Text

• Operation: Body Snatch

Operation Body Snatch, which began on April 27th of 1945, just three days before Adolf Hitler’s suicide, was an operation by U.S forces to return the remains of Germany’s most celebrated rulers: King Frederick Wilhelm I, King Frederick the Great, and Field Marshall Paul von Hindenburg. To their proper burial locations.

On The 27th of April, seven members of the U.S. Army Ordnance Corp were searching the northern reaches of Germany’s Thuringian Forest – basically the middle of nowhere - for hidden ammo dumps. That is when they stumbled across a salt mine in Bernterode that had been used as a munitions manufacturing and storage facility. The size of this mine, that one reached it by taking an elevator down about 1800 feet – that’s about a 1/3 of a mile or ½ a kilometer from the surface. Down there, the men found an estimated 400,000 tons of stored ammo in its estimated 14 miles or 23 kilometers of tunnels. However there was an ever bigger surprise in store for them. About 1/4 of a mile or 4/10 of a kilometer from the elevator shaft, the soldiers stumbled across a side passageway that appeared to be sealed off with fresh cement. They decided to find out what was behind that newly mortared wall. They tunneled an opening through an estimated 6-feet or 2-meters of masonry and rubble.

It was a room that had been partitioned off into bays that were filled with artwork, boxes, and tapestries. An estimated 225 Prussian flags and banners were hanging unfurled. More importantly, everything surrounded four coffins, one of which was adorned with a large wreath and red ribbons with swastikas and bore the name Adolph Hitler. Upon closer inspection, they noticed that someone had quickly scribbled a few words in red crayon on each casket. Three of these were the remains of Germany’s most celebrated rulers: King Frederick Wilhelm I, King Frederick the Great, and Field Marshall Paul von Hindenburg. The fourth casket belonged to Frau von Hindenburg. These remains had been placed down in the mine about three weeks earlier as the Russians were closing in on Potsdam, the location of the Tannenberg Memorial. The Nazis feared that the Russians would destroy not just the monument, but also the remains that were buried there – those of Hindenburg and his wife. They quickly removed the caskets and blew up the remaining sarcophagi, ultimately finding their way, along with the two Fredericks, to the Bernterode mine.

It has been theorized that this room deep in the mine was set up to preserve the most precious artifacts of German military history for the next rise of the German Reich. The job of getting these four coffins and all of the associated regalia up and out of the mine became the responsibility of the MFA&A – or the Monuments, Fine Arts, & Archives – branch of the military. This was a group of 345 art historians, museum directors, architects, educators, and curators that hailed from thirteen different countries. Better known today as the Monuments Men. The coffins were the last objects to be removed from the mine. Frau von Hindenburg had the lightest casket and was the first one to take the fourteen minute ride up to the surface. Next was Frederick Wilhelm I, followed by Field Marshall von Hindenburg. The last coffin, however, was not going to return to the surface easily. Frederick the Great’s casket was massive and weighed over half-a-ton. In addition to being incredibly difficult to maneuver. To the surprise of the men accompanying Frederick the Great on his journey skyward, as they approached the surface they could hear a radio blasting the Star Spangled banner followed by God Save the King. Germany had just surrendered the war.

These four caskets created an incredible dilemma for the US Army. Three of these four caskets belonged to men that played a significant role in Germany’s military history. They couldn’t be reburied in just any ordinary way. On the other hand, to give each a grand burial with an ornate tombstone or monument could help bring the Nazi party back to life. So, the Army without certainty of what to do with the caskets quickly passed the responsibility on to the higher-ups in Washington, DC to deal with. Since the US government was dealing with the bodies of dignitaries, the issue was deferred to the State Department, the branch of our government that deals with international relations. For an entire year the coffins didn’t move from their guarded storage location in the basement of a castle in Marburg. Ultimately, it was decided that these bodies were of historical importance and should be treated just like any other historical treasure or artwork plundered during the war. This top secret reinternment of the bodies once again became the responsibility of the Monuments Men.

Three officers were assigned: Theodore Heinrich, Francis Bilodeau, and Everett Lesley Jr. It was Lesley that coined the name of this top secret mission: Operation Body Snatch. Their instructions were fairly straightforward. The two kings were to be reburied in the US controlled zone Greater Hesse, while the two Hindenburgs were to be buried near Hanover in the British Zone. Why Hanover? That’s because Hindenburg had requested that he be buried on his family plot there. It was Hitler who decided to override his final wishes and have his remains placed at the Tannenberg Memorial. The US was simply trying to respect Hindenburg’s wishes, but it was not to be. The British government wanted nothing to do with the bodies. Word came back from London that would not allow the bodies into their zone under any condition. So, they couldn’t be buried in the British or French zones. It became clear that all four bodies needed to be buried somewhere in the US zone. Since all four of these corpses were of the Protestant faith, it seemed logical to bury them in a Protestant church. That idea quickly fizzled after it was determined that all of the suitable Protestant churches were either badly damaged or totally destroyed in the war. The next step of the three Monuments men was to see if they could find a place, any place, that had even a slight connection to the Hohenzollern family. After careful research, the Kronberg castle near Frankfurt seemed like the perfect fit. Once again, luck was not on their side. The Monuments Men, Theodore Heinrich in particular, had a bigger problem thrown on their plate. Someone had stolen the jewels that had been hidden in the Kronberg castle. Valued at $7.6 million dollars in 1947 or about $77 million today, the great mystery of the theft focused worldwide attention on the castle.

Ultimately, the answer they had been seeking was hidden right under their noses: St. Elizabeth’s church in Marburg. The church had survived the war in good shape and lie just a few hundred yards from where the bodies were currently being stored. But, the real question was whether or not the church had any space left to bury the bodies. The three officers spent a considerable amount of time searching through the church’s burial records to locate possible burial spots. It was decided that the two Fredericks would be buried below the floor of the north transept, while the Hindenburgs would find final rest at the base of its north tower. Before moving forward with their plan, descendants of both families were consulted to seek their approval. The French would not allow Crown Prince Wilhelm, the eldest son of Germany’s last Emperor, to leave their zone, so a letter notifying him that his eldest daughter Cecilia. Getting Hindenburg family approval didn’t go smoothly either. They were to meet his only son Oskar in Wiesbaden, but he was a no-show. It turns out that he had been arrested by American security police for signing a Wiesbaden hotel register with his full military title. Once released, Hindenburg was taken to St. Elizabeth’s and granted his family’s approval for the reburial plan. The four bodies were finally laid to rest on August 19th of 1946, 479 days after they were first discovered deep down in that Thuringian mine. There was fear that fanatics may want to steal the bodies, so the graves were covered with steel plates and a layer of concrete. In September of 1952, the caskets of the two kings were moved once again. This time they were taken to Hohenzollern Castle in Hechingen where a family spokesman declared they were to remain “until Germany is united again and they can return to Potsdam.” When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the decision was made to do just that. On August 17th of 1991, the 205th anniversary of Frederick the Great’s death, they were interred one last time.

#ww2#world war 2#second world war#world war ii#wwii#history#spooky#germany#german history#monuments men#funny history#military history

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

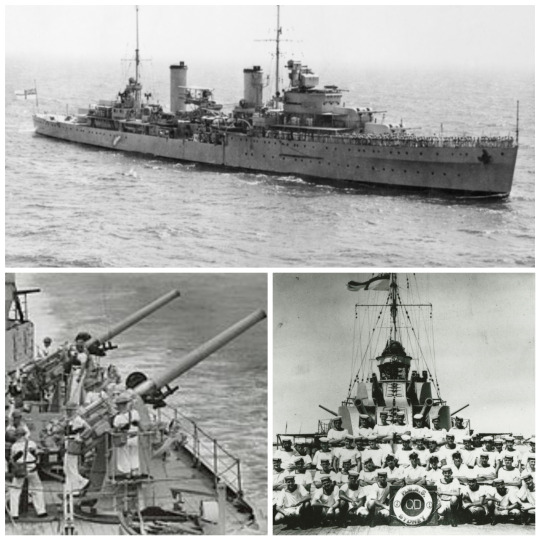

• HMAS Sydney

The HMAS Sydney, named after the Australian city of Sydney, was one of three modified Leander-class light cruisers operated by the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) during the second world war.

The ship was laid down by Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson at Wallsend-on-Tyne, England, on July 8th, 1933 for the Royal Navy as HMS Phaeton, named after the Greek mythological figure. However, in 1934, the Australian government was seeking a replacement for the light cruiser HMAS Brisbane, and negotiated to purchase Phaeton while she was still under construction. The cruiser was renamed after the capital city of New South Wales, and was launched on September 22nd, 1934 by Ethel Bruce, the wife of Stanley Bruce, former prime minister of Australia and the serving Australian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom. Sydney was commissioned into the RAN on September 24th, 1935, drawing her ship's company from Brisbane, which had been decommissioned earlier that day. Following the announcement that Australia was purchasing a British-built cruiser, there was criticism, primarily from the Opposition of the day, stating that such a warship should be built using Australian resources and labour. Several reasons were given in reply for acquiring British-built cruisers instead of Australian-made: the ship was already close to completion, the pending threat of war meant that there was not enough time to train Australians in the necessary shipbuilding skills, and that of the two cruisers built in Australian shipyards, one (HMAS Adelaide) had taken seven years to complete.

Sydney was one of three Modified Leander-class light cruisers acquired by the RAN during the late 1930s. Although the first ship of the class to join the RAN, Sydney was the second ship to be laid down, although the first to be completed, in what was sometimes referred to as the Perth class: Perth and Hobart operated with the Royal Navy for a short period before they were purchased by Australia in 1938. Like most British cruisers, the Leanders were designed for long-range patrols, scouting, and trade protection duties. Sydney's displacement ranged between 6,701 tons (light) and 8,940 tons (full load), with a standard displacement of 7,198 tons: improved fabrication and welding techniques made her 52 tons lighter than her sister ships. She had a length of 530 feet (160 m) between perpendiculars and 562 feet 4 inches (171.40 m) overall, a beam of 56 feet 8.5 inches (17.285 m), and a draught at standard displacement between 15 feet 3 inches (4.65 m) forward and 17 feet 3 inches (5.26 m) aft. The ship was propelled by four Admiralty 3-drum boilers, feeding Parsons single-reduction geared turbines, which supplied 72,000 shaft horsepower (54,000 kW) to the four propeller shafts. Unlike the first five Leanders, which had their machinery arranged on the "in-line" principle (consisting of six boilers in three compartments forward, and four turbines in two further compartments aft), Sydney was designed with two redundant machinery groups, a design practice adopted from the United States Navy.

Sydney and her sister ships were constructed from 1-inch (25 mm) hull plating, with a 3-inch (76 mm) armour belt over the machinery spaces (the lengthening of this belt from 84 to 141 feet (26 to 43 m) to adequately cover both spaces negated the weight reduction from their reorganisation), and 2-inch (51 mm) plates over the shell rooms and magazines. Sydney was the first Australian warship fitted with asdic; a Type 125 unit in a retractable pattern 3069 dome. The retractable sonar dome, located near the bow, was a weak point in the hull. One of the cruiser's early commanding officers, Royal Navy Captain J.W.A. Waller, believed that the ship's single director control tower was a weak point in the design. The director control tower was the highest compartment on the ship, from where personnel would determine the range and optimum firing angle for a gun salvo, then transmit this information to the gun turrets: the actual firing could be controlled from the tower or the turret. Although Waller suggested that a second tower be installed aft to provide redundancy, it was deferred indefinitely as subsequent commanding officers did not share his concerns, and combat experiences of other Leander-class cruisers showed that the system was more robust than expected. Sydney's main armament consisted of eight 6-inch (152 mm) breech-loading Mk XXIII guns mounted in four Mk XXI twin turrets: "A" and "B" forward, "X" and "Y" aft. All eight guns could be fired in salvo, elevated to an angle of 60° and depressed to −5°, and fire eight rounds a minute at targets up to 24,800 yards (22,700 m) away. Four 4-inch (100 mm) quick-firing Mk V guns, mounted on single, high-angle, Mk IV mountings, were fitted to a platform around the aft funnel. These were primarily used to target aircraft at heights up to 28,750 feet (8,760 m), but could also be used against surface targets, with a maximum range of 16,300 yards (14,900 m). Their replacement with eight Mk XIX high-angle/low-angle guns in four twin mounts, which was to occur in the late 1930s, was prevented by the outbreak of World War II. The guns could have been swapped out during a maintenance docking, but the demand for cruisers and Sydney's fortune in never sustaining major damage meant that the additional time in dock could not be justified. For close-range anti-aircraft defence, the 4-inch guns were supplemented by twelve 0.5-inch (13 mm) Vickers Mk III machine guns, which were arranged in three Mk II quadruple mountings, one on each side of the forward superstructure, and the third on top of the aft superstructure. Eight 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes were fitted in two QR Mk VII quadruple mounts to the deck below the platform for the 4-inch guns. Only eight Mark 9 torpedoes were carried.[31] Sydney was fitted with a single depth charge rail at the stern, which held five Mk VII depth charges. Four 3-pounder (47-mm, 1.9-in) quick-firing Hotchkiss guns were carried as saluting guns.

Sydney was fitted with a 53-foot (16 m), cordite-powered revolving catapult between the two funnels, which was used to launch a Supermarine Walrus (sometimes described as a Seagull V) amphibious aircraft. The Walrus was operated by Royal Australian Air Force personnel from No. 5 Squadron RAAF (which was redesignated No. 9 Squadron RAAF in 1939).

Sydney completed working up trials before sailing from Portsmouth on October 29th, 1935, Captain J.U.P. Fitzgerald RN in command. Almost immediately after departing, Sydney was instructed to join the Royal Navy's Mediterranean Fleet at Gibraltar and assist the 2nd Cruiser Squadron in enforcing economic sanctions against Italy in response to the Abyssinian crisis. During January 1936, the cruiser underwent maintenance in Alexandria and visited medical facilities in Cyprus: cases of rubella and mumps had been circulating through the ship's company since late 1935. In March, Sydney was reassigned the 1st Cruiser Squadron, where she and the heavy cruiser HMAS Australia continued to enforce sanctions and participate in fleet exercises with Royal Navy units. Following the resolution of the Abyssinian crisis, Sydney departed for Australia on July 14th; reaching Fremantle in late July before visiting Melbourne on August 8th and arriving in her namesake city three days later. After reaching Australian waters, Sydney spent most of her time on fleet exercises and training cruises. In 1938, the cruiser was one of several RAN units prepared to respond to the Munich crisis, but all ships stood down after the potential war was averted. From April 17th to 19th, 1939, Sydney was one of eight warships involved in a joint forces trade protection exercise off the south-east Australian coast. In early August 1939, Sydney was in Darwin, prior to visiting the Netherlands East Indies. However, in response to the events which prompted the start of World War II, Sydney was ordered to sail to Fremantle on a war footing, where she arrived on August 22nd.

Following the declaration of war, Sydney was instructed to carry out patrol and escort duties in Australian waters. Captain John Collins took over command of Sydney on November 16th. On November 28th, Sydney joined the Australian heavy cruisers Australia and Canberra in an unsuccessful four-day search for the German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee, which was known to be operating in the Indian Ocean. Sydney was relieved by HMAS Adelaide on December 13th, and sailed to Cockatoo Island Dockyard in Sydney for a maintenance docking. The work was completed in late January 1940, and as a shakedown cruise Sydney joined Canberra and the British ships Leander and Ramillies in escorting the Suez-bound Anzac convoy US 1; Sydney broke off after the convoy left the east coast of Australia and returned to Sydney. Returning to Fremantle on February 6th, Sydney relieved Australia as the cruiser responsible for patrol and escort duties on the west coast. On 19 April, Sydney joined the escort of Anzac convoy US 2 off Albany, and remained with the convoy until it reached the Cocos Islands on April 28th, and was replaced by French cruiser Suffren. The Australian cruiser set course for Fremantle, but in May was assigned to the East Indies Station and rerouted to Colombo, where she arrived on May 8th. Arriving in Colombo on May 8th, Sydney was immediately tasked with meeting Anzac convoy US 3 off the Cocos Islands and escorting it across the Indian Ocean. The cruiser departed on May 12th, but while en route, she was instructed to make for the Mediterranean.

The Australian cruiser, accompanied by HM Ships Gloucester and Eagle, departed the next day, with the ships crossing the Suez Canal during the night of 25–26th of May, and arriving in Alexandria that afternoon at 15:30. Sydney was originally marked for operations in the Red Sea, but after observing the performance of an Australian five-destroyer flotilla assigned to the British Mediterranean Fleet, Admiral Andrew Cunningham decided to "keep the Australian cruiser for himself" and attached Sydney to the Royal Navy's 7th Cruiser Squadron. Sydney was in Alexandria harbour on June 10th, 1940, and that evening learned of Italy's intention to declare war at midnight. By 01:00 on June 11th, all ships in harbour had departed to search for Italian warships in position to attack Alexandria, and secure the sea lines of communication in the eastern Mediterranean and Aegean. The Australian cruiser was involved in the westbound sweep, and sailed as far as the Gulf of Taranto during the four-day operation. Apart from an unsuccessful depth charge attack on a suspected submarine during the afternoon of June 13th, Sydney did not encounter any enemy vessels. On June 21st, Sydney fired in anger for the first time, joining the British cruisers Orion and Neptune, the French battleship Lorraine, and a force of destroyers in shelling the Italian-controlled Libyan port of Bardia. Sydney focused her fire on a military camp throughout the twenty-two-minute bombardment. During this operation, the Australian ship's Walrus amphibian performed bombardment spotting for the squadron, but was fired on by three biplanes: although reported at the time as Italian Fiat CR.42 Falcos, the attackers were later determined to be British Gloster Gladiators. The next day, a retaliatory airstrike against the ships, by then having returned to Alexandria, failed to do damage.

That same day, Germany and Vichy France signed the Second Armistice at Compiègne: although French warships (which had until that point operated with the Allies) were ordered to return to France and disarm, the British government was unwilling to allow them to fall into Axis hands. Sydney and the British warships in Alexandria turned their guns on the French, but unlike the situation in Mers-el-Kébir, which deteriorated into a naval battle, British Admiral Cunningham and French Admiral René-Emile Godfroy peacefully negotiated to disarm the ships at Alexandria. Sydney and other elements of the 7th Squadron sailed from Alexandria on June 27th, escorting a Malta convoy. Late on June 28th, the ships engaged a force of three Italian destroyers carrying out a ressuply mission to Tobruk. Although two Italian vessels were able to continue their way, the third, Espero was disabled. At 20:00, Sydney (which had little opportunity to fire during the engagement) was detailed to recover any survivors and sink the destroyer while the rest of the force continued on to Malta. However, while 6,000 yards (5,500 m) from Espero, the Italian ship fired two shells, both of which fell in line with but short of the cruiser. Sydney opened fire, and after four salvos struck the destroyer with no shots fired in return, resumed the approach. Espero sank at 20:35, and Sydney remained in the area for almost two hours to collect survivors despite the risk of submarine attack, before she was ordered to withdraw to Alexandria. The Australian cruiser spent five days in Alexandria for resupply and maintenance, before departing for Crete with the British destroyer HMS Havock. They arrived at sunset on July 18th, and the next morning, the two ships were ordered to patrol the Gulf of Athens for Axis warships and shipping, while providing support for a four-ship destroyer force (HM Ships Hyperion, Ilex, Hero, and Hasty) conducting an anti-submarine sweep north of Crete.

The only damage to Sydney during what came to be known as the Battle of Cape Spada was caused by a shell which knocked a hole in the forward funnel, and wounded a sailor through splinter damage. For his actions, Collins was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath, while other officers and sailors from Sydney received two Distinguished Service Orders, two Distinguished Service Crosses, five Distinguished Service Medals, and twelve Mentions in Despatches between them. Sydney herself was awarded the battle honour "Spada 1940". After refuelling and rearming, Sydney and HMS Neptune departed Alexandria on July 27th, to join the covering force for a southbound convoy from the Aegean. The ships were attacked five times that afternoon by aircraft, but Sydney escaped with only minor damage and shrapnel wounds. Back in Alexandria, Sydney underwent a refit, during which a 3-foot (0.91 m) high, 0.5-inch (13 mm) thick wall of armour plating was constructed around the 4-inch gun platform, while the ship's company repainted the ship from standard grey to a naval camouflage pattern. On the return voyage, Sydney and several other vessels were tasked with attacking Italian facilities. The entire Mediterranean fleet sailed from Alexandria on October 8th to provide cover for several Malta Convoys, and attempt to draw the Italian fleet into battle. The convoys reached their destination safely, and the operation was uneventful for Sydney; the only contact with Italian forces was an engagement during the early morning of October 12th, between the British cruiser Ajax and seven Italian torpedo boats and destroyers, of which Ajax sank three and damaged a fourth. No major incidents occurred until the 28th, when the Italians invaded Greece: the four ships were recalled to Alexandria, where they arrived that evening. On November 5th, Sydney and HMS Ajax departed from Port Said with military equipment to be used to establish an Allied advanced base at Souda Bay, Crete. After delivering the equipment, which included almost 1,000 soldiers, the equipment for a Bofors battery, cases of food, and several trucks, the cruisers rejoined the main fleet. From November 15th to 20th, Sydney and three other cruisers transported 4,000 Allied soldiers and their equipment from Alexandria to the Piraeus as reinforcements for the Greek military. Sydney started December in the Aegean, where she escorted convoys and shelled the port of Valona, then proceeded to Malta for a refit and repairs to her rudder, which lasted until the end of the year.

On the afternoon of November 19th, 1941, Sydney was off the coast of Western Australia, near Carnarvon, and heading south towards Fremantle. Around 15:55, the cruiser spotted a merchant ship on a northbound course, which quickly turned away from the coast at 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph). As she closed the gap, Sydney began to signal the unidentified merchantman, first by signal light, then after no reply was forthcoming and the distance between the two ships had decreased, by a combination of light and signal flag. The cruiser sent a request that the merchant ship make her signal letters clear, which the signals officer did by lengthening the halyard and swinging the flags clear. The callsign was that of the Dutch ship Straat Malakka, but she was not on Sydney's list of ships meant to be in the area. Further flag signals were exchanged between the ships, with Sydney asking the Dutch ship's destination and cargo. At 17:00, a distress signal was transmitted by Straat Malakka, indicating that she was being pursued by a merchant raider. Following this, Sydney pulled alongside the merchant ship from astern; pacing the merchantman on a parallel course, approximately 1,300 metres (4,300 ft) away. Sydney's main guns and port torpedo launcher were trained on the ship, while she sent the interior portion of Straat Malakka's secret callsign. Fifteen minutes later, at around 17:30, the merchantman had not replied, and Sydney sent a signal ordering her to show the secret callsign. Straat Malakka had not replied because she was the German auxiliary cruiser Kormoran in disguise, and when asked to reveal a callsign the Germans did not know, Kormoran responded by decamouflaging and opening fire. Prompted by the raider's unveiling, Sydney also fired (accounts are divided as to which ship fired first), but while her first salvo either missed or passed through Kormoran's upper superstructure with minimal damage, four of the raider's six 15-centimetre (5.9 in) guns (the other two guns were on the port side and could not fire to starboard) were able to destroy the cruiser's bridge and gun director tower, damage the forward turrets, and set the aircraft on fire. Sydney did not fire again until after the raider's sixth salvo: "Y" turret fired without effect, but "X" turret was able to put multiple shells into Kormoran, damaging machinery spaces and one of the raider's guns, while igniting an oil tank. During this, Kormoran maintained heavy fire, and around the time of the eighth or ninth German salvo, a torpedo launched at the start of the engagement hit Sydney just forward of "A" turret and near the ASDIC compartment (the weakest point on the ship's hull), ripping a hole in the side and causing the bow of the cruiser to angle down. By 17:35, Sydney was heading south and losing speed, wreathed in smoke from multiple fires. Her main armament was disabled (the two aft turrets had jammed on a port facing and could not be swung around), and her secondary guns were out of effective range. The cruiser continued to be hit by shells from Kormoran's aft guns as the distance between the ships increased.

The Australian cruiser continued on a south-south-east heading at low speed; observers aboard Kormoran doubted that Sydney was under control. Although disappearing over the horizon shortly later, the glow from the damaged, burning warship was consistently seen by the Germans until about 22:00, and sporadically until midnight. At some point during the night, Sydney lost buoyancy and sank: the bow was torn off as she submerged and descended almost vertically, while the rest of the hull glided 500 metres (1,600 ft) forward as she sank, hitting the bottom upright and stern first. Sydney's shells had crippled Kormoran; the German sailors abandoned ship after it was determined that below-deck fires could not be controlled before they reached the gun magazines or the mines in the cargo hold.Sydney's failure to reach Fremantle on November 20th was not initially cause for concern, as several factors might have delayed the cruiser, none of which were sufficient reason to break the order to maintain wireless silence. However, with no sign of the cruiser by November 23rd. shore-based wireless stations began transmitting orders for Sydney to break silence and report in. A raft of German survivors was recovered by a British tanker on November 24th, at which point a large-scale air and sea search began. Australian Prime Minister John Curtin officially announced the loss of the cruiser during the afternoon of November 30th. Sydney's destruction was a major blow to Australian morale and military capability: her ship's company made up 35 percent of the RAN's wartime casualties.

The battle between Sydney and Kormoran is seen as controversial: the disbelief that a modified merchant ship could so successfully defeat a cruiser combined with the lack of Australian survivors led some to believe that the German account was false. Rumours that the battle was not what it seemed had been around since Sydney failed to reach Fremantle on schedule in 1941, but several historians (including Tom Frame and Wesley Olson) credit Michael Montgomery and his 1980 book Who Sank The Sydney? with igniting the controversy. These claims have been proven false by historians and researchers; the 1998 inquiry by the Joint Standing Committee for Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade concluded that the German accounts were a "feasible" interpretation of the battle, but there was no reliable evidence to support any of the alternative claims. Sydney was located in March 2008 just after 11:00, only hours after Kormoran's discovery was made public.Sydney was granted the battle honour "Kormoran 1941" in recognition of the damage done to Kormoran. This was one of only three honours awarded during the 20th century for the sinking of a single ship, and the second to a ship named Sydney (the other had been awarded to the previous Sydney for her defeat of the German light cruiser SMS Emden at the Battle of Cocos).

#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#wwii#military history#history#ww2#australia#royal navy#australian navy#australian history#long post#naval history

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Léo Major

Léo Major was a French-Canadian soldier who was the only Canadian and one of only three soldiers in the British Commonwealth to receive the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) twice in separate wars. Major earned his first DCM in World War II in 1945 after a successful reconnaissance mission in Zwolle.

Born on January 23rd, 1921, in New Bedford, Massachusetts, to French-Canadian parents, Major moved with his family to Montreal before his first birthday. Due to a poor relationship with his father, he moved to live with an aunt at age 14. This relationship, combined with a lack of available work, led Major to join the Canadian army in 1940 to prove to his father that he was "somebody to be proud of". Major enlisted in the Canadian army when he was 19 years old and was sent overseas in 1941. One of Major's sons, said his father, a skinny and scrappy boxer and aspiring plumber, was drawn by the prospect of liberating Europe from fascism as well as a quest for adventure. For the next several years Major would receive reconnaissance training and would eventually be called up to be deployed as part of the Normandy landings.

Major was serving with the Régiment de la Chaudière which landed on the beaches in the Normandy Invasion on June 6th, 1944. During a reconnaissance mission on D-Day, Major captured a German armoured vehicle (a halftrack) by himself. The vehicle contained German communication equipment and secret codes. Days later, during his first encounter with an SS patrol, he killed four soldiers; however, one of them managed to ignite a phosphorus grenade. After the resulting explosion, Major lost one eye but continued to fight. He continued his service as a scout and a sniper by insisting he needed only one eye to sight his weapon. According to him, he "looked like a pirate". Major single-handedly captured 93 German soldiers during the Battle of the Scheldt in Zeeland in the southern Netherlands. During a reconnaissance, while alone, Major found shelter in a house from the rain and the cold. While there, he spotted two German soldiers walking along a dike. He captured the first German and attempted to use him as bait so he could capture the other. The second attempted to use his gun, but Major quickly killed him. He went on to capture their commanding officer and forced him to surrender. The German garrison surrendered themselves after three more were shot dead by Major.

In a nearby village, SS troops who witnessed German soldiers being escorted by a Canadian soldier shot at their own soldiers, killing seven and injuring some others. Major disregarded the enemy fire and kept escorting his prisoners to the Canadian front line. Major then ordered a passing Canadian tank to fire on the SS troops. He marched back to camp with nearly a hundred prisoners. Thus, he was chosen to receive a Distinguished Conduct Medal. He declined the offer to be decorated, however, because according to him General Montgomery (who was to present him with the award) was "incompetent" and in no position to be giving out medals. Whether he actually got this nomination and why he wouldn't have received it is not clear. The National Archives only has a record of Recommendations for Award for Major, which regards the DMC award he got in 1945 for the reconnaissance of Zwolle. In February 1945, Major was helping a military chaplain load corpses from a destroyed Tiger tank into a Bren Carrier. After they finished, the chaplain and the driver seated themselves in the front while Major jumped in the back of the vehicle. The carrier struck a land mine. Major claimed to have remembered a loud blast, followed by his body being thrown into the air and smashing down hard on his back. He lost awareness and awoke to find two concerned medical officers trying to assess his condition. He simply asked if the chaplain was okay. They did not answer his question, but proceeded to load him onto a truck so he could be transported to a field hospital 30 miles (48 km) away, stopping every 15 minutes to inject morphine to relieve the pain in his back.

After World War II he settled into civilian life as a pipe fitter, but he volunteered for service in the Korean War in 1950. In November of 1951, he was tasked to recapture Hill 355, which had been taken from American troops by the Chinese army. Taking a group of about 20 other snipers and scouts, Major and his men infiltrated the Chinese camps and commenced firing, scattering the Chinese army. For three days they held the hill against counterattacks, sometimes calling down supporting artillery fire so close to their position that their commanding officer could hear the bombs exploding through the walkie-talkie. Major was awarded a bar to his Distinguished Conduct Medal for this action. After his military career, Major returned many times to the town of Zwolle, establishing close ties with the townsfolk and having a road named after him. He is buried at the Last Post Fund National Field of Honour in Pointe-Claire, Quebec. Major died in Longueuil on October 12th, 2008 at the age of 87, and was buried at the Last Post Fund National Field of Honour in Pointe-Claire, Quebec. He was survived by Pauline De Croiselle, his wife of 57 years; four children; and five grandchildren. A documentary film about his exploits, Léo Major, le fantôme borgne, has been produced in Montreal (Qc). To commemorate the 75th anniversary of Victory in Europe.

#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#wwii#military history#history#ww2#biography#canadian history#snipers#unsung hero#badass history#canada#leo major

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Battle of Memel

The Battle of Memel or the siege of Memel was a battle which took place on the Eastern Front during World War II. The battle began when the Red Army launched its Memel offensive operation in late 1944.

The Soviet Belorussian offensive of June–August 1944 (commonly known as Operation Bagration) had seen the German Army Group Centre nearly destroyed and driven from what is now Belarus, most of what is now Lithuania and much of Poland. During August and September of that year, a series of German counter-offensives – Operations Doppelkopf and Casar – succeeded in stalling the Soviet advance and maintaining the connection between the German Army Groups Centre and North; however, Stavka made preparations for an attack by the 1st Baltic Front against the positions of the Third Panzer Army and thence towards Memel, splitting the two Army Groups. Soviet General Bagramyan planned to make his main attack in a 19 km sector to the west of Šiauliai. He concentrated up to half of his entire force in this area, using concealment techniques to ensure there was not a corresponding build-up of German forces, and attempting to convince the German command that the main axis of attack would be towards Riga.

On October 5th, Bagramyan opened the offensive against Raus's Third Panzer Army on a sixty-mile front, concentrating his breakthrough force against the relatively weak 551st Grenadier Division. The latter collapsed on the first day, and a 16 km (10 mile) penetration was achieved; Bagramyan then committed Volsky's 5th Guards Tank Army to the breach, aiming for the coast to the north of Memel. There was a general collapse of the Third Panzer Army's positions by October 7th, and a penetration further south by Beloborodov's 43rd Army. Within two days, it had reached the coast south of Memel, while Volsky had encircled the town from the north. In the south, the northern flank of Chernyakhovsky's 3rd Belorussian Front was advancing on Tilsit. Third Panzer Army's headquarters were overrun by the 5th Guards Tank Army, and Raus and his staff had to fight their way into Memel. The neighbouring Army Group commander, Ferdinand Schoerner, signalled on 9 October that he would mount an attack to relieve Memel if troops could be freed up by evacuating Riga. A decision on this matter was delayed, but the Kriegsmarine managed to withdraw much of the garrison and some civilians from the port in the meantime. The German XXVIII Corps under Gollnick held a defensive line around the town itself. The success of the offensive in the northern sector encouraged the Soviet command to authorise the 3rd Belorussian Front to attempt to break through into the main area of East Prussia. This offensive, the Gumbinnen Operation, ran into extremely strong German resistance and was halted within a few days.

The stalling of the Gumbinnen Operation meant that Soviet forces (mainly from the 43rd Army) settled down to a blockade of the German troops that had withdrawn into Memel. The German force, largely made up of elements from the Großdeutschland and 58th Infantry Divisions and the 7th Panzer Division, was aided by heavily fortified tactical defences, artillery fire from ships (including the Prinz Eugen) in the Baltic, and a tenuous connection with the remainder of East Prussia over the Curonian Spit. The blockade, and defence, was maintained through November, December and much of January, during which period the remaining civilians who had fled into the town, and military wounded, were evacuated by sea. During this time, the Großdeutschland and 7th Panzer Divisions were withdrawn, having suffered heavy losses, and were replaced by the 95th Infantry Division, which arrived by sea. The town was finally abandoned on January 27th, 1945. The success of the Soviet East Prussian offensive to the south made the position of the bridgehead untenable, and it was decided to withdraw the XXVIII Corps from the town into Samland to assist in the defence there; the remaining troops of the 95th and 58th Infantry Divisions were evacuated to the Curonian Spit, where the 58th Division acted as a rearguard for the withdrawal. The last organized German units left at 4am on January 28th, Soviet units taking possession of the harbour a few hours later.

Memel, which had been part of Lithuania only between 1923 and 1939 prior to being reincorporated into Germany, was transferred to the Lithuanian SSR under the Soviet administration. In 1947 it was formally renamed using the Lithuanian name, Klaipėda.

#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#wwii#military history#history#german history#ww2#russian history#soviet union#lithuania#1944

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

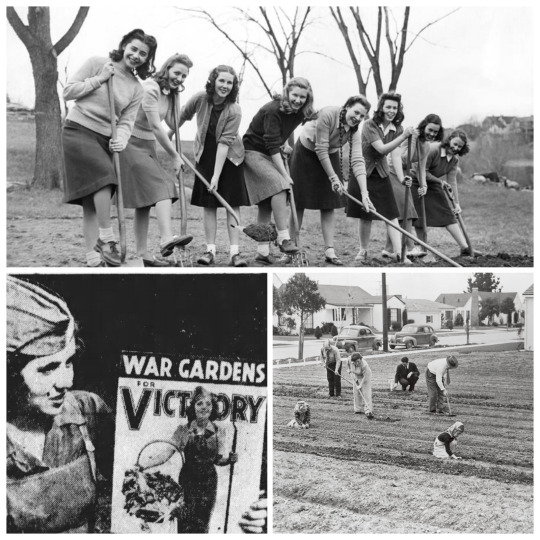

• Victory Gardens

Victory gardens, also called war gardens or food gardens for defense, were vegetable, fruit, and herb gardens planted at private residences and public parks in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and Germany during World War I and World War II. In wartime, governments encouraged people to plant victory gardens not only to supplement their rations but also to boost morale.

George Washington Carver is believed to have wrote an agricultural tract and promoted the idea of what he called a "Victory Garden". In March 1917, Charles Lathrop Pack organized the US National War Garden Commission and launched the war garden campaign. Food production had fallen dramatically during World War I, especially in Europe, where agricultural labor had been recruited into military service and remaining farms devastated by the conflict. Pack and others conceived the idea that the supply of food could be greatly increased without the use of land and manpower already engaged in agriculture, and without the significant use of transportation facilities needed for the war effort. The campaign promoted the cultivation of available private and public lands, resulting in over five million gardens in the US and foodstuff production exceeding $1.2 billion by the end of the war. Victory Gardens had also became popular in Canada in 1917. Under the Ministry of Agriculture's campaign, "A Vegetable Garden for Every Home", residents of cities, towns and villages utilized backyard spaces to plant vegetables for personal use and war effort. In the city of Toronto, women's organizations brought expert gardeners into the schools to get school children and their families interested in gardening. In addition to gardening, homeowners were encouraged to keep hens in their yards for the purpose of collecting eggs. The result was a large production of potatoes, beets, cabbage, and other useful vegetables.

During the second world war, rationing and the idea of home gardens to boost morale became once again popular. In Britain, "digging for victory" used much land such as waste ground, railway edges, ornamental gardens and lawns, while sports fields and golf courses were requisitioned for farming or vegetable growing. Sometimes a sports field was left as it was but used for sheep-grazing instead of being mown (for example see Lawrence Sheriff School § Effects of the Second World War). By 1943, the number of allotments had roughly doubled to 1,400,000, including rural, urban and suburban plots. During World War II, sections of lawn were publicly plowed for plots in Hyde Park, London to promote the movement, while allotments growing onions in the shadow of the Albert Memorial also pointed to everybody, high and low, chipping in to the national struggle. Australia launched a Dig for Victory campaign in 1942 as rationing and a shortage of agricultural workers began to affect food supplies. The situation began to ease in 1943; however, home gardens continued throughout the war.

Amid regular rationing of food in Britain, the United States Department of Agriculture encouraged the planting of victory gardens during the course of World War II. Around one third of the vegetables produced by the United States came from victory gardens. It was emphasized to American homefront urbanites and suburbanites that the produce from their gardens would help to lower the price of vegetables needed by the US War Department to feed the troops, thus saving money that could be spent elsewhere on the military: "Our food is fighting", one US poster read. By May 1943, there were 18 million victory gardens in the United States – 12 million in cities and 6 million on farms. Eleanor Roosevelt planted a Victory Garden on the White House lawn in 1943. The Roosevelts were not the first presidency to institute a garden in the White House. Woodrow Wilson grazed sheep on the south lawn during World War I to avoid mowing the lawn. Eleanor Roosevelt's garden instead served as a political message of the patriotic duty to garden, even though Eleanor did not tend to her own garden. While Victory Gardens were portrayed as a patriotic duty, 54% of Americans polled said they grew gardens for economic reasons while only 20% mentioned patriotism.

Although at first the Department of Agriculture objected to Eleanor Roosevelt's institution of a victory garden on the White House grounds, fearing that such a movement would hurt the food industry, basic information about gardening appeared in public services booklets distributed by the Department of Agriculture, as well as by agribusiness corporations. The Victory Garden movement also attempted to unite the Home-front. Local communities would have festivals and competitions to showcase the produce each person grew in their own gardens. While the garden movement united some local communities, the garden movement separated minorities like African Americans. At harvest shows, separate prizes were awarded to "colored people", in similar categories, a long-held tradition in Delaware and the deeper South, as well as in Baltimore.

In 1946, with the war over, many British residents did not plant victory gardens, in expectation of greater availability of food. However, shortages remained in the United Kingdom, and rationing remained in place for at least some food items until 1954. Since the turn of the 21st century, interest in victory gardens has grown. A campaign promoting such gardens has sprung up in the form of new victory gardens in public spaces, victory garden websites and blogs, as well as petitions to renew a national campaign for the victory garden and to encourage the re-establishment of a victory garden on the White House lawn. In March 2009, First Lady Michelle Obama planted an 1,100-square-foot (100 m2) "Kitchen Garden" on the White House lawn, the first since Eleanor Roosevelt's, to raise awareness about healthy food. Historical documentary and reality television series such as The 1940s House, Wartime Farm and the second season of Coal House place modern families in a recreated wartime settings, including digging victory gardens. The 1975 sitcom The Good Life portrays the efforts of Tom and Barbara Good to become self-sufficient in their suburban home, including turning over most of their garden to vegetable production and a chicken coop.

#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#wwii#history#home front#british history#ww2#first world war#garden#gardening#victory garden

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Junio Valerio Borghese

Junio Valerio Scipione Ghezzo Marcantonio Maria Borghese, nicknamed The Black Prince, was an Italian Navy commander during the regime of Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party and a prominent hard-line Fascist politician in post-war Italy.

Junio Valerio Borghese was born in Artena, Province of Rome, Kingdom of Italy on June 6th, 1906. He was born into a prominent noble family of Sienese origin, the House of Borghese, of which Pope Paul V was a notable member. His father, Livio Borghese, was the 11th Prince of Sulmona and younger brother to the more famous Scipione Borghese. Borghese was the second son of the prince and, as such, had the title of Patrician of Rome, Naples and Venice and the style of Don Junio Valerio Borghese. However, the press and the English-language historiography routinely used the courtesy style Prince Junio Valerio Borghese. Borghese was first educated in London, England, and, from 1923, he attended the Royal Italian Navy Academy (Accademia Navale) in Livorno. In 1929, the naval career of Borghese began. He married in Florence, in September 1931, the Russian countess Darya Vasilyevna Olsufeeva (Moscow, 1909 - Rome, 1963), sister of Alexandra "Assia" Vasilyevna Olsufeeva. They had four children. By 1933, he was a submarine commander. Borghese took part in the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. During the Italian intervention in the Spanish Civil War, he was in command of the submarine Iride, where he allegedly lost two seamen after his unit was depth-charged by the British destroyer HMS Havock.

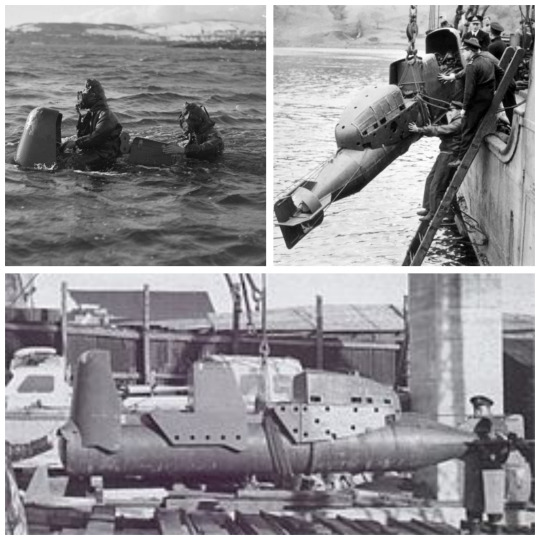

At the start of the Second World War, Borghese took command of submarine Vettor Pisani, and in August 1940 was in command of submarine Sciré, which was modified to carry the new secret Italian weapon, the human torpedo. Known as "slow speed torpedoes" (siluri a lenta corsa, or SLC), and nicknamed "pigs" (maiali) for their poor maneuverability, these were small underwater assault vehicles with a crew of two. These were part of the 1ª Flottiglia Mezzi d'Assalto (MAS), the "First Assault Vehicle Flotilla" (later called Decima Flottiglia MAS), an elite naval sabotage unit of the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina Italiana). As commander of Sciré Borghese took part in several raids using SLC. The first of these, in September and October 1940, were directed at Gibraltar. The September raid was abandoned when the harbour was found to be empty. In the October raid Borghese took Sciré deep into Gibraltar Bay, making a difficult submerged passage in order to release the SLC as close to target as possible. For this he received the Medaglia d'Oro al Valor Militare (MOVM), despite the mission's overall lack of success.

In May 1941 a further attempt ended in failure, but on September 20th, 1941 a successful mission damaged three merchant ships in the harbour. After this last attack he was promoted to Capitano di Fregata, and named commander of the Decima MAS' sub-surface unit. On December 18th, 1941, he reached Alexandria in Sciré and launched the daring raid by three SLCs that heavily damaged the two Royal Navy battleships HMS Valiant and HMS Queen Elizabeth and two other ships in the harbour. The six Italian Navy crew that attacked Alexandria harbour all received the Medaglia d'Oro al Valor Militare, and Borghese was named Cavaliere dell'Ordine Militare di Savoia. In May 1943, Borghese took command of the Decima Flottiglia MAS ("10th Assault Vehicle Flotilla"), or Xª MAS with Roman numerals, which continued active service in the Mediterranean and pioneered new techniques of commando assault warfare. The roman numeral was in memory of Caesar's famous Decima Legio.

After Italy's surrender to the Allies on September 8th, 1943, the Xª MAS was disbanded. While some of its sailors joined the Allies, Borghese chose to continue fighting with the Italian Social Republic (RSI) alongside the German Armed Forces (Wehrmacht). On September 12th, 1943, he signed a treaty of alliance with Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine. Many of his colleagues volunteered to serve with him, and the Decima Flottiglia was revived, headquartered in Caserma del Muggiano, La Spezia. By the end of the war, it had over 18,000 members, and Borghese conceived it as a purely military unit. The X Flottiglia gained a reputation for never firing a shot at any Italian military units fighting with the Allied forces. In April 1945 when the US command discovered that the British had granted permission to Marshal Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia, and his Communist troops, to occupy northeastern Italy from Venice to the east, Borghese moved the bulk of the X Flottiglia from the Ligurian and Piedmontese area to the Veneto. The X Flottiglia built a line of defense on the Tagliamento river where they resisted until the arrival of the Allied troops. In this action the X Flottiglia lost over eighty percent of the fighting sailors dispatched to the front against Tito's troops, and the Italian Communist Partisans allied with Tito. At the end of the war, Borghese was rescued by Office of Strategic Services officer James Angleton, who dressed him in an American uniform and drove him from Milan to Rome for interrogation by the Allies. Borghese was then tried and convicted of collaboration with the Nazi invaders, but not of war crimes, by the Italian Court. He was "sentenced to 12 years imprisonment, discounted to 3 years, due to his glorious expeditions during the war, his defence of north east borders against Tito's IX Corps and his defence of Genoa harbour". He was released from jail after four years' imprisonment by the Supreme Court of Cassation in 1949.

With his record as a war hero and his support of Fascism, he became a figurehead for pro-fascist, anti-communist groups in the immediate post-war period, acquiring the nickname Black Prince. Borghese wrote a supportive introduction, affirming his political ideology of an idealistic neo-fascist new aristocracy meritocratically based purely on character, to far right revolutionary-conservative theorist Julius Evola's book Men Among the Ruins. He later wrote a memoir of his wartime exploits, published as Sea Devils in 1954. He was associated with the Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI), the neo-Fascist party formed in the post-World War II period by former supporters of the dictator Benito Mussolini. Following a last minute aborted coup d'état plot which fizzled out in the night of December 8th, 1970 (the Feast of the Immaculate Conception), referred to as the Golpe Borghese, he was forced to cross the border to avoid arrest and interrogation. In 1984, ten years after Borghese's death, the Supreme Court of Cassation ruled that no coup d'état attempt had happened. Nevertheless, the attempt is well known in Italy and film director Mario Monicelli made a biting satire of it called Vogliamo i colonnelli (1972) (We want the Colonels, as the Fascist Greek colonels were pulling the strings behind the scenes).

Latterly regarded as a political outcast and shunned by his ancestrally blue blood social connections for his "heretical" political extremism and disregard for the external norms of modern aristocratic etiquette and behavior, Junio Valerio Borghese died under mysterious circumstances in Cádiz, Spain, on August 26th, 1974, aged 68. The death certificate records the cause of death as "acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis"; however, since the Prince was visited by a physician who found him in good shape just a few days before, it has been suggested that the circumstances of his death, characterized by a sudden onset of abdominal pain immediately after supper, could be compatible with arsenic poisoning. He is buried in the Borghese family chapel in the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome.

#world war 2#second world war#world war ii#wwii#military history#history#naval history#italian history#biography#submarines#italy in ww2#italian navy

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

• 369th Croatian Infantry Regiment

The 369th (Croatian) Reinforced Infantry Regiment was a regiment of the German Army raised to fight on the Eastern Front during World War II. The regiment was formed in July 1941 from Croatian volunteers from the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) . The troops swore a joint oath of allegiance to the Führer, the Poglavnik, the German Reich and the NDH.

On April 10th, 1941, the Independent State of Croatia (NDH, Croatian: Nezavisna Država Hrvatska) was created as a puppet state aligned to the occupying Germans. The Ustaše fascist government of the NDH asked Germany for military assistance as they feared Italian territorial ambitions after ceding much of the coastal area of Dalmatia to Italy in treaties signed on May 18th, 1941. By June 25th, 1941, Poglavnik Ante Pavelić, the leader of the NDH, had sent an envoy to Berlin to offer volunteers to serve on the Eastern Front. By July 2nd, Hitler accepted the offer, and military units were formed under the supervision of two German army officers. The NDH viewed this as a means of strengthening its ties with Germany, potentially an ally in resisting further territorial losses to Italy. Although the NDH considered the unit to be a part of the Croatian Home Guard and the NDH authorities retained responsibility for providing replacements, the regiment's members swore an oath to Adolf Hitler. Whilst not officially part of the Wehrmacht, the regiment was under German military jurisdiction and direct German command throughout its existence, serving as part of the 100th Jäger Division.

All soldiers wore Wehrmacht uniforms with a Croatian checkerboard patch incorporating the word Hrvatska (Croatia) on the upper right sleeve and right side of the helmet. Initially, two battalions were raised and formed into a regiment at Varaždin. This was followed by the raising of a third battalion at Sarajevo. Only Croats, Ukrainians or White Russians were accepted as volunteers, and about one third of those accepted were Bosnian Muslims, who were mostly admitted into the 1st battalion. As the volunteers were promised high salaries and financial assistance to their families, the enrollment figures were relatively good. A training battalion was formed for the regiment in Stockerau, Austria. The regiment was then transported to Döllersheim, Austria for training. With an effective strength of 5,000, the regiment consisted of three infantry battalions, a machine-gun company, an anti-tank company, three field artillery batteries, headquarters staff and a supply company. In August 1941, the regiment was transported to Romania. From there, it spent several weeks marching on foot to the front line. On October 10th, the regiment linked up on the line of the Dnieper River with the 100th Jäger Division, which was then part of Army Group South.

To accustom the regiment to the conditions and divisional procedures and further progress their training, the regiment's units were initially divided up among other regiments of the division immediately after their arrival on the front line near Kharkov. The divisional diary recorded that the main goal for units of the regiment during this period was to improve discipline across various areas. To improve poor discipline, in September 1941, Colonel Ivan Markulj sent 43 officers and NCOs as well as 144 soldiers back to the NDH due to illness and/or for disciplinary reasons. After the Red Army counterattacked and re-took Rostov in November 1941, the 100th Jäger Division marched south to the front line on the Mius River on November 22nd. Temperatures dropped as low as -18C, and the regiment had no winter clothing. The regiment's units, still divided among the other regiments of the division, dug in alongside the Slovak Mobile Brigade and SS-Division Wiking. In mid-January 1942, the 100th Light Infantry Division was deployed to the Stalino area to assist in fighting off a Soviet cavalry corps that had broken through the front line. Through some heavy fighting along the line of the Samara River, the division held on through the winter. Starting in early 1942, soldiers were able to send messages back to the Independent State of Croatia. Troops wrote letters for family members and friends on any paper they could find, such as cigarette papers or pages torn from notebooks. Generalleutnant Werner Sanne, the 100th Jäger Division's commander, commended the regiment's successes over the winter, especially the actions of Lieutenant Colonel Marko Mesić's artillery battalion. From mid-May 1942, the regiment was reunited under Colonel Markulj, after which the 100th Jäger Division joined in the final phases of the pincer attack on the Red Army bridgehead at Kharkov. In June, the division supported the 1st Panzer Army's drive along the Don River, through Voronezh to Kalach where the regiment incurred heavy casualties trying to cross the river in the face of serious resistance. After the Second Battle of Kharkov, Colonel Markulj, Lieutenant Eduard Bakarec and six other regiment officers were awarded the Iron Cross First Class.

After participating in mopping-up operations in along the Don, the division rested briefly in September, and the regiment was re-organised after receiving some reinforcements. Markulj was transferred back to Croatia and was temporarily replaced by Colonel Marko Mesić on July 7th, 1942. At 'Proljet Kultura,' the regiment suffered 53 dead and 186 wounded in desperate hand-to-hand combat during the German attack on July 27th and subsequent overwhelming Soviet counterattack on July 28th. The worst recorded casualties before Stalingrad were 171 dead suffered in combat in various villages along the Samara River. In September 1942, during a visit to the 6th Army headquarters, Pavelić decorated and promoted some soldiers of the regiment. Two days later, the 100th Light Infantry Division was committed to the Battle of Stalingrad. From that date, the number of legionnaires was fast reducing to a reported total of 1,403 altogether by 21 October 1942. New fresh forces from Croatia were not added except for returns of sick and wounded and a few officers and staff. A total of 22 (15%) officers were killed, 38 (26%) wounded, and 66 (45%) returned to Croatia from the original 147 Legion officers in total before fall. Only 20 officers, including Mesic, remained in Stalingrad.

The 100th Jäger Division, including the 369th Croatian Reinforced Infantry Regiment, was involved in the heavy fighting for the "Red October" factory and for Mamayev Hill during the Battle of Stalingrad. By November 1942, the fighting in their sector had become a locked stalemate with little progress. By December 1942, the regiment had seen such intense combat that it was at 1/3 strength. Despite the harsh conditions, the German high command credited the regiment with maintaining 'proper and military bearing'. Several distinctions and citations are noted in war diaries and official military documents. There are several citations for bravery, valour, and leadership under fire for men of all ranks, including Lieutenant Rudolf Baričević. In addition, the regimental doctors received distinctions for their actions and success in saving lives. One notable citation is that of Captain Madraš, who was wounded and was to be flown out of Stalingrad, but refused and instead stayed and fought with his men. There were also acts of insubordination, dereliction of duty, and cowardly behaviour cited in reports. This was common for the demoralized and surrounded German and German-allied troops at Stalingrad, as the conditions were extremely harsh on the soldiers. Major Tomislav Brajkovic is noted to have desperately attempted to keep morale and discipline high. However, due to major disagreements with other officers, including his commanding officer, he was transferred out of the regiment. By January, the regiment's section of the front line had reduced to 200 m held by some 90 remaining troops, all suffering from extreme cold, hunger, fatigue and lack of ammunition. Colonel Viktor Pavicic reportedly left a resignation letter and disappeared from the theatre for good. During its last days at Stalingrad, the Legion desperately retrained about 700 inexperienced artillery and support soldiers to infantry combat duty. The last official report from January 21st, 1943 counted 443 infantry and 444 artillery soldiers in Stalingrad. Just before the surrender of the 6th Army at the end of January, about 1,000 wounded were flown out, and of the remaining men in the regiment, nearly 900 became prisoners of war. Among the last Wehrmacht soldiers to leave Stalingrad by air were a group of 18 wounded and sick Croat legionnaires. The evacuation also saved the regiment's war diary and other documents. Elements of the regiment fought as long as they could but ultimately surrendered to the Soviet General Vasiljev on January 29th, 1943. In the three months between 21 October 1942 and 21 January 1943, they had lost 540 of 983 troops fighting for the Red October factory.

The Legion assembled at Beketovka on river Volga where they were joined by some 80,000 mainly German as well as Italian, Romanian and Hungarian POWs. They were sent on a forced march to Moscow, where they were joined by Croatian legionnaires from the Light Transport Brigade who had been attached to Italian forces on the Eastern Front. From there, they were sent to work camps in Siberia. Many died on the march due to starvation, hypothermia or disease. More than 1,000 legionnaires were evacuated from the Soviet Union and later Stalingrad by various means and for various reasons. They were awarded the Croatian Legion 1941 Linden Leaf for their service and formed the core of a new unit, the 369th (Croatian) Infantry Division. In late October 1944, the Yugoslav Legion numbering about 3,000 operated as part of the Red Army around Čačak during the Belgrade Offensive. This unit was formed in early 1944 partly from former members of the 369th (Croatian) Reinforced Infantry Regiment. It was commanded by the former Ustaše Lieutenant Colonel Marko Mesić. Col. Mesić was given command by the Soviets of this newly formed 1st Yugoslav Volunteer Brigade, assembled from Yugoslav prisoners of war and volunteers living in Russia at the time. It is quite likely that most former Croatian soldiers of the 369. Regiment chose Communist Partisan service to avoid almost certain death in Soviet prisoner-of-war camps. During the first few months in captivity, Legionnaire numbers were reduced from some 700 to around 400 odd survivors or a 40% loss of life in under twelve months. The new Yugoslav partisan brigade, now wearing old Royal Yugoslav Army uniforms, was commanded by experienced former 369th Regiment Croat Legion officers. They were transported to Yugoslavia in late 1944 under direct orders from Tito, where they were sacrificed in combat against superior German forces, suffering very high casualties. The few remaining survivors were suspected, and most were later convicted of being Soviet infiltrators by the partisans as well as Croat NDH authorities.

This post was requested by @historyofcroatia go view their blog for extensive history of the Croatian people and country.

#second world war#world war ii#world war 2#wwii#military history#history#german history#Croatian history#croatian#stalingrad#yugoslavia history#untold history

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

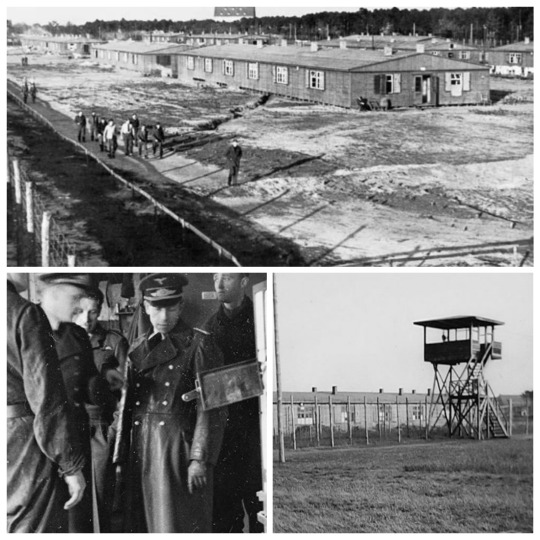

• Stalag Luft III POW Camp

Stalag Luft III (German: Stammlager Luft III; literally "Main Camp, Air, III"; SL III) was a Luftwaffe-run prisoner-of-war (POW) camp during the Second World War, which held captured Western Allied air force personnel.

The German military followed a practice whereby each branch of the military was responsible for the POWs of equivalent branches. Hence the Luftwaffe was normally responsible for any Allied aircrew taken prisoner. This included captured naval aviators, such as members of the British Fleet Air Arm. In a few cases, other non-air force personnel were also held at Stalag Luft III. The camp was established in March 1942 near the town of Sagan, in Lower Silesia in then Germany (now Żagań, Poland), 160 kilometres (100 miles) south-east of Berlin. The site was selected because its sandy soil made it difficult for POWs to escape by tunnelling. The first compound (East Compound) of the camp was completed and opened on March 21st, 1942. The first POWs, or kriegies, as they called themselves (from Kriegsgefangene, German for "Prisoner of War"), to be housed at Stalag Luft III were British and other Commonwealth officers, arriving in April 1942. The Centre Compound was opened on April 11th, 1942 and originally held British and other Commonwealth NCOs; by the end of 1942, however, they were replaced by USAAF personnel. The North Compound for British airmen, (where the "Great Escape" later occurred) opened on March 29th, 1943. A South Compound for Americans was opened in September 1943 and USAAF prisoners began arriving at the camp in significant numbers the following month and the West Compound was opened in July 1944 for US officers. Each compound consisted of fifteen single-story huts. Each 3.0-by-3.7-metre (10-by-12-foot) bunkroom slept fifteen men in five triple-deck bunks. Eventually the camp grew to approximately 24 hectares (60 acres) in size and housed about 2,500 Royal Air Force officers, about 7,500 US Army Air Forces, and about 900 officers from other Allied air forces, for a total of 10,949 inmates, including some support officers.

The prison camp had a number of design features that made escape extremely difficult. The digging of escape tunnels, in particular, was made difficult by several factors: the barracks housing the prisoners were raised approximately 60 centimetres (24 in) off the ground to make it easier for guards to detect tunnelling; the camp had been constructed on land that had a very sandy subsoil. The loose, collapsible sand meant the structural integrity of any tunnel would be very poor. A third defence against tunnelling was the placement of seismograph microphones around the perimeter of the camp, which were expected to detect any sounds of digging. A substantial library with schooling facilities was available, where many POWs earned degrees such as languages, engineering or law. The exams were supplied by the Red Cross and supervised by academics such as a Master of King's College who was a POW in Luft III. The prisoners also built a theatre and put on high-quality bi-weekly performances featuring all the current West End shows. POWs operated a system whereby newcomers to the camp were vetted, to prevent German agents from infiltrating their ranks. Any POW who could not be vouched for by two POWs who knew the prisoner by sight was severely interrogated and afterwards escorted continually by other prisoners, until such time as he was deemed to be a genuine Allied POW. Several infiltrators were discovered by this method and none is known to have escaped detection in Luft III.

The German guards were referred to by POWs as "goons" and, unaware of the Allied connotation, willingly accepted the nickname after being told it stood for "German Officer Or Non-Com". German guards were followed everywhere they went by prisoners, who used an elaborate system of signals to warn others of their location. The guards' movements were then carefully recorded in a logbook kept by a rota of officers. Unable to stop what the prisoners called the "Duty Pilot" system, the Germans allowed it to continue and on one occasion the book was used by Kommandant von Lindeiner to bring charges against two guards who had slunk away from duty several hours early. The camp's 800 Luftwaffe guards were either too old for combat duty or young men convalescing after long tours of duty or from wounds. Because the guards were Luftwaffe personnel, the prisoners were accorded far better treatment than that granted to other POWs in Germany. Food was an ongoing matter of concern for the POWs. Luft III issued "Non-working" German civilian rations which allowed 1,928 kcal (8,070 kJ) per day, with the balance made up from American, Canadian, and British Red Cross parcels and items sent to the POWs by their families. As was customary at most camps, Red Cross and individual parcels were pooled and distributed to the men equally. Every three months, weak beer was made available in the canteen for sale. As NCOs did not receive any "pay" it was the usual practice in camps for the officers to provide one-third for their use but at Luft III all lagergeld was pooled for communal purchases. Stalag Luft III had the best-organised recreational program of any POW camp in Germany. Each compound had athletic fields and volleyball courts. The prisoners participated in basketball, softball, boxing, touch football, volleyball, table tennis and fencing, with leagues organised for most. As described by J. Frank Diggs, many amenities were made possible by Swedish lawyer Henry Söderberg, who was the YMCA representative to the area, and frequently brought to its camps not only sports equipment, and religious items supporting the work of chaplains.

The first escape occurred in October 1943 in the East Compound. Conjuring up a modern Trojan Horse, kriegies (prisoners) constructed a gymnastic vaulting horse largely from plywood from Red Cross parcels. The horse was designed to conceal men, tools and containers of soil. Each day the horse was carried out to the same spot near the perimeter fence and while prisoners conducted gymnastic exercises above, a tunnel was dug. At the end of each working day, a wooden board was placed over the tunnel entrance and covered with surface soil. The gymnastics disguised the real purpose of the vaulting horse and kept the sound of the digging from being detected by the microphones. For three months three prisoners, Lieutenant Michael Codner, Flight Lieutenant Eric Williams and Flight Lieutenant Oliver Philpot, in shifts of one or two diggers at a time, dug over 30 m (100 ft) of tunnel, using bowls as shovels and metal rods to poke through the surface of the ground to create air holes. No shoring was used except near the entrance. On the evening of October 19th, 1943, Codner, Williams and Philpot made their escape. Williams and Codner were able to reach the port of Stettin where they stowed away on a Danish ship and eventually returned to Britain. Accounts of this escape were recorded in the book Goon in the Block (later retitled The Wooden Horse) by Williams, the book Stolen Journey by Philpot and the 1950 film The Wooden Horse.

In March 1943, Royal Air Force Squadron Leader Roger Bushell conceived a plan for a mass escape from the North Compound, which took place on the night of 24/25th, March 1944. He was being held with the other British and Commonwealth airmen and he was in command of the Escape Committee that managed all escape opportunities from the north compound. Falling back on his legal background to represent his scheme, Bushell called a meeting of the Escape Committee to advocate for his plan. Group captain Herbert Massey, as senior British officer, authorised the escape attempt which would have good chance of success; in fact, the simultaneous digging of three tunnels would become an advantage if any one of them was discovered, because the guards would scarcely imagine that another two were well underway. The most radical aspect of the plan was not the scale of the construction, but the number of men intended to pass through the tunnels. While previous attempts had involved up to 20 men, in this case Bushell was proposing to get over 200 out, all wearing civilian clothes and some with forged papers and escape equipment. As this escape attempt was unprecedented in size, it would require unparalleled organisation; as the mastermind of the Great Escape, Roger Bushell inherited the codename of "Big X". More than 600 prisoners were involved in the construction of the tunnels. Three tunnels, Tom, Dick, and Harry were dug for the escape. The operation was so secretive that everyone was to refer to each tunnel by its name. Bushell took this so seriously that he threatened to court-martial anyone who even uttered the word "tunnel". Tom began in a darkened corner next to a stove chimney in hut 123 and extended west into the forest. It was found by the Germans and dynamited. Dick's entrance was hidden in a drain sump in the washroom of hut 122 and had the most secure trap door. It was to go in the same direction as Tom and the prisoners decided that the hut would not be a suspected tunnel site as it was further from the wire than the others. Dick was abandoned for escape purposes because the area where it would have surfaced was cleared for camp expansion. Dick was used to store soil and supplies and as a workshop. Harry, which began in hut 104, went under the Vorlager (which contained the German administration area), sick hut and the isolation cells to emerge at the woods on the northern edge of the camp. The entrance to "Harry" was hidden under a stove. Ultimately used for the escape, it was discovered as the escape was in progress with only 76 of the planned 220 prisoners free. The Germans filled it with sewage and sand and sealed it with cement.