Text

Part 5: Wrapping Up Europe

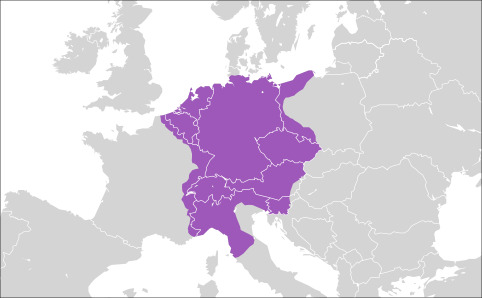

(Holy Roman Empire)

I am not gonna lie, that last section exhausted me. It took some time to get back into a researching worthy headspace. Regardless, this section will be much shorter and will put us up to speed so that we can end with the Salem Witch Trials, and perhaps some modern witch hunts and why that terminology is confusing for the U.S. President to use.

These next trials have casualties numbering in the thousands and occur during one of history’s most tumultuous time periods. Beginning with the Würzburg Trials in 1626, the executions lasted through 1631 with only 219 taking place within the city proper. By comparison, Bamberg, a city with the largest death count, numbered in the thousands. A bit of background before we dive in—the Holy Roman Empire (800-1806) encompassed much of central and western Europe, including all of what is now Germany. During the late 16th/17th centuries the world experienced a period of atypically cold temperatures that caused crop failures, deep freezes, poor survival of livestock, and a higher risk of disease. This is referred to as The Little Ice Age, and as you can imagine pushed tensions to a precipice and made people suspicious. Quickly, all of the calamity that had befallen the common man was blamed on the mystical, and it was believed that only a supernatural force could account for the loss a normal way of life. As we progress through a few decades, there were sporadic executions for witchcraft under each prince-bishop’s rule in Bamberg; however, the real trouble starts with Johann Georg Fuch von Dornheim in 1626. One night a severe frost decimated crops and livestock in a large area, and the slowly fizzled-out witch hunts resumed their prior intrigue—this time with a few major changes. Times were tough, and officials needed a better way to execute witches without wasting precious firewood, so a large crematorium was constructed in the epicenter of the executions. Additionally, Bamberg constructed a large prison to house the insurmountable number of accused. The prison called a Drudenhaus or Malefizhaus, were large structures built with single cells for individuals as well as larger cell sections that could house larger groups of prisoners. The structure in Bamberg, has been all but completely destroyed in our current time, and we have little information on what it actually looked like, but what we do know comes from prints that were illustrated within a pamphlet distributed during the time of the executions. In the prints we can see some of the layout of these prisons as well as some inscriptions on plaques above the entrance.

“And at this house, which is high, every one who passeth by it shall be astonished and shall hiss; and they shall say, ‘Why hath the Lord done thus unto this land and to this house?’

9 And they shall answer, ‘Because they forsook the Lord their God who brought forth their fathers out of the land of Egypt, and have taken hold upon other gods, and have worshiped them and served them; therefore hath the Lord brought upon them all this evil.’”(1 Kings 9:8-9)

The other passages were in a medieval dialect of German that was difficult to translate, so I did not, but there were also passages from the Bible covering the walls within the hallways. Those accused of witchcraft were held here and tortured. I don’t know if any of this is starting to sound really familiar or not, but it seems to me as if it shares a few similarities to a large-scale genocide that occurred about three centuries after these events.[1]

(Picture Public Domain)

One of the most important sources of information that we have regarding the torture of prisoners is the letter that one of the victims, Johannes Junius, had written to his daughter explaining his confession of practicing witchcraft. He mentions in the letter that he had already been tortured, and that some kindly executioner told him that if he didn’t confess in some way that he would continue to be tortured until it killed him. Since Johannes had already faced severe torture, he decided to take the less painful route and confess to the crimes that he was falsely accused of. In the margins of the note he details that some of his accusers apologized to him because they were also forced to accuse him with the threat of torture.[2] The executions and torture went on for quite some time until the working class began to realize that no one was safe from the accusations which were synonymous with execution at this point, and began to refuse to contribute fire wood, or other important materials that were needed to perform the executions. The final nail in the coffin, after the chancellor of Bamberg himself, was the execution of a wealthy woman named Dorothea Flock. She was the second wife of the city’s councilor whose first wife was also executed for witchcraft. Dorothea’s family quickly tried to have her released and every effort was thwarted. Eventually, her husband entreated the highest council of Germany known as the Hofrat to send release documents to have her taken out of the prison and returned home. However, the witch hunters were tipped off about the arrival of the letters, and they executed Dorothy before they had a chance to be delivered. This did have a positive outcome, though, and the trials were halted pending an investigation by the Hofrat in 1630, leading the Catholic Church to blame the bishop for the issue. There remained a small trickle of executions for two more years until the Swedish Protestant troops arrived in Bamberg and released the remaining prisoners asking that they refrain from divulging information regarding the activities taking place inside the prison walls.

The last European trial I wanna talk about is not so much a trial as it is a giant historical scandal which are by far the most fun topics to research when sifting through a ton of material. It is called the Affair of Poisons, and it took place in France during King Louis XIV’s rule between 1677-1682. This is not a prominent number of casualties; however, it is one of the closest occurrences to the trials that occurred in the American Colonies. I find this particular event especially interesting because this is the only case where some essence of a realistic explanation is the root cause of the accusations and consequential executions. It all began with a tale as old as time—an arbitrary case of a woman conspiring to poison her father and two brothers so that she and her lover could inherit the estates and money. The accused, Marie Madeleine d’Aubray, marquise de Brinvilliers, was a part of a Parisian fad to dabble in the spiritual and exciting aspects of magic, and she visited her regular spiritual councilor to procure the poison that she used to murder her family. Often this popular fad would include seances, fortune-telling, and love potions that were very très chic at the lavish parties that the French aristocracy was widely known for, and its popularity spanned the gap between classes including bourgeoisie and poorer peoples of France.

The fun was short-lived, however, and Marie’s trial drew a lot of attention and spurred the anxieties of other nobles who were afraid something similar might happen to them. A special court was instituted to help quell these panic-driven accusations. Known as chambre ardente, or burning court, the court held 210 sessions over three years and issued 319 arrests.[3] Once fortune tellers were arrested for providing poisons to murderers, they gave up lists of their clients—these lists gave no distinction between those who might have had a spiritual reading versus those that had purchased a poison with the intent to murder someone. The most famously known execution is that of Madame Monvoisin, whose client list included marquises, family of clergy members, military heroes, and many more of France’s most elite members of society—including, Madame de Montespan, mistress to the king. Montespan was accused of having won the king’s love via potions and other nefarious and manipulative magical means, but it is important to note that she was interrogated while intoxicated and was never proven to have taken part in these dealings. The tribunal that was established to deal with these cases is notable because it is one of the only witch hunts to have been conducted so professionally, and with far less of the hysterics that were typical of other trials on this scale. There were only 36 people sentenced to death and many others were not even brought to trial.

So concludes our European adventures, and I think that we can without a doubt say that it doesn’t even begin to end there. There are still so many other cases that I didn’t look into because of the sheer amount of information that needed sorting through, but I hope that the important information about this topic was conveyed clearly and in a memorable way. I know that I certainly learned a lot from this part of the project, and I’m looking forward to finishing it with the conclusions we can draw, the historical implications of these events, and the parallels that we can draw from these events that reflect on recent and current events. See you guys in America circa 1692!

[1] That would be the Holocaust that I’m referring to here. You know, the one where they built prisons that they tortured people in on massive scales? Wait, wasn’t that about religious intolerance too? It’s almost like it’s always about religious intolerance….weird

[2] (History Muse, 1628)

[3] (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2010)

#witches#witchcraft#witch trials#european witch trials#bamberg#bamberg witch trials#the affair of poisons#king louis xiv#france#germany#madame monvoisin#history#european history#the little ice age#early modern period#holy roman empire#itshistoryyall

0 notes

Text

Part 4: Burn Them All

photo credits: here

A little foreword before we begin:

I had to start over for this part because, I’m gonna be honest, it’s a mess. For some reason historians have this aversion to keeping history in a tidy chronological order, and I’m not sure why, but I basically had to sift through other people’s research for multiple days and then come up with a game plan for how all of this was going to be laid out. To put into perspective just how large this part of the research was, I made this photo of the links that I found on Wikipedia.

The rest of this will include only the trials that I wanted to research or thought were interesting or had some sort of historical importance, so if you feel like there’s one I didn’t mention and you would like researched, please email me or PM me and I will do my best to do a separate post about it. I have to admit, it was just too much for me to do without spending a few weeks researching. Now, back to the good stuff.

In the mid-1500’s we begin to see a wide-spread persecution of alleged witches and a mass hysteria driven by religious persecution and fear of accusation. This time period between 1560-1630 is considered by most historians to be the bulk of the trials, and that idea is backed up by sheer numbers. The death toll from these trials is somewhere in the 40,000-50,000 range, though, historians of the past have wildly unpredictable and outrageous estimates numbering in the millions. Taking into account a “normal” level of fatalities for crimes outside of witchcraft, plague fatalities, and normal death rates, it’s a bit safer to assume somewhere in the thousands 40-50,000 even seems a bit steep to me, but no one can ever know for certain. The important thing to takeaway from this was that it was a lot. In this section we’ll be focusing on the trials that have enough historical information to be granted a name and some basic description located somewhere other than Wikipedia, or (more likely) the ones that piqued my interest most. Those are as follows: The Witch Trials of Wiesenteig, Trier, Berwick, Bamburg, Nogaredo, the Pappenheimer Family, Pendle Witches, and the Affair of Poisons. The Salem Witch Trials are a unique set of events that I feel require special attention and will therefore write on that subject separately. size

As we learned from Part Three, these trials began in a region of southern Switzerland and spread from a French-speaking side to a German-speaking side, so from that we can deduce why the first major trial took place in Germany. The Wiesenteig Witch Trials began in 1562 amassing a death toll of around sixty and earning its reputation for the first mass execution of this magnitude[1]. To understand why we saw such extreme numbers here, we need a little background. The city of Wiesensteig, like many other cities in Europe,[2] was facing a difficult few years. Some might call these things simply unfortunate, but not Wiesensteig. They were clearly cursed by witches because no other city in the world could possibly have inclement weather, the Bubonic Plague—among other epidemics, and (I think at this point it goes without saying, but alas) religious turmoil! So obviously, the first course of action after a particularly brutal hailstorm in 1562 was to arrest a few ladies for witchcraft. Of the accused, six were made to confess through torture and were executed, but before facing their punishment they claimed to have seen several other women at their Dark Sabbath[3]. The women that were named from neighboring Esslingen were soon arrested, and then shortly released leaving authorities in Wiesensteig outraged by the lack of sentencing. In reaction, Weisenstein saw forty-one more executions. In December of 1563, the execution of twenty more women was approved leading ultimately to the production of a widely used pamphlet, True and Horrifying Deeds of 63 Witches. Further executions in the area occurred in 1583, 1605, and 1611 leaving an estimated total of ninety-seven women who perished.

These were certainly not the largest trials to have occurred in Germany, however the Trier Trials taking place in the diocese of Trier near the borders of France, Belgium, and Switzerland[4] certainly left their mark on the world. We can’t know for sure the number of casualties because existing records of the trials only include those that occurred within the city-limits, and they do not include statistics for the entire diocese or those that may have perished via torture or while imprisoned. The number that most sources reference is 400; however, it’s likely that the number closer to the thousand mark rather than the low hundreds, and as such it can be an assumed low estimate of the actual number of deaths. This incident is considered the largest mass execution of peoples during an extended period of peace in Europe’s history.

The appointed archbishop of Trier in 1581, Johann von Schönenberg, was quick to order a purge of three groups that he didn’t like very much. That included Jews, Protestants, and lastly, witches. Due to Johann’s support for these trials, we see a large upturn in the popularity and commendation of these executions among increasingly more church officials. The largest number of executions took place between 1587 and 1593 when 368 people were burned at the stake in twenty-two villages. The number of those executed was so heavily comprised of women, that a couple of villages were left with only a single female resident amongst the living, but that is not to say that it was only women who were executed for sorcery. A large number were members of nobility, held positions in the government, or were people of influence, and of the victims, 108 were men. One notable male victim was rector of a university and a chief judge in the electoral court who didn’t approve of the trials; Dietrich Flade, the rector/judge, doubted the effectiveness of torture practices and opposed the violent treatment of the accused, and as such, was arrested and subjected to the same abuse as those he was attempting to protect. His execution was a turning point, and it effectively ended any opposition to the trials in Trier and making way for hundreds more burnings.

I would like to issue a trigger-warning for the sensitive material that is to follow. It is graphic, detailed, and gruesome, so please do not read further if you feel sensitive to these subjects.

One other case worth mentioning in Germany is the Pappenheimer Family Trials. Though it was a small number of fatalities, it was unusually well documented for the time and that gives us a great deal of written detail to refer to when describing the torture practices in these trials. The family comprised of a mother, father, and three sons—Simon (22), Jacob (21), and Hoel (10). The mother, Anna, was born the daughter of a grave-digger and began life on the fringes of society, and her husband, Paul, did not fare much better in life as an illegitimate child and day laborer. Throughout their lives they lived apart from most of society and were likely not even treated kindly by other poor laborers. In fact, the surname suggests that the family was in the business of privy maintenance and cleaning, and it was not their original surname. The real family name was Gämperle, and they were in for a fate much worse than name-calling after Paul was accused of murdering pregnant women in order to gain magical benefits from their unborn fetuses. The whole family, aside from their youngest son, was subjected to cruel and relentless torture until they had confessed to hundreds of unsolved crimes over the past few decades including murder of the elderly and children, spoiling cattle, thievery, and burning people alive in their beds.

On July 29, 1600,the following took place: the eldest sons and their parents were brought before the town along with two others accused of witchcraft, Anne was placed between her two sons, the executioner cut off her breasts, and then he proceeded to beat her and her sons in the face with them three times each. Next, Anne was whipped five times with a “twisted wire,” then both of her arms were broken on the wheel, and her body was immediately burnt. Next the men’s arms were also broken, they all received five lashes with the twisted wire whip, and all of them except Paul were tied to the stake and burned. Paul was then spitted alive and roasted to death, and then once he was dead his body was also burnt.[5] This was all displayed for the entire town to see and was then used as a punishment for ten-year-old Hoel, who was made to watch the entire ordeal. Later that year he was also tortured, strangled, and then burned at the stake after having confessed to eight murders on his own. The importance of pointing out these torture proceedings is to make a reference point for how tortures took place during these executions, and to give you an idea of what this could look like at each and every execution described hereafter.

For our next trial, we turn to Scotland’s famous witch trials where, purportedly Shakespeare gained the inspiration for one of his most famous tragedies, Macbeth, and where we begin to see an association with witches and the natural forces of weather. The Berwick Witch Trials took place for a year beginning in 1591, and it was all due to the inclement weather that beset King James VI after he had sailed to Copenhagen to marry Queen Anne. While the royal couple were sheltering in Norway and waiting on the storms to subside one Danish Admiral, Peder Munk, made mention that high ranking official of Copenhagen’s wife was to blame for their misfortunes. After the suggestion, several nobles of the Scottish court were also accused and confessed to plaguing the voyage of Queen Anne with raging storms and for sending devils to climb up the sides of the ship. More than a hundred of the accused were executed marking this as one of Scotland’s largest witch hunts on record. These events prompted King James to publish his dissertation Daemonologie in 1597, marking the beginning of a secular persecution of witches and conversely inspiring a well-known playwright.

Shortly after the publication of Daemonologie, and the execution of the Pappenheimer’s, the famous English witch trials known as the Pendle Witches[6] (part of a larger series of trials known to history as The Lancashire Trials) took place in 1612. These trials are some of the best kept records of the executions taking place in the 17th century. We know that these trials led to the execution of around 10 people (two were sons of the accused), and although these numbers seem inconsequential when compared to the thousands who perished in Germany, it actually made up a significant portion of executions that took place in England where it’s estimated that the combined executions during this era were fewer than 500. Inspiration for the witch hunt that accused 11 people, included an instance where an unfortunate series of events involving Elizabeth Southerns and her granddaughter Alizon Device. Elizabeth also went by the alias Elizabeth Demdike which was a title derived from “demon woman,” and she was commonly believed to have been a witch by her neighbors for around fifty years prior to the Pendle trials. Her granddaughter, Alizon, one day had the misfortune of running across a beggar selling pins that had an ill-timed stroke after refusing to sell her his products. Pins were often handmade and expensive, and although considered a fairly common item, could also be used for magical purposes including divination, healing, and love magic. The beggar, John Law, was left lame and stiff with a permanent distortion of his face, and subsequently almost the entire Device family, including Elizabeth Southerns now in her mid-eighties, was put on trial for witchcraft.

Next we have a rather large historical event that took place, known as the Thirty Years’ War, and I don’t want to spend a lot time on that subject, so I’ll hit the highlights. It took place mostly in Central Europe from 1618-1648, and it is known as one of the most destructive wars in human history. During this time, we see somewhere around eight million casualties due to human violence, war, plague, and famine and a twenty percent loss of Germany’s total population on par with the casualties that it faced in WWII. We can also see witch-hunting efforts exaggerated by the raging war between most of Europe, and consequently some of our largest casualties from the following executions. Two of the four largest executions of witches in the Early Modern Period (1500-1800) took place during these thirty years of chaos and they resulted in fatalities numbering in the thousands.

[1] Though, we do see an execution a few years earlier in a region of Italy that mirrors the scope of the trials in Weisensteig, it is not as well documented and I thought, for brevity’s sake it would be best if I left it out.

[2] You’re not special, Wiesensteig.

[3] Not the band, that’s a different kind of sabbath.

[4] Remember Switzerland where those other crazy trials started? Me too.

[5] (Unknown, 1600, pp. 1-10)

[6] The Lancashire Trials consisted of the Pendle witches and the Salemsbury witches among other hunts in the area.

#witches#witch trials#european witch trials#early modern period#history#itshistoryyall#plague#thirty years war#covid-19#coronavirus#social distancing#blog#blog post#history blog

1 note

·

View note

Text

Part Three: Rule of Three

Photo Credits: here

In this next part I want to talk a little about some important texts for the context of this project. One of them is the Canon Episcopi, a 10th century medieval canon law. For anyone who doesn’t know what “canon law” is, it is basically a written guideline authored by some church authorities and used to govern the church, its clergy, and its patrons. It’s important to highlight this text because it gives us a clear idea of what surviving pagan cultures looked like in Medieval Francia (modern France), but not in the way you might expect. As mentioned above, a lot of what we know about the past is just really good detective work, and this is one of the instances where a document helps us understand far more than what was originally intended. It’s a cohesive set of ideas that suggest how the church should treat several circumstances regarding their local pagans, and as usual, it wasn’t preaching tolerance. In summation, it called anyone who believed in anything other than Christianity an infidel.[1] Pagans still existed, and still do to this day, in fact, but the Church used a heavy hand when dealing with them most of the time. Often, they used their own beliefs against them and merged popular Christian anecdotes to help assuage people who were not happy with the idea of conversion to a new religion. I think that the author of the overview for this document said it best when they said that,

“new Christians [did not] simply cast aside old beliefs…conversion was a dynamic process…[and] elements of indigenous religious practice were frequently mixed, often deliberately, with Christian belief and ritual…Certain practices can be said to have ‘survived’ the process of conversion…After all, nearly every Christian ritual had some sort of pre-Christian antecedent or model.”[2]

They just simply couldn’t kill them all or threaten everyone with violence in order to bring them to their knees before the Lord, and so, they got creative.

Canon Episcopi calls anyone who believes in the mystical arts a liar and, what I’m most interested in is it’s mention of, “wicked women, who have given themselves back to Satan…[who] in the hours of the night…fly over vast spaces of earth.”[3] You just can’t get more witchy than that folks, and don’t worry, I know that this was written in like 900CE, but I should also mention that it was referenced in another important document—Corpus Juris Cononici, a canonical law that remained intact beginning in the 12th century all the way until 1917. I’m not going to attempt the math there, but it’s too damn long and we can all agree on that. So, now we know our Collective Catholic Opinion (CCO for the rest of this project),[4] is that we don’t like pagans, and with the introduction of this new text, witchcraft is now a pagan practice. This was originally, a really good detail to hammer out in canonical law because it typically kept the Inquisition from meddling in matters of alternative religions, UNTIL (you knew that was coming, I already warned you in Part 1) Canon Episcopi was thrown out by Pope Innocent VIII in 1484 (not the same Innocent One as before, but damn did we not learn a lesson?). Anyway, the most innocent pope of all time decided that witchcraft was to be forever tantamount to devil worship which was what gave inquisitors permission to go after pagans and those accused of practicing witchcraft—great.[5]

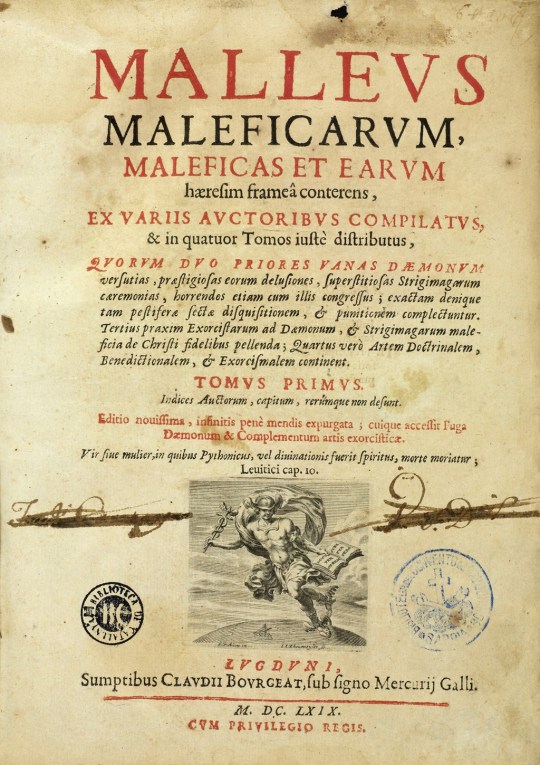

So, that brings me to my next document of importance, the Malleus Maleficarum, the Latin here, in case you aren’t a weird Disney fan, is where we get the word ‘maleficent’ and thus the name for one “Mistress of Evil”…moving on.[6] This book was written between 1486 and 1487 and can also be referred to as “The Hammer of Witches,” a direct translation of the original Latin. It was written by some German Dominican monks—'Dominican’ here, refers to the Dominican order of Preachers founded in France by the Spanish priest St. Dominic, so, not the islanders as I was originally very confused about. Recall from earlier that the first instances we see of witch trials occur in a German-speaking part of Switzerland, so you can see how this thing is gaining speed. There were other texts along the way that were written in regards to witchcraft, but there was a really important invention that made this one unique—the printing press. It spread like wildfire, and there were more copies of this document than any other, and it so precisely aligned with the mounting witch-craze, the Inquisition, and the Corpus Juris Cononici, that it almost seems planned. Am I a conspiracy theorist, you ask? Maybe. After researching this project, I’m beginning to wonder, myself. Let’s indulge.

In 1481 Pope Innocent VIII (I’m so surprised), heard about those German monks who were in the middle of writing about these witches, and they complained to him that the authorities weren’t properly looking into the accusations. This actually prompted the Pope to issue one of those papal bulls we all know and love, titled, Summus Desiderantes Affectibus, translated—Desiring with Supreme Ardor. It wastes no time getting right to the point, those who were practicing witchcraft were to be henceforth considered heretics, and doling out the full support of the Church and the Faith to inquisitors to prosecute these cases as they saw fit. Three years later, the monks published their instruction manual for other sympathizers. This document was separated into three parts. The first was addressing skeptics and assuring them of the reality of the situation and suggesting that not believing in the existence of witchcraft was another form of heresy. The second part included proof that real harm was caused by magic, and the third part was made up of guidelines for investigating, arresting, and punishing witches. It was used by Catholics and Protestants alike, and while it was never made official by the Catholic Church, it was most assuredly referenced. It was not continuously in print; however, but was re-printed and widely distributed in areas “as needed,” meaning that when prosecutions started ramping up in some areas, the press would begin to print and distribute more.

I’m gonna delve pretty deep into this document because it’s really important that we know where some of this information comes from in reference to future prosecutions, tortures, and accusations of presumed witches. The manual directly mentions that witchcraft is found amongst women most predominantly and uses the idea that both good and evil manifests in women more powerfully than in men. It specifically singles out midwives because of their aptitude for contraception and pregnancy termination—see, you guys thought this anti-abortion culture was new…it’s not. It made wild claims that midwives ate babies, or offered them to devils, and elucidated pacts made with the Devil, sex with incubi, possession, and, I’m not quite sure how to word this, the act of vanishing penises (That’s the best I can do here. I tried some other stuff and believe me it was much worse). The part I love most is that most of the references used to substantiate these claims come from some of the great Greek philosophers and writers like Homer and Socrates, who were big, giant, probably gay,[7] pagans. I can’t love that more, guys…it really doesn’t get better than two homophobic, misogynistic, intolerant religious zealots getting their entire bibliography from some gay pagans. Finally, what the document describes as “quarrelsome women” could not be considered witnesses to witchcraft, and it excuses this by alleging that this is to prevent friends, families, and neighbors from bitter fights.

To determine whether or not someone was a witch, they could be examined physically. Any corporeal evidence might include marks on the body, physical objects that were concealed on the body, or not weeping while being tortured or when presented in front of a judge. When checking for these “marks,” women were stripped of their clothing (by other women), their hair was shaved—this could be a small amount or all of it depending on where that pesky devil’s mark was going to be found. Often, this mark could be a mole, a flea or insect bite, a birth mark, or a speck of dirt. Anything passed, really, and once these marks were found they needed to make sure that there were no other instruments of witchcraft on a person in order to execute them. The manuscript mentions that if these items are not removed, there would be an inability to burn or drown the witch, and the same goes for if she was still under the protection of other witches. The practice of drowning or burning an accused witch to prove her innocence began, and although the accused was never around to celebrate her liberation afterwards the practice persisted, nonetheless. While determining the guilt of these witches, a confession was paramount in determining the outcome of a person’s wellbeing after the trial.

Accused witches could only be executed by the inquisitors or authorities of the church if they confessed themselves, but, remember that the church had already authorized torture as an acceptable method of questioning at this point and could be persuaded into confessing by any means necessary. Often, they would confess quickly under the pain of torture, and were said to have been abandoned by the Devil. Conversely, those who held out, were under the Devil’s protection and more closely bound to him, and torture was viewed as a form of exorcism. Confession under torture was not enough; however, and they had to confess again while not being tortured for it to be a valid confession. If the accused continuously denied the accusations the church was not permitted to execute her, but they could eventually turn her in to local authorities who were not beholden to the same restrictions.

After a confession, the accused could be offered the option of repenting against all prior acts of heresy and perhaps be granted the avoidance of a death sentence, but later when I pull out the statistics, you’ll see precisely how rare that option was. They were also likely to allow a witch to avoid a death sentence if they snitched on other witches, but typically the investigations into those that were implicated by the original witch were presumed to be innocent until a thorough investigation could take place. Prosecutors also did not have to reveal that the removal of a death sentence did not mean that they could not imprison them indefinitely. Judges that presided over these trials were given specific instructions on how to ward themselves from wayward spells of the spurned witches on trial, and to ensure that they had the full cooperation of those amongst the court and spectators, there were specific instructions that allowed those who were uncooperative to be excommunicated from the church or even labeled heretics themselves if their obstruction was persistent.

Pope Innocent VIII’s bull acted as a metaphorical magnifying glass over the ant that this situation was in Switzerland and Germany, but to conflagrate things further, in 1501, Pope Alexander VI[8] issued a new papal bull, the Cum Acceperimus,[9]that extended the reach of prosecutions for witches to Lombardy and officially broadening the reach into Italy. I think it’s important to point out that this particular pope was a Borgia, and for those of you who haven’t seen The Borgias on Showtime, the Borgia family is basically the Kardashian/Jenners of the Medieval world—so many scandals and orgies, one can nary keep up. Beginning in 1500 and all the way through 1560, historians consider these few decades to be the peak of trials in Europe, and in order to focus more in-depth on this aspect we’ll be ending this part here, but it may be worth mentioning that this oddly severe belief in superstition beginning with the Malleus Maleficarum, may have been one of the many sparks that stoke the flames of the Protestant Reformation in Europe.[10]

[1] See Canon Episcopi for a full quote, but this is in direct reference to a bible verse from John 1:3 that makes mention of God being the maker of all things and suggests that those who believe that other entities may have done so are “infidels.”

[2] (Traces of Non-Christian Religious Practices in Medieval Pentitentials, n.d.)

[3] Direct quote from the Canon Episcopi and shortened for clarity and pointed reference.

[4] Please don’t talk to normal people about the CCO, it’s not a real organization, and outside of this context it’s probably very offensive to modern Catholic practitioners and I am not looking to get cancelled on Twitter

[5] (encyclopedia.com, 2019)

[6] Maleficent is defined by Webster’s as, “doing evil or harm; harmfully malicious,” and the original Latin form is maleficentia.

[7] the ancient Greeks were partiers and lovers, man

[8] Not a safer name than ‘Innocent,’ it turns out.

[9] DON’T YOU DARE GIGGLE AT THAT NAME

[10] It’s important to note here that history doesn’t have a large grasp on one specific event that might have been what caused this leap, but it was more likely a combination of quite a few different things, but it is my own humble opinion that torturing people certainly wasn’t a good way to rally support for the Catholic Cause™

#witch#witches#witch trials#european witch trials#malleus maleficarum#pope alexander vi#historical texts#history#itshistoryyall#coronavirus#covid-19#quarantine#social distancing#pandemic#2020

0 notes

Text

Part Two: Well, We’re Here Now

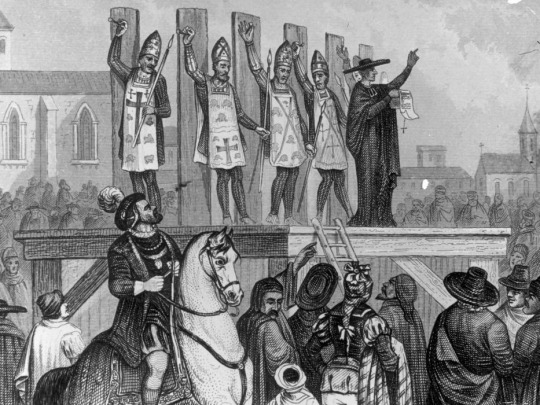

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Here, we have to start with what we can recognize as a proverbial snowball rolling down a hill. Essentially, we have the Catholic church establishing a precedent for getting rid of people who were problematic for them by placing some trumped up charges on them, executing them in a way that makes an example for others whilst simultaneously encapsulating the attention of the commoners, and then carrying on as if they had every justification for making a scene like your mom at a restaurant when they bring out the food and it’s cooler than expected. You can only imagine the out of control spiral into unadulterated chaos that followed, and that, my friends, is known to history as the European Witch Trials (ßthe snowball that is now much larger than when it began rolling at the top of that hill). A few quick notes before we power through this—at this time we can see a multitude of “assassination conspiracies” popping up against one king or another, against the Pope, or against high ranking church officials/the nobility. A bishop is executed for heresy and attempted assassination of Pope John XXII via sorcery, others were arrested with similar charges attached to the very public executions, and ultimately you start to see sorcery, idolatry, and heresy all becoming somewhat synonymous. A few decades later, as we near the central part of the 1300’s, we see the Black Death beginning to rear its ugly head and as fears, tensions, and misinformation mount, people start seeing conspiracies everywhere they look. In 1340 when people start getting grossly sick and some inquisitions start popping up. Spearheaded by the Church, the united heresy combat forces (henceforth known as UHCF—I just came up with that it’s not, like, a term historians use) went out and, as Jesus commanded,

“Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, 20 and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you…” Matthew 28:19-20 (King James Version).

You know what that means (*insert eyebrow waggle here*), of course, they set out to rid the world of anything deemed “heresy” by the Church and that, most certainly, was up for personal interpretation. The reason we hear about these inquisitions getting such a bad rap is because people were genuinely afraid that any action they took might be mistaken for heresy, and without a clear definition of what that entailed they were most certainly right to be afraid. It’s important to highlight a bit of “Inquisition Era” timeline here—in and around 1100 the Catholic Church had, by its own definitions, all but eliminated heresy (whatever that actually means, we may never know), and they did so predominately without harm to those who stood accused. This “era of peace,” we’ll call it, ended around the 12th century when we start to see a spread of some opposing Christian ideas that were not specifically Catholic, and that couldn’t be tolerated. To nip that in the bud, we had some inquisitions come around checking things out. This process usually included, but was not limited to questioning, interrogation, arrest, imprisonment, and torture.

As a general rule, torture was, at least, publicly frowned on in Europe while other countries typically had a death sentence for heretics. As previously mentioned, in the 12th century that all changed when a tiny little papal bull, similar to a public decree, was issued by the not-at-all ironically christened Pope Innocent IV (I, quite frankly, can NOT believe that there were three others prior to this pope who were also called “Innocent” it’s just so god damn pretentious that it physically makes my skin crawl…I digress). The bull allowed torture in 1252, and by 1256 inquisitors who used this form of extracting information were promised absolution by the Church. So, to recap, we have this widespread knowledge of public executions of some of the most prominent figures in the medieval world (like that one guy in charge of the Knights Templar that predicted the deaths of a king and a pope in a non-awkward way that had no bearing on whether or not people believed in the supernatural, I’m sure), the establishment of an anti-heretic police force with little to no oversight and the ability to torture folks at will, and panicked people afraid that if the plague didn’t take them the inquisitors surely would.

To make matters worse, a new papal bull (pesky, those public decrees, I’ll tell ya..) issued around 1450 verified that witchcraft, heresy and a religious group called the Cathars were one in the same which gave them license to prosecute them as heretics or witches without just cause. Without going into too much detail about this, it’s important for you to know that the Cathars called themselves, “the good Christians,” and celebrated a twin deities that represented the God portrayed in the Old Testament, and the other represented the God of Judaism who was a bit synonymous with Satan, or either fathered, seduced, or created Satan (it’s a bit confusing, but that’s what happens when intolerant Christians try and convert believers of other religions to Christianity by way of removing what they originally believed and then replacing it with a more favorable and sort of similar Christian Approved™ bible story—i.e. pagan Ireland, Scotland, or literally any pagan religion in history). You should also know, Cathars essentially saw gender as meaningless and believed in the idea of reincarnation between genders which rendered normal gender roles and other “gender exclusive ideas” as basically useless to them. You can draw your own conclusions about why a male-dominated medieval world run by a religion known for its historical mistreatment of women, wouldn’t have received this idea well.

To reign this all in a bit, we’ve only moved a few centuries away from the establishment of Thomas Aquinas’ rules when we hit a milestone in the 15th century. Occasionally, the Church holds councils to decide on, debate, or discuss church matters, and one such event took place from 1431-1437 called the Council of Basel. Some historians suggest that while a bunch of old men were sitting together talking about stuff for six years that they may have gossiped amongst themselves (as silly men are want to do), and that this may explain the correlating witch trials that coincided with these same dates. It is only about 300 miles from where the council was held and the location of the first trial so you can see how this conclusion is easily drawn. AND NOW WITHOUT FURTHER ADO, it’s time to talk about our first round of witch trials.

The Valais witch trials named so because of its location in Valais in one of the oldest ecclesiastical territories that lies in the southern part of the country separating the Pennine Alps and the Bernese Alps. This region was French and German speaking and that’s important because the German word for witch is hexen, which is where we get the idea of a witch’s hex today, and although we can see an occasional and sporadic burning of witches throughout the 15th century, this marked the first time we see a large-scale systematic persecution for peoples accused of witchcraft/sorcery. It’s also important to point out the lack of accounts that we have during this time period, in part this is due to a general hatred for inquisitors who were in charge of keeping records, and later when the accusations included less heresy and more witchcraft we often see occasions of inquisitors being attacked and records being sabotaged or altogether destroyed. Don’t get me wrong, I can’t blame them, but it makes this part of history a bit more difficult to sus out, and a lot left up to really good detective work or wherever your imagination can take you (this is basically my favorite part). So, that was a long-winded way of saying, a lot of this next part is gonna be me doing my best to make this make sense, and to draw concise and enlightening conclusions that you can read and hopefully learn from (I know I am!).

So, what do we know here? We know that the main record of these trials comes from a guy named Johannes Fründ of Lucerne who was a Swiss clerk of the court, and his account is thought to be the, I won’t say accurate, but more likely only usable document to have an account of these events, though, severely lacking as they were written in the middle of the trials and with only 17 years before they ended. The trials began in the southern French-speaking part of Valais and then spread to the northern German-speaking part where we see a following expansion into the French and Swiss Alps, Savoy, and further into the valleys of Switzerland. It took place a solid fifty years before the witch trials started in Europe, and while the total number of victims is still unknown to us, the estimated death toll is an estimated 400 total men and women. When these accusations began to take place, the duchy of Savoy was recovering from a tumultuous civil war between the noble clans, and in August of 1428, seven delegates representing the districts in Valais insisted that the authorities investigate some supposed instances of witchcraft. If three or more people accused someone of witchcraft or sorcery they were to be arrested, questioned, and made to confess. At a time when torture practices were acceptable forms of interrogation you can see how that might have inspired a few people to confess to being witches without much prompting, but those who refused to do so were tortured until they did. What we know about the victims is that they were more likely women than men, but a significant portion of men were also executed, they were all peasants that were not specifically described as well-educated, but some were. Very few of their names were recorded, and they were not likely elderly as most of them withstood immense torture before they died.

The victims were accused of quite an array of magical experiences including flying, invisibility, removing an illness from one person and issuing it to another, curses, lycanthropy, conspiracy to deprive Christianity of its power, and the most famously known, conspiring with the Devil. These pacts that the witches supposedly entered into with the Devil included trading their souls, paying him taxes, renouncing Christianity, and halting all confession or church-going in exchange for supernatural abilities or an education in the magical arts. Those accused of these crimes were tied to a ladder with a bag of gunpowder hung around their necks, and a wooden crucifix in their arms and then burned alive, others were decapitated first, and even more were tortured to death but were nonetheless burned at the stake for good measure. Now here is where we can see a bit of a conspiracy emerge. Recall from earlier, my mentioning that clergy and nobles alike used witchcraft as an excuse to get rid of people, and just ruminate on that as I tell you that the property of these deceased and accused only passed to their families if they could swear that they were unaware of the sorcery. If they could not prove that, then the land passed to the noble who paid for the execution of these accused. I don’t know about you, but sounds sus to me. This particular genocide is unique to other witch trials in that almost as many men were executed as women, and that leads me to believe a few things: first, that the men were landowners and the nobility wanted the land they were on (would love if a map was available to see this progression, but alas, it has been lost to the sands of time), and two, this wasn’t about gender, but more about the crybaby nobles who were upset that they lost some things during the recent civil war and needed a hobby. It’s not a good look, and it certainly wasn’t without its consequences.

#witches#witch trials#inquisition#medieval europe#itshistoryyall#history#valais#switzerland#valais witch trials#part two#covid-19#coronavirus#what day is it#social distancing

0 notes

Text

Part 1: Blame the Church

Photo Credits: Saul and the Witch of Endor, 1526. Artist: Cornelisz van Oostsanen, Jacob (ca. 1470-1533). Heritage Images/Getty Images / Getty Images

I think it’s always best for any research project to start with the basics, so let’s talk about what our timeline looks like. Beginning in the 14th century we start to see an occasion or two of sentencing for the crime of, or allusions to the crime of, witchcraft. However, we need to look much further back in history to fully recognize how we arrived at the folly of trails and executions for the non-existent crime of witchcraft.[1] This all starts with Christianity, and I know how that sounds, but let’s be clear, the practice of Christianity isn’t to blame here, it’s the interpretation of the believers that are to blame. Allow me to elaborate—The bible has (according to my quick CTRL+F search of the word in the digitized King James Version) eleven brief mentions of the word ‘witch,’ throughout the testaments, and several other mentions of “familiar souls,” sorcery, magic, etc. Fairly few occurrences as far as main subject matters go, and especially when considering the breadth and quantity of material we’re presented with here.

My assumption can only be that believers and those in charge of informing the believers (read: clergymen), were given very little content information to go on as far as witches were concerned, and were therefore forced to really loosely interpret what it meant to be a witch and what to do when one came into contact with, noticed the existence of, or were afflicted by a practitioner of the arts. The earliest mention of sorcery in the Bible is in Leviticus 19:31 where it mentions God not wanting his followers seeking out sorcerers or for them to be “defiled,” by them.[2] One interpretation of this verse in layman’s terms is that one should be careful of partaking in the services of magicians (or those claiming to be such) because it’s likely that they aren’t performing real magic, and there’s a high likelihood of being scammed or, “defiled,” as it were. Without delving too far into the many ways that a 12th or 13th century member of the clergy could have potentially decided what any of this meant for Christ’s followers, I’ll say this, it is very likely that these Old Testament references to magics were used frequently as a means of getting rid of a person or two without too much backlash from the common onlooker. It’s most important to remember that throughout the medieval time period we can see that most of the Christian doctrine was leaning towards a common disbelief in this whole magic or witches business until (and this is History, so you know there’s always an, “until…” ), around the 13th century where we see the development of this idea that a person could collude with the devil or demons in order to obtain certain benefits. The person most likely at fault for this ideological shift is Thomas Aquinas, who is one of the most influential theologians in the history of the Catholic church, and single-handedly changed how Catholic doctrine was interpreted forever. He introduced the idea that God was the only entity that could perform magic, and that those who claimed to be performing magic were, in essence, delusional.

With Aquinas’ work Summa contra Gentiles, he established many of the guidelines that modern Christianity operates upon today such as the idea of a “Just War,” and , and certainly for the next few centuries that will be discussed here in further detail. As we reach the 1200s, we start to see a general inquisition established by the Catholic church. The general purpose of this was to combat overall heresy, and in 1233, the Dominican Inquisition was established as a new branch to perform that sacred duty. At this time things were starting to heat up, not for witches specifically, but for those who were not believers of The Faith™. We start to see at this time, people being asked to convert or leave their countries, an adversely effected Jewish and Moorish population, and at the very essence of this, your store-brand religious intolerance for any country under the thumb of the Catholic church. Following right along with the innumerable blunders that were kindling for this fire, in the early parts of the 1300’s the church moved to disband the Knights Templar at the behest of one King Phillip whose motivations were likely spurred by the massive debt he owed to them from his war with the English. Some say that his order for the arrest of the Templars is where our superstitious legend of Friday the 13th originates. This one took place in 1307. In March of 1314, the Grand Master and Perceptor of the Templar were executed by being burned at the stake. Through the flames, Grand Master Jacques de Molay prophesized that the King and Pope (those responsible for his demise) would soon meet a similar fate, and within the year both had perished.

By the 14th century we also have our first accused sorcerer imprisoned by an inquisitor, and here is where we can finally begin sum up what’s been brewing, if you will, for centuries. Starting with witchcraft’s mention in biblical texts, we have this mass of unknown details about the inferred existence of witches and the practice of magic, but the subject, lacking both quantity of content information and quality of information present, was left to be determined by the scholars of the church and its clergy members. Proceeding without a system in order to check for accuracy, personal motivations, or conflicts of interest, we left these prestigious members of society to be the final word in how we manage all issues that may be open to further interpretation. It’s nothing new for humans to create an, “us vs. them,” culture and to then persecute those who are not among the “us,” and this topic is no different in its basest interpretation. The part that’s so interesting is the journey from steadfast disbelief in the idea of something that was once so generally accepted, to the unquestionable conquest to rid the earth of that concept and its very existence. Or perhaps, the simple refusal to look the truth in the face was what made this historical oddity so alluring? Either way, the build up to this event was by and large, the fault of the church and its clergy.

[1] That’s not to say here that pagan practices, or the act of practicing Wicca or other similar religious/spiritual practices don’t take place now, or didn’t take place at this point in history. As we get further into this topic you will see that some practices were indeed synonymous with witchcraft for many at the time, and most certainly were contributions to the mass hysteria that surrounded this phenomenon.

[2] See the Bible for the full quote.

#witch#witches#witch trials#itshistoryyall#history#where it all began#how did we get here#when did it start#why#european witch trials

0 notes

Text

I’m just casually going to post a multi-part project on witch trial while we’re all here.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pandemics

The history of pandemics is, as I’m sure you can surmise, quite extensive. As far back as the history of humanity goes, pandemics, disease, and death has kept close proximity. We have always faced hardships, but the intriguing part, is how we have survived. It’s important to remember that during these tough times where it seems like we might be isolated, afraid, or scared. We, as a community, have always persevered, and this time is no different. We will pull-through, we will move forward, and we will survive. BUT, it’s very important that we start by passing on good, researched information, help out our neighbors, and keep in mind that this situation is above all, NOT about you.

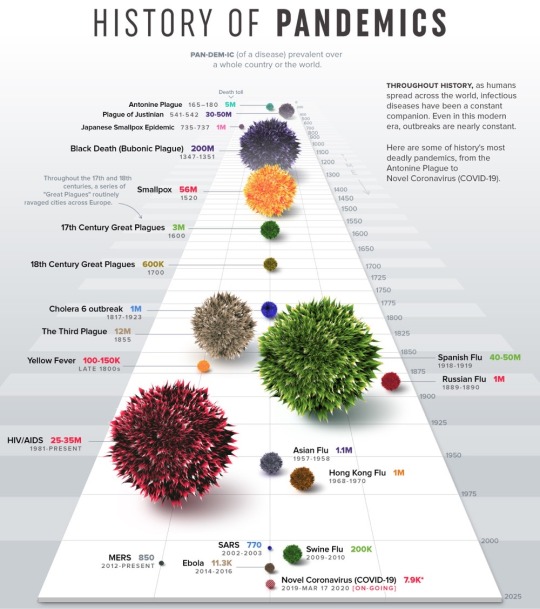

Beginning in the 1300s with the bubonic plague, humanity started seeing an organized effort to quell emerging diseases. At first glance, I would be want to say that we, as modern humans, have not experienced a pandemic threat on this particular level, but that would not be entirely true. It’s more like true, but with an asterisk--more on that in a minute (I’ll be sure to put an asterisk so you know). The plague, I won’t spend too much time on because it could in it’s own right be an entire series of posts, but what’s important to know is that this is where we, as humans, assessed a threat and decided that there should be some sort of concerted effort to suss out tactics to stop its progression. So, we won’t talk about how it spread here, but more specifically about statistics. It is estimated that around 30-60% of the world’s population was decimated by “the black death,” and to put that in numbers, an of an estimated 475 million people, around 350-375 million were left at the start of the 14th century.

It’s important not to blame the animals for the spread of the plague though, they may have started it, but uninformed humans made it the pandemic that it was (three times in history, I might add). The plague was thought to have been potentially airborne and close contact mixed with poor health conditions, malnutrition, and a general lack of knowledge for personal hygiene and the healthcare practices that we have today were simply a recipe for disaster. This disease spread rapidly from person to person, and ended up taking out over half of Europe’s population. It seems like a silly thing to compare that to what’s happening in our current day situation, but I would like to draw the parallel of what dangers an uninformed public can pose. The idea of quarantine began here in 1377, and though it was the right decision, the spread of the disease was not halted because of a lack of modern medical knowledge.

We don’t see a real protocol for quarantine until the mid 1600s when England passed a number of bills that standardized the process for disinfecting and cleaning people and ships suspected of being infected with the plague. Around this time, cases of smallpox and yellow fever were starting to pop up in America, and the implementation of regulations for dealing with the spread of disease was the responsibility of the state. We didn’t see national involvement in disease prevention until the late 1700s. If you’d like to know how old news anti-vaccers are, then you can look back to the beginnings of inoculations for smallpox that began in the late 1600s around 1691. It was highly controversial to inoculate people and was more acceptable to mandate a quarantine for those suspected of having the disease.

When cholera began spreading across the world in the 18th century, quarantine practices were also scoffed at and for the most part considered unnecessary by most people. The resulting spread was exponential. The death rate was well over 1 million people and plenty of others had contracted cholera before the pandemic calmed down around 6 years after the initial outbreak thanks to a literal act of God, meaning, a severely cold winter killed off most of the mosquitoes that were carrying and transmitting cholera to humans and worsening the impact and spread. By the early 1900s an international Sanitary Conference was held where new articles were signed that reinvented methods of prevention of the spread of disease, and it couldn’t have come soon enough because a few years later (7 to be exact), a tremendous influenza epidemic hit the world hard. Known as Spanish Influenza, the world’s first introduction to the flu was not a pleasant experience.

The influenza pandemic came in three waves between 1918-1919, and was a disease that was completely unknown to professionals. The Office International d’Hygiène Publique (predecessor of the World Health Organization or WHO), located in Paris, France was all but useless in the immediate need for action to stop the spread of flu. As the world was suffering at the throes of the First World War, too little and too late was done to prevent the spread, but to no avail. Attempts were made to close public gathering places, schools, sporting events, and entertainment venues. Even Yale closed all on-campus meetings, but the extremely contagious virus was too widely spread for these uncoordinated and poorly-timed measures to prevent mass spread. Here we see the efforts of health experts encouraging people to self-quarantine and use social distancing measures, but by the time this was implemented, influenza had reached every part of the world and had progressed to a point where these measures were all but useless. What’s important about this history lesson is that these things would have helped had they been a preventative measure.

Influenza is unique in this time period because we also have our first instance of the impact that mass media would have on the outcome and public information about this virus. In Italy, newspapers were prevented from publishing the death count on a daily basis in order to keep the mass acute anxiety that was having an extreme impact on public morale and panic levels. However, war-torn nations were experiencing problems with accuracy and clarity of information regarding prevention of spread because of the censorship of media outlets at the time which worsened the impact of the pandemic as much as the war effort itself.

In 1933 the pathogen that causes influenza was found and we were able to start treating influenza, and creating a vaccine. Around 1940, the CDC was founded and established in Atlanta, Georgia as a base for all operations regarding the control and prevention of the spread of infectious diseases, and it was in direct relation to the spread of malaria in the 1940s. The CDC added a plague department in 1947 as well as an Epidemiology Division and Veterinary Diseases Division. In 1951, the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) and Field Epidemiology Training Programs (FETP) were established that now have international models based off of the American programs. The Venereal Disease Division was establishes in 1957, and in 1963 the Immunization program was established. The CDC has been widely influential in a number of preventative and creative approaches to preventing the spread of disease and abuse of medications in order to prevent immunity of viruses and bacteria to treatment. This organization is a world leader when it comes to establishing standards for handling anything from research to protocols for worldwide pandemics. If there was ever a time to trust the nerds it’s now.

And that brings us to today. So, what are we supposed to be listening to now? The professionals. The ones who have brought us from malaria to COVID-19, the place that has kept us informed about influenza since 1946, and the place that is the ONLY reason that penicillin still works as an antibiotic, the one-and-only, Center for Disease Control. This virus and its prevention has suffered from a large amount of disinformation and “fake news.” I would like to encourage everyone to take power over your own learning, to learn from the unintelligent and unfortunate dead, and to re-post only articles and information that you know to be true. Now, more than ever before is a time to learn from our own naive history, to realize that we have made these mistakes before, and to LISTEN to the pleas of our healthcare experts and government officials. These measures might seem superfluous, but they’re preventative and we need this virus to slow down or face the consequences a la Cholera. This is not something to not take seriously and now is not the time to be selfish. Help your fellow man. Stay home, even if you’re well, and remember that you’re saving lives--you hero, you ;)

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”--George Santayana

https://www.cdc.gov/

#CDC#history#itshistoryyall#disease#corona virus#covid 19#infectious diseases#center for disease control

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

how big do yoou think caster fionn can make his house? like giant sized? what rank of territory creation would that be?

Fionn’s home was the Hill of Allen which is a volcanic hill west of County Kildare, and whose highest point is at 676 feet so his house would beeee pretty fucking big! Here’s some pics of it

During the construction of the tower on the Hill in 1859-1863 a large coffin containing human bones was found buried here and they are thought to be the bones of Fionn himself, so they were reburied

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I thought now might be a good time to share this visual representation of historical pandemics.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

St. Patrick & Ireland

Obviously, I was inspired with St. Patrick’s Day being yesterday, so I’ve decided to post about the wormhole of Irish folklore that I went down in my spare time yesterday.

Without further ado--here’s what I learned about St. Patrick:

As far as Sainthood goes, he IS an official Saint of Ireland. Little is known about the actual year of birth for Patrick, and there’s even debate on when he died. What we can ascertain from his writings is that he existed sometime in the second half of the 5th century meaning, around 450AD...ish. We know this because he made references in his writings to the, “heathen Franks,” meaning, unbaptized. We can date the Frankish baptism back to 496AD, so we can reasonably say that he was born sometime before that date, and was old enough to know that they were unbaptized up until that point. Patrick was born into a Romanized family that resided in Britain--meaning they were, at that time, citizens of the Roman Empire. He was kidnapped at some point by Irish raiders and sold into slavery. Since his father was a deacon, he at this point, leaned heavily on his religious upbringing to carry him through these troubling times. He eventually escaped, reunited with his family, and then supposedly paid a short visit to the Continent (which is the continental Europe, not including Britain or Ireland which are islands).

He is best known for his work the Confessio where he wrote, in a diary style format, a personal account of his life. In one passage, he mentions someone called Victoricus delivering a letter, The Voice of the Irish, that encouraged him to return to Ireland. After some hesitation at the state of his educational qualifications, he eventually conceded and returned to Ireland to start his new career baptizing, converting, and journeying far and wide to do the Lord’s work.

To sum up, he was an old school missionary that was converting pagans in Ireland to Christianity. He claims that he was the first person to Evangelize “heathen” Ireland, but it was more likely the work of Palladius, a bishop sent by Pope Celestine I to baptize the Franks en masse. However unlikely his own claims are, he had regardless achieved a legendary status by the 7th century. Some commonly associated legends include driving all of the snakes from Ireland into the sea where they met their demise, raising an alleged thirty-three people from the dead (some of whom had been dead for quite some time), praying for food for sailors passing through a desolate area when a herd of swine “appeared,” and last, but most common, the use of the shamrock as a religious teaching tool. He supposedly used the three leaves of the shamrock to represent the holy trinity(three leaves for the father, son, and holy spirit on one stalk).

There is lots of speculation as to why we associate the shamrock with St. Patrick’s Day. Basically the consensus is that it was a huge misconception about the importance of the plant to the Irish. Irish folklore is riddled with talks of druids, nature, earth, and magic. It is likely that most Irish held the earth and its many flora and fauna with extremely high regard, and perhaps even saw it as sacred. In my opinion, this is why using the shamrock was an extremely effective tool in rousing the interests of the common people, and inspiring pagan believers into Christian practices. The next part of the association comes from the scattered tribes of Ireland and the common observations of outsiders in their normal hunting and gathering practices. Many writers describe the eating habits of the “wild Irish” as having contained shamrocks and clovers (which I have learned are NOT, in fact, interchangeable). Shamrocks have three leaves or flowers, whereas clovers may contain 4 or more leaves. Regardless, neither were known to have been a main source of sustenance, although, they were known to forage and eat quite a wide variety of plants including a similarly looking plant called wood sorrel which is almost unmistakably a shamrock to the untrained eye.

To make a long story of historical telephone short, it was written that these “wild Irish” ate shamrocks, a shamrock was already associated with St. Patrick who had used it to convert pagans, and like humans are likely to do, we saw a shamrock and said that goes with Ireland in our minds and it was forever associated with Ireland. So much so, that it is actually the national symbol of Ireland and is still worn on the lapels of Irish members of the Royal Irish Regiment of the British Armed Forces every St. Patrick’s Day, and fresh shamrocks are exported to wherever the regiment may be stationed throughout the world. The Prime Minister of Ireland, known as the Taoiseach or “chieftan,” also traditionally presents the President of the United States with a unique Waterford crystal bowl shaped like a shamrock and filled fresh shamrocks on every St. Patrick’s Day.

It’s a national day of celebration in Ireland and the best way to celebrate is by “drowning the shamrock,” a traditional salute to Ireland, St. Patrick, and to those present by placing a shamrock at the bottom of a cup and then filling it with whiskey, cider, or beer (be it green or not), and then drinking to a toast. The shamrock is then consumed or tossed over the shoulder for luck. This tradition may be where we associated the shamrock with luck and the Irish people as having luck on their side. If you’ve ever heard the phrase, “the luck of the Irish,” you’ll know that there’s something uncanny about their good fortune, but the phrase actually refers to a time during the 19th century called the Gold Rush. It’s commonly believed that a lot of successful miners were of Irish descent and thus the phrase stuck. Perhaps this is why we also associate the image of the folk character, the leprechaun to this holiday as well.

Leprechauns were known to Irish folklore as fairies that were tinkerers or craftsman and made shoes. One could determine the presence of a leprechaun from the sound of hammering in one’s home or place of business. These creatures were typically distinguished by an old lopsided (often worn or ragged) leather hat, and were small and sometimes invisible. If you were cunning enough to capture a leprechaun, you could threaten it with bodily harm or violence and perhaps convince it to lead you to it’s crock of gold. The catch is that you have to keep your eyes on the little guy the whole time, so often enough these cunning creatures would convince their captors to glance away and then disappear forever without revealing the location of their coveted gold. As you can see, it’s not a far reach to associate a successful gold miner of Irish descent with a creature of legend and mystery. This leads into a much deeper, darker, and less fun side of America’s history and the treatment of its immigrants of various descent, and for this piece, I don’t think we’ll go there. COVID-19 has done enough damage and deep, dark, less fun seems to be its operational slogan.

Stay safe out there, folks!

#history#itshistoryyall#irish history#stpattysday#stpatricksday#ireland#luckoftheirish#shamrocks#folk history#covid-19#corona virus#history lesson#today in history#yesterday in history#late post#green#lucky#christianity#pagan#pagan beliefs#history of christianity#saints#patron saints#pope

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well, Well, Well...

If there’s one thing quarantine has done for me it’s time. TIME FOR NEW HISTORY CONTENT :)

0 notes

Text

Let me introduce you to Anna Comnena! She is considered the first female historian, but she also had MANY other talents. She was born on December 1, 1083, into the Byzantine Empire’s MOST prominent family of the time, the Imperial Family of Komnenos. That’s right, she was a PRINCESS that wrote history books (*so* cool). The important part about her being a princess is that she got a classical education that typically only men received. She was the MOST noble of the nobility and came from a LONG line of imperial descent starting with her mother who was a member of the imperial family of Doukai. Anna makes mention of her lofty credintials in her historical texts stating that she was “born and bred in the purple.” Purple has historically been a significant color for the wealthy, and wearing the color represented a higher status. For example, the Roman Magistrates wore a stripe of purple on their otherwise white togas or robes. It has always been a color of imperial power since the dyes used to create the color were EXTREMELY expensive to reproduce. The color came from a particular sea snail and was used to dye the cloth or clothing item (DEFINITELY not vegan). Since it was so pricey, only the VERY wealthy could afford to wear it. BUT why is that all relevant to Anna? Oh, she was casually born in the biggest, most luxurious room in the whole empire that was, you guessed it, COMPLETELY PURPLE. It was completely built out of purple porphyry which is a type of igneous rock. SO, just to recap, Anna, princess of Byzantine empire, second in line for the throne, born in the most expensive room in EXISTENCE, and hasn’t even started her LIFE yet in 1083 and is ALREADY more qualified than me. @disneyanimation where is her movie tho? Anyway, so she’s born and then betrothed (no there’s no time that passed in between that, she was literally born betrothed to someone) to Constantine Doukas, BUT in a crazy twist of fate, his mother who had basically RAISED Anna tried to de-throne Anna’s dad and then Constantine DIED in 1094 after her baby brother was born so she got married to someone else instead! His name was Nikephoros Bryennios who was a soldier and a historian (those things kind of went hand-in-hand back then). BUT he was really only important because he was believed to have encouraged her intellectual endeavors that led to the writing of her father’s history. Nikephoros was planning to actually write the history books himself, but he died in 1137 and Anna wrote them instead (or at least that’s what she TOLD people). She lived out her days in a convent BECAUSE she felt cheated that her younger brother inherited the throne and together with her mother, plotted to kill her sibling. Since she was almost CERTAINLY involved in many other plots against his claim, she forfeited all of her land and estates. Most scholars believe the main reason for the writing of the 15 volumes of The Alexiad was to emphasize her qualifications and pedigree over her younger brothers in an attempt to shed a better light on her own true claim to the throne.

#history#history lesson#itshistoryyall#anna comnena#byzantines#byzantine empire#historians#womens history month#women in history#historical intellectuals#trailblazers#cool facts#princess#disney

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

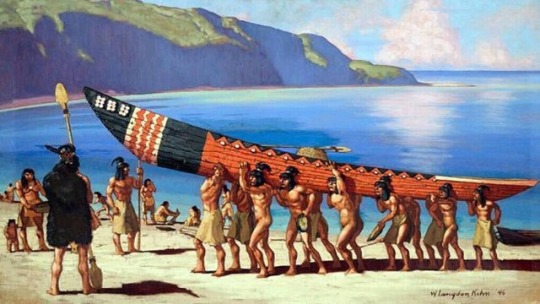

I’m really not good at this whole tumblr thing. New video is up. And really long. Just like this Tomol. Anyway, it turns out I didn’t post my sources. I’ll get it right one of these days. Message me for info on source material! I’ll be glad to send you info on anything you’d like!

undefined

youtube

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey guys! Go check out the new video up on my YouTube channel!

undefined

youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hi guys! Just a little pic hinting at our January topic! It’s a really cool layout of major Native American tribes in America where they were located BEFORE they were forced out of their ancestral homes. Video coming soon!!

#history#history lesson#american history#america#precolonialization#native americans#indigenous tribes#native lands#itshistoryyall

6 notes

·

View notes