#1799

Text

hamilton decided to loosen up from public affairs and do that ghost prank with his nephew, only for new york to lose its shit and require a statement from him. if that were me i'd be like aw fuck see this is what i mean, i can't do shit without everyone getting on my back 😭

#new york man pulls ghost prank on close family and friends. you won't believe what happened next.#i like to believe that this was him going. “you know what. they're right. i'm too caught up in public affairs.”#“let's spend some quality family time!” only for it to become public so rapidly that john jay's son wrote a letter about it to his sister#alexander hamilton#philip church#1799#amrev#historical hamilton

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Court Suit

1790s

United Kingdom

Victoria & Albert

#fashion history#historical fashion#1790s#regency era#menswear#mensfashion#regency fashion#regency#floral#flower print#silk#linen#cotton#embroidery#british#united kingdom#18th century#1790#1795#1799#court suit#v and a#v and a museum#popular

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gallery of Fashion, vol. V: April 1, 1798 - March 1 1799

From the Met Museum

#gallery of fashion#fashion#fashion plate#print#dress#fashion history#1798#1799#1790s#1700s#18th century#georgian#history

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costume Parisien, 1 décembre 1799, An 8 (175): Chapeau - Capote. Schall de Casimir. Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands

'Chapeau-capote' with a long transparent veil with a floral pattern covering the face. A long 'casimir' scarf around the neck. Dress with long sleeves and train. Flat shoes with pointed toes. The print is part of the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published by The print is part of the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published by Pierre de la Mésangère, Paris, 1797-1839.

#Journal des Dames et des Modes#18th century#1790s#1799#on this day#December 1#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#color#description#rijksmuseum#dress#shawl#veil#lace#Mésangère#cashmere

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oil painting, 1799, British.

Portraying Charlotte Pechell, née Clavering, in a white dress and black shawl.

Painted by John Hoppner.

Met Museum.

#painting#1790s painting#1799#1790s#1790s dress#dress#shawl#John hoppner#met museum#charlotte pechell#white

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

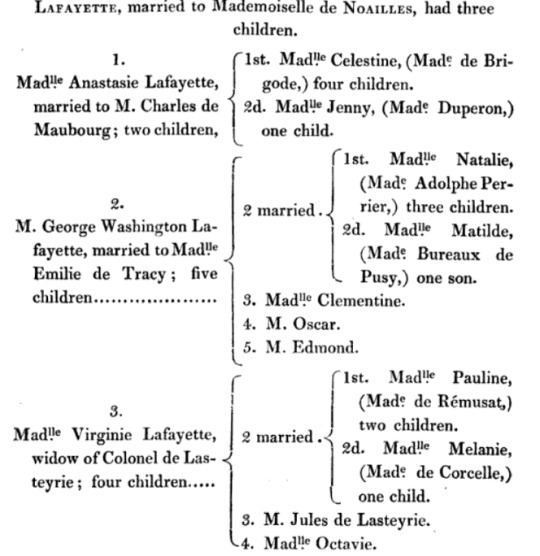

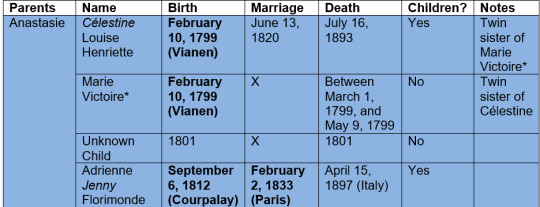

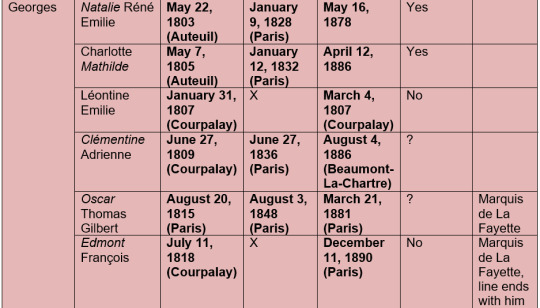

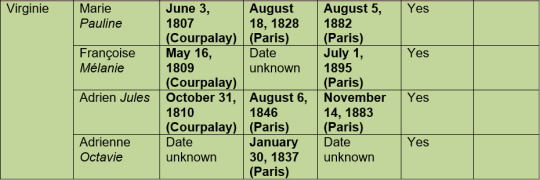

ALL of La Fayette’s Grandchildren

(This post discusses the death and loss of children)

While four children are still pretty easy to keep track of, La Fayette’s abundance of grandchildren can be quite confusing. You often see the following graphic, published in Jules Germain Cloquet’s book:

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 227.

All fine and dandy, but I was looking for more detailed information and I wanted to include the children that had already died by the time Cloquet publishes his book – I therefor made a graphic of my own. :-)

I am tempted to make one for the great-grandchildren as well, since La Fayette was very exited to become a Great-Grandfather – but this one was already a wild ride and La Fayette had more great-grandchildren then grand-children, let me tell you.

Anyway, some names are written in italics, these are the names the individuals commonly went by. I find it funny to see that all of Virginie’s children went by their second name, just like Virginie herself mostly just used her second name. Anastasie’s second child has an Asterix to her name. I have only once seen the name spelled out, on the certificate of baptism. The twins were baptized in Vianen (modern day Netherlands) and the name on the document was the Germanic spelling “Maria Victorina” – I used what I assumed is the best French spelling of the name.

The dates in bold indicate that the corresponding documentation of the birth/marriage/death can be found in the archives.

Anastasie and Charles: Finding Célestine’s dead twin sister was actually a surprise for me since I have never before seen her being mentioned. Anastasie gave birth for the first time in a town near Utrecht in what today are the Netherlands. The achieves there still have the certificate of baptism (on February 30, was the clerk sloppy or did the region in 1799 adhere to a different calendar style where February could have more then 29 days?) and we can very clearly see that there were too children. By May 9, 1799, La Fayette wrote to George Washington and referred to only one grand-child:

My wife, my daughters, and Son in law, join in presenting their affectionate respects to Mrs Washington & to you my dear g[ener]al the former is recovered & sets out for france on monday next with Virginia—our little grand Daughter [Célestine] is well, will your charming one accept our tender regard?

“To George Washington from Lafayette, 9 May 1799,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0041. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 4, 20 April 1799 – 13 December 1799, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999, pp. 54–59.] (02/12/2024)

I suspect that Anastasie had a stillbirth around August/September of 1801. La Fayette mentioned in a letter to Thomas Jefferson on June 21, 1801:

Anastasia Will Before long Make me Once More a Grand Father

“To Thomas Jefferson from Lafayette, 21 June 1801,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-34-02-0318. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 34, 1 May–31 July 1801, ed. Barbara B. Oberg. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007, pp. 403–404.] (02/12/2024)

There is no mention of this child being born and both the achieves in Paris and Courpalay yield no information so that it is unlikely that the child was born and then died young. Georges’ daughter died very young and she still is in the archives. Given La Fayette’s wording we can assume that Anastasie’s pregnancy was already somewhat advanced and the term miscarriage is only used up until the 20th week of a pregnancy, after that it is considered a stillbirth.

Georges and Emilie: The couple lost at least one daughter, Léontine Emilie, young, aged just four weeks. La Fayette wrote in a letter to Thomas Jefferson on February 20, 1807:

My family are pretty well and beg to be most affectionately respectfully and gratefully presented to you—We expected a Boy to be called after your name—But little Tommy has again proved to be a Girl [Léontine Emilie].

“To Thomas Jefferson from Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, 20 February 1807,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-5122. [This is an Early Access document from The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. It is not an authoritative final version.] (02/12/2024)

La Fayette later wrote to James Madison on June 10, 1807:

We Have Had the Misfortune to Loose a female Child of His, four Weeks old [Léontine Emilie]. My Younger daughter Virginia Has Lately presented us With an other infant of the Same Sex [Marie Pauline]. My Wife’s Health is Not Worse at this Moment, But Ever too Bad.

To James Madison from Marie-Adrienne-Françoise de Noailles, marquise de Lafayette, 10 June 1807,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/99-01-02-1768. [This is an Early Access document from The Papers of James Madison. It is not an authoritative final version.] (02/12/2024)

As a sidenote because it confused me while searching for the letter; the archives list Adrienne as the author. I am certain that is wrong because a) Adrienne was not corresponding with James Madison, b) this is not her writing style but La Fayette’s, c) the letter does not have her typical signature and d) there is the passage about the authors wife’s health – this one at the least gives it away.

Identifying Léontine Emilie was actually quite a bit of luck as well. I found the letter to Madison by accident and that letter is the only source that mentions her that I know of. I have never seen her in any other letters, documentation, contemporary or secondary books. The letter helped to narrow her birthday and her date of death down and with that information I searches the archives in Paris and Courpalay in the hopes of finding the child – and I was lucky. While I of course understand the order of things, it still saddens me to see that you can be born into such a prominent family – your father was a Marquis, your grand-father was the Marquis, and still, not even your families biographers care to even mention you.

Virginie und Louis: For all I know, and I again have to say that I have not nearly as much data/correspondence as I would like with regard to these topics, Virginie never lost a child. There is always the question what La Fayette would feel comfortable telling and to whom. There is also the question if La Fayette himself was always aware of everything. For example, in the case of a miscarriage very early on in the pregnancy he might have not included it in his correspondence or in fact maybe not even known himself.

As much as would wish a happy family life for Virginie, stillbirths, infant deaths and especially miscarriages were and still are not uncommon.

I have put excerpts from a few more letters by La Fayette to his American friends under the cut that help identify his grandchildren.

La Fayette to Thomas Jefferson, June 4, 1803:

I am Here, with my Wife, Son, daughter in law, and New Born little grand daughter [Natalie Renée Émilie] taking Care of my Wounds, and Stretching My Rusted Articulations untill I can Return to my Beloved Rural Abode at La Grange.

“To Thomas Jefferson from Lafayette, 4 June 1803,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-40-02-0361. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 40, 4 March–10 July 1803, ed. Barbara B. Oberg. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013, pp. 485–486.] (02/12/2024)

La Fayette to Thomas Jefferson, April 20, 1805:

Here I am with my son and daughter in law who is going to increase our family [Charlotte Mathilde]. Her father is to stand god father to the child and if He is a Boy we intend taking the liberty to give Him Your Name.

“To Thomas Jefferson from Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, 20 April 1805,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-1556. [This is an Early Access document from The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. It is not an authoritative final version.] (02/12/2024)

La Fayette to Thomas Jefferson, April 8, 1809:

(…) My Children are in Good Health. Two of them, My daughter in Law [Clémentine Adrienne], and Virginia [Françoise Mélanie] are Going to increase the family.

“To Thomas Jefferson from Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, 14 December 1822,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-3215. [This is an Early Access document from The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series. It is not an authoritative final version.] (02/12/2024)

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#history#letters#founders online#george washington#thomas jefferson#james madison#archieve#resources#1799#1801#1812#1803#1805#1807#1809#1815#1818#1810#georges de la fayette#anastasie de la fayette#virginie de la fayette

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

The U.S.S. Constellation engaging the French frigate L'Insurgente off Nevis, 9th February 1799, by John Bentham Dinsdale (1927-2008)

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

▪︎ Garniture of Flintlock Box-lock Pistols and Accessories.

Maker: Jacinto Xavier (Portuguese, active 1794–1808)

Date: 1799

Place of origin: Lisbon, Portugal

Medium: Steel with engraving, gilding, bluing, and silver inlay; walnut, iron and tortoise shell.

#history#18th century#art#weapon#weaponry#flintlock pistol#blade#jacinto Xavier#portugal#lisboa#1799

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

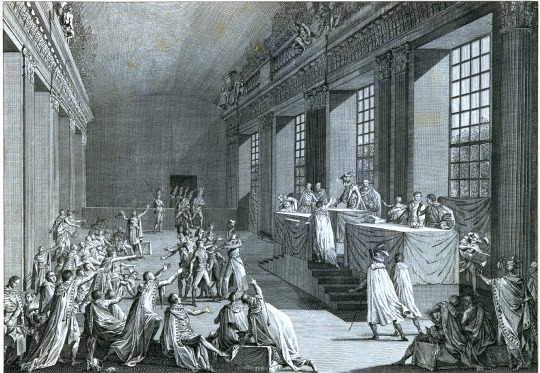

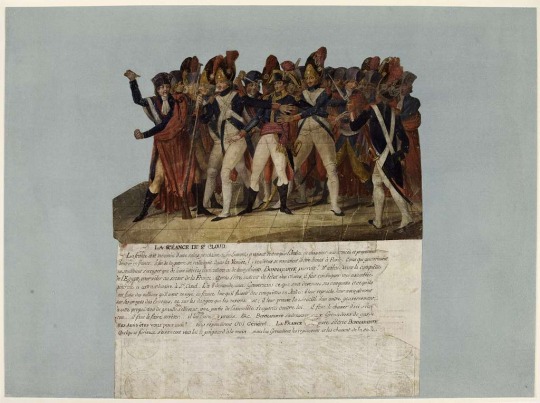

Scenes from 18-19 Brumaire

Jean-Baptiste Morret, Séance du Conseil des Cinq-Cents tenue a St Cloud le 19 brumaire an huit, 1799

C. Chardon (imprimeur), Isidore Stanislas Helman, Journée de Saint-Cloud, le 18 brumaire an 8, 9 Novembre 1799, Musée de la Révolution française

Coup d'État du 18 Brumaire dans l'Orangerie de Saint-Cloud, Domaine national de Saint-Cloud

Gravé par Le Beau d’après Naudet, Coup d'État du 18 Brumaire an VIII

Jacques Sablet, Le Dix-Neuf Brumaire

Jean Baptiste Lesueur, Coup d'Etat des 18-19 brumaire an VIII : Bonaparte menacé par les députés du Conseil des Cinq-Cents, Saint Cloud, le 10 novembre 1799

François Bouchot, Orangerie du parc de Saint-Cloud — Coup d'État des 18-19 brumaire an VIII — Le général Bonaparte au Conseil des Cinq-Cents, à Saint Cloud. 10 novembre 1799

Giacomo Aliprandi, Francisco Vieira ‘Portuense’, Napoleon entering council chamber at St. Cloud, protected by guards with fixed bayonets against daggers of council members

Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard (1780-1850), The Coup of XVIII Brumaire: Bonaparte before the Council of Five Hundred

François Bouchot, Coup d’Etat du XVIII Brumaire : le général Bonaparte au conseil des Cinq-Cents à Saint-Cloud pencil, pen and brown ink and brown wash on paper (A study for the painting at the National Museum of Versailles)

#Brumaire#Napoleon#napoleonic era#napoleonic#napoleon bonaparte#18 Brumaire#18th brumaire#eighteen brumaire#eighteenth brumaire#France#history#french history#first french empire#french empire#1799#1700s#18-19 brumaire#art#painting#drawing#french revolution#illustration#Art history#sketch

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Percy, Larrey and the army administration (1799)

The one thing Dominique Larrey is best known for are the ambulances volantes or flying ambulances who for the first time went onto the battlefield to tend to the wounded. Now, many descriptions of this take it to mean that for the first time the wounded were tended to while the battle was still going on, and that this was absolutely sensational. Which is true to some degree but was not actually the point.

In the first place, the point was to get the medical service to the wounded at all.

According to the old Ancien Régime army regulations still in place at the beginning of the Revolutionary wars, the surgeons had to remain at least one league (~5 km) behind the battle lines and were expressedly forbidden to enter the battlefield before the fighting had ended. Only then the wounded should be carried off the field to some secure place where hospitals could be installed and the surgeons were called in to take care of them.

But even that remained a merely theoretical option most of the time. As taking care of the wounded was, at best, an afterthought for the army administration, the medical service was lucky if they were given enough bandages and other material they needed for their job. There was no provision for how they would follow the army and transport this materal.

So usually, they tried to gather some carts to carry what was to carry, and other than that, they walked. Once the battle had ended and the surgeons and their helpers were informed they could now enter the battlezone and see if somebody in it could still be saved, they had to set out on roads that were utterly overcrowded, at a time when all horses had already been required for the cavalry and the transport of canons. Hardly suprising, they often only reached the place where the wounded were between 24 or even 36 hours later.

It’s true that Larrey as early as 1792/3 had managed to establish a first battlefield unit of surgeons, but this was an experiment and mostly due to one sympathetic general. With Larrey himself being only a rather obscure surgeon among many at the time, this innovation also happened on a miniscule scale, literally only a handful of surgeons following one army unit on horseback with some bandages in their saddlebags. While it did receive lots of praise, it did not change a thing about the general situation. Even later, when Larrey came in close contact with one general Bonaparte who similarly granted him the opportunity to put his ideas into practice, this was restrained to (parts of) the armies of Italy and Egypt.

The overall situation becomes evident when reading the 1799 entries in the Journal de campagne of Pierre-François Percy, who would later, for the bigest part of the First Empire, become head surgeon of the French army (and thus Larrey’s boss). Percy himself, older and much more renowned than Larrey, at the time was already somewhat higher up the ladder but still helpless in this point. Throughout several decades and against different types of government he fought tooth and nails to improve the situation for the medical service and to wrestle money, material, but also some independence and autonomy out of an army administration utterly unwilling to give up its authority. While it seems Larrey and Percy on several occasions did not see eye to eye (as much as it was possible for good-natured Percy to be cross with somebody, especially as he greatly respected Larrey’s skills and expertise), they were united in this constant struggle against the army administration.

Unlike Larrey’s memoirs Percy’s notes were a mere diary, entirely personal and never intended for publication. They also have the advantage of being, for the biggest part, almost written day-to-day and on the spot, so they offer a very immediate view on what was going on. The main difference between Larrey’s and Percy’s writings, in my opinion, is their tone: Larrey writes military memoirs, he is at the frontline and shares the dangers and glories of the battlefield, and even the descriptions of successful surgeries add to the imperial glory (and to the author’s personal glory, of course). Percy, as to him, arrives later, with the actual medical staff, he is not in Napoleon’s immediate entourage and sees what happens behind the army: the destruction, the ruined villages, the diseases spreading from soldiers to locals, the utter insufficiency of what he is given to work with. The dark side of the story, so-to-speak.

The quotes below are from March 1799, about the surgeons following the vanguard of the army crossing the Rhine at Kehl. Nothing fancy, just some evidence of how little attention was paid to the needs of the army’s medical service.

In the vanguard ambulance marched, on foot, as is customary, the surgeons of all ranks attached to its service; the chiefs had not had time to obtain horses; the young men had not had the means; and yet they were all newly fitted out, and on their clothes shone the new embroidery distinguishing their ranks and professions.

Which apparently already was a big deal – at least now they looked as if they were an actual part of the army. But other than that, not much had changed, despite new regulations:

They were to be given a wurst of the mounted cannoneers to transport them wherever the troops went, and above all to enable them to faster and more readily reach the battlefield, where surgeons on foot usually arrive only after running and hastening more or less great a distance, which exhausts them, puts them out of breath and makes them, consequently, ill-suited to helping the wounded.

A wurst being a nickname for a certain type of longish carriage:

Percy had, after an exhausting struggle, managed to get permission to use such vehicles. Theoretically.

The proposal I had made to our generals to provide my colleagues in all the divisions, and especially in the vanguard, with this kind of lightweight carriage, on which ten individuals can ride astride without being hindered, and the explanation I had given them of the singular advantages to be gained for the safety, promptness and efficiency of the service, pleased them so much that they immediately ordered several of the said wursts to be placed at my disposal, unharnessed, which was done with pleasure and eagerness by the senior artillery officers concerned by this object; but the ambulance crews had to provide the horses themselves, and this was the stumbling block for our project.

Because obviously, in order to receive the horses, the medical service had to refer to the army administration.

The horses were not refused, but hindrances, setbacks and pretexts were multiplied, and the wursts drawn from the arsenal for the relief of the surgeons and the well-being of the wounded had to be returned, because it would perhaps have been a dangerous spectacle to present that of medical officers in carriages, they whom a system of malice, oppression and humiliation has condemned for so long to be covered in dust and mud: we want them to go on foot and be unhappy; otherwise, say some administrators, they'd become too insolent.

And while Napoleon was quite ready to honour some high-ranking personalities of the medical service, Percy and Larrey among them, the overall situation remained unchanged under his rule, too.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

#historical fashion polls#historical fashion#historical dress#fashion poll#fashion plate#18th century fashion#1790s#1790s fashion#fashion history#dress history#polls#tumblr polls#1795#1796#1797#1798#1799#1800

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

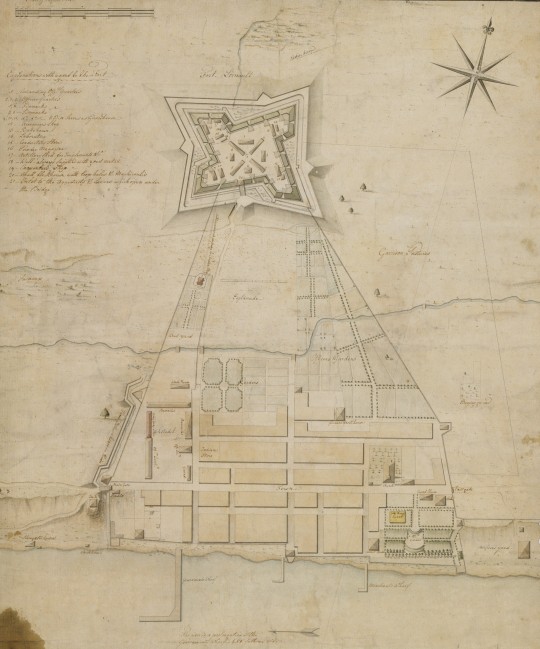

Plan of Fort Lernoult and the town of Detroit, by John Jacob Ulrich Rivardi, 1799.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gallery of Fashion, vol. V: April 1, 1798 - March 1 1799

From the Met Museum

#gallery of fashion#fashion#fashion history#dress#fashion plate#print#history#1798#1799#1790s#1700s#18th century#georgian

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costume Parisien, 22 septembre 1799, An 7 (159): Vue de Tivoli. Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands

Dress with a checked bodice. Tied ribbon on the back, hem decorated with a geometric motif. Short sleeves and train. Accessories: hat decorated with flowers, fan, flat shoes with pointed toes. The print is part of the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published by Pierre de la Mésangère, Paris, 1797-1839

#Journal des Dames et des Modes#18th century#1790s#1799#on this day#September 22#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#color#description#rijksmuseum#dress#Mésangère

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oil Painting, 1799, French.

By Guillaume Guillon Lethière

Portraying Adèle Papin in a white empire-waist dress.

Tajan.

#Tajan#1799#1790s painting#directoire#Adele papin#Guillaume Guillon Lethière#french revolution#1790s France#1790s dress#painting#french#1790s womenswear

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

Heyy, have you ever wrote about Lafayette and Napoleon's feelings/contact with each other?

'cause even knowing some stuff about them, i think that there might be more for it than I know

Thankss <3

Dear Anon,

the relationship between La Fayette and Napoléon was a very complex and layered one, but I will try to give you detailed summary.

The first link between La Fayette and Napoléon was in January of 1791 when a young Napoléon mentioned La Fayette in a letter to his friend Matteo Buttafoco. The letter and commentary on it can be found in this post here.

The next serious connection between these two man came when Napoléon defeated the Austrians and the Treaty of Campo Formio was signed, thus freeing La Fayette and his fellow prisoners from Olmütz. La Fayette, duly thankful to Napoléon, wrote the General a note of thanks. Again, the letter itself and commentary can be found in this post here.

La Fayette spend the next years in exile and he and Napoléon had next to no real connection at the time. This all changed when La Fayette, due to the brilliant work of Adrienne, returned to France during Napoléon’s Coup d’État in 1799.

His name and the names of many of his family members were still on the list of émigrés so legally they could not return to France. When La Fayette did so anyway, Napoléon was not amused. He was eventually consoled by Adrienne and Napoléon eventually restored La Fayette’s citizenship in March of 1800.

La Fayette was banned from attending the memorial service for the American General George Washington who died on December 14, 1799. George Washington had been a close friend, confident and father figure for La Fayette. Despite all this, La Fayette’s and Napoléon’s relationship still was rather friendly. They actually had a certain respect for each other as Generals but especially Napoléon was from the start quite wary around the Marquis. La Fayette had been vastly popular in France and still was. His popularity had greatly suffered during the second half of the French Revolution but his time in prison and the actions of his wife had partly helped to restore it. La Fayette had no political ambitions when he returned to France and his popularity was still tarnished but he nevertheless could have posed a threat to Napoléon if he really, really would have wanted that. The two of them met a few times at social functions and also exchanged letters but their relationship deteriorated more and more with time. They were similar in one aspect though, they both longed for glory – but their approach was different.

Napoléon hoped to gain La Fayette’s support for his government but La Fayette refused to serve in the Senate and to become the French ambassador to his beloved America, although both positions were suggested to him through different sources. La Fayette was also offered to be made a member of the Legion of Honour. He again refused. He had no interest of being overly entangled with Napoléon. Although not being outspoken in public La Fayette would not keep his opinions for himself if somebody asked him about his opinions. Actually, there was no need asking him about his opinions, La Fayette was one of the most well-known men in France, everybody even remotely interested in politics knew his stance. There is a passage from a conversation Napoléon and La Fayette had in the summer of 1802:

‘I [Napoléon] must tell you, General Lafayette, and I see with regret that, by your manner of expressing yourself on the acts of the government you give to its enemies the weight of your name.’ Lafayette replied, ‘What better can I do? I live in retirement in the country, I avoid occasions for speaking; but whenever anyone comes to ask me whether your regime conforms to my ideas of liberty, I shall answer that it does not; for, General, I certainly wish to be prudent, but I shall not be false.’

Bayard Tuckermann, Life of General Lafayette; with a critical estimate of his character and public acts, Vol. 2, Low, London, 1889, p. 158.

La Fayette did not trust Napoléon and did not wish to be part of his government. La Fayette voted against the consulship for life and this decision was at least from Napoléon’s point of view the final nail in the coffin of their relationship. La Fayette explained to Napoléon himself in a letter from May 20, 1802:

General – When a man who is deeply impressed with a sense of the gratitude he owes you, and who is too ardent a lover of glory to be wholly indifferent to yours, connects his suffrage with conditional restrictions, those restrictions not only secure him from suspicion, but prove amply that no one will more gladly than himself behold in you the chief magistrate for life, of a free and independent republic.

Life of Lafayette: Including an Account of the Memorable Revolution of the Memorable Revolution of the Three Days of 1830, Light & Horton, Boston, 1835, pp. 1.

But La Fayette was still somewhat out of Napoléon’s reach. But his son, who joined the military in 1800, and his son-in-law, Louis de Lasteyrie, were not. Although both of them and especially Georges, distinguished themselves in battles, they were not promoted. Whenever a promotion for one of them was up for debate, it never came to pass. La Fayette’s son and son-in-law therefor left the army in September of 1807 – there was just no point in serving any longer.

During the 100 Days, Napoléon’s brief return to power after his exile on St. Helena and prior to his exile on Elba, La Fayette became outspoken once again. He had been elected to the Chamber of Representatives (not to be confused with the Chamber of Deputies; both were the lower chambers of the French Parliament but the Chamber of Deputies was active during the Bourbon Restoration, the Chamber of Representatives was only active during The Hundred Days) in 1814. He had previously argued that too little people in France were eligible to vote the members of the Chamber of Deputies that such a political body could never represent France. Anyway, La Fayette was pretty silent as a Representative until June 21, 1815, after Napoléon’s defeat at Waterloo. The Chamber meet early that day to discuss the general state of affairs. La Fayette rose and proposed the following:

Representatives! For the first time during many years you hear a voice, which the old friends of liberty will yet recognize. I rise to address you concerning the dangers to which the country is exposed. The sinister reports which have been circulated during the last two days, are unhappily confirmed. This is the moment to rally round the national colours—the Tricoloured Standard of 1788—the standard of liberty, equality, and public order. It is you alone who can now protect the country from foreign attacks, and internal dissensions. It is you alone who can secure the independence and the honour of France.

Permit a veteran in the sacred cause of liberty, in all times a stranger to the spirit of faction, to submit to you some resolutions which appear to him to be demanded by a sense of the public danger, and by the love of our country. They are such as, I feel persuaded, you will see the necessity of adopting:

I. The Chamber of Deputies declares that the independence of the nation is menaced.

II. The Chamber declares its sittings permanent. Any attempt to dissolve it, shall be considered high treason. Whosoever shall render himself culpable of such an attempt shall be considered a traitor to his country, and immediately treated as such.

III. The Army of the Line, and the National Guards, who have fought, and still fight, for the liberty, the independence, and the territory of France, have merited well of the country.

IV. The Minister of the Interior is invited to assemble the principal officers of the Parisian national Guard, in order to consult on the means of providing it with arms, and of completing this corps of citizens, whose tried patriotism and zeal offer a sure guarantee for the liberty, prosperity, and tranquillity of the capital, and for the inviolability of the national representatives.

V. The Ministers of War, of Foreign Affairs, of Police, and of the Interior are invited to repair immediately to the sittings of the Chamber.

Bayard Tuckermann, Life of General Lafayette; with a critical estimate of his character and public acts, Vol. 2, Low, London, 1889, pp. 190-193.

The resolution was soon adopted with the exception of the fourth paragraph. Please note that the exact wording of La Fayette’s little speech differs a little bit from translation to translation, but the gist is always the same. La Fayette more or less openly called for the abdication of the Emperor Napoléon. When Napoléon’s brother urged the Chamber to reconsider La Fayette answered him that (again, different sources translate slightly different):

Who shall dare to accuse the French nation of inconstancy to the Emperor Napoleon? That nation has followed his bloody footsteps through the sands of Egypt and through the wastes of Russia; over fifty fields of battle; in disaster as faithfully as victory; and it is for having thus devotedly followed him that we now mourn the blood of three millions of Frenchmen.

Life of Lafayette: Including an Account of the Memorable Revolution of the Memorable Revolution of the Three Days of 1830, Light & Horton, Boston, 1835, p. 114.

Yes, la Fayette could give quite a speech - if he wanted to. Other the next days, Napoléon was urged to abdicate (June 22, 1815) with the threat that the Chamber would otherwise abdicate for him. The Chamber selected a committee of fife men to meet with delegates of the allied forces for the allies had promised peace negotiations, provided Napoléon was not longer in power. One of these fife men was La Fayette. There are not too many letters from La Fayette about these events that I can show you, but here is an excerpt from a letter to Thomas Jefferson from October 10, 1815:

In your Letters of Last year, anterior to the first Abdication of Bonaparte, you Had Expressed a due Sense of that Character who Having it in His Power to Be a Blessing did prefer to Become a Curse to Mankind. His despotism and His follies Had made the Restoration of the Bourbons, notwithstanding foreign invasion, a popular Event—They Returned the Compliment. Their prejudiced mismanagement, the more Glaring improprieties of Privilege-men Gave Napoleon the Opportunity to Reappear as a Representative of the Revolution. Whatever may Have Been a few Subaltern Intrigues, the Great, the Efficacious Conspiracy in His Behalf may Be attributed to the Counter Revl[uti]onary party.

in those transactions I took No part altho’ I would Have Readily assisted in Opposing Napoleon Had Not the patriotic System me[t] the Same objections which Had Ruined the Constitutional throne of 92.

We then Have Seen the Imperial destroyer of french Liberty Reassuming a Republican Language, Bowing to [na]tional Sovereignty, allowing a free press, and altho’ Vindictive or Arbitrary acts too often Betray’d old Habits, persuading many patriots to Rejoice at His Conversion—Not So did I—But While I Shunned personal Communication with Him, I declared that, if a free Representation was Convened, I would Stand a Candidate—we were, my Son and myself elected.

at the Same time a million of foreign invaders were, in Concert with Lewis the 18t and the elder Branch of His family, Led Against Bonaparte, was it Said, against what and whom the Event Has proved—the defense of national independance and territory Became, of Course, our principal object. it was my opinion that Unanimity and vigor Could Better Be Roused By a popular than By the Imperial Government—The Majority of the Assembly and Army depended more on the General Ship of Napoleon altho’ His whole troops did little Exceed two Hundred thousand. So we all joined on that Line of Resistance. No impediment was thrown, Every Assistance was Given. Never did our Heroïc Army fight Better than at waterloo. a Stubborn Mistake of Bonaparte Lost the day. He deserted His Soldiers, and Determined to dissolve our Assembly, usurp dictatorial powers, prefering the chances of Confusion and involving destruction to those of firmness and patriotism. That part of the impending Evils was timely prevented. it might Have Been the Case with the other part, altho’ Coming upon us in a Storm, Had Not the old diplomacy in poland, Napoleon’s policy in Spain, the Spirit of pilnitz in 91, and of the Last Congress at vienna Been far Surpassed By the present Coalition.

inclosed you will find a few pieces Relative to our Late House of Representatives. their declaration of the 5t July 1815 Congenial with the principles of 1789 are an additional proof that if the french people Have deplorably Erred in the means they Have Steadily persevered in the primary object of the Revolution.

“Lafayette to Thomas Jefferson, 10 October 1815,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series, vol. 9, September 1815 to April 1816, ed. J. Jefferson Looney. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012, pp. 67–69.] (05/22/2023)

After Napoléon’s abdication, the relationship between him and La Fayette effectively ended safe for one important letter that I would like to show you. La Fayette had himself been a prisoner of war for several years and he had suffered under the conditions imposed upon him. When there was talk that the British mistreated Napoléon on Saint Helena, La Fayette wrote a letter to the American Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford in 1819 – and as before, the letter can be found in this post here.

I hope this answer is helpful to you and I hope you have/had a wonderful day!

#ask me anything#anon#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#napoleon bonaparte#napoléon#french revolution#french history#american history#history#letter#1815#1819#thomas jefferson#william h. crawford#founders online#george washington#1799#1800#1802#la fayette in prison#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#georges de la fayette

73 notes

·

View notes