Photo

Venetian School c. 1640, follower of Francesco Montemezzano, Portrait of a Lady in a Pointed Hat, oil on canvas, 74.5 x 58 cm/29.33 x 22.83 in.

The tall hat’s pearls, precious stones and see-through veils suggest that the sitter may be an Ottoman ruler’s most famous wife: Roxelane (c. 1500-1558). Born in Ruthenia, in present-day Ukraine, she was enslaved to Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent before becoming his first wife and, according to some chroniclers, playing a key role in his political decisions. [source]

135 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day in Ottoman history, Seniha Sultan was born to Sultan Abdülmecid I and Nalandil Hanımefendi:

“Princess Seniha used to wear dresses of the most superb cloth, with her tiara on her head on formal occasions, and she also wore gowns with long trains in the European fashion spreading out behind her. She had a regal look about her. Her face was pretty. She had her hair cut like a man’s and never let it grow out. In manner she was entirely unconstrained. Often would she burst into laughter, and she spoke rapidly and in a deep voice. Princess Seniha was not particularly welcome at the palace because some of her gestures were a bit too indecorous.” – Ayşe Osmanoğlu translated in English in Douglas Scott Brookes - The Concubine, the Princess, and the Teacher: Voices from the Ottoman Harem

313 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day in Ottoman history - 19 June - Fatma sultan was born:

Fatma Sultan was the elder daughter of Murad V and his Senior Ikbal, Resan Hanım. She was born on 19 June 1879, three years into her father’s confinement inside Çırağan Palace, and was named after her father’s favourite sister. Fatma was described by one of her father’s concubines as “calm, dignified, serious-minded, polite, and gentle.” She spent most of her childhood reading books in French and playing the piano.

On 29 July 1907, Fatma Sultan married Karacehennem-zade Dâmâd Refik (Iriş) Beyefendi, a diplomat and son of the governor and senator of Konya. With him, she had five children, three of whom reached adulthood: Sultân-zâde Mehmed ’ÂIî Beyefendi (4.1908 - 22.11.1911), twins Sultân-zâde Mehmed ‘Alî Beyefendi (20.1.1909 - 1981) and 'Ayşe Hadîce Hanım-Sultân “iris” (20.1.1909 - 14.10.1968), Sultân-zâde Mehmed Murâd Beyefendi (8.1910-1.1911), and Sultân-zâde Celâleddîn İris Beyefendi (1916 - 1997)

Fatma Sultan inherited her mother’s jewel but never wore them. She lived frugally and like an ordinary citizen of Istanbul, even going out herself for the shopping. She was particularly devoted to her husband.

In 1924, the family moved to Sofia, Bulgaria, after the Republic of Turkey was announced. It was there, on 20 November 1932 that Fatma Sultan died and was afterwards buried.

sources: Douglas Scott Brookes - The Concubine, the Princess, and the Teacher: Stories from the Ottoman Harem, M. Çağatay Uluçay - Padişahların Kadınları ve Kızları, Yılmaz Öztuna - Devletler ve Hanedanlar, Necdet Sakaoğlu - Bu Mülkün Kadın Sultanları, Geneaolgy of the Ottoman Imperial Family (2005)

140 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Gülcemal Kadınefendi was the only Bosnian consort of Sultan Abdülmecid. She was most probably born in Sarajevo in 1826 and entered palace service when she was young with her sister Bimisal Hanım. Abdülmecid I was immediately fascinated with her beauty and married her in 1840; in the same year she gave birth to her first child, Fatma Sultan. In 1842 she gave birth to Refia Sultan and a year later, in 1843, to Şehzade Mehmed Reşad (the future Mehmed V Reşad). She was said to be delicate and sensitive. The Austrian doctor Spitzer said about her: ”… the sultan personally opened the shawl on her face and that’s when I saw the most beautiful woman’s face I had seen in my life…“ She caught tuberculosis, and the sultan was desperate to save her: ”… I have had the most genuine conversations with this woman. Since I was a youth, I have loved her with my all heart..“, he told Chief Physician İsmail Paşa. Gülcemal Kadınefendi passed away in […] November 1851 at Ortaköy Palace and was buried in the New Mosque.” – from Harun Açba, Kadınefendiler

*Gözde Kaya as Gülcemal

358 notes

·

View notes

Photo

VALIDE SULTANS: “This much-favored and esteemed consort of Sultan Mecid was a gracious and charming lady of medium height, slightly plump, with black eyes and black eyebrows. When all was quiet she was most gentle, but when things were in an uproar she would change on the spot, pulling no punches to defend what she saw as her legitimate rights and position. She wasn’t especially brilliant; in fact she was so simple as to be incapable of cunning. But she was easily influenced, which is why a woman as intriguing and deceitful as Nakşifend Kalfa, who could fool the devil himself into putting his sandals on backwards, was able to drag the Lady Mother into a number of intrigues that she launched on behalf of our master, both while he was Heir and after his confinement in Çırağan. The great weakness of the Lady Mother Şevkefza was the deep devotion she nurtured toward her son. If she had had to sacrifice her life in order to restore the throne to her son, whom she loved madly, she would not for a moment have shrunk from doing so. But she lacked the ability to cook up plans for such an event and bring them to fruition.” – Douglas Scott Brookes - The Concubine, the Princess, and the Teacher: Voices from the Ottoman Harem // Şefika Tolun as Şevkefza

715 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The Queen mother is growing in authority with the Sultan every day, for which one often sees of being with His Majesty, and the Pashas and other grandees who refer to her in all the things that they want from the Sultan. But she became aware and was instructed of the evil of the Former Queen [mother] that she went embracing the favor little by little in order to establish herself greatly and did not hear well of being new in this concept, because of the tender age of the Sultan, but one believes that one could be successful as any, and perhaps superior to the other.” — Ottaviano Bon, December 1604

277 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On November 9th, 1605, Handan Valide Sultan died:

Until her death, Handan Sultan also took an active part in the management of governmental affairs. Unlike contemporary Ottoman sources, which hardly mention Handan Sultan before her death, the Venetian bailo’s reports often describe her political actions in some detail. For instance, some of Contarini’s reports indicate that Handan maintained a close relationship with Ali Pasha, especially during the first critical months of Ahmed’s sultanate. According to the report dated February 3, 1604, for example, she summoned him to her harem quarters at midnight to discuss current affairs at length. At this secret meeting, Handan Sultan stood behind shutters while Ahmed spoke to the grand vizier face-to-face. As Contarini notes, this was an unprecedented arrangement that touched off a scandal in court circles. Such close contact strongly suggests that Ali Pasha was in fact Handan’s client. — Günhan Börekçi, A Queen Mother at Work - On Handan Sultan and Her Regency during the Early Reign of Ahmed I

226 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(OTTOMAN) WOMEN’S HISTORY MEME | 5 valide sultans: Emetullah Rabîa Gülnûş

“… limiting the influence of the valide sultans on the workings of the imperial court and Ottoman internal and international politics to the era of "the sultanate of women” does injustice to historical reality. Shared patterns tied Gülnûş’s career to a tradition of queen mothers that had existed since antiquity, thus well before the Ottoman period itself. The women sought to promote their own interests and those of their sons, but also devoted themselves to the maintenance of order and the well-being of dynasty and empire. In the case of Gülnûş Sultan, much of her activity served the best interests of the Ottoman sultan and the state as a whole. Her advisory, mediatory, and negotiating activity at the imperial court, and her investments, both in the army and charitable works, contributed to the prestige of the dynasty as well as the public good. Her comment during the 1703 revolt—"if fighting breaks out within the ummah of Muhammad, neither I nor you will remain"—reflects a recognition on her part of the relationship of public attitudes, the fortunes of the dynasty, and her own standing at court.“ — Betul Ipsirli Argit, A Queen Mother and the Ottoman Imperial Harem: Rabia Gülnuş Emetullah Valide Sultan (1640-1715)

173 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On 6 November 1715, Emetullah Rabî'a Gül-nûş Valide Sultan died:

The dynastic politics of the seventeenth-century Ottoman Empire, when the mothers of Ottoman Sultans were the utmost authority, gave her the chance to exercise power via a domineering influence on her two sons, to which contemporary European sources also attest, and she was the second and the last queen mother after Kösem Sultan to see both of her sons’ reigns. Despite the fact that she has heretofore been excluded from the so-called Sultanate of Women, her influence has largely been underobserved in contemporary studies. However, her correspondence with foreign sovereigns – such as the King of Sweden or the Khan of Crimea – her advice to grand viziers (and her manipulations to appoint or depose them), her persuasion of her son to declare war, her consent for the replacement of one of her reigning sons with the other and countless unwritten histories compel us to reconsider her power and influence. Rather, Gülnüş Sultan ought to be considered as an active participant in the Sultanate of Women, indeed a very distinguished participant, to which her extensive building and patronage projects attest. — Muzaffer Özgüleş, The Women Who Built the Ottoman World: Female Patronage and the Architectural Legacy of Gülnüş Sultan

164 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐝𝐚𝐲 𝐢𝐧 𝐎𝐭𝐭𝐨𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐡𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐲, 𝐒𝐚𝐡 𝐒𝐮𝐥𝐭𝐚𝐧 𝐝𝐢𝐞𝐝:

Şah Sultan was born in 1544 in the Ottoman province of Konya to Prince Selim (later Selim II) and his consort later wife Nurbanu Sultan. According to some sources, she was the eldest of their children.

Şah, together with her full-blooded sisters Gevherhan and Ismihan, got married in 1562 on her grandfather Suleyman’s wishes to Çakırcıbaşı Haşan Ağa (later Paşa and kubbe vizier). The couple had no issue. Haşan Paşa died in 1574 and Şah married Zâl Mahmûd Paşa in what it seems to have been a love match and the princess’ choice. The two had an unnamed daughter, who later married one Abdâl Hân, and Sultânzâde Köse Husrev Paşa, who died fighting the Safavids.

According to Ibrahim Pecevi, Şah Sultan and Zâl Mahmûd Paşa fell sick on the same day and died together in their bed, only 12 days between them. They were buried in the mosque they had built, the Zâl Mahmûd Paşa Camii. // Hazal Filiz Küçükköse and Acelya Devrim Yilhan as Şah

411 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“One day around this time, Princess Fatma came by to pay another visit to her brother, but the gate guards, who had come from Yıldız Palace, refused her permission to enter. That led to quite a scene at the gates of the palace, with Princess Fatma defiantly exploding, “Indeed! And just who is preventing me from entering? Is it that miserable blackguard? Who does he think he is, trying to keep me from visiting my brother? I want to see my brother, and until I do, I am not moving! I shall spend the night here if I must!” In the street a crowd gathered, which policemen from the Beşiktaş station dispersed as they cordoned off Princess Fatma’s carriage. The Yıldız Palace officials went hysterical at what was happening. Up to the palace they ran and informed Sultan Hamid. After a while Cevher Ağa came down and said, “Begging Your Highness’s pardon … the guards misunderstood their orders! His Majesty in no way restricts members of the imperial family from visiting one another!” This soothed Princess Fatma’s rage, and into the palace she went, weeping all the way to our master’s apartments, where brother and sister hugged and embraced one another and talked for hours until finally they took their leave of one another with more embraces.” – Douglas Scott Brookes, The Concubine, the Princess, and the Teacher: Voices from the Ottoman Harem

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

(OTTOMAN) WOMEN’S HISTORY MEME | 5 princesses: Selçuk Hatun, daughter of Mehmed I

“[Selçuk Hatun] became a widow after [Karaca Paşa] was martyred in the war of Varna. She settled in Bursa and spent the last years of her life doing good deeds and praying. Fatih Sultan Mehmed assigned many villages and farms to his beloved aunt. Selçuk Sultan led a comfortable life thanks to the allocations and assignments made to her.” — Çağatay Uluçay, Harem'den Mektuplar

154 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day in Ottoman history, 16 October 1805, Mihrişah Valide Sultan died:

“The Sultana had been a woman of great beauty, and strong natural talents, fond of the English nation, and averse to the dark intrigues of the French and Russian factions. During her whole life-time, she had, in conjunction with her favourite Yusuf, contrived to direct her son, and manage all the affairs of the empire. Her maternal affection for Selim was so strong, that, when the French army treacherously seized upon Egypt, she kept the secret confined to her own bosom rather than permit is communication to distress the Sultan, to whom, being of a very nervous temperament, the smallest trifle was sufficient to cause agitation and alarm. In return, Selim bore his mother no common degree of filial affection, he felt her loss severely, and time alone enabled him to regain the usual serenity of his mind.” – Adam Neale, Travels through some parts of Germany, Poland, Moldavia, and Turkey

473 notes

·

View notes

Photo

VALIDE SULTANS: “The change in Harem life began with the sensitive and unusually intelligent sultan, Selim III, who was murdered in 1807. Part of his zeal for reform came from his mother, Mihrişah Valide, to whom he was devoted. A Georgian, she was said by Dr Neale (the pre-eminent physician of his day who made a tour of German, Poland and Ottoman territory at the beginning of the nineteenth century) to have had more influence on her son that any other Valide had done before. It was certainly she who introduced baroque to Topkapisaray, and to her own gorgeous apartments in particular […]” – Godfrey Goodwin, The Private World of Ottoman Women // Ipek Tenolcay as Mihrişah

739 notes

·

View notes

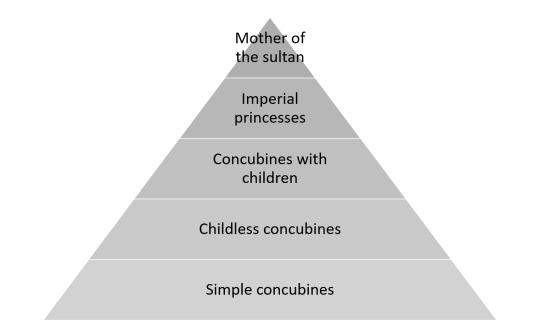

Note

The haseki sultan was ranked below the valide?when the absence of a valide, a haseki could hold as much as power like a valide?When the haseki was abolished after the kadins werent as powerful as hasekis?Why just the valide got the sultan title from the non-imperial women? A haseki in the presence of a valide was just a well paid consort basically?it will be a tough question but how can you explain and compare the pre sultanate of women ranks with the sultanate of women and the late periodranks?

There is so much to unpack here, I will try my best (though I think I have already answered all of these questions)

I'm afraid this will be very long.

The haseki sultan ranked right below the valide sultan, as she was the only consort who had been accorded the title of sultan, reserved to members of the Dynasty. In the Ottoman empire the valide sultan was the first woman in the empire because she was the mother of the sultan himself. Her titles indeed included things like the great cradle or the nacre of the pearl of the sultanate.

I don't think a haseki sultan can ever replace a valide sultan, but Nurbanu's tenure as haseki is certainly interesting in this respect:

Yet that station [wedded wife of Selim II] still fell short of the highest echelon that an Ottoman royal woman could reach, that of a Valide. Nurbanu devised an ingenious solution to create that effect, which consisted of transmitting her two-pronged identity, as Selim’s Haseki and Murad’s Valide, pari passu. It will be recalled from Cavalli’s relazione in Cronaca Lippomano mentioned above, in which he stressed Nurbanu’s flaunting in of her twin titles in one breath, “Wife of the Signor” and “Mother of Sultan Murath.” She continued this practice for some time, eventually dropping the first component, Haseki, and keeping only the second element of the composite title, Valide. This transformation is evidenced in a mühimme entry dated 23 Ramadan 973 (1570) involving the procurement o f marble to be used in the construction of Nurbanu’s pious architectural project, the Atik Valide. In this document Nurbanu refers to herself exclusively as “mother of my son, the estimable son Murad, ” while it was her husband, not her progeny, who was ruling as Padishah when the construction was under way. As for Selim, acting on behalf of the Valide Sultan, orders the kadıs of Sabancı and Iznikmid to collect without delay all the marble from the fields, meadows, and dilapidated buildings of their bailiwicks, fully compensating their eligible owners, while refraining from harming any occupied residences. [...] Necipoğlu has discovered a number of imperial decrees issued by Selim II pertaining to the construction o f the Atik Valide Mosque Complex in which Nurbanu is referred to as the Valide Sultan, although it is her husband who is the reigning monarch and not her son. — Pinar Kayaalp-Aktan, The Atik Valide Mosque Complex: A testament of Nurbanu's prestige, power and piety

I personally don't believe that Nurbanu was acting as valide sultan; on the contrary, she was acting as a European queen consort and more or less like Hürrem: that she started to build her mosque during Selim II's reign (like Hürrem had done) and that she was known as the mother of the sultan's son... I think Nurbanu has more similarities with Hürrem than we'd usually think.

On the other hand, we cannot forget that Mihrimah was still alive and that she was a point of reference for Selim:

New sultans made their way to the harem at the earliest opportunity after arriving in the capital: Selim II sought his sister Mihrimah (his mother Hurrem had died eight years earlier), and both Murad and Mehmed conferred with their mothers. This urgency no doubt reflected the new sultans' need to he informed of the political situation in the capital by a trusted ally, as well as their desire to be reunited with loved ones. It also reflects the importance of female elders in the hierarchy of the imperial household. — Leslie P. Peirce, The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire

It is also interesting that on the inscription of her mosque in Üsküdar, Mihrimah is hailed as "protector of the state and the world and the faith".

So, while Nurbanu lived in Topkapı with Selim and started to build her mosque, the Atik Valide; Mihrimah was instrad in the Old Palace, overseeing the harem of her brother.

So I personally think that the duties of a valide sultan were shared between Mihrimah and Nurbanu.

The kadıns are a different thing from the haseki. First of all, they do not carry the title of sultan, and secondly they are not as special because there are at least 4 of them (actually, they weren't limited by number at first). Of course here we're talking about the great hasekis: Hürrem, Nurbanu, Safiye, Kosem... and Emetullah Rabia Gülnüş too).

The presence of more than one haseki was a significant change in the reigns of Murad and Ibrahim, signaling that the age of the favorite was coming to an end. In this period the meaning of the title haseki begins to shift from a single "favorite" to something more general like "royal consort." similar to the earlier khatun. This title deflation was a sign of the return of an earlier principle of royal reproduction, that of a number of concubines roughly equal in status. That other concubines were no longer consigned to languish in the shadow of a favorite is suggested not only by the fact that each was endowed with the title haseki but also that their stipends were on the whole equal. While the contrast between the stipend of Nurbanu, Selim II's haseki, and that of the mothers of his other sons was enormous (at the end of Selim's reign Nurhanu received eleven hundred aspers a day but the others a mere forty aspers), Murad's two hasekis and Ibrahim's eight hasekis received roughly equal stipends at the one-thousand-asper level and higher.

By the end of the seventeenth century the title haseki was falling out of official use and was being replaced by the less elevated title kadın. A set hierarchy was emerging according to which the sultan's first concubine (or the mother of his first child, but not necessarily his first son) was known as "head consort" (baş kadın) and subsequent concubines as "second consort" (ikinci kadın) and so forth. A distinctive feature of this settled pattern of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is that the one mother-one son principle continued to be observed virtually without exception. — Leslie P. Peirce, The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire

The kadıns would never reach the hasekis' influence and powers because the Ottoman succession system had gone from open to strict seniority. There was no need anymore for the sultan's consort to be that powerful so as to influence statesmen in the open succession, because her son would never succeed his father— not directly, anyway.

Öztuna says that the title of kadın appeared in 1703, with Ahmed III's reign, but Peirce was able to find harem documents from Süleyman II's reign in which his consorts are all titled kadın. Ahmed II's consort Haseki Rabia Sultan is, indeed, the last haseki sultan of the empire.

Comparison of harem hierarchies

For simplicity we're going to analyse the harem hierarchy of Bayezid II for the pre-sultanate of women period, during whose reign the princesses had acquired the title of sultan.

Mother of the sultan: before the reign of Süleyman I, the mother of the sultan did not have a specific title. She just ranked higher than other members of the harem because she was the mother of the sultan and she was the manager of the harem, of course.

Imperial princesses: they were the only women to carry the title of sultan (bestowed upon them by Bayezid II himself)

Concubines with children / childless concubines: they held the title of hatun, which can roughly be translated as lady.

Simple concubines: by this I meant that they lived in the harem but they had not been bedded by the sultan. We call them cariyes: slaves without a status

the harem during the Sultanate of Women:

Valide Sultan: the mother of the sultan, she oversaw the harem and was the highest-ranking woman in the empire

Haseki Sultan: the favourite consort. She was either the mother of the eldest son (like Emetullah Rabia Gülnüş, Nurbanu and Safiye) or just the most beloved consort of the sultan (like Hürrem, Kösem and Rabia). She usually had several children because with her the sultan did not follow the one mother-one son rule

Imperial princesses: they ranked below the haseki sultan, because the haseki was the mother of a potential sultan

Concubines of non-haseki rank who are mothers of children: their title was hatun (lady) and their stipend was ridiculously lower than the haseki's. They usually could not afford to undertake building projects but they could sometimes fund prayers recitals in mosques or minor charities.

Childless concubines of non-haseki rank: their title was hatun as well but of course as they weren't mothers of imperial children their rank in the harem was lower.

Gözdes: bedded concubines. They resided in Topkapi Palace because they were "in the eye of the sultan", as their names means. Either they got pregnant and therefore moved back to the Old Palace or they kept sharing the sultan's bed until he a) got tired of them or b) got pregnant.

Simple concubines: the cariyes. They are title less and without a status.

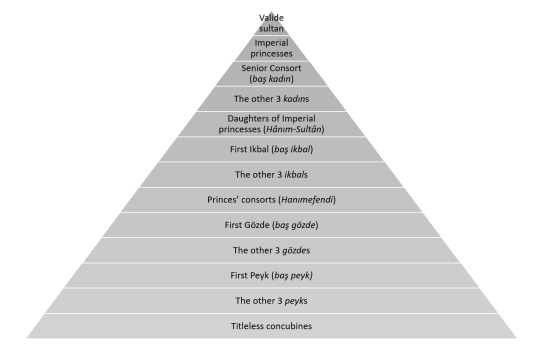

the harem in the XIX century:

For simplicity, we’re going to consider a harem of the late Ottoman empire, when the hierarchy was more or less firmly established.

Valide Sultan: the sultan's mother, she carried the title of sultan and her title in European contexts was Her Imperial Majesty. She is considered the only empress in the empire

Imperial princesses: the sultan's daughters or the daughters of princes. They ranked by seniority and their European title was Their Imperial Highnesses.

Senior Consort (baş kadın): usually the first consort the sultan had bedded or the mother of the eldest child. Her European title was Her Majesty, and she was considered like a queen consort. She retained the title all her life unless she divorced from the sultan.

The other three kadıns: they were numbered by seniority (that is, when they married the sultan), their European titles was Their Majesties, just like the Senior Consort— though of course the Senior Consort ranked higher than them and if the valide sultan wasn't alive she would manage the harem in her stead. In the XVIII century they could be more than 4: we have cases of a fifth kadın or a sixth kadın. Nakşıdil Kadın was the eighth Imperial consort of Abdülhamid I

Daughters of Imperial princesses (Hânım-Sultân): they ranked by seniority and their title meant that their father was a subject but their mother was a member of the Dynasty. When they married, their husbands could not use the title of damad, and their children did not hold any title or privilege.

First Ikbal (baş ikbal): the 5th consort of the Sultan. If the 4th kadın dies, she can take her title and therefore jump class. Her European title was Her Highness, therefore being considered like a "princess" consort.

The other 3 ikbals: they were numbered by seniority and titled Their Highnesses. Technically they were not limited by number, actually it was rare that there were more than 4 ikbals.

consorts of princes: the first 4 were titled hanımefendi, with the first being titled Başhanımefendi and addressed by her title and not by name. The Başhanımefendi of the eldest prince alive was the highest-ranking consort among the consorts of princes. The other three consorts were addressed by "name + Hanımefendi". After the fourth consort, the other women the prince bedded were considered odalisques and without a status. Their European title was Their Highnesses.

First gözde (baş gözde) + the other 3 gözdes: the sultan's consorts from the 9th to the 12th. Their title means "in the eye of the sultan" and they're the most recent favourites the sultan has. They were not limited by number and did not rank by seniority. They were addressed by Hanımefendi.

First Peyk (baş peyk) + the other peyks: the last class of consorts, they are not very usual because it's strange for a sultan to have more than 12 consorts alive at the same time. They were addressed by Hanımefendi and rank the lowest among the consorts with the hanımefendi title. They usually are not mothers of children.

Simple concubines: also called odalisques or chamber maids. They have no title and no privileges. They're exactly like the cariyes of the previous periods.

As you can see, the harem hierarchy became more complicated and rigid as time progressed. The necessity of a hierarchy so complicated as the one of the late Ottoman empire arose from the fact that sultan's consorts were increasingly taken by foreign noble families so they were actually princesses before marrying the sultan. It was necessary for each and one of them to have a status within the harem because they were not just nameless slave concubines.

Sources for the hierarchies: Harun Açba - Kadin Efendiler, Juliette Dumas - Les perles de nacre du sultanat, Yılmaz Öztuna - Devletler ve Hanedanlar

91 notes

·

View notes