Photo

What is the Turkish locative case?

The simplest English translation for the Turkish dative case is “in,” “on,” or “at,” but it is a little more complicated than just that. If we generalized, we could say it is about location. Wow, who could have guessed the locative case is about location?

How do form the dative case? You will add one syllable to the end of your Turkish noun that will vary according to vowel harmony. You will use -t- or -d-, and you will use -a or -e. More specifically, all the possible endings for the locative case are: -da, -ta, -de, -te. Which you will use will depend on the final syllable of the noun.

Technically, there is buffer -n- included with the locative. It will appear only when the noun is possessed by him, her, or them. A 3rd person possessive gets a -ı or -sı, which means it ends with a vowel. However, you cannot add -da; you must add -nda.

kedi > kedisi > kedisinde

cat > his cat > on his cat

ev > evi > evinde

house > his house > at his house

para > parası > parasında

money > his money > on his money

Please notice the ambiguity of evinde. It can be “at his house” or “at your house.” Be careful.

Here are the 5 rules to know when to use the Turkish dative case:

Rule 1: adverbial of place – you did it where?

In a sentence with a verb, you usually need to describe where it is happening. You will use the Turkish locative case.

Arkadaşımın evinde uydum.

= I slept at my friend’s house.

Kedi mutfakta yedi.

= The cat ate in the kitchen.

Rule 2: adverbial of time – you did it when?

Time is critical, and you will usually use the Turkish locative case to mark it.

Son zamanlarda daha fazla Türkçe öğrendim.

= Recently (literally, at the last times) I studied more Turkish.

Arkadaşım sabahlarda kahvaltı yapmaz.

= My friend does not eat breakfast in the mornings.

The only times you won’t use this case despite being a time is the incredibly common adverbials of time like bugün or yarın.

Rule 3: the complement of a subject – you are where?

For English speakers, you might think this is the same as rule 1, but it’s distinct and deserves its own rule. If you are at a location, you will use the Turkish locative case.

Dükkandasın.

= You are at the store.

Ayasofya İstanbul’da.

= The Hagia Sophia is in Istanbul.

Rule 4: a descriptive construction about age, size, shape, etc.

This use is one of the first expressions you learn in Turkish. When you talk about your age, you learn yaşında. This has an adjectival meaning – it’s obviously not a verb – and therefore can be put in the place where adjectives go. This rule also applies for things like “in the size of X” or “in the shape of.”

Bahçede bir üzümün büyüklüğünde bir sivrisinek gördüm.

= I saw a mosquito the size of a grape in the garden.

Ördeğin şeklinde bulut çocuğu güldürdü.

= The cloud in the shape of a duck / the duck-shaped cloud made the child laugh.

Rule 5: the object of particular verbs or adjectives

This is the most illogical rule. There is not reason here – you just have to memorize. A very small number of verbs take this case as an object. In your English head, it should be an object and therefore accusative, but it must be locative.

İskender kebapta karar kıldık.

= We decided on the Iskender Kebab.

Sana söylemekte sakınca görmüyorum.

= I don’t mind telling you. (literally, I don’t see harm in…)

Read the full article on my blog.

#language#learning#language learning#polyglot#turkish#turkish grammar#türkçe#linguistique#grammar#grammatical case#locative case#locative

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Learn 30 Words Per Month

This is a good goal because it's pushing you, but not beyond your limits. 30 words per months ends up as one word per day on average. That's not too unreasonable, right? We usually have 5 minutes here or there to learn how to use a word very well. If you don't have time, that's okay because you can make up for it with the flexibility of this goal.

Flexibility is okay as long as you have a way to get back on track if you fall off. I tried to learn 365 Chinese characters this year. There were months where I did nothing. However, because of the flexibility of the goal, I was able to quadruple up at the end of the year, and I still reached my goal. It wasn't as smooth as I had hoped, but I achieved it. My push helped me learn to read and write 365 Chinese characters I wouldn't have known if I didn't make this resolution.

If I had made the goal one Chinese character per day, I would have beat myself up after the first failure and totally given up. Instead, having flexibility (but firmness) baked into the resolution meant that I actually made it without punishing myself for one mistake or overly busy day.

Do 6 Hours of Listening Per Month

I am a big fan of listening as I have talked about on my YouTube channel. I personally think you should drown yourself in native speaking examples. This is an amazing goal because of all the passive benefits of listening.

As for the specifics of the goal, this is very reasonable, but still allows for you to push. On average, you would need to watch 12 minutes of content in your target language per day. That's totally reasonable. Follow a YouTube channel in your target language! If you want long-form content, that accounts for 4 movies of 90 minutes in length. This means you could watch one movie on the streaming platform you already pay for every weekend. This is absolutely doable, but the results accumulate so many good benefits.

Write 1 Sentence About My Day Per Day

A key to get better is to produce the language and get feedback. There's no better way to produce the language than calmly, carefully making a good sentence.

On top of that, with a goal like one sentence per day, you'll have so many good sentences after just one month. At the beginning of the year, you might start with "today was so busy" or "today I relaxed all day," but after some time, your sentences will grow in complexity. For me, my goal would be to write a complex, rich sentence like "Originally, I was planning to run by the grocery store to grab a couple high-caloric snacks to treat myself, but I ended up falling asleep on the couch with my dinner in my hands stained with pizza sauce on account of my crippling depression." Imagine the possibilities...

Take 1 italki Lesson Per Week

Consistency is so critical. Creating a regularly scheduled event, especially one connected to another person, will definitely keep you on track.

Even on weeks where your progress is slow, or you can't find time to do language study, a regularly scheduled event keeps you on the path to improvement.

On top of that, although reading, listening, and writing can be fit into a busy schedule rather easily, it's hard to regularly find time to speak the language with a native speaker unless it's a speaker who has a set time to speak with you.

I've had so many busy weeks where life obligations prevented me from doing my reading or listening or any other goal on this list. However, thanks to my dedication to proving to another person that I have done something in the week, I do even get minimal progress in those weeks that would have been zero progress had I not had the recurring task.

To get $10 in your student wallet after spending $20, use this link to use italki as your tool to progress.

Record Yourself Speaking Once Per Week

Something we lose sight of with language learning is perspective. It often does not feel like any progress is being made. This is because change happens slowly, and we don't notice when it happens. If we record ourselves from time to time, we can see the progress firsthand.

This goal also is really nice because you don't have to worry about embarrassing yourself in front of native speakers. You don't have to post this or show this to anyone. Just by recording yourself speaking, you've done two things: (1) you have a record of your level at that moment for future comparisons, and (2) you got your brain practicing speaking and forming sentences.

I accomplished this goal with Turkish, and it was very exciting to see progress. I love to go back to my old footage and noticing such a huge leap in my progress. It's very motivating while being minimal commitment on your part. As a goal, this is beneficial because you do regular practice in a way you might not have done; you can get out of your comfort zone.

Finish 1 Novel By December 31st

This deadline might not be pushing the envelope for a lot of people, but if you have never read a novel in your native language before, it's distant enough to not feel overwhelmed while being close enough that you don't procrastinate forever.

Novels are such a great source of vocabulary. Authors tend to use a very sophisticated mélange in their writing, so you are bound to encounter tons of new, good phrases while hopefully enjoying yourself.

Even if you do want to do more listening or speaking, reading in general is such a great passive way to improve your speaking with deep, rich expressions and elevated speech. If you drop some idiom from a novel into your daily speech, you're bound to impress natives.

Speak 1 Hour Everyday in April

"April" is just a placeholder for any month. What I am really suggesting is do something that is probably out of your comfort zone for an extreme push in a limited time. the duration is bound by a beginning and end so that you don't continue until burnout. However, the time is long enough that sustained effort will make a difference to your skills.

Assuming you don't speak the language regularly, a daily push is enough to get your brain to really take the speaking skill seriously.

Who do you speak to? That's your choice. This could be a daily tutoring lesson, recording yourself, or making an agreement to meet with a native speaker friend or language exchange partner.

The main point is that one very good goal is to set a bound time where you will push much harder than you will normally.

Finish My Grammar Textbook by March 31st

Although grammar is not everything, you will never speak fluently until you have at least a basic grasp of the main grammatical concepts of the language. Grammar is somehow divisive in the language community, but I am firmly on the side of getting it done as fast as possible so you can start focusing on vocab acquisition, accent, and native-style sentences.

Giving yourself a due date for finishing a grammar textbook is a way to cut through the procrastination and get a critical piece of learning done.

March 31st is an arbitrary date. Choose a date that makes sense with your schedule and your book. A good speed could be one chapter per week or one grammar point per day depending on how your book is organized. What you should be focusing on is setting a due date for this thing that could take years if you procrastinate enough.

You need to eat your vegetables before you can have dessert.

#language#languages#language resolutions#resolutions#new years resolutions#new years#happy new years#language goals#goals#polyglot#language learning#learning languages

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fix: for things that are broken

Although fix has a few unique meanings, especially close to the word "rig," this is the meaning people ask when they have a confusion between fix or correct.

The thing that a mechanic does is fixing. A mechanic fixes cars. A plumber fixes bathrooms. An IT specialist fixes computers.

What do all these things have in common? We fix broken things.

Do you know how to fix an iPhone screen? I dropped mine, and it cracked.

= Do you know what to do with this cracked screen?

My door cannot close, so I am going to ask my dad to fix it.

= The door cannot open or close, so my dad will make it open and close again.

Correct: for things that are wrong

There are only two states of existence: broken or not broken. Therefore, things have two states of fixing: fixed or not fixed. There is nothing between the two. For wrong and right, there is a lot of points between the two. Correct, the verb, is about making something more right.

Usually, we correct things like words or thoughts, which we do not "break." Words or thoughts can be wrong, so we can correct them.

I am waiting for my teacher to correct my essay.

= My teacher is making the words in my essay correct.

My dentist is going to correct my crooked tooth.

= My dentist will make my tooth straight. (The tooth is not broken; the tooth is not in the ideal position)

Read the rest on my blog at studywithalex.com

#english learning#esl#english#learning english#english help#langblr#studyblr#polyglot#english teacher#english teaching

1 note

·

View note

Photo

General rules

Who needs it?

Be careful of the person who needs something. In Turkish, we will almost always attach it to the verb as a personal suffix. A few of these attach to the "need" word, but not all. Because they are the owners of a verb, what is the subject in English becomes a possessor in Turkish. For example:

Sizin Türkçe daha fazla konuşmanız gerek.

= You need to speak more Turkish. (Literally, Your speaking more Turkish is necessary)

You don't need to include Sizin in the last sentence, but if you do include, it must be possessive Sizin and not Siz.

The infinitive

As you probably know, -mak/mek is the Turkish infinitive. This is the ending you will see if there are no other endings attached. However, once you add any personal ending (ex: -m, -n, -sı, -mız, -nız) or any noun case (ex: -ı, -a, -da, -dan, -la), that ending -k is dropped. However, in the absence of any ending, the Turkish verb can keep -mak/mek.

Remember that if you want an impersonal need, you can do that by not adding any personal ending and keeping that infinitive -mak/mek. In English, we would have to change the verb to passive or use a unique adjective like "necessary" to denote impersonal necessity. In Turkish, impersonal is the default, and we must add person by adding a personal suffix.

Arabayla gitmek gerek.

= It is necessary to go by car. (impersonal)

Arabayla gitmen gerek.

= YOU have to go by car. (personal to you)

When choosing your Turkish ending, try to keep in mind if you are using impersonal you or the actual 2nd person YOU. It might be identical in English, but it can be different in Turkish.

Part of speech?

Something else to keep in mind before listing all these words is what part of speech you need. Do you need a noun or a verb? For example, I need water vs. I need to drink water. This will help you narrow down what you want to use.

gerek

-ma + personal ending + gerek

This one is very flexible because gerekmek is also a verb meaning to be necessary/to be needed, to which you can attach time suffixes.

Bugün çamaşır yıkamam gerek. / Bugün çamaşır yıkamam gerekiyor.

= I need to do laundry today.

Yarın meşgul olacak mısın? Bana yardım etmen gerekecek.

= Will you be busy tomorrow? You'll need to help me.

Bu sabah çok erken uyanmam gerekti. Bu yüzden çok yorgunum.

= I had to wake up so early this morning. That's why I am so tired.

Be careful to not put the personal suffix on gerek.

şart

-ma + personal ending + şart

This word originally means "condition," so this affects how we use it. It's an adjective that means "necessary" or "needed," so just like gerek, we don't add a personal suffix onto şart but onto the verb. Because of its meaning of condition, this adjective must be with a nominal verb; you cannot use a noun. A noun is not a condition; a verb is a condition.

Her gün Türkçe öğrenmemiz şart.

= We need to learn Turkish every day.

Dışarı çıkmadan önce anahtarım bulmam şart.

= I need to find my key before I go out.

lazım

-ma + personal ending + lazım

This word has the same meanings as all the others. It is grammatically the same as şart; you should use verbs with personal suffixes and no suffix on the adjective lazım.

Bu kitabı okuman lazım.

= You should read this book.

Meyveler ve sebzeler daha fazla yemem lazım.

= I need to eat more fruits and vegetables.

-meli/malı-

verb + -meli/malı- + personal ending

This is not a word. This is an affix. More specifically, it is an infix that you put in the middle of the word with a verb root before and a personal ending after. This can only be attached to verbs.

Üşüdüğümde sıcak çay içmeliyim.

= I have to drink hot tea when I am cold.

Çok Türkçe kelimeleri hatırlamalısın.

= You have to remember a lot of Turkish words.

mecbur

-ma + -ya/ye + mecbur + personal ending

The meaning is the same on this one, but the syntax has changed a lot. Again, we need a verb with -ma, but it does not get a personal ending. It gets a dative ending -ya or -ye. This is one of the most common ending when adjectives connect to complements in Turkish. I've written about it on this blog before. Then, we have the adjective mecbur, which gets the personal ending.

Dersten önce bu kitabı okumaya mecbursun.

= You have to read this book before class.

Türkiye'ye geldiğinde Kapalıçarşı'ya seni götürmeye mecburuz.

= We have to take you to the Grand Bazaar (Kapalıçarşı) when you come to Turkey.

zorunda

-mak + zorunda + personal ending

This one is unique but closer to the last one. This cannot really be translated properly, so just focus on the syntax. You must use the infinitive form of the verb without any personal ending. Then, zorunda is another word. Then, you add the personal ending to zorunda, just as if it is a location like okuldayım (=I am at school).

Saat 12'dan önce uyuyakalmak zorundanız.

= You need to fall asleep before 12 o'clock.

Video oyunu oynamak isterse önceden ev ödevini bitirmek zorunda.

= If he wants to play video games, he has to finish his homework beforehand.

ihtiyacı var

noun + -ya/ye + ihtiyaç + personal ending + var

What if you want to say that you need to have something? In English, we can use need with any noun and it sounds natural: I need water, time, space, etc. However, as you know, Turkish is very particular with var and yok.

The person who needs (the subject in English) is the personal ending of ihtiyaç, and the object of necessity (the object in English) is before ihtiyaç with a dative case ending. As you probably know the oddities of var and yok, again the person who is in need is the possessor of ihtiyaç and therefore gets a genitive ending -ın/nın.

Köpeğimin çok yardıma ihtiyacı var.

= My dog needs a lot of help.

Bana sınıf nerede olmayı gösterecek birine ihtiyacım var.

= I need someone to show me where the classroom is.

ihtiyaç duymak

noun + -ya/ye + ihtiyaç duymak + personal ending

This one is used in the situation of needing a noun or needing to have a noun. To talk about needing a noun, you need this construction: use a noun in the dative case and then ihtiyaç duymak conjugated for person.

What is special about this one is that this is the only one you can nominalize needing something. If you want to make a comment like "It's normal to need to study" or "She talks about needing a guide dog."

Yeni arkadaşlara ihtiyaç duyuyorum.

= I need new friends.

Yardıma ihtiyaç duymayı sevmiyorum.

= I don't like needing help.

Dünyayı kurtarmak istersek daha az ihtiyaç duymayı öğrenmeliyiz.

= If we want to save the world, we need to learn to need less.

Read the full post on my blog.

#turkish#turkish grammar#türkçe#langblr#polyglot#language learning#grammar#grammar explanation#grammar help

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Japanese

Japanese opened my eyes to the Greco-Roman sphere of influence in European languages. Even Eastern Europe is in this sphere with tons of Greek and Latin words for industrial words. English is so influenced by European languages. This may seem obvious, but I didn’t realize how true this is until I saw the way Japanese imported foreign words. Japan was in a totally different cultural sphere of influence, and their language has been heavily affected by the Chinese writing system.

Japanese showed me the alternate ways to form new words using foreign roots. For example, English created the term “internet” using the Latin root inter- and the native English word net. Japanese also has a similar system of mixing Chinese character roots with Japanese words to create unique words. I never realized the extent to which English speakers coin new words using foreign words. This seems counterintuitive because English is our native language not the source of the roots, Latin and Greek, but English and Japanese share this style. Japanese helped my English understand how we use roots to coin new terms.

Latin

The languages we speak are just a snapshot. That’s what I learned from Latin. Learning classical Latin, the grammar, the word choice, the word order feel completely ancient. While things can be vaguely familiar to English speakers, I really got the impression that this is an old language.

That got me to understand my native language and its place in the timeline of humanity. The English we speak is heavily affected by modern concepts. We just accept words that did not exist 200 years ago, let alone 2,000 years ago. The language we speak is just a blink in linguistic history.

Latin made me realize how we gave old words new meanings with new concepts. For example, Latin did not have a word that is used in the same way as “message” is in modern context. Latin had a word for the old meaning of message, the underlying theme. Latin did not have a word for DM.

It made me so much more open to linguistic change. Words change so constantly. If we were linguistic purists, we just wouldn’t be able to describe the modern world around us. Linguistic purism just makes communication harder. Latin helped my English be more descriptive of the world rather than prescriptive.

German

Again, with another English cousin, there was more to discover about English. German taught me about the lost depth of English. We lost so much sophistication in the Germanic side of English that people ignore because the Latin-derived are the words of higher education or complexity. If you want to sound sophisticated, you would say “assimilate” (Latin) instead of “blend in.” (Germanic) You might say “residence” (Latin) instead of “house.” (Germanic)

Centuries of Latin as a prestigious language has made English speakers forget how much depth there is in the Germanic side of our language. I did not realize how much nuance there is with English phrasal verbs until I learned German phrasal verbs that work in a similar way.

These words have totally different meanings: let in, let out, let off, let on. However, they play with the abstract meaning of allowing in such a unique way that I haven’t seen outside of Germanic languages.

German made me aware of how interesting the Germanic side of English was, not just the Romance/Latin side. German helped my English embrace every piece of its origin.

Chinese

Building English words is tedious. That’s the feeling I got after dabbling in Chinese. We have so many unique words for concepts that can compound words in Chinese.

Why do we have a unique word for “pistol”? There are no roots to this word. To know this word, you need to memorize the full thing. You can’t understand it in pieces. In Chinese, you can understand compound words in pieces; there usually is some logic.

Chinese helped me understand that there is actually a lot of memorization in English. In Chinese, you can build a lot of words with pieces of older words you know. In English, this does not happen until you are almost a native and can build valid words with ease.

Many English speakers think that Chinese would take a long time to learn because there are thousands of characters to learn. I found the opposite. Chinese made me realize WE have thousands of unique words to memorize, not them.

Read the full blog post on my website.

#language learning#polyglot#langblr#studyblr#language#linguistics#lang#langs#blog#new blog post#new blog#what i learned

0 notes

Photo

Fragile: easily broken

The first image I have of fragile is glass. Packages containing things that easily break usually have a sticker that says “Fragile” with a picture of a wine glass. What makes this word specific is that the object is subtle or intricate; it has a lot of detail. We don’t usually use this word for something with low quality.

This word is also the only one in this pair that means emotionally unstable.

My porcelain doll is very fragile, so I wrapped it in bubble wrap and Styrofoam before putting it in my luggage.

= The doll can break easily if you push it too much or drop it.

That person is very fragile and will cry if you don’t give positive compliments.

= That person’s mental state can break easily.

Brittle: hard and dry without the strength to stay together

It may appear strong, but it does not have the strength to stay intact. The structure of this thing does not hold together well. The first image I have of “brittle” is the very American “Peanut Brittle,” a baked peanut butter dish. It’s not supposed to stay together; you can break it easily on purpose. When you use it negatively, it means the build quality is bad. Brittle things have a certain unstable texture. You can feel they are about to break even if you don’t break them.

Her teeth have become brittle from so much soda.

= The material in her teeth lost quality and can easily break now.

The archaeologist needs to handle this pot very carefully because it has become brittle after thousands of years and could break if not held correctly.

= A lot of quality of the pot was lost after many years and can easily break now.

Read the full blog post on my website at studywithalex.com

0 notes

Photo

🔮 Demystifying one (of many) of Turkish's noun case. Read this blog post about how to use the Turkish dative. http://ow.ly/Gztv50LeYRp

#turkish#türkçe#turkish langblr#langblog#langblr#polyglot#language learning#language#learning#languages#dative#noun#noun cases#grammar#turkish grammar

1 note

·

View note

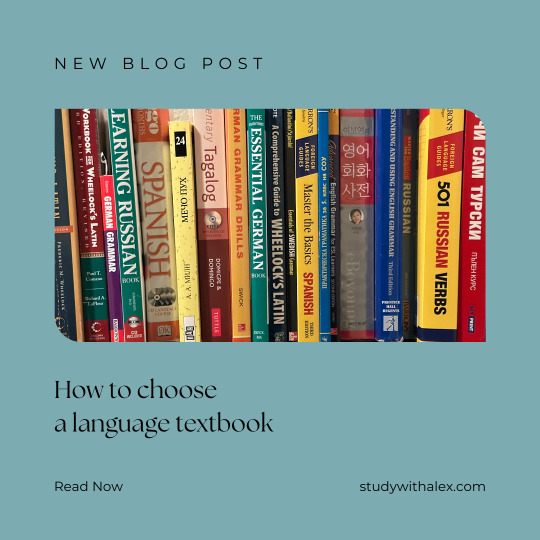

Photo

Choosing a language textbook can be hard work, so I've broken down my strategies to choose the right book.

Read here.

#language#language learning#polyglot#textbook#studyspo#langblr#languages#choosing a textbook#how to choose a textbook

0 notes

Link

One of the points of Turkish that can be confusing for a lot of learners (like me) is when to use the Turkish accusative marker. I am not a native, so I could not rely on my intuitive feeling of when to add the marker. For me, I need to memorize this set of rules for when to use the accusative marker.

What is the Turkish accusative marker?

It’s tricky to write the marker for Turkish affixes because of it’s vowel harmony. In the case of the Turkish accusative marker, there are 4 possible vowels and 1 possible consonant buffer, so there are 8 ways this marker manifests. Those are -i, -yi, -ı, -yı, -u, -yu, -ü, or -yü.

The key point of the accusative marker is that it is used for the object of transitive verbs. In English, we don’t use affixes to mark objects; we use word order. If you have learned a language like Latin, Russian, or Japanese, you have seen languages that add a special ending to nouns to show how they connect to the verb.

The problem is that not every Turkish direct object receives the accusative marker.

Bir kitap okuyorum.

= I am reading a book.

Here, kitap does not need the marker because it is used in a indefinite sense. Because “bir kitap” is translated as “a book,” it does not need a marker to become kitabı.

What exactly are the rules for when you SHOULD use the accusative marker?

Rule 1: definite

If you would translate the object into English with “the” or “this,” use an accusative marker.

Evde kitabı unttum.

= I forgot the book at home.

Bu ekmeği yiyeceğim.

= I will eat this bread.

Rule 2: has a possessive suffix

If the object is possessed, meaning you would translate it into English with “my,” “your,” “his/her/its,” etc., use an accusative marker.

Bugün parkta arkadaşlarını gördüm.

= I saw your friends at the park today.

Derslerimizi çok seviyorum.

= I really love our lessons.

This does not include the situation where a noun modifies a noun, requiring the 3rd person.

İyi bir Türk kitabı okuyorum ancak maalesef evden ayrıldım.

= I am reading a good Turkish book, but unfortunately I left it at home.

We mark kitap with the possessive –ı only because the noun Türk is modifying it. It is not possessed by Türk, and we know that because it would be Türk’ün (=a Turkish person’s). Even though it looks like it, this sentence does not have accusative marker. Otherwise, if it was “I am reading the good Turkish book,” it would be iyi Türk kitabını okuyorum. This combines the noun compound Türk kitabı with an accusative marker –ı, and affix clusters for nouns are separated with -n-.

Rule 3: a general statement about a group, marked by -ler/-lar

If you are saying a general statement about some plural group, you will use an accusative marker (and also probably the aorist verb tense).

Kedileri severim.

= I love cats.

Faydalı kelimeleri öğrenmez.

= He doesn’t learn useful words.

Rule 4: uses hangi (= which)

If your object uses “which,” you need an accusative marker.

En çok hangi şarabı seviyorsun?

= Which wine do you like the most?

Kahvene hangi sütü koyuyorsun?

= Which milk do you put in your coffee?

Rule 5: the object isn’t directly before the verb

This rule overrides all the other rules. Even if the objects does not fit in rules 1-4, you should use an accusative marker if the object is far from the verb, interrupted by some other phrase or expression.

Üç dili Almanya’dan gelen arkadaşımla konuşabilirim.

= I can speak three languages with my friend who came from Germany.

Yeterince para istiyorsak iki sandalyeyi komşularımıza satmamız lazım.

= If we want enough money, we need to sell two chairs to our neighbors.

Because iki sandalye was not right before the verb satmamız, it got the accusative marker -yi. If we rearranged the sentence, there would be no marker because iki sandalye is not definite, not possessive, not a general group marked with -ler, and not a question with hangi.

Yeterince para istiyorsak komşularımıza iki sandalye satmamız lazım.

= If we want enough money, we need to sell two chairs to our neighbors.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

One word that has caused me a lot of confusion in my German journey was “house” or “home.” Usually, English words have similar counterparts in German. However, I always had trouble knowing how to say home in German.

Zuhause? zu Hause? das Zuhause? daheim? das Heimat? das Haus? nach Hause? die Häuser?

My confusion partly stems from the strange treatment of this word in English, but German also has some unique ways it handles this word. There are many situations that are very different that all use the word “home” in English, so we need to unravel those in order to clearly see what German is doing with that general concept.

“Home” as a location

In English, there is a specific group of words that (almost) never take prepositions. They derive from nouns, but with time they have become adverbs that sound wrong with “to” or “at.” This group includes things like upstairs or downtown. The important one for today is “home.” If someone asks you where you are in English, you can reply “I’m home.” It does not mean you are a house; it means you are located at your house.

If you want to say “I am home,” in German, you will use “zuhause.”

Wenn du krank wirst, solltest du zuhause bleiben.

= If you get sick, you should stay (at) home.

Ich verlasse mein Auto zuhause, und du wirst mich zur Arbeit fahren. Klingt das gut?

= I will leave my car at home, and you will drive me to work. Does that sound good?

Then what is “daheim”?

“Daheim” is used in the exact same way as “zuhause,” an adverbial location for home. The difference is that it is more typical for southern Germany. It’s not my job to say whether or not to use this word, but this word is slowly disappearing in standard Hochdeutsch. This article shows an unscientific survey where most respondents say they prefer “zuhause” over “daheim,” and this article attributes “daheim” to southern-style German.

zuhause oder zu Hause?

These two forms are used in identical ways; they are both used to talk about location, probably with bleiben or sein.

Working from home

This expression work “from home” that has become very common in the recent years uses von + “zuhause” + aus. This makes sense on a grammatical level because “from home” uses “from,” meaning a separate location, and “zuhause” a location.

Das Unternehmen lässt die Angestellter, zu entscheiden, ob sie von zuhause aus arbeiten wollen.

= The company lets employees decide whether they want to work from home.

Home as a noun

If you add any article or adjective to “home,” you are probably dealing with a noun. In this German situation, you will use the noun das Zuhause. It was confusing for me when I first heard it because that “zu” was originally a preposition that attached itself to a noun, creating a Frankenstein-noun, which German loves. The meaning is the same as English “home,” meaning the residence where you feel comfortable.

In unserem Zuhause ist es eine Regel, dass man seine Schuhe auszieht, wenn man betritt.

= In our home it is a rule that you take off your shoes when you enter.

Ich vermisse mein Zuhause.

= I miss my home.

This video and article also explain the difference between Zuhause, zu Hause, and zuhause in full German. This website also has a lot of good German differences, which can be helpful for German learners if you already are advanced enough to understand full German explanations.

Home as a direction

As I mentioned, “home” is one of the words that does not need “to” in English. We “go home,” and we “come home” without “to.” In German, this is probably going to be “nach Hause.” This is paired with the most common movement verbs “gehen,” “kommen,” or “fahren.”

Ich höre einen Podcast an, wenn ich nach Hause fahren.

= I listen to a podcast when I drive home.

Die Kinder sind um 14 Uhr nach Hause gekommen.

= The kids got home at 2pm.

Any preposition that is not “to”

Although “nach Hause” is the basic preposition you will use most of the time with the most common movement verbs gehen and kommen, any other preposition can be combined with “das Haus” if you need to specifically mention direction. This will usually be combined with nouns or special verbs that are picky about their prepositions.

Direkte Lieferung ins Haus ist nicht verfügbar in meinem Land.

= Direct home delivery (direct delivery into the home) is not available in my country.

Home as a territory or country

The word das Heimat in German translates more precisely to “homeland” in English, but we could also use “home” in English, which is why I include it here.

Wegen des Krieges müssen die Menschen ihre Heimat verlassen.

= Because of the war, the people must leave their home(land).

Das Heimat, das du dich erinnerst, hat nach 50 Jahre verändert.

= The home(land) you remember changed after 50 years.

House as a building

Like in English, das Haus (plural die Häuser) is the building we live in. While das Zuhause is more emotional and warm and fuzzy, like your home, das Haus is the most basic word representing the building.

Ich hätte lieber ein Haus mit vier Schlafzimmern.

= I would prefer a house with four bedrooms.

Ich brauche Hilfe beim Streichen meines Hauses.

= I need help painting my house.

Read more on my website

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

The question that can discourage or encourage a language learner to an absurd degree is whether we lose the ability to learn languages as we age. Does age matter when it comes to language learning?

It’s pretty common knowledge, at least among language learners, that babies have a better-than-average ability at learning and distinguishing languages. We all know that an adoptee raised in another country does not have the accent or language of their birth country. What happens as that baby ages into a child, teen, and adult is unclear, and people put a lot of concern on this ability.

My experience as a child

In my limited life experience, my early years were critical to set me up for my adult learning process. As opposed to other children of immigrants who just picked up their native language at home,

I didn’t speak my heritage languages as a toddler. In my elementary school years, my mom tutored me in those languages directly. I was lucky enough to get lessons in a very simplified form. Then, as a teen, when I learned French in high school, I was able to connect those lessons with the formal French education that millions get.

Personally, I am really thankful I learned a language formally at that age of 8 (give or take). I think 5 years earlier or 5 years later would have had a totally different result on my language skills today. It was because I was 8-ish that I was able to come to personal conclusions about grammatical logic. I had a bigger grammar sample size than my monolingual classmates, so I could find my own references. It allowed me to progress in French and others later.

My experience as an adult

My language learning journey as an adult was heavily influenced by my childhood years. Unfortunately, we cannot separate those early years with the adult years, so the experience can seem blended.

Language learning as an adult has been relatively easy. In fact, there is one skill that has only gotten better with age: abstractions.

Many tend to overestimate the skills of a child to learn English. Sure, they could remember words more easily or speak with a lighter accent. However, children struggle to make language abstract.

In my italki classes, I need to rethink my strategy depending on the age of my student. Most of my students are adults, but when I get a 10-year-old student, it is a very different experience. Although they have fantastic pronunciation and spend less time translating in their head, I cannot explain very abstract concepts to them.

This is an advantage that comes with age. Children’s learning materials are usually colorful and use a lot of real concepts like animals, colors, or daily tasks. While this is important, this is only half of language learning. We still need to learn about receiving actions, time order, or honorifics. Those things are hard to make for children. Adults, however, can easily receive these explanations. They might not be masters from the first explanation, but they at least understand my explanations about time order.

Again, going back to my italki ESL lessons, I have had so much more success explaining passive voice to adults than to children.

So there is a linguistic advantage with age.

What science has to say

A linguistic study tried to find the elusive “critical period” of language acquisition that everyone knows exists but doesn’t know when it exists. The theory for this special period of acquisition was the toddler years, but the data suggests the critical period ends around 17 years old and steadily declines.

My experiences match up with the findings. I had been exposed to so many different languages since childhood, and I was able to think in those languages with little rote memorization. As I get older, I notice I need to do more memorization, and there is still some 5% of words that I cannot remember and need to review every day, forgetting it as soon as I put the card away.

Are older learners out of luck?

No. Work hard. Someone’s age should not be a reason to give up or a reason to despair.

Language learning can really happen at any age. The only thing that my and other language learners’ experiences show is that older learners might have a harder time. This does not mean it is impossible. Theoretically, even if someone is 150 years old, they can still learn a language.

What this is really about is advantages.

Older learners are at a disadvantage, and we ought to be acknowledging this problem so that we can address is correctly.

Recognize what is tough for you while still making good goals. You cannot memorize words at the rate a child does, but you can still memorize words. And you have to, too!

Don’t let your age be an excuse

The myths surrounding language learning and age can lead people to make some bad decisions with their language learning process.

An old person should not give up easily just because (they think) they are destined to fail if they never learned the language as a child.

A teenager or young adult should not think hard work is not the most important factor in language learning and expect that the language will be absorbed into the young mind through osmosis.

Language learning, at its core, is the same for everyone. No one can avoid the time spent learning words, understanding new concepts, or accumulating hundreds of hours of input. This is the same for learners of every age.

If you want to read more language learning content, you can find some on my website.

I also have a YouTube channel where I make videos about language learning.

Don’t give up, don’t get complacent, and don’t stop learning languages.

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Language Alignment Chart

Ranking a variety of languages, some I know, some I have experience with, some I barely know anything about, in terms of lawfulness and chaos and how quickly you can start making sentences

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

German Resources

German grammar drills

ISBN: 978-1260116250

https://amzn.to/37EkE5f

The everything essential german book

ISBN: 978-1440567575

https://amzn.to/3toUBaN

Barron’s German Grammar

ISBN: 978-0812042962

https://amzn.to/3wmLBEX

SparkNotes German Grammar

ISBN: 978-1411470408

https://amzn.to/37KQjCe

DW - Deutsche Welle - Germany’s public broadcaster

https://www.dw.com/de/

https://apps.apple.com/us/app/dw-breaking-world-news/id498833085

The app will match the language settings of the phone, so you will need to change it to German manually

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.idmedia.android.newsportal&hl=en_US&gl=US

DW Learners - German resources for learners

https://www.dw.com/de/deutsch-lernen/s-2055

https://apps.apple.com/us/app/dw-learn-german/id1224076534

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.dw.learngerman&hl=en_US&gl=US

ORF - Österreichischer Rundfunk - Austria’s public broadcaster

https://der.orf.at/

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=at.orf.news&hl=en_US&gl=US - the website

https://apps.apple.com/us/app/orf-tvthek-video-on-demand/id452214869?l=de - TV component only

Deutsche Welle - YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCMIgOXM2JEQ2Pv2d0_PVfcg

Kurzgesagt - YouTube - edutainment YouTube channel with English versions of every video on another channel

https://www.youtube.com/c/KurzgesagtDE

MrWissen2go - YouTube - German current events spoken by a man with clear pronunciation

https://www.youtube.com/c/MrWissen2go

Linguee - Dictionary - The most accurate one I’ve experienced with lots of example sentence so you can parse which similar word is the right one for you

https://www.linguee.com/

https://apps.apple.com/us/app/dictionary-linguee/id338225335

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.linguee.linguee&hl=en_US&gl=US

Reverso - Conjugation

https://conjugator.reverso.net/conjugation-german.html

Wiktionary - Noun and adjective declension

https://en.wiktionary.org/

#german#deutsch#learning german#polyglot#language#langblr#studyblr#deutsch lernen#deutsch langblr#resources#free resources

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Characters With Other Meanings That Surprised Me

Over my years of studying Chinese, I’ve encountered many familiar characters in unfamiliar situations. Basically, when I originally learned a character, I only learned one or some of its possible meanings. Then later down the line, I encountered the same character but with a meaning that I hadn’t learned. Confusion ensued. Then I pulled up Pleco or MDBG, and all became clear!

Let’s go down memory lane and look at some of the characters that have perplexed me over the years.

同款 tóngkuǎn - similar (model) / merchandise similar to that used by a celebrity etc

Recently I’ve seen a lot of ads with the word 同款. I was quite confused because I thought 款 had to do with money, like in 贷款 or 捐款. After looking up 款, everything made sense—the ads I saw were advertising a service where you can buy clothing that your favorite celebs wear!

款 kuǎn - section / paragraph / funds / classifier for versions or models (of a product)

疼惜 téngxī - to cherish / to dote on

疼爱 téngài - to love dearly

Before encountering these words, I was only familiar with 疼 from words like 头疼 and 疼痛, which have to do with pain. So you can imagine my confusion when I saw “cherish” as the definition for 疼惜! I find it interesting how this character has both a very positive and a very negative meaning.

疼 téng - (it) hurts / sore / to love dearly

告别 gàobié - to leave / to bid farewell to / to say good-bye to

离别 líbié - to leave (on a long journey) / to part from sb

I knew a lot of words with 别, but none with the meaning of leave/depart…even though that is the first definition listed in MDBG! Even to this day, when I see the expression 别来无恙, it takes me a sec to remember what 别 means in there.

别 bié - to leave / to depart / to separate / to distinguish / to classify / other / another / don’t …! / to pin / to stick (sth) in / (noun suffix) category

发毛 fāmáo - to be scared / to be panicked

I heard this use of 毛 while watching Chinese-language TV. I instantly looked up 毛 in Pleco because the meanings of 毛 I knew made no sense in the contexts of the scene. I’ve been able to remember this new (to me) meaning of 毛 thanks to the chengyu 毛骨悚然.

毛 máo - hair / feather / down / wool / mildew / mold / coarse or semifinished / young / raw / careless / unthinking / nervous / scared / (of currency) to devalue or depreciate / classifier for Chinese fractional monetary unit

说道 shuōdào - to state / to say (the quoted words)

问道 wèndào - to ask the way / to ask

I was so bewildered when I first saw 道 used like this—even though I knew many, many words with 道 that were diverse in meaning. Now I see this kind of 道 a lot when I’m reading, so I’m confident that you will encounter it sooner or later.

道 dào - road / path / principle / truth / morality / reason / skill / method / Dao (of Daoism) / to say / to speak / to talk / classifier for long thin things (rivers, cracks etc), barriers (walls, doors etc), questions (in an exam etc), commands, courses in a meal, steps in a process / (old) circuit (administrative division)

Keep reading

203 notes

·

View notes

Link

I + feel + adjective

Just like look, sound, smell, and taste, feel is also a way to give in an opinion on something’s characteristics.

In English, we say things like “I feel happy,” which is a comment on the sensation on the situation. In German, this will be expressed with sich(akk) fühlen.

I feel happy.

= Ich fühle mich glücklich.

My dog feels safe in this house.

= Mein Hund fühlt sich sicher in diesem Haus.

Notice that because the adjective is a predicate, it does not decline to match the subject.

feel + noun

When you talk about a thing you are sensing, you can use fühlen (not reflexive) or spüren. We are talking about the general perception of a thing, not the physical sensation of touch.

Ich setze mich draußen gerne weil ich die Wärme der Sonne fühlen kann.

= Ich setze mich draußen gerne weil ich die Wärme der Sonne spüren kann.

= I like to sit outside because I can feel the warmth of the sun.

These two words are pretty interchangeable. The important thing to remember is that a noun follows them, not an adjective.

something + feels + adjective

If we are talking about the physical texture of something else or your opinion of the physical texture of something else, you will use sich(akk) anfühlen.

Gerade jetzt habe ich mich rasiert, und meine Haut fühlt sich so weich an.

= I just shaved, and my skin feels so soft.

The key point is that the speaker is not the subject. You are commenting on the characteristics of the subject.

Dieses Bett fühlt sich an wie jemand darin geschlaft hat.

= This bed feels like someone slept in it.

Summary

sich(akk) fühlen: I feel + adjective

fühlen: feel + noun

spüren: feel + noun

sich(akk) anfühlen: something feels + adjective

You can read the rest and other articles on my website.

#polyglot#language learning#grammar#grammatik#deutsche grammatik#german grammar#feel#feeling#deutsch#german#langblr#studyblr

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

How to fit language learning into a busy schedule

A major barrier to many people learning languages is the time dedication. They might want to learn multiple languages, but they don’t have time on top of a full time job and home obligations. For most people, there is not enough time in a day to fit a consistent language learning in a busy schedule.

As much as I would love to live in a paradise where I have no responsibilities, and my mortal bodily functions don’t pull me away from language learning, that does not exist. Here in the real world, we have to balance our lives.

On top of that, language learning is not an actual job. Sure, your job might want you to learn a language, but they probably aren’t paying you for it. This reduces language to just a hobby. Languages have to compete with entertainment like Netflix for your free time. Understandably, languages lose that competition for a lot of people.

What if they don’t have to be a nuisance that take away from other things?

5 Senses

We have five senses, and we really should be using them. Most likely, a lot of your daily tasks do not require hands, eyes, and ears at the same time.

My motto is “if I have a free appendage, I could be learning a language.” Do you really need full attention when you brush your teeth? What about cooking? How about stuck in traffic?

If there is an open moment like those, you can play some language content. This could be foreign language podcasts, foreign music, or a foreign YouTube video.

This week, I was playing a game in German while listening to a German podcast. Then, as I was logging my time into my language spreadsheet, I noticed I did something strange. I input 20 minutes into the listening section and 20 minutes into the gaming section. 20 minutes in real world gave me 40 minutes of language learning.

One day really is more than 24 hours.

Of course, this only works for passive input. You can’t do this with grammar, which requires your full attention. Most of language learning isn’t grammar, though. A lot of language learning is the accumulation of hours and hours of content refactoring how your brain can communicate. That can be designated for the simple tasks of the day.

“Okay, I can listen to some foreign songs on my commute to work. What about grammar? I can’t take my eyes off the road.” I told you at the start that you can language learning in a busy schedule, didn’t I?

Chunking

There are parts of language learning that require full attention, both hands, both eyes, etc. However, those moments don’t need hours of dedication; they just need a few seconds at a time.

Languages are made up of hundreds of small grammar rules. Rarely do languages need 20 minutes to explain a concept.

Let’s use English for an example. I can tell you that “your” is for possession, and “you’re” is for situations where you want to say “you are.” I just gave you a bite-sized piece of grammar. That was one piece of information. You absolutely could have learned that on the toilet or when you are waiting in line at the store.

If you look at how a lot of language textbooks are written, they write very simply. They give one grammar point, a few examples that are totally independent of the others, and then another grammar point. History textbooks take an hour of uninterrupted reading. Grammar textbooks only need a few seconds of your times for many iterations.

This means you can fit the heavy lifting of language learning into those wasted moments of your day: waiting in line at the store, sitting on the toilet, waiting for your coffee to brew. All of those moments can include one grammar point or a couple of (digital) vocab flash cards.

In fact, I think this strategy can be more helpful for the dedicated learners because they have more time to think about grammar. Instead of setting aside one hour for nothing but grammar, which will make your head spin, you can drip-feed yourself language content so that you brain doesn’t get tired of this new information.

You can read the rest on my website, studywithalex.com

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Be careful of this harasser

“Hunting Fake Polyglots”

Recently renamed to “Exposing Fake Polyglot YouTubers”

This channel spends hours:

Nitpicking videos of people practicing languages to belittle their language abilities

Sending direct harassment

Calling all language learners scammers

Using violent imagery about language learners

All of his channel is meant to mock language learners and humiliate them.

He calls any person who talks about language online a scammer if they edit their videos or break eye contact with the camera. He says every language learner lies about their birthplace to prove they are sociopaths.

youtube

Be careful of this person. He changes his username often to evade a community guidelines strike.

He also uses Instagram with sock accounts whose names he also changes often in order to post hateful comments on language learning posts.

I don’t have proof that this is his Instagram account, but this account sent my Instagram several comments just like this with similar wording to the aforementioned channel.

A deep dive into this harasser:

youtube

#polyglot#language learning#language learner#language#langblr#studyblr#harassment#harass#hate#hate speech#violence#tw

2 notes

·

View notes