommend doing so because you are going to be in the dirt on your knees a lot and you don’t want your bare knees on gravel for 8+ hours a day. If your knees are really bad, then it might be a good idea to invest in some knee pads for extra comfort. DO NOT be that basic bitch and wear leggings or yoga pants in the field. I would also recommend American students wear lighter colored clothing, especially if you will be working in wooded areas, so that you will be able to see ticks on you. Field schools are always during peak tick season and they get worse and worse every year.

Hats are going to be a personal preference. I’m partial to the baseball cap, but bucket hats work just as fine. Wide brimmed hats are great for extra sun protection, but not ideal for surveying several miles of land and shovel testing. At work I wear a baseball cap or a bandana, but when I worked in Turkey I wore a hat with a wider brim because the Mediterranean sun is absolutely brutal.

Shoes are also a matter of personal preference. I own a nice pair of hiking boots that I wear for work, but I have also worn sneakers to digs. You basically want a good shoe with a lot of comfort and support for your feet, and will hold up to 8+ hours of standing and kicking a shovel. If you’re like me and you’re prone to twisting your ankles, then you might want to consider getting some boots with ankle support.

Final thoughts about gear: Protect your phone from dirt by putting it in a plastic baggie, and protect yourself from the elements by bringing bugspray, sunscreen, and plenty of water.

Happy Digging!

~Amanda

126 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Here is an interesting array of Late Prehistoric arrowheads, some with multiple notches, from the Chan-ya-ta site (13BV1) in Buena Vista County. Chan-ya-ta was a fortified Mill Creek village site dating to just after A.D. 1000.

#archaeology#lithics#iowa#Prehistoric archaeology#north american archaeology#native american history#american indian

115 notes

·

View notes