Text

Four Years Later

Hi y’all! Today marks the fourth anniversary of my first post in this project, and I wanted to thank everyone who’s read through it (again (again (again))). Life is good! Just hit my first year at the "new" library, and prepping for the annual rewatch with my wife later in the fall (adult readers: consider pairing the show with mulled wine). Time flies!

Fourth anniversaries sorta feel like a drumroll to the Big Five; after all, I wrote these reviews for the fifth anniversary of the show, meaning it'll be the Big Ten for Over the Garden Wall next year! But it's the length of a presidential term, the span between leap years, and your average stint in high school or college. Plus in just three months this blog will have existed for longer than the Confederate States of America managed, which really puts the racists who claim it as their Very Important Heritage in context. Wirt's Union jacket approves!

I hope today's readers have an excellent Labor Day weekend, and future readers can think fondly on excellent Labor Day weekend memories. As ever, take care!

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Three Years Later

Hi y’all! Today marks the third anniversary of my first post in this project, and I wanted to thank everyone who’s read through it (again (again)). Man, what a year! Got married to my favorite person, we're back in the East Coast, just started a new job, and this October said person and I will be watching Over the Garden Wall once again; it'll be my eighth autumn with it, and her second, although she's been wanting to rewatch all year because spoiler alert she's a huge fan. Even roped in a few of her friends to catch Wirt Fever.

Not much to report on show update terms. Patrick McHale co-wrote the upcoming Guillermo del Toro stop motion Pinocchio movie where the story takes place in Fascist Italy, so that oughtta be weird! It has, as always, been a blast to get the occasional notification that folks are reading the archives throughout the year. COVID finally got me for a spell despite vaccinations, but it didn't hit too hard and somehow my wife still dodged it, so I suppose my sentiment til next September is to keep safe and healthy and don't take those things for granted! And as always, take care!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two Years Later

Hi y’all! Today marks the second anniversary of my first post in this project, and I wanted to thank everyone who’s read through it (again). It’s also been about half a year since I wrapped up Steven, Universally over on the other blog, and hoo boy have those months been eventful. Got engaged, got a dog, and moved to a new city for the first time in my adult life, all while the pandemic still just sorta keeps happening. Makes a guy wonder what the third anniversary will be like.

The fiancée watched and loved Steven Universe (not a dealbreaker if she didn’t, she’s pretty terrific, but it’s a heck of a bonus) so I can’t wait to show her Over the Garden Wall as soon as things stop being stupid hot. As Florence Welch ostensibly says every September First, the dog days are over, so here’s to hot chocolate and sweaters in our near future. Take care, folks!

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

One Year Later

“Dancing in a swirl of golden memories.”

Hi y’all! Today marks the anniversary of my first post in this project, and I wanted to thank everyone who’s read through it; I’ve gotten smatterings of notifications from this blog throughout the year, and it’s so cool to see folks enjoy it long after its completion. Only one major edit has been made since, and recently: with the passing of Joe Ruby in August, the introduction to Mad Love has been updated to note that he’s sadly no longer with us. Other than that, not much to add on the news front for a long-finished miniseries.

I hope you’re all doing well in a time where the unknown is scarier than it has been in quite a while. I structured Going Over the Garden Wall around two moments in my twenties when job insecurity fueled some of the worst depression in my life, and considering around half of the year since last September has occurred during a plague, I’m sure way too many folks now know how that feels. Every case is different, so I won’t pretend to understand what each individual circumstance is like, but if you’re struggling in the long term without knowing what to expect over the horizon, know that I’m rooting for you!

Over the Garden Wall won’t fix all your problems, but it’s times like this that I’m glad stories like it exist. Things might not always work out as well in the real world as they do in a cartoon, but even though it’s hard, I hope that when life is mucking up your path that you remember to eat your dirt. It might not taste good, but once you’re through it, life does get better. Good luck out there, and let this librarian know if you need any book recommendations to tide you over!

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 10: The Unknown

Life will always have its share of dirt. Mucking up situations that should be clean, obscuring the right path forward, piling up little by little until it threatens to bury you if you’re not careful. Part of growing up, maybe the biggest part, is figuring out what you’re going to do about it.

The Unknown presents two options. The first is sung by the Beast as he serenades Greg’s weakening form, heard as the Woodsman slowly enters the woods, first as purely diegetic music but soon joined by piano and strings:

“Sorrow and fear are easily forgotten when you submit to the soil of the earth.”

The second option comes from a surprising source, a character who never interacts with the Beast but whose advice is good enough that when push comes to shove, knowingly or not, Wirt takes it. It might not be phrased with the elegance of the Beast’s lyrical argument for surrender, but that doesn’t stop it from being Over the Garden Wall’s most important lesson:

“Eat your dirt.”

There isn’t a simple dichotomy between letting problems consume you and consuming problems: after all, actively seeking misery isn’t great for you. And The Unknown provides two major examples of why the generic “never give up!” message on its own is ultimately flawed: Greg and the Woodsman’s determination is noble at its core, but it blinds them to the reality that the Beast is deceiving them. With conviction must come critical thinking and self-awareness, because it’s otherwise impossible to break stubborn bad habits and seek healthier ways to solve problems.

In other words, the best way to handle difficulty is to fully digest it and grow stronger from it, rather than shovel it in and get sick. Don’t gorge on your dirt, but don’t submit to it, either. Just eat it.

While his long-running trick to keep the Woodsman in his thrall may be the Beast’s cruelest lie, the one that hits harder for me is his method of trapping Greg. We don’t need to see Greg’s adventures to understand the fairy tale logic that drove his quest, where a brave child is given three impossible tasks and overcomes them using his wiles. The Beast gives Greg victories to build his confidence, and those victories are based on guile, allowing Greg to feel like he’s got one over on the villain. Our hero is already in a bad way, and it’s heartbreaking to see him persevere like the Little Match Girl as the cold intensifies.

This message is fittingly hidden in an episode that showcases the full obfuscating power of the Beast. He’s able to twist truth and tropes alike to fit his needs: even something as basic as light representing the known and darkness representing the unknown gets warped, as the episode opens not in the usual shadows of the woods but a blindingly bright snowstorm. The Beast may be a creature of darkness, but this allows him to hide that his soul is a brilliant light. There’s an inescapable feel to the Beast’s machinations: neither the light nor the dark can save you from his lies.

We waste no time reuniting Wirt with Beatrice, and while we’ve had little time with the latter since Lullaby in Frogland, her search for her friends in the past few episodes is all we need to see to understand her desire to make things right. Wirt remains upset with her despite knowing that she saved his life, but is able to see the same fierce resolve to help that spurred him into the snow. Both of them are fueled by guilt and the need to make things right, so after a brief pause that speaks to how much her betrayal still hurts, Wirt takes her along and offers his thanks.

The third piece of the equation is introduced at the old grist mill, scrambling for more wood and finding the cracked stick he tossed away in our first episode. Like Wirt, the Woodsman is determined to save a loved one, and like Greg, his stubbornness allows him to be duped by the Beast. As a man who embodies both of the boys’ struggles, it makes sense that it’s from his perspective, not Wirt’s, that we first see the consequences of his actions. The singing that has haunted us since Songs of the Dark Lantern transitions to an eerily serene children’s choir as Greg is revealed to be covered in branches, and the horrible truth of the woods is made clear: like the suicides in Dante’s Inferno, the lost souls of the Unknown become trees.

What follows says everything about the Beast and the Woodsman alike. The Beast argues that his servant would have chopped the trees down even if he had known, assuming the worst in humanity, but even this reeks of more deception: if he truly believed that the lie was unnecessary, why lie in the first place? Either he knew that there was a risk in telling the truth and is manipulating the Woodsman now, or he had full faith that the Woodsman would do the unthinkable to help his daughter and is now reveling in his misery. Either way, the Woodsman’s doesn’t second-guess himself for a second, rushing to help Greg regardless of the consequences and renouncing his actions without hesitation. He meets every attempt at placation with fury, and shows that for all his faults, he truly did want to make the world a better place.

Only after the Woodsman and the Beast leave the scene do Wirt and Beatrice find Greg, guided by the same lantern that indirectly caused the kid to get captured in the first place. It’s a harrowing scene even when you know everything will work out okay, but it was especially disconcerting in first viewing: looking at it from a big picture, it was always unlikely that the show would actually allow Greg to die, but it was still possible, considering how close to death the boys are in the real world, how close to death Greg is here, and that Over the Garden Wall was already established as a finite miniseries with this episode as the conclusion. Greg coughing up leaves might be waved off as a joke, showing that he’s still got that childish sense of silliness, but it’s still a gruesome image given the circumstances. The Latin translation of Potatoes and Molasses sung in the background sounds like a ridiculous idea on paper, but turning a joyous highlight of Greg’s journey into a dirge that’s subsumed by the same eerie children’s choir as the Beast’s song works horrifically well.

But what sells the scene more than anything is the acting. Collin Dean layers Greg’s signature earnestness with exhaustion and pain, wringing sincere emotion from lines like “I’m a stealer” (which isn’t a bad line, but requires an actor of Dean’s skill to not come across as distractingly cutesy). Melanie Lynskey only has one major line in the scene, but her frantic confirmation that leaves are growing inside Greg amplifies the horror without gilding the lily, which isn’t easy when a character is telling us what we’re already seeing. But the absolute knockout comes from Elijah Wood, barely holding Wirt together as he struggles to comfort and free his brother. The guilt over getting Greg into this mess seeps out as Wood’s voice cracks and he forces himself to present a reassuring front.

Even this conversation, where Wirt owns up to his mistakes and takes responsibility for wronging Greg, is shrouded by the miscommunication that has plagued these characters throughout the series. Beyond the false alarm of Greg’s leaves, Wirt thinks Greg is apologizing for all the things Wirt blamed on him, when in fact he’s apologizing for stealing the Rock Facts Rock. Which adds an extra layer of tragedy when Greg appears to succumb after the brothers hit the same wavelength at last, after Wirt, not Greg, gives their frog a proper name.

Like Greg in Babes in the Wood, Wirt isn’t frightened when he first meets the Beast: both brothers are more focused on how to help the other when introduced to the show’s villain. Wirt’s concern is so great that he dismisses the Beast outright until he’s offered a deal to help Greg, and we see that as much as he’s grown, the old Wirt is still a part of him. For a moment, he allows hopelessness to guide his actions, assuming as he has before that things won’t turn out well. But that signature dithering makes a triumphant return as he changes his mind, impetuously calling the Beast’s plan “dumb,” because at long last he’s gained a greater sense of awareness. A version of Wirt as trapped in his own head as he was in Into the Unknown might’ve taken up the Woodsman’s burden, but this version of Wirt is finally wise enough to not believe his lies.

The Beast’s game is up the moment Wirt stumbles onto the lantern’s secret. Sure, he can put on a terrifying display of darkness, but a monster powered by deception is powerless against the truth. The Beast may succeed in scaring Wirt, but even if his voice cracks the first time around, all it takes is confidently calling a bluff to render the Beast helpless. And I love that this defeat ends all of the deception in the scene, even Wirt’s: he’s putting on a show when he tries for a badass one-liner before blowing out the lantern, but his derisive “pfft” at the Beast’s pleas is legitimately badass. What’s more, his secret possession of Adelaide’s scissors is revealed, the Woodsman realizes that his daughter’s soul was never in the lantern, and the Beast, already defeated, has his true form cast into a harsh light for one last scare.

(I’m not including the image because I think his true form has a lot more power as a glimpse, so here’s a picture of what happens next.)

The ambiguity of our return to the real world is something I cherish too much to try and make definitive claims over the “actual events.” Attempts to decipher the true nature of the Unknown sorta miss that the place straight-up tells you what it is by name. We can’t know whether it’s an alternate dimension or a dream with weird real-world implications or a time warp or literal magic or whatever, and it frankly doesn’t matter. What matters is that when Wirt awakens, he rushes down to Greg instead of swimming up: regardless of what happened or didn’t happen in the Unknown, Wirt has transformed from a child who blames others for everything to a young man capable of selflessly saving a life.

Shirley Jones’s voice breaks me as we see these kids struggle to survive the aftermath of their near-drowning, adapting Beatrice’s theme to a lullaby as her false promise to take the boys home is fulfilled. Yes, we see the bell ringing within Jason Funderburker as Jason Funderberker confuses his relevance in the story, but it’s more important that Wirt calls the frog “our frog” and works up the nerve to ask Sara out. Greg is back to his old self, happy as a clam, and Wirt has one last moment of babbling to show he hasn’t grown all the way out of his confidence issues. Even if we don’t know what the future has in store for them, we at least get the sense that everything is going to be okay as our second Jones takes the stage.

Jack Jones’s final montage shows the scenes that began our journey resolving in reverse order, with three endings in quick succession: Beatrice’s family restored, Jason Funderburker revealed as the singer, and Greg returning the Rock Facts Rock. Any one of these could work as the show’s true ending, as all three involve a different form of truth prevailing. Beatrice’s family is back to their true forms, and her mother tells us a truer means of dealing with dirt than the Beast ever did. The frog’s identity wasn’t much of a secret when given a little thought, as Jack Jones provided his singing voice in Lullaby in Frogland, but confirmation is still gratifying as the show’s final “mystery” is solved. And Greg represents “truth” in the sense of being true to oneself and just to others, while at the same time ridding himself of a tool he used to tell fun fibs.

And yet, some mysteries remain. We have no idea what really happened with the Woodsman and his daughter, especially because he’s apparently been grinding up trees for years. Considering Beatrice’s family seems to live at the mill, does this mean they’ve also been birds for years, or did the Woodsman only recently take it as a means of production? What’s up with the black turtles? Are the frogs on a wind-up toy steamboat launched by two boys? Questions abound without answers, and it’s okay that we don’t have them. Accepting that certain things will always be unknown makes it easier to move past our fear of it, a skill that none of us will ever need to outgrow.

I can speak firsthand to how tempting it is to let the weight of the unknown overcome you. In 2014, after realizing the path I’d committed to for years wasn’t going to end where I'd hoped, when I had no idea what the future had in store and the unknown was an overwhelming burden, the depression that had consumed my teens burst back into my life. I was incredibly fortunate to have parents willing and able to take me in, because I sincerely don’t know what I would’ve done to myself otherwise.

I spent the fall and winter with them as I tried to regain my bearings, but it took another stroke of fortune to really pull me back from the brink. Friends in New York offered me an open room in their apartment in March of 2015, and it’s impossible to overstate how much that shaped my life: hunting for apartments is hard enough without crippling despair, and it spurred me to get back to something resembling my old life. I started working at another bookstore, this time full-time, and in March of 2016 I applied to graduate school to become a librarian.

I was a school librarian part-time for the next two years as I went to library school, and absolutely loved it. I figured this would be my new path, but it turns out I wasn’t done with misplaced goals. Red flag after red flag sprouted up in the summer of 2018, and I was burnt all the way out after grad school and the grueling teacher’s licensing program, so I ended up turning down a sketchy-looking but secure job before the start of the schoolyear. I assumed I’d be able to find a public library job soon enough, a job that would allow me to work with other librarians rather than acting as a one-person library department: I had years of experience, I graduated from a school with a good local reputation, and I just plain knew what I was doing when it came to working with kids.

It wasn’t until March of 2019 that I finally landed at the job I have now. That’s a very short sentence for another very long fall and winter in my life, with numerous false starts and empty promises and a return to the feeling of total failure from 2014, now with the bonus of intense graduate school loans. It took two more existential crises than I would’ve liked, but I found my place and my people just in time for my twenties to finally be over. The dirt didn’t stop coming after my first career misfire, and I’m sure it won’t stop after the latest one, but I can’t tell you how grateful I am that I didn’t submit to the soil of the earth.

Eat your dirt, folks. Take care.

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 9: Into the Unknown

A boy named Mark was born on April 26th, 1976, fourteen years and one day before a boy named, uh, me. We’re both Virginians, but he moved to Florida as a kid while I stayed in the Old Dominion through college. Summers in Virginia are hot and humid and full of mosquitoes, which is why I love winter so much, but summers in Florida are so much worse. Despite that, Mark was an outdoorsy kid, and his adventures along the water inspired a literal dream he had around the time I was born about going on adventures across the seas, a dream that saw him start to make up stories about this alternate self. (I had nothing to do with it, we’ve never met and even if we had I wasn’t a particularly inspirational baby, but after so many introductions about animators of the past, it’s neat to think about how recently this last bit of history spans).

Mark moved to Utah in high school, and his swashbuckling appearance and attitude reminded his new classmates of Thorpe, Errol Flynn’s character in The Sea Hawk (as one of my sources helpfully notes, the reference to a 1940 film is likely due to the more conservative leanings of early 90s Salt Lake City making older films movies more popular). It’d be weird enough for “Thorpe” to become a lifelong nickname based on this tenuous connection, but the nickname Mark ended up with is actually a mispronunciation of name that I guess nobody felt the need to correct. High school, am I right?

Thurop Van Orman began his career in animation as an intern at Cartoon Network, and parlayed that into storyboarding gigs for The Powerpuff Girls and The Grim Adventures of Billy and Mandy. He learned from the likes of Craig McCracken as he honed his idea into a pitch for a show about a kid like him who loved capers on the high seas, and in 2008, the stories inspired by his childhood dream became a cartoon. For two years and three seasons, The Marvelous Misadventures of Flapjack not only entertained with its hilarious and surreal escapades, but incubated a crew of animators that shaped the 2010s.

J. G. Quintel, creator of Regular Show? Flapjack alum. Peter Browngardt, creator of Secret Mountain Fort Awesome and Uncle Grandpa? Flapjack alum. Alex Hirsch, creator of Gravity Falls? Flapjack alum (who brought Thurop in to voice the villainous Gideon). Pendleton Ward, creator of Adventure Time and Bravest Warriors? Flapjack alum, and his continuation of the Flapjack style of storytelling, where writers doubled as storyboarders, would shape Adventure Time alum Rebecca Sugar’s own methodology as she created Steven Universe. This would not be Thurop’s only “grandchild,” as the likes of Bee and Puppycat, Clarence, OK K.O., Summer Camp Island, and Infinity Train were all created from alums of shows created by Flapjack alums, and we’re even starting to see great-“grandchildren” like Craig of the Creek and Victor and Valentino.

But I left out one Flapjack alum who worked with Ward to develop Adventure Time from a viral short with a ton of potential into a sustainable television show, becoming the show’s creative director for the first two seasons. His name was (and still is) Patrick McHale, and in October of 2011, he started working on a pilot of his own.

“The river runs cold, the fight is over; still, the haunted ruins of night call your name.”

A trope that I’ve never been fond of when it comes to twists is when flashbacks are used to remind us of the foreshadowing or give old scenes new context. It can work in the right circumstances, but more often than not it shows a certain lack of trust, either in the audience for not paying attention or in the material for not being memorable, and it sucks the joy out of rewatching the story to catch hints for yourself. I much prefer a twist that maybe gives us a moment to take it all in (which is frankly pretty easy to do, all it takes is a character who’s as stunned as we are to allow us that time to process), and believing in us to understand the ramifications of this twist on our own.

Into the Unknown thrives in its bluntness. There’s no attempt to be clever about the reveal that Wirt and Greg are of our world in the late 20th century, we just begin right away with Wirt wearing semi-modern clothes in a semi-modern bedroom fumbling with a semi-modern cassette, all to the backdrop of a semi-modern-sounding song sung by Pat McHale himself. His actions are confusing at first to match our own initial confusion, creating the outfit we’re familiar with by taking the coat from an old-timey uniform and cutting the fluff off a Santa hat and putting on a fan to let his cloak billow in the wind (it helps that we already know he’s a weird and overdramatic kid). But our questions answer themselves with time: it’s Halloween, Wirt’s planning on giving his crush a mixtape, and Greg's series-spanning kettle hat is just his glorious take on an elephant.

This is Wirt pre-development, so he’s back to the dithering and the abysmally low confidence and the open hostility towards Greg; the last of these makes a comeback when he reaches peak despair, but even while depressed he's moved beyond the crippling indecision of his early adventures (although certainty in one’s looming demise isn’t much better). Still, even this early on we can see that he’s not a lost cause. He might get lightly teased by the first teens we see, but his appearance at the party reveals that he’s liked by plenty of his classmates, and Sara’s mutual crush is immediately obvious: his biggest enemy is his lack of self-esteem. And while he loses his nerve as soon as he sees Sara the Bee, this wouldn’t be possible if he didn’t have nerve in the first place: the beginning of Into the Unknown, and thus the first chronological moments that we see of Wirt, shows him getting out of a funk to take a genuine risk, one that fully merits him dropping the episode’s title on us.

The pursuit of Sara the Bee shifts us wildly from the dark atmosphere of the Unknown to classic teen comedy territory, where one crazy night can change everything. The stakes are fully personal for the bulk of the episode: Wirt needs to get his tape back to avoid embarrassment, and Greg wants to get the tape back so Wirt will hunt frogs with him. I like the detail that Wirt’s been flaking out on his promise and that Greg almost gets that he’s being blown off, but clings to that childish hope as he bulldozes through the barriers Wirt puts up for himself. Greg is first seen as a helper, doing chores for Mrs. Daniels for the candy he’ll use to make a trail in The Old Grist Mill instead of trick or treating, which implies a certain level of neglect: nobody’s around to take him door to door to get candy the proper way, and we don’t see him interact with any kids his age.

That said, the mood of the episode is definitely more mellow than melancholy, with Wirt’s awkwardness earning laughs and cringes in equal measure. Sara is delightful as she assures Wirt (and parents in the audience) that the teens are gonna drink age-appropriate drinks and do age-appropriate stuff, and she’s got the best costume game of anyone, first as a mascot and then as a skeletal clown. The cops try for humor as well, and while it’s funny for us, their position of authority makes them terrible at telling jokes in a way that will come back to haunt us. This is the last bit of levity before the finale, and unlike Babes in the Wood, hindsight never taints its goofiness. Particularly because the greatest joke of the episode, and perhaps the series, is far more upfront about its larger story implications than Greg’s magical dream.

Jason Funderberker is an oddly central character in Over the Garden Wall, a figure of dread established midway through the series as Wirt’s impossibly perfect romantic rival and the eventual namesake of Jason Funderburker. We confirm that Jason is a big deal when Wirt talks to the girls at the big game; sure, most of the impact comes from his outsized reaction, but Jason is still presented as serious competition for Sara’s heart. After going full crisis mode at the thought of Jason and Sara listening to his tape, we get a red herring of sorts in Jimmy the Jock. He certainly fits the “total package” bill that Wirt promised: a kind hunk who clearly respects women’s boundaries but warns Wirt off spying on Sara rather than trying to display his machismo through force. All signs point to a hopeless situation until finally, with perfect comedic timing, we meet the man in question.

It’s not just that Jason Funderberker is small and scrawny, or that his outfit and hair are pretty dorky (that said, let’s consider the source): it’s that damned voice. He’s given an absolutely perfect grating squeak from Cole Sanchez, yet another Flapjack alum who took over as creative director on Adventure Time after McHale moved to New York. The idea that this dweeb is the object of Wirt’s unending jealousy is an amazing punchline by itself, but as I said, the larger story implications are immediately clear, because there’s one thing that truly separates Jason from Wirt: confidence.

Jason might not be the most conventional ladies’ man out there on paper, but unlike Wirt, he’s capable of making a move. He’s as blind to Sara’s lack of interest as Wirt is to Sara’s active interest, but dammit, he tries. And he doesn’t even try in a gross or intrusive way, handling Sara’s implicit rejection well enough and ending up holding hands with his bespectacled admirer in our final episode. Literally all it takes for Wirt to “compete” with this guy is an ounce of self-assuredness, so it tracks that his journey through the Unknown achieves just that.

The Unknown might be another realm that these brothers have yet to face, but our understanding of it seeps throughout the episode. There’s the obvious reference to the show’s title as the pair climbs over the wall of the Eternal Gardens cemetery, and the grave of Quincy Endicott in said cemetery, but it’s also felt in the inability for Wirt to see the truth that he’s well-liked and that Sara definitely likes him back. It’s in the recurring bird imagery, with one girl dressed as an egg (who, and I noticed this for the first time in this watch, is voiced by Ashly Burch!) and another as a bluebird. It’s the fact that we’ve got disguises in general because it’s Halloween, considering the sheer amount of characters who aren’t what they appear in the Unknown: Enoch is really a cat, the gorilla is really a circus performer, the ghost is really a tea magnate, the huge singing frog is really our heroes huddled under a big coat, and the devourer is the sweet girl rather than the witch.

The most straightforward character, of course, is Greg. To be as fair to Wirt as I can be, his little brother does throw a wrench in things when he can’t stop giving the girls hints about Wirt’s crush, which sets off the chain reaction leading to what appears to be a disastrous night, so if you squint hard enough, Wirt isn’t wrong to blame the kid for his troubles. But without Greg, Wirt never would’ve gotten the courage to talk to Sara, and he certainly wouldn’t have entered the party uninvited. Greg’s willingness to engage perhaps needs to be tamped down in the same way Wirt’s needs to be amped up, as he has all the social skills of a little kid, but at least Greg has the excuse of, well, being a little kid.

More importantly, Wirt’s instinct to blame everyone but himself makes it impossible for him to see that he’s the one holding himself back. Acceptance and a relationship with Sara are right there in front of him, he just needs the courage to acknowledge it. Greg’s best bit of advice is that he join marching band, given he plays the clarinet anyway and it would allow him to spend time with Sara organically, but Wirt angrily dismisses the suggestion as interference while revealing that Greg’s father has given the same advice. It’s the second and final time we’re reminded that these two are half-brothers, but only now do we bring up that there’s distance between Wirt and his stepfather that seems to be one-sided. As per his song in our fourth episode, Greg was born after Wirt’s mom remarried, so his stepdad has been his stepdad for a significant period of time by now, but Wirt still venomously refers to him as “your stupid dad” as if he’s a stranger, even though the guy is ostensibly encouraging Wirt via his interests. Sure, there could be plenty more to this story that we’re not seeing, maybe the guy’s a huge pushy jerk, but Wirt’s refusal to consider good advice cements his inability to allow himself means of being happy, which of course ensures that he’s never going to be happy.

Which is what makes the ending of Into the Unknown so perfect. After finally finding their frog, the old black train whose whistle we hear at the beginning of nearly every episode nearly kills them, and as they tumble down a hill into the cold-running river foreshadowed by the episode’s opening song (and the opening sequence of the series), everything finally clicks into place: these boys are more lost than they realize.

But when Wirt awakens in the present surrounded by Beatrice’s family, he’s finally able to use the word “brother” to describe Greg. Over the Garden Wall began with a version of Wirt who failed to be heroic even when instructed to be, then moved to a version who could stumble his way through heroics on command, which evolved into a version who could perform heroics autonomously, but now we’ve gone above and beyond: this is a version who’s heroic even when others beg him not to be. We’ve wrapped all the way back around to disobedience, but this time it’s for the sake of helping others. And after dismissing and blaming Greg in the Unknown and the land of the living alike, it’s downright beautiful to see Wirt set off into the unknown once again, willing to put his life rather than his reputation on the line to save his brother.

Rock Factsheet

We come close to learning some valuable rock facts, but Wirt’s too distracted.

Where have we come, and where shall we end?

Beatrice’s mother appears only briefly at the end of the episode, but she’s voiced by musical legend Shirley Jones, and One is a Bird whispers its way out of the final scene. It was pretty much inevitable that Jones was going to sing it.

#into the unknown#over the garden wall#otgw#steven universally#thurop van orman#the marvelous misadventures of flapjack#pendleton ward#adventure time#patrick mchale

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 8: Babes in the Wood

In this last hurrah of explicit homages to animation of the past, the most obvious discussion point is Merrie Melodies and its ilk: Babes in the Wood is essentially a full-episode reference to the bouncing musical shorts of yore, where everything can sing’n’dance and the villain is a blustery bozo who’s defeated with a sight gag. If we expand to children’s entertainment in general, as we did with Greg’s Beatrix Potter episode, then The Wizard of Oz is our logical next step: the song welcoming him to Cloud City owes everything to Dorothy’s introduction to Munchkinland, complete with the fact that our hero has just entered a dream.

And look, there’s nothing wrong with talking about the obvious. But as we near the end, I think it’s a little more interesting to instead explore the very beginning. So let’s go back to a newspaper cartoonist in New York—the one who inspired fellow New York newspaper cartoonist John Randolph Bray to become an animator, which in turn led fellow New York newspaper cartoonist Max Fleischer to become an animator, because it turns out that just like the birth of superhero comics a few decades later, the birth of American animation hinged on print artists who dreamed big in the city that never sleeps.

A boy named Zenas was born in Michigan on September 26, 1871. Or maybe he was born there in 1869. Or maybe he was born in Canada in 1867. He said one thing, and a biographer said another, and census data says another, and I wasn’t there. It’s similarly unclear when or why he started going by his middle name, but by the time he took his first job at age 21 (or 19 or 17) as a billboard and poster artist in Chicago, he was calling himself Winsor McCay. They sure did know how to name ‘em in the 19th century.

McCay began his newspaper career as a freelancer, but moved to New York in 1903 to work for the New York Herald, where he wrote a variety of comics before hitting it big with Little Sammy Sneeze. McCay’s art was always brilliant, but his gag work was formulaic to a fault: the joke for Sammy Sneeze was always the same, he would sneeze and ruin everything right before the last panel. That devotion to formula would continue in his second big comic Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, where a fantastical events would occur for ever-changing characters before the lead woke up in the last panel, revealing it was a dream.

That second formula was the basis of McCay’s masterpiece. Already a successful cartoonist in the two short years since he’d moved to New York, his fame skyrocketed with Little Nemo in Slumberland, which used the same “wake up at the end” formula but with recurring characters and a running story. He toyed with the medium like none had before, playing with panel arrangement and innovating the portrayal of motion in comics, and his art skills only improved with this full-color strip. His success led to the vaudeville circuit, where he turned the act of drawing into a performance, and this combination of stage entertainment and his continuing comic work led him to seek new ways to dazzle the crowds.

By 1910, the earliest animated shorts had already started to emerge, and McCay was inspired by pioneers like James Stuart Blackton and Émile Cohl to try animating the characters of Little Nemo. Under Blackton’s direction, McCay singlehandedly drew around four thousand fully colored frames to produce his first animated cartoon, presented at the tail end of a filmed short about said cartoon in 1911. As mentioned, animated shorts were already a thing. But none of them looked anything like this. (If you’re concerned that there might be racist caricatures in it, don’t worry, there definitely are, McCay had a lot of strengths but overcoming garbage prejudices was not one of them).

The sheer quality of his work, continuing with the legendary Gertie the Dinosaur, directly led to the invention of the rotoscope as a means to mass-produce cartoons of similar finesse. The influence of Winsor McCay over animation as we know it is hard to overstate (and let’s stress again that this was his side gig, and he was just as influential over comic art): as crazy as it sounds, it’s safe to say that Over the Garden Wall would not exist if not for a story about the whimsical adventures of a little boy who traveled across a land of dreams from his bed.

“Where’s Greg, Wirt?”

Babes in the Wood is delightful and goofy and lighthearted exactly once.

In the same way our fourth-to-last episode mirrored our fourth, this third-to-last episode mirrors our third: Chapters 4 and 7 focus on Wirt, but 3 and 8 are Greg’s. It’s not simply a matter of who the main character is, but what these episodes are about: Greg’s love of fun clashing with his drive to help others. Both times he's spurred by the desire to help others to go off on his own, both times he gets distracted by whimsical wonders involving funny animals and physical humor, and both times he ends up deciding to help out anyway. But despite switching his goal from making the whole world a better place to just helping his brother, the stakes are actually far higher now, so the fun has to be that much more fun if we want the full horror of the ending to sink in.

There’s no tonal shift in the series that’s more devastating than Greg falling prey to the Beast after nearly ten minutes of goofiness in Cloud City. It turns a moment of welcome relief from the growing tension of Wirt’s despair into a dagger in the heart, and the knife is twisted when we learn in our next episode what the Unknown truly is.

That despair is evident well before Wirt explicitly gives up. We get our second opening in a row featuring Beatrice in a hopeless search, and things aren’t much better for the boys. All sense of progression from the first episode feels lost, with Wirt reverting to mumbling poetry and Greg reverting to Rock Facts. Their boat is an outhouse and Greg uses a guitar as an oar, because (if you’ll pardon my French) they’re up shit creek without a paddle. When they land, Greg’s victorious bugle is a ridiculous sign of hope, but he soon drops it in the same way he abandons the guitar: in Schooltown Follies he takes instruments to help others, but this time he loses them.

Wirt’s frustration with Greg threatened to boil over in The Ringing of the Bell, only to be cooled when the Woodsman interrupts them. This time there’s no such interruption, so after Greg’s total failure to read the room gets to be too much, his brother finally snaps. It crucially isn’t entirely unjustified, as Greg’s antics might be funny to us but have not been appreciated by Wirt, and despite Greg’s age excusing his lack of emotional intelligence, it’s still gotta be frustrating for a teen to deal with that behavior nonstop. And Wirt’s “tirade” reflects his depression, because he doesn’t even seem that angry: he doesn’t shout or rave, he’s just openly irritated as he argues that they’ll be lost forever. This is apathy and fatigue, because he’s lost the energy to be furious.

But the most chilling part of the exchange isn’t Wirt cruelly blaming Greg for their mess, or abandoning their search. It’s when, after Wirt asks if they can give up, Greg responds with a chipper “You can do anything if you set your mind to it!”, a sentiment that the Beast will fiendishly repeat verbatim while tricking Greg. It’s such a generic positive expression that Greg hangs a lampshade on it, but it shows the darker side of the power our minds have over our well-being. Sure, it’s a great lesson that focus and dedication can help us achieve our dreams, but if we use that focus and dedication towards self-destructive behavior, there’s no limit to how badly we can hurt ourselves.

After a goofy sort of prayer (incorporating lines from the classic Trick or Treat poem, which will become super relevant an episode from now), Greg is whisked away by so-creepy-it’s-funny cherubim to the score of a so-overwrought-it’s-funny song. His flight aboard the bed/cart pulled by a donkey across the sky feels legitimately magical, but we soon switch to the surreal world of 1930′s songs and physics.

Cloud City is such a stark contrast to the tone of the episode so far that it instantly feels delightful, and such a stark contrast to the tone of the entire series that it lends a special sort of wonder to Greg’s dreamland. References to old cartoons are everywhere in Over the Garden Wall, and before we delve into the tension of our last two episodes, we get one last gigantic celebration of the past with a sequence straight from the golden age of animation.

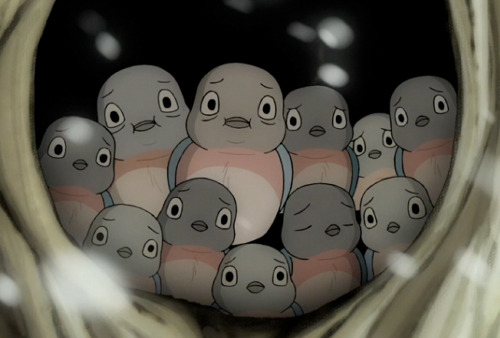

The transition alone is enough to make this scene hilarious, but the actual jokes help quite a bit: Greg’s growing impatience with the numerous Wizard of Oz reception committees is my favorite gag of the night. Everything is cute to the point of being cloying, including our three angels that look and sound an awful lot like Greg, and the parade that he leads seems like such a fun and peaceful affair after so much time wandering alone. It’s easy to get as roped into it as Greg when we first watch it. But considering the events of our next episode, the scene destroys me every time I rewatch it, because there’s a very specific place Greg is being welcomed to.

Babes in the Wood gets a lot less cute when it becomes clear that it’s a welcoming committee for a dying child. Greg and Wirt are drowning, and this is the episode where the shock wears off and the cold sets in and the younger and weaker of the two looks into a bright light. Greg’s near-death experience is hammered in when we get to The Unknown, but for now it’s being rationalized in a way that brings him comfort.

The cold is Greg’s enemy, and the same childish tone is used to show that he’s willing to fight for his life: thus, the North Wind segment is ironically more hopeful to me than the parade’s warm welcome of death. This third song sounds enough like a Randy Newman number that I’m honestly still convinced it’s an uncredited Randy Newman performance, and it jolts us back to reality for a moment as we see the effect this bitter wind has on our babes in the woods. The boys are starting to freeze, and we again see Beatrice searching for them, getting so close before an owl that looks remarkably like the one we saw in our first episode scares her off. The episode doesn’t want to lose us completely to the sky, and this grounding helps keep the stakes clear as we complete Greg’s dream.

The Popeye-esque battle between Greg and Ol’ Windbag is a hoot, between the latter’s grumbling anger and the former rolling up his sleeve to get back into the brawl. Its conclusion is hidden from us, so we have no idea how Greg gets him in a bottle, but that fits right in with the weird logic of this throwback and allows us to meet the Queen of the Clouds.

I ought to bring up the theory that everything we see here is an illusion created by the Beast, even though I don’t really subscribe to it myself. The most obvious “hint” is that this sequence directly leads to Greg deciding to join the Beast with an off-screen promise, but we also have the old man in the welcoming march wearing an outfit just like Wirt’s and holding a lantern, perhaps a reference to the Beast’s intended fate for Greg’s brother. Plus there’s lines in the songs that seem like they’re luring Greg in, especially the assurance that the wonders of Cloud City “ain’t gonna lie,” which sounds a lot like what a liar would say. Both the Queen of the Clouds and the Beast pointedly call him Gregory instead of Greg, but so does Old Lady Mrs. Daniels (and Wirt when introducing him in Songs of the Dark Lantern).

While it’s a neat enough idea, I think the Queen of Clouds is pretty clearly on Greg’s side for real: she seems upset at his fate in a way that doesn’t make much sense for an ally of the Beast. I also think it’s more meaningful for Greg to truly have the choice between happiness and responsibility, between the possible peace of rest and the definite struggle of life, and for him to choose the latter right as his brother is giving in. But I’ve got no beef with folks whose interpretation of the show is enhanced by this theory, so believe what you want to believe about this ambiguous situation.

Either way, we cut back to Wirt instead of Greg when the dream ends, and he’s still annoyed as he’s trying to sleep. Greg’s strange new seriousness is already cause for concern, and asking Wirt to take care of the frog is even more alarming, but even that doesn’t compare the horror of realizing where he’s actually going. Or rather, with whom.

This is another reason why I think the Queen is an ally: while it’s obviously dangerous for Greg to go with the Beast, that’s what it takes for Wirt to snap out of his funk. It’s a hell of a gambit, but as soon as he starts to awaken, he’s immediately concerned for Greg’s safety despite whatever anger or resentment he had, sparing no time or thought to the branches creeping over him as he runs after his brother.

The quiet distortion as we follow his frantic search is soon met by the Beast’s song, but even as he blames himself for Greg’s plight, Wirt is no longer content to wallow in despair. Because it turns out that these brothers are more similar than they seem, and neither is truly capable of letting the other suffer. In the folk tale for which this episode is named, two children abandoned in the woods eventually die and are covered in leaves by small birds (with some versions seeing them enter heaven), but as we’ll see in our next episode, this isn’t a folk tale.

The thrumming noise intensifies as Wirt slips on the ice, then we add visual distortion as he plummets into the freezing water. He’s saved, but this isn’t water that sees him reborn: the distortion finally breaks as Beatrice asks the episode’s terrible question, and we’re left in the cold.

Every even-numbered episode of Over the Garden Wall, perhaps by virtue of airing twice per night, ends in a mood-setting cliffhanger that grows tenser and tenser with every iteration (or at least it does until the end). First we got a leaf symbolically caught in a fence, then the Beast’s introduction, then the fallout of Adelaide, and now the capture of Greg. Getting trapped has always been a threat for these roving heroes, but the greatest threat of all, that of Wirt trapping himself, has been handled. Things look bleaker than they ever have, but despite the glee of Greg’s dream contrasting with the harshness of reality, Wirt’s ability to climb out of the pit of despair keeps hope alive: even in absence, Greg’s influence looms large.

Rock Factsheet

Dinosaurs had big ears, but everyone forgot because dinosaur ears don’t have bones.

Where have we come, and where shall we end?

Most of these were mentioned in the main analysis, but it’s great that we hear Wirt’s description of Into the Unknown right before the episode itself shows us what happened.

#babes in the wood#over the garden wall#otgw#steven universally#winsor mccay#little nemo in slumberland

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 7: The Ringing of the Bell

The history of animation that I’ve written about in these introductions can be more accurately described as the history of American animation. Which, sure, is humongous and revolutionary, but sticking to the States leaves out the first full-length animated film (1917′s El Apóstol, courtesy of Argentina) and the oldest surviving animated film (1926′s The Adventures of Prince Achmed, courtesy of Germany), as well as all the European predecessors to modern cartoons like the phenakistiscope or the zoetrope. But even that expansion limits us to the West, and although night has fallen on Over the Garden Wall, it’s time to look to the rising sun.

World War I shaped every aspect of global politics in the 20th century, and Japan was no exception. The Imperial Navy, already battle-tested in the Russo-Japanese War, developed into an unmatched force in the East whose influence lingered well after the Great War’s conclusion in 1918. A small part of that legacy was shaped by a boy born during the war, around the same time Max Fleischer developed his rotoscope. This boy, Katsuji, was fascinated with flight from a young age, and in another era, this might have led to a wonderful career in nonviolent aviation. Instead, the company Katsuji created in adulthood manufactured parts for the Zero warplane, which infamously attacked Pearl Harbor and launched the United States into World War II.

But this isn’t the story of how war turned a beautiful dream of flight into something twisted. It’s about how peace allowed a beautiful dream of flight to flourish into one of the greatest legacies in the history of animation. Because while 1941 might have ended with Katsuji Miyazaki’s creation leaving devastation in its wake, the year began with the birth of his second son.

Hayao Miyazaki was an artist from a young age, excelling early with detailed depictions of fantastical air machines but needing practice when it came to drawing people (spoiler alert, the practice paid off). He worked for cartoon giant Toei Animation out of college, where he met his lifelong partner in animation, Isao Takahata, and his lifelong partner in marriage, Akemi Ōta. He left Toei in 1971, but continued working with Takahata for a variety of studios, one of which allowed him to direct his first movie: The Castle of Cagliostro, a Lupin III movie that to this day proves that Miyazaki never needed the original characters or outstanding animation quality with which he’d become synonymous to produce an outstanding film. You don’t need to know a single thing about Lupin III to appreciate The Castle of Cagliostro, which I know because I didn’t know a single thing about Lupin III when I had my mind blown by The Castle of Cagliostro.

Still, Miyazaki had ideas of his own, one of which he developed into a monthly manga about a warrior princess with heavy environmentalist themes. In 1984, he worked with Takahata (alongside a composer Takahata found named Mamoru Fujisawa, better known by his stage name Joe Hisaishi) to adapt this comic, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, into a feature film. Something was clearly clicking, because the animators launched their own company with Hisaishi as an iconic collaborator: Studio Ghibli, named after a term for a hot desert wind that happened to also be the name of a WWII-era warplane.

The wind rose, and Studio Ghibli’s output soon became the stuff of legend: Miyazaki in particular has yet to make a film that isn’t spectacular. My personal favorite is Castle in the Sky, followed closely by that other movie about a warrior princess with heavy environmental themes, Princess Mononoke. But when it comes to influences on Over the Garden Wall, and particularly The Ringing of the Bell, it’s hard to see the story of characters lost in a strange world full of deception, with big-headed witches and hyper-specific rules for dealing with evil spirits, without thinking about the first Miyazaki movie I ever saw, back when I was young enough to be a little annoyed that I had to read subtitles: 2001′s instant classic, the startlingly magnificent Spirited Away.

“I’m glad you have a plan.”

As befits a Miyazaki Episode, breathtaking opening shots of nature ease us into The Ringing of the Bell, aided by a quiet piano to set a mood that’s somber, but not miserable. It might be a little generic for rain to accompany sadness, but despite our circumstances this isn’t Sad Rain: it’s a sign that life goes on, and the wandering continues through impediments great and small.

Wirt and Greg are back on the road, but now their roles from Schooltown Follies are reversed: this time Greg’s asking Wirt about his plan, and Wirt’s the one revealing he doesn’t have one. Sure, he doesn’t reveal it to Greg until the end of the episode, but it’s clear to us that he doesn’t know what to do. His irritation with Greg starts to swell up, but recedes for the moment as the Woodsman finally returns to straight-up tell us how the series is going to end.

The power of hope becomes the central topic of Over the Garden Wall in its second half, and despite his raving delivery, the Woodsman concretely warns the boys that losing hope is how the Beast can claim them. Unfortunately he’s still a terrible communicator, and the lingering idea that he might be the Beast is still in our heroes’ heads, so Wirt kicks himself loose and they escape, setting off the cleverest trick in The Ringing of the Bell: after gradually growing over the course of the series, Wirt is finally competent.

Everything goes as about as well as it can in this episode. Wirt’s idea to stay in the cabin leads to him lifting a curse from a new friend. His plan to escape Auntie Whispers by helping out with chores is solid, given the information available, and while Greg and Jason Funderburker are instrumental to the greater victory over the spirit—Jason by gulping down the hypnotic bell and Greg by figuring out how to use it—Wirt’s the only one smart enough to apply this strategy to its fullest. It’s a shame Greg’s never gonna see that magical tiger, but Lorna is freed thanks to Wirt’s superior command, and the fact that it’s a command is especially relevant because the bulk of Wirt’s heroic actions to this point have been commands he’s followed rather than given. As Greg says, Wirt saves the day twice. And if we count the day before, when his bassooning kept them on the ferry and he cut himself and Greg loose from Adelaide’s thread, that’s four heroic acts in the last 48 hours.

Moreover, this is the second consecutive episode where Wirt sings a duet, providing another glimpse of hope in his life as he does chores with Lorna. Considering we precede The Ringing of the Bell with two episodes where his feelings for Sara are brought up, I appreciate the realism of this new crush: it seems mutual, but both of these kids are awkward and nothing comes of it. It isn’t treated like a huge deal, because crushes flit up and diminish all the time in your teens, and we just move on after a pleasant but fleeting connection is made. By all accounts, Wirt has a pretty good day here.

But that’s the thing about depression, whether clinical or situational: it diminishes your sense of accomplishment and amplifies the bad. It’s brilliant that this episode makes Wirt the hero, because if even this can’t stop him from losing hope, perhaps nothing will. Hitting him with obstacle after obstacle might wear him down, but the bigger story only works if he’s his own obstacle. Auntie Whispers inadvertently taints his victory by warning him about Adelaide an episode too late, bringing him right back to Beatrice’s lies. He connects with Lorna, but their meeting is brief, leaving him on the road once more. In a healthier headspace he’d be able to find strength in his positive developments, but instead we set the stage for Babes in the Wood, where he truly gives up.

Speaking of Babes in the Wood, Greg solidifies himself here as a force for hope, believing with gusto that Wirt has a plan and encouraging him even after learning that he doesn’t. Greg has already forgiven Beatrice to the point where he takes as a given that they should wait for her, and when Wirt totally ignores his aside about how they shouldn’t enter the old cabin, he’s still game to follow along. And as mentioned, he’s key to the victory Wirt accomplishes: this is the third episode in a row where Greg has an idea to help folks out that Wirt ends up achieving, and their partnership only makes Wirt’s increasing annoyance harder to watch.

As is standard, Greg is also hilarious, particularly when it comes to his reaction to the eerie black turtles that caused their very first conflict with Beatrice’s dog (although “You can run and you can hide!” is perhaps his most delightful line). He pulls off the episode’s most difficult maneuver by finding humor in the act of plainly explaining a joke; Lorna being bad and Auntie Whispers being good is funny in the same way seeing the black turtles is funny, but in both cases, Greg goes for the more traditional meaning of “funny” and it works.

There’s plenty of humor in this episode to go around, though. Wirt gets some laughs of his own, and as humorous as Greg is, the delivery of the night belongs to Elijah Wood’s flabbergasted reaction to Lorna casually noting that Auntie Whispers isn’t a blood relative. But despite the comedy and the melancholy that follows, more than anything else this is a horror episode.

There are perhaps scarier elements of the series than Auntie Whispers even in this episode: Lorna’s horrific cursed form is certainly frightening. But I’d bet real money that if this had come out when I was a kid, Auntie Whispers would fuel the majority of my Over the Garden Wall-related nightmares. Visually, her inhuman proportions, jagged black teeth, and distorted pie-eyed pupils are bad enough; Patrick McHale based her appearance off an owl-like old man in a 19th century illustration, but there’s a distinct Yubaba/Zeniba feel to her in the same way Lorna’s evil spirit reminds me of No Face at his hungriest. Still, it’s Tim Curry, following John Cleese’s role as an established British ham voicing an old magical woman, that makes Auntie Whispers truly frightening. (Although, yeah, the name also helps, what an excellent campfire story witch name.)

Cleese goes full Cleese for Endicott and Adelaide, but Curry’s performance is chillingly subdued, and that tone is critical to the horror: an over-the-top delivery has its time in place, but it’s so much scarier to hear her matter-of-factly establish that unwelcome guests will be devoured alive. This attitude stems from having genuinely good intentions and speaking to Lorna’s actions instead of her own, but her calm is just plain terrifying when we think of her as the devourer (an image that isn’t helped when she devours a turtle alive). The accompanying piano only enhances her uncannily serene approach to sorting the bones of past victims and forcing Lorna to clean the house. It’s honestly effective enough that it still makes me uncomfortable on rewatch, when her true motives are known.

And of course, the Beast returns, solidifying our fourth-to-last episode as a mirror to our fourth, Songs of the Dark Lantern (both feature the Woodsman conversing with the Beast, both feature Wirt singing a song and saving a friend, both feature Beatrice getting left out, and both occur during rainfall). This time we see the Beast during the day, despite him being a creature lurking in shadow: not even the sun can protect us from his influence, which fits perfectly with Wirt’s bright accomplishments not helping his growing despair.

The Beast remains a menacing figure, but we again see him as a manipulator instead of a one-dimensional looming threat. He reminds us for the second time that the Woodsman’s daughter’s life is on the line, but this time does so with a cruel hypothetical question that falsely associates a lack of willingness to help capture two innocent kids with a lack of care for another child’s soul. The Woodsman, to his credit, doesn’t seem to buy it, but still sees no other alternative as the Beast tells another lie: that the only possible path is surrender.

It’s strange to think that we’re already wrapping up after just seven episodes of this miniseries. But as we build to the final confrontation with the Beast, we get a couple of lasts: this is is the last episode featuring a traditional encounter-of-the-day where the boys meet new characters together, and the last episode that ends with Wirt and Greg wandering the woods together. Because if we’re really aiming for despair, we have to go for the things we take as a given: namely, that these brothers are going to stick together.

Where have we come, and where shall we end?

In this, the definitive “these are modern kids” report: Wirt outright tells us that he’s, like, in high school.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 6: Lullaby in Frogland

Let’s look back. Way back. Back before the dawn of animation, before the dawn of film, well before Ruby or Spears or Disney or Iwerks or either Fleischer Brother. Back to 1835, in a town named Florida in a state named Missouri when a boy named Samuel was born.

Like Ub Iwerks, Sam was raised in Missouri. And like Max Fleischer, Sam’s family took a financial hit when his father’s work stopped (this time due to a premature death rather than the decline of tailory), giving Sam a practical approach to employment. He left school at age eleven to become a printer’s apprentice, then moved to his older brother’s newspaper as a typesetter and occasional columnist, writing humorous articles and drawing cartoons. But unlike Beatrix Potter or the animators we’ve covered, visual art wasn’t in the cards for Sam.

He moved to the East Coast to work for other papers, bouncing between cities before returning to the midwest to embark on a career he’d dreamed of since he was old enough to dream: piloting a steamboat. He thrived on the water, and kept writing about his work along the river, but everything stopped when the Civil War closed off the Mississippi. So Sam headed west to work for the same brother who once ran the newspaper, now a politician in Nevada (I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that this brother was for some reason named Orion). Sam tried mining, and it didn’t take, but he’d gotten pretty good at writing and set off for San Francisco to get back into his jocular brand of journalism.

It was here that he had his first success, a short story published in his paper called Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog. But, like a certain frog we’ve covered in this series, Sam wasn’t huge on permanent names. Within a month, the story was reprinted as The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, and Jim Smiley’s name was changed to Jim Greeley. Until the book version came out, when it was changed back to Jim Smiley. And this whole time, within the story, it’s a mystery whether Jim’s real name is actually Leonidas (it turns out that it isn’t, but it might be). None of this should come as a surprise for Samuel Clemens, who wrote under the names of Josh, Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass, and most famously, Mark Twain.

“I knew you were special.”

Over the Garden Wall is, among other things, a story about the importance of solid communication. After five episodes spent building up our heroes as a group of friends, all it takes is one episode of terrible communication to throw it all away. The specific issues vary, despite leading to a similar result of not verbalizing their thoughts very well: Greg’s youth stops him from articulating his rapidly changing ideas, Wirt’s anxiety leaves him too timid to speak up or too rambling to be clear, Beatrice’s true intentions make her obfuscate the truth, and Jason Funderburker straight-up can’t talk. Or so we think.

This time he’s named for American statesmen George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, which fits the continuing vintage Americana vibe of the series—while I figure it’s a coincidence, it should be noted that Mark Twain’s Jumping Frog was named after American statesman Daniel Webster. Surrounded by other frogs that walk around and wear fancy garb, our frog is more anthropomorphic than ever, standing on his hind legs and dancing along with Greg. But it’s still a shock to hear him open his mouth and sing, a shock that soon cedes to the realization that the frog playing the piano at the beginning of the series is singing the Jack Jones song in the montage that follows.

Lullaby in Frogland is Jason Funderburker’s episode through and through, so much so that it’s the first time we hear of his namesake, Jason Funderberker. This is an episode where Wirt rejects Greg’s assertion that their frog is “our frog,” a plot point that’s paid off in their last conversation in the series. This is an episode where Greg wonders aloud if he can be a hero, sees the frog set off on a diverging path immediately afterwards, and accepts it, because he’s willing to sacrifice his happiness for the good of others. And it’s an episode where the frog returns after a harrowing betrayal, showing that even when all seems lost, there’s still room for hope. Over the Garden Wall (the song) might not sound like a traditional lullaby, but it soothes us into a cold night as the sun sets on the first half of Over the Garden Wall (the show).

Adelaide’s true nature is foreshadowed by Beatrice’s sudden hesitance to bring the brothers to the pasture after several episodes of nagging, but the twist is made tragic by Wirt finally letting his guard down enough to be happy. He sings a completed Adelaide Parade with Greg and joins the dance before collapsing into the most earnest laughter I’ve ever heard in a cartoon. He’s a good enough friend to notice when Beatrice is “uncharacteristically wistful,” and takes a risk by playing the bassoon instead of just giving up. He’s still got growing to do—it’s one thing to blame Greg for getting them in trouble by throwing away the ferry fare and forcing them to sneak aboard, but another thing to literally shout “Take him, not me!” when confronted by the frog fuzz—so it’s clear that his journey isn’t over yet, but he doesn’t even get a full episode of peace before everything blows up.

The whole steamboat sequence flows between simple delights, like saluting the captain mid-chase, the revelation that the frogs love music more than they hate trespassers, and the repeated gags of three gentlemen frogs snatching up flying flies and a frog mother dropping her tadpoles. Everything just feels calm, even when antics are afoot. Wirt gets to save the day with his bassooning, Greg gets to feel rewarded in his knowledge that his frog is special, Jason gets to sing a song after being silent throughout the series, and Beatrice seems, for now, to come to a sort of peace about things after several clear attempts to sidetrack the boys. This is the only episode to feature two major stories instead of one, but the steamer segment is rich enough to feel like a full episode. If only we could’ve stopped here.

All roads lead to Twain when it comes to depictions of steamboats as a go-to American icon, which is why he preceded this discussion of Lullaby in Frogland: I’m not claiming Mickey Mouse wouldn’t have been successful if his first cartoon was about something else, but I’m certainly claiming that we wouldn’t have gotten Steamboat Willie as it was if Ub Iwerks hadn’t grown up in a Missouri whose lore was shaped by Twain’s tales of the river. But while the author is the root of the episode’s many influences, I think the most fascinating branch that we borrow from is The Princess and the Frog.

2009 was a great year for animation, seeing the release of Coraline, Fantastic Mr. Fox, The Secret of Kells, the surprisingly great Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs, and the first ten minutes of Up (also the rest of Up, if I’m feeling generous). The first two on that list are my favorite of the year, twin stop-motion masterpieces that I’m always in the mood to watch, but The Princess and the Frog is a brilliant last gasp from Disney’s 2D animation studio. It isn’t the final traditionally animated film they made (that would be 2011′s Winnie the Pooh), nor the final fully sincere princess movie they made (that would be 2010′s Tangled), but it marks the beginning of the end for both trends: for better and worse, modern Disney animation feels the need to loudly subvert old tropes and wouldn’t be caught dead in two dimensions.

Lullaby in Frogland’s connection to The Princess and the Frog is certainly visible on the surface level: both feature a long sequence starring frogs on a steamboat where a lead character must pretend to be another animal and play a woodwind instrument to get out of a jam, and both involve our heroes seeking help from a wise woman far from civilization (even if only one of these women is actually helpful). But it’s the somber nostalgia factor that binds these stories closer than anything, the knowledge that this is the end of the road for this type of tale. The ferry’s gotta land somewhere, and the cold is setting in as the frogs begin hibernating for the winter, but there’s still more story to tell.

The second story of Lullaby in Frogland is scored throughout by a haunting string and piano rendition of Adelaide Parade, and Adelaide herself is immediately captivating. John Cleese returns for the second episode in a row, but as both of these episodes aired the same night, it feels like a consistent through-line: in the first half, he’s an eccentric who might be a deranged maniac but is actually harmless, and now he’s a witch who might be harmless but is actually a deranged maniac.

Adelaide gets a compelling amount of detail for someone who’s barely in the show. We don’t get any explanation about her fatal weakness to...fresh air? Coldness in general? Either way, like the Wicked Witch of the West’s lethal reaction to water, it’s absurd that someone like her has managed to live this long. She never says what she needs a child servant for, why she has scissors that seem custom-made for Beatrice’s specific curse, or what her spider-like deal with yarn and wool is (she has a black widow hourglass on her back, but also reminds me of the Greek Fates with her emphasis on thread). We never find out how she’s connected to the Beast, whose theme bleeds into her music as she proclaims, without much prompting, that she follows his commands; her goal of using children as zombie slaves seems counter to his goal of turning them into trees to fuel his soul lantern. But this blend of unexplained characteristics and seemingly inconsistent motives only makes her more enthralling to me, because she feels like the major villain of another story who just happens to intersect with ours.

What makes Adelaide even more compelling on rewatch is that her scissors, despite their gruesome method for curing the curse, do end up working. Which means she did mean to help Beatrice out as part of the deal. At no point does Adelaide lie, and given Beatrice knows she’s bad news as she lures the brothers in, it becomes clear that for all her villainy, Adelaide is an honest witch. I’m always down for baddies that tell the truth, but it’s of particular interest when we compare her to the Beast, whose whole deal is lying.

The only liar in this episode is Beatrice, even if she wanted to set things straight without hurting anyone; she values her friendship with the boys so much now that she’d rather make herself a servant to Adelaide than just tell them she’s dangerous and reveal that she lied. By the time she’s willing to tell the truth, it’s too late, and not even saving Greg and Wirt by killing Adelaide is enough for Wirt to forgive her. Considering he knows in The Unknown that the scissors he uses to escape the yarn can save her family, he was also listening in on the end of the conversation before entering the house, which means he must have heard that she was willing to sacrifice herself, but that doesn’t matter either. Beatrice gave the boys hope, and no matter how badly she tried to stop it, the encounter with Adelaide transforms Wirt. Where he was once nervous and unsure, and was then briefly optimistic, he’s now sullen and untrusting.

But again, in comes Jason Funderburker, croaking and hopping on all fours once more to bring some light to the darkening series. He doesn’t do much for Wirt, but allows Greg to quickly get over whatever trauma he had about getting webbed up in yarn; he’s remarkably quiet about it, but it’s important to remember that he was betrayed, too. Whether he doesn’t understand exactly what happened or is just quicker to forgive, Greg is fine with Beatrice, allowing us to focus harder on Wirt’s reaction from now on.

It’s all rain and winter for Wirt until the end of his adventure. But the show isn’t content to leave him even slightly forlorn: when it gets too dark, he has a frog to swallow a lantern to light the way, and when it gets too cold, he has a brother to cover him in leaves, and when he falls, he has Beatrice to help pull him back up. Even the Woodsman tries to save him in his own way (talk about folks who are bad at communication). Bad things happen, and people make mistakes, but the bigger mistake is allowing that to close you off to others, or to never forgive friends that are genuinely sorry. Our heroes have taken the ferry to the other side, and now the story can shift to one about the folly of abandoning all hope.

Where have we come, and where shall we end?

On top of Jason Funderberker, who’s set up as a major rival to make his eventual reveal one of the show’s best jokes, Wirt gives Beatrice a general summary of Into the Unknown three episodes before we see it play out.

#lullaby in frogland#over the garden wall#otgw#steven universally#mark twain#the princess and the frog

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 5: Mad Love

So far, when going over brief histories of animators that have inspired Over the Garden Wall, I’ve written about pioneers like Ub Iwerks and the Fleischer Brothers (and maybe Walt Disney a little). Folks who were born well before cartoons on film were invented, and in some cases, before film itself was invented. By that metric, a story about two animators born in 1933 and 1938, both of whom were still alive when this post was first written, might not sound as impressive. But you don’t have to do something first to make a mark, and Joseph Clemons Ruby and Charles Kenneth Spears, two men from the first generation to grow up in the age of animation, mastered the art of converting the old into the new.

Ruby-Spears was founded in 1977, but came into its own in the 80s by producing the Alvin and the Chipmunk cartoon. Shows like this, based on preexisting material, were the studio’s bread and butter. Ever wanted to see a cartoon version of Mork and Mindy or Laverne and Shirley? A Mr. T cartoon? A Punky Brewster cartoon? A Police Academy cartoon? A Rambo cartoon? A cartoon called Chuck Norris: Karate Kommandos? Ruby-Spears had your back. Ruby-Spears brought video games like Q*bert and Frogger to television, and their penultimate production before shutting down in the 90s was the Mega Man cartoon. These shows varied in quality, to be sure, but just because something is derivative doesn’t mean it lacks value, as proven by the project that skyrocketed the careers of Joe Ruby and Ken Spears: while working for another duo, William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, Ruby and Spears took a dime-a-dozen ripoff assignment and instead created one of the most iconic cartoons of all time.

Ruby and Spears began in Hanna-Barbera’s sound department, but soon became writers on Space Ghost (most famous now for its Adult Swim parody decades later, a show derived from an old cartoon that was itself derived into shows like Sealab 2021 and Harvey Birdman). While waiting on a meeting with Barbera, an agent mentioned that the head of CBS’s daytime programming was interested in developing a teen rock band cartoon to capitalize on the success of teen rock band cartoon The Archie Show, with the twist that these kids solved mysteries. Ruby and Spears leapt at the opportunity, working with the studio’s veteran character designer Iwao Takamoto to create five teens who solved teen crimes to appeal to a teen audience: Geoff, Mike, Kelly, Linda, and W.W. (in all my research, I never found out what those initials stood for). Because the Archies had a huge gluttonous sheepdog named Hot Dog to be friends with the rail-thin gluttonous Jughead, the band starring in the newly-christened Mysteries Five had a huge gluttonous sheepdog named Too Much to be friends with the rail-thin gluttonous W.W.—but don’t worry, Too Much stood out by playing the bongos.