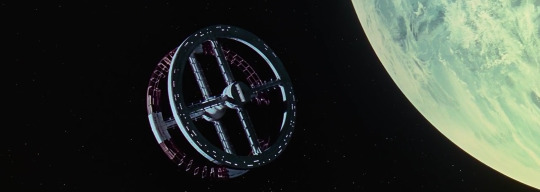

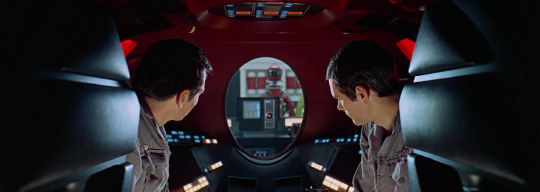

#2001 a space odyssey headers

Photo

2001: a space odyssey

#Stanley Kubrick#2001: a space odyssey#a space odyssey#header#headers#sci-fi#black header#black headers#keir dullea#david bowman#frank poole#hal 9000#movie#movie header#movie headers#gary lockwood#the ninth picture is actually from full metal jacket movie but anyway...

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

like or reblog

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

made by Gabe ♡

#color palettes#film color palettes#movie color palettes#color palettes headers#film color palettes headers#movie color palettes headers#headers#icons#quentin tarantino#quentin tarantino headers#pulp fiction headers#pulp fiction#stanley kubrick#stanley kubrick headers#2001: a space odyssey#2001 a space odyssey headers#lars von trier#lars von trier headers#melancholia#melancholia headers#wes anderson#wes anderson headers#mean girls#mean girls headers

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

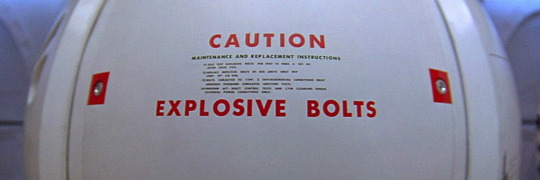

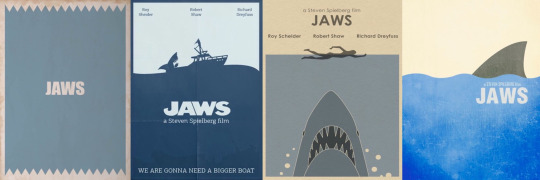

like or reblog if you save :)

#header#headers#the godfather#the shinning#forrest gump#jaws#e.t. the extra terrestrial#cast away#2001 a space odyssey#movie#cinema

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

adele layouts

like/reblog if you save

© gagalacrax

icons and headers are ours

follow us for more

#icons#adele icons#icons adele#adele heades#headers adele#headers#adele packs#packs adele#adele layouts#layouts adele#packs#layouts#twitter#icons with psd#random icons#girls icons#twitter icons#site model icons#random layouts#2001 a space odyssey#2001 a space odyssey headers#headers 2001 a space odyssey#stanley kubrick#headers movies

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let’s Talk About the Hello Neighbor Dropbox

Okay, so tinyBuild sent out two emails a few days ago that were both mainly about Hello Neighbor coming out this August and the Hot Topic dog tags. But one of them not only mentioned the new E3 build (one sentence about it. that’s it.), it also had a link to their Dropbox.

The Hello Neighbor press kit, as they put it. This thing is 100% different and better than that media kit they have on the Hello Neighbor website. I swear there are dozens of images we haven’t seen before on this sucker. I’ll leave some links to it towards the end of this post, but first I want to go through some of my favorites from it.

This seems to be a concept comic for the being of Alpha 2. My friend was horrified at the thought of the player killing that bird with the rock, but I quickly explained to her he was just scaring the crow into dropping the key. But I must say, it looks like this crow has seen some shit, man. And how many To Do List does one man need?

Most of the artwork in the Dropbox isn’t properly named, but obviously, this is the early artwork of the Neighbor’s bathroom. The place is an inhabitable mess, to say the least, but I really do love the fact this dude went out and bought himself two flipping boxes of rubber duckies.

Heeeeeeeeeeeeeeeey.

I sadly also found this overly detailed image of Neighbs that might curse your crops if you don’t send this post to ten your friends before midnight. Just sayin’.

This mannequin gives off a vibe that says she works nights at an 80s dinner trying to make enough money to pay off her student debt. One rainy night the Neighbor walks in ten minutes before closing. She sighs at the sight of having to put up with one more customer, does her arms in that “why me” pose as she holds that old rag, fakes a smile and says, “How may I help you, hon?”

What? It’s just me getting that vibe? Oh, okay. I’ll move on.

I’m pretty sure this a reference to a glitch in a Grand Theft Auto game.

He’ll get you when you’re sleeping

He claims that every day

He’ll find you no matter where you hid

So you better stay away

And finally, this one. When I first saw this I freaked the heck out. What does this mean? Who the heck’s Dave? Was there suppose to be writing on the other two boards? WHO THE FUCK IS DAVE???

But then I started telling my friend all about this and my questions only to find out this is a reference to a critically acclaimed movie called 2001: A Space Odyssey. The quote is from the AI in that movie, so yeah. Makes sense.

That is just SOME of the things I found cool in the Hello Neighbor Press Kit. There’s literally dozens of other stuff cool, basically-never-before-seen work there I highly recommend checking out. Click here to go to the Dropbox. Or click here to just check out my favorite folder from it that is literally named “random_art”.

And now, I will close this post with the images I’m going to use as my new header image and avatar:

#Hello Neighbor#dropbox#hello neighbor press kit#tinyBuild#vidoe games#indie game#i'm sorry the post is so long#i'm sorry this is so long#i hope you like it anyway

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Voices in AI – Episode 16: A Conversation with Robert J. Sawyer

Today’s leading minds talk AI with host Byron Reese

.voice-in-ai-byline-embed {

font-size: 1.4rem;

background: url(http://ift.tt/2g4q8sx) black;

background-position: center;

background-size: cover;

color: white;

padding: 1rem 1.5rem;

font-weight: 200;

text-transform: uppercase;

margin-bottom: 1.5rem;

}

.voice-in-ai-byline-embed span {

color: #FF6B00;

}

In this episode, Byron and Robert talk about human life extension, conscious computers, the future of jobs and more.

–

–

0:00

0:00

0:00

var go_alex_briefing = {

expanded: true,

get_vars: {},

twitter_player: false,

auto_play: false

};

(function( $ ) {

‘use strict’;

go_alex_briefing.init = function() {

this.build_get_vars();

if ( ‘undefined’ != typeof go_alex_briefing.get_vars[‘action’] ) {

this.twitter_player = ‘true’;

}

if ( ‘undefined’ != typeof go_alex_briefing.get_vars[‘auto_play’] ) {

this.auto_play = go_alex_briefing.get_vars[‘auto_play’];

}

if ( ‘true’ == this.twitter_player ) {

$( ‘#top-header’ ).remove();

}

var $amplitude_args = {

‘songs’: [{“name”:”Episode 16: A Conversation with Robert J. Sawyer”,”artist”:”Byron Reese”,”album”:”Voices in AI”,”url”:”https:\/\/voicesinai.s3.amazonaws.com\/2017-10-30-(01-00-58)-robert-j-sawyer.mp3″,”live”:false,”cover_art_url”:”https:\/\/voicesinai.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2017\/10\/voices-headshot-card-2-1.jpg”}],

‘default_album_art’: ‘http://ift.tt/2yEaCKF’

};

if ( ‘true’ == this.auto_play ) {

$amplitude_args.autoplay = true;

}

Amplitude.init( $amplitude_args );

this.watch_controls();

};

go_alex_briefing.watch_controls = function() {

$( ‘#small-player’ ).hover( function() {

$( ‘#small-player-middle-controls’ ).show();

$( ‘#small-player-middle-meta’ ).hide();

}, function() {

$( ‘#small-player-middle-controls’ ).hide();

$( ‘#small-player-middle-meta’ ).show();

});

$( ‘#top-header’ ).hover(function(){

$( ‘#top-header’ ).show();

$( ‘#small-player’ ).show();

}, function(){

});

$( ‘#small-player-toggle’ ).click(function(){

$( ‘.hidden-on-collapse’ ).show();

$( ‘.hidden-on-expanded’ ).hide();

/*

Is expanded

*/

go_alex_briefing.expanded = true;

});

$(‘#top-header-toggle’).click(function(){

$( ‘.hidden-on-collapse’ ).hide();

$( ‘.hidden-on-expanded’ ).show();

/*

Is collapsed

*/

go_alex_briefing.expanded = false;

});

// We’re hacking it a bit so it works the way we want

$( ‘#small-player-toggle’ ).click();

$( ‘#top-header-toggle’ ).hide();

};

go_alex_briefing.build_get_vars = function() {

if( document.location.toString().indexOf( ‘?’ ) !== -1 ) {

var query = document.location

.toString()

// get the query string

.replace(/^.*?\?/, ”)

// and remove any existing hash string (thanks, @vrijdenker)

.replace(/#.*$/, ”)

.split(‘&’);

for( var i=0, l=query.length; i<l; i++ ) {

var aux = decodeURIComponent( query[i] ).split( '=' );

this.get_vars[ aux[0] ] = aux[1];

}

}

};

$( function() {

go_alex_briefing.init();

});

})( jQuery );

.go-alexa-briefing-player {

margin-bottom: 3rem;

margin-right: 0;

float: none;

}

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#top-header {

width: 100%;

max-width: 1000px;

min-height: 50px;

}

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#top-large-album {

width: 100%;

max-width: 1000px;

height: auto;

margin-right: auto;

margin-left: auto;

z-index: 0;

margin-top: 50px;

}

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#top-large-album img#large-album-art {

width: 100%;

height: auto;

border-radius: 0;

}

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player {

margin-top: 38px;

width: 100%;

max-width: 1000px;

}

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player div#small-player-full-bottom-info {

width: 90%;

text-align: center;

}

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player div#small-player-full-bottom-info div#song-time-visualization-large {

width: 75%;

}

.go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player-full-bottom {

background-color: #f2f2f2;

border-bottom-left-radius: 5px;

border-bottom-right-radius: 5px;

height: 57px;

}

Voices in AI

Visit VoicesInAI.com to access the podcast, or subscribe now:

iTunes

Play

Stitcher

RSS

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed {

font-size: 1.4rem;

background: url(http://ift.tt/2g4q8sx) black;

background-position: center;

background-size: cover;

color: white;

padding: 1rem 1.5rem;

font-weight: 200;

text-transform: uppercase;

margin-bottom: 1.5rem;

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed:last-of-type {

margin-bottom: 0;

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed .logo {

margin-top: .25rem;

display: block;

background: url(http://ift.tt/2g3SzGL) center left no-repeat;

background-size: contain;

width: 100%;

padding-bottom: 30%;

text-indent: -9999rem;

margin-bottom: 1.5rem

}

@media (min-width: 960px) {

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed .logo {

width: 262px;

height: 90px;

float: left;

margin-right: 1.5rem;

margin-bottom: 0;

padding-bottom: 0;

}

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed a:link,

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed a:visited {

color: #FF6B00;

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back a:hover {

color: #ff4f00;

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links {

margin-left: 0 !important;

margin-right: 0 !important;

margin-bottom: 0.25rem;

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:link,

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:visited {

background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.77);

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:hover {

background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.63);

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links .stitcher .stitcher-logo {

display: inline;

width: auto;

fill: currentColor;

height: 1em;

margin-bottom: -.15em;

}

Byron Reese: This is voices in AI, brought to you by Gigaom. I’m Byron Reese. Our guest today is Robert Sawyer. Robert is a science fiction author, is both a Hugo and a Nebula winner. He’s the author of twenty-three books, many of which explore themes we talk about on this show. Robert, welcome to the show.

Tell me a little bit about your past, how you got into science fiction, and how you choose the themes that you write about?

Robert Sawyer: Well, I think apropos of this particular podcast, the most salient thing to mention is that when I was eight years old, 2001: A Space Odyssey was in theaters, and my father took me to see that film.

I happen to have been born in 1960, so the math was easy. I was obviously eight in ’68, but I would be 41 in 2001, and my dad, when he took me to see the film, was already older than that… which meant that before I was my dad’s age, talking computers [and] intelligent machines would be a part of my life. This was promised. It was in the title, 2001, and that really caught my imagination.

I had already been exposed to science fiction through Star Trek, which obviously premiered two years earlier, [in] ’66. But I was a little young to really absorb it. Heck, I may be a little young right now, at 57, to really absorb all that in 2001: A Space Odyssey. But it was definitely the visual world of science fiction, as opposed to the books… I came to them later.

But again, apropos of this podcast, the first real science fiction books I read… My dad packed me off to summer camp, and he got me two: one was just a space adventure, and the other was a collection of Isaac Asimov’s Robot Stories. Actually the second one [was] The Rest of the Robots, as it was titled in Britain, and I didn’t understand that title at all.

I thought it was about exhausted mechanical men having a nap—the rest of the robots—because I didn’t know there was an earlier volume when I first read it. But right from the very beginning, one of the things that fascinated me most was artificial intelligence, and my first novel, Golden Fleece, is very much my response to 2001… after having mulled it over from the time I was eight years old until the time my first novel came out.

I started writing it when I was twenty-eight, and it came out when I was thirty. So twenty years of mulling over, “What’s the psychology behind an artificial intelligence, HAL, actually deciding to commit murder?” So psychology of non-human beings, whether it’s aliens or AIs—and certainly the whole theme of artificial intelligence—has been right core in my work from the very beginning, and 2001 was definitely what sparked that.

Although many of your books are set in Canada, they are not all in the same fictional universe, correct?

That’s right, and I actually think… you know, I mentioned Isaac Asimov’s [writing] as one of my first exposures to science fiction, and of course still a man I enormously admire. I was lucky enough to meet him during his lifetime. But I think it was a fool’s errand that he spent a great deal of his creative energies, near the later part of his life, trying to fuse his foundation universe with his robot universe to come up with this master plan.

I think, a) it’s just ridiculous, it constrains you as writer; and b) it takes away the power of science fiction. Science fiction is a test bed for new ideas. It’s not about trying to predict the future. It’s about predicting a smorgasbord of possible futures. And if you get constrained into, “every work I did has to be coherent and consistent,” when it’s something I did ten, twenty, thirty, forty—in Asimov’s case, fifty or sixty years—in my past, that’s ridiculous. You’re not expanding the range of possibilities you’re exploring. You’re narrowing down instead of opening up.

So yeah, I have a trilogy about artificial intelligence: Wake, Watch, and Wonder. I have two other trilogies that are on different topics, but out of my twenty-three novels, the bulk of them are standalone, and in no way are meant to be thought of as being in a coherent, same universe. Each one is a fresh—that phrase I like—fresh test bed for a new idea.

That’s Robert Sawyer the author. What do you, Robert Sawyer the person, think the future is going to be like?

I don’t think there’s a distinction, in terms of my outlook. I’m an optimist. I’m known as an optimistic person, a techno-optimist, in that I do think, despite all the obvious downsides of technology—human-caused global climate change didn’t happen because of cow farts, it happened because of coal-burning machines, and so forth—despite that, I’m optimistic, very optimistic, generally as a person, and certainly most of my fiction…

Although my most recent book, my twenty-third, Quantum Night, is almost a deliberate step back, because there had been those that had said I’m almost Pollyanna-ish in my optimism, some have even said possibly naïve. And I don’t think I am. I think I rigorously interrogate the ideas in my fiction, and also in politics and day-to-day life. I’m a skeptic by nature, and I’m not easily swayed to think, “Oh, somebody solved all of our problems.”

Nonetheless, the arrow of progress, through both my personal history and the history of the planet, seems definitely to be pointing in a positive direction.

I’m an optimist as well, and the kind of arguments I get against that viewpoint, the first one invariably is, “Did you not read the paper this morning?”

Yeah.

People look around them, and they see that technology increases our ability to destroy faster than it increases our ability to create. That asymmetry is on the rise, meaning fewer and fewer people can cause more and more havoc; that the magnitude of the kinds of things that can happen due to technology—like genetically-engineered superbugs and what not—are both accessible and real. And when people give you series of that sort of view, what do you say?

Well you know, it’s funny that you should say that… I had to present those views just yesterday. I happen to be involved with developing a TV show here in Canada. I’m the head writer, and I was having a production meeting, and the producer was actually saying, “Well, you know, I don’t think that there is any way that we have to really worry about the planet being destroyed by a rogue operator.”

I said, “No, no, no, man, you have no idea the amount of destructive power that the arrow of history is clearly showing is devolving down into smaller and smaller hands.”

A thousand years ago, the best one person could do is probably kill one or two other people. A hundred years ago they could kill several people. Once we add machine guns, they could kill a whole bunch of people in the shopping mall. Then we found atomic bombs, and so forth, it was only nations we had to worry about, big nations.

And we saw clearly in the Cuban missile crisis, when it comes to big, essentially responsible nations—the USSR and the United States, responsible to their populations and also to their role on the world stage—they weren’t going to do it. It came so close, but Khrushchev and Kennedy backed away. Okay, we don’t have to worry about it.

Well, now rogue states, much smaller states, like North Korea, are pursuing atomic weapons. And before you know it, it’s going to be terrorist groups like the Taliban that will have atomic weapons, and it’s actually a terrifying thought.

If there’s a second theme that permeates my writing, besides my interest in artificial intelligence, it’s my interest in SETI, the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence. And one of the big conundrums… My friends who work at the SETI Institute, Seth Shostak and others, of course are also optimists. And they honestly think, in the defiance of any evidence whatsoever, that the universe actually is teeming with aliens, and they will respond, or at least be sending out—proactively and altruistically—messages for others to pick up.

Enrico Fermi asked, actually, way back in the days of the Manhattan Project—ironically: “Well if the universe is supposed to be teeming with aliens, where are they?” And the most likely response, given the plethora of exoplanets and the banality of the biology of life and so forth, is, “Well, they probably emerge at a steady pace, extra-terrestrial civilizations, and then, you know, they reach a point where they develop atomic weapons. Fifty years later they invent radio that’s the range for us, or fifty years earlier—1945 for atomic weapons, 1895 for radio. That’s half a century during which they can broadcast before they have the ability to destroy themselves.”

Do they survive five-hundred years, five-thousand years, you know, five-hundred-thousand years? All of that is the blink of an eye in terms of the fourteen-billion-year age of the universe. The chances of any two advanced civilizations that haven’t yet destroyed themselves with their own technology existing simultaneously, whatever that means in a relativistic universe, becomes almost nil. That’s a very good possible answer to Fermi, and bodes not well at all for our technological future.

Sagan said something like that. He said that his guess was civilizations had a hundred years after they got radio, to either destroy themselves, or overcome that tendency and go on to live on a timescale of billions of years.

Right, and, you know, when you talk about round numbers—and of course based on our particular orbit… the year is the orbital duration of the Earth—yeah, he’s probably right. It’s on the right order of magnitude. Clearly, we didn’t solve the problem by 1995. But by 2095, which is the same order magnitude, a century plus or minus, I think he’s right. If we don’t solve the problem by 2095, the bicentennial of radio, we’re doomed.

We have to deal with it, because it is within that range of time, a century or two after you develop radio, that you either have to find a way to make sure you’re never going to destroy yourself, or you’re destroyed. So, in that sense he’s right. And then it will be: Will we survive for billions… ‘Billions’ is an awfully long time, but hundreds of millions, you know… We’re quibbling about an order of magnitude on the high-end, there. But basically, yes, I believe in [terms of] round numbers and proximate orders of magnitude, he is absolutely right.

The window is very small to avoid the existential threats that come with radio. The line through the engineering and the physics from radio, and understanding how radio waves work, and so forth, leads directly to atomic power, leads directly to atomic weapons, blah, blah, blah, and leads conceivably directly to the destruction of the planet.

The artificial intelligence pioneer Marvin Minsky said, “Lately, I’ve been inspired by ideas from Robert Sawyer.” What was he talking about, and what ideas in particular, do you think?

Well, Marvin is a wonderful guy, and after he wrote that I had the lovely opportunity to meet him. And, actually ironically, my most significant work about artificial intelligence, Wake, Watch, and Wonder came out after Marvin said that. I went to visit Marvin, who was now professor emeritus by the time I went to visit him at the AI Lab at MIT, when I was researching that trilogy.

So he was talking mostly about my book Mindscan, which was about whether or not we would eventually be able to copy and duplicate human consciousness—or a good simulacrum thereof—in an artificial substrate. He was certainly intrigued by my work, which was—what a flattering thing. I mean, oh my God, you know, Minsky is one of those names science fiction writers conjure with, you named another, Carl Sagan.

These are the people who we voraciously read—science fiction writers, science fiction fans—and to know that you turned around, and they were inspired to some degree… that there was a reciprocity—that they were inspired by what we science fiction writers were doing—is in general a wonderful concept. And the specificity of that, that Marvin Minsky had read and been excited and energized intellectually by things I was writing was, you know, pretty much the biggest compliment I’ve ever had in my life.

What are your thoughts on artificial intelligence. Do you think we’re going to build an AGI, and when? Will it be good for us, and all of that? What’s your view on that?

So, you used the word ‘build’, which is a proactive verb, and honestly I don’t think… Well first, of course, we have a muddying of terms. We all knew what artificial intelligence meant in the 1960s—it meant HAL 9000. Or in the 1980s, it meant Data on Star Trek: The Next Generation. It meant, as HAL said, any self-aware entity could ever hope to be. It meant self-awareness, what we meant by artificial intelligence.

Not really were we talking about intelligence, in terms of the ability to really rapidly play chess, although that is something that HAL did in 2001: A Space Odyssey. We weren’t talking about the ability to recognize faces, although that is something HAL did, in fact. In the film, he manages to recognize specific faces based on an amateur sketch artist’s sketch, right? “Oh, that’s Dr. Hunter, isn’t it?” in a sketch that one of the astronauts has done.

We didn’t mean that. We didn’t mean any of these algorithmic things; we meant the other part of HAL’s name, the heuristic part of HAL: heuristically-programmed algorithmic computer, HAL. We meant something even beyond that; we meant consciousness, self-awareness… And that term has disappeared.

When you ask an AI guy, somebody pounding away at a keyboard in Lisp, “When is it going to say, ‘Cogito ergo sum’?” he looks at you like you’re a moron. So we’ve dulled the term, and I don’t think anybody anywhere has come even remotely close to simulating or generating self-awareness in a computer.

Garry Kasparov was rightly miffed, and possibly humiliated, when he was beaten at the thing he devoted his life to, grandmaster-level chess, by Deep Blue. Deep Blue did not even know that it was playing chess. Watson had no idea that it was playing Jeopardy. It had no inner life, no inner satisfaction, that it had beat Ken Jennings—the best human player at this game. It just crunched numbers, the way my old Texas Instruments 35 calculator from the 1970s crunched numbers.

So in that sense, I don’t think we’ve made any progress at all. Does that mean that I don’t think AI is just around the corner? Not at all; I think it actually is. But I think it’s going to be an emergent property from sufficiently complex systems. The existing proof of that is our own consciousness and self-awareness, which clearly emerged from no design—there’s no teleology to evolution, no divine intervention, if that’s your worldview.

And I don’t mean you, personally—as we talked here—but the listener. Well, we have nothing in common to base a conversation around this about. It emerged because, at some point, there was sufficient synaptic complexity within our brains, and sufficient interpersonal complexity within our social structures, to require self-reflection. I suspect—and in fact I posit in Wake, Watch, and Wonder—that we will get that eventually from the most complex thing we’ve ever built, which is the interconnectivity of the Internet. So many synapse analogues in links—which are both hyperlinks, and links that are physical cable, or fiber-optic, or microwave links—that at some point the same thing will happen… that intelligence and consciousness, true consciousness, [and] self-awareness, are an emergent property of sufficient complexity.

Let’s talk about that for a minute: There are two kinds of emergence… There is what is [known as] ‘weak emergence’, which is, “Hey, I did this thing and something came out of it, and man I wasn’t expecting that to happen.” So, you might study hydrogen, and you might study oxygen, and you put them together and there’s water, and you’re like, “Whoa!”…

And the water is wet, right? Which you cannot possibly [have] perceived that… There’s nothing in the chemistry of hydrogen or oxygen that would make the quality of a human perceiving it as being wet, and pair it to that… It’s an emergent property. Absolutely.

But upon reflection you can say, “Okay, I see how that happened.” And then there is ‘strong emergence’, which many people say doesn’t exist; and if it does exist, there may only be one example of it, which is consciousness itself. And strong emergence is… Now, you did all the stuff… Let’s take a human, you know—you’re made of a trillion cells who don’t know you or anything.

None of those cells have a sense of humor, and yet you have a sense of humor. And so a strong emergent would be something where you can look at what comes out if… And it can’t actually be derived from the ingredients. What do you think consciousness is? Is it a ‘weak emergent’?

So I am lucky enough to be good friends with Stuart Hameroff, and a friendly acquaintance with Hameroff’s partner, Roger Penrose—who is a physicist, of course, who collaborates with Stephen Hawking on black holes. They both think that consciousness is a strong emergent property; that it is not something that, in retrospect, we in fact—at least in terms of classical physics—can say, “Okay, I get what happened”; you know, the way we do about water and wetness, right?

I am quite a proponent of their orchestrated objective reduction model of consciousness. Penrose’s position, first put forward in The Emperor’s New Mind, and later—after he had actually met Hameroff—expounded upon at more length in Shadows of the Mind… so, twenty-year-old ideas now—that human consciousness must be quantum-mechanical in nature.

And I freely admit that a lot of the mathematics that Hameroff and Penrose argue is over my head. But the fundamental notion that the system itself transcends the ability of classical mathematics and classical physics to fully describe it. They have some truly recondite arguments for why that would be the case. The most compelling seems to come from Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, that there’s simply no way you can actually, in classical physics and classical mathematics, derive a system that will be self-reflective.

But from quantum physics, and superposition, perhaps you actually can come up with an explanation for consciousness.

Now, that said, my job as a science fiction writer is not to pick the most likely explanation for any given phenomenon that I turn my auctorial gaze on. Rather, it is to pick the most entertaining or most provocative or most intriguing one that can’t easily be gainsaid by what we already know. So is consciousness, in that sense, an emergent quantum-mechanical property? That’s a fascinating question; we can’t easily gainsay it because we don’t know.

We certainly don’t have a classical model that gives rise to that non-strong, that trivial emergence that we talked about in terms of hydrogen and oxygen. We don’t have any classical model that actually gives rise to an inner life. We have people who want to… you know, the famous book, Consciousness Explained (Dennett), which many of its critics would say is consciousness explained away.

We have the astonishing hypothesis of Crick, which is really, again, explaining away… You think you have consciousness in a sophisticated way, well you don’t really. That clearly flies as much in the face of our own personal experience as somebody saying, “‘Cognito ergo sum‘—nah, you’re actually not thinking, you’re not self-aware.” I can’t buy that.

So in that sense, I do think that consciousness is emergent, but it is not necessarily emergent from classical physics, and therefore not necessarily emergent on any platform that anybody is building at Google at the moment.

Penrose concluded, in the end, that you cannot build a conscious computer. Would you go all that far, or do you have an opinion on that?

You cannot build a conscious classical computer. Absolutely; I think Penrose is probably right. Given the amount of effort we have been trying, and that Moore’s Law gives us a boost to our effort every eighteen months or whatever figure you want to plug into it these days, and that we haven’t attained it yet, I think he’s probably right. A quantum computer is a whole different kettle of fish. I was lucky enough to visit D-Wave computing on my last book tour, a year ago, where it was very gratifying.

You mentioned the lovely thing that Marvin Minsky said… When I went to D-Wave, which is the only commercial company shipping quantum computers—Google has bought from them, NASA has bought from them… When I went there, they asked me to come and give a talk as well, [and] I said, “Well that’s lovely, how come?” And they said, “Everybody at D-Wave reads Robert J. Sawyer.”

I thought, “Oh my God, wow, what a great compliment.” But because I’m a proponent—and they’re certainly intrigued by the notion—that quantum physics may be what underlies the self-reflective ability—which is what we define consciousness as—I do think that if there is going to be a computer in AI, that it is going to be a quantum computer, quantumly-entangled, that gives rise to anything that we would actually say, “Yep, that’s as conscious as we are.”

So, when I started off asking you about an AGI, you kind of looped consciousness in. To be clear, those are two very different things, right? An AGI is something that is intelligent, and can do a list of tasks a human could do. A consciousness… it may have nothing, maybe not be intelligent at all, but it’s a feeling… it’s an inner-feeling.

But see, this is again… but it’s a conflation of terms, right? ‘Intelligence’, until Garry Kasparov was beaten at chess, intelligence was not just the ability to really rapidly crunch numbers, which is all… I’m sorry, no matter what algorithm you put into a computer, a computer is still a Turing machine. It can add a symbol, it can subtract a symbol. It can move left, it can move right—there’s no computer that isn’t a Turing machine.

The general applicability of a Turing machine to simulating a thing that we call intelligence, isn’t, in fact, what the man on the street or the woman on the street means by intelligence. So we say, “Well, we’ve got an artificially-intelligent algorithm for picking stocks.”

“Oh, well, if it picks stocks, which tie should I wear today?”

Any intelligent person would tell you, don’t wear the brown tie with the blue suit, [but] the stock-picking algorithm has no way to crunch that. It is not intelligent, it’s just math. And so when we take a word like ‘intelligence’… And either because it gets us a better stock option, right, we say, “Our company’s going public, and we’re in AI”—not in rapid number crunching—our stock market valuation is way higher… It isn’t intelligence as you and I understand it at all, full stop. Not one wit.

Where did you come down on the uploading-your-consciousness possibility?

So, I actually have a degree in broadcasting… And I can, with absolutely perfect fidelity, go find your favorite symphony orchestra performing Beethoven’s Fifth, let’s say, and give you an absolutely perfect copy of that, without me personally being able to hold a tune—I’m tone deaf—without me personally having the single slightest insight into musical genius.

Nonetheless, technically, I can reproduce musical genius to whatever bitrate of fidelity you require, if it’s a digital recording, or in perfect analog recording, if you give me the proper equipment—equipment that already is well available.

Given that analogy, we don’t have to understand consciousness; all we have to do is vacuum up everything that is between our ears, and find analog or digital ways to reproduce it on another substrate. I think fundamentally there is no barrier to doing that. Whether we’re anywhere near that level of fidelity in recording the data—or the patterns, or whatever it is—that is the domain of consciousness, within our own biological substrate… We may be years away from that, but we’re not centuries away from that.

It’s something we will have the ability to record and simulate and duplicate this century, absolutely. So in terms of uploading ‘consciousness’—again, we play a slippery slope word with language… In terms of making an exact duplicate of my consciousness on another substrate… Absolutely, it’ll be done; it’ll be done this century, no question in my mind.

Is it the same person? That’s where we play these games with words. Uploading consciousness… Well, you know what—I’ve never once uploaded a picture of myself to Facebook, never once— [but] the picture is still on my hard drive; [and] I’ve copied it, and sent it to Facebook servers, too. There’s another version of that picture, and you know what? You upload a high-resolution picture to Facebook, put it up as your profile photo… Facebook compresses it, and reduces the resolution for their purposes at their end.

So, did they really get it? They don’t have the original; it’s not the same picture. But at first blush, it looks like I uploaded something to the vast hive that is Facebook… I have done nothing of the sort. I have duplicated data at a different location.

One of the themes that you write about is human life extension. What do you think of the possibilities there? Is mortality a problem that we can solve, and what not?

This is very interesting… Again, I’m working on this TV project, and this is one of our themes… And yes, I think, absolutely. I do not think that there’s any biological determinism that says all life forms have to die at a certain point. It seems an eminently-tractable problem. Remember, it was only [in] the 1950s that we figured out the double-helix nature of DNA. Rosalind Franklin, Francis Crick and James Watson figured it out, and we have it now.

That’s a blip, right? We’ve had a basic understanding of the structure of the genetic molecule, and the genetic code, and [we’re] only beginning to understand… And every time we think we’ve solved it—”Oh, we’ve got it. We now understand the code for that particular amino acid…” But then we forgot about epigenetics. We thought, in our hubris and arrogance, “Oh, it’s all junk DNA”—when after all, actually they’re these regulatory things that turn it on and off, as is required.

So we’re still quite some significant distance away from totally solving why it is we age… arresting that first, and [then] conceivably reversing that problem. But is it an intractable problem? Is it unsolvable by its nature? Absolutely not. Of course, we will have, again, this century-radical life prolongation—effective practical immortality, barring grotesque bodily accident. Absolutely, without question.

I don’t think it is coming as fast as my friend Aubrey De Grey thinks it’s coming. You know, Aubrey… I just sent him a birthday wish on Facebook; turns out, he’s younger than me… He looks a fair bit older. His partner smokes, and she says, “I don’t worry about it, because we’re going to solve that before the cancers can become an issue.”

I lost my younger brother to lung cancer, and my whole life, people have been saying, “Cancer, we’ll have that solved in twenty years,” and it’s always been twenty years down the road. So I don’t think… I honestly think I’m… you and I, probably, are about the same age I imagine— [we] are at a juncture here. We’re either part of the last generation to live a normal, kind of biblical—threescore and ten, plus or minus a decade or two—lifespan; or we’re the first generation that’s going to live a radically-prolonged lifespan. Who knows which side of that divide you and I happen to be on. I think there are people alive already, the children born in the early—certainly in the second decade, and possibly the first—part of the century who absolutely will live to see not just the next century—twenty-second—but some will live to see beyond that, Kirk’s twenty-third century.

Putting all that together, are you worried about, as our computers get better—get better at crunching numbers, as you say—are you among the camp that worries that automation is going to create an epic-sized social problem in the US, or in the world, because it eliminates too many jobs too quickly?

Yes. You know, everybody is the crucible of their upbringing, and I think it’s always important to interrogate where you came from. I mentioned [that] my father took me to 2001. Well, he took a day off, or had some time off, from his job—which was a professor of economics at the University of Toronto—so that we could go to a movie. So I come from a background… My mother was a statistician, my father an economist…

I come from a background of understanding the science of scarcity, and understanding labor in the marketplace, and capitalism. It’s in my DNA, and it’s in the environment I grew up [in]. I had to do a pie chart to get my allowance as a kid. “Here’s your scarce resources, your $0.75… You want a raise to a dollar? Show me a pie chart of where you’re spending your money now, and how you might usefully spend the additional amount.” That’s the economy of scarcity. That’s the economy of jobs and careers.

My father set out to get his career. He did his PhD at the University of Chicago, and you go through assistant professor, associate professor, professor, now professor emeritus at ninety-two years old—there’s a path. All of that has been disrupted by automation. There’s absolutely no question it’s already upon us in huge parts of the environment, the ecosystem that we live in. And not just in terms of automotive line workers—which, of course, were the first big industrial robots, on the automobile assembly lines…

But, you know, I have friends who are librarians, who are trying to justify why their job should still exist, in a world where they’ve been disintermediated… where the whole world’s knowledge—way more than any physical library ever contained—is at my fingertips the moment I sit down in front of my computer. They’re being automated out of a job, and [although] not replaced by a robot worker, they’re certainly being replaced by the bounty that computers have made possible.

So yeah, absolutely. We’re going to face a seismic shift, and whether we survive it or not is a very interesting sociological question, and one I’m hugely interested in… both as an engaged human being, and definitely as a science fiction writer.

What do you mean survive it?

Survive it recognizably, with the culture and society and individual nation-states that have defined, let’s say, the post-World War II peaceful world order. You know, you look back at why Great Britain has chosen to step out of the European Union.

[The] European Union—one can argue all kind of things about it… but one of the things it basically said was, “Man, that was really dumb, World War I. World War II, that was even worse. All of us guys who live within spitting distance of each other fighting, and now we’ve got atomic weapons. Let’s not do that anymore. In fact, let’s knock down the borders and let’s just get along.”

And then, one of the things that happen to Great Britain… And you see the far right party saying, “Well, immigration is stealing our jobs.” Well, no. You know, immigration is a fact of life in an open world where people travel. And I happen to be—in fact, just parenthetically—I’m a member of the Order of Canada, Canada’s highest civilian honor. One of the perks that comes with that is I’m empowered to, and take great pride in, administering the oath of Canadian citizenship at Canadian citizenship ceremonies.

I’m very much pro-immigration. Immigrants are not what’s causing jobs to disappear, but it’s way easier to point to that guy who looks a bit different, or talks a bit different than you do, and say that he’s the cause, and not that the whole economic sector that you used to work in is being obviated out of existence. Whether it was factory workers, or whether it was stock market traders, the fact is that the AIG, and all of that AGI that we’ve been talking about here, is disappearing those jobs. It’s making those jobs cease to exist, and we’re looking around now, and seeing a great deal of social unrest trying to find another person to blame for that.

I guess implicit in what you’re saying is, yes, technology is going to dislocate people from employment. But what about the corollary, that it will or won’t create new jobs at the same essential rate?

So, clearly it has not created jobs at the same essential rate, and clearly the sad truth is that not everybody can do the new jobs. We used to have a pretty full employment no matter where you fell, you know… as Mr. Spock famously said, “—as with all living things, each according to his gifts.” Now it’s a reality that there is a whole bunch of people who did blue-collar labor, because that was all that was available to them…

And of course, as you know, Neil Degrasse Tyson and others have famously said, “I’m not particularly fascinated by Einstein’s brain per se… I’m mortified by the fact that there were a million ‘Einsteins’ in Africa, or the poorest parts of the United States, or wherever, who never got to give the world what the benefits of their great brains could have, because the economic circumstances didn’t exist for them to do that in.”

What jobs are going to appear… that are going to appear… that aren’t going to be obviated out of existence?

I was actually reading an interesting article, and talking at a pub last night with the gentleman—who was an archaeologist—and an article I read quite recently, about top ten jobs that aren’t soon going to be automated out of existence… and archaeologist was one of them. Why?

One, there’s no particular economic incentive… In fact, archaeologists these days tend to be an impediment to economic growth. That is, they’re the guys to show up when ground has been broken for new skyscrapers and say, “Hang on a minute… indigenous Canadian or Native American remains here… you’ve got a slow down until we collect this stuff,” right?

So no businesses say, “Oh my God, if only archaeologists were even better at finding things, that would stop us from our economic expansion.” And it has such a broadly-based skill set. You have to be able to identify completely unique potsherds, each one is different from another… not something that usually fits a pattern like a defective shoe going down an assembly line: “Oh, not the right number of eyelets on that shoe, reject it.”

So will we come up with job after job after job, that Moore’s Law, hopscotching ahead of us, isn’t going to obviate out of existence ad infinitum? No, we’re not going to do it, even for the next twenty years. There will be massive, massive, massive unemployment… That’s a game changer, a societal shift.

You know, the reality is… Why is it I mentioned World War I? Why do all these countries habitually—and going right back to tribal culture—habitually make war on a routine basis? Because unoccupied young men—and it’s mostly men that are the problem—have always been a detriment to society. And so we ship them off to war to get rid of the surplus.

In the United States, they just lowered the bar on drug possession rules, to define an ability to get the largest incarcerated population of people, who otherwise might just [have] been up to general mischief—not any seismic threat, just general mischief. And societies have always had a problem dealing with surplus young men. Now we have surplus young men, surplus plus young women, surplus old men, surplus old women, surplus everybody.

And there’s no way in hell—and you must know this, if you just stop and think about it—no way in hell that we’re going to generate satisfactory jobs, for the panoply that is humanity, out of ever-accelerating automation. It can’t possibly be true.

Let’s take a minute and go a little deeper in that. You say it in such finality, and such conviction, but you have to start off by saying… There is not, among people in that world… there isn’t universal consensus on the question.

Well, for sure. My job is not to have to say, “Here’s what the consensus is.” My job, as a prognosticator, is to say, “Look. Here is, after decades of thinking about it…”—and, you know, there was Marvin Minsky saying, “Look. This guy is worth listening to”… So no, there isn’t universal consensus. When you ask the guy who’s like, “I had a factory job. I don’t have that anymore, but I drive for Uber.”

Yeah, well, five years from now Uber will have no drivers. Uber is at the cutting edge of automating cars. So after you’ve lost your factory job, and then, “Okay, well I could drive a car.” What’s the next one? It’s going be some high-level diagnostician of arcane psychiatric disorders? That ain’t the career path.

The jobs that are automated out of existence are going to be automated out of existence in a serial fashion… the one that if your skill set was fairly low—a factory worker—then you can hopscotch into [another] fairly low one—driving a car—you tell me what the next fairly low-skillset job, that magically is going to appear, that’s going to be cheaper and easier for corporations to deploy to human beings.

It ain’t counter help at McDonald’s; that’s disappearing. It ain’t cash registers at grocery stores, that’s disappearing. It ain’t bank teller, that already disappeared. It ain’t teaching fundamental primary school. So you give me an example of why the consensus, that there is a consensus… Here you show me. Don’t tell me that the people disagree with me… Tell me how their plot and plan for this actually makes any sense, that bares any scrutiny.

Let’s do that, because of… My only observation was not that you had an opinion, but that [it] was bereft of the word ‘maybe’. Like you just said ATM, bank tellers… but the fact of the matter is—the fact on the ground is—that the number of bank tellers we have today is higher than pre-ATM days.

And the economics that happened, actually, were that by making ATMs, you lowered the cost of building new bank branches. So what banks did was they just put lots more branches everywhere, and each of those needed some number of tellers.

So here’s an interesting question for you… Walk into your bank… I did this recently. And the person I was with was astonished, because every single bank teller was a man, and he hadn’t been into a bank for awhile, and they used to all be women. Now, there’s no fundamental difference between the skill set of men and women; but there is a reality in the glass ceiling of the finance sector.

And you cannot dispute that it exists… that the higher-level jobs were always held by men, and lower-level jobs were held by women. And the reality is… What you call a bank teller is now a guy who doesn’t count out tens and twenties; he is a guy who provides much higher-level financial services… And it’s not that we upgraded the skill set of the displaced.

We didn’t turn all of those counter help people at McDonald’s into Cordon Bleu chefs, either. We simply obviated them out of existence. And the niches, the interstices, in the economy that do exist, that supplement or replace the automation, are not comparably low-level jobs. You do not fill a bank with tellers who are doing routine counting out of money, taking a check and moving it over to the vault. That is not the function.

And they don’t even call them tellers anymore, they call them personal financial advisors or whatever. So, again, your example simply doesn’t bear scrutiny. It doesn’t bear scrutiny that we are taking low-level jobs… And guess what now we have… Show me the automotive plant that has thousands and thousands of more people working on the assembly line, because that particular job over there—spraying the final coat of paint—was done to finer tolerance by a machine… But oh my God, well, let’s move them…

No, that’s not happening. It’s obfuscation to say that we now have many more people involved in bank telling. This is the whole problem that we’ve been talking about here… Let’s take terminology and redefine it, as we go along to avoid facing the harsh reality. We have automated telling machines because we don’t have human telling individuals anymore.

So the challenge with your argument, though, is it is kind of the old one that has been used for centuries. And each time it’s used, it’s due to a lack of imagination.

My business, bucko, is imagination. I have no lack thereof, believe me. Seriously. And it hasn’t been used for generations. Name a single Industrial Revolution argument that invoked Moore’s Law. Name one. Name one that said the invention of the loom will outpace the invention of…

Human inventiveness was always the constraint, and we now do not have human inventiveness as the constraint. Artificial intelligence, whether you define it your way or my way, is something that was not invoked for centuries. We wouldn’t be having this conversation via Skype or whatever, like—Zoom, we’re using here—these are game changers that were not predicted by anybody but science fiction writers.

You can go back and look at Jules Verne, and his novel that he couldn’t get published in his lifetime, Paris in the Twentieth Century, that is incredibly prophetic about television, and so forth, and nobody believed it. Me and my colleagues are the ones that give rise to—not just me, but again that example: “Lately, I’m inspired by Robert J. Sawyer,” says Marvin Minsky. Lately I’m inspired by science fiction… I’m saying belatedly, much of the business world is finally looking and taking seriously science fiction.

I go and give talks worldwide—at Garanti Bank, the second largest bank in Istanbul, awhile ago—about inculcating the science fiction extrapolative and imaginative mindset in business thinkers… Because no, this argument, as we’re framing it today, has not been invoked for centuries.

And to pretend that the advent of the loom, or the printing press, somehow gave rise to people saying, “The seismic shift that’s coming from artificial intelligence, we dealt with that centuries ago, and blah, blah, blah… it’s the same old thing” is to have absolute blinders on, my friend. And you know it well. You wouldn’t be doing a podcast about artificial intelligence if you thought, “Here we are at podcast ‘Loom version 45.2’; we’re gonna have the Loom argument about weaving again for the umpteenth time.” You know the landscape is fundamentally, qualitatively different today.

So that’s a little disingenuous. I never mentioned the loom.

Let’s not be disingenuous. What is your specific example, of the debate related to the automation out of existence—without the replacement of the workers—with comparable skillset jobs from centuries ago? I won’t put an example [in] your mouth; you put one on the table.

I will put two on the table. The first is the electrification of industry. It happened with lightning speed, it was pervasive, it eliminated enormous numbers of jobs… And people at that point said, “What are we going to do with these people?”

I’ll give you a second one… It took twenty years for the US to go from generating five percent of its power with coal, to eighty percent. So in [the span of] twenty years, we started artificially generating our power.

The third one I’d like to give you is the mechanization of the industry… [which] happened so fast, and replaced all of the millions and millions and millions of draft animals that had been used in the past.

So let’s take that one. Where are the draft animals in our economy today? They’re the only life forms in our economy that can be replaced. The draft animals that can be replaced by machines, and the humans that operated them. Now we’ve eliminated draft animals, so the only biology in our economy is Homo sapiens. We are eliminating the Homo sapiens. You’re not gonna find new jobs for the Homo sapiens any more, than except maybe at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave, where we found a job for a jackass.

Are you going to find a place to put a draft animal on the payroll today? And you’re not going to find a place to put Homo sapiens, the last biology in the equation, on the payroll tomorrow, except in a vanishing few economic niches.

So the challenge with that view is that in the history of this country, unemployment has been between four and nine percent the entire time, with the exception of the Depression… [between] four and nine percent.

Now, ‘this country’ meaning United States of America, which is not where I am.

Oh I’m sorry. Yes, in the United States of America, four to nine percent, with [the] exception of the Depression. During that time, of course, you had an incredible economic upheaval… But, say from 1790 to 1910, or something like that, [unemployment] never moved [from] four to nine percent.

Meanwhile, after World War II, [we] started adding a million new people, out of the blue, to the workforce. You had a million women a year come into the workforce, year after year, for forty years. So you had forty million new people, between 1945 and 1985, come into the workplace… and unemployment never bumped.

So what it suggests is, that jobs are not these things that kind of magically appear as we go through time, saying “Oh, there’s a job. Oh, that’s an unskilled one, great. Or that’s a job…” It just doesn’t happen that way—

—When women entered into the workforce—and I speak as the son of a woman who was a child prodigy, and was the only woman in her economics class at the University of California at Berkeley, who taught at a prestigious university—I have no doubt that there were occasional high-level jobs. But the jobs that were created, that women came in and filled—and are still butting against the glass ceiling of—were low-level jobs.

It wasn’t, “Oh my God, we suddenly need thousands of new computer programmers.” No, we’ve created a niche that no longer exists for keypunch operators, as an example; or for telephone operators, as an example; or for bank tellers, as an example. And those jobs, to a person, have been obviated out of existence, or will be in the next decade or two.

Yes, I mean, you make an interesting metric about the size of unemployment. But remember, too, that the unemployment figure is a slippery slope, when you say ‘the number of people actively looking for employment’. Now you ask, how many people have just given up any hope of being employed meaningfully, respectfully, in dignity? Again, that number has gone up, as a straight line graph, through automation evolution.

No, I disagree with that. If you’re talking about workforce utilization, or the percentage of people who have gainful employment, there has been a dip over the last… It’s been repeatedly dissected by any number of people, and it seems there’s three things going on with it.

One is, Baby Boomers are retiring, and they’re this lump that passes through the economy, so you get that. Then there’s seasonality baked into that number. So they think the amount of people who have ‘given up’ is about one quarter of one percent, so sure… one in four hundred.

So what I would say is that ’95, ’96, ’97 we have the Internet come along, right? And if you look, between ’97 and the last twenty years, at the literal trillions—not an exaggeration, trillions upon trillions upon trillions of dollars of wealth that it created—you get your Googles, you get your eBays, you get your Amazons… these trillions and trillions and trillions of dollars of wealth. Nobody would have seen that [coming] in 1997.

Nobody says, “Oh yes, the connecting of various computers together, through TCP/IP, and allowing them to communicate with hypertext, is going to create trillions upon trillions upon trillions of dollars’ worth of value, and therefore jobs.” And yet it did. Unemployment is still between four and nine percent, it never budges.

So it suggests that jobs are not magically coming out of the air, that what happens is you take any person at any skill level… they can take anything, and apply some amount of work to it, and some amount of intellectual property to it, and make something worth more. And the value that they added, that’s known as a wage, and whatever they can add to that, whatever they meaningfully add to it, well that just created a job.

It doesn’t matter if it is a low-skill person, or a high-skill person, or what have you; and that’s why people maintain the unemployment rate never moves, because there’s an infinite amount of jobs, they exist kind of in the air… just go outside tomorrow, and knock on somebody’s door, and offer to do something for money, and you just made a job.

So go outside and offer to do what, and make a job? Because there are tons of things that I used to pay people to do that I don’t anymore. My Roomba cleans my floor, as opposed to a cleaning lady, is a hypothetical example.

But don’t you spend that money now on something else, which ergo is a job.

Spending money is a job?

Well spending money definitely, yes, creates employment.

Well that’s a very interesting discussion that we could have here, because certainly I used to have to spend money if I wanted something. Now if I want to watch—as we saw this past week, as we record this… The new season of Orange is the New Black, before the intellectual property creators want to deploy it to me, and collect money for it… Oh, guess what? It’s been pirated, and that’s online for free.

If I want to read, or somebody listening to this wants to read any of my twenty-three novels, they could go and buy the ebook edition, it’s true; but there’s an enormous amount of people who are also pirating them, and also the audio books. So this notion that somehow technology has made sure that we buy things with our money, I think a lot of people would take economic exception with that.

In fact, technology has made sure that there are now ways in which you can steal without… And it comes back to the discussion we’re having about AI: “Oh, I now have a copy, you still have the original. In what possible, meaningful way have I stolen from you?” So we actually have game-changers that I think you’re alighting over. But setting aside that, okay, obviously we disagree on this point. Fine, let’s touch base in fifty years, if either of us still has a job, and discuss it.

The easy thing is to always say there’s no consensus. Then you don’t have to go out on a limb, and nobody can ever come back to you and say you’re wrong. What we do in politics these days is, we don’t want people to change their ideas. Sadly, we say, “Forty years ago, you said so-and-so, you must still hold that view.” No, a science fiction writer is like a scientist; we are open, all the time, to new information and new data. And we’re constantly revising our worldview.

Look at the treatment of artificial intelligence, our subject matter today, from my first novel in 1990, to the most recent one I treated the topic, in which would be Wonder, that came out in 2011—and there’s definitely an evolution of thought there. But it’s a mug’s game to say, “There’s no consensus, I’m not gonna make a prediction.”

And it actually is a job, my friend, and one that turns out to be fairly lucrative—at least in my case—to make a prediction, to look at the data, and say… You know, I synthesize it, look at it this way, and here’s where I think it’s going. And if you want to obviate that job out of existence, by saying yeah but other people disagree with you, I suppose that’s your privilege in this particular economic paradigm.

Well, thank you very much. Tell us what you’re working on in closing?

It’s interesting, because when we talk a lot about AI… But I’m really… AI, and the relationship between us and AI, is a subset, in some ways, of transhumanism. In that you can look at artificial intelligence as a separate thing, but really the reality is that we’re going to find way more effective ways to merge ourselves and artificial intelligence than looking in through the five-inch glass window on your smartphone, right?

So what I’m working on is actually developing a TV series on a transhumanist theme, and one of the key things we’re looking at is really that fundamental question of how much of your biology—one of the things we’ve talked about here—you can give up and still retain your fundamental humanity. And I don’t want to get into too much specifics about that, but I think that is, you know, really comes thematically right back to what we’ve been talking about here, and what Alan Turing was getting at with the Turing test.

A hundred years from now, have I uploaded my consciousness? Have I so infused my body with nanotechnology, am I so constantly plugged into a greater electronic global brain… am I still Homo sapient sapiens? I don’t know, but I hope I’ll have that double dose of wisdom that goes with sapient sapiens by that time. And that’s what I’m working on, is really exploring the human-machine proportionality that still results in individuality and human dignity. And I’m doing it in a science fiction television project that I currently have a development contract for.

Awesome. Alright, well thank you so much.

It was a spirited discussion, and I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did, because one of the things that will never be obviated out of existence, I hope, my friend, is spirited and polite disagreement between human beings. I think that is—if there’s something we’ve come nowhere close to emulating on an artificial platform, it’s that. And if there’s any reason that AI’s will keep us around, I’ve often said, it’s because of our unpredictability, our spontaneity, our creativity, and our good sense of humor.

Absolutely. Thank you very much.

My pleasure, take care.

Byron explores issues around artificial intelligence and conscious computers in his upcoming book The Fourth Age, to be published in April by Atria, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. Pre-order a copy here.

Voices in AI

Visit VoicesInAI.com to access the podcast, or subscribe now:

iTunes

Play

Stitcher

RSS

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed {

font-size: 1.4rem;

background: url(http://ift.tt/2g4q8sx) black;

background-position: center;

background-size: cover;

color: white;

padding: 1rem 1.5rem;

font-weight: 200;

text-transform: uppercase;

margin-bottom: 1.5rem;

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed:last-of-type {

margin-bottom: 0;

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed .logo {

margin-top: .25rem;

display: block;

background: url(http://ift.tt/2g3SzGL) center left no-repeat;

background-size: contain;

width: 100%;

padding-bottom: 30%;

text-indent: -9999rem;

margin-bottom: 1.5rem

}

@media (min-width: 960px) {

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed .logo {

width: 262px;

height: 90px;

float: left;

margin-right: 1.5rem;

margin-bottom: 0;

padding-bottom: 0;

}

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed a:link,

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed a:visited {

color: #FF6B00;

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back a:hover {

color: #ff4f00;

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links {

margin-left: 0 !important;

margin-right: 0 !important;

margin-bottom: 0.25rem;

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:link,

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:visited {

background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.77);

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:hover {

background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.63);

}

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links .stitcher .stitcher-logo {

display: inline;

width: auto;

fill: currentColor;

height: 1em;

margin-bottom: -.15em;

}

Voices in AI – Episode 16: A Conversation with Robert J. Sawyer syndicated from http://ift.tt/2wBRU5Z

0 notes

Text

Voices in AI – Episode 16: A Conversation with Robert J. Sawyer

Today's leading minds talk AI with host Byron Reese

.voice-in-ai-byline-embed { font-size: 1.4rem; background: url(https://voicesinai.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/cropped-voices-background.jpg) black; background-position: center; background-size: cover; color: white; padding: 1rem 1.5rem; font-weight: 200; text-transform: uppercase; margin-bottom: 1.5rem; } .voice-in-ai-byline-embed span { color: #FF6B00; }

In this episode, Byron and Robert talk about human life extension, conscious computers, the future of jobs and more.

-

-

0:00

0:00

0:00

var go_alex_briefing = { expanded: true, get_vars: {}, twitter_player: false, auto_play: false }; (function( $ ) { 'use strict'; go_alex_briefing.init = function() { this.build_get_vars(); if ( 'undefined' != typeof go_alex_briefing.get_vars['action'] ) { this.twitter_player = 'true'; } if ( 'undefined' != typeof go_alex_briefing.get_vars['auto_play'] ) { this.auto_play = go_alex_briefing.get_vars['auto_play']; } if ( 'true' == this.twitter_player ) { $( '#top-header' ).remove(); } var $amplitude_args = { 'songs': [{"name":"Episode 16: A Conversation with Robert J. Sawyer","artist":"Byron Reese","album":"Voices in AI","url":"https:\/\/voicesinai.s3.amazonaws.com\/2017-10-30-(01-00-58)-robert-j-sawyer.mp3","live":false,"cover_art_url":"https:\/\/voicesinai.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2017\/10\/voices-headshot-card-2-1.jpg"}], 'default_album_art': 'https://gigaom.com/wp-content/plugins/go-alexa-briefing/components/external/amplify/images/no-cover-large.png' }; if ( 'true' == this.auto_play ) { $amplitude_args.autoplay = true; } Amplitude.init( $amplitude_args ); this.watch_controls(); }; go_alex_briefing.watch_controls = function() { $( '#small-player' ).hover( function() { $( '#small-player-middle-controls' ).show(); $( '#small-player-middle-meta' ).hide(); }, function() { $( '#small-player-middle-controls' ).hide(); $( '#small-player-middle-meta' ).show(); }); $( '#top-header' ).hover(function(){ $( '#top-header' ).show(); $( '#small-player' ).show(); }, function(){ }); $( '#small-player-toggle' ).click(function(){ $( '.hidden-on-collapse' ).show(); $( '.hidden-on-expanded' ).hide(); /* Is expanded */ go_alex_briefing.expanded = true; }); $('#top-header-toggle').click(function(){ $( '.hidden-on-collapse' ).hide(); $( '.hidden-on-expanded' ).show(); /* Is collapsed */ go_alex_briefing.expanded = false; }); // We're hacking it a bit so it works the way we want $( '#small-player-toggle' ).click(); $( '#top-header-toggle' ).hide(); }; go_alex_briefing.build_get_vars = function() { if( document.location.toString().indexOf( '?' ) !== -1 ) { var query = document.location .toString() // get the query string .replace(/^.*?\?/, '') // and remove any existing hash string (thanks, @vrijdenker) .replace(/#.*$/, '') .split('&'); for( var i=0, l=query.length; i<l; i++ ) { var aux = decodeURIComponent( query[i] ).split( '=' ); this.get_vars[ aux[0] ] = aux[1]; } } }; $( function() { go_alex_briefing.init(); }); })( jQuery ); .go-alexa-briefing-player { margin-bottom: 3rem; margin-right: 0; float: none; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#top-header { width: 100%; max-width: 1000px; min-height: 50px; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#top-large-album { width: 100%; max-width: 1000px; height: auto; margin-right: auto; margin-left: auto; z-index: 0; margin-top: 50px; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#top-large-album img#large-album-art { width: 100%; height: auto; border-radius: 0; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player { margin-top: 38px; width: 100%; max-width: 1000px; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player div#small-player-full-bottom-info { width: 90%; text-align: center; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player div#small-player-full-bottom-info div#song-time-visualization-large { width: 75%; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player-full-bottom { background-color: #f2f2f2; border-bottom-left-radius: 5px; border-bottom-right-radius: 5px; height: 57px; }

Voices in AI

Visit VoicesInAI.com to access the podcast, or subscribe now:

iTunes

Play

Stitcher

RSS

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed { font-size: 1.4rem; background: url(https://voicesinai.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/cropped-voices-background.jpg) black; background-position: center; background-size: cover; color: white; padding: 1rem 1.5rem; font-weight: 200; text-transform: uppercase; margin-bottom: 1.5rem; } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed:last-of-type { margin-bottom: 0; } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed .logo { margin-top: .25rem; display: block; background: url(https://voicesinai.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/voices-in-ai-logo-light-768x264.png) center left no-repeat; background-size: contain; width: 100%; padding-bottom: 30%; text-indent: -9999rem; margin-bottom: 1.5rem } @media (min-width: 960px) { .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed .logo { width: 262px; height: 90px; float: left; margin-right: 1.5rem; margin-bottom: 0; padding-bottom: 0; } } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed a:link, .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed a:visited { color: #FF6B00; } .voice-in-ai-link-back a:hover { color: #ff4f00; } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links { margin-left: 0 !important; margin-right: 0 !important; margin-bottom: 0.25rem; } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:link, .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:visited { background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.77); } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:hover { background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.63); } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links .stitcher .stitcher-logo { display: inline; width: auto; fill: currentColor; height: 1em; margin-bottom: -.15em; }

Byron Reese: This is voices in AI, brought to you by Gigaom. I’m Byron Reese. Our guest today is Robert Sawyer. Robert is a science fiction author, is both a Hugo and a Nebula winner. He’s the author of twenty-three books, many of which explore themes we talk about on this show. Robert, welcome to the show.

Tell me a little bit about your past, how you got into science fiction, and how you choose the themes that you write about?

Robert Sawyer: Well, I think apropos of this particular podcast, the most salient thing to mention is that when I was eight years old, 2001: A Space Odyssey was in theaters, and my father took me to see that film.

I happen to have been born in 1960, so the math was easy. I was obviously eight in ’68, but I would be 41 in 2001, and my dad, when he took me to see the film, was already older than that… which meant that before I was my dad’s age, talking computers [and] intelligent machines would be a part of my life. This was promised. It was in the title, 2001, and that really caught my imagination.

I had already been exposed to science fiction through Star Trek, which obviously premiered two years earlier, [in] ’66. But I was a little young to really absorb it. Heck, I may be a little young right now, at 57, to really absorb all that in 2001: A Space Odyssey. But it was definitely the visual world of science fiction, as opposed to the books… I came to them later.

But again, apropos of this podcast, the first real science fiction books I read… My dad packed me off to summer camp, and he got me two: one was just a space adventure, and the other was a collection of Isaac Asimov’s Robot Stories. Actually the second one [was] The Rest of the Robots, as it was titled in Britain, and I didn’t understand that title at all.

I thought it was about exhausted mechanical men having a nap—the rest of the robots—because I didn’t know there was an earlier volume when I first read it. But right from the very beginning, one of the things that fascinated me most was artificial intelligence, and my first novel, Golden Fleece, is very much my response to 2001… after having mulled it over from the time I was eight years old until the time my first novel came out.

I started writing it when I was twenty-eight, and it came out when I was thirty. So twenty years of mulling over, “What’s the psychology behind an artificial intelligence, HAL, actually deciding to commit murder?” So psychology of non-human beings, whether it’s aliens or AIs—and certainly the whole theme of artificial intelligence—has been right core in my work from the very beginning, and 2001 was definitely what sparked that.

Although many of your books are set in Canada, they are not all in the same fictional universe, correct?

That’s right, and I actually think… you know, I mentioned Isaac Asimov’s [writing] as one of my first exposures to science fiction, and of course still a man I enormously admire. I was lucky enough to meet him during his lifetime. But I think it was a fool’s errand that he spent a great deal of his creative energies, near the later part of his life, trying to fuse his foundation universe with his robot universe to come up with this master plan.

I think, a) it’s just ridiculous, it constrains you as writer; and b) it takes away the power of science fiction. Science fiction is a test bed for new ideas. It’s not about trying to predict the future. It’s about predicting a smorgasbord of possible futures. And if you get constrained into, “every work I did has to be coherent and consistent,” when it’s something I did ten, twenty, thirty, forty—in Asimov’s case, fifty or sixty years—in my past, that’s ridiculous. You’re not expanding the range of possibilities you’re exploring. You’re narrowing down instead of opening up.

So yeah, I have a trilogy about artificial intelligence: Wake, Watch, and Wonder. I have two other trilogies that are on different topics, but out of my twenty-three novels, the bulk of them are standalone, and in no way are meant to be thought of as being in a coherent, same universe. Each one is a fresh—that phrase I like—fresh test bed for a new idea.

That’s Robert Sawyer the author. What do you, Robert Sawyer the person, think the future is going to be like?

I don’t think there’s a distinction, in terms of my outlook. I’m an optimist. I’m known as an optimistic person, a techno-optimist, in that I do think, despite all the obvious downsides of technology—human-caused global climate change didn’t happen because of cow farts, it happened because of coal-burning machines, and so forth—despite that, I’m optimistic, very optimistic, generally as a person, and certainly most of my fiction…

Although my most recent book, my twenty-third, Quantum Night, is almost a deliberate step back, because there had been those that had said I’m almost Pollyanna-ish in my optimism, some have even said possibly naïve. And I don’t think I am. I think I rigorously interrogate the ideas in my fiction, and also in politics and day-to-day life. I’m a skeptic by nature, and I’m not easily swayed to think, “Oh, somebody solved all of our problems.”

Nonetheless, the arrow of progress, through both my personal history and the history of the planet, seems definitely to be pointing in a positive direction.

I’m an optimist as well, and the kind of arguments I get against that viewpoint, the first one invariably is, “Did you not read the paper this morning?”

Yeah.