Text

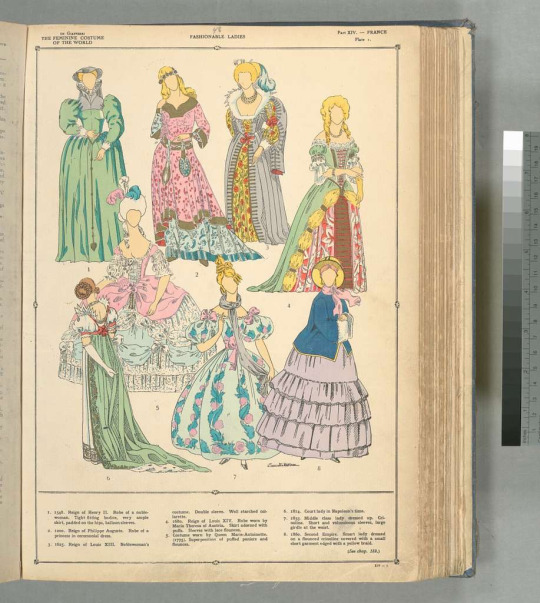

FWIW, "mauve" was one of the coal-tar dyes developed in the mid-19th century that made eye-wateringly bright clothing fashionable for a few decades.

It was an eye-popping magenta purple

HOWEVER, like most aniline dyes, it faded badly, to a washed-out blue-grey ...

...which was the color ignorant youngsters in the 1920s associated with “mauve”.

(This dress is labeled "mauve" as it is the color the above becomes after fading).

They colored their vision of the past with washed-out pastels that were NOTHING like the eye-popping electric shades the mid-Victorians loved. This 1926 fashion history book by Paul di Giafferi paints a hugely distorted, I would say dishonest picture of the past.

Ever since then this faded bluish lavender and not the original electric eye-watering hot pink-purple is the color associated with the word “mauve”.

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Why are you dressed as a man?”

“To flirt with a woman, duh.”

An excerpt from the trial of Elinor Crane, who was arrested in Middlesex in 1693 on suspicion of burglary. A witness claimed one of the burglars was a woman in men's clothing, and Elinor had previously been seen in the area dressed as a man.

"But the Court asking her why she went in Mans Apparel, the Prisoner replyed, She went to Wooe a Widow. Upon the whole Matter the Jury brought her in not Guilty."

(source: Old Bailey Proceedings: Accounts of Criminal Trials, April 26, 1693.)

12K notes

·

View notes

Photo

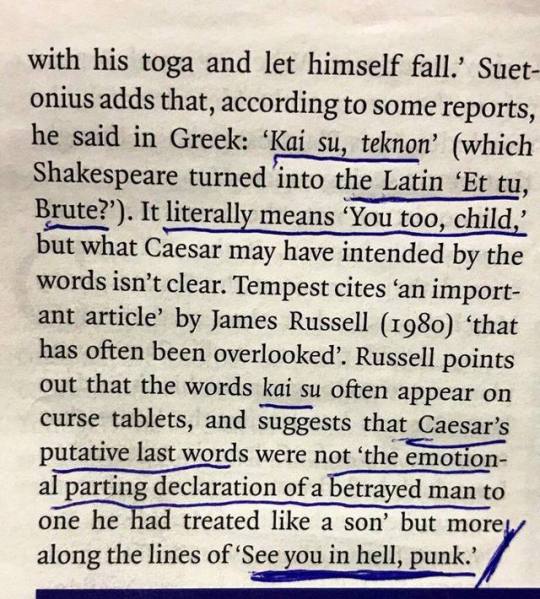

OK, but there’s somehow even more pathos in the idea that Caesar’s words to Brutus were “Curse you, child.”

Like, the juxtaposition of the endearment ‘child’ with the curse... I just

what a fucking power move

75K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Daily Mirror, England, May 14, 1920

Image © The British Library Board. All Rights Reserved.

5K notes

·

View notes

Photo

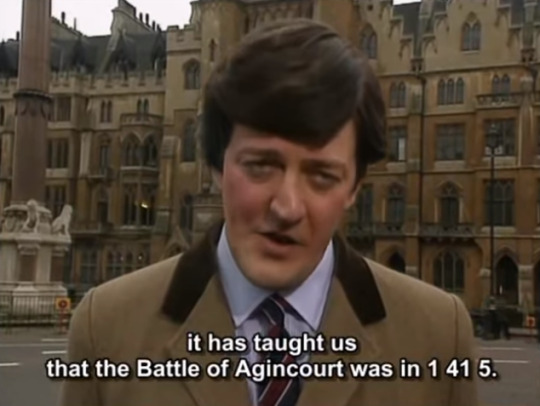

A Bit of Fry and Laurie (1989–1995)

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mallard was so streamlined that they had to intentionally make it less streamlined so that the smoke didn’t get into the carriages.

They supposedly worked out how to prevent the passengers all getting smoked like kippers after one of the engineers accidentally left a finger print on the model they were using in the wind tunnel, and that fingerprint was reproduced on the actual train.

Post train facts and I will rate them out of 10

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth I’s Privy Council didn’t always get along with each other but honestly compared to Henry VIII’s Privy Council they look like the Brady Bunch.

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

Curses losing context to history is interesting. Apparently the finnish insult "hunsvotti", generally translating to lout, scroundel or rascal - a term so mild and soft that it wouldn't even occur to you to consider it cursing, but something to be used as an insult in kids' shows and by people too tidy in their language to say "darn" without blushing - originally came from swedish, hundsfitta, literally "dog's cunt".

Which makes it easier to make sense of the records of finnish court cases from like 1500 to 1700 where somebody stabbed someone else for calling them that.

3K notes

·

View notes

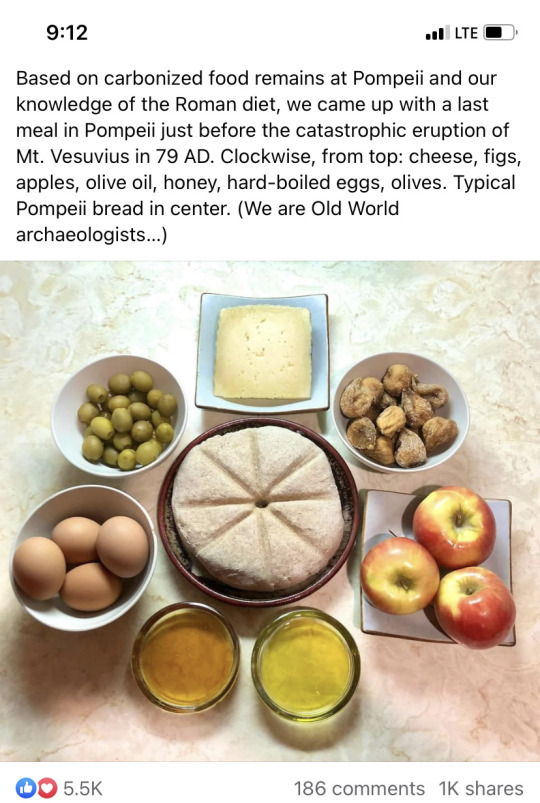

Text

this slaps honestly

70K notes

·

View notes

Text

If England had a nickel for everytime a Queen Mary had a sister that feigned ill health to avoid going to a church service with them they’d have two nickels, which isn’t a lot but it’s weird that it happened twice right?

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keep reading

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The closeness of the royal couple’s relationship was reflected in the architecture of their living spaces. Mary Whiteley compares the physical space of royal palaces in England and France. Between 1357 and 1368, Edward III remodeled part of Windsor Castle, which formed the main residence for Philippa of Hainault and their children. Philippa had given birth to two of their children at Windsor, Margaret in 1346 and William in 1348, and Edward held a number tournaments there, two of which were in celebration of Philippa’s churchings in 1348 and 1355. Although Philippa’s rooms were smaller and fewer in number than those of the king, the king and queen’s chambers were on the same level and their bedchambers close together, despite the facts that by the completion of Edward’s renovations, Philippa had already borne her last child in 1355. In comparison, the rooms that Jeanne de Bourbon (1338-78), wife of French king Charles V, occasionally stayed in at the Louvre palace were on the same level below that of her husband, although similar in size and shape. In their familial residences of St-Pol and Vincennes, Jeanne’s rooms were in an entirely different building, although with a connecting corridor at St-Pol. The difference in architecture may be attributable to their preferences or the relationships between the couples. Despite his changes to Windsor, during Edward’s reign, the layout of the queen’s rooms at palaces such as Westminster remained similar to their original design for Eleanor of Provence, wife of Henry III, at a distance from public areas. Likewise, at Kennington, Edward the Prince of Wales, built rooms for his wife [Joan of Kent] overlooking the gardens and away from the public areas, with no processional access and distanced from Edward’s rooms. The layout remained unchanged under Richard II and Anne of Bohemia. As Richard favoured this palace, perhaps because of the connection to his father, the unaltered states may have been sentimental rather than practical. However, the general changes in the principal royal residences, which had transformed the fortified castles of the twelfth century into more luxurious palaces by the fourteenth century, also reflect the increase in royal splendour under Edward III and Richard II. Although differences between the palace layouts represent general patterns in royal architecture, the layout of Windsor does suggest that Edward intended to live close to Philippa.”

— — Louise Tingle, Chaucer’s Queens: Royal Women, Intercession, and Patronage in England 1328-1394 (pages 22 and 23)

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.

Happy Tudor Christmas!! Best wishes for all the fans of Elizabeth and the Tudors!! I love you so much guys!

564 notes

·

View notes

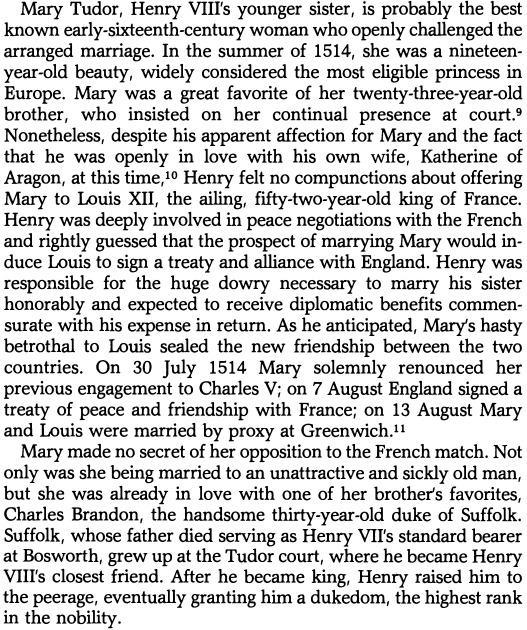

Photo

ℑ𝔫 𝔱𝔥𝔦𝔰 𝔪𝔬𝔫𝔱𝔥 𝔦𝔫 𝔗𝔲𝔡𝔬𝔯 ℌ𝔦𝔰𝔱𝔬𝔯𝔶 🏵

#15th century#16th century#early modern#renaissance#history#tudor#mary I#mary tudor#Louis xii#Edward vi#catherine of aragon#margaret tudor#jane seymour#thomas moore#mary queen of scots#Henry VII

766 notes

·

View notes

Text

Persuasion: The Paperwork Problem

I am obsessed with the fact that Captain Wentworth does Mrs. Smith’s paperwork for her, and not just because having a male romantic protagonist do paperwork as part of demonstrating his ultimate worthiness (and swoon-worthiness) proves that no one is doing it like Jane Austen. No, I am obsessed with it because Britain’s transatlantic economy is in flux in the early nineteenth century. And because this Persuasion reread has convinced me that Austen does everything in this novel on purpose to make me suffer. Here is my theory: what Wentworth is doing is divesting from slavery. What? you may exclaim, gentle readers, and I am here to lay evidence for my tenuous little theory before you.

Point 1: Wentworth’s behavior here is explicitly contrasted with that of Mrs. Smith’s wastrel husband. These are alternate models of masculinity. And Mrs. Smith’s narrative for Anne very clearly links not only the late Mr. Smith’s moral corruption with his mismanagement of this property, but also Mr. Elliot’s lack of moral backbone with his failure to manage it for her. And this is property “in the West Indies,” which at the turn of the nineteenth century means basically one thing: sugar. And sugar, in turn, means slavery. But things are changing! From 1807, the transatlantic slave trade is illegal in Britain and its possessions. I’m not going to dwell here on the obvious ongoing horrors of slavery, but one of the relevant consequences here is that the plantation economy of the British West Indies basically tanks. …Sort of, at least. There’s scholarly debate on the question of how much this happens, why it happens, and when it happens. Which brings me to:

Point 2: whichever combination of factors we accept for the decline of the plantation system – Napoleonic Wars, beet farming in South America, British economic commitment (eventually, sort of) to the abolition of slavery – it makes sense for Wentworth’s management of Mrs. Smith’s property to be part of this. Admittedly, Persuasion is a novel where, in contrast to Mansfield Park, the vast and sinister machinery of the British Empire is allowed to be mostly invisible, especially to the modern reader. But we are told that Mrs. Smith suffers partly because the property is “under a sort of sequestration,” in theory (or initially) to pay Mr. Smith’s debts, but now controlled by the courts because of some combination of greed, incompetence, indifference, and inertia. And Wentworth knows, he knows to his core, he knows from experience, exactly how cheaply the empire values the lives of its subjects. We, in turn, know that he knows this because of light dinner table conversation. Jane Austen, everyone.

Point 3: Jane Austen makes choices about what to emphasize in Wentworth’s naval career. There are a lot of glamorous actions that he could have been linked to. But there’s no name-dropping of the Nile or Trafalgar. No, most of what he’s been doing is chasing privateers and French ships, maintaining a balance of power favorable to the British interest, and making a lot of money while doing so. And routinely risking his life in ways that make Anne very distressed even in retrospect. The exception, the only named military endeavor to which Frederick Wentworth is linked, and which earned him a promotion, is “the action off San Domingo.” This stunning British victory was, of course, aimed at breaking French power in the Caribbean. And this is what we get told about. Among other things, this means that it’s entirely possible that Wentworth also saw action in the Haitian Revolution (again, the British involvement in this was cynical. But still.) Also relevant here, I would argue, is that we are told that the Crofts have never been in the West Indies (and Mrs. Musgrove, a perfectly nice woman but also one perfectly capable of blinding herself to unpleasantness, cannot accuse herself of having ever called Caribbean islands anything in the whole course of her life.) I am convinced that all of this, in this minor miracle of a novel, matters.

Point 4: economic logic. In 1815, there is no way for Mrs. Smith’s economic fortunes to recover and her property to start creating (rather than losing) income if she is trying to manage a sugar plantation. It’s just not going to happen. In a way, this is coming back to Point 1, but without the character-driven elements. If we take this seriously as plausible, I think we have to draw the conclusion that Wentworth has taken in hand arrangements to alter how that property is being used.

Point 5: Anne. The first thing we learn about Anne is that she is not only willing but eager to force irresponsible members of the landed gentry – even her own family, especially her own family – to give up luxuries which they think of as necessities. This is the context in which we are introduced to her. This is the first way we learn who Anne Elliot is. The first thing we are allowed to see Anne wanting is “indifference for everything except justice and equity.” In other words, this is a woman who refuses sugar in her tea. And however different she and Wentworth are in temperament, we are also told (from Anne’s perspective!) that there are “no tastes so similar, no feelings so in unison.” So I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to take her morality as an indicator of his probable actions.

In short: I think Persuasion’s coda can be read as anti-slavery. Because of paperwork.

424 notes

·

View notes

Link

Finally, a historical show about the lives of ordinary working people, not a bunch of Dukes and Princesses with titles a yard long…

Victorian Farm is one of a prolific series of historical reenactments/education programs from Absolute History, most of them starring Historian Ruth Goodman, and Archeologists Alex Langlands and Peter Ginn, though Tom Pinfold takes Alex’s place for Tudor Monastery and Secrets of the Castle, and I haven’t yet watched Victorian Pharmacy.

Every episode of every series listed here is available from youtube at the time of this writing, for free.

The basic formula is simple: The cast are challenged to live, dress, and work as lower to middle-class tenant farmers or workers for that period in history for a full calendar year.

The weird, delicious recipes! The bootleg sloe gin! The Tamworth hogs evading capture! Haymaking, Beermaking, cheesemaking! Coping with cross-grained cattle and horses, and deeply stupid sheep! The Infamous codpieces! Blacksmithing, fishing, sheep-shearing! Early industrial working-condition horrors! Rural traditions and rituals, usually presented by the slyly humorous and deeply knowledgeable Professor Ronald Hutton.

In order, the series I’ve watched are:

Tales From the Green Valley (Welsh border farm during the reign of King James the 1st)

Think of this series as a worthy prequel. It’s quite interesting, but they had yet to nail down who the permanent crew should be, and the production values are still quite basic.

Victorian Farm (Shropshire farm during the reign of Queen Victoria)

Arguably the best series, this was the first full year pairing Peter, Ruth and Alex as a team, and it’s set on the Acton-Scott estate, still owned by the family who owned it a century ago, the surviving members of which are… let’s say very glad to have tenant farmers acting out their historically-preserved land’s true purpose once more.

Edwardian Farm (Devon farm in the Tamar Valley, during the Reign of king Edward the 7th, just before WWI.)

Inexpressibly raw, and just within the reach of living memory, this documentary experiment explores the ways new technologies like the railway, modern mining and textile industries changed the lives of people living in Devon at the time.

I have a particular interest in this one because some of my own relatives, a young mining engineer and his wife, left the nearby Cornwall area for America just before this series takes place. And having watched it, I can definitely see why…

Wartime Farm

Set during the sustained and deadly sea blockade of WWII, this explores the challenges and changes faced by the farmers of England at the time, as they resisted the Nazi efforts to isolate and starve out the British isles.

I’m not sure if this series would be good or bad to watch with very old people who lived through this time, but they would certainly have an opinion on it…

This one has an echo that’s hard to shake.

Tudor Monastery (set roughly 500 years ago in West Sessex, during the reign of King Henry the 7th)

This series follows the efforts of the team as Tenant farmers of a Catholic monastery just prior to the religious reforms/upheaval enacted by King Henry the 8th. More peas than I’ve ever seen before, the first printed books, the emergence of technology from sorcery, and of course regrettable hosiery.

“Merrie England, for heaven’s sake…”

Secrets of the Castle (unusual among the other series, in that it is set in 13th century France, not England, at the site of a remarkable modern-day historical reconstruction project, the Guédelon Castle)

This thing is unbelievably huge. Hovels. Grain-arcs. What castles really looked like when they were in use. Siege warfare. Well-cooked pork. The geometric secrets of Masonry. …And a number of adorable resident Owls.

Full Steam Ahead (This one follows the establishment of the railway system in mainland Britain, and the effects of a National and soon after Global economy on everyone within reach of it’s stations.) Technical details, early railways, working preserved trains, trade, and loss of limbs by workers, horrific medical cover-ups about industrial disease, and the global boom for scotch whiskey. Old-time fish and chips, and midnight Rhubarb, this series peels the lid off a lot of things even locals may have seen… without really knowing. (Arguably the engineering-minded and perpetually filthy Peter’s contribution to the series, this one was unique in that it didn’t have the ‘for a full calendar year-’ formula.)

#victorian farm#ruth goodman#alex langlands#peter ginn#history#bbc#tudor monastery farm#wartime farm#tales from green valley#Edwardian farm#full steam ahead#Victorian pharmacy#Victorian#19th century#edwardian#20th century#1900s#1910s#stuart#17th century#1940s#second world war#tudor#16th century#age of steam

475 notes

·

View notes