Text

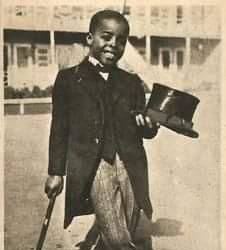

Ernest Fredric “Ernie” Morrison was the first Black child movie star. Morrison, who performed under the stage name Sunshine Sammy, was most famous as one of the Dead End Kids/East Side Kids.

As the oldest Our Gang cast-member Morrison earned $10,000 a year, making him the highest-paid Black actor in Hollywood. He made 28 episodes from 1922 to 1928 before he ditched Hollywood for New York’s vaudeville stages. He was featured on the same bills with such up-and-coming acts as Abbott and Costello and Jack Benny. After a few years, he returned and acted in the Dead End Kids movies. From the beginning, Morrison tapped into his experiences growing up on the East Side of New York City to shape the character of “Scruno.” He spent three years with the gang before leaving to work with the Step Brothers act, a prominent Black stage and film dance act.

Morrison was born on December 20, 1912 in New Orleans, Louisiana. He was the oldest child and only son born to Joseph Ernest Morrison, a grocer and later actor, and his wife, Louise Lewis. Ernie was later joined by three younger sisters, Florence, Vera, and Dorothy.

He made his film debut in the 1916’s The Soul of a Child at the age of 3. The story goes that his father worked for a wealthy Los Angeles family that had connections in the film industry. One day the producer friend asked Joseph Morrison if he could bring his son by the studio. Apparently the original child actor hired would not stop crying and they had pretty much given up trying to console him. Joseph brought young Morrison and the producer and director were impressed at how well behaved he was. It was this positive disposition that garnered his nickname, “Sunshine.” His father would later add “Sammy” to the moniker.

From 1917 to 1922, Morrison’s career was mainly in shorts that paired him with another popular child star of the silent era, Baby Marie Osborne. He also appeared in Harold Lloyd shorts and later with another comedian of the day, Snub Pollard and a now forgotten comedic leading lady of the day, Marie Mosquini. A feature was created for him, called The Sunshine Sammy Series, but only one segment was produced. Some critics believed, however, that the Sunshine Sammy episode provided comedy producer Hal Roach with the idea for the Our Gang film shorts, later shown on television and known by several other names, including the Little Rascals.

As the oldest Our Gang cast-member Morrison earned $10,000 a year, making him the highest paid Black actor in Hollywood. He made 28 episodes from 1922 to 1928 before he ditched Hollywood for New York’s vaudeville stages. He was featured on the same bills with such up-and-coming acts as Abbott and Costello and Jack Benny. After a few years, he returned and acted in the Dead End Kids movies. From the beginning, Morrison tapped into his experiences growing up on the East Side of New York City to shape the character of “Scruno.” He spent three years with the gang before leaving to work with the Step Brothers act, a prominent Black stage and film dance act.

Morrison was drafted into the army during World War II, where he appeared as a singer-dancer-comedian for troops stationed in the South Pacific. For several years after being discharged from the war, Morrison turned down a series of offers to return to show business, saying that he had fond memories of the movies but no desire to be part of them again. He left show business entirely, and took a job in an aircraft assembly plant and spent the next 30 years in the aircraft industry, apparently doing very well financially.

After his retirement, Morrison was rediscovered by film buffs who had learned of him after the revival of the Little Rascals in the 1970s. He made guest appearances in several television situation comedies, including Good Times and The Jeffersons.

Morrison died of cancer in Lynwood on July 24, 1989. He is interred at Inglewood Park Cemetery in Inglewood California.

Morrison, who appeared in 145 motion pictures, was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame in 1987.

#Ernest Fredric Morrison#Ernie#first black#child#movie star#black history#african american history#read about him#knowledge is power

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edwina Justus became the first black female engineer on Union Pacific in 1976. Justus spent 22 years transporting materials to Colorado and Wyoming. In 2017, we were lucky to have Edwina speak here at the museum alongside Bonnie Leake, another groundbreaking woman in railroading, at our ‘Move Over, Sir: Woman Working on the Railroad’ exhibit.

#Edwina Justus#first black female#engineer#black university#womens history month#black history#read more about her#knowledge is power#reading is fundamental

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

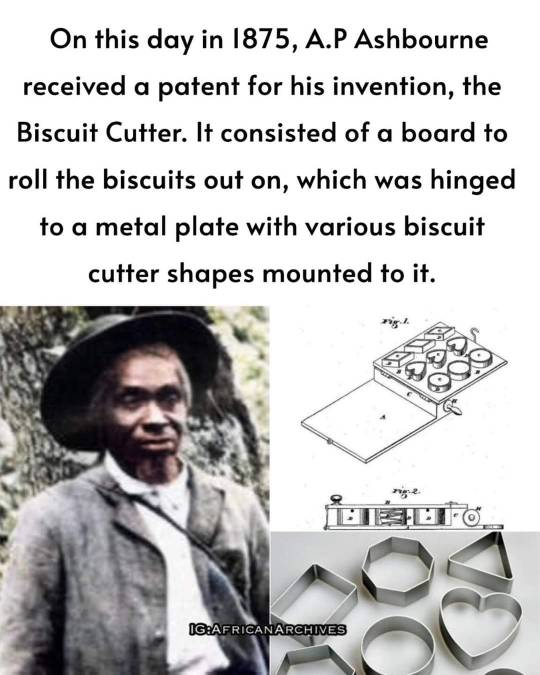

THE WORLD'S FIRST ELECTRIC ROLLER COASTER

Granville T. Woods (April 23, 1856 – January 30, 1910) introduced the “Figure Eight,” the world's first electric roller coaster, in 1892 at Coney Island Amusement Park in New York. Woods patented the invention in 1893, and in 1901, he sold it to General Electric.

Woods was an American inventor who held more than 50 patents in the United States. He was the first African American mechanical and electrical engineer after the Civil War. Self-taught, he concentrated most of his work on trains and streetcars.

In 1884, Woods received his first patent, for a steam boiler furnace, and in 1885, Woods patented an apparatus that was a combination of a telephone and a telegraph. The device, which he called "telegraphony", would allow a telegraph station to send voice and telegraph messages through Morse code over a single wire. He sold the rights to this device to the American Bell Telephone Company.

In 1887, he patented the Synchronous Multiplex Railway Telegraph, which allowed communications between train stations from moving trains by creating a magnetic field around a coiled wire under the train. Woods caught smallpox prior to patenting the technology, and Lucius Phelps patented it in 1884. In 1887, Woods used notes, sketches, and a working model of the invention to secure the patent. The invention was so successful that Woods began the Woods Electric Company in Cincinnati, Ohio, to market and sell his patents. However, the company quickly became devoted to invention creation until it was dissolved in 1893.

Woods often had difficulties in enjoying his success as other inventors made claims to his devices. Thomas Edison later filed a claim to the ownership of this patent, stating that he had first created a similar telegraph and that he was entitled to the patent for the device. Woods was twice successful in defending himself, proving that there were no other devices upon which he could have depended or relied upon to make his device. After Thomas Edison's second defeat, he decided to offer Granville Woods a position with the Edison Company, but Woods declined.

In 1888, Woods manufactured a system of overhead electric conducting lines for railroads modeled after the system pioneered by Charles van Depoele, a famed inventor who had by then installed his electric railway system in thirteen United States cities.

Following the Great Blizzard of 1888, New York City Mayor Hugh J. Grant declared that all wires, many of which powered the above-ground rail system, had to be removed and buried, emphasizing the need for an underground system. Woods's patent built upon previous third rail systems, which were used for light rails, and increased the power for use on underground trains. His system relied on wire brushes to make connections with metallic terminal heads without exposing wires by installing electrical contactor rails. Once the train car had passed over, the wires were no longer live, reducing the risk of injury. It was successfully tested in February 1892 in Coney Island on the Figure Eight Roller Coaster.

In 1896, Woods created a system for controlling electrical lights in theaters, known as the "safety dimmer", which was economical, safe, and efficient, saving 40% of electricity use.

Woods is also sometimes credited with the invention of the air brake for trains in 1904; however, George Westinghouse patented the air brake almost 40 years prior, making Woods's contribution an improvement to the invention.

Woods died of a cerebral hemorrhage at Harlem Hospital in New York City on January 30, 1910, having sold a number of his devices to such companies as Westinghouse, General Electric, and American Engineering. Until 1975, his resting place was an unmarked grave, but historian M.A. Harris helped raise funds, persuading several of the corporations that used Woods's inventions to donate money to purchase a headstone. It was erected at St. Michael's Cemetery in Elmhurst, Queens.

LEGACY

▪Baltimore City Community College established the Granville T. Woods scholarship in memory of the inventor.

▪In 2004, the New York City Transit Authority organized an exhibition on Woods that utilized bus and train depots and an issue of four million MetroCards commemorating the inventor's achievements in pioneering the third rail.

▪In 2006, Woods was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

▪In April 2008, the corner of Stillwell and Mermaid Avenues in Coney Island was named Granville T. Woods Way.

#granville t woods#black inventor#invented#world's first#electric roller coaster#1893#read about him#read about his invention#reading is fundamental#knowledge is power#black history

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edmond Berger had an interest in increasing the efficiency of engines as at the time the internal combustion engine was still fairly new and had poor reliability issues. This is how in 1839 Berger came about to invent the spark plug in France.

A spark plug relies on electricity to pass a spark between two electrodes. This ignites a fuel mixture inside an engine to generate power. Many modern-day internal combustion engines depend on spark plugs. Berger never received a patent for his invention, and there is some debate if the date of his creation is accurate as the internal combustion engine was still in its early stages. This spark plug would have been very experimental at the time. Nevertheless, historians still acknowledge Berger for his trailblazing work in the automotive field.

#Edmond Berger#black inventor#the spark plug#read about him#happy black history month#knowledge is power

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's Black History Month!!!!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coretta Scott was the third of four children born to Obadiah "Obie" Scott (1899–1998) and Bernice McMurry Scott (1904–1996) in Marion, Alabama.

She was born in her parents' home with her paternal great-grandmother Delia Scott, a former slave, presiding as midwife.

Coretta's mother became known for her musical talent and singing voice. As a child Bernice attended the local Crossroads School and only had a fourth grade education. Bernice's older siblings, however, attended boarding school at the Booker T. Washington founded Tuskegee Institute. The senior Mrs. Scott worked as a school bus driver, a church pianist, and for her husband in his business ventures. She served as Worthy Matron for her Eastern Star chapter and was a member of the local Literacy Federated Club.

Obie, Coretta's father, was the first black person in their neighborhood to own a truck. Before starting his own businesses he worked as a fireman. Along with his wife, he ran a barber shop from their home and later opened a general store. He also owned a lumber mill, which was burned down by white neighbors after Scott refused to sell his mill to a white logger.

Her maternal grandparents were Mollie (née Smith; 1868 - d.) and Martin van Buren McMurry (1863 - 1950) - both were of African-American and Irish descent. Mollie was born a slave to plantation owner Jim Blackburn and Adeline (Blackburn) Smith.

Coretta's maternal grandfather, Martin, was born to a slave of Black Native American ancestry, and her white master who never acknowledged Martin as his son. He eventually owned a 280-acre farm.

Because of his diverse origins, Martin appeared to be White; however, he displayed contempt for the notion of passing. As a self-taught reader with little formal education, he is noted for having inspired Coretta's passion for education.

Coretta's paternal grandparents were Cora (née McLaughlin; 1876 - 1920) and Jefferson F. Scott (1873 - 1941). Cora passed away before Coretta's birth. Jeff Scott was a farmer and a prominent figure in the rural black religious community; he was born to former slaves Willis and Delia.

Coretta Scott's parents intended for all of their children to be educated. Coretta quoted her mother as having said, "My children are going to college, even if it means I only have but one dress to put on."

#coretta scott king#her family#descendants#read about her#black history#african american history#knowledge is power

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

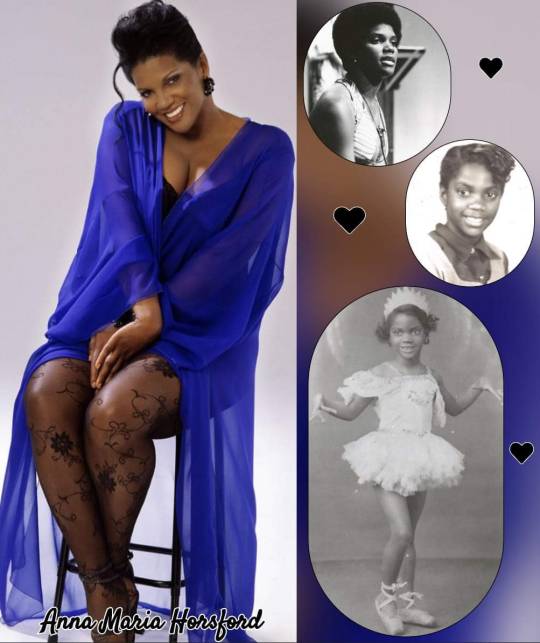

Anna Maria Horsford (born March 6, 1948) is an American actress best known for her roles in the film Friday(1995), as Craig Jones' mother Betty, Thelma Frye on the NBC sitcom Amen (1986–91), and as Dee Baxter on the WB sitcom The Wayans Bros. (1995–99).

She had dramatic roles on the FX crime drama The Shield playing A.D.A. Beth Encardi, and CBS daytime soap opera The Bold and the Beautiful as Vivienne Avant, for which she was nominated for the Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Special Guest Performer in a Drama Series in 2016 and Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Drama Series in 2017.

Horsford appeared in a number of movies, most notable as Craig Jones' mother Betty in 1995 comedy film Friday and its sequel Friday After Next (2002). Her other film credits include Times Square (1980), The Fan (1981), Presumed Innocent (1990), Set It Off (1996), Along Came a Spider (2001), Our Family Wedding (2010), and A Madea Christmas (2013).

Horsford was born in Harlem, New York City to Victor Horsford, an investment real estate broker originally from Barbuda and Lillian Agatha (née Richardson) Horsford, who emigrated from Antigua and Barbuda in the 1940s. She grew up in a family of five children. According to a DNA analysis, she has maternal ancestry from the Limba people of Sierra Leone.

Horsford attended Wadleigh Junior High School and the High School of Performing Arts. After high school, she got into acting through the Harlem Youth for Change program.

Her first job out of high school was with the Joe Papp’s Public Theater, a part in Coriolanus at the Delacorte in Central Park.

On October 29, 2011, Horsford was awarded the title of Ambassador of Tourism of Antigua. She is also a member of Sigma Gamma Rho sorority.

Her first major role in television was as a producer for the PBS show Soul!, hosted by Ellis Haizlip, which aired between 1968 and 1973. One of her first TV appearances was in 1973 on the first run syndication game show of To Tell the Truth where she was an imposter for Laura Livingston, one of the first female military police. Horsford made guest appearances on such sitcoms as The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Sparks, Moesha, The Bernie Mac Show, The Shield, Girlfriends, and Everybody Hates Chris.

Horsford currently has a recurring role as Vivienne Avant on The Bold and the Beautiful. For the role, she was nominated for Outstanding Special Guest Performer in a Drama Series in the 43rd Daytime Emmy Awards.

She began playing a recurring role on B Positive in the show's second-season premiere. She also has appeared in the TBS sitcom The Last O.G. featuring Tracy Morgan, as a recurring character (Tray's mother).

AWARD NOMINATIONS

▪1988 Image Awards (NAACP) Outstanding Lead Actress

in a Comedy Series (Amen)

▪2005 Black Reel Award Best Actress

Network/Cable Television (Justice)

▪2016 Daytime Emmy Award Outstanding Special Guest Performer

in a Drama Series (The Bold and the Beautiful)

▪2017 Daytime Emmy Award Outstanding Supporting Actress

in a Drama Series (The Bold and the Beautiful)

▪2021 Daytime Emmy Award Outstanding Guest Performer

in a Daytime Fiction Program (Studio City)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 •

#wilmington#north carolina#wilmington race riot of 1898#anniversary#read about it#african american history#black history

1 note

·

View note

Text

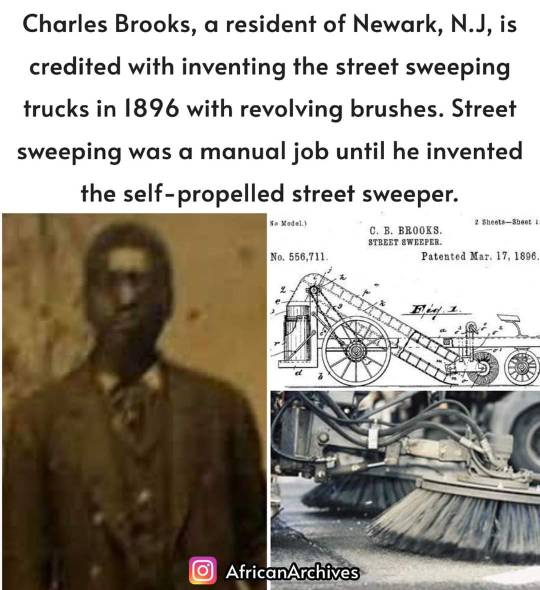

Charles Brooks, a resident of Newark, N.J, is credited with inventing the street sweeping trucks in 1896 with revolving brushes.

Street sweeping was a manual job until he invented the self-propelled street sweeper.

—Street sweeping was often a manual labor job in Brooks' time. Keeping in mind that horses and oxen were the main means of transportation — where there is livestock, there is manure. Rather than stray litter as you might see today in the street, there were piles of manure that needed to be frequently removed regularly. In addition, garbage and the contents of chamber pots would end up in the gutter.

The task of street sweeping was not carried out by mechanical equipment, but rather workers who roamed the street sweeping garbage up with a broom into a receptacle. This method clearly required a lot of labor, although it did provide employment.

#Charles Brooks#black inventor#self propelled#street sweeper#read more about him#reading is fundamental#knowledge is power#black history#african american history

255 notes

·

View notes

Text

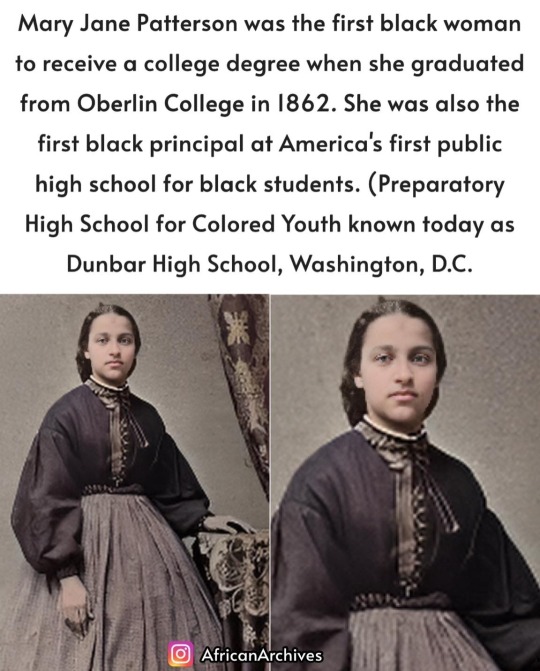

#Mary Jane Patterson#first#black#woman#receive#college degree#oberlin college#principal#read about her#remarkable#knowledge is power

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

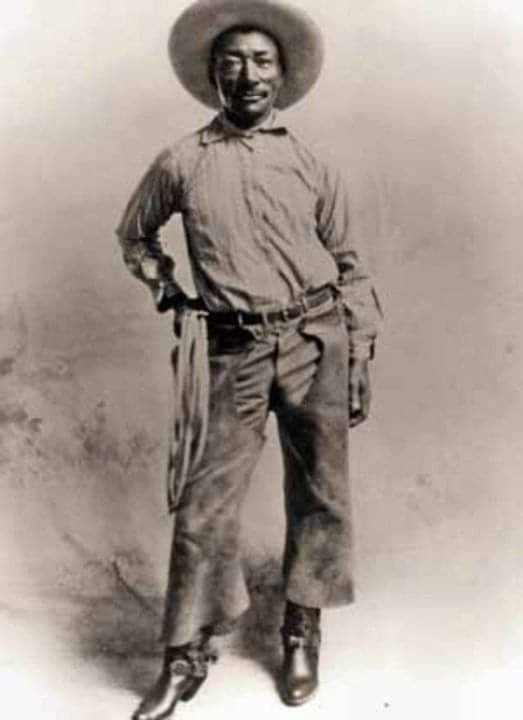

Bill Pickett (ca 1870-1932), African American Cowboy inventor of "bulldogging," a rodeo technique to wrestle a steer to the ground.

From 1905 to 1931, the Miller brothers' 101 Ranch Wild West Show was one of the great shows in the tradition begun by William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody in 1883. The 101 Ranch Show introduced bulldogging (steer wrestling), an exciting rodeo event invented by Bill Pickett, one of the show's stars.

Riding his horse, Spradley, Pickett came alongside a Longhorn steer, dropped to the steer's head, twisted its head toward the sky, and bit its upper lip to get full control. Cowdogs of the Bulldog breed were known to bite the lips of cattle to subdue them. That's how Pickett's technique got the name "bulldogging." As the event became more popular among rodeo cowboys, the lip biting became increasingly less popular until it disappeared from steer wrestling altogether. Bill Pickett, however, became an immortal rodeo cowboy, and his fame has grown since his death.

He died in 1932 as a result of injuries received from working horses at the 101 Ranch. His grave is on what is left of the 101 Ranch property near Ponca City, Oklahoma. Pickett was inducted into the National Rodeo Hall of Fame in 1972 for his contribution to the sport.

Bill Pickett was the second of thirteen children born to Thomas Jefferson and Mary Virginia Elizabeth (Gilbert) Pickett, both of whom were former slaves. He began his career as a cowboy after completing the fifth grade. Bill soon began giving exhibitions of his roping, riding and bulldogging skills, passing a hat for donations.

By 1888, his family had moved to Taylor, Texas, and Bill performed in the town's first fair that year. He and his brothers started a horse-breaking business in Taylor, and Bill was a member of the national guard and a deacon of the Baptist church. In December 1890, Bill married Maggie Turner.

Known by the nicknames "The Dusky Demon" and "The Bull-Dogger," Pickett gave exhibitions in Texas and throughout the West. His performance in 1904 at the Cheyenne Frontier Days (America's best-known rodeo) was considered extraordinary and spectacular. He signed on with the 101 Ranch show in 1905, becoming a full-time ranch employee in 1907. The next year, he moved his wife and children to Oklahoma.

He later performed in the U.S., Canada, Mexico, South America, and England, and became the first black cowboy movie star. Had he not been banned from competing with white rodeo contestants, Pickett might have become one of the greatest record-setters in his sport. He was often identified as an Indian, or some other ethnic background other than black, to be allowed to compete.

Bill Pickett died April 2, 1932, after being kicked in the head by a horse. Famed humorist Will Rogers announced the funeral of his friend on his radio show. In 1989, years after being honored by the National Rodeo Hall of Fame, Pickett was inducted into the Prorodeo Hall of Fame and Museum of the American Cowboy at Colorado Springs, Colorado. A 1994 U.S. postage stamp meant to honor Pickett accidentally showed one of his brothers.

#Bill Pickett#african american#cowboy#inventor#of#bulldogging#rodeo#technique#very talented#read about him#reading is fundamental#black history#knowledge is power

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Solomon Brown: First African American Employee at the Smithsonian Institution

Solomon G. Brown (c.1829–1906) was the first African American employee at the Smithsonian Institution, serving for fifty-four years from 1852 to 1906. During his time at the Smithsonian, he held many titles and performed many duties in service to the Institution. He served under the first three Smithsonian Secretaries, Joseph Henry, Spencer Fullerton Baird, and Samuel P. Langley. He formed a deep personal friendship with Baird which is evident in the letters featured on this page. He also served his community in Anacostia, a part of Washington, DC, and was a prominent advocate of African American progress.

"I have engaged in almost Every Branch of work that is usual and unusual about S.I.," Solomon G. Brown.

These words, written to Secretary Baird on August 12, 1862, encapsulate his long and eclectic career at the Smithsonian Institution. In 1902, he wrote a poem commemorating his fifty years at the Smithsonian —spanning the Institution's formative years. Brown, born a free man when slavery was legal in Washington, DC, joined the staff of the Smithsonian shortly after it was founded in 1846.

Born around 1829, Brown was one of six children. With the unfortunate death of his father in 1833, Brown's chance of attending school and receiving a formal education was over. However, Brown began working for Lambert Tree, assistant postmaster with the DC post office. It was in this capacity that Brown first met Joseph Henry, the Smithsonian's first Secretary. Tree detailed Brown to work with Henry, Samuel B. Morse, and Alfred Vail, while they developed the first magnetic telegraph that ran from DC to Baltimore, Maryland.

In 1852, Brown was hired as a general laborer by the Smithsonian under Henry. Initially, he built exhibit cases, cleaned and moved furniture for the Institution, and shortly became the supervisor of a small group of Smithsonian workers. While working, Brown developed a close relationship with then Assistant Secretary Baird, a naturalist and later second Secretary of the Institution. The two worked together until Baird's death in 1887. Baird trusted Brown implicitly and when out of town, relied on Brown to be his "eyes and ears" of the Institution. Brown and Baird frequently corresponded about the operations of the Smithsonian, city events, and their personal lives, sharing a wry sense of humor about life. From these letters we learn that Brown entertained visitors, handled the mail, made travel arrangements, performed clerical duties, and paid the household staff for the Baird family in addition to his other numerous Smithsonian duties.

Brown also wrote to Baird during the Civil War, reporting on the events occurring around DC and the effects felt by the Smithsonian Institution. He described the dangers to Baird's property and delays in communication from Washington. In 1864, Brown wrote of the Confederate march on the city and his own exemption from the military draft. These letters provide the unique views of a free, African American man on the progress of the Civil War as it raged around him.

Although he lacked a formal education, Brown was considered a Renaissance man. While working for Baird, he educated himself in the field of natural history. He illustrated maps and specimens for many of Baird's lectures, as well as his own talks on topics such as "The Social Habits of Insects," and delivered them to church organizations and civic groups. Not only did he excel as a naturalist, but he was an illustrator, lecturer, philosopher, and poet. Brown also read his poetry, which focused on religion and the social issues of the day, to local audiences and civic organizations. After Baird's death in 1887, Brown served as a clerk for the Smithsonian International Exchange Service, distributing scholarly publications around the world.

Brown's activities also reached beyond the walls of the Smithsonian. Within his own Anacostia (Hillsdale) community, Brown was viewed as a leader. Brown and his wife Lucinda hosted picnics for their local community, one of which was attended by Frederick Douglass. He was elected to the DC House of Delegates, served as superintendent of the Pioneer Sabbath School and the North Washington Mission Sunday school, and was a trustee of the 15th Street Presbyterian Church. He was committed to bettering education and gaining opportunities for African American citizens.

A man of limitless energy, Solomon G. Brown continued to work at the Smithsonian, write and draw, as well as serve his community until his retirement on February 14, 1906. Not long afterward, Brown died at his home on June 24, 1906. Over a century has passed, yet Brown's devotion to the foundation of the Smithsonian is still remembered today. In 2004, several trees were planted around the National Museum of Natural History in his honor.

#Soloman Brown#first african american#employee#smithsonian institution#who knew#learning something new#long article#good read#black history#african american history#read about him#reading is fundamental

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering Billie Holiday (April 7, 1915 - July 17, 1959)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes