Photo

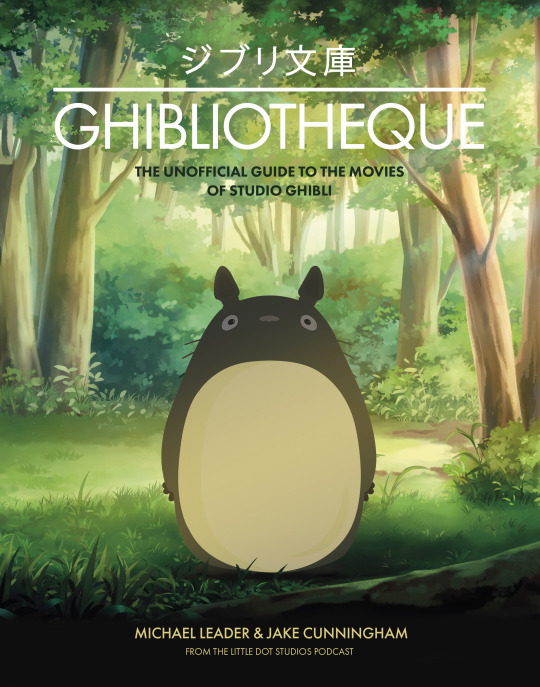

Letterboxd news is now on Journal.

From today, we’re transitioning our news and editorial coverage to our own website. You’ll find the entire Tumblr archive recreated over there, along with topic-based sections, author archives and more. From today, we won’t be publishing any further news on this blog. Please follow our new Journal RSS feed, if that’s your thing, or visit our new editorial homepage:

Journal—Letterboxd’s home for news and editorial coverage

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

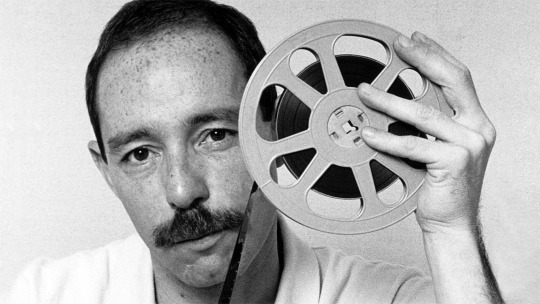

He Was Here.

On the anniversary of Vito Russo’s death from AIDS, filmmaker Jenni Olson remembers the activist and author, who helped so many—including Olson herself—crash out of the celluloid closet.

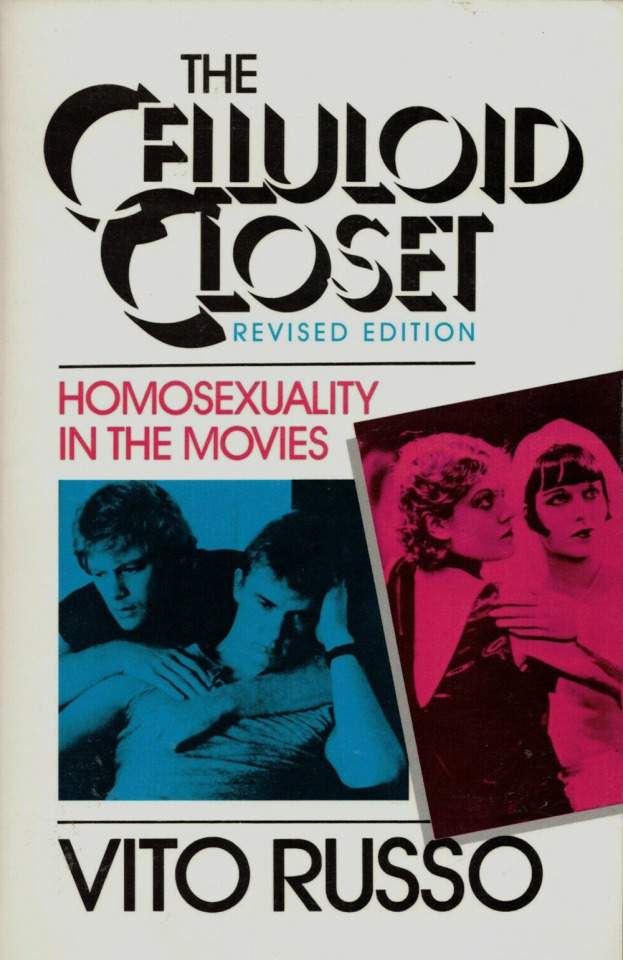

Back in 1986, when my film studies professor handed 23-year-old me a copy of Vito Russo’s book, The Celluloid Closet, little did I know how life-changing it would be. I would go so far as to say that Vito’s powerfully written analysis of the history of homosexuality in the movies actually saved my life.

First published in 1981, The Celluloid Closet covered the history of LGBTQ representation on screen since the dawn of motion pictures. Vito wrote about films as far back as Richard Oswald‘s 1919 Anders als die Anderen (Different from the Others), the German film considered to be the first gay feature, and Mädchen in Uniform, the beautiful and surprisingly political 1931 German drama considered to be the first lesbian feature.

Covering more than a hundred movies, the book spanned all the Hollywood stereotypes: the proto-gay sissies like Franklin Pangborn and Eric Blore in the 1930s; the creepy coded predatory lesbians of the 1940s and 1950s (like the prison matron in Caged); sensational trans depictions like I Want What I Want and The Christine Jorgensen Story, and half-lurid, half-comical bisexual tales such as A Different Story.

Vito revisited the book towards the end of the 1980s, incorporating some more recent achievements of the time, like the Academy Award winning documentary, The Times of Harvey Milk and beloved LGBTQ indie classics like Donna Deitch’s Desert Hearts and Bill Sherwood’s Parting Glances. (There is, naturally, at least one Letterboxd list of all the films in this revised edition.)

When The Celluloid Closet landed in my hands, I had been miserably stumbling along in college, and in life, for the previous five years. Vito’s book was the catalyst for my coming out to myself as queer (I wanted to see all those movies he wrote about) and for coming into the LGBTQ community (I imagined everyone else might want to see those movies too).

And so, despite having zero experience in how to do it, I started a weekly queer film series on campus, which brought hundreds of people out to the movies each Wednesday night. While there were certainly LGBTQ stories being told on screen in 1986, it was still an era where these films were much harder to access. Some were shown on television or available on VHS tape, but often these films had to be seen at film festivals or arthouse theaters.

The very first films I programmed in that series included some titles that remain among my favorite LGBTQ movies of all time: the aforementioned Mädchen in Uniform; the wonderfully romantic, 1968 French schoolgirl drama Therese & Isabelle; and jumping ahead to the indie gay films of the 1980s, Arthur J. Bressan’s devastating AIDS drama, Buddies (1985).

A few years later (with my University of Minnesota film studies BA in hand), I jumped in to become co-director of Frameline in San Francisco, the oldest and largest LGBTQ film festival in the world, and carved out a queer corner of the internet for movie lovers, co-founding the massive LGBTQ movie database, PopcornQ (aka “the gay IMDb”) as part of the world’s first major LGBTQ website, PlanetOut.

Along the way, I also worked as a queer-film critic, queer-film historian, queer-film collector, queer-archival researcher, queer-consulting producer (most recently on Sam Feder’s acclaimed overview of trans lives on screen, Disclosure), and spent a decade driving the marketing efforts of the oldest and largest LGBTQ film distributor in North America (Wolfe Video). And I made some films myself. (Yes, there is a Letterboxd list!)

At some point, Vito and I became friends. More than that, he became my mentor. He instilled in me a passionate belief in the power of LGBTQ cinema; in all the ways that films can give us the support and compassion, the inspiration and validation, the respect and dignity, the complexity and nuance, the joy and entertainment that we need and desire. And yes, even the messy and fucked-up representations, too. (Be gay, do crime, etc.)

Vito died of AIDS on November 7, 1990. As the 31st anniversary of his passing approaches, I’ve been thinking a lot about leadership, both personal and collective, and how we make positive change.

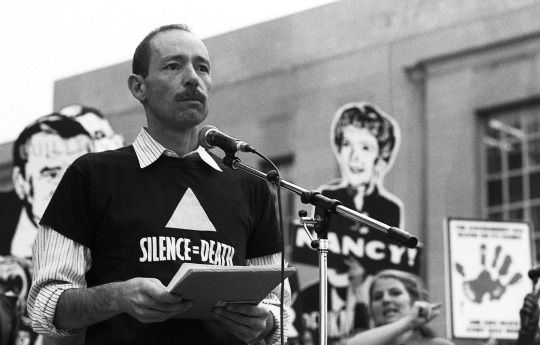

In addition to his groundbreaking work on that life-changing book, which was made into the tremendous, must-see 1995 documentary The Celluloid Closet, Vito had long been an important gay activist in New York City, eventually co-founding ACT UP in 1987.

Russo with Bette Midler at the 1973 Gay Pride Rally in Washington Square Park, New York.

Vito was also one of the founders of GLAAD, the US-based LGBTQ media advocacy organization dedicated to (among many other things) improving LGBTQ representation in film and television. Since 1985, GLAAD has had an enormous impact in transforming the on screen landscape with regard to LGBTQ characters and stories, cast and crew, coverage and visibility of queer cinema.

This year—this is such a beautiful and deeply moving thing for me—Vito’s mentorship came full circle. I now work for GLAAD. It is my actual job, every day of the week, to carry on his legacy.

As director of our Social Media Safety program, I advocate for LGBTQ user safety around content moderation, data privacy, problematic algorithms and other forms of tech and platform accountability (yes, including Letterboxd). I also get to be involved in some of GLAAD’s other media advocacy work.

One of the most impactful things that GLAAD produces each year is the Studio Responsibility Index, which evaluates each of the major Hollywood studios and serves as a road map toward increasing fair, accurate and inclusive LGBTQ representation in film. There’s an equivalent publication covering the television industry: the Where We Are On TV report.

GLAAD’s most public media advocacy work is the annual GLAAD Media Awards, honoring fair, accurate and inclusive representations of LGBTQ people and issues in film, television and other media. (Submissions are open until December 7, 2021—if you’ve made something, make sure we know about it.)

Every year the event honors Vito’s legacy with the presentation of the Vito Russo Award to an openly LGBTQ media professional who has made a significant difference in promoting equality for the LGBTQ community. Recent recipients include George Takei, Billy Porter, Samira Wiley and Ryan Murphy.

In an interview with Making Gay History author and podcast host Eric Marcus, Vito talked about the legacy he wanted to leave, citing Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar.

“He said, the thing is, is you can’t regret your life, otherwise why did you live? What was the point of having a life if you didn’t say something or do something that was gonna survive after you’re gone… I really feel the reason why I’m here is so that I could leave this book and these articles so that some sixteen-year-old kid who’s gonna be a gay activist in the next ten or fifteen years is gonna read them and carry the ball from there.”

I love the thought of how amazed Vito would be if he could see what LGBTQ representation on the big screen looks like today compared to where we were when GLAAD was founded 36 years ago—in large part because of his leadership.

Let me just shout out a few Letterboxd lists that so vividly illustrate this point: Intersex, LGBT POC, Films featuring LGBTQ characters/folks with disabilities, LGBT+ films from Southwest Asia and North Africa, TRANS, South Asian LGBT, Directed and/or written by transmascs and trans men, Todos Me Miran: The Queer Latinx Experience. And hey, if the movie list you want—or indeed the movie—doesn’t exist yet, may this be the inspiration that prompts you to create it.

Activist and author Vito Russo. / Photo by Rick Gerharter/HBO Documentary Films

You can learn more about Vito in Jeffrey Schwarz’s beautiful 2011 documentary, Vito. And, you could begin applying GLAAD’s Vito Russo Test to your movie-watching habits. Briefly: a film must include an identifiable LGBTQ character; who is not solely defined by their sexual orientation or gender identity; and, the character must matter to the plot. This short video on GLAAD’s YouTube channel explains it more—there are already many Vito Russo Test lists scattered across Letterboxd.

Lastly, follow GLAAD’s brand new Letterboxd HQ account, where you can discover some of the best LGBTQ films of the past few decades via our lists of GLAAD Media Award Winners. A quick name drop of a handful of those honorees over the years just to whet your appetite: The Wedding Banquet, Pariah, Go Fish, Brokeback Mountain, Moonlight, The Incredibly True Adventures of Two Girls in Love, Call Me by Your Name.

Grazie, Vito!

Related content

World AIDS Day is December 1—Here’s a Letterboxd list of films that ensure we never forget.

Rebel Dykes, a documentary mash-up of animation, archive footage and interviews about a radical lesbian subculture in 1980s London, opens in UK and Irish cinemas from 26 November (US release TBA)

All the Good Boys: Schlockvalues’ essay for Letterboxd on the real roots of queer cinema and the evolution of gay masculinity on screen

14 notes

·

View notes

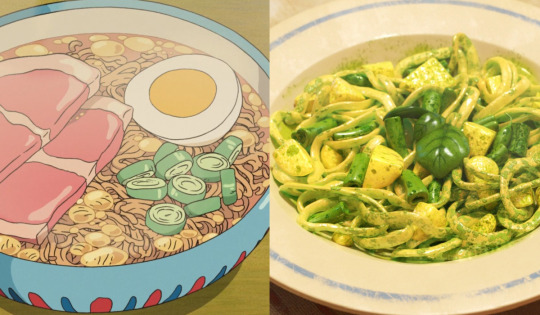

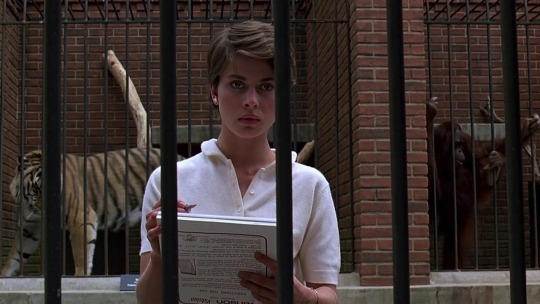

Photo

Free Form.

London correspondent Ella Kemp talks to The French Dispatch and No Time to Die star Léa Seydoux about being part of Wes Anderson’s “little troupe”, the best Parisian films, and baring it all.

“I’ve always thought that showing your emotions can also be very disturbing. In front of a camera, I always feel naked.” —Léa Seydoux

The first thing you notice about Léa Seydoux in Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch is, well, all of her. She appears in the first of the film’s three chapters as Simone, a prison warden, who develops a curious relationship with inmate and painter Moses Rosenthaler (a beguiling Benicio Del Toro). It’s a striking role that stands out in a film defined by just how many different moving parts it has.

She is also a stand out—the beating heart, really—in No Time to Die, Daniel Craig’s last turn as James Bond. As psychologist Madeleine Swann, Seydoux makes history by holding on long enough as a Bond girl (alive and kicking at the end of 2015’s Spectre) to make it into the follow-up film (and therefore benefit from a Bond girl rarity: further character development).

History-making is a habit: in 2013, Seydoux and her Blue Is the Warmest Color co-star Adèle Exarchopoulous became the first actresses to be awarded a Palme d’Or, alongside their director Abdellatif Kechiche. The three-hour romantic odyssey was notorious and somewhat divisive for its intense, exhaustive sex scenes and reports of less-than-enjoyable working conditions for its stars, and the Cannes jury saw fit to include “all three artists” in its decision.

Léa Seydoux as Madeleine Swann in ‘No Time to Die’.

Which leads us back to Simone and The French Dispatch. Seydoux’s only clues about her character were a handful of lines, which, considering so much of Simone’s aura is conveyed through body language, can’t have given much away. She started to get the sense of the story after travelling to Angoulême, where Anderson had already begun filming, to hear from the magician himself.

Having worked with Anderson before, as Clotilde in The Grand Budapest Hotel, Seydoux was ready for the moment he presents his cast and crew (she calls them “a little troupe”) with intricate, animated films to offer a précis on the world they’re about to build. “He does all the voices and they’re absolutely stunning,” the actress explains. “It was then that I realised how beautiful and poetic this character was.”

Beautiful, poetic, and, without spoiling the impact of her first frame, quite starkers. Simone’s is a scene that, even in such a formally composed film as this, raises questions yet again about the way we—the audience, the director, the painter—look at the female body on screen. Who chooses how close we get? How long we linger? And how does the woman whose body is being observed feel about it all?

“I didn’t necessarily feel confident,” Seydoux says when asked what gave her the faith that she would be in safe hands for such a revealing role. “It’s not necessarily comfortable to be naked in front of the camera, but it’s also not necessarily comfortable to act. I’ve always thought that showing your emotions can also be very disturbing. In front of a camera, I always feel naked.”

Benecio Del Toro (center) as Moses, and Seydoux (right) as Simone in ‘The French Dispatch’.

Still, it is always curious to consider how it comes to be that certain roles require baring oneself more than others, and how certain actors come to choose those roles—particularly in the time of intimacy coordinators, safety considerations, and film-industry campaigns for equality and diversity such as Collectif 5050x2020, of which Seydoux is a founding signatory.

“I know it’s something that exists, but we don’t really have intimacy coordinators in France,” Seydoux says of her experience working in such delicate environments. She explains that she always approves of the scene after filming by watching it back on the monitor herself, but then shrugs, “That’s all.”

But that’s not all. With a few minutes left of our chat, we questioned Seydoux on some of her movie loves. Her answers reveal favorite female muses, visionary auteurs, and why she chose a life in front of the camera.

What’s your favourite Wes Anderson film?

Léa Seydoux: The Royal Tenenbaums.

Could you give us a few films set in France that you feel honor the country beautifully?

I love The 400 Blows, it’s so beautiful. But there are so many wonderful films set in Paris. I love Éric Rohmer’s films, and there’s one set in Paris called Love in The Afternoon, which is beautiful.

Who is your favorite “female muse”?

I love Anna Karina as an actress, but also as a muse and an actress I love Elizabeth Taylor. A Place in the Sun is my favorite.

What is your favourite black-and-white movie?

The Kid by Charlie Chaplin.

And your favorite James Bond film?

Casino Royale.

Which contemporary filmmaker do you think and hope might have a similar legacy to Wes Anderson, in terms of having an unusual artistic vision?

Joachim Trier.

What was the first film that made you want to be an actress?

I don’t think I want to be an actress! No, to be honest, I didn’t want to become an actress because I saw a film. It was more actors who made me want to be an actress, because I just wanted to be my own master. And I loved the fact that actors were very free in the sense that they can choose whatever they want. It was because I wanted to be free that I became an actress.

Related content

Sarah Williams’ list of feature-length French films by women

After Agnes: Ten French Filmmakers to Watch in 2021

Paris, Je T’Aime: the Letterboxd Showdown of the best films set in or about Paris

‘The French Dispatch’ and ‘No Time to Die’ are screening in cinemas in the US, UK and further countries now.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

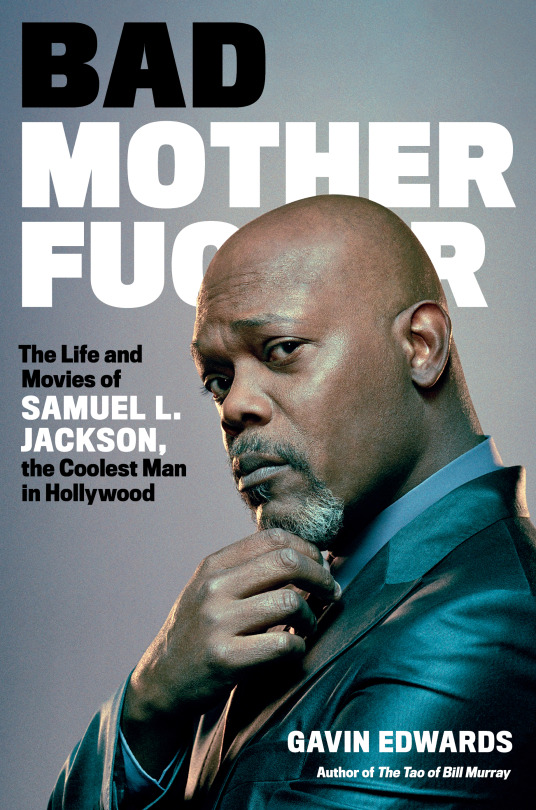

One Good Motherf**ker.

Editor-at-large Dominic Corry introduces an exclusive excerpt from Gavin Edwards’ new book about the life and work of Letterboxd’s most-watched actor, and the Samuel L. Jackson films we never got to see.

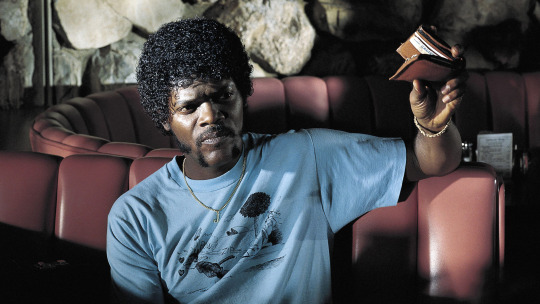

Like his wallet in Pulp Fiction reads, Samuel L. Jackson is a bad motherf—ker. In a good way. He’s about the coolest damn actor wandering the Earth these days, and he’s unleashed that cool in more than a few films, 140-odd in fact. And you watch a lot of them. For almost every year of Letterboxd’s first decade, Samuel L. Jackson has been the Most Watched Actor in our Year in Review.

But don’t just attribute that to his presence in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, in which he plays the semi-ubiquitous Nick Fury—he still wins even when we exclude his cameo roles. Jackson’s complete and total dependability sees him in constant high demand because he always delivers, in a wide range of genres.

Relentlessly versatile while always giving you something familiar, he balances movie-star charisma and consistency with character-actor panache. His stage-trained projection brings gravitas to every performance, but Jackson somehow never pushes it over the top.

He’s also really good at saying “motherf—ker” and its variations (a long list of every utterance can be found here), so much so that Snakes on a Plane famously staged reshoots to satisfy test-audience demands that Jackson utter the expletive in the movie.

He said it 21 times as the splendidly serpentine Ordell Robbie in Jackie Brown in 1997, and twenty times in the 2019 Shaft movie. He almost ran it into the ground by making “a thing” out of saying the word in The Hitman’s Bodyguard (nineteen, most with a wink), but Jackson has enough goodwill by this point to forgive such transgressions. Here’s to many motherf—kers more.

So it makes sense that Gavin Edwards’ new book about Jackson’s life and career is titled Bad Motherf—ker. In addition to a deep dive into all of Jackson’s performances, Edwards also lays out some of the roles he came close to taking, but didn’t (Jackson as Buck in Boogie Nights!? It could’ve happened!), and some other Samuel L. Jackson projects that never got made at all. Speaking of which, we’re still waiting for that long-promised Blob remake, Sam.

Some of those fascinating what-ifs (Michael Caine as butler to Jackson’s jazz musician in New Orleans!?) are covered in an exclusive excerpt from Edwards’ book, reproduced below courtesy of Hachette Books, along with details of Jackson’s involvement in the bizarre animated epic Quantum Quest: A Cassini Space Odyssey, which, despite boasting a bunch of huge names in the voice cast, hasn’t really been properly released in English-language territories. “Someone needs to find this ASAP,” demands Mody. The excerpt indicates that Netflix and Amazon have shown interest, so maybe exposure in this book can inspire a streamer to finally put it out there. We’d like to see it. (You can watch the trailer, at least.)

Jackson couldn’t be in every single movie that got released, but it wasn’t for lack of trying. His appetite for work being what it was, and Hollywood being the fickle type of industry that it is, he was attached to plenty of projects that got announced but never happened.

A handful of the most intriguing: Truck 44, about firemen who rob a building by setting fire to it, was canceled after 9/11. In the comedy Man That Rocks the Cradle, Jackson would have played a live-in nanny. Black Phantom would have starred Jackson and Kevin Hart as double-crossing hit men. George C. Wolfe wanted to direct an update of the 1961 Danish film Harry and the Butler, where Jackson would have played a New Orleans jazz musician and roller-coaster mechanic who falls on hard times and lives in a converted train caboose—but when he inherits a big chunk of money, he hires an out-of-work British butler (Michael Caine).

He also turned down some movies that went on to be hits with other actors, such as Kiss the Girls, a thriller where Morgan Freeman ultimately costarred with Ashley Judd. “Too misogynistic,” Jackson said. Paul Thomas Anderson invited Jackson to play Buck Swope in Boogie Nights, but Jackson had already committed to another film; the role went to Don Cheadle (who also starred in Hotel Rwanda when Jackson passed on that script). Jackson was attached to The Matrix for years but got tired of waiting for the Wachowskis to make the movie happen, so he took other work; when he was unavailable, they cast Laurence Fishburne as Morpheus.

Weirder than any of those never-happened projects was an animated film that was over a decade in the making (and depending on how you think about it, still might not be finished): Quantum Quest: A Cassini Space Odyssey. Co-director Harry Kloor was a double PhD (in physics and chemistry) who had a personality better suited to Hollywood than the academy; he touted his multiple black belts in modern martial arts and his Nissan 300ZX Twin Turbo sports car. Kloor wrote for the TV show Star Trek: Voyager—and in 1996, he was approached by NASA and JPL to see if he could make an educational film about the Cassini-Huygens mission (a probe, launched in 1997, that ended up in orbit around Saturn to collect massive amounts of data on the gas giant and its rings).

Samuel L. Jackson as Nick Fury in the MCU.

The NASA boffins wanted to do a movie about the journey of a photon, taking a million years to go from the core of the sun to the surface, then eighty-seven minutes to travel through space to bounce off Saturn and reach the Cassini probe. Kloor convinced them that while they might be fascinated by this journey, it wouldn’t particularly appeal to kids: Why not turn the photon and other scientific concepts into colorful characters and make an animated movie? NASA bought the pitch, giving him $100,000 in seed money.

Kloor wrote a script for a sixty-five-minute educational movie, called Quantum Quest, about the adventures of Dave the Photon; working all his contacts and leaning hard on the educational angle, Kloor recruited an improbably high-caliber cast of Hollywood talent who worked for scale, recording voice performances for under a thousand dollars each, including John Travolta, Christian Slater, Sarah Michelle Gellar, James Earl Jones, and Samuel L. Jackson. Then NASA revised their plans: they wanted the movie to incorporate actual images from the Cassini-Huygens mission. The probe wasn’t reaching the neighborhood of Saturn until 2004, however, and it would take years to get usable data after that. Essentially, Kloor said, they wanted him to wait a decade before he made the movie.

So Quantum Quest went into hibernation until 2007, when Kloor recruited a co-director experienced in animation, Daniel St. Pierre, and found a studio in Taiwan called Digimax that provided a substantial production budget. Kloor gave the seed money back to NASA with a return on investment. “It’s the only project NASA’s ever made a profit on,” he bragged. “They put a hundred K in and they got two hundred K back, and for years, they kept calling me to say, ‘Something’s gone wrong, because we got more money.’ ”

Digimax had no animators, so St. Pierre spent many months in Taiwan, teaching its employees the necessary skills, “training a studio to make this film.” The company wanted to do a full-length feature, so Kloor heavily revised his script, expanding it to around one hundred minutes. That meant returning to his actors a decade later and asking them to record new dialogue: most declined (or were never even told about it by their agents). Undeterred, Kloor recruited a second cast, including William Shatner, Mark Hamill, Jason Alexander, Amanda Peet, and Chris Pine. Jackson was one of the few actors to stay with the project.

“Unlike a lot of other people, Sam immediately said, ‘Yeah, I’ll do it,’” Kloor said. “I think Sam truly cares about kids and he loves science fiction.” In both versions of the script, Jackson played a character called Fear, a sentient embodiment of antimatter and the general of the armies of evil, in the service of a villain called the Void. Jackson was agreeable and generous on the day he came to do his voice recording—although he did nickname St. Pierre “Four Eyes” and mock Kloor mercilessly when the writer made the mistake of suggesting a line reading.

Samuel L. Jackson’s ‘Quantum Quest’ character, Fear, a “sentient embodiment of antimatter”.

Back in Taiwan, the filmmakers edited the material together and worked on character design. St. Pierre said, “The way Sam played Fear was quite serious; he has a sharp, thorny aspect to him. So we put these spikes that could grow out of his shoulders and back and the more excited and agitated he got, the more these spikes would grow.”

They were about to start animating Quantum Quest when St. Pierre was called into an executive meeting: Digimax wanted to cut the movie down to forty-three minutes. (Digimax was funded by the Taiwanese government; as far as Kloor and St. Pierre could tell, the company fell victim to local politics and had its budget unexpectedly slashed.) They cut the movie to the bone, ending up with forty-nine minutes plus credits. Digimax had the distribution rights in Asia and released the movie there: St. Pierre and Kloor believe it did well in those territories but have no hard data.

In the United States, they had an odd property: a star-studded movie too short to play multiplexes but not educational enough to be booked at most science museums. And the animation, reminiscent of the video game Skylanders, was uneven at best. “The Taiwanese team rose to the occasion to the best of their ability,” St. Pierre said. “I have nothing bad to say about the artists and technicians.” In one more feat of recruiting, they signed up Jon Anderson (of the band Yes) to perform the movie’s theme song, “Sing.”

The movie played at a few IMAX theaters, including the screens at the Saint Louis Science Center and the Kentucky Science Center, and then vanished, although it remained available to be booked by educational institutions. Kloor says the movie’s target audience is “kids in the third, fourth, fifth grade—or college students who are stoned.” In the streaming era, Quantum Quest became newly valuable and Kloor has been approached about getting it onto Netflix or Amazon—maybe even restoring it to its intended length. “It would cost a fraction of what people normally spend to have a full-length feature,” he pointed out.

The Cassini probe was destroyed in 2017, burning itself up in the upper atmosphere of Saturn so it wouldn’t contaminate any of the planet’s moons. If Quantum Quest ever gets completed as a feature film, it will have had a journey even longer than the plutonium-powered orbiter. Its saga is a useful reminder that every single movie Jackson has appeared in has required extraordinary effort by countless professionals across a period of years, which makes it even more extraordinary that he’s been in over 140 of them.

Samuel L. Jackson in ‘Snakes on a Plane’ (2006).

Years later, St. Pierre still remembered the advice Jackson gave kids when the filmmakers interviewed him on camera. “Read as much as you can, whatever you can, all the time,” Jackson said. “Fill your mind with thoughts and ideas and other people’s words and philosophies.”

The reason Samuel L. Jackson liked to read was the same reason he liked to act: it was escapism that took him away from his own too-familiar identity, at least for a little while. So he was an avid reader his entire life, favoring science fiction and thrillers and comic books.

Phil LaMarr, who appeared with Jackson in Pulp Fiction, periodically ran into his fellow actor at the Golden Apple comic-book shop in Los Angeles.

LaMarr remembered a day when he was browsing in the adult section of Golden Apple, with his back to the curtain that separated it from the kid-friendly titles. He was interrupted by a familiar voice: “A-ha! Caught you!”

“Oh, goddamn you,” LaMarr thought when he turned and saw Jackson. “When you’re looking at the Milo Manara stuff, you’re not really in a conversational mode.”

The store’s main room, on the other side of the curtain, contained a full array of superhero comics, including Marvel titles that featured Nick Fury. Jackson was fourteen years old in 1963, when Fury debuted in Marvel comic books in Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos #1.

Nick Fury had an eye patch; he chomped on cigars; sometimes he led a squadron in World War II and sometimes he commanded the immensely powerful spy agency SHIELD. But whether he was drawn as a square-jawed war hero by Jack Kirby or with secret-agent op-art stylings by Jim Steranko, he was a white guy. When the character appeared in a TV movie that aired on Fox in 1998, Nick Fury: Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., he was played by David Hasselhoff.

That changed in 2001, when Nick Fury appeared in Marvel’s Ultimates line, wherein Marvel rebooted their entire continuity, discarding decades of storylines and reimagining favorite characters.

From ‘Bad Motherfucker: The Life and Movies of Samuel L. Jackson, the Coolest Man in Hollywood’ by Gavin Edwards, courtesy of Hachette Books, on sale now. For more on ‘Quantum Quest’, see the film’s website.

#samuel l jackson#pulp fiction#nick fury#marvel studios#marvel cinematic universe#mcu#bad motherfucker#letterboxd#agent of s.h.i.e.l.d.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fårö and Away.

Away from the breathtaking island of Fårö, Letterboxd’s East Coast Editor Mitchell Beaupre speaks with Bergman Island filmmaker Mia Hansen-Løve about all things Bergman, finding the balance between your art and your relationships, and the sex appeal of Elliott Gould.

“I think one of the first things that made me love the films of Bergman is the way he films women, actually… Who can pretend to have filmed women better than he did?” —Mia Hansen-Løve

Fårö, an island in the Baltic Sea off Sweden’s south-eastern coast, is a popular summer vacation spot, with its own language (a dialect of Gutnish called Faroymal). It was also the home of the great filmmaker Ingmar Bergman, who fell in love with the island once he set foot on it in 1960. He made many films there, including Through a Glass Darkly, Persona and Hour of the Wolf, eventually staying there for the final years of his life, until his death in 2007.

Since his passing, Bergman’s estate on Fårö has been turned into an artists’ retreat where guests can now visit and stay at the place Bergman called home. There you can visit the Bergman Center, a cultural destination for those seeking to celebrate the filmmaker’s art and life. Each year, the center hosts a five-day event called Bergman Week, where films are screened alongside discussions, music and lectures. Special guests for Bergman Week over the years have included Yorgos Lanthimos, Harriet Andersson, Greta Gerwig, Noah Baumbach, Tim Roth and Mia Hansen-Løve (writer and director of Goodbye First Love and Things to Come).

Hansen-Løve’s affinity for Fårö and for Bergman’s work made the island the natural location for her latest feature, appropriately titled Bergman Island. The film stars Vicky Krieps as Chris, a filmmaker who arrives on Fårö with her husband Tony (repeat Fårö visitor Tim Roth). Tony is the more accomplished filmmaker of the duo, and is being showcased on the island. As their time there continues, Hansen-Løve blurs the line between fiction and reality for both the audience and the characters, charting a metafictional course that sees Chris’ art inspired by her life, just as Bergman Island is inspired by Hansen-Løve’s.

Mia Wasikowska and Anders Danielsen Lie in ‘Bergman Island’.

After a rocky production, which saw actors Greta Gerwig, John Turturro and Owen Wilson all cast in the leading roles at various points before having to drop out, Bergman Island made its premiere at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, before going on a run that included stops at Telluride, TIFF and NYFF.

With its fondness for Bergman permeating through each scene, and a cast that also includes Mia Wasikowska and Anders Danielsen Lie, “this one is surely for the Letterboxd users”, Ethan writes in his review. A look through other reviews proves Ethan’s statement largely correct. Ash appreciates the way Hansen-Løve finds inspiration from Bergman to tell her own story, as opposed to being a more direct homage. For Jervis, it was “everything I love in art”. And, of course, it must be said: this has truly been quite the “big year for Vicky Krieps and beaches”.

As Bergman Island at last reaches audiences beyond festivals, Hansen-Løve sat down with Mitchell Beaupre to discuss her relationship with Bergman’s work, with Fårö itself, and how this film allowed her to reach a new level of maturity in her filmmaking.

What was the first Ingmar Bergman film you saw, and what was your response to that introduction to his work?

Mia Hansen-Løve: I think I was in my twenties when I first saw films by him. There was a retrospective of his work at an old historical cinematheque in Paris. The very first one I saw was Summer with Monika, one of his early films. The Nouvelle Vague guys at that time elected that film as being the symbol of modern cinema because Bergman was filming young people in love in a way that was different to what had been shown on film before then.

It wasn’t shot in Fårö, I think it was shot in the archipelagos of Stockholm, but he was shooting outside locations, which was also quite unique. It was breaking all the rules in terms of what cinema was doing, in terms of how these young characters were living, and especially about the way he filmed women. I think one of the first things that made me love the films of Bergman is the way he films women, actually.

Director Mia Hansen-Løve on the set of ‘Bergman Island’.

Some people have felt that Bergman Island suggests Bergman was a bit sexist, but you actually feel quite the opposite.

Yes, the comments in my film on the way he behaved with his kids has led to people thinking I’m criticizing his relationships with women, but I actually admire him for being one of the directors who filmed the most beautiful portraits of women ever in cinema. Who can pretend to have filmed women better than he did? That’s one of the things that makes his films so significant to me—how much importance he gave to women at a time where most directors were giving that space to men in their films.

That would be enough, but then his films take up such a big territory for me because he’s made so many films, and all of them are made with the same independence and freedom. He wrote all of his films, and they all came from his desire to express something. They were never imposed from the outside. Few directors ever reached that same degree of integrity and independence, and I admire that so much.

Was there anything about his relationship with Fårö that connected with you personally?

He wasn’t the most social person, and that’s something that attracts me somehow in terms of his relationship with the island and what that means when it comes to loneliness. I cannot afford to live the way he did. I have a kind of life with family and obligations that make it impossible for me to live on a remote island. I wouldn’t want to live like that because I don’t have the strength, but I do admire that way of living, as he did for the last twenty years of his life.

You’ve said that while you don’t have a favorite Bergman film, you do have a special relationship with his 1971 film, The Touch. That’s a unique pick. What makes that film stand out so much for you?

I think it has to do with the fact that it’s not a cerebral film of his. It’s a film that I find very direct, very innocent, especially compared to other films he made in the same period. As a young director he made those films like Summer with Monika that were more direct, and also very sensual, and focused on love, relationships, passion, and things like that. But afterwards his films were more complex, and would tackle more aesthetic quests, more formal quests.

The Touch isn’t one of his most famous films. It’s been quite forgotten, and Bergman himself didn’t like it for some reason. What I like about it so much, though, is its simplicity. I find the film extremely sincere and incarnated. The presence of Elliott Gould in the film—an American actor—allowed Bergman to explore things about sexual relationships that he wouldn’t be able to say with his regular Swedish actors.

Elliott Gould and Bibi Andersson in Ingmar Bergman’s ‘The Touch’ (Beröringen, 1971).

There is certainly an innate sexuality that comes into play once you bring Elliott Gould into the mix.

He brought something in from the outside, with his American culture, his presence, charisma, sex appeal or whatever you call it, that was actually telling something from the inside to me. It’s very paradoxical, but I feel that Elliott Gould enabled Bergman to say something more about himself that his other films couldn’t say. There is something brutal and animalistic about him in the film, and I think that reveals something about Bergman himself. That actually moves me a lot, for some reason. The film touches me. I saw it again a few days ago, and it still has the same power for me.

It reminds me of some of Truffaut’s films that are about the power of passion in your life, and how it takes up all the space. The film shows that brutality of passion. I find that extremely powerful and beautiful, and I don’t know any other film of Bergman’s that’s like that.

Bergman Island focuses on two filmmakers who are in a relationship, and it makes interesting observations on the kinds of boundaries you have to set to be able to create while also being in a relationship with another person. It’s a difficult balance to navigate.

What I wanted to do with this film was to show the difficulty, and also maybe the beauty, of being in a couple where both are writers, or artists. They both have their own quest, yet they’re still trying to be together. What does it mean to be together and at the same time lonely? How do you find the balance between this necessary loneliness that comes with being an artist? Bergman incarnates that so perfectly—the loneliness, but also the power that comes with the solitude of an artist.

On the other hand, most human beings want to be in a couple because they want to have an exchange. They want to have a dialogue. They want to feel close to somebody. They want love. These are very universal, and human feelings that anybody can understand, but then how can you cope with that solitude of the artistic quest? My film really tries to deal with that.

Vicky Krieps and Tim Roth in ‘Bergman Island’.

While the film is told from Chris’s perspective, there’s still a dimensionality to the portrayal of Tony, where he’s never seen as a villain, or an antagonistic force against her.

I don’t think the film wants to judge anybody. I didn’t make the film in order to go against the male character. I know there is more empathy in the film for her, because it’s more of a portrait of her, so we understand her more than him. He is more distanced from her, and that distance becomes more and more as the film goes on, as we get closer to her. I’m aware of that, but I never made the film against him. At the end, they are still together. I just wanted to show the difficulty and the vulnerability that comes when you are together, but lonely at the same time.

Navigating that relationship in the film must have been a little tricky, considering the production difficulties. You had several actors set to play Tony who dropped out, leading to you shooting half of the film with just Vicky Krieps, and not even knowing who was going to play Tony yet.

There was, of course, a challenge to shoot like this—to shoot only half of the film, and then have to wait to shoot the other half. We were editing certain scenes without even knowing who was going to play the husband. It was a little bit insane, a bit schizophrenic.

While it was challenging in some aspects, was there also a surprising benefit to doing it this way? Particularly given the nature of the film?

Yes, I think it’s a film that from the start was meant to take time. I’ve had this idea in my mind for more than ten years. Even before knowing I would set it on Fårö, the idea of making a film about a director couple was with me as I was doing other films. I let that film grow by itself until I found the idea of setting it on Fårö. It feels fitting that it would take me two years to shoot the film, and I’d have to leave and go back there.

I ended up going to Fårö each year for four or five years. I spent months on the island. I know every inch of the island now. I think that was part of the project. That’s the time I had to let pass in order to finish the film. That took a lot of patience, and that patience brought a maturity to the film. There is something peaceful and quiet about this film that makes it a bit different from my previous films.

Related content

Velma’s list of Scandi Films

Ingmar Bergman’s Fårö Island—a list of Bergman films shot on the island

Calvin’s list of Fårö Island filmography

Follow Mitchell on Letterboxd

‘Bergman Island’ is playing in US theaters now, and will be available on VOD from October 22.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Reservation Roots.

For Indigenous People’s Day 2021, Leo Koziol explores the indie-film roots of Sterlin Harjo and Taika Waititi’s hit native series, Reservation Dogs.

Breakout FX on Hulu hit Reservation Dogs speaks directly to native audiences, each episode made lovingly by a bevy of native directors, actors and crew, many of whom found their storytelling voices through independent film. Anyone new to native cinema could do no better than to start their journey with a few choice cuts from these native talents.

The indie-film factor in Reservation Dogs’ success cannot be overstated. Television has a reach that other media do not, yet the path to primetime has never been easy. Any television project can die in development, fall at the pilot stage, or fail to be renewed after one measly season. For underrepresented storytellers, this road is even rougher.

To arrive on the small screen with a fully formed voice, there needs to have been a place to warm that voice up, and it’s more often been in the world of independent film that these opportunities lie for Indigenous artists.

Reservation Dogs is the brainchild of Taika Waititi (Te Whānau-ā-Apanui, Aotearoa) and Sterlin Harjo (Seminole/Muscogee Creek), who were both supported as indie darlings at Sundance under the watchful eye of recently retired native program director Bird Runningwater. (He has left the storied institute in order to produce his own projects.)

Lane Factor as Cheese, Paulina Alexis as Willie Jack, D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai as Bear, Devery Jacobs as Elora Danan Postoak in TV series ‘Reservation Dogs’.

Episodes were also directed by veteran natives Blackhorse Lowe (Navajo Nation) and Sydney Freeland, as well as performance poet and Bishop Paiute Tribe citizen Tazbah Rose Chavez (from the Nüümü, Diné and San Carlos Apache).

Between them, these five have made fifteen feature films (and won an Oscar), which represent a wellspring of native cinema ripe for rewatching or—going by many recent Letterboxd reviews who have come to them via Reservation Dogs—first-time discovery.

For aficionados of native cinema, Reservation Dogs is full of uniquely native humor (greasy fry bread, anyone?) and pop-culture references (main character Elora is named for the baby in Willow), but the most fun aspect for me has been the in-jokes. The Skux Soda cabinet at the native clinic (Hunt for the Wilderpeople fan service), a row of Māori dolls in a native rez store (co-creator Waititi is Māori) and, best of all, in episode five, an Oklahoma cinema marquee listing films by the four Native American directors of the series: Barking Water (Harjo), Drunktown’s Finest (Freeland), Fukry (Lowe) and Your Name Isn’t English (Chavez).

Waititi, the starrier of the two creators, whose feature works range from the awkward romance of Eagle vs Shark through to next year’s Thor: Love and Thunder, has certainly injected a careful balance of humor and emotion into the series. From his filmography, Reservation Dogs most resembles his 2010 semi-autobiographical comedy, Boy. But at heart, it is Harjo’s show—set in his home community of Oklahoma, and the culmination of fifteen years of filmmaking that serve as a calling card to its themes.

Richard Ray Whitman and Casey Camp-Horinek as Frankie and Irene in Sterlin Harjo’s ‘Barking Water’.

Stretching back to his beginnings, you can see two of Harjo’s best shorts on his YouTube channel. Goodnight Irene mirrors episode two of the series with malaise and humor in a native clinic; Three Little Boys directly mirrors the “kids on the Rez” ensemble of the show.

Then, in a trio of dramatic features, we see the progression as Harjo’s filmmaking skills grow alongside better budgets and resources. Letterboxd members are proudly noting the thematic similarities in his works. “Like Reservation Dogs, Harjo finds his most striking emotional moments in the quiet spaces between friends and family members,” writes Hannibal Montana of the first, Four Sheets To The Wind (2007).

CoterEB notes that Harjo’s 2009 follow-up, Barking Water, slots neatly into the Reservation Dogs storytelling family: “What Harjo absolutely succeeds at is letting the audience go along with it… It’s emotionally effective without manipulation.” It’s an approach that is further on display in his third feature, Mekko (2015), Hannibal Montana again recognizing that “much like Reservation Dogs, Mekko has one foot in a nostalgia for a lost, proud past and another in the immediate issues facing Indigenous people today, namely poverty, violence, and addiction”. (Hanabi Banana gives a more pointed review of this film, which I loved. Spoiler alert!)

A still from Blackhorse Lowe’s 2009 short, ‘Shimásáni’.

Blackhorse Lowe is a long-time collaborator of Harjo’s; he was one of the editors of Mekko, and is also a Sundance alumnus. Lowe has a two-decade pedigree across many filmmaking departments and is a champion of genre-driven Indigenous films in New Mexico. His 2009 short Shimásáni is currently available on MUBI. He’s made three features, my favorite of which is Chasing The Light.

Writing about the 2014 film, Andy Nelson observes: “Lowe, also the cinematographer, captured some beautiful and haunting black-and-white imagery, which certainly helps add to the other world wanderings. It’s worth checking out, but the grittiness and raw drug comedy elements may be too much for a lot of people.”

I’m a huge fan of Lowe’s fellow Navajo director Sydney Freeland. You can watch her 2017 second feature, Deidra & Laney Rob A Train, on Netflix, but for me her best work to date is her first, Drunktown’s Finest (2014). Leonara Ann Mint writes of Freeland’s debut: “a very nuanced and powerful experience. Native American and trans voices are both way too rare in cinema, so to get both in the same film is often a revelation. All three plot lines here have depth, warmth and nuance, and by the end, the film had achieved a deep sense of emotional connectedness with each character that I won’t soon forget.”

Jeremiah Bitsui, MorningStar Angeline and Carmen Moore in Sydney Freeland’s ‘Drunktown’s Finest’ (2014).

When Drunktown’s Finest was released, Freeland had not yet come out as a trans person (one of three stories in the Navajo-set film is of a trans woman, and how Navajo culture traditionally accepted those of a “third gender”). She’s gone on to cut a path in both LGBTQ storytelling and Indigenous film, and it’s wonderful to see her on the team for Reservation Dogs. Freeland is also directing episodes of Peacock’s Rutherford Falls, which shares creative talent with the Reservation Dogs collective. And with Harjo, she is making Rez Ball, a sports film for Netflix about the unique culture of Indigenous basketball.

In front of the camera, the ensemble cast of Reservation Dogs carries a film pedigree as deep as the directors behind it, and while many of the films they have appeared in are made by non-native writers and directors, their performances—and, in many ways their experiences on those sets—inform their work on Reservation Dogs.

Kahnawà:ke Mohawk actress Kawennáhere Devery Jacobs (credited as Devery Jacobs for her role as Elora) has played significant roles in Rhymes for Young Ghouls, the zombie outbreak gore-fest Blood Quantum and the Neil Gaiman series American Gods, as well as a number of short films, including Ara Marumaru for the Māoriland Film Festival Native Slam.

Dallas Goldtooth, who is Dakota and Dińe, appears on screen as the spirit of a warrior who died at Custer’s last stand. Goldtooth can also be seen as Rich Hall’s traveling companion in the comedian’s 2012 documentary re-examination of Native American stereotypes. Bear is played by Canadian actor D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai (of Oji-Cree, Anishinaabe and Guyanese descent) who has a breakout feature role in this year’s Beans, by Mohawk director Tracey Deer.

The cast also includes several veterans of the native film scene. First Nation media pioneer Gary Farmer, of the Cayuga Nation and Wolf Clan, has appeared in more than 50 films, including First Cow, Dead Man and Blood Quantum, and has been nominated three times for an Independent Spirit Acting Award.

Devery Jacobs and Kiowa Gordon in ‘Blood Quantum’ (2019).

The legendary Cherokee star Wes Studi, who won an honorary Oscar at the 2019 Academy Awards, has had roles in numerous Hollywood blockbusters, including Dances With Wolves, The Last of the Mohicans and Avatar. My favorite Studi film is the comedy short, Ronnie BoDean, which you can watch for free on director Stephen Paul Judd’s Vimeo.

Nothing gets made without a script, and the brains in the Reservation Dogs writers’ room also have considerable roots in independent arts. Many of the crew, including Harjo and Goldtooth, are members of the 1491s, an Oklahoma-based native sketch comedy group. The 1491s are most famed for the 2019 Oregon Shakespeare Festival, where they premiered Between Two Knees, an intergenerational comedic love story/musical set against the backdrop of true events in native history.

1491s with writing credits on the show are poet and podcaster Tommy Pico (from the Viejas reservation of the Kumeyaay nation), Bobby Wilson (Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota), who plays Marcus Werewolf in the What We Do in the Shadows television spinoff, and Migizi Pensoneau (Ponca/Ojibwe), who has several shorts on his filmography.

Right after the finale of series one, FX on Hulu announced Reservation Dogs season two and an expansion of its all-Indigenous writers’ room. Director Blackhorse Lowe joins the room, along with actors Jacobs and Goldtooth.

Other new writers in the room are Ryan RedCorn (Osage), who played Mike in Harjo’s Barking Water, Afro-Indigenous comedian and director Chad Charlie (Ahousaht First Nation), who made the 2020 short Uu?uu~tah and has another, Firecracker Bullets, coming next year, and award-winning writer-director Erica Tremblay (Seneca-Cayuga). Her 2020 short film Little Chief premiered at Sundance, and she is following in Waititi’s and Harjo’s footsteps as a Sundance Screenwriters and Directors Lab fellow.

The hope for both audiences and our industry is that Reservation Dogs won’t be a one-off. At the 2021 Emmy Awards, Harjo stood on stage and said, “We are here on television’s biggest night as creators and actors, proud to be Indigenous people working in Hollywood, representing the first people to walk upon this continent.”

Joined by his four leading actors, the group collectively stated: “Thankfully networks and streamers are now beginning to produce and develop shows created by and starring Indigenous people. It’s a good start, which can lead us to the day when telling stories from under-served communities will be the norm, not the exception. Because, like life, TV is at its best when we all have a voice.”

Sterlin Harjo and Taiki Waititi. / Photo by Robin Lori / INSTAR Images

As someone who for many years has followed the rise of native cinema from my home film festival, the arrival of this Stateside television hit marks a new day for native creatives. To Indigenous film fans, its creators are cult heroes who have been working for decades both in front of and behind the screen getting native American stories told, uncompromisingly.

I think about the collective talent that Sterlin and Taika have wrapped around the series, and I realize they simply contacted all their friends from past indie productions and said, hey, come work with us on this all-native production, we can pay you this time.

Related content

Leo’s list of the indie roots of Reservation Dogs

Reel Injun: a 2009 documentary by Catherine Bainbridge, Neil Diamond and Jeremiah Hayes about the Native American Hollywood experience

El Napalmo’s extensive Indigenous Cinema list

Dolores’ list of movies in which the main native character is in fact white

Beans is released in select theaters and on demand on November 5

Follow Leo on Letterboxd

#reservation dogs#taika waititi#sterlin harjo#tracey deer#beans#fx on hulu#rez dogs#leo koziol#maori movies#indigenous film#indigenous filmmaker#indigenous director#native american director#indigenous people's day

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Driven to Love.

With the 2021 Palme d’Or winner in theaters now, Titane filmmaker Julia Ducournau speaks with Letterboxd’s East Coast editor Mitchell Beaupre about destroying societal expectations of gender, the unspoken nature of love, and finding art in a bunch of dancing firefighters.

“I wanted to get to the essence of the person, no matter what their gender is, their sexuality, no matter if they’re from the same family or not. That was the challenge for me, to see if I could make you feel the love.” —Julia Ducournau

Back in 2016, when writer-director Julia Ducournau delivered her debut feature Raw, audiences had no idea what they were in for. While no medical emergencies were reported at its Cannes Film Festival premiere, a Midnight Madness screening at TIFF resulted in ambulances being called in to treat multiple filmgoers who had passed out.

The film earned a mighty reputation, and that was only solidified once it emerged to the public. Perhaps Kat sums it up best: “I left the theater cackling, feeling energized and in love with cinema and life and women—and yet the film also made me anxious and worried and grossed out and violently sad.”

This extreme mixture of emotions wasn’t a one-off for Ducournau, who has followed up that lightning rod of a debut with perhaps an even more headline-grabbing sophomore feature. From the moment Titane debuted at this year’s Cannes, it was clear that it was going to be one of the most talked-about films of 2021.

Reactions out of the fest declared Titane “singular, shocking, repulsive and incendiary”, with Cronenberg comparisons aplenty for this body horror that seeks to reinvent how we see the human anatomy. The Cannes jury awarded the film the Palme d’Or, with jury president Spike Lee so eager to give it the prize that he misunderstood a question at the announcement ceremony and announced it prematurely.

Adèle Guigue as seven-year-old Alexia in ‘Titane’.

The intense reactions out of Cannes were simply the beginning for Titane, which has gone on a barnstorming tour of just about every major festival this year, shocking and awing audiences along the way. Marking Ducournau’s return to TIFF Midnight Madness, Mav took some time to shout out the performances from Agathe Rousselle and Vincent Lindon, while Brittany wrote, “At times I had to watch through my fingers, at other times I was smiling ear to ear”. At NYFF, EJ spoke to the thrill of seeing the film in a theater with an audience “squirming, groaning, whimpering and (nervously) laughing”. Also, just in case you’re wondering, yes there have been more medical emergencies with this one.

Titane defies easy explanation; one can’t really give a brief plot synopsis without getting into spoiler territory. Abandoning the three-act structure, Ducournau’s film is constantly turning, ripping itself apart only to build back together as something entirely new in its explorations of a troubled young woman, Alexia (Rousselle), and a complicated firefighter, Vincent (Lindon).

Mitchell Beaupre straps in to speak with Ducournau about her unique approach to love, how Raw paved the way for her latest feature, and the fascinating arc she takes us on with her main characters.

According to just about everyone on Letterboxd who has seen Titane, you are essentially responsible for saving cinema in 2021. So many reviews are speaking of not only their love for the film, but the specific thrill of watching it in a theater with other humans, sharing intense reactions alongside other people. What does that mean for you to have created such a collective experience?

Julia Ducournau: For me, it’s not only meaningful—it’s essential. Titane and Raw were both crafted for the theater. This is in terms of image, obviously, but also with the sound, which is something very much less talked about that makes a huge difference. When you want to create a corporeal experience that is based on your bodily sensations, when you try to make the audience relate to the characters on that deeper level, the sound is something that helps a lot. That’s very specific to sound in the theater.

For example, something I use a lot with my sound designer and my mixer are sub [woofers]. I love subs because they make you feel the scene physically. You feel them through the floor, and you feel them in your chest. However, these subs can disappear very easily if they are not played with the specific amplifiers and sound system. It’s not something you will ever feel on your computer or on your TV, and obviously even less so on your phone. This is something totally linked to the theater experience, and a big part of the sensation I design for you to feel what my characters are feeling down to their skin.

Agathe Rousselle as the adult Alexia in ‘Titane’.

While the film is an extremely effective body horror, another thing we’ve noticed people engaging with more than anything else is the love at the heart of Titane. What compelled you to take audiences on this totally visceral journey that results in such an outpouring of and deep understanding of love?

Whew. That’s a bit hard to answer. I decided to put love at the center of Titane because when I was in post-production on Raw, I noticed that while love was present in the film, it was still a sidetrack. I actually began to wonder why I chose that, and if I felt that love was something I could express in a film.

I asked myself this question even more so when the idea is to make you feel what the characters are feeling. How do you make the viewer feel the sensation you have in your body when you love someone? That’s something incredibly difficult.

It was a very interesting challenge to try and aim at that, rather than to talk about love with words. For me, words tend to belittle the feeling a little bit, and also to belittle everything that this film embraces in terms of trying to see past all the presentations that the person in front of you might undergo.

I wanted to get to the essence of the person, no matter what their gender is, their sexuality, no matter if they’re from the same family or not. That was the challenge for me, to see if I could make you feel the love. If I could actually tackle the topic in the unconditional way that I see it. That’s why I decided to do Titane.

I must say, as a non-binary person myself, something that resonated for me personally was the queering of gender in the film. The way that you blur these lines between masculine and feminine, and call into question what those words even mean. How did you want to explore the idea of gender within the film?

At the start, it was about trying to have a character that broadens the spectrum of what gender means, but also what our humanity means. I wanted to show that there are a lot more options, and a lot more ‘gazings’ than we actually want to believe there is.

As I was writing the script, I also came to the conclusion that, for me, gender is not relevant in order to define someone. It’s only relevant in terms of societal expectations, which have nothing to do with the individual. I think that it is incredibly limiting to our comprehension of individuality, but also to our comprehension of the interactions we can have with others.

All I tried to do is put the audience in a position of growing empathy with my characters so they would accept the fact that my character is not just one, and she is certainly not what she seems to be. That actually they would accept every single stage of her transformation in order to just admit at the end that she is completely full. That she is one when she’s both Adrien and Alexia, or none of them.

Agathe Rousselle as Alexia, putting her past behind her.

Something that queer people are keenly aware of is the idea of perception, and how perception can often be a threat to people who are pushed aside by society. Could you speak about how that idea of perception played into the way that you wanted to develop the character of Alexia?

It’s absolutely central. The way I look at my film, everything has to do with gaze—with the way you look at someone. A lot of people ask me why I use the body-horror grammar, and why I tear the flesh like this, and that’s why. For me, the flesh and the skin is the first barrier of outside representation, and of outside expectation. We have got to shed it. We have to shed the skins one by one in order to try to be free, and basically to be ourselves—or even moreso, to become ourselves, because I tend to see things always as a becoming more than a state.

The way I tried to portray that in my film is actually with the father figures. Alexia’s biological father is a character who never, ever, ever looks at her. He just dismisses her very existence from the start, which makes her someone who doesn’t have any contours. She does not have a clear identity.

That’s why there is an overflow of impulses getting out of her because there is nothing to contain that. She is completely loose, if you wish.

Then she meets Vincent. Where is his headspace when she comes into his life, and what do they find in one another?

On the contrary to Alexia, Vincent is a very neurotic character. He’s a character inspired by the movie Vertigo, and how Jimmy Stewart’s character completely sculpts his own fantasy onto Kim Novak.

I insisted on Vincent never being this white knight in shining armor. In his overbearing neurosis he also becomes incredibly intrusive. The thing that makes him different from the biological father is that because of his fantasy, he has to look at her constantly. He wants to sculpt that fantasy. He wants to create it.

At this level, he gives her the contours of someone else, but it so happens that at one point she decides that she feels good in these contours, even though they are the wrong ones. They’re not hers, but she feels good. She decides to adopt those contours, which we see the turn happen when she comes back after leaving, and she doesn’t kill him.

That’s where she decides that she feels better in these contours than in the previous ones she had when she was a woman. After that, she begins to get in touch with her humanity through this relationship. She gets in touch with her emotions, which never happened before, and it makes her feel alive. It’s like for the first time in her life she actually starts to exist.

The challenge for her at this level, and the higher stakes, is to actually show herself for who she is to the person that she came to love—and to be accepted as she is. This lasts until the final moment of the film.

Vincent Lindon, as Vincent, working his body out after hours.

It’s a fascinating arc, as we also see the more she gets in touch with her humanity, the less her body looks human.

This is also something very important in the film in terms of where we stand in our own humanity. That’s why at the end she decides to go to him, and to show herself naked, just the way she is. To tell him, “I love you. The way I am now loves you.” You see how it’s a very long journey through, ending on the idea that gender is irrelevant when it comes to identity.

Speaking of that notion of gender in conjunction with how you explore the use of the body in your films, I have to ask you about the pair of firefighter dancing scenes, both of which have a heavy air of homoeroticism. The first is a lovely sequence bathed in this purple light, and later there’s a more aggressive mosh pit. What ideas did you want to draw out in these sequences?

In that first one, the homoeroticism that’s present there is debunking the kinds of expectations we could have of firefighters together. It’s again trying to soften this idea of sheer testosterone. Actually, if you look closely, some of the firemen in the background are very good dancers. They have some really good moves, which makes it even more artistic. Somehow it becomes more of a tableaux than just a regular party, which is something I was aiming for. That’s why I used real dancers to play the firemen at this moment. The idea of tableaux is essential, especially when you use slo-mo like this.

As you mentioned, there is a clear difference between the two scenes. With the mosh pit, we used this very white shower light to blend every extra and Adrien together so that they all look alike. They all have shaved heads, big muscles, and are jumping around all over the place. At a certain point, you don’t know who’s who anymore. That’s the intention, as Adrien is at the point where she wants to keep Vincent so badly that she would do anything to blend in completely.

However, this desire to blend in or to belong is something that I see as quite violent. This is not a positive to me. Belonging is never a positive in my mind, for the identity or for the psyche. That’s why it’s so physical and so aggressive.

Vincent Lindon, Julia Ducournau and Agathe Rousselle at the 74th Cannes Film Festival. / Photo by Julien Reynaud/APS-Medias

That scene takes a big shift once Alexia gets on top of the truck, and we see her inner self start to come to the surface.

When she’s alone on top of the truck, it’s the exact opposite of what the scene was before—the opposite of that violence. She’s on the truck in the form of this pedestal, if you wish, because I tried to instill something that was very sacred there. The firemen look at her either like she’s a Messiah, or they look away because it’s too much to look at. It’s too bright, it’s too strong.

At this level, this is for me the moment where she has moved past this idea of belonging and blending in. She’s feeling herself with both Adrien and Alexia, and something even more. This is her in that moment. There is full grace in this moment, which is what I was aiming at. You see all the way through the film how dance is something I use to go against the audience’s expectations.

On behalf of all Letterboxd film lovers, I want to thank you for your commitment to art that rips open our hearts and brains like this—and as a genderqueer person, thank you for making a film that made me feel so seen.

That means a lot to me. Thank you very much, Mitchell.

Related content

Gory B Movie’s list of horror films directed by women from 1900—present

Maxvayne’s extensive list of body-horror films

Bionic Tim’s list of New French Extremity & Modern French Horror, ranked

Follow Mitchell on Letterboxd

‘Titane’ is in theaters now and will be available on VOD from Tuesday, October 19.

#titane#julia ducournau#female director#directed by women#french cinema#cinema du femme#agathe rousselle#vincent london#palme d'or#cannes#tiff midnight madness

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Noir Zealand Road Trip.

Breakout noir filmmaker James Ashcroft speaks to Letterboxd’s Indigenous editor Leo Koziol about his chilling new movie Coming Home in the Dark—and reveals how Blue Velvet, Straw Dogs and a bunch of cult New Zealand thrillers are all a part of his Life in Film.

“Many different types of feet walk across those lands, and the land in that sense is quite indifferent to who is on it. I like that duality. I like that sense of we’re never as safe as we would like to think.” —James Ashcroft

In his 1995 contribution to the British Film Institute’s Century of Cinema documentary series, Sam Neill described the unique sense of doom and darkness presented in films from Aotearoa New Zealand as the “Cinema of Unease”.

There couldn’t be a more appropriate addition to this canon than Māori filmmaker James Ashcroft’s startling debut Coming Home in the Dark, a brutal, atmospheric thriller about a family outing disrupted by an enigmatic madman who calls himself Mandrake, played in a revelatory performance by Canadian Kiwi actor Daniel Gillies (previously best known for CW vampire show The Originals, and as John Jameson in Spider-Man 2). Award-winning Māori actress Miriama McDowell is also in the small cast—her performance was explicitly singled out by Letterboxd in our Fantasia coverage.

Based on a short story by acclaimed New Zealand writer Owen Marshall, Ashcroft wrote the screenplay alongside longtime collaborator Eli Kent. It was a lean shoot, filmed over twenty days on a budget of just under US $1 million. The film is now in theaters, following its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in January, where it made something of an impact.

Erik Thomson, Matthias Luafutu, Daniel Gillies and Miriama McDowell in a scene from ‘Coming Home in the Dark’.

Creasy007 described the film as “an exciting New Zealand thriller that grabs you tight and doesn’t let you go until the credits are rolling.” Jacob wrote: “One of the most punishingly brutal—both viscerally and emotionally—first viewings I’ve enjoyed in quite a while. Will probably follow James Ashcroft’s career to the gates of Hell after this one.”

Filmgoers weren’t the only ones impressed: Legendary Entertainment—the gargantuan production outfit behind the Dark Knight trilogy and Godzilla vs. Kong—promptly snapped up Ashcroft to direct their adaptation of Devolution, a high-concept novel by World War Z author Max Brooks about a small town facing a sasquatch invasion after a volcanic eruption. (“I find myself deep in Sasquatch mythology and learning a lot about volcanoes at the moment,” says the director, who is also writing the adaptation with Kent.)

Although Coming Home in the Dark marks his feature debut, Ashcroft has been working in the creative arts for many years as an actor and theater director, having previously run the Māori theater company Taki Rua. As he explains below, his film taps into notions of indigeneity in subtle, non-didactic ways. (Words in the Māori language are explained throughout the interview.)

Kia ora [hello] James. How did you come to be a filmmaker?

James Ashcroft: I’ve always loved film. I worked in video stores from the age thirteen to 21. That’s the only other ‘real job’ I’ve ever had. I trained as an actor, and worked as an actor for a long time. So I had always been playing around with film. My first student allowance that I was given when I went to university, I bought a camera, I didn’t pay for my rent. I bought a little handheld Sony camera. We used to make short films with my flatmates and friends, so I’ve always been dabbling and wanting to move into that.

After being predominantly involved with theater, I sort of reached my ceiling of what I wanted to do there. It was time to make a commitment and move over into pursuing and creating a slate of scripts, and making that first feature step into the industry. My main creative collaborator is Eli Kent, who I’ve been working with for seven years now. We’re on our ninth script, I think.

But Coming Home in the Dark, that was our first feature. It was the fifth script we had written, and that was very much about [it] being the first cab off the rank; about being able to find a work that would fit into the budget level that we could reasonably expect from the New Zealand Film Commission. I also wanted to make sure that piece was showing off my strengths and interests—being a character-focused, actor-focused piece—and something that we could execute within those constraints and still deliver truthfully and authentically to the story that we wanted to tell and showcase the areas of interest that I have as a filmmaker, which have always been genre.

Do you see the film more as a horror or a thriller?

We’ve never purported to be a horror. We think that the scenario is horrific, some of the events that happen are horrific, but this has always been a thriller for me and everyone involved. I think, sometimes, because of the premiere and the space that it was programmed in at Sundance, being in the Midnight section, there’s a sort of an association with horror or zany comedy. For us it’s more about, if anything, the psychological horror aspect of the story.

It’s violent in places, obviously, but there’s very little violence actually committed on screen. It’s the suggestion. The more terrifying thing is what exists in the viewer’s mind [rather] than necessarily what you can show on screen. My job as a storyteller is to provoke something that you can then flesh out and embellish more in your own psyche and emotions. It’s a great space, the psychological thriller, because it can deal with the dramatic as well as some of those more heightened, visceral moments that horror also can touch on.

Director James Ashcroft. / Photo by Stan Alley

There’s a strong Māori cast in your film. Do you see yourself as a Māori filmmaker, or a filmmaker who is Maori?

Well, I’m a Māori everything. I’m a father, I’m a husband, I’m a friend. Everything that I do goes back to my DNA and my whakapapa [lineage]. So that’s just how I view my identity and my world. In terms of categorizing it, I don’t put anything in front of who I am as a storyteller. I’m an actor, I’m a director. I follow the stories that sort of haunt me more than anything. They all have something to do with my experience and how I see the world through my identity and my life—past, present and hopefully future.

In terms of the cast, Matthias Luafutu [who plays Mandrake’s sidekick Tubs], he’s Samoan. Miriama McDowell [who plays Jill, the mother of the family] is Māori. I knew that this story, in the way that I wanted to tell it, was always going to feature Māori in some respect. Both the ‘couples’, I suppose you could say—Hoaggie [Erik Thomson] and Jill on one side and Tubs and Mandrake on the other—I knew one of each would be of a [different] culture. So I knew I wanted to mirror that.

Probably more than anything, I knew if I had to choose one role that was going to be played by a Māori actor, it was definitely going to be Jill, because for me, Jill’s the character that really is the emotional core and our conduit to the story. Her relationship with the audience, we have to be with her—a strong middle-class working mother who has a sort of a joy-ness at the beginning of the film and then goes through quite a number of different emotions and realizations as it goes along.

Those are sometimes the roles that Māori actors, I often feel, don’t get a look at usually. That’s normally a different kind of actor that gets those kinds of roles. And then obviously when Miriama McDowell auditions for you it’s just a no-brainer, because she can play absolutely anything and everything. I have a strong relationship with Miriama from drama-school days, so I knew how to work with her on that.

Once you put a stake in the ground with her, then we go, right, so this is a biracial family, and her sons are going to be Māori and that’s where the Paratene brothers, who are brothers in real life, came into the room, and we were really taken with them immediately. We threw out a lot of their scripted dialogue in the end because what we are casting is that fundamental essence and energy that exists between two real brothers that just speaks volumes more than any dialogue that Eli and I could write.

Matthias Luafutu as Tubs in ‘Coming Home in the Dark’.

What was your approach to the locations?

[The area we shot in] is very barren and quite harsh. I spent a lot of time there in my youth, and I find them quite beautiful places. They are very different kinds of landscapes than you normally see in films from our country. We didn’t want to go down The Lord of the Rings route of images from the whenua [land] that are lush mountains and greens and blues, even though that’s what Owen Marshall had written.

I was very keen, along with Matt Henley, our cinematographer, to find that duality in the landscape as well, because the whole story is about that duality in terms of people, in terms of this world, and that grey space. So that’s why we chose to film in those areas.

Regarding the scene where Tubs sprinkles himself with water: including this Māori spiritual element in the film created quite a contrast. That character had partaken in something quite evil, yet still follows a mundane cultural tradition around death. What are your thoughts on that?

Yeah. I’m not really interested in black-and-white characters of any kind. I want to find that grey space that allows them to live within more layers in the audience’s mind. So for me—and having family who have spent time in jail, or knowing people who have gone through systems like state-care institutions as well as moving on to prison—just because you have committed a crime or done something in one aspect of your life, that doesn’t mean that there isn’t room and there aren’t other aspects that inform your identity that you also carry.

It’s something that he’s adopted for whatever reasons to ground him in who he is. And they can sit side by side with being involved in some very horrendous actions, but also from Tubs’ perspective, these are actions which are committed in the name of survival. You start to get a sense Mandrake enjoys what he does rather than doing it for just a means to the end. So any moment that you can start to create a greater sense of duality in a person, I think that means that there’s an inner life to a world, to a character, that’s starting to be revealed. That’s an invitation for an audience to lean into that character.

Erik Thomson and Daniel Gillies in ‘Coming Home in the Dark’.

What is the film that made you want to get into filmmaking?