Note

hey, just wondering if you take paleoart commissions? no worries if not but I wanted to check, you do such cool art!

Thank you! I don't don't have anything set in stone regarding commissions but I'm willing to take them depending on the request.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Nine-headed hermit": the early history of Zhong Kui (and his sister)

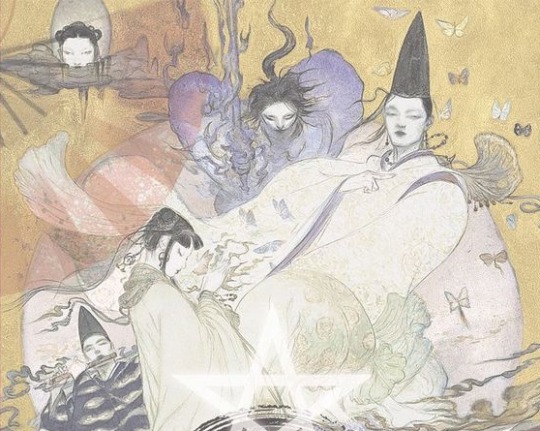

Gong Kai's painting Zhongshan Going on Excursion, showing Zhong Kui, his sister and various demons during a journey (wikimedia commons)

Zhong Kui is probably one of the most recognizable figures from Chinese mythology today and continues to star in novels, movies and other works. However, his modern image largely depends on sources the Ming and Qing periods. In this article, I’ll attempt to instead shed some light on some lesser known aspects of his earlier history. You will be able to learn why he was called a “nine headed hermit” despite having only one head, what he had to do with foxes, when his sister was portrayed as an exorcist like him, and more. As a bonus, I’ve included a brief summary of Zhong Kui’s reception in medieval Japan.

The earliest history of Zhong Kui

Zhong Kui’s history goes all the way back to the Zhou period (most of the first millennium BCE). A homophone of his name (鍾馗), zhongkui (終葵; also zhongzui, 終椎) at the time referred to a type of ritual mallet used to expel demons. During the Six Dynasties period first cases of this term (now written as 鍾馗 ori 鍾葵) being used as a personal name start to pop up. The purpose was most likely to confer the protection granted by such objects to a child just through their name. Numerous cases are attested, and it doesn’t seem the bearers of the moniker Zhong Kui can be distinguished by a specific origin, social class or even gender.

The earliest possible reference to a specific supernatural being named Zhong Kui comes from the Taishang Dongyuan Shenzhou Jing (太上洞淵神咒經; “Scripture of the Divine Incantations of the Abyssal Caverns of the Most High”), a Daoist work possibly composed as early as in the fourth century. The oldest surviving copy of the passage concerning Zhong Kui has been identified in a copy from Dunhuang dated to 664. He appears in it as an assistant of king Wu of Zhou and Confucius (sic) who helps them subjugate ghosts and disease demons.

It is not impossible that to the compilers of Taishang Dongyuan Shenzhou Jing Zhong Kui was only a stand-in for an exorcist, though, not a single well defined figure. There’s an eyewitness account of such specialists dressing up in leopard skins, painting their faces red and announcing they are Zhong Kui in another, slightly newer Dunhuang text. It specifies that many Zhong Kui exist, and that they answer to the “General of Five Paths”, an originally apocryphal Buddhist figure eventually canonized as one of the kings of hell (you can find an excellent article about him here).

In any case, regardless of the clear evidence for ambiguous use of the term in earlier times, it is agreed Zhong Kui became a well defined figure by the end of the Tang period. That’s also when legends about his origin started to circulate.

The legend of Zhong Kui

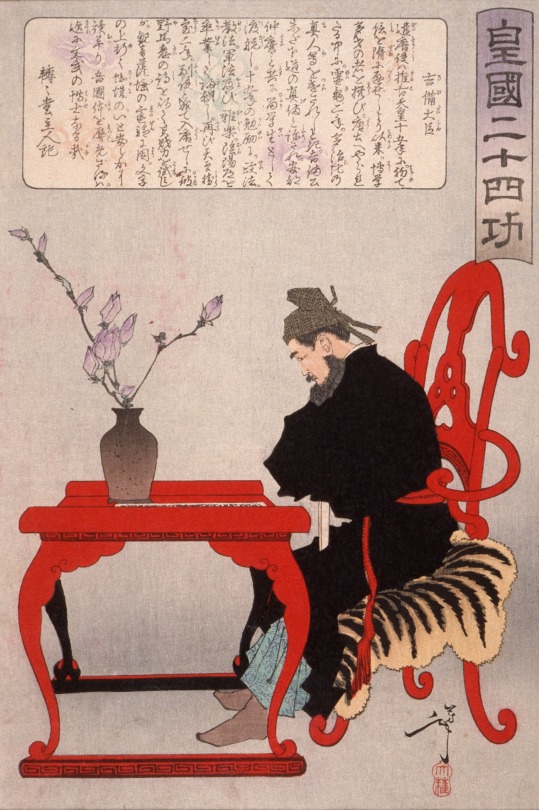

A typical depiction of Zhong Kui as a Tang period official by the Qing period artist Lü Xue (wikimedia commons)

According to the most popular version of Zhong Kui’s origin story, he was a scholar from the Zhongnan Mountains who lived during the reign of Gaozu of Tang (reigned 618-626). He took part either in the imperial examination or the imperial military examination (that’s an ahistorical detail - it was established by Wu Zetian in 702), but failed.

This detail is not elaborated upon further in early accounts, but by the Ming period it was attributed not to lack of skill but rather to prejudice against Zhong Kui’s physical appearance (he is fairly consistently described as dark-skinned, unusually tall, with a bulbous head and excessive facial hair). It’s possible that this new backstory was based in part on experiences of real officials of foreign origin, whose appearance was sometimes mocked by their peers, as already documented in Tang sources. Another possibility is that the descriptions were meant to be exaggerated to the point of making him resemble a demon, though.

Either way, out of despair caused by failure Zjong Kui committed suicide by smashing his head against the steps leading to the imperial palace. However, since in his final words he swore to protect the emperor and his realm, he didn’t return as a vengeful ghost, but rather as a queller of malevolent supernatural entities. Alternatively, he took this role out of gratitude for Gaozu, who was saddened by his death and organized the burial worthy of an honored official for him. Note that in later plays which often serve as the basis for modern adaptations, the burial is typically arranged by a certain Du Ping (杜平), a friend of Zhong Kui from back home.

Apparently a version in which the kings of hell are so impressed by Zhong Kui that they decide to make him the king of the ghosts also exists, though I was unable to track down its original source. In any case, he is associated with Mount Fengdu - one of the terms referring to the realm of the dead - in a poem by Song Wu (宋无; 1260–1340) already. He, or at least generic clerk figures based on his iconography, also sometimes appear in Song period paintings of the Ten Kings.

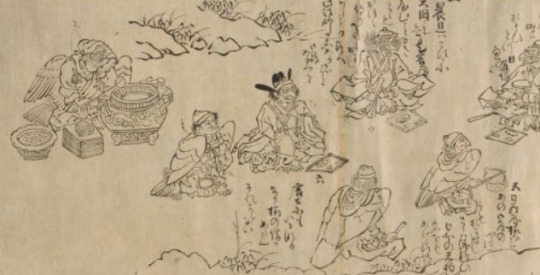

Several Zhong Kui-like clerks from a depiction of hell in Sermon on Mani's Teaching of Salvation (wikimedia commons)

According to Shih-shan Huang a single example of such a figure has even been identified in a Manichaean context, specifically in the scroll Sermon on Mani’s Teaching on Salvation.

Manichaean curiosities aside, supposedly the first person to be aided by Zhong Kui was emperor Xuanzong of Tang. At some point he fell gravely ill. In a dream, he saw a demon who attempted to steal a flute which was one of his most prized possessions. However, the attempt was foiled by a fearsome giant, who dealt with the thief rather brutally, poking out one of his eyes and then devouring him. After completing this act of demon quelling, he explained that he is Zhong Kui, and how he came to fulfill his current role.

After waking up, Xuanzong felt healthy again. He was so impressed he commissioned Wu Daozi, arguably the most famous artist in China at the time, to prepare a painting of Zhong Kui which could be used as a talisman against any further supernatural issues. Supposedly it left quite the impression on the general populace, and soon numerous images of Zhong Kui started to be distributed as talismans. There is definitely a kernel of truth to this part of the legend, as eyewitness accounts of Wu Daozi’s painting exist, but the work itself is lost.

As a side note, it’s worth pointing out the flute thief demon, despite meeting a gruesome end here, enjoyed a literary afterlife of his own. A certain Li Mingfeng (李鳴鳳), the author of a colophon on one of the earliest surviving Zhong Kui paintings, suggests that the (in)famous rebel An Lushan might have been a reincarnation of this specific entity. While I am not aware of any other attempts at providing him with a backstory, in Ming period retellings of the legend, he received a name, Xu Hao (虛耗).

Zhong Kui’s later career

Zhong Kui’s popularity grew after the Tang period, and he arguably eclipsed figures such as the fangxiang (方相) or the baize (白沢) as the demon queller par excellence. Legends about his origin and his first notable act of demon quelling which I summarized above spread far and wide during the reign of the Song dynasty.

After becoming a well defined figure, Zhong Kui came to be most commonly classified as a ghost (鬼; gui). In texts from the Song and Yuan periods he is often labeled more specifically as a “big ghost” (大鬼, dagui) or “ghost hero” (鬼雄, guixiong). However, his popularity effectively made him a god in popular imagination, and as a matter of fact he is referred to as such. His divinity is not exactly conventional, though. This topic is addressed in Fu Lu Shou Xianguan Qinghui 福祿壽仙官慶會 (The Immortal Officials of Happiness, Wealth and Longevity Gather in Celebration) by the Ming playwright Zhu Youdun (朱有燉; 1379-1435). Zhong Kui says himself that unlike his peers, he has no festival to call his own, and receives no regular offerings - and yet, he still vanquishes malicious entities on behalf of humans as long as talismans showing him continue to be distributed.

Interestingly, despite his long career in texts, no images of Zhong Kui older than the thirteenth century are known. This is mostly a matter of selective preservation, though - we know that depictions of him existed as early as in the ninth century, and that they were mass produced, presumably as woodblock prints, in the tenth. However, he didn’t necessarily look similar to his modern depictions. He actually only came to be depicted as a Tang scholar in the Song period. It seems earlier his costume might have varied.

One thing which seemingly remained consistent when it comes to Zhong Kui’s appearance is his facial hair. This feature is even emphasized in many of his epithets, such as “Old Beard” (老髯, Lao Ran), “Bearded Elder” (髯翁, Ran Wong) or “Bearded Lord” (髯君, Ran Jun). It’s possible that this was initially a way to highlight his vitality and his opposition to disease-causing demons.

Tang and Song sources indicate the state of facial hair could be viewed as an indicator of health. There’s even a handful of peculiar anecdotes about certain emperors, like Taizong of Tang or Renzong of Song, believing their facial hair has supernatural healing powers and offering ailing courtiers concoctions in which it was one of the ingredients. There’s no evidence Zhong Kui’s hair was ever believed to serve a similar purpose, though.

Not all of Zhong Kui’s titles revolve around his beard, though. An interesting example is “Nine-Headed Hermit” (九首山人). The intent isn’t to imply he has nine heads, it’s a multilayered pun instead. The character 馗 in Zhong Kui’s name is a combination of 九, “nine”, and 首, “head”. Referring to him as a “hermit”, literally “man of the mountain”, is likely supposed to show that he traverses areas traditionally believed to be inhabited by demons.

The nine-headed snake Xiangliu (wikimedia commons)

Chun-Yi Tsai suggests that this title also highlights Zhong Kui’s physical prowess by implicitly evoking “a nine-headed serpent known for its tremendous strength in Guideways through Mountains and Seas” (presumably Xiangliu).

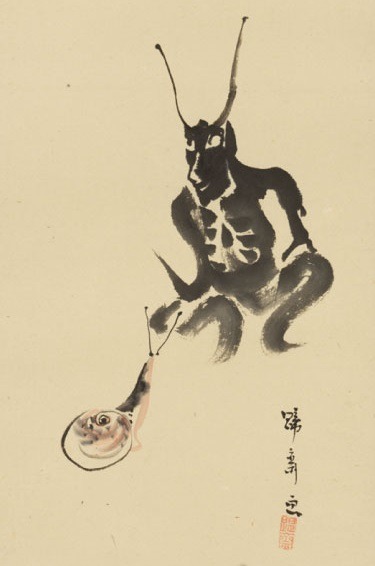

Zhong Kui’s strength lets him punish his enemies in various unexpectedly creative ways. The earliest sources already mention he could grind vanquished demons in a mill, for instance. References to eating them are particularly common. Depending on the source, Zhong Kui might simply devour them whole, hunt and prepare them like game animals, chop them up to pickle them, mince them to prepare meat snacks, squeeze them to make juice and wine, and so on.

Such comedically gruesome descriptions are generally limited to textual sources, since violence was rarely depicted in other mediums, even in relation to military topics. Wu Daozi’s lost painting was apparently one of the exceptions, as according to a tenth century description it showed Zhong Kui gouging out the eyes of the captured demon.

Zhong Kui’s sister and other assistants

While Zhong Kui is often depicted in the company of nondescript demons, there are relatively few recurring figures associated with him. The main exception is his sister. The Song period painter Gong Kai (龔開) and his contemporary Li Mingfeng (李鳴鳳) simply refer to her as Amei (阿妹), literally “younger sister”, though here it’s apparently a personal name, following Chun-yi Tsai’s interpretation. Her origin is unknown, and she is not present in any of the early variants of the legend.

Zhong Kui Marrying Off His Sister (wikimedia commons)

Today Zhong Kui’s sister is known chiefly from works of art in various mediums which can be broadly subsumed under the label “Zhong Kui marrying off his sister” (鍾馗嫁妹, Zhong Kui jiamei) which proliferated through the Ming and Qing periods. This label is sometimes applied to earlier paintings too, for example Zhong Kui Marrying Off His Sister (鍾馗嫁妹圖, Zhong Kui jiamei tu) is the conventional modern title of a scroll attributed to the poorly known painter Yan Geng (顏庚). A colophon from the Ming period describing this work calls the figure presumed to be Zhong Kui’s sister Ayi (阿姨; an informal way to refer a maternal aunt) as opposed to Amei.

Chun-yi Tsai states it is not impossible that the woman is supposed to be Zhong Kui’s wife, rather than his sister, though. The painting can be dated to the Yuan period, and there is no evidence for the story of Zhong Kui marrying off his sister before the Ming plays - granted, it is not impossible that it was already in circulation earlier. Still, other paintings showing Zhong Kui marrying off his sister only date to the Qing period. Additionally, the procession might be a parody of paintings showing rural marriages or couples moving to a new house.

While as far as I am aware this eventually went out of fashion, in early sources Zhong Kui’s sister could be portrayed as an exorcist herself. An example can be found in one of the sermons of the Chan monk Yuanwu (圓悟; 1063–1135), in which he states that celebrations on the “Double Fifth” (端午節, duanwu jie) - the fifth day of the fifth month - involved a dance of “Zhong Kui and his little sister”. A reference to performers dressed up as the pair (as well as kings of hell, gods of soil and stove, various warrior deities and more) has alsobeen identified in an account of celebrations in Kaifeng from the end of the reign of the Northern Song dynasty.

Similar evidence can be found in art too. For example, Zheng Yuanyou (鄭元祐; 1292-1364) in a poem inspired by a painting titled Zhong Kui’s Sister (馗妹圖; as far as I am aware, this work has not been identified) states that she travels alongside her brother, that she’s armed with a sword, and that demons fear her. A related portrayal of her is known from a critical review of the works of Si Yizhen (姒頤真), a Song dynasty painter. According to Gong Kai, in one of his paintings she is shown in tattered (or unbuttoned - the term used, 披襟, can mean both) clothes, and chases away a boar attacking her brother. He was evidently not fond of this innovation, and criticizes it as “vulgar” and inappropriate.

It needs to be stressed that Gong Kai’s displeasure wasn’t necessarily tied to presenting Zhong Kui’s sister as a demon queller, though. In fact, he is actually the author of the most famous work portraying her in this role.

Gong Kai's take on Zhong Kui's sister and her attendants (wikimedia commons; cropped for the ease of viewing)

Gong Kai depicted Amei in unusual black makeup, which is also worn by female demons accompanying her (note the one carrying a kitty!). This might be a parody of the sanbai (三白; “three whites”) face painting popular in the Song period. She and her attendants wear robes decorated with depictions of the “five poisons” (五毒), a term referring to animals perceived as particularly dangerous and inauspicious. The exact list varies, though centipedes, scorpions and snakes in particular are mainstays. The five poisons are directly associated with Zhong Kui, as he can be invoked to ward them off. Direct evidence first appears in the Qing period in accounts of the well known Dragon Boat Festival, but it’s not impossible this was an earlier development.

It is presumed that Gong Kai’s painting might depict Zhong Kui and Amei looking for a demonic version of Yang Guifei, as indicated by various hints in colophons. Her portrayals in art are quite diverse, but attributing demonic traits to her would be hardly unparalleled - she could even be described as a “palace demon” (宮妖, gong yao). The decline of the Tang dynasty was blamed on her, and metaphorically she might have been invoked to criticize other people believed to improperly use the power granted to them by the imperial court.

Gong Kai’s painting also depicts a less recurring member of Zhong Kui’s entourage. One of the demons carries a fox, specifically a nine-tailed specimen. The association between this animal and Zhong Kui goes all the way back to the early Tang period. In one of the Dunhuang manuscripts, the demon queller’s entourage includes a nine-tailed fox and a baize, who acted as bringers of good luck alongside him. It’s also worth pointing out that in another text from the same site, his mount during the hunt for a wangliang (魍魎; I will likely cover this entity a future article, stay tuned) is a “wild fox”.

Chun-Yi Tsai attributes the inclusion of a nine-tailed fox among Zhong Kui’s servants as a “family pet” of sorts to the portrayals of this supernatural creature both as an apotropaic antidote to poison (including the five poisons) and as a demon in its own right. It would be a suitable member of Zhong Kui’s entourage both as a conquered malevolent being and as an amplifier for his exorcistic, protective power.

A further possibility is that the association is the result of wordplay. A new year celebration involving a procession of people dressed up as members of Zhong Kui’s entourage, including his sister and various supernatural attendants, was known as dayehu (打夜胡). The homphony between 胡 and 狐, “fox”, might have resulted in the inclusion of the animal among the helpers.

Post scriptum: Zhong Kui in Japan

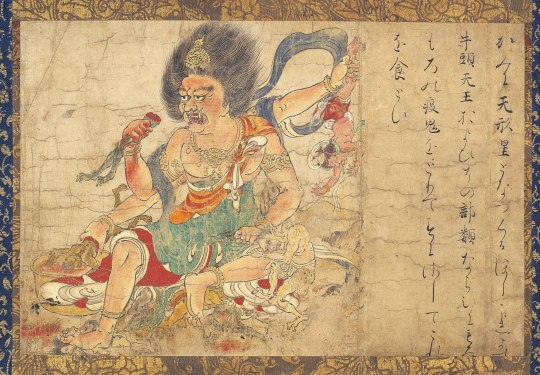

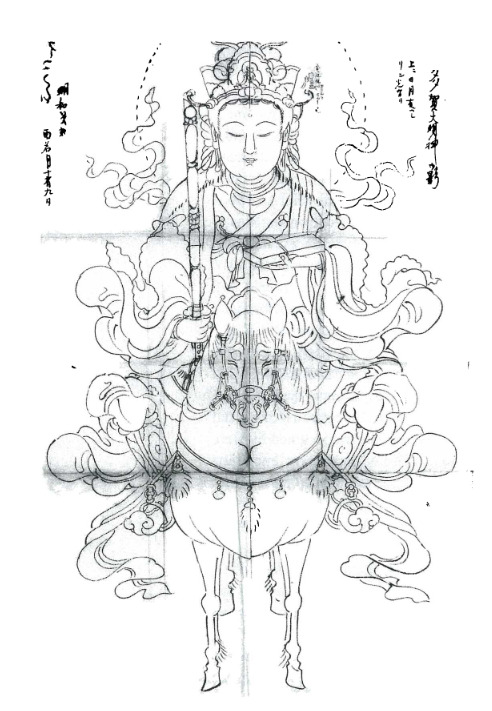

Zhong Kui, as depicted in Extermination of Evil (wikimedia commons)

Zhong Kui - or rather Shōki, following the Japanese reading of his name - probably reached Japan in the Insei period. Many other figures originating in China reached a considerable degree of popularity in Japan at roughly the same time - Taishan Fujun, Siming, Wudao Dashen, Pangu, Shennong, the examples keep piling up.

The oldest known Japanese depiction of Zhong Kui, which you can see above, is a painting from the twelfth century set known as Extermination of Evil. It might look a bit outlandish compared to most of the other depictions shown through this article, but I was able to locate a very close Chinese parallel:

A Yuan period depiction of Zhong Kui from the collection of the Beijing Library, via Richard von Glahn’s Sinister Way. Reproduced here for educational purposes only.

This is a Yuan period illustration said to be based on Wu Daozi’s painting. Zhong Kui doesn’t look like a Tang scholar yet, and the jacket and wide-brimmed hat are remarkably similar. It seems safe to assume that the Japanese painter was following a similar model - presumably one of the many now lost early depictions of Zhong Kui.

Slightly antiquated iconography surviving far away from the core area associated with a specific figure would hardly be unparalleled - it has been recently suggested that the baize/hakutaku is a similar case, with Japanese depictions and descriptions matching Tang sources fairly closely, but missing the elements which developed in the Song period or later.

For the most part, Zhong Kui fulfilled a similar role in Japan as in China: he was regarded as a fearsome demon queller, and images representing him were distributed for apotropaic purposes. However, it’s also important to note that there were certain innovations. He arrived in Japan at the brink of the middle ages - theologically speaking an era of unparalleled innovation, during which both native and imported figures were interpreted in unexpected ways, leading to the rise of a new “medieval mythology”. Zhong Kui was hardly an exception from this trend.

A “medieval myth” involving Zhong Kui is known from Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), an onmyōdō treatise traditionally attributed to Abe no Seimei, but most likely written by one of his descendants in the fourteenth century. Curiously, Zhong Kui’s name is written in it as 商貴 instead of the expected 鍾馗.

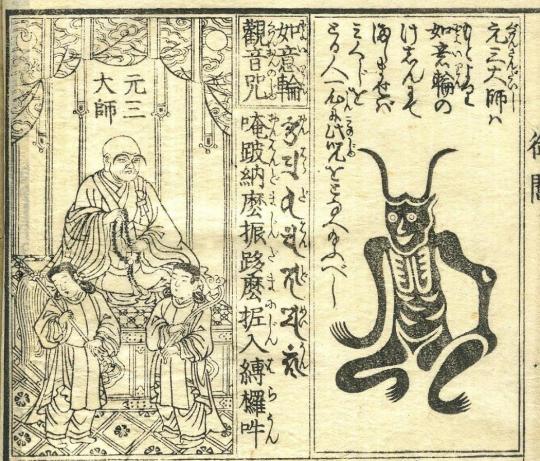

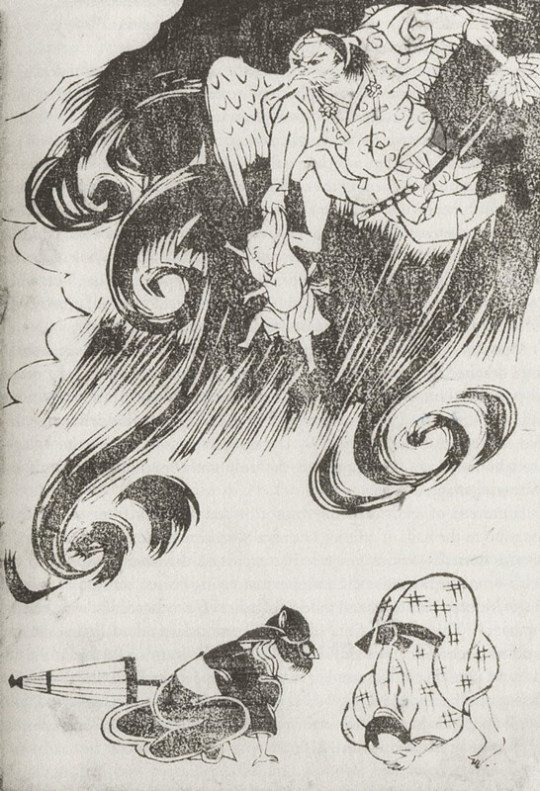

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

In the Hoki Naiden, Zhong Kui is still a queller of malevolent supernatural beings. However, instead of being a scorned scholar, he is a yaksha who became the ruler of Rājagṛha, a city in India. He is said to correspond to both the medieval Japanese deity Gozu Tennō (牛頭天王), and to his celestial “double” Tenkeisei (天刑星; from Chinese Tianxingxing), the “star of heavenly punishment” (I covered him here). They are said to be his manifestations respectively on earth and in heaven.

This equation might seem random at first glance, but both of them actually had a lot in common with Zhong Kui: all three were believed to keep demons, especially those causing diseases, in check. Curiously, the reinterpretation of Zhong Kui as a yaksha turned king can also be found in the Genkō Shakusho (元亨釈書), a Kamakura period Buddhist history book. However, I am not aware of any studies examining it in more detail. I assume identifying him as a yaksha was a result of association with Gozu Tennō (I briefly discussed his yaksha credentials here), rather than the other way around, though.

While Hoki Naiden ultimately pertains more to medieval than modern religion, it’s worth noting that an unconventional take on Zhong Kui is still part of an extant tradition. Through history, Zhong Kui could be identified as a dōsojin (道祖神). This term denotes a class of deities meant to protect roads, crossroads and borders of villages. In parts of the Niigata prefecture this form of him is sometimes referred to as Shōki Daimyōjin (鍾馗大明神) today.

Bibliography

Joshua Capitanio, Epidemics and Plague in Premodern Chinese Buddhism

Bernard Faure, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Richard von Glahn, The Sinister Way: The Divine and the Demonic in Chinese Religious Culture

Shih-shan Susan Huang, Picturing the True Form. Daoist Visual Culture in Traditional China

Wilt Idema & Stephen H. West, Zhong Kui at Work: A Complete Translation of The Immortal Officials Of Happiness, Wealth, and Longevity Gather in Celebration , by Zhu Youdun (1379–1439)

Chun-Yi Joyce Tsai, Imagining the Supernatural Grotesque: Paintings of Zhong Kui and Demons in the Late Southern Song (1127-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) Dynasties

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

A replacement for the various "recommended reading" posts from a few years ago. I'll probably keep updating it semi-regularly.

The section titles indicate what I am interested in actually discussing, to avoid further potential issues with people asking me to essentially provide them with bibliographies pertaining to topics I have no interest in discussing in depth or knowledge of or both.

I don't expect everyone who wants to send an ask to read everything here or even everything in a given section but I do recommend at least trying to find out if a question can be answered by an article or book listed here first.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

A huge problem with Touhou-adjacent discussion of Matarajin is that people assume Matarajin is a historical outlier among Japanese deities - uniquely complex and obscure - as opposed to a median example of what theology was like in the middle ages. There are dozens of similar examples (Megumu is literally named after another lol), on top of figures from classical mythology, all the way up to Amaterasu, being reinterpreted through a similar lens.

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

Broke: Sariel is an angel so christianity is canon in Touhou

Woke: pc-98 isn't canon, Sariel doesn't exist

Bespoke: Sariel is a tengu in makai

There’s no way to make Sariel work as a tengu without making the character seem like even more of a messy product of the occult boom - and having a character named Sariel reside in makai is already basically just mashing random “esoteric” terms together at random, with all due respect for young ZUN.

However, there IS a way to make Sariel true to the actual figure without necessarily having to go through the usual arguments over implications of Christianity in Touhou. I will admit that's generally a topic I'm not a fan of; I get the impression people are more eager to discuss that than anything even vaguely Buddhism-related, which bugs me. Even the Buddhist background of multiple characters gets ignored. People do it even with Okina somehow.

Anyway, Sariel’s career arguably peaked not in any Abrahamic, let alone specifically Christian, tradition, but rather in Chinese Manichaean sources. Here the standard grouping of four archangels invariably includes Sariel (娑囉逸囉, Suoluoyiluo) alongside the strictly biblical Michael, Gabriel and Raphael. However, their role is defined in terms borrowed from Buddhism - functionally they are the Four Heavenly Kings. This label is actually applied to them outright every now and then (if you’re curious, Sariel corresponds to west and thus Virūpākṣa/Kōmokuten). A good treatment of the whole phenomenon can be found in Gábor Kósa’s article Near Eastern Angels in Chinese Manichaean Texts.

Manichaeans had a penchant for combining basically every source they stumbled upon - you won’t find any other pre-modern religion with a canon which includes Jesus, Buddha, Ahriman and Humbaba (a distant echo of Humbaba, at least) at once. It’s essentially extinct today, and for the most part has been for a millennium or so, but in some parts of China like Xiapu in Fujian it survived well into the fourteenth century (as a matter of fact, one of the Manichaean sources discussing Sariel is that late; see here; more broadly on its late survival see here). The closest thing to a surviving Manichaean temple, Cao’an, is Buddhist today. In at least one case a Manichaean painting found its way to Japan and for centuries was presumed to be a Buddhist icon; you can read the whole story here, it’s genuinely thrilling.

Sariel also has a fair share of interesting material elsewhere: Targum Neofiti assigns this name to the angel who wrestled Jacob, for example. However, I will admit the Manichaean take in my favorite.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

I originally only checked it out for some information on Da Ji and Bixia Yuanjun but what I got was really something special, can't recommend it enough it'll completely change your perspective on foxes in east asian folklore.

The Cult of the Fox: Power, Gender, and Popular Religion in Late Imperial and Modern China by Xiaofei Kang (2006)

This book was originally recommended to me by my friend 9 while I was working on the Tsukasa post last year, and initially I only planned to take a cursory glance to perhaps find some fun trivia. However, it ended up unexpectedly engaging - much more than I expected from a dense monograph on a topic I actually didn’t have much interest in prior. I can safely say it deserves all the praise it got.

The title honestly undersells what this study is - Kang covers earlier material too. A lot of space is devoted to the Tang period in particular due to its formative role. Despite its value as a scholarly source, it’s also not inaccessible - you probably could pretty much read it as if it was a collection of anecdotes with particularly dense introductions.

Foxes were evidently seen as incredibly versatile literary characters. Divine splendor of foxes acting as attendants of deities or pursuing immortality intersects with anecdotes about beleaguered officials meeting with them in abandoned buildings to drink and discuss “historical beauties” (a subject foxes are experts in, as it turns out).

Literary fiction isn't all, though. While distinct from gods, ancestors, ghosts and so on, foxes remained a fixture of religious life, especially on the folk level. Kang actually conducted a field study to showcase modern examples in addition to historical ones. However, she makes sure to highlight official attitudes were often ambivalent - the republican and communist governments’ perception of local fox customs as superstition was not without earlier historical precedent.

What I found particularly interesting is that it would appear that the study of the perception of foxes tells us as much, if not more, about humans as it does about these animals themselves. Through history, foxes could be used to metaphorically represent virtually every possible group at the margins of society: immigrants (especially Sogdians), courtesans, officials with humble backgrounds trying to trick their way into marriage with daughters of noble families (some of them wrote stories where their fox self inserts fail at it), and more. They were the quintessential image of every type of The Other at once.

10 out of 10 stars or whatever.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shikigami and onmyōdō through history: truth, fiction and everything in between

Abe no Seimei exorcising disease spirits (疫病神, yakubyōgami), as depicted in the Fudō Riyaku Engi Emaki. Two creatures who might be shikigami are visible in the bottom right corner (wikimedia commons; identification following Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage, pp. 57-58)

In popular culture, shikigami are basically synonymous with onmyōdō. Was this always the case, though? And what is a shikigami, anyway? These questions are surprisingly difficult to answer. I’ve been meaning to attempt to do so for a longer while, but other projects kept getting in the way. Under the cut, you will finally be able to learn all about this matter.

This isn’t just a shikigami article, though. Since historical context is a must, I also provide a brief history of onmyōdō and some of its luminaries. You will also learn if there were female onmyōji, when stars and time periods turn into deities, what onmyōdō has to do with a tale in which Zhong Kui became a king of a certain city in India - and more!

The early days of onmyōdō

In order to at least attempt to explain what the term shikigami might have originally entailed, I first need to briefly summarize the history of onmyōdō (陰陽道). This term can be translated as “way of yin and yang”, and at the core it was a Japanese adaptation of the concepts of, well, yin and yang, as well as the five elements. They reached Japan through Daoist and Buddhist sources. Daoism itself never really became a distinct religion in Japan, but onmyōdō is arguably among the most widespread adaptations of its principles in Japanese context.

Kibi no Makibi, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (wikimedia commons)

It’s not possible to speak of a singular founder of onmyōdō comparable to the patriarchs of Buddhist schools. Bernard Faure notes that in legends the role is sometimes assigned to Kibi no Makibi, an eighth century official who spent around 20 years in China. While he did bring many astronomical treatises with him when he returned, this is ultimately just a legend which developed long after he passed away.

In reality onmyōdō developed gradually starting with the sixth century, when Chinese methods of divination and treatises dealing with these topics first reached Japan. Early on Buddhist monks from the Korean kingdom of Baekje were the main sources of this knowledge. We know for example that the Soga clan employed such a specialist, a certain Gwalleuk (観勒; alternatively known under the Japanese reading of his name, Kanroku).

Obviously, divination was viewed as a very serious affair, so the imperial court aimed to regulate the continental techniques in some way. This was accomplished by emperor Tenmu with the formation of the onmyōryō (陰陽寮), “bureau of yin and yang” as a part of the ritsuryō system of governance. Much like in China, the need to control divination was driven by the fears that otherwise it would be used to legitimize courtly intrigues against the emperor, rebellions and other disturbances.

Officials taught and employed by onmyōryō were referred to as onmyōji (陰陽師). This term can be literally translated as “yin-yang master”. In the Nara period, they were understood essentially as a class of public servants. Their position didn’t substantially differ from that of other specialists from the onmyōryō: calendar makers, officials responsible for proper measurement of time and astrologers. The topics they dealt with evidently weren’t well known among commoners, and they were simply typical members of the literate administrative elite of their times.

Onmyōdō in the Heian period: magic, charisma and nobility

The role of onmyōji changed in the Heian period. They retained the position of official bureaucratic diviners in employ of the court, but they also acquired new duties. The distinction between them and other onmyōryō officials became blurred. Additionally their activity extended to what was collectively referred to as jujutsu (呪術), something like “magic” though this does not fully reflect the nuances of this term. They presided over rainmaking rituals, purification ceremonies, so-called “earth quelling”, and establishing complex networks of temporal and directional taboos.

A Muromachi period depiction of Abe no Seimei (wikimedia commons)

The most famous historical onmyōji like Kamo no Yasunori and his student Abe no Seimei were active at a time when this version of onmyōdō was a fully formed - though obviously still evolving - set of practices and beliefs. In a way they represented a new approach, though - one in which personal charisma seemed to matter just as much, if not more, than official position. This change was recognized as a breakthrough by at least some of their contemporaries. For example, according to the diary of Minamoto no Tsuneyori, the Sakeiki (左經記), “in Japan, the foundations of onmyōdō were laid by Yasunori”.

The changes in part reflected the fact that onmyōji started to be privately contracted for various reasons by aristocrats, in addition to serving the state. Shin’ichi Shigeta notes that it essentially turned them from civil servants into tradespeople. However, he stresses they cannot be considered clergymen: their position was more comparable to that of physicians, and there is no indication they viewed their activities as a distinct religion. Indeed, we know of multiple Heian onmyōji, like Koremune no Fumitaka or Kamo no Ieyoshi, who by their own admission were devout Buddhists who just happened to work as professional diviners.

Shin’ichi Shigeta notes is evidence that in addition to the official, state-sanctioned onmyōji, “unlicensed” onmyōji who acted and dressed like Buddhist clergy, hōshi onmyōji (法師陰陽師) existed. The best known example is Ashiya Dōman, a mainstay of Seimei legends, but others are mentioned in diaries, including the famous Pillow Book. It seems nobles particularly commonly employed them to curse rivals. This was a sphere official onmyōji abstained from due to legal regulations. Curses were effectively considered crimes, and government officials only performed apotropaic rituals meant to protect from them.

The Heian period version of onmyōdō captivated the imagination of writers and artists, and its slightly exaggerated version present in classic literature like Konjaku Monogatari is essentially what modern portrayals in fiction tend to go back to.

Medieval onmyōdō: from abstract concepts to deities

Gozu Tennō (wikimedia commons)

Further important developments occurred between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. This period was the beginning of the Japanese “middle ages” which lasted all the way up to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. The focus in onmyōdō in part shifted towards new, or at least reinvented, deities, such as calendarical spirits like Daishōgun (大将軍) and Ten’ichijin (天一神), personifications of astral bodies and concepts already crucial in earlier ceremonies. There was also an increased interest in Chinese cosmological figures like Pangu, reimagined in Japan as “king Banko”. However, the most famous example is arguably Gozu Tennō, who you might remember from my Susanoo article.

The changes in medieval onmyōdō can be described as a process of convergence with esoteric Buddhism. The points of connection were rituals focused on astral and underworld deities, such as Taizan Fukun or Shimei (Chinese Siming). Parallels can be drawn between this phenomenon and the intersection between esoteric Buddhism and some Daoist schools in Tang China. Early signs of the development of a direct connection between onmyōdō and Buddhism can already be found in sources from the Heian period, for example Kamo no Yasunori remarked that he and other onmyōji depend on the same sources to gain proper understanding of ceremonies focused on the Big Dipper as Shingon monks do.

Much of the information pertaining to the medieval form of onmyōdō is preserved in Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), a text which is part divination manual and part a collection of myths. According to tradition it was compiled by Abe no Seimei, though researchers generally date it to the fourteenth century. For what it’s worth, it does seem likely its author was a descendant of Seimei, though.

Outside of specialized scholarship Hoki Naiden is fairly obscure today, but it’s worth noting that it was a major part of the popular perception of onmyōdō in the Edo period. A novel whose influence is still visible in the modern image of Seimei, Abe no Seimei Monogatari (安部晴明物語), essentially revolves around it, for instance.

Onmyōdō in the Edo period: occupational licensing

Novels aside, the first post-medieval major turning point for the history of onmyōdō was the recognition of the Tsuchimikado family as its official overseers in 1683. They were by no means new to the scene - onmyōji from this family already served the Ashikaga shoguns over 250 years earlier. On top of that, they were descendants of the earlier Abe family, the onmyōji par excellence. The change was not quite the Tsuchimikado’s rise, but rather the fact the government entrusted them with essentially regulating occupational licensing for all onmyōji, even those who in earlier periods existed outside of official administration.

As a result of the new policies, various freelance practitioners could, at least in theory, obtain a permit to perform the duties of an onmyōji. However, as the influence of the Tsuchimikado expanded, they also sought to oblige various specialists who would not be considered onmyōji otherwise to purchase licenses from them. Their aim was to essentially bring all forms of divination under their control. This extended to clergy like Buddhist monks, shugenja and shrine priests on one hand, and to various performers like members of kagura troupes on the other.

Makoto Hayashi points out that while throughout history onmyōji has conventionally been considered a male occupation, it was possible for women to obtain licenses from the Tsuchimikado. Furthermore, there was no distinct term for female onmyōji, in contrast with how female counterparts of Buddhist monks, shrine priests and shugenja were referred to with different terms and had distinct roles defined by their gender.

As far as I know there’s no earlier evidence for female onmyōji, though, so it’s safe to say their emergence had a lot to do with the specifics of the new system. It seems the poems of the daughter of Kamo no Yasunori (her own name is unknown) indicate she was familiar with yin-yang theory or at least more broadly with Chinese philosophy, but that’s a topic for a separate article (stay tuned), and it's not quite the same, obviously.

The Tsuchimikado didn’t aim to create a specific ideology or systems of beliefs. Therefore, individual onmyōji - or, to be more accurate, individual people with onmyōji licenses - in theory could pursue new ideas. This in some cases lead to controversies: for instance, some of the people involved in the (in)famous 1827 Osaka trial of alleged Christians (whether this label really is applicable is a matter of heated debate) were officially licensed onmyōji. Some of them did indeed possess translated books written by Portuguese missionaries, which obviously reflected Catholic outlook. However, Bernard Faure suggests that some of the Edo period onmyōji might have pursued Portuguese sources not strictly because of an interest in Catholicism but simply to obtain another source of astronomical knowledge.

The legacy of onmyōdō

In the Meiji period, onmyōdō was banned alongside shugendō. While the latter tradition experienced a revival in the second half of the twentieth century, the former for the most part didn’t. However, that doesn’t mean the history of onmyōdō ends once and for all in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Even today in some parts of Japan there are local religious traditions which, while not identical with historical onmyōdō, retain a considerable degree of influence from it. An example often cited in scholarship is Izanagi-ryū (いざなぎ流) from the rural Monobe area in the Kōchi Prefecture. Mitsuki Ueno stresses that the occasional references to Izanagi-ryū as “modern onmyōdō” in literature from the 1990s and early 2000s are inaccurate, though. He points out they downplay the unique character of this tradition, and that it shows a variety of influences. Similar arguments have also been made regarding local traditions from the Chūgoku region.

Until relatively recently, in scholarship onmyōdō was basically ignored as superstition unworthy of serious inquiries. This changed in the final decades of the twentieth century, with growing focus on the Japanese middle ages among researchers. The first monographs on onmyōdō were published in the 1980s. While it’s not equally popular as a subject of research as esoteric Buddhism and shugendō, formerly neglected for similar reasons, it has nonetheless managed to become a mainstay of inquiries pertaining to the history of religion in Japan.

Yoshitaka Amano's illustration of Baku Yumemakura's fictionalized portrayal of Abe no Seimei (right) and other characters from his novels (reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Of course, it’s also impossible to talk about onmyōdō without mentioning the modern “onmyōdō boom”. Starting with the 1980s, onmyōdō once again became a relatively popular topic among writers. Novel series such as Baku Yumemakura’s Onmyōji, Hiroshi Aramata’s Teito Monogatari or Natsuhiko Kyōgoku’s Kyōgōkudō and their adaptations in other media once again popularized it among general audiences. Of course, since these are fantasy or mystery novels, their historical accuracy tends to vary (Yumemakura in particular is reasonably faithful to historical literature, though). Still, they have a lasting impact which would be impossible to accomplish with scholarship alone.

Shikigami: historical truth, historical fiction, or both?

You might have noticed that despite promising a history of shikigami, I haven’t used this term even once through the entire crash course in history of onmyōdō. This was a conscious choice. Shikigami do not appear in any onmyōdō texts, even though they are a mainstay of texts about onmyōdō, and especially of modern literature involving onmyōji.

It would be unfair to say shikigami and their prominence are merely a modern misconception, though. Virtually all of the famous legends about onmyōji feature shikigami, starting with the earliest examples from the eleventh century. Based on Konjaku Monogatari, there evidently was a fascination with shikigami at the time of its compilation. Fujiwara no Akihira in the Shinsarugakuki treats the control of shikigami as an essential skill of an onmyōji, alongside the abilities to “freely summon the twelve guardian deities, call thirty-six types of wild birds (...), create spells and talismans, open and close the eyes of kijin (鬼神; “demon gods”), and manipulate human souls”.

It is generally agreed that such accounts, even though they belong to the realm of literary fiction, can shed light on the nature and importance of shikigami. They ultimately reflect their historical context to some degree. Furthermore, it is not impossible that popular understanding of shikigami based on literary texts influenced genuine onmyōdō tradition. It’s worth pointing out that today legends about Abe no Seimei involving them are disseminated by two contemporary shrines dedicated to him, the Seimei Shrine (晴明神社) in Kyoto and the Abe no Seimei Shrine (安倍晴明神社) in Osaka. Interconnected networks of exchange between literature and religious practice are hardly a unique or modern phenomenon.

However, even with possible evidence from historical literature taken into account, it is not easy to define shikigami. The word itself can be written in three different ways: 式神 (or just 式), 識神 and 職神, with the first being the default option. The descriptions are even more varied, which understandably lead to the rise of numerous interpretations in modern scholarship. Carolyn Pang in her recent treatments of shikigami, which you can find in the bibliography, has recently divided them into five categories. I will follow her classification below.

Shikigami take 1: rikujin-shikisen

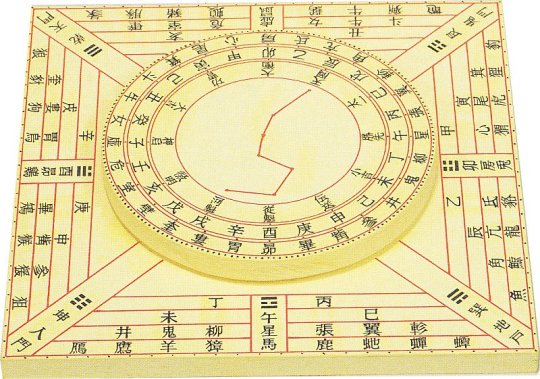

An example of shikiban, the divination board used in rikujin-shikisen (Museum of Kyoto, via onmarkproductions.com; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

A common view is that shikigami originate as a symbolic representation of the power of shikisen (式占) or more specifically rikujin-shikisen (六壬式占), the most common form of divination in onmyōdō. It developed from Chinese divination methods in the Nara period, and remained in the vogue all the way up to the sixteenth century, when it was replaced by ekisen (易占), a method derived from the Chinese Book of Changes.

Shikisen required a special divination board known as shikiban (式盤), which consists of a square base, the “earth panel” (地盤, jiban), and a rotating circle placed on top of it, the “heaven panel” (天盤, tenban). The former was marked with twelve points representing the signs of the zodiac and the latter with representations of the “twelve guardians of the months” (十二月将, jūni-gatsushō; their identity is not well defined). The heaven panel had to be rotated, and the diviner had to interpret what the resulting combination of symbols represents. Most commonly, it was treated as an indication whether an unusual phenomenon (怪/恠, ke) had positive or negative implications.

It’s worth pointing out that in the middle ages the shikiban also came to be used in some esoteric Buddhist rituals, chiefly these focused on Dakiniten, Shōten and Nyoirin Kannon. However, they were only performed between the late Heian and Muromachi periods, and relatively little is known about them. In most cases the divination board was most likely modified to reference the appropriate esoteric deities.

Shikigami take 2: cognitive abilities

While the view that shikigami represented shikisen is strengthened by the fact both terms share the kanji 式, a variant writing, 識神, lead to the development of another proposal. Since the basic meaning of 識 is “consciousness”, it is sometimes argued that shikigami were originally an “anthropomorphic realization of the active psychological or mental state”, as Caroline Pang put it - essentially, a representation of the will of an onmyōji. Most of the potential evidence in this case comes from Buddhist texts, such as Bosatsushotaikyō (菩薩処胎経).

However, Bernard Faure assumes that the writing 識神 was a secondary reinterpretation, basically a wordplay based on homonymy. He points out the Buddhist sources treat this writing of shikigami as a synonym of kushōjin (倶生神). This term can be literally translated as “deities born at the same time”. Most commonly it designates a pair of minor deities who, as their name indicates, come into existence when a person is born, and then records their deeds through their entire life. Once the time for Enma’s judgment after death comes, they present him with their compiled records. It has been argued that they essentially function like a personification of conscience.

Shikigami take 3: energy

A further speculative interpretation of shikigami in scholarship is that this term was understood as a type of energy present in objects or living beings which onmyōji were believed to be capable of drawing out and harnessing to their ends. This could be an adaptation of the Daoist notion of qi (氣). If this definition is correct, pieces of paper or wooden instruments used in purification ceremonies might be examples of objects utilized to channel shikigami.

The interpretation of shikigami as a form of energy is possibly reflected in Konjaku Monogatari in the tale The Tutelage of Abe no Seimei under Tadayuki. It revolves around Abe no Seimei’s visit to the house of the Buddhist monk Kuwanten from Hirosawa. Another of his guests asks Seimei if he is capable of killing a person with his powers, and if he possesses shikigami. He affirms that this is possible, but makes it clear that it is not an easy task. Since the guests keep urging him to demonstrate nonetheless, he promptly demonstrates it using a blade of grass. Once it falls on a frog, the animal is instantly crushed to death. From the same tale we learn that Seimei’s control over shikigami also let him remotely close the doors and shutters in his house while nobody was inside.

Shikigami take 4: curse

As I already mentioned, arts which can be broadly described as magic - like the already mentioned jujutsu or juhō (呪法, “magic rituals”) - were regarded as a core part of onmyōji’s repertoire from the Heian period onward. On top of that, the unlicensed onmyōji were almost exclusively associated with curses. Therefore, it probably won’t surprise you to learn that yet another theory suggests shikigami is simply a term for spells, curses or both. A possible example can be found in Konjaku Monogatari, in the tale Seimei sealing the young Archivist Minor Captains curse - the eponymous curse, which Seimei overcomes with protective rituals, is described as a shikigami.

Kunisuda Utagawa's illustration of an actor portraying Dōman in a kabuki play (wikimedia commons)

Similarities between certain descriptions of shikigami and practices such as fuko (巫蠱) and goraihō (五雷法) have been pointed out. Both of these originate in China. Fuko is the use of poisonous, venomous or otherwise negatively perceived animals to create curses, typically by putting them in jars, while goraihō is the Japanese version of Daoist spells meant to control supernatural beings, typically ghosts or foxes. It’s worth noting that a legend according to which Dōman cursed Fujiwara no Michinaga on behalf of lord Horikawa (Fujiwara no Kanemichi) involves him placing the curse - which is itself not described in detail - inside a jar.

Mitsuki Ueno notes that in the Kōchi Prefecture the phrase shiki wo utsu, “to strike with a shiki”, is still used to refer to cursing someone. However, shiki does not necessarily refer to shikigami in this context, but rather to a related but distinct concept - more on that later.

Shikigami take 5: supernatural being

While all four definitions I went through have their proponents, yet another option is by far the most common - the notion of shikigami being supernatural beings controlled by an onmyōji. This is essentially the standard understanding of the term today among general audiences. Sometimes attempts are made to identify it with a specific category of supernatural beings, like spirits (精霊, seirei), kijin or lesser deities (下級神, kakyū shin). However, none of these gained universal support. Generally speaking, there is no strong indication that shikigami were necessarily imagined as individualized beings with distinct traits.

The notion of shikigami being supernatural beings is not just a modern interpretation, though, for the sake of clarity. An early example where the term is unambiguously used this way is a tale from Ōkagami in which Seimei sends a nondescript shikigami to gather information. The entity, who is not described in detail, possesses supernatural skills, but simultaneously still needs to open doors and physically travel.

An illustration from Nakifudō Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

In Genpei Jōsuiki there is a reference to Seimei’s shikigami having a terrifying appearance which unnerved his wife so much he had to order the entities to hide under a bride instead of residing in his house. Carolyn Pang suggests that this reflects the demon-like depictions from works such as Abe no Seimei-kō Gazō (安倍晴明公画像; you can see it in the Heian section), Fudōriyaku Engi Emaki and Nakifudō Engi Emaki.

Shikigami and related concepts

A gohō dōji, as depicted in the Shigisan Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

The understanding of shikigami as a “spirit servant” of sorts can be compared with the Buddhist concept of minor protective deities, gohō dōji (護法童子; literally “dharma-protecting lads”). These in turn were just one example of the broad category of gohō (護法), which could be applied to virtually any deity with protective qualities, like the historical Buddha’s defender Vajrapāṇi or the Four Heavenly Kings.

A notable difference between shikigami and gohō is the fact that the former generally required active summoning - through chanting spells and using mudras - while the latter manifested on their own in order to protect the pious. Granted, there are exceptions. There is a well attested legend according to which Abe no Seimei’s shikigami continued to protect his residence on own accord even after he passed away. Shikigami acting on their own are also mentioned in Zoku Kojidan (続古事談). It attributes the political downfall of Minamoto no Takaakira (源高明; 914–98) to his encounter with two shikigami who were left behind after the onmyōji who originally summoned them forgot about them.

A degree of overlap between various classes of supernatural helpers is evident in texts which refer to specific Buddhist figures as shikigami. I already brought up the case of the kushōjin earlier. Another good example is the Tendai monk Kōshū’s (光宗; 1276–1350) description of Oto Gohō (乙護法). He is “a shikigami that follows us like the shadow follows the body. Day or night, he never withdraws; he is the shikigami that protects us” (translation by Bernard Faure). This description is essentially a reversal of the relatively common title “demon who constantly follow beings” (常随魔, jōzuima). It was applied to figures such as Kōjin, Shōten or Matarajin, who were constantly waiting for a chance to obstruct rebirth in a pure land if not placated properly.

The Twelve Heavenly Generals (Tokyo National Museum, via wikimedia commons)

A well attested group of gohō, the Twelve Heavenly Generals (十二神将, jūni shinshō), and especially their leader Konpira (who you might remember from my previous article), could be labeled as shikigami. However, Fujiwara no Akihira’s description of onmyōji skills evidently presents them as two distinct classes of beings.

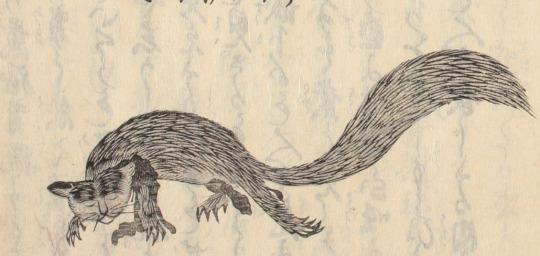

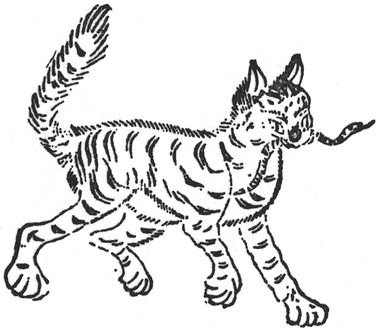

A kuda-gitsune, as depicted in Shōzan Chomon Kishū by Miyoshi Shōzan (Waseda University History Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Granted, Akihira also makes it clear that controlling shikigami and animals are two separate skills. Meanwhile, there is evidence that in some cases animal familiars, especially kuda-gitsune used by iizuna (a term referring to shugenja associated with the cult of, nomen omen, Iizuna Gongen, though more broadly also something along the lines of “sorcerer”), were perceived as shikigami.

Beliefs pertaining to gohō dōji and shikigami seemingly merged in Izanagi-ryū, which lead to the rise of the notion of shikiōji (式王子; ōji, literally “prince”, can be another term for gohō dōji). This term refers to supernatural beings summoned by a ritual specialist (祈祷師, kitōshi) using a special formula from doctrinal texts (法文, hōmon). They can fulfill various functions, though most commonly they are invoked to protect a person, to remove supernatural sources of diseases, to counter the influence of another shikiōji or in relation to curses.

Tenkeisei, the god of shikigami

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

The final matter which warrants some discussion is the unusual tradition regarding the origin of shikigami which revolves around a deity associated with this concept.

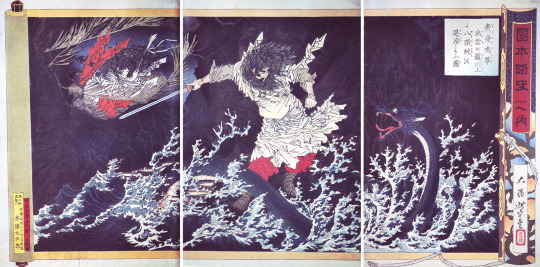

In the middle ages, a belief that there were exactly eighty four thousand shikigami developed. Their source was the god Tenkeisei (天刑星; also known as Tengyōshō). His name is the Japanese reading of Chinese Tianxingxing. It can be translated as “star of heavenly punishment”. This name fairly accurately explains his character. He was regarded as one of the so-called “baleful stars” (凶星, xiong xing) capable of controlling destiny. The “punishment” his name refers to is his treatment of disease demons (疫鬼, ekiki). However, he could punish humans too if not worshiped properly.

Today Tenkeisei is best known as one of the deities depicted in a series of paintings known as Extermination of Evil, dated to the end of the twelfth century. He has the appearance of a fairly standard multi-armed Buddhist deity. The anonymous painter added a darkly humorous touch by depicting him right as he dips one of the defeated demons in vinegar before eating him. Curiously, his adversaries are said to be Gozu Tennō and his retinue in the accompanying text. This, as you will quickly learn, is a rather unusual portrayal of the relationship between these two deities.

I’m actually not aware of any other depictions of Tenkeisei than the painting you can see above. Katja Triplett notes that onmyōdō rituals associated with him were likely surrounded by an aura of secrecy, and as a result most depictions of him were likely lost or destroyed. At the same time, it seems Tenkeisei enjoyed considerable popularity through the Kamakura period. This is not actually paradoxical when you take the historical context into account: as I outlined in my recent Amaterasu article, certain categories of knowledge were labeled as secret not to make their dissemination forbidden, but to imbue them with more meaning and value.

Numerous talismans inscribed with Tenkeisei’s name are known. Furthermore, manuals of rituals focused on him have been discovered. The best known of them, Tenkeisei-hō (天刑星法; “Tenkeisei rituals”), focuses on an abisha (阿尾捨, from Sanskrit āveśa), a ritual involving possession by the invoked deity. According to a legend was transmitted by Kibi no Makibi and Kamo no Yasunori. The historicity of this claim is doubtful, though: the legend has Kamo no Yasunori visit China, which he never did. Most likely mentioning him and Makibi was just a way to provide the text with additional legitimacy.

Other examples of similar Tenkeisei manuals include Tenkeisei Gyōhō (天刑星行法; “Methods of Tenkeisei Practice”) and Tenkeisei Gyōhō Shidai (天刑星行法次第; “Methods of Procedure for the Tenkeisei Practice”). Copies of these texts have been preserved in the Shingon temple Kōzan-ji.

The Hoki Naiden also mentions Tenkeisei. It equates him with Gozu Tennō, and explains both of these names refer to the same deity, Shōki (商貴), respectively in heaven and on earth. While Shōki is an adaptation of the famous Zhong Kui, it needs to be pointed out that here he is described not as a Tang period physician but as an ancient king of Rajgir in India. Furthermore, he is a yaksha, not a human. This fairly unique reinterpretation is also known from the historical treatise Genkō Shakusho.

Post scriptum

The goal of this article was never to define shikigami. In the light of modern scholarship, it’s basically impossible to provide a single definition in the first place. My aim was different: to illustrate that context is vital when it comes to understanding obscure historical terms. Through history, shikigami evidently meant slightly different things to different people, as reflected in literature. However, this meaning was nonetheless consistently rooted in the evolving perception of onmyōdō - and its internal changes. In other words, it reflected a world which was fundamentally alive.

The popular image of Japanese culture and religion is often that of an artificial, unchanging landscape straight from the “age of the gods”, largely invented in the nineteenth century or later to further less than noble goals. The case of shikigami proves it doesn’t need to be, though. The malleable, ever-changing image of shikigami, which remained a subject of popular speculation for centuries before reemerging in a similar role in modern times, proves that the more complex reality isn’t necessarily any less interesting to new audiences.

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, A Religion in Search of a Founder?

Idem, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Makoto Hayashi, The Female Christian Yin-Yang Master

Jun’ichi Koike, Onmyōdō and Folkloric Culture: Three Perspectives for the Development of Research

Irene H. Lin, Child Guardian Spirits (Gohō Dōji) in the Medieval Japanese Imaginaire

Yoshifumi Nishioka, Aspects of Shikiban-Based Mikkyō Rituals

Herman Ooms, Yin-Yang's Changing Clientele, 600-800 (note there is n apparent mistake in one of the footnotes, I'm pretty sure the author wanted to write Mesopotamian astronomy originated 4000 years ago, not 4 millenia BCE as he did; the latter date makes little sense)

Carolyn Pang, Spirit Servant: Narratives of Shikigami and Onmyōdō Developments

Idem, Uncovering Shikigami. The Search for the Spirit Servant of Onmyōdō

Shin’ichi Shigeta, Onmyōdō and the Aristocratic Culture of Everyday Life in Heian Japan

Idem, A Portrait of Abe no Seimei

Katja Triplett, Putting a Face on the Pathogen and Its Nemesis. Images of Tenkeisei and Gozutennō, Epidemic-Related Demons and Gods in Medieval Japan

Mitsuki Umeno, The Origins of the Izanagi-ryū Ritual Techniques: On the Basis of the Izanagi saimon

Katsuaki Yamashita, The Characteristics of On'yōdō and Related Texts

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Tenma, boss of the tengu". Exploring the "heavenly demon(s)"

The identity of Tenma, the leader of tengu in Touhou, remains a mystery. I think only ZUN can solve it - if he ever chooses to, obviously. Therefore, this is not quite an article meant to prove I figured out who Tenma is. Instead, it presents the origin of this name, and introduces a handful of figures in various contexts portrayed as leaders of the tengu who I think would be interesting candidates for the position of Tenma.

My additional goal is to show that even though popculture tends to portray all tengu as basically interchangeable, there is actually a fair share of unique tales about specific named members of this category. Corrupt monks! Vengeful spirits! Visitors from far off lands! There’s even a sea monster converted to Buddhism! Obviously, this isn’t supposed to be a list of every single named tengu and every single story. It’s not even a list of all of my favorite tengu. It’s simply an attempt at convincing you that digging deeper into tengu background is worth it - and in particular that there is still a lot to speculate about when it comes to their leader in Touhou. It’s some of the best oc free real estate in the series, really.

Due to technical difficulties, the bibliography is included as a Google Docs link rather than a part of the article. I'm sorry.

From Mara to tengu: the development of the concept of tenma

Silhouette of a tengu negotiating with Kanako in WaHH 38, sometimes labeled as Tenma on fan sites through debatable exegesis.

As we originally learned in Perfect Memento in Strict Sense, Gensokyo’s tengu are ruled by an individual named Tenma (天魔). Akyuu simply describes them as the “tengu’s boss” and provides no further information. While some additional tidbits have since surfaced here and there, they largely remain a mystery. Next to Chang’e, the unseen fourth deva of the mountain and the fourth Beast Realm figurehead they’re easily the highest profile unseen character in the entire series.

While in absence of information on the contrary we cannot necessarily assume that Tenma isn’t a given name in Touhou, ZUN did not actually come up with this term. It has been a significant part of tengu background at least since the Kamakura period. It can be translated as “heavenly demon”, and it’s a shortened form of Dairokuten Maō (第六天魔王), “Demon King of Sixth Heaven”, the Japanese name of Mara. Tenma is explained as a synonym of Mara’s “personal name” Hajun (波旬; Sanskrit Pāpīyas) for instance in the treatise Makashikan (摩訶止観; translation of Chinese Móhē Zhǐguān, “Great Cessation and Insight”).

Is that all there is to the mystery of Tenma? For what it’s worth, a possible reference to the full form of Mara’s name can be found in a description of Okina’s ability card in Unconnected Marketeers, which mentions “Tenma living in paradise”. I don’t think this is very strong evidence, though.

Touhou aside, it is hard to deny tengu are fundamentally tied to Mara. They are directly described as his subjects in Buddhist works such as Soseki Musō’s (1275–1351) Muchū mondō (夢中問答集; “Questions and Answers in Dreams”) and Unshō’s (運敞; 1614–1693) Jakushōdō Kokkyōshū (寂照堂谷響集). However, it needs to be stressed that a being referred to as Tenma necessarily has to be Mara himself.

A plurality of Maras theoretically became possible as soon as the belief this name didn’t designate an individual, but rather a position which could be held by various individuals or a category of beings developed in Buddhism. The former idea already appears in the Māratajjanīya, a part of the Theravada Buddhist Majjhima Nikāya, dated to the late first millennium BCE or early first millennium CE. Maudgalyāyana, one of the disciples of the historical Buddha, reveals in it that he was (a) Mara in a past life, and thus can easily notice the presence of the present Mara. The shift from a singular Mara (魔, mo) to an assortment of “demon kings” (魔王, mowang) is also well documented in early Buddhist sources from China.

As a curiosity it’s worth noting that even though the terms mo and mowang originally referred to strictly Buddhist demons, they were also incorporated into Daoist traditions, especially Lingbao and Shangqing. For example the former school's central text Duren Jing (度人經; “Scripture for Universal Salvation”) maintains that multiple mowang exist.

While some of these “demon kings” are tempters not too dissimilar from their Buddhist forerunner (though what they obstruct is attaining the distinctly Daoist form of transcendence - in other words, immortality), others are portrayed as judges responsible for determining the fates of people in the afterlife. In later sources the term mo is sometimes refers to supernatural pathogens (generally 邪, xie or 邪氣, xiequi).

Sun Wukong and his fellow pilgrims battling the Bull Demon King on a mural from the Summer Palace in Beijing (wikimedia commons)

You don’t really need to look for any particularly obscure sources to see this transformation of Mara into a generic moniker, though - even the Bull Demon King from Journey to the West has the compound 魔王 in his name. Same goes for numerous other antagonists from this work.

When it comes to Japanese sources, it also doesn’t require looking for anything particularly obscure to find evidence in the belief in multiplicity of ma or tenma.

In the historical epic Heike Monogatari, emperor Go-Shirakawa implores Sumiyoshi Daimyōjin to explain the nature of tenma to him. He reveals that this term refers to monks and scholars who, despite nominally following Buddhism, lacked the mindset needed to attain enlightenment. He compares them to birds of prey, but also states they belong to the “dog species”. All of these are nods to well established beliefs about tengu, which I discussed in my previous article, with a reference to the writing of their name on top of that.

It comes as no surprise that right after that Sumiyoshi Daimyōjin specifies that “the wise men of the eight sects who become tenma are called tengu”. He also makes it clear the tenma are quite numerous: “nine out of ten will definitely become tenma and try to destroy the Law of Buddha,” he warns.

A plurality of tenma can also be found in assorted biographies of pious Buddhist reborn in a pure land, so-called ōjōden (往生伝). The Tendai treatise Asabashō (阿娑縛抄) attributes the ability to “subdue all tenma” - evidently a class of beings, not an individual - to Fudō Myōō.

Through the rest of the article, I will introduce some of these tenma - the most famous tengu. My goal is not to convince you that any of them is a uniquely plausible candidate for the role of the unseen Touhou Tenma - I merely would like to point out there are multiple interesting options.

The oneness of vice and virtue: Ryōgen, the ruler of Makai

The historical Ryōgen (left) and his deomic alter ego Tsuno Daishi (wikimedia commons)

Before Ryōgen (912–985) came to be seen as a tengu, he was one of the most influential members of the Tendai school of Buddhism to ever live. He reformed the Enryaku-ji complex on Mt. Hiei, took part in numerous theological debates, and gained the favor of the imperial court by supposedly enabling the birth of an heir of emperor Murakami with his prayers. He was also renowned as a master of esoteric protective rituals.

The proponents of the Tendai establishment understood him as a fearsome protector of this tradition. As early as 50 years after his death, in the 1030s, he came to be identified as the reincarnation of Tendai’s founder Saichō. He was also considered a manifestation of one of the eight dragon kings, Uhatsura (優鉢羅; from Sanskrit Utpalaka). Ōe no Masafusa states that in this form he continued to protect Mt. Hiei, instead of being reborn in a pure land. This idea continued to spread, and by the end of the Kamakura period he came to be commonly revered as a protective figure by all strata of society. Haruko Wakabayashi notes that only Kūkai developed a similar cult in Japan as far as patriarchs of the esoteric Buddhist schools go.

It was not Ryōgen’s ability to navigate complex doctrinal debates about the interpretation of sutras that resulted in his popularity, but rather his esoteric skills. He was supposedly uniquely accomplished when it came to subduing anything which could be described as ma. In a Konjaku Monogatari tale I’ll discuss in more detail later, he is portrayed effortlessly overcoming a tengu, for instance.

However, in addition to spiritual obstacles and demons, the ma he was supposed to conquer also included political opponents, rebels or brigands, as the Buddhist law and the interests of the state were understood as identical. Ryōgen’s efficiency was so great he came to be viewed as a manifestation of Fudo Myōō, one of the wisdom kings and the conqueror of ma par excellence.

Not everyone viewed Ryōgen positively, though. The earliest criticism came from his contemporaries. It was argued that he favored monks from aristocratic families, and that he lived in luxury unbefitting for a monk. Furthermore, numerous conflicts between monks erupted during his tenure as Enryakuji’s abbot, including the split between the Sanmon and Jimon lineages. Since in some cases this led to armed confrontations, later on he was blamed for essentially enabling the rise of militarized monks who commonly caused disturbances on Mt. Hiei.

The real breakthroughs were not these tangible “political” criticisms. Rather, it was the identification of Ryōgen as ma, which arose due to conflict between various schools of Buddhism in the early middle ages. Most commonly this meant portraying him as a tengu - as I explained in my previous article, the form arrogant or corrupt monks were believed to take. A variant tradition described him as an oni, though according to Bernard Faure this likely simply reflects a degree of interchangeability between them and tengu.

Ryōgen is arguably the most famous historical monk to be furnished with such a literary afterlife. An early example can be found in the Hōbutsushū from the twelfth century, which states that this was a result of his attachment to Enryaku-ji. In Jimon Kōsōki (寺門高僧記) it is instead his investment in doctrinal debates that made him unable to attain rebirth in a pure land.

A gathering of tengu leaders from Tengu Zōshi (wikimedia commons)

Since Ryōgen was no ordinary monk, his tengu self also had to be special. In the Tengu Zōshi (天狗草紙), he is described as the ruler of all tengu and the realm they inhabit, Makai (“world of ma”; also referred to as Tengudō). It's worth pointing out the notion of Makai being a place where monks turn into specific classes of supernatural beings is basically a core part of UFO’s plot, and in SoPM Miko even wonders if Byakuren shouldn’t be considered a tengu.

As a ruler of Makai, Ryōgen came to be referred to as a “demon king”, maō (魔王). An example can be found in the historical epic Taiheiki, where he is described as one of the “great demon kings” (大魔王, daimaō) who debate how to cause chaos in Japan. He is assisted by vengeful spirits of the emperors Sutoku (more on him later), Go-Toba and Go-Daigo; two members of the Minamoto clan who sided with Sutoku, Tameyoshi and Tametomo; and the monks Genbō, Shinzei (真済, 800-860; obscure today, but apparently well known as a monk turned tengu in the middle ages) and Raigō (who supposedly turned into the infamous “iron rat”).

In Hirasan Kojin Reitaku (比良山古人霊託; “The Spiritual Oracle of the Old Man of Mount Hira”) this is only a temporary fate, though: supposed by the time this work was compiled, he already managed to leave Tengudō. As I discussed last month, this reflects a fairly standard belief too: to become a tengu, one had to actually be a Buddhist, and while it made striving for enlightenment more difficult, it did not mean eternal damnation or anything of that sort. A tengu could still choose to pursue rebirth in a pure land - it was just more difficult than for a human.

The evolution of Ryōgen’s image didn’t end with the establishment of his new role as a king of tengu, or even with the arguments that he might have nonetheless subsequently attained enlightenment. By the end of the Kamakura period, he came to be worshiped explicitly in the form of a “demon king”. While initially polemical, this image of him came to be subverted by Tendai monks to their own ends. They asserted that Ryōgen did not enter the realm of ma because of his arrogance, but rather consciously chose to do so in order to protect Buddhist principles. By becoming the ruler of its inhabitants, he also became their ultimate conqueror.

The notion of a being who is simultaneously essentially Mara-like and a protector of Buddhism seems contradictory. That’s actually the intent here. Through the middle ages, the esoteric schools of Buddhism developed the notion of hongaku, or “original enlightenment”. In its light, opposites were in fact identical. Buddha was the same as Mara (魔仏一如, mabutsu ichinyo). As it was argued, to attain Buddha nature one had to understand and experience delusion as well. Thus virtuous individuals could become demon kings in order to freely control evil beings.

In addition to its deep philosophical implications, the hongaku theory was also used to reject criticisms of the Buddhist establishment. Enjoying luxuries was but a way to better understand delusion, and thus to advance along the path to enlightenment. Its proponents embraced some criticisms of Ryōgen: he did favor nobles, accumulate wealth and live arrogantly. He did become a powerful tengu. But all of this was in fact part of a noble goal. And on top of that, as a demon king he was an even more fearsome protector of Tendai than he would be otherwise.

"Tsuno Daishi and a snail" by Teisai Hokuba (Sumida Hokusai Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The new role of Ryōgen warranted new iconography. While formerly portrayed simply as a monk holding the expected priestly attributes, in the Kamakura period he came to be depicted as Tsuno Daishi (角大師), the “Horned Master”. This image spread far and wide due to the development of a belief that hanging depictions of Ryōgen would guarantee the same protection Tendai institutions received from him. He came to be seen as particularly efficient in warding off disease.

Many temples still distribute talismans depicting Tsuno Daishi today. This custom received a lot of press coverage in the early months of the COVID pandemic, and you might have seen some examples on social media.

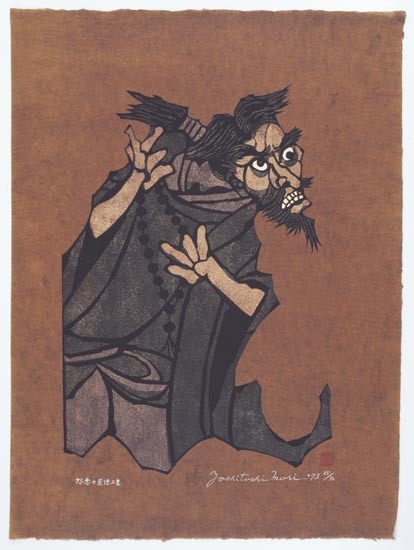

From vengeful spirit to tengu: the case of emperor Sutoku

Sutoku, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Mori (Tokyo's National Museum of Modern Art; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Sutoku has much in common with Ryōgen - he was also a historical figure who purportedly became a tengu. However, he was not a monk, but rather an emperor. He reigned from 1123 to 1142, when he was forced to abdicate in favor of his half brother Konoe.

Konoe passed away in 1155, but Sutoku was not allowed to return to the throne. It was instead claimed by another half brother, Go-Shirakawa. Sutoku decided that’s enough half brothers seizing a position he believed was still rightfully his, and plotted an uprising. This culminated in the Hōgen Disturbance of 1156. Alas, planning seemingly wasn’t his strong suit, since the conflict was essentially resolved before it even started. Go-Shirakawa’s forces defeated Sutoku’s before they even left their encampment.

Sutoku as a vengeful spirit, as depicted by Kuniyoshi Utagawa (wikimedia commons)

In the aftermath of his failed rebellion, Sutoku was exiled to Sanuki, where he eventually passed away in 1164. However, his memory lingered on. He most likely came to be widely perceived as a vengeful spirit after the great fire of Angen broke out in Kyoto in 1177. Other subsequent disasters, including the Genpei war (1180-1185) and the 1181 famine, strengthened the belief that he was punishing his enemies from behind the grave. However, he didn’t become just any vengeful ghost, but one of the three greatest members of this category ever, next to Sugawara no Michizane and Taira no Masakado.

Sutoku was, in a way, the sum of many of the greatest fears of medieval Japan. The belief in his rebirth as a vengeful ghost coexisted with a tradition presenting him as a tengu - arguably one of the greatest tengu ever. This status is firmly ingrained into his image in later sources.Today he is frequently included in modern groupings of “three great youkai” alongside Shuten Dōji and Tamamo no Mae. It seems sometimes he’s replaced by Kidōmaru, but honestly I think he is more worthy of this spot, and also even though this is ultimately a synthetic modern group, it’s much more representative of medieval culture to have a tengu alongside an oni and a fox.

A strikingly tengu-like vengeful Sutoku, as depicted by Yoshitsuya Utagawa (wikimedia commons)