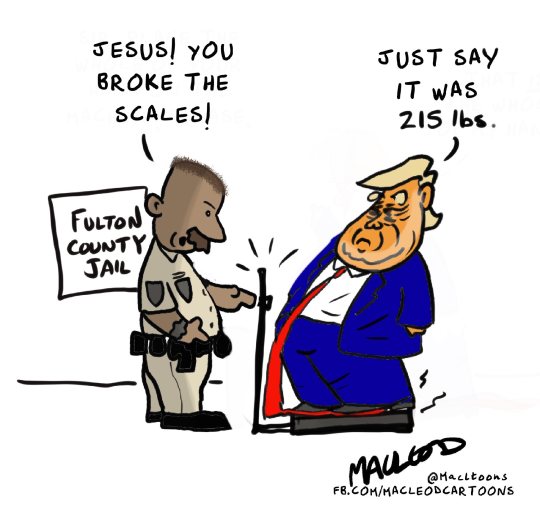

#2020 political cartoon

Text

#macleod cartoons#political cartoons#us politics#republicans#donald trump#conservatives#2023#Georgia election probe#fulton county#georgia#indictment#trump indictment#trump administration#2020 election

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

who up sinning their fest

#one of my worst recent hyperfixations i'll admit#and i dont even have an excuse like ohhh i used to read this back in the late 2000s before all the terf shit#no i got into it in late 2023 this school year cause i stumbled across the tvtropes page#and i was like 'sinfest'? isnt that the name of that terf Twitter comic? but the cover image showed a sick ass artstyle so i read it#and im just obsessed with it now its such a strange spectacle. its like a political cartoon and a newspaper comic at the same time#my fav era has gotta be late 2000s maybe early 2010s sinfest... hell maybe even mid 2010s sinfest if i ignore the sisterhood#now every strip is just about jewish people or calling trans women groomers#and almost every once-likable character is now canonically a terf and/or racist and/or antivaxxer etc#or theyre just not in the comic at all anymore like my dear criminy and fuschia#i hope we never get another appearance from them godbless#cause last time we saw criminy he was helping squig and slick break a terf out of she/her penitentiary. with fuschia's permission#theyre definitely the best part of 2010s sinfest. a bygone era#the best part of 2000s sinfest is the sharp artstyle and lil e just being evil#and the best part of 2020s sinfest seems to be. um. laughing at how ridiculous it is? its kind of hard to enjoy though.#i intend to stay updated on it because i like being able to say i've read all of sinfest start to finish#but man i gotta get an adblocker soon cause i read it on the official website cause idk how else to read it online and the ads are constant#really funny when ur reading a strip criticizing the prevalence of ads in our day to day life#not as funny when you remember tatsuya is probably making money off of them. so yeah im gonna install ublock#but the problem is i usually read it on my school computer to pass time. and that technically isnt my computer so i cant download ublock#anyways. i could ramble on about how much i love and hate and am obsessed w sinfest all day but heres some fanart of the characters.#id like to make my own headcanon version of sinfest aka sinfest if it was good#but headcanons arent enough... i need to kill tatsuya ishida#sinfest#squigley sinfest#monique sinfest#lil e sinfest#the devil sinfest#tangerine sinfest#images that are horrid to see and look at#mspaint

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

South Park The Worldwide Privacy Tour. Season 26, Episode 2; February 15, 2023.

#south park#comedy#pop#art#chaos#culture#satire#comics#illustration#art history#cartoon#humor#the worldwide privacy tour#the prince of canada and his wife#2020s#celebs#people#hipster#politics#lifestyle#👽

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

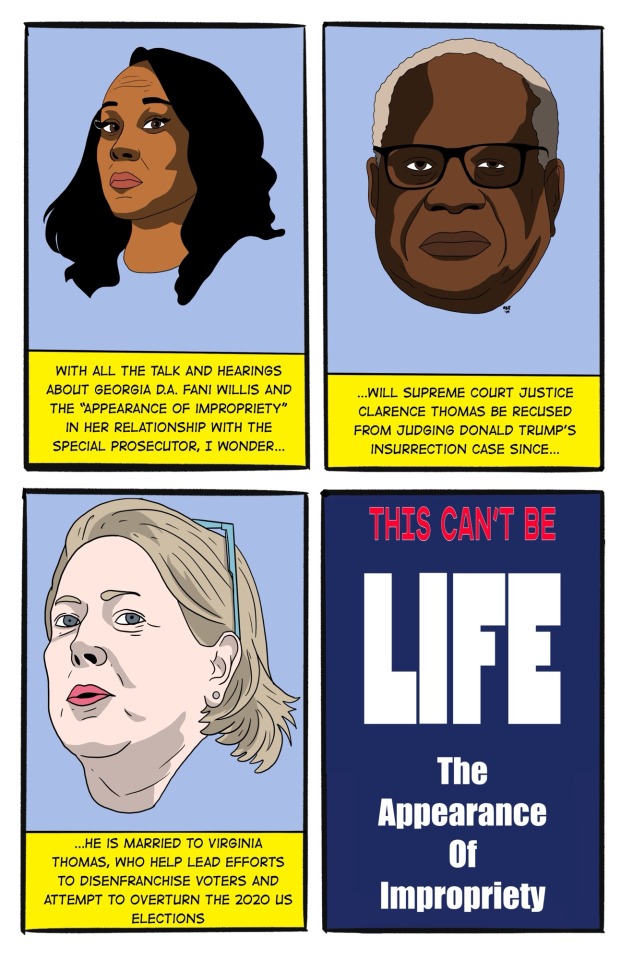

This Can’t Be Life - The Appearance of Impropriety

View On WordPress

#2020 election#Clarence Thomas#comic#con queso publishing#cq comics#district attorney#Donald Trump#fani willis#Georgia#ginni thomas#political cartoon#political memes#tcbl#This Cant Be Life#Trump#United States#us supreme court

0 notes

Text

In the first half century of his career, Robert Jay Lifton published five books based on long-term studies of seemingly vastly different topics. For his first book, “Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism,” Lifton interviewed former inmates of Chinese reëducation camps. Trained as both a psychiatrist and a psychoanalyst, Lifton used the interviews to understand the psychological—rather than the political or ideological—structure of totalitarianism. His next topic was Hiroshima; his 1968 book “Death in Life,” based on extended associative interviews with survivors of the atomic bomb, earned Lifton the National Book Award. He then turned to the psychology of Vietnam War veterans and, soon after, Nazis. In both of the resulting books—“Home from the War” and “The Nazi Doctors”—Lifton strove to understand the capacity of ordinary people to commit atrocities. In his final interview-based book, “Destroying the World to Save It: Aum Shinrikyo, Apocalyptic Violence, and the New Global Terrorism,” which was published in 1999, Lifton examined the psychology and ideology of a cult.

Lifton is fascinated by the range and plasticity of the human mind, its ability to contort to the demands of totalitarian control, to find justification for the unimaginable—the Holocaust, war crimes, the atomic bomb—and yet recover, and reconjure hope. In a century when humanity discovered its capacity for mass destruction, Lifton studied the psychology of both the victims and the perpetrators of horror. “We are all survivors of Hiroshima, and, in our imaginations, of future nuclear holocaust,” he wrote at the end of “Death in Life.” How do we live with such knowledge? When does it lead to more atrocities and when does it result in what Lifton called, in a later book, “species-wide agreement”?

Lifton’s big books, though based on rigorous research, were written for popular audiences. He writes, essentially, by lecturing into a Dictaphone, giving even his most ambitious works a distinctive spoken quality. In between his five large studies, Lifton published academic books, papers and essays, and two books of cartoons, “Birds” and “PsychoBirds.” (Every cartoon features two bird heads with dialogue bubbles, such as, “ ‘All of a sudden I had this wonderful feeling: I am me!’ ” “You were wrong.”) Lifton’s impact on the study and treatment of trauma is unparalleled. In a 2020 tribute to Lifton in the Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, his former colleague Charles Strozier wrote that a chapter in “Death in Life” on the psychology of survivors “has never been surpassed, only repeated many times and frequently diluted in its power. All those working with survivors of trauma, personal or sociohistorical, must immerse themselves in his work.”

Lifton was also a prolific political activist. He opposed the war in Vietnam and spent years working in the anti-nuclear movement. In the past twenty-five years, Lifton wrote a memoir—“Witness to an Extreme Century”—and several books that synthesize his ideas. His most recent book, “Surviving Our Catastrophes,” combines reminiscences with the argument that survivors—whether of wars, nuclear explosions, the ongoing climate emergency, COVID, or other catastrophic events—can lead others on a path to reinvention. If human life is unsustainable as we have become accustomed to living it, it is likely up to survivors—people who have stared into the abyss of catastrophe—to imagine and enact new ways of living.

Lifton grew up in Brooklyn and spent most of his adult life between New York City and Massachusetts. He and his wife, Betty Jean Kirschner, an author of children’s books and an advocate for open adoption, had a house in Wellfleet, on Cape Cod, that hosted annual meetings of the Wellfleet Group, which brought together psychoanalysts and other intellectuals to exchange ideas. Kirschner died in 2010. A couple of years later, at a dinner party, Lifton met the political theorist Nancy Rosenblum, who became a Wellfleet Group participant and his partner. In March, 2020, Lifton and Rosenblum left his apartment on the Upper West Side for her house in Truro, Massachusetts, near the very tip of Cape Cod, where Lifton, who is ninety-seven, continues to work every day. In September, days after “Surviving Our Catastrophes” was published, I visited him there. The transcript of our conversations has been edited for length and clarity.

I would like to go through some terms that seem key to your work. I thought I’d start with “totalism.”

O.K. Totalism is an all-or-none commitment to an ideology. It involves an impulse toward action. And it’s a closed state, because a totalist sees the world through his or her ideology. A totalist seeks to own reality.

And when you say “totalist,” do you mean a leader or aspiring leader, or anyone else committed to the ideology?

Can be either. It can be a guru of a cult, or a cult-like arrangement. The Trumpist movement, for instance, is cult-like in many ways. And it is overt in its efforts to own reality, overt in its solipsism.

How is it cult-like?

He forms a certain kind of relationship with followers. Especially his base, as they call it, his most fervent followers, who, in a way, experience high states at his rallies and in relation to what he says or does.

Your definition of totalism seems very similar to Hannah Arendt’s definition of totalitarian ideology. Is the difference that it’s applicable not just to states but also to smaller groups?

It’s like a psychological version of totalitarianism, yes, applicable to various groups. As we see now, there’s a kind of hunger for totalism. It stems mainly from dislocation. There’s something in us as human beings which seeks fixity and definiteness and absoluteness. We’re vulnerable to totalism. But it’s most pronounced during times of stress and dislocation. Certainly Trump and his allies are calling for a totalism. Trump himself doesn’t have the capacity to sustain an actual continuous ideology. But by simply declaring his falsehoods to be true and embracing that version of totalism, he can mesmerize his followers and they can depend upon him for every truth in the world.

You have another great term: “thought-terminating cliché.”

Thought-terminating cliché is being stuck in the language of totalism. So that any idea that one has that is separate from totalism is wrong and has to be terminated.

What would be an example from Trumpism?

The Big Lie. Trump’s promulgation of the Big Lie has surprised everyone with the extent to which it can be accepted and believed if constantly reiterated.

Did it surprise you?

It did. Like others, I was fooled in the sense of expecting him to be so absurd that, for instance, that he wouldn’t be nominated for the Presidency in the first place.

Next on my list is “atrocity-producing situation.”

That’s very important to me. When I looked at the Vietnam War, especially antiwar veterans, I felt they had been placed in an atrocity-producing situation. What I meant by that was a combination of military policies and individual psychology. There was a kind of angry grief. Really all of the My Lai massacre could be seen as a combination of military policy and angry grief. The men had just lost their beloved older sergeant, George Cox, who had been a kind of father figure. He had stepped on a booby trap. The company commander had a ceremony. He said, “There are no innocent civilians in this area.” He gave them carte blanche to kill everyone. The eulogy for Sergeant Cox combined with military policy to unleash the slaughter of My Lai, in which almost five hundred people were killed in one morning.

You’ve written that people who commit atrocities in an atrocity-producing situation would never do it under different circumstances.

People go into an atrocity-producing situation no more violent, or no more moral or immoral, than you or me. Ordinary people commit atrocities.

That brings us to “malignant normality.”

It describes a situation that is harmful and destructive but becomes routinized, becomes the norm, becomes accepted behavior. I came to that by looking at malignant nuclear normality. After the Second World War, the assumption was that we might have to use the weapon again. At Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, a group of faculty members wrote a book called “Living with Nuclear Weapons.” There was a book by Joseph Nye called “Nuclear Ethics.” His “nuclear ethics” included using the weapon. Later there was Star Wars, the anti-missile missiles which really encouraged first-strike use. These were examples of malignant nuclear normality. Other examples were the scenarios by people like [the physicists] Edward Teller and Herman Kahn in which we could use the weapons and recover readily from nuclear war. We could win nuclear wars.

And now, according to the Doomsday Clock, we’re closer to possible nuclear disaster than ever before. Yet there doesn’t seem to be the same sense of pervasive dread that there was in the seventies and eighties.

I think in our minds apocalyptic events merge. I see parallels between nuclear and climate threats. Charles Strozier and I did a study of nuclear fear. People spoke of nuclear fear and climate fear in the same sentence. It’s as if the mind has a certain area for apocalyptic events. I speak of “climate swerve,” of growing awareness of climate danger. And nuclear awareness was diminishing. But that doesn’t mean that nuclear fear was gone. It was still there in the Zeitgeist and it’s still very much with us, the combination of nuclear and climate change, and now COVID, of course.

How about “psychic numbing”?

Psychic numbing is a diminished capacity or inclination to feel. One point about psychic numbing, which could otherwise resemble other defense mechanisms, like de-realization or repression: it only is concerned with feeling and nonfeeling. Of course, psychic numbing can also be protective. People in Hiroshima had to numb themselves. People in Auschwitz had to numb themselves quite severely in order to get through that experience. People would say, “I was a different person in Auschwitz.” They would say, “I simply stopped feeling.” Much of life involves keeping the balance between numbing and feeling, given the catastrophes that confront us.

A related concept that you use, which comes from Martin Buber, is “imagining the real.”

It’s attributed to Martin Buber, but as far as I can tell, nobody knows exactly where he used it. It really means the difficulty in taking in what is actual. Imagining the real becomes necessary for imagining our catastrophes and confronting them and for that turn by which the helpless victim becomes the active survivor who promotes renewal and resilience.

How does that relate to another one of your concepts, nuclearism?

Nuclearism is the embrace of nuclear weapons to solve various human problems and the commitment to their use. I speak of a strange early expression of nuclearism between Oppenheimer and Niels Bohr, who was a great mentor of Oppenheimer. Bohr came to Los Alamos. And they would have abstract conversations. They had this idea that nuclear weapons could be both a source of destruction and havoc and a source of good because their use would prevent any wars in the future. And that view has never left us. Oppenheimer never quite renounced it, though, at other times, he said he had blood on his hands—in his famous meeting with Truman.

Have you seen the movie “Oppenheimer”?

Yes. I thought it was a well-made film by a gifted filmmaker. But it missed this issue of nuclearism. It missed the Bohr-Oppenheimer interaction. And worst of all, it said nothing about what happened in Hiroshima. It had just a fleeting image of his thinking about Hiroshima. My view is that his success in making the weapon was the source of his personal catastrophe. He was deeply ambivalent about his legacy. I’m very sensitive to that because that was how I got to my preoccupation with Oppenheimer: through having studied Hiroshima, having lived there for six months, and then asking myself, What happened on the other side of the bomb—the people who made it, the people who used it? They underwent a kind of numbing. It’s also true that Oppenheimer, in relationship to the larger hydrogen bombs, became the most vociferous critic of nuclearism. That’s part of his story. The moral of Oppenheimer’s story is that we need abolition. That’s the only human solution.

By abolition, you mean destruction of all existing weapons?

Yes, and not building any new ones.

Have you been following the war in Ukraine? Do you see Putin as engaging in nuclearism?

I do. He has a constant threat of using nuclear weapons. Some feel that his very threat is all that he can do. But we can’t always be certain. I think he is aware of the danger of nuclear weapons to the human race. He has shown that awareness, and it has been expressed at times by his spokesman. But we can’t ever fully know. His emotions are so otherwise extreme.

There’s a messianic ideology in Russia. And the line used on Russian television is, “If we blow up the world, at least we will go straight to Heaven. And they will just croak.”

There’s always been that idea with nuclearism. One somehow feels that one’s own group will survive and others will die. It’s an illusion, of course, but it’s one of the many that we call forth in relation to nuclear danger.

Are you in touch with any of your former Russian counterparts in the anti-nuclear movement?

I’ve never entirely left the anti-nuclear movements. I’ve been particularly active in Physicians for Social Responsibility. We had meetings—or bombings, as we used to call it—in different cities in the country, describing what would happen if a nuclear war occurred. We had a very simple message: we’re physicians and we’d like to be able to patch you up after this war, but it won’t really be possible because all medical facilities will be destroyed, and probably you’ll be dead, and we’ll be dead. We did the same internationally with the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, which won the Nobel Peace Prize. There’s a part of the movement that’s not appreciated sufficiently. [Yevgeny] Chazov, who was the main Soviet representative, was a friend of Gorbachev’s, and he was feeding Gorbachev this view of common security. And Gorbachev quickly took on the view of nuclear weapons that we had. There used to be a toast: either an American or a Soviet would get up and say, “I toast you and your leaders and your people. And your survival, because if you survive, we survive. And if you die, we die.”

Let’s talk about proteanism.

Proteanism is, of course, named after the notorious shape-shifter Proteus. It suggests a self that is in motion, that is multiple rather than made up of fixed ideas, and changeable and can be transformed. There is an ongoing struggle between proteanism and fixity. Proteanism is no guarantee of achievement or of ridding ourselves of danger. But proteanism has more possibility of taking us toward a species mentality. A species mentality means that we are concerned with the fate of the human species. Whenever we take action for opposing climate change, or COVID, or even the threat to our democratic procedure, we’re expressing ourselves on behalf of the human species. And that species-self and species commitment is crucial to our emergence from these dilemmas.

Next term: “witnessing professional.”

I went to Hiroshima because I was already anti-nuclear. When I got there, I discovered that, seventeen years after the bomb was dropped, there had been no over-all, inclusive study of what happened to that city and to groups of people in it. I wanted to conduct a scientific study, having a protocol and asking everyone similar questions—although I altered my method by encouraging them to associate. But I also realized that I wanted to bear witness to what happened to that city. I wanted to tell the world. I wanted to give a retelling, from my standpoint, as a psychological professional, of what happened to that city. That was how I came to see myself as a witnessing professional. It was to be a form of active witness. There were people in Hiroshima who embodied the struggle to bear witness. One of them was a historian who was at the edge of the city who said, “I looked down and saw that Hiroshima had disappeared.” That image of the city disappearing took hold in my head and became central to my life afterward. And the image that kept reverberating in my mind was, one plane, one bomb, one city. I was making clear—at least to myself at first and then, perhaps, to others,—that bearing witness and taking action was something that we needed from professionals and others.

I have two terms left on my list. One is “survivor.”

There is a distinction I make between the helpless victim and the survivor as agent of change. At the end of my Hiroshima book, I had a very long section describing the survivor. Survivors of large catastrophes are quite special. Because they have doubts about the continuation of the human race. Survivors of painful family loss or the loss of people close to them share the need to give meaning to that survival. People can claim to be survivors if they’re not; survivors themselves may sometimes take out their frustration on people immediately around them. There are all kinds of problems about survivors. Still, survivors have a certain knowledge through what they have experienced that no one else has. Survivors have surprised me by saying such things as “Auschwitz was terrible, but I’m glad that I could have such an experience.” I was amazed to hear such things. Of course, they didn’t really mean that they enjoyed it. But they were trying to say that they realized they had some value and some importance through what they had been through. And that’s what I came to think of as survivor power or survivor wisdom.

Do you have views on contemporary American usage of the words “survivor” and “victim”?

We still struggle with those two terms. The Trumpists come to see themselves as victims rather than survivors. They are victims of what they call “the steal.” In seeing themselves as victims, they take on a kind of righteousness. They can even develop a false survivor mission, of sustaining the Big Lie.

The last term I have on my list is “continuity of life.”

When I finished my first study, I wanted a theory for what I had done, so to speak. [The psychoanalyst] Erik Erikson spoke of identity. I could speak of Chinese Communism as turning the identity of the Chinese filial son into the filial Communist. But when it came to Hiroshima, Erikson didn’t have much to say in his work about the issue of death. I realized I had to come to a different idea set, and it was death and the continuity of life. In Hiroshima, I really was confronted with large-scale death—but also the question of the continuity of life, as victims could transform themselves into survivors.

Like some of your other ideas, this makes me think of Arendt’s writing. Something that was important to her was the idea that every birth is a new beginning, a new political possibility. And, relatedly, what stands between us and the triumph of totalitarianism is “the supreme capacity of man” to invent something new.

I think she’s saying there that it’s the human mind that does all this. The human mind is so many-sided and so surprising. And at times contradictory. It can be open to the wildest claims that it itself can create. That has been a staggering recognition. The human self can take us anywhere and everywhere.

Let me ask you one more Arendt question. Is there a parallel between your concept of “malignant normality” and her “banality of evil”?

There is. When Arendt speaks of the “banality of evil,” I agree—in the sense that evil can be a response to an atrocity-producing situation, it can be performed by ordinary people. But I would modify it a little bit and say that after one has been involved in committing evil, one changes. The person is no longer so banal. Nor is the evil, of course.

Your late wife, B.J., was a member of the Wellfleet Group. Your new partner, Nancy Rosenblum, makes appearances in your new book. Can I ask you to talk about combining your romantic, domestic, and intellectual relationships?

In the case of B.J., she was a kind of co-host with me to the meetings for all those fifty years and she had lots of intellectual ideas of her own, as a reformer in adoption and an authority on the psychology of adoption. And in the case of Nancy Rosenblum, as you know, she’s a very accomplished political theorist. She came to speak at Wellfleet. She gave a very humorous talk called “Activist Envy.” She had always been a very progressive theorist and has taken stands but never considered herself an activist, whereas just about everybody at the Wellfleet meeting combined scholarship and activism.

People have been talking more about love in later life. It’s very real, and it’s a different form of love, because, you know, one is quite formed at that stage of life. And perhaps has a better knowledge of who one is. And what a relationship is and what it can be. But there’s still something called love that has an intensity and a special quality that is beyond the everyday, and it actually has been crucial to me and my work in the last decade or so. And actually, I’ve been helpful to Nancy, too, because we have similar interests, although we come to them from different intellectual perspectives. We talk a lot about things. That’s been a really special part of my life for the last decade. On the other hand, she’s also quite aware of my age and situation. The threat of death—or at least the loss of capacity to function well—hovers over me. You asked me whether I have a fear of death. I’m sure I do. I’m not a religious figure who has transcended all this. For me, part of the longevity is a will to live and a desire to live. To continue working and continue what is a happy situation for me.

You’re about twenty years older than Nancy, right?

Twenty-one years older.

So you are at different stages in your lives.

Very much. It means that she does a lot of things, with me and for me, that enable me to function. It has to do with a lot of details and personal help. I sometimes get concerned about that because it becomes very demanding for her. She’s now working on a book on ungoverning. She needs time and space for that work.

What is your work routine? Are you still seeing patients?

I don’t. Very early on, I found that even having one patient, one has to be interested in that patient and available for that patient. It somehow interrupted my sense of being an intense researcher. So I stopped seeing patients quite a long time ago. I get up in the morning and have breakfast. Not necessarily all that early. I do a lot of good sleeping. Check my e-mails after breakfast. And then pretty much go to work at my desk at nine-thirty or ten. And stay there for a couple of hours or more. Have a late lunch. Nap, at some point. A little bit before lunch and then late in the day as well. I can close my eyes for five minutes and feel restored. I learned that trick from my father, from whom I learned many things. I’m likely to go back to my desk after lunch and to work with an assistant. My method is sort of laborious, but it works for me. I dictate the first few drafts. And then look at it on the computer and correct it, and finally turn it into written work.

I can’t drink anymore, unfortunately. I never drank much, but I used to love a Scotch before dinner or sometimes a vodka tonic. Now I drink mostly water or Pellegrino. We will have that kind of drink at maybe six o’clock and maybe listen to some news. These days, we get tired of the news. But a big part of my routine is to find an alternate universe. And that’s sports. I’m a lover of baseball. I’m still an avid fan of the Los Angeles Dodgers, even though they moved from Brooklyn to Los Angeles in 1957. You’d think that my protean self would let them go. Norman Mailer, who also is from Brooklyn, said, “They moved away. I say, ‘Fuck them.’ ” But there’s a deep sense of loyalty in me. I also like to watch football, which is interesting, because I disapprove of much football. It’s so harmful to its participants. So, it’s a clear-cut, conscious contradiction. It’s also a very interesting game, which has almost a military-like arrangement and shows very special skills and sudden intensity.

Is religion important to you?

I don’t have any formal religion. And I really dislike most religious groups. When I tried to arrange a bar mitzvah for my son, all my progressive friends, rabbis or not, somehow insisted you had to join a temple and participate. I didn’t. I couldn’t do any of those things. He never was bar mitzvah. But in any case, I see religion as a great force in human experience. Like many people, I make a distinction between a certain amount of spirituality and formal religion. One rabbi friend once said to me, “You’re more religious than I am.” That had to do with intense commitments to others. I have a certain respect for what religion can do. We once had a distinguished religious figure come to our study to organize a conference on why religion can be so contradictory. It can serve humankind and their spirit and freedom and it can suppress their freedom. Every religion has both of those possibilities. So, when there is an atheist movement, I don’t join it because it seems to be as intensely anti-religious as the religious people are committed to religion. I’ve been friendly with [the theologian] Harvey Cox, who was brought up as a fundamentalist and always tried to be a progressive fundamentalist, which is a hard thing to do. He would promise me every year that the evangelicals are becoming more progressive, but they never have.

Can you tell me about the Wellfleet Group? How did it function?

The Wellfleet Group has been very central to my life. It lasted for fifty years. It began as an arena for disseminating Erik Erikson’s ideas. When the building of my Wellfleet home was completed, in the mid-sixties, it included a little shack. We put two very large oak tables at the center of it. Erik and I had talked about having meetings, and that was immediately a place to do it. So the next year, in ’66, we began the meetings. I was always the organizer, but Erik always had a kind of veto power. You didn’t want anybody who criticized him in any case. And then it became increasingly an expression of my interests. I presented my Hiroshima work there and my work with veterans and all kinds of studies. Over time, the meetings became more activist. For instance, in 1968, right after the terrible uprising [at the Democratic National Convention] that was so suppressed, Richard Goodwin came and described what happened.

Under my control, the meeting increasingly took up issues of war and peace. And nuclear weapons. I never believed that people with active antipathies should get together until they recognize what they have in common. I don’t think that’s necessarily productive or indicative. I think one does better to surround oneself with people of a general similarity in world view who sustain one another in their originality. The Wellfleet meetings became a mixture of the academic and non-academic in the usual sense of that word. But also a sort of soirée, where all kinds of interesting minds could exchange thoughts. We would meet once a year, at first for a week or so and then for a few days, and they were very intense. And then there was a Wellfleet meeting underground, where, when everybody left the meeting, whatever it was—nine or ten at night—they would drink at local motels, where they stayed, and have further thoughts, though I wasn’t privy to that.

How many people participated?

This shack could hold as many as forty people. We ended them after the fiftieth year. We were all getting older, especially me. But then, even after the meetings ended, we had luncheons in New York, which we called Wellfleet in New York, or luncheons in Wellfleet, which we called Wellfleet in Wellfleet. You asked whether I miss them. I do, in a way. But it’s one of what I call renunciations, not because I want to get rid of them but because a moment in life comes when you must get rid of them, just as I had to stop playing tennis eventually. I played tennis from my twenties through my sixties. Certainly, the memories of them are very important to me. I remember moments from different meetings, but also just the meetings themselves, because, perhaps, the communal idea was as important as any.

Do you find it easy to adjust to your physical environment? This was Nancy’s place?

Yes, this is Nancy’s place. Much more equipped for the Cape winters and just a more solid house. For us to do all the things, including medical things she helps me with, this house was much more suitable. Even the walk between the main house and my study [in Wellfleet] required effort. So we’ve been living here now for about four years. And we’ve enjoyed it. Of course, the view helps. I wake up every morning and look out to kind of take stock. What’s happening? Is it sunny or cloudy? What boats are visible? And then we go on with the day.

In the new book, you praise President Biden and Vice-President Harris for their early efforts to commemorate people who had died of COVID. Do you feel that is an example of the sort of sustained narrative that you say is necessary?

It’s hard to create the collective mourning that COVID requires. Certainly, the Biden Administration, right at its beginning, made a worthwhile attempt to do that, when they lit those lights around the pool near the Lincoln Memorial, four hundred of them, for the four hundred thousand Americans who had died. And then there was another ceremony. And they encouraged people to put candles in their windows or ring bells, to make it participatory. But it’s hard to sustain that. There are proposals for a memorial for COVID. It’s hard to do and yet worth trying.

You observe that the 1918 pandemic is virtually gone from memory.

That’s an amazing thing. Fifty million people. The biggest pandemic anywhere ever. And almost no public commemoration of it. When COVID came along, there wasn’t a model which could have perhaps served as some way of understanding. They used similar forms of masks and distancing. But there was no public remembrance of it.

Some scholars have suggested that it’s because there are no heroes and no villains, no military-style imagery to rely on to create a commemoration.

Well, that’s true. It’s also in a way true of climate. And yet there are survivors of it. And they have been speaking out. They form groups. Groups called Long COVID SOS or Widows of COVID-19 or COVID Survivors for Change. They have names that suggest that they are committed to telling the society about it and improving the society’s treatment of it.

Your book “The Climate Swerve,” published in 2017, seemed very hopeful. You wrote about the beginning of a species-wide agreement. Has this hope been tempered?

I don’t think I’m any less hopeful than I was when I wrote “The Climate Swerve.” In my new book [“Surviving Our Catastrophes”], the hope is still there, but the focus is much more on survivor wisdom and survivor power. In either case, I was never completely optimistic—but hopeful that there are these possibilities.

There’s something else I’d like to mention that’s happened in my old age. I’ve had a long interaction with psychoanalysis. Erik Erikson taught me how to be ambivalent about psychoanalysis. It was a bigger problem for him, in a way, because he came from it completely and yet turned against its fixity when it was overly traditionalized. In my case, I knew it was important, but I also knew it could be harmful because it was so traditionalized. I feared that my eccentric way of life might be seen as neurotic. But now, in my older age, the analysts want me. A couple of them approached me a few years ago to give the keynote talk at a meeting on my work. I was surprised but very happy to do it. They were extremely warm as though they were itching to, in need of, bringing psychoanalysis into society, and recognizing more of the issues that I was concerned with, having to do with totalism and fixity. Since then, they’ve invited me to publish in their journal. It’s satisfying, because psychoanalysis has been so important for my formation.

What was it about your life style that you thought your analyst would be critical of?

I feared that they would see that somebody who went out into the world and interviewed Chinese students and intellectuals or Western European teachers and diplomats and scholars was a little bit eccentric, or even neurotic.

The fact that you were interviewing people instead of doing pure academic research?

Yes, that’s right. A more “normal” life might have been to open up an office on the Upper West Side to see psychoanalytical, psychotherapeutic patients. And to work regularly with the psychoanalytic movement. I found myself seeking a different kind of life.

Tell me about the moment when you decided to seek a different kind of life.

In 1954, my wife and I had been living in Hong Kong for just three months, and I’d been interviewing Chinese students and intellectuals, and Western scholars and diplomats, and China-watchers and Westerners who had been in China and imprisoned. I was fascinated by thought reform because it was a coercive effort at change based on self-criticism and confession. I wanted to stay there, but at that time, I had done nothing. I hadn’t had my psychiatric residency and I hadn’t entered psychoanalytic training. Also, my money was running out. My wife, B.J., was O.K. either way. I walked through the streets thinking about it and wondering, and I came back after a long walk through Hong Kong and said, “Look, we just can’t stay. I don’t see any way we can.” But the next day, I was asking her to help type up an application for a local research grant that would enable me to stay. It was a crucial decision because it was the beginning of my identity as a psychiatrist in the world.

You have been professionally active for seventy-five years. This allows you to do something almost no one else on the planet can do: connect and compare events such as the Second World War, the Korean War, the nuclear race, the climate crisis, and the COVID pandemic. It’s a particularly remarkable feat during this ahistorical moment.

Absolutely. But in a certain sense, there’s no such thing as an ahistorical time. Americans can seem ahistorical, but history is always in us. It helps create us. That’s what the psychohistorical approach is all about. For me to have that long flow of history, yes, I felt, gave me a perspective.

You called the twentieth century “an extreme century.” What are your thoughts on the twenty-first?

The twentieth century brought us Auschwitz and Hiroshima. The twenty-first, I guess, brought us Trump. And a whole newly intensified right wing. Some call it populism. But it’s right-wing fanaticism and violence. We still have the catastrophic threats. And they are now sustained threats. There have been some writers who speak of all that we achieved over the course of the twentieth century and the first decades of the twenty-first century. And that’s true. There are achievements in the way of having overcome slavery and torture—for the most part, by no means entirely, but seeing it as bad. Having created institutions that serve individuals. But our so-called better angels are in many ways defeated by right-wing fanaticism.

If you could still go out and conduct interviews, what would you want to study?

I might want to study people who are combating fanaticism and their role in institutions. And I might also want to study people who are attracted to potential violence—not with the hope of winning them over but of further grasping their views. That was the kind of perspective from which I studied Nazi doctors. I’ve interviewed people both of a kind I was deeply sympathetic to and of a kind I was deeply antagonistic toward.

Is there anything I haven’t asked you about?

I would say something on this idea of hope and possibility. My temperament is in the direction of hopefulness. Sometimes, when Nancy and I have discussions, she’s more pessimistic and I more hopeful with the same material at hand. I have a temperament toward hopefulness. But for me to sustain that hopefulness, I require evidence. And I seek that evidence in my work.

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything is connected to everything, here's how

In 1979, the CIA began Operation Cyclone as a response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, which funded and trained the Mujahideen, who were fighting back against the Soviets. A Saudi Arabian millionaire also helped fund and train the Mujahideen. This man was Osama bin Laden, and he would go on to found Al-Qaeda and perpetrate the 9/11 attacks.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, a man walked into his internship at Cartoon Network when he witnessed the Twin Towers fall. He used music to help deal with the trauma and got to founding a band. The man was Gerard Way and the band was My Chemical Romance.

MCR got popular enough that it grabbed the attention of Mormon housewife Stephanie Meyer, who had a dream about a sparkly vampire, who she named Edward Cullen, thus kicking off the Twilight series.

Meanwhile, E. L. James made a Twilight fanfiction called Master of the Universe, which was adapted into a book trilogy called 50 Shades of Grey, and that eventually got a movie deal starring Dakota Johnson in her breakout role.

Dakota Johnson was confronted on the Ellen Show, hosted by Ellen DeGeneres, for not being invited to her 29th birthday party, and Dakota made sure to invite her for her 30th birthday party. However, Ellen never attended the party and instead went to a Dallas Cowboys game with George W. Bush, circling it all back to 9/11. And when Dakota had been invited onto the Ellen Show again, she called Ellen out for not going to her birthday party, and this sparked investigations that revealed the toxic work environment and how Ellen DeGeneres treated her guests and staff. This caused the show to run for a 19th and final season. This is how the CIA is connected to the downfall of Ellen DeGeneres.

There is also the story of how the 2007-08 writer's strike caused Georgia to go blue in 2020, and this may be a wilder ride.

The writer's strike of 2007-08 caused the TV series Supernatural to lose 6 episodes of the back half of its third season, which caused Dean to go to hell due to the show being written into a corner. However, at the beginning of the fourth season, Castiel was introduced, and his profound bond with Dean which saved the latter from perdition caused both a ludicrous amount of unhinged fanfictions and 11 more seasons of Supernatural to be made.

Meanwhile in 2018, Stacey Abrams, a fan of Supernatural, founded the grassroots organization Fair Fight, which helped to end voter suppression in Georgia. This and increased voter turnout was largely credited to Joe Biden securing Georgia in the 2020 election by less than 12,000 votes. However, Stacey Abrams credited this success to being able to calm down after watching Supernatural. And in a beautiful stroke of kismet, Destiel culminated on November 5, 2020, while Georgia was still counting votes.

One more example I want to share is how Star Trek is connected to Obama's election in 2008.

In the 90s, Star Trek: Voyager was not doing too well critically, so the writers introduced a new character played by actress Jeri Ryan, called Seven of Nine. Jeri was married to a prominent politician and Illinois state senator named Jack Ryan, and the juicy details of their eventual divorce in 1999 caused Jack Ryan to lose his chance of getting a US Senate seat in 2004 and get someone else to fill in the Republican candidacy for the Senate election. That someone was former MSNBC host Alan Keyes, who was defeated in a landslide vote by the Democratic candidate Barack Obama. This allowed Obama to get a prominent political position, which ensured his victory in the 2008 presidential election.

Everything is connected to everything.

#butterfly effect#domino effect#destiel#ellen degeneres#mcr#50 shades of gray#supernatural#twilight#history#star trek#politics

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

This political cartoon by Louis Dalrymple appeared in Judge magazine in 1903. It depicts European immigrants as rats. Nativism and anti-immigration have a long and sordid history in the United States

* * * * *

How foreign immigrants support the US economy

During my meetings with readers across the nation, the issue of immigration is frequently raised as a concern. It was a topic of conversation in my meeting on Saturday with readers in San Antonio. (See photo below.) After I made my usual remarks about why foreign immigration is good for the US, a reader suggested that I include the facts in my newsletter. So, here they are:

According to recent reports by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, foreign immigrants have fueled the better-than-expected performance of the US economy over the last decade. See Forbes, How Immigrants Are Boosting U.S. Economic And Job Growth. As summarized in the Forbes article,

In 2023, “foreign-born” workers comprised nearly 19% of the U.S. labor force . . . This is an uptick from 15.3% in 2006.

Immigrants have contributed largely to consumer spending growth by about 0.2 percentage point last year, with a similar boost expected this year, along with an increase in gross domestic product—a measure of all the goods and services produced—by 0.1 percentage point per year since 2022 . . . .

Federal Reserve Bank chair Jerome Powell [said], [I] t's just reporting the facts to say that immigration and labor force participation both contributed to the very strong economic output growth that we had last year.”

Immigration is fueling business and job creation in the U.S. According to MIT research, immigrants are 80% more likely to start a business than native-born U.S. citizens. They are also responsible for 42% more job creation than native-born founders.

So, larger-than-expected foreign immigration has increased consumer spending, GDP, start-up ventures, and job creation. That’s all good.

And there is a downside to restricting foreign immigration:

The U.S. needs more workers to keep the economy humming. In the absence of foreign-born labor, the U.S. talent pool will continue to decline because of lower birth rates with an accompanying aging workforce of Baby Boomers looking to retire.

Indeed, according to a US Census Bureau report, the US population would decrease (to 319 million) instead of growing (to 404 million) by 2060 if the US cut-off immigration. Under a “zero immigration” policy, the percentage of the population over 65 would increase from 15% in 2024 to 26% in 2060—not a good trend. In its starkest terms, immigration is necessary to guarantee a robust, growing labor force to drive the largest economy in the world.

But there’s more. Over the last decade, foreign immigration has saved nine US states from an absolute decline in population. The NYTimes reported on the findings of the 2020 Census in an article entitled, Why Your State Is Growing or Stalling or Shrinking.

Even with foreign immigration, four states lost population overall, including West Virginia and Illinois. Moreover, foreign immigration saved nine additional states from a shrinking population base—including Mississippi, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Michigan.

The debate about population growth is complicated. But in the short term, unplanned depopulation is devastating to economies and communities. To see the effects of a shrinking population and dwindling labor force, we need only look at many communities across America where young families are moving out, retirees are aging in place, and restrictive immigration policies discourage foreign immigrants from entering the workforce.

Conversely, states on the “front line” of foreign immigration into the US have booming economies—including California, Texas, Arizona, and Florida.

This interactive map will allow you to compare the economic impact of immigration on the respective states. As a point of comparison, California is the fifth largest economy in the world. 26% of its population consists of foreign immigrants, who contribute $137 billion in annual taxes, control $351 billion in spending power, and include 780,000 entrepreneurs. West Virginia’s population is 1.6% foreign immigrants who contribute $324 million in taxes and control $880 million in spending power. There are no recorded immigrant entrepreneurs in West Virginia.

Check out your own state on the interactive map.

Is our immigration system broken? Absolutely! But let’s not conflate the broken immigration system with the fact that America is strong (in part) because of immigration and will remain strong (in part) because of immigration. Foreign immigrants make America a better, more productive, and more innovative nation. Let’s not lose sight of that truth in the debate over how we allow foreign immigrants to enter the US.

[Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter]

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#us politics#political cartoons#drawings#art#2022#2020 election#republicans be like#conservatives be like#abolish the electoral college#electoral college#gerrymandering#land doesn't vote people do#trump lost#popular vote#trump supporters#fuck trump supporters#@breadpanes

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

^^^ That cartoon indirectly reminds me that we're nearing the 4th anniversary of Trump's terribly botched response to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

All those MAGA zombies who wax nostalgic about what a golden age the Trump administration was conveniently forget about everything that happened after January of 2020; that includes the Trump recession and the need for stimulus payments which led to a spike in inflation.

As for legal immunity, Trump is making the case that a president could order the assassination of a political rival. Seriously.

US president could have a rival assassinated and not be criminally prosecuted, Trump’s lawyer argues

If the courts bizarrely rule in Trump's favor on that, there's nothing legally to stop President Biden from ordering a drone strike on Mar-a-Lago. 😆

#donald trump#presidential immunity#trump's legal problems#the rule of law#assassination of rivals#covid-19#trump's botched response to the pandemic#register and vote#vote blue no matter who#election 2024#rick mckee

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I have three criticisms about the fandom:

1. Why tf do people call Marinette a creepy stalker? They do realize she’s 14 right? She’s a young girl with a crush, not some s*x offender.

2. I don’t get why there are fights over the Lovesquare when it’s literally the same two people. At the end of the day, it’s the same fucking dynamic.

3. The way this fandom treats the creator like he owes them something is absolutely disgusting. They act like a bunch of self-important, entitled karens.

1. People forget what it's like to be a teenager with a crush. That and there is a trend in fandoms as of late that exercises this black and white thinking pattern. Either something is so morally pure and devoid of any wrongdoing or it's completely problematic and anyone that enjoys or consumes it is just enabling harmful narratives. There's no room for nuance. ML is written by someone who grew up watching old, old superhero cartoons and watching old, old superhero comics. That's evident in a lot of jokes and references and tropes that they use. The creator himself worked on several shows in the early 2000s, and you can see evidence of that time period in ML. While that objectively wasn't that long ago, the early 2000s were a much different time on TV. The teen girl practically basing her whole identity around being in love with her crush was a common trope around that time (see: Helga from Hey Arnold. Seriously yall Marinette ain't got nothing on Helga and her motherfucking chewed gum shrine shaped like Arnold's head). A lot of her behavior is meant to be exaggerated for the joke (as was Helga's). That's just how things were. 🤷♀️ But some people, especially if they didn't grow up in that era watching those types of shows or if they're not as socially competent and can't understand hyperbole, then that's likely where the Marinette is a stalker thing comes from. Also can have a lot to do with mob mentality. Someone people deem cool or smart says it once, so a bunch of underlings follow without actually thinking about whether it's objectively true or bothering to question it. It's a problem in society at large (I mean look at the American political system, or any political system rn honestly)

2. You and me both, nonny. Yet every time I go into the ladrien tag to find content to queue for ladrien Wednesday, I scroll past at least 3 "ranking the love square sides" posts and ladrien is always at the bottom because of some arbitrary, made up, noncanon reason that they've convinced themselves is true. I've said for years people just need to watch the show with their eyes open and employ at least a single brain cell, maybe go outside and touch some grass, talk to real people. Just as a start. 🤷♀️

3. That's not exclusive to ML sadly. People have been harassing creators and musicians for years. Not to be a Swiftie on main, but Taylor has put out 5 albums since 2020. And that's still not enough for some of her fans. People are still demanding she announce her next rerecord rather than just sitting and enjoying all of the shit she's already given us. Entitlement has become a societal problem that bleeds into fandom. Everyone wants things bigger, better, faster. Capitalism really did a number on humanity.

Anyway, that's just my take on things. I've been here a long time, and just because I don't always point things out or say anything as of late doesn't mean I don't still notice it. I've just gotten jaded I think. It is what it is, so I stay in my corner with my friends and just have as good of a time as we can. 🤷♀️

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last year, after Disney had the temerity to issue a statement opposing one of his prized legislative initiatives, Ron DeSantis punished the company by removing its self-governing status. (DeSantis justified the maneuver as a removal of unjustified privileges, but he had not previously opposed Disney’s status and made little attempt to disguise its nakedly retaliatory nature).

On Monday, he took matters much further. DeSantis appointed a board to oversee Disney. The Central Florida Tourism Oversight District is stacked with DeSantis cronies, including Bridget Ziegler, a proponent of his education policies; Ron Peri, who heads the Christian ministry the Gathering USA; and Michael Sasso, president of the Federalist Society’s Orlando chapter.

While the board handles infrastructure and maintenance, DeSantis boasted that it could use its leverage to force Disney to stop “trying to inject woke ideology” on children.

“When you lose your way, you’ve got to have people that are going to tell you the truth,” DeSantis proclaimed. “So we hope they can get back on. But I think all of these board members very much would like to see the type of entertainment that all families can appreciate.”

It is worth pausing a moment to grasp the full breadth of what is going on here. First, DeSantis established the principle that he can and will use the power of the state to punish private firms that exercise their First Amendment right to criticize his positions. Now he is promising to continue exerting state power to pressure the firm to produce content that comports with his own ideological agenda.

Whether he is successful remains to be seen. But a few things ought to be clear. First, DeSantis’s treatment of Disney is not a one-off but a centerpiece of his legacy in Florida. He has repeatedly invoked the episode in his speeches, and his allies have held it up as evidence of his strength and dominance. The Murdoch media empire, which is functionally an arm of the DeSantis campaign, highlighted the Disney conquest in a New York Post front page and a Fox & Friends segment and DeSantis touted his move in a Wall Street Journal op-ed.

Second, DeSantis’s authoritarian methods have met with vanishingly little resistance within his party. The only detectable Republican pushback has come from New Hampshire Governor Chris Sununu, who warned, “Look, Ron’s a very good Governor. But I’m just trying to remind folks what we are at our core. And if we’re trying to beat the Democrats at being big-government authoritarians, remember what’s going to happen. Eventually, they’ll have power … and then they’ll start penalizing conservative businesses and conservative nonprofits and conservative ideas.” (Of course, this warning holds only if Republicans believe they will have to relinquish power. If DeSantis can truly follow the example of Viktor Orbán, losing power becomes only a theoretical risk.)

And third, DeSantis has been very explicit about his belief that he sees his methods in Florida as a blueprint for a national agenda. So there is every reason to believe that, if elected president, DeSantis would use government power to force both public and private institutions to toe his line. Speaking out against him, or even producing content he disapproves of, would become a financially risky proposition.

Part of what makes DeSantis so dangerous is that Donald Trump created a very defined idea of authoritarianism in the minds of his critics. His refusal to accept the 2020 presidential-election results was indeed a dangerous attack on democratic legitimacy — but this especially notorious episode has overshadowed his other efforts to abuse state power. Trump wielded federal regulations to punish the owners of the Washington Post and CNN for coverage he disapproved of and used diplomatic leverage to extort Ukraine into smearing his political rival. Republicans either supported or ignored these abuses of power.

To whatever extent they have principled objections to authoritarianism, those objections are limited almost entirely to fomenting a violent mob to overturn an election. And while inciting an insurrection is extremely dangerous, it hardly exhausts the scope of illiberal tools available to a sufficiently ruthless executive.

Damon Linker recently criticized liberals for unfairly calling DeSantis as bad as Trump. Linker’s prediction that a second Trump administration would be more dangerous than a first DeSantis administration might be correct. But it’s hard for me to understand how he can state this so confidently when he acknowledges DeSantis’s illiberal intentions and lack of democratic scruples. Comparing the relative evils of two authoritarian-minded leaders seems to be mainly an exercise in guesswork.

A year ago, I wrote a long profile of DeSantis, in which his deep-rooted distrust of liberal democracy was a major theme. Last fall, I attended the National Conservatism Conference, where the attendees laid out rather plainly their ambition to turn DeSantis into a model for a ruthless, illiberal party that would use the organs of the state to crush its enemies. Since those pieces appeared, DeSantis’s actions have made me more, not less, concerned.

Whether DeSantis would actually do more damage to American democracy in office than Trump could remains hard to say. Perhaps, perhaps not. But we should recognize that he is not putting himself forward as a critic of Trump’s authoritarianism. He is promising, on the contrary, to exceed it.

#us politics#news#intelligencer#2023#gov. ron desantis#florida#Disney#reedy creek improvement district#Central Florida Tourism Oversight District#Bridget Ziegler#Ron Peri#Gathering USA#Michael Sasso#federalist society#First Amendment#1st amendment#freedom of press#freedom of speech#free speech#gov. Chris Sununu#Damon Linker#authoritarianism#fascism#gop#conservatives#republicans#gop platform#gop policy

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

i guess i never knew better (discussion)

CW: pretty depressing, pls don't read if you dont want to get in a bad mood :[

hi i know i've been dead for about a month but i wanna talk about something; get something off my chest

i wish i could go back and change who i was back in 2020-2022. i just seemed like a total asshole, and all i did was do fearmongering and post about me being depressed 24/7 instead of posting actual talent...not like i ever had talent.

it sucks. what kind of person was i back then? i was straight up unlikable. no one wanted to hang around with me since i was all political and edgy and shit. it was verryyy cringe. i had so much potential yet i wasted it on edgy art and rant/vent posts 24/7. not to mention i was so fucking dramatic, fucking getting all sad and shit all because i said something that no one saw at all. another thing to add: i have a shitty hyperfixation that won't stop. and its with a cartoon character. its been 4 fucking years.

"robo you were just a child" yeah no shit but come on. even 9 year olds would act better than me. i was a troglodyte, trust me. i know i can just move on, but i'm just so fucking guilty of how many people i upset with my posts on ig and twitter back then 3 years ago. im so sorry.

i had so much potential but now i just cant start over anymore since im a terrible reminder of how i used to be when i was all over social media. i barely fucking use it anymore because i learned to shut the fuck up. plus i have to learn it the hard way: my old art was ass.

if you're wondering if i ever got help, yes i am getting help right now and i am recovering. things have been very traumatic this year for me but i can tell you im handling this a lot better than myself from 2022.

cheers

#personal vent#vent post#fml#what do i even do with my life anymore#im just a worthless slob that had nothing to do in my life back then#now i have health issues because i was a fatass sitting behind a keyboard for 3 years#my life sucks

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Role of Memes in Politics

What is a meme? According to Galipeau (2022), a meme is essentially an intertextual mashup of a screenshot, GIF, or image from pop culture, finished with some text. Memes have evolved from being a mainstay of sorts on social platforms such as 4chan to being an essential and necessary component of visual communication in the realm of political debate and conflict in the past few years (Mortensen & Neumayer 2021). If you ask me, memes can be seen as the sambal to the nasi lemak that is politics; they give it a certain flavour and add some spice to it. However, this raises the question: do memes — as popular as they are in politics, Malaysian or not — help people to have a better grasp on their local political scene?

The way I see it, memes are able to achieve this due to certain attributes that they possess. For one, memes are widely available and simple to post on social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter/X, and Instagram, which makes them a powerful tool for capturing the attention of a wider audience, in particular the younger generation. The results of a study by Mihailidis (2020) indicate that the participants of said study (mainly comprised of young people) were all familiar with memes and frequently used them in their online communication. Some memes also have the potential and ability to simplify complicated political topics so that a wider range of individuals can understand and relate to them. This aligns with how more and more research suggest that memes can have an influence on political communication at local and national levels (Mihailidis 2020), which goes to show just how influential memes can be in regards to politics.

instagram

Besides that, memes provide an avenue of sorts for people to exercise free speech. Mortensen & Neumayer (2021) suggest that it is important to consider memes as a continuation of political humour such as comics and/or cartoons, which are commonly rife with satire, comedy, and parody. Bulatovic (2019) reiterates this by pointing out that politics has always been filled with humour and satire, but ever since the Internet's inception, everyone has had the opportunity to express their opinions in a comedic and sarcastic manner, one way or another. What differentiates memes from the previous forms of political humour is that they are more remixable in terms of their context and substance, and are produced by anonymous groups of media users as a component of participatory digital culture (Mortensen & Neumayer 2021). In a hilarious and memorable fashion, they can draw attention to political oddities, contradictions, and hypocrisy. Through this, memes can serve to check on political authority and allow people to express their displeasure with the political system or particular politicians and political parties (Bulatovic 2019).

In addition, politics can occasionally benefit from the strategic usage of memes. Memes can function as effective rhetorical tools in political disputes, in which political authority and hierarchy are either affirmed, contested, or challenged, as stated by Mortensen & Neumayer (2021). Through widespread replication, memes have been turned into a potent weapon for waging political conflict with adversaries in a “memetic warfare” of sorts (Bulatovic 2019). Similarly, a study by Galipeau (2022) demonstrates that memes can have an impact on a key factor that voters use to make their decisions during a political campaign. This can result in memes being created and distributed by politicians and political parties in an effort to sway public opinion, discredit their rivals, or reinforce their own message in an effort to win over public support.

instagram

Now, with all that’s been said, does it make memes a worthwhile tool in understanding politics, even in a Malaysian context? Sure, they have the ability to make politics more relatable to the masses, but to a certain extent. In my opinion, it takes a more comprehensive approach to properly comprehend politics as a whole. Memes may be a helpful and entertaining method to engage in political discussion, but they should be viewed as a tool for deconstructing, criticising, or mocking politics, rather than as a complete source of political knowledge and information. As stated by Edwards (2021), there is every reason to expect that memes will continue to influence political debates and communities in the near future, as they have evolved into constitutive sources of political speech, for better or worse.

instagram

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Movies I watched and books I read this Week #127 (Year 3/Week 33):

The Fury of a Patient Man, a tense Spanish thriller about a man who waits 8 years to take revenge on the killers of his fiancé.

🍿

2 tender Japanese dramas by female director Naomi Kawase plus another by Yasujirō Ozu:

🍿 Tokyo Twilight, my 6th Ozu drama. A story about an older, single father, two grown up sisters, a mother who left and then came back, an unplanned pregnancy and a death of a daughter. Tragic, subtle and patient family soap opera, his last film that was beautifully shot in black and white.

🍿 I used to enjoy eating Dorayaki, the cookie-snack made of two small bean-filled pancakes, which we often bought at ‘Ranch 99’ stores. Kawase’s Sweet bean is a slow, emotional food porn story, about a solitary owner of such a small Dorayaki store. He hires a 76-year-old woman with a recipe for a better red bean filling, as well as a dark personal secret. Gentle and poetic.

🍿 I was curious about her earlier (1992) art film Embracing because of (personal) reasons. It’s a cinema-verite exploration of her own search for her father, who had left her and family when she was a small girl. Meditative poem about abandonment, loss and identity.

🍿

Eveready Harton in Buried Treasure is the first-ever hard-core, triple-X pornographic cartoon from 1928. It was made clandestinely by certain unknown illustrators from three studios, Disney, Max Fleischer and the Mutt and Jeff studio. It's as explicit as you can get, and involves masturbation, intercourse, bestiality, anal penetration, dildos, ejaculation, and so much more. It was made for a private stag party at the studio, and obviously was never exhibited publicly. Available in full on Wikipedia, and highly recommended. (Photo Above).

🍿

2 directed by Pixar’s Peter Sohn:

🍿 Partly Cloudy, his earlier short about a stork that is delegated to delivering the “less desirable” babies, these of porcupines, and crocodiles and electric fish. Really, Storks?…

🍿 The disappointing new computer-animated Elemental was the first Pixar product I couldn’t finish. A shallow 100% Disneyfied world building that started at a Disney cruise, and moved into a mythical Disneyland, without a heart or a soul. 1/10.

🍿

Because I'm a political masochist, I watched the 4-hour 2020 documentary The Reagans. I always held that this despicable puppet-master, was the most destructive modern American president, even more than Nixon. A good looking elitist, affable reactionary, a nicely-smelling, racist piece of shit, who changed America for the worst, and laid the foundations for all the horrors that were later Donild Trump. As Higgins told Condor: "You poor dumb son of a bitch. You've done more damage than you know."

I have to stop watching movies about monsters.

🍿

Paco León Spanish sex comedy 'Kiki, Love to love' that I saw last week, was kinky, delightful and original. So I was surprised to read that it was a remake of an Australian film. However, The little death had no juice at all, it was forced, prurient, unfunny and worst of all - unsexy. 2/10.

🍿

On the flight from Denmark to Israel I read the “erotic” thriller Skinny Dip. I used to like Carl Hiaasen years ago, but this story of a wife who survives being thrown from the deck of cruise ship, was mediocre pulp. The worst part was the Hebrew translation, which made it unreadable. 1/10.

🍿

(My complete movie list is here)

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ayo Rhemia!! I haven’t seen you around a lot, but there’s a big topic I’ve been wanting to ask but haven’t because I thought it was a weird topic to ask about, so just ignore it if it is. Or discord pm about it instead lol

I haven’t read much of team player, but I’ve been interested in the ask blog. What I’m curious about is how you’ve incorporated the themes of politics into the characters and how you’ve gotten the research as a young writer (that sounds… intense… but this is just for my own practise and fun basically.)

I ended up accidentally creating a set of ocs where I realised young adult modern politics is basically the main theme, and seeing in ur work it seems really interesting. But I don’t know much about politics other at all (than seeing tumblr posts, which is uh-not a really credible source of information), and it’s pretty scary to begin research :’)

So I thought I’d ask how you did it! If this is all too much, I’d just be curious how you came up with the idea of team players.

hihi!!! cant say that i've done much deep research SPECIFICALLY for teamplayer (other than re-checking details about luis and lily and their culture cause i dont wanna get it wrong, i keep it in mind whenever i write them) because i'm just naturally a very political person, and the way that the teamplayer characters themselves are built from experience. none of them are intended to be political mouthpieces for me! all of them are hugely on the left but they have varying inner-community opinions, and they're all very... teenaged.

a lot of the experiences of the characters are just mirrors of what i've picked up from being in both the online LGBT community and the one i knew in middle and highschool. it's a bit of a comedic parody of the whole twitter environment in 2020-2021, though the year isn't all that specific!! one of these bitches dsmp fans though lets be honest

i'm sure a lot of the topics i talk about will shift as i grow myself, and as the characters grow, but as they are right now, these are mostly 14-15 year olds only dealing with the effects of large-scale problems like climate change, lgbtphobia and poverty, and they generally respond like 14-15 year olds in those issues. they're not old enough to dig their claws in deep to the root of the problem, but they've got shit to say about it, especially because it directly hurts them. and they'll occasionally argue about it! cora and fate's cartoon argument was very funny (especially because i agree with neither of them)

fate is the biggest projection of me in terms of political opinions, but he's also the projection of the political opinions i had when i was 14, which were naive and well meaning but ultimately harmful and ignorant. i've always been deeply political, and i've just stumbled into my way into a story that tackles a LOT of topics about lgbtphobia.

also i would recommend checking out the comic if you haven't!!! im not super proud of chapter one and will probably redraw it someday but chapter 2 has been very silly so far

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

so my good friend @valkylander just replied to my post about BJ Horseman about Moral Orel and now i’m thinking about Moral Orel bc like

i feel like Moral Orel was genuinely a cartoon ahead of its time completely fucked by the network, and i think to myself- how would it have fared if it aired now, as a netflix or hulu show? with the writers having freedom to fully explore what htey wanted?

and one hand, i feel like Moral Orel could’ve thrived in that kind of environment, at least BEFORE Netflix started going down the shitter and cancelled every show that didnt’ make exactly ten billion dollars

but on the other hand- it was like, unique for its time, you know? as this show, this really dark adult comedy cartoon that made actual statements related to Evangelical extremism and purity politics in the United States to make a critique on American religious society and broken, abusive families using religion to hide and justify why they’re so broken and able to put on a happy smile in front of others when everyone, including the children, are drowning in those families. it was a unique dark show at the time, that you didn’t expect fucking Cartoon Network (even on its after dark program) would show, and it’s easy to think “well, maybe if it had been on netflix...?”

but on the other hand, isn’t that determent to it too? you know, Bojack Horseman started airing in 2014. and it set a new standard for this kind of western animation. the adult comedy cartoon that also makes statements about society and genuinely deep, and dark plots. America still hasn’t really accepted the idea of animated shows having profound morals and impact- it’s a newer concept that mostly accepted by younger audiences. and Bojack Horseman has helped push this idea. but for better or worse- this exact genre, the “adult comedy cartoon that’s also serious” had to compete with BJH as a result.

and it makes me wonder- would Moral Orel have actually been a success today? i mean, that’s not to say it wouldn’t be popular and have a devoted fanbase- but would it have had the same impact it had back then? or would it have been doomed to the discourse of- “well yes, it’s good, so let’s compare it to Bojack Horseman-”

and Bojack Horseman is easily one of my favorite western animations ever, i’m not saying this to disparage it. and it helped pave the war for this “new” genre of cartoon that’s still growing in popularity. but it really does make me wonder- even if Moral Orel had been saved, if it was a show being released in lets say 2020 compared to the early 2000s. would it have been a truly unique show that stood out on its own as something truly ahead of its time?

or just a memorable adult cartoon, that in turn is always compared to and pitted against Bojack Horseman in this context of discussing story and animation?

16 notes

·

View notes