Text

Elements in your book by order of importance

The order of importance of elements in a book can vary depending on the genre, theme, and narrative structure. However, here are some common elements that are often considered significant:

- Plot: The sequence of events that drive the story forward and create tension, conflict, and resolution.

- Characters: The individuals who inhabit the story and contribute to its development and emotional engagement.

- Theme: The central idea or message that the book explores and conveys to the reader.

- Setting: The time, place, and environment in which the story takes place, which can enhance mood, atmosphere, and context.

- Writing style: The author's unique voice and the way the story is narrated, which can greatly impact the reader's experience.

- Conflict: The challenges, obstacles, or opposition that the characters face, driving the narrative and character development.

- Dialogue: The conversations and interactions between characters, providing insights into their personalities, relationships, and plot progression.

- Pacing: The rhythm and speed at which events unfold, affecting the book's flow and reader engagement.

- Emotional resonance: The ability of the story to evoke strong emotions and create a connection between the reader and the characters.

- Tone: The overall mood and atmosphere of the book, which can range from light-hearted and humorous to dark and somber.

- Point of view: The perspective from which the story is told, influencing the reader's understanding and connection to the characters.

- Symbolism: The use of symbols or metaphors to convey deeper meanings or layers of understanding.

- Subplots: Secondary storylines that add depth, complexity, and variety to the main plot.

- Imagery: Vivid and descriptive language that appeals to the reader's senses and creates vivid mental images.

- Structure: The organization and arrangement of the story, including chapters, sections, and narrative devices.

- Originality: The unique and innovative aspects of the book that set it apart and make it memorable.

987 notes

·

View notes

Text

btw (i say like i’ve posted here in like… a year), if i ever post anything i write for jjk and/or kny, assume they take place in the same universe, regardless of if it’s relevant to that specific fic

#mine#text#someone: why do you describe this kny oc’s eyes so much#me: it’s a surprise tool that will help us later#jjk#kny

1 note

·

View note

Text

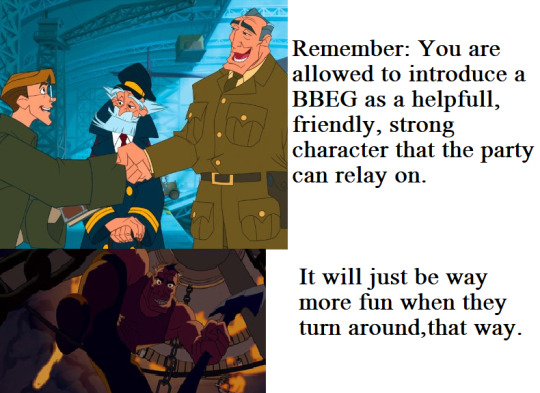

How to Develop a Memorable Antagonist

Antagonists are one of the most important characters in your book. Without an antagonist, writers wouldn’t have a story to write in the first place. They bring the action, drama, trauma and many other factors that are often the reason for a book’s success. However, their pivotal role in the book is often why antagonists can come across as poorly-written one-dimensional characters.

From stereotypical backstories to a lack of humanisation, authors often make simple mistakes that can result in a cliche or boring antagonist. Are you struggling to create a compelling antagonist for your WIP? Here are some tips to help you get started.

Give Your Antagonist A Clear Motive

People don’t just wake up one day and decide they want to fundamentally alter society and possibly end the world. Or, maybe they do, but their idealogy starts somewhere. Voldemort wanted to change the wizarding world because he loathed muggles due to his parents, Hannibal’s tragic past triggered his cannibalistic tendencies.

Every antagonist has a reason for their crimes, and it's important to understand your antagonist’s motives and goals in order to create a compelling villain. Start with your antagonist’s backstory.

Did they have a tragic childhood? Did they desperately want to achieve a certain goal but failed and were driven insane? Are they following someone? Are they being manipulated? There is an endless list of possible reasons you can choose from in order to create a compelling motive for your antagonist.

Make Your Antagonist Multi-Dimensional

Once you have established their initial reasoning it’s time to go into more detail. I would start by taking their dynamic with the other characters into consideration. Why do they despise the protagonist? Do they want to simply remove the obstacles in their way or do they have a personal vendetta?

It’s also important to consider the other characters. Is there a mentor figure in your book who the antagonist has a personal vendetta against? What about their allies and henchmen? How did they meet them? Did the antagonist start off alone or have they worked with the same group of people since the start?

Your readers don’t necessarily need to know every single detail of your antagonist’s past, but having a clear understanding of their motives and dynamics can help you create a clear image of the antagonist. For example, they could be particularly spiteful towards the protagonist’s best friend because she is the daughter of the antagonist’s ex-ally. This could make for an easy subplot or come in handy if you need to distract the antagonist in a fight scene.

Make Your Readers Empathise With Them

When developing a motive authors should always look for a way to make their readers empathise with the antagonist. Show us why we should feel sorry for them, tell us they could have had a promising future if it weren’t for an unjust moment in their lives. When you make your readers feel conflicted about your antagonist they become more than just a character on the page.

Your readers begin to question whether their tragic past justifies their actions, some might root for them, others might dislike them more and regard them as apathetic. However, the goal is to make your readers view your antagonist as more than just the person causing issues for your protagonist.

Give Them Strengths And Weaknesses

Everyone hates a Mary Sue protagonist, but the same can be said for an antagonist. Think of it this way—if your antagonist is an all-powerful flawless villain who could destroy the world if they wanted to, then why haven’t they already won? Why do they have to fight the protagonist?

The good vs bad, protagonist vs antagonist dynamic only entices readers if they can’t tell who is going to come on top at the end of it all. This is why it’s essential to give your antagonist appropriate strengths and weaknesses.

Here’s an example of an antagonist with appropriate strengths and weaknesses: a main antagonist is an all-powerful witch who wants to destroy the protagonist’s home country but she lost most of her power in a fight against the mentor and can’t gain them back without a special artefact.

This example shows your readers how big of a threat the antagonist is while also providing her with appropriate strengths and shortcomings. This can look a little different depending on the genre you write for. Maybe the antagonist in a romcom wants to get the love interest married off to a side character and has the leverage to do so but the main character is introduced to the love interest’s family to try and sway the antagonist’s plans.

You don’t need to create a comprehensive list of all of your antagonist’s strengths and weaknesses, but it’s important to have a proper understanding of what puts them in a position to easily combat your protagonist and what stops them from outright winning.

Showcase Their (Negative) Impact On The Story

An antagonist can only be labelled as such if they actively do things to hinder or harm the protagonist. Simply saying your antagonist is a bad person isn’t enough, you need to show your readers this too.

When you start reading Harry Potter it is made clear that Voldemort was an all-powerful wizard who severely damaged the wizarding world during the first war, however, his bad deeds aren’t only reserved for the past. He was also just as evil in the present and was out to harm Harry from the first book itself.

From small confrontations with the protagonists to entire fights, it’s important to create a range of situations and chapters that can showcase your antagonist’s ‘true colours’.

Keep Their Personality Consistent

Just like every other character, it is important to ensure you have a consistent personality type for your antagonist. An antagonist regularly spotted in a suit known for their professional and calculative plans wouldn’t casually joke around with the protagonists during a showdown. The way they contradict the protagonist should also be reflective of their personality.

You should also take their personal history into consideration and how that could impact their dynamics with certain characters. For example, a character like Tom Riddle who despised both of his parents would likely be spiteful whenever they see the protagonist with their mentor figure and could even target the mentor out of spite.

The only time an antagonist’s personality should change is during a pivotal point in the book’s plot. Maybe the put-together antagonist shows off their frustrated side when the protagonist outwits them, maybe they let out maniacal laughter when the protagonist asks them about their motives.

It’s important to treat your antagonists like humans and consider how a person with that personality would realistically react to the situations they are in.

Avoid Creating A Stereotypical Antagonist

Nobody likes an overdone cliche. When writing your antagonist try to avoid creating stereotypical villains. Here are a few examples of stereotypical antagonists and how to avoid them:

The Evil Mastermind: Instead of making the antagonist an all-powerful villain with no weaknesses, give them flaws and limitations that can be exploited by the protagonist. Make the antagonist's motives more complex than just wanting to take over the world, and consider giving them a personal connection to the protagonist or a sympathetic backstory.

The Brainwashed Henchman: Rather than having the antagonist control their minions through brainwashing or mind control, make the henchman have agency and free will. Consider making the henchman conflicted about their role, or have them question the antagonist's motives and methods.

The Vengeful Ex-Lover: Instead of making the antagonist a scorned lover seeking revenge, consider giving them a different motivation for their actions. For example, the antagonist might be seeking revenge for a perceived betrayal, or they might be trying to protect someone they care about.

The Unfeeling Machine: Rather than making the antagonist a cold, calculating machine with no emotions, consider giving them a personal stake in the conflict. The antagonist might be acting out of fear or desperation, or they might be struggling with moral dilemmas related to their actions.

The Crazy Cult Leader: Instead of making the antagonist a stereotypical cult leader with a group of brainwashed followers, consider giving them a more nuanced personality. The antagonist might genuinely believe in their cause and be able to convince others to follow them, or they might be struggling with doubts and conflicts within their own ideology.

Avoid ‘One Man Armies’

Let’s be honest, one evil wizard cannot destroy your protagonist’s entire world by themselves. Just like protagonists have mentors, allies, coworkers, friends and sidekicks your antagonists need to have allies too. Voldemort didn’t conquer the entire wizarding world by himself right after graduating from Hogwarts, he instead built his troops and only fought Dumbledore once he was ready.

When worldbuilding for your novel it’s important to create some semblance of character development for background antagonists as well as the lead antagonists.

I hope this blog on how to develop a memorable antagonist will help you in your writing journey. Be sure to comment any tips of your own to help your fellow authors prosper, and follow my blog for new blog updates every Monday and Thursday.

Looking For More Writing Tips And Tricks?

Are you an author looking for writing tips and tricks to better your manuscript? Or do you want to learn about how to get a literary agent, get published and properly market your book? Consider checking out the rest of Haya’s book blog where I post writing and marketing tools for authors every Monday and Thursday

749 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to write romantic love

Writing romantic love is simultaneously one of the most joyful things you can do as a writer, and one of the most difficult. There’s a lot of emotion to cover - from the highs of a new relationship, to the struggles of a relationship on the rocks.

Like all of us, your characters will display love differently. Are they open and affectionate? Shy and nervous? Loud and blunt? To help you along the way, here’s some examples of descriptions you can use to show (not tell) your readers that your characters are in love.

Movement

Inching towards each other to touch

Shyly tucking stray hair behind the ear

Unconsciously parting or licking lips

Embracing with full bodies touching

Nervously shuffling feet

Running and reaching with open arms

Fiddling with hair or clothing

Crossing or uncrossing legs

Leaning forward to show attentiveness

A bounce in the step

Glancing flirtily over the shoulder

Facial expressions

Flirtatious winking

Smiling to themselves at nothing

Glancing up through lowered lashes

Unblinking eye contact

Grinning or beaming uncontrollably

A look of yearning

Lips slightly parted with desire

Dilated pupils

Glowing cheeks or flushed skin

Faraway, daydreaming look

Slight, secretive smile

Sounds

Deep sighs

Unconscious swallowing

Nervous coughing or throat clearing

Light chuckle with a silly grin

Grunts of appreciation or praise

An inner, audibly racing pulse

Thumping heart

Quick, short breaths

Low, whispered voices

Listening to love songs

Joyfully humming

Feelings and sensations

Nervous tingling

Butterflies in the stomach

Hot and flushed face

Hyper-sensitive skin

Acute awareness of personal proximity

Weak knees or legs turning to jelly

Shaky hands

Loss of speech or getting tongue-tied

Daydreaming and absentmindedness

Seeing the beauty in the world

Pulse racing

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

I just made the most needlessly complicated character profile template anyone's ever seen. It's perfect for when you want to infodump real hard about your OCs. I'll share it in a minute

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Pro Tip: The Way You End a Sentence Matters

Here is a quick and dirty writing tip that will strengthen your writing.

In English, the word at the end of a sentence carries more weight or emphasis than the rest of the sentence. You can use that to your advantage in modifying tone.

Consider:

In the end, what you said didn't matter.

It didn't matter what you said in the end.

In the end, it didn't matter what you said.

Do you pick up the subtle differences in meaning between these three sentences?

The first one feels a little angry, doesn't it? And the third one feels a little softer? There's a gulf of meaning between "what you said didn't matter" (it's not important!) and "it didn't matter what you said" (the end result would've never changed).

Let's try it again:

When her mother died, she couldn't even cry.

She couldn't even cry when her mother died.

That first example seems to kind of side with her, right? Whereas the second example seems to hold a little bit of judgment or accusation? The first phrase kind of seems to suggest that she was so sad she couldn't cry, whereas the second kind of seems to suggest that she's not sad and that's the problem.

The effect is super subtle and very hard to put into words, but you'll feel it when you're reading something. Changing up the order of your sentences to shift the focus can have a huge effect on tone even when the exact same words are used.

In linguistics, this is referred to as "end focus," and it's a nightmare for ESL students because it's so subtle and hard to explain. But a lot goes into it, and it's a tool worth keeping in your pocket if you're a creative writer or someone otherwise trying to create a specific effect with your words :)

33K notes

·

View notes

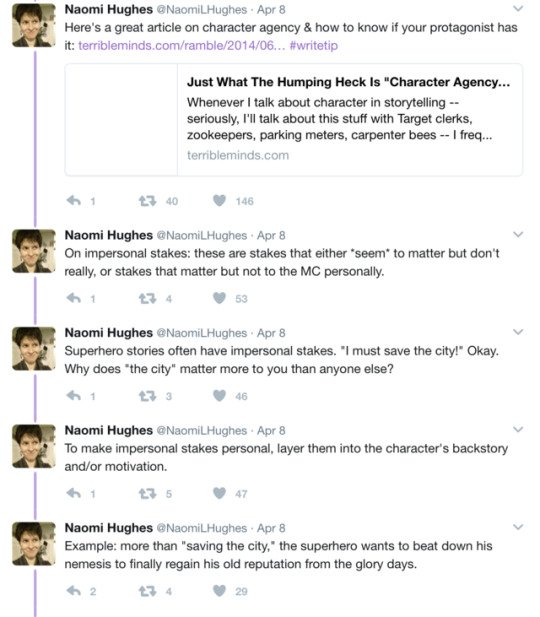

Photo

A great Twitter thread on character-driven stories, character arcs, and agency by Naomi Hughes

(The link she referenced is this article)

31K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm not kidding when I say worldbuilding is extremely easy and fun, you can make easily all sorts of new fantasy worlds on like half an hour, follow this guide:

take a rectangle, draw a line through the middle, that's your equator, draw another two lines south and north, those are your tropics, draw another two lines further north (you can see a real world map to guide yourself), those are your arctic/antarctic circles

Draw continents, any shape you want, it's better to combine large soft blobs (like Africa or South America) with coastlines full of peninsulas and islands (like Europe or South Asia). Draw some island chains in between where you feel it's appropiate. Some inland seas like the Mediterranean are good too.

Decide where you will place mountain ranges. In real life, they are where oceanic-continental plates (Andes) or continental-continental plates (Himalayas, Alps), collide. These are very important.

Place rivers, just the most important ones. The places where you place big river systems are gonna be big plains.

Now, the fun part. With your first step, you've already decided where arctic, temperate, and tropical climates are there. You can mark it as letters in your map. Mountain ranges, of course, are colder.

Here's the tricky part: vegetation: vegetation mostly follows precipitation, and precipitation is mostly decided by altitude and distance from the ocean. The interior of your continents should be dry with plains and deserts; the coasts should be rainy with forests and plains. But remember, if you have a mountain range, that's a rain shadow! Picture the wind coming from the ocean with rain, and it should get less rainy when it "clashes" with a mountain range, with the other side a desert.

Deserts are tricky to place, but as a quick cheat, you can place them in your tropic lines. They can even border oceans: see Australia and the Kalahari.

WHEN IN DOUBT, LOOK AT SIMILAR AREAS ON A REAL WORLD VEGETATION/CLIMATE MAP. THIS IS WHY DRAWING THE EQUATOR AND THE TROPICS IS SO IMPORTANT AND SHOULD BE YOUR FIRST STEP ALWAYS.

Now you already have a quick and dirty vegetation map, you're halfway there! Don't worry if there are some doubtful areas, real world geography can be weird.

Now for the REAL fun stuff (if you aren't having fun already, I sure am): making civilizations!

You have to decide center of origins for your domesticated crops and animals. Basically, every early civilization had its own "package" of staple crops and animals that are still used today.

With this, you can decide:

the primary civilizations of your world

roughly how different animals and vegetation are distributed, if you want an Earth-like world (for an quicker method, you can apply the biogeographical realms to your own continents as you wish)

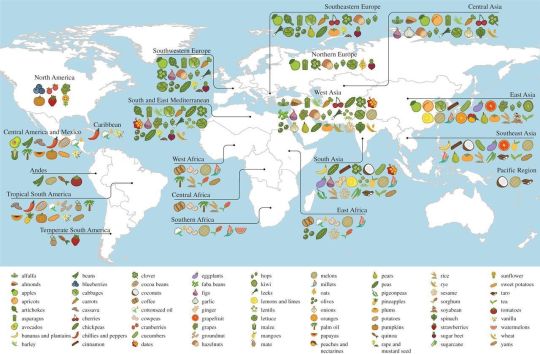

A quick cheat sheet of centers of origin, what they have, and where you can place them:

(this is just a quick thing, do read the article it's so much better)

Middle Eastern: wheat, barley, cows, sheep, goats. Place them in a dry area with lots of rivers (the Fertile Crescent!)

East Asia: rice, soybean, oranges, pigs, horses. Place it in a rainy temperate area bordering the tropics.

Mesoamerica: Corn, beans, pumpkin, chilli, tomato. Place it in a dry area near the tropics.

Andes: Potato, quinoa, llamas. Place it in a mountain range.

Tropical South America: manioc, peanuts, pineapple. In the tropics.

Tropical Asia: Rice, banana, sugar cane, beans. In the tropics, again.

or, just straight up use this fucking map, it's so much better:

You can mix and match the crops, animals, and such as you wish, and you should definitively read the wiki page on center of origins and see some other less known crops.

If you have non-human civilizations, of course they'll have different packages. Carnivore or subterranean civilizations might be very different. But at this point, your imagination should be flying already and I don't have to hold your hand here.

Now, you have a rough map of your world at the dawn of agriculture! Congratulations! Depending on the historical period you're setting your world, you can start to draw countries and civilizations. This is where it gets complicated again. I might have to make a part two... But just with this, you already have a new world to use as you wish.

I'll make a worked example later to show you how easy it is if you don't believe me.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

true!

listen, the potential of hamon was absolutely squandered in canon. like, stands are cool and all, but we were robbed of something truly amazing - i.e. the sheer POTENTIAL of the ways different kinds of stands could interact with hamon. also vampires are cool as shit, and i think some ‘regular’ stand users from p4+ would shit themselves if they saw someone just… punch a building into dust without needing a stand

6 notes

·

View notes

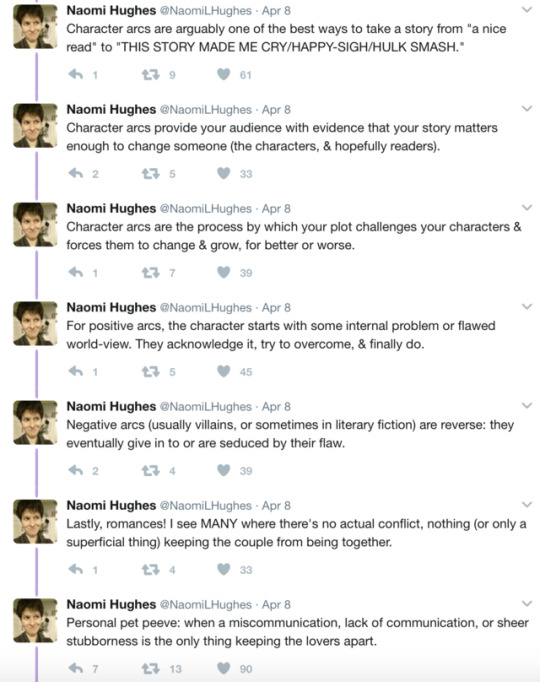

Photo

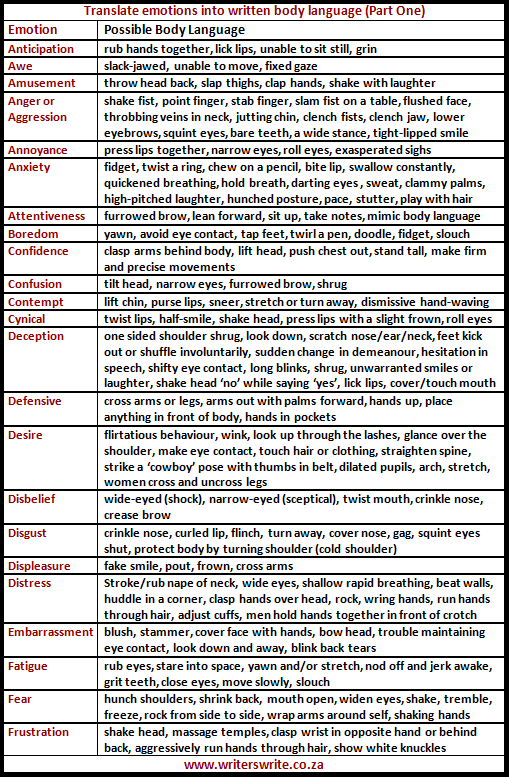

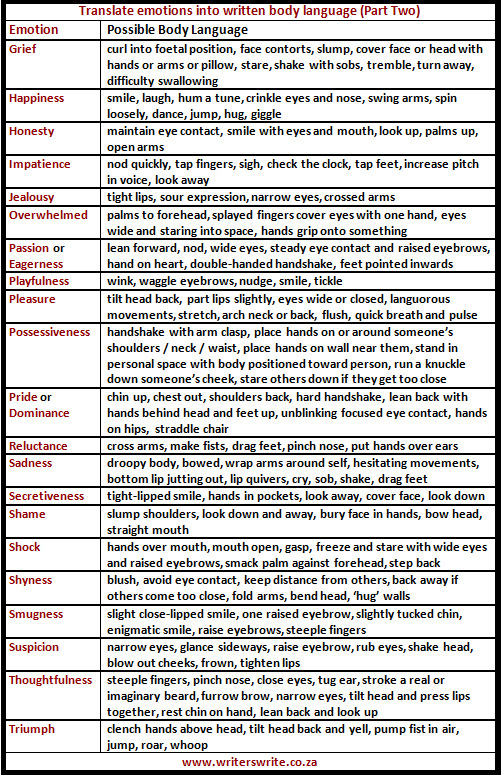

Cheat Sheets for Writing Body Language

We are always told to use body language in our writing. Sometimes, it’s easier said than written. I decided to create these cheat sheets to help you show a character’s state of mind. Obviously, a character may exhibit a number of these behaviours. For example, he may be shocked and angry, or shocked and happy. Use these combinations as needed.

by Amanda Patterson

360K notes

·

View notes

Note

What's a good way to prepare for NaNoWriMo? I'm really deciding to go for it this year with a novel idea I've been trying to get motivation to do for years. But I have no idea on how to actually... get started. Do I plan out the general story beats before November, do I just start writing?

YOU ARE TOO LATE TO DO ANYTHING BUT PANIC, but really, don't panic.

PREP: If you have time this weekend, try to write those beats down. I like to have a big posterboard to slap sticky notes or flashcards on with scenes, important plot points, etc, but whatever you can do in whatever makes sense to you, do it.

TIME: What's more important is looking at the month ahead and figuring out where you can carve out writing time (and space) ahead of time. No amount of prep work in the world will take the place of actually doing the work, so getting up an hour earlier, or unplugging an hour sooner to get some writing done is something you can work out now.

TRACKING: Create an account on the website! It has its flaws but it does give you a really good stat counter and an easy way to add your daily word counts. The forums........ Well, exist. You might find them useful, moreso for hanging out with a local group. It can also be fun to make your own bullet journal to track word count or goals.

BUDDIES: Rope some friends into a discord, or find one already running! NaNoWriMo is always easier to do with others, I've found. Word sprints go better in packs!

REWARDS: Get yourself some cute stickers and a make a goal tracker to slap them on. Go do it, there's a ton of Halloween stickers out there now. It's fun!

On that note REMEMBER TO HAVE FUN! NaNoWriMo is supposed to be fun, even with the suffering involved. If you are completely miserable by the experience every time you sit down to write, stop. It's not worth it if you don't enjoy it. There's literally nothing wrong from stepping back if it's not working for you.

502 notes

·

View notes

Text

You probably hear a lot of "DON'T EDIT AS YOU WRITE" advice, don't you? 😬

This is a dangerously vague piece of advice and one that's often taken too literally. Here's a quick breakdown of edits that are actually GOOD during writing.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

If your plot feels flat, STUDY it! Your story might be lacking...

Stakes - What would happen if the protagonist failed? Would it really be such a bad thing if it happened?

Thematic relevance - Do the events of the story speak to a greater emotional or moral message? Is the conflict resolved in a way that befits the theme?

Urgency - How much time does the protagonist have to complete their goal? Are there multiple factors complicating the situation?

Drive - What motivates the protagonist? Are they an active player in the story, or are they repeatedly getting pushed around by external forces? Could you swap them out for a different character with no impact on the plot? On the flip side, do the other characters have sensible motivations of their own?

Yield - Is there foreshadowing? Do the protagonist's choices have unforeseen consequences down the road? Do they use knowledge or clues from the beginning, to help them in the end? Do they learn things about the other characters that weren't immediately obvious?

84K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Advice From Experience 1 - Blood loss

1. When you first lose blood, it doesn’t feel that bad immediately, you won’t actually notice it.

2. After 10 minutes and with you moving around, you will start to feel cold like you’re sweating and your muscles ache.

3. Your face feels cold and you might get something akin to a headache. This is when you feel like you want to sit down.

4. Your vision will blur before going black at the edges and your limbs start tingling.

5. With the impaired vision your body will have a hard time balancing so any attempt you make is overcompensated, making you move more than you intended or crash into wall.

6. Your pulse will increase, like you can hear the heart pounding away along with some static noise in your ears as if you’re standing next to a waterfall but directly in your ears.

7. You will later feel hot and then cold again. It will be like a roller coaster.

8. Trying to move without properly resting first will make your symptoms come back twice as bad!

9. It can affect you hours after initial blood loss event!

This information has been brought to you by me donating blood and not preparing properly. Fun stuff 11/10 would recommend for the experience alone, free snacks is a win along with learning your blood type.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Tips

Punctuating Dialogue

✧

➸ “This is a sentence.”

➸ “This is a sentence with a dialogue tag at the end,” she said.

➸ “This,” he said, “is a sentence split by a dialogue tag.”

➸ “This is a sentence,” she said. “This is a new sentence. New sentences are capitalized.”

➸ “This is a sentence followed by an action.” He stood. “They are separate sentences because he did not speak by standing.”

➸ She said, “Use a comma to introduce dialogue. The quote is capitalized when the dialogue tag is at the beginning.”

➸ “Use a comma when a dialogue tag follows a quote,” he said.

“Unless there is a question mark?” she asked.

“Or an exclamation point!” he answered. “The dialogue tag still remains uncapitalized because it’s not truly the end of the sentence.”

➸ “Periods and commas should be inside closing quotations.”

➸ “Hey!” she shouted, “Sometimes exclamation points are inside quotations.”

However, if it’s not dialogue exclamation points can also be “outside”!

➸ “Does this apply to question marks too?” he asked.

If it’s not dialogue, can question marks be “outside”? (Yes, they can.)

➸ “This applies to dashes too. Inside quotations dashes typically express—“

“Interruption” — but there are situations dashes may be outside.

➸ “You’ll notice that exclamation marks, question marks, and dashes do not have a comma after them. Ellipses don’t have a comma after them either…” she said.

➸ “My teacher said, ‘Use single quotation marks when quoting within dialogue.’”

➸ “Use paragraph breaks to indicate a new speaker,” he said.

“The readers will know it’s someone else speaking.”

➸ “If it’s the same speaker but different paragraph, keep the closing quotation off.

“This shows it’s the same character continuing to speak.”

76K notes

·

View notes

Note

When writing characters with mobility aids, how often should the mobility aids be mentioned? Do I need to specify where they put the cane when sitting down/that they pick it up before standing? Is it appropriate to say that he walks across the room without mentioning his cane? I don't want to avoid acknowledging it, but I also don't want to constantly remind the reader, as that feels redundant. Thank you!

Hello! Thank you for asking. I think you are right to want to include it without being redundant.

I think, in general, it is fine to not explicitly mention the cane much of the time. I think it’s more important in the beginning of your story to help get readers used to imagining this character with a cane, but as the story goes on, I think it can get easier and easier to not worry about mentioning the cane every single time unless it becomes important, such as deliberately mentioning that this time he is not using it for whatever reason or something along those lines. Or unless it becomes interesting to mention it, such as when something about it is out of the ordinary, such as the character placing it somewhere different from normal for some particular reason or using it in a way they normally don’t for whatever cause.

I would focus on working it in casually though, especially in the beginning of your story. Think of it the way you would mention a character carrying around a cup of coffee or something. It’s not a huge focal point, but the narrative does still casually mention how the character picked up his coffee mug and went over to chat with some coworkers. It isn’t the subject of the scene, but it is still mentioned in a way that incorporates it casually without beating the readers over the head with it, so to speak.

I personally quite like seeing occasional casual mentions of a disabled characters mobility aid, because it does subtly remind you that the character is disabled and uses a mobility aid and helps you remember to imagine it, but does it in such a way that it doesn’t pull your focus away from the actual subject of the moment by making a big production out of grabbing their cane. I love when I don’t hear it mentioned a ton, but there are little subtle lines sprinkled in the way you would sprinkle in any other object or tool. I love little tasteful lines like these:

She came inside covered in sweat, dropped her cane beside the couch, and flopped down—luxuriating in the wonderful coolness of the air.

“I think we’re done here,” he said, the corners of his mouth pinched and tight. And with that, he stood, retrieving his cane from the corner behind his chair and exiting the room, never once looking back.

This time, she ran. He was hot on her tail and all she could do was sprint through the hotel at top speed, tearing around corners and holding her white cane as far out in front of her as she could manage, the sharp, rapid taps mixing with the sound of her own ragged breaths.

These are all examples of working a mobility aid into a scene in a way that helps the reader remember that the character has one, but also doesn’t make the whole scene about the mobility aid when the scene has nothing to do with it. These can be fun little things to sprinkle in occasionally, especially since a couple of them are scenes in which the character is using the mobility aid in a slightly less typical way from what they probably normally do.

Again though, these are just snippets that you would work in once in a while. You don’t have to write mentions like this into the narrative every single time your character moves. I’d still suggest working in casual lines like this a little more frequently in the very beginning, but letting it settle into assumed used after that and only making casual mention of it occasionally, the same way you would any other object or action that isn’t necessarily the focal point but still adds a little bit of flavor and mental imagery.

Mod Lane

354 notes

·

View notes