Quote

Compassion as a spontaneous aspect of Self blew my mind, because I’d always assumed and learned that compassion was something you had to develop. There’s this idea—especially in some spiritual circles—that you have to build up the muscle of compassion over time, because it’s not inherent. Again, that’s the negative view on human nature at play.

To be clear, what I mean by compassion is the ability to be in Self with somebody when they’re really hurting and feel for them, but not be overwhelmed by their pain. You can only do that if you’ve done it within yourself. That is, if you can be with your own exiles without blending and being overwhelmed by them and instead show them compassion and help them, then you can do the same for someone in pain who’s sitting across from you.

Richard C. Schwartz, PhD, No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model

8 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Any approach that increases your inner drill sergeant's impulse to shame you into behaving (and make you feel like a failure if you can't) will do no better in internal families than it does in external ones in which parents adopt shaming tactics to control their children.

Richard C. Schwartz, PhD, No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Buddhist-derived practices of mindfulness are a step in the right direction. They enable the practitioner to observe thoughts and emotions from a distance and from a place of acceptance rather than fighting or ignoring them. For me, that's a good first step.

Mindfulness is not always pleasant, however. Researchers who interviewed experienced meditators found that substantial percentages of them had disturbing episodes that sometimes were long-lasting. The most common of those included emotions like fear, anxiety, paranoia, detachment, and reliving traumatic memories.

From the IFS point of view, the quieting of the mind associated with mindfulness happens when the parts of us usually running our lives (our egos) relax, which then allows parts we have tried to bury (exiles) to ascend, bringing with them the emotions, beliefs, and memories they carry (burdens) that got them locked away in the first place. Most of the mindfulness approaches I'm familiar with subscribe to the mono-mind paradigm and, consequently, view such episodes as the temporary emergence of troubling thoughts and emotions rather than as hurting parts that need to be listened to and loved.

Why would you want to converse with thoughts and emotions? They can't talk back, can they? Well, it turns out that they can. In fact, they have a lot of important things to tell us.

Richard C. Schwartz, PhD, No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

When you were young and experienced traumas or attachment injuries, you didn’t have enough body or mind to protect yourself. Your Self couldn’t protect your parts, so your parts lost trust in your Self as the inner leader. They may even have pushed your Self out of your body and took the hit themselves—they believed they had to take over and protect you and your other parts. But in trying to handle the emergency, they got stuck in that parentified place and carry intense burdens of responsibility and fear, like a parentified child in a family.

Richard C. Schwartz, PhD, No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model

16 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Well-known neuropsychiatrist Dan Siegel has emphasized the importance of such integration in healing and has described IFS as a good way to achieve that. He writes, “Health comes from integration. It’s that simple, and that important. A system that is integrated is in a flow of harmony. Just as in a choir, with each singer’s voice both differentiated from the other singers’ voices but also linked, harmony emerges with integration. What is important to note is that this linkage does not remove the differences, as in the notion of blending: instead it maintains these unique contributions as it links them together. Integration is more like a fruit salad than a smoothie.”

This, again, is one of the basic goals of IFS. Each part is honored for its unique qualities while also working in harmony with all the others.

Richard C. Schwartz, PhD, No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model

#dick schwartz#no bad parts#IFS#internal family systems#dan siegel#health#integration#systems theory

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

As I listened and learned, I became increasingly interested in disrupting the systems that label certain bodies as problematic or dangerous. As an outflowing of that, I wanted to find out how I had internalized those systems and body-stories and how I continued enacting them against myself and others.

Feeling restricted to only two options was a trope of myths about power and oppression that I was implicated in. I believed I had to choose between perfection or inaction, with no space in between. For all my trying, I am failing at this constantly. Often in public. And as messy as these public failings may be, they invite me to continue to learn, and they make me responsible to pull at the threads that are hard for me to see at first but that are creating real hurt for others.

Hillary L. McBride, PhD, The Wisdom Of Your Body

#hillary mcbride#The Wisdom of Your Body#body image#oppression#failing#learn#listen#perfectionism#unlearning

1 note

·

View note

Quote

I survived two successive car accidents, one of which more likely than not should have ended my life. Somehow, I lived. And have scars, visible and invisible, to remind me of something terrifying that happened outside my control. But I have chosen powerfully to refuse to let my inner dialogue contribute to the injuries that happened to me. I refuse to shame, punish, ignore, or discipline my body for telling the truth about what happened to me in those very scary moments, moments that somehow linger on in the present through pain and injury.

Hillary L. McBride, PhD, The Wisdom Of Your Body

#hillary mcbride#The Wisdom of Your Body#inner dialogue#survival#trauma#ptsd#self talk#self compassion

0 notes

Quote

I was standing there, hands tenderly on my face, like a mother would place her hands on the face of her beloved child. To the parts that were hurting, that had worked hard, had endured, survived, were afraid, I said aloud to all of me, “Well done. You have worked so hard. You have been in so much pain, so vocal about where it hurts. Thank you for speaking up. I am listening: And the doctors are listening too. Thank you for working so hard to protect me after such an awful and scary thing happened to you. You are safe now.”

It just tumbled out of me; perhaps it was all the practice no had doing this in the mirror before and after physiotherapy, late at night in bed, on the floor of my office, or every time got in a car after the accidents…

I pulled back the curtain, and there stood a nurse, motionless, with tears streaming down her face, hand over her mouth.

She said, almost with disbelief, that in thirty years of working in the imaging department of the hospital, never had she heard anyone speak out loud about themselves with such kindness.

I took a breath, lingering in that moment with her. We wondered together how much more difficult it is to heal when we are also contributing to our own pain by how we respond to ourselves about it. Her expression lives preciously tucked into my memory, a souvenir of the magic of that moment.

Hillary L. McBride, PhD, The Wisdom Of Your Body

#hillary mcbride#The Wisdom of Your Body#inner nurturer#self talk#IFS#parts work#self compassion#healing

1 note

·

View note

Text

Once we understand the pain cycle, we can identify the parts we can work with and do something about. This often starts with naming the second arrow using a skill called mindfulness...

Start by recognizing what your inner critic is saying about your body...

Imagine what you might say next time you notice the second arrow. You could start with, “Oh, there’s that second arrow,” or “Wow, this is hard to catch. I’m doing that thing again where I criticize myself.”

Learn to shift your attention by replacing your inner critic with something compassionate. Take a breath or shift your body into a more relaxed posture.

Hillary L. McBride, PhD, The Wisdom Of Your Body

#the pain cycle#chronic pain#hillary mcbride#The Wisdom of Your Body#inner critic#inner nurturer#mindfulness#second arrow

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Men feel pressure to perform a supposed ideal version of masculinity as described by the seven pillars of the man box: self-sufficiency, acting tough, attractiveness, rigid masculine gender roles, heterosexuality and homophobia, hypersexuality and sexual prowess, and aggression and control.

In this study, the men who had broken out of the box had rejected these masculine ideals and had decided to think more freely about what it means to be a man. But the men who were most "inside" the man box were those who had most internalized the seven pillars...

Specifically, those who were more inside the man box had lower levels of life satisfaction and self-confidence. They had poorer mental health, displayed less vulnerability and emotional connection in their friend and romantic relationships, demonstrated riskier behavior, had poorer body image, and were more likely to both perpetuate and experience bullying and harassment...

(Additionally, they) were far more likely to have symptoms of depression and suicidal thinking. They also felt unable to talk about their concerns with others, or they had no close friendships within which to talk vulnerably at all. Those inside the man box were also far more likely to have perpetrated sexual harassment or sexualized violence against a woman or a girl within a month of being interviewed for the survey.

Hillary L. McBride, PhD, The Wisdom Of Your Body

13 notes

·

View notes

Quote

If we have never been shown what is on the other side of feeling and all we know is that intensity is rising in our bodies, we will do whatever we can to get away from that sensation. This is where defenses come in.

A defense is a catchall category for anything we do to avoid our feelings... A defense is different from an otherwise acceptable activity because a defense is used to get away from what it feels like to be us or to avoid the emotion that is trying to get our attention. A defense isn't necessarily a bad thing; sometimes it's too much of a good thing, or sometimes we're using an otherwise good thing to get away from feeling something. Having a glass of wine to get away from our feelings is different from having a glass of wine because it complements the meal. The same is true of learning, laughter, and eating.

Although defenses keep us away from our emotions, they do serve a purpose: they protect us from emotional experiences that we feel unable to tolerate alone or experiences we feel scared to move toward; they also protect us from emotions that we hare been shamed or punished for feeling in the past.

Hillary L. McBride, PhD, The Wisdom Of Your Body

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Without the ability to move all the way through an emotion, we cannot get to what is on the other side: rest, presence, calm, connection, playfulness, and curiosity. This is what we call a "core state" or our openhearted, authentic, self-at-best state.

Just like emotions, it is available to us all, written into our biology, where we can access our confident, engaged, creative, and kind self. When we can be with emotions in our bodies (watching, tracking with sensation as it moves through us), emotions can release and move through us, allowing us to get back to our authentic self.

Hillary L. McBride, PhD, The Wisdom Of Your Body

#hillary mcbride#The Wisdom of Your Body#feelings#emotions#feel your feelings#DBT#IFS#self#core state

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Even now, we usually have trouble feeling emotions for a number of reasons:

We were discouraged from feeling through shame, punishment, rejection, isolation, or the sense that our feelings would overwhelm the person we were hoping would help us.

When we did feel, it was unbearable. We didn't know how to feel, how to soothe ourselves, or how to get through to the other side. Or we had to do it alone, but it was overwhelming and terrifying.

We learned that feeling wasn't allowed for our particular identity or context.

Regardless of the why, when we weren't supported to stay with our emotion, we failed to learn that emotions rise and then eventually fall, and that we will be on the other side of the feeling at some point...

Never being shown—consistently and frequently enough, if at all—how to ride the wave of an emotion can make it terrifying to start feeling because all we know is that the sensation in our body is rising, rising, rising with no end in sight. So, when we are faced with emotion moving in us, it can be overwhelming and shame inducing. This can keep us stuck in a loop that reinforces a shutdown, fear, or avoidance response.

Hillary L. McBride, PhD, The Wisdom Of Your Body

0 notes

Quote

While experiences, or the bottom-up way, are the most meaningful way to create lasting internal change, our brains tend to do more of what they have had lots of practice doing already. So giving our brains new things to practice can help, as can repairing the wounds that we acquired along the way by apologizing to ourselves. Sometimes I put my hand on my chest and say to myself, “I am so sorry I used to believe those harmful things.

There is so much more for me than to be stuck there again.”

Those of us who have struggled with body image have spent so much time focusing on what we don’t like or what we would change about our bodies that we have trained our brain to effortlessly notice those things. But to support our resistance and healing, we can also look for ways to connect with our bodies that incite gratitude and wonder.

Hillary L. McBride, PhD, The Wisdom Of Your Body

#hillary mcbride#the wisdom of your body#body image#body positivity#body neutrality#gratitude#wonder#mindfulness#core beliefs#cbt

1 note

·

View note

Quote

You might have heard someone say something like, "My head is saying one thing, but my gut is saying another." In other words, "What I know in the higher-order part of my brain has not trickled down into the lower, felt-sense part of my brain. There's a disconnect." When it comes to changing our sense of self and moving away from an over-fixation on appearance, the best way to get what we know about body positivity into our felt sense of ourselves is to have new experiences and to savor them...

When we are hyperaware of our outward appearance, our inner awareness often suffers. Learning to tune in to the inside of ourselves interoceptively (for example, noticing sensation in bladder, heart, stomach, and lungs), and practicing that regularly, has been shown to improve body image. Interoception is possible because of all the messages that run from our body to our spinal cord (through something called afferent nerves), up to our brain stem, and then into a region very deep within our brain called the insula. Interception is essential for creating the experience of balance and homeostasis, regulating emotion, having a sense of body ownership, and experiencing continuity as a person over time. When we have these experiences, we are training our attention to remember ourselves as more than an appearance, and we are less likely to try to manage our appearance as a means of creating agency in our lives.

(A) way to practice interception is by paying attention to when you are hungry, full, tired, or need to use the toilet... Try asking yourself next time you are hungry, "How do I know I'm hungry? How would I explain this to someone who had never felt hunger before? How do I know that I'm full? What is it like? What senses are telling me that I can stop eating?"

Even if body image is not your concern, practicing interoception is worthwhile. People who are able to notice their interoceptive cues and do so with a high degree of accuracy are better at completing complex cognitive tasks and using intuition for decision making. In contrast, people who have a low degree of awareness and accuracy around interoceptive cues are more likely to see their body as an object, and they are more likely to struggle with depression and eating disorders.

Hillary L. McBride, PhD, The Wisdom Of Your Body

0 notes

Text

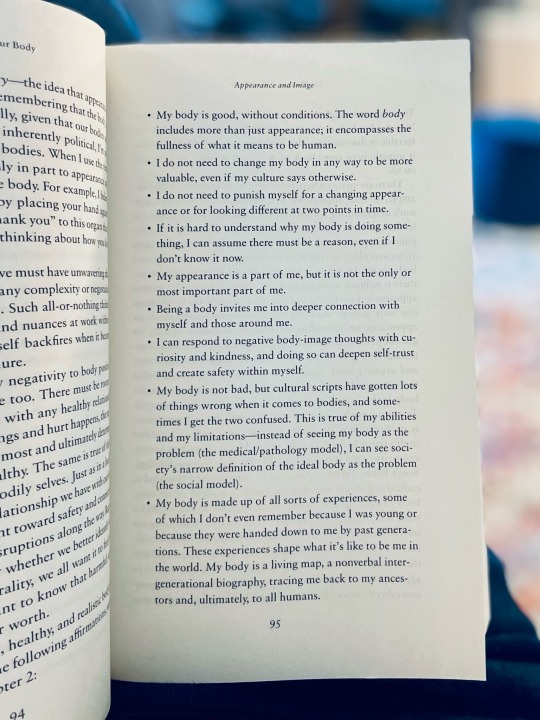

• My body is good, without conditions. The word body includes more than just appearance; it encompasses the fullness of what it means to be human.

• I do not need to change my body in any way to be more valuable, even if my culture says otherwise.

• I do not need to punish myself for a changing appearance or for looking different at two points in time.

• If it is hard to understand why my body is doing some-thing, I can assume there must be a reason, even if I o don't know it now.

• My appearance is a part of me, but it is not the only or most important part of me.

• Being a body invites me into deeper connection with myself and those around me.

• I can respond to negative body-image thoughts with curiosity and kindness, and doing so can deepen self-trust and create safety within myself.

• My body is not bad, but cultural scripts have gotten lots of things wrong when it comes to bodies, and sometimes I get the two confused. This is true of my abilities and my limitations--instead of seeing my body as the problem (the medical/pathology model), I can see society's narrow definition of the ideal body as the problem (the social model).

• My body is made up of all sorts of experiences, some of which I don't even remember because I was young or because they were handed down to me by past genera-tions. These experiences shape what it's like to be me in the world. My body is a living map, a nonverbal inter-generational biography, tracing me back to my ancestors and, ultimately, to all humans.

Hillary L. McBride, PhD, The Wisdom Of Your Body

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

While the staircase model can help us make sense of being human more broadly, the stress response itself remains unique to each of us depending on our life experiences. Whatever patterns we have used most in the past are the ones that form neurological grooves in our brain-body system. Just as water running over rocks changes the shape of the rocks, our thinking/behaving/responding changes our neurobiology, making it easier for our nervous system to instinctively take that pathway in the future. For example, if asking for help in the past has worked, it's going to be easier for us to take that social engagement step now than it would be if we had tried it in the past and were shamed or mocked, or we experienced even more violence or hurt as a result.

Hillary L. McBride, PhD, The Wisdom Of Your Body

6 notes

·

View notes