#2) rape one in a song supposed to be from the perspective of god and i dont rmbr the other time but it def was i think

Text

Good Omens recs

Here are some of my all time favourite stories, but be warned that my taste is rather specific and can get into darker themes. I especially like hurt/comfort focused on Aziraphale, but that’s not the only thing you’ll encounter in this list.

The Strong Tower by @aziraphalelookedwretched (M, 41,458)

After the failed executions, a vengeful angel takes it upon herself to neutralise the threat presented by Crowley and Aziraphale.

All stories by BuggreAlleThis are wonderful even if they get very dark in places. There (almost) always is comfort that’s more than worth the hurt and I love them all, but this one remains special to me as one of the first stories I read in this fandom and awaited every update eagerly.

White Walls and Dead Air by BabyHoldMyFlower (G; 3,382 words)

It’s after the fourth day that he decides he hates God. He’s too tired to hold it back. Too miserable. Too busy dying. He knows he’ll go back on it later. He knows that he’ll repent later, and he’ll mean it, he thinks, once he gains some perspective, but there is nothing that could stop this bone-deep agony from churning and rising into something ugly. He’s not supposed to feel this way. He’s an angel, he really shouldn’t be thinking these things. Blind obedience is what they were created for. It’s in this moment that he can admit to a flaw in the Almighty’s design. If she wanted soldiers, she shouldn’t have given them the capacity to love.

Beautifully written and bittersweet, with lovely wing grooming and insights into the characters.

A Demon Would A-Wooing Go by @shinyhappygoth (G; 301 words)

“Heigh ho,” said Anthony Crowley, and just drove anyway.—Good Omens

Filk of "A Frog He Would A-Wooing Go".

I just love a silly take on a silly folk song that was actually referenced in the book, okay?

Flaming Sword by Bookwormgal (T; 8,576 words)

A dark shape in the not-quite-empty darkness. Dressed in black robes. Humanoid. Skeletal. Then wings unfolded. Angel wings, but not ones of feathers. Wings of night. Wings that Aziraphale could sense more than see in this strange place. And even if the thin thread didn't truly exist except as a concept to better understand what was happening, one skeletal hand rested on the weakening connection. Waiting patiently.

Azrael. Creation's Shadow. The Angel of Death.

"Oh," he said quietly, his voice swallowed by the emptiness.

Aziraphale remembered what happened. He remembered moving. He remembered the blade sliding in, sharp and sudden. He remembered pain. And then…

"I died, didn't I?" he asked.

I like the exploration of the theme of self-sacrifice here. This is just my personal pick from several of my favourite stories from this author.

Courage by Anonymous (E, 21,595 words - WIP)

Ten years after the world didn’t end, Heaven and Hell want to punish Aziraphale and Crowley for their treason. Gabriel decides that the perfect way to punish both of them is to torture Aziraphale and force Crowley to watch; Hell agrees to the plan. Aziraphale and Crowley are kidnapped from their South Downs cottage and taken to a neutral location; Aziraphale is tortured and raped and Crowley is forced to watch; they are then returned home, Aziraphale critically injured.

This is the Prologue (the first three chapters; all of the violence is confined to chapter 2, which can be skipped).

The real story begins in chapter 4; it’s the story of how Aziraphale and Crowley recover from the trauma. They are both profoundly traumatized; it takes a long time, but they work through it together, and their marriage recovers. There will be a happy ending.

Aziraphale and Crowley heal each other.

This story is a WIP, but it already got to the part where things are getting better. It’s very (very!) heavy, but absolutely beautifully written, it’s giving me goosebumps.

Love Seeketh Not Itself to Please by die_traumerei (T, 14,645 words)

After Aziraphale is left gravely injured by a summoning, Crowley must take him to heaven and bargain with the angels for his life. It doesn't go as he'd expect.

A hurt/comfort story that’s focused on the comfort part, really satisfying to read!

Evolution by @lady-divine-writes (M; 1,455 words)

Five times Aziraphale wasn’t the most confident Dom, and the one time it finally clicked.

Again I’m only picking one story, but there are so many more from this author that I love! I bookmarked this one because I don’t usually see Aziraphale as Dom, but here he is fully in character and gets there through conscious effort, and it feels very empowering.

The Longest Night by @charlottemadison42 (series rated T-E, 34,747 words)

The night the Apocalypse doesn't happen, an angel and a demon share a bus bench on the way home to face their fates. This is the story of their evening spun out line by line, all the little moments that carried them through the night they knew might be their last.

A wonderfully written series giving a detailed account of the night before the trials, complete with drunken talk, with wonderful grasp of the characters. Again just a personal pick from the stories by a really great writer.

Who Needs Heaven (when we have each other)? by Kat_Rowe (series rated G-M (so far), 48,057 words so far)

Now that they're independent of Heaven and Hell, Aziraphale and Crowley become even closer. Friendship eventually turns to romance, and emotional intimacy to physical. (Slow-burn friends-to-lover fic series.)

A very gentle series starting with wing grooming and continuing through the exploration of a relationship in which one of the partners (Aziraphale) is asexual.

Fancy Patter on the Telephone by @hotcrosspigeon (G, 12,854 words)

A series of telephone conversations between Aziraphale and Crowley during the Lockdown.

They get steadily more desperate and ridiculous as the weeks go on.

Featuring a moping demon, a teasing angel, a pub quiz, an explosion, extraordinary amounts of alcohol, a bubble bath, awkward flirting, several love confessions... and an ill-conceived bet on who can last the longest without seeing the other.

What could possibly go wrong?

HotCrossPigeon is an amazing hurt/comfort writer who writes absolutely delightful Aziraphale ahurt/comfort from Crowley’s spot-on POV, so definitely check their other stories as well, but I just had to pick this one that’s actually humorous and doesn’t contain even a drop of blood because I couldn’t stop laughing with it.

Feathers by @29-pieces (series rated G; 23,247 words)

Pre-Apocalypse shenanigans. In this AU, when an angel and a demon fight, the victor customarily takes a feather from their opponent signifying victory over them. Usually followed by killing them, naturally. But sometimes the defeated angel or demon is left alive, minus a feather, so that everyone KNOWS.

Neither Crowley or Aziraphale ever took part in that sort of thing because it's really just a mean thing to do.

A series of three stories, two with hurt Aziraphale and one with hurt Crowley.

5 Times Aziraphale was Almost Discorporated and One Time He Actually was by @charliebrown1234 (series rated T-M; 29,011 words)

This series is an absolute match for my need of Aziraphale hurt/comfort, just like their more recent story Ex Infirmitas, Sinceritas. One of the authors I’m subscribe to and read everything they write.

The Whole Sky Fell by @thepaisleyelf (T, 9,692 words)

“Okay, Aziraphale, out with it,” Crowley said finally. “What’s wrong?”

Aziraphale blinked. He suddenly seemed very interested in looking anywhere that wasn’t at Crowley, fiddling with the napkin in his lap.

“I don’t -- I’m afraid I don’t know what you mean.”

Aziraphale really was a terrible liar. Under other circumstances Crowley might have found it charming, cute even, but his concern had been growing ever since he’d picked Aziraphale up for breakfast that morning....

Same as above, Turcote just knows what I love to read. Definitely check their other stories as well!

Desperate Ground by @desperateground (M, 55,883 words)

After they prevented the apocalypse and escaped execution, Crowley and Aziraphale thought they were safe from the machinations of Heaven and Hell. But there are still some demons with scores to settle - and since the angel and demon have made it clear to the world how far they're willing to go for each other, Hell has plenty of leverage on them.

A breathtaking story with torture and unwavering loyalty of the characters to each other.

***

And if you find these recs to your taste, then you might also enjoy

Back to the Roots by me (M, 90,946 words)

"We always knew it would end. Like mortals know that they'll die." Crowley closes his eyes, finding the stare of his own reflection unbearable. "When you're immortal, you can afford to pretend and hide and go slow. And then, when you finally figure it all out, it turns out that what you have can end anytime. It's unfair..."

----------

The morale in Heaven and Hell is low after the failed Apocalypse. Punishing the traitors (effectively this time) seems like a good idea to raise it for both sides - the angels would see what awaits them if they dare to disobey and the demons could just use some fun. And then there is someone else as well - someone whose grudge is even more personal.

Also torture and unwavering loyalty, breaking the characters and then putting them together with great care. This is the darkest from my stories, so if torture is not your thing, you can check my other ones (mostly Aziraphale hurt/comfort too).

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

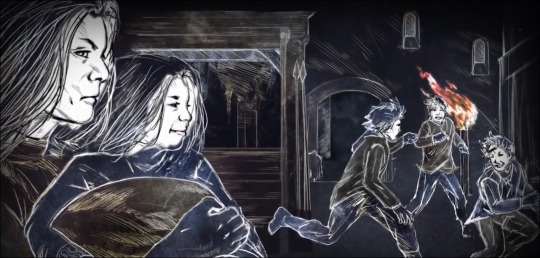

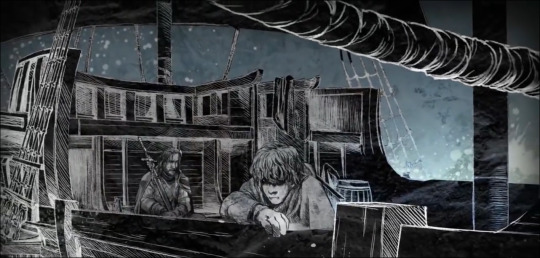

Theon and Robb tell the History & Lore of the Greyjoy Rebellion (Part 1)

Rewatching these videos, a bunch of thoughts I had started to come together and it became a Thing. A very long thing.

The "Histories & Lore" featurettes are short animated videos, narrated in-character by relevant cast members, that appear as bonus material on the Game of Thrones blu-rays. They flesh out the world by essentially providing book exposition that the writes couldn't fit into the show.

(Transcripts were copied off the Wiki and then edited by me to correct errors in them.)

First off, the videos themselves:

youtube

"Dark wings, dark words". I was only a boy when the raven came to call my father, Lord Eddard Stark, to another war. Balon Greyjoy had raised the Iron Islands in revolt, and burned the Lannister fleet at anchor. King Robert Baratheon again needed his old friend.

My mother, Catelyn, was not happy to lose her lord husband to Robert again. Six years before he had left her to avenge his father and brother against the Mad King. But now he had sons and daughters of his own, and, unspoken, another son who wasn't hers from the last time he went to war: my brother, Jon Snow.

But she knew that in marrying my father she had married The North, we hold our honor and duty as dear as our own gods. When the time came, my father marched south to restore peace and order to the realm.

My father always told me the Iron Islands were a strange and dangerous place. Its people, the ironborn, keep neither the Old Gods nor The Seven, and despise all honest toil. Their ancestors ravaged the western shores, raping and slaving and putting it to the torch. And their songs still ring through the halls of the ironborn; while everywhere else they are whispered to wayward children at bedtime.

Perhaps Lord Balon thought Westeros had not healed from the war against the Mad King and was as fragmented and suspicious as the ancient kingdoms his forbears had terrorized. Robert's navy corrected him at Fair Isle, when they smashed the proud Iron Fleet. Robert and my father corrected him at Pyke, his own castle, when they pulled down his towers and breached his walls.

My father never liked to speak of his battles, but from other men I learned what transpired: Thoros of Myr was first through the breach with his flaming sword. Not far behind him was Jorah Mormont of Bear Island, my father's bannerman who earned the knighthood he would later shame, and lords from every corner of the Seven Kingdoms. All day through every passage in the castle they fought side by side: my father with our ancestral sword Ice and King Robert with his warhammer, against a horde of axe-wielding ironborn. In the end, Lord Balon bent the knee.

King Robert generously allowed Lord Balon to retain his title and castle. The price of peace was custom: The only son of Balon's to survive his foolish rebellion would be taken as a hostage against future treasons. My father even volunteered to foster the boy himself.

I suspect to make Theon Greyjoy a different man than his father, who would bring honor and duty to the Iron Islands when he returned as heir. So my mother's silent fear came true, and my father returned with another child. Theon ate with us, played with us, and fought with us.

Once the great bond between my father and Robert Baratheon united the realm against the Mad King, and brought him to justice for his crimes. Now, another monster sits on the Iron Throne, and another debt of blood is owed my family. Theon is my murdered father's ward; I am my murdered father's son. Like my father and Robert, bound in blood if not by blood, we are brothers.

The following video is actually a compilation of three different featurettes. The one that is of interest is the third one, which starts at about 6:23. However the others are interesting too. The first one is Theon and Yara narrating the history of House Greyjoy. In the second Stannis Baratheon gives his perspective on the Greyjoy Rebellion, including details on how he destroyed the Iron Fleet.

youtube

When Aegon and his dragons burned Harren the Black and all of his sons at Harrenhal, the days when men feared the sight of our longships were over: Aegon would not permit marauders and raiders in his Seven Kingdoms. With Harren died our empire, and the old way that forged it. But what is dead may never die.

Six years after Robert Baratheon won his crown, my father - Balon Greyjoy- sought to restore our ancient rights. He declared the Iron Islands independent, and himself its king; and sent the Iron Fleet in a daring raid on Lannisport where they burned the Lannister ships at anchor, making us unchallenged in the Sunset Sea. This was the seed of the our undoing.

My eldest brother, Rodrik, led a frontal assault on Seagard, a town built to protect the mainland from us. After ferocious fighting beneath the city walls he was slain by Lord Jason Mallister, and his men defeated.

By this time Stannis Baratheon had brought Robert's fleet around Westeros and somehow managed to trap the Iron Fleet at Fair Isle, smashing it. Robert's victory was now all but assured, yet we made him bleed for each island.

Stannis Baratheon captured Great Wyk, the largest of the Iron Islands, and Ser Barristan Selmy himself subdued Old Wyk. Robert and Lord Eddard Stark led the main assault against the island of Pyke. They razed the town of Lordsport to the ground before Robert turned his full fury on our family stronghold.

When they breached the walls the first through was Thoros of Myr with his ridiculous flaming sword, followed by every minor lord of Westeros hungering for glory. My other brother, Maron, was killed when siege engines brought down a tower on his head. I was now my father's only living son, and heir to the Iron Islands.

When my father saw his cause was lost he wisely conceded defeat to Robert, who otherwise would have pulled down the castle stone by stone with us in it.

As my father said to me then: "No man has ever died from bending his knee. He who kneels may rise again, blade in hand. He who will not kneel stays dead, stiff legs and all". As it stands Robert allowed my father to keep his lands and title as Lord of the Iron Islands, King of Salt and Rock, Son of the Sea Wind, Lord Reaper of Pyke... for a price. His last son and heir shipped off to Winterfell as an "honored guest".

I would eat at the Stark's table and play with the Stark children. And if my father rebelled again, Lord Eddard would take his sword and cut off my head. It would be his duty.

One thing that struck me about the videos was the differing perspectives on Theon's situation. Theon and Robb viewing the Rebellion differently is one thing, but even Theon leaving is framed differently, with Robb seeing it neutrally (if not positively), and Theon…not so much.

There's also the framing of them playing as kids, which I suspect is more a manifestation of Theon's mental state in book/season two than of reality.

But more than that, I couldn't help but notice what is and is not said about family, specifically, Theon's family.

Robb: "But now [my father] had sons and daughters of his own, and, unspoken, another son who was not hers from the last time he went to war: my brother, Jon Snow." "So my mother's silent fear came true, and my father returned with another child." "Like my father and Robert, bound in blood if not by blood, we are brothers."

Robb mentions his own siblings and how he considers Theon a brother, but never even thinks to mention Theon's own dead brothers…which Theon does bring up.

"My eldest brother, Rodrik, led a frontal assault on Seagard…he was slain by Lord Jason Mallister, and his men defeated." "My other brother, Maron, was killed when siege engines brought down a tower on his head. I was now Balon's only living son, and heir to the Iron Islands."

See also, little Theon apparently seeing part of his brother's crushed body!

Then again, with the way Theon talks about his brothers, maybe that's not so surprising….

[Speaking to Patrek Mallister] "When my brother stormed Seagard," Theon said. Lord Jason had slain Rodrik Greyjoy under the walls of the castle, and thrown the ironmen back into the bay. "If your father supposes I bear him some enmity for that, it's only because he never knew Rodrik." [A Clash of Kings - Chapter 11 - Theon I]

Later in the same chapter:

"This wolf king heeds your counsel, does he?" The notion seemed to amuse Lord Balon.

"He heeds me, yes. I've hunted with him, trained with him, shared meat and mead with him, warred at his side. I have earned his trust. He looks on me as an older brother, he—"

"No." His father jabbed a finger at his face. "Not here, not in Pyke, not in my hearing, you will not name him brother, this son of the man who put your true brothers to the sword. Or have you forgotten Rodrik and Maron, who were your own blood?"

"I forget nothing." Ned Stark had killed neither of his brothers, in truth. Rodrik had been slain by Lord Jason Mallister at Seagard, Maron crushed in the collapse of the old south tower . . . but Stark would have done for them just as quick had the tide of battle chanced to sweep them together. "I remember my brothers very well," Theon insisted. Chiefly he remembered Rodrik's drunken cuffs and Maron's cruel japes and endless lies. "I remember when my father was a king too." He took out Robb's letter and thrust it forward. "Here. Read it . . . Your Grace."

I'll come back to this point in a later post.

Part 2 | Part 3

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The discussion about “literature” in Asia Minor has received new impulses in recent years, in that questions have been raised about the transmission history, origin and compilation, but also about the purpose and sponsorship of such texts. For some time now, literary theories have also been given greater consideration in the development of texts from Asia Minor. Such questions were therefore - in the casual connection to two conferences held in 2003 and 2005, which primarily focused on religious topics of Anatolian tradition - at the center of a symposium in February 2010 in the Department of Religious Studies of the Institute for Oriental and Asian Studies from the University of Bonn. The reference to the two earlier conferences is not only established by the same place of publication, but also, in terms of content, there are undoubtedly points of contact between the history of religion and the history of literature in Hittite Asia Minor; for a considerable part of the written tradition of the Hittites is related to rituals, mythologies and the transmission of religious ideas.

As a pragmatic basis, “literature” was understood as a culture worthy of handing down written material for the symposium's question, without making this description too narrow for the symposium. This made it possible in the context of the contributions to raise a number of questions that could focus on different aspects of the literary tradition of Hittite culture depending on the interests. Some of the questions discussed during the symposium focused on literary theories, and some of the processes of literary production and dissemination were outlined, whereby stylistic forms of expression and motifs in this function were also considered.

Despite the different approaches of the authors, it is not difficult to see thematic similarities in the present volume. Questions of literary theory and literary genres are mainly in the center of the contributions by Birgit Christiansen, Paola Dardano, Amir Gilan, Manfred Hutter, Maria Lepši and Jared L. Miller; Complementary to this literary block are the contributions by Silvia Alaura, José L. García Ramón, Alwin Kloekhorst, Elisabeth Rieken and Zsolt Simon, who examine motifs and linguistic forms of expression in Anatolian texts. How understanding of literature - be it with regard to the statements of a literary work or be it with regard to the conception of such a work - is also promoted by the comparison of texts can be seen in the present volume in the contributions by Sylvia Hutter-Braunsar, Michel Mazoyer, Ian Rutherford, Karl Strobel and Joan Goodnick Westenholz. Finally, the last - no less important - group is the contributions by Gary Beckman, Carlo Corti, Magdalena Kapełuś and Piotr Taracha, who focus on the reconstruction and compilation of individual texts - as the basis for future literary analyzes of these texts.

For the present volume, the individual contributions have been editorially standardized as far as possible, but spellings of names and sometimes also transcriptions of Anatolian words, for which the authors have good reasons, have been left in different forms within the texts. The editorial standardization therefore primarily concerned citation methods and abbreviations, the latter can be broken down using the attached list of abbreviations.

1. The Illuyanka text is undoubtedly one of the best-known Hittite stories. The text was presented by Archibald Sayce in the 1920s. Shortly thereafter, the linguist Walter Porzig drew attention to parallels to the ancient Greek traditions, especially to the Typhon myth. The first "modern" editing of the text was done by Gary Beckman. In the meantime, numerous translations and studies have appeared that illuminate the text from different perspectives. The fascination that the Illuyanka text exudes is partly due to the fact that the myth has been handed down in two different versions - on one and the same board. The text also owes its popularity to the numerous parallels to other narratives of the type "snake dragon slayer". Tales of this kind about a hero who defeats and kills a serpentine dragon have been widespread throughout history in many parts of the world and continue to be so today. They are as good as universal. History can fulfill numerous functions - etiologies of extraordinary natural phenomena, ideological claims to rule, cosmological considerations about the beginnings of the world, religious symbolism or literary entertainment - which often show fairly constant plot structures and are subject to their own narratological logic. As Calvert Watkins (1995) was able to show, many of these narratives also share poetic formulas which are documented for the first time in the Hittite Illuyanka text.

It is noticeable that many kite snakes have an affinity for water in common - an ambivalent and conflicting element in itself. "The fundamental element in the dragon’s power is the control of water. Both in its beneficent and destructive aspects water was regarded as animated by the dragon ”, stated G. Elliot Smith (1919: 103). Also Illuyanka, the (eel) snake, if one follows Joshua Katz (1998) and favors the old etymology of Illuyanka as illi / u (eel, English eel) and -anka (snake, cf. Latin anguis) (see now also Melchert, in press), is closely associated with water in both stories. In addition, in many cultures dragons have a special affinity for water sources (Zhao 1992: 113-114), which also play a role in the Illuyanka text.

In the ancient Orient, the role of this hero is in most cases a weather god in one of his characters. The role of the enemy is occupied in different epochs and regions of the Ancient Orient by the (primordial) sea and a number of eerie creatures that inhabit it or originate from it. In the Syrian region, the battle of the weather god against têmtum is already mentioned in ancient Babylonian times; in a letter from the ambassador Maris in Aleppo, the weather god of Aleppo traces the kingship back to the investiture of his weapons with which he fought against têmtum (Durand 1993: 41-61; Schwemer 2001, 226-232). The weapons of the weather god from this fight, as well as the mountains Namni and Ḫazzi, are mentioned in the Hittite Bišaiša text (CTH 350), a mythological story that has unfortunately only survived fragmentarily. There the mountain god Bišaisa tells the goddess Ištar - after he raped the sleeping goddess, but was caught by her and begged for his life - about the weapons of the weather god with which he defeated the sea (Schwemer 2001: 233; Haas 2006: 212f .). The famous passage in the Puḫānu text, which is often interpreted as the “crossing of the Taurus”, is in my opinion linked. to this mythologist (Gilan 2004: 277-279).

The fight of the weather god against the sea is also a theme of the Hurrian-Hittite Kumarbi cycle. In order to regain control over the world of gods, Kumarbi creates several terrible adversaries who are supposed to defeat the weather god Teššop. Three of these adversaries are closely related to water.

At first the sea god himself was an opponent of the weather god. The song from the sea, which is mentioned in Hurrian and Hittite fragmentary myth and ritual fragments as well as in table catalogs, was probably made during a festival for Mount Ḫazzi (Zaphon, Kasion, today Keldağ on the Bay of İskenderun, the scene of many war and dragon stories ) presented.

Ullikummi was also closely associated with water. Another adversary was Ḫedammu, a snake-like monster (André-Salvini / Salvini 1998: 9-10; Dijkstra 2005). Ḫedammu was conceived by Kumarbi with the gigantic daughter of the sea and because of his voracity caused a famine that threatened to destroy mankind. Help was provided by Ištar, who went to the beach for nude bathing, seduced Ḫedammu there, who crawled excitedly out of the water to land, where he met his end. The Ḫedammu story shows many similarities to the first Illuyanka story (most recently Hoffner 2007: 125), while the "Anatolian" myth of "Telipinu and the daughter of the sea" (Hoffner 1998: 26-28; Haas 2006: 115-117) has a lot in common with the second Illuyanka story. In both narratives, a marriage - and the obligation associated with it - served to prevent danger.

2. The great importance of the Illuyanka text for the history of religion, however, is primarily due to the fact that the mythical narratives seem to be embedded in the ritual - an assumption that has strongly influenced the interpretation of the narratives in research. It is precisely this supposed connection between myth and ritual that will occupy me in the following. Before I get into that, however, I would like to briefly outline the scientific discussion about the relationship between myth and ritual, as the discussion is of crucial importance in interpreting the Illuyanka narrative (s). The question of the relationship between myth and ritual has shaped myth and ritual theory like no other since the end of the 19th century.

It is associated with scholars such as the Old Testament scholar William Robertson Smith, who was the first to point out "the dependence of myth on ritual". The theory was further developed by Sir James Frazer in his monumental masterpiece "The Golden Bough", which grew from edition to edition. Frazer examined various ancient gods, which he interpreted as vegetation gods - including Adonis, Attis, Demeter, Tammuz, Osiris and Dionysus. The myth of death and resurrection of these deities was ritually performed annually during the New Year celebrations to guarantee the revitalization of the vegetation (Versnel 1990: 29f.). “Under the names of Osiris, Tammuz, Adonis, and Attis, the people of Egypt and Western Asia represented the yearly decay and revival of life, especially of vegetable life, which they personified as a god who died annually and rose again from the dead . In name and detail the rites varied from place to place: in substance they were the same ”(Frazer 1961: 164). Segal (2004: 66) describes the meaning of the myth for Frazer as follows: “Myth gives ritual its original and soul meaning. Without the myth of the death and rebirth of that god, the death and rebirth of the god of vegetation would scarcely be ritualistically enacted. ”In the second, more influential Frazerian myth-ritual theory, the deified king is at the center. To end the winter and to guarantee the food supply, the king is killed by the community as soon as he shows weakness but still has strength. The weak phase of the king is equated with winter. His premature killing is to ensure that the soul of the deity who dwells in him can be transferred to his successor (Segal 2004: 66). The "Cambridge Ritual School" around Gilbert Murray, F.M. Cornford and Jane Ellen Harrison took Frazer's theories further. They transferred Frazer's story of the ritual royal drama - his death and resurrection - to Greek society and saw in this basic ritual structure the origins of Greek mythology and Greek drama (Versnel 1990: 30-35; Bell 1997: 5f.). The ritual was considered the source of the myth. Myths originally emerged only as a textual accompaniment to a ritual: "The primary meaning of myth ... is the spoken correlative of the acted rite, the thing done" (Jane Ellen Harri-son, quoted in Segal 1998: 7). However, myths could live on in literary forms after the rituals from which they arose have long since disappeared (Bell 1997: 6).

The Old Testament scholar Samuel Henry Hooke turned to the ancient oriental religions (Versnel 1990: 35-38) and was able to reconstruct a ritual scheme (cult pattern) that is reminiscent of Frazer's ritual royal drama (Segal 1998; 2004: 70-72). Here too, the focus is on the deified king, who represents the deity in the festive ritual. According to Hooke, the following elements belong to the great New Year celebrations - the climax of the cult calendar year - as well as to other rituals (Hooke [1933] in Segal 1998: 88-89):

(1) The dramatic representation of the death and resurrection of the god.

(2) The recitation or symbolic representation of the myth of creation.

(3) The ritual combat, in which the triumph of the god over his enemies was depicted.

(4) The sacred marriage.

(5) The triumphal procession, in which the king played the part of the god followed by a train of lesser gods or visiting deities.

The Babylonian Akītu festival was of central importance for the development of the cult pattern as well as other theories of the myth and ritual school. Scenes such as the humiliation of the king in Esagila on the 5th of Nissanu, the recitation of Enūma eliš in the festival and the so-called Marduk Ordal offered the myth ritualists perfect parallels between king and deity, myth and ritual. For them, the ritual treatment of the king, his humiliation and possible re-enthronement reflected exactly the original mythological event in illo tempore - the fight of Marduk against Ti’amat and her troop of demonic monsters in enūma eliš (Versnel 1990: 36f.). Hooke's ritual narrative was further developed and modified by Theodor Gaster. For Gaster (1954: 198) too, myths are only myths if they are used or used in the ritual. Myths supplement the practical, functional level of the rituals with an eternal, ideal component. The myth "stands in fact in the same relationship to Ritual as God stands to the king, the 'heavenly‘ to the earthly city and so forth "(Gaster 1954: 197f.). With the simultaneous performance of myth and ritual, a cultic drama arises in which the myth is brought to mind (Gaster 1950: 17). The focus of his ritual theory is the seasonal pattern. "Seasonal rituals are functional in character. Their purpose is periodically to revive the topocosm, that is, the entire complex of any given locality conceived as a living organism. They fall into the two clear divisions of Kenosis, or Emptying, and Plerosis, or Filling, the former representing the evacuation of life, the latter its replenishment. Rites of Kenosis include the observance of fasts, lents, and similar austerities, all designed to indicate that the topocosm is in a state of suspended animation. Rites of Plerosis include mock combats against the forces of drought or evil, mass mating, the performance of rain charms and the like, all designed to effect the reinvigoration of the topocosm "(Gaster 1961: 17). In Thespis Gaster (1950: 315-380) offers a selection of ancient oriental mythological texts, partly also in translation, in which he discovered the traces of this seasonal cult scheme, including a number of Hittite texts, myths that are even still in their "original" ritual packaging are handed down. These include the Telipinu myth, the myth of the frost Ḫaḫḫima, the myth of the disappearance and return of the sun deity and The snaring of the Dragon, i.e. the Illuyanka text embedded in the Purulli festival.

The myth ritualists gained great influence in many areas of the humanities, especially in literary studies. However, criticism has increased over time. This is why Clyde Kluckhohn (1942: 54) writes in his influential essay: “The whole question of the Primacy of ceremony and Mythology is as meaningless as all questions of the hen or the egg form”, a quote that also inspired the title of this article . Kluckhohn pointed out that myths often appear in connection with rituals, but just as often they do not. Rites and myths can stand in the most varied of relationships to one another, and can also arise in total independence from one another. A myth can contain motifs from other myths; these can be transferred between different cult contexts (Bremmer 1998: 74). Many other critics followed who pointed to errors and misunderstandings in myth and ritual literature and thus shook its foundations. E.g. Kirk (1974: 31-37) comes to the conclusion, based on the Greek material, that the vast majority of Greek myths arose without any special relation to rituals (1974: 253). The mytho-ritualistic interpretation of the Akītu festival was also decidedly rejected (von Soden 1955; Black1981).

From today's point of view, the seasonal scheme of parallel mythical and ritual death and resurrection is considered outdated (Smith 1982: 91; Versnel 1990: 44). The works of the myth ritualists have themselves become myths and are particularly interesting from a research historical perspective: "The Study of Ritual arose in an age of Unbounded Confidence in its ability to explain everything fully and scientifically and the construction of Ritual as a category is part of this worldview "(Bell 1997: 21). However, Frazer's great narrative of ritual drama - battle, death, and resurrection - still enjoys popularity. One good reason to deal with Frazer's ritual drama here is above all that this concept shapes the Hittite literature on the Illuyanka text to this day.

3. Volkert Haas undertakes a decidedly Frazerian interpretation of the Illuyanka story, who sees Ḫupašiya as a “kind of priest and year king” who, after a hieros gamos with the goddess, “from a priestess of the Inar (a) to a limited, perhaps even annual, rule cycle would have been killed ”(Haas1982: 45f.). The characterization of the text in its Hittite literary history also has Frazerian roots (Haas 2006: 97): “With the Illuyanka text, there is a seasonal myth in which the order and forces of the cosmos are renewed in the cultic reconstruction of prehistoric events. The myth has been handed down in two versions. At the end of the agricultural year in the autumn after the harvest, the Hittite python Illuyanka, the personification of winter, defeats the weather god Tarhunta, who embodies the forces of spring and who has now ceased to function and is in the power of the Illuyanka during the winter months. At the beginning of spring, with the awakening of the forces of growth, a second battle follows, in which the weather god defeats the Illuyanka with the help of his son or the human Ḫupašiya. The myth that is part of the Old Hittite New Year ritual ends with the etiology of sacred royalty. He was probably also represented by miming. ”- The elements of the Frazerian story cannot be overlooked: ritual drama of primeval times, renewal of the cosmos, order and chaos, revitalization of the forces of nature, the close connection to royalty and the performance in ritual. Some elements of this interpretation have meanwhile been strongly questioned, such as the suggestion to view Ḫupašiya as the king of the year or the cohabitation with Inara as hieros gamos (Hoffner 1998: 11). The identification of the Purulli festival as the Old Ethite New Year festival could not establish itself either (CHD P, 392b; Taracha 2009: 136). Other “mythos-ritualistic” elements are still the state of research.

3.1 This includes embedding the Illuyanka myth in the Purulli festival. In a fundamental essay on Hittite mythology, Hans G. Güterbock set himself the research task of tracing the origins of the various myths and their ways of transmission (Güterbock 1961: 143). "In doing so we immediately make an observation concerning the literary form in which mythological tales have been handed down: only the myths of foreign origin were written as real literary compositions - we may call them epics - whereas those of local Anatolian origin were committed to writing only in connection with rituals. "

This distinction between local mythological material embedded in a ritual context and “more literary”, imported mythological narratives of “foreign” origin has since established itself in Hittitology (most recently Lorenz / Rieken 2010). For research in this context, the Illuyanka text represents the prime example of the embedding of myth in the Anatolian cult. As Güterbock (1961: 150f.) Notes: “The text states expressly that the story was recited at the purulli festival of the Storm-god, one of the great yearly cult ceremonies ”. This assessment, too, has practically established itself in Hittitology and has a major impact on the religious-historical interpretation of the two Illuyanka stories.

There is far less agreement on the question of whether the myths in the festival were also represented by facial expressions, as Gaster suspected at the time (1950). In his review, Goetze was skeptical about this. The idea came back to life with Pecchioli Daddi's proposal (1987: 361-379; 2010: 261; but see Taracha 2009: 136) to identify the festival ritual for the deity Tetešḫabi (CTH 738) as part of the Purulli festival. She observes (Pecchioli Daddi 1987: 378) that the “daughter of the poor man” functions in the cult of the Teteš “abi, a figure who also plays a role in the second Illuyanka story and leads to the assumption that the myth is in the cult facial expressions (Haas 1988: 286). In addition, the connections between myth and ritual in the Illuyanka text are varied and complex. The Illuyanka stories were recorded on a board along with "ritual descriptions" which may, but not necessarily, represent parts of the Purulli festival. In addition, the first Illuyanka story also provides the aetiology for the Purulli festival celebrated in spring (Goetze 1952: 99; Neu 1990: 103; Klinger 2007: 72).

3.2 The Illuyanka stories are often interpreted as seasonal myths which symbolically represent the regeneration of nature, if not even magically bring it about. According to this interpretation, the defeat of the weather god, who is the lord of rain, endangers nature and agriculture (Hoffner 2007: 124). The eventual victory of the weather god symbolizes the revival of the vegetation in spring (Schwemer 2008: 24). Illuyanka's role is interpreted differently as the personification of winter (Neu 1990: 103; Haas 2006: 97), the Kaškäer (Gonnet 1987: 93-95) or, in my opinion, true as the master of underground water (Hoffner 2007: 124).

3.3 A close relationship between the narratives and the Hittite kingdom is postulated. "The mythic story about the dragon Illuyanka could be interpreted as an aetiological legitimation of the invention of kingship ... very secure are the close ties between the Hittite kings and the festival respectively the place where the mythological drama is located - namely the city of Nerik "(Klinger 2009: 99). The close connection to royalty is primarily based on the identification of

Ḫupašiya as an archaic, mythological king as well as on the role of the goddess Inara as the protective deity of Ḫattuša with close connections to the Hittite kingdom. But can the Illuyanka text meet all of these expectations?

4. The text (CTH 321) has survived in eight or nine Young Hittite copies - the affiliation of duplicate J (KUB 36.53) in Košak's Concordance has meanwhile been disputed - but the text contains linguistic archaisms that could refer to an older model. Hoffner (2007: 122) notes the small number of archaisms which for Klinger (2009: 100) show “the characteristic features of a moderately modernized text typical of the process of copying an older tablet”.

The text itself is introduced as the speech of Kella, the GUDU priest of the weather god of Nerik. The GUDU priest was part of the basic equipment of Hittite temples and was mainly anchored in the northern and central Anatolian, Hittite-Hittite cult tradition. He served in traditional Anatolian cult centers such as Nerik, Zipplanda or Arinna and was primarily active as an incantation priest and as a reciter in festive events (most recently Taggar-Cohen 2006: 229-278; Taracha 2009: 66). As the report of a GUDU priest, however, the Illuyanka text is quite singular. In reality, the text is unique in itself, a property that unfortunately went relatively uncommented in research. In contrast to other mythological texts of Anatolian tradition, the Illuyanka text does not represent a mūgawar "invocation" and did not serve to appease and bring about disappeared deities (Lepši 2009: 23). The text is not a festive ritual text and does not contain any magical practices (but now see Lorenz / Rieken 2010: 219). I will come back to the genre definition of the text, but first we will deal with the question of how myth and ritual are embedded.

The text is presented in the words of Kella (KBo 3.7 i 1-11 with duplicate KBo 12.83): [U]MMA mKell[a LÚGUDU12] ŠA d10 URUNerik nepišaš dI[ŠKUR-ḫ]u-[n]a? purulliyaš uttar nu mān kiššan taranzi utne=wa māu šešdu nu=wa utnē paḫšanuwan ēšdu nu mān māi šešzi nu EZEN4 purulliyaš iyanzi mān dIŠKUR-aš MUŠIlluyankašš=a INA URUKiškilušša arga(-)tiēr nu=za MUŠIlluyankaš dIŠKUR-an taraḫta

As follows Kell [a, the GUDU12 priest of the] weather god of Nerik: This (is) the word / matter of the purulli [...] of the weather god of heaven. When one says in this way: “Let the land prosper and multiply! - The land should be protected! ”And as soon as / so that it flourishes and multiplies, the purulli festival is celebrated. When the weather god and the snake fought in Kiškilušša, the snake defeated the weather god.

The rest of the story should be known. The weather god begs all gods for help, the goddess Inara prepares a festival and brings Ḫupašiya to help. Ḫupašiya shows himself to be helpful, but demands in return to sleep with the goddess.

The snake and its children are lured out of their hole in the ground; they eat and drink too much; The story, however, follows Inara, the actual heroine of the story (Pecchioli Daddi / Polvani 1990: 42), who builds a house for herself on a rock in the country of Tarukka and lets Ḫupašiya quarter there on the condition that he never looks out the window . But the relationship does not last longer than 20 days, because aupašiya does what he is not allowed to do. It is unclear whether Inara Ḫupašiya ultimately kills, but it is often suspected. For our question, the last paragraph in history is of particular interest (KBo 3.7 ii 15'-20'):

Inaraš INA URUKiškil[ušša wit] É-ŠU ḫunḫuwanašš[=a ÍD ANA] QATI LUGAL mān dāi[š] ḫa[nt]ezziyan purull[iyan] kuit iyaueni Ù QAT [LUGAL É-ir] dInaraš ḫunḫuwanašš=a ÍD […]

Inara [came] to Kiškil [ušša]. And when she put her house and [the river] of underground water [in] the hand of the king [...] - that's why / since then we celebrate the first purull [i] festival - and the hand [of the The king is said to be the house] of the Inara and the [river] of the underground water [...] So much for the first and longer mythical story. However, it cannot be overlooked that nowhere does the text suggest that the snake narrative is recited in the Purulli festival itself, as is so often assumed. At the beginning (lines 4-8), Kella explains to his addressees what Purulli actually means: A spring festival that is celebrated as soon as the land flourishes and multiplies (with Hoffner 2007: 131) or so that it flourishes and multiplies, as it did recently Melchert (in press), who revived Stefanini's suggestion (Pecchioli Daddi / Polvani 1990: 50) that it should be read here as a final conjugation, exceptionally and depending on the context.

The cited speech "from the cult event" is clearly limited to the short blessing. Immediately afterwards, Kella begins to tell the first snake story. As the end of the story (lines 15-20) makes clear, with his first myth, Kella provides an etiology for what he believes was the first / original Purulli festival. The addressees of this speech are not the festival participants in Nerik / Kiškilušša, but the recipients of the text in Ḫattuša, who are informed by Kella about the meaning of the festival and its history. The widespread assumption that the myth was presented at the Purulli festival itself cannot be confirmed in the Illuyanka text itself.

The brevity and the unadorned style of the narrative - epithets are missing e.g. completely - speak against the assumption that the story, at least in this form, was ever presented in a festive manner (Lepši 2009: 23). Can the presumption of recitation be explained as a projection of myth and ritual theory, originating in analogy to the Babylonian Akītu festival? Kiškilušša, however, is far from Babylon in many ways. If the Illuyanka myth was not recited during cult events, as is so often assumed, the assumption that the story symbolized the regeneration of the forces of nature, even magically and creatively caused it, becomes all the more improbable. The substance of the story itself speaks against this assumption; Hoffner (2007: 129) rightly remarks: "Unlike the so-called Disappearing Deity Myths the text does not elaborate the natural catastrophes that must have followed from the Storm-god’s disablement." Nor does he describe the healing states afterwards. The narrator's interest is obviously elsewhere. Kella only wants to explain how it came about that Inara placed her house and the river of underground water in the hands of the king (KBo 3.7 ii 15-19), an event that founded the first Purulli festival for him. As Gary Beckman (1982: 24) rightly remarked, the handover is the etiology for a royal cult in Kiškilušša, a scarcely occupied village not far from Tarukka, which, however, claims to be the site of a large one primeval struggle, the traces of which could still be seen in cultural legacies (the house on a rock in the Tarukka country) and in local, extraordinary natural phenomena (the flow of underground water) (Hoffner 2007: 126-127). Only the victory over the snake made the handover by Inara possible, who in turn founded the first / original Purulli festival for the weather god of the sky (KBo 3.7 i 2).

The Purulli festival has, as is well known, archaic, northern and central Anatolian roots and was celebrated in spring in several localities for several deities (see CHD P: 392a for the evidence). As is well known, spring festivals were an integral part of the cult in countless Anatolian towns. With his aetiology of the Purulli festival in Kiškilušša, Kella tries to “sell” the importance of the royal cult foundation in Kiškilušša, and he is certainly interested in the fact that this cult foundation will continue to exist in Kiškilušša. Thus a rather profane reading suggests itself for the last, very fragmentary sentence of the first story (KBo 3.7 ii 19'-20 '): “and the hand [of the king shall be the house] of the Inara and the [river] of the underground water [hold?] ”(additions from Beckman 1982: 19). This interpretation is supported by the second mention of the king at the end of the Illuyanka text (KBo 3.7 iv 24'-26 ’with duplicate KUB 17.6 iv 20-21). There is talk of a royal foundation, which regulates the supply of the three deities - Zaliyanu, Zašḫapuna and Tazzuwašši - or their priests in Tanipiya. As the etiology for this foundation in Tanipiya, which is described in detail, Kella tells of the throwing ceremony, which decides on the seat and hierarchy of the gods and makes it necessary to care for Zaliyanu and his companions in Tanipiya. This foundation is also a local affair, as its relatively modest size suggests. The parallel between the two cases cannot be overlooked. In both of them it is up to Kella to explain the importance of local cult institutions. This local dimension of the first Illuyanka story may in my opinion not be overlooked. The historian Paul Veyne (1987: 28) writes about the Greek mythographer Pausanias, albeit a bit pointedly: “If you read Pausanias, you understand what mythology was: the most insignificant spot that our scholar describes has its legend, fitting to a natural or cultural attraction of the place. ”With the elimination of the mytho-ritualistic interpretation scheme, the often suspected close relationship with the Hittite kingship began to falter. Compared to most of the Hittite texts that refer to the cult, the king plays an astonishingly minor role in the Illuyanka text. In the passages we have received, it is only mentioned twice in the entire text, both times in connection with cult foundations. A comparison to the numerous invocations and blessings embedded in the Anatolian cult, such as IBoT 1.30, according to which the gods gave the whole land to the king to administer, can only relativize the theological significance of Inara's gift to the king, which "only" consisted of her house and the river of underground water in Kišškiluša. But the thesis that the Ḫupašiya story is the aetiology of the Hittite kingship can, in my opinion, also be valid. not convince. The story itself offers no clue

points for any connection between Ḫupašiya and the king, and as far as I know, the entire Hittite tradition provides just as few arguments that a Hittite audience viewed Ḫupašiya as the original king or associated him with the king in any other way.

5. The question now remains, however, as to what connects the mythical stories with the other text sections, the so-called ritual descriptions. Immediately after the first snake narrative there follows a text passage, unfortunately only fragmentarily preserved, which is usually considered a ritual description in secondary literature and relates to Mount Zaliyanu and the city of Nerik (KBo 3.7 ii 21'-25 '): The mountain Zaliyanu (is ) the first [ranked] among all. When it has rained in Nerik, the herald brings thick bread from Nerik. And he asked for rain from Mount Za [liyan] u. After a large gap, we are already in the middle of the second mythical story (KBo 34.33 + KUB 12.66 iii 1’-10 ’; KBo 3.7 iii 1’-33’ brings the story to an end). The second snake story is structurally very similar to the first - with the son of the weather god in the role of Ḫupašiya - and also shows the weather god in a negative light. He sacrifices his son for the "bridegroom price" and his own salvation. However, geographical information is missing here, except that this time the snake is connected to the sea. The function of this narrative is, however, not apparent, nor is Kella's motivation to report it.

Immediately afterwards follows the introduction of a new speech by Kella (KBo 3.7 iii34’f.), Which probably introduces the new topic - the procession of the gods to Nerik. After another gap, the delivery is better, but the content all the more puzzling (KBo 34.33 + KUB 12.66 iv 1'-18 ’; with KBo 3.7 iv 1’-17’ and KUB 17.6 iv 1-14):

[And] before / for the GUDU priest they made the [first] gods the [last], and meanwhile they made the last gods the first. The Zaliyanu's cultivation (is) great. But Zalinui's wife, Zašḫapuna, (cultivation) is greater than the weather god of Nerik. As follows the gods to the GUDU priest Taḫpurili: “When we go to Nerik (in KBo 3.7 iv 5: to the weather god of Nerik), where do we sit down? Taḫpurili, the GUDU priest: “When you sit on the diorite / basalt throne, the GUDU priests will cast the lot. The GUDU priest holding Zaliyanu - a diorite / basalt throne stands over the spring - he will sit there. And all the gods arrive and they cast the lot and of all gods Zašḫapuna of Kaštama is the greatest.

This scene is also about the mountain god Zaliyanu (Taracha 2009: 44f., 104). His wife Zašḫapuna von Kaštama, who played a very important role in the cult of Nerik and the surrounding area (Haas 1994: 598; Taracha 2009: 44, 104), and his lover Tazzuwašši are also mentioned. Here, too, as in the first section on Zaliyanu, the question of the hierarchy of the gods is concerned, which was reversed at the beginning. This text passage is also characterized in secondary literature as a description of rituals. However, as Maria Lepši (2009: 21) rightly points out, the gods are involved in a dialogue with the GUDU priest and are informed by Taḫpurili of the ceremony of throwing away (Taggar-Cohen 2002) - elements that are discussed in Genuine ritual descriptions are rarely to be expected. There is presumably another mythological tale that tells of a ceremony involving Zaliyanu, Zašḫapuna and Tazzuwašši, which restores the true hierarchy of the gods and thus illustrates their great importance in the cult of Nerik. Thus, Kella also provides the justification for the subsequent cult foundation in Tanipiya.

After the detailed and exact presentation of the royal foundation in Tanipiya for the supply of the three deities or their priests, Kella asserts the truth of his report. The text comes to an end. However, we return to our opening question. How do the mythical narratives correspond to the “ritual” passages in which they are embedded? On closer inspection, the answer is sobering - they probably don't, not least because, at least in part, they are not genuine fixed descriptions. The suspicion arises that we are actually dealing with a text compilation (as already Taracha 2009: 137 note 803) that combines different excerpts from different "reports" of the Kella, or text sections with different content: The Etiology of Purulli -Festes in Kiškilušša, the second Illuyanka story, the function of which unfortunately can no longer be reconstructed, and another story about Zaliyanu and his companions as the etiology for the foundation in Tanipiya.

This interpretation is also supported by the new introduction to Kella's speech after the second Illuyanka story and the fact that the colophon only speaks of Kella's words and no longer of the Purulli festival as in Incipit. The matter of the Purulli festival was possibly only a topic in the first part of the text. However, the different sections of text have a lot in common. First and foremost, the water, an element that flows through the entire text like a red thread in many facets (rain, subterranean flood, the sea, springs). Pecchioli Daddi / Polvani (1990: 47-48) offer an ingenious explanation for the outstanding role that Zaliyanu, the rain giver, and his two companions in life, Zaš Tapuna and Tazzuwašši, who are also deified as sources (Haas1994: 446) with the Water connected, enjoy in the text. The ritual parts celebrate this troika, while the actual lord of the rain and head of the pantheon, the weather god, was temporarily incapacitated by Illuyanka. However, we are dealing here with two generations of weather gods: In both stories Illuyanka fights against the passive weather god of the sky, while Zaliyanu, Zašḫapuna and Tazzuwašši dispute the hierarchy of his dynamic son, the weather god of Nerik. The two weather gods are also differentiated, with one exception (KBo 3.7 iv 5 ’), by their sumerograms: the weather god of the sky is written as dIŠKUR, his son from Nerik with d10. Instead of myths embedded in descriptions of rituals, we are dealing with narratives on two different mythological levels, which, however, have a similar function. As we have seen, all parts of the text deal with hierarchies. At the end of the first Illuyanka story, Kella explains why the first / original Purulli festival was celebrated, then he notices the high ranking of the Zaliyanu, and later he also deals with the hierarchy of the gods, reaffirming the importance of Zaliyanu and Zašḫapuna24 through the story about throwing away and thus establishes the royal cult foundation in Tanipiya. It appears that this compilation of texts tries to make religious claims. This probably did not happen within the framework of the Great Empire's cult organization - the obvious option, which, however, is probably ruled out because of the archaisms of the text. But the long history of the city of Nerik certainly also offered other contexts for the composition / compilation of a text that I can only describe as a “mythological cult inventory” (for cult inventories see Hazenbos 2003). It is almost certain, however, that this compilation owes its popularity - evidenced by eight or nine text copies - to the interest in Nerik during the reign of Hattusili "III." (Hoffner 2007: 122). But maybe it was also the fascination, then as now, that the stories of dragons and their conquerors radiate.

0 notes

Text

Also i was never a bo burnam kid back in the day so im watching his first two Netflix specials before i watch the new one and….. how has this mans career survived

#not that i dont find him funny (sometimes) or entertaining or whatever but like?#idk how to word stuff bear with me#in both be makes jokes involving 1) the n word in one a robotic voice and the other ‘tricks’ the audience into saying it#2) rape one in a song supposed to be from the perspective of god and i dont rmbr the other time but it def was i think#and 3) the word fag and then says how hes a cis straight white guy#i dont Care that much im just genuinely confused and surprised lol that this guy hasnt been#~CANCELLED~#cuz he so quirky mentally ill relatableeee ig#maybe hes apologized idk no tea no shade

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

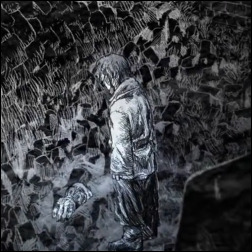

In the Bleak Mid-winter Ch. 2

LAST HERALD-MAGE FANFIC

Fix-it…ish. canon mm

Young Stefen, living on the streets, found out someone was looking for him and decided to lay low, avoiding the mysterious stranger in red, so he’s never taken to Haven by Bard Lynnell. It was an unfortunate decision, but in spite of it, he and Van do meet up, just later, and under less kind circumstances. Basically a redo on the ending. ~55k words Finished.

Prologue | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5| Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 | Chapter 8 | Chapter 9 | Visit my master list

Word Count: ~4180

Rating: Mature for, sorry, lots of bad stuff, rape, sexual abuse, child abuse. Canon was pretty dark, especially what I was redoing here, so’s this.

On AO3.

Chapter Synopsis: Stefen’s perspective on the stranger from the south.

Fucking hell, Stefen hated winter.

The little guard post was one of the nicer places he’d weathered the bitter northern storms at least, but he was so damned tired of the chill that penetrated right down to the bone every time he stepped outside, no matter how warmly he was dressed. The gray skies, the white everything else, the whole grim, drab, lifeless world, he was so sick of it all.

The cheer with which the soldiers stationed at the post greeted him was something like a balm to his soul though. He couldn’t deny he liked the appreciation, the warmth, the food, hells, the bed, when he’d been more than willing to take a bedroll by the fire and be grateful for that much kindness.

He’d played for fancier audiences but rarely for one that was so admiring.

Nothing good lasts though, and the end to his peaceful interlude came with a rush of cuttingly cold wind, given entrance through an open door in the snow room. He couldn’t see it, but he felt it, though he gave it no mind until he saw who’d come in with the captain.

It was Master Dark himself.

It was a good thing he was between songs because not for love of gold or applause or life itself could have kept singing without faltering when he recognized that face; there was simply no mistaking it.

And yet…and yet.

Master Dark was vain and terrifyingly powerful, he’d never looked so ragged or so careworn. His hair was the unrelieved black of an obsidian blade; it had no streaks of silver. He’d never moved so stiffly and so painfully; his head had never bowed, weighed down with troubles; he’d never looked so…human. So human and so tired.

And he’d certainly never, never, never been caught in so much as a scrap of white, though he often wore something that looked remarkably like the man’s gear, if it were dipped in ink.

Not Master Dark then, but his mirror somehow, and the Whites gave him away almost certainly as the person Stefen had been sent out to intercept: Herald-Mage Vanyel Ashkevron, of Haven, and of Forst Reach. Demonsbane. Shadow-Stalker. A number of other epithets, some flattering, some not, depending on which side of the Valdemar/Karsite border the story came from.

Stefen had expected him to be…bigger. Broader and brawnier, the way a hero ought to be. It was stupid. He’d come up with enough lyrics of his own, he should have known better than to pin his expectations on songs, but he had not expected a man hardly larger than himself, Master Dark’s pale shadow, silver in his hair and the scruff of a patchy beard on his cheeks and a weary glaze over his startlingly silver eyes.

He didn’t know what to make of it, the Herald’s similarity to Master Dark.

His audience was waiting and he pretended not to watch the Herald cross the room while he swept them into the next song.

It did occur to him that this might be easier with the Herald’s uncanny resemblance to Master Dark. As little love as Stefen had for his Master it should weigh far less on his conscience to do what he had to do to someone who looked so like him.

Except the longer he watched the man, setting on his meager meal with a forced care that spoke of pride and self-control—two vastly overrated qualities in Stefen’s opinion—the less he reminded him of Master Dark at all.

It was that weariness that tugged unexpectedly at Stefen’s heartstrings. A hero was supposed to be brash and loud and full of life and energy, not quiet and alone and reed-thin and heavy-eyed.

He tried to put a little cheer into his song, a little extra lift to the words and the tempo.

He kept his eyes moving, his banter and his attention inclusive, and the soldiers gathered around him basked in the warmth with which he infused his music, but from Herald Vanyel there was no visible reaction.

He switched gears: a man in pain couldn’t be so easily cheered just by a happy song, pain stood between him and any comforts the world might offer, so Stefen put a bit of his pain-blocking into the next song instead, the skill he’d trained at old Berte’s knee so long ago, curse her hide and rest her soul.

There were surprised sighs from several in his audience, a sudden relief of aches that never fully eased in a land where the cold cut so sharp, but still Herald Vanyel didn’t look over from his food and his ale.

Fine. Perhaps the Herald had the worst tin ear that Stefen had ever come across, and was half-deaf from too many blows taken to the head in his many skirmishes at the Karsite border.

But there were tunes that bypassed the ears and aimed directly at…regions south, he thought with a sudden, wicked grin. He’d been told the Herald was shaych, and Master Dark’s envoy had been very clear that Stefen was to act on that knowledge.

A love song then, for a certain definition of love. He let his hands caress his gittern in ways that were positively indecent, while he drew resonant, plaintive notes from the tired old second-hand instrument, and put the full force of longing into his words: desire, hunger, raw, inelegant lust, until the soldiers were shifting around in discomfort for any number of reasons—most of the men were not shaych and that poor, confused woman over there was—even as he held them with his song.

And Herald-Mage Vanyel Ashkevron yawned.

He caught the Herald’s gaze as the man’s mouth snapped shut and for one moment the Herald’s eyes seemed to widen with recognition of something—that utterly failed to hold his attention as he tucked his head back down to his bowl with all the wit and interest of a cow at pasture.

Godsbedamned.

He managed to keep his sulking in hand for two more songs, milder, simpler fare than the last, no need to leave his audience in that state, especially when the focus of his efforts remained oblivious.

He gave them one encore, a rousing if tongue-in-cheek call to battle that had preceded many a bloody day, Stefen would be willing to bet, but it had them clapping and stomping and left them grinning nonetheless.

He was tempted to keep playing, but Master Dark wasn’t a patient man and the sooner Stefen began, the sooner he’d be done.

A stop off at the fire for bread and a bowl for him, another at the tap for two ales, a moment away from watching eyes to dump in one of the packets of powder he’d been given, and he was ready to face this Herald Vanyel—his name confirmed in an awed whisper by the female soldier keeping an eye on the ale—who turned his nose up at the best of Stefen’s skills.

He longed to doctor up his own ale with a little of the flask tucked tight in a hidden breast pocket but he needed a clear head for this.

He examined him as he approached, the face so like Master Dark, but different. Older and younger at once, and altogether more real. Stefen had long suspected the Master did something to shape his appearance as it was; he’d seen him do it to others that fell under his hand, youth and beauty traded for loyalty, less

‘pleasant’ things for those who stood against him. But even the faces he’d changed to be beautiful never looked entirely right to Stefen, any more than Master Dark’s own face did. That human quality the Herald had that Master Dark didn’t share seemed to make all the difference.

“You look like a man who could use another,” Stefen said, artfully droll, a deliberate sparkle in his eye, a teasing grin at his lips. He set the drink down in front of the other man and sat across from him at a table hardly big enough for two, though the body of the barrel that made up the base of the table kept them well apart.

Even his flirting seemed wasted: the Herald looked up at him, then cast a vaguely curious glance at the stool across the room where he’d been sitting all night, as though he hadn’t noticed the music had stopped and expected to see Stefen’s twin still sitting there and playing.

Stefen wasn’t a vain man—or, all right, maybe he was—but he was a damned good musician. His talent was the only mercy the gods had ever granted him and he traded on it shamelessly to keep himself alive and out of trouble when he could.

“You weren’t paying attention to my music at all. Was my playing so off tonight?” he asked, leaning a bit closer, conspiratorial, putting a hint of playful pouting into his voice but giving the Herald an out, a chance to flatter, a chance to play the game.

“I’m not a fan,” the Herald answered, his words too deadpan to be teasing and Stefan stilled for a moment, feeling as though the Herald had just pulled the fancy knife from its sheath at his trim-to-the-point-of-being-skinny waist and shoved it into Stefen’s gut. He didn’t think he breathed, and a silence stretched painfully between them.

He saw it the instant the weary Herald realized what he’d said, and something like panic or like shame flashed across that unfairly handsome face, raising a slight flush to his cheeks.

This cruel, awkward man, was the Vanyel of legend?

“—of music,” the man added stupidly. But then his whole demeanor softened and perhaps Stefen could see a little of it. “I don’t care for music,” he clarified, and the embarrassment he showed could have been at his words, or his strange aversion, or pure artifice, Stefen had no idea. “I had dreams of being a Bard myself once. Some dreams die hard and leave a…bitter taste.”

He seemed sincerely downcast, his voice heavy with old regrets.

Stefen wasn’t entirely mollified but his end goal wasn’t to get in the man’s breeches so what did it matter if he had nothing of interest to offer the Herald at all, not even his music, the heart and soul of everything he was, the only part of his misbegotten life that had any objective value. He shoved a spoonful of soup into his mouth before he could say something stupid. Then another.

“Looks like you did all right. Most’d think those Whites of yours are worth more than a pretty song, Herald,” he said, after he’d sufficiently shoved down the lump in his throat with soup.

He had no illusions. It wasn’t worth much, his singing, especially not when compared to a man who could call lightning and flame from the empty air or stand against the literal demons of hell and send them fleeing back to their master with little more than an upraised hand. But no one would ever notice a nobleman in his peacock finery if there weren’t beggar-boys like Stefen to compare him to, so that was fine, he knew his place.

The Herald had been drinking the drugged ale since not long after Stefen had sat, that was all that mattered.

As though catching Stefen’s thought though, the Herald suddenly put his mug down decisively and pushed himself away from the table, making Stefen look up in sudden alarm. He wasn’t sure if the Herald had drunk enough of it for the powder to do what it was supposed to. If it didn’t take him out as Master Dark’s envoy had promised, but the Herald caught on to what he’d been attempting—

But the man didn’t make it all the way to his feet before he was weaving as though he stood on the deck of a pitching ship, and grabbed for the table to steady himself.

“Whoa—” Stefen exhaled deeply and reached for him, helping him back down to his chair. “You look worn out. Don’t be so quick to move around, yeah? Another drink to steady your head?”

But the Herald closed his eyes with the deep concentration of a drunk fighting back nausea and Stefen struggled against another wave of panic at the thought of the Herald vomiting up the powder and coming back to himself and denouncing him.

It was bound to be worth his head to be caught trying to drug a Herald. Master Dark would surely see him dead if he fell into Valdemar’s hands, even if the Heralds themselves were inclined to mercy, which he doubted.

Fuck them both, this had to work.

The Herald’s eyes were foggy and unfocused when he opened them, but he smiled weakly and Stefen had to shrug away the image of this Herald-hero of Valdemar as a lamb, toddling up to the butcher with a welcoming bleat, too innocent to know its killer could greet it with a smile.

“I’m fine. I’ve just been on the road too long. I just need a good bed to fall into.”

Guilt and fear leaving Stefen himself near sick, he leaned around his side of the table to rest his hand on the other man’s thigh. Had to make it look good for anyone watching, even if he was nothing to the Herald himself.

“Now that’s a smart idea. But the beds up here are so cold…when you’re alone,” he murmured, his touch and his words completely indelicate, but his expression as coy as he could manage. The Herald jumped and tried to hide the way he suddenly jerked away by grasping for the mug and downing the rest of his ale.

Stefen tried not to wince.

The little lamb hadn’t caught sight of the butcher’s knife yet, but it wouldn’t be long.

He pulled back to his own side of the table to watch—and to wait.

The Herald shuddered once, subtly, and grabbed at the table with visibly feeble fingers, and then something about him changed, a sudden slackness, in spite of the tension in him.

Stefen pressed a hand over one of the Herald’s and leaned back into him, nuzzling his ear like a teasing lover, trying to be cold, trying to be practical. “Too good for the likes of me, hmm? That’s fine, fancier men than you have said the same, but fancier men than you have said otherwise, too. A man can’t win ‘em all, can he?” he said, not sure if the Herald could even still hear his rationalizing.

He chuckled heartily, just in case someone came close enough to investigate, as though in response to something the Herald could no longer say, and wrapped his arms around him, pulling one of the Herald’s arms across his shoulder and wrapping one of his own arms around the Herald’s waist, the better to subtly heave him to his feet.

He wanted to hurry away, not just because the other man was surprisingly heavy for his slim and wiry build and his near to dead weight was no easy burden on Stefen’s hardly impressive strength, but because this was the most dangerous part of the plan.

He was a dashing young blade in the arms of an intriguing older lover, a lover too far in his cups, perhaps, but no less interested for it and he aped laughter at flirty words whispered in his ear from where the Herald’s heavy head was resting against his neck, hidden behind the veil of that too-long silver and black hair, grinning and murmuring pointless little things “back.”

Across the way he saw a few soldiers look up from their card game and take him in with a surprised lift of their brows. One smiled indulgently and another looked away in embarrassment and Stefen just kept walking the limp Herald towards the back hallway.

He reached the hallway and reeled in relief at his near success. To his right was the hall to the sleeping rooms, to his left the hall to a small storage room and door to the outside. He only had to slip the Herald out unnoticed, hand him off to Rendan’s man, who’d been lurking in the forest for the last week waiting for a sign from Stefen, then take care of the Companion, and he’d be home free. The Herald’s fate past that was no concern of his.

Of course it could never be that easy, not in Stefen’s god-cursed life.

A trio of soldiers came out of the sleeping rooms just then, and thinking quickly Stefen swung the Herald up against the wall. He caught the Herald’s hands and lifted them above his head, twining their fingers and pressed himself, full body against the other man, leaning up to cover his mouth in a kiss, hoping the slackness of his partner’s expression would be taken for bliss as that silken hair fell back around his face.

The soldiers fell into an embarrassed silence, because it was two men kissing or because it was anyone at all, out in the open, when such things were probably frowned on in their ranks, Stefen didn’t know or care.

He made a good show of it, trying to tamp down the certainty that what he did was tantamount to rape, with the Herald in the state he was in. He’d never even know—Stefen hoped—and it literally made the difference of life or death for Stefen himself.

He heard them murmuring to each other as they passed, even over his pounding heart.

Did you know the minstrel was shaych?

Gods, and the Herald?

What, you two couldn’t tell?

Well, I mean the minstrel, sure, but the Herald?

Their voices faded and Stefen pulled his lips from the unresponsive mouth, pressing his head instead for one moment against the other man’s shoulder. He inhaled deeply and shuddered. For all the things he’d done in his life, this was definitely in the running for the worst. Shite.

Practically a wreck of nerves, Stefen leaned the man gently into the roots of a tree on the edge of the forest. Another of Master Dark’s storms was raging and as long as he moved quickly his tracks would be covered by fresh snow long before anyone noticed that he and the Herald were missing.

He let out the trilling whistle that was to signal whoever Renden had left on watch, and tucked his bare hands against his sides, wishing he’d dared to stop for his cloak.

Otherwise alone, in the echoing silence of the dark, cold night, Stefen looked down at the Herald. Even in the shadows he was pale. Too pale? He’d worried that he might not have given the Herald enough and that the man would catch on to the trap; now he found himself worrying that he’d given the Herald too much and that he’d never wake again.

His spiraling fears were soon interrupted.

“Well, fancy that,” Rendan’s right hand, Tan, sneered, creeping from the shadows at the edge of the forest. “Against all odds, M’lord Guttersnipe caught him a Herald.”

“Just take him,” Stefen snapped. “And give him your cloak, I didn’t have a chance to grab his. Master Dark won’t like it if he freezes to death on the way back to Rendan’s.”

“That’s Lord Rendan to you, boyo, and you’ll watch your tongue with me or I’ll cut it out for you.”

“Lord” Rendan was no more than a robber baron who’d carved out a kingdom of cutthroats in a land no one else would have wanted. No one else until Master Dark had come anyway, and like all the other thieving rats of the northern forests, he was the Master’s man now.

“Just take him and keep him warm until I get back,” Stefen said again. “I still need to take care of the Companion.”