#[ what they don’t tell you easily in history is that native children weren’t just forced into trains going to the boarding schools ]

Text

The sad thing is about Wanahton and his children he will have in Red Dead Redemption is that they will never really be safe.

#[ wanahton / musing ] the ghosts of nations are singing.#[ wanahton / v: red dead redemption ] we did not ask for this and yet we must endure or we will die.#[ what they don’t tell you easily in history is that native children weren’t just forced into trains going to the boarding schools ]#[ if the parents fully refused they sometimes kidnapped them off their front yards- from the local school and in their journeys to and from#which is why governmental officials are watched really closely when they come into Anne’s Hearth ]#[ and in his canon his children ARE snatched away before he and Antoinetta literally hunt the train down ]#[ and kill the bastards who did and return the children home ]#[ and end up with another son because the baby was in a literal shoe box under the seat ]#[ and this will be written somehow I don’t care what anyone says ]#[ there is no discussion to be had on this topic because I will not be told again that I can’t write about my peoples history ]#racism /#racism mention /

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

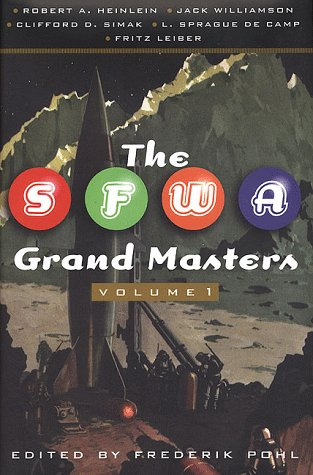

The SFWA Grand Masters,Vol. 1

Edited by Frederik Pohl

Pohl has selected eighteen short stories and novellas written by the first five Grand Masters ever selected by the Science Fiction Writers of America: Robert A. Heinlein, Jack Williamson, Clifford D. Simak, L. Sprague de Camp, and Fritz Leiber. A great debt is owed to Jerry Pournelle for this recognition of the best of the best and to Frederik Pohl for both introducing and reintroducing me to these authors in one handy volume. Actually, in three volumes as I know there is one more to be searched out in the interlibrary world.

Thanks to my library’s willingness to go out of state, I can read the first volume in this series, having started off 2020 with Volume Two. Thank you also to the Woodridge Public Library in Woodridge, Illinois. Now I need to find the third volume. 4 out of 5

We start out with Robert A. Heinlein. I can still remember the first Heinlein that I read, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. My memory is so clear that I can recall to this day seeing it on the library shelf when I was working through a list of Golden Age writers that my father thought I should check out. I understand how controversial he is to many readers, but I always found that his stories were worth reading, even when some of the plotlines were uncomfortable (I’m thinking primarily of Farnham’s Freehold). Even if I didn’t agree with his ideas explored in his books and short stories, they made me think.

“The Roads Must Roll” by Robert A. Heinlein

(Future History 3) The United States had moved from automobiles to solar-powered people movers beginning when oil and gasoline were rationed during World War II. It led to less pollution, a spreading out of the population from the congestion of the cities, and a working class who were ripe for agitation by self-serving megalomaniacs with self-worth issues like Shorty Van Kleeck. It is up to Larry Gaines, the Chief Engineer, to stop the destruction and disruption of the roads. Heinlein is remarkably prescient in this 1940 tale, predicting the congestion of the automobiles and their increasing dangers as well as the importance of solar energy. It’s a shame such people movers, whether this style or high-speed trains are kept from actually being implemented. It is also true that the disenfranchised can be easily manipulated. Just look at our current political environment, not just in the United States and Great Britain. A brilliant tale. I can see the workers being militarized considering how a minor disruption, much less a major one, could not only bring the nation to a halt, it could have serious and deadly ramifications. 4.5 out of 5.

“The Year of the Jackpot” by Robert A. Heinlein

Statistician Potiphar Breen has been taking note of strange and unusual events, including a large number of women taking their clothing off in public. Meade Barstow, the latest befuddled stripper, is seen by Pot. Pot intervenes when the police arrive, offering to take care of her and see her safely home. Instead, when she is worried about what her landlady will say, he brings her to his home so that she can put herself back together. Meade agrees to answer his questions for his kindness. Pot reveals what he believes the numbers are telling him, that the planet is facing something that scares him. Intense, sad, and entirely too realistic. The idea of cycles with world events both good and bad is all too true. The gentle romance between Meade and Pot was a lovely addition. Side note: I was surprised to see the inclusion of transvestites in this story published in 1951. Heinlein treated the couple and the subject in a much nicer manner than I might have expected. I wonder why they were included as they weren't truly needed, nor was the subject of needed for his argument. Others could've sufficed. This was a first time read for me, as is the next story. 4 out of 5.

“Jerry Was a Man” by Robert A. Heinlein

When Martha van Vogel accompanied her husband to a genetics lab that alters DNA to make workers out of apes and vanity pets, she was unaware of how the mutated ape workers were treated once they were no longer useful, that they were euthanized. After raising hell, Martha is allowed to take one of the younger workers, whose eyesight had him put in the death pen, home with her against her husband’s wishes. Refusing to look the other way, Martha fights all the way to court to not only get Jerry free of the lab, but to help keep all the others alive, leading to a precedent making court case. This is an incredibly uncomfortable story on so many fronts. I found it most disturbing that Jerry’s speech pattern is a caricature of poor uneducated blacks. I understand that this was intentional on the part of Heinlein. I’m hoping that it was to give his readers a unique viewpoint into their prejudices, especially considering that the story was copyrighted in 1947. Especially with the return of black American soldiers from World War II to a country that still considered them as less than human. 3.5 out of 5.

“The Farthest Place” by Robert A. Heinlein

(Extract from Tramp Royale) This is non-fiction, an account of the Heinleins and their visit to Tristan da Cunha when the tramp steamer they are on makes a call there. The island is in the South Atlantic, over 1500 miles from the nearest other community. I may have enjoyed this excerpt, but in another context. However, this is a collection of science fiction and fantasy. This particular piece really had no reason to be included. I decline to rate it.

“The Long Watch” by Robert A. Heinlein

Lieutenant Johnny Dahlquist was approached by Colonel Towers regarding the danger of having politicians in control back on Earth, that the Guard should oversee keeping the planet safe. Towers wants Johnny’s expertise as junior bomb officer in his rebellious group. While Johnny saw his point about the instability of politicians in general, he couldn’t agree to use his bombs to make a point, a point that would lead to the deaths of innocent people. He had to make the bombs unusable, then hold watch until a ship from Earth will arrive in approximately four days. This story … Heinlein literally reached into my chest and ripped my heart out. My notebook still shows the faint marks of tears. There are many types of heroism. John Ezra Dahlquist is a fine example of doing what is right even when others try to dissuade you. (You should also look up Rodger Young on Google. I was unaware of this Medal of Honor recipient until this story.) 5 out of 5.

Next is Jack Williamson, another writer from the Golden Age of Science Fiction. And yet, somehow, I never have read any of Jack’s works. Based on these stories, that was a great crime.

“With Folded Hands” by Jack Williamson

(Humanoids .5) Poor Underhill is already struggling to keep his android business afloat. Now a new company has suddenly appeared, providing slick new humanoids that are taking over the town of Two Rivers. His new boarder, Mr. Sledge, claims to be an inventor. The new humanoids are known by him and he appears to be frightened of them. Williamson explores how actions, discoveries, and inventions meant to make man’s life better can sometimes serve to harm him. The story, published in 1947, is even more relevant today considering the growth of A.I.s and robots. This really is as much horror as it is science fiction, terrifying on a deep level for those aware how close we are to this possible future. 3.5 out of 5.

“Jamboree” by Jack Williamson

A robot self-called Pops is Scout Master of boys from birth to the age of 12. Periodically it takes the boys to a Jamboree to meet Mother. Younger boys can indulge in pink ice cream and gold stars plastered on their faces. For the oldest boys, it will be their last Jamboree. But one boy thinks there is a way to stop the cycle. Another tale of robots making decisions for the good of mankind. A very different take. 3.5 out of 5.

“The Manana Literary Society” by Jack Williamson

(Excerpt from Wonder’s Child: My Life in Science Fiction) Another piece of non-fiction, but at least it is about science fiction. Once again, I find it out of place and will not rate it. The selection is, however, a good look at the Los Angeles science fiction scene.

“The Firefly Tree” by Jack Williamson

Forced to move with his family to his grandfather’s farm, the unnamed protagonist is without friends, home-schooled, and lonely. Then he finds an interesting plant that his father calls a weed. He is moved to save the plant from destruction and nurtures it until it grows into a tree. One night he goes out to find the tree covered with fireflies. He begins to dream of them, hearing who they are and what they are there ready to do. Doesn’t Jack ever write happy endings? Any at all? As a child who was a loner and lived in a neighborhood with no children near my age, I could relate to this young boy. Truly engrossing. 3.5 out of 5.

Now on to Clifford D. Simak. I’ve read some of his short stories, but it was a long time ago. I don’t remember much of his style or even whether I liked his works or not.

“Desertion” by Clifford D. Simak

To explore the planet of Jupiter, men are physically converted into one of the more intelligent native species, the Lopers. The last five men sent out by Kent Fowler, the head of the survey project, haven't returned. The exploration must continue, but Fowler can't face sending another man out to what appears to be certain death, so he decides to go in their place, accompanied by his elderly dog. This was a beautiful story. I wish it had been longer. 4 out of 5.

“Founding Father” by Clifford D. Simak

Mankind wants to spread out among the stars, to colonize other planets, but the amount of time that would need to be spent on a spaceship would be an issue. Immortals have no problems with time per se, but the loneliness is another matter. A solution was found, a solution meant to be a temporary fix. But what happens with temporary when that is over one hundred years? Whoa, this might’ve been short, but it was so intense, thought-provoking, and a bit sad. Winston-Kirby will have some decisions to make regarding comfort or duty. 4 out of 5.

“Grotto of the Dancing Deer” by Clifford D. Simak

Archaeologist Boyd discovers a hidden fissure at his latest sight, one filled with fantastical and irreverent art. He also finds something else, something impossible. And yet. Another fascinating story with a deep well of sadness and depressing loneliness in a different way than the previous story. 4 out of 5.

L. Sprague de Camp is a writer that I used to read quite a bit of, mostly his earlier works in short story collections. And the Conan books he finished from Robert Howard’s notes and uncompleted manuscripts. Frankly, I found de Camp’s renditions to be better written, although I know that is heresy for some.

“A Gun for Dinosaur” by L. Sprague de Camp

When a time machine is invented, one that can’t go back to a time more recent than 100,000 years ago, a big part of its users are big game hunters taking clients back to kill a dinosaur for trophy. Rivers, of Rivers and Aiyar, one of those hunters, explains to a potential client why he has strict rules about who he’ll take back to what periods based on size and ability to use a particular caliber weapon. All I can say is poor August, braver than he thought he was, and how Courtney deserved everything he got and more. Entitled asshole. 3.5 out of 5

“Little Green Men from Afar” by L. Sprague de Camp

A non-fiction look into the persistent myths, legends, and outright lies that still garner hopeful believers, from flying saucers to the Bermuda Triangle, Atlantis to cults. I do like the five criteria given by Francis F. Broman regarding any and every story: 1) the report be firsthand; 2) the teller shows no obvious bias or prejudice; 3) that the reporter be a trained observer; 4) that the data be available for checking; and 5) that the teller be clearly identified. I’ve enjoyed many a hour reading von Daniken and the various UFO books, but they have always clearly be put in the fantasy fiction category for me, fun if not taken seriously. Again, no rating for a non-fiction piece in a fiction collection. I’m particularly disappointed as de Camp is left with just two fiction pieces as an introduction to his works.

“Living Fossil” by L. Sprague de Camp

Nawputta, a zoologist, and Chujee, his guide, are searching the Alleghany Mountains for interesting specimans and signs of the cities of Man, long extinct, when they meet a suspicious explorer. They also stumble across something they didn’t expect. Cute. Obvious, but still very fun to read. 3.5 out of 5.

Fritz Leiber is the author of a favorite series from my early 20s. While my father was devouring Conan the Barbarian, I was deep into Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. Strangely enough, I don’t think I read anything else by Leiber in those days or later. So many books, so little time, so few selections at the libraries with whom I had memberships.

“Sanity” by Fritz Leiber

World Manager Carrsbury had researched and planned and schemed for ten years to understand insanity and to replace all the members of the World Management Service with his own people, all of whom had been trained under his exacting guidelines. Just as he had directed the world’s citizens in what they could read, watch, drink, and do in their daily lives. Or so he thought had been done. Leiber’s look at sanity is fascinating and a bit disturbing. Add a backdrop of world government and you have a thoughtful and frightening tale that resonates today. 4 out of 5.

“The Mer She” by Fritz Leiber

(Fafhrd & the Gray Mouser) The Gray Mouser was sailing home to Cif and Fafhrd, his holds filled with treasure and good as befits a successful merchant. When he discovers a stowaway in a chest, he must fight his way through magic if he ever hopes to see his island home again. It has been an extraordinarily long time since I’ve visited this series. The language is as flowery and somewhat archaic as ever, but I missed the boys working together. It just doesn’t have the same punch without that. 3 out of 5.

“A Bad Day for Sales” by Fritz Leiber

Robie, the first sales robot, is on the street, but having a hard time making sales. Then things get a lot worse. Very short, very cute even with that "worse" part. 3.5 out of 5.

#book review#The SFWA Grand Masters#science fiction collection#science fiction#fantasy#Frederik Pohl#Robert A. Heinlein#Jack Williamson#Fritz Leiber#L. Sprague de Camp#Clifford D. Simak#short story collection

1 note

·

View note

Text

Taking Children

An excerpt from Taking Children: A History of American Terror by Laura Briggs

Taking children has been a strategy for terrorizing people for centuries. There is a reason why “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group” is part of international law’s definition of genocide. It participates in the same sadistic political grammar as the torture and murder that separated French Jewish children from their parents under the Nazis and sought to keep enslaved people from rebelling or to keep Native people from retaliating against the Anglos who violated treaties to encroach on their land. Stripping people of their children attempts to deny them the opportunity to participate in the progression of generations into the future — to interrupt the passing down of languages, ways of being, forms of knowledge, foods, cultures. Like enslavement and the Indian Wars, the current efforts by the Trump administration to terrorize asylum seekers is white nationalist in ideology. It is an attempt to secure a white or Anglo future for a nation, a community, a place.

The past stalks the present, the ghost in the machine of memory. This is why history writing matters; it gives us ways to understand the specters already among us and to assemble tools to transform our situation. Things change; the epidemic of child taking in the context of mass incarceration is quite different from separating refugees from their children at the border, but you cannot track the differences without a map of what happened. Writing histories is also a defense against the efforts to implant false memories, the insistence that things happened that did not. The Obama administration did not have a policy of separating children from their parents. Telling history’s story is a way to define it, to put limits on the infinite range of things that might have happened.

Part of the reason this theater of cruelty at the border worked was precisely because of its history. But that is also why it faltered, in the sense that it generated passionate and angry denunciations of, for example, immigrant child detention centers as “concentration camps.” We are primed by memory — by bits of stories handed down across generations, conversations, things read and half-remembered, formal histories, activists’ words and actions, and lies and distortions — to react in certain ways to events in the present. It is not that the histories of child taking repeat or that one set of events parallels another; it is that the past is brought to life in the present. William Faulkner famously evoked this sense of history when he wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Yet for all the anger the policy engendered, the demand for it to end also failed. The administration found a work-around that continued to separate children from their kin and caregivers. Instead of saying that children were being taken because parents were applying for asylum, the Trump administration began saying that it was because they were “neglectful” or dangerous to their children, often with the flimsiest of evidence — a diaper not changed quickly enough, a past criminalized disruption that caused $5 in damage. This, too, was about a failure of historical memory, as opponents failed to mobilize sufficient opposition to the ugly history of the use of “child neglect” to take the children of insurgent communities of color. The administration was reprising a tactic used against welfare mothers, who faced a definition of “child neglect” in the 1950s and ’60s that included having a common-law marriage, a boyfriend sleep over, or an “illegitimate” child. The Trump administration also used the Obama-era tactic of detaining immigrant children with their parents. It called parents criminal — either through a (failed) strategy of naming crossing outside regular border checkpoints to apply for asylum a crime, which courts repeatedly said it was not, or through the more successful efforts to call acts felonies that would be trivial administrative matters if people weren’t migrants, like giving a wrong name to the police. Other immigrants and asylum seekers in fact had criminal records. In the absence of a strong movement to protect the parental rights of those who are or were incarcerated in the United States — immigrants or not — the administration’s work-around, too, served to demobilize the movement to reunite refugee and immigrant children with those who cared for them. Opponents of the policy failed to understand the deep history of the criminalization of parents of color, the way foster care had become a state program of child-taking, and to realize how easily refugee parents could be transformed from harmed innocents to dangerous criminals.

While international and US law make much of the difference between immigrants and refugees, the Trump administration sought to collapse that distinction. Asylum for refugees was a product of the post-World War II response to German concentration camps, and states don’t like it much. Unlike regular immigration, which can to some degree be metered according to the labor needs of a nation or an economy — changing laws to allow more immigrants when more workers are needed, fewer when they aren’t — asylum is understood in international law as a right that follows from being persecuted for one’s ethnicity, race, or political view. The model is Jews under the Nazis, and it was extended to groups like the Hmong in Laos, who were forced to flee because of their aid to the Americans in the war in Southeast Asia. The international asylum system, however, has never worked well in the United States (or a great many other places), and Cold War refugees from politically unpopular left-wing governments, like those from Castro’s Cuba, have been massively favored over refugees from right-wing governments, like those who fled El Salvador in the 1980s. In the eighties and nineties, activists argued that race was a factor as well, with Reagan and the first Bush administration refusing Haitian refugees while accepting largely white Cubans. (Ironically, by 2019, many of the refugees sitting in Mexican shelters awaiting asylum hearings were Cuban. The favoritism did not last.) Bill Clinton campaigned against the distinction that allowed Cubans but not Haitians to petition for asylum in US courts, arguing that everyone had a right to go before a judge to make their case. As soon as he was elected, however, he too began to insist that Haitians couldn’t apply for asylum because they had not reached the land border of the United States, sending them instead to Guantánamo Bay, the US naval base in Cuba. Indeed, Clinton made a mockery of the entire notion of asylum, signing legislation that allowed “expedited” review of such claims, which ensured that people did not set foot in front of a judge but, rather, made their case to an INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service, later ICE) official whose expertise was enforcement, not the finer points of the law.16 George W. Bush and Obama steadily expanded the use of expedited removal, to the point where, by 2013, it accounted for 44 percent of all deportations, compared with only 17 percent that went before a judge.

Taking Children is a book about how we got here. It tells the stories of the detention of children at the US-Mexico border since the presidency of Ronald Reagan, and it also explores four other contexts in the past four centuries where the US state has either taken children as a tactic of terror or tacitly encouraged it. The first is the taking of Black children, beginning with the centuries of racial chattel slavery. Chapter 1 examines slavery and its aftermath through the decades after World War II, when white supremacists sought to dull the moral force of demands for the end of segregation by drawing attention to families and households they tried to paint as pathological: single mothers and their so-called illegitimate children relying on welfare. With the cooperation of the federal government, Southern cities and states put Black children in foster care as punishment for Black adults’ activism against segregation. Chapter 2 investigates the taking of Native children, beginning in the closing decade of the Indian Wars, designed to quiet further revolt. Child taking continued through the emergence of movements for sovereignty and against tribal termination in the middle of the twentieth century. Again, states responded with an aggressive discourse about welfare and illegitimacy, resulting in removal of one in three Native kids from their homes. In response, from 1969 to 1978, tribal councils, the Association on American Indian Affairs, and Native newspapers, newsletters, and radio shows began a campaign for an Indian Child Welfare Act, calling the taking of children the latest episode in centuries of settler colonialism — and they won.

The third episode of children being ripped from their parents and communities I examine in the pages ahead unfolded in the anti-Communist wars in Latin America and their aftershocks. After reprising the better-known cases of disappeared children in Argentina and the Southern Cone, chapter 3 tells the story of Central America: how governments in Guatemala and El Salvador took the children of suspected Communists and placed them for adoption or in institutions to an extent that is still being unearthed. In Honduras, the Reagan administration backed the Contras, a mercenary force seeking to overthrow the government of Nicaragua that happened also to be working with cocaine and marijuana traffickers from Colombia and Mexico, which set in motion much that followed. Within the United States, it sparked the “crack” epidemic, the subject of chapter 4. Crack cocaine justified the launching of a new campaign of harassment of drug users, not just dealers, including massive testing of Black pregnant women and taking their children into foster care in the name of protecting “crack babies.” Native women were caught in a parallel “crisis” that sent them to jail for drinking during pregnancy and sent their children to foster care.

The expansion of cocaine consumption also vastly empowered and armed drug cartels, launching the events that would end in the waves of refugees and asylum seekers that arrived at the borders of the United States in significant numbers beginning in 2013, as we will see in chapter 5. Central America’s Northern Triangle — Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador — had became increasingly unlivable for impoverished people, particularly youth, as the cartels and gangs claimed their neighbors in an ever-accelerating spiral of extortion, kidnapping, violence, and murder.

Taking Children is about a long history in the Americas of interrupting relations of care, kinship, and intimacy, and about how disrupted reproduction produces new regimes of racialized rightlessness. Child taking is, I am arguing, a counterinsurgency tactic has been used to respond to demands for rights, refuge, and respect by communities of color and impoverished communities, an effort to induce hopelessness, despair, grief, and shame.

This is not the whole story, however. There is also a fierce tradition of protesting this practice by the targeted communities and by those who acted in solidarity with them. Many people have found these policies repulsive and abhorrent, and activists, lawyers, and policy makers have sought to reform them. When we forget about the ways that governments have taken children, we also lose a powerful history of communities standing up against that practice, one that has often been quite successful, and provides resources for how to imagine doing it even now. Walter Benjamin wrote urgently about understanding the power of history in this way: “To articulate the past historically does not mean torecognize it ‘the way it really was.’ It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.” Benjamin’s point was that we will never see the past as those who lived it saw it, never grasp it whole, but we don’t have to be troubled by this partial vision. In his view, we need memory — history — for something else, for the way it is useful in the present, in a crisis (he was thinking of fascism).

This work is inspired by social movements’ responses to crisis, including one that Black feminists in the United States have started calling reproductive justice. In recent years, we have seen new protest movements coalesce around missing children — sparked by the mothers (especially, but also fathers and grandparents) of unarmed Black and Latinx youth shot by police or vigilantes — Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, Aiyana Stanley-Jones, Jessie Hernández, Tamir Rice, Rekia Boyd, Antwon Rose, and so many others. In Mexico, a nationwide movement to end state- and police-sanctioned killing by criminal organizations coalesced around the demand by the parents of the young adults disappeared from the Ayotzinapa teacher-training school that they be returned alive. For forty years, some of the most effective opposition to the political right in Latin America has come from family members of the “disappeared,” those arrested or kidnapped by police and para military forces. While most opposition to right-wing governments was dismissed as the work of Communists and “terrorists,” groups like the Comité de Madres Monsignor Romero (Comadres; Committee of Mothers) in El Salvador claimed moral authority by speaking on behalf of disappeared sons and daughters literally in the name of Archbishop (now Saint) Óscar Romero, who was killed by the military while celebrating mass in 1980. In the 1990s, despite Central America’s truth commissions initially refusing to believe that disappeared children and infants were not dead, parents’ groups like Pro Búsqueda began searching for, and sometimes finding, children who had been taken to orphanages and boarding schools — and sometimes adopted abroad. These parents, kin, and caregivers cast the war and the taking of children in a new light, while continuing to fight for a full reckoning for the crimes committed in the name of anti-Communism.

This is the legacy that we carried into the twenty-first century. In the United States, both Democratic and Republican administrations have sought to deter those who lawfully sought asylum by punishing parents as parents and their children. The US government sought to terrify people into not asking for a review of their asylum cases by putting their children in camps, even as it enacted policies that ensured they would come in ever greater numbers. In the pages that follow, this book builds out these stories about how taking children came to seem reasonable, a kind of pain that kept the peace or maintained the status quo, and how people again and again stood up to that violence. Taking children may be as American as a Constitution founded in slavery and the denial of basic citizenship rights to Native people, African Americans, and all women, but activists in every generation have also stood up and said it did not have to be.

Laura Briggs is professor of women, gender, sexuality studies at University of Massachusetts Amherst. She is the author of How All Politics Became Reproductive Politics: From Welfare Reform to Foreclosure to Trump, Somebody’s Children: The Politics of Transracial and Transnational Adoption, and Reproducing Empire: Race, Sex, Science, and U.S. Imperialism in Puerto Rico.

Excerpted from Taking Children: A History of American Terror by Laura Briggs, published by the University of California Press. © 2020.

Article Source

0 notes

Text

“feel you”

thinking about race today can be very overwhelming. but i ask you kindly - do not make something an issue just because it's trendy to take a side. don't come to the cause of colored people just because the stars look pretty outside tonight and now your fleeting thoughts are concerned with how strange it is to feel like things are moving backwards. donate to the aclu if you want to make a change. if you really wanted to make a change that would have already crossed your mind, because your platform almost certainly isn't enough to start a national dialogue, just a circular conversation with someone that doesn't think you have enough credibility to change their mind. i think it's foolish that pence left the game to make a statement, not from a strategic point of view - even though twitter already pointed out how *obvious* of a move it was to increase racial division and reacquaint everyone with a man who maybe wants a little more of that sweet joe biden groupie love - but from the point of view that i don't empathize with the way he feels because i don't feel what he feels. but WOW, do people like to say that they feel you but make no effort at all to broaden their limited perspective.

girls and boys alike, democrats and republicans alike, conservatives and liberals alike.

are you a young college student with a background that ranges anywhere from extremely liberal to slightly conservative, placed in an environment where you lose your credibility if you base your decisions on your feelings?

it's quite obvious, in the midst of a social dialogue, to pick the objectively noble side. but let me tell you something: you didn't know that the national anthem was adopted as a recruitment tool for the military in 2003 before you read it in a 'the Guardian' article last week. you weren't there when a near-death drew bledsoe was replaced on the football field by the greatest quarterback in NFL history after a blood vessel sheared in his chest thinking, "it's important to acknowledge the historicity of the national anthem as well as consider its current context to understand what kind of meaning it once held, what kind of meaning it holds, and how future generations will think about it." if you're vomiting out words and ideas regarding issues serious enough change the course of human history that aren't based on the way you feel about something through your experiences, then consider that you may not be as noble as you're fooling your validation-seeking self to be. based on generation time and changes in the environment, our species doesn't evolve that quickly, and looking at how effortlessly and remorselessly white folk used all kinds of colored folk as a stepladder for their own achievement for hundreds of years, i'm pretty sure there wouldn't be more than 10% of white folk today living in the 1700's willing to walk behind a martin luther king jr archetype in a time where your favorite cook made fish fry to die for and you got to own her once your daddy passed.

a decade passed between the gulf war and the afghanistani war, or the war on terror. we were kids. i was 4. maybe they needed soldiers and the insane people that actually volunteered and fought for a chance that they could make a difference in the lives of innocent middle easterns and americans alike needed help. how sick should do really consider it, in a world where our press secretary blatantly lies about something as benign as the size of an inauguration crowd because his boss is a bit insecure, that uncle sam whispered to the NFL that they should emphasize the national anthem as a way, not to tell the people, but to make them feel in their hearts, that we need help. we are fighting forces unknown to us for results we can't predict except for the "thank you for your service" clockwork we hear at the airport and the lifetime of reaching for your gun and hyperventilating while we walk past the freezer in the supermarket because the buzzing sound in the waffle section reminds us of the sound we heard just before a live grenade exploded outside our bunker, killing a couple of people we didn't know but either of whom we could have easily been. these old politician folk - many of whoms daddy’s and daddy’s daddy’s fought in the military - were on standby, surely out of harms way, but nonetheless facilitating a war against a group they thought was america’s most dangerous enemy. and yes, most of these old politician folk are white, because it's 2017 and change takes time. they don't have friends being killed by white cops or lifelong neighbors being threatened with deportation. it's so clear and obvious to me that protesting the flag is an excellent model for getting a point across that police brutality against black people and colored people is heinous, and the general treatment of all colored folk by police officers is unjustified compared to the way whites are treated by police in 2017.

at the same time, i wasn't fighting in a war in which i wasn't quite sure what i was fighting for or who my enemy was.

at the time, however, perhaps i know that i was fighting for those that called themselves american, whatever their skin color may be, because it's the early 2000's and the general acceptance of colored folk is becoming a social norm. i didn't give my life just to make it feel like the fight i caused was worthless. the decisions conservatives make about abortions, the way they embrace religion, whatever it may be. it's just based on a feeling, a feeling that i can't understand. the unmistakable feeling of being scared in 2003 and giving your thanks by pledging allegiance to your flag. the same grateful and proud feeling when your friends come home safe; the same awful but proud feeling when they don't. you must be proud because you cannot feel like they died in vain, whether they were your friends, your subordinates, your doctor, your wife, your children, whomever. they certainly fought for your right to stand or sit - that's the way i feel as a colored person who feels worthless when his voice is dismissed and forgotten. the way another person, with a different perspective and inseparable feeling, feels when the kneeler hit them where it hurts: the flag. their ultimate symbol. what many they knew died protecting, because they didn't die holding an infant above a flood in a hurricane, but instead they died hoping they made the world more a better place for a bunch of numbers in their telephone book. the problem with establishing feelings based on those who died for a symbol is that symbols are changing, similar to how there’s nothing about the word “horse” that signifies a horse, but it still pops into our head. the difference is symbols outside of language are purposefully malleable to help us understand something we had trouble understanding before we made that comparison. our flag was symbolic of freedom. now it's symbolic of division. the kneeler shits on something intangible that holds meaning forever to the conservative. i may as well be telling that conservative their father is a child molester. that’s just kneeling in front of the flag. but allowing them to make sense of it is the trick. like telling that same conservative that their younger sister was a victim of his father during her adolescence. for a liberal, the murders of innocent blacks and every racial injustice that we accept is the status quo is enough to change our somewhat neutral, if not already negative (based on common liberal feelings regarding unrightful seizure of land from natives, the genocides our forefathers committed, etc.) feelings about the flag to very negative. it’s not as easy when you’re being told that the man you played catch with, let you stay out past curfew, took you to vegas for your 21st, died of emphysema with you next to his hospital bed and left you half of his belongings in his will... it’s not easy to change the way you feel about him. it will happen as the individual naturally adapts and accepts the truth of the world, as it’s too difficult living without accepting truth, but it’s certainly not something that will be dealt with through the passage of logic.

understanding how someone feels when what they think is completely obvious to them when it makes absolutely no sense to you - like why these fucking old conservatives are so closed-minded about the flag - isn't just hard, it's impossible. feelings can't be replicated because feelings are a result of all of your unique thoughts you've had up to a particular moment, every single way you've felt about those thoughts, and all the meta-analyses you did interpreting how you felt about your thoughts. that's what guides your behavior. that's what shapes your values. if you value acknowledging the specific divisiveness of NFL pregames and strategically leave in order to win political points and aggravate the state of our upcoming race war, then i can't say we value the same thing. your feelings are irrational, but so are mine. the flag meant nothing to some in 2003 and it meant everything to others in 2003. now, in 2017, most of the people who couldn't tell you how many stripes are on the flag kneel before it, pleading the rest to do the same, giving the flag a new meaning. but those who already feel the way they feel about what it means... it's not just disrespectful that i kneel, it's appalling that i didn't care then and i do care now. liberals didn't generally support the war on terror. conservatives did. their symbolism was solidified in concrete. they believe the concrete is dry as an act of desperation to give meaning to those who were at biggest risk of dying meaningless. but the concrete never dries. we continue pushing forward by holding on tight to what we know, but also by loosening our grip when we're confronted with something we don't understand, rather than clenching our fist when something challenges the way we feel. because my feelings aren't all rational. and neither are yours. they aren't supposed to be. they’re just genuine. they’re just a result of every process we’ve put ourselves through. and they’re not entirely logical. meaning someone out there will have a more logical perspective on something than you. it’s just up to you to loosen your grip and separate your feelings from your rationale in order to understand the thoughts of another. if you can achieve that, you can see how you feel about adopting their rationale. once you can interpret those feelings, you’ll finally feel what they feel. you’ll have done the impossible.

0 notes