Text

Taken from my main blog to get this one caught up.

Kyidyl Explains Bones - Part 7.1

(these are all under the kyidylbones tag.)

Would you guys like another bones post? Of course you’d like another bones post! =D

Today we’re gonna talk about…

TEEF…I mean TOOFS….I mean…..teeth.

This one got away from me a bit, lol. Ok there’s such a huge amount of info you can learn from teeth that this might actually take me two posts to cover, but we’ll see. There aren’t really any special ethical concerns I can think of here, but there’s a lot of background info, so I’m just gonna get to the intro.

Introduction to Teefs

So, first of all, contrary to popular tumblr joking lore, teeth aren’t bones in your mouth. They aren’t connected to your bones, they don’t grow from your bones, and they aren’t made of anything even vaguely resembling the same tissue as the bones. So here are some random facts about teeth in no particular order:

Teeth are the strongest tissue in your body. They last incredibly well and preserve well in the archaeological record. They’re difficult to destroy

Human teeth are some of the strongest teeth on earth, with some of the thickest enamel. Most animals have a way of ensuring they can eat for their lifespan, and this is ours in combination with dentin.

Human children have 20 teeth, called milk teeth or baby teeth. Human adults have 32. The difference is that adults have wisdom teeth/3rd molars and premolars. Children only have incisors, canines, and two sets of molars.

There are several ways of naming teeth, and they’re not consistent. I’m gonna use the one I was taught to use, and that’s this: location –> tooth –> number –> side. Which means, for example, an upper left big incisor would be upper incisor 1 - left. It’s abbreviated UI1 - L or UI1L (honestly the order isn’t that important here.). Each side has this on the upper and lower: two incisors, one canine, two premolars, and three molars. It’s called a “2-1-2-3 dental formula”. Other mammals have a different dental formula.

There are two new terms you need to know for this one: lingual and buccal. The lingual side of your tooth is the side by your tongue (I remember it bc lingual = language = talking = tongue.), and buccal is the side by your cheek. Also sometimes you’ll see the term “cheek teeth” and it means molars and premolars, but personally I find the idea of my cheeks having teeth to be creepy and weird so I don’t use it. :P

The bone in the tooth socket has a special name: alveolar bone. This is because it has a slightly different texture and behaves a little differently and because we need a word for “bone around the teeth”. Socket is just the hole.

Your teeth are held in place by the creatively named substance cementum. It does degrade over time and with poor tooth maintenance or damage or substance abuse, and that’s why your teeth get looser in the sockets as you age.

Before the advent of farming, human teeth had far fewer cavities (carries). This is because there was less sugar & carbs in the diet and the bacteria in your mouth thrive on sugar & carbs.

There are two kinds of tooth adaptations: functional and cosmetic. Functional is connected to diet, and cosmetic is just the quirks. They’re not even really called cosmetic, but I literally can’t remember the word, sooo…anyway the cosmetic stuff changes extremely slowly and is used to study evolutionary and ethnic relationships.

Ok, so what can you learn from teeth? Well, strap in kiddies, because it’s a LOT.

Keep reading

#science#anthropology#archaeology#archeology#bioarchaeology#humans#human remains#human bone#educational#teeth#my content#queue#forensic anthropology

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taken from my main blog to get this one caught up.

Kyidyl Explains Bones - Part 6

(All of these are under the KyidylBones tag.)

Age Determination

Well, age at death anyway. I’m gonna put this warning up front:

Today’s post will contain pictures of the skeletons of children. This is something that a lot of people, even those who think they won’t be bothered, find upsetting. This goes double if you actually have children. This post will also include frank discussion of child death.

You have been warned.

So what is age determination? Age determination isn’t the process of figuring out how old a set of remains is, it’s the process of figuring out how old the individual was when they died. Because of the sensitive nature of the topic, I’m putting everything behind a cut today.

Keep reading

#science#anthropology#archaeology#archeology#bioarchaeology#humans#human remains#human anatomy#educational#age determination#my content#queue

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taken from my main blog to get this one caught up.

Kyidyl Explains Bones Part 5

(These are under the KyidylBones tag.)

How to dig up dead people.

So, in my Kyidyl Does Archaeology series I talked a bunch about how digging up places was different than digging up people. And you don’t have to read that to understand this, but it might be a little easier for you because I’m not going to re-address the same basics I covered there.

Ethical Stuff: So is digging up dead people ethical? I mean, I think so if strict rules are followed, but honestly the POVs here are as different as people themselves are. Some cultures routinely dig up their own dead and do all kinds of things with the remains. I wish they wouldn’t but, hey, that’s just me. I respect that their culture and choices aren’t the ones I’d make. It’s part of being an anthropologist of any flavor. And, like that one post implies, there really isn’t much of a different between grave robbing and archaeology. The biggest difference is the care we take, the respect we try our best to show, and the purposes to which we put the remains. However, there is a difference between exhumation and archaeology. General rule of thumb: if there’s someone living still that would have first-hand experience of them or if they still exist strongly in cultural memory, it’s exhumation. There’s no hard and fast number of years where it moves from exhumation to archaeology. Sometimes it’s the context that makes the difference. For example, Richard the 3rd’s bones were excavated from that carpark. If they were removed from where they were reinterred, then they’d be exhumed. But the TL;DR of it is that digging up people is incredibly ethically complex and you have to do your best to be respectful. If you aren’t the type of person who can really put yourself in someone else’s shoes and be ok with respecting the desires of a specific culture regarding their own dead…then archaeology is not the right area for you, and that goes double for bioarch. These people had lives and were loved and valued by those around them, and you need to be sensitive.

The legality of digging up human remains also varies wildly from country to country. In the US, we adhere to NAGPRA. If you want a primer on what NAGPRA is and how it works, you can check out this post that I made.

Also a quick reminder that we don’t name the individuals. They had names and you don’t get to give them a new one.

Beyond this cut there be pictures of human remains.

Keep reading

#science#anthropology#archaeology#archeology#bioarchaeology#humans#human anatomy#human bone#bones#human remains#queue#my content

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taken from my main blog to get this one caught up.

Kyidyl Explains Bones - Part 4.2

(These are all collected in the KyidylBones tag. Additionally, this is the second half of part four - please read the first half here, especially if you have questions or comments about the ethics of what I’m talking about here. I’m going to be leaving that out as this is a continuation of that post.)

Since I’m skipping the talking and ethical statements in this one, let’s just get right into the bones. As a reminder, this is about race determination in skeletal remains.

Keep reading

#science#anthropology#archaeology#archeology#bioarchaeology#human bones#race#human anatomy#human remains#forensic anthropology#bones#queue#my content

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taken from my main blog to get this one caught up.

Kyidyl Explains Bones - Part 4.1

(These are all under the KyidylBones tag.)

Sorry for the pause in this series….it’s difficult to produce these when I don’t have my meds and I ran out. But I refilled them, so now we continue!

Anyway, today we’re covering something that is, if possible, even more complex and thorny than sex determination: race determination.

Ethical Statement: Race is not a biological reality. Now, hear me out before you run away. Race isn’t a biological reality, but that doesn’t make it *not real*. Race absolutely is real and effects how society interacts with an individual. But between these two statements, which gives you more information about a person:

“I’m white.”

“I’m white and I live in 21st century America.”

The second, obviously. Because skin color tells us virtually nothing about an individual. Ethnicity - where they’re from, what social groups they might have interacted with, how society might have treated them, etc. - is a lot more valuable than knowing the color of their skin. HOWEVER. And this is a big however. However, in a modern person’s understanding there is a lot of crossover between race and ethnicity. And, in fact, as with sex, when a set of remains is being evaluated for identification we must at least attempt to identify the race because that’s how they’ll be categorized in the missing persons’ database. And identifying race in archaeological remains helps us track human social interaction and migration because ethnicity doesn’t really survive intact outside of grave goods (and those may or may not be present.). And, yes, if you’re wondering, DNA tests can confirm a lot of the data that we attempt to glean anatomically but for the most part we don’t have the money to do DNA tests on remains, or they don’t have anything surviving that has intact DNA (you can have a nearly complete set of remains and not have any DNA because damage to the outside surface of the bone and/or teeth causes damage to the DNA inside it and causes it to break down.).

So since race isn’t a biological reality but it is a social reality, it’s helpful to attempt to determine the race of the individual in question. And, obviously, that’s before you even take into account that people interbreed all the time. So how can we begin to do this with any degree of accuracy, since the classifications are social and not biological?

Short answer: we can’t, but we try anyway because of the reasons I mentioned above. And there’s something that I should have added to the post about sexing a skeleton but I didn’t because I’m human and I make mistakes sometimes: we don’t ever refer to a set of remains as definitively X sex or definitively X race (well, we do when we’re with other scientists who have an understanding of what I’m about to say for brevity’s sake.), we say “this individual has _____ features consistent with or indicative ______ race/sex.” Sometimes the features are very stereotypical and we’re fairly certain that they definitely are X race or sex, but other times they’re not. And the markers that we use are based on averages, so obviously within those averages there’s a huge amount of variation - that’s why we use so many different markers. So like with any science, it’s good to remember that there’s always room for change and that it’s all theories.

Also if you want to do some reading on it, you’ll see that these determinations are still hotly debated among anthropologists because we are well aware of how racist and shitty it all is and we hate that we have to engage in it but at the same time it’s important for the reasons I mentioned above, so we’re always trying to find new ways that are more accurate and less racist.

Categories

Essentially, we have a list of anatomical features that tend to be similar in geographic regions and we go through these features and grade them according to which race category we think they most closely match. There are three, sometimes four, categories:

Caucasoid/White/European depending on what reference you’re using.

Black/African (Outdated term: Negroid. We all hate it but it’s in the literature, especially older stuff, and if you do any reading you’ll run into it.)

Asian (Outdated term: mongoloid. Same as above.) - This includes Native Americans because their anatomy is so similar to Asians, especially eastern asians, that it’s well-nigh impossible to distinguish without a DNA test. Mostly we know based on the context the remains are found in.

Aboriginal - This is specifically for indigenous pacific groups, especially in Australia and Aotearoa (New Zealand. In this lab we use the indigenous name.). They have some interesting anatomical differences that are only found in that area of the world. Obviously it’s not going to be as used in the rest of the world tho so it’s often not covered. Plus their biggest differences are brow bone size and tooth size so while it’s different it’s not AS different as the other three categories.

So as we go through the markers, we add them to these groups and then at the end average them out to see which one the remains most resemble.

The Anatomy

There are a lot of markers of race on remains, and more are being studied all the time, so I’m going to cover the most common ones in the interest of length. Also, pretty much all race markers are on the skull, so I’m not really going to get into the rest of the skeleton, even tho there ARE markers on the post-cranial (means exactly what you’d think: not skull.) skeleton. And like with physics ignoring friction for the sake of illustration, we’re going to ignore cultural changes to the bones ala the slavic squat and pathologies. We’re gonna start in on the bone pics in a hot second, so time for a cut.

Keep reading

#science#archaeology#archeology#bioarchaeology#my content#skeletons#bones#human bones#humans#human remains#education#queue#race#race determination#skeletal anatomy

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taken from my main blog to get this one caught up.

Kyidyl Explains Bones - Part 3

Well, I had this halfway done and then TUMBLR ATE IT, so let me start again. UGH.

(These posts are collected under the KyidylBones tag. Do with that information what you will, lol.)

So what are we getting into today? Sex determination!

Ethical Note: I’m adding this bc not everyone who sees this post saw my post yesterday and this is important info, especially on Tumblr. Anthropologists of all stripes are well aware that sex and gender are extremely complicated. Trust me, we know. But we still do sex determination for a few reasons. First, because missing persons databases are arranged on a male/female binary, and if we’re comparing a set of remains to that database to identify the remains then we need that info. Second, demographic info for populations that have disappeared is important, even if those populations are historical. This might shock you (<–sarcasm), but written records are usually either lacking or inaccurate. Third, if we know the sex of the skeleton we can compare that to the grave goods and learn some interesting cultural things, including possibly being trans, because none of the signs of being trans survive physically in the skeleton. So I am going to be using male/female binary language, but it isn’t to exclude the wide variety of sexes and genders that don’t exist on that binary, it’s because it’s what I’ve got to work with. And if you have questions about this, feel free to ask, but please be respectful.

Alright, so there are some vocab words for today’s post and I had them all nicely written out in an easy to read paragraph, but it got eaten, so I’m just gonna present them in list fashion this time:

Characteristic - All physical markers of human variation exist on a spectrum because humans are varied and we invented the categories to begin with. If something is characteristic of, say, a male? It means that it is very, very distinctly male. It matches the stereotypical expectation of what you’d see in a male. It’s a standard for an obvious example of a given thing.

Landmark - A landmark on your bones is a feature of the bones that is always in the same place. We use this to help us identify a bone and to help us know what side it is on. IE, your lesser trochanter is a bump on your femur (thigh bone) that is on the inside towards the back. It’s always in that spot, so we know which direction it should face and ergo which side it would be on. Landmarks are unique to the bone in question.

Foramen - A hole on a bone. The big one in your skull that your spinal cord goes through is the foramen magnum and it literally means big hole. But there are a lot of little ones all over your skeleton so your nerves and blood vessels can do to your skeleton what the weirwood did to Bryden Rivers. I said what I said. ;)

Bilateral - Both sides. Humans have bilateral symmetry and so one side is symmetrical (externally and WRT your skeleton, but not always your organs.) to the other. You can split us down the middle and the two sides are basically the same.

Ok, so there’s another set of terms that you need to know, but I’m going to be copying and pasting this into every post going forward so I’m making it separate. Anyone who works with any kind of anatomy uses these terms to be very specific about the location of something on the body. They are:

Anterior/Posterior - Front and back respectively. I remember them because my mom used to say posterior when she didn’t want to say butt, and because A comes before P the way front comes before back. Sometimes people say dorsal and ventral, and I remember that because a dorsal fin is on a whale’s back.

Proximal/Distal - Near and far vertically in relationship to the center of your body. I remember it because one end of the bone is in close proximity to me and the other one is distant.

Medial/Lateral - Near and far horizontally in relationship to the center of your body. I remember it because medial is closer to the middle of my body, and lateral isn’t medial. Also, if you are reading left to right L comes before M and you’d get to a lateral body part before a medial one.

So, where to begin? How do we know what sex people were assigned at birth from just their skeleton? Let’s start with what everyone is most familiar with:

The Pelvis

Keep reading

#science#anthropology#archaeology#archeology#long post#human bone#human remains#sex determination#skeletal features#education#queue#my content#bioarchaeology

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taken from my main blog to get this one caught up.

Kyidyl Explains Bone - Part 2

(these are collected under the KyidylBones tag bc I have the sense of humor of a 13 year old boy.)

I decided to do this today since the other part was basically like boring intro stuff and that’s not really what you showed up for. So today’s topic is:

Human vs. Animal

Anthropology and archaeology departments the world over are often brought random bones people find to ID whether they’re human or animal, so you might be wondering how do we know the difference? Well…it takes practice. And, honestly, if the pieces are too small we can’t tell without microscopic analysis of the bone structure, but most of the time we can tell.

Human bone is very unique. Our anatomy is unique because we’re the only living members of our genus Homo and the anatomical adaptations of Homo are unique among animals. The weird combination of big brain, walks upright, fine motor control, and used to live in trees is just…weird. Our internal microscopic structure is different than that of any other animal. We grow differently than any other animal because our young take so long to mature and are born so helpless. So anatomically…we’re unique if you know what to look for, but fragmentary remains are super common so you can’t do it by anatomy alone.

One piece of info that’s important. Bone is made of two components: collagen and minerals. Squishy bits and crunchy bits respectively. And, yes, if you’re wondering…scientists DO sometimes remove these bits for Reasons ™.

Context!

Where did you find this thing? Was it a single bone in a patch of woods in your backyard? Probably animal, but not always. In a pit at a dig with burned animal bones? Probably not a human because people don’t toss the remains of their friends and families in with dinner. Across cultures people treat their own dead differently than their animal dead or their food. So if you find it with the food? 99% chance it’s animal, even at a disturbed site (tho it’s not *impossible* to find people in with animal, especially in caves, very disturbed sites, or very old sites. With very old sites you have to get comfortable with the idea that sometimes people were food and it wasn’t even that uncommon.)

Texture!

I’m doing this one first bc I can’t give you pictures of texture so it can go outside the cut. That microscopic structure I mentioned and differences in bone growth all lead to a different texture in human bone. Now, I want to preface this by saying: this varies with the age of the bone and the age of the individual and the environment in which you found it. But human bone tends to be a bit less….greasy than animal bone. I don’t know how else to describe this, because understanding the difference in texture is literally something you can only do by handling them, but I’ll do my best.

See, animal bone found in association with humans is normally put through some kind of alteration process. Cooking, smoking, etc. Human bone sometimes is - after all, people cremate their dead or dry them out or mummify them or eat them all the time - but buried bone tends to be drier in texture than animal bone. Animal bone won’t leave greasy stains or residue, but it will feel smoother - less porous. As humans (and animals) decay, the collagen goes first and leaves behind the minerals. This happens at different rates for different organisms in different conditions, but human bone that has been buried will have a different texture than animal bone, and it will be slightly less smooth or greasy (listen bone grease isn’t GREASE grease it’s just like a way of talking about how dried out it is. Older = less grease. New things will leave like food grease on your fingers.). But after you’ve felt it a few times - buried human bone has a different texture than animal bone.

Color!

Human bone is a different color from other kinds of bone. It’s similar, but not the same. And! Unless it has been bleached by the sun (something I’ll touch on more when I do the damage post.), it’s not white. Not when it has been defleshed naturally. So halloween decorations? Yeah, all the wrong color. Anyway, this is where we start to get into images, so I’m going to start putting things behind the cut.

Keep reading

#science#anthropology#archaeology#archeology#bioarchaeology#human#human bones#human skeleton#human remains#long post#my content#educational#queue

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taken from my main blog to get this one caught up.

Kyidyl Explains Bone - Part 1

(These posts will be collected under the tag KyidylBones because I have the sense of humor of a 13 year old boy. Also, I’m going to start cross-posting them to my science side blog @science-of-anthropology in an effort to like give people a place to go if they’re just here for these posts and not for my other random thoughts. That blog also contains a lot of decent info from the days I was premed and taking premed physical science classes.)

Intro and Ethical Considerations

Ok, all you weird nerds out there (<3), how’s your day going? Good? Are you ready to hear me ramble about one of my favorite things on earth? Well, then gather ‘round ye old tumblr fire. We’re gonna learn about *people*! Because all the stuff I taught you before was stuff you basically learn in anthropology undergrad and in a field school. But! I *specialized*. I have secret powe–*coughs* I mean, a special interest. See, my favorite topic in the whole world, the one on which I will ADHD infodump for DAYS about if you let me, is the intersection of human evolution and culture. My ultimate goal is either to work in a museum, or be a scientist that studies this. That’s why I went out and got a masters.

A bioarchaeology masters not only taught me how to dig up people, but a whole HOST of other things related to people and digging (Like genetics and using drones to survey an area for digging.). But before we can get into the details, there’s a few things you have to understand. First:

On sex, race, ethnicity, and gender

Anthropologists of all kinds are well, WELL aware that these 4 things are extremely fraught and extremely complicated. Probably more aware than any of the other sciences. But, when you learn to identify skeletons you learn to do it based on sex and race for a couple reasons:

1. When identifying a body for the police department, their databases are entirely based on these identifying characteristics. A lot of forensic anthropologists work with the police to identify remains. If we can’t pick out demographic qualities then we’d never match them up to people in the missing persons database who are listed along a sex binary and racial categories. But believe me when I tell you we all do it under duress and in annoyance because we know how complicated these things are for people.

2. When dealing with populations that are gone and can’t tell us what they identified as, we arrange them by sex and race to make some sort of sense of the demographics of an area. This is how we know, for example, that people from Africa intermingled early and often with people from Europe. Being able to ID these markers on a skeleton is faster and cheaper than DNA tests and often the only method available, especially in prehistoric populations.

So I will be discussing features on bones in these terms, but understand that it’s not my way of excluding trans people. We, as of yet, just have no good way of *identifying* trans people in the archaeological record.

And second:

Ethics

Ethics is a huge and thorny topic so I’m going to only make a couple notes here. I bounced this series around in my head for awhile and the reason I didn’t do it sooner is that despite having human remains in my possession for legitimate scientific reasons, it’s extremely unethical for me to post pictures of them on the open internet. The same goes for the tons of pictures I have of human remains from my masters studies. To that ends, the images I’ll be using will fall into one of four categories: images from my textbooks, images on the public web that are available for educational use, and images of Bone Clones, and my own image of damage patterns on animal bones. This is also a warning that, yes, there will be images of human remains here. I’ve decided, though, that when a post starts to contain human remains, I’ll insert a cut. So you will not be surprised by human remains randomly in your timeline.

Now, here are some ethical things I need you guys to understand and adhere to:

- These people had names in life, and you do not get to give them new ones. Naming a skeleton is verbotten in archaeology circles, and often will extend to Bone Clones because they are casts of real bones. The correct terminology here is either “the/this individual” or “the remains”. If specificity is needed they’re either given an identification number or referred to by their demographic information. If you have the name of the individual bc there was a gravestone or records, then it’s ok to use it. Often we don’t though for privacy reasons.

- These were people. They had tastes, beliefs, people who loved them, etc. - all of which were different than mine or yours. Please keep that in mind when commenting.

- There is no ethical way for a lay person to obtain human remains, aside from direct donation by a relative or friend. No, I don’t care what they website says in their statement about ethical sourcing. They did NOT obtain the remains ethically. The people who sold the remains almost always do so under duress, usually economic. And if they weren’t given, they were stolen. There is No. Ethical. Way. To. Purchase. Human. Bone.

- Modern bone collections obtained by institutions for education usually are obtained ethically. Often via donation by a living donor before their death for the purpose of scientific education. In other instances they are obtained from legally-dug excavations, from donation by family members (IE, no money exchanged and consent given.), or with some other kind of permission. However, there are many existing bone collections that pre-date this practice and are NOT obtained ethically. In the US these are undergoing identification (we’ll get to this in another post) and repatriation, but this is just one of the many thorny issues that physical anthropologists and archaeologists have to be aware of.

- What other societies do with their human remains is going to seem strange and sometimes disgusting or objectionable to you. Not always, but definitely sometimes. This is their choice and in this house we respect the emic (within the social group) view on death rituals.

I think that’s everything…if I remember more I’ll sprinkle them in as I go along. Ethical violations are a Big Deal among archaeologists and other social scientists who handle human remains. It’s one of the few things we don’t joke about (because as we all know, archaeologists are forces of chaos.). The history of completely unethical treatment in the field makes us very sensitive to how human remains are handled and where they came from. Questions are 100% fine - you all are still learning and I’m not gonna get mad at you for not knowing yet. I’ll gently let you know if it’s inappropriate.

So here’s the stuff I’m planning on getting to:

Human vs. Animal

Sex identification.

Racial identification.

Age identification.

Teeth!

Damage to the skeleton (this might be two posts.).

Other random stuff that might come up while I’m doing the other things.

So….let’s begin….mwahahahahahahahaha. And for making it to the bottom of this post you get a bonus picture of me AND the dog:

His name is Gage, and my name is Kristina - you’re welcome to use it. I know probably “Kyidyl” isn’t easy to say in your heads. :) It’s pronounced kai-dul if you were every wondering tho. Now you can put a face to the internet voice. :)

#Bones#anthropology#archaeology#archeology#science#science posts#infodump#longpost#original content#queue#humans#human bone#human remains#bioarchaeology#my field

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reblogged from my main as part of my backlog of science posts. :)

Ok naughty children time to learn about NAGPRA. It’s not pretty and it’s not gonna have cool pics but it’s important. Since it’s kinda boring tho here’s a pic of my sister’s dog sleeping on my bed last night as payment:

That’s his “I’m lazy sleeping but would like belly rubs plz” pose. Note how much space his chonky self takes up on my twin bed, lol.

Anyway, so what is NAGPRA? The answer here is relevant to a lot of things that aren’t archaeology. NAGPRA stands for the North American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. It was signed into law in 1990 and it is the landmark piece of legislation in any field that includes native artifacts and remains in any way. That includes archaeologists, but also museums, construction, universities, etc. It’s an American piece of legislation, but it was the first of its kind and has spawned many other important laws in countries around the world concerning the handling of artefacts and remains. We are taught about it at all levels of our education, and it’s such and important piece of legislation that I even learned about it during my masters in the UK. I wasn’t even in the US and they were like “so, NAGPRA…”. But what does it do?

If human remains are found on a dig, all work must stop immediately. The cops are called, they bring in a bioarchaeologist or forensic anthropologist (usually a forensic) to determine if the remains are historical or not. If they are, then the state archaeologist is contacted. That person then contacts the leadership of the tribe who is responsible for the land that we’re on (it won’t necessarily be the tribe to whole the individual belonged bc, well, genocide.), and they determine what they would like done with the remains. Sometimes they don’t care and they allow you to dig them up. Sometimes they care very much and they take custody of the individual.). Again, a lot of this depends on context. At our site, if we find anyone they’re likely to be native but because of the civil war history also might not be. I am capable of determining which is which, so if we find human remains we’re lucky on that front. Native remains are pretty distinctive, as long as you have the skull or teeth. These laws don’t apply on private land, but most archaeologists will follow them anyway out of respect.

Requires that all new construction have an archaeologist on site to handle any artefacts or remains that are found during construction. This is why most archaeologists work in commercial archaeology. It’s also why what trump did down south with blasting things apart in his rush to build his stupid wall was 100% illegal.

Requires that all remains and artefacts currently in museums be returned to whence they came, if at all possible. This is the R in NAGPRA and is called repatriation. This is an incredibly slow, tedious process because of how poor the record keeping was when the stuff was collected and how many of the owners aren’t living anymore. Some stuff can’t be returned because of the decimation of the tribes that took place. This process started in 1990 and is still far from complete, but IS underway. Usually this won’t result in an empty museum. Often what happens instead is that the museum either creates replicas or the tribe loans the artefacts back to the museum. In both cases, new displays are created with the help of tribal leadership, so as you might imagine the quality of native information has skyrocketed since the introduction of NAGPRA. But I’ve noticed that a LOT of people on tumblr don’t know this is the case and they get real angry about native stuff in museums. I can’t speak for museums overseas tho bc NAGPRA doesn’t apply to them. The British Museum is notoriously bad about repatriation.

In the beginning, and sometimes even now, NAGPRA caused a lot of friction among scientists who didn’t think they should be beholden to natives when doing science. But for the most part we’ve worked it out, and the science has *vastly* improved due to actual communication between anthropologists of all kinds and natives. NAGPRA transformed all 4 fields of anthropology in a comparatively short period of time, and it very much has been for the better. It had a knock-on effect of making the whole discipline more respectful, more accepting, more open, and more meticulous in their work. It made it easier to add much-needed native voices to our work. Is it perfect? No. It’s not. There’s still a far amount of arguing (Kennewick man being a famous case.). There are still old archaeologists who didn’t come up under NAGPRA and don’t like it. There are construction companies that pretend they don’t find remains or artefacts because they don’t want to slow down their work so it all can be removed instead of destroyed. There are still anthropologists who are racist AF (tho far fewer than in other fields, IMO, because of the way we’re taught now.). But our work is ABSOLUTELY a million times better than it was and as the older pre-NAGPRA generation leaves the field, it’ll get even better. As repatriation work continues it’ll get better. So this is one of those cases where legislation was a good thing and subsequentially changed behaviors.

Anyway here’s another pic of the dog being spoiled and not wanting to get off my bed so I can sleep as a reward for getting this far, lol.

745 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another post reblogged from my main blog. A cool family story for your edification. :) I don’t have an update here but if I do, I’ll be sure to reblog and add more info.

Do you guys wanna hear a kind of interesting family story about Vinland/Vikings in the Americas? I don’t wanna flood you with archaeology content, lol.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyidyl Does Archaeology - Part 6

(yep, the rest of the parts of this are all under the KyidylCL tag, in case you happen across just this one.)

Rocks and…other stuff

Ok so here we are…we’ve arrived at my least favorite thing. Lithics. I’ll be honest with you guys, my disinterest in lithics means that I don’t have a lot to add here. But…I’ll do what I can.

So, first off, we’ve found *thousands* of lithics on this site. It is by far the most common thing we have. We’ve found broken tools, used up tools, intact points, fire cracked rock, like…the whole nine. One of the things you can learn from lithics is how far people were going to get their rock. For example, we have a lot of jasper in our lithics, so we know they were going up onto the nearby mountain because that’s where the nearest jasper deposits are. I *absolutely* am not the right person to go into a detailed account here, but I do know that they were going pretty far away to get their supplies - even over to the other side of the mountains. Or at least they were trading with people in closer proximity to those places.

I think what’s amazing to me is the degree to which they work quartz and quartzite. Here’s one of the points we found:

I’m pretty sure, if I’m remembering the things the Rock Guy told me correctly, that point is made of quartzite. Quartz and quartzite are very hard (7/7.5 on the Mohs scale aka the rock hardness scale.), so working them is difficult. I don’t know how to do it, but I know it must have taken either an impressive amount of brute force or an impressive amount of energy. Either way, it’s neat. Hell I found a piece of quartz the last time I was in the field (which I don’t have, or I’d show you.) that literally looked like it was cut like a gemstone. It’s more likely it came out of a geode but still, they did cool shit with quartz. Some of what we’ve found has been almost as clear as glass.

I’m aware that the style a point is made in (and everything that is, well, pointy…is a point. It includes spear tips, arrow heads, etc.) is indicative of the age of a site, but I don’t know enough here to go into it and we’ve already covered age in the pottery and digging post (it’s late woodland - early contact, c. 1300s - 1700s), so I’m just gonna show you some cool pictures.

First point that we found…

Same hole, another point. Probably both are arrowheads given the size. The one I’m holding up in the picture up there was probably a spear, not an arrowhead. Arrowheads are actually really small.

Here’s another weird rock:

It’s weird because that one in the upper right has that groove in it and is kinda squished. to me it looks like a tile, which would be really anachronistic to this particular site, and our Rock Guy assures me this is a natural thing, but these rocks have something on them I’ve been finding on a lot of the lithics: a red residue. You can see it pretty clearly on the top surface on the center rock, but it’s in the grooves on the right one too. These rocks didn’t come out of the pit with the red dirt, so it’s not like…red dirt from burning. To me it looks like ocre, but this is one of those areas where my knowledge base just comes up short and I need to wait for someone who knows more to look at them. But lets just say that I have this experience often where I’ll say something like “this looks like ocre” and people will be like “nooo, that doesn’t make sense” and then they’ll spend some time with the artefact and be like “hey look at this it looks like ocre” and I’m over here like….yes….I know….I told you that weeks ago…perhaps if I’d found a way to say it in a male voice we wouldn’t be having this conversation. x.x Aaaaannnnnyway.

Another kind of rock we have are fire-cracked rocks. Back in the day they used to heat rocks in the fire and then put them in pots to boil the water. They often reuse them, and after a few uses the constant “hot rock plunged into cold water” thing causes them to crack. It’s *extremely* common to find this all over the world. I saw it at the site I worked in England, too, when we were digging the Roman stuff. And it’s always kind of confused me because even though water boils basically instantly when you add the very hot rock, it would likely take longer for the rock to heat up than it would to just, y’know, boil the water, so why use the rocks? Then it occurred to me: because the rocks were just casually tossed into fires that weren’t being used for cooking. So you toss a few into the fire you’re using for warmth or for smoking or whatever in the morning and by the time dinner rolls around you just grab some rocks that’ve been in the fire all day and you toss them into a pot of water. Multitasking ftw! I would find some pics for you but I’m NGL guys, they just look like stones that’ve been cracked in half. People weren’t all that picky about the type or anything like that.

So yeah, that’s rocks, now who wants to see some weird shit? You, obviously, YOU want to see some weird shit.

Weird Shit

First up, because I STILL haven’t figured out why this is like this, we have this bone:

Ok honestly I’m only like 93% sure it’s a small piece of bone, but like…it’s definitely natural. It’s been burned for awhile but the weird part here is that IT’S GREEN. Now that’s not in and of itself weird - this is what happens to bone when there’s some metal nearby. It often leaves behind green staining on bones. But there was no metal in the ground here, and this thing was pretty deep. Below the civil war trench stuff. So I have no idea why it’s green like this.

This…thing. No idea what it is. Roughly a quarter inch long, metallic…looks like slag but, again, came out of a hole that was really too deep for us to be finding iron in (in this case, iron is a modern contaminant or something you’d only find in the top - IE, later - layers.). Meteorite, maybe? We’ve found some other weird stuff like this too but it was from much higher layers.

The back and front of a piece of bone that is too small for me to make a determination as to whether or not it’s human without like…a microscope. I don’t have one. I mean it probably *isn’t* human, but the color is right, soooo…IDK I just thought it was weird.

This is another small, weird, brown thing. BUT! it’s a different kind of small, weird brown thing than the other one. The other one passes the magnet test and fails to leave a streak when wet. This one fails the magnet test but left a brown streak on my skin when wet (no…I didn’t lick this one). So I’m pretty sure it’s a coprolite, but I’ve never handled them before so I’m not entirely certain. It looks like one to me, though (coprolite is very old poop. Poop is important bc it informs on diet and stuff. There have been literal fights and thefts in the archaeological community over coprolites.). This came out of one of the test pits and we haven’t dug over there yet so IDK.

This next bit is less weird and more cool.

This is a very small, very burned piece of bone but it’s cool for two reasons. One, see that long light-color diagonal mark in the lower right area of the top surface? That’s either a butchery mark or more tooth marks. I learn towards butchery becaaaaause….see how flat this is? That only happens when it’s been cut by people. Bones don’t break clean and flat like that, the crack or they splinter. When they crack they do it vertically because that is with the grain of the bone. This is horizontal, or across the grain. They have to be cut to look so flat. Here’s another example from the test pits:

See? Perfectly flat across the grain. This one has also been cut and burned. The white color of the two bones means they’ve been burned for a long time at a high temperature. All of the collagen - the soft stuff - gets burned off when you do it for long enough and at a high enough temperature and the minerals are left behind. Both of these images are macro images on bones that are smaller than an inch.

Ok, one more weird thing:

This is actually the back and front of a rock. It’s flat on both sides like pottery, but it tasted like a rock and it has no temper so…rock. But in that top image it has some kind of dark residue on it that almost looks like rust or paint, and the opposite side has small marks that look like cut marks or tool marks. I’m not sure what kind of rock it was, but it also had a dry, sandy texture to it. IDK it was just weird. The marks could just be damage over time to the rock (what we call taphonomic damage.), but the residue is pretty strange.

Anyway, that about wraps it up. I think that what I’m gonna do is start going through the uncleaned material I have downstairs (I got sidetracked by covid and the holidays. :P) and start posting what I found or anything out of the ordinary, if you guys want anyway. Thanks for sticking around through this long series of posts about the site I work at, and I hope you enjoyed it. As always, if you have any questions my askbox is open. :)

#science#archaeology#anthropology#history#native history#native#native american#the past#self reblog#queue#ArchaeologyCL#archaeology lab work

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyidyl Does Archaeology - Part 5

(as per usual, all these posts are collected under the KyidylCL tag)

Pottery and shErds

So, what are we talking about today? Well, I think the next thing is gonna be pottery. This is where we’re gonna talk about time, space, and dating a site. Because most people think that the only way to date an archaeological site is via C14. That’s not true, and actually we don’t always do it. C14 dating can have some problems, including that the wood used in the fire is likely older than the time in which it was cut down and burned. It also only goes back 50,000 years, so anything older than that won’t have any carbon isotopes (it’ll have all decayed), and we have to use other things that are more expensive. And c14 testing itself is expensive - we sent in 2 samples and it was around $500/sample so we spent about $1000 on testing. Instead, there are other ways to date a site and one of the most accurate is pottery.

See, like all other kinds of material culture (AKA, stuff people leave behind. Non-material culture is like…song and story and stuff like that.), pottery follows stylistic trends and trends in how it was made. And it does this both regionally and chronologically. Which is great, because if we find bits of one type of pottery we know is made in one place in a settlement in another place, then we know the two people traded with each other. But I have to explain something else so that determining a date from pottery makes sense.

Every area of the country has what’s called a “type site” for a given period of time. In undergrad I was lucky enough to actually get to work on the type site for the Safety Harbour period, which is Weedon Island….ironically enough there’s a Weedon Island period and Weedon Island isn’t the type site for that period so uuuhhh…yeah it’s weird lol. Anyway, a type site is a site that is considered stereotypical for a given time and place in history. Usually they’re large and well-preserved, and they’re often the first sites found in that time period/area (but not always, which is how the above weirdness happened.). And so what happens is we dig ‘em and analyze the finds and do testing on those finds. So now we know “hey, this kind of pottery comes from here and it is X years old”. Now you know when you find it in other places where and when it comes from. This is all a very generalized explanation, but I think any more is like extraneous detail you don’t need. Just know that things like type sites help us determine where and when stuff like pottery was made. Lots of literature usually exists for type sites, but I actually can’t remember the type site for this area for this time period.

We also use a term called “diagnostic”, which is used much as it is in medicine. If we find a certain thing that was only made during a specific time period or in a certain place, then it’s diagnostic. IE, a certain kind of pottery is diagnostic of the late, middle, or early Woodland. The pottery we have at our site is diagnostic of the late Woodland. Some of the lithics we thought might be a bit earlier, but honestly I think that was just misidentification by the site director bc we were in the field at the time. Lastly, identifying pottery has a few components. Color and decoration I think are easy to understand (they didn’t have glazes, but you can make different colored pottery by varying the composition of the clay and the temperature at which it is fired.). Paste and temper are the other two. IDK how modern pottery is made, but old ass pottery is made with paste - the main body of the clay, the matrix that contains the temper - and temper. Temper is stuff they’d crush up and mix in to help it not break during firing and heating during normal use. So we combine these factors to ID the pottery and thus the age of the site and trading habits of the people in question. One last thing you need to understand about pottery - ancient people used pottery the way that we use disposable things. They didn’t think it was like an important thing that had to keep safe. They’d use it until it broke and then toss it in the garbage pit and make a new one. So it’s really common and we find it all over the place, but TBH in the future pottery *won’t* be diagnostic anymore because our ceramics come in such a wide variety that we couldn’t possibly hope to narrow down time or place.

Alright, so who wants pictures? You, of course. Who *doesn’t* want pictures? Here’s some of the pottery we found:

This is the larger shard that I found in the features I’ve talked about in previous installments. You can see where I accidentally broke it. >.> Anyway it’s kind of unique bc of the light color outside and the black inside. It’s like…idk, 4 or so inches long.

This is a rim piece that I happened to find two matching sherds of. I always check the rim pieces because the patterns on them usually make them easier to fit together. Honestly I’ve got hundreds of pot sherds from this site and I don’t have the sanity to try and make pots from them.

This is the outside and inside respectively of the largest piece we have. TBH taking this thing out of its box and handling it makes me nervous because of how large it is - about the size of my hand, but I did include my earbuds for scale. The black is charring from both firing and subsequent use, and it came out of the pit feature I’ve been talking about. And do you wanna know the cool thing about the inner surface of pottery? Because they didn’t use glazes, the surface was porous and retains the unique chemical traces of what was made in them. However, the vast majority of the time those kinds of tests aren’t done because archaeology as a whole is extremely underfunded and trace chemical analysis of pot residue is an expensive test requiring expensive equipment and expensive scientists. Funnily enough I probably could do some of this testing bc I used to be premed and so I’ve taken a lot of chemistry and know how to read a mass spec thing, but I don’t have access to the chemicals or tools to do these kinds of tests. Plus, they’re often destructive…which….I mean…there’s so much pottery that it doesn’t really matter if one piece gets destroyed but like you do still have to be careful *which* piece you destroy.

Anyway, you also can see the striations on the outside piece, and that’s decoration on the pot. It probably also helped with gripping it. This is a piece of Shepardware, which is diagnostic of the late Woodland period in the Shenandoah valley. Here’s some more cool pottery:

This is a random assortment of the kind of stuff we regularly pull out of the ground when it comes to pottery. The most common kind we have is the orange on one side black on the other (3 upper rt pieces), whiteish (upper left 2), orange on both sides (lower left 3) and totally black (lower right 3). All of ‘em are some variety of shepard or pageware. You can see the texture on a lot of them, too. We have a good mix of textured and untextured, and that’s why the composition of the pottery is more diagnostic than the decoration. Frankly, people can and will put whatever design they think looks cool. But they made that particular design by wrapping twine around the end of a flat stick and pressing it into the surface of the wet clay. I also chose those two upper right pieces because they have really visible temper. Here’s a side shot of one of them:

You can see how big the bits are compared to my fingers (yeah, there’s dirt under my nails….I haven’t taken some tweezers to them yet after working on the car.). And…wait, I WAS going to try to describe this to you but then I was like “no, they deserve better” and I broke out my DSLR and my macro lens and took some pics. Here are some macros of the temper:

The white balance is a little off on the top one…the bottom one is more true to color (they aren’t the same piece of pottery, but they are a similar color). So you can see that it’s crushed up limestone. Pardon the depth of field on those…I had to open the aperture pretty wide to get one that wasn’t blurry bc I don’t exactly have bright lights in my room.

Anyway….so that’s the pottery we’ve gotten at the site and what we can learn from it. It’s going to take some time before we can start determining patterns and whatnot in regards to style, but we do have some evidence of trading here because some of the pottery we have is from the piedmont culture….

…wait, let me explain what that means. When archaeologists need to describe a group of people who existed in a given place in a given time based on similarities in material culture regardless of ethnic and social grouping we call it a culture. This is different than the standard meaning of the world culture, or even the way a cultural anthropologist would use the word. So when I say the piedmont culture, I mean people that lived in the general area of the Piedmont plateau during the late woodland. They were of varying tribes, languages, etc. And we do this to describe the extant boundaries of cultural influence of particular trends in physical objects and not the social groupings of the humans in question. So, for example, lots of people are familiar with the Clovis culture. When archaeologists use this term we mean “these are the boundaries of the places we are finding physical objects in the group we’ve named Clovis” not “everyone in this area was a Clovis person”. Like no, obviously, they weren’t. There were tons of social groups, tribes, etc. that were all distinct and different. It’s a way of mapping cultural influence via physical objects to see how far they spread and who was using them.

So, we have some piedmont stuff despite not being in the piedmont area, so we know that they were trading with those natives. If you’re interested in more detail here, this is the VDHR resource I use for IDing pottery. It looks like it came to visit you from the late 1990s, but the info is good and it’s easy to use.

Anyway, that’s it for tonight. Tomorrow is gonna be rocks and weird stuff, depending on how much I end up saying about rocks. Probably not much bc we know how I feel about rocks. ;)

#science#anthropology#archaeology#pottery#native pottery#native#native american#history#the past#archaeological dig#lab work#learning#queue#self reblog#culture#physical culture#material culture#ArchaeologyCL

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyidyl Does Archaeology - Part 4

(As before, if you’re only seeing this part 4, the rest of them have the tag KyidylCL)

THE ARTEFACTS

Ok, so I’ve talked about the site and what we’ve been digging in and such, but I’m gonna be honest with you guys: I like lab work exponentially more than field work. So I am the one who has been processing the vast majority of the finds and ergo have lots of stuff. That’s why I sometimes make jokes about the stuff in my basement - I’m storing the majority of it here in my basement. I’ve gotten the question before about ownership, so here is how that works. The dig is on private land so anything we get technically belongs to the owner of the land. Now, as far as I know, he has no interest in keeping any of it so it’ll likely end up in the hands of the arch society, who will basically just be custodians of it but not owners. It might end up in a museum, too. I don’t really know, but that determination won’t be made until we’re finished, and not by me.

So every site has its own sort of categories of stuff that you find depending on who lived there (although for ease, archaeologists often categorize this stuff based on location and time - more on that later.). For our site the majority of it falls into these categories: animal bone, shell, lithics, pottery, charcoal, modern contaminants, and artefacts. And, to lend a bit of clarity here…lithics are anything made of rock. So they include fire cracked rocks, flakes from stone tool making, material that was used in construction, material that was crushed to make temper for pottery paste (more on that later, too.), etc. If it came from a rock it’s a lithic.

And imma tell you a secret: I hate lithics. Everyone has their thing, their category of human refuse that they simply do not like. A prof of mine hated teeth and pottery. That’s just how it is, and mine is lithics. I think they’re boring, I can’t tell a flake from a blade, I don’t give a single fuck what material they are, I don’t care about the style or craftsmanship…I just don’t care. I call them all rocks, and I do it so much that everyone on the site has started accidentally calling them rocks, too, which amuses me. Rocks, to an archaeologist, means “stone that wasn’t altered or used by people”. They’re worthless. Not that I think lithics are worthless - far from it - I just really hate them and this site has so. goddamned. many. Lucky for me, we have a Rock Guy aka someone who really loves lithics and actually has gotten pretty good at flint knapping and just, y’know, is really into rocks.

And to clarify about artefacts. When you’re out in the field everything you find is either an artefact or a find. The collection of these things is called an assemblage. When you’re doing lab work and sorting through it all later on an artefact is, well…like a thing. I’m explaining this poorly….it’s a complete object with a specific function. So, a whole pot = artefact, broken pieces = sherds (not shards, sherds.). Complete arrowhead = artefact, flakes or a broken one = lithic. Artefacts also tend to be somewhat unique, or at least something you don’t have a lot of. They don’t always have to be complete, anything that is a specific object can go in here. Like, for example, this piece of pipe we found:

To recap, we’ve got pottery, charcoal, lithics, shell, bone (animal - we haven’t found human. But I’m just gonna say bone.), and artefacts. If you are sensitive to things like that, this is your warning that this post is going to have pictures of animal bone and you should scroll quickly.

Now, for reference, this is what it all looks like before I clean it and after it’s been dying out for a day or two (the ground has natural moisture, so I basically just open the bags and let them air out.):

And, yes….I am cleaning them off on an actual antique blotter with real silver edges that my mom gave me for this express purpose. A factoid I’m only sharing because it amuses me in that sort of “bet they never envisioned this use for this thing” sort of way. Normally, if I was in a real lab, you’d do this over a metal tray. When you’re working with an assemblage you never hold it over empty space, you always hold it over the bench and preferably over whatever your work surface is. That doesn’t mean I haven’t dropped my fair share of stuff anyway, but most of it just lands on the work surface and not the floor, which is why you hold it over a work surface. But anyway, as you can see, it just looks like a brown, dirty mess. I usually do a quick sort of the stuff I know for sure what it is and then I wash it with a soft toothbrush and some water. The rocks I just submerge and swoosh around because they’re rocks and I can’t really damage them and there’s SO FRIKKIN MANY that I refuse to clean them individually.

So now that you’ve gotten through that long-winded but necessary explanation of terms, where are we at? Since I’m a bioarchaeologist and I prefer things that were once alive to the general detritus of human society, we’re gonna start with the bone. Specifically, we’re gonna start with how I know those two pits from yesterday’s post are one pit. This is how:

This is a deer bone. Don’t ask me which one bc I’m really not good at ID’ing species and animal anatomy, but it’s a leg bone of some kind. See how it’s broken? One piece was found in one hole and the other piece was in the other. Clearly it’s the same animal, ergo the pits are related to each other. The vast majority of what came out of that particular feature was bone, with the rest being charcoal and the occasional pot sherd. This means it was probably used for cooking and not as a garbage pit. Also there was food in it, if you recall the cooking accident from yesterday. but sometimes y’know, stuff falls into the fire pit or it’s put in there as a way of disposing of it.

But wait, I have more cool animal bones!!

Ok, so there’s this one:

This bone has a special place in my heart. IDK what species it is (I *think* it’s a fragment of deer long bone.), but that’s not why it’s cool. This single bone is strong evidence for the presence of dogs. =D See that circular mark on the right? That is the impression of a canine tooth from a carnivore. Human teeth can’t make those marks in bones - our teeth aren’t strong enough to do significant damage to bone, and anyway we tend to crack bones open with rocks (a form of damage called percussion marks.) and not with our teeth. Those other longer scratch marks are also likely from chewing, not butchery, because they’re in the right places and they’re the right shape. Now we know this was a settlement, and this bone was found smack in the middle surrounded by human detritus and not on the fringes or outskirts. There were no domesticated felines in the Americas at the time BC this is from the lower pre-contact level, so what’s really the only carnivore that would be wandering around a human settlement? Dogs. I love this kinda stuff because it’s so easy see them chilling around the fire pit, talking and eating, teasing whomever it was that spilled dinner, and then tossing the bones to their dogs to gnaw on after dinner. It’s just such a people kind of thing, you know? All from one small, circular mark. I actually found more on later bones that came out of other places, so it’s pretty safe to say there were dogs living here with their people even though we have found neither people nor dogs.

So here’s another cool bone:

Again, no idea what species it is bc I’m not a zooarch (yes, there are archaeologists that specialize in animals and wooooo boy can they tell you a LOT about migration and eating habits of people.). It’s about the size of half my thumb, IE, not large. This one is cool, and it’s the only one I have like this, because of that notch you can see vertically in the image on the right hand side. I don’t know what it was for, but I DO know that it was an intentionally made modification to the bone. Those striations aren’t natural - natural bone is smooth or has a very specific texture and this isn’t that. It’s probably not damage done to the bone after it was deposited in the archaeological record. It has the same patina as the majority of the rest of the bone, which you can compare to the lighter area there on the right hand end of the bone. That lighter area does not have the patina of age that the rest of the bone does, and is the result of damage in a much more recent time - probably as we were taking it out of the ground. Small bones are fragile. So someone gouged this channel intentionally in this bone, either because they were going to use it as decoration or it served some purpose as a tool. I’m not really sure what though. Hell, they could have just been bored and fidgeting after eating. Either way, it’s a human modification to this bone that has nothing to do with cooking or consumption (damage from human consumption is cracks and breaks, not scrapes.). It could also be a butchery mark, although it’s a bit deep for that. Butchery marks are there from separation of meat from bone - they’re usually just shallow scrapes.

Ok, last cool bone I’m gonna show you. Well, bones, plural.

Ok so this is part of the same assemblage as the ones above, and if I remember correctly these were the ones that came out of that pit. You can see the same bone with the canine tooth mark there in the center. There’s also some interesting things like some pottery on the left and a couple teeth off to the right (one is a deer and I *think* that curved on is a squirrel.), but the really interesting thing is the series of 3 shiny bones that are in the center. There’s a lot of ways to cook meat, and they all do different things to bones. You will often find the dry, brown looking ones like you can see here in the non-shiny bones. That’s like…your basic “this bone had meat on it when it was cooked”. Then you’ll see ones that are black, and that’s “this bone probably didn’t have meat when it was cooked, or someone tossed it back in the fire when they were done”. Lastly, you’ll see white bone, and that’s a bone that has been burned at a high temperature for a long time. Usually it’s done on purpose (you can use burned, powdered bone to make stuff.).

But the shiny ones were in a soup. And the reason I know that is *because* they’re shiny. Bones, especially old ones, aren’t shiny. I mean…you can see that. You have to do stuff to ‘em. And bones are porous, but those weren’t. They felt like hard plastic. And they get that way by being boiled. The shiny patina is what we call pot polish - they were stirred in the soup while it was cooking and rubbed against the side of the pot and each other, and it gives them a smoother texture.

All of these collections of bones tell us what and how they ate things. I know from what I can ID here (which isn’t everything, trust me.) that they ate a lot of deer and wild turkey (we have an entire almost completely intact turkey long bone.). There is also, I believe, squirrel (I found a portion of a skull and jaw that I’m pretty sure belong to a squirrel), and an assortment of other small rodents and birds. Lots of birds. Bird bone is really distinctive, it’s light and the spongy bone has a distinct texture. A zooarchaeologist can look at bones like this and ID species and age, and from there tell you what time year something was probably killed. Societies that hunted a lot tended to do it seasonally so that they wouldn’t damage the populations. Plus especially with fish and stuff they have very specific growing cycles and short lifespans, so they can also tell you a lot about where the people were hunting and when. Like certain fish will only spawn in certain places, so it’s really informative. Zooarchs are so important and there just aren’t enough of them.

Anyway, there are other cool things in the bones but I’m trying to strike a balance here between too much and not enough and I really love bone so I’m going to stop here for today. Tomorrow is going to be other artefacts (yeah, sadly, even lithics, lol), and what they tell us about the site and the people who lived there.

As an aside: if anyone has any like just general “how do they know this?” sort of questions about history and archaeology those would be fun to answer. I love to tell people how we do things but I don’t just wanna infodump. I DO want to explain procedure in what I hope is a readable way because I think understanding how we make the sausage will help people have more trust in science. So if you have any questions, please, send asks. If I don’t know the answer I’ll research it or pass it on to someone who does.

#science#anthropology#archaeology#artefacts#queue#ArchaeologyCL#history#the past#native#native american#self reblog#education#bone#animal bone

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyidyl Does Archaeology - Part 3

(As before, parts 1 & 2 can be found via the KyidylCL tag.)

THE PITS

So, we’ve got the info about the site and we’ve got the prep work done, so what next? Digging! But archaeologists don’t just randomly dig, we dig in very precise ways. There’s, generally speaking, two ways to make a hole for an archaeologist (and this *doesn’t* apply to burials. Burials are done differently.): a pit and a trench. A pit is usually a specific size and meant to uncover a small area. A trench is a long area that takes a cross section of a specific area and is meant for exposing lots of area. When you’re doing a whole settlement often a trench is used because of the volume. We’re doing a mixture, and we started with two 5ftx5ft pits (~1.5 meters for the non-americans in the crowd. Good rule of thumb for ft –> meters is that 3ft = 1 yard = 1 meter, approximately. It’s not exact but if you’re trying to imagine how big something is, it’s a good way of thinking about it.).

Pit one only had 1 interesting thing and I don’t have any pictures of it really so I’m just gonna tell you about it real quick. In pit 1 we found a feature, which is a spot where the dirt is a different color in an unnatural shape because humans did something. This particular feature was a post hole from a palisade wall. That’s interesting for two reasons: 1, the natives didn’t build palisades until they came into conflict with the colonizers. It isn’t that they didn’t need defenses previous to that, it’s that the people they were defending against didn’t have horses or guns. Once the colonizers arrived, they started copying their method of defense. 2, palisade walls are made of large trees. To cut them down they were first burned in the place where the cut was made to make cutting them easier. And this means CHARCOAL.

Archaeologists love charcoal. We can date that shit really easily. And this particular charcoal was sent out for dating. Came back as 1700s, which makes sense for this area. It took the colonizers a bit longer to push up into the mountains, so the dates for contact and treaties and that kind of thing are later than official first contact in the 1400s. So that’s the latest date we have for the site.

Now, pit 2. Pit 2 was, and still is, the most interesting pit on the site so far (we’ve opened a number of others, but it’s…lots of plow scars and jumbled artefacts.). Archaeologists, as I’ve mentioned, dig this kind of stuff in layers. So for our site (and I know a few of you following me are also archs, so I need you to know this was the site director’s choice not mine. >.<), we have a sod layer, layer 2 - the plow layer, and layer 3 the layer below the plow layer. General rule of thumb, at least the way I was taught is that you do it in increments or when the dirt changes color, whichever comes first. So layer 2 for us is pretty thick. Here’s what the pit looked like at the end of day 1 after we’d gotten the sod off and started bringing it down evenly:

The bucket is covering the test pit that’s at the center of it. The string is the boundaries of the pit, but also we attach what’s called a datum to it. A datum is a known spot above sea level that you use to make measurements as to how deep something is. It’s basically a string with a line level and you stretch it out until the line level reads, well, level…and then you use a ruler from there down to whatever depth you’re measuring. So when we find like…arrowheads and points and stuff (and this pit had several) we record where they were by saying “_____ inches BD”, or “below datum”.

Anyway, you can see already where there are some rocks and differences in color of the dirt. It’s honestly not all that interesting but I figured you guys might like to see the progression. This is that same pit about 2-3 working days later, and this is where it started to get interesting:

Some of the difference in color there is because some soil is freshly exposed and some isn’t. The pit in the middle is the remains of the test pit. The lighter dirt at the bottom is sub-soil for this area, so it’s where the plow zone ends. The rocks may or may not have been added by people, so we record them just in case. How you deal with rocks depends entirely on where you are digging. In Florida, where I went to school, rocks are important because 99% of what they’ve got there is sand and shell. So if you find rocks they were probably put there by people. Here? Sometimes it’s just part of the ground and sometimes it’s people. It really depends on how far down you find them. This is about midway through the pit so it could go either way. So we do what’s called “pedestaling” where we dig around them and let them sit on a pedestal of dirt. You’ll see that in a lot of pics going forward. The reason that we’ve dug those upper corners differently is because we were starting to see soil color changes and we were investigating them separately. Good thing too, because they both turned out to be part of a large fire pit feature. Next slide!

So here you can see that the dirt in those two areas that we’ve dug is a distinctly different color - it’s reddish. Reddish dirt is a sign that the dirt has been heated, so we’re following the red dirt here. The digging changes from going in layers to following these features. And we’re really methodical about it so that we don’t remove too much or too little and lose the line of the feature. Here we were lucky, all the dirt inside those features was full of tiny specs of charcoal. And, in the upper left up there - which was my feature to dig - there were huge chunks of charcoal. Also a really nice piece of pottery. Well, I mean, comparatively. It’s still just a large sherd that I accidentally snapped in two while removing but like it counts. The square in the lower leftish is ust from like the foam I’d been sitting on. Getting into a pit - rather than digging it from the sides - is something you do NOT do without permission and a lot of care. Here, the ground is really solid so I wasn’t going to ruin anything by getting in there and the pit was getting too deep to effectively dig from the side, so I spent a lot of time in weird positions on the flat parts of this pit. So, anyway, here’s a close up of the feature so you can see what I mean about the charcoal:

Charcoal is very, very black so when you’re digging it stands out bc nothing else is that dark or that bright. Everything else is covered in dirt. But you can see it there in the top half - it’s those dark flecks and blobs. There was a ton of it, and when I say a ton, I mean we got I think almost 300g just that DAY. And y’all know how light charcoal is. This was the stuff we sent in for c14 testing along with the palisade charcoal and it came back, if I’m remembering right, mid-1300s. That’s a period called the late woodland. It matches up with the pottery and points we were finding, but I’ll get to that when I start in on the finds.

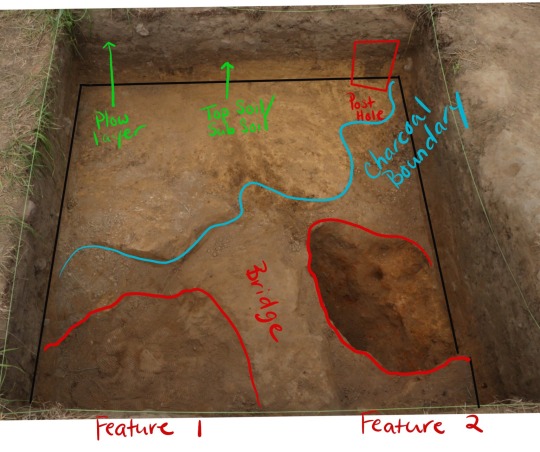

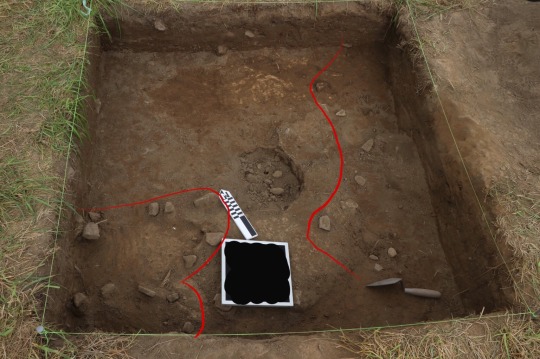

Now, I thought you might need some help with this next image so I brought it into procreate and drew on it. I know it looks like it came before the previous stage, but it didn’t. What happened is that we brought the whole pit down deeper to expose the edge of the large features. We also found a post hole in the process!

So I’ve marked the layers of dirt in the side wall for you so you can see what I mean when I’m talking about them. I’ve also marked out the bottom of the pit bc this angle made it a little hard to see. In the upper right you can clearly see the darker dirt of the post hole. A post hole is exactly what the name implies - someone dug a hole, stuck a post in it, and later the post was removed and filled with moar different dirt and now it’s a different color but in a distinctly unnatural shape. You can also see that we’ve long ago dug deeper than the test pit. The area I’ve marked “bridge” is an area of soil that didn’t have charcoal in it between the two pits that did. There was charcoal throughout that area - hence the blue boundary - but for the features themselves we were following the red dirt. And if that feature on the right looks deep to you it’s because it *is*. I dug it out and followed the charcoal and it went *under* the bridge.

Now you guys probably don’t realize this, but this is like…stupid deep to be finding this kind of stuff. We’re like 3ft below the surface here and still going down deeper. Around here the rate of topsoil accumulation is like…an inch every 600 years or so. The charcoal coming out of this pit is only 700 years old and it’s 3ft below the surface. So we’re likely looking at a hole that was dug by the natives for their own use. The thing that was confusing us was that we didn’t see the feature even start until we were almost at the bottom of the test pit so like…8 inches or so down. (about 16cm. 1inch is approx 2cm.) But then I was looking through some of my earlier images of the pit and I noticed this:

(north is the same direction in both pics)

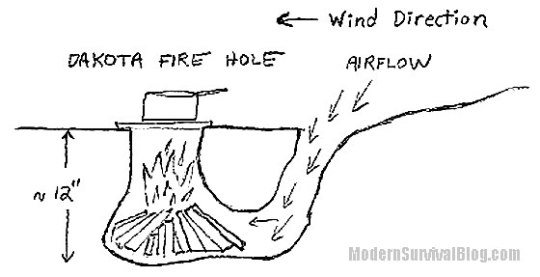

The rocks, the ones that could be either nature or people, approximately outlined the areas we’d found the fire pits. This is why you document shit. Even though this is still pretty deep to be finding this kind of thing, it at least makes more sense in the context of very disturbed site. So there might have been more evidence higher up, but it’s in the plow layer so we’ll never know. So what was the feature? Well, the two features were actually one feature (and you’ll have to wait till tomorrow’s post to find out how I know that.), and I think that might have been one of these:

(image credit)