Note

Do you have a post on Maria Reynolds? I haven't been able to find much information about her, I read she became a nun or something after the scandal??

i know i do, i am struggling to find it because tumblr's search function has and always will be ass

RAHHH I CANT FIND ANY OF THEM fuck this im giving you a short history of her life because i love you with all my heart

DISCLAIMER: i fucking hate Ron Chernow, especially for his treatment of Maria Reynolds in his book, but him and wikipedia are all I have right now and my relationship with him is very toxic pls help

Early Life

Maria Reynolds was born as Mary Lewis on March 30, 1768 to Susannah Van Der Burgh and Richard Lewis, who was Susannah's second husband. She had eleven siblings, and they did not have very much money, and were likely a pretty average 18th century white family in America, with poor literacy rates, struggles with debt, and the women being taken advantage of. They lived in Dutchess County, New York.

Maria was literate, but not well educated. This is something she was strongly mocked for by both her husband, Hamilton, Chernow, and other men. Well, I guess Hamilton didn't really mock her, but he definitely looked down on her for it. Fucking asshole. She also seemed to have very strong mood swings from a young age, and this could have been something psychological, like a mood disorder, or it could have been physiological or hormonal, such a menstrual disorder that was never properly treated because women's issues were not taken seriously at the time, mental or physical. This is also something she was mocked for.

Maria was married off to James Reynolds, a Revolutionary War veteran, on July 28th, 1783 when she was 15 years old. James Reynolds often lobbied the government for money after the war, foreshadowing his debt problems and later exploitation of his underage wife for money.

Together, the couple would have one daughter, Susan, named after her grandmother, who was born on August 18, 1785. Maria showed herself to be a devoted mother who would do anything for her daughter, including putting herself in harms way to make sure she didn't face the same fate. Unfortunately, Susan would also later be in an unhealthy relationship, despite her mother's efforts.

Maria Lewis was always described as very emotional, innocent, smart, and pretty, despite those who attempted to degrade her.

Men before Hamilton

It was early in her marriage when she was looked down upon by men, beginning with the son of her first landlady in Philadelphia.

"Her mind at this time was far from being tranquil or consistent, for almost the same minute that she would declare her respect for her husband, cry and feel distressed, [the tears] would vanish and levity would succeed, with bitter execrations on her husband. This inconsistency and folly was ascribed to a troubled, but innocent and harmless mind... [Reynolds] had frequently enjoined and insisted that she should insinuate herself on certain high and influential characters- endeavor to make assignments with them and actually prostitute herself to gull money from them." -Richard Folwell, August 12, 1797

Her complicated feelings about her husband allowed men to reduce her to being deceptive, however it shows that she was torn between her bias towards her husband, who had been around her and influencing her throughout her formative, adolescent years, and the things he was asking her to do, including prostituting herself.

These escalated to more than requests for her to prostitute herself to rich men into demands and threats. Reynolds became physically abusive to his wife if she did not comply with his demands to sleep with and extort rich men. Eventually, this became a pattern, and she became known as a prostitute who slept separately from her husband so she could entertain her midnight visitors, when essentially she was being human trafficked by her husband at the age of 18.

There is evidence to suggest that she only slept with Hamilton when Reynolds threatened to physically abuse her daughter, Susan. I'm not going to go into too much detail about the affair because I believe it's over done, but I am going to discuss how Ron Chernow talks about this woman, and the consequences of victim blaming.

Ron Chernow Hates Women

Ron Chernow discusses the Reynolds Affair in chapter 19 of his novel Alexander Hamilton. Already, he places some of the blame on Elizabeth Hamilton with the sentence "It was a dangerous moment for Eliza to abandon Hamilton,", even though he likes to put her on a pedestal so people think he's a feminist (Chernow 363). You're not a feminist, Ron, you're a 75 year old incel, and I feel bad for your wife.

Chernow introduces Maria Reynolds by stating her age at the time of the affair (23), and for some reason, making up the fact that her name is pronounced "Mariah"??? He gives no citation for this, so I'm assuming he made it up to make her seem more slutty. Her name was Maria. Actually, her name was Mary, but if we had any link between her and the Christian figure for maternity and purity, well that wouldn't work with the portrayal of her as a disgusting, crazy, lying whore, right?

Chernow uses words like "doleful tale", "fanciful", "conspired", and "trickster" to describe Maria, but gives no proof of her malicious intent towards Hamilton. He portrays Hamilton as vain, however a savior to Maria, and she simply HAD to have been in love with him because of how good of a person he was. Ron Chernow manipulates Maria Reynolds' character to fit his personal belief that there are two kinds of women: good, pure, Christian homemakers, and uneducated sluts who deserve their mistreatment from men (Chernow 367).

Even though Ron Chernow finds it more comfortable to believe that Maria worked in cohorts with her piece of shit husband, and that they together decided to use Hamilton for his money, the truth is that she was a severely abused woman throughout her entire life, especially at the hands of James Reynolds. Her manipulation of Hamilton was not to gain something, but to prevent her and her daughter from being abused. Chernow glosses over this, dismissing it as something she made up to secure a divorce, but it was proven true in a court of law. Chernow's famous cognitive dissonance strikes again: the US government is very securely made with a magnificent justice system, yet uneducated, illiterate women can manipulate it to get... a piece of notarized paper! Yeah, don't let this senile old man write any more books. Thanks.

Aftermath

The backlash from The Reynolds Pamphlet, published 1797, would haunt Maria for the rest of her life. She remarried twice, once to Jacob Clingman, who is another piece of shit who should have his dick guillotined, and the other time to Dr. Matthew (idk his last name) who she was a housekeeper for. She allegedly wrote her own pamphlet, but never published it. Idk anything about that.

Maria would raise her two grandchildren after her daughter's untimely death. She also changed her name back to Mary, becoming Mary Matthew for the rest of her life. She was devoutly religious, joining the Methodist Church, but not a nun. She died loved on March 25, 1828. And if there isn't someone on earth who loves Mary Matthew, then I am dead.

Here's your Maria Reynolds post. I love her so much, and I will defend her until I have no voice left, my fingers can't write or type, my eyes can't move, and my legs can't walk. She deserves so much better than what she got and how she's been portrayed. Vive Mary Lewis.

#history#amrev#american history#women's history#maria reynolds#the reynolds pamphlet#the reynolds affair#alexander hamilton#asks

48 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, so recently I saw a post about the misogyny of hamilton, so I wanted to ask you if it was true. Not the part of misogyny (because in that time it was normal, I guess), but rather how much was? (does make sense?), did it affect the relationship with eliza or with her daughters?

Thankyu!!! (Muak)

hm okay so im not completely sure what you mean but i am going to do my darndest

So, in the time period which Hamilton was alive, which is the latter half of the 18th century, there definitely was a profound attitude of misogyny, but it was very different from what we know today. Most of our idea of sexism comes from the religious revivals of the 20th century (and people who know me know how i feel about the godforsaken 20th century when it comes to history). This is yk your typical idea of a housewife being at home, taking on the burdens of homemaking and child rearing and basically keeping everything together at home while the husband worked a stressful 9 to 5 and didn't do shit at home and weaponized incompetence and implicit biases and yadayada

This was not the case in the 18th century! 18th century gender roles are very different from what we're used to, and even more different than what the Victorians and Edwardians considered the norm. This is especially visible in Hamilton's relationship with women, so I'm quite excited to talk about this.

Firstly, I want to talk about the joker to my batman: Ron Chernow. A major theory he supports in his biography of Hamilton is the two sided nature of Hamilton's perception of women. He says that there is a clear distinction between two "types" of women in Hamilton's wife-- the good, Christian mistress of the house and the stupid, mentally unstable skank. These are his terms. I want to hit him in the head with a brick.

"Together, the two eldest [Schuyler] sisters formed a composite portrait of Hamilton's ideal woman, each appealing to a different facet of his personality. Eliza reflected Hamilton's earnest sense of purpose, determination, and moral rectitude, while Angelica exhibited his worldly side- the wit, charm, and vivacity that so delighted people in social intercourse." -Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, page 133

Yeah, this is horseshit. It gets worse when he compares Elizabeth Hamilton and Maria Reynolds on page 367, but I'm not going to get started because I won't stop. And this isn't about him anyway.

Instead, I want to talk about WHY this is horseshit. First of all, even Alexander "thinks with the wrong head" Hamilton didn't have this fucked up mindset, because it is heavily based in 20th century evangelicalism that didn't even exist in Hamilton's world.

Yes, obviously there was religious attitudes that condemned certain actions from women, but this was not as intense as in later periods. In the 18th century, an upperclass woman, such as Elizabeth Hamilton, would be responsible for maintaining the household, but this meant being in charge of the servants rather than doing the work herself. The work she did do would be maintaining the finances and the family's reputation.

Reputation was everything in the 18th century, and this especially applied to women. Not only did they have to maintain their own reputations, but they had to raise their children to have the skills necessary to do the same, and often had to fill in for their husbands in this department if they held public office. It's very difficult to maintain your reputation if you're beating people with walking sticks in the Continental Congress.

When it came to lower and middle class women, their jobs weren't different in that they carried an equally important role in the family. They would be doing household chores just as well as their husband, and these weren't easy chores that made women "feeble". They very often took a lot of physical strength and endurance, and it wasn't considered unladylike for women to do "men's" chores while their husbands were away. This isn't to say that women in later eras didn't do the same, but it wasn't as publicly frowned upon.

Hamilton had a very unique perspective as he was witness to both sides of this coin. His mother, a single, working class mother would be juggling both the man and woman's role. I think it was really this background that allowed him to have a much more informed perspective on womanhood. He was one of the few men in this period that I've seen write from the perspective of a woman, specifically a grieving mother.

"For the sweet babe, my doting heart

Did all a mother's fondness feel;

Careful to act each tender part

And guard from every threatening evil.

But what alas! availed my care?

The unrelenting hand of death,

Regardless of a parent's prayer

Has stopped my lovely infant's breath-"

-Papers of Alexander Hamilton, volume 1, page 43.

Chernow attributes this to Hamilton's deeply empathetic nature, which is fair, however I think it also shows that he was able to understand a woman's experience specifically.

I say this because Hamilton does tell us a little bit about exactly what was expected of women in the time during Elizabeth's first pregnancy in a letter that is usually used to call him a sexist, but I think it's a little more complex than that. Here's the excerpt:

"You shall engage shortly to present me with a boy. You will ask me if a girl will not answer the purpose. By no means. I fear, with all the mothers charms, she may inherit the caprices of her father and then she will enslave, tantalize and plague one half [the] sex, out of pure regard to which I protest against a daughter. So far from extenuating your offence this would be an aggravation of it." -Alexander Hamilton to Elizabeth Hamilton, October 12, 1781

In this letter, Hamilton isn't telling Elizabeth that he wants a boy to inherit his fortune, to carry on his name, or the other reasons that were given by his contemporaries for preferring sons over daughters. He specifically states that his reasons are his fear that his traits will be passed onto his children, and that if its a daughter, she will be more discriminated against than his son because of her sex. Essentially, it was easier to be a gay son in the 18th century than a thot daughter. In that question, Hamilton would choose gay son because he knew that men were generally less criticized than women.

So, I'm not saying Hamilton wasn't sexist, because, by definition, he was. He was taught that women were fundamentally different than men, but he didn't look down on women for that, because that simply wasn't normal. You wouldn't be a gentleman if you looked down on a woman for being physically and psychologically different from a man, you'd be an asshole. While their interpretations of these differences don't align with what modern medicine has determined, they weren't the same as in the later eras in American history. Women were, most certainly, oppressed because of these perceived differences, but it was a different system of oppression than what typically defines our idea of sexism.

It's hard to say if it affected Hamilton's relationship with his wife and daughters, as there isn't any real written proof, but I imagine Hamilton's attitude specifically towards women did make their relationship different than other fathers, daughters, husbands, and wives of the time. We do know that Hamilton was a very hands on father who dedicated a lot of time and care towards his children, and he did not treat his daughters any differently than his sons. He put the same amount of energy into their education, though they weren't educated in the same thing, and he seemed to be equally close with all his children.

Hamilton and women is a very interesting topic, and it gets more complicated when it comes to Rachel Faucette and Maria Reynolds and those parallels, but that is a topic for another time. Good thing its women's history month! Hope this helped :)

#alexander hamilton#history#amrev#american history#elizabeth hamilton#women's history#18th century#founding fathers#founding mothers#women's history month#asks

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

From what I know, no. Before his marriage, he showed interest in a few women, but ultimately courted Martha. Then there was Betsey Walker, who he harassed for several years, but I believe that was after Martha’s death (correct me if I’m wrong). His relations with Sally Hemmings began at the end of his tenure in Paris, and the women he flirted with there were still long after Martha’s death.

Don’t apologize for questions. I love questions

Can you tell me everything you know about Martha Jefferson?

I would love to. In my opinion, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson is one of the most tragic figures of the 18th century, and her life shows the many challenges a woman would face in this time period, due to the incredible expectations put on them. I'd like to open by saying that the importance of discussing women in history not only gives us a more full perspective on any and every historical event, but it also gives light to less commonly discussed historical figures that were equally important that we don't know as much about. Martha Jefferson is undoubtably one of those people.

Martha Wayles was born on October 30, 1748 to her wealthy father. Her father was an English immigrant who moved to America and accumulated a decent fortune through slave trading, planting, and his law practice.

Content warning: mention of sexual assault within slavery, skip next paragraph if this may be distressing

Her father is a very interesting figure. In his law practice, he specialized in debt collections, which made him very unpopular among the locals. Additionally, he raped an enslaved woman on his property several times, Elizabeth Hemmings, after the death of his third wife. She would have several children by him, including Sally Hemmings, who would later be raped and have several children by Thomas Jefferson. It is disgusting, but crucial to mention that because of the slave system in America, and the violation of African American women, Martha Jefferson was the half sister of Sally Hemmings.

Martha married Bathurst Skelton when she was 18. They would have one child, John, who died in infancy. Her first husband died six months before Jefferson married Martha, and her first child with Jefferson, Martha aka Patsy, would come nine months after Martha's first child. Her almost constant pregnancy and troubles in maternity would eventually lead to her death.

She married the very eligible bachelor Thomas Jefferson on New Years Day, 1772 at her plantation home, "The Forest". There was a five year age gap between them, as she was 22 going on 23, and he was 28. Jefferson would actually scarcely mention her first husband, and would even report false information that he did not exist, that Martha was a spinster when he married her. The motivations for this are not confirmed.

The young couple arrived at Jefferson's home, Monticello, during a snowstorm, where all the servants were asleep and the house was cold. They toasted their marriage with a leftover bottle of wine, and entered into a period of domestic happiness.

Martha and Thomas had complimentary personalities, balancing out each other's characteristics. They shared an interest in music, as Jefferson played the violin or the cello, and Martha played the piano or the harpsicord. She was said to be very talented.

While there is no known portraits of her, she was described as very beautiful and accomplished. She was slim with hazel eyes and auburn hair. She was the subject of frequent praise from all that knew her.

The Jeffersons had five children in ten years, but only two would survive to adulthood, Martha (Patsy) and Mary (Polly or Mary). Martha was under such strain from her frequent pregnancies that she fell very ill in 1781. The British had invaded Richmond, which forced her away from her husband back to Monticello, but Jefferson often left his political career to stay with her during her sickness. The British would raid Monticello, forcing her to travel in her poor condition yet again.

Her condition continued to worsen, until she died on September 6, 1782, at 11:45 AM at the age of 33. Jefferson would never record his relationship with her, so her life remains mostly a mystery among historians.

Martha Jefferson was far more than the deceased wife of the third president. During her life, she was the mother of several children, who frequently had to grieve their deaths. She was the mistress of a fashionable household, and the wife of an energetic, young politician who was making strides in the cause of liberty and American independence. Her life was riddled with tragedy and mourning, but she was a lively, creative woman who had an untimely death at a cruel age.

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thank you so much for adding this! I couldn’t find much, so im so happy to have more details about her

Can you tell me everything you know about Martha Jefferson?

I would love to. In my opinion, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson is one of the most tragic figures of the 18th century, and her life shows the many challenges a woman would face in this time period, due to the incredible expectations put on them. I'd like to open by saying that the importance of discussing women in history not only gives us a more full perspective on any and every historical event, but it also gives light to less commonly discussed historical figures that were equally important that we don't know as much about. Martha Jefferson is undoubtably one of those people.

Martha Wayles was born on October 30, 1748 to her wealthy father. Her father was an English immigrant who moved to America and accumulated a decent fortune through slave trading, planting, and his law practice.

Content warning: mention of sexual assault within slavery, skip next paragraph if this may be distressing

Her father is a very interesting figure. In his law practice, he specialized in debt collections, which made him very unpopular among the locals. Additionally, he raped an enslaved woman on his property several times, Elizabeth Hemmings, after the death of his third wife. She would have several children by him, including Sally Hemmings, who would later be raped and have several children by Thomas Jefferson. It is disgusting, but crucial to mention that because of the slave system in America, and the violation of African American women, Martha Jefferson was the half sister of Sally Hemmings.

Martha married Bathurst Skelton when she was 18. They would have one child, John, who died in infancy. Her first husband died six months before Jefferson married Martha, and her first child with Jefferson, Martha aka Patsy, would come nine months after Martha's first child. Her almost constant pregnancy and troubles in maternity would eventually lead to her death.

She married the very eligible bachelor Thomas Jefferson on New Years Day, 1772 at her plantation home, "The Forest". There was a five year age gap between them, as she was 22 going on 23, and he was 28. Jefferson would actually scarcely mention her first husband, and would even report false information that he did not exist, that Martha was a spinster when he married her. The motivations for this are not confirmed.

The young couple arrived at Jefferson's home, Monticello, during a snowstorm, where all the servants were asleep and the house was cold. They toasted their marriage with a leftover bottle of wine, and entered into a period of domestic happiness.

Martha and Thomas had complimentary personalities, balancing out each other's characteristics. They shared an interest in music, as Jefferson played the violin or the cello, and Martha played the piano or the harpsicord. She was said to be very talented.

While there is no known portraits of her, she was described as very beautiful and accomplished. She was slim with hazel eyes and auburn hair. She was the subject of frequent praise from all that knew her.

The Jeffersons had five children in ten years, but only two would survive to adulthood, Martha (Patsy) and Mary (Polly or Mary). Martha was under such strain from her frequent pregnancies that she fell very ill in 1781. The British had invaded Richmond, which forced her away from her husband back to Monticello, but Jefferson often left his political career to stay with her during her sickness. The British would raid Monticello, forcing her to travel in her poor condition yet again.

Her condition continued to worsen, until she died on September 6, 1782, at 11:45 AM at the age of 33. Jefferson would never record his relationship with her, so her life remains mostly a mystery among historians.

Martha Jefferson was far more than the deceased wife of the third president. During her life, she was the mother of several children, who frequently had to grieve their deaths. She was the mistress of a fashionable household, and the wife of an energetic, young politician who was making strides in the cause of liberty and American independence. Her life was riddled with tragedy and mourning, but she was a lively, creative woman who had an untimely death at a cruel age.

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you tell me everything you know about Martha Jefferson?

I would love to. In my opinion, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson is one of the most tragic figures of the 18th century, and her life shows the many challenges a woman would face in this time period, due to the incredible expectations put on them. I'd like to open by saying that the importance of discussing women in history not only gives us a more full perspective on any and every historical event, but it also gives light to less commonly discussed historical figures that were equally important that we don't know as much about. Martha Jefferson is undoubtably one of those people.

Martha Wayles was born on October 30, 1748 to her wealthy father. Her father was an English immigrant who moved to America and accumulated a decent fortune through slave trading, planting, and his law practice.

Content warning: mention of sexual assault within slavery, skip next paragraph if this may be distressing

Her father is a very interesting figure. In his law practice, he specialized in debt collections, which made him very unpopular among the locals. Additionally, he raped an enslaved woman on his property several times, Elizabeth Hemmings, after the death of his third wife. She would have several children by him, including Sally Hemmings, who would later be raped and have several children by Thomas Jefferson. It is disgusting, but crucial to mention that because of the slave system in America, and the violation of African American women, Martha Jefferson was the half sister of Sally Hemmings.

Martha married Bathurst Skelton when she was 18. They would have one child, John, who died in infancy. Her first husband died six months before Jefferson married Martha, and her first child with Jefferson, Martha aka Patsy, would come nine months after Martha's first child. Her almost constant pregnancy and troubles in maternity would eventually lead to her death.

She married the very eligible bachelor Thomas Jefferson on New Years Day, 1772 at her plantation home, "The Forest". There was a five year age gap between them, as she was 22 going on 23, and he was 28. Jefferson would actually scarcely mention her first husband, and would even report false information that he did not exist, that Martha was a spinster when he married her. The motivations for this are not confirmed.

The young couple arrived at Jefferson's home, Monticello, during a snowstorm, where all the servants were asleep and the house was cold. They toasted their marriage with a leftover bottle of wine, and entered into a period of domestic happiness.

Martha and Thomas had complimentary personalities, balancing out each other's characteristics. They shared an interest in music, as Jefferson played the violin or the cello, and Martha played the piano or the harpsicord. She was said to be very talented.

While there is no known portraits of her, she was described as very beautiful and accomplished. She was slim with hazel eyes and auburn hair. She was the subject of frequent praise from all that knew her.

The Jeffersons had five children in ten years, but only two would survive to adulthood, Martha (Patsy) and Mary (Polly or Mary). Martha was under such strain from her frequent pregnancies that she fell very ill in 1781. The British had invaded Richmond, which forced her away from her husband back to Monticello, but Jefferson often left his political career to stay with her during her sickness. The British would raid Monticello, forcing her to travel in her poor condition yet again.

Her condition continued to worsen, until she died on September 6, 1782, at 11:45 AM at the age of 33. Jefferson would never record his relationship with her, so her life remains mostly a mystery among historians.

Martha Jefferson was far more than the deceased wife of the third president. During her life, she was the mother of several children, who frequently had to grieve their deaths. She was the mistress of a fashionable household, and the wife of an energetic, young politician who was making strides in the cause of liberty and American independence. Her life was riddled with tragedy and mourning, but she was a lively, creative woman who had an untimely death at a cruel age.

#american history#history#amrev#martha jefferson#martha wayles skelton jefferson#amrev history#asks#thomas jefferson#women's history#18th century#1700s

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

realized i forgot my sources at 3 am last night mb

Sources:

Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow

American Antiquarian

Colonial Williamsburg

Stanford University

Library of Congress

hi please let me pay u somehow if u answer this because i for the life of me cannot find this out and i’m pretty sure this isn’t the kind of thing u do but

what was the primary demographic of newspaper vendors in the 18th century? how much people got their papers through subscription over buying them off the street? did people usually stay “loyal” to one publisher or did they read multiple at a time? where would you usually see vendors?

sweats profusely

okay so yeah this is really hard to find information because it was such an every day part of life that people didn't really think to document it, so i've definitely had to dig. also it is the kind of thing i do!! this is very much within my area of study, and i've even been known to answer asks outside of that, so no worries! also don't pay me, i'm too southern to accept your money. also because of the lack of resources on this, i've really only been able to 18th century North America, but you might be able to find some information on my notes on Eric Hazan's A People's History of the French Revolution in this here doc.

So, first things first, what was the primary demographic od newspaper vendors in the 18th century?

This all really depends on what newspaper your talking about, what part of the 18th century, and where it was published. Newspapers in the early part of the century were mostly confined to the town they were published in, and featured a variety of subjects of interest to that community. At the beginning of the century, the only newspaper was the Boston News-Letter which was directly curated to Puritan readers. On a larger scale, newspapers coming from England were intended for English gentlemen, not colonists.

In several critical historical moments, such as the American pre-Revolution (1760s-early 1770s), politics became hyper-relevant and the papers began to be marketed to the masses, with language being more simplified for wider understanding. Critical documents such as Common Sense by Thomas Paine were published in this period.

Aside from this, it can be inferred by the price and the movement to make them more accessible to the masses that they were most often read by the middle to upper classes. Many newspapers were created with the almost exclusive purpose of making money, so having a well funded subscriber base was crucial.

We also see later in the century that the government gave sanctions to make newspapers more accessible financially, by creating a monopoly on paper distribution which would eventually become the postal service we know today.

This postal service is also relevant to your next question: how many people got their newspapers by subscription vs buying on the street?

This also seems to be a regional thing, but newspaper subscriptions seem to become more frequent throughout the century, as we see government acts such as the Postal Clause in the US Constitution and the Post Office Act of 1792, which made subscription-based newspaper delivery easier. That indicates that more people were purchasing newspapers through subscription. Newspapers also tended to be quite expensive, so most people would share copies of the papers that they got through their subscription services.

Additionally, many people got their news outside of newspapers, due to this high price. There were also public readings of printed materials (printers usually published other forms of literature besides just newspapers) in coffeehouses, taverns, and in the streets. These readers probably also advertised the papers they were reading! so people could buy them there.

Now the next question is what I found most difficult: were people loyal to one newspaper or did they read multiple papers?

I think the only way to find this out would be to look at subscription records, but I haven't come across records from the newspaper offices, so I'd think to know for sure you'd have to look at individuals' purchase records and no one has time for that.

However, my own personal knowledge of history can come into play here. Like I said before, newspapers were usually confined to the local area. In the Revolutionary period, people usually read political newspapers that adhered to their personal beliefs, with Tories reading Loyalist papers and Whigs reading Patriot papers. These are the papers that would publish radical and exciting news accusing people of being in the opposing party, which would prompt riots, boycotts, and yk. tarring and feathering.

In the Early Republic, we see the same partisan split but with Federalists and Democratic Republicans. The Federalist paper was the Gazette of the United States and the Republican paper was the National Gazette. These two papers frequently attacked each other, and there were smaller, more local papers based off the information that they published.

Now where would you usually see vendors?

I mentioned public readings before, and that seems to be a very frequent source of purchasing newspapers. Printers also tended to have stores that also functioned as their offices, with their presses in the back or in the basements. They would also sell merchandise, groceries, and patent medicines. These would be just like normal stores in the cities! So people walking the streets would pass by them along with taverns, coffee houses, law offices, etc.

I hope this gives you all you need, feel free to ask further questions, because I'd be happy to answer them. Again, information on this kind of thing tends to be scarce, but this is what makes history research fun! Thank you for the ask :3

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi please let me pay u somehow if u answer this because i for the life of me cannot find this out and i’m pretty sure this isn’t the kind of thing u do but

what was the primary demographic of newspaper vendors in the 18th century? how much people got their papers through subscription over buying them off the street? did people usually stay “loyal” to one publisher or did they read multiple at a time? where would you usually see vendors?

sweats profusely

okay so yeah this is really hard to find information because it was such an every day part of life that people didn't really think to document it, so i've definitely had to dig. also it is the kind of thing i do!! this is very much within my area of study, and i've even been known to answer asks outside of that, so no worries! also don't pay me, i'm too southern to accept your money. also because of the lack of resources on this, i've really only been able to 18th century North America, but you might be able to find some information on my notes on Eric Hazan's A People's History of the French Revolution in this here doc.

So, first things first, what was the primary demographic od newspaper vendors in the 18th century?

This all really depends on what newspaper your talking about, what part of the 18th century, and where it was published. Newspapers in the early part of the century were mostly confined to the town they were published in, and featured a variety of subjects of interest to that community. At the beginning of the century, the only newspaper was the Boston News-Letter which was directly curated to Puritan readers. On a larger scale, newspapers coming from England were intended for English gentlemen, not colonists.

In several critical historical moments, such as the American pre-Revolution (1760s-early 1770s), politics became hyper-relevant and the papers began to be marketed to the masses, with language being more simplified for wider understanding. Critical documents such as Common Sense by Thomas Paine were published in this period.

Aside from this, it can be inferred by the price and the movement to make them more accessible to the masses that they were most often read by the middle to upper classes. Many newspapers were created with the almost exclusive purpose of making money, so having a well funded subscriber base was crucial.

We also see later in the century that the government gave sanctions to make newspapers more accessible financially, by creating a monopoly on paper distribution which would eventually become the postal service we know today.

This postal service is also relevant to your next question: how many people got their newspapers by subscription vs buying on the street?

This also seems to be a regional thing, but newspaper subscriptions seem to become more frequent throughout the century, as we see government acts such as the Postal Clause in the US Constitution and the Post Office Act of 1792, which made subscription-based newspaper delivery easier. That indicates that more people were purchasing newspapers through subscription. Newspapers also tended to be quite expensive, so most people would share copies of the papers that they got through their subscription services.

Additionally, many people got their news outside of newspapers, due to this high price. There were also public readings of printed materials (printers usually published other forms of literature besides just newspapers) in coffeehouses, taverns, and in the streets. These readers probably also advertised the papers they were reading! so people could buy them there.

Now the next question is what I found most difficult: were people loyal to one newspaper or did they read multiple papers?

I think the only way to find this out would be to look at subscription records, but I haven't come across records from the newspaper offices, so I'd think to know for sure you'd have to look at individuals' purchase records and no one has time for that.

However, my own personal knowledge of history can come into play here. Like I said before, newspapers were usually confined to the local area. In the Revolutionary period, people usually read political newspapers that adhered to their personal beliefs, with Tories reading Loyalist papers and Whigs reading Patriot papers. These are the papers that would publish radical and exciting news accusing people of being in the opposing party, which would prompt riots, boycotts, and yk. tarring and feathering.

In the Early Republic, we see the same partisan split but with Federalists and Democratic Republicans. The Federalist paper was the Gazette of the United States and the Republican paper was the National Gazette. These two papers frequently attacked each other, and there were smaller, more local papers based off the information that they published.

Now where would you usually see vendors?

I mentioned public readings before, and that seems to be a very frequent source of purchasing newspapers. Printers also tended to have stores that also functioned as their offices, with their presses in the back or in the basements. They would also sell merchandise, groceries, and patent medicines. These would be just like normal stores in the cities! So people walking the streets would pass by them along with taverns, coffee houses, law offices, etc.

I hope this gives you all you need, feel free to ask further questions, because I'd be happy to answer them. Again, information on this kind of thing tends to be scarce, but this is what makes history research fun! Thank you for the ask :3

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

to the person who asked me the newspaper question, i am dedicating almost the whole day to this, so you will get an answer quickly, but this is like the hardest ive had to dig SHFKJSHKFH

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, recently you answered an ask about how Hamilton reacted to the Hamilton-Madison fallout, and one of the things you said was "These men were very crucial figures in American law, which shows that, unlike men like Jefferson, he [Hamilton] was very selective in who he chose to associate with when it came to his work."

Was Jefferson particularly indiscriminate when it came to finding collaborators, or was Hamilton particularly selective (or a little bit of both)? Could you provide some examples for this contrast?

hello first of all, the structure of your ask had me literally salivating screaming crying on the floor because this is such a wonderfully structured ask and it is the perfect formula to get an in depth response bc there’s so much i could talk about here. i love you. anyway-

Let's break this down to each dude. First, the worst dude, Thomas "freak" Jefferson. Jefferson's political career began when he joined the House of Burgesses, which, as the name implies, is a house of Burges (its a legislature). His first major publication was A Summary View of the Rights of British America, a Revolutionary work of literature that called King George III a cunt in formal language, was done entirely by himself, and it was rejected by his contemporaries for being too radical. This gained him a reputation for being a blue haired liberal.

Source: The American Heritage Book of the Presidents and Famous Americans (book 2)

Jefferson would go on to write The Causes and Necessity of Taking up Arms with John Dickinson in July, 1775 to, yk, explain the causes and necessity of taking up arms against the British. John Dickinson was a very well known politician, being a member of the Continental Congress and one of the elite group of Americans who had the chance to be educated in England. Both Jefferson and Dickinson were known revolutionary voices, despite the differences of opinion that would arise between them in the following debate on independence. They were also both members of the Second Continental Congress.

Source: American Battlefield Trust, Delaware Historical and Cultural Affairs

The question of why Jefferson worked with Dickinson is most relevant to this ask. And the answer, in my opinion, is just because it was convenient. The Continental Congress was the best- "best"- men of each state coming together to represent their respective homelands. Dickinson and Jefferson most likely had conversations about the subject they would go on to write about, and decided to write it down and publish it for public benefit. We'll come back to this later.

Okay, now the elephant in the room: the Declaration of Independence. I find this subject so boring so bear with me. Jefferson was chosen by the Declaration committee (consisting of John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Livingston, and Roger Sherman) as he was already known as a Revolutionary writer and one of the best educated of them. He wrote the original draft on his own- well, technically- and then it was edited by the rest of the committee, and then by the rest of Congress.

Oh, but Henry! You said technically! Why? Well, dear reader, I'll tell you, be patient, jesus fucking christ. Jefferson highly based the Declaration off of Richard Henry Lee's resolution calling for independence in the Continental Congress, but mainly off of the philosophies of John Locke. That famous phrase we all know was almost word-for-word the writings of John Locke. I even once wrote an essay on how Jefferson essentially plagiarized John Locke in my sophomore government class.

"We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness..." -Thomas Jefferson, Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776

Source: my pocket Declaration/Constitution LMAO i really busted that out like an absolute nerd

"All mankind... being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty or possessions." -John Locke, Second Treatise on Government, 1690

Source: brainyquote.com and a suspicious PDF of excerpts that I narrowly avoided a virus while accidentally downloading

I think that the Declaration is a pretty good example of how Jefferson, and 18th century American government, usually performed. This famous document was created by committee, and through education on 17th century philosophy. There were not multiple men working on the original draft of this, and the men who did work on it were not selected by Jefferson, and his major works are almost entirely attributed to him alone. He'd go onto write other historical documents such as Notes on Virginia and Anas (which are a more interesting and complex document) in this same form.

Source: Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow, Founders Online

He did consult with other men when it came to information and intelligence on political enemies later in his political career. These men were mostly hyper-relevant Democratic Republicans, who tended to be rich, southern landowners (aka slaveholders), at least those who associated with Jefferson. The most iconic of these were, of course, James Madison and James Monroe. Jefferson frequently consulted them, and Monroe (allegedly) gave Jefferson copies of the documents Hamilton showed to him to prove he had not been speculating with James Reynolds, but had actually been sleeping with his wife.

Source: Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow, The Three Lives of James Madison by Noah Feldman

To summarize, Jefferson was not necessarily indiscriminate with who he associated with, and he didn't even really work that much with other men on his major writings. However, we can see a definitive pattern of Jefferson only really associating with other members of his class, neither below or above him. And this just very simply makes sense. Jefferson, as did the rest of the 18th century, believed that there shouldn't be any cross contamination between the social classes. He also believed that the only really smart people were in his class. And he wasn't aggressive about this, it's just a passive belief due to the way society was structured.

UNTIL!

Alexander Hamilton was literally opposite to Jefferson in every sociocultural way. In Jefferson's eyes he was an ambitious upstart who rose through the ranks, defying the social order that kept society from collapsing.

You'll hear a lot of people say that in forming America, the Founding Fathers had undone this rigid social class system, but that really isn't true. The class system in Europe was entirely different than the one that developed in America, but it still definitely existed in some form. Without the court system, America formed a loose sort of aristocracy that depended on land ownership and/or success in the mercantile business. In Europe, you'd see members of the clergy having their own class, but in America, it was entirely based on wealth, and less on birthright, but if your parents were not wealthy, the only way you could become wealthy was by getting in on some kind of get-rich-quick scheme, like owning a plantation or being a lawyer.

What made Hamilton different from this was that Jefferson, and other enemies, could literally watch in real time as he rose through the ranks. He could see him go from a captain in the artillery, known for his bravery in the New York campaign (someone who would eventually be forgotten), to Washington's aide-de-camp (okay... but he'll probably still fade into obscurity), to a member of the Confederation Congress (oh! well, okay, but that doesn't particularly mean anything, this is probably the highest he'll get), to the only New York delegate in town for the Constitutional Convention and the only person from New York to sign it (well that'll get him in the history books...), to the FIRST SECRETARY OF THE TREASURY OF THE NEW US GOVERNMENT (WHAT THE FUCK HOW DID HE FUCKING DO THAT WHAT THE FUCK GET HIM OUT).

Source: Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow

So, let's talk about Hamilton's political career now, specifically through tracking his writings.

One thing the musical gets right is that Hamilton DEFINITELY utilized anonymous pamphlet publishing throughout his political career. And these are some of my favorite documents ever. From A Farmer Refuted to The Monitor to The Publius Letters to Pacificus, Hamilton absolute served irreparable cunt in all of these writings, and there are more than what I've listed, I just haven't finished my chronological list of Hamilton's published works.

"I'll use the press, / I'll write under a pseudonym, you'll see what I can do to him [Jefferson]." -Alexander Hamilton in Hamilton by Lin Manuel Miranda

Source: Blumenthal Performing Arts

All of these anonymous publishings had some things in common that I've used to categorize them:

A target (usually a person he didn't like and thought was immoral)

A core lesson (typically a political stance he was taking at the time that he wanted to defend and garner support for publically)

A newspaper publisher that was symbolic or strategically important in some way (either an enemy newspaper, and up-and-coming newspaper, an old friend's newspaper, etc.)

multiple editions

2-3 coauthors/beta readers

Almost each one of these publications follows this pattern, though number 5 tends to be the least common among all of them. But, since his college days, Hamilton would ask for his friends' input on his writings (whether or not he accepted their advice is not confirmed). Before he would give his college-era speeches, he would consult with the small debate group he and his friends made before he gave those speeches. When he was writing The Publius Letters, he most likely consulted with his lover, John Laurens, on the subject matter, as Laurens had close connections with congress, and the target (number 1 on the above list) was Samuel Chase, a congressman who had basically scammed soldiers out of food, causing many to starve for a prolonged period.

Source: Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow, John Laurens and the American Revolution by Gregory D. Massey

Like Jefferson, Hamilton had his magnum opus, and the influence of others played a major role in defining the document. Hamilton would ask other men, including William Duer, and Gouverneur Morris to write this document, but ultimately settled on John Jay and James Madison. This was, of course, The Federalist.

William Duer was related to Hamilton by marriage, as they married a set of cousins. Duer was educated in England and worked for the East India Company, which gave him a very good resume to be one of Hamilton's coauthors. However, the two submissions Duer made for The Federalist were rejected. Gouverneur Morris was a blue-blooded politician who gave the most speeches at the Constitutional Convention, a whopping 173. He spoke multiple languages and had been educated at King's College, which is now the ivy league Columbia. Morris was too busy to contribute to the project.

John Jay was the first coauthor selected. He had been the main draftsman of the New York State Constitution, a negotiator of the Treaty of Paris (1783), and was another alumni of King's College. He later became the first chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, and negotiate a treaty with Great Britain. Hamilton often called on him in regards to political matters, and the two were close, lifelong allies. Jay only wrote five of the 85 Federalist essays, because he was hit in the head with a fucking brick during the Cadaver Riots.

Source: Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow

The other principal author of The Federalist was James Madison. James Madison, in my opinion, was the most qualified to write The Federalist, despite his later delusions about the Constitution (which were largely the result of Jefferson's influence on his opinion but that's neither here nor there). James Madison was educated at what was considered the greatest educational institute in 18th century America: Princeton (then called the College of New Jersey). Madison was the reason Hamilton wasn't able to take an expedited course to his degree, because Madison had attempted to finish his four year education in two years, and had a nervous breakdown... fun fact...

But, still, he got his law degree from Princeton, and was in several legislatures, including the Virginia Governor's council where he met Jefferson. And of course, he was the author of the Virginia Plan, which was the foundation of the US Constitution of 1787. His notes on the Constitutional Convention are the most complete set of notes, and he was there every fucking day. So yeah, James Madison knew the Constitution pretty well, even if he eventually cared too much about states' rights to recognize what was blatantly written in the Constitution, and maintained that viewpoint until his presidency.

Source: Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow, The Three Lives of James Madison by Noah Feldman

The Federalist was not as evenly divided between the authors as Hamilton intended, since he could not shut the fuck up, but that's not the point. The point is that the men he sought to be his coauthors had several things in common: they attended prestigious educational institutions and had long histories of Revolutionary work. Reading of these men's person histories reads like you're going through a company's qualifications for their employees. Because it almost was except they weren't getting paid. Hamilton sought out these men based on their qualifications, and, as you can see by William Duer's rejected submissions, he had a high standard that they had to fit for him to affix his name next to theirs (which he didn't do until the weeks leading up to his death because he knew he was gonna die but that's a topic for another time).

I KNOW THIS IS LONG BUT IM STILL FUCKING GOING BECAUSE THIS IS WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU GIVE ME THE CHANCE TO ANSWER COMPLEX QUESTIONS ABOUT HISTORY INSTEAD OF THE SAME FOUR SHIT SUBJECTS THAT EVERY HISTORIAN COVERS IN THEIR BOOKS THANK YOU OKAY

This pattern of finding qualified contributors to his works continued throughout his life. Now, idk if you know this, but Hamilton was actually planning another The Federalist-style publication right before his death and i am LITERALLY SO EXCITED TO TALK ABOUT THIS

Hamilton told his visiting friend James Kent that he wanted to look through all of history and analyze government and the various forms it took throughout all of written history. Mirroring The Federalist, he intended to invite six to eight authors, including John Jay, Gouverneur Morris, Rufus King, John M. Mason, and James Kent. He thought that each of these men would write about the subjects in which they specialized (Kent on law, Mason on theological history, etc.) Hamilton would be in charge of writing a synthesis on the previous volumes.

"The conclusions to be drawn from these historical reviews he intended to reserve for his own task and this is the imperfect scheme which then occupied his thoughts." -Chancellor James Kent

Source: Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow

As you can imagine, these additional dudes followed the pattern shown above for Hamilton's qualifications for his coauthors, especially for a project this big. I mean, if this could have happened, it would have been literally incredible. I did the calculations, and it would have taken Hamilton five years after 1804 to get rid of all of his debts. If he had lived for that length of time, he could have started on this project, and alleviated the debts that later plagued his family. But that ties into my other theories on Hamilton's death, and that is just too weighty of a subject to get into in a post that's already this long.

To wrap this all up, the conclusion we can draw here is really just related to the class differences between Hamilton and Jefferson. Alexander Hamilton was not bound by a lack of social mobility in the 18th century, since he completely decimated that concept by his existence, which allowed him to view his co-contributors more objectively and more selectively. He handpicked those who he worked closely with based on their qualifications and their experience. His categorization of their abilities in that last example shows that he specifically sought them to speak on subjects they were most acquainted with.

Jefferson, on the other hand, didn't have that kind of social mobility, nor did he desire it. Jefferson stuck with his peers, who were mostly all lawyers of the same religion and political beliefs. While I'm not saying Hamilton was going around and writing alongside Democratic Republicans, he certainly didn't pick those he worked with based on like-mindedness or status. He chose them entirely on the basis of their revolutionary resumes, and that is really the difference we see in these two men's respective political careers. Was that the reason Jefferson was president and Hamilton wasn't? Definitely not. Was that the reason they didn't get along? Well, it certainly didn't make them like each other. Does it make Hamilton smarter? No, surprisingly. Do I like Hamilton more because of this? No comment.

I know this is lengthy, but I've literally been brewing up historical theory in my head for the past six months without having any outlet for it besides ranting at my parents and scribbling in the margins of Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow (as you can tell by my sources). I genuinely cannot say how much I appreciate this kind of question, because it not only gets me thinking, but it allows me to remember why I got into history in the first place, and why I want to spend the rest of my life educating people on the wonderous world of pussy politics between middle aged men that are so decomposed, the matter that made up their bald ass heads is probably in your drinking water (have fun thinking about that). Anyways, thank you for the ask and I hope you got enough examples :3

#alexander hamilton#history#amrev#thomas jefferson#american history#founding fathers#gouverneur morris#james madison#john jay#james kent#early 19th century#18th century#1790s#long post

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

back back back again with the lafayette content (lafayette pt. 5)

you know the drill, here's pt. 4, gay people

Where we left off, Lafayette had just had a very exciting campaign in Rhode Island (the most exciting thing to ever happen in Rhode Island), but now what? Nothing. Nothing is happening. I'm not joking, he was bored for several months.

So, here's the real question, how would you, as a little French man in America who somehow obtained the title of major general, handle your boredom? Correct! You would duel Lord Carlisle, the head of the British peace commission.

Or at least, you'd try. Lafayette challenged Carlisle, but Carlisle fucking ignored him. Because obviously.

So when that fell through, Lafayette decided to just. go home. Not permanently, but for a visit. I mean, he was only gone for like a shit ton of time, and had left behind his pregnant wife without a real explanation, and in that time his eldest daughter, Henriette, had DIED. So, it was about time to go home. And when he was contemplating this, he checked how much money he had left, and realized he was broke and was like yeah it's time to go home.

In addition to this, he also wanted to apologize to the king since he kinda fled the country against direct orders and nearly started a war with England. One of Lafayette's main goals in life was to fight under the French flag, and he couldn't really do that unless the king liked him. So, he got a letter of recommendation and the promise of a ceremonial sword from Benjamin Franklin, and headed home to France.

Back, back, back again (in France)

Everyone was SO HAPPY to see Lafayette in France, and I would be too. Lafayette went to Versailles and was like "heeyyy King Louis XVI, my favorite king of all time, I'm really sorry for fleeing the country despite direct orders not to and nearly starting a war with England, do you forgive me?" and King Louis XVI put him on house arrest. But, to be fair, that is a very mild punishment, considering what he did was somewhat akin to treason.

Also, fun fact for the frev/Marie Antoinette girlies who know about her relationship with Lafayette during the French Revolution, she actually intervened on his behalf, which allowed him to buy a command of a regiment of the King's Dragoons! Which is like a huge favor because that command cost him 80,000 livres, which in modern US dollars is what the scholars call a shit ton.

This new popularity in France allowed him to aid the American cause in France by corresponding with French and American dignitaries, advocating the wants and needs of one side to the other. He actually played a vital role in this area, and John Adams, who did absolutely fuck all, got jealous and started beef with him for no fucking reason.

Lafayette didn't forget about his military ambitions, and was apart of a plan to attack the English mainland with John Paul Jones. This didn't work out and Lafayette was greatly disappointed (again), but it would never have been supported by France, so idrk what they expected. Fun fact, this was one of the many ideas Benjamin Franklin and Lafayette came up with together, along with a kinda gruesome children's book.

In the meantime, Lafayette daydreamed about being sent back to America in charge of the French naval forces he helped to negotiate. As you expected, he was very disappointed when they were put under the command of Rochambeau, who was just overall more qualified for the job.

While he was in France, he engaged in some ~aristocratic adventures in the arts and sciences~, and that's not an innuendo, he almost joined Franz Mezmer's cult. This is, actually, the first of two times he almost JOINED A FUCKING CULT. The second time was an Amish cult. So. There's that.

(If necessary, I can employ my boyfriend to explain how Lafayette was exactly the kind of person to get roped into a cult.)

In America Again! (This time it's Serious)

Lafayette returned in a bleak season of the war in which many of the Continental officers (Washington included) were itching for a major engagement with the British, and planned a French-American attack at some large British occupied area, hopefully with a good port.

The ideal place seemed to be New York City, and Lafayette was fixated on that. He was hoping he could have a major command in the attack. And, you guessed it, was super disappointed when he was ordered to march to Virginia to join General Greene. He was present for most of the Virginia campaign, and his main target was the traitor, Benedict Arnold.

PLOT TWIST that major attack was never in New York, but would actually be at Cornwallis' station in Yorktown, Virginia. Lafayette commanded the major Continental infantry forces that kept Cornwallis pinned at Yorktown while the commands under Washington, Rochambeau, and Admiral de Grasse surrounded him in a violent siege.

The one catch-up was that the trenches they were digging couldn't fully surround the British reinforcements due to two redoubts, 9 and 10. Lafayette's American command (led by Colonel Alexander Hamilton with his own command and Colonel John Laurens with a division under Greene) partnered with a division under Rochambeau to attack the redoubts, which led the British to surrender.

One of my favorite little details about the Revolution is that, at the surrender, the British troops refused to look at the American soldiers, so Lafayette told his band to start blasting Yankee Doodle to get their attention. Absolute icon.

I'm gonna cut this one a little early since this is the end of Lafayette's involvement in the American Revolution, and the French Revolution will require WAAYYY more attention. See you in part 6, gay people

#lafayette#marquis de lafayette#alexander hamilton#john laurens#history#amrev#george washington#american history#amrev history#american revolution

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's been a hot second since I've seen a picture of a Victorian mustache cup on here so look at this one in all its glory

This is a sippy cup. You just invented a sippy cup for manly men who want to go to tea parties and not feel emasculated by drinking too fast and getting their perfectly coifed mustaches droopy I can't

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

24 Days of La Fayette - Day 3

Have you ever wondered, why the National Guard is named the National Guard? If so, then I have a painting for you:

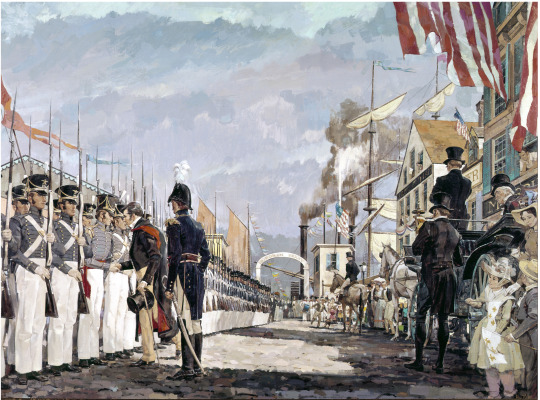

Lafayette and the National Guard, a National Guard Heritage Painting by Ken Riley, courtesy the National Guard Bureau (12/03/2023).

La Fayette’s Tour through America in 1824 and 1825 was the event of its time. People turned out by the thousands whenever La Fayette visited and even after over a year the people were still as enthusiastic as on the first day. It were not only civilians that lined the streets to greet La Fayette but also military personal. During La Fayette’s stay in New York, immediately prior to his departure for France, a company of militia men, the 11th New York Artillery, later the 7th regiment, lined the street for La Fayette. The unit had named themselves the National Guard in memory of La Fayette’s National Guard during the French Revolution. La Fayette was apparently so touched when seeing these men, that he halted his carriage and shook the hand of every single soldier. This moment is depicted in the painting.

I could sadly find no reference to this encounter in Auguste Levasseur’s book, but we do know that by 1903 the name National Guard had become so popular that it was adopted nationwide.

The painting was done by Kenneth Pauling Riley, in, I assume 2004. Riley could at that point already look back onto a long career. He had become a war artist in World War II and after the war, President John F. Kennedy purchased on of his portraits, The Whites in their Eyes about the Battle of Bunker Hill, for the White House. Riley died in 2015.

#marquis de lafayette#french history#american history#history#national guard#frev#french revolution#lafayette

82 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bodice, 18th century

From IMATEX

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, Madame Grand (1761–1835) Detail, 1783

#élisabeth vigée le brun#vigée le brun#18th century art#history of fashion#womens fashion#womens history#18th century fashion

342 notes

·

View notes

Note

i've decided that this capitalist bastard's hair and eye coloring is rather anime character coded (all those violet eyed fanarts do that to you), so i'm gonna base a character off his teens and 20s (i need an excuse to insert lams in there without others knowing). how different was his personality during the war compared to his political career?

OOOO REAL

his personality generally remained the same when it came to his core characteristics, such as being ambitious, incredibly logical and left-brained, yet also very emotional, very independent and kept people at an arm's length. He also was very impulsive, passionate, and calculated when it came to politics. In his personal life, he was flirtatious, good humored, caring, gentle, and funny. He held grudges for a long time and was very good at picking up on who was and wasn't a good person.

However, I think the most recognizable change from the war and after is that he became increasingly paranoid. He always showed signs of mental illness (highs and lows, where he'd go from being super productive and high strung and in great spirits to being super down and cynical and unmotivated), but as he got more involved in politics, he was particularly anxious about there being a plot to overthrow him and/or the government, which most of the founders experienced, but him to a very particular degree where it consumed a lot of his time and thinking. He always had an extreme fear of mob rule and violent riots due to being raised in the Caribbean where slave rebellions were seen as certain death for white people, but this was a very different kind of paranoia. He was always afraid that some faction would take over the government and the people would be doomed to live under despotism.

Also, if you wanted to count this as a change, though it's kind of different, he had a lot more domestic feelings, which played into those highs and lows that I mentioned. He really longed to be home a lot with his family and kids, which isn't something that he even had access to before since he was, essentially, homeless before and during the war. After getting married and having children, retirement was something he looked forward to more than when he was a young bachelor aide-de-camp.

Hope this helps! And I'm so sorry for the late response, like 10 asks were just sitting in my inbox without me being notified I am so sorry

#alexander hamilton#amrev#asks#historical alexander hamilton#american history#history#amrev history#us history

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

RACHEL HAMILTON FACTS

Help I have a wax museum project for school and I’m doing her I cannot find anything about her

OKOKOK This ask is the reason I opened my inbox and discovered all my unanswered asks FSHSJKHFSKH mb. My source for this is Ron Chernow's Alexander Hamilton (because when isn't it) because exactly as you said, there is very little information about Rachel, and Ron walked so the rest of us could run. Here we go

Rachel was one of seven children

Five of Rachel's siblings died in childhood, leaving only our girl and her sister Ann. Ann went on to marry James Lytton after she fled Nevis (where they lived) due to an agricultural plague. Ann Lytton could not take in young Hamilton when he needed it, but she was the only blood relative on Rachel's side that he maintained contact with, and helped her out financially later on.

She was a child of divorce (basically)

Her parents had a very rocky relationship, and this possibly impacted her later relationships with men. Eventually, her parents separated, and she lived with her mother. She seems to have been very close with her mother, as they moved often together, or at least stayed close to one another.

She was previously married, and divorced

Before she met James Hamilton, she was married to man named Johann Lavien. Lavien was really horrible to her and financially and mentally abused her. When she ran away, Lavien sued for divorce, but long story short, Rachel didn't show up for court, and ended up being imprisoned for several years for adultery. The way divorce worked at the time was that a man could win a divorce case with just one accusation of adultery (especially if the woman didn't show up for court) but a woman needed several different, confirmed charges against the man to win. So, it would have been very hard for her to have won in the first place. Also, because of her no-show, she was forbidden from ever remarrying, hence why Hamilton was a bastard.

It is not incorrect to call her Rachel Hamilton and/or Rachel Faucette

While it is probably more respectful to use her maiden name, Faucette, there was a time where she lived as Rachel Hamilton, even though her marriage to James could not have been legally valid. While they lived in Nevis, James and Rachel lived with their two children as a married couple. However, it was when they moved to St. Croix that people recognized her as the former Mrs. Lavien, and tormented her and the boys with their illegitimacy.

She was a very independent woman

If Hamilton inherited anything from his mother, it was his quick thinking and independent mind. Rachel had her own income, and was able to provide for her two sons and tutor them after James left them. She was described by one of Hamilton's sons as "a woman of superior intellect, elevated sentiment, and unusual grace of person and manner. For her he was indebted for his genius." These are all words used to describe Hamilton later in life.

She supported other local women

In teaching her son in his earliest education, she chose a local Jewish woman to do so. Hamilton recalled being taught by her when he was small enough to sit on the table to read next to her. Towards her death, she was tended to by a woman named Ann McDonnell. In a society that was incredibly hostile to women, this was very important.

She died of an unknown illness next to her son, Alexander

She caught a fever in 1768, and was tended to by the aforementioned Ms. McDonnell and a man named Dr. Herring. She was given valerian, and bloodletting was used on Alexander (medicine of the 18th century is a whole other can of worms). Unfortunately, she did not recover, and died at nine o'clock on February 19, 1768.

Those are some of the most important and interesting facts, I believe, about Rachel Faucette. She is really one of my favorite historical figures, and I could talk about her and Maria Reynolds all day. I just love women who overcome the disadvantages they were given in life, I respect them so much. Hope this helps with your project!!!

#alexander hamilton#rachel faucette#rachel hamilton#history#amrev#asks#american history#amrev history#caribbean history#caribbean#womens history

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

any good hamdad anecdotes? i've heard of a few and they're always really cute

Absolutely. I'll spare you the sad ones.

The time Hamilton chose crabs over Angelica's pie and teasingly reassured her it wasn't because they moved it (Hamilton was prone to forgetfulness, it's likely Angelica taunted him about this);

Give my love to Angelica & assure [her] that I did not leave her pye out of resentment for her having changed its original destination; but because it was impossible to take it with us without abandonning a basket of Crabs which was sent to my care for Mrs. Rensselaer. It has always been my creed that a lady’s pleasure is of more importance than a Gentleman’s, so the pye gave way to the Crabs. It was a nice question, but after mature reflection I decided in favour of the latter. Perhaps as a Creole I had some sympathy with them.

(source — Alexander Hamilton to Elizabeth Hamilton, [1801])

Three days before the duel, Hamilton laid out under a tree with all his kids until it got dark;

The next day, Sunday, before the heat of the day, [Alexander Hamilton] walked with his wife over all the pleasant scenes of his retreat. On his return to the house, his family being assembled, he read the morning service of the Episcopal church. The intervening hours till evening were spent in kind companionship; and at the close of the day, gathering around him his children under a near tree, he laid with them upon the grass until the stars shone down from the heavens.

(source — Life of Alexander Hamilton, by John Church Hamilton)

While preparing for the Grange, camping out in the yard reminded Hamilton of his war days and he told the kids about war stories;

[D]uring the erection of [Hamilton’s] rural dwelling, he caused a tent to be pitched, and camp-stools to be placed under the shading trees. He measured distances, as though measuring the frontage of a camp; and then, as he walked along, his step seemed to fall naturally into the cadenced pace of a practiced drill. It was his delight in his hours of relaxation to return to scenes and incidents of his early life, when fighting for this country, and praying for its protection.

(source — Life of Alexander Hamilton, by John Church Hamilton)

Hamilton often slept besides his kids, and found amusement in playing with Holly;

I am here my beloved Betsy with my two little boys John & William who will be my bed fellows to night. The day I have passed was as agreeable as it could be in your absence; but you need not be told how much difference your presence would have made […] The remainder of the Children were well yesterday. Eliza pouts and plays, and displays more and more her ample stock of Caprice.

(source — Alexander Hamilton to Elizabeth Hamilton, [March 20, 1803])

Hamilton used to sing while Angelica played the piano;

Hamilton's gentle nature rendered his house a joyous one to his children and friends. He accompanied His daughter Angelica when she played and sang the piano. His intercourse with his children was always affectionate and confiding, which excited in them a corresponding confidence and devotion.

(source — Reminiscences of James A. Hamilton)

Hamilton used to take James on carriage rides when he had to travel places and gave him advice;

While we were living at the Grange I used to drive out with my father, and often accompanied him when he dined with his friend Gouverneur Morris. During one of these drives, soon after my conversation with my uncle, I told my father what I had learned, and made the suggestion which Mr. Morton had requested. He replied without hesitation, ‘‘No, my son; if I received a part of the profits of that business, I should be responsible for it; as I cannot attend to it, I cannot consent to receive what I do not earn.’’

(source — Reminiscences of James A. Hamilton)

Hamilton often helped his sons with their speeches, and once gave James a thesis on discretion as a subtle hint he was a bit too talkative;