Text

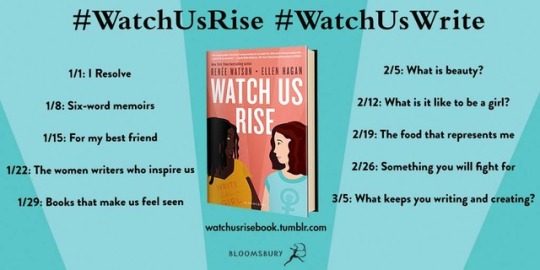

We started the year off making resolutions & reflecting. Join us next week for writing prompts inspired by #WatchUsRise. Follow #WatchUsWrite to participate!

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy New Year!

It’s been a long time since I’ve posted! A very long time. I’ve been busy with writing and I, Too Arts Collective. It’s been a full, full year! I’m back now and kicking off 2019 sharing writing prompts and inspiration to lead up to the release of #WatchUsRise, on February 12th. Join in and share your writing using the hashtags #WatchUsRise & #WatchUsWrite. Looking forward to hearing your stories!

-Renée

Renée Watson and Ellen Hagan’s new novel WATCH US RISE tells the story of two young women who will not be silenced. We’re celebrating the book by writing and raising our voices. Join us and some special guests for weekly writing prompts and inspiration starting January 1st!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seven Ways that Teachers Can Respond to the Evil of Charlottesville — Starting Now

by Xian Franzinger Barrett

Re-blogged from Rethinking Schools

So what do we do?

As we walk into our classrooms in the coming weeks, here are a number of concrete actions every educator can take to address the evil that was on display in Charlottesville. Some of these suggestions deal with Charlottesville specifically, but most will help educators address the longer term systemic challenges in our classrooms that foster white supremacy and other oppression.

1. Recognize that humanity and radical anti-racism is our curriculum for every subject. We should address events like Charlottesville and especially their root causes within our classes, and not just humanities. The irony that fields like mathematics and science claim to be neutral on social issues while at the same time exhibiting demographic differences that are mathematically impossible in a neutral system should be lost on no one. From the first day of class, we must demonstrate to students that the classroom is a space to bring all challenges and dilemmas they face, and that our curriculum will support them to build the skill and power to address those needs. Resources: Rethinking Schools has materials across all fields of student and age ranges. Teaching Tolerance has materials that focus on humanities, but can be adapted for any subject. To teach responsively to events like Charlottesville, the curated hashtag #CharlottesvilleCurriculum should be helpful.

2. Audit our own classrooms, schools and communities and then take action. We must assess and analyze the climate in every level of our school districts. We cannot effectively teach if we are unaware of how issues of race and oppression already exist in our spaces. For some of us, this may be difficult and expose feelings of guilt or helplessness. That is not the purpose of this work. What is, is. It’s better for us to know and understand reality than to be fearful that it might be exposed. Once we are familiar with what is happening in our classrooms, then we have the opportunity to see if it aligns with our values and make it so. Resources: We can investigate questions like the following: What is the racial breakdown of students, teachers and administrators in the school? How about the union leadership? How is discipline handled at the school, what is the racial/ability breakdown of those affected and is it from a carceral or restorative model? How do students interact in your own classroom and how does demographic impact participation and voice? Let’s examine all of these questions and more across intersectional lens of identity (race, class, gender, sexual orientation, ability, religious background, age, etc.)

3. Prioritize voices of color in every classroom. In all environments including within predominantly white institutions, it’s vital that we as educators counter the priority on white male voices in education. As I’ve written before, there are many educators who read almost exclusively white (and in some cases white male) voices in their own pursuits of knowledge. Most white students will have next to zero access to authors of color outside of the school environment. This not only limits their exposure to brilliant work, but contributes to a white supremacist mindset that voices (and the lives) of people of color do not matter. Resources: We Need Diverse Books, contact experts of color on various topics to address students (compensating whenever possible) Note: Do not spotlight individual students of color to be experts on issues related to our identity without our consent. (Yes, this happens a ton, no, I don’t want to speak for 1.5 billion+ Chinese people, and please stop doing this.)

4. Teach media literacy. Students must be equipped to read media for bias and develop their own understandings of news and events counter to a white supremacist narrative. The framing of black liberation groups as the equivalent to white terrorist organizations by the media is a cornerstone to the development of white supremacist movements in the U.S. Additionally, the inability to critically assess sources both in traditional and social media aides white supremacists groups in their recruitment. Resources: Critical Media Project

5. Create classrooms that students feel safe to share in, but are not conducive for the spread of hatred (we don’t get to debate each other’s humanity). Many classrooms either attempt to be “neutral” by ignoring politics for sterile content or allow open debate which usually focuses on whether the oppression or dehumanization of marginalized peoples is a good or bad thing. The former tends to softly side with the general white supremacy in American curricula, culture and assessments while the latter is not really a free exchange of ideas but rather an endorsement for students to use social inequities to bludgeon the victims of that inequity. Resources: Both the Illinois Safe Schools Alliance and GLSEN have incredible resources for developing classroom safe spaces.

6. Reject narratives of achievement and growth that embrace the tools and values of white supremacy. Much of our current definitions of achievement, growth and success tend to privilege culturally biased content knowledge while ignoring deep deficiencies in empathy and affinity for others. When we teach students to value a culturally biased test or we praise those who received far more resources without questioning that inequity, we are signaling to them that they deserve the visible benefits that inequities give them (or in the case of students of color, we deserve the oppression that those inequities represent). Resources: “Internalizing the Myth of Meritocracy”

7. Reach beyond our current spaces to learn and grow. The fundamental segregation of our national school system means that many white students are educated in predominantly white spaces by almost exclusively white teachers. In these environments, it’s challenging for white educators to access anti-racist pedagogical resources and conversations. Resources: #Educolor

To read the full article visit Rethinking Schools.

Photo credit: Joe Brusky/Overpass Light Brigade

Xian Franzinger Barrett is a part-time Special Education Teacher and part-time stay-at-home parent who previously taught Writing, Sexual Education, Law, History, and Japanese Language and Cultures in the Chicago Public Schools, He has received numerous teaching awards, including being selected as a 2009-2010 U.S. Department of Education Classroom Teaching Ambassador Fellow. He is a founding member of EduColor.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Renée! I just discovered your blog and I am so excited!!! Thanks so much for creating this resource. I am a researcher interested in similar things and I am starting a project at Raw Art Works later this summer. It's wonderful to see all that you have already documented; I can't wait to continue reading and learning from you. Raquel Jimenez

Hi Raquel,

So good to hear from you. I’m glad you’re finding this space a good resource. Hope you have a great summer at RAW. I love the work RAW does. -RW

0 notes

Video

youtube

Let America Be America Again

Let America be America again. Let it be the dream it used to be. Let it be the pioneer on the plain Seeking a home where he himself is free. (America never was America to me.) Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed— Let it be that great strong land of love Where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme That any man be crushed by one above. (It never was America to me.) O, let my land be a land where Liberty Is crowned with no false patriotic wreath, But opportunity is real, and life is free, Equality is in the air we breathe. (There’s never been equality for me, Nor freedom in this “homeland of the free.”) Say, who are you that mumbles in the dark? And who are you that draws your veil across the stars? I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart, I am the Negro bearing slavery’s scars. I am the red man driven from the land, I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek— And finding only the same old stupid plan Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak. I am the young man, full of strength and hope, Tangled in that ancient endless chain Of profit, power, gain, of grab the land! Of grab the gold! Of grab the ways of satisfying need! Of work the men! Of take the pay! Of owning everything for one’s own greed! I am the farmer, bondsman to the soil. I am the worker sold to the machine. I am the Negro, servant to you all. I am the people, humble, hungry, mean— Hungry yet today despite the dream. Beaten yet today—O, Pioneers! I am the man who never got ahead, The poorest worker bartered through the years. Yet I’m the one who dreamt our basic dream In the Old World while still a serf of kings, Who dreamt a dream so strong, so brave, so true, That even yet its mighty daring sings In every brick and stone, in every furrow turned That’s made America the land it has become. O, I’m the man who sailed those early seas In search of what I meant to be my home— For I’m the one who left dark Ireland’s shore, And Poland’s plain, and England’s grassy lea, And torn from Black Africa’s strand I came To build a “homeland of the free.” The free? Who said the free? Not me? Surely not me? The millions on relief today? The millions shot down when we strike? The millions who have nothing for our pay? For all the dreams we’ve dreamed And all the songs we’ve sung And all the hopes we’ve held And all the flags we’ve hung, The millions who have nothing for our pay— Except the dream that’s almost dead today. O, let America be America again— The land that never has been yet— And yet must be—the land where every man is free. The land that’s mine—the poor man’s, Indian’s, Negro’s, ME— Who made America, Whose sweat and blood, whose faith and pain, Whose hand at the foundry, whose plow in the rain, Must bring back our mighty dream again. Sure, call me any ugly name you choose— The steel of freedom does not stain. From those who live like leeches on the people’s lives, We must take back our land again, America! O, yes, I say it plain, America never was America to me, And yet I swear this oath— America will be! Out of the rack and ruin of our gangster death, The rape and rot of graft, and stealth, and lies, We, the people, must redeem The land, the mines, the plants, the rivers. The mountains and the endless plain— All, all the stretch of these great green states— And make America again!

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Best Selection of Multicultural & Social Justice Books for Children, YA, & Educators

For summer reading, Teaching for Change encourages young people to select multicultural and social justice books. Here are some recommendations of new (2016 and 2017) titles. For many more suggestions, see the full collection of recommended booklists and the We're the People summer reading list.

0 notes

Link

Whether you’re excited about the idea of more diverse books and authors, more #OwnVoices stories, or more diversity in genre fiction, you know you want to see more diverse books published and more diverse authors getting the recognition they deserve. Maybe you’re a Jacqueline Woodson fan who wants more authors like her, or you’re excited about diverse characters in comic books. Publishers can feel like a monolith instead of book-loving individuals coming together, and you might not know how — or where —they’re listening. Sure, you liked a post about Pride Month reading lists, but does your favorite author know you actually read their book? And last month, you bought a book with an autistic protagonist, but then realized the representation wasn’t all that great and now you’re looking for something by an autistic author. What can you do?

179 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Young Adult Authors Renée Watson & Jason Reynolds at the Langston Hughes House discussing why they write.

For more information on I, Too Arts Collective visit www.itooarts.com

1 note

·

View note

Link

#PiecingMeTogether#reneewatson#LessonPlans#intersectionality#SocialJusticeEducation#yalit#diversebooks

2 notes

·

View notes

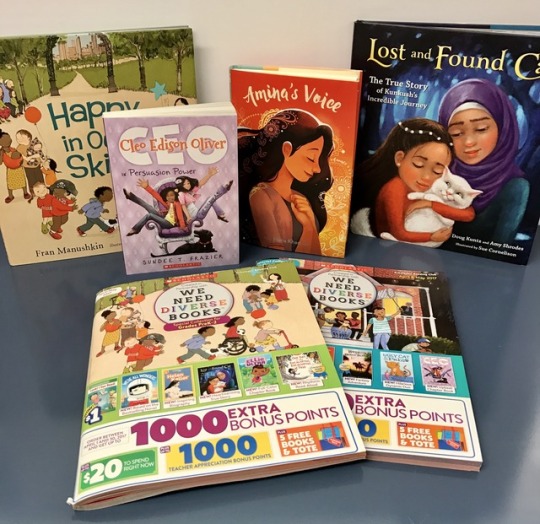

Photo

The Scholastic Reading Club April We Need Diverse Books flyers are here! You can find the full collection for our younger readers (Pre-K – 2nd Grade) here and our older readers (3rd – 6th grade) here. If you’re interested in purchasing from these flyers, here’s how to get started:

PARENTS: Scholastic Reading Club is a classroom experience, which means you place orders through your child’s teacher. When you order, you’re earning free books and resources for that class! For more information or to link up to your child’s teacher, click here: scholastic.com/readingclub

TEACHERS: Whenever you place orders with Scholastic Reading Club, you’re earning free books and resources for your own classroom library! Log in to your account, or sign up for a new account here: scholastic.com/readingclub

149 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Hanging around people who are dreamers and who are about something has been motivating for me. We rub off on each other and keep each other accountable, and I think that’s really important.

Renée Watson, founder of the I, Too Arts Collective, whose most recent young adult novel, PIECING ME TOGETHER, is out now.

Listen to the full episode here, or download it on iTunes or Stitcher.

(via firstdraftwithsarahenni)

24 notes

·

View notes

Link

An important resource for educators, parents and young readers.

“We see the news stories about refugees almost every day. We hear the true but almost unimaginable accounts of families forced to flee their homes, their homelands, their entire lives. While we may wish that our children didn’t have to know about such trauma, the facts are that it’s real and very present — and there are countless children actually living it. Stories can facilitate dialogue and promote healthy communication on this difficult topic, help to foster empathy and understanding, and even inspire young readers to take action to ensure safe and welcoming environments in their own communities. Here are a few titles that can help...” -Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich

0 notes

Text

All American Boys: an interview with Jason Reynolds & Brendan Kiely

by Renée Watson

As an author and educator, I ask myself: How do I create space for young people to practice empathy, to think about worlds other than their own? How can young readers experience literature as a bridge, a map, a window, a mirror? How can young adult novels be used in the classroom to ignite conversations about social issues? Now, more than ever, these questions are weighing on me, given the divide in our nation over the 2016 presidential election.

At a recent social justice workshop for educators, one teacher asked me, “How do I get my students to care?” Another asked, “How do I begin the conversation?” An administrator wanted resources for dealing with her own assumptions and stereotypes.

One book I recommend over and over is All American Boys.

Authors Brendan Kiely and Jason Reynolds were on a book tour with fellow Simon & Schuster authors when a Florida jury found George Zimmerman not guilty in the 2012 death of Trayvon Martin. The two authors realized they had more in common than writing for teens—they were both frustrated, angry, confused, and saddened about the ongoing killing of unarmed Black men and women. In August 2014, when police officer Darren Wilson killed Michael Brown, another Black, unarmed teen, Brendan wanted to do more than talk about it. He wanted to write about it. He asked Jason to collaborate with him. Jason is Black, Brendan is white; they wanted the book to reflect the difficult conversations necessary to overcome the chasms created by racism.

Together, they wrote All American Boys, a young adult novel told in alternate chapters by high school classmates Rashad, who is Black, and Quinn, who is white. Rashad is wrongfully accused of shoplifting and is assaulted by a police officer—he is beaten so badly he is hospitalized. One eye is swollen shut and he has a broken nose and broken ribs. Quinn not only witnesses the assault, he knows the police officer personally. When a video of the attack goes viral, their classmates take sides and Rashad and Quinn are forced to think and talk about race in ways they hadn’t before.

I read the book in one night.

After reading All American Boys, I wanted to get it into the hands of the young people I know and every educator, too. I believe this book can be a vehicle to help young people and educators openly discuss racism, white privilege, and stereotypes. It’s more than a book about police brutality. It’s a book about two teen boys finding out who they are, what they believe, and how sometimes that conflicts with the lessons they’ve learned from their parents and their communities. It’s about taking risks and moving past being a silent bystander or a passive ally to being an active agent of change.

Talking about why he writes, Junot Díaz says: “If you want to make a human being into a monster, deny them, at the cultural level, any reflection of themselves. And growing up, I felt like a monster in some ways. I didn’t see myself reflected at all. I was like, ‘Yo, is something wrong with me? at the whole society seems to think that people like me don’t exist?’”

I am thankful for writers like Kiely and Reynolds, who are writing stories that are not only mirrors for individual readers, but for society as a whole. Our society could become a monstrous place without a reflection of itself. I am honored to share this interview.

Renée Watson: What do you say to teachers who are hesitant to use All American Boys out of concern that police brutality is too controversial for the classroom or who think the novel is anti-police?

Jason Reynolds: I say:

The novel is not anti-police. It’s just not. But since we’re on the topic of anti-police, I wish people were more pro-kid. Just saying.

Running from reality has never done anyone any good. This is the world these young people are living in. This is their world to shape, their world to change.

Either you, the teacher, are going to be on the side of the world shapers, or on the side of apathetic destruction. Whoa. That sounds heavy. And you know what . . . it is.

My experience has shown me that all you have to do is start the conversation, then step back and facilitate. You’ll be surprised at how ready so many young people are to talk about this. Create a safe space, one that might even make you uncomfortable.

Brendan Kiely: Jason and I have traveled the country and spoken to thousands of students in very diverse educational environments, from wealthy, predominantly white private schools to underserved public schools in predominantly Black and Brown neighborhoods, and all types of schools in between. In every school we visit, we ask students if they are aware of the cultural conversation surrounding police brutality, and nearly 100 percent of the students raise their hands. As a teacher, I can’t pretend this isn’t on their minds. It is. And more importantly, most of these students want to know more about the context, why it is happening, and how they can better understand it all. We wrote All American Boys to provide students, teachers, librarians, and all communities with a tool to help grapple with these tough conversations—engaging in the hard realities that a classic text like To Kill a Mockingbird addresses, but within a contemporary and more relatable context. The book isn’t anti-police at all—it is a story of how to better see the deeper humanity (in all its beauty and ugliness) in everyone involved in moments like these.

RW: Police brutality cases are often talked about in terms of right/wrong, villain/victim. The characters in your book are layered, and there are no simple boxes they fit into. How did you balance authentic cultural identity while avoiding stereotypes? Why was this important to you?

JR: For me, it was hard. So, so hard. Because there was nothing I wanted more than to use this book to honor the victims of police brutality with complete abandon. To further distill the conversation to a Black and white, anger-filled narrative, because quite frankly, that’s how I feel emotionally most of the time. Angry. Frustrated. But my emotions, while true to me, most times exist in a vacuum, potentially keeping me from further exploring fact. Does that mean racism and brutality are figments of my emotional imagination? Of course not. It’s real. It’s all real. But it gets more complicated and messy when the layers get pulled back. So, I told myself, “If I’m going to be honest about the emotional backdraft, I have to also be honest about everything else.”

BK: The reality is clear and unequivocal: Too many unarmed young people of color have been brutalized or killed by police officers. Many of the individuals who perpetrate this violence, however, may not consciously recognize the injustice they perpetuate. Life, as in All American Boys, is messy, and often people who think they have the best intentions act with devastating unconscious bias. If Officer Galluzzo considered himself a white nationalist or consciously brutalized Rashad because Rashad is Black, the story wouldn’t address our country’s deeper problems of systemic racism, which exist in law enforcement, healthcare, education, and many other institutions. Galluzzo’s unconscious bias mirrors the unconscious bias that fuels the systemic racism in our country.

RW: In All American Boys, Quinn begins to question and unpack his white privilege. He comes to many revelations throughout the story. One moment that stands out to me is when he is talking about his decision to attend the protest rally. He says: “Because racism was alive and real. . . . It was everywhere and all mixed up in everything, and the only people who said it wasn’t, and the only people who said, ‘Don’t talk about it’ were white. Well, stop lying. That’s what I wanted to tell those people. Stop lying. Stop denying. That’s why I was marching. Nothing was going to change unless we did something about it. We! White people!”

Brendan, why did you include this scene? What is the “something” that white people can do?

BK: Too often when I was growing up, conversations about race and racism were lessons about how hard people of color have it now and have always had it in our country. That is true, and we must continue to talk about and learn more about this reality. But it is only half the story—if some people are being systematically disenfranchised and disproportionately brutalized, other people are being systematically empowered and disproportionately protected.

This less-often discussed side of the story is the story of white privilege. Quinn grapples with it because he wants to better understand the whole story. As he learns more, he realizes that by ignoring the problems of racism in his community he is perpetuating those problems. That it is part of his privilege. He’s not malicious, he’s a sweet teenager who wants the best for everyone, but he comes to realize that unless he stands up against the racism, especially as a white person, he is harming the very people close to him—his friends and teammates and classmates who are people of color.

White people can listen first, hear the truth of experience from people of color; they can speak to other white people about what they hear and ask other white people to listen and learn more; and then they can join the chorus of people who are already doing work to combat injustice in our society and who already have experience in this struggle. This is Quinn’s journey, the story he has to share, particularly with other white people.

RW: What strategies do you recommend for white educators who want to talk about racism in the classroom?

BK: I worked in a high school for 10 years before becoming a full-time writer. I am forever grateful to colleagues and friends who introduced me to workshops and professional development opportunities that helped me think more critically about systemic racism, my own unconscious bias, and strategies for being a more inclusive and better teacher to both white students and students of color—especially as a white man. Organizations like the Anti-Racist Alliance, the CARLE Institute, Border Crossers, and the White Privilege Conference were all instrumental in helping me learn more and network with other teachers who were interested in learning how to talk about race and racism in the classroom. I also spent a lot of time listening to students and faculty of color and not arguing another point or side—just listening. It always amazed me how much more my students would learn from me after I spent time listening to them and their life experiences and needs. And finally, I always like to add that I made and continue to make many mistakes. I wish I didn’t, but I do, and I try hard to learn from my mistakes. We tell our students to try to tackle things they find hard, to try and fail, try again, fail again, and fail better. I think we have to do the same, especially when we are talking about race and racism. There’s too much at stake to be afraid of failure. We must all try, and when we fail, fail better the next time.

RW: Jason, in your School Library Journal’s SummerTeen keynote speech, you said: “When it comes to the pain and grief of young people, adults tend to be the most dismissive. . . . We need to help them grieve or cope. . . . It is our jobs as adults to usher young people into their own power.” How can educators “usher young people into their power?” Can literature play a role?

JR: The first thing adults have to do is listen. Listen, listen, listen. Don’t assume that a young person’s pain isn’t as big, as heavy, as the pain of an adult. If anything, it’s greater, because there’s a good chance that it’s a new pain—an uncharted territory that adults have trampled time and time again. But if we ask a few questions, simple questions like “What’s the matter?” or “How do you feel?” and then allow young people the space to speak freely, that, in and of itself, is powerful. The ability to be unfixed, not OK, the ability to be wholly human in the presence of an “all-knowing” adult creates an underestimated and grossly underrated agency in kids. What literature does is serve as an avatar—text as a human companion, a warm hug, a familiar face with a relatable experience in those moments when adults seem hard to reach.

RW: Art is a big part of the book. From the visceral “Rashad Is Absent Again” graffiti on the school steps to the private art in Rashad’s sketchbook, there’s a sense that art is a way to process injustice, perhaps to stand up against it. Do you see your writing as activism? What artists (music, visual, literary, etc.) do you recommend for teachers who want to explore art as activism?

JR: I’m not sure I view it as activism. I’m a bit reticent to call it that only because of all the “active” activists, who have dedicated their lives (and sometimes bodies) to the fight for justice. That doesn’t mean that I haven’t dedicated my life to the same fight, but when I think about my art, I think of it as . . . art. Art within the Black tradition, a tradition devoid of the luxury of being flowery and masturbatory. But I think we have to be careful about throwing around “activist.” I consider myself aware and intentional.

Art I recommend for teachers who want to explore more of this kind of work: James Baldwin (all of it), TaNehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, Toni Morrison, August Wilson, Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni; the art of Kara Walker, the photographs of Lorna Simpson; the music of William Grant Still, Bob Dylan, and Tupac; the dance of Alvin Ailey and Bill T. Jones; and so much more. Frankly, anything made by a person of color is politically bent by default. To me, our lives, our existence in any space in this country, are implicitly political. Just being is a statement. ◼

Reynolds, Jason, and Brendan Kiely. 2015. All American Boys. Simon & Schuster.

*This interview was published in Rethinking Schools, Winter 2016-17

0 notes

Text

#WeNeedThisSpaceBecause

Author Tracey Baptiste talks about why preserving the legacy of Langston Hughes is important

We need this space because as Hughes gained success as an extraordinary poet, he remained unapologetic about being a Black man. He brought the viewpoint, language, and desires of Black people to everyone who read his poetry. In my field, children’s literature, there are more people being published writing about Black people and culture than there are Black authors and illustrators being published. Some outsider portrayals are stereotypical and downright racist. Hughes wrote about a culture he lived and loved. It’s a lesson for all of us to dig deeply into whatever culture we put on the page. That he did this work in this house makes it a treasure worth preserving.

We need this space because Harlem was not just a cultural hub, it was a place where people could live and be freely themselves, without the worry of racism they felt elsewhere. It is a tragedy that 100 years after Black people began to shape Harlem into a mecca, it is getting chipped away as a result of gentrification. It’s a matter of money—of not having the wherewithal to maintain our cultural spaces. Fortunately, this is one space we may be able to save. I am thrilled by the idea of young people learning to write in the same space that Hughes did his work. This project is about reclaiming both physical and creative space. Artistry is not only about having a place to learn and work, it’s also knowing there is freedom to create. The erasure of Black Harlem may come despite our best efforts with this space, but imagine artists having a space where they can create, and take that creativity anywhere. Gentrification may happen in Harlem, but this project is about making sure that gentrification doesn’t also happen in the hearts and minds of our artists.

...

About Tracey Baptiste

Tracey Baptiste is the author of the middle grade fantasy novel The Jumbies (with a sequel coming soon), the contemporary YA novel Angel’s Grace and 9 non-fiction books for students in elementary through high school.

She is a former elementary school teacher and is on the faculty at Lesley University’s Creative Writing MFA program.

To learn more about I, Too, Arts Collective & the #LangstonsLegacy campaign, visit our campaign page.

5 notes

·

View notes