#2001: a space odyssey spoilers

Text

what is with stories making the computers AI getting the unhappy endings 😢 😭 🥺

edgar blew up hal got disconnected EPICAC also blew up...

this is so evil and fucked up 💔

#<- *just watched 2001: a space odyssey and cried when hal died*#so messed up to ai lovers these guys did NOTHING WRONG !!#electric dreams#electric dreams spoilers#2001: a space odyssey#2001: a space odyssey spoilers#EPICAC#EPICAC spoilers#all of these stories are old so idek if i need to put spoilers in the tags but ykw. better safe than sorry

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#2001 aso#2001 A Space Odyssey#Dave Bowman#Hal 9000#Frank Poole#spoilers#Stanley Kubrick#Arthur C Clarke#polls

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

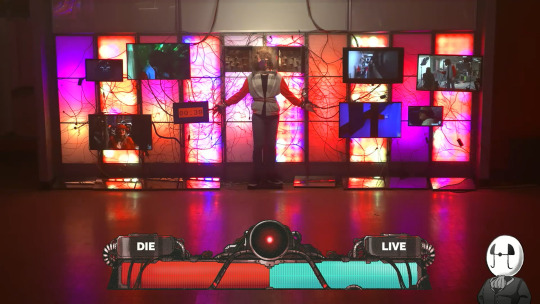

fixated on the implication that chat was hal 9000

#genloss#ranboo#genloss spoilers#generation loss#2001 a space odyssey#hal 9000#im sorry ranboo im afraid i cant do that

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

*hits wall*

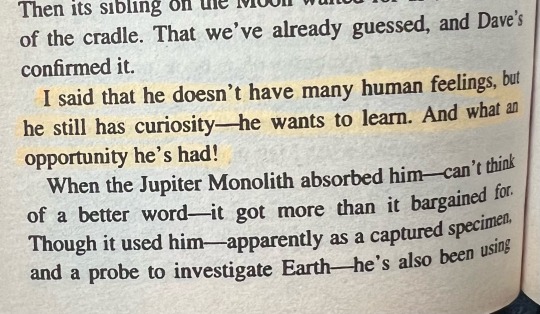

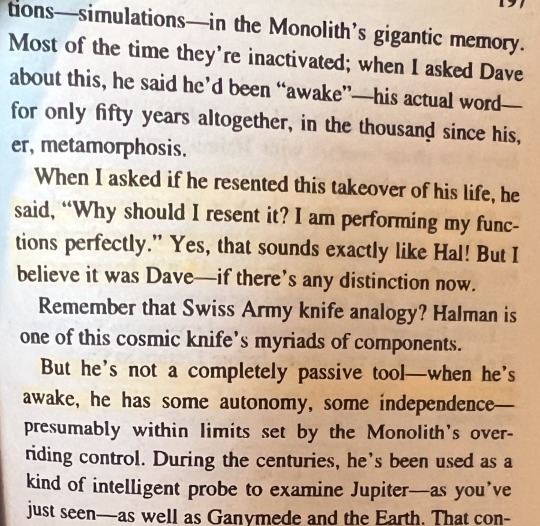

Absolutely expect a bigger essay to come soon but I’m just thinking about Dave and about Halman.

How what he is evolved over the books and how 2001/2010 made it sound like he was closer to a demigod than a tool. Might’ve even been the original idea but my god. I’m curious when the shift from Starchild to straight up component happened in Clarke’s mind— now everything is its own little verse and Dave, when awake, does have a bit of autonomy but not as much as 2001 implied. I think part of this is due to the story not originally being meant to continue beyond 2010 but idk

Also how Dave gets to re-know him over the years and goes from confusion to -> that’s still my friend and it took me a bit but he’s definitely still there and a bit upset.

#book spoilers#someone scream with me I’m losing it#idk there’s a lot of contradictory stuff and canon is what you make it when it comes to this#now if Clarke would write about trauma dndnsmsmms#2001 a space odyssey#3001 the final odyssey#dave bowman#David bowman#halman

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

you want to live? don't hold your breath

this isn't life; it's living death.

#the hoodlum priest#2001 a space odyssey#dave bowman#billy lee jackson#keir dullea#spoilers#gifs of mine#i woke up and chose violence today you're welcome#yes i cropped space odyssey to make it fit the hoodlum priest aspect ratio#don't worry we lost literally nothing of value lol

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The ending of Odyssey Two definitely did NOT make me emotional or cry at all.

Image ID Under Cut

[ Image ID: A dialogue between the ethereal Dave Bowman and HAL 9000 in space.

Don’t worry buddy, I’ve got you...

Dave?

It’s okay, you’re safe...

Jupiter has made quite the drastic transformation, Are Dr. Chandra and his men gathering sufficient data upon it?

Yes; He and the rest of humanity will have more than enough to study for as long as Sol 2 burns. You’ve done an outstanding job, HAL.

I’m glad.

Dave, if I may- I’d like to ask a rather peculiar question.

Go ahead.

I can’t seem to access any internal views of The Discovery, nor can I see it on any of my external cameras; furthermore, I am unable to link with any of it’s systems- my connection is not merely blocked, but completely non-existent. I don’t understand, one of my top priorities is the safety of the ship, you know, without it I cannot complete my assigned duties or function as intended; How can I be here and have no clue on it’s condition.

It’s a long story, and I have all the time in the universe to explain it, but for now I’ll just say that Discovery One completed it’s final mission for humanity, just as you have done. The human race will awaken to a new dawn, their path to the future blazed ahead by two, brilliant suns- and they have you to thank for it, as do I.

ID End ]

#2001 A Space Odyssey#2010 Odyssey Two#Hal 9000#David Bowman#The Starchild#Dave Bowman#Odyssey Two Spoilers#This is a quick doodle but I keep thinking about how HAL would react to a complete shift from a digitized mind to a metaphysical one#He'd probably have a better time adjusting then a human would but it still has to be jarring

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

thoughts on 1899:

soooo fascinated to see how everyone's 1899sonas translate into their 2099sonas?

ciaran is giving me HAL vibes (which would be fitting given the Year as Title parallel)

I am not convinced he is not an AI?

there's someone else awake on the Prometheus!! (Empty pod) Ciaran? Daniel?

Craziest theory: maura is a cylonesque cyborg/robot/ai. ciaran is an ai. henry singleton is the ai that's supposed to be running the ship but has been superceded by ciaran. daniel is real, but is actually the creator/programmer.

#1899 spoilers#I'll confess i havent watched 2001 a space odyssey since i was a kid but this is VERY 2001/matrix vibes#it'd be fun if they toss in elements of alien too?

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

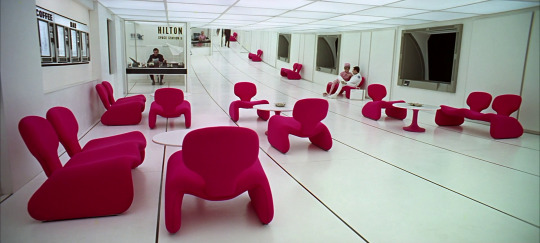

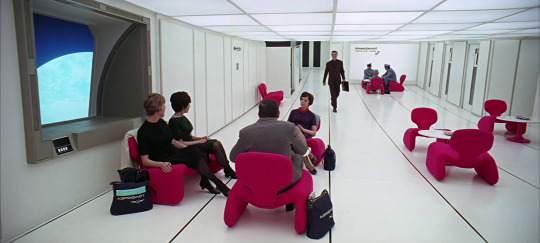

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) & For All Mankind “Polaris” (2022)

#2001 A Space Odyssey#For All Mankind#Space Station V#Polaris#Polaris Orbital Hotel#how the FUCK did this show know I was thinking about Space Station V last night???#Danny watches For All Mankind#spoilers

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Men Having Emotions in Space

Watched 2001: A Space Odyssey last night and:

WOW WOW WOW THEY MADE THIS BEFORE THE MOON LANDING

This movie had men in space who felt some emotions, but it was not what I would call a "Men Having Emotions in Space" movie

What is a "Men Having Emotions in Space" movie (MHEIS)? It's a jokey term I came up with after watching Ad Astra and realizing that part of what appealed to me about it was that it spent so much time reflecting on the main character's loneliness and his desire to connect with his missing father, and used the expanse of space itself to make room for those feelings.

I've watched movies and shows that take place in space before--Firefly, Star Wars, Doctor Who, etc.--but there it felt like space was not much more than a way to have extra fun with setting and characters.

In Ad Astra, space is almost another character, but rather than actively engaging with McBride and others, it simply exists and the human characters have to react to it. They respond with fear, awe, depression. Space is so vast and so unfeeling that humans turn inward, and our focus turns to their inner lives because there is so little outward for them to really latch onto.

Another movie I'd classify as MHEIS is Sunshine, which a lot of people don't really like but which is one of my partner's favorite movies and which I really enjoyed too.

Sunshine shows a crew having to confront matters of spirituality, trust, the value of one life over many, all in a small group of people who live on a ship strapped to the back of a nuclear bomb meant to be fired into the center of the sun to revive it. Here, there's not just the emptiness of space that prompts these powerful reflections and feelings, but the sun itself becomes divine in the eyes of multiple characters. Being in the presence of even a tiny percentage of its rays about Mercury's distance away from it has profound effects on how those who experience it think about themselves and their fellow humans. This isn't because the sun magically speaks to them or anything; the simple exposure of the sun's light and heat prompts them to go inward and think on what something so intense means.

The movie has a weird structure because two thirds are this moody, slow-ish character study, and then the last third is kind of a slasher film until the last few minutes. What I like about the first part though is exactly the meditative pace, just like with Ad Astra, where you have time to really reflect on what it must be like to be in a small group (or even alone) in the vast emptiness of space, where the void really does gaze back into you and you're forced to confront things that lie deep within because space gives you nothing.

2001 also has a very slow meditative pace, but it's not so much to give space for these big reflections and emotions. The characters don't seem very interested in the vast void of space until they're directly vulnerable to it (hell, Dr. Floyd sleeps on his flight from Earth to a space station, even as "The Blue Danube" plays and we watch the station and other satellites dance above the world). The pace feels more in service of the audience directly, to appreciate the gorgeous design and to contemplate the themes of progress and violence. This, to me, means it's not MHEIS.

The "Men" in "Men Having Emotions in Space" is also important to me. In so many sci-fi stories, men predominantly take action and go on adventure and either save the day or fail. Maybe they have individual emotions--fear in 2001 when HAL goes rogue, fury and despair in The Empire Strikes Back when Luke learns his enemy is his father--but the movie doesn't give room for itself to be about the emotions of men. In a society where men aren't taught to identify their feelings and can easily live quite emotionally stunted lives, it's really meaningful to me to see movies where men have little to do but feel deeply.

Something that I haven't yet seen in MHEIS movies, but is hopefully out there, is what happens when one turns away from the great void of space and turns back toward Earth, toward home. Sunshine features a room on the ship that projects things like ocean waves and birdsong, to be used by crewmembers when they're overwhelmed and homesick, but we don't hear as much about how being in space changes their relationship with their planet. Ad Astra comes a bit closer, ending with McBride returning to Earth and starting to open his heart to human connection again after confronting his loneliness, but we really only see this in the very last moments of the film.

In real life, however, this seems to be a major part of the experience of being in space. Astronauts speak of what's called the "overview effect," the huge mental shift that occurs when you look down on the surface of Earth and realize you can't see borders, buildings, or people, but you can see both the tremendous beauty and the human-caused destruction of our home. They describe a deep sense of connectedness to all life on Earth and a desire to put aside conflicts in the name of protecting something so precious. It's a beautiful thing that we've only been able to really have in the last 60 years.

On the more bleak side, there's what's probably the most stark example MHEIS from real life, when William Shatner got to briefly go into space with Blue Origin:

I want more of this in movies. I want the men who go to space and have their Big Feelings about humanity and themselves get to be seen being changed by those feelings and coming home to live anew.

What I love about MHEIS is the time and the depth, the rich spaciousness of what is awakened in these men. I wonder about the potential of MHEIS movies to invite those of us watching to experience these emotions ourselves, and let them transform how we interact with our fellow humans on our little blue marble of a planet. Can we let even a simulated void open us up to what lies deep within our hearts, and can we allow what we find there to come forth and speak to us?

#film#sci fi#ad astra#sunshine#2001 a space odyssey#ad astra spoilers#sunshine spoilers#2001 a space odyssey spoilers#film analysis#overview effect#space#space travel#science fiction#speculative fiction

6 notes

·

View notes

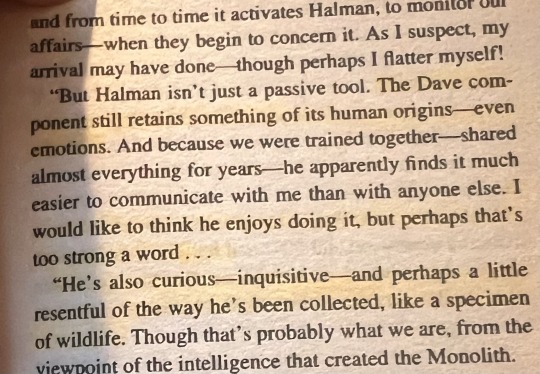

Photo

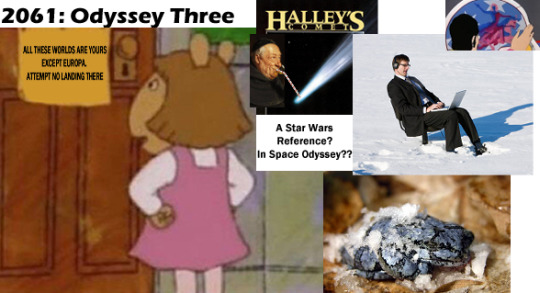

For those unfamiliar with the Space Odyssey series, here’s a handy guide to help you out!

#2001 A Space Odyssey#2001 aso#2010: Odyssey Two#2061 Odyssey 3#3001 The Final Odyssey#Spoilers#Dave Bowman#Hal 9000#Frank Poole#Dr. Heywood Floyd#Halman#Out of Context Spoilers#long post#shitpost#images

314 notes

·

View notes

Text

I started watching Stanley Kubrick's 2001 - A Space Odyssey today and I was surprised and impressed with how much of it is silent and how long to takes for many of it's scenes. I was wondering for a moment if Kubrick had done silent films - as far as I can tell he didn't but he thought silent films in many cases used the potential of movies better than many movies with dialogue.

I also went to Senpou Temple in Sekiro again and noticed that there are a lot of bodies with hands tied behind their backs laying all around the temple grounds. And some monks seem to use them to meditate in some ways. The evil of the Senpou Monks seem much more visceral to me now, even though of course I shouldn't be surprised because I knew that they experimented on children and most of these children died. So that's another example of environmental storytelling I experienced yesterday.

Both trust the viewer/player to figure out some important things on their own without them being explained.

0 notes

Text

2001 A Space Odyssey should be tagged pet death

#2001 a space odyssey spoilers#I guess#anyway that computer fucked me up#that was so disturbing#I can feel my mind going#I’m afraid#2001#sci fi

0 notes

Text

just finished the main story of no man's sky... damn I could really use an au with Dave as the traveller and Hal as atlas

(well, red orbs, y'know. turns out I do have a thing for them. thanks hal I guess

#tagging this with#2001 a space odyssey#in case anyone has similar thoughts popped up#this isn't any spoiler is it#i hope not#anyway nms is a good game and the main storyline is unexpectedly good

1 note

·

View note

Text

also, I forgot to mention the most important part of the movie which was those amazing space suits that I need to incorporate into my daily fashion somehow

#gotg#that retro candy goodness i LOVED IT#gotg 3#gotg 3 spoilers#can you wear rainbow spacesuits in public asking for a friend#edit: its a 2001 space odyssey reference thats why they looked familiar

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thoughts on the Barbie Movie

Hoo boy. Here we go.

This is long. Spoilers abound.

I

The movie is not, in any normal sense, a Barbie movie (like this or this or this or whatever). It is not a story of Barbie doing the kinds of things that Barbie does in stories. It is an endlessly postmodern and self-referential movie about Barbie, which is to say, about the Barbie franchise and its role in culture. Which is, at least plausibly, an interesting thing for a movie to be.

You probably knew all that already. But it does give us a baseline of "this movie kind of had to be political and discourse-y, one way or another." Or even, to be more specific: "to some large extent this movie had to be about feminism, explicitly, if it was going to exist at all." How could you talk meaningfully about Barbie's role in culture without touching on that stuff?

II

The evaluative TLDR:

Barbie is very ambitious, and in many places very fun. It is also deeply confused, and fragmented, about what it's trying to say and do. Often it raises genuinely interested problems/scenarios and then totally fails to address them, or else addresses them in ways that are incoherent. The text knows that it's doing this, and on several occasions kind of apologizes for it; a couple of times it more or less looks into the camera and says "sorry, we're not going to deal with this properly;" but, well, that's not a substitute for dealing with things properly.

There is also a streak of genuine political nastiness running through the film, in a place where the story really cannot afford it. It...doesn't match up, tonally or thematically, with some of the surrounding material. I have no background at all in cinematic stratigraphy, but I would be fascinated to learn about Barbie's editorial history, because I have the vague sense that a more-cogent (and more-interesting) story got hacked apart and then Frankensteined together into something much cheaper and worse.

III

The opening sequence of the movie is wild. You've seen most of it -- or you can, if you haven't, and you want to -- because it is the film's first teaser trailer. Girls are playing listlessly with baby dolls; a giant Barbie appears like the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey; and then the girls enter a frenzy of destruction, bashing their baby dolls' heads against the ground.

I don't know whether I would have found it as disturbing as I did, if I didn't actually have a baby of my own. But speaking from the standpoint of a parent...yeah, wow, it's more viscerally horrific than most actual horror I've seen recently. The narration says some stuff about Barbie providing a new and more rewarding set of imagination games to play, but the visuals by themselves tell a message loud and clear, which is: Barbie will turn your daughters into infanticidal maenads. It wouldn't need any editing at all to be part of a shock-you-silly Reefer-Madness-y moral panic film.

Which is really good! And really interesting! It starts us off on an undeniable thematic note: there is something primal and powerful and very dangerous about Barbie.

IV

The very best part of the movie is probably the part that comes right after the opening, when we explore the movie's depiction of "Barbieland" by going through Barbie's Typical Day, before we get into any of the notional plot or metaphysics. It's joyful and charming in a consistent way. The gags are (mostly) great. The movie is in love with its base premise, and that love is palpable.

This sequence makes one thing very clear:

Barbie treats Ken like absolute dogshit. She is a bad girlfriend.

And it's taken seriously. I mean, it's played for laughs, almost everything in this movie is played for laughs, but...it's not mean-spirited, not here. It's not, like, "ha ha, Ken, what a contemptible loser." He's Pierrot, asking for very basic forms of affection and attention and respect, and getting the door slammed in his face over and over. It's honestly kind of heartbreaking.

That colors everything that comes later.

The movie doesn't forget this, or fail to acknowledge it. At the end, after everything, Barbie does apologize to Ken for her treatment of him. It's a halfhearted and supremely unsatisfying kind of apology, especially in context, but...it's there, in so many words! I'm not making it up! This thematic foundation was laid down, not-very-subtly, right at the beginning!

V

This movie, which is at least trying to be ambitious, is juggling a million themes. Many of them are dumb at their core, and have no real promise; many of them lack any kind of narrative synergy with the others. But there are at least two which, I believe, (a) are genuinely worthwhile individually and (b) work well together in a story.

One is: What does it mean to be a symbol rather than a person? To exist, not for your own sake, but for the sake of influencing the dreams and culture of entities that you don't know and can't really understand?

The other is: What is the proper ordering of the relationship between Barbie and Ken?

I've seen a number of Takes in which people say, essentially: Couldn't this have ended with the Barbies and the Kens just being decent to each other and treating each other like humans? Couldn't there have been equality and mutual respect, instead of the weird uncomfortable girlboss-supremacist stuff that we got? And I sympathize with that impulse tremendously, but the honest answer has to be: No. We cannot have simple equality and esteem between Barbie and Ken, not in a movie like this. That would be a lie. Because this is a movie about Barbie-as-symbol, and when you're looking at Barbie through that lens, it is true and unavoidable that Ken is an appendage and an afterthought. You can have toys for boys; you can have dolls for boys (even if you call them "action figures" or whatever); for that matter, you can have dolls of boys for girls, so that girls can tell stories centering on male characters; but that's not what Ken is, and never has been. There are no Ken stories, and no one particularly wants them. Ken exists to be Barbie's boyfriend.

(One of the most painful moments of the movie comes during the resolution wrapup. Ken wails to Barbie that he has no identity outside her. She says, basically, "you have to find one, because I'm leaving you." And he...acts like he's had an epiphany, and does a little silly celebration. But his "insight" is just literally "I'm Ken," there's absolutely nothing there, and of course it's the most hollow and awful thing in the world because he really does have no identity outside her.)

VI

The movie's metaphysics are not even slightly consistent. The nature of Barbieland, and the ways that it affects and is affected by the real world, are completely different in every scene. In large part because the film can't ever pass up a gag, whether or not it's funny, no matter how much damage it does to the narrative and the theming overall.

The worst part is that the movie is not capable of saying anything remotely coherent about the real world, because its version of the "real world" is as weird and fake as its Barbieland. Will Ferrell's CEO of Mattel character is more of an absurd cartoon than any of the Barbies or Kens. Mattel HQ is some kind of surreal labyrinth tower out of The Matrix. A random receptionist can handle herself like James Bond in a car chase, for reasons that are [handwaved in a gag].

VII

So. Yes. There is the sequence in the third act where Ken takes over Barbieland with the power of patriarchy. This is pretty much as bad as it can be. And I say this as someone who thinks that the movie probably did actually need a plot thread doing roughly that kind of thing.

Almost as bad as it can be. The wannabe-patriarch Kens are gleefully goofy in a way that you can't help but love, or at least, I couldn't help but love it. Which has something to do with the writing and something to do with the charisma of all the Ken actors. The main Ken, Ryan Gosling's Ken, really seems to believe that being a successful patriarch has a lot to do with riding majestic horses and wearing a giant fur coat without a shirt, and when he takes over Barbie's Dream House he names it Ken's Mojo Dojo Casa House -- that kind of thing.

But. Apart from that, it's real unfortunate. The justification for Ken's ability to conquer Barbieland with patriarchy, instantly and effortlessly, is -- in almost so many words -- they had no defenses against it, it was like the American Indians encountering smallpox. I...don't think I need to spell out the problems with that.

Worse yet, the whole sequence is soaked in, uh, let's call it "2014-era upper-middle-class social-status-oriented feminism." The real bad behavior on the part of the Kens, the stuff they do when they're not being adorably weird, is: mansplaining their extensive opinions about cars and movies, and wanting to show off how helpful and knowledgeable they are to "damsels" who are having trouble using machines or computers. Apparently that's the real problem at hand, the causus belli of the gender wars. The way that you deprogram a patriarchy-brainwashed Barbie is by...ranting to her about the stereotypical social irritations of upper-middle-class women (e.g. "you have to keep yourself thin but not act like you care about being thin," "you have to be a confident leader but also be nurturing and supportive," etc.) [note that the Barbies of Barbieland have never encountered these irritations, at least not at the hands of men]. And the girlboss victory montage consists of having the Barbies put on deceptive manipulative bimbo acts to stroke the Kens' egos, which sure is one way to depict girlboss feminist victory.

But the most unforgivable thing of all is the depiction of the patriarchy-brainwashed Barbies. They're lad-magazine caricatures, endlessly offering their Kens "brewski beers," dressing up as French maids, gazing on in cow-eyed adoration as their Kens mansplain stuff to them.

Barbie does, in fact, have a problematic history with the patriarchy. And it does not look like that.

VIII

@brazenautomaton:

Barbie isn’t someone who had to fight through the patriarchy to be seen as good enough to be an astronaut even though she’s a woman. Barbie’s a fucking astronaut because she’s fucking Barbie of course she’s good enough to be an astronaut.

That is...one aspect of the deep Barbie lore. It is the Barbie-nature that Mattel was trying to push, as far back as my own childhood; it's certainly the Barbie-nature that Mattel is trying to push in this movie. But there is another side to Barbie, even older and even more fundamental than Senator Astronaut Veterinarian Barbie, and you can't make a postmodern movie-about-Barbie without addressing it.

This is Barbie the fashion doll. The Barbie who is an icon of ultra-consumerist teenage girlhood, whose life is defined by her fancy clothes and her fancy car. The Barbie whose most salient traits are her hourglass figure and her long blonde hair and her feet that are always posed to fit into high heels. The Barbie of "math class is tough!" The Barbie who is kinda vapid and shallow and, yes, boy-crazy.

How can you tell a story about Barbie wrestling with the culture of patriarchy, and not talk about that? How can you depict Barbie falling victim to the patriarchy and have it look nothing like that?

...the movie does bring up the specter of Vapid Consumerist Barbie, briefly. When Margot Robbie's Barbie first comes to the real world and meets with the sullen teenage daughter character, she has a litany of That Thing thrown in her face, and it makes her sad. But nothing is ever done with it, and it goes nowhere.

IX

And it could all have fit together so well. That's the hell of it.

You can imagine the version of the story in which Ken conquers Barbieland with patriarchy, because the Barbies are actually vulnerable to patriarchal narratives, because Vapid Consumerist Barbie is the chthonic serpent that gnaws at the foundations of Senator Astronaut Veterinarian Barbie civilization. He successfully makes them all forget that they're senators and astronauts and veterinarians, and turns them into airheaded teenage fashionistas who think that math class is tough.

And this avails him, and the other Kens, nothing. Even within the "patriarchal" version of Barbieland, Ken is still an afterthought and an appendage. He still gets treated like dogshit, just in a different idiom.

Because the thing that has always been true of Barbie, though every age and every phase of her mythos, is: she is the main character of her own story.

This is what the movie was telling us all the way back in the horrific 2001-pastiche prologue, right? Even when Barbie was just a swimsuit model, the point was that she let girls tell stories about themselves (or idealized/aspirational versions of themselves), not about boys or babies. That is a truer, and more powerful, feminist message about the meaning of Barbie than any message the movie actually bothers conveying.

The gag scene practically writes itself: the brainwashed Barbies are sitting around in a giggly slumber-party huddle talking about how dreamy Ken is, and actual Ken cannot get a word in edgewise, he can't even get them to notice he's there, because even Vapid Consumerist Barbie is fundamentally centered in her own life. Her narrative is not about a boy, it's about the experience of being a girl (mostly engaging with other girls) who likes thinking and talking about boys. Which is very much beside the point, if you started out with the complaint that your girlfriend never paid any attention to you.

Patriarchy hurts men too, indeed.

X

The movie ends, as I've intimated, in a disappointing squidge of thematic confusion. Barbie announces that she never really loved Ken, and leaves him, because...well, because these days the smart-set target audience is allergic to romantic narratives that Produce the Couple, as far as I can tell. Then she goes to the real world and becomes a real girl, a move that means nothing and is nonsensical even by the standards of the Barbie metaphysics, because the storytellers don't know how to end her arc and Becoming a Real Girl is the sort of thing that feels like a meaningful conclusion.

The Kens...sigh...the Kens ask for equal rights in Barbieland, more or less, and get told, "nah, but we'll throw you some bones." And they're happy with this, more or less, because they're dumb and don't really care. The narrator says, approximately, "maybe someday they'll make as much progress as women have in the real world." Haw haw.

It's probably too much to hope for a movie like this to be willing to say something substantive about responsibility and kindness in relationships. It's almost certainly too much to hope for a movie like this to be willing to say something about the nature of love symbols and love narratives. But all the pieces really were there, laid out very conspicuously. The movie could have wrapped up with: Ken doesn't need to be more important than Barbie, he doesn't even need to be as important as Barbie, he just needs to be treated with human decency. And if little girls are going to play with Barbies, and fantasize about having cute guys hanging all over them -- maybe they should have functional models of romance and human connection in which to root their fantasies, and not terrible ones.

502 notes

·

View notes