Text

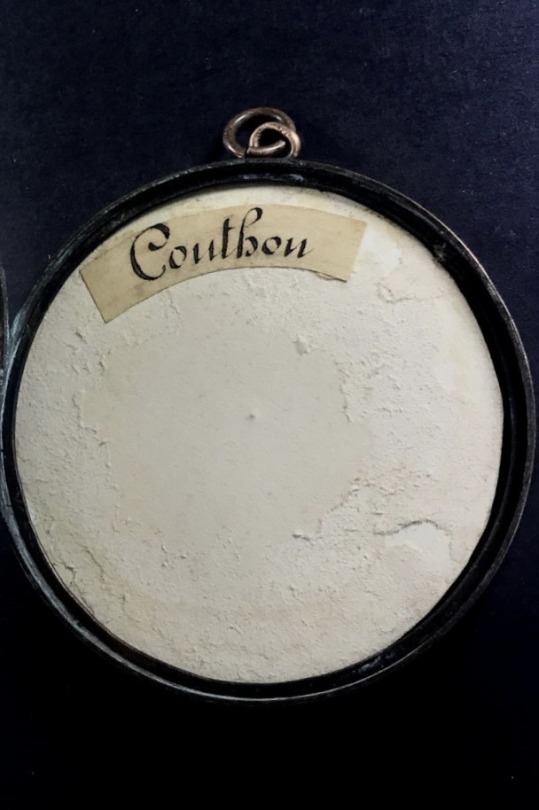

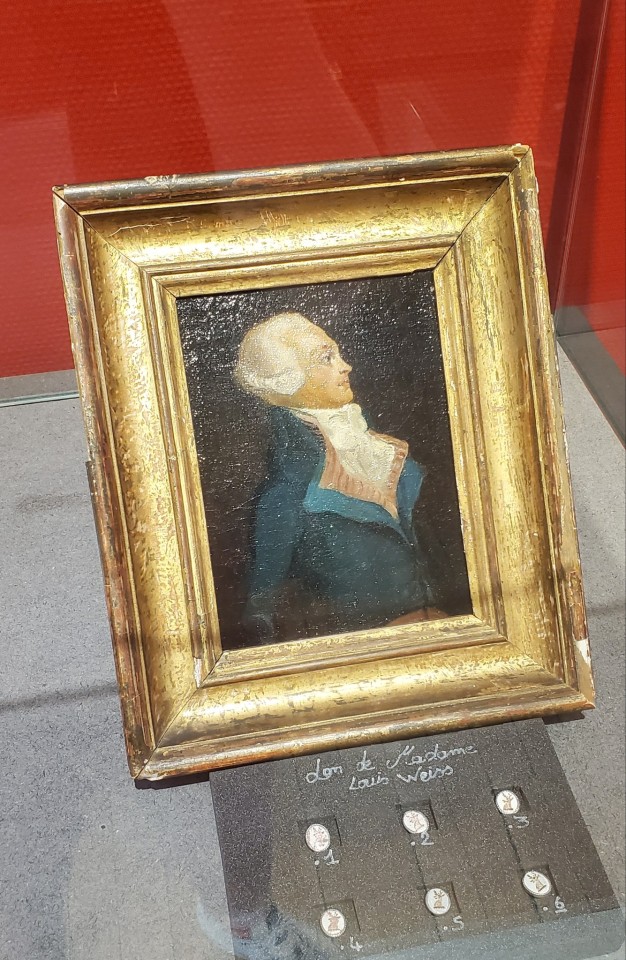

Miniature portrait of Georges Couthon by Jérome Langlois (1753-1804), 18th century (probably 1790)

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

When you get publicly slapped by 4 surrealist poets because you insulted a guy's historical crush

(translation and context under the cut)

Gallantly Defending Robespierre’s Honour

In the conservative daily paper, Le Gaulois, on March 3, 1923, the journalist and man of letters, Wieland Mayr, expressed his pleasure: there would not be, he wrote, a "vile apotheosis" for "that holy scoundrel" Robespierre. On the other hand, Mathiez had the Surrealists with him. Following the article in Le Gaulois, Robert Desnos (1), accompanied by Paul Éluard (2), Max Ernst (3), and André Breton (4), summoned Mayr in a café and publicly slapped him for insulting the memory of "the Incorruptible."

Why did Mayr get Slapped?

In short: studying history in the 1920s was a messy business, especially when it came to the French Revolution….

To explain why Mayr ended up getting slapped, please allow me to briefly dive into the French Revolution's historiography during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Keep in mind, that this is a grossly oversimplified version.

Before 1848, it was pretty standard for French republicans to proudly see themselves as inheritors of Robespierre’s legacy. (If you’ve ever wondered why in Les Misérables, Enjolras’ character is very much channeling Robespierre and Saint Just, here’s your answer!) However, things start to change with the Second Republic.

In 1847, Jules Michelet brought back the negative portrayal of Robespierre as a tyrannical "priest" and leader of a new cult. This narrative helped fuel an increasing dislike for Robespierre, with radicals like Auguste Blanqui arguing that the real revolutionaries were the atheistic Hébertists, not the Robespierrists.

Jump to the Third Republic, and the negative sentiment towards Robespierre was only getting stronger, driven by voices like Hippolyte Taine, who painted Robespierre as a mediocre figure, overwhelmed by his role. This trend was politically motivated, aiming to reshape the Revolution's legacy to align with the Third Republic's secular values. Obviously, Robespierre, the "fanatic pontiff" of the Supreme Being, didn’t quite fit this revised narrative and was made out to be the villain. Alphonse Aulard (a historian willing to stretch the truth to make his point) continued pushing Danton as the face of secular republicanism. Albert Mathiez, one of Aulard’s students, was not having any of it and strongly disagreed with his mentor’s approach.

The general disdain for Robespierre began to shift after World War I. One reason was that people could better appreciate the actions of the Revolutionary Government after experiencing the repression during the war themselves. Albert Mathiez and his colleagues were actively working to change Robespierre's tarnished image. With tensions high, it's no wonder Mayr ended up being publicly slapped by a bunch of poets who were defending the Incorruptible's honour!

Notes

Robert Desnos (1900-1945) was a French poet deeply associated with the Surrealist movement, known for his revolutionary contributions to both poetry and resistance during World War II.

Paul Éluard (1895-1952) was a French poet and one of the founding members of the Surrealist movement, celebrated for his lyrical and passionate writings on love and liberty.

Max Ernst (1891-1976) was a German painter, sculptor, graphic artist, and poet, a pioneering figure in the Dada and Surrealist movements known for his inventive use of collage and exploration of the unconscious.

André Breton (1896-1966) was a French writer, poet, and anti-fascist, best known as the principal founder and leading theorist of Surrealism, promoting the liberation of the human mind.

Source: Robespierre and the Social Republic by Albert Mathiez

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

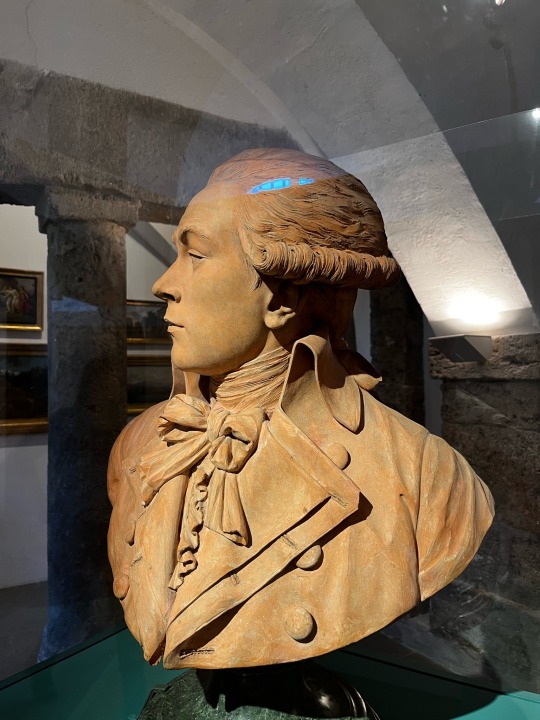

Terracotta bust of Maximilian Robespierre.

Terracotta bust of Augustin Robespierre.

Both busts are displayed next to each other at the French Revolution Museum in Vizille, France.

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

also not to be mean to olympe de gouges but the convention making divorce legal was more of a gain for women than putting rich women in power as she wanted

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robespierre on Property (24 April 1793)

First, I shall propose to you a few articles that are necessary to complete your theory on property; and do not let this word “property” alarm anyone. Mean spirits, you whose only measure of value is gold, I have no desire to touch your treasures, however impure may have been the source of them. You must know that the agrarian law, of which there has been so much talk, is only a bogey created by rogues to frighten fools. I can hardly believe that it took a revolution to teach the world that extreme disparities in wealth lie at the root of many ills and crimes, but we are not the less convinced that the realization of an equality of fortunes is a visionary’s dream. For myself, I think it to be less necessary to private happiness than to the public welfare. It is far more a question of lending dignity to poverty than of making war on wealth. Fabricius’ cottage has no need to envy the palace of Crassus. I would as gladly be one of the sons of Aristides, reared in the Prytaneum at the cost of the Republic, than to be the heir presumptive of Xerxes, born in the filth of courts and destined to occupy a throne draped in the degradation of the peoples and dazzling against the public misery.

Let us then in good faith pose the principles that govern the rights of property; it is all the more necessary to do so because there are none that human prejudice and vice have so consistently sought to shroud in mystery.

Ask that merchant in human flesh what property is. He will tell you, pointing to the long bier that he calls a ship and in which he has herded and shackled men who still appear to be alive: “Those are my property; I bought them at so much a head.” Question that nobleman, who has lands and ships or who thinks that the world has been turned upside down since he has had none, and he will give you a similar view of property.

Question the august members of the Capetian dynasty. They will tell you that the most sacred of all property rights is without doubt the hereditary right that they have enjoyed since ancient times to oppress, to degrade, and to attach to their person legally and royally the 25 million people who lived, at their good pleasure, on the territory of France.

But to none of these people has it ever occurred that property carries moral responsibilities. Why should our Declaration of Rights appear to contain the same error in its definition of liberty: “the most valued property of man, the most sacred of the rights that he holds from nature”? We have justly said that this right was limited by the rights of others. Why have we not applied the same principle to property, which is a social institution, as if the eternal laws of nature were less inviolable than the conventions evolved by man? You have drafted numerous articles in order to ensure the greatest freedom for the exercise of property, but you have not said a single word to define its nature and its legitimacy, so that your declaration appears to have been made not for ordinary men, but for capitalists, profiteers, speculators and tyrants. I propose to you to rectify these errors by solemnly recording the following truths:

1. Property is the right of each and every citizen to enjoy and to dispose of the portion of goods that is guaranteed to him by law.

2. The right of property is limited, as are all other rights, by the obligation to respect the property of others.

3. It may not be so exercised as to prejudice the security, or the liberty, or the existence, or the property of our fellow men.

4. All holdings in property and all commercial dealings which violate this principle are unlawful and immoral.

You also speak of taxes in such a way as to establish the irrefutable principle that they can only be the expression of the will of the people or of its representatives. But you omit an article that is indispensable to the general interest: you neglect to establish the principle of a progressive tax. Now, in matters of public finance, is there a principle more solidly grounded in the nature of things and in eternal justice than that which imposes on citizens the obligations to contribute progressively to state expenditure according to their incomes—that is, according to the material advantages that they draw from the social system?

I propose that you should record this principle in an article conceived as follows:

“Citizens whose incomes do not exceed what is required for their subsistence are exempted from contributing to state expenditure; all others must support it progressively according to their wealth.”

The Committee has also completely neglected to record the obligations of brotherhood that bind together the men of all nations, and their right to mutual assistance. It appears to have been unaware of the roots of the perpetual alliance that unite the peoples against tyranny. It would seem that your declaration has been drafted for a human herd planted in an isolated corner of the globe and not for the vast family of nations to which nature has given the earth for its use and habitation.

I propose that you fill this great gap by adding the following articles. They cannot fail to win the regard of all peoples, though they may, it is true, have the disadvantage of estranging you irrevocably from kings. I confess that this disadvantage does not frighten me, nor will it frighten all others who have no desire to be reconciled to them. Here are my four articles:

1. The men of all countries are brothers, and the different peoples must help one another according to their ability, as though they were citizens of a single state.

2. Whoever oppresses a single nation declares himself the enemy of all.

3. Whoever makes war on a people to arrest the progress of liberty and to destroy the rights of man must be prosecuted by all, not as ordinary enemies, but as rebels, brigands and assassins.

4. Kings, aristocrats and tyrants, whoever they be, are slaves in rebellion against the sovereign of the earth, which is the human race, and against the legislator of the universe, which is nature.

A Proposed Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen

The representatives of the French people, assembled in National Convention, recognizing that human laws which do not derive from the eternal laws of justice and of reason are only the outrages of ignorance or despotism against humanity; convinced that forgetfulness and contempt of the natural rights of man are the sole causes of the crimes and misfortunes of the world, have resolved to set forth in a solemn declaration these sacred and inalienable rights, in order that all citizens, being able constantly to compare the acts of the government with the aim of every social institution, may never allow themselves to be oppressed and degraded by tyranny, in order that the people always may have before their eyes the bases of their liberty and welfare; the magistrate, the rule of his duties; the legislator, the object of his mission.

Accordingly, the National Convention proclaims in the presence of the Universe, and before the eyes of the Immortal Legislator, the following declaration of the rights of man and citizen.

1. The aim of every political association is the maintenance of the natural and inalienable rights of man and the development of all their attributes.

2. The principal rights of man are those of providing for the preservation of his existence and his liberty.

3. These rights appertain equally to all men, whatever the difference in their physical and moral powers.

4. Equality of rights is established by nature; society, far from impairing it, guarantees it against the abuse of power which renders it illusory.

5. Liberty is the power which appertains to man to exercise all his faculties at will; it has justice for rule, the rights of others for limits, nature for principle, and the law for a safeguard.

6. The right to assemble peaceably, the right to manifest one’s opinions, either by means of the press or in any other manner, are such necessary consequences of the principle of the liberty of man that the necessity of enunciating them presumes either the presence or the recent memory of despotism.

7. The law may forbid only whatever is injurious to society; it may order only whatever is useful thereto.

8. Every law which violates the inalienable rights of man is essentially unjust and tyrannical; it is not a law at all.

9. Property is the right of each and every citizen to enjoy and to dispose of the portion of goods that is guaranteed to him by law.

10. The right of property is limited, as are all other rights, by the obligation to respect the rights of others.

11. It may not be so exercised as to prejudice the security, or the liberty, or the existence, or the property of our fellow men.

12. All holdings in property and all commercial dealings which violate this principle are unlawful and immoral.

13. Society is obliged to provide for the subsistence of all its members, either by procuring work for them or by assuring the means of existence to those who are unable to work.

14. The aid indispensable to whosoever lacks necessities is a debt of whosoever possesses a surplus; it appertains to the law to determine the manner in which such debt is to be discharged.

15. Citizens whose incomes do not exceed whatever is necessary for their subsistence are exempted from contributing to public expenditures; all others must support them progressively, according to the extent of their wealth.

16. Society must favor with all its power the progress of public reason and must place education within reach of all citizens.

17. The law is the free and solemn expression of the will of the people.

18. The people is the sovereign, the government is its work, the public functionaries are its clerks; the people may change its government and recall its representatives when it pleases.

19. No portion of the people may employ the power of the entire people; but the wish which it expresses must be respected as the wish of a portion of the people, which is to concur in forming the general will. Each and every section of the assembled sovereign must enjoy the right to express its will with entire liberty; it is essentially independent of all constituted authorities and master of regulating its police and its deliberations.

20. The law must be equal for all.

21. All citizens are admissible to all public offices, without any distinction other than that of virtues and talents, without any title other than the confidence of the people.

22. All citizens have an equal right to concur in the nomination of the representatives of the people and in the formation of the law.

23. In order that these rights may not be illusory, and equality chimerical, society must pay the public functionaries and must arrange that citizens who live by their labor may be present at the public assemblies to which the law summons them without compromising their existence or that of their family.

24. Every citizen must obey religiously the magistrates and agents o£ the government when they are the spokesmen or the executors of the law.

25. But every act against the liberty, the security, or the property of a man, performed by anyone whomsoever, even in the name of the law, except in the cases determined and the forms prescribed thereby, is arbitrary and null; every respect for the law forbids submission thereto; and if it is executed by violence, it is permissible to repel it by force.

26. The right to present petitions to the depositaries of public authority appertains to every individual. Those to whom they are addressed ought to legislate on the matters which are the object thereof; but they may never forbid, restrain, or condemn the exercise of said right.

27. Resistance to oppression is the consequence of the other rights of man and citizen.

28. There is oppression against the social body when a single one of its members is oppressed. There is oppression against each and every member of the social body when the social body is oppressed.

29. When the government violates the rights of the people, insurrection is the most sacred of rights and the most indispensable of duties for the people and for each and every portion thereof.

30. When the social guarantee is lacking to a citizen, he returns to the natural right of defending all his rights himself.

31. In either case, to make resistance to oppression subject to legal forms is the last refinement of tyranny. In every free state the law must, above all, defend public and individual liberty against the abuse of the authority of those who govern: every institution which does not assume that the people are good, and the magistrate corruptible, is vicious.

32. Public functions may not be considered as distinctions or rewards, but only as public duties.

33. Offenses of the mandataries of the people must be punished severely and promptly. No one has a right to claim himself more inviolable than other citizens. The people have a right to know what their mandataries are doing; these must render a faithful account of their activities and must submit to public judgment respectfully.

34. The men of all countries are brothers, and the different peoples must help one another, according to their power, as citizens of the same State.

35. Whoever oppresses a single nation declares himself the enemy of all.

36. Whoever make war on a people in order to check the progress of liberty and annihilate the rights of man must be prosecuted by all, not as ordinary enemies, but as rebels, brigands and assassins.

37. Kings, aristocrats, tyrants, whoever they be, are slaves rebelling against the sovereign of the earth, which is the human race, and against the legislator of the universe, which is nature.

Afficher davantage

139 notes

·

View notes

Link

Okay so I’m on mobile where links are gonna be difficult to provide so I’m just gonna have to barrel on ahead, but anyway:

Citoyen’s Guirault’s testimony before the Justice of the Peace about the circumstances of Marat’s marriage happen about a week after the Corday trial. In the Corday trial…

#free unions#marriage#simonne évrard#jean paul marat#maximilien robespierre#éléonore duplay#pierre louis prieur#prieur de la marne#rosalie baubrun

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

marat and simonne évrards relationship is so bizarre to me. me and my sugar daddy who is a woman 20 years younger than me. if we are married. we arent married because we are. no we arent <3

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

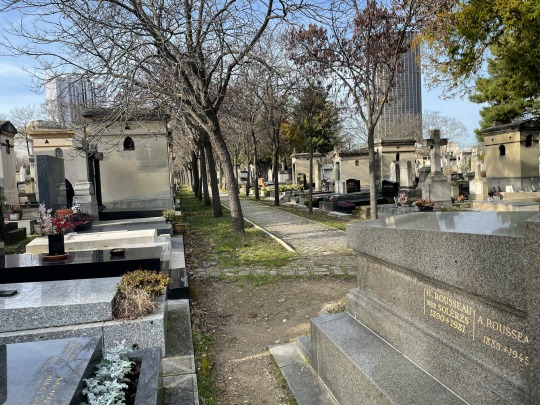

Where to find Goujon’s grave at Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris

I first visited Goujon’s grave in 2022 thanks to an internet page explaining how to get here; however this page now seems to have vanished so I thought I’d make my own guide for anyone interested.

Disclaimer: I am not sure Goujon is actually buried there since his name isn’t etched on the tombstone alongside other Goujon family members despite his portrait adorning it. Proper research should be done but I admit I don’t know where to start. Still, I recommend to visit as it is clearly meant as a place to honor and cherish his memory.

(directions after the cut)

1. From Metro Denfert-Rochereau, exit on Place Denfert-Rochereau and follow rue Froidevaux.

2. Get inside the cemetery on rue Émile Richard, Porte 5.

3. Go right on Avenue de l’Est. On the left you will see two narrow dirt paths between graves. Take the path by the Malestroit de Bruc family vault (picture below). It’s the shortcut I took but as shown on the map you should be able to find the grave just fine by following the main roads if you prefer.

4. Continue on the paved road (Avenue Raffet, picture below) after the dirt path. Keep straight at the crossing on the same road on to Division 4.

5. The Goujon Family grave is near the end of Avenue Raffet on the right side of the road:

(the last one is from my first visit in Summer 2022, the dappled sunlight falling on the grave was too nice to not post this picture again)

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

I understand the story of marat and his assassination event

But who is lepeletier?

Because I saw a drawing for him by louis David and I learned about his death which happen to be the same as Marat so yeah .. I wanna know about him.

According to the biography Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), its subject of study was born on 29 May 1760, in his family home on rue Culture-Sainte-Catherine, a building which today is the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris. His family belonged to the distinguished part of the robe nobility. At the death of his father in 1769, Lepeletier was both Count of Saint-Fargeau, Marquis of Montjeu, Baron of Peneuze, Grand Bailiff of Gien as well as the owner of 400,000 livres de rente. For five years he worked as avocat du roi at Châtelet, before becoming councilor in Parliament in 1783, general counsel in 1784 and finally taking over the prestigious position of président à mortier at the Parlement of Paris from his father in 1785. On May 16 1789, Lepeletier was elected to represent the nobility at the Estates General. On June 25 the same year he was one of the 47 nobles to join the newly declared National Assembly, two days before the king called on the rest of the first two estates to do so as well. A month later, during the night of August 4 1789, he was in the forefront of those who proposed the suppression of feudalism, even if, for his part, this meant losing 80 000 livres de rente. Four days later he wrote a letter to the priest of Saint-Fargeau, renouncing his rights to both mills, furnaces, dovecote, exclusive hunting and fishing, insence and holy water, butchery and haulage (the last four things the Assembly hadn’t ruled on yet). When the Assembly on June 19 1790 abolished titles, orders, and other privileges of the hereditary nobility, Lepeletier made the motion that all citizens could only bear their real family name — ”The tree of aristocracy still has a branch that you forgot to cut..., I want to talk about these usurper names, this right that the nobles have arrogated to themselves exclusively to call themselves by the name of the place where they were lords. I propose that every individual must bear his last name and consequently I sign my motion: Michel Lepeletier” — and the same year he also, in the name of the Criminal Jurisprudence Committee, presented a report on the supression of the penal code and argued for the abolition of the death penalty. After the closing of the National Assembly in 1791, Lepeletier settled in Auxerre to take on the functions of president of the directory of Yonne, a position to which he had been nominated the previous year. He did however soon thereafter return to Paris, as he, following the overthrow of the monarchy, was one of few former nobles elected to the National Convention, where he was also one of even fewer former nobles to sit together with the Mountain. In December 1792 he started working on a public education plan. On January 20 1793, he voted for death without a reprieve and against an appeal to the people during the trial of Louis XVI (Opinion de L.M. Lepeletier, sur le jugement de Louis XVI, ci-devant roi des François: imprimée par ordre de la Convention nationale). After the session was over, Lepeletier went over to Palais-Égalité (former Palais-Royal) where he dined everyday. The next day, his friend and fellow deputy Nicolas Maure could report the following to the Convention:

Citizens, it is with the deepest affection and resentment of my heart that I announce to you the assassination of a representative of the people, of my dear colleague and friend Lepelletier, deputy of Yonne; committed by an infamous royalist, yesterday, at five o'clock, at the restaurateur Fevrier, in the Jardin de l'Égalité. This good citizen was accustomed to dining there (and often, after our work, we enjoyed a gentle and friendly conversation there) by a very unfortunate fate, I did not find myself there; for perhaps I could have saved his life, or shared his fate. Barely had he started his dinner when six individuals, coming out of a neighboring room, presented themselves to him. One of them, said to be Pâris, a former bodyguard, said to the others: There's that rascal Lepeletier. He answered him, with his usual gentleness: I am Lepeletier, but I am not a rascal. Paris replied: Scoundrel, did you not vote for the death of the king? Lepelletier replied: That is true, because my confidence commanded me to do so.Instantly, the assassin pulled a saber, called a lighter, from under his coat and plunged it furiously into his left side, his lower abdomen; it created a wound four inches deep and four fingers wide. The assassin escaped with the help of his accomplices. Lepeletier still had the gentleness to forgive him, to pray that no further action would be taken; his strength allowed him to make his declaration to the public officer, and to sign it. He was placed in the hands of the surgeons who took him to his brother, at Place Vendôme. I went there immediately, led by my tender friendship, and my reverence for the virtues which he practiced without ostentation: I found him on his death bed, unconscious. When he showed me his wound, he uttered only these two words: I'm cold. He died this morning, at half past one, saying that he was happy to shed his blood for the homeland; that he hoped that the sacrifice of his life would consolidate Liberty; that he died satisfied with having fulfilled his oaths.

This was the first time a Convention deputy had gotten murdered, and it naturally caused strong reactions. Already the same session when Maure had announced Lepeletier’s death, the Convention ordered the following:

There are grounds for indictment against Pâris, former king's guard, accused of the assassination of the person of Michel Lepelletier, one of the representatives of the French people, committed yesterday.

[The Convention] instructs the Provisional Executive Council to prosecute and punish the culprit and his accomplices by the most prompt measures, and to without delay hand over to its committee of decrees the copies of the minutes from the justice of the peace and the other acts containing information relating to this attack.

The Decrees and Legislation Committees will present, in tomorrow's session, the drafting of the indictment.

An address will be written to the French people, which will be sent to the 84 departments and the armies, by extraordinary couriers, to inform them of the crime against the Nation which has just been committed against the person of Michel Lepelletier, of the measures that the National Convention has taken for the punishment for this attack, to invite the citizens to peace and tranquility, and the constituted authorities to the most exact surveillance.

The entire National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepelletier, assassinated for having voted for the death of the tyrant.

The honors of the French Pantheon are awarded to Michel Lepelletier, and his body will be placed there.

The president is responsible for writing, on behalf of the National Convention, to the department of Yonne, and to the family of Lepelletier.

The next day, January 22, further instructions were given regarding Lepeletier’s funeral:

On Thursday January 24, Year 2 of the Republic, at eight o'clock in the morning, will be celebrated, at the expense of the Nation, the funeral of Michel Lepeletier, deputy of the department of Yonne to the National Convention.

The National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepeletier in its entirety. The executive council, the administrative and judicial bodies will attend it as well.

The executive council and the department of Paris will consult with the Committee of Public Instruction regarding the details of the funeral ceremony.

The last words spoken by Michel Lepeletier will be engraved on his tomb, they are as follows: “I am happy to shed my blood for the homeland; I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality; and to make their enemies recognized.”

In number 27 (January 27 1793) of Gazette Nationale ou Le Moniteur Universel, the following long description was given over Lepeletier’s funeral, held three days earlier:

The funeral of Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau was celebrated on Thursday 24 with all the splendor that the severity of the weather and the season allowed, but with such a crowd that it could have been the most beautiful day of the year. At ten o'clock in the morning his deathbed was placed on the pedestal where the equestrian statue of Louis XVI previously stood, on Place Vendôme, today Place des Piques. One went up to the pedestal by two staircases, on the banisters of which were antique candelabras. The body was lying on the bed with the bloody sheets and the sword with which he had been struck. He was naked to the waist, and his large and deep wound could be seen exposed. These were the mournful and most endearing part of this great spectacle. All that was missing was the author of the crime, chained, and beginning his torture by witnessing the sight of the triumph of Saint-Fargeau.

As soon as the National Convention and all the bodies that were to form courage were assembled in the square, mournful music was played. It was, like almost all those which has embellished our revolutionary festivals, the composition of citizen Gossec. The Convention was ranged around the pedestal. The citizen in charge of the ceremonies presented the President of the Convention with a wreath of oak and flowers; then the president, preceded by the ushers of the Convention and the national music, went around the monument, and went up to the pedestal to place the civic crown on Lepeletier's head: during this time, a federate gave a speech; the president dismounted, the procession set out in the following order: A detachment of cavalry preceded by trumpets with fourdincs. Sappers. Cannoneers without cannons. Detachment of veiled drummers. Declaration of the rights of man carried by citizens. Volunteers of the six legions, and 24 flags. Drum detachment. A banner on which was written the decree of the Convention which ordered the transport of Lepeletier's body to the Pantheon. Students of the homeland. Police commissioners. The conciliation office. Justices of the peace. Section presidents and commissioners. The commercial court. The provisional criminal court. The department’s fix courts. The electorate. The provisional criminal court. The department's criminal courts fix. The municipality of Paris. The districts of Saint-Denis and the village of L’Égalité. The Department. Drum detachment. The seal of the 84, worn by Federates. The provisional executive council. National Convention Guard Detachment. The court of cassation. Figure of Liberty carried by citizens. The bloody clothes worn at the end of a national pike, deputies marching in two columns. In the middle of the deputies was a banner where Lepeletier's last words were written: "I am happy to shed my blood for my homeland, I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality, and to make their enemies known.”

The body carried by citizens, as it was exhibited on the Place des Piques. Around the body, gunners, sabers in hand, accompanied by an equal number of Veterans. Music from the National Guard, who performed funeral tunes during the march. Family of the dead. Group of mothers with children. Detachment of the Convention Guard. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Armed federations. Popular societies. Cavalry and trumpets with fourdines. On each side, citizens, armed with pikes, formed a barrier and supported the columns. These citizens held their pikes horizontally, at hip height, from hand to hand. The procession left in this order from the Place des Piques, and passed through the streets St-Honoré, du Roule, the Pont-Neuf, the streets Thionville (former Dauphine), Fossés Saint-Germain, Liberté (former Fossés M. le Prince), Place Saint-Michel and Rue d'Enfer, Saint-Thomas, Saint-Jacques and Place du Panthéon. It stopped front of the meeting room of the Friends of Liberty and Equality; opposite the Oratory, on the Pont-Neuf, opposite the Samaritaine; in front of the meeting room of the Friends of the Rights of Man; at the intersection of Rue de la Liberté; Place Saint-Michel and the Pantheon. Arriving at the Pantheon, the body was placed on the platform prepared for it. The National Convention lined up around it; the band, placed in the rostrum, performed a superb religious choir; Lepeletier's brother then gave a speech, in which he announced that his brother had left a work, almost completed, on national education, which will soon be made public; he ended with these words: I vote, like my brother, for the death of tyrants. The representatives of the people, brought closer to the body, promised each other union, and swore on the salvation of the homeland. A big chorus to Liberty ended the ceremony.

According to Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), civic festivals in honor of Lepeletier were celebrated in all sections of Paris, as well as the towns of Arras, Toulouse, Chaumont, Valenciennes, Dijon, Abbeville and Huningue. Lepeletier’s body did however only get to rest in the Panthéon for a little more than a year, as on February 15 1795, the Convention ordered it exhumed, at the same time as that of Marat. It was instead buried in the park surrounding Château de Ménilmontant, the properly of which the ancestor Lepeletier de Souzy had purchased in the 17th century and that still remained in the family.

One day after the funeral, January 25, Lepeletier’s only child, the ten and a half year old Susanne, who had already lost her mother ten years before the murder of her father, was brought before the Convention by her step-mother and two paternal uncles Amédée and Félix. It was Félix who had held a speech during the funeral and he would continue to work for his seven years older brother’s memory afterwards too, offering a bust of him to the Convention on February 21 1793, (on the proposal of David, it was placed next to the one of Brutus), reading his posthumous work on public education to the Jacobins on July 19 1793, and even writing a whole biography over his life in 1794 (Vie de Michel Lepeletier, représentant du peuple français, assassiné à Paris le 20 janvier 1793 : faite et présentée a la Société des Jacobins).

The president announces that the widow of Michel Lepelletier, his two brothers and his daughter, request to be admitted to the bar, to testify to the Convention their recognition of the honors that they have decreed in memory of their relative. It is decreed that they will be admitted immediately.

One of Michel Lepeletier’s brothers: Citizens, allow me to introduce my niece, the daughter of Michel Lepelletier; she comes to offer you and the French people her recognition of the eternity of glory to which you have dedicated her father... He takes the young citoyenne Lepelletier in his arms, and makes her look at the president of the Convention... My niece, this is now your father... Then, addressing the members of the Convention, and the citizens present at the session: People, here is your child... Lepelletier pronounces these last words in an altered voice: silence reigns throughout the room, with exception for a couple of sobs.

The President: Citizens, the martyr of Liberty has received the just tribute of tears owed to him by the National Convention, and the just honor that his cold skin has received invites us to imitate his example and to avenge his death. But the name of Lepelletier, immortal from now on, will be dear to the French Nation. The National Convention, which needs to be consoled, finds relief to its pain in expressing to his family the just regrets of its members and the recognition of the great Nation of which it is the organ. The Nation will undoubtedly ratify the adoption of Michel Lepelletier's daughter that is currently being carried out by the National Convention.

Barère: The emotion that the sight of Michel Lepeletier's only daughter has just communicated to your souls must not be infertile for the homeland. Susanne Lepelletier lost her father; she must find now find one in the French people. Its representatives must consecrate this moment of all-too-just felicity to a law that can bring happiness to several citizens and hope to several families. The errors of nature, the illusions of paternity, the stability of morals, have long demanded this beautiful institution of the Romans. What more touching time could present itself at the National Convention to pass into French legislation the principle of adoption, than that when the last crimes of expiring tyranny deprived the homeland of one of its ardent defenders and Susanne Lepelletier of a dear father! Let the National Convention therefore give today the first example of adoption by decreeing it for the only offspring of Lepelletier; let it instruct the Legislation Committee to immediately present the bill on this interesting subject. I ask that the homeland adopt through your organ Susanne Lepelletier, daughter of Michel Lepelletier, who died for his country; that it decrees that adoption will be part of French legislation, and instructs its Legislation Committee to immediately present the draft decree on adoption.

This proposal is unanimously approved.

Susanne being adopted by the state would however lead to a fierce debate when, in 1797, this ”daughter of the nation” wished to marry a foreigner. For this affair, see the article Adopted Daughter of the French People: Suzanne Lepeletier and Her Father, the National Assembly (1999)

Right after Barère’s intervention, David took to the rostrum:

David: Still filled with the pain that we felt, while attending the funeral procession with which we honored the inanimate remains of our colleagues, I ask that a marble monument be made, which transmits to posterity the figure of Lepelletier , as you clearly saw, when it was brought to the Pantheon. I ask that this work be put into competition.

Saint-André: I ask that this figure be placed on the pedestal which is in the middle of Place Vendôme... (A few murmurs arise)

Jullien: I ask that the Convention adopt in advance, in the name of the homeland, the children of the defenders of Liberty, who, for similar reasons, could be immolated in the vengeance of the royalists.

All these proposals are referred to the Legislation and Public Instruction Committees.

On Maure's proposal, the Assembly orders the printing of the speeches delivered yesterday at the Panthéon, by one of Michel Lepelletier's brothers, Barère and Vergniaux.

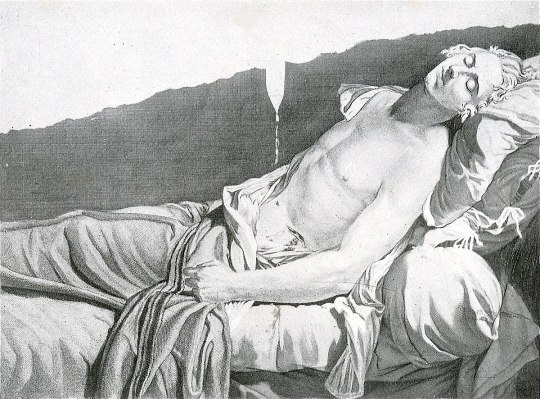

If it would appear David never got to make a marble monument of Lepeletier, on March 28 1793, he could nevertheless present the following painting of his to the Convention, which isn’t just a little similar to his La Mort de Marat.

(This image is an engraving of the actual painting, which has gone missing)

After Marat on July 13 1793 (on the very same day the plan for public education Lepeletier had been working on was read to the Convention by Robespierre) became the second assassinated Convention deputy, we find several engravings etc, depicting the two ”martyrs of liberty” side by side.

In the following months, even more people would be join the two, such as Joseph Chalier, a lyonnais politician executed on July 17 1794 and Joseph Bara, a fourteen year old republican drummer boy killed in the Vendée by the pro-Monarchist forces.

Lepeletier’s murderer, 27 year old Philippe Nicolas Marie de Pâris, a man who the minister of justice described as "former king's guard, height five pieds, five pouces, barbe bleue, and black hair; swarthy complexion, fine teeth, dressed in a gray cloak, green lapels and a round hat” on January 21, went into hiding right after his deed. In spite of his description being published in the papers and a considerable sum of money being promised to whoever caught him, Pâris managed to flee Paris and settled for a country house of an acquaintance near Bourget. He there ran into a cousin of one of the owners. When Pâris asked for food and a bed, he was refused and instead disappeared into the night again. In the evening of January 28 he arrived in Forges-les-Eaux and stopped at an inn, where he came under suspicion once he started cutting his bread with a dagger after which he locked himself into his room. The following morning he woke up with a start as five municipal gendarmes came bursting into his room and told him to come with them. Pâris responded that he would, but in the next second he had picked up his hidden pistol, placed it into his mouth, and pulled the trigger. Searching the dead body, the gendarmes found Pâris’ baptism record (dated November 12 1765) and dismissal from the king's guard (dated June 1 1792), on the latter of which had been written the following:

My certificate of honor. Do not trouble anyone. No one was my accomplice in the fortunate death of the scoundrel de Saint-Fargeau. Had I not run into him, I would have carried out a more beautiful action: I would have purged France of the patricide, regicide and parricide d’Orléans. The French are cowards to whom I say:

Peuple dont les forfaits jettent partout l'effroi, Avec calme et plaisir j'abandonne la vie.

Ce n'est que par la mort qu'on peut fuir l'infamie Qu'imprime sur nos fronts le sang de notre roi.

Signed by Paris the older, guard of the king, assassinated by the French.

Learning about what had happened, the Convention tasked Tallien and Legrand with going to Forges-les-Eaux and making sure the dead man really was Pânis. Having come to the conclusion that this was indeed the case, the deputies briefly discussed whether the body ought to be brought back to Paris, but it was decided it would be better if it was just buried "with ignominy.” It was therefore instead taken into the nearby forest in a wheelbarrow and thrown into a six feet deep hole.

Finally, here are some other revolutionaries simping for honoring Lepeletier’s memory just because I can:

…a tragic event took place the day before the execution [of the king]. Pelletier, one of the most patriotic deputies, and who had voted for death, was assassinated. A king's guard made a wound three fingers wide with a saber: he died this morning. You must judge the effect that such a crime has had on the friends of liberty. Pelletier had an income of six hundred thousand livres; he had been président à mortier in the Parliament of Paris; he was barely thirty years old; to many talents, he added the most estimable of virtues. He died happy, he took to his grave the idea, consoling for a patriot, that his death would serve the public good. Here then is one of these beings whom the infamous cabal who, in the Convention, wanted to save Louis and bring back slavery, designated to the departments as a Maratist, a factious, a disorganizer... But the reign of these political rascals is finished. You will see the measures that the Assembly took both to avenge the national majesty and to pay homage to a generous martyr of liberty.

Philippe Lebas in a letter to his father, January 21 1793

Ah! if it is true that man does not die entirely and that the noblest part of himself survives beyond the grave and is still interested in the things of life, come then, dear and sacred shadow, sometimes to hover above the Senate of the nation that you adorned with your virtues; come and contemplate your work, come and see your united brothers contributing to the happiness of the homeland, to the happiness of humanity.

Marat in number 105 (January 23 1793) of Journal de la République Française

O Lepeletier! Your death will serve the Republic: I envy your death. You ask for the honors of the Pantheon for him, but he has already collected the prize of martyrdom of Liberty. The way to honor his memory is to swear that we will not leave each other without having given a constitution to the Republic.

Danton at the Convention, January 21 1793

O Le Peletier, tu étais digne de mourir pour la patrie sous les coups de ses assassins ! Ombre chère et sacrée, reçois nos vœux et nos serments ! Généreux citoyen, incorruptible ami de la vérité, nous jurons par tes vertus, nous jurons par ton trépas funeste et glorieux de défendre contre toi la sainte cause dont tu fus l'apôtre; nous jurons une guerre éternelle au crime dont tu fus l'éternel ennemi, à la tyrannie et à la trahison, dont tu fut la victime. Nous envions ta mort et nous saurons imiter ta vie. Elles resteront à jamais gravées dans nos cœurs, ces dernières paroles où lu nous montrais ton âme tout entière; ”Que ma mort, disais tu, sera utile à la patrie, qu'elle serve à faire connaître les vrais et les faux amis de la liberté, et je meurs content.

Robespierre at the Jacobins, January 23

Wednesday 23 [sic] — We went to Madame Boyer’s to see the procession. I saw the poor Saint-Fargeau. We all burst into tears when the body passed by, we threw a wreath on it. After the ceremony, we returned to my house. Ricord and Forestier had arrived. I was unable to stop my tears for some time. F(réron), La P(oype), Po, R(obert) and others came to dinner. The dinner was quite fun and cheerful. Afterwards they went to the Jacobins, Maman and I stayed by the fire and, our imaginations struck by what we had seen, we talked about it for a while. She wanted to leave, I felt that I could not be alone and bear the horrible thoughts that were going to besiege me. I ran to D(anton’s). He was moved to see me still pale and defeated. We drank tea, I supped there.

Lucile Desmoulins in her diary, January 24 1793

…Pelletier's funeral took place this Thursday as I informed you in my last letter (this letter has gone missing). The procession was immense; it seemed that the population of Paris had doubled, to honor the memory of this virtuous citizen. The mourning of the soul was painted on all the faces: it was especially noticed that the people were extremely affected, which proves that they keenly felt the price of the friend they had lost. Arriving at the Pantheon, Lepelletier's body was placed on the platform prepared for it; his brother delivered a speech which was applauded with tears; Barère succeeded him. Then the members of the Convention, crowding around the body of their colleague, promised union among themselves, and took an oath to save the country. God grant that we have not sworn in vain, that we finally know the full extent of our duties, and that we only occupy ourselves with fulfilling them! In yesterday's session, Pelletier's daughter, aged eight [sic], was presented to the National Convention, which immediately adopted her as a child of the homeland.

Georges Couthon in a letter written January 26 1793

How could I be so base as to abandon myself to criminal connections, I who, in the world, have never had more than one close friend since the age of six? (he gestures towards David's painting). Here he is! Michel Lepeletier, oh you from whom I have never parted, you whose virtue was my model, you who like me was the target of parliamentary hatred, happy martyr! I envy your glory. I, like you, will rush for my country in the face of liberticidal daggers; but did I have to be assassinated by the dagger of a republican!

Hérault de Sechelles at the Convention, December 29 1793

For a collection of Lepeletier’s works, see Oeuvres de Michel Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau, député aux assemblées constituante et conventionnelle, assassiné le 20 janvier 1793, par Paris, garde du roi (1826)

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, in a recent post you mentioned that we have Philippe Le Bas' passport (or just its text?) Do you maybe have a source for the full text/do you know what it said? I'd love to read the rest of the description.

Yes! Paul Coutant, alias Stéfane-Pol, published two passports for Le Bas in his Autour de Robespierre : Le Conventionnel Le Bas, and I would be surprised if there aren’t other passports for him at the National Archives as well, as a representative on mission. NB: It seems I misremembered his height. Le Bas was only 5 pieds 5 pouces; in other words, around 176 cm.

The published ones read as follows:

ÉGALITÉ, LIBERTÉ.

Au nom de la Nation.

Département du Pas de Calais, district de Saint-Pol, municipalité de Saint-Pol. Laissez passer Philippe-François-Joseph Le Bas, homme de loi et député pour la Convention nationale, citoyen français, domicilié à la municipalité de Saint-Pol, district du même lieu, département du Pas-de-Calais, âgé de vingt-huit ans, taille de cinq pieds cinq pouces, cheveux et sourcils châtains, yeux gris-bleu, nez court un peu retroussé, bouche petite, menton rond, front large, visage ovale ; et prêtez-lui aide et assistance en cas de besoin.

Délivré à la maison commune le 15 septembre 1792, l’an IV de la Liberté.

&

La loi.

Laissez passer le sieur Philippe Le Bas, français domicilié en la ville de Saint-Pol, département du Pas-de-Calais, district de Saint-Pol, âgé de vingt-huit ans, taille de cinq pieds cinq pouces, cheveux et sourcils châtains, yeux gris, nez élargi, bouche moyenne, menton long, visage ovale, front haut ; et prêtez-lui aide et secours en cas de besoin.

Donné à Frévent, même département et district, sous notre signature et la sienne, le seize septembre mil sept cent quatre-vingt-douze, l’an quatre de la Liberté, le 1er de l’Égalité.

Which back in my LJ days, when I still did (admittedly rather mediocre) translations, I translated like this:

EQUALITY, LIBERTY.

In the name of the Nation.

“Department of Pas-de-Calais, district of Saint-Pol, municipality of Saint-Pol. Let pass Philippe-François-Joseph Le Bas, man of law and deputy for the National Convention, French citizen, domiciled in the municipality of Saint-Pol, district of the same place, department of Pas-de-Calais, aged twenty-eight years, height five feet five inches, chestnut-brown [châtain] hair and eyebrows, grey-blue eyes, short- and slightly snub-nosed, small mouth, round chin, large forehead, oval face; and lend him aid and assistance in case of need.

Delivered to the maison commune on 15 September 1792, Year IV of Liberty.

&

The law.

Let pass the sieur Philippe Le Bas, Frenchman domiciled in the city of Saint-Pol, department of Pas-de-Calais, district of Saint-Pol, aged twenty-eight years, height five feet five inches, chestnut-brown [châtain] hair and eyebrows, grey eyes, broad nose, medium-sized mouth, long chin, oval face, high forehead; and lend him aid and help in case of need.

Given in Frévent, same department and district, under our signature and his, the sixteenth September seventeen ninety-two, year four of Liberty, the 1st of Equality.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is Gabrielle's deathday. She died late at night on February 10, 1793. Very sad.

But a question I have had for a long time: Did she really die in childbirth?

The official document of her death states only that she died of illness. If it was death in childbirth, someone would write what happened to the child, but no one mentions it (at least I have never seen it). Her family (her brother Victor Charpentier wrote a letter about it to his fiancée Constance) does not mention why she died. And her son Antoine wrote a letter about his mother to the historian Michelet in later years, but even there the cause of death is not mentioned.

The source for this would be Lucile's diary, but considering the fact that it has long been misread in other places (the description of the August 10), I cannot be sure until we see the handwriting. (To be honest, it is hard for read.)

Many of the anecdotes about Danton's personal life and family (such as why he remarried Louise) are believed without being proved, so I don't think my question is bizarre...

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you tell me the story of the relationship between saint-just and desmoulins? . ..

Because I couldn't understand it properly so yeah ...

The first connection between Desmoulins and Saint-Just is from 2 January 1790, when the former publishes an annonce for the latter’s recently published Organt in number 6 of Révolutions de France et de Brabant:

Organt, poem in twenty verses, with this epigraph: Vous, jeune homme, au bon sens avez-vous dit adieu ? And this preface: J’ai vingt ans, j’ai mal fait, he pourrai faire mieux.

A few months later, we find the following letter from Saint-Just to Desmoulins. It is undated, but can be traced to May 1790. The letter makes Desmoulins, alongside Robespierre, who he wrote a letter to the following year, the only revolutionaries Saint-Just is confirmed to have contacted prior to heading to Paris in 1792. Unlike in the case of Robespierre however, the letter to Desmoulins implies a correspondence was actually picked up between the two:

Monsieur,

If you were not so busy I would tell you some more details about the Chauni assembly where one can find men of considerable calibre and quality. I was received in spite of my youth. Sieur Gelli, your compatriot from Vermandois had denounced me. He was thrown out bodily. We saw your compatriots, M. Saulce, M. Violette and others, by whom I was received with great courtesy. There is no point telling you (because you are not fond of foolish praise) that your region is proud of you. You will have known before I did that the department is fixed at Laon. Is that good or is that bad for one or other of the towns? It seems to me that it is no more than a point of honour between the two towns and points of honour are of little importance. I took the tribune; I worked with the intention of carrying the day on the question of the chief place but I did not follow on, I left, weighed down with compliments like a donkey burdened with relics, having, however, the assurance that at the next legislature I could be with you in the national assembly. You had promised to write to me, but I see clearly that you will not have the time. I am free as of now. Should I return to you or remain amongst the foolish aristocrats in this part of the world. At the time of my return from Chauni the peasants from my region came to look for me at Manicamp. The Comte de Lauraguais was greatly astonished by this rustic-patriotic ceremony. I led them all to his house for a visit. They said that he was out in the fields, however, like Tarquin, I had a rod with which I cut off the head of a nearby fern beneath the window of the castle and without a word we made a volte face. Farewell my dear Desmoulins. Write to me if you have need of me. Your latest issues are full of excellent things. Apollo and Minerva are still with you and are not displeased. If you have anything to say to your people in Guise I will be seeing them again in eight days’ time from Laon where I will be going on specific business.

Goodbye again: glory, peace and patriotic rage.

Saint-Just

I will read you this evening since I have only spoken to you of your recent issues by saying yes.

Different feelings can however be found a year later, in a letter Saint-Just adressed to Villain Daubigny on July 20 1791 (it is dated 1792 in Oeuvres complètes de Saint-Just, but Saint-Just’s biographer Bernard Vinot points out that this is most likely an error, since all the events it makes allusions to took place the previous year):

…Go and see Desmoulins, embrace him for me, and tell him that he will never see me again, that I esteem his patriotism, but that I despise him, because I have penetrated his soul, and because he fears that I will betray him. Tell him to not abandon the good cause, and recommend it to him, because he does not yet possess the audacity of magnanimous virtue.

What exactly had happened between the two for Saint-Just to write this about Desmoulins is unknown. The same can be said about the question regarding where and when the meeting between them he alludes to here played out, since neither of them are confirmed to have left their respective cities in 1791.

Yet another year later, in September 1792, both Saint-Just and Desmoulins were elected deputies for the National Convention, meaning the former came to settle in Paris on Rue de Gaillon 7, around 2,5 km from the latter’s home on Rue du Théâtre 1 (today Rue de l’Odeon 28). Aside from the fact both were fervent montagnards, I have not been able to find any connection between them until the second half of the following year, with the release of Desmoulins’ Lettre de Camille Desmoulins, député de Paris à la Convention, August général Dillon en prison aux Madelonettes. In it, Saint-Just, who had accused Dillon of having been asked to lead an uprising to put the dauphin on the throne and declare Marie-Antoinette regent on June 2 1793, got described the following way in a footnote:

After Legendre, the member of the Convention who has the highest opinion of himself is Saint-Just. One can see by his gait and bearing that he looks upon his own head as the corner-stone of the Revolution, for he carries it upon his shoulders with as much respect and as if it was the Sacred Host. But what makes his vanity killing is, that some years ago he published an epic poem in twenty-four cantos entitled Argant [sic]. Rivarol and Champcenetz, from whose microscope, used in the interests of the Almanach des grands hommes, not a single verse, not a single hemistich in France has ever escaped, have in vain gone searching for this; they who have hunted up even the least little scrap of literature have not seen Saint-Just’s epic poem in twenty-four cantos. After such a misadventure, how can he show himself?

According to some sources, the ”he carries his head like the Sacret Host” comment was a reply to something Saint-Just had himself said about Desmoulins. Marcellin Matton published in 1834 an anecdote (which it is presumed he obtained from Desmoulins’ mother- or sister-in-law) in which Guillaume Brune has a meeting with the Desmoulins couple at the time of the numbers of the Vieux Cordelier being released. The following conversation would then have played out:

”…You [Brune said] are also read by Barère who recognizes himself; by Saint-Just, who promised to make you carry your head like Saint Denis.”

”That’s true,” [Desmoulins] replied, ”I remember it: it was a very bad joke, and my answer was much better. Have you seen my letter to Dillon? In the approach and posture of Saint-Just, we see that he regards his head as the cornerstone of the republic, and that he carries it on his shoulders with respect like a holy sacrament. Was I wrong, and do you think that for such a good joke he would want to kill me? I only ask him for one favor, and that is to wait until he has given a valid response.”

In 1851, the historian Nicolas Villiaume similarly claimed to have had the same story told to him multiple times by Desmoulins’ mother-in-law. Interestingly though, the ”I will make him carry his head like Saint Denis” comment already appeared in works dated 1816 and 1825 (in both cases without any source cited). There, it is instead portrayed as a response to Desmoulins having written ”Saint-Just carries his head like the Sacred Host” and not as the cause of it. In light of this, I think the idea of Saint-Just having actually said it is something that must be taken with a huge grain of salt.

The things more reliable sources can tell us about Saint-Just’s attitude towards Desmoulins at the time are less overwhelming. He was away from Paris during much of the period where Desmoulins released and got in trouble for the Vieux Cordelier (from October 17 to December 4, December 10 to December 30, and finally January 22 to February 13), and when he was there during said period, I cannot find him recorded to have spoken about Desmoulins or the scandals his actions were causing a single time. Saint-Just also went unmentioned in all of the six numbers of the Vieux Cordelier that were released during the time they were both alive.

When the Committee of Public Safety decided to strike down Desmoulins and the other ”dantonists”, it was however Saint-Just who, like in the previous case with the hébertists, got tasked with writing a report against them. Here he obtained the help of Robespierre, who prepared around 65 notes for him to use as material against them. In said notes, Robespierre presented Desmoulins as less guilty than Danton and Fabre, having instead been more of their minion, a version of the story Saint-Just then stuck to when finishing his Rapport sur la conjuration ourdie pour obtenir un changement de dynastie; et contre Fabre d’Églantine, Danton, Philippeaux, Lacroix et Camille Desmoulins:

Bad citizen (speaking of Danton), you have conspired, you said, two days ago, bad things about Desmoulins, an instrument that you have lost, and you attributed to him shameful vices. […] For six months, a plan of palpitation and anxiety has been hatched within the government. Every day we were sent a report on Paris; we were flexibly insinuated, sometimes imprudent advice, sometimes misplaced fears; the tables were calculated on the feelings that it was important to arouse in us, so that the government would move in the direction that suited criminal plots; Danton was praised there, Hébert and Camille Desmoulins were accredited, and all their projects were assumed to be sanctioned by public opinion, to discourage us. […] What shall I say of those who claimed to be exclusively the old Cordeliers? They were precisely Danton, Fabre, Camille Desmoulins, and the ministry, author of the reports on Paris, where Danton, Fabre, Camille and Philippeanx are praised, where everything is directed in their direction and in the direction of Hébert. Danton had directed the last writings of Desmoulins and Philippeaux. […] Camille Desmoulins, who was initially duped and ended up being an accomplice, was, like Philippeaux, an instrument of Fabre and Danton. It was said, as proof of Fabre's good nature, that when he was at Desmoulins' house at the time when he read to someone a writing in which he requested a committee of clemency for the aristocracy and called the Convention the court of Tiberius, Fabre started to cry. The crocodile cries too. As Camille Desmoulins lacked character, his pride was used. As a rhetorician, he attacked the revolutionary government in all its forms; he spoke brazenly in favor of the enemies of the Revolution, proposed a committee of clemency for them; showed himself to be very inclement towards the popular party; attacked, like Hébert and Vincent, the representatives of the people in the armies; like Hébert, Vincent and Buzot, he himself treated them as proconsuls. He had been the defender of the infamous Dillon, with the same audacity that Dillon himself showed, when at Maubeuge he ordered his army to march on Paris, and take an oath of loyalty to the king. He fought the law against the English; he received thanks in England, in the newspapers of that time. Have you noticed that all those who were praised in England have betrayed their fatherland here?

According to an anecdote published in the pamphlet À Maximilien Robespierre aux enfers (1794), released shortly after thermidor by Taschereau de Fargues and Paul-Auguste-Jacques, Saint-Just and Robespierre had wanted to denounce Desmoulins and the other dantonists before arresting them, but been downvoted by their colleagues:

Why should I not say that [the dantonist purge] was a meditated assassination, prepared for a long time, when two days after this session where the crime was taking place, the representative Vadier told me that Saint-Just, through his stubbornness, had almost caused the downfall of the members of the two committees, because he had wanted that the accused to be present when he read the report at the National Convention; and such was his obstinacy that, seeing our formal opposition, he threw his hat into the fire in rage, and left us there. Robespierre was also of this opinion; he believed that by having these deputies arrested beforehand, this approach would sooner or later be reprehensible; but, as fear was an irresistible argument with him, I used this weapon to fight him: You can take the chance of being guillotined, if that is what you want; For my part, I want to avoid this danger by having them arrested immediately, because we must not have any illusions about the course we must take; everything is reduced to these bits: If we do not have them guillotined, we will be that ourselves.

Regardless of whether this be true or not, on March 30, Saint-Just was one of eighteen men to sign the by Amar drafted arrest warrant for Danton, Delacroix, Philippeaux and Desmoulins, who were all arrested in the night. The next day at the Convention, Robespierre shut down Legendre when he suggested the accused be allowed to come and defend themselves before the Convention, after which Saint-Just entered the hall, mounted the rostrum and read out the act of accusation the two of them had worked out.

Receiving a copy of Saint-Just’s report in his cell at the Luxembourg prison, Desmoulins got around to preparing a defence. In it, he held the author of the report to have held personal reasons for wanting him dead. He also referred to him as ”Monsieur le Chevalier de Saint-Just,” a nicknamed previously used by the girondin Salle:

If I had gotten the chance to print in turn, if one hadn’t put me in isolation, if one had lifted the seals and if I had the paper neccesary to establish my defense, if one gave me only two days to make a number seven, imagine how I would confront M. the chevalier Saint-Just! Imagiene how I would convince him of the most atrocious slander ! But Saint-Just writes leisurely in his bath, in his bathtub, he plots my murder during fifteen days, while I have no place to put my writing desk and only a few hours to defend my life. What is this if not the the duel of the Emperor Commodus, who, armed with an excellent blade, forced his enemy to fight with a simple foil garnished with cork? […] I arrive at the part of the report which concerns me. In living memory, there is no example of such atrocious slander as this piece. And yet there is not a single person in the Convention that doesn’t know that Monsieur the former chevalier Saint-Just holds for me an implacable hatred for a slight joke that I allowed myself five months ago in one of my numbers. Bourdaloue said: Molière puts me in his comedy, I will put him in my sermon. I put Saint-Just in a giggly number, and he puts me in a guillotine report where there isn’t a single true word in my regard. When Saint-Just accuses me of being an accomplice of Orléans and Dumouriez, he shows well that he is a patriot of yesterday. Who denounced Dumouriez first of all, and before Marat and more vigorously than anyone else? Certainly one cannot deny that it was me? My Tribune des Patriotes exists, let Saint-Just read the portrait I there painted of Dumouriez six months before his treason in Belgium, he will see that I have never since added anything to this portrait. And Orléans who he makes me the accomplice of, who doesn’t know that I was the first to denounce him? That the only writings on this faction that the Jacobins have printed and distributed were written by me? Does Saint-Just no longer remember my Histoire des Brissotins? […] There are witnesses to the fact that the great republican Saint-Just, at the beginning of the Convention, said: Oh! They want a republic, she shall cost them dearly! There are witnesses to the fact the ambitious Saint-Just said: I know where I go.

In an unfinished and unsent letter written to Robespierre around the same time, Lucile Desmoulins too held Saint-Just as the main culprit behind her husband’s fate, arguing that he had misled their friend:

…As far from the insensibility of your Saint-Just as from his base jealousies, [Camille] recoiled in front if the idea of accusing a college comrade, a companion in arms. […] Robespierre, can you really complete the fatal projects which the vile souls that surround you no doubt have inspired you to? […] Had I been Saint-Just’s wife I would tell him this: the sake of Camille is yours, it’s the sake of all the friends of Robespierre!

A rumor claiming that Lucile had been sent money from the imprisoned Arthur Dillon conveniently arrived around the same time the trial against the indulgents started getting off the rails. In the afternoon of April 4, after the proceedings had been closed for the day, Saint-Just again mounted the rostrum at the Convention and revealed the discovery of this new conspiracy:

The public prosecutor of the revolutionary tribunal reported that the revolt of the guilty had caused the court proceedings to be suspended until the Convention had taken measures. You have escaped the greatest danger that ever threatened freedom: now all the accomplices are discovered, and the revolt of the criminals at the foot of justice itself. Intimidated by the law, the secret of their conscience; their despair, their fury, everything announces that the good nature they presented was the most hypocritical trap that had been set for the revolution. What innocent person has ever rebelled before the law? There is no need for any other proof of their attacks than their audacity. What! those whom we accused of having been the accomplices of Dumouriez and Orléans, those who only made a revolution in favor of a new dynasty, those who conspired for the misfortune and slavery of the people are at the height of their infamy! If there are men here who are truly friends of liberty, if the energy that suits those who have undertaken to liberate their country is in their hearts, you will see that there are no longer any conspirators on the front line, who, counting on the aristocracy with whom they have marched for several years, call upon the people the vengeance of the crime. No, liberty shall not recoil in front of her enemies; their coalition has been revealed. Dillon, who ordered his army to march upon Paris, has declared that the wife of Desmoulins had received money in order to promote a movement to assassinate the patriots and the Revolutionary Tribunal. We thank you for placing us in the position of honor; like you, we will cover the fatherland with our bodies. Dying is nothing, provided that the revolution triumphs; here is the day of glory; this is the day when the Roman senate fought against Catiline; This is the day to consolidate public liberty forever. Your committees respond to you with heroic surveillance. Who can refuse you his veneration in this terrible moment when you fight for the last time against the faction which was lenient towards your enemies, and which today finds fury to fight liberty?

After having heard Saint-Just’s report, the Convention used this new discovery to order ”that the Revolutionary Tribunal shall proceed with the instruction relating to the conspiracy of Lacroix, Danton, Chabot and others. The President shall make use of every means which the law permits to cause his authority and that of the Revolutionary Tribunal to be respected, and to repress every attempt on the part of the accused to trouble public tranquillity and to hinder the course of justice. It is decreed that all persons accused of conspiracy who shall resist or insult the national justice shall be outlawed and receive judgment on the spot.” This order became essential for getting the dantonists condemned to death the following day.

Saint-Just had however nothing to do with the actual arrest warrant for Lucile, signed the same day by Robespierre, Billaud-Varennes, C-A Prieur, Carnot, Couthon, Barère, Du Barran and Voulland, which would lead to her ending up on the scaffold as well nine days later.

I’m currently blanking when it comes to contemporaries who had anything to say regarding the relationship between Saint-Just and Desmoulins.

79 notes

·

View notes

Note

May I ask the Frev-related places in Paris you've visited/plan to visit? Such as the CSP table, where is that?

CSP table is at National Archives. I asked @robespapier for the exact description of the location: National Archives at the Hôtel de Soubise, 60 Rue des Francs Bourgeois.

From frev related things, I visited:

- Carnavalet

- CSP table at National Archives

- Pantheon

- Le Procope (also Danton's statue nearby)

- Père Lachaise (frev people graves)

- Palais-Royal

- Tuileries Garden

- Place de la Concorde (it was closed for construction so just from accross the street, from Tuileries)

- Duplay house at rue Saint-Honoré (well, just outside, the sign with Robespierre's name next to the ugly fancy shoes shop)

- SJ's building at rue de Caumartin

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why would SJ not be, 'we have food at home?'

Because the dude was known to like restaurants. He was singled out, early in the days of the National Convention, as someone who frequents expensive (?) restaurants.

This slander hurt him so much that he a) talked about it/defended himself at the Convention (at a time he barely spoke; it was like his 3rd time at the rostrum) and b) he stopped going to restaurants... but continued to complain about it.

Reportedly, he did not own any cuttlery at home (except like one fork and one knife) and would eat in his office. Thermidorians later claimed that he dined every night in expensive restaurants with his mistress, which, yeah, Thermidorian slander probably, but plays directly into those rumours.

The only issue with the McDonald's meme is that it's not fancy food, but I still stand by my original judgment that SJ would not be "we have food at home!" at all.

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here are a few more photos from @burritofriedrich ‘s and my visit to Saint-Just’s house in Blérancourt!

There are five ground floor rooms that make up the museum, with reproductions of many portraits, documents and other objects. The first room is now a library and playroom for the local school:

The reproductions include a letter to Desmoulins, his baptismal record, and his sketch of the head of Antinous

@robespapier

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

This morning I went to the Beaux Arts of Arras (they're supposed to have Charlotte Robespierre's portrait, but it wasn't on display and the museum employees were unhelpful and couldn't even confirm to me they had it in storage) but I saw a tiny portrait of her elder brother and his (alleged) gilet de chasse (hunting waistcoat?) deer buttons. Then a few hours later I was back in Paris and at the Carnavalet, which has buttons from the same waistcoat!!

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

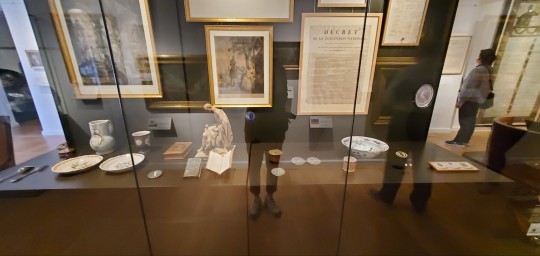

Robespierre's briefcase isn't on display anymore at the Carnavalet museum, and I'll try asking them about it, but my best guess is they are rotating stuff and also protecting the most fragile ones from too much exposure to light (a tapestry was removed too).

The showcase now:

And pics from November 2022 showing the tapestry and briefcase:

So I tried spotting the new things they might have pull out of storage, and I think this cool watch in the shape of a Phrygian cap wasn't on display before:

59 notes

·

View notes