Text

Transcript Episode 91: Scoping out the scope of scope

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘Scoping out the scope of scope. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Lauren: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Lauren Gawne.

Gretchen: I’m Gretchen McCulloch. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about scope. But first, our most recent bonus episode was about inner voice, and the different ways that people organise their interior narrative – such as inner speech, inner visualisation, inner non-symbolic thought – and other ways that our minds are surprisingly different from each other.

Lauren: We look at a classic paper on inner voice, and we also include some results about inner voice from our 2023 listener survey.

Gretchen: It was fun to see how our results compared to the results of that classic survey and compare differences in methodologies and how the insides of our minds are both similar and different to each other.

Lauren: Also, on Patreon, our patrons at the Ling-phabet tier not only get all of our bonus episodes, but they get a Lingthusiast sticker, which is not available anywhere else.

Gretchen: This is a sticker that says, “Lingthusiast – a person who’s enthusiastic about linguistics,” if you want to stick it on your laptop or your water bottle and try to encourage people to talk about linguistics with you. We also give people in the Ling-phabet tier your very own, hand-selected character of the International Phonetic Alphabet – or if you have another symbol from somewhere in Unicode, you can request that instead – and we put that in your name or your username on our sponsorship Wall of Fame on our website to thank you for supporting the show.

Lauren: You can see our Supporter Wall of Fame at lingthusiasm.com/supporters, and maybe you can join it as well.

Gretchen: We also make delightful high-quality, human-edited transcripts for all of our episodes – bonus episodes and main episodes – where all of the proper names and words in other languages have had their spellings checked. Transcripts are available as text-based pages at lingthusiasm.com/transcripts or if you’d like to follow along with the audio and the transcript at the same time, you can go to our YouTube channel. Transcripts for bonus episodes are linked to from each of those bonus episode pages as well on Patreon.

Lauren: It’s thanks to the support of our patrons that we are able to continue to provide the show ad-free and high-quality transcripted.

[Music]

Gretchen: One of the best kebabs that I ever had was a philosophical kebab.

Lauren: Hm, okay.

Gretchen: I was at a kebab shop, as one does, and I ordered my kebab off the menu, and then the person behind the counter says to me, “You okay with everything?” And I sort of had this moment of, you know, I do like to think that I’m a relatively accepting person, but there are some things in life that maybe I’m not okay with.

Lauren: Um, is it just that they wanted to know if you wanted tomatoes and hummus and onions?

Gretchen: Yeah, yeah, that’s what they were asking me.

Lauren: Reminds me of the everything bagels in Everything Everywhere All at Once where the everything bagel eventually takes into it everything across the multiverse.

Gretchen: So, not just sesame seeds and poppy seeds and dried onion bits.

Lauren: No, a little bit more “everything” than a traditional, physical everything bagel.

Gretchen: You know, it’s funny that “everything” in the context of a kebab and “everything” in the context of a bagel are different from each other. This also reminds me of a very nice poem by Shel Silverstein which is about a hot dog.

Lauren: Can I hear it?

Gretchen: Yeah. “I asked for a hot dog / With ‘everything’ on it / And that was my big mistake, / ’Cause it came with a parrot, / A bee in a bonnet, / A wristwatch, a wrench, and a rake. / It came with a goldfish, / A flag, and a fiddle, / A frog, and a front porch swing, / And a mouse in a mask– / That’s the last time I ask / For a hot dog with ‘everything’.”

Lauren: So good – and not dissimilar to one of the main plot points in Everything Everywhere All at Once.

Gretchen: Which is great. We’ve had hot dogs and bagels and kebabs, and the set of prototypical toppings for them, I mean, could include onions in any case but definitely includes lots of other things as well. And yet, a goldfish, a rake, a parrot, a frog – not typical toppings for any of these food items.

Lauren: I think we should open a café with all of these ambiguous “everything” foods. What should we call it?

Gretchen: We could have everything bagels, hot dogs and kebabs with everything, like an everything pizza. I think we could call it the “Everything Café.”

Lauren: Ah, yeah. We actually have a different phrase in Australia. We can order things with “the lot.” You can get a pizza with the lot; you can get a burger with the lot. It means it comes with the full set of expected items – no goldfish, typically.

Gretchen: There is a certain irony to the fact that in Canada we also have a phrase that’s different from “with everything,” and that’s “all dressed.”

Lauren: Ah, but is it all dressed with –

Gretchen: No goldfish.

Lauren: But is it all dressed with a flag and a fiddle?

Gretchen: No goldfish, no fiddles. But you can have all dressed chips, which is the flavour that has a bit of barbeque and a bit of sour cream and onion and a bit of ketchup, and it’s just got all of the stuff.

Lauren: All dressed chips are delicious – just, like, generically salty delicious.

Gretchen: You can have an all dressed pizza, which is a pizza with the typical expectation of pizza toppings. Again, no fiddles. In French, “tout garnis” which is also perhaps a literal translation – I don’t know which direction – of “garnished with everything.”

Lauren: Hm, yes. Of course, what counts as “everything” varies across items and across cultures because Australia famously loves some beet root in a burger with the lot.

Gretchen: Ah, yes, whereas my all dressed burger does not contain beet root, although I understand it’s delicious.

Lauren: It is delicious, indeed.

Gretchen: Both “everything” and “all dressed” and I assume, also, “the lot,” have something important in common, which is this idea that they include “all,” but “all” within a culturally-defined set not everything possibly conceivable and that we have a set of expectations for what we mean around that “all” or that “every.”

Lauren: Knowing where that “all” stops creates issues with what the scope of “all” includes.

Gretchen: Right. We have expectations around the scope of what goes on a pizza or the scope of what goes on a hot dog, but those are implicit.

Lauren: Maybe we should call it the “Scope Shop” for our café.

Gretchen: Ooo, “The Scope Shop,” “Ye Olde Scope Shop.”

Lauren: /skoʊp ʃoʊp/.

Gretchen: “Shoppe”? Oh, and then can we have a Medieval bard at our Scope Shop?

Lauren: Uh, I’m not sure why, but given this is all hypothetical, pitch me.

Gretchen: Well, it’s because the Old English word for an oral poet or a bard was /ʃɑp/, which was pronounced like “Scope Shop,” but it’s spelled S-C-O-P. It’s like halfway between the two, so then you can have a “Scope Shop Scop.”

Lauren: Right. This is ambiguous in terms of which word you’re using, which is very different from the kind of ambiguity we’re gonna be looking at with “everything.”

Gretchen: This is the ambiguity that has to do with which word you mean or what a specific word means rather than ambiguity that’s inherent to the concept of “everything” that it includes an expected set.

Lauren: When it comes to grammar, it’s not just words like “everything” and “the lot.” This kind of ambiguity pops up in a bunch of places in grammar, and that’s what’s on the menu for today.

Gretchen: Mm-hm. Can we also have at the Scope Shop customised birthday cakes?

Lauren: Sure, why not.

Gretchen: I’m gonna get you to write a message for me on the cake, okay?

Lauren: Okay, sure, what would you like on your cake?

Gretchen: I want it to say, “Happy Birthday.” Underneath that, “We love you.”

Lauren: Okay. I’m gonna decorate a cake, and it’s gonna say, “Happy birthday underneath that we love you.”

Gretchen: Yeah, well, what I want is for it to say, “Happy birthday.” UNDERNEATH that, “We love you.”

Lauren: Great. “Happy Birthday. Underneath that: We love you.” Eight words. We should be able to fit that on a cake.

Gretchen: No, I don’t want the WORDS “underneath that” to be on the cake. I want the words “We love you” to be literally underneath the words “Happy birthday.”

Lauren: Oh, like, “Happy birthday. We love you.”

Gretchen: Yes.

Lauren: I mean, it’s fine, but it’s not as funny.

Gretchen: See, you do see this on various pictures that go around the internet of very literal cake decorations. You know, “Happy birthday, Kevin, in red text,” where the “in red text” is also literally written on the cake or something like that.

Lauren: There’s a running series of jokes in this vein from BoJack Horseman, which is an animates series, and the birthday banners start with “Happy birthday, Diane, and use a pretty font.”

Gretchen: So, it’s not in a pretty font. It’s “and use a pretty font” is on the banner.

Lauren: Yes.

Gretchen: Okay.

Lauren: And the next one is “Congrats Diane and Mr. Peanut Butter. Peanut Butter is one word.” Again, all of it on the banner and, for some reason, they went back to the same supplier despite two years of failed banners because –

Gretchen: Rookie mistake.

Lauren: – the next year is “Congrats Diane and Mr. Peanut Butter. Mr. Peanut Butter is one word and don’t write one word.”

Gretchen: Oh, no, I love it.

Lauren: And then at some point, I think it’s probably Mr. Peanutbutter is wearing a t-shirt that says, “I had a ball at Diane’s 35th birthday, and underline ball. I don’t know why this is so hard.”

Gretchen: Again, the shirt says, “I don’t know why this is so hard.”

Lauren: Yes. Someone is taking down a quotation and is deciding to misinterpret a re-reading of “Oh, yeah, they said on the t-shirt put ‘I had a ball at Diane’s 35th birthday, and underline ball, and I don’t know why this is so hard’.”

Gretchen: Sounds very normal to me. I mean, this is how you can tell that they were ordering these banners and these t-shirts and so on and these cakes over the phone or potentially in conversation and not in written English, for example, because then you would just have a text field, and you could use punctuation to convey what you want on the cake.

Lauren: I mean, in spoken language we use our intonation, and in signed languages we can use the sign space, so where we sign something to indicate the start or the end of something that is being quoted. But misinterpretations can arise, and that’s where we get these hilarious cakes and banners.

Gretchen: I always think of this in context of the CBC, which is the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, where I remember as a child hearing CBC radio announcers saying things like, “The prime minister said, quote, ‘Blah blah blah,’ end quote” – or actually I wasn’t sure if it was “end quote” or “un-quote.” I looked I up on the CBC website, and I actually found both in the same transcript. Oh, wait, can I do these examples for you in my CBC radio voice?

Lauren: Yeah, sure, absolutely.

Gretchen: “A senior official said, the actual number may be, quote, ‘higher than is being cited,’ un-quote.”

Lauren: I love how generic that line of media is taken out of context, but also, how snarky it is to highlight that something is “higher than is being cited.”

Gretchen: Second example. “The provincial health minister has called the overcrowding, quote, ‘not acceptable,’ end quote.”

Lauren: Amazing. There’re just two words. “Not acceptable” is in the “quote-end quote.” Because you don’t want, as a newsreader, for people to think that the next line of the news is potentially something attributed to the provincial health minister.

Gretchen: Exactly. Because they’re saying it in this very flat, modulated, not-expressive – they’re not doing a whole bunch of stuff with intonation, and they obviously don’t have gestures because they’re on the radio – so they need the formal statement of – sometimes saying, “un-quote,” sometimes saying “end quote” – to demarcate exactly where the quotes begin and end.

Lauren: That’s because once we say someone said something, that opens up the beginning of this reported scope, and without intonational punctuation, like quote marks, very helpful, but without them, it can be hard to know where it stops. That’s because in English the verb “to say” comes before what is being said.

Gretchen: I could say something like, “Lauren told me a story,” and maybe I said this ten years ago, and everything I’ve been saying since then has just been in the story you told me.

Lauren: Hmm, yes. Highly implausible, but I guess technically possible.

Gretchen: This podcast has secretly just been one of us this whole time.

Lauren: The fact that our verb “to say” comes before what is being said is not the way that every language structures its grammar. For languages that tend to put the verb at the end of a sentence, that “say” will come after the thing that is being said, and this is true for the Tibeto-Burman languages that I work with as well as many other languages in the world, but it means that you know when a quote finishes because someone will say – you know, it would be something like, “The provincial health minister, the overcrowding, ‘not acceptable,’ he said,” or something to that paraphrased effect. You know the end of a quotation. It might be ambiguous at the front end, but you know when something is finished.

Gretchen: Despite how English verbs normally work, with “said,” you can put it at the end of a sentence. There’s a whole style of joke in English that depends on putting the verb towards the end. They’re known as a Tom Swifty. By convention, they’re always attributed to a speaker called “Tom.” You have a statement something like, “‘If you want me, I shall be in the attic,’ said Tom, loftily.”

Lauren: And the way that Tom says something is always a hilarious pun on the content of what is being said. Yeah, that is a great example of –

Gretchen: Like “attic” and “loft.” It wouldn’t be funny if you said, “Tom said loftily, ‘I shall be in the attic’.” Actually, maybe that’s still funny because it’s just the connection between the two.

Lauren: But not as funny to have the punchline delivered at the end.

Gretchen: Yeah, exactly.

Lauren: Of course, even though languages that have the verb, say, at the end of the sentence, they also do the thing English does where we just report something without saying, “They said.” There is still the chance for ambiguous cake decoration to occur.

Gretchen: It’s very important to be able to have funny cakes. Those cake examples of scope in quoted speech are this humorous misinterpretation of something that someone says that someone else writes down. There’s also another way that you can use scope to get multiple readings. This is with negation.

Lauren: Oh, yeah, that’s another fun place for scope ambiguity.

Gretchen: In this case, you can get one sentence that itself has several meanings depending on how you interpret the negation.

Lauren: For example, a bench in honour of Nicole Campbell, it’s engraved with a little plaque, and it says, “In honour of Nicole Campbell, who never saw a dog and didn’t smile.”

Gretchen: This photo of this plaque on this bench went around the internet a while back. People found it really funny because you have this very obvious humorous reading, which is she refused to look at dogs and also wouldn’t crack a grin.

Lauren: Which is a very cantankerous anti-dog stance that is clearly the opposite of what was actually so wonderful about her.

Gretchen: And clearly the intended reading is “It was never the case that when she saw a dog she didn’t smile at the dog.”

Lauren: And, I assume, in this park, at this bench or somewhere proximal, this would often occur.

Gretchen: Right. Maybe it was a dog park.

Lauren: Instead, what you get is like, “She refused to look at dogs and she never ever smiled at all in her entire life.”

Gretchen: Or she lived on an island where there were no dogs at all.

Lauren: I mean, that’s why you wouldn’t smile.

Gretchen: Because there’s no dogs there.

Lauren: Sad times.

Gretchen: What a tragic bench plaque of this horror life that this person lived. It’s so tempting to get that reading.

Lauren: We’re commemorating a tragedy there.

Gretchen: It’s really important to have memorial plaques like this. If we think of “never” as popping up a little umbrella over some part of the remainder of the sentence, then the parts that get shaded by that umbrella are within the scope of never, and the parts that are still out in the open to get rained on or sunned on are the ones that are outside the scope of “never.”

Lauren: We have one reading where there’s a really narrow scope of how big the umbrella for “never” is, which is just “never saw a dog,” and then “didn’t smile” is out with its own narrow little umbrella. So, “never saw a dog” and “didn’t smile” – poor, grumpy Nicole. Then we have a really broad umbrella where “never” fits over the whole “saw a dog and didn’t smile.” “Nicole Campbell, who never saw a dog and didn’t smile” – a really big umbrella. It can all stand under it, and we get this very different reading.

Gretchen: I like how you’re doing very helpful gestures right now that nobody can see.

Lauren: It’s for my own cognitive processing.

Gretchen: Make sure you do the gestures when you’re listening as well. This is my suggestion. The thing that I like about scope as a phenomenon is that it’s one of those things that pops up as you’re going about your life if you’ve got your little linguistic lenses on and you’re analysing sentences as you see them. This means that linguists will often have a little pocket full of examples of scope and scope ambiguity. When we were preparing for this episode, I was having dinner with some linguists, and I said, “Hey, anybody have some favourite examples of scope to share?”

Lauren: I’m glad that you’re making it clear this is genuine thing that we enjoy doing is asking people for their favourite examples of scope.

Gretchen: Please send us examples of fun linguistic phenomena. One of them said, in the women’s bathroom in the Georgetown linguistics department – this is an important part of linguistic cultural history – there was a sign that said, “Please make sure to flush. Automatic sensor doesn’t work 100% of the time.” The two readings there – which took me a second because they’re a little bit less funny than the “never saw a dog and didn’t smile” example, I will admit, but the fact that it was found in the wild, you know, has some benefit to it – one is it’s not the case that it always works, so maybe it only works 90% of the time not 100% of the time, which is what the person writing the sign presumably intended.

Lauren: But there’s also a reading that’s like, “It doesn’t work 100% of the time – 100% of the time, this thing does not work.” It is a very bad automatic toilet flush.

Gretchen: Exactly. Might as well not even be there. Somebody had written, apparently, “scope ambiguity hee hee” on this sign in the bathroom of the linguistics department.

Lauren: I love it.

Gretchen: Because this is what we’re like.

Lauren: With negation and reported speech we have either “someone said” or we have a bit of negation that creates this umbrella that goes forward into the sentence to scope over what comes next and how much of what comes next is what can lead to some ambiguity. But I also think about that brief historical fad in 1980s English for putting “not” at the end of a sentence.

Gretchen: Is that something where you’re like, “Here’s some pizza for you – not!”

Lauren: Exactly. I think we’re gonna have to work on your customer service if we’re gonna open this restaurant, Gretchen. But that one is reaching back into the sentence and that is what makes it funny in English because we’re so used to things going forward into the sentence and scoping over what comes after it.

Gretchen: But in principle some other languages must do negation scoping back into the sentence instead of scoping forward into the sentence, just like with recorded speech, right?

Lauren: There’s lot of variation in where negation can pop up in the grammar of a language. I went to visit WALS just to confirm with some survey of a range of different languages, and even though having negation just before your verb is the most common, there are lots of languages that will have the negation right at the very end of a sentence. In fact, something close to 20% of the languages in this survey had that form of negation right at the very end. So, in those languages, it is totally normal for it to go back into the sentence that’s just been said and scope back over what has already been said instead of scoping over what is to come.

Gretchen: You could probably still get some kinds of ambiguity, but maybe a bit of a different set. Thinking about this scoping either forwards or backwards into the rest of the sentence or into the bit of the sentence that came before, it feels like less of a classic round umbrella that scopes equally over your entire body and more like one of those retractable ones at the front of the café that really scopes over in one direction rather than circularly.

Lauren: We should definitely have one at the front of our hypothetical café.

Gretchen: If you’re within the scope of the Scope Shop slope, you can still have soap? I think we’ve got to work on this menu.

Lauren: We definitely got to work on this menu. The cool thing is, if you bring in both reporting and negation, you can get some really brain-hurting ambiguity going on.

Gretchen: There’re some examples of this that you see going around on social media a fair bit because they’re really fun to do lots of different interpretations with, but also, a lot of these sentences are a bit violent or menacing.

Lauren: I think even the ones that aren’t menacing once you start reading them with different stress, which gives rise to different readings, you can’t help but find them a little bit menacing. One that goes around frequently is “I didn’t say he stole the money.”

Gretchen: Okay, let’s try reading this putting emphasis on each word one at a time.

Lauren: “I didn’t say he stole the money.”

Gretchen: Maybe this other person said it.

Lauren: “I DIDN’T say he stole the money.”

Gretchen: You’re trying to put words in my mouth.

Lauren: “I didn’t SAY he stole the money.”

Gretchen: I just showed you all the security camera footage.

Lauren: “I didn’t say HE stole the money.”

Gretchen: Maybe she did.

Lauren: “I didn’t say he STOLE the money.”

Gretchen: Maybe he borrowed it.

Lauren: “I didn’t say he stole THE money.”

Gretchen: Not that big stash of profits, just some petty cash.

Lauren: “I didn’t say he stole the MONEY.”

Gretchen: He stole the car.

Lauren: Each of these gives rise to different readings. Obviously, we can use emphasis in any sentence to change what word we’re focusing on.

Gretchen: But in this case because we have both the “say” and the “didn’t,” it puts emphasis on which parts are we negating and which parts are we reporting the speech of. In combination, that creates this very strong change in meaning when you emphasise one word versus another.

Lauren: They’re really fun. I can definitely see why when you have an example that’s so juicy in terms of the flexibility of the meanings that arise, you often see these doing little circuits on social media.

Gretchen: One of the other examples that goes around on social media pretty often is even more violent. It’s “I didn’t ask you to kill him.” You can try this exercise for yourself on this other sentence if you like.

Lauren: Of course, along with the intonation in spoken language that helps us figure out where the negation is being scoped over, we also have the gestures that we use alongside speech. There is work that shows pretty consistently that, say, maybe a headshake in English for negation or something like a pushing away or a shaking a hand in refusal tends to scope very nicely over the same bit as the grammatical negative form like “not” or “don’t.”

Gretchen: Very nice.

Lauren: We also have gestures when you are in an audio and visual context – unlike this audio-only podcast.

Gretchen: Signed languages also use non-manual markers like eyebrows and shaking head and things like that to do this kind of negation scope and make sure it’s clear when it starts and ends.

Lauren: Alongside reported speech and negation, we also have our classic everything bagel-slash-pizza menu item.

Gretchen: We can also make “everything” ambiguous.

Lauren: That is true.

Gretchen: We’ve already made “everything” ambiguous one way by talking about how much it refers to in a cultural context. We can also make it ambiguous in a more structural way by combining it with words like “some.”

Lauren: True.

Gretchen: The classic example that a lot of people encounter in a semantics class is “Everyone loves someone.”

Lauren: That could be that everyone has at least one person that they love. There might be some overlap, but there’s lots of different people getting that love.

Gretchen: Or it could mean there’s this one person who everybody loves who’s super popular.

Lauren: Oh no, that is gonna get really difficult. I feel very sorry for that someone.

Gretchen: Certain complications in fandom, and maybe they’re too popular. But “Everyone loves someone” can just as validly mean both of those things.

Lauren: Alongside “some,” there are words like “all” and “every” that create this “Exactly how much is being scoped?” ambiguity as well.

Gretchen: Right. There’s another example from the linguist I was having dinner with, which is my friend’s kid got one of those kindergarten worksheets where they have them do exercises to teach them about quantities. The instructions said, “Colour half of all the pigs.”

Lauren: There’s six pigs, and I have to colour three of them.

Gretchen: If you were the kindergarten teacher, you might have assumed that’s what the exercise meant. This kid colours all of the first pig, clearly does a lot of thinking, erases half of the first pig, and then colours half of the remaining five pigs. “Colour half of all the pigs.”

Lauren: I really got to commend that kid for their lateral thinking skills. I mean, they completed the task.

Gretchen: I think this kid has a great future as a linguist. They’d fit right in at the Georgetown linguistics department.

Lauren: Absolutely.

Gretchen: They fit right in in the bathroom of the Georgetown linguistics department. [Laughter] Then you can get really fun examples of these kinds of ambiguity with words like “some” and “every” and “all” sometimes in headlines. I remember seeing, a few years ago, “Someone’s getting a vaccine every 10 seconds.”

Lauren: We’re confused about whether we’re talking about lots of different someones or just one, single someone, aren’t we?

Gretchen: Like, “Wow! This person is gonna be so well protected against COVID, but what about the rest of us?”

Lauren: Ah, yes, that is where we really wanna be careful about whether we have a scope ambiguity or not.

Gretchen: Similarly, there was a headline that went around that was “A woman gives birth in the UK every 48 seconds. She must be exhausted.”

Lauren: Yeah, I am horrified by that one. Sometimes this pops up even with words that we don’t think of as having this kind of scope ambiguity. On social media a while ago, a baby care brand with the slogan “Caring for your baby since 1890,” and someone had just commented, “My 100-plus-year-old baby says thank you, but please let her die now.”

Gretchen: Oh no. So, not caring for your one, individual baby.

Lauren: For your one, individual baby or your generic, ever-changing baby. Gretchen, after all this scope ambiguity in reported speech and negation and words like “some” and “all,” I just wanted to ask, “Are you okay with everything?”

Gretchen: You know, some days, that might be toppings on a kebab. Some days, that might be the entire universe. I’m okay with everything that’s in the scope of this episode, and that’s enough for today. But no onions.

[Music]

Lauren: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode, go to lingthusiasm.com. You can listen to us on all the podcast platforms or lingthusiasm.com. You can get transcripts of every episode on lingthusiasm.com/transcripts. You can follow @lingthusiasm on all the social media sites. You can get scarves with lots of linguistics patterns on them including IPA, branching tree diagrams, bouba and kiki, and our favourite esoteric Unicode symbols, plus other Lingthusiasm merch – like our new “Etymology isn’t Destiny” t-shirts and aesthetic IPA posters – at lingthusiasm.com/merch. My social media and blog is Superlinguo.

Gretchen: Links to my social media can be found at gretchenmcculloch.com. My blog is AllThingsLinguistic.com. My book about internet language is called Because Internet. Lingthusiasm is able to keep existing thanks to the support of our patrons. If you wanna get an extra Lingthusiasm episode to listen to every month, our entire archive of bonus episodes to listen to right now, or if you just wanna help keep the show running ad-free or get a cool sticker in the mail, go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm, or follow the links from our website. Patrons can also get access to our Discord chatroom to talk to other linguistics fans and be the first to find out about new merch and other announcements. Recent bonus topics include inner voice, how to make a vowel chart – with Bethany Gardner – and an episode where we took the “What Episode of Lingthusiasm are You?” quiz. Perfect for picking a starter episode for a friend or deciding what to re-listen to. Can’t afford to pledge? That’s okay, too. We also really appreciate it if you can recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone in your life who’s curious about language.

Lauren: Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our Senior Producer is Claire Gawne, our Editorial Producer is Sarah Dopierala, our Production Assistant is Martha Tsutsui-Billins, and our Editorial Assistant is Jon Kruk. Our music is “Ancient City” by The Triangles.

Gretchen: Stay lingthusiastic!

[Music]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lingthusiasm Episode 91: Scoping out the scope of scope

When you order a kebab and they ask you if you want everything on it, you might say yes. But you'd probably still be surprised if it came with say, chocolate, let alone a bicycle...even though chocolate and bicycles are technically part of "everything". That's because words like "everything" and "all" really mean something more like "everything typical in this situation". Or in linguistic terms, we say that their scope is ambiguous without context.

In this episode, your hosts Lauren Gawne and Gretchen McCulloch get enthusiastic about how we can think about ambiguity of meaning in terms of scope. We talk about how humour often relies on scope ambiguity, such as a cake with "Happy Birthday in red text" written on it (quotation scope ambiguity) and the viral bench plaque "In Memory of Nicole Campbell, who never saw a dog and didn't smile" (negation scope ambiguity). We also talk about how linguists collect fun examples of ambiguity going about their everyday lives, how gesture and intonation allow us to disambiguate most of the time, and using several scopes in one sentence for double plus ambiguity fun.

Read the transcript here.

Announcements:

In this month’s bonus episode we get enthusiastic about the forms that our thoughts take inside our heads! We talk about an academic paper from 2008 called "The phenomena of inner experience", and how their results differ from the 2023 Lingthusiasm listener survey questions on your mental pictures and inner voices. We also talk about more unnerving methodologies, like temporarily paralyzing people and then scanning their brains to see if the inner voice sections still light up (they do!).

Join us on Patreon now to get access to this and 80+ other bonus episodes. You’ll also get access to the Lingthusiasm Discord server where you can chat with other language nerds.

Also: Join at the Ling-phabet tier and you'll get an exclusive “Lingthusiast – a person who’s enthusiastic about linguistics,” sticker! You can stick it on your laptop or your water bottle to encourage people to talk about linguistics with you. Members at the Ling-phabet tier also get their very own, hand-selected character of the International Phonetic Alphabet – or if you love another symbol from somewhere in Unicode, you can request that instead – and we put that with your name or username on our supporter Wall of Fame! Check out our Supporter Wall of Fame here, and become a Ling-phabet patron here!

Here are the links mentioned in the episode:

Wikipedia entry for Everything Bagel

'Shel Silverstein's hot dog and the domain of "everything"' post on Language Log

Wikipedia entry for 'Scop' (an oral poet)

'New publication: Reported evidentiality in Tibeto-Burman languages' post on Superlinguo

Wikipedia entry for Tom Swifty

'Bench in honour of Nicole Campbell, who never saw a dog and didn't smile' post on All Things Linguistic

WALS entry for Feature 144B: Position of negative words relative to beginning and end of clause and with respect to adjacency to verb

'A few notes on negative clauses, polarity items, and scope'

'I didn't ask you to kill him' Learning English post on sentence stress and meaning

'I didn't ask you to kill him' sentence stress example in action by @dheanasaur on TikTok (⚠︎warning, loud sound)

Non-manual Markers in ASL / NMM's

'The Impulse to Gesture: Where Language, Minds, and Bodies Intersect' by Simon Harrison

'Quantifier Scope Jokes' post on All Things Linguistic

'Caring for your baby since 1890' ambiguity post on All Things Linguistic

You can listen to this episode via Lingthusiasm.com, Soundcloud, RSS, Apple Podcasts/iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also download an mp3 via the Soundcloud page for offline listening.

To receive an email whenever a new episode drops, sign up for the Lingthusiasm mailing list.

You can help keep Lingthusiasm ad-free, get access to bonus content, and more perks by supporting us on Patreon.

Lingthusiasm is on Bluesky, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, Mastodon, and Tumblr. Email us at contact [at] lingthusiasm [dot] com

Gretchen is on Bluesky as @GretchenMcC and blogs at All Things Linguistic.

Lauren is on Bluesky as @superlinguo and blogs at Superlinguo.

Lingthusiasm is created by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our senior producer is Claire Gawne, our production editor is Sarah Dopierala, our production assistant is Martha Tsutsui Billins, and our editorial assistant is Jon Kruk. Our music is ‘Ancient City’ by The Triangles.

This episode of Lingthusiasm is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike license (CC 4.0 BY-NC-SA).

#linguistics#language#lingthusiasm#episodes#podcast#podcasts#episode 91#scope#ambiguity#scope ambiguity#linguist humour#SoundCloud

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bonus 86: Inner voice, mental pictures, and other shapes for thoughts

When you think about your daily life -- say, going grocery shopping -- are your thoughts shaped like an inner voice or music, mental images or video, inner feelings or other sensory awareness, or unsymbolized mental impressions? Most people have some combination of these things, but the degree to which you literally visualize a bright red apple or mentally hear yourself saying "and don't forget the apples" is something that varies widely from person to person. But until we start asking about it, it's easy to assume that other people's thought-shapes are formed just like our own, and that any impressions to the contrary are just people speaking metaphorically.

In this bonus episode, Gretchen and Lauren get enthusiastic about the forms that our thoughts take inside our heads. We talk about an academic paper from 2008 called "The phenomena of inner experience", which asked 30 university students to write down the shape of their thoughts at random intervals throughout the day, and how their results differ from the 2023 Lingthusiasm listener survey questions on your mental pictures and inner voices. We also talk about more unnerving methodologies, like temporarily paralyzing people and then scanning their brains to see if the inner voice sections still light up (they do!).

Listen to this episode about the shapes of thought, and get access to many more bonus episodes by supporting Lingthusiasm on Patreon.

#linguistics#language#lingthusiasm#podcast#bonus#bonus episodes#bonuses#podcasts#inner voice#inner thoughts#inner monologue#survey results

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

In honour of Vowel Month please take this highly serious poll about your favourite vowels!!!

tumblr polls only have 10 options so we're going with the weird bois, sorry schwa, it's not my fault danny j didn't love you

(don't know what these symbols mean? vote on vibes or listen to our friend danny jones saying all the vowels on an old school record here)

572 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transcript Episode 90: What visualizing our vowels tells us about who we are

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘What visualizing our vowels tells us about who we are'. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Gretchen: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Gretchen McCulloch.

Lauren: I’m Lauren Gawne. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about plotting vowels. But first, we have a fun, new activity that lets you discover what episode of Lingthusiasm you are. Our new quiz will recommend an episode for you based on a series of questions.

Gretchen: This is like a personality quiz. If you’ve always wondered which episode of Lingthusiasm matches your personality the most, or if you are wondering where to start with the back catalogue and aren’t sure which episode to start with, if you’re trying to share Lingthusiasm with a friend or decide which episode to re-listen to, the quiz can help you with this.

Lauren: This quiz is definitely more whimsical than scientific and, unlike our listener survey, is absolutely not intended to be used for research purposes.

Gretchen: Not intended to be used for research purposes. Definitely intended to be used for amusement purposes. Available as a link in the show notes. Please tell us what results you get! We’re very curious to see if there’re some episodes that turn out to be super popular because of this.

Lauren: Our most recent bonus episode was a chat with Dr. Bethany Gardner, who built the vowel plots that we discuss in this episode.

Gretchen: This is a behind-the-scenes episode where we talked with Bethany about how they made the vowel charts that we’ve discussed, how you could make them yourself if you’re interested in it, or if you just wanna follow along in a making-of-process style, you can listen to us talk with them.

Lauren: For that, you can go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm.

Gretchen: As well as so many more bonus episodes that let us help keep making the show for you.

[Music]

Gretchen: Lauren, we’ve talked about vowels before on Lingthusiasm. At the time, we said that your vocal tract is basically like a giant meat clarinet.

Lauren: Yeah, because the reeds are like the vibration of your vocal cords – and then you can manipulate that sound in that clarinets can play different notes and voices can make many different speech sounds. They’re both long and tubular.

Gretchen: We had some people write in that said, “We appreciate the meat clarinet – the cursed meat clarinet – but we think the vocal tract is a little bit more like a meat oboe or a meat bassoon because both of these instruments have two reeds, and we have two vocal cords. So, you want to use something that has a double vocal cord.”

Lauren: I admit I maybe got the oboe and the bassoon confused. I thought that the oboe was a giant instrument. Turns out, the oboe is about the size of a clarinet. Turns out, I don’t know a lot about woodwind instruments.

Gretchen: I think that one of the reasons we did pick a clarinet at the time is because we thought, even if it’s not exactly the same, probably more people have encountered a clarinet and have a vague sense of what it looks like than an oboe, which you didn’t really know what it was. I had to look up how a bassoon works. We thought this metaphor might be a little bit clearer.

Lauren: Yes.

Gretchen: However.

Lauren: Okay, there’s an update.

Gretchen: I have now been doing some further research on both the vocal tract and musical instruments, and I’m very pleased to report that we, in fact, have an update. Your vocal tract is not just a meat clarinet, not just a meat bassoon, it is, in fact, most similar to a meat bagpipe.

Lauren: Oh, Gretchen, you found something more disgusting. Thank you?

Gretchen: I’m sorry. It’s even worse.

Lauren: Right. I guess the big bag – a bagpipe is made of a bag and pipes – the bag acts like your lungs. The lungs send air up through your vocal folds as they vibrate to make the sound. You do have a bag of air, just like in the human speech apparatus.

Gretchen: That’s a good start. What I didn’t know until I was doing some research about bagpipes – because the lengths that I will go to for this podcast have no bound – is that a bagpipe actually has reeds inside several of the pipes that extrude from the bag.

Lauren: Because there’s multiple sticking out in different spots.

Gretchen: There’s the one that you blow into, which doesn’t have a reed, but then the other ones, there’s the one with the little holes on it that you twiddle your fingers on and make the different notes, and then there’s also some other pipes up at the top. They also have reeds in them. Those reeds are just tuned from the length to a specific level. You know when you hear someone start playing the bagpipes and there’s this drone? [Imitates bagpipe sound] The sort of single note? That’s because of the note those reeds are tuned to in the other pipes that don’t have the holes in them.

Lauren: Ah, they’re not just decorative.

Gretchen: Right. They have this function of giving this harmony to the melody that’s being played on the little pipe with the holes in it, which is technically known as the “chanter,” but this is not a bagpipe podcast despite appearances to the contrary. We will link to some people on YouTube telling you more than you ever wanted to know about how bagpipes work if you want to go down that rabbit hole. But if you had an extra pair of hands or two, or a couple people helping you sort of reaching around your shoulders – this metaphor’s getting weirder by the minute – and you cut a bunch of little holes in the other sticking-up-the-top pipes –

Lauren: You would have less droning, and you could play multiple melodies or multiple notes at the same time. Hm.

Gretchen: At the same time. With this, you could make a bagpipe play something very close to vowels.

Lauren: Ah, cool!

Gretchen: This is so cursed.

Lauren: I mean, yes. Before we even talk about making it out of meat – it’s deeply, deeply cursed – it kind of reminds me of this instrument from the early 20th Century called the “voder.”

Gretchen: Would I pronounce that “vo-DUH” or “vo-DER”?

Lauren: With the R at the end.

Gretchen: Okay, “voder.”

Lauren: Thank you, convenient rhotic speaker here.

Gretchen: I’m glad to be of service.

Lauren: It kind of looked like something between a little stenographer’s keyboard and a piano, and with a whole bunch of finger keys and foot pedals you could manipulate it to make something that sounds like human speech.

Gretchen: Ah, wow. And this is pretty old?

Lauren: It’s from like the 1930s. There’s a little, short video snippet in one of the links in the show notes.

Gretchen: You could play these chords, and also have some consonants somehow, and end up with something that sounds like a synthetic human voice.

Lauren: Yeah. A lot of the early computer speech synthesis, as well, was actually quite good at making things that sounded like vowels. It turns out a lot of the consonant things are a little bit harder to do, but the very basic sound of vowels, as you say, you could play it with just a few bagpipes very carefully re-engineered.

Gretchen: I guess if you’re looking at instruments that can play multiple notes at the same time, we could also say that the human is like a meat piano.

Lauren: Right.

Gretchen: Or at least you could make vowels on a piano by doing a sufficiently complicated sequence of weird chords, like notes at the same time.

Lauren: I mean, we also have an instrument that’s known as the human voice. Humans are very good at singing. We possibly don’t have to engineer all these cursed things to get to that.

Gretchen: Okay. Let’s talk about the human voice as itself. We start with the vocal cords or folds. The tenseness or looseness of the vocal folds is what produces pitch. Then they go through the throat, which we can think of as one tube. Then they go through the mouth cavity, which we can think of as a second tube. Each of these tubes bounces around the sound in different ways to add two additional notes – one from the throat, one from the mouth – onto the sound that’s coming out, which is what makes it sound like a vowel to us.

Lauren: You can map the physics of air moving through the throat space and the mouth space as it comes out to pay attention to the differences between different sounds.

Gretchen: If you’re taking a physics diagram or a diagram of the acoustic signal and saying, “Which pitches are coming out of the mouth, which frequencies are coming out of the mouth that are being produced by these two chambers?” then you can see what those are, and you can do stuff with those diagrams once you’ve made them.

Lauren: The seeing bit is spectrograms, which we looked at in an earlier episode and played around with making different sounds and how they look in this way of visualising it where you have all these bands of strength and information that you can see vary depending on the different sounds that you made. That’s because of those different ways that we manipulate and play around with the air as its coming out of our mouth.

Gretchen: The first band that comes out is just the pitch of the voice itself. The lowest one is what we hear as the pitch of the sound, but I can make /aaaa/ and I can make /iiii/. Those are the same set of pitches but on different vowels.

Lauren: There’s something more than pitch happening there.

Gretchen: There’s something more than pitch happening. There’s two more notes – sounds – that come out at the same time. If the throat chamber is large because the tongue is fairly high and far forward, then this sound that’s the next one after the pitch, which was call “F1,” is low. Then if the mouth is quite open, and the lips are spread, the mouth chamber is quite small, so that sound is quite high, so the next sound, “F2,” is high pitched. If you put your tongue far forward, and your lips spread, you get /i/. The first of these dark bands is low; the second of them is high. That produces the sound that we hear as /i/. Whereas, by comparison, if we make the sound /u/, the throat chamber is still large because the tongue is quite high, but now, the mouth chamber is big because we have the lips rounding that make it big – /u/. Now, F1 is low, and F2 is also low, and we’re hearing the sound /u/.

Lauren: We have a very clear way of telling from those signals in the spectrogram, if we look at it, the difference between an /i/ and an /u/, even if we can’t hear it, we can see it on the spectrogram. This is where you begin to read spectrograms.

Gretchen: Or if we want to start measuring spectrograms very precisely, we can start doing this. We can also start seeing, okay, is /i/ when I make it the same as the /i/ when you make it?

Lauren: They’re similar enough that we recognise it as the same sound. If we both say, “fleece.”

Gretchen: “Fleece.”

Lauren: You say, /flis/. I say, /flis/.

Gretchen: /pətɛɪtoʊ pətatoʊ/. I think they sound pretty similar.

Lauren: Mine is maybe a little bit higher. I really pushed my tongue forward and up. It’s a very Australian thing to do.

Gretchen: We can actually record some people making all of the vowels and compare their measurements for these two different bands of frequency and see how similar two people’s vowels are to each other.

Lauren: Depending on the quality of your recording, you can see a lot more happening there as well. There’re all the properties that mean that we can tell your voice from my voice, or my voice from someone who has exactly the same accent because we have all these other features. It’s very different to if you record, say, a whistle or one of those tuning forks that people use to tune instruments because they are giving a clean single note.

Gretchen: A pure tone that’s just one frequency, one pitch, not several pitches all at the same time that we then have to smoosh together and interpret as a vowel sound.

Lauren: That’s what gives the human voice its richness. If a human voice sings the same note as a clarinet and an oboe, which are definitely two completely different woodwind instruments, there’s all these extra bits and things in the spectrogram that you can pick up the difference in the quality or just use your ears – also another possibility.

Gretchen: Yeah. If you wanna do detailed acoustic analysis on it – which is kind of fun and can tell us more precise things about the differences between how different people speak, which is neat – then you have this very precise way of measuring it by converting it into a visual graph/chart thing or a vowel plot rather than just listening to someone and being like, “Uh, these sound pretty similar. I dunno. I guess they’re a bit different. How are they different? Hmm.” Sometimes, being able to do it with numbers is easier.

Lauren: In the era before we had computers to create spectrograms and take these measurements, people did use their ear. The best phoneticians had this amazing ability to tell the difference between really, really subtly-similar-but-slightly-different sounds.

Gretchen: And they’re so well trained in being able to hear the difference between “Oh, you’re saying this, and your tongue is a little bit further forward than this other person who’s saying this with their tongue a little bit further back,” but if you’re not very good at hearing tongue position out of sounds, you can also produce some stuff and make the machines tell you some numbers about it, which can be easier with a different type of training.

Lauren: When we talk about the position of the tongue and how open the mouth is, we can use a plot to map where in the mouth these things are happening. That’s called the “vowel space.” We made a lot of silly sounds when we talked about that many episodes ago.

Gretchen: The vowel space goes from /i-ɛ-a/ on one side.

Lauren: That’s all up the front of your mouth, and it’s just going from being more close to more open.

Gretchen: /i/ to /ɛ/ to /a/, but you can through all these subtle gradations between them, and through /u-ɔ-ɑ/ at the back.

Lauren: That’s from all the way up the top at the back to open at the back.

Gretchen: You can draw a diagram of this which is shaped like square that’s been a bit skewed. It’s wider at the top than at the bottom. It’s known as the “vowel trapezoid” because the mouth is not perfectly shaped like a square. The jaw can hinge open.

Lauren: Only so far.

Gretchen: Only so far.

Lauren: Because this represents how you say or articulate these sounds, this is known as “articulatory phonetics.”

Gretchen: But then because you’re articulating a thing that goes into a sound that we can also analyse as the sound itself, these ways that you can articulate things map onto things that show up in the sound itself. Analysing that is called “acoustic phonetics.”

Lauren: Because you’re paying attention to the acoustic properties – the sound properties.

Gretchen: The really nifty thing is that this vowel chart that we’ve made from over 100 years ago, linguists, before they had computers, were like, “Here’s what I think the articulatory properties of the vowels are based on my mouth and my ear and some other people’s mouths and ears.” You can actually map very precisely this acoustic thing. Once we had computers, you can make them correspond to each other in this way that – you hope it works because, obviously, people do understand the vowels, but it actually does work when you start measuring things as well.

Lauren: I had always wondered whether it was just a coincidence that the articulation – where you put your mouth – and the acoustic information about the F1 and F2 with the spectrogram, but explaining it in terms of F1 and F2 are the way you change the shape of your throat and your mouth that leads to these changes in the acoustic signal, you can see how the articulation and the acoustics come together, and you get a similar type of information across both of them.

Gretchen: Absolutely. I think it’s really neat that there’s this relatively straightforward correspondence. There’s also, you know, an F3 that also does other stuff because there’s other more squishy bits of your mouth, and we’re not getting into them.

Lauren: There’s also a bunch of flip-flopping of X- and Y-axes that you need to do that Bethany kindly walked us through in the bonus episode.

Gretchen: Because these diagrams were created in an era before they were doing the computer acoustics. Sometimes, I think about the alternate version of what phonetics would look like if we’d started doing it with computers right away, and how there’s all this analogue stuff that’s residual based on human impressions, and how our vowel charts might be completely rotated if we had just started doing it with computers the whole time.

Lauren: But then we’d have to imagine ourselves standing on our heads to say anything, so I’m glad they are the way they are.

Gretchen: That’s true. When you’re talking about vowels, it’s an interesting challenge with English because there’s lots of different dialects of English, varieties of English, ways of speaking English, and, generally speaking, we’re pretty good at understanding other accents. One of the big factors that accents vary on, though, is the vowels.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: If you’re getting people to record a word list to do some vowel analysis on, what you might wanna do is have them record a bunch of words that all begin and end with the same consonant insofar as possible.

Lauren: Because vowels are very sweet and easily influenced. They’re very easily influenced by the consonants that are next to them. You have to make sure that they’re all kept in line and not influenced by what’s happening around them by giving them all the same context.

Gretchen: They’re very susceptible to peer pressure. You can have people say something like, “beat,” “bet,” “bit,” “bought,” “boot,” all of this stuff between B and T.

Lauren: I learnt to record between H and D: “hid,” “had,” “hoo’d,” “hawed.” Some of those words are less, uh, common – frequent – than others, but again, a really consistent environment.

Gretchen: But this also, obviously, causes problems for when you want to talk about the particular vowels in a given accent or in a given variety because if you go around saying, “Oh, well, the /hoɪd/ vowel” or something like this, how do you know if that’s a Cockney person saying, “hide,” or it’s me saying “hoyed,” or something else because all your consonants are the exact same, and there’s nothing to let you figure out what the original word is.

Lauren: Someone did come up with a solution for this. That person’s name is John Wells.

Gretchen: John Wells is this British phonetician who I’ve never actually met in person, but I feel like I know him because I used to read his blog back when he posted more actively.

Lauren: He used to write his blog in the International Phonetic Alphabet, which means that if you read the IPA, you would be reading it in John Wells’s voice.

Gretchen: You absolutely would be. This was a challenge that I used to set to myself. Sometimes, he also wrote in Standard English orthography, to be fair, but sometimes he would just write a whole blog post in IPA, and you’d be like, “Cool, I guess I’m reading this out loud to myself and hearing John Wells’s accent and speaking it like him,” which was really neat. In the 1980s, John Wells was like, “Hey, it’d be really useful if we had a way to refer to sound changes that happen in different English varieties,” which often happen to – like, all of the times you say the /ɪ/ vowel are a little bit more like this or like that, depending on the accent.

Lauren: I think it was very personally motivated because he was writing a book called “Accents in English.” It gets very difficult in a book, especially, but even in an audio recording, to be like, “the /ɪ/ vowel,” “the /u/ vowel.”

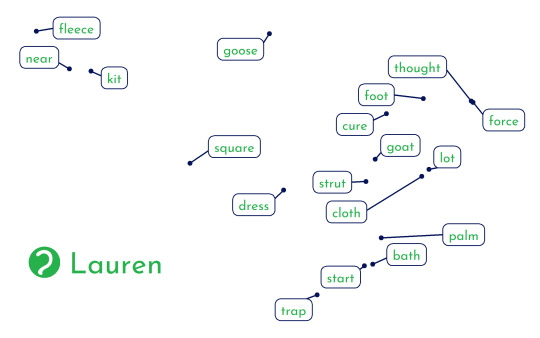

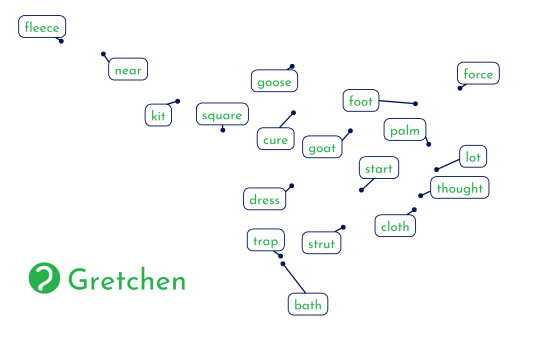

Gretchen: Right. You could use the International Phonetic Alphabet to refer to the specific vowel that people are making. But if you want to say, “People in this area realise this vowel as that, and people in this other area realise the same vowel as something else,” how do you refer to that thing that’s the macro-category of vowel that people would consider themselves to be saying the same word, but the specific way they’re realising it is different? He came up with what he called “the standard lexical sets,” which are now also called, “Wells Lexical Sets,” possibly John Wells’s greatest legacy, which is a bunch of words that are, crucially, easy to distinguish from each other based on the surrounding consonants that you can say when you’re giving a talk – like you can say, “the ‘kit’ vowel,” or “the ‘goose’ vowel,” or “the ‘fleece’ vowel,” and people know that the “kit” vowel refers to the specific sound because there’s no other “keet” word in English that it could be confused with.

Lauren: John Wells was somewhat self-deprecating when he was talking about this, and he was like, “I just kind of came up with it in a week where I had to write this bit of the book, and it’s weird to think that they’re still in use now,” but it was based on years of insight into the different ways different varieties of English realise different vowels and the balance he was trying to strike.

Gretchen: He has this charming blog post from 2010 where he’s like, “Anybody’s welcome to use them. I don’t claim any copyright. Maybe this is my legacy now, I guess.” He does actually put quite a bit of thought into the sets because they’re words that can’t be easily confused for each other. Sometimes, that means the words are a little bit rare. You have “fleece.” You might think, “Well, why not use ‘sheep’ because surely that’s more common. People say that.”

Lauren: But “ship” and “sheep” are very hard to distinguish in some varieties of English.

Gretchen: Right. If you had “sheep,” it could be confused with “ship,” whereas if you have “fleece” and “kit,” there’s no “flice” or “keet” for them to be confused with.

Lauren: Good nonce words to add to your collection.

Gretchen: Thank you. Similarly, for people like me where I make the vowels in “caught,” as in the past tense of “catch,” and “cot,” as in a small bed, the same. If I talk about /cɑt/ and /cɑt/, people are like, “I dunno which one you’re talking about because you say them both the same.” And I’m like, “Great, neither do I.”

Lauren: You mean when you’re talking about /cɑt/ and /cɔt/.

Gretchen: Hmm. Yes, see, you don’t have that “caught/cot merger.”

Lauren: Very easy for me, but it’s much easier to be able to say /θɔt/ and /lɑt/ – much more distinct for me to perceive with you because they don’t have merged equivalents.

Gretchen: “Thought” and “lot” are much more distinct because the consonants are different. You don’t need to be relying only on the vowels. Some of these words are just super fun. Can we read the whole Wells Lexical Sets? There’re not very many of them.

Lauren: Sure. Let’s take turns in going through each of the words.

Gretchen: All right.

Lauren: So, you can hear the differences in the way we pronounce each of these vowels.

Gretchen: /kit/.

Lauren: /kit/.

Gretchen: / dɹɛs/.

Lauren: / dɹɛs/.

Gretchen: / tɹæp/.

Lauren: /tɹæp/.

Gretchen: /lɑt/.

Lauren: /lɑt/.

Gretchen: /stɹʌt/.

Lauren: /stɹʌt/.

Gretchen: /fʊt/.

Lauren: /fʊt/.

Gretchen: /bæθ/.

Lauren: /bɑθ/.

Gretchen: Ooo, very different.

Lauren: We’ll come back to that one.

Gretchen: /klɑθ/.

Lauren: /klɑθ/.

Gretchen: /nɛɹs/.

Lauren: My Australian English speaker in me is already immediately prepared for /nɛːs/.

Gretchen: So, non-rhotic. Very good.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: /flis/.

Lauren: /flis/.

Gretchen: /fɛɪs/.

Lauren: /fɛɪs/.

Gretchen: /pɑm/.

Lauren: /pæm/.

Gretchen: Ooo, very different. /θɑt/.

Lauren: /θɔt/.

Gretchen: Also, very different. We’ll come back to this. /goʊt/.

Lauren: /gəut/.

Gretchen: Bit different. /gus/.

Lauren: /gus/.

Gretchen: /pɹəɪs/.

Lauren: /pɹæɪs/.

Gretchen: Bit different. I have Canadian raising there. We’ll get back to that. /t͡ʃoɪs/.

Lauren: /t͡ʃoɪs/.

Gretchen: /moʊθ/.

Lauren: /mæʊθ/.

Gretchen: Also, we’ll get back to that. /niɹ/.

Lauren: /nɪɑ/.

Gretchen: /skwɛɹ/.

Lauren: /skwɛɑ/.

Gretchen: /stɑɹt/.

Lauren: /stɑːt/.

Gretchen: /nɔɹθ/.

Lauren: /nɔːθ/.

Gretchen: /fɔɹs/.

Lauren: /fɔːs/.

Gretchen: /kjʊɹ/.

Lauren: /kjʊɑ/. I’m only slightly hamming up my Australian English diphthongs there.

Gretchen: That whole set with the Rs where I’m like, “These are just the same sounds, but now there’s an R,” you’re like, “No, these are really different diphthongs.”

Lauren: /kjʊɑ/.

Gretchen: /kjʊɑ/. /kjʊɹ/.

Lauren: Taking you on a journey of my whole mouth.

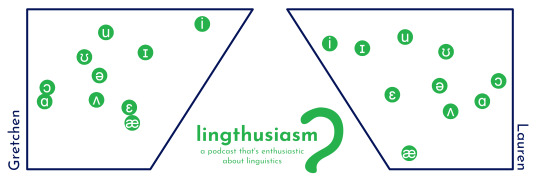

Gretchen: One thing you could do if you’re trying to compare mine and Lauren’s vowels is you could listen to us saying them and being like, “Yeah, those sound kind of different in some places.” But another thing we could do, is we could draw some diagrams.

Lauren: That’s what we did.

Gretchen: Yes!

Lauren: We were very grateful that Dr. Bethany Gardner – who is a recent PhD in psychology and language processing at Vanderbilt University in Nashville in the USA – took the time to work with us to take recordings of us saying words and plotting the vowels onto a vowel plot.

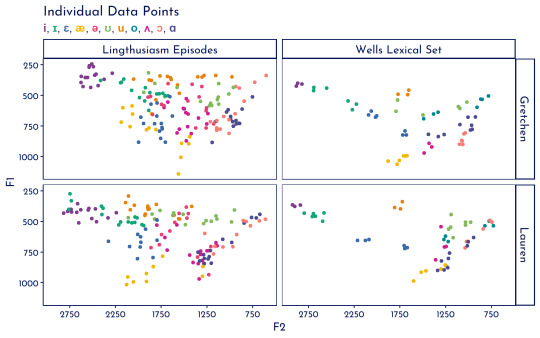

Gretchen: Now, we can look at our vowel plots and compare our vowels to each other. We have a whole bonus episode with Bethany about how we made these graphs with them. For the moment, let’s just look at them and compare them with each other and say some things about the results.

Lauren: We sent Bethany recordings of us reading the Wells Lexical Sets, much the way we did just then.

Gretchen: Less giggling though.

Lauren: We did record them a little bit more professionally, but they also used some processes to scrape data of equivalent word recordings from episodes of Lingthusiasm using our transcripts – turns out, another use of our transcripts!

Gretchen: Get people to analyse your vowels for you. It’s so cool!

Lauren: You can see the difference between clearly spoken vowels where we’re really focusing on them and then that really compelling influence that other sounds have on vowels that drag them all over the space.

Gretchen: Yeah. I’m looking at the first set of graphs for each of us, which are the Wells Lexical Sets, and my vowels are a lot more consistent in them. When I make /i/ and /ɪ/ and /u/, all the points are quite clustered in one spot – because we said everything several times – but I seem to be hitting quite a consistent target there. Whereas when I look at Bethany’s vowel plot of me from the Lingthusiasm episodes, there’s way more stuff there, and I’m way more spread out. My vowels are less consistent with each other because I’m producing them in several words. They tested several different words. I’m just producing them in running speech where things merge into each other a lot more rather than this very clear word list style.

Lauren: And human ears and brains are so good at disambiguating things that might be very close to each other in the plot, but in a running sentence, we can hear them quite clearly for the words that they are.

Gretchen: Right. My “goose” vowel and my “foot” vowel – /gus/ and /fʊt/ – are almost totally distinct from each other when I’m reading a word list. There’s very little overlap in terms of how I’m saying them. But when I’m saying them in running speech, apparently there’s a lot of overlap because I’m probably saying something like, “Oh, go get the goose,” /gʊs/, rather than /gus/ with that really clear /u/.

Lauren: There’s no other word I’m gonna confuse “goose” with, or even if I did, in context, I’d know what thing you’re expecting me to go get.

Gretchen: Right. Even if I’m saying something like, “dude,” you’re not gonna confuse that for “dud.” I’d be saying them in different contexts.

Lauren: The nice thing is you can see, especially from our clearly spoken word lists, that we are speaking a language where the vowels are in a similar place, but there are some slight differences. You can actually start to get the hang of the differences in the way different varieties of English tend to use the vowel space from this information.

Gretchen: One of the things I noticed about your vowel plot, Lauren – and this is a feature of Australian English – is that your “kit” vowel and your “fleece” vowel are very close to each other, especially in episode speech rather than word list speech.

Lauren: Yeah, “kit” and “fleece,” for me, are both really far forward. You’re using other features like length or tenseness to really disambiguate them. People struggle to do it.

Gretchen: Or just in context. I noticed when I was visiting Australia that people would say things like /bɪːg/, and I’d be like, “Oh, okay, I would say that as /bɪg/.”

Lauren: It’s a pretty classic feature of Australian English. It does remind me of one of the most embarrassing times someone misheard me when I was living in the UK. I was talking about how I used to be on a team with my friends for social netball. This person was not listening that well, and it was a noisy environment, and they thought that I had said, “nipple.”

Gretchen: Oh, no!

Lauren: /nɪpl̩/ and /nɛtbɑl/.

Gretchen: /nɛtbɑl/, /nɛtbɑl/, whereas I think my /ɪ/ and /ɛ/ vowels, my “kit” and “dress” vowels, are pretty distinct from each other. They don’t really overlap.

Lauren: Whereas all of Australian English is really far forward. It tends to be quite high. The British English speaker – I don’t know what sport they thought we play in Australia, but there was a moment of deep confusion.

Gretchen: These are the types of things that you can find out when you get your vowels done the way sometimes people – I think there’s a trend on Instagram right now to get your colours done, you know, find out whether you’re a “winter” or a “soft spring” or something like this.

Lauren: I’m an Australian English “kit”-fronting.

Gretchen: Yeah. What are your vowels? What does this say about where you’re from? Is there anything you noticed about mine?

Lauren: I think, for you, definitely what becomes clear is that “caught/cot merger,” or, as I like to think about it, the “Gawne/gone merger.”

Gretchen: Ah, the “Gawne/gone merger.”

Lauren: I can tell if people have it if my name and the word “gone” sound the same.

Gretchen: The past participle of “go.”

Lauren: It’s very salient for me. The cot/caught merger is so famous, people don’t use the Wells Set terms for it. They just refer to it as “caught/cot.”

Gretchen: But you could also call it the “thought/lot merger” or the “lot/thought merger.” I never know which one goes first because I literally just think of these as being said the same.

Lauren: You can see evidence. We’re not imagining that you’re merging them. You are physically merging them in the vowel space.

Gretchen: I’m literally saying them as the same thing. I was always confused about the “thought” vowel when I was learning the International Phonetic Alphabet because I was like, “I can’t figure out how to make a sound that is somewhere in between this sound in ‘lot’ and ‘thought’ but doesn’t go all the way up to the /oʊ/ in ‘goat’.” It doesn’t feel like there’s anything between them for me. That’s true. The vast majority of Canadians have “thought” and “lot” merged. But unlike at least some Americans, we don’t have them merged low; we have them merged high. I have “thought” and “caught,” and in order to produce the other vowel, I had to actually produce something lower in my throat – like /θɑt/ /cat/ which sounds very American to me – I had to produce this lower sound because there was no space between “thought” and “goat.” They’re very close to each other. In fact, the thing that I wasn’t producing was /ɑ/, the really low one, that sort of dentist sound.

Lauren: Yeah. Movements and mergers can happen in all kinds of different directions. The merging of “cot” and “caught” also explains why it took me a very long time to understand that “podcast” is a pun because it’s meant to be a pun with “broadcast,” and /pɑd/ and /bɹɔːd/.

Gretchen: /pɑdkæst/ and /bɹɑdkæst/. It’s the same vowel for me.

Lauren: Whereas it works as a pun for you. That was very satisfying to learn that’s why that’s meant to be a pun.

Gretchen: The pun that I didn’t get based on my accent – and this is to do with the “price” and “mouth” vowels – I didn’t realise that “I scream for ice cream” was supposed to be a pun.

Lauren: Oh, because the raising that you have in Canada means that it doesn’t work that way, whereas /ɑɪ skɹim fə ɑɪ skɹim/.

Gretchen: Right, you have the same vowel in those – or the same diphthong – but for me, “I scream for ice cream,” those are very different. In “choice” and “price,” I have different vowels than I would have in “choys” and “prize” – if “choys” was a word.

Lauren: “Bok choys” – multiple.

Gretchen: “Bok choys” – yeah, several of them. And “prize.”

Lauren: Returning to “podcast” but moving to the other end of the word, /kɑst // kæst/ as a distinction is so famous in mapping varieties of British English that people talk about /bɑθ // tɹæp/ distinctions all the time.

Gretchen: I hear of it as called the “bath/trap split,” but as you can hear, the “/bæθ // tɹæp/ split,” I just say them both the same.

Lauren: Whereas in Australia, Victorians traditionally would say /kæsl̩/ like “trap,” and people further north and in the rest of the country could say, /kɑsl̩/ –

Gretchen: Like “bath.”

Lauren: So, whether you’re a /kɑsl̩/ or a /kæsl̩/ shows this “bath/trap split” as well, to the point where, in New South Wales, you get the city of “New /kɑsl̩/,” but in Victoria, you have the town of “/kæsl̩/ Main.”

Gretchen: Ooo, this “castle” distinction from the “trap/bath split” – I think sometimes when I’m trying to do a fake British accent, I will just make all of my “traps” and “baths” into /tɹɑps/ and /bɑθs/.

Lauren: Right, okay. You know there’s something happening there, and you haven’t quite landed – because it does vary.

Gretchen: Well, then they’re not different categories for me because it’s all one category, and I push them all forward rather than moving half of them because I don’t know which half to move.

Lauren: I find it very satisfying listening to “No Such Thing as a Fish,” because they talk about the /pɑdkɑst/ or the /pɑdkæst/, and their guests do, depending on whether they’re from Southern England or more in the midlands and north where they tend to say /kæst/ instead of /kɑst/.

Gretchen: I have literally never noticed this distinction. I’ve also listened to many episodes of “No Such Thing as a Fish” because you made me start listening to them back in the day, and I’ve never noticed that they say anything different because it’s just not something I pay attention to.

Lauren: It’s so salient for me as a Victorian English speaker, but I notice it all the time. There would be a really fun mapping variation activity to do listening through to Fish – turns out I just listen to it and don’t get distracted by that too much.

Gretchen: Well, if you want to commission Bethany to make graphs of their vowels, I’m sure that’s an option.

Lauren: I love how Wells’ lexical set has just entered – in many ways, the “bath/trap split,” it means you get all these other terms like “goose fronting,” which is just great as a term.

Gretchen: I love how vivid these words are. Things like “fleece” and “goose” and “goat,” they’re very common animal nouns that are quite vivid.

Lauren: And there’re definitely linguists who have dressed up as Wells Lexical Set items for Halloween. It makes a great group Halloween costume.

Gretchen: Oh my gosh, my favourite one of these was from North Carolina State University. They got the whole department, and they each dressed up as one member of the Wells Lexical Set. Someone was a “kit.” They dressed like a cat. Someone dressed like a goose, and someone dressed like a cloth or a fleece. Then they stood in the positions to create the vowel diagram. They posted a photo on the internet. You can see it. We will link to it. It’s really great.

Lauren: Magic. You and I also once had a project where we plotted the Wells Lexical Set using emoji.

Gretchen: That was your project.

Lauren: I did the making the joke. You did the graphic design. It was a good team project.

Gretchen: Okay, that’s fair. That’s fair. I feel like I remember you being the instigator of this.

Lauren: Shenanigans were shenaniganed.

Gretchen: You can get a goose emoji and a goat emoji, and you can map the vowels in there as well.

Lauren: And “Goose fronting” – because we’re talking about moving the tongue further forward or back or up and down in the vowel space – I have quite fronted vowels as an Australian English speaker for my front vowels. So, “goose” – I’ve already got it quite far forward compared to you. You can see that in the diagrams.

Gretchen: I think my “goose” – my goose is also cooked – my “goose” is also fronted. Because I think Canadian English is also undergoing goose fronting. There’s a lot of different regions that are all simultaneously fronting their geese – no, not their “geese,” fronting their “gooses.”

Lauren: Fronting their “gooses.” I feel like the really stereotypical example is from California, particularly in the lexical item “dude.”

Gretchen: “Dude” – sort of like a surfer pronunciation of “duuude.”

Lauren: “/du̟d/ you’re a fronted /gu̟s/.”

Gretchen: If you compare that with like /dud/, which would be less fronted, /dud/ sounds like you’re more of a fuddy duddy, and /du̟d/ sounds like you’re “so /ku̟l/.”

Lauren: Yeah, I mean, there’re other things happening there as well because I found a paper while researching this where someone looked at 70 years of Received Pronunciation, which is that incredibly stuffy, British, old-fashioned newsreader voice. Apparently, goose fronting is happening in that variety as well.

Gretchen: Oh, so if the Queen was still alive, she’d be fronting her “goose” as well?

Lauren: Quite possibly. Gooses are being fronted all over the place.

Gretchen: All over the English-speaking world. One of the things that can happen if you’re getting your vowel tea leaves read is you can say things about region. Another thing that looking at a vowel plot can do – because vowels just contribute so much to our sense of accent – is it can say things about gender. One of the cool studies that I came across about this is there’re studies of kids. People often assess someone’s gender based on their voice. If someone’s on the phone, you may have an idea about their gender. You may also have an idea of their age. Part of this is based on vocal tract size. Kids’ voices are high pitched because kids’ heads and throats and larynxes are smaller than adults.

Lauren: The cool thing is there’s no gender difference in that until puberty. People who go through a testosterone-heavy puberty tend to grow larger vocal tracts and tend to have deeper pitches. I mean, not in the scheme of things where they’re so completely different. There’s so much overlap. But we’re really tuned into these subtle differences. But before that age, anything that kids are doing different, it’s nothing to do with what’s happening with the meat pipe and everything to do with what’s happening with the social performance of gender, which is to do with your culture.