Text

James Baldwin: «history is literally present in all that we do»

History is not something that exist, something that one can consult, but it’s the question we keep inside ourselves; it’s not something that defines us a priori, but a description we choose for ourselves.

History intende as past is a crystallising of our being to find something that looks like us, to not to deal with the vertigo of the future, to not to fight with our own evilness, to deal with.

James Baldwin wrote that «[…] history is literally present in all that we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations. And it is with great pain and terror that one begins to realize this»[1]. History is, thus, a further tools we can use to give meaning to our existence, a point of view among other points of views that run into and clash between each other. History’s a tale we can still change, and it’s still possible to free the world from that heavy curtain which is racism, but only if we’re brave enough to face our past, not to make it the descriptor of our present, but only a little part, only if we’re brave enough to deal with our evilness, and abandon the fetish of a past that oppressed and to accept that past looks like us very little, that history is our present, something we preserve.

This must be learned by Black people, so that they can tell a different story, to convince themselves their last is not their doom, to learn how to use their history as a tool. «Something more radical had to be done; a different history had to be told. “All that can save you now is your confrontation with your own history […] which is not your past, but your present,” Baldwin said. “Your history has led you to this moment, and you can only begin to change yourself by looking at what you are doing in the name of your history.”»[2]

This must be learned by white people in order to free themselves from their guilt, because «[t]he fact that [the white people] have not yet been able to do this--to face their history to change their lives--hideously menaces this country. Indeed, it menaces the entire world»[3]. The white man’s burden is not, as Kipling wrote, to bring civilisation, i.e. to impose an Eurocentric vision of the world, to distant communities, but it’s history, as Baldwin wrote; or better, it’s the burden to have sewn the heavy curtain of race around themselves to divide “we” from “they”, as if these differences existed and they weren’t a way to keep their power, to never put themselves in discussion[?]. And how to face own history if this means to doubt own position, an identity built to the detriment of other?

To understand what history means is to change world.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Reference

1. BALDWIN, James, “The White Man’s Guilt”, in Collected Essay, New York, The Library of America, 1998, p. 723

2. GLAUDE Jr., Eddie S., “The history that James Baldwin wanted America to see”, in The New Yorker, web, 19.06.2020 (https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-history-that-james-baldwin-wanted-america-to-see)

3. BALDWIN, James, “The White Man’s Guilt”, p. 722

Source

1. ALS, Hilton, “The Enemy Within. The making and unmaking of James Baldwin”, in The New Yorker, web, 9.02.1998 (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1998/02/16/the-enemy-within-hilton-als)

2. BALDWIN, James, “The White Man’s Guilt”, in Collected Essay, New York, The Library of America, 1998

3. BALDWIN, James, “Letter from a region in my mind”, in The New Yorker, web, 9.11.1962 (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1962/11/17/letter-from-a-region-in-my-mind)

4. GLAUDE Jr., Eddie S., “The history that James Baldwin wanted America to see”, in The New Yorker, web, 19.06.2020 (https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-history-that-james-baldwin-wanted-america-to-see)

#James Baldwin#black history month#black lives matter#writing#blogging#history#identity#memory#culture#article#politics#literature

1 note

·

View note

Text

Toni Morrison: «Memory meant recollecting the told story», II part

Magic as cultural device for the construction of collective memory

The recollection of West African tradition and the addition of elements inside the narration are another way to build the collective memory, where the African culture becomes a common ground in which sharing meanings, and also an instrument of resistance against dehumanisation. As the slave-owning people tried to deny the humanity of Black people, the latter communicated, resisted and strengthened each others maintaining the practice of their culture. This recovery, as orality in Toni Morrison’s works, is translated also as the addition of magical or supernatural elements of African cultures; «Morrison seeks to address this insecurity by creating an African American cultural memory with her readership through mutual acts of the imagination. In order to achieve this her writing encourages the imaginative participation of the reader in the text through oral storytelling techniques and, despite Morrison's disclaimer, through magic realist devices»[8]. The magic element is connected to the oral tradition to which Morrison referred, because both orality and the supernatural element represent modalities of transmission of her tradition; indeed, «Morrison's two most notable novels, Beloved (1987) and Song of Solomon (1977), both contain magic realist elements which can be traced to African American myth and both novels focus on the importance of the role of memory in oral tradition to perpetuate African American culture»[9].

In particular, ghost stories and the image of the revenant, both present in oral African tradition and recovered by the Afroamerican one, are more relevant in Morrison’s works and these elements are the ones that collect that sense of connection with the past, the relations between being here and now and memory, a process that creates the collective identity from that history shared by the individuals, by the personal experiences to the common destiny of a collectivity. This happens in her most notable novel, Beloved, where the young girl murdered by her mother comes back as a ghost, as a revenant, a spectre from the past and recollection of memory, of traumas, the personal and shared ones. The tragedy of death, of negation of the self, the horror of slavery and of dehumanisation. «The use of a revenant for this story set during the specific historical period of the end of slavery and the reconstruction era is especially poignant. Eugene Genovese notes that during slavery ghost stories were prevalent on plantations and was one way in which elements of African tradition were retained»[10]. The magic element, and in particular ghost stories, has got a double role in the recovery of cultural issues, i.e. the reversal of coercive elements and the reappropriation of cultural images that were confiscated by owning-slave individuals to culturally oppress slaves. «As Fry explains, one means of control over slaves was for the master to create and spread a ghost story set in an area that was difficult to patrol […]. Through this method the master attempted to increase his control over the slaves by appropriating the transmutable force of a ghostly presence»[11]. Also in Toni Morrison, memory becomes a way to resiste culturally and to affirms the personal identity, as well as liberation from the hegemony perpetrated by white people and from oppression, using the alternative cultural reference and recollect those which were transformed into an instrument of control. Indeed, «the use of a ghost in Beloved – whose ultimate effect in the novel is to draw a community together for self-healing and protection - can be seen as a creative act of resistance to such attempts at control in slave history whilst appropriating the very power associated with ghosts for subversive purposes»[12]. But not only this. The use of ghosts in Beloved has also a negative quality, and so not just this of recovery. The ghost can be defined also as a threatening and negative figure, able to bring chaos, fear and division in the community; it’s the image of a dead that is back, the trauma that comes back to haunt. «Morrison establishes Beloved as a ghost in specifically African American terms and in doing so she brings the symbolism associated with the Ku Klux Klan into a familiar realm where it may be controlled»[13]. The reference to Ku Klux Klan means also the return of a violent past, of oppression, of discrimination. The history of slavery coming back to haunt, to scare and the racism of a certain political wing, racist declarations and action return. And recollect certain images, make them inoffensive, is a way to resist, an example of social response, whose purpose is to heal the trauma of an entire community, which is still dealing with the ghosts of the past. In Beloved, the ghost is «the past, and that part of the past which she represents is the internalised selfhatred by African Americans due to persistent racism against them. Sethe's coming to terms with her past is in part a coming to terms with her own self-hatred which she insists that Denver avoids»[14].

From the piece to the wholeness: memory as a creative process

«Memory, then, no matter how small the piece remembered, demands my respect, my attention, and my trust. I depend heavily on the rude of memory […] because it ignites me some process of invention»[15].

Toni Morrison, Memory, Creation and Writing

We’re almost at the conclusion, with another aspect of memory in Toni Morrison’s work, as it was unveiled by her in the magnificent essay Memory, Creation and Writing, about the memory as a creative process. It’s the memory itself, a fragment of reality showing up in the consciousness, a drop of reality, a revived moment, the perception of something that had been which trigger the creative language of Toni Morrison, that creates narrations, stories, characters she tells about in her books. A fragment to create the wholeness, one memory, or better, what this memory brings in mind emotionally. «The pieces (and only the pieces) are what begin the creative process. And the process by which the recollections of these pieces coalesce into a part (and knowing the difference between a piece and a part) is creation»[16]. This makes clear how much permeated is memory in her works, because this one is the origin of creation, but also what gives meaning to the story, what confers a common sense, signifies and orders the world. It means give a sense. A sense to life, to the past, to the horror, to trauma. It means order the present. And giving a meaning is to connect, as Toni Morrison connects pieces, memories, to create the wholeness, a picture that has a sign, that creates a pairing of figured to make it a different, unique one, transformed in it wholeness. It’s the narration that «is one of the ways in which knowledge is organized […] the most important way to transmit and receive knowledge»[17]. Memory is transmission, is the recovery of identities, is to call ourselves, recognising the Other, what has never been, because last is a lesson, is the path that lead us here and it’s the events that shaped us, and only remembering we can give a meaning to what we will remember. Thus, memory means to tell, is an epiphanic process, of realisation, that provokes the creation of a image. And it’s from this that Toni Morrison creates, because «memory meant recollecting the told story»[18].

First part here

Viviana Rizzo @livethinking

Reference

1. DAVIS, Christina, “Interview with Toni Morrison”, in Présence Africaine, 1er trimestre 1988, no. 145, p. 143

2. MORRISON, Toni, “The Site of Memory”, in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, Boston, Ed. William Zinsser, 1995 (2nd edition), p. 92

3. DAVIS, Christina, “Interview with Toni Morrison”, p. 143

4. NISHIKAWA, Kinohi, “Morrison’s Things: Between History and Memory”, in Arcade. Literature, the Humanities & the World, web, arcade.stanford.edu, 2021 (https://arcade.stanford.edu/content/morrison’s-things-between-history-and-memory)

5. LANIER, Adrienne & TALLY, Justine “Toni Morrison, Memory and Meaning”, in miscelánea: a journal of English and American studies, 52 (2015), p. 155

6. ONG, J. Walter, Orality and Literacy. The Technologizing of the Word, New York, Routledge, 2002, pp. 133-134

7. BOWERS, Maggie A., “Acknowledging ambivalence: The creation of communal memory in the writing of Toni Morrison”, in Wasafiri 13:27(1998), p. 21

8. Ivi, p. 19

9. Ibidem

10. Ivi, p. 21

11. Ivi, p. 22

12. Ibidem

13. Ibidem

14. Ibidem

15. MORRISON, Toni, “Memory, Creation, and Writing”, in Thoughts, vol. 59, no. 235 (December 1984), p. 386

16. Ibidem

17. Ivi, p. 388

18. Ivi, p. 389

Sources

1. BOWERS, Maggie Ann, “Acknowledging ambivalence: The creation of communal memory in the writing of Toni Morrison”, in Wasafiri, 13:17 (1998), pp. 19-23

2. DAVIS, Christina, “Interview with Toni Morrison”, in Présence Africaine, n. 145 (1st trimester 1988), pp. 141-150

3. MORRISON, Toni

“Memory, Creation and Writing”, in Thought, 59/235 (December 1984), pp. 385-390

“The Site of Memory”, in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, Boston, ed. William Zinsser, 1995 (2ª edition), pp. 83-102

4. NISHIKAWA, Kinohi, “Morrison’s Things: Between History and Memory”, in Arcade. Literature, the Humanities & the World, arcade.stanford.edu, web, 2021 (https://arcade.stanford.edu/content/morrison’s-things-between-history-and-memory)

5. ONG, J. Walter, Orality and Literacy. The Technologizing of the Word, New York, Routledge, 2002, pp. 133-134

6. SEWARD Adrienne Lanier & TALLY Justine, “Toni Morrison, Memory and Meaning”, in miscelánea: a journal of English and American studies, 52 (2015), pp. 155-158

#Toni morrison#memory#beloved#song of Solomon#orality#identity#ghost stories#revenant#magic realism#magic#magic elements#African cultura#Afroamerican culture#Black culture#Black art#black history month#black lives matter

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toni Morrison: «Memory meant recollecting the told story», I part

Memory is an extraordinary instrument, capable of connecting individualities, the personal characters, the subjective experience of things, to link what has been, to what has faded to what has still no existence, is a potential act, what could be. Memory shapes identities, people’s characters, the perceptions of the Other and of things. Memory is an act of personal resistance, that is the creation of cultural value that are not collective or shareable, is a processo of building the person and society. And it’s in this sense that Toni Morrison calls memory to herself, makes it a narrative instrument, a collection of fragments which are not linguistically pronounceable, that she makes them part of a complex narration through building the artistic culture socially shared among the Afroamerican people, through building that cultura which was denied by the cultural hegemony of white people, by the tragedy, of the inhumanity of the slavery, of dehumanisation of Black people. In Toni Morrison’s works, the remembering becomes an act of resistance and social construction, of recollection of the African tradition of Black community to build its history and its human and emotive character of individual to whom was even denied the existence.

The construction of collective (and cultural) memory of Afroamerican community

Memory and construction of a historical and cultural identity of Afroamerican community has always been central in the work of the greatest Black American authors, since che beginning, when they, through their memoirs, tried to regain that human sense as recognised in the American Constitution and denied to the them, and show a certain rationality, a quality that the Western tradition considered as a prerequisite of human beings that white people took advantage of to promote an unreal biological superiority. A rationality they proved, in literary practices, as the absence of emotional frames to the autobiographical constructions. Those role of memory is the one that Toni Morrison recognises and uses to build her story, as she told in an interview:

«You have to stake it out and identify those who have preceded you – resummoning them acknowledging them is just one step in that process of reclamation – so that they are always there as the confirmation and the affirmation of the life that I personally have not lived but is the life of that organism to which I belong which is black in this country»[1].

It’s the same Morrison who tracks the artisti chronology of Afroamerican literature in an essay, The Site of Memory, showing how autobiographies and memoirs had the role not to my to tell a personal story or impressions on events and experiences that build the author’s character, but also the one to show authors’s own rationality and humanity, so much that these productions (and also for not making white people feel guilty and making them feel empathic, than accuse them) lack of the emotional side and the most heinous events the authors faced, taking their Ego and their thoughts off from these memoirs, which, thus, became a report on slavery and its brutality, in order to trigger a positive reaction from the Caucasian public.

Memory and personal experience are a central characteristics Afroamerican people’s literary works, and stil, today these practices are fundamental and come back into those books which are less connected to authors’ biography. But we should focus more on another side now, if we want to fathom the role of construction of collective memory in Toni Morrison’s books. The author focuses on, in the first works of Black authors, not on the personal experience, the brutalities these people faced and from which they build the imaginary and the narration of this ethic group, but on the absence of the emotional sphere in these works, what are most important side of these one for Morrison, what she considered as the starting point from which starts her research and, thus, to build her own poetics. Morrison doesn’t have the access to the interior life of these authors, who chose to eliminate it from their writings, and thus, she tried to build it, to recover it from the fragments, from the process of imagination; «[t]hese ‘memories within’ are the subsoil of [her] work. But memories and recollections won’t give [her] total access to the unwritten interior life of these people. Only the act of the imagination can help [her]»[2]. A process of recollecting from the buried memories, from the what’s not told, from that absence which construct the identity, the real story; no the experience, but the interior loves of these individual that shapes the history, «[…] and in so doing was able to imagine and to recreate cultural linkages that were identified for me by Africans who had more familiar an overt recognition»[3]. A process that Toni Morrison called “rememory”, i.e. the collection of traces, fragments, proofs to build the collective memory and to access to this one, because these fragments (such as pictures, manifestos, images, i.e. microhistory artifacts), «[…] for Morrison, possessed [their] own historical weight and [were] not assimilable to confident determination of the past. […] [H]er intention was not to integrate readers into a discourse of “their history” but to confront them with buried memories—things in which they might not even recognize themselves»[4]. This happened in Beloved, where the heinous action the mother did, Sethe, to free her children from the burden of slavery, of dehumanisation, and where the ghost of her murdered daughter represents the connection between present and past; this past, this history that comes back to haunts the living, those who are here, where the fathers’ pain hurts the sons, as in Song of Solomon, where the latter cannot give to this suffering a meaning, because they don’t remember. Past, history and memory are perceived in the acts of the presente, because it’s their result. Recollect this history and this tradition is to build a denied identity, it’s the recover of humanity. A recollection of past that becomes a literary practice, and thus a political actions, because ««[i]n so doing, Morrison’s oeuvre has fostered new understandings of the black self, bringing it to the fore and reimagining its representation as ‘a central symbol in the psychological, cultural, and political systems of the West as a whole’. […] Morrison's novels address the indefinite substance of such a cross-cultural identity and the difficulties of creating that identity in the face of racist opposition and cultural ambivalence»[5].

Oral tradition as construction of memory

The construction of a collective memory, and thus the redefinition of the historical concept of a community, also means the recollection of traditions, values and symbols of a culture determined ad oppressed and the appropriation of those practices of the hegemonic culture used as instruments of coercion and delimiting as alternative expression. In Toni Morrison, this appears as the recover of certain practices and expression belonging to the African cultura, which Afroamerican people used as the ground to build on their own sociological narration. The most important traditional practiced that Morrison uses as narrative device or as techniques of construction of her own rhetoric are the magic enemy’s and orality, where the latter brings to the former.

In an interview, Toni Morrison describes her creative process, that is the reading; she wrote her novel as they’re read, as they are oral stories, and not modern novels. The musicality, the perception and the participation of the Other, and thus of the reader, the word that has got magic power (i.e. evocative writing), the word as imaginary and instrument of communication, of sharing of meanings, are part of Morrison’s writing process. In oral civilisations (that are those societies where only oral language exists), the communicative system is based on conservation and transmission of facts, events and narrations – than on syllogism – whose purpose is to maintain the cultural processes and social foundations. Orality is, thus, the sharing of symbols, images, ideas but also definition of social characteristics, and so of unity and communion between individuals who share those proactive and answer to them (because this is the aim of communication: unite people). Another fact must be highlighted: communication of post-modern societies is called, by social sciences, as secondary orality, a phenomenon provoked from the raise of social networks, a sort of written orality, that «[…] has generated a strong group sense, for listening to spoken words forms hearers into a groups, a true audience, just as reading written or printed texts individuals in on themselves. But secondary groups immeasurably larger than those of primary oral culture – McLuhan’s ‘global village’. […] [S]econdary orality promotes spontaneity because through analytic reflection we have decided that spontaneity is a good thing. We plan our happenings carefully to be sure that they are thoroughly spontaneous»[6]. In a certain sense, Toni Morrison seems she had anticipated this communicative characteristic of post-modernity, this secondary orality, this written orality. An orality that exists in the poetics and in the narrative rhetoric of her books, thus melody, this music infiltrated into the words, into the stories, this voice that tells, the story says. Not written word, but word said. Orality that’s not only part of the writing, but it’s also part of the same narration, where the characters define themselves through their own stories, they create their own narration, they connect, in this way, the past with the present, they make their children and grandchildren partecipate to that personal memory, that, for being extraordinary, is also collective. Collective because it’s shared, because capable of building a common identity, a story that connects people and from which these individuals recognise themselves. An orality that is not only a storytelling instruments, but the recover of traditions, the catharsis of traumatic events which define the imaginary of a whole community. «Oral storytelling tradition in African American literature has been recognised by many critics as a remnant of West African oral cultures in African American tradition and has been documented as a means of cultural continuation during slavery»[7]

Second part here

Viviana Rizzo @livethinking

#Toni Morrison#memory#collective memory#identity#resistance#beloved#song of Solomon#literature#writing#article#culture#freedom#black history month#black lives matter

0 notes

Text

#neverforget

The tour of remembrance: testimony what happened

(For more pictures, visit https://spark.adobe.com/page/qv4Rkt2zw9iqD/)

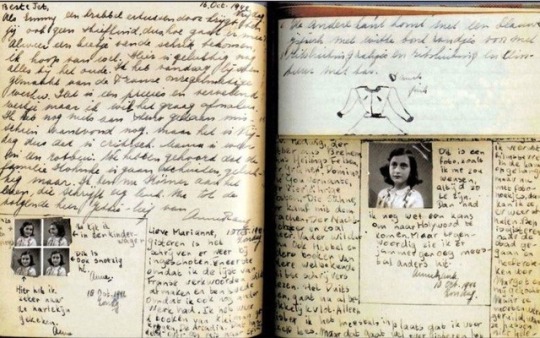

We get used to say violence is inherent in man, it’s imperfect part of humanity, but what happened from 1939 to 1945 - correspondent to that extermination called Shoah or Holocaust - are beyond what’s human and painfully survivors told their testimonies which I’m subscribing for a duty I received and gave who faced this memory trip: testimony what happened.

Principle of the disaster was the ghettos: one of the first was in Cracow (in Poland) which appears like a very normal neighbourhood of any big city: buildings, shops, families who pass their days; although those walls, those buildings don’t communicate quite, serenity but a sensation of heaviness, of a melancholia perceived by soul. The Cracow ghetto, one of the first built, delimited between two natural barriers which are the Vistula river and a cliff, was the principle of the disaster. Like a prison, the Jews who lived there hadn’t chance of going out, they were prisoners without fault when they went out for a walk among their familiar streets, they must have watched back, kept their own gazes down because nazi officers, often, shot and killed men whose names and faults they didn’t know just because it was ordered and because those officers had no consciousness but only evilness.

There were also a kindergarten in the ghetto, which was, unfortunately, place for one of most great tragedies, that is the killing of innocence thus the end of hope. One night, nazi soldiers went to that kindergarten prelating all the children (their parents had left them here during they were at work) to take them to a forest where was a cliff, and there was committed on of the most violent actions: they executed them. Children’s death had been decided due to the loss could limited will of fighting, living and hoping. That place is now a playground rounded of a crag which seems wanting to fall on you. It’s surreal and monstrous and I laid my steps down there, in that quite which was echo of shoots.

The ghetto could be considered the first stop for that train will have conducted thousands of innocents to the end, to concentration camps.

Auschwitz II - Birkenau, 120 hectares of tragedy delimited with barbed wire (electrified at 40 Volt), is one of the hugest concentration and extermination camp. The deported ones were taken, as it’s known, along the railway which extends itself beyond the camp entrance, stored inside freight wagons. They showed us one: more than a wagon, it looks like a rotten wood box without openings, excite some hole in the wood. Freights like food or postal packages had to transport inside, instead were stored ten people without food and water. Even not to go into, you can perceive the claustrophobia sensation, the instinct of pushing for getting your own space, for breathing, for living upon the mind. The sensation of losing breath seems real.

Birkenau is impressive even just observing the entrance: immerse in a everlasting fog, it seems the light has never crossed it, the grey which hovers in that zones were the immense pain of all those women, children, men and old people had suffered and even now they still perceive it inside their heart, like Sami, Tatiana and Pietro, who too much young they had to know the whole humanity’s evilness. Birkenstock becomes the hell on earth, not as it shows itself but as appears in survivors’ stories, which seems materialise in those lands. Like Sami who had to watch his father submitted to violence of SS, who had to suffer cold, hunger, his father’s and his 14-years-old sister’s death. Like Tatiana who still child had to see her world falling apart, her childhood go away and grow too soon. Or like Pietro who saw alla his family leaving little by little, was exiled from his Country and people he knew and then came back here, lonely and with nothing.

They took off everything: goods, identities, name, dignity and who was not enough string or necessary to satisfy the sadism of those men who men are not, the nazi soldiers, was directly sent to die in gas chambers, for example old or ill people and pregnant women. Who was enough, they were sent to the Sauna, a building where the deported ones were registered.

At the end the barracks, the wooden ones where men sleeps and masonry ones where were women. 52 horses should have stayed in barracks, instead over 200 people were sleeping. Children stayed alone with a woman who cared of them, surrounded by illustrations made by adults for cheering them up during those long day without sun and during those long night without dreams on bed, cement and wooden holes. Men who were long for women, in distance, a familiar face, their own mother, wife, daughter, sister; women who were looking for their own father, husband, son, brother and they didn’t give up only to remember of being people and not beast, as they were treated.

Who stayed strong or who gave up, who repeated to itself the Divine Comedy (like Primo Levi) to remember to have dignity and consciousness or who abandoned to instinct. So many people were there that you have no idea how many they were from stamped names on history books but from memories they left, from their remains, from their dresses.

In Auschwitz I were set up shreins containing deported ones’ goods found in Canada Barrack (the mane linked to richness of that Country). This second concentration camp is different from Birkenau for the architecture (but not different for suffering). It’s smaller (it’s 12 hectares circa) and previously it was an army camp, indeed you can notice the masonry buildings height two or three floors which fill the camps, where the deported people slept. Now inside there are found goods exposition: entire room containing glasses, suitcases with belogers’ sign, shoes, dresses, hairbrushes and hair. Hundreds, thousands and every object represents an alive or dead person who stayed there. It seemed to me that from each thing the people who had them materialise, and they were too much. There were also pictures: normal people, girls and boys who smiles, families in pose and portraits of lovers. They had joyed and cried, had a story, ideas and memories and now they disappeared because someone took the right of deciding who can live or die for diseases, hunger, killed or in gas chambers.

Gas chambers whicharenhot look like showers but more like a trove, masonry parallelepipeds where you are not able to breath, where there’s no light except from those lamps or filtered by the holes where the gas were introduced, innocent looking greyish green rocks which were been heated. A corridor with grey walls collected thousand people crammed who were not able to dilate lungs, to push. It doesn’t seem a shower, as many tell, flagons are there but are not seen and they’re oxided, the lobby with rooted wood floor scared. You begin to tremble on,y standing ahead the entrance, even the smells in air is different, heavy and acid, even the sky colour, pale and colourless.

Colourless is also the crematorium room on the other side where two or three ovens rises, small and little deep and rusty, and overlying wall is still black for the smoke.

In that place we notice the violence and dangerousness of indifference, what ignorance and not denouncing could provoke, the silence and the cynism,

These trips are organized not only to know new historic facts or understand the deported people’s pain but to realise the duty of never been silent afterward violence,never been submitted by oppressive regimes and believing lies. They have passed us the torch, they have given us the responsibility of making eternal the memory, that stories, not only for us but for the best future we can achieve.

Viviana Rizzo @ilbiancodellefarfalle @livethinking

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pride and Prejudice: the relationships inJane Austen’s novel

The fable of Pride and Prejudice is built on those dynamics developed from the relationships between the characters of the novel, and only this narrative construction can cause the events. Yet, the relationships between characters are not all the same: they can be opposition relations, wherein an opponent hinders a subject’s aim towards an object (speaking in Mieke Bal’s terms), or a supporting relationship between a helper and a subject. Moreover, these relations may be developed between an individual and a power or between the former and his own background; indeed, society becomes an opposing power here, as happens with Elizabeth Bennett, or a helping power (especially with those who are able to adapt themselves to values and norms of that social system). Opposing powers are also pride and predjudice, the two concepts which are in the title of Jane Austen’s novel. Thus, in this sense, we could talk about Pride and Prejudice as a novel of relationships.

Subjects and objects in Pride and Prejudice

«The first and most important relation is between the actor who follows an aim and that aim itself. That relation may be compared to that between subject and direct objection a sentence. The first two classes of actors to be distinguished, therefore, are subject and object: actor x aspires towards goal y. X is a subject-actant, y an object-actant»[1].

Given this definition, if we should think of who the subject is in Pride and Prejudice, we would say that all the main characters of the novel are, because everyone has his or her own goal, that is the object towards every action and every choice aim; the object is here a person or a hope but, overall, a marriage.

Marriage, or better, the ambition of getting married in Pride and Predjudice is the common denominator of narratological relations established among character, is the connection between events. It’s the object to which all subjects of the novel. That was explicated by Mrs. Bennett, wishing all her daughters married «’If I can but see one of my daughters happily settled at Netherfield," said Mrs. Bennet to her husband, "and all the others equally well married, I shall have nothing to wish for’» ; indeed, one of the younger Bennett sisters, Lydia, made an extreme action to reach her goal, as we’ll see in chapter 4 vol.III, when she ran away with Mr. Wickham. Marriage is dignifying to men and the only chance allowed by society for a woman to establish theirselves of the first half of 19th century. And in these dynamics that further subject/object relations develop, always correlated to the desire of marriage. Among these also Mr. Bingley’s wish to marry Jane Bennett; the same for Miss Bingley towards Mr Darcy (but never saying it explicitly) that is in Lady Catherine De Bourgh’s designs, his aunt, who would like seeing him married to her daughter, as Lady herself told Elizabeth «’The engagement between them is of a peculiar kind. From their infancy, they have been intended for each other. It was the favourite wish of his mother, as well as of hers. While in their cradles, we planned the union’»[2].

Elizabeth, the protagonist, soon becomes the object to her father’s cousin, Mr, Collins, who proposed to her, and even to Darcy «’In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you’»[3].

Beyond subjects and objects: opponent/helper relations

It’s not possible to reduce the interpersonal relationships of the novel into such dialectical relation, the fable of Pride and Predjudice may get too simplified. Further kinds of relation comes into play to set in motion events: not only about wishes and desires. Mieke Bal, in Narratology, also talks about opponents and helpers[4]. The opponents are those who hinders the other characters’ path; on the contrary, the helpers are the supporters. A character can be both and, therefore, an opponent or a helper can also be a power too, – not necessarily a person.

In Pride and Prejudice opposition relations result from the clash between two subplots – i.e., the relation an anti-subject has towards an object, that could be or a same or different one from the principal –, or between two ambitions; this happens more frequently when the object is the same (e.g. Mr Darcy as object to both his aunt for her daughter and to Elizabeth on the last part of the novel, occasion that caused resentments between the two women). The most resolute and principal opponent of the story is surely Lady Catherine De Bourgh, who, by virtue of social norms, rejected the very idea of a supposed marriage between Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth.

«”While in their cradles, we planned the union: and now, at the moment when the wishes of both sisters would be accomplished in their marriage, to be prevented by a young woman of inferior birth, of no importance in the world, and wholly unallied to the family! Do you pay no regard to the wishes of his friends? To his tacit engagement with miss de bourgh? Are you lost to every feeling of propriety and delicacy? Have you not heard me say that from his earliest hours he was destined for his cousin”»[5].

From this example we can introduce the opponent as power, as a non-person. In Pride and Prejudice, the social system, built on classes, is one of the opponents that hinder a subject’s aim; marriage like those between Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy or between Mr. Bingley and Jane are rare because they’re between two people come from different costal class and norms of that system allow complaints such as Lady Catherine De Bourgh’s, or the Bingley sisters’ dislike for Jane Bennett, although subtle.

Other opponent of this kind can be considered the two concepts from the title, Pride and Prejudice: Mr. Darcy’s pride, which lead him to not open to a community of a lower social class; and Elizabeth’s prejudice towards Mr. Darcy, which lead her to refuse the man’s proposal (considered offensive by the girl), and the positive one to Mr. Wickham, revealed to be a dissolute. Pride and prejudice, which impede an authentic acquaintance between the principal character of the story written by the great Jane Austen.

Particular is the position of Mr. Darcy, who’s both an opponent and a helper. Opponent when he impeded the relationship between his friend mr. Charles Bingley and Jane Bennett, as he will have confirmed in his letter to Elizabeth.

«“But Bingley has great natural modesty, with a stronger dependence on my judgement than on his own. To convince him, therefore, that he had deceived himself, was no very difficult point. To persuade him against returning into Hertfordshire, when that conviction had been given, was scarcely the work of a moment. I cannot blame myself for having done this much”»[6].

He’s a helper when helps to find Lydia across London and pushing Mr. Wickham to marry the girl as to preserve the Bennetts «“He [Mr. Darcy] came to tell Mr. Gardiner that he had found out where your sister and Mr. Wickham were, and that he had seen and talked with them both; Wickham repeatedly, Lydia once.»[7]. A gesture capable of wiping away Lizzy’s prejudice and to help Mr. Darcy to reach his goal, that is to marry the protagonist of the novel. In this way other characters took part to give a support. The most importance of these were maternal Elizabeth’s uncle and aunt, Mr. and Mrs. Gardner, who, during a trip, convinced Elizabeth to see Pemberley, Darcy’s residence, where they met Mr. Darcy himself and discover a more affable and kind side of the man.

«Her [Elizabeth’s] astonishment, however, was extreme, and continually was she repeating, ’Why is he [Mr. Darcy] so altered? From what can it proceed? It cannot be for me, it cannot be for my sake that his manners are thus softened’»[8]

Notes

1. BEL, Mieke, Narratology: introduction to the theory of narrative, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1997, p. 106

2. AUSTEN, Jane, Pride and Prejudice, Penguin Classics, UK, 2003, iBooks, p. 48

3. Ivi, p. 324

4. Ivi, p. 19

5. Ivi, p. 324

6. Ivi, p. 201

7. Ivi, p. 296

8. Ivi, p. 244

Source

AUSTEN, Jane. Pride and Prejudice, Penguin Classics, UK, 2003, iBooks

BEL, Mieke. Narratology: introduction to the theory of narrative, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1997

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph Brodsky: to translate is to exist

The poet lives in his poems and only through these he can assert his own existence; the poet can be oppressed, censored, encaged, also killed, but until he can write, until there’s someone who reads his poem, he will go on living, he will be free despite all. Deported poets, exiled poets, poets oppressed by a dominant and colonial culture, but still poets, although they have lost their language. And as it’s possible to lose a language, it’s possible to find a new one to tell about the self in verses; this was well-known to Joseph Brodsky, a Russian poet and author, moved to the USA because he was condemned for parasitism and for a cultural environment more and more saturated with hostility and suspicion which censored and hinder the publication of his poems, shut his poetical voice through editorial obstructionism, denied his existence as an author, and thus also as human.

Brodsky’s verses didn’t officially exist in the Soviet Union (but read clandestinely and published via samizdat), so he didn’t exist himself as poet, as man and to exist, he had to make the hardest of the choice: leaving his home country, his native language, denying it because this language refused his creative soul. He left Russia after he was compelled by the regime, he moved abroad and reaching the USA, a Country completely different from the Soviet Union, too much free, too much noisy, but perfect for Brodsky’s poetry. There he translated his rhymes in English and his works were officially published, there Brodsky exists, there his art is loved. There’s no way to oppress the voice of a poet, because it will always find a way to speak, as well as self-translation, instruments of poetic (and cultural) resistance, as well as changing the language, the Country, traditions. Also forgoing himself.

Self-Translation is when author and translator are the same person, when an author translate his/her own literary work. As it happens in translation, there’s an original and a translation, or there’s no translation (when the author chooses to write in a language different from his/ native ones, a behaviour that in very common among colonial and post-colonial writers). The Self-Translator is a bilingual and, often, bicultural (because he/she is an immigrant or a child of immigrants, lives between frontiers or in a former colonised country). On the contrary to a translator, the author who chooses to translate him/herself has access to the original intention (i.e. now and why the author chooses to write a certain expression and the original meaning), original cultural context or literary intertext. This possibility has, however, some limits: the famous psychoanalyst Carl Jung explained that neither the author is completely omniscient (aware of what he wrote in the past) and «[…] have to read it again and may not even completely understand their own motivation for choosing certain passages, certain examples or a certain style»[1]. The most famous authors who translated their own works were Samuel Beckett (from English to French and German, and vice versa) and Vladimir Nabokov (from Russia to French, and vice versa).

What are the types of Self-Translation?

Michaël Oustinof identified three types of Self-Translation:

1. Naturalising Translation (naturalisante): when an author gives priority to the characteristics of the target language (that is that language a text will be translates into).

2. Decentralised Translation (décentrée): when an author introduces in the target language foreign elements that belong to the source language (that’s the language a text is written in).

3. (Re)Creating Translation((re)créatrice): when an author translate and change his/her literary work (or omit some parts) in order to adapt the text to both the target language and culture.

Who are the authors that translate themselves?

1. Bilingual (or polyglot) authors who wants to expanse their audience or just experimenting. Usually, there’s a relation of symmetry between the source and the target language (e.g. French and English). It’s the case of Samuel Beckett.

2. People who speak minority language but choose to write with a dominant language. It’s the case of Luigi Pirandello who translated his plays in Italian from Sicilian dialects.

3. Colonial or post-colonial author who write both in their native language and colonial language.

4. Exiled or emigrant authors who write in the language of the Country they moved to. It’s the case of the Russian Vladimir Nabokov who, after moving to France, started writing books in French (such as his famous novel “Lolita”) and the same Joseph Brodsky.

The case of Brodsky and other Russian emigrée is a unique case of self-translation. Usually, who translate theirselves are those authors living in a condition of colonialism, i.e. they’re from a colonised from another of more prestige and political and cultural power, consequently their native languages becomes hegemonic to the language spoken by the colonists; the authors who live this kind of experience chose to translate their literary pieces to the dominant language, that is the colonist one, so that their work can emerge from a state of oppression, then reaching a larger number of readers and settling their existence as a creative and make raise their culture from the barriers of the dominant one and speak to the colonists through that; so, we’re talking about a form of cultural resistance.

Emigrant Russian authors didn’t choose to translate their world into the language of the Country which welcomed them, because their native culture weren’t oppressed, but because they were oppressed by their own culture; their works were usually divergent from the aesthetic ideals of the regime, thus they were censored or the official publishing was denied (and, often, neither by Russian magazines abroad); to survive as writers and giving life to their literary pieces, most of these authors chose to translate themselves. This kind of self-translation is, in this case, symmetrical, according to Rainier Grutman, because Russian and Western languages have got the same literary prestige, and the bilinguism here is exogenous (always according to Grutman’s definition) because these languages (especially about the relation between Russians and English) have never shared the same geographical spaces.

What pushed Joseph Brodsky to leave his home country and starting a new life and a new poetic and translating in the USA was the accuse and the arrest for parasitism, happened in 1964 (for which Brodsky was interned in the psychiatric hospital of Moscow and after deported and condemned to the forced labour near Arkhangelsk, on the extreme North of Russia). Thanks to his fame, he was freed in the November 1965 after a petition signed by Russian and foreigner colleagues but for the Party Brodsky was a hostile figure to the regime; in fact, when we requested a permission to go abroad, after he was invited by Robert Lowell to attend the International Festival of Poetry in London, «the Union of Soviet Writers answered there were no poet with that name in Russia: he was crossed out from the official list of Russian writers»[2]; they denied him the right of writing, the natural right to proclaimed himself poet and for a real poet this means denying his life, denying his dignity. Refusing his poetry is to refuse him and thus happened when, in 1972, he was commanded to leave the Soviet Union; that means he was not welcomed by his move country, his Russia, his Russian any longer. So, what can a poet do? Brodsky remembers: «on 10th May 1972 I was called out and they told me:”Take advantage of one of the invitation people make to you to leave for Israel. We prepare a visa for you in two days”. “But I don’t want to take advantage of”. “So, prepare for the worst”. I couldn’t do anything but to give up: I managed to make the gems prolonged to 10th June (“after this date, you’re going to have no identity card, absolutely nothing”): I wanted to pass until my 33rd birthdays with my parent in Leningrad, the last one. When they gave me the expat visa, they make me jump the line: there were many Jews waiting days and night for the visa who looked at me astonished, envying me […]. I past the last night in the USSR writing a letter to Brezhnev. The following day I was in Vienna»[3]. He was in Vienna when he met the English poet Brodsky loved most, Wystan Auden, with whom he attended the International Festival of Poetry in London, event that allowed him to meet other authors from the literary Anglo-Saxon world, such as Robert Lowell, but he already left Vienna to move to the US in the July of the same year: he was offered to work to the University of Michigan (where he taught until to 1980). Thus began one of the most important phase of Brodsky’s work and his path to self-translation, which allowed him to reborn as a man and a poet. He lost his language, his Country, but he found a new language through which thinking, loving, writing, through which expressing himself, through which existing. To write is to exist.

Translating ourselves to exist, translating as that our own work to overcome national and cultural borders, to destroy linguistic barriers, to annihilate the borders. «Civilization is the sum of total of different cultures animated by a common spiritual numerator and its main vehicle – speaking both metaphorically and literally – is translation. The wandering of a Greek portico into the latitude of tundra is translation»[4]. Translation is what allows us to converse with other cultures, with the Other, and the translator is, thus, a cultural mediator that lays between two interlocutors and help them to understand each other, not only linguistically, but also culturally, that let bonds between values, norms and beliefs be understandable to who doesn’t know them. Brodsky gave new life to his poems, already oppressed by the hostility of Soviet regime, and he gave the, new social coordinates, although he destroyed the grammar, i.e. the foundation of English language in order to adapt this language to the linguistic malleability of Russian, in order to everything, the intrinsic structure and so the semantic built by that could persist. «Brodsky […] insisted strongly on a mimetic translation i.e. a translation which would retain a poem’s verse structure – especially its rhymes, verse metre, rhyme patterns and stanzaic design should be preserved above all»[5].

A mimetic translation, them, which doesn’t break the architecture of poetry and it fits, as well, the presence of Russian soul in the English language and so the in grammar and morphosyntax, that comes from Pushkinian tradition, according to the form and the content corresponding and so, none of them should be sacrificed in the translation. A tradition enhanced by the Acmeists (such as Anna Akhmatova and Osip Mandelshtam), from whom Brodsky took inspiration. According to the Acmeists, in translation, must be preserved the number of lines, verse metre, rhyme patterns, types of enjambements, rhyme types, linguistic register, types of metaphor, special devices and changes of tone. Following this tradition Brodsky translated his poems from Russian into English, though transforming and upsetting the target language, though drowning bitter criticisms for that which will be have called “Englishness”. Upsetting the language in order to appear himself as a poet, as a Russia. His soul must have to emerge, if he wanted to live through poetry, and the only way to do it, in this case, is to annihilate the rule of the other language, a language chosen to survive. This foreigner who transformed a language that is not his to make it an instruments of resistance, an instruments of existence.

The harshest criticism towards his English was from the British School, which blames Brodsky of transforming the language to make it adapt to his needs; a criticism that hide the will to protect the integrity of the language from an “intruder” like the Russian Brodsky. Despite all, the poet received much esteem, especially from the American School which appreciated his experimenting with the language. Experimentalism due to the dissatisfaction of English translation to Russian poems that Brodsky criticized because they were not capable to keep the complex morphosyntactic structure of the poetic of Russian language. He wrote about it: «Translation from Russian into English is one of the most horrendous mindbenders. There aren’t all that many minds equal to this. Even a good, talented, brilliant poet who intuitively understands the task is incapable of restoring a Russian poem in English. The English language simply doesn’t have those moves. The translator is tied grammatically, structurally»[6].

Even though his approach which was very little conform to modern translation theories, even though we can blame him to have turned upside-down the English and so we can speak of Englishness in his poems, Brodsky «[…] approached his translation with a fervour verging on the quixotic, squaring the circle of poetic translation, defying the spell of impossibility and bridging single-handedly the linguistic gap with great energy» [7].

Viviana Rizzo

Notes

1. AA.VV., Handbook of Translation Studies, edited by Yves Gambier e Luc van Doorslaer Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2010, p. 306

2. «L'Unione degli Scrittori Sovietici rispose che non c'era nessun poeta con quel nome in Russia: era stato depennato dalla lista ufficiale degli scrittori russi», in CONDELLO, Anna, “Iosif Brodskij: una biografia intellettuale”, in Russian Echo, web (http://www.russianecho.net/contributi/speciali/brodskij/bio.html retrieved in 28th May 2021)

3. «Il 10 maggio 1972 mi chiamano e mi dicono: "Approfitti subito di uno dei tanti inviti che le vengono per emigrare in Israele e parta. Le prepariamo il visto in due giorni". "Ma non ho nessuna intenzione di approfittarne". "E allora si prepari al peggio". Non potevo far altro che cedere: sono riuscito al massimo a farmi prolungare i termini fino al 10 giugno ("dopo questa data non ha più carta d’identità , non ha più niente"): volevo almeno passare a Leningrado il mio trentaduesimo compleanno, con i miei genitori, l'ultimo. Quando mi hanno consegnato il visto d'espatrio, mi hanno fatto saltare la fila: c'erano tanti ebrei che aspettavano, che bivaccavano là in anticamera giorni e giorni in attesa del visto e che mi guardavano esterrefatti, con invidia [...]. L'ultima notte in Urss l'ho passata scrivendo una lettera a Breznev. Il giorno dopo ero a Vienna», in CONDELLO, Anna, “Iosif Brodskij: una biografia intellettuale”, in Russian Echo, web (http://www.russianecho.net/contributi/speciali/brodskij/bio.html retrieved in 28th May 2021)

4. BRODSKIJ, Iosif, “The Child of Civilization”, Less than one, London, Penguin, 1986, p. 139, cit. in ISHOV, Zakhar, “Posthorse of Civilisation”: Joseph Brodsky translating Joseph Brodsky. Towards a New Theory of Russian-English Poetry Translation, Berlin, Freien Universität Berlin, 2008, p. 2

5. ISHOV, Zakhar, “Posthorse of Civilisation”: Joseph Brodsky translating Joseph Brodsky. Towards a New Theory of Russian-English Poetry Translation, p. 4

6. SOLKOV, Solomon, Conversations with Joseph Brodsky, New York, The Free Press, 1998, p. 86, cit. in ISHOV, Zakhar, “Posthorse of Civilisation”: Joseph Brodsky translating Joseph Brodsky. Towards a New Theory of Russian-English Poetry Translation, p. 5

7. ISHOV, Zakhar, “Posthorse of Civilisation”: Joseph Brodsky translating Joseph Brodsky. Towards a New Theory of Russian-English Poetry Translation, p. 3

Sources

1. COCCO, Simona, “Lost in (Self-)Translation? Riflessioni sull’autotraduzione”, in AA.VV. , Lost in Translation. Testi e culture allo specchio, vol. 6 (2009), pp. 103-112

2. GRUTMAN, Rainier, “Beckett and Beyond. Putting Self-Translation in Perspective”, in Orbus Litterarum, n. 68, vol. 3 (2013), pp. 188-2016

3. GRUTMAN Rainier, VAN BOLDEREN Trish, “Self-Translation”, in A Companion to Translation Studies, edited by Sandra Bermann and Catherine Porter, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2014, pp. 323-332

4. ISHOV, Zakhar, “Post-horse of Civilisation”: Joseph Brodsky translating Joseph Brodsky. Towards a Mew Theory of Russian-English Poetry Translation, Berlin, Freien Universität Berlin, 2008

5. MONTINI, Chiara, “Self-Translation”, in Handbook of Translation Studies, edited by Yves Gambier and Luc van Doorslaer, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2010, pp. 307-308

6. WARNER, Adrian, “The poetics of displacement: Self-Translation among contemporary Russian-American poets”, in Translation Studies, vol. 11. N. 2, 2018, pp. 122-138

#Joseph Brodsky#self-translation#translation#Russian Literature#Cintemporary Russian Literature#literature as resistance#translation studies#literature#USA#USSR#Soviet Union#Russia#politics#culture#regime#dictatorship#migration#writing#blogging

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

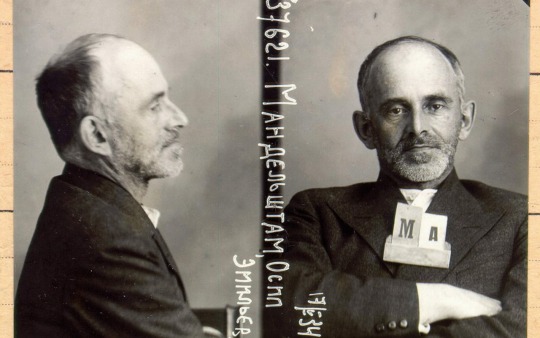

Hope is the last to die: how Nadezhda Yakovlevna saved Osip Mandelshtam’s poems

If we can still read the Voronezh Notebooks, it’s because the courage and perseverance of Nadezhda Yakovlevna Mandelshtam (nee Khazina) who, for love, learnt by heart every single lines written by her husband, Osip Emilevich Mandelshtam, in order to transcribe them; who, for love, travelled throughout the whole Russia to run away from being arrested and so saving the few manuscripts left (which many of them were destroyed, got lost, or stolen by the Rudakovs), including during World War Two German invasion in Russia; who, for love, was able to spread Mandelshtamks poetry collections via Samizdat and managed to, after several attempts, make rehabilitate his husbands name. A love that in Nadezhda’s memoir seems imperfect but it’s stronger than Stalin’s regime, than censorship, than hunger; a love that overcame death. Love for Osip and his works, for culture, for freedom. It doesn’t seem a coincidence that her name is Nadezhda, which means “hope” in Russia and, indeed, she had never surrendered to fear because she hoped sooner or later her husband’s books could be published officially again. Nadezhda Yakovlevna collected and saved from war and secret police partly for Mandelshtam’s archive, hiding the manuscripts inside pans or sewing them to pillowcases, learning by heart her husband’s verses in the night of during her night shift in a textile factory (where she worked after Mandelshtam’s death, during her pilgrimage to run way from NKVD, and before getting a job as English language teacher). But Nadezhda didn’t only save the poems, she writes in her memoir: «I am now faced with a new task, and am not quite sure how to go about it. Earlier it was all so simple: my job was to preserve M.'s verse aod tell the story of what happened to us. The events concerned were outside our control»[1]. During Khrushchev’s era, she wrote three memoir books, Vospominaya, Vtoraya kniga e Kniga tretya (further a critical book on Osip’s poems, Kommentarii k stikham), first published in the US, the first under the title of Hope Against Hope in 1970, and the second one as Hope Abandoned, in 1974. In these memoirs she tells about her husband, the poetic work, the last years of Mandelshtam’s life with poignancy and much resolution, the horrible years of Stalinian Terror, nor missing to scold those intellectuals who committed to the socialist realism and bureaucrats but understanding the people, who ere in turn victims of fear and poverty. Her memoirs are «a scream of pain suffered for decades», pages that tell not only Nadezhda and Osip’s life together, but that also enlighten the abyss where they fell into. Those pages is a scream of hope after much silence and the continuation of Osip Mandelshtam’s testimony. Nadezhda moved her lips for him, when he couldn’t do this anymore.

Nadezhda Yakovlevna didn’t limit herself to this: she edited the Samizdat edition of the last Mandelshtam’s works, even though she wanted her husband’s poetry would have been published officially. She realised how huge was the circulation of this clandestine edition and she got surprised, because, despite the education system designed to affirm the socialist realism as the lonely critical canon, despite the censorship, the discrimination against a certain group of intellectuals and the destruction of the intelligentsia, «new readers come into being before our very eyes, but to understand how it happened is quite impossible. All one can say is that it came about against all the odds. The whole educational system was geared to preventing the appearance of such readers»[2]. Poetry can’t die because it’s life itself, because there will be always someone who manages to save and transcribed verses, including during terror, because it’s only in this way we can protect our Ego when everything is divided in indefinite “us” and “them”.

During Khrushchev era, Nadezhda understood something was changing and several names there weren’t published any longer, got rehabilitated. Osip Emileivich Mandelshtam’s name appeared only in samizdat and many didn’t dare to pronounce it yet; his name too should have been rehabilitated because he was arrested and condemned while he didn’t commit a crime, and so Nadezhda Yakovlevna, in the middle of the 50s, tried to get Mandelshtam rehabilitated, meeting Aleksey Surkov several times, poet and prominent figure of the Union of Soviet Writers. In 1956, Osip Mandelshtam will have been cleared from the accuse of “counterrevolutionary activities” of 1938, but only in 1987, during Gorbachëv’s administration, his name was completely rehabilitated and cleared from all the charges. Still through Surkov’s help, in 50s, Nadezhda tried to get published all Mandelshtam’s works officially. If Surkov was optimistic, many times the Party denied this idea, especially after the “Zhivago affaire”; Mandelshtam kept being a controversial name. Official publication of Mandelshtam’s work happened only in 90s. Nadezhda Mandelshtam died in 29th December 1980; after ten years her death, in 1990, the Voronezh Notebooks appeared in a complete and official edition in Moscow. «My odd experience, that as witness to poetic work, tells me it’s impossible to put a foot in the throat, it’s impossible to put a muzzle. It’s one of the most sublime human expression, bringer of universal armonies, and it can’t be anything else»[3].

Viviana Rizzo

Reference:

[1] MANDELSHTAM, N.J., Hope Abandoned, New York, Atheneum, 1974, p. 3

[2] Ivi, p. 9

[3] «La mia strana esperienza, quella di testimone del lavoro poetico, mi dice che è impossibile mettergli un piede sulla gola, impossibile infilargli la museruola. È una delle espressioni più sublimi dell'uomo, portatore di armonie universali, né altro può essere», in MANDEL’ŠTAM, N. J., L’epoca e i lupi. Memorie, with an introduction by Clarence Brown, trans. Ita by Giorgio Kraiski, Milano, Mondadori, 1971, p. 221

Sources:

1. FRISIA, A., “Coraggio e poesia. Osip e Nadežda Mandel’štam” in Gariwo: la foresta dei Giusti, web, 30.10.2014, p. 6, https://it.gariwo.net/dl/201410300557_30%20ottobre%20Osip%20e%20Nadezda.pdf (retrieved 18 November 2020)

2. KUVAKDIN, J.,, “Ulica Mandel’štama. Povest’ o stikakh”, in Bibilioteka Aleksandra Belousenko, web, 16.11.2004, https://web.archive.org/web/20071017204834/http://belolibrary.imwerden.de/books/Kuvaldin/kuvaldin_mandelshtam.htm# (retrieved in 20 November 2020)

3. MANDELSHTAM, N.J., Hope Abandoned, New York, Atheneum, 1974

4. MANDEL’ŠTAM, N. J., L’epoca e i lupi. Memorie, with an introduction by Clarence Brown, trans. Ita by Giorgio Kraiski, Milano, Mondadori, 1971

#Osip Mandelshtam#Nadezhda Mandelshtam#Russia#USSR#Russian literature#Russian poet#women’s history month#women#girl power#strong women#Stalin’s regime#Stalinism Terror#censorship#dictatorship#Stalin#poetry#poems#Voronezh Notebooks#writing#blogging

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Poetry is not a luxury»: Maya Angelou, Gwendolyn Brooks, Margaret Walker and poetry as resistance

«Poetry is not a luxury»[1], Audre Lorde said. Poetry is not a game, another amusement to dampen the boredom of a humdrum life but it’s a need, a necessity as instrument to the battle against oppression, to self-determination and to identitary resistance because «poetry is power»[2]. And this is as much true and confirmed when poetry becomes activism, when lyricism expresses, and thus bears witness, a discomfort and makes it universal, fathomable through the poetic language; when writing in verse is the only way to express ideas and makes sure they’re recognised in their own dignity, thus it’s necessary in order to save and let respected the existence of that human being who has thought it, in order to this existence can be recognised as such, can arise from oppression and systematic hate, can give voices to those whose lips were ripped off, such as women, for whom «[…] poetry […] is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we [women] predicate our hopes and dreams towards survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought»[3], so, poetry’s place where they can expresses opinions, needs, dreams, hope, in other words themselves, where the cultural system gives preference to other voices, wherein censorship is not official, i.e. perpetrated by an organisation or a law, but it’s cultural because it’s the culture that systematically chooses (a given social class) what creative expressions are more or less are in line with its own values or strengthen them. That’s why for centuries poetry (but also the whole literature) has been place wherein affirm ourselves and the individuality of our own identity, or express pride for a communitarian identity; as it was for women, who found in poetry an instruments they can express their real self through, getting out of the patriarchal control and out of the role they were bonded to by society and came less to the expectations of this one. In this way, women could so analyse her being woman, dreaming to choose who are and what to do, self-determinising and exploring their femininity beyond believes given by a certain historical moment; as it was for black community, wherein black poets could express the a beauty, the varieties, the complexity of their subculture, their traditions, history and so express the pride of being part of this ethnicity, fighting against racism and networking against the oppression perpetrated by a system that privileges white citizens (and more often men). These two concepts converge into the poetic experience of black women poets, for whom poetry became a place wherein speaking of their experience as women and black citizens, wherein they can exist and affirm their existence, «The white father told us: I think, therefore I am. The Black mother within each of us – the poet – whispers in our dreams: I feel, therefore I can be free. Poetry coins the language to express and charter this revolutionary demand, the implementation of that freedom»[4]. Let think of great poets like Maya Angelou, whose poems «often respond to matters like race and sex on a larger social and psychological scale»[5], or like Gwendolyn Brooks, whose poetry, especially the latest, is a political and civil poetry, taking as cultural reference heroes and subjects of the battle for liberation of black people (such as Winnie Mandela, wife to the anti-apartheid activist), but also like Margaret Walker who «through her work, she “[sang] a song for [her] people”, capturing their symbolic quest for liberation. When asked how she viewed her work, she responded, “The body of my work… springs from my interest in a historical point of view that is central to the development of black people as we approach the twenty first century”»[6].

1. Maya Angelou: I know why the caged bird sings

«The poignant beauty of Angelou’s writing enhances rather than masks the candid with which she addresses the racial crisis through which America was passing»[7]. That of Maya Angelou is a lively and melodic voice, her poems can talk even when there’s no human voice to give them sound, they have as mode,s the language of the intense, brave speeches of the great activist of the battle for black people’s rights like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. Angelou was able to bring together all temporal planes in her writing: both in her poetry and autobiographies, she managed to give voice to the last, to make it a new present, part of the hic te nunc of the existence in action and not anymore as something disappeared with time, but as something that is still here partly, that is still a being. A past that is personal, her life, her youth, her terrible traumas, the beauty of growing before as a girl than as a woman; a pat that is of her community, the troubled story of afroamericana and who that the lyrical I becomes a We, the collectivity becomes a person. The personal experience is thus an exemplum for the common one and becomes even global. The present meets the past, that of when a given poems was born, that of readers, of the poet, it’s the daily battle which becomes memory, it’s the journey to the self-determination in a place where is hostility but also the future, it’s the caged bird that sings and whose song is heard by the free birds, the future is a song overcoming its own time: «The caged bird sings/with a fearful trill/of things unknown/but longed for still/and his tune is heard/on the distant hill/for the caged bird/sings of freedom»[8]. “The caged bird”, dr, Maya Angelou’s favourite metaphor, taken from Paul Laurence Dunbar, famous afroamerican author, is a symbol for the inner freedom that wins ones the oppression of the external, is an eternal song that’s heard until now and if it’s clearly listened, one can hear the thousand of voice from the past and here we can find the beauty in Maya Angelou’s writing: the ability to speak through not one but a thousand of voices, voices of both the present and the past, giving relevance to the last ones, and consequently she was able to tell the future, to be understood by who’ll be after her.

2. Gwendolyn Brooks: writing poetry that will be meaningful

The poetic voice of Gwendolyn Brooks, the first afroamerican woman to win the Pulitzer Prize, is raw, bitter when the language gets filled with political and cultural meaning, when brings a message without forgetting the sweetness, the beauty of a poised, refined style. Worked, studied poems, perfect verse and rhymes, but also intense, hard, which don’t take away to be tough, to tell the truth on oppression, pain, on the battle to re-humanise her own identity in a culture where it was deprived of its otherness, of being an Other Ego, an Other Truth. This happens especially with the her most famous poem collection, In The Mecca, a turning point for Brooks’s poetics. «I want to write poems that will be non compromising. I don’t want to stop a concern with words doing good jobs, which has always been a concern of mine, but I want to write poems that will be meaningful […]»[9] and this was so. Brooks managed to delineate a world, give multiple meanings to the words she used, to the poems, to speak with the voice of her great gallery of characters. In her poems, there’s her Lyric I, but also her characters. Such a polyphony that only few, even among novelists, can make it in such little verbal marks. «The words, lines, and arrangements have been worked and worked and worked again into poised exactness: the unexpected apt metaphor, the mock-colloquial asides amid jewelled phrases, the half-ironic repetition – she knows it all»[10]. A poetry that can speak to its people, community, that hopes, fights for a future where Gwendolyn Brooks «[…] envisioned “the profound and frequent shaking of hands, which in Africa in so important. The shaking of hands in warmth and strength and union”»[11].

3. Margaret Walker: poetry as hope, poetry for the people

Margaret Walker’s poetics is the voice of a whole people, is culture that becomes creative work of a lonely person for the universality and becomes bringer of values. It’s the song of a choir, a choir for the last, of the story of slavery, of that community that still fights for the right to exist; it’s a choir that still sings and never stops to sing the lines of this wonderful poet.

One of the most loved and praised poem of Margaret Walker is “For My People”, which contains all the characteristics that made unique Walker’s poetry and it’s an excursus through the past and more recent history of US Black community, from the tragedy of slavery, to civil battles still fought nowadays in the heart of the New World; «poems in which the body and spirit of a great group of people are revealed with vigour and undeviating integrity»[12]. She uses as reference cultural elements of her community, recalls heroes, events that form that culture as vast as unheard by those who spit poison to not lose the position of privilege, and if this culture isn’t heard, then Margaret Walker addresses also to the deaf. She speaks to them as well, making universal a history that’s particular. Walker speak to everyone through her rhymes, she speaks to the humanity; her poetry talks about tragedies but is full of hope because she knows there will be always someone who still listen, fight, defend, doesn’t forget, «[…] the power of resilience presented in the poem is a hope Walker holds out not only to black people, but to all people […] “After all, it is the business of all writes to write about the human condition, and all humanity must be involved in both the writing and in the reading”»[13]

Viviana Rizzo

References

[1] LORDE, A., “Poetry Is Not a Luxury”, in Audre Lorde, Sister outsider, Trumansburg N.Y., Crossing Press, 1984, p. 371

[2] TODOROV, L’arte nella tempesta. L’avventura di poeti, scrittori e pittori nella Rivoluzione Russa, trans. ita. by Emanuele Lana, Milano, Garzanti S.r.l., 2017, p. 120 (iBooks)

[3] LORDE, A., “Poetry Is Not a Luxury”, in Audre Lorde, Sister outsider, p. 372

[4] Ibidem

[5] EDITORS, “Maya Angelou”, in Poetry Foundation, web, 2021, (https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/maya-angelou, retrieved on 24th February 2021)

[6] EDITORS, “Margaret Walker”, in Poetry Foundation, web, 2021 (https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/margaret-walker, retrieved on 24th February 2020).

[7] HOLST, W.A., “Review of A song Flung up to Heaven”, in Christian Century (giugno 2002), pp. 35-36, cit. in EDITORS, “Maya Angelou” in Poetry Foundation

[8] ANGELOU, M., The Complete Collected Poems of Maya Angelou, New Work, Random House Inc., 1994, p. 194

[9] EDI TORS, “Gwendolyn Brooks”, Poetry Foundation, web, 2021 (https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/gwendolyn-brooks consultato il 24 febbraio 2021)

[10] LITTLEJOHN, D., Black on White: A Critical Survey of Writing by American Negroes, New York, Grossman, 1966, p. 91, cit. in EDITORS, “Gwendolyn Brooks”, in Poetry Foundation

[11] EDITORS, “Gwendolyn Brooks”, in Poetry Foundation

[12] UNTERMEYER, L. “New Books in Review” in Yake Review, vol. XXXII, n. 2 (inverno 1934), p.371, cit. in EDITORS, “Margaret Walker”, in Poetry Foundation

[13] EDITORS, “Margaret Walker”, in Poetry Foundation

#Black women#literature#poetry as resistance#Maya Angelou#ethnicity#resistance#black history month#Margaret Walker#poetry#Black community#Gwendolyn Brooks#activism#people#Black people#battle for civil rights#black lives matter

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

A new world: a year of pandemic