Text

An American Historian's Attempt to Explain the Backlash to Netflix's Cleopatra Documentary

Hi friends. I am going to do my best to do this with nuance, though I’m probably sending this into the void considering my dearth of followers. I might actually blaze this, we’ll see. Before I begin, my professional training in historical ethics is reminding me to disclaim that, while I have spent a not insignificant amount of time studying Egyptian history (especially the life and family of Cleopatra VII), I am not technically specialized in the classical period or Egyptology. That being said, I do have years of training in the academic field and am currently getting my PhD in history. I'm gonna try to link sources easily available to the public, but a lot of the nuance of academic scholarship is unfortunately stuck in academic journals and published books.

Anyway, I’ll get into it:

Before discussing the Ptolemies, Cleopatra, Egypt, or modern concepts of race, I first want to address the concept of historical identity in the global black diaspora. One of the things that interests people the most in history is their own ancestry. The majority of people in the world can claim a piece of history as their own because they identify as descendants of a specific culture, civilization, or country. (I, for instance, can claim knowledge of my Irish, Finnish, English, and German ancestry by pointing at names in the family tree). However, for the majority of the black diaspora, especially in the Americas, that is something entirely unavailable. When the ancestors of black Americans were stolen or captured and then transported and sold across the Atlantic, it was not just people that were taken, but historical and cultural connections. And the taking did not end at the first auction block. Families were routinely separated for centuries before abolition finally toppled North and South American and Caribbean slave economies one by one. Cultural and historical knowledge is nearly impossible to preserve in that industrialized dehumanization. Black Americans, from the North to the South Atlantic, lack access to their own history - and that is incredibly isolating.

So, understandably, members of the black diaspora have - with their recent increased access to education (as a historian the term "recent" goes back much farther than most people think qualifies) - gone in search of their stolen history. They have every right to do this, but it can be difficult considering the lack of scholarship on African history outside of the continent and the expense and limitations of Eurocentric genetic tests like 23&me. There is also the issue that most people look to their personal history as a source of pride (I, personally, am very happy to inform people that my family left Germany before either of the World Wars... leaving out the fact that that side of the family is now mostly made up of right-wing religious extremists). And the problem with African history is that most of it has traditionally been considered by the Western world to not be particularly significant - with the singular exception of Egypt. If you ask any Westerner, regardless of race, to name the most important or definitive civilization in African history, a good 98% would hands-down say Egypt. No contest.

But that is the type of question that you could only ask about Africa. If you went up to someone in the United States, for instance, and asked them what the most important civilization in Europe was, or Asia, you would either entirely stump them, start a fist-fight, or get an answer like: "there isn't one." There is a myth perpetuated in the Western world (outside of current post-secondary historical academia) that Egypt is the only remarkable African civilization - or that they are the only historical nation on the continent that could be described as a "civilization." This is false and a hold-over from the white, Western dominance of academic history. It is a blatant, racist dismissal of great African kingdoms like Nubia, Carthage, Mali, Benin, Great Zimbabwe, and many others. But because of the strength of the myth, many in the black diaspora seeking their own history look to Egypt. And because they want pride in their history - something they have every right to - they want to claim Egypt as theirs - which is something they do not.

During the Atlantic slave trade Egypt was under the control of the Ottoman empire, not Europe. So while a certain form of slavery was practiced in Egypt at the time (though not the chattel slavery familiar to the Americas), they were not a part of the diaspora. European slave merchants were not shipping slaves out of Egypt, they were shipping them out from the coast of north and central West Africa. So claiming to be Egyptian as a descendant of West Africa would be comparable to claiming to be French or Spanish if your family descended from Scandinavians. You can imagine that the French would be pissed if a bunch of Swedes tried to claim Joan of Arc or Marie Antoinette as one of their own. Modern Egyptians are similar, especially because Egypt can just as accurately be described as a Mediterranean or even Middle Eastern civilization. Members of the black diaspora, for quite some time, have only been able to describe themselves specifically and solely as "black." Egyptians do not do this because of their incredibly long and nuanced history.

Okay, with all that in the air let's move on to the Ptolemies:

In the 330s BCE Alexander the Great conquered Egypt from the Achaemenid Persians and the native Egyptians welcomed him as a liberator. Egyptian religious leaders proclaimed him to be the son of Amun and he was crowned as Pharaoh, founded the royal city of Alexandria in the Nile Delta, and then immediately left to keep fighting the Persians. When he died he essentially nuked his new empire because he was a childish bitch (don't get me started on Alex, I think you can tell he's not my fav) and his generals scrambled to each claim a piece of the pie. One of the most desirable regions was Egypt, which was taken by Alexander's general Ptolemy who kidnapped Alexander's dead body (lol) while it was on its way to Greece and instead buried it in Egypt to legitimize himself as Alexander's heir - and it worked. The Ptolemies ruled Egypt for almost three centuries.

Now the Ptolemies were fucking fascinating. They are called the Ptolemies or the Ptolemaic dynasty because every. single. male. in the family was named Ptolemy. No matter how many there were. This led to some confusing situations like the joint rule of Ptolemy the 6th and the 8th. The women of the family rotated through three names: Arsinoë, Bereníkē, and Cleopatra, meaning that the famous Cleopatra every knows and argues about was actually Cleopatra the 7th. The Ptolemies were also unique specifically because they ruled as a joint pair: king and queen. The queens didn't have the same level of power as their male counterparts, but male pharaohs based a certain level of their legitimacy on having their queen by their sides.

What is important to know about the Ptolemies is that they were soooo Greek. Specifically Macedonian Greek. The founder, Ptolemy Soter, was full on Greek and so were his wife and his kids. But it doesn't stop there because the Ptolemies wanted to keep all their power in the family... which means they all married each other. Brother to sister, occasionally uncle to niece. Gross? Absolutely. Politically savvy? Probably not. It worked for a good while, though, except for the fact that it encouraged "family rivalry" to the ultimate extreme. The Ptolemies were famous for their incest and their love of murder. Specifically the murder of each other. So, while they stayed Very Greek throughout the centuries, they did their own family-tree-pruning. This inevitably led to all the legitimate heirs just straight up eliminating each other entirely in the early first century BCE, leading to a bit of a succession crisis that ended with the ascent of Ptolemy the 12th to the throne. Ptolemy the 12th was the father of our Cleopatra (the 7th) and was also - significantly - illegitimate. We have no clue who his mother was. We are also not entirely sure who Cleopatra the 7th's mother was, though the most likely candidate is another Ptolemy (specifically Cleopatra the 5th). Cleopatra the 7th (whom I will now just call Cleopatra) succeeded her father to rule jointly with her brother-husband Ptolemy the 13th and later Ptolemy the 14th. She also actively competed with her sister Arsinoë the 4th. Eventually all but Cleopatra ended up dead, with our remaining queen likely having some level of involvement in all of their deaths.

So what does this all mean? Especially for Cleopatra? Well, it means that the only thing we can say is that she was anywhere from 25%-100% Greek. We don't have a definitive number and, unless we find her mummy in a decent enough state for DNA testing (which is highly unlikely at this point), we'll never have one. But, if we're considering modern concepts of race and allow for the potential of native Egyptian ancestry, the most Cleopatra could be considered is mixed race. Specifically: mixed Greek and native Egyptian. Now, Egypt is in Africa and Egyptians are Africans, but they are Mediterranean North Africans, meaning they are generally light-skinned and consider themselves to be particularly cosmopolitan. They do not see themselves as representatives of an entire continent - they are an independent country with their own history.

But before we get into modern discussions of race I want to talk about contemporary ethnic and national identities. Because our modern concept of race and ethnicity is relatively young (in comparison to Cleopatra) and is a direct result of the past 4-5 centuries of colonialism, imperialism, and a certain level of corruption of science. Cleopatra's family was Macedonian Greek. They also ruled Egypt as Pharaohs. This existed simultaneously. Cleopatra was Greek, proudly, but she was also Egyptian - not because of the color of her skin, but because she was the Queen of Egypt. The Ptolemies were Greek, but they were recognized as legitimate Egyptian rulers because they did everything Pharaohs were supposed to do. Cleopatra was perhaps the best of them. She participated in religious ceremonies, build temples, protected her kingdom from the Roman Empire for over two decades, and headed the cult of the goddess Isis. When she died, Egyptian religious leaders pleaded with the Romans to allow them to bury her in Egypt. Why? Because if a Pharaoh is buried outside of Egypt then they cannot protect Egypt in the afterlife. Regardless of the color of her skin, regardless of the fact that she was Greek, her people, her allies, her enemies (see Plutarch's Life of Antony), and her peers considered her to be Egyptian because she was the queen of Egypt. Egyptian historians today also recognize her this way. And as an Egyptian Cleopatra was also undeniably African, but she was not the queen of all of Africa. She was the queen of Egypt. (If you are interested in how she was represented in her own time and how that evolved to today I would recommend this book, this book, or this one, all of which you can probably request through your public library).

So why all the fuss? Many people point out that Cleopatra has been portrayed by many different actresses over the decades in Hollywood with little protest from Egyptians or their historians, why this documentary series? The answer is in the question itself: it is a documentary series. Historical fiction, even in the realm of Hollywood biopics, is allowed a certain amount of artistic license. Because in the end movies and TV shows are narratives. A documentary, however, is held to a different standard. Documentaries are supposed to explore the truth for a public, non-academic audience. We as historians hold ourselves to an incredibly high level of expectation when it comes to historical objectivity. That means that it is our job not only to explain history, but to defend it. That means teaching about the horrors of slavery in the Americas to Americans, no matter how shameful and uncomfortable it is. That means teaching the horrors of the Holocaust to Germans for similar reasons. That means that, when someone goes beyond exploring historical ideas and starts claiming historical facts as their own when they belong to someone else, telling them that they are wrong. Yes, Cleopatra was African - in potentially both the modern and historical contemporary senses - but claiming that she looks like and is similar to descendants of people from, for instance, the Congo is not factually correct. Having a white British-American like Elizabeth Taylor play Cleopatra is also not factually correct, but Mankiewicz's Cleopatra was a historical drama film, not a documentary - it has more wiggle-room.

Which brings me specifically to Netflix's documentary trailer. It describes Cleopatra as a warrior queen in an era of female power - which is just not true. It attempts to portray her as a feminist and a #girlboss, which is one of the things that made my blood boil the most. Cleopatra was a fascinating and amazing woman, but she wasn't a modern feminist because she existed over 2000 years ago. But that doesn't make her a bad woman, because there is no wrong way to be a woman. The trailer also implies that she has some sort of power to hold over Rome, which is also not true. Cleopatra was amazing because of her ability to keep Egypt independent for so long in spite of Rome. And then there is the phrase that probably got all the Egyptian historians (and the non-Egyptian ones) truly up in arms. One of the experts being interviewed (who the trailer doesn't name, but I've found out is Africana Studies Professor Shelley P. Haley at Hamilton College in New York) says that her grandmother told her that “I don’t care what they tell you in school, Cleopatra was Black.” This is not just a claiming of Cleopatra by the black diaspora as specifically one of their own, but is a direct dismissal of the entire field of academic history. Yes, it is one phrase, but actively challenging what children are told "in school" as incorrect or fake is a huge problem today, especially in the United States. The sowing of anti-intellectualism by people who are themselves intellectuals is insidious and potentially even worse than attacks against academia by the popular news media.

So what's the issue with exploring Cleopatra as an African queen? None, really. The issue is taking her out of her Egyptian context, away from the identity of an entire nation of African people, and making her into an icon of the black diaspora and the entire African continent. It takes away from modern Egyptians and also is somewhat insulting to female leaders from the rest of the continent's history by making them less "iconic" in comparison. Queen Elizabeth the First was not the queen of Hungary. Does that make her less of a powerful female leader? No. But it does make her not Hungarian. Is she European? Absolutely. Does that make her an icon of all of Europe, or the most important one? No. Cleopatra is the same. She is fascinating. She was Greek. She was Egyptian. She was African. Was she the ancestor or the queen of the ancestors of slaves taken to America? No. But does that mean that members of the black diaspora have no history, no queens? Also no. They are out there. Yes, they have traditionally been neglected, which is racist and a problem. Yes, there is less documentary evidence about them because they did not have the pencil-pushing Romans writing about them all the time and more often maintained an oral tradition to preserve their history. The solution is not to erase borders and definitions. the solution is to provide better funding for the historical field, for translations, for international research, and for diversifying historians themselves. Black history has become increasingly relevant recently because more black people have been able to access post-secondary education. But we are nowhere near done. So here I will beg that instead of rejecting history that you don't like - whether for its incompleteness or lack of relatability - don't blame historians. Become one. Because we need you.

Thanks for reading.

#“race” for people is a slur in Greek hence the quotes#A bit of a generalising addition but it's important to not center only North American and NW experiences when it comes to foreign figures#<<< prev tags#Cleopatra#Queen Cleopatra (2023)#Netflix#reblog

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, you probably don’t remember but if you do could you please tell me how you got the seventh cg (second page, bottom left) in pre Odyssey

Thank you

Uhhh it's been long since I've played it tbh. The best way to get all is to keep multiple saves and try all options that there are. Usually those extra CG's are obtained by picking dialogues that don't change the course of the game much, and are just different ways of achieving the same ending.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Always enjoy your posts about mythology and history in general I guess

I doubt I do much history. I do reblog stuff from others, for obvious reasons, but me myself? I haven't put much depth in it.

0 notes

Text

Airport security: No liquids on the plane.

Odysseus: Ok *starts drinking it*

Airport security: people usually just throw away the shampoo, sir.

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

Young Greeks sing outside the police station where another femicide took place.

143 notes

·

View notes

Note

Challenge for authors to stop making retellings where their female characters get abused and assaulted...

Just saying 😂 (miller, Jennifer etc.)

Another issue with this is that, they most likely wouldn't engage as much attention as they have if it hadn't the "Greek Mythology" tag on them. Because removing the names of the 'characters' and putting on random ones results in a very generic wattpad fanfiction.

People simply don't believe anyone considered 'female' in the Ancient world can be happy, and it's mostly shown with Greek Folklore because it's Europe and Europe can be played with as much as they want. Funny how they will jump at you if you say anything bad about any other folklore that isn't Greek. Idk.

0 notes

Text

Things I look for in history books:

🟩 Green flags - probably solid 🟩

Has the book been published recently? Old books can still be useful, but it's good to have more current scholarship when you can.

The author is either a historian (usually a professor somewhere), or in a closely related field. Or if not, they clearly state that they are not a historian, and encourage you to check out more scholarly sources as well.

The author cites their sources often. Not just in the bibliography, I mean footnotes/endnotes at least a few times per page, so you can tell where specific ideas came from. (Introductions and conclusions don't need so many citations.)

They include both ancient and recent sources.

They talk about archaeology, coins and other physical items, not just book sources.

They talk about the gaps in our knowledge, and where historians disagree.

They talk about how historians' views have evolved over time. Including biases like sexism, Eurocentrism, biased source materials, and how each generation's current events influenced their views of history.

The author clearly distinguishes between what's in the historical record, versus what the author thinks or speculates. You should be able to tell what's evidence, and what's just their opinion.

(I personally like authors who are opinionated, and self-aware enough to acknowledge when they're being biased, more than those who try to be perfectly objective. The book is usually more fun that way. But that's just my personal taste.)

Extra special green flag if the author talks about scholars who disagree with their perspective and shows the reader where they can read those other viewpoints.

There's a "further reading" section where they recommend books and articles to learn more.

🟨 Yellow flags - be cautious, and check the book against more reliable ones 🟨

No citations or references, or references only listed at the end of a chapter or book.

The author is not a historian, classicist or in a related field, and does not make this clear in the text.

When you look up the book, you don't find any other historians recommending or citing it, and it's not because the book is very new.

Ancient sources like Suetonius are taken at face value, without considering those sources' bias or historical context.

You spot errors the author or editor really should've caught.

🟥 Red flags - beware of propaganda or bullshit 🟥

The author has a politically charged career (e.g. controversial radio host, politician or activist) and historical figures in the book seem to fit the same political paradigm the author uses for current events.

Most historians think the book is crap.

Historical figures portrayed as entirely heroic or villainous.

Historical peoples are portrayed as generally stupid, dirty, or uncaring.

The author romanticizes history or argues there has been a "cultural decline" since then. Author may seem weirdly angry or bitter about modern culture considering that this is supposed to be a history book.

The author treats "moral decline" or "degeneracy" as actual cultural forces that shape history. These and the previous point are often reactionary dogwhistles.

The author attributes complex problems to a single bad group of people. This, too, is often a cover for conspiracy theories, xenophobia, antisemitism, or other reactionary thinking. It can happen with both left-wing and right-wing authors. Real history is the product of many interacting forces, even random chance.

The author attempts to justify awful things like genocide, imperialism, slavery, or rape. Explaining why they happened is fine, but trying to present them as good or "not that bad" is a problem.

Stereotypes for an entire nation or culture's personality and values. While some generalizations may be unavoidable when you have limited space to explain something, groups of people should not be treated as monoliths.

The author seems to project modern politics onto much earlier eras. Sometimes, mentioning a few similarities can help illustrate a point, but the author should also point out the limits of those parallels. Assigning historical figures to modern political ideologies is usually misleading, and at worst, it can be outright propaganda.

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. "Big theory" books like Guns, Germs and Steel often resort to cherry-picking and making errors because it's incredibly hard for one author to understand all the relevant evidence. Others, like 1421, may attempt to overturn the historical consensus but end up misusing some very sparse or ambiguous data. Look up historians' reviews to see if there's anything in books like this, or if they've been discredited.

There are severe factual errors like Roman emperors being placed out of order, Cleopatra building the pyramids, or an army winning a battle it actually lost.

When in doubt, my favorite trick is to try to read two books on the same subject, by two authors with different views. By comparing where they agree and disagree, you can more easily overcome their biases, and get a fuller picture.

(Disclaimer - I'm not a historian or literary analyst; these are just my personal rules of thumb. But I figured they might be handy for others trying to evaluate books. Feel free to add points you think I missed or got wrong.)

921 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why are you following me?

Put a reason in my ask.

309K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hera: A boy doesn't dye his hair that color unless he has psychological problems!!

Dionysus: My hair color has nothing to do with my psychological problems!!!!

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

"in the original myth medusa was actually -" "well in the homeric version, achilles wasn't -" "no but in the real myth -"

read what you have just written. in the myth. myth.

these were not real people. myths change and shape to their contemporary situations with every retelling. whoever was telling or writing the myth put in or took out something different and new every time it was told. "accurate myths" are not a thing, I'm sorry. 'accurate to homer's version'? sure, go nuts. but they were never histories, and modern adaptations are not wrong for being different.

914 notes

·

View notes

Text

"in the original myth medusa was actually -" "well in the homeric version, achilles wasn't -" "no but in the real myth -"

read what you have just written. in the myth. myth.

these were not real people. myths change and shape to their contemporary situations with every retelling. whoever was telling or writing the myth put in or took out something different and new every time it was told. "accurate myths" are not a thing, I'm sorry. 'accurate to homer's version'? sure, go nuts. but they were never histories, and modern adaptations are not wrong for being different.

914 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry if my question was uncomfortable, but I'm a foreigner and would like to understand more about the "feud" between Greece and North Macedonia. I've seen (heated) discussions between Greeks and Macedonians about culture, but I don't know much about the context. Again, sorry if the question is uncomfortable or insensitive.

I think this Geography Now! video does a good job of explaining the controversy. Basically, the Greek position is that since Slavs came a thousand years after Alexander in the area, and the culture and language of North Macedonians are largely Slavic it’s illogical for them to name their country after a Hellenistic kingdom and claim many Greek figures, and also Alexander the Great, as people from their culture.

For clarification, Alexander the Great was certainly Greek and he spoke the Macedonian dialect of Greek which was Doric (for reference the Spartans also spoke the Doric dialect). When North Macedonians say “he was Macedonian” they mean he was from their culture and he spoke their language, and he wasn’t Greek.

North Macedonian history tends to confuse the administrative regions with culture and ethnicity because it’s convenient to them. It doesn’t matter if Kyrillos and Methodios were two Greek brothers from Thessaloniki. To N. Macedonians, because these two brothers were in a region that was occasionally the administrative region of Macedonia, they were “Macedonians”, hence “from North Macedonia”. To them it doesn’t matter that Alexander’s birthplace and all important cities of the Hellenistic Macedonian Kingdom are in Greece.

What is crucial to understand about this controversy is that Macedonia for a long, long time, was basically “a geographical region of many mountains”. The Greek word Μακεδονία literally means “Mountainous Region”, and because it’s kind of a distinct region it was a district on its own many times. That’s an approximation of the limits of “Macedonia” as a geographical region with distinct characteristics.

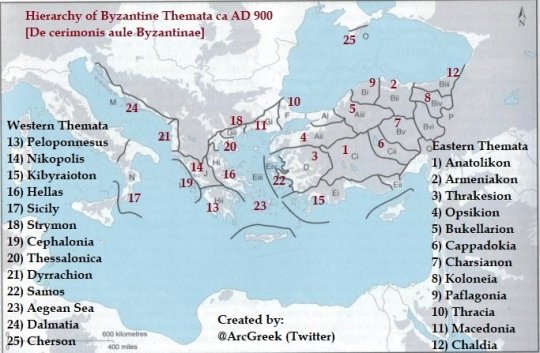

Below is the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia. However, the people who are now residents of N. Macedonia won’t be here for another thousand years!

The guy in the video says the Macedonian kingdom expanded, but then he doesn’t say that it was separated into more kingdoms for better governance, and one of those kingdoms was this controversial region (in Green) which is now part of Greece and North Macedonia. (Slavs were still not in the area)

When Romans conquered these kingdoms they also separated the area into administrative regions. The province of Macedonia within the Roman Empire, circa 125 (Slavs were still not in the area):

Later administrative departments of Roman empire (Slavs were still not in the area). In fact, “Provincia Macedoniae” changed almost at the time the Slavs arrived, in the 7th century.

Within the Eastern Roman Empire there was later separation into Themata, but now the department of Macedonia was moved to the West, occasionally including parts of the region where N. Macedonia is today. (Slavs in the area after 7th c. ACE)

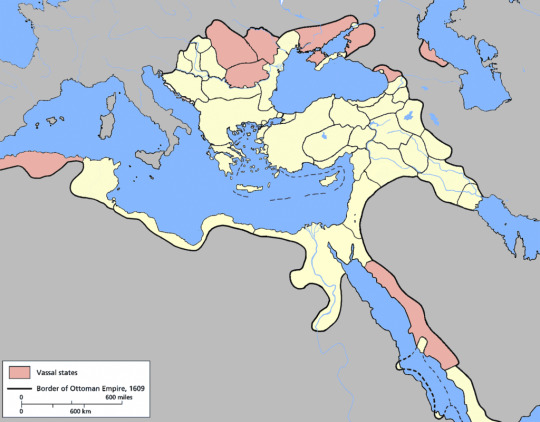

Theeeen came the Turks, and separated the regions differently. Now everyone, Turks, Greeks, Slavs, Hebrews and whoever else lived in that region, are all part of the same “millet”, the Rum Millet. “Macedonia” wasn’t an administrative area then.

In the 19th century, Turks and Slavs were the majority in the region of Macedonia, with Greeks coming third population-wise, and Hebrews also having very large communities.

(Greeks might not like this fact, or they may ignore it completely, but if you open actual historical books and maps, you’ll see the demographics. We have censuses from that era. I learned the old Slavic and Turkic names that villages and places in my region had. There’s also a reason Kemal Ataturk’s mother wrote to him “They took our Salonik” when Greeks reclaimed the city after 600 years. We can still love our country and appreciate our history, without erasing parts of it.)

In 1912, the largest part of the region of Macedonia was claimed by Greeks. In time more Greeks came to it as immigrants from Anatolia and other Greek regions, shifting the population in such a way that Greeks were now the majority. (North Macedonia still doesn’t exist as a country)

In 1991, when the country of North Macedonia was created, Greece already had an administrative region of Macedonia which covered most of the Macedonian geographical area, also the ancient Greek cities of the kingdom, and the emblem of Greek Macedonia was the ancient Greek Macedonian star. The Vergina Star, and the ancient Greek city of Vergina is also in Greek ground today. (Our Emblem and Flag)

So you can imagine it came as a shock to Greeks when a newly founded country used not only their symbols, but also distinctly Greek symbols. People who are now residents of N. Macedonia lived in the geographical region that a few centuries ago was also “Macedonia” in the administrative sense, so I get where they’re coming from. However, when culture gets appropriated, when the culture of important ethnically Greek figures is erased, when Greek words are claimed to be “Macedonian” all of a sudden since 1991, things get tense.

It’s a political matter, as the video says. People from the two countries usually have normal interactions if the matter doesn’t come up. And I don’t think there’s hate between the simple people.

#i recently had to discuss about it#all i can say is that it didn't end well. since i wasn't “on their side” according to them#the EU having more importance than Greece in this matter really says it all :(#Greek history#Ottoman history#the Macedonia discourse#<<< oh. boy.#greece#macedonia#reblog

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aphrodite: I could fix him.

Dionysus: Good for you, I guess. I could be the only thing he's truly afraid of.

#.....hey#hi tumblr. i am. in fact. alive.#i've been going through it. and i still am. it'll be for a while.#i'll return with some essay suggestions when i'm done with my shenanigans. yay.#dionysus#aphrodite#incorrect quotes

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

My favorite scene in this entire thing tho, has to be the golden apple incident, just because of how Zeus passes over the judgement to someone else (before it got passed over to Paris)

348 notes

·

View notes

Text

*insecure*

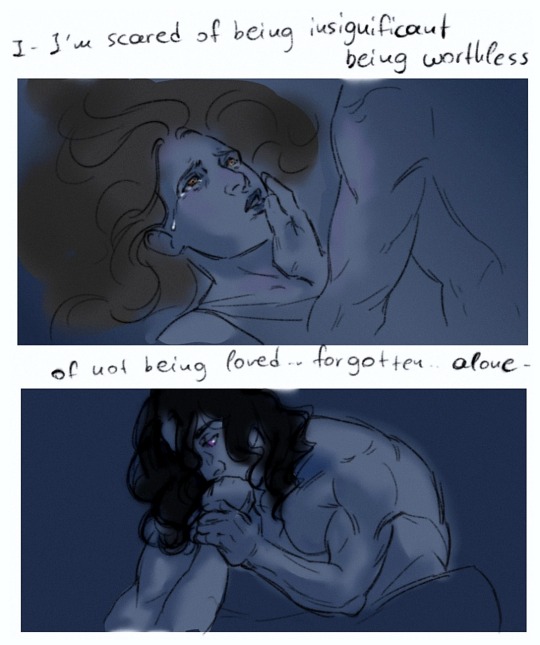

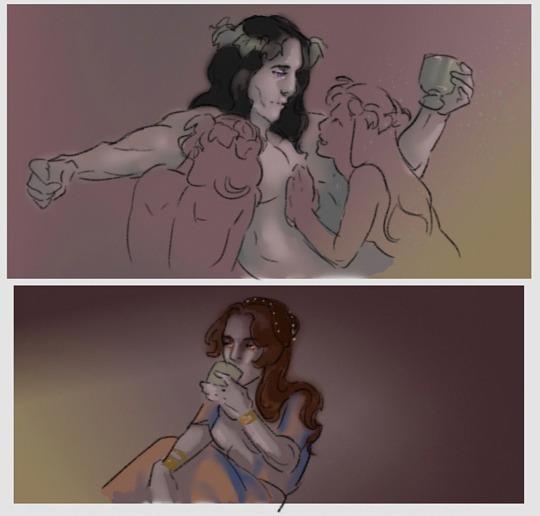

Ariadne would never admit of being jealous or insecure but her feelings would get the best of her. I think her life in Crete shaped her opinions on marriage and life and since ber parents had a rocky one, she feared of having one like them.

To her Dionysus is perfect, even with his wild nature so it's not wonder many men and women alike are drawn to him. But she often compares herself or fears of him cheating. But he realises when she feels down. He never misses the difference in her moods and knows how to make her open up to him.

And actions speak louder then words and he intents to prove his love to her no matter how many times it takes.

345 notes

·

View notes