#陰陽術

Photo

2022 art summary

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

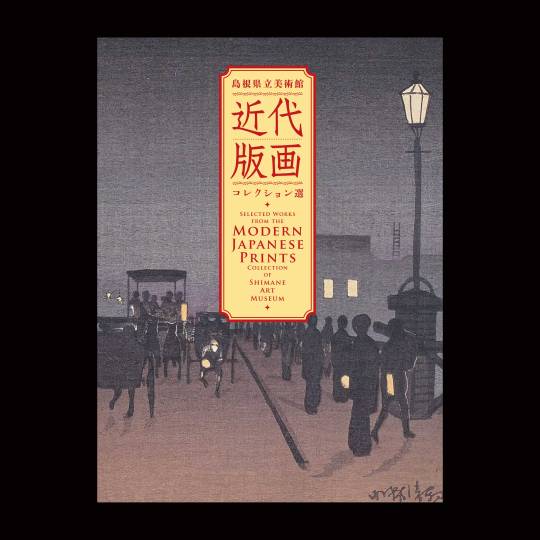

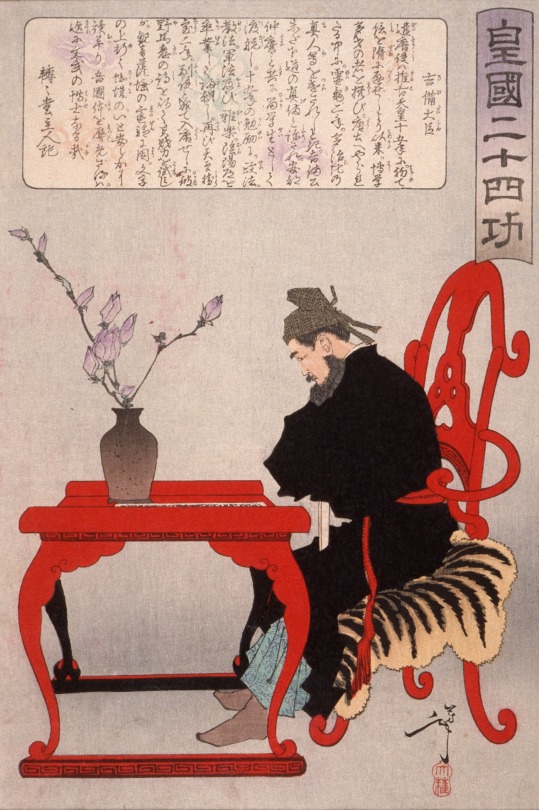

島根県立美術館 近代版画コレクション選 | Selected Works from the Modern Japanese Prints Collection of Shimane Art Museum

『島根県立美術館 近代版画コレクション選』

2013年

発行:島根県立美術館

監修:藤間寛

執筆:田野葉月

編集:田野葉月、福田絵梨子

デザイン:石川陽春

印刷:島根印刷株式会社

製本:日宝綜合製本株式会社

Selected Works from the Modern Japanese Prints Collection of Shimane Art Museum

2013

publisher: Shimane Art Museum, Matsue, Japan

superviser: TOMA Kan

text: TANO Hatsuki

editing: TANO Hatsuki and FUKUDA Eriko

design: ISHIKAWA Kiyoharu

printing: Shimane Printing Co., Ltd.

binding: Noppo Sogo Binding Co., Ltd.

#島根県立美術館#狸坊松江#狸坊出雲#狸坊山陰#版画#本#図録#美術#石川陽春#デザイン#松江#島根#shimaneartmuseum#prints#book#catalog#fineart#ishikawakiyoharu#design#matsue#shimane

0 notes

Text

Vol.163 遺伝子パネル検査はこれからのがん治療のパスポートになる

7月に入って、関東地方は身体に堪える暑さが続いています。もしかしたら、もう梅雨明けしてしまっているのかもしれません。

一方、九州北部は大変な豪雨とのことで、お住まいの方にはお見舞い申し上げます。

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

【記事1】 遺伝子パネル検査はこれからのがん治療のパスポートになる

───────────────────────────────────

遺伝子パネル検査についてはこれまでも何度かメルマガで取り上げてきました。

背景と現状のおさらいですが、、、

・がんを引き起こす様々な遺伝子異常がわかってきた中で、一つ一つの遺伝子異常の有無を調べていく既存のやり方ではキリがないので、まとめて一気に調べる「遺伝子パネル検査」が出てきた

・遺伝子の異常がわかっても、対応する治療薬が存在しない場合が多い。とはいえ、存在する場合はその治療薬を使わなかった場合と比べ、圧倒的に優れた治療効果が期待できる

・現状、日本だと、当該検査の医療費は56万円で、保険が適用されると患者負担はその1-3割

・日本で保険が適用されるのは、「標準治療がない、又は終了する見込みである固形がん」などごく限られたケースで、それも一人一回のみとなっている

さて、この遺伝子パネル検査に関連する論考が出てきました。

■”Universal Germline and Tumor Genomic Testing Needed to Win the War Against Cancer: Genomics Is the Diagnosis”「がんとの闘いに勝つために必要な、生殖細胞系列と腫瘍の普遍的な遺伝子検査:遺伝子は診断である」(Journal of Clinical Oncology)

この論考の中で、首がもげるほど頷けたのが、

「がんとの戦いに本気で勝とうとするならば、がんを治療するためにも、がんを早期に発見するためにも、がんに関するあらゆる情報を得る必要がある。」

という一文です。

今のところ、遺伝子パネル検査が普及していないのはコストの問題が一番大きいわけですが、技術の発展と共に、今後さらにコストは下がっていく可能性が大きいですし、普及すれば患者さんが無駄な検査や治療をするリスクとコストを下げ、治療成績が上がることも期待できます。

折しも、日本では、患者会から遺伝子パネル検査に関する要望書が政府に対して上げられました。

■「『適切なタイミングでのがん遺伝子パネル検査の実施に関する要望書』厚生労働省への提出と財務副大臣への手交のお知らせ」(一般社団法人 全国がん患者団体連合会)

”米国でのがん遺伝子パネル検査については、「全てのStageⅢ、StageⅣの進行再発がん、あるいは再発、再燃、転移がん」の患者さんが対象となっており、初回治療の患者さんを対象にがん遺伝子パネル検査を実施し、その検査結果に基づいて「従来の標準治療の実施」「コンパニオン診断の結果に基づく分子標的薬の投与」「がん遺伝子パネル検査の結果に基づく新たな治療候補薬の選定(治験やコンパッショネートユースなど)」いずれかの治療選択を可能とする「プレシジョン・メディシン(精密医療)」が初回治療から可能となっています”

とあるように、米国の方が一歩進んでいるのが現状です。

日本でも、もう一段遺伝子パネル検査のコストが下がって、誰もが治療の中で何度か使うような「がん治療のパスポート」的な存在になる時代が、���くやってくることを期待したいですね。

※本項執筆時点(2023年7月13日)で、筆者は複数の遺伝子パネル検査機器メーカーの株式を保有しています。

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

【記事2】すったもんだの保険適用:オンコタイプ DX 乳がん再発スコアプログラム

───────────────────────────────────

ホルモン陽性・HER2陰性の早期乳がんの患者さんで、「術後化学療法」を行なうかどうかというのは、これまで医療者にとっても患者にとっても悩みどころでした。

再発リスクは下げたいけれど、術後化学療法での副作用を経験したくないという患者心理がある中で、どのような人であれば術後化学療法をやる必要なしという明確な”線引き”がなかったのです。

そこに出てきたのが「オンコタイプDX」という検査です。腫瘍に関連する21個の遺伝子を解析し、再発リスクを「RS(Recurrent Score)」という形でスコア化します。

現在、乳がん診療ガイドラインでは、Oncotype DXを用いたTAILORx試験の結果に基づき、

「Oncotype DXのRSが25以下の場合には,リンパ節転移陰性であれば術後化学療法を省略することを強く推奨する」

としています。

■「CQ11 ホルモン受容体陽性HER2陰性乳癌に対して,多遺伝子アッセイの結果によって,術後化学療法を省略することは推奨されるか?」(乳癌診療ガイドライン2022年版)

TAILORx試験では、リンパ節転移陰性でRSが25以下の集団は、化学療法をやった場合(化学療法+ホルモン療法)とやらなかった場合(ホルモン療法のみ)で

5年IDFS(再発しないで元気に過ごした患者の比率):93.1% vs 92.8%

で、有意差はなく、化学療法を加えるメリットはないという結果になりました。

ということで、オンコタイプDXを使用する意義も示され、日本でも2021年8月に承認されたわけですが、ここからすったもんだがありました。

■「オンコタイプDXに関するこれまでの経緯と今後の対応について」(厚生労働省)

いやあ、当該企業(エグザクトサイエンス株式会社)に対して完全に怒ってますね、厚生労働省(苦笑)

2021年12月1日までにプログラムの修正を約束していたのに、企業側が守らなかったということで、

「当企業に対しては、厚生労働省に対して、正当な理由なく安定供給が困難な事態を遅滞なく 報告しなかったことから、企業からの再発防止策等の改善策が示されない限り、経済課において今後の保険適用の手続きを留保する。」

とまで書かれてしまってます。

これがようやくのこと、本年9月に保険収載されることになりました。

■「乳がん遺伝子検査、9月から公的医療保険の対象に…3割負担で13万500円」(読売新聞オンライン)

問題が起きてから解決するまでなぜ2年もの時間がかかったのか等、モヤモヤは残りますが、ともかくも正常な環境下でこの検査が普及する体制が整ったことを、まずは歓迎したいと思います。

※本項執筆時点(2023年7月13日)で、筆者はオンコ���イプDXに関して、特筆すべき利益相反はありません。

********************************

「この話についてどう思うか教えて欲しい」というようなご要望、メールマガジンの内容についてのご質問やご意見、解約のご希望などにつきましては、返信の形でお気軽にメールしてください。配信した内容とは無関係の質問でも結構です。必ずお返事いたします。

メールマガジンの内容の引用、紹介、転送も、どんどんやっていただいて構いません。

【お問い合わせ先:[email protected] 】

イシュランの新しい試みとして、がん以外の疾患ですが、病院・医師検索サイト「皮膚ナビ」を作っております。

イシュランと同じく、実際に受診した患者さんの声がコンテンツとなってより充実したサイトに成長していきますので、読者の皆さまにおかれましても、ぜひご自身の経験に基づき、ご存知のクリニックや先生について、投票/投稿して頂けると嬉しいです。

◆皮膚ナビ : https://hifunavi.ishuran.com/

◆SNSもやっています。ぜひフォローよろしくお願いいたします。

・Facebookアカウント:https://www.facebook.com/ishuran.japan

・Twitterアカウント:https://twitter.com/ishuranjapan

・Instagramアカウント:https://www.instagram.com/ishuran_japan/

◆メルマガ会員(会員数 ”6″万人!(2022/12時点)への登録(無料)はこちらから↓

https://www.ishuran.com/my?registration_type=mail

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

科学的根拠に基づきながら一般の方に面白く・わかり易く医療情報を伝えます

お問い合わせ [email protected] 発行・運営 株式会社メディカル・インサイト 鈴木英介

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1 note

·

View note

Photo

首先,我們先了解一下陰陽道(日語:おんみょうどう),源於中國陰陽家五行學說,傳入日本後,逐漸發展成富有特色的一門自然科學與咒術系統,成為日本神道的一部分,同時也是日本法術的代名詞。 史實上的陰陽道,以「天文」「曆法」「漏刻」等為正職,而並行「占卜」「追儺」等事。 人形流 人形流也稱紙人、紙人偶 紙人偶有使用者分身的涵義 陰陽師在平安時代使用的紙人偶,原本屬於宮廷貴族辟邪、頂替自己抵擋咒術 然後用篝火燒掉它或者放到河流上順著河流消失已達到拔除作用。 #陰陽 #陰陽五行 #陰陽師 #陰陽道 #占卜 #道家 #中國 #武術 #易經 🌟 #friends #smile #instagood #life #popularpic #likeforlike #toptags #cute #happy #tbt #girl #fashion #instalike #followme #family #follow (在 Taiwan) https://www.instagram.com/p/ClB7E4lviVB/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#陰陽#陰陽五行#陰陽師#陰陽道#占卜#道家#中國#武術#易經#friends#smile#instagood#life#popularpic#likeforlike#toptags#cute#happy#tbt#girl#fashion#instalike#followme#family#follow

0 notes

Photo

[ 北極假文青 ]台南美術館 - 地獄幽魂展[ Part 3 ] 身為一個鬼片愛好者, 得知台南美術館舉辦了這個展, 我怎麼能夠不去湊一腳? 雖然在開展前就在網路上引起一陣騷動, 支持跟不支持的人吵成一片, 但是吵的越兇, 表示想去看的人越多, 果不其然, 開展的第一天, 就上新聞, 人潮整個擠爆南美二館, 甚至停止賣票, 誰叫陽氣旺盛成那樣! 然後官方也說七月開始, 就要用預約的方式來賣票, 但這對我來說一點也不友善、 這樣的排假實在是綁手綁腳了! 加上剛好六月最後一天有放假, 於是起了個大早, 出發台南排隊看展, 我到現場時約莫在八點半過後, 本來想說應該沒什麼人排隊, 但我錯了, 因為已經有不少的人在排隊了, 然後必須得在大太陽底下等到九點半才會開始發號碼牌, 然後再到櫃檯購票進場。 約莫十點開始放人進場參觀, 參觀時間不長, 只有短短五十五分鐘, 他整個展分成 E:地獄的想像 F:遊返的鬼魂>日本鬼怪:從江戶時期至流行文化 G:遊返的鬼魂>泰國泛靈信仰:森林靈體與披蓬 H:幽靈狩獵 每個展區的詳細內容歡迎到台南美術館的臉書尋找, 這邊放不完, 因為字太多了! H:幽靈狩獵 南美館上映中展覽「亞洲的地獄與幽魂」,自E展間 #地獄的想像、F、G展區 #遊返的鬼魂,徘徊至H展間,以子題 #幽靈狩獵,探討在不同文化脈絡下,人們與亡靈、鬼魂之間如何進行對話,以及關係的演變。 ❝ #祭祀與喪葬儀式,仍是驅逐鬼祟、讓死者轉化為守護神最有效的方式。❞ 從源頭上來說,人們長年來舉辦喪禮和祭祀來 #使死者安息,希望能以此撫慰逝去的魂魄,並引導其轉生。如想要 #驅逐、#獵殺鬼魂,則透過複雜的宗教儀式,人們借助宗教的力量期盼可以擺脫精神及心靈上所被迫脅的 #恐懼感,並且在儀式上附加更多深奧的特性來加固信仰的力量,藉以保護自己、驅趕鬼魂。 符咒、法器、配件、牲禮等等 #連通陰陽的媒介,經過時間及文化的淬鍊流傳至今,警惕世人的所作所為。 此區展示了不同地區 #宗教儀式的力量及寄託。臺灣部分有象徵葬禮及祭祀使用的 #金紙、#傳統紙紮工藝 相關作品,另外妝點在廟宇牌樓處的 #交趾陶,作為 #神鬼與人世之間的紐帶與通道、抑或是想望,以仍然貼近近代日常對於 #未知幽魂的想像與精神,並展現其 #藝術性及歷史意義。 #台南美術館 #地獄與幽魂 #殭屍 #鬼 #幽靈 #迷信 #祭祀 #喪葬 (在 台南美術館2館 Tainan Art Museum Building 2) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cfp1Z1Yv9gA/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#地獄的想像#遊返的鬼魂#幽靈狩獵#祭祀與喪葬儀式#使死者安息#驅逐#獵殺鬼魂#恐懼感#連通陰陽的媒介#宗教儀式的力量及寄託#金紙#傳統紙紮工藝#交趾陶#神鬼與人世之間的紐帶與通道#未知幽魂的想像與精神#藝術性及歷史意義#台南美術館#地獄與幽魂#殭屍#鬼#幽靈#迷信#祭祀#喪葬

0 notes

Photo

. 青花の会 骨董祭からあっという間に一週間が経ちました。 話を繋いで下さった方や手助けをして下さった方がいてご担当の方にも大変お世話になり、自分の計らいを超えた流れとお力により何とか無事に終えることができました。 茶碗や古美術に興味を持つきっかけにもなった青花に関わることになるとは考えたこともありませんでした。こういう自分の意図を超えた力をきっと他力と言うのでしょう。 日常はそこそこ大変でいろんな意味で修行感が拭えない日々なので、もう少し楽にきちんと続けていけるようにしたいという今年の抱負は継続中です。 #青花の会骨董祭 #青花の会 #工芸青花 #骨董祭 #骨董 #古美術 #お茶と食事余珀 #余珀 #恩返しと恩送り #自力と他力 #陰陽 #振り幅 #体脂肪率5パーセント #太る暇がない #修行 #もしくは病気か (√K Contemporary) https://www.instagram.com/p/Ce_VrAfPD8o/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

#尾道市立美術館 #千光寺公園 #lisalarson #リサラーソン #尾道観光 #尾道散歩 #日本 #廣島 #hiroshima #尾道 #201903日本山陽山陰JR旅行 - - - - - #その瞬間に物語を ⠀ #写真好きな人と繋がりたい⠀ #日本の風景 #japen #nippon #visitjapan #followme #travelporn #aphotoaday #everydayinpics #traveladdict #travelinstyle #goseetheworld #holidays #neverstopexploring #liveauthentic #justgotshoot #picoftheday #nothingisordinary https://www.instagram.com/p/CeI6MZkB9uc/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#尾道市立美術館#千光寺公園#lisalarson#リサラーソン#尾道観光#尾道散歩#日本#廣島#hiroshima#尾道#201903日本山陽山陰jr旅行#その瞬間に物語を#写真好きな人と繋がりたい#日本の風景#japen#nippon#visitjapan#followme#travelporn#aphotoaday#everydayinpics#traveladdict#travelinstyle#goseetheworld#holidays#neverstopexploring#liveauthentic#justgotshoot#picoftheday#nothingisordinary

0 notes

Text

Legends of the humanoids

Reptilian humanoids (5)

Wuxing – the connections between the Five Dragon Kings (Ref) and the Five Elements philosophy

To better understand the origins of the Five Dragon Kings and the ancient Chinese legend, it is worth mentioning the wuxing of natural philosophy, which states that all things are composed of five elements: fire, water, wood, metal and earth.

The underlying idea is that the five elements 'influence each other, and that through their birth and death, heaven and earth change and circulate'.

The five elements are described as followed:

Wood/Spring: a period of growth, which generates abundant vitality, movement and wind.

Fire/Summer: a period of swelling, flowering, expanding with heat.

Earth is associated with ripening of grains in the yellow fields of late summer.

Metal/Autumn: a period of harvesting, collecting and dryness.

Water/Winter: a period of retreat, stillness, contracting and coolness.

The wuxing system, in use since the Han dynasty (2nd century BCE), appears in many seemingly disparate fields of early Chinese thought, including music, feng shui, alchemy, astrology, martial arts, military strategy, I Ching divination, and traditional medicine, serving as a metaphysics based on cosmic analogy.

The wuxing originally referred to the five major planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury, Mars and Venus), which were thought of as the five forces that create life on earth. Wu Xing litterally means moving star and describes the five types of Qi (all the vital substances) cycles through various stages of transformation. As yin and yang continuously adjust to one another and transform into one another in a never-ending dance of harmony, they tend to do so in a predictable pattern.

The lists of correlations for the five elements are diverse, but there are two cycles explaining the major interaction. The yin-yang interaction, which by increasing or decreasing the qualities and functions associated with a particular phase, it may either nourish a phase that is in deficiency or drain a phase that is in excess or restrain a phase that is exerting too much influence (see below):

The Creation Cycle (Yang)

Wood feeds Fire

Fire creates Earth (ash)

Earth bears Metal

Metal collects Water

Water nourishes Wood

The Destruction Cycle (Yin)

Wood parts Earth

Earth dams (or absorbs) Water

Water extinguishes Fire

Fire melts Metal

Metal chops Wood

The Huainanzi (2nd BCE) describes the five colored dragons (azure/green, red, white, black, yellow) and their associations (Chapter 4: Terrestrial Forms), as well as the placement of sacred beasts in the five directions (the Four Symbols beasts, dragon, tiger, bird, tortoise in the four cardinal directions and the yellow dragon.

伝説のヒューマノイドたち

ヒト型爬虫類 (5)

五方龍王(参照)と五行思想の関連性

ここで、五方龍王の起源、そして古代中国の伝説をよく理解するために、万物は火・水・木・金・土の5種類の元素からなる、という自然哲学の五行思想について触れておきましょう。 5種類の元素は「互いに影響を与え合い、その生滅盛衰によって天地万物が変化し、循環する」という考えが根底に存在する。

五行は次のように説明されている:

木は、春の豊かな生命力、動き、風を生み出す成長期。

火は、夏の太陽の暖かさの下で行われる成熟の過程、熱で膨張する時期。

土は、晩夏の黄色い野原での穀物の成熟に関連している。

金は、秋の収穫、収集、乾燥の時期。

水は、冬の雪に覆われた暗い大地の中に潜む新しい生命の可能性と静寂の時期。 漢の時代 (紀元前2世紀頃) から使用されてきた五行説は、音楽、風水、錬金術、占星術、武術、軍事戦略、易経、伝統医学など、中国初期の思想の一見バラバラに見える多くの分野に登場し、宇宙の類推に基づく形而上学として機能している。

五行とは文字通り「動く星」を意味し、五種類の気(生命維持に必要なすべての物質)が様々な変容の段階を経て循環することを表している。陰と陽は絶え間なく互いに調整し合い、調和の終わりのないダンスで互いに変化していくため、予測可能なパターンで変化する傾向がある。

五行の相関関係は多様だが、主要な相互作用を説明する2つのサイクルがある。陰陽の相互作用は、特定の相に関連する資質や機能を増減させることで、不足している相に栄養を与えたり、過剰な相を排出したり、影響力を及ぼしすぎている相を抑制したりする (以下参照):

相生(陽)のサイクル

木は燃えて火を生む

火が土 (灰) をつくる

土は金属を産出する

金属は表面に水を集める

水は木を育てる

相克(陰)のサイクル

木は大地を構成する

土は水を堰き止める

水は火を消す

火は金属を溶かす

金属が木を切る

『淮南子』(紀元前2世紀)には、五色の龍(紺碧・緑、赤、白、黒、黄)とその関連性 (第4章: 地の形)、五方位への聖獣の配置(四枢の四象徴獣、龍、虎、鳥、亀、黄龍)が記述されている。

#wuxing#5 dragon kings#5 elements#taoism#yin yang#humanoids#legendary creatures#hybrids#hybrid beasts#cryptids#therianthropy#legend#mythology#folklore#dragon#nature#art

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shikigami and onmyōdō through history: truth, fiction and everything in between

Abe no Seimei exorcising disease spirits (疫病神, yakubyōgami), as depicted in the Fudō Riyaku Engi Emaki. Two creatures who might be shikigami are visible in the bottom right corner (wikimedia commons; identification following Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage, pp. 57-58)

In popular culture, shikigami are basically synonymous with onmyōdō. Was this always the case, though? And what is a shikigami, anyway? These questions are surprisingly difficult to answer. I’ve been meaning to attempt to do so for a longer while, but other projects kept getting in the way. Under the cut, you will finally be able to learn all about this matter.

This isn’t just a shikigami article, though. Since historical context is a must, I also provide a brief history of onmyōdō and some of its luminaries. You will also learn if there were female onmyōji, when stars and time periods turn into deities, what onmyōdō has to do with a tale in which Zhong Kui became a king of a certain city in India - and more!

The early days of onmyōdō

In order to at least attempt to explain what the term shikigami might have originally entailed, I first need to briefly summarize the history of onmyōdō (陰陽道). This term can be translated as “way of yin and yang”, and at the core it was a Japanese adaptation of the concepts of, well, yin and yang, as well as the five elements. They reached Japan through Daoist and Buddhist sources. Daoism itself never really became a distinct religion in Japan, but onmyōdō is arguably among the most widespread adaptations of its principles in Japanese context.

Kibi no Makibi, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (wikimedia commons)

It’s not possible to speak of a singular founder of onmyōdō comparable to the patriarchs of Buddhist schools. Bernard Faure notes that in legends the role is sometimes assigned to Kibi no Makibi, an eighth century official who spent around 20 years in China. While he did bring many astronomical treatises with him when he returned, this is ultimately just a legend which developed long after he passed away.

In reality onmyōdō developed gradually starting with the sixth century, when Chinese methods of divination and treatises dealing with these topics first reached Japan. Early on Buddhist monks from the Korean kingdom of Baekje were the main sources of this knowledge. We know for example that the Soga clan employed such a specialist, a certain Gwalleuk (観勒; alternatively known under the Japanese reading of his name, Kanroku).

Obviously, divination was viewed as a very serious affair, so the imperial court aimed to regulate the continental techniques in some way. This was accomplished by emperor Tenmu with the formation of the onmyōryō (陰陽寮), “bureau of yin and yang” as a part of the ritsuryō system of governance. Much like in China, the need to control divination was driven by the fears that otherwise it would be used to legitimize courtly intrigues against the emperor, rebellions and other disturbances.

Officials taught and employed by onmyōryō were referred to as onmyōji (陰陽師). This term can be literally translated as “yin-yang master”. In the Nara period, they were understood essentially as a class of public servants. Their position didn’t substantially differ from that of other specialists from the onmyōryō: calendar makers, officials responsible for proper measurement of time and astrologers. The topics they dealt with evidently weren’t well known among commoners, and they were simply typical members of the literate administrative elite of their times.

Onmyōdō in the Heian period: magic, charisma and nobility

The role of onmyōji changed in the Heian period. They retained the position of official bureaucratic diviners in employ of the court, but they also acquired new duties. The distinction between them and other onmyōryō officials became blurred. Additionally their activity extended to what was collectively referred to as jujutsu (呪術), something like “magic” though this does not fully reflect the nuances of this term. They presided over rainmaking rituals, purification ceremonies, so-called “earth quelling”, and establishing complex networks of temporal and directional taboos.

A Muromachi period depiction of Abe no Seimei (wikimedia commons)

The most famous historical onmyōji like Kamo no Yasunori and his student Abe no Seimei were active at a time when this version of onmyōdō was a fully formed - though obviously still evolving - set of practices and beliefs. In a way they represented a new approach, though - one in which personal charisma seemed to matter just as much, if not more, than official position. This change was recognized as a breakthrough by at least some of their contemporaries. For example, according to the diary of Minamoto no Tsuneyori, the Sakeiki (左經記), “in Japan, the foundations of onmyōdō were laid by Yasunori”.

The changes in part reflected the fact that onmyōji started to be privately contracted for various reasons by aristocrats, in addition to serving the state. Shin’ichi Shigeta notes that it essentially turned them from civil servants into tradespeople. However, he stresses they cannot be considered clergymen: their position was more comparable to that of physicians, and there is no indication they viewed their activities as a distinct religion. Indeed, we know of multiple Heian onmyōji, like Koremune no Fumitaka or Kamo no Ieyoshi, who by their own admission were devout Buddhists who just happened to work as professional diviners.

Shin’ichi Shigeta notes is evidence that in addition to the official, state-sanctioned onmyōji, “unlicensed” onmyōji who acted and dressed like Buddhist clergy, hōshi onmyōji (法師陰陽師) existed. The best known example is Ashiya Dōman, a mainstay of Seimei legends, but others are mentioned in diaries, including the famous Pillow Book. It seems nobles particularly commonly employed them to curse rivals. This was a sphere official onmyōji abstained from due to legal regulations. Curses were effectively considered crimes, and government officials only performed apotropaic rituals meant to protect from them.

The Heian period version of onmyōdō captivated the imagination of writers and artists, and its slightly exaggerated version present in classic literature like Konjaku Monogatari is essentially what modern portrayals in fiction tend to go back to.

Medieval onmyōdō: from abstract concepts to deities

Gozu Tennō (wikimedia commons)

Further important developments occurred between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. This period was the beginning of the Japanese “middle ages” which lasted all the way up to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. The focus in onmyōdō in part shifted towards new, or at least reinvented, deities, such as calendarical spirits like Daishōgun (大将軍) and Ten’ichijin (天一神), personifications of astral bodies and concepts already crucial in earlier ceremonies. There was also an increased interest in Chinese cosmological figures like Pangu, reimagined in Japan as “king Banko”. However, the most famous example is arguably Gozu Tennō, who you might remember from my Susanoo article.

The changes in medieval onmyōdō can be described as a process of convergence with esoteric Buddhism. The points of connection were rituals focused on astral and underworld deities, such as Taizan Fukun or Shimei (Chinese Siming). Parallels can be drawn between this phenomenon and the intersection between esoteric Buddhism and some Daoist schools in Tang China. Early signs of the development of a direct connection between onmyōdō and Buddhism can already be found in sources from the Heian period, for example Kamo no Yasunori remarked that he and other onmyōji depend on the same sources to gain proper understanding of ceremonies focused on the Big Dipper as Shingon monks do.

Much of the information pertaining to the medieval form of onmyōdō is preserved in Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), a text which is part divination manual and part a collection of myths. According to tradition it was compiled by Abe no Seimei, though researchers generally date it to the fourteenth century. For what it’s worth, it does seem likely its author was a descendant of Seimei, though.

Outside of specialized scholarship Hoki Naiden is fairly obscure today, but it’s worth noting that it was a major part of the popular perception of onmyōdō in the Edo period. A novel whose influence is still visible in the modern image of Seimei, Abe no Seimei Monogatari (安部晴明物語), essentially revolves around it, for instance.

Onmyōdō in the Edo period: occupational licensing

Novels aside, the first post-medieval major turning point for the history of onmyōdō was the recognition of the Tsuchimikado family as its official overseers in 1683. They were by no means new to the scene - onmyōji from this family already served the Ashikaga shoguns over 250 years earlier. On top of that, they were descendants of the earlier Abe family, the onmyōji par excellence. The change was not quite the Tsuchimikado’s rise, but rather the fact the government entrusted them with essentially regulating occupational licensing for all onmyōji, even those who in earlier periods existed outside of official administration.

As a result of the new policies, various freelance practitioners could, at least in theory, obtain a permit to perform the duties of an onmyōji. However, as the influence of the Tsuchimikado expanded, they also sought to oblige various specialists who would not be considered onmyōji otherwise to purchase licenses from them. Their aim was to essentially bring all forms of divination under their control. This extended to clergy like Buddhist monks, shugenja and shrine priests on one hand, and to various performers like members of kagura troupes on the other.

Makoto Hayashi points out that while throughout history onmyōji has conventionally been considered a male occupation, it was possible for women to obtain licenses from the Tsuchimikado. Furthermore, there was no distinct term for female onmyōji, in contrast with how female counterparts of Buddhist monks, shrine priests and shugenja were referred to with different terms and had distinct roles defined by their gender.

As far as I know there’s no earlier evidence for female onmyōji, though, so it’s safe to say their emergence had a lot to do with the specifics of the new system. It seems the poems of the daughter of Kamo no Yasunori (her own name is unknown) indicate she was familiar with yin-yang theory or at least more broadly with Chinese philosophy, but that’s a topic for a separate article (stay tuned), and it's not quite the same, obviously.

The Tsuchimikado didn’t aim to create a specific ideology or systems of beliefs. Therefore, individual onmyōji - or, to be more accurate, individual people with onmyōji licenses - in theory could pursue new ideas. This in some cases lead to controversies: for instance, some of the people involved in the (in)famous 1827 Osaka trial of alleged Christians (whether this label really is applicable is a matter of heated debate) were officially licensed onmyōji. Some of them did indeed possess translated books written by Portuguese missionaries, which obviously reflected Catholic outlook. However, Bernard Faure suggests that some of the Edo period onmyōji might have pursued Portuguese sources not strictly because of an interest in Catholicism but simply to obtain another source of astronomical knowledge.

The legacy of onmyōdō

In the Meiji period, onmyōdō was banned alongside shugendō. While the latter tradition experienced a revival in the second half of the twentieth century, the former for the most part didn’t. However, that doesn’t mean the history of onmyōdō ends once and for all in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Even today in some parts of Japan there are local religious traditions which, while not identical with historical onmyōdō, retain a considerable degree of influence from it. An example often cited in scholarship is Izanagi-ryū (いざなぎ流) from the rural Monobe area in the Kōchi Prefecture. Mitsuki Ueno stresses that the occasional references to Izanagi-ryū as “modern onmyōdō” in literature from the 1990s and early 2000s are inaccurate, though. He points out they downplay the unique character of this tradition, and that it shows a variety of influences. Similar arguments have also been made regarding local traditions from the Chūgoku region.

Until relatively recently, in scholarship onmyōdō was basically ignored as superstition unworthy of serious inquiries. This changed in the final decades of the twentieth century, with growing focus on the Japanese middle ages among researchers. The first monographs on onmyōdō were published in the 1980s. While it’s not equally popular as a subject of research as esoteric Buddhism and shugendō, formerly neglected for similar reasons, it has nonetheless managed to become a mainstay of inquiries pertaining to the history of religion in Japan.

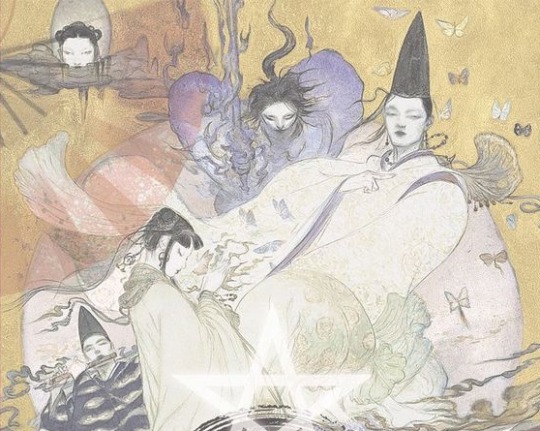

Yoshitaka Amano's illustration of Baku Yumemakura's fictionalized portrayal of Abe no Seimei (right) and other characters from his novels (reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Of course, it’s also impossible to talk about onmyōdō without mentioning the modern “onmyōdō boom”. Starting with the 1980s, onmyōdō once again became a relatively popular topic among writers. Novel series such as Baku Yumemakura’s Onmyōji, Hiroshi Aramata’s Teito Monogatari or Natsuhiko Kyōgoku’s Kyōgōkudō and their adaptations in other media once again popularized it among general audiences. Of course, since these are fantasy or mystery novels, their historical accuracy tends to vary (Yumemakura in particular is reasonably faithful to historical literature, though). Still, they have a lasting impact which would be impossible to accomplish with scholarship alone.

Shikigami: historical truth, historical fiction, or both?

You might have noticed that despite promising a history of shikigami, I haven’t used this term even once through the entire crash course in history of onmyōdō. This was a conscious choice. Shikigami do not appear in any onmyōdō texts, even though they are a mainstay of texts about onmyōdō, and especially of modern literature involving onmyōji.

It would be unfair to say shikigami and their prominence are merely a modern misconception, though. Virtually all of the famous legends about onmyōji feature shikigami, starting with the earliest examples from the eleventh century. Based on Konjaku Monogatari, there evidently was a fascination with shikigami at the time of its compilation. Fujiwara no Akihira in the Shinsarugakuki treats the control of shikigami as an essential skill of an onmyōji, alongside the abilities to “freely summon the twelve guardian deities, call thirty-six types of wild birds (...), create spells and talismans, open and close the eyes of kijin (鬼神; “demon gods”), and manipulate human souls”.

It is generally agreed that such accounts, even though they belong to the realm of literary fiction, can shed light on the nature and importance of shikigami. They ultimately reflect their historical context to some degree. Furthermore, it is not impossible that popular understanding of shikigami based on literary texts influenced genuine onmyōdō tradition. It’s worth pointing out that today legends about Abe no Seimei involving them are disseminated by two contemporary shrines dedicated to him, the Seimei Shrine (晴明神社) in Kyoto and the Abe no Seimei Shrine (安倍晴明神社) in Osaka. Interconnected networks of exchange between literature and religious practice are hardly a unique or modern phenomenon.

However, even with possible evidence from historical literature taken into account, it is not easy to define shikigami. The word itself can be written in three different ways: 式神 (or just 式), 識神 and 職神, with the first being the default option. The descriptions are even more varied, which understandably lead to the rise of numerous interpretations in modern scholarship. Carolyn Pang in her recent treatments of shikigami, which you can find in the bibliography, has recently divided them into five categories. I will follow her classification below.

Shikigami take 1: rikujin-shikisen

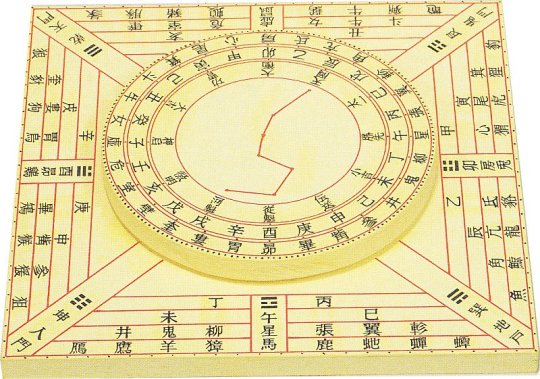

An example of shikiban, the divination board used in rikujin-shikisen (Museum of Kyoto, via onmarkproductions.com; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

A common view is that shikigami originate as a symbolic representation of the power of shikisen (式占) or more specifically rikujin-shikisen (六壬式占), the most common form of divination in onmyōdō. It developed from Chinese divination methods in the Nara period, and remained in the vogue all the way up to the sixteenth century, when it was replaced by ekisen (易占), a method derived from the Chinese Book of Changes.

Shikisen required a special divination board known as shikiban (式盤), which consists of a square base, the “earth panel” (地盤, jiban), and a rotating circle placed on top of it, the “heaven panel” (天盤, tenban). The former was marked with twelve points representing the signs of the zodiac and the latter with representations of the “twelve guardians of the months” (十二月将, jūni-gatsushō; their identity is not well defined). The heaven panel had to be rotated, and the diviner had to interpret what the resulting combination of symbols represents. Most commonly, it was treated as an indication whether an unusual phenomenon (怪/恠, ke) had positive or negative implications.

It’s worth pointing out that in the middle ages the shikiban also came to be used in some esoteric Buddhist rituals, chiefly these focused on Dakiniten, Shōten and Nyoirin Kannon. However, they were only performed between the late Heian and Muromachi periods, and relatively little is known about them. In most cases the divination board was most likely modified to reference the appropriate esoteric deities.

Shikigami take 2: cognitive abilities

While the view that shikigami represented shikisen is strengthened by the fact both terms share the kanji 式, a variant writing, 識神, lead to the development of another proposal. Since the basic meaning of 識 is “consciousness”, it is sometimes argued that shikigami were originally an “anthropomorphic realization of the active psychological or mental state”, as Caroline Pang put it - essentially, a representation of the will of an onmyōji. Most of the potential evidence in this case comes from Buddhist texts, such as Bosatsushotaikyō (菩薩処胎経).

However, Bernard Faure assumes that the writing 識神 was a secondary reinterpretation, basically a wordplay based on homonymy. He points out the Buddhist sources treat this writing of shikigami as a synonym of kushōjin (倶生神). This term can be literally translated as “deities born at the same time”. Most commonly it designates a pair of minor deities who, as their name indicates, come into existence when a person is born, and then records their deeds through their entire life. Once the time for Enma’s judgment after death comes, they present him with their compiled records. It has been argued that they essentially function like a personification of conscience.

Shikigami take 3: energy

A further speculative interpretation of shikigami in scholarship is that this term was understood as a type of energy present in objects or living beings which onmyōji were believed to be capable of drawing out and harnessing to their ends. This could be an adaptation of the Daoist notion of qi (氣). If this definition is correct, pieces of paper or wooden instruments used in purification ceremonies might be examples of objects utilized to channel shikigami.

The interpretation of shikigami as a form of energy is possibly reflected in Konjaku Monogatari in the tale The Tutelage of Abe no Seimei under Tadayuki. It revolves around Abe no Seimei’s visit to the house of the Buddhist monk Kuwanten from Hirosawa. Another of his guests asks Seimei if he is capable of killing a person with his powers, and if he possesses shikigami. He affirms that this is possible, but makes it clear that it is not an easy task. Since the guests keep urging him to demonstrate nonetheless, he promptly demonstrates it using a blade of grass. Once it falls on a frog, the animal is instantly crushed to death. From the same tale we learn that Seimei’s control over shikigami also let him remotely close the doors and shutters in his house while nobody was inside.

Shikigami take 4: curse

As I already mentioned, arts which can be broadly described as magic - like the already mentioned jujutsu or juhō (呪法, “magic rituals”) - were regarded as a core part of onmyōji’s repertoire from the Heian period onward. On top of that, the unlicensed onmyōji were almost exclusively associated with curses. Therefore, it probably won’t surprise you to learn that yet another theory suggests shikigami is simply a term for spells, curses or both. A possible example can be found in Konjaku Monogatari, in the tale Seimei sealing the young Archivist Minor Captains curse - the eponymous curse, which Seimei overcomes with protective rituals, is described as a shikigami.

Kunisuda Utagawa's illustration of an actor portraying Dōman in a kabuki play (wikimedia commons)

Similarities between certain descriptions of shikigami and practices such as fuko (巫蠱) and goraihō (五雷法) have been pointed out. Both of these originate in China. Fuko is the use of poisonous, venomous or otherwise negatively perceived animals to create curses, typically by putting them in jars, while goraihō is the Japanese version of Daoist spells meant to control supernatural beings, typically ghosts or foxes. It’s worth noting that a legend according to which Dōman cursed Fujiwara no Michinaga on behalf of lord Horikawa (Fujiwara no Akimitsu) involves him placing the curse - which is itself not described in detail - inside a jar.

Mitsuki Ueno notes that in the Kōchi Prefecture the phrase shiki wo utsu, “to strike with a shiki”, is still used to refer to cursing someone. However, shiki does not necessarily refer to shikigami in this context, but rather to a related but distinct concept - more on that later.

Shikigami take 5: supernatural being

While all four definitions I went through have their proponents, yet another option is by far the most common - the notion of shikigami being supernatural beings controlled by an onmyōji. This is essentially the standard understanding of the term today among general audiences. Sometimes attempts are made to identify it with a specific category of supernatural beings, like spirits (精霊, seirei), kijin or lesser deities (下級神, kakyū shin). However, none of these gained universal support. Generally speaking, there is no strong indication that shikigami were necessarily imagined as individualized beings with distinct traits.

The notion of shikigami being supernatural beings is not just a modern interpretation, though, for the sake of clarity. An early example where the term is unambiguously used this way is a tale from Ōkagami in which Seimei sends a nondescript shikigami to gather information. The entity, who is not described in detail, possesses supernatural skills, but simultaneously still needs to open doors and physically travel.

An illustration from Nakifudō Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

In Genpei Jōsuiki there is a reference to Seimei’s shikigami having a terrifying appearance which unnerved his wife so much he had to order the entities to hide under a bride instead of residing in his house. Carolyn Pang suggests that this reflects the demon-like depictions from works such as Abe no Seimei-kō Gazō (安倍晴明公画像; you can see it in the Heian section), Fudōriyaku Engi Emaki and Nakifudō Engi Emaki.

Shikigami and related concepts

A gohō dōji, as depicted in the Shigisan Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

The understanding of shikigami as a “spirit servant” of sorts can be compared with the Buddhist concept of minor protective deities, gohō dōji (護法童子; literally “dharma-protecting lads”). These in turn were just one example of the broad category of gohō (護法), which could be applied to virtually any deity with protective qualities, like the historical Buddha’s defender Vajrapāṇi or the Four Heavenly Kings.

A notable difference between shikigami and gohō is the fact that the former generally required active summoning - through chanting spells and using mudras - while the latter manifested on their own in order to protect the pious. Granted, there are exceptions. There is a well attested legend according to which Abe no Seimei’s shikigami continued to protect his residence on own accord even after he passed away. Shikigami acting on their own are also mentioned in Zoku Kojidan (続古事談). It attributes the political downfall of Minamoto no Takaakira (源高明; 914–98) to his encounter with two shikigami who were left behind after the onmyōji who originally summoned them forgot about them.

A degree of overlap between various classes of supernatural helpers is evident in texts which refer to specific Buddhist figures as shikigami. I already brought up the case of the kushōjin earlier. Another good example is the Tendai monk Kōshū’s (光宗; 1276–1350) description of Oto Gohō (乙護法). He is “a shikigami that follows us like the shadow follows the body. Day or night, he never withdraws; he is the shikigami that protects us” (translation by Bernard Faure). This description is essentially a reversal of the relatively common title “demon who constantly follow beings” (常随魔, jōzuima). It was applied to figures such as Kōjin, Shōten or Matarajin, who were constantly waiting for a chance to obstruct rebirth in a pure land if not placated properly.

The Twelve Heavenly Generals (Tokyo National Museum, via wikimedia commons)

A well attested group of gohō, the Twelve Heavenly Generals (十二神将, jūni shinshō), and especially their leader Konpira (who you might remember from my previous article), could be labeled as shikigami. However, Fujiwara no Akihira’s description of onmyōji skills evidently presents them as two distinct classes of beings.

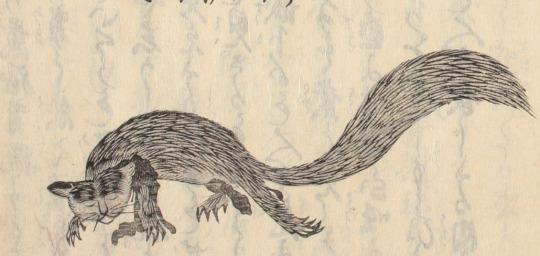

A kuda-gitsune, as depicted in Shōzan Chomon Kishū by Miyoshi Shōzan (Waseda University History Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Granted, Akihira also makes it clear that controlling shikigami and animals are two separate skills. Meanwhile, there is evidence that in some cases animal familiars, especially kuda-gitsune used by iizuna (a term referring to shugenja associated with the cult of, nomen omen, Iizuna Gongen, though more broadly also something along the lines of “sorcerer”), were perceived as shikigami.

Beliefs pertaining to gohō dōji and shikigami seemingly merged in Izanagi-ryū, which lead to the rise of the notion of shikiōji (式王子; ōji, literally “prince”, can be another term for gohō dōji). This term refers to supernatural beings summoned by a ritual specialist (祈祷師, kitōshi) using a special formula from doctrinal texts (法文, hōmon). They can fulfill various functions, though most commonly they are invoked to protect a person, to remove supernatural sources of diseases, to counter the influence of another shikiōji or in relation to curses.

Tenkeisei, the god of shikigami

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

The final matter which warrants some discussion is the unusual tradition regarding the origin of shikigami which revolves around a deity associated with this concept.

In the middle ages, a belief that there were exactly eighty four thousand shikigami developed. Their source was the god Tenkeisei (天刑星; also known as Tengyōshō). His name is the Japanese reading of Chinese Tianxingxing. It can be translated as “star of heavenly punishment”. This name fairly accurately explains his character. He was regarded as one of the so-called “baleful stars” (凶星, xiong xing) capable of controlling destiny. The “punishment” his name refers to is his treatment of disease demons (疫鬼, ekiki). However, he could punish humans too if not worshiped properly.

Today Tenkeisei is best known as one of the deities depicted in a series of paintings known as Extermination of Evil, dated to the end of the twelfth century. He has the appearance of a fairly standard multi-armed Buddhist deity. The anonymous painter added a darkly humorous touch by depicting him right as he dips one of the defeated demons in vinegar before eating him. Curiously, his adversaries are said to be Gozu Tennō and his retinue in the accompanying text. This, as you will quickly learn, is a rather unusual portrayal of the relationship between these two deities.

I’m actually not aware of any other depictions of Tenkeisei than the painting you can see above. Katja Triplett notes that onmyōdō rituals associated with him were likely surrounded by an aura of secrecy, and as a result most depictions of him were likely lost or destroyed. At the same time, it seems Tenkeisei enjoyed considerable popularity through the Kamakura period. This is not actually paradoxical when you take the historical context into account: as I outlined in my recent Amaterasu article, certain categories of knowledge were labeled as secret not to make their dissemination forbidden, but to imbue them with more meaning and value.

Numerous talismans inscribed with Tenkeisei’s name are known. Furthermore, manuals of rituals focused on him have been discovered. The best known of them, Tenkeisei-hō (天刑星法; “Tenkeisei rituals”), focuses on an abisha (阿尾捨, from Sanskrit āveśa), a ritual involving possession by the invoked deity. According to a legend was transmitted by Kibi no Makibi and Kamo no Yasunori. The historicity of this claim is doubtful, though: the legend has Kamo no Yasunori visit China, which he never did. Most likely mentioning him and Makibi was just a way to provide the text with additional legitimacy.

Other examples of similar Tenkeisei manuals include Tenkeisei Gyōhō (天刑星行法; “Methods of Tenkeisei Practice”) and Tenkeisei Gyōhō Shidai (天刑星行法次第; “Methods of Procedure for the Tenkeisei Practice”). Copies of these texts have been preserved in the Shingon temple Kōzan-ji.

The Hoki Naiden also mentions Tenkeisei. It equates him with Gozu Tennō, and explains both of these names refer to the same deity, Shōki (商貴), respectively in heaven and on earth. While Shōki is an adaptation of the famous Zhong Kui, it needs to be pointed out that here he is described not as a Tang period physician but as an ancient king of Rajgir in India. Furthermore, he is a yaksha, not a human. This fairly unique reinterpretation is also known from the historical treatise Genkō Shakusho.

Post scriptum

The goal of this article was never to define shikigami. In the light of modern scholarship, it’s basically impossible to provide a single definition in the first place. My aim was different: to illustrate that context is vital when it comes to understanding obscure historical terms. Through history, shikigami evidently meant slightly different things to different people, as reflected in literature. However, this meaning was nonetheless consistently rooted in the evolving perception of onmyōdō - and its internal changes. In other words, it reflected a world which was fundamentally alive.

The popular image of Japanese culture and religion is often that of an artificial, unchanging landscape straight from the “age of the gods”, largely invented in the nineteenth century or later to further less than noble goals. The case of shikigami proves it doesn’t need to be, though. The malleable, ever-changing image of shikigami, which remained a subject of popular speculation for centuries before reemerging in a similar role in modern times, proves that the more complex reality isn’t necessarily any less interesting to new audiences.

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, A Religion in Search of a Founder?

Idem, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Makoto Hayashi, The Female Christian Yin-Yang Master

Jun’ichi Koike, Onmyōdō and Folkloric Culture: Three Perspectives for the Development of Research

Irene H. Lin, Child Guardian Spirits (Gohō Dōji) in the Medieval Japanese Imaginaire

Yoshifumi Nishioka, Aspects of Shikiban-Based Mikkyō Rituals

Herman Ooms, Yin-Yang's Changing Clientele, 600-800 (note there is n apparent mistake in one of the footnotes, I'm pretty sure the author wanted to write Mesopotamian astronomy originated 4000 years ago, not 4 millenia BCE as he did; the latter date makes little sense)

Carolyn Pang, Spirit Servant: Narratives of Shikigami and Onmyōdō Developments

Idem, Uncovering Shikigami. The Search for the Spirit Servant of Onmyōdō

Shin’ichi Shigeta, Onmyōdō and the Aristocratic Culture of Everyday Life in Heian Japan

Idem, A Portrait of Abe no Seimei

Katja Triplett, Putting a Face on the Pathogen and Its Nemesis. Images of Tenkeisei and Gozutennō, Epidemic-Related Demons and Gods in Medieval Japan

Mitsuki Umeno, The Origins of the Izanagi-ryū Ritual Techniques: On the Basis of the Izanagi saimon

Katsuaki Yamashita, The Characteristics of On'yōdō and Related Texts

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

入宮

阿傑與阿成是雙胞胎兄弟,從小兩個人就幾乎長得一模一樣,常常讓人認不出來,但是在10歲那年,家裡的經濟頓時陷入困境,家中還有五位弟妹需要照顧,父親又因為身體太勞累,身體健康狀況越來越不好,走投無路的情況下,阿傑與阿成決定有一個人犧牲自己,入宮當太監,至少可以得到50兩的銀子,這筆錢至少可以讓家人過上大半年的時間,最後是身為弟弟的阿傑,即將到刀子匠劉爺那邊報到,在劉爺那邊,至少在手術這方面是相對良好的,很多要入宮的人都會選擇由他來操刀,在阿傑進去暗房之前,我都還不敢相信,阿傑要閹割成為太監這件事,直到暗房傳來了阿傑淒��的叫聲,看來阿傑已經被閹掉了,此時,劉爺身邊的助手走出暗房,告訴娘親手術很成功,要我們可以先回去了,待兩週後再來接阿傑回去,看著娘親擔心的一直回頭看,心想阿傑千萬要好好的,很快兩週的時間到了,我們到達劉爺的住處時,看到阿傑已站在門口等我們了,看似沒有改變的阿傑,實際上已經是一個太監,劉爺將50兩的銀子拿給娘親,另外告訴娘親,待阿傑13歲時,就可以準備入宮了,隨著時間過去,阿傑也順利的在13歲那年入宮當太監,家中的經濟狀況也有些許好轉。

轉眼間七年過去了,我也已經20歲了,在京城開了一家麵攤,生意也很不錯,也因為很多人慕名而來,讓我有機會可以認識到蘭兒,蘭兒是滿族人,她是家中的獨生女,今年才16歲,我跟蘭兒雖然身分懸殊,但是我們兩人卻一見鍾情,我們還偷偷許下承諾,一定要永遠在一起,但是父親卻說什麼都要讓女兒入宮為妃,一年一次的選妃也已經開始,蘭兒也因為長得天生麗質,很快就被嘉慶皇帝選為貴人,當我聽到了這個消息,內心的痛苦讓我感到窒息,但是抗旨就是死罪,我一個老百姓怎麼可能鬥得過皇權,我只能偷偷躲在城門附近,眼睜睜看著蘭兒走進宮門,我透過信件,與在宮中的阿傑聯繫,讓阿傑替我打探蘭兒的消息,透過信中提到,蘭兒因為初次服侍皇上,得罪了皇上,還被貴妃娘娘懲罰,聽到了這些說什麼都要進去看看蘭兒,但是宮牆森嚴,豈能隨意進出,眼下找不到任何機會的時候,聽到皇上打算出宮看戲,心想或許這是個好時機,結果當天我在戲院附近偷看,蘭兒並沒有跟著皇上出宮,阿傑卻有這個機會隨皇上微服出宮,我也總算見到了多年未見的阿傑,兩個人偷偷閒話家常的聊著,我突然有個大膽的念頭,我與阿傑交換身分進入宮中,況且我們長得一模一樣,不會有人發現的,阿傑為了可以在外面玩,也答應了這次的計畫,阿傑詳細的��明進宮的注意事項,我也擔心會穿幫所以很仔細的做紀錄,我跟阿傑交換了彼此的衣服,阿傑看到我脫下褲子的那一刻,內心有點酸的感覺,阿傑指著我的命根子,語重心腸的說,要我一定要保護好我的命根子,不然我們都會完蛋的,這些我當然知道,我跟阿傑就這樣成功交換了彼此身分,我懷著忐忑的心情,跟著隊伍一起慢慢走進了宮中,我協助皇上更衣之後,我根據阿傑的口述,順利走回自己的寢室,不過考驗才正要開始,一群人住在同一個地方誰也不認識,我一刻也無法鬆懈,頓時覺得自己為什麼要冒這個險進到宮裡,但是已經沒辦法後悔了,裡頭的小安子跟小春子是阿傑的好朋友,這些事情阿傑都有告訴我,所以我必須小心謹慎,避免跟他們說話的時候說溜了嘴,很快的小安子跟小春子也陸續回到房間,兩個人一見到我,熱情的跑來跟我搭肩,跟我討要出宮的禮物,但是我當時根本沒有時間去購買伴手禮,只能跟他們說抱歉,兩個人掃興的眼神,讓我覺得很尷尬,深怕被他們發現自己根本不是阿傑,所幸他們並未發現我跟阿傑的不同,兩個人這時邀我一起去洗澡,準備要睡覺了,但是我怎麼可能會跟他們一起去洗澡,他們替我拿了一套乾淨的衣服,拉著我一起去洗澡,我拼命的推辭也無法擺脫這種困境,我們一同走到了澡堂,看著小安子他們兩開始脫掉衣物,印入眼簾的是兩個沒了命根子跟子孫袋的兩副軀體,雖然我小時候看過阿傑的,但是還是沒有想像過宮中除了皇上還有我以外,其他都是閹人這件事情,我拿著我的衣物發著呆,他們兩個人叫了我,還在發什麼呆啊,還不趕快來洗澡,我假裝自己現在肚子很痛,趕快跑了出去,暫時鬆了一口氣,一出來我又很不幸撞見吳總管,吳總管是所有後宮太監宮女的頭,所有人都要聽從他的安排,吳總管一看到我就問了,阿傑你慌慌張張的幹什麼呢,我立刻跟吳總管請安,隨意說了一個藉口,擔心自己會不會被吳總管發現自己的身分,好險吳總管沒有多問,只要我走路小心點,驚擾了主子小心命沒了,我低著頭一直點頭道歉,匆匆繞過吳總管離開這邊,吳總管此時轉頭看著我,臉上的表情似乎有點困惑,我心裡在想,才第一天而已,就差一點被發現了,我還要撐到下一次出宮門才能換回來,內心感到很不安。

時間就這樣過了兩週,每天可以說是戰戰兢兢,直到今天,我終於遇到了身在宮中的蘭兒,蘭兒見到我的時候,我小心謹慎的接近蘭兒,蘭兒先是支開了身邊的宮女,一走過來也只問我,阿傑你出宮後有遇到阿成嗎,我看著蘭兒的臉,小聲的告訴蘭兒,要蘭兒晚上到花園的石牆碰面,阿成有些話必須私下告訴你,於是我們約好在今晚子時在石牆碰面,我們晚間也順利碰面,蘭兒一開口就問,阿成到底要你跟我說什麼,為什麼必須在這時間點,我開心的告訴蘭兒,蘭兒我就是阿成,我跟阿傑偷偷交換了身分,我就想進來看看你過的好不好,蘭兒這時震驚的說,你這是瘋了嗎,你難道就不怕死嗎,被抓到是會被誅九族的,我也只告訴蘭兒,我只會在裡面一個月,而且我也已經安全度過了兩週的時間,後續我會更加小心的,你別擔心我,你告訴我你在宮中過的好不好,蘭兒靠在我的懷裡,哭泣的訴說自己的痛苦,希望我可以永遠留在她的身邊,但是這是不可能的,蘭兒根本一點也不愛皇上,而且皇上的命根子根本疲弱無力,我安慰著蘭兒,就在這一刻,我與蘭兒吻了起來,我撫摸著蘭兒的胸部,她的胸部是如此柔軟,蘭兒退下我的褲子,看到我又粗又大的陰莖,立馬眼睛發亮,立刻吸允了起來,我的陰莖蘭兒要用兩隻手才能完全握住,我讓蘭兒躺在草皮上,我摸索著蘭兒的穴,看著已經濕掉的小穴,我粗大的陽具再也忍受不了,我的陰莖正努力撐開蘭兒的小穴,也因為太粗大了,我才放進龜頭而已,蘭兒就疼到發出了聲音,我立刻摀住她的嘴巴,深怕被別人發現,隨著陰莖慢慢插入,蘭兒的穴有點流血,原來是上次蘭兒與皇上侍寢時,皇上根本沒有用破蘭兒的處女膜,此時我的陰莖更加猛烈的撞擊蘭兒的穴,隨著速度與激情越來越強烈,我溫熱的精液射入了蘭兒體內,也因為我已經很久沒有射精了,射得非常的多,我們兩人在這一夜裡就做了三次,每一次都射了很多在蘭兒體內,如果蘭兒因此懷孕了,這樣我們就不得不替蘭兒打算,於是我開始計劃,要讓蘭兒受到皇上的寵愛,於是我要蘭兒回去把自己打扮的美美的,其他由他去想想還能怎樣幫助蘭兒,過沒幾天機會就來了,打扮的漂漂亮亮的蘭兒在御花園碰見了皇上,皇上看見了蘭兒,頓時覺得她換了一個人,重新與蘭兒交談,蘭兒利用我在社會上與人打交道的經驗,成功的討好了皇上的歡心,晚上皇上就翻了蘭兒的綠頭牌,蘭兒終於順利侍寢,隔日,皇上破天荒的晉了蘭兒的位份,封為楊嬪,這幾日,我與蘭兒又偷偷的做了兩次,就在隔了一週後,沒想到蘭兒真的懷孕了,雖然太醫一度有點懷疑為什麼蘭兒能這麼快就懷上孩子,但是因為皇上與太后對蘭兒懷上孩子都非常開心,於是也就沒有多想,但是我很清楚蘭兒肚子裡的孩子是我的,因為侍寢當晚,蘭兒說皇上根本就沒有射到體內,反而還沒放進去就射了,但是至少我們矇混過關了,只要蘭兒與我的孩子未來能過的幸福,這樣我未來在宮外也可以放心了,眼看事情都往好的方向發展,我離開宮中也可以放心了,一想到我明日就要出宮了,我與蘭兒確定要分離了,內心真的很不捨,代表我再也見不到蘭兒跟我未出生的孩子,但是這是唯一的辦法,隔天我一換好輕裝就立刻拿著令牌出宮,很快來到了與阿傑約定的地方,怎知道阿傑都沒有出現,我越來越心慌,不知道阿傑究竟在哪,一直等到最後一刻,阿傑依然沒有出現,眼看皇宮就要下鑰了,再不換回來就來不及了,但時間都要到了依然等不到阿傑,我只好硬著頭皮又返回宮中,我整個不知所措的像熱鍋上的螞蟻,但是最讓人擔心的是,宮中每三個月都會要求所有太監都要重新驗身,如今三個月又快到了,小安子告訴我說,日子訂在下週五,他還跟小春子說,到時候我們三個人一起去,我整個一臉茫然的看著他們,此時,吳總管走了進來,要我到他房裡一趟,我心想平時的吳總管也不曾找過我,到底有什麼事情呢,吳總管要我把門關上,他確認周遭沒有人之後,吳總管開門見山的問,你究竟是誰,我瞬間冒汗,我裝瘋賣傻的回答吳總管,我說我是阿傑啊,還能是誰,吳總管說,你別再演戲了,昨天我到外面處理一樁命案,發現者一看到屍體是個太監,就透過關係與我聯繫了,我看到了一個長得跟你一模一樣的人,如果我猜的沒錯,你就是阿傑口中的雙胞胎哥哥吧,你為什麼會出現在這裡,你到底有什麼企圖,我眼看事情敗露,我開始跪下磕頭道歉,求吳總管饒命,一邊哭一邊訴說自己為何跟阿傑交換身分,聽完原因之後的吳總管怒斥到,你們簡直就是不要命了,這可是會被誅九族的大罪,你們這樣不僅牽連了家人,楊嬪、小安子、小春子,還有我都會被殺頭的,你們簡直就是瘋了,我求吳總管救救楊嬪,吳總管要我把頭抬起來,如今阿傑已死,而你假如想救她,只有兩條路可以走,第一條就是你繼續假扮阿傑,永遠活在這宮中,這世上再也沒有阿成這個人,第二條就是下週被檢查出來你不是阿傑,所有相關人等都難逃一死,我跟吳總管問說,只要繼續當阿傑就可以了嗎,吳總管看著我說,為了所有人的命,你當然只能繼續當阿傑,但是你必須割掉你不應該有的東西,我倒抽了一口氣,我拒絕了吳總管的建議,吳總管怒斥到,這事是我惹出來的,要我擔起所有的責任,犧牲我一個人就能救所有人,眼看木已成舟,我告訴吳總管,一切聽從吳總管安排,吳總管說給他一天的時間準備,明天再幫我執行閹割,他要我回去的時候,絕對不能說出這件事,必須裝作自己是阿傑,必須做到神不知鬼不覺,小安子跟小春子看我從吳總管那邊回來,問我究竟發生了什麼事,我不能告訴他們真相,於是我只能騙他們說,我今天出去忘記買吳總管需要的東西,他很是生氣的懲罰我,小安子他們很擔心的檢查了我的身體,看我哪裡受傷了,我只跟他們說我沒事的,要他們早點去休息,他們說,要我跟他們一起去洗澡,他們說我已經推辭他們太多次了,這次說什麼都要跟我一起洗,我正當自己無法逃過一劫的時候,蘭兒此時派了一個小太監來找我,要我過去找她一趟,我立刻跟著小太監一起前往楊嬪的寢宮,一進入楊嬪寢宮後,蘭兒要其他人都退下,她以為阿傑已經成功跟我交換回來了,於是問我,阿成有沒有順利回到家,我難過的告訴了蘭兒所有事情的經過,蘭兒難過的哭了起來,因為她知道我明天就要被閹割了,現在反倒是蘭兒比我還要難過,我還安慰了蘭兒說,至少我們可以永遠在一起了,蘭兒還是一直在哭,我告訴蘭兒,你不要再哭了,沒事的,我只是少了一塊肉而已,蘭兒說這是多麼大的恥辱啊,你為了我竟然犧牲到這個地步,我跟蘭兒說,只要你跟肚子裡的孩子可以平平安安的,這絕對不是犧牲,我已經很滿足了,我擦掉蘭兒的眼淚,要她不要擔心我,她親了我,並且雙手摸著我的命根子,我很快又硬了起來,蘭兒吸允著我的陰莖,撫摸著我的睪丸,想讓我感受最後一次的幸福,自從蘭兒懷孕後,我也已經有將近兩週沒有射了,早已硬的不像話,很快一股股濃精射了出來,累積兩星期的精液,蘭兒一點也沒有浪費的全吞了進去,看著蘭兒滿足的表情,我也體驗過最後一次的射精,我已經沒有什麼遺憾的了,蘭兒允諾我,她要皇上把我安排到她的身邊當差,我開心的抱著蘭兒,心想只要可以永遠跟蘭兒跟我的孩子在一起,我什麼都可以接受,此時我不能久留在蘭兒的寢宮,於是依依不捨的離開了,回到我的寢室後,我坐在床邊思索,心想未來如何幫助蘭兒上位。

隔天一早,吳總管告訴我說要我晚上子時到敬事房,早上我依舊扮演好自己的角色,夜裡我懷著緊張不安的心情,來到了男人的地獄,敬事房,吳總管要我進來後,他昨日已安排好所有人,今天晚上不會有任何人進來這裡,我脫了身上的太監服,吳總管要我躺上台子,我整個人呈現了一個大字,吳總管將我的雙手雙腳緊緊的固定住怕我掙扎,腹部也被纏的緊緊的,此時我的命根子全部赤裸裸的展現在吳總管面前,一旁的止血散、麥稈、麻水、熟雞蛋、辣椒水都早已準備好,吳總管看著我的陽具,感嘆的說到,做什麼事不好,偏要進宮挑戰威威皇權,吳總管撫摸了我的陽具,我因為太緊張又硬了起來,吳總管握著我粗大的陰莖說到,看到你這陽具要被割掉,我也是覺得挺可惜的,可惜阿可惜,不過你也別怨,宮規就是如此,吳總管摸著我的蛋蛋,他說他其實沒有看過成年男性的命根子,所以有點好奇,畢竟入宮的人基本上都在小時候就閹掉了,所以這還是他第一次看到,很快吳總管拿了一碗麻水給我喝下,我被餵下麻水之後,隨著藥效開始慢慢發作,我感覺我的腦袋有點混亂,吳總管從樑上拉下一條細麻繩,繩圈套住了我的龜頭,吳總管轉動一旁的齒輪,我的陰莖被拉的很高很緊,讓我覺得有點不舒服,隨即又拿了一條細繩將我的兩顆蛋蛋綁緊,眼看一切準備就緒,吳總管將熟雞蛋塞進我的嘴裡,並且告訴我說,忍耐一下馬上就好了,他拿起了一旁的弧形彎刀,用火烤了一下,他握著我的兩顆蛋蛋,緊接著一刀就將兩顆蛋蛋連同子孫袋一起割下,我痛到吶喊,但是我的嘴裡有著雞蛋,讓我無法發出聲音,吳總管將割下來的蛋蛋放到一旁的盤子裡,並敷上了止血散後,吳總管準備割下我的命根子,他告訴我說,沒有人能忍受割下命根子的痛,你就別想太多了,暈倒了也沒有關係,我會幫你處理好的,我開始割了喔,吳總管就一瞬間的功夫,刀子就沿著我命根子的根部割了下去,我瞬間痛的冷汗直冒,叫聲早已無法抵消切斷陰莖帶來的巨痛,暈過去之前,我看到我被切斷的陰莖隨著繩子擺盪,我便痛暈了過去,我迷糊的隱約看到了吳總管正在處理我的寶貝,吳總管將我的命根子還有兩顆蛋蛋放進裝有半甕石灰的罐子中,以吸乾所有的水分,還用大紅布包好瓶口,我沒過多久就因為疼痛而醒來,但是因為太痛了我根本無法起身,看我下體剩一根麥稈插著,吳總管請了一個心腹小太監來照顧我,小太監說這要等三天後才能拔掉,確定尿道沒有因為傷口復原而堵住了,拔掉如果尿液能順利排出就算完成了,我知道你現在雖然很疼,但是你必須下床走動,不然之後會影響你走路的,我感覺我的傷口很腫脹,疼痛的難以走路,但是為了蘭兒,為了我的孩子,我一定要忍耐,隨著小太監的照顧下,我在第三天拔除麥稈之後,因為還沒有學會如何控制排尿,尿液噴的到處都是,此次閹割非常的順利,在透過吳總管跟小太監的細心照顧下,一週後我順利的離開了敬事房,如今我已經是一個太監,雖然我不用再擔心被別人發現自己是男人,但是少了它還是會覺得很難受,回到寢室後,小安子問我這一週到底是被安排去做什麼事呢,怎麼都沒有回來這裡,我謊稱吳總管要我去宮外替他辦點事,於是就這樣花了一週的時間,此時小春子也回來了,他感到很高興的跑來找我聊天,說我終於回來了,不過這不重要,重要的是我們趕快去洗澡,不然就快沒熱水了,這次我不再拒絕,跟著他們去到了澡堂,三個人脫光了衣服,露出了三個沒了命根子的肉體,小安子跟小春子說,好久沒有看到你跟我們一起洗澡了,你要替我們刷背才行,我也沒有拒絕,幫他們刷了背之後,他們也搶著替我刷背,於是我先讓小安子替我刷背,此時我心想,明天一定要去見蘭兒,至少讓她知道我平安回來了,回到了寢室後,吳總管來了,他跟我說我的寶貝目前放在他的寢室,問我打算什麼時候拿回去,我告訴了吳總管,我明日就去拿,感謝吳總管的大力幫助,以後不論吳總管要我做什麼,我都會誓死完成任務的,他回我說,這你就不必了,我只是想保住自己的性命罷了。

隔日,我跟蘭兒見面的時候,我們抱在一起,蘭兒問我傷口還疼嗎,我告訴她雖然傷口還沒有完全好,但是在復原過程中,我一直都想著你跟孩子,這是我唯一支撐下去的動力,蘭兒摸了一下我的褲襠,把我的褲子脫下,原本有著兩顆蛋蛋跟一根大陽具的地方,真的連一丁點都沒有了,蘭兒看著雖然難過但是心想至少還有彼此的陪伴,很快我也因為蘭兒向皇上請願,我順利的來到蘭兒的宮裡當職,每當夜裡我就會偷偷來到蘭兒的床上,陪著蘭兒一同入睡,天亮前就偷偷離開,很快就等到了蘭兒的生產期,我在寢殿外很是著急,聽著蘭兒撕心裂肺的叫聲,恨不得自己可以代替她,不久之後,孩子的哭聲傳遍了整個皇宮,我很開心的看著殿內,希望可以看看自己的孩子,很快產婆將孩子抱到偏殿,將蘭兒生了一位公子的好消息告訴皇上,皇上高興壞了,大大的賞了在場所有人,並將孩子賜名綿愉,而蘭兒也晉封為賢妃,看到蘭兒替我生了一個兒子,我真的很感動,至少我們家有後了,看著孩子越來越大,跟我和蘭兒是越來越像,我心裡高興壞了,雖然不能相認,但是這樣看著孩子跟蘭兒能過著錦衣玉食的生活,那也足夠了,綿愉在小時候也會叫我爹爹,我真的覺得我很幸福,而因為有蘭兒的幫助,我的其他兄弟姊妹也可以好好的生活下去,品質也得到很大的提升,蘭兒在綿愉五歲後,正式成為賢貴妃,而我的地位也得到了許多提升,在京城外還有一間自己的宅子,我也將自己的寶貝存放在外面的宅子,我在前年也將阿傑的寶貝給贖了回來,我把阿傑的寶貝放進自己的甕裡,畢竟我現在也叫阿傑,如果有兩個寶貝罐也顯得奇怪,閹割到現在也已經過了五年多,我也早已習慣沒有命根子的樣子,但是我不後悔,現在的我已經很幸福了,雖然我沒有了命根子,但是我也換來了跟蘭兒和孩子在一起的生活,我還要看著綿愉娶妻生子,我這一生也沒有遺憾了。

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

2年前の日記

一軒目のスーパーで肉や牛乳を買い、二軒目のコンビニでキャベツを買う。通勤鞄に入りきらないのでラグビーボールみたいに手で抱えて帰路につく。昭和の盗人みたいに。

さくらに手紙の返事を送ってから一か月近く経つ。その返事、「ついたよ」という連絡が一向にない。

理由はなんとなくわかっているからこそ「届いた?」という確認のラインを送れずにいた。新幹線の中で一気に書き上げ、ほとんど推敲せずに会社で印刷して送った。多くなるとわかっていたのでwordで打ったものの、印刷すると5枚で、印字で送るには厚みおよび手紙としての気迫が足りない、と思い最初のページにちょっとしたイラストを落書きして「手書きじゃなくてごめんよ」と吹きだしを足しておいた。エアメールなのに名前だけ癖で日本語で書いてしまい、あわててSakuraと郵便局でローマ字を振った。

さくらは不思議な友人だと思う。

サークルの同期だった。それなので付き合い自体はかなり長いのだけれど、本当に素で彼女と話せるようになったのは結局のところ社会人になってからだった。

1年の新歓時期だかに部室で会ったのが最初の出会いだった。初手から、綺麗な子だなと思っていた。その頃のわたしにとって、その感想はイコール「仲良くなってもらえないかもしれない」という危惧とあきらめに直結していた。

かつ、さくらは明るくて元気でなつっこい性格で、当時そんな言葉はなかったが言うなればどう見ても「陽キャ」で、日なたの国道を歩いてきた子のように見えた。事実はどうかわからない、けれど、容姿のきれいさ、人にしゃべりかける屈託のなさ、応じている人の嬉しそうな笑み、そのどれも自分が持ちえないものだった。こういう人はわたしとは仲良くしたいと思わないだろう、と決めつけて遠巻きにしていたものの、さくらからしゃべりかけてきて、そこにはなんのへだてもなかった。あ、こういう子なんだ、と思った。性格に裏表がない天真爛漫な美人。わたしの中にある、「顔が綺麗な人はこういうもの」という偏見の型のどれにもあてはまらなかった。

仲良くなれるはずがない、と思った。性格が悪ければ品のない話で盛り上がったり誰かの陰口に花を咲かせるなり、という邪道な方法で近しくなることもできるのだけれど、さくらは本当に、目に見えるままの子だった。完敗だった。「さくらちゃんって冗談通じないタイプだよねー」と性格の悪いイケメンの先輩がいつだったか彼女がいない場で漏らしていて、それを聞きながらこっそり溜飲を下げている自分がとてもくだらなく、浅ましい存在だと思った。

1年の終わりに部長を決めなければならなかったので、誰もいないだろと思って立候補してみたらさくらも手を挙げたので正直びびった。お互いに打ち明けていなかったので、その時点ではまだ表面的な「仲良し」だったんだと思う。投票で決めることになり、なんとなくわかっていたが、さくらが部長になり、わたしは副部長になった。

票がどんなふうに割れたのかは結局知らないのだけれど、さくらが選ばれた、という事実は、当時のわたしをそれなりに傷つけた。わたしの方が部室に顔を出していたし、展覧会で作品もまめに出していて、部員として「まじめ」だった。本当に部長を務めたかったのかと言えば、いまに思えばそうでもなかった気はする。ありていにいえばそもそもなんで立候補したのかもいまひとつその時の自分の気持ちを思いだせない。でも、負けた、と思ったし、わたしではなくてさくらの方がこの場では上だとみんなに思われてるんだなあ、と思った。もちろん、単に人気投票ということではなく性格や適性や総合的なことを鑑みて選挙がおこなわれたにすぎないのだけれど、当時のわたしは結果をみんなで分かち合っている、という状況がいたたまれなくてしょうがなく、羞恥の意識が身体を貫いた。立候補なんてしなければよかった、と思った。

思いだせないなりにいま振り返ると、わたしは部長になりたかったのではなくて(むしろめんどくさそうだなと思っていたのだし)、「そうだよね、このメンツだったら**ちゃんがふさわしいと思う」とみんなにうなずいてほしかっただけなのかもしれない。けど、結果はそうじゃなった。

別にその一件を通してさくらと関係がぎこちなくなったとかわたしがよそよそしい態度をとったとか、そういうことは特になく、そのあとも適度に仲は良かった。逆に言えば、一定の友だちではあったけれど、深い仲になることもなかった。さくらがどう思っていたかはわからないけれど、わたしは結構確信的に、この子とはここまでだ、と思っていた。決定的なことがなくてもしにたいと思ってしまうことや、サークルの中でかっこいいなと思っている異性のことや、サークル内で聞きかじった下世話な噂話をさくらと盛り上がれる想像が全くつかなかった。

憶えていることがある。新入部員の頃、先輩に「さくらちゃん彼氏いたことあるでしょ! むしろいまいる?」と聞かれて「ないですよ」とこたえ、「うそー! 絶対もてるでしょー!」と騒がれ、さくらは素で困ったようにはにかんで、話題が変わるのをしずかに待っていた。そのやりとりを見ながら、ああ、ほんとにこの人は自覚がないんだ、と思った。自分がひかっていて、それはどうにだって武器にできるものなのに、居心地悪そうな顔をして。

嫌い、と思えた方が楽だったと思う。ただひっそりと、ちゃんとしゃべったことないけどたぶんこういう子はわたしの苦手なタイプだろうな、と思った。そしてその思い込みは、結局大学を卒業するまで、石のように残りつづけたまま、それでもサークルはおなじであるからして、「友だち」でいた。

東京に出たわたしは、23区ではなく国分寺に配属された。仙台よりいなかじゃんか、と思いながら、どうにか慣れない日々や人や街に慣れようと必死だった。そんな時、さくらが「東京行くから泊めて」と連絡を寄越してきた。遠いけど来なよ、と言うと「ありがとう!」と返ってきた。さくらは大学在学中アメリカに留学していたので、ストレートに学部を卒業したわけではない。そもそもいまひとつ、いまどういう状況なのかも知らないでいた。

夜遅く、さくらがマンションに来た。遠かったでしょ、と言うと、遠かった、と笑っていた。着いたのは22時過ぎとかだったので、お風呂を貸して、すぐ布団を並べて寝ることにした。

「**はどういう会社に入って、何の仕事をしてるの?」

川の水を掬ったような澄んだ声で問われ、一瞬言葉に詰まった。在学中に作家になれず、挫折をひきずったまま出版社に潜り込もうとしたものの内定は出ず、そうなるともう自分が何をしたいかなどまったくわからなかった。手当たり次第に企業を受けたものの、結局、自分がなるとはまったく想定していなかった職につき、当然、業務内容に全く関心をもてないまま社会人生活は始まってしまった。

ごまかしようもないので職種と日々の仕事内容をありのままに説明すると、「そうなんだ、意外だね」と言われた。本人が一番そう思っているのでへらへらするしかなかった。

「**はやりたいことがあって、仕事もちゃんとやって両方がんばってて、すごいね。わたしは自分が何をやりたいのか、まだよくわからないから」

「さくらっていまどうしてるの? まだ大学にいるの?」

いまさらのように尋ねると、アメリカの大学でアニメーションの勉強をしているのだと明かしてくれた。さくらは建築学科だったので、意外だった。「アニメーターを目指してるの?」と尋ねると、まだ決めていない、としずかに返ってきた。

「**みたいに、小説が心から好きで、一所懸命書いてるのうらやましい。わたしは、まだ自分がどうしたいのか定まってないから。向こうでいろいろ美術のこと勉強中」向こうでは、デッサンの基礎を学んだりアニメーションを実際につくったりしているらしかった。美術部は完全に趣味で在籍していたわたしからすれば、せっかく名前のある大学に入ったのに随分思い切った進路だなあ、とひそかに思ったけれど、小説を書かない人間からしたらわたしがしていることだって相当突飛だろう、と思い直した。

「**みたいに、これだ、って思える芯があるわけじゃないから羨ましいよ」

わたしは黙り込んだ。

会社のトイレで泣き、月曜日から木曜日まで毎日「早く金曜日にならないかなあ」と思いを馳せながら働き、日に日に時計を確認する頻度が上がる、東京の郊外での些末な暮らし。仙台にいる恋人からは4月に「別れよう」と言われてから別れ話がこじれにこじれ、肝心の小説は、失恋や引っ越しで精神がめちゃくちゃにになったことを盾に事実上筆を折っていた。新人賞用の原稿はせっかく書き上げていたのに推敲が面倒くさくなり、というか急に点数をつけられるということが怖くなって土俵に送り込まずにボツにして、新しい小説は書こうとしては途中で投げていた。こんなの全然「羨ましい」なんかじゃないよ、と思ったけれど、いまの自分のていたらくを一つひとつ明かす勇気も気力もなかった。そして、こんなめちゃくちゃな生活でも、羨ましい、と思えるような面がまだ残っているのであれば、その虚像をまだ信じていたかった。さくらが、誰かを、それも自分を「羨ましい」と思うことがあるなんて、想像もしていなかった���

四年も付き合いがある中で、初めて、いろんな話をした。ほかの、さくらよりもっと親しいと思っていた部員にも言ったことのない本音や、愚痴や、夢や、感情のことを話した。次の日は「**がこの町で好きなところに連れて行ってよ」と言うので、妹尾図書館まで歩いて行って、お昼を食べて、さくらを駅まで送った。

その一件から、わたしのさくらへの気持ちや関係性の捉え方が変わった。時々ラインを交わし、時差のすきまで電話をした。

そして、社会人1年目の年末、さくらから再び連絡があった。日本に帰ってきてるから晩御飯食べよ、と誘われ、自分の職場である新大久保のトッポギを食べることにした。学生時代からうすうす気づいてはいたが、さくらは辛い物、というかげてものが好きなタイプの女の子だった。言いはしなかったけれど、可愛いのにへんなやつ、と失礼な感想を持っていた。

「そういえばさ、さくらは死にたいとか思ったことなさそう、って昔**に言われたな」

さくらが選んだ店は、大久保でも有名な激辛の店だった。熱くて辛い、痛みの根源のような食べものと格闘しているさなか、急にさくらが言いだした。ぎょっとして「そんなこと言った?」ととっさに言い返した。さくらは邪気のない笑顔で言ったよ、とうなずいた。

「なんてこというんだ! って思ったもん。覚えてないの?」

全く、覚えていなかった。頭があせりで真っ白になった。

大学生の頃だったら、さくらのように明るく、人に囲まれたきれいな子はしにたいとか思うはずがない、と思い込んでいたかもしれない。いや、かもしれないとかじゃなくて、そう思っていた。

覚えがない。でも言ったのかもしれない。あの頃の自分ならありうる。内心汗をかいていると、さくらはあっさりと別の話題を話し始めた。正直に言えば、言った言わないの問答にならなかったことに心から安堵した。さくらがそういうなら言ったんだろう、と思った。

新しい仕事や近況の話をして、残ったトッポギは包んでわたしが持って帰ることにした。新宿駅に向かって歩きだし、線が違ったので地下へ降りる階段の前で別れた。

よいお年を、と口にしたら「おない年の人と言い交わすのって変な感じ」とさくらが笑った。それを見て、どうしようもなく、さみしい気持ちになった。

あ、いまわたしこの人に抱きつきたいかも、と思った。同性の友達に対してそんなふうに思ったのは初めてだったし、友達とハグをした経験も数えるほどしかなかった。正確に言えば、こういう場面でそういう、突発的なハグをしたことがなかった。びっくりされそうな気がして、言わないでおいた。

だって、さくらとはそういうんじゃないし。この期に及んで、そう思う自分が、確かにいた。遠慮、後ずさり、虚勢。結局、また明日学校で会うみたいな顔をして、手を振って別れた。

それからもなんどか電話した。突然ラインをくれるのはいつも彼女だった。あれからいちどもわたしの失言についての言及はなく、読んだマンガやいま書いている作品について、あるいははまっているアイドルについてとりとめもなく雑談した。塩釜で全裸になったときの原稿を送ったらすぐ電話をくれて、会社の非常階段で15分くらい話した。性的な話を全くかわしたことがなかったので、道徳的な観点で批判されたり軽蔑されたらちょっとやだな、と思っていたけれど、そんな無粋なことは全くさくらは口にせず、ただただ面白がっていた。

この人はわたしが思うような人ではなかったのかもしれない。友だちになってから随分時間が経つというのに、いまさらのようにそう思った。そして、離れてからしか気づけなかった自分が、あまりにもおろかだと思った。自分の保身ばかり目を向けていて、さくらを「顔のきれいな人」としか見ていなかったのだ、といまになって思った。

さくらから突然ポストカードが届いたのは8月の終わりのことだった。玄関で、靴も脱がずにそれを読んで、わっと泣いた。とくべつな内容ではなく、日本の小説を読んで、わたしと話したくなって、筆を執った、そういう簡潔な内容だった。まぎれもなくわたしだけにあてられた手紙だった。

大学生の頃、わたしはさくらとはここで終わりだろう、と思っていた。もちろん一人の友だちに���して明確にそう思っていたのではなく、社会人になっても遊んだり、連絡を取ったりするだろうとは全く思っていなかった。それを、さびしいとも、正直に言えば思っていなかった。さくらとはここまで、と思っていたから。

でも、大学を出て4年経ったいまでも、わたしたちは友だちだ。それはさくら一人の力によって関係性がつづいているんじゃないだろうか。だって、わたしから連絡をするのは、書き上げた小説を送る時くらいだ。それは、よく言えば信用しているから読ませているとも言えるけれど、わたしは当事者だから自分の気持ちはわかっていた。

ものをつくっている人に送れば、内容に問わず書き上げたことに「すごいね」と言ってもらえるとわかっていたから、その賞讃ほしさに送っていただけなんじゃないだろうか。

でもさくらはそうじゃなくて、本当にただ純粋に友だちとしてわたしを好きで、信じている。はっきりそう書いてあったわけではないにしろ、そういうことが伝わる手紙だった。というよりも、アメリカからわざわざ手紙を送るという行動だけで、充分だった。封筒には、きらめくはなびらの切り紙も一緒に入っていた。ラブレターだ、と思った。

さまざまな感情が津波のように打ち寄せ、長い手紙を書こう、と思った。集中して書きたい、と思って移動中に書き上げた。それはさくらに対する感情の変化を綴った、独白のような懺悔のような、一方的な内容だった。書いている時は集中していたので気づいていなかったけれど、送って数日後に読み返して、うわ、と思った。顔が、赤ではなく蒼くなるのを感じた。さくらが寄越したものがラブレターだとしたら、これは単なる弁解だった。許してほしい、とうわめづかいが浮かび上がるような。

うーんと思っているうちに、ひさしぶりに東京で大きな地震があった。(これは、本当にだめなほうの地震かもしれない)と思った。部屋の真ん中で硬直しているうちに揺れはおさまった。

そういえば忘れてたな、地震ってくるもんだったな、とぼんやりしているうちに、いまだったら、送りそびれているいくつかのメッセージを送れそうだと思った。どれも年単位で滞っている連絡で、地震程度ではやはり、勇気が湧かずに素通りした中で、さくらには送れる、いま、と思った。

【手紙届いてる?】

次の日に連絡があった。【手紙で返信送ろうと思ってた!ごめんね】【来週一時帰国するから会おう!】だった。拍子抜けした。怒って連絡を寄越さない、ってわたしじゃあるまいしさくらにかぎってありえないか、と思ってちょっと笑った。

【13日なら空いてる うち泊まりなよ】

さくらからの手紙には、「**とべろべろになるまで飲んでいっぱい話したい」とあった。さくらが結構お酒に強いことを、ふっと小さい風が吹くようにして思いだす。さくらがうちに来るまでに、ヘパリーゼと一ノ蔵を買っておこうと思う。

2021.11

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

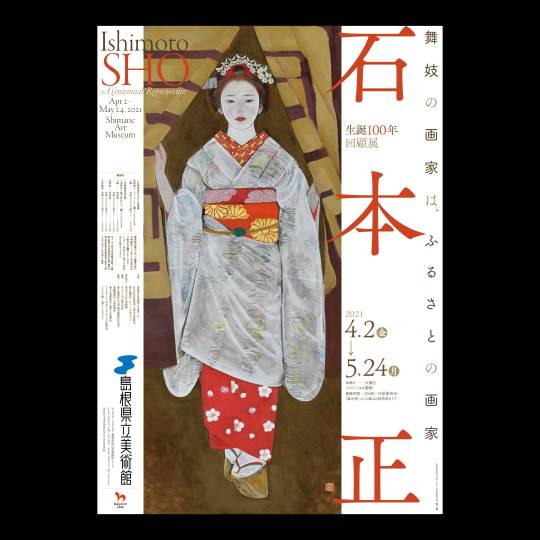

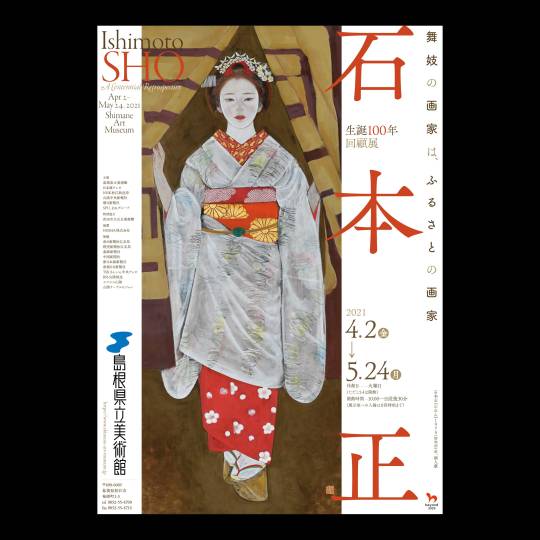

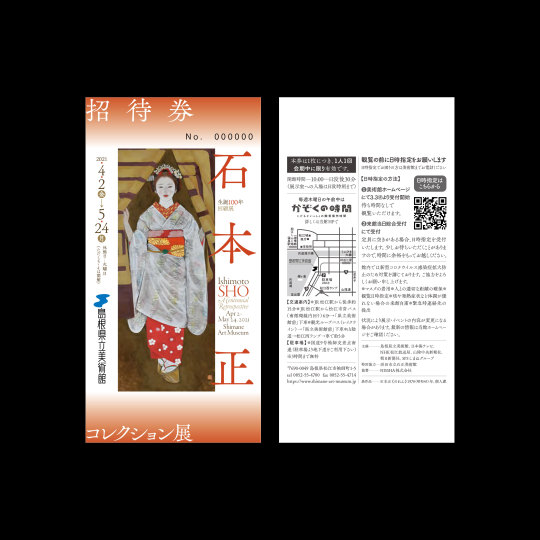

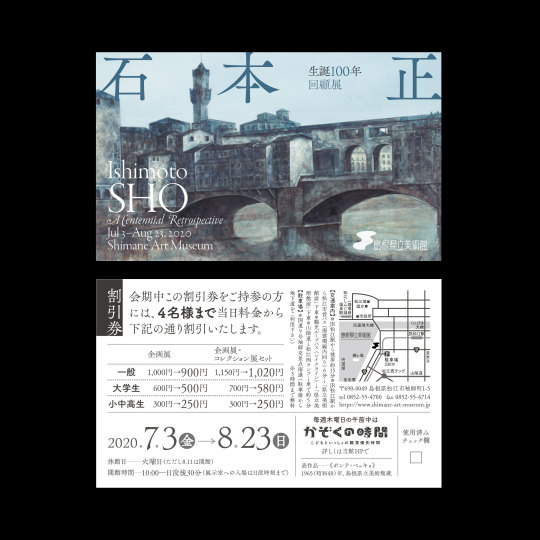

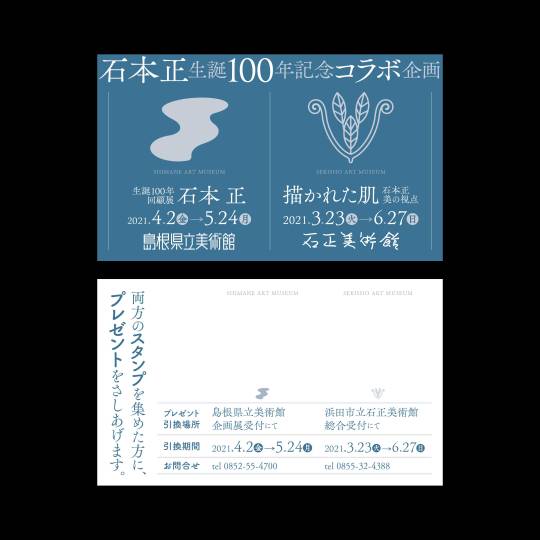

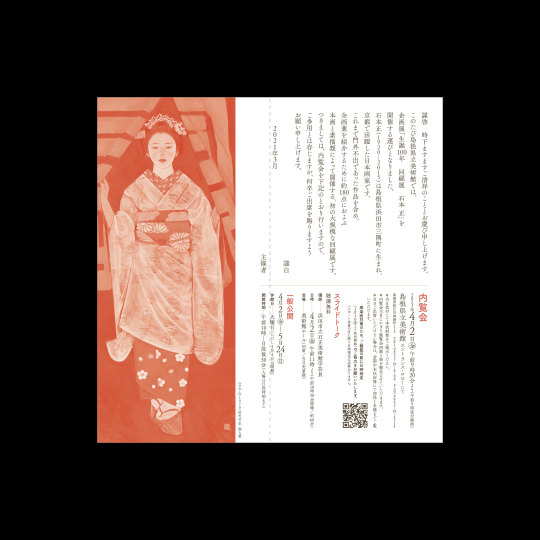

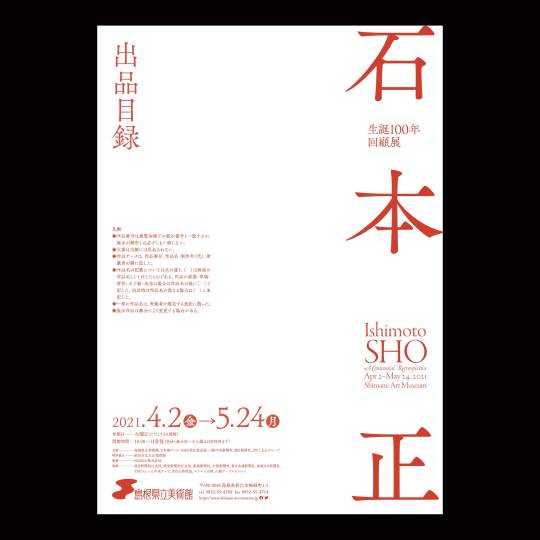

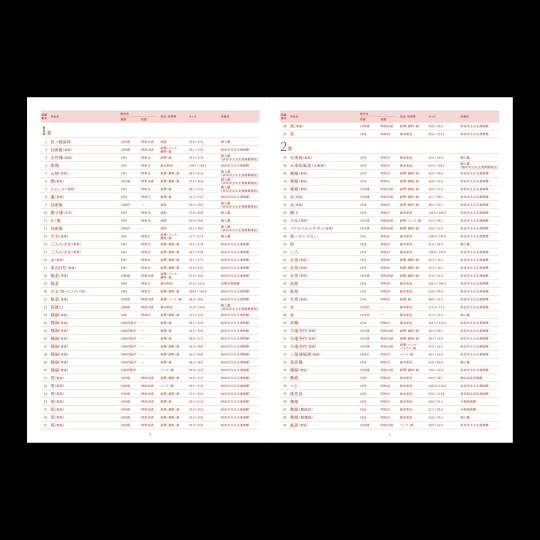

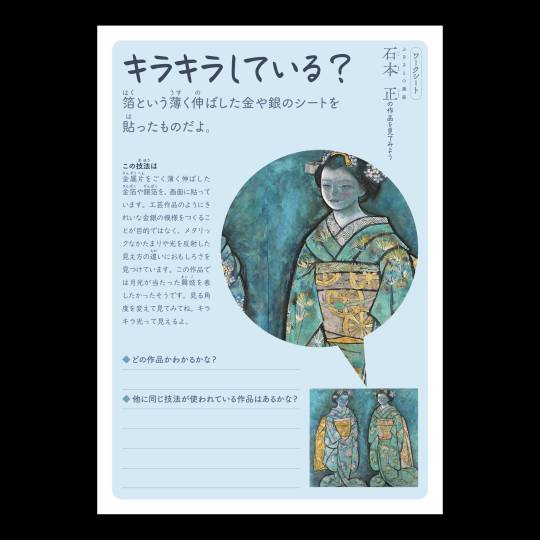

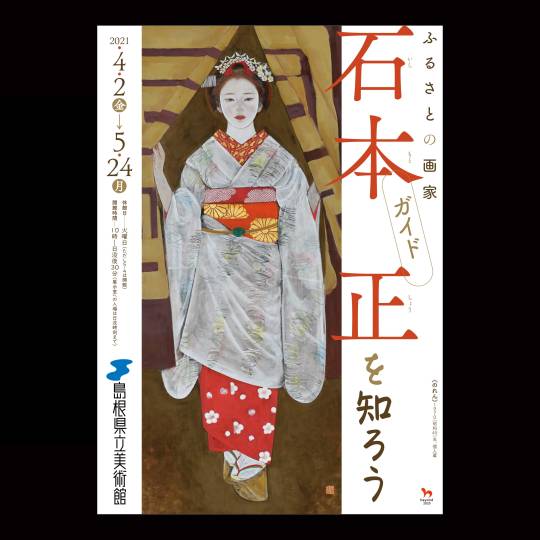

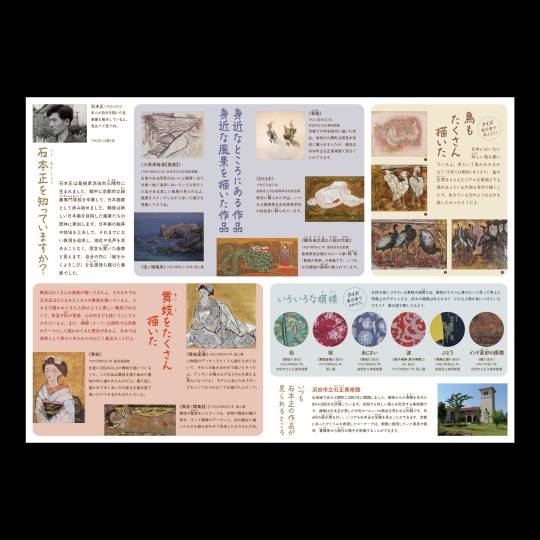

生誕100年 回顧展 石本 正 | Ishimoto Sho: A Centennial Retrospective

生誕100年 回顧展 石本 正

2021年

主催:島根県立美術館ほか

デザイン:石川陽春

印刷:渡部印刷株式会社

Ishimoto Sho: A Centennial Retrospective

2021

clients: Shimane Art Museum and others

design: ISHIKAWA Kiyoharu

printing: Watanabe Printing Co., Ltd.

#島根県立美術館#狸坊松江#狸坊出雲#狸坊山陰#石本正#展覧会#美術#日本画#舞妓#石川陽春#デザイン#松江#島根#shimaneartmuseum#ishimotosho#shoishimoto#artexhibition#fineart#nihonga#maiko#ishikawakiyoharu#design#matsue#shimane

0 notes

Text

嗚呼、なんという無様

生前の蘆屋道満こと蘆屋さんのイメージ。晴明にガチンコ平安陰陽師呪術バトルで敗北した的なそれ。(他に言い方は無いものか)

色々な感情がごちゃごちゃになってしまった蘆屋さん、大変推せますね。

ひらひら、というよりもジュッとなって真っ直ぐに落ちてきてる呪符たちがお気に入り。

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

「宮崎正弘の国際情勢解題」

令和六年(2024)2月5日(月曜日)

通巻第8118号

孫子を読まずして政治を語る勿れ。派閥解体、政治資金浄化????

吉田松陰の代表作は、じつは孫子の研究書(『孫子評註』)だった

*************************

自民党の派閥解消を聞いて、日本の政治家は政治の本質を理解していないことに唖然となった。派閥はまつりごとのダイナミズムを形成する。パワーの源泉である。それを自ら解体するのだから、政治は星雲状態となる。となると欣喜雀躍するのは中国である。国内政治にあっては、その「代理人」たちである。

孫子が言っているではないか。「謀を伐ち、交を伐つ」(=敵の戦略を見抜き、敵戦力を内訌させ、可能なら敵の一部を取り込め、それが戦争の上策である)。そうすれば、闘わずして勝てる、と。

高杉晋作も久坂玄瑞も、松下村塾で吉田松陰の孫子の講議を受けた。松陰亡き後の門下生だった乃木希典は、師の残した『孫子評註』の私家版を自費出版し、脚注もつけて明治天皇に内奏したほど、心酔していた。世にいう松陰の代表作はその辞世とともに有名な『講孟余話』と『留魂録』だが、現代人はすっぽりと『孫子評註』を忘れた。これは江戸時代の孫子研究の集大成である(『吉田松陰全集』第五巻に収録)。

松陰は山鹿素行を師と仰ぐ兵法家から出発している。毛利長州藩の軍事顧問だったのである。

もとより江戸の学問は官学が朱子学とは言え、新井白石も山鹿素行も荻生徂徠も山崎闇斎も、幕末の佐久間象山も西郷隆盛も孫子は読んだ。しかし江戸時代の二百数十年、太平の眠りにあったため、武士には、読んでもその合理的で非情な戦法に馴染めなかった。

その謀(はかりごと)優先という戦闘方式は、日本人の美意識とあまりに乖離が大きく、多くの日本人は楠正成の忠誠、赤穂浪士らの忠義に感動しても、孫子を座右の書とはしなかった。

明治以後、西洋の学問として地政学が日本に這入り込み、クラウゼウィッツは森鴎外が翻訳した。戦後をふくめてマキャベリ、マハンが愛読され、しかし誤読された。吉田松陰の兵法書はいつしか古書店からも消えた。

しかし戦前の指導者にとっては必読文献だった。

吉田松陰が基本テキストとしたのは魏の曹操が編纂した『魏武註孫子』で、考証学の大家といわれた清の孫星衍編集の平津館叢書版を用いた。そのうえで兵学の師、山鹿素行の『孫子諺義』を参考にしている。

もともと孫子は木簡、竹簡に書かれて、原文は散逸し、多くの逸文があるが、魏の曹操がまとめたものが現代までテキストとなってきた。

▼孫子だって倫理を説いているのだが。。。

孫子はモラルを軽視、無視した謀略の指南書かと言えば、そうではない。『天』と『道』を説き、『地』『将』『法』を説く。

孫子には道徳倫理と権謀術策との絶妙な力学関係で成り立っているのである。

戦争にあたり天候、とくに陰陽、寒暖差、時期が重要とするのが『天』である。『地』は遠交近攻の基本、地形の剣呑、道は平坦か崖道か、広いか狭いかという地理的条件の考察である。戦場の選択、相手の軍事拠点の位置、その地勢的な特徴などである。

『将』はいうまでもなく将軍の器量、資質、素養、リーダーシップである。『法』とは軍の編成と将官の職能、そして管理、管轄、運営のノウハウである。『道』はモラル、倫理のことだが、孫子は具体的に「道」を論じなかった。

日本の兵学者は、この「道」に重点を置いた。このポイントが孫子と日本の兵学書との顕著な相違点である。

「兵は詭道なり」と孫子は書いた。

従来の通説は卑怯でも構わないから奇襲、欺し、脅し、攪乱、陽動作戦などで敵を欺き、欺して闘う(不正な)行為だと強調されてきた。ところが、江戸の知性と言われた荻生徂徠は「敵の理解を超える奇抜さ、法則には則らない千変万化の戦い方だ」と解釈した。

吉田松陰は正しき道にこだわり、倫理を重んじたために最終的には武士として正しい遣り方をなすべきとしてはいるが、それでいて「敵に勝って強を増す」とうい孫子の遣り方を兵法の奥義と評価しているのである。

つまり「兵隊の食糧、敵の兵器を奪い、そのうえで敵戦力の兵士を用いれば敵の総合力を減殺させるばかりか、疲弊させ、味方は強さを増せる」。ゆえに最高の戦闘方法だとし、これなら持久戦にも耐えうる、とした。

江戸幕府を倒した戊辰戦争では、まさにそういう展開だった。

「孫子曰く。凡そ兵を用いるの法は、国を全うするを上と為し、国を破るは之れに次ぐ。軍を全うするを上と為し、軍を破るは之れに次ぐ。旅を全うすると上と為し、旅を破るは之れに次ぐ。卒を全うするを上と為し、卒を破るは之に次ぐ。伍を全うするを上と為し、伍を破るは之れに次ぐ」

つまり謀を以て敵を破るのが上策、軍自作戦での価値は中策、直接の軍事戦闘は下策だと言っている。

▼台湾統一を上策、中策、下策のシミュレーションで考えてみる

孫子の末裔たちの国を支配する中国共産党の台湾統一戦略を、上策、中策、下策で推測してみよう。

上策とは武力行使をしないで、台湾を降伏させることであり、なにしろTSMCをそのまま飲みこむのだと豪語しているのだから、威圧、心理的圧力を用いる。

議会は親中派の国民党が多数派となって議長は統一論を説く韓国瑜となった。

宣伝と情報戦で、その手段がSNSに溢れるフェイク情報、また台湾のメディアを駆使した情報操作である。この作戦で台湾には中国共産党の代理人がごろごろ、中国の情報工作員が掃いて捨てるほどうようよしている。軍の中にも中国のスパイが這入り込んで機密を北京へ流している。

軍事占領されるくらいなら降伏しようという政治家はいないが、話し合いによる「平和統一」がよいとする意見が台湾の世論で目立つ。危険な兆候だろう。平和的統一の次に何が起きたか? 南モンゴル、ウイグル、チベットの悲劇をみよ。

中策は武力的威嚇から局地的な武力行使である。

台湾政治を揺さぶり、気がつけば統一派が多いという状態を固定化し、軍を進めても抵抗が少なく、意外と容易に台湾をのみ込める作戦で、その示威行動が台湾海峡への軍艦覇権や海上封鎖の演習、領空の偵察活動などで台湾人の心理を麻痺させること。また台湾産農作物を輸入禁止したりする経済戦争も手段として駆使している。すでに金門では廈門と橋をかけるプロジェクトが本格化して居る。

下策が実際の戦争であり、この場合、アメリカのハイテク武器供与が拡大するるだろうし、国際世論は中国批判。つまりロシアの孤立化のような状況となり、また台湾軍は練度が高く、一方で人民解放軍は士気が低いから、中国は苦戦し、長期戦となる。

中国へのサプライチェーンは、台湾も同様だが、寸断され、また兵站が脆弱であり、じつは長期戦となると、中国軍に勝ち目はない。だからこそ習近平は強がりばかりを放言し、実際には何もしない。軍に進撃を命じたら、司令官が「クーデターのチャンス」とばかり牙をむくかも知れないという不安がある。

下策であること、多大な犠牲を懼れずに戦争に打って出ると孫子を学んだはずの指導者が決断するだろうか?

▼孫子がもっとも重要視したのはスパイの活用だった

『孫子』は以下に陣形、地勢、用兵、戦闘方法などをこまかく述べ、最終章が「用間(スパイ編)」である。敵を知らず己を知らざれば百戦すべて危うし」と孫子は言った。スパイには五種あるとして孫子は言う。

『故に間を用うるに五有り。因間有り。内間有り。反間有り。死間有り。生間有り。五間倶に起こりて、其の道を知ること莫し、是を神紀と謂う。人君の宝なり』

「因間」は敵の民間人を使う。「内間」は敵の官吏。「反間」は二重スパイ。「死間」は本物に見せかけた偽情報で敵を欺し、そのためには死をいとわない「生間」は敵地に潜伏し、その���民になりすまし「草」となって大事な情報をもたらす。

いまの日本の政財官界に中国のスパイがうようよ居る。直截に中国礼賛する手合いは減ったが、間接的に中国の利益に繋がる言動を展開する財界人、言論人、とくに大手メディアの『中国代理人』は逐一、名前をあげる必要もないだろう。

アメリカは孔子学院を閉鎖し『千人計画』に拘わってきたアメリカ人と中国の工作員を割り出した。さらに技術を盗む産業スパイの取り締まりを強化した。スパイ防止法がない「普通の国」でもない日本には何も為す術がない。

(十年前の拙著『悪の孫子学』<ビジネス社>です ↓)

9 notes

·

View notes