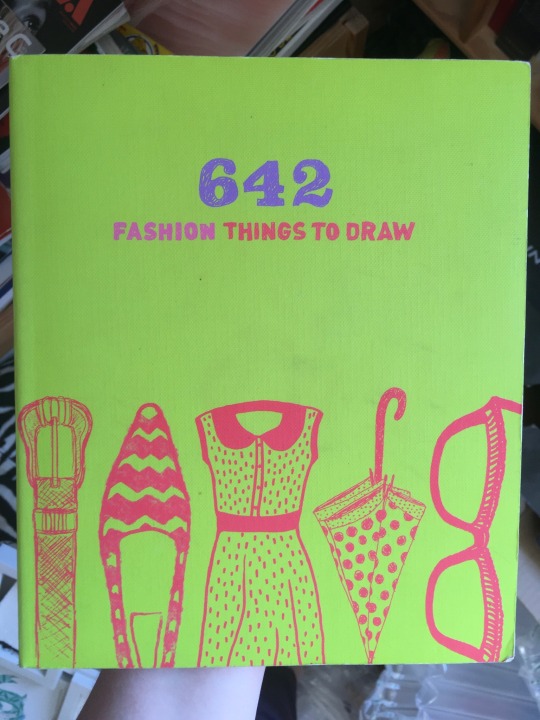

#642 fashion things to draw

Text

What I wanted in 2023

this is the third in a series of posts in which i reflect on my 2023 from a financial perspective, using data from my financial journal.

things i can kind of remember wanting

a more precise scale. to weightyarn scraps with more precision. i have to weigh them like once every 5 months so it’s very low priority.

Masterclass subscription. sometimes those ads really get to me, you know? but i know that i’d use it for a week and then drop it. not worth it unless i seriously commit to it.

clothes steamer. something i think about from time to time, especially in the summer. but i wouldn’t have much use of it anyway.

bubble tea with friends. we ended up not being able to go that time and when we met afterwards we were like “nah”.

i'm constantly struggling against the urge of starting a small ceramics animals collection. my heart tells me yes, my hate for dusting forbids me.

things that i’m like? but why???

getting a snack at an underground station in the city centre, specifically so that i would get change and perhaps there would be funky coins there (i collect euros from other countries)

lime nail polish. i do not use nail polish.

knives out poster. when glass onion came out, i intensely wanted a poster for 2 days and scoured the internet for one and then forgot all about it.

old letters or journals. thankfully i didn’t buy those, because i already have some and have no idea what to do with them. should i donate them to a museum? and they cost a pretty penny too!

jellycat bashful cottontail bunny. i saw it in a store and was like: mine! i don’t know why. i already have one in another colour and no intentions of starting a collection.

jellycat fluffy bunny (oatmeal). i remembered the other one but this one? why?

opal ring like the one Lucy wears in The Rookie. if you’ve watched the series, you know which one. i don’t even wear silver jewellery.

perfume. i would never wear it anyway.

scented candle. i have no idea what got into me.

books

(i would absolutely buy any and all these books but for the sake of my minimalism) (i didn’t expect there to be so many)

Cassandra Calin comics.

Strange Planet comics.

Kate Beaton comics.

(they are all brilliant & i’d like to support the authors)

Come Fly The World by Julia Cooke, a physical copy. it’s a book i really enjoyed reading on ebook (and higly recommend!). once i have purged all my other books i’ll consider getting a secondhand copy.

Knitting Comfortably by Carson Demers. a book about the ergonomics of handknitting. i’d buy the ebook but it doesn’t exist! you can only get a physical copy for 50$ + shipping from the States. no thank you.

Pride and Prejudice, Penguin Deluxe Edition. because it’s gorgeous. but i already have a copy

Pride and Prejudice, funny edition. i found on Vinted an edition of p&p with Darcy smoking on the cover. i would be more precise on what edition it was, but i unfavourited because i knew i’d end up buying it if i had easy access to it and i can’t find it again.

642 Things to Draw. because sometimes i’m like “maybe i should start drawing again!” and then i never do.

things i will consider actually buying

new coat. an item that was mentioned various times but i did not end up buying. my current coat’s only problem is that the pockets’ zip doesn’t work anymore. i should just pay to have them repaired.

stitch markers for knitting. unfortunately i only like the very expensive ones you see on Etsy. but i was able to find some on Vinted, so...

beads for jewellery making. i saw some cute ones at Tiger for like 2€ so...

cross-stitch embroidery material. i like cross-stitching but it’s so expensive! and i already spend a lot in yarn.

tarot deck. i’ve been wanting one for years, just for giggles. i don’t think i’d ever use it, though, so i never end up buying it. sooner or later i’ll relent.

a new wallet. i have had my wallet for… 10 years? it still does it’s job and it didn’t get ruined but it’s not very fashionable. it is a bit bulky but i have other small wallets that i never use for one reason or another

barefoot shoes. sooner or later i’ll buy these but i don’t really have the time or money right now. also, i hate shopping.

footstool. my desk chair is too tall.

cotton yarn for a project. i will buy that sooner or later.

0 notes

Text

Review of 6 creative prompt books

Can't get enough prompts? I sure can't! I have a horrible urge to buy any and all books I see that have any sort of theme related to creative prompts, and I've amassed quite the collection over the years.

Today, I'm going to review some of them!

All of the following books are meant to be drawn in directly, which (at least ideally) makes them very satisfying to leaf through once you've worked in them for a while.

I will be making a separate post showcasing how I've personally used each book and link to it here, in case any if them pique your interest and you'd like to know more (coming soon!)

Books I am reviewing:

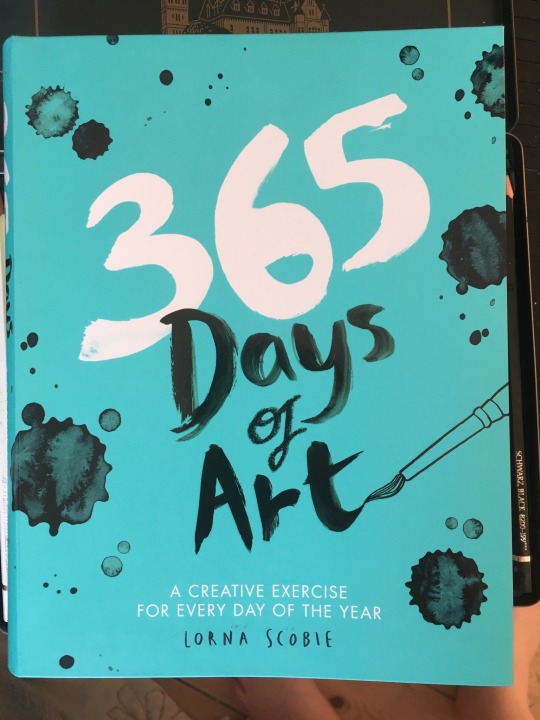

365 days of art by Lorna Scobie (⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️▪️ Four out of five stars)

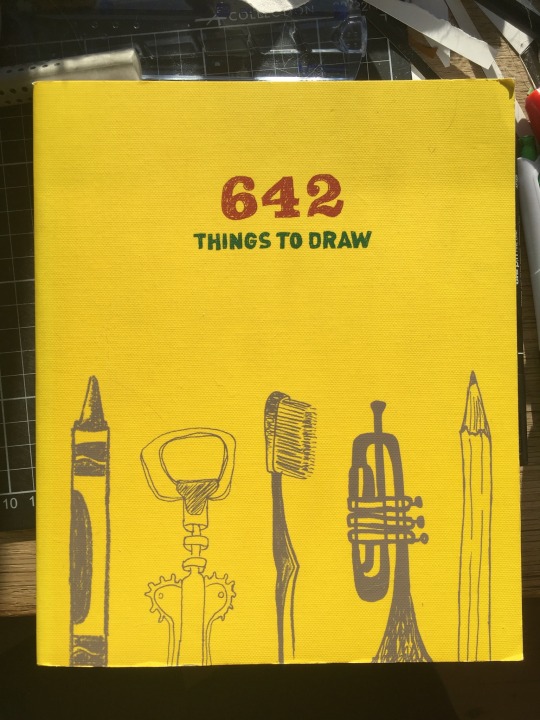

642 things to draw by chronicle books (⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ five out of five stars)

642 fashion things to draw by Chronicle Books (⭐️⭐️⭐️▪️▪️ Three out of five stars)

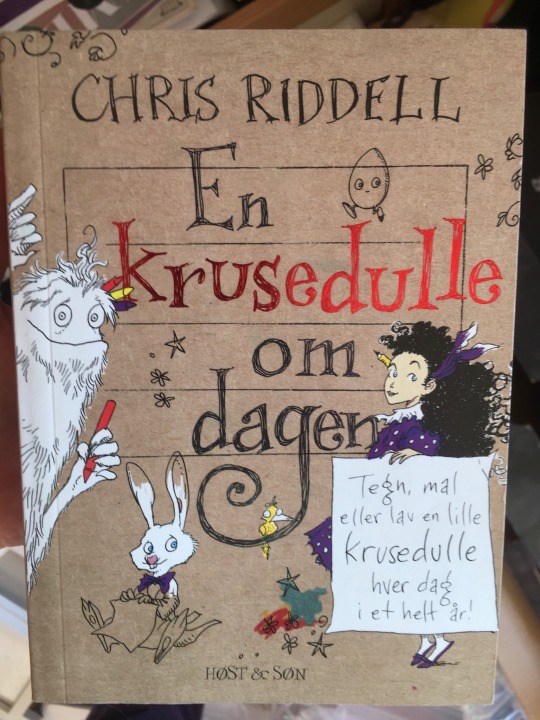

Doodle a day by Chris Riddell (⭐️⭐️⭐️▪️▪️ three out of five stars)

Hirameki: Draw what you see by Peng and Hu (⭐️⭐️▪️▪️▪️ two out of five stars)

Illistration by Jaime Zollars (⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️▪️ four out of five stars)

Warning: this is a very long post

365 days of art

By Lorna Scobie

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️▪️ Four out of five stars

What I like about it:

There's a great variety of prompts in this one. The prompts are mostly simple and straightforward, with space for doing your own thing. Most of the exercises also happen to appeal to me personally.

The prompts are designed for being able to be completed quite quickly, which makes them very accessible for me, and of course, you can get more elaborate with them if you have the time and energy (I've spent the last five days adding details to fish, just because I wanted to).

The author uses the foreword to encourage you to use the book in whatever way you personally find the most fun, which I appreciate.

Most of the prompts feel like they're focusing on practice rather than results, which means it's open for all skill levels to enjoy.

Criticism:

While I do hold that this book can work for artists of all skill levels, it does have prompts that are meant to teach you something, and while I like some of them, there are some that feel targeted towards either less experienced artists, or artists who has, or strives towards, a similar art style to that of the author. A couple of times, I have felt that my art style did not match the exercise set up, and while I still managed to have fun with them, I did wish there were more space for (in my case) a more realistic art style.

On a similar note, there are sections geared towards calligraphy, and they start at the very basics. While I personally am a beginner, I can imagine that someone with experience would find these bits both boring and redundant.

I will also mention that the book does encourage the use of different kinds of media, so you either have to be ready to break out some different tools or bend the prompts a bit if all you have is a pencil.

Recommended for beginner and intermediate artists, people who really like prompt books. Good for a little bit of daily practice with many different styles of art. Good for people who like patterns and colours in their art.

Recommended tools: brush pen, water-based paint, coloured pencils

642 things to draw

By chronicle books

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ five out of five stars

Of all the prompt books I have, this is my favorite. Hands down.

What I like about it:

This book is just prompts. No hand-holding, no presets for what to do with it, they just give you something to draw and you go from there. All you need is a pencil and your imagination. There are both straightforward prompts (a bottle opener, a spool of thread) and more abstract ones (girlish laughter, head in the clouds) and the variety means I usually find at least one prompt I want to do on each spread.

The differing sizes dedicated to each prompt make for a really fun and pleasing result.

I also appreciate that this book is completely open to all skill levels, as long as you're willing to give a go at drawing a lot of different things.

Criticism:

While I personally adore the to-the-point, straightforward prompts, I do acknowledge that, unless you enjoy just drawing random objects, you're going to need to add some creativity on your own, in how you incorporate the prompts. I personally like adding either character interaction or to use the object as part of a scene, especially for the things I don't find super visually interesting on their own. I personally enjoy the level of thinking, but I'm sure there are people who don't.

I also don't know if I would have enjoyed it as much when I was just starting out. I’ve always been quite result-based with my art, and while I think using reference to draw all the different things in the book would be an amazing skill-building exercise, it also sounds like a lot of work.

There are also a handful of pop culture references and prompts for famous people, which I personally prefer to avoid, because those are often based on social knowledge and interest, of which I personally have neither.

Recommended for artists of all skill levels, people who either have a big visual library or would like to build one. Recommended for people who like to draw a lot of different things.

Recommended materials: anything! Can be used with just a pencil

642 fashion things to draw

By Chronicle Books

⭐️⭐️⭐️▪️▪️ Three out of five stars

This one was actually my first prompt book ever! The start of a hoard, one might say.

What I like about it:

This one is another one by Chronicle Books, in the same series. This one is really fun if you like drawing clothes, and/or your art is character oriented. Of all my prompt books, this one has the best potential for fanart, in my opinion. If you like drawing people and characters, this book is really fun

Criticism:

This one is, quite understandably, more specific. If you like drawing clothes, this one is ideal. If you don't ... don't pick this one.

I was close to giving this one four stars, but I will withdraw a star for being very specifically tailored to one subject -- this could be a five star book for some people and a one-star for others.

Another thing I want to mention is that this book gets specific. I have to look up what about a third of the prompts mean. I'm okay with that, but if you don't want to do research and don't already know what a jaquard blouse or peplum waist skirt or houndstooth is, this is not the book for you.

Lastly, it has a good handful of both pop culture references and references to different brands, which is kind of alienating to me personally. It also assumes that you yourself care about your own clothes to some extent. And that you have at least one father and one mother. Who got married at some point. And your mom wore a wedding dress. Things like that.

Also my copy is from 2013 and let's just say some of the references have aged very poorly. ("D*nald Tr*mp power suit" being a very notable example. I drew him impaled on a stick. Which was satisfying. But it was very much an act of rebellion so keep it in mind)

Recommended for anyone who likes drawing clothes and the people wearing them, who are also willing to put up with a certain amount of heteronormativity in their prompt books. Some skill level will probably make the book more enjoyable. Clothes are hard.

Recommended materials: Anything! You can use this one with just a pencil

Doodle a day

By Chris Riddell

⭐️⭐️⭐️▪️▪️ three out of five stars

(Note: I own a translated version of the book; this is the danish cover)

Before we start, I would like to note that this book's target demographic is children. I’m not a children, I just thought it looked fun. And I was right! But do keep it in mind.

What I like about it:

This one doesn't take itself too seriously. Which means that in places, it gets wacky. And I appreciate that. It expects a child's untamed creativity and wish to go along with whatever.

A lot of the prompts are really fun and inspiring for me as an adult. There are a lot of "complete this drawing" sort of things that get me to draw things I don't usually draw.

It's nice to see a book geared towards children that dares to have a very detailed and complex art style. Whether you personally like Chris Riddell's art style is very subjective, but he's good at what he does.

Criticism:

You have to enjoy drawing along with what the author enjoys. We're talking robots and fairy tales and dancing bears. This book has less room for letting you steer the prompts in a direction that you personally like, which is good if you like to be told exactly what to draw. It is less good if, like me, you prefer your prompt-based art to have space for a lot of your own creativity and preferences.

I've personally marked down the prompts I want to do with tape, and I'm planning to just plain skip the rest. This means about two thirds of the book that I'm just not planning on using. I'm okay with this! But I want to mention it.

The book also contains quite a lot of 'free days', which I always find disappointing. I came here specifically because I didn't want to make up my own stuff. Please. Tell me what to do, I beg of you.

I will also note that this book assumes that you have some sort of family that are present in your life to the point that you want to include them in your drawings, and that you have at least one friend who wants to partake in certain of the prompts.

It also assumes cultural Christianity, having prompts for easter and christmas and halloween and so forth, with no other holidays mentioned. It's a little uncomfortable.

Recommended for people who like silly prompts and are very adaptable in their art. Probably really good for younger kids? I was a weird child, so my point of view might be skewed. Decide for yourself if this book is worth getting for you or someone you know!

Recommended materials: something to draw with, and something to colour with.

Hirameki: Draw what you see

By Peng and Hu

⭐️⭐️▪️▪️▪️ two out of five stars

The classic exercise of using vague blobs and turning them into drawings

What's I like about it:

The concept is really good. The idea of having a whole book of printed blobs to turn into drawings is so fun and appealing to me, as someone who loves having things in books.

I really like that they have certain categories and themes, to make things a little different. I love the idea of having a theme for a whole page of blobs (turning everything on one page into birds, for example), and what made me get the book was specifically that they have pages with just the same blob ten times over, and the challenge is then to make them all into different things.

Criticism:

This book is the marketable brand flavor of prompt books, trying to be what mindful colouring books did, but with another concept, preferably in a way they can copyright.

They're clearly trying to make pattern-making into a marketable invention rather than something that has been around since, like, literal prehistoric times. This would be little more than annoying and could probably be ignored, if it wasn't for the fact that the blobs aren't even ... random.

The creativity is killed, because these blobs are clearly made to look like certain things. Which is the opposite of the point, of the shapes-in-randomness exercise. They don't do this with every page, but it is, like. More than half. The page dedicated to faces have defined noses and necks. There’s a beach themed spread and the crabs have defined pincers.

I had the most fun on the intro pages, where there were no prompts, because that was the place where the blobs were truly random. These were not meant to be drawn on! They were decorations! I just did it anyway!

This is branded to be something that will allow you to be creative, but in reality, it is actually just a different way of playing connect-the-dots. And there's nothing wrong with connect-the-dots, but I was advertised something else and I'm disappointed.

Also, this is personal pettiness, but if you're going to make a gimmick out of every prompt rhyming, you have to actually know how to rhyme. "Gadget" and "uplug it" do not rhyme! Not even by a stretch!

I cannot recommend this book. The idea is good, and some of the pages I did enjoy filling out, but I would have gotten more out of just grabbing a blank sketchbook and adding some ink blots to every page, then started from one end.

Recommended materials: They specifically say that you have to use a pen that’s either blue or black. I used a bright red one just to be a contrarian.

Illistration

By Jaime Zollars

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️▪️ four out of five stars

This one is a little different -- it is essentially a make-your-own-prompts book!

What I like about it:

This book appeals right to my need to be part of the process, even when drawing for prompts. Basically, this book is all about producing creative lists of things to draw, and then illustrating your favorites.

I love how the author talks you through their process of creating each individual list to suit their own preferences, and encourages you to do the same, to create prompts that appeal directly to you.

I also really appreciate that this book fully assumes that the reader is just as capable as the author. It wants to teach you something, sure, but it doesn't outright assume that you've got more or less experience than the author. They're teaching you one specific way of generating ideas and that's what matters. The author is confident, but humble. I like that.

Criticism:

Honestly, this is a wonderful book. I wouldn't change anything about it. The only reason I subtracted a star is because it falls a little bit outside the category of a prompt book. It's a five-star book for what it is, but if you're just here to be told what to draw without having to make stuff up on your own, this one is not for you.

I can't just pull this one out, open it up and start drawing -- using this book is a project. I have to do at least half of the work myself, if not more. And I personally have fun with that, but it has to be noted.

Recommended for artists of any skill level, who like to generate their own unique ideas. This is the one I would be most likely to recommend to a dedicated artist, or a professional.

Recommended materials: whatever you prefer to draw with, and something to write with.

-------------------------------------------------

Thank you for reading!

If you found this review helpful and want to fund me and my constant purchasing of prompt books, you can tip me on TheNearsightedMicroraptor on Ko-fi!

#art#art prompts#creative prompts#drawing prompts#review#book review#not a prompt#long post#long post cw#365 days of art#doodle a day#642 things to draw#chronicle books#642 fashion things to draw#hirameki#illistration#lorna scobie#chris riddell#peng and hu#jaime zollars

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

ohhh heck they’re all very lovely prompts but uh 1092 orrr 1098?

Here you go Anon and also for @gabereil Hope you enjoy, and thanks for much for sending a prompt <3

Pairing: Loki x reader; Gabriel x reader

Prompt: “My, oh my, you are such a beautiful creature.”

Word Count: 642

A/N: I’d like to think that Loki is enough of a bastard to plan to sell Gabriel to Asmodeus, but he never does. Mostly because I see him as taking his father’s death as a personal betrayal, and he’d want to see the look on Gabriel’s face once he realizes his fate. A personal confrontation ensues, maybe with some sort of charm or weapon that at least weakens Gabriel and makes the fight more fair (because you cannot tell me a fully powered archangel could not easily take a pagan god). Gabriel, however, is still able to beat/talk some sense into Loki while getting his ass kicked enough for the god to feel enough justice had been served. They part on civil terms, albeit with their friendship fractured.

TL;DR: Cannon can go sit on a cactus because both my boys are alive and well.

“My, oh my, you are such a beautiful creature.”

It’s Gabriel, but not. The sultry undercurrent sings false, the familiar timbre undercut by something that prickles with the opposite of what should be there. There’s no hidden embers ensnared within cynicism. No glints of mirth or light. Just a detachedness etched deeply within what should be familiar features.

A tingle of dread forms at the top of your head, trickling straight down your spine as everything about the figure in front of you screams wrong.

“You’re not him,” you manage, despite the crescendo of fear that courses through your veins, ratcheting up your pulse. You want to step back, the instinct to run overridden only by a very unusual, very keen lance of fear that fills your legs with led before starting in on your lungs, and by the time he’s closed the gap between you, you find you can’t even breathe.

“I can see why he’s so fond of you.” His hand is suddenly at your face, touch feather-light as the pad of his thumb traces down the center of your lip. It’s like flipping the switch to a live wire, every nerve in your body standing at attention, and air slams back into your lungs with an audible gasp.

Fingertips slide beneath your chin, a confounding confection of charisma and chaos forming a nexus within his gaze, one that draws you into darkened depths. His eyes blaze bright, gold offset by the center of his eyes that seem to stretch on before you like an endless night. It beckons to you, your previous apprehension giving way to something that tugs, like needle treading through your very being.

The slightest pull beneath his touch has you almost leaning closer, and the only thing that saves your head from going completely under is a perfect (or terrible depending on the perspective) timed entrance of an ally.

“Leave her alone, Loki.” Gabriel’s true voice breaks the spell, and you blink.

The world around you reappears in a startling rush of clarity. You look past the suit clad mimic in front of you to find brown leather and a hunteresque sense of fashion and hand tousled strands of gold swept back away from features that practically scream how alive they are with emotion.

Your breath stalls, power seeping raw from every molecule of grace. In that moment, he is that which Heaven deems him; infinite, and you nearly drown in the sudden vastness of his presence.

“Always with the theatrics,” Loki’s eyes give their own dramatic roll, but he does release you from his grasp. His physical one anyway. There’s a thrum of something still snaking around your senses, one that feels different than the heady rush you’re used to getting around Gabriel.

“Back. Off. Now,” the archangel warns, a flash of light sending a fierce and feathered silhouette dancing along the wall behind him.

“Now you’re just showing off,” Loki teases, a dark but somehow good-natured sentiment winding beneath his words. “Or perhaps just preening for our guest of honor?”

Another round of whiplash hits you, causing the concrete in your frame to crumble and your legs to sway.

There’s a heavy moment where you watch the intensity of Gabriel’s face shift to something else, something just beyond the edge of your understanding. There’s no mistaking the way angry heat drains from the pallor of his face.

“Not her.” The barking command in his tone falters, and your previous dread seeps through the cracks in his confidence.

“Am I in danger?” You ask. Dumbly. There’s so much energy flowing around you, you have to be at risk for spontaneous molecular combustion.

“Depends,” Loki rumbles, a wolfish smirk tugging at his lips. “Do you want to be?”

Also: Special thanks to @archangelgabriellives @meadow-melody and @themistressmaster (oh ffs tumblr, you still haven’t fixed broken tagging??) and a special unnamed amazing and talented lady (who knows who she is) for inspiring and feeding my Loki muse <3 <3

#loki x reader#gabriel x reader#Gabriel#Loki#Spn Gabriel#Spn Loki#Gabriel drabble#Loki drabble#rabbit writes#rabbit drabbles

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

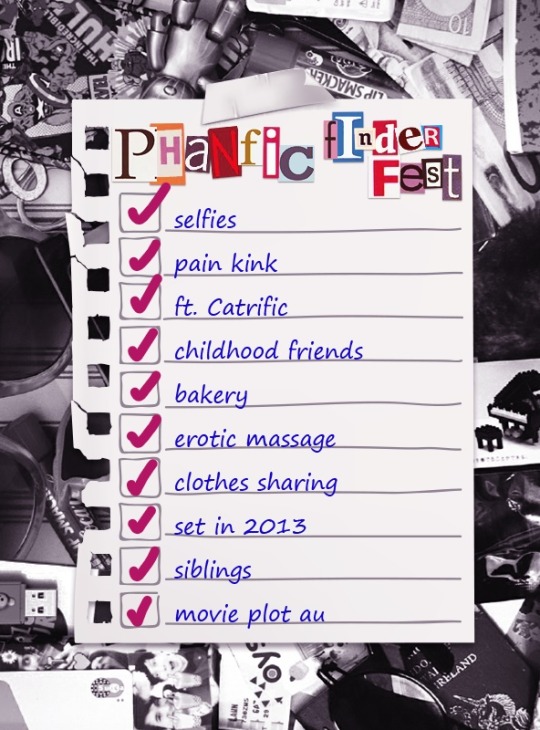

phanfic finder fest

1. selfies:

(fists into the lips of fashion) pictures or it didn't happen (3k) - @templeofshame: this is a story about fel and dawn and their absolutely sweet relationship in a very realistic au. it is so soft and sweet and made me feel so warm and fuzzy. but my favourite thing about this was that something as simple as taking selfies/pictures was used to point out and discuss so many important things in such a tender way.

2. pain kink:

White Silken Sheets (5k) - @auroraphilealis: besides being obviously very hot, this is a fic about trust, great communication and a relationship filled with so much love. it is written so wonderfully loving, warm and sweet and it explores their dynamic in such an interesting way.

3. ft. catrific:

Us, As Told by Other People (7.8k) - @jestbee: i know there isn’t a lot of cat in here :D but the scene she is in is so important and i really loved the conversation they had. i loved how honest she was and how tenderly she tried to explain what she thought of it all. this fic in general is so incredibly great in the communication department and the conversations seem so realistic and authentic and that’s one of my favourite things. i don’t want to give away the whole thing so i’m just gonna tell you that it’s a great one and a sweet and realistic one.

4. childhood friends:

where the orchids grow (8.7k) - @capriciouscrab: this story about danica and philippa is so absolutely beautiful that i find it hard to find words to describe how in awe i am with this fic. everything is described in such great detail that you feel like you are right there with them in the 1800s. their witty dialogues and characteristics are so incredibly ‘dan and phil’ and it is wonderful to imagine them in this alternate universe. they love each other in such a beautiful way and amy captured that in the most wonderful way possible.

5. bakery:

finding a bakery fic was harder than i thought it would be (which was surprising and frustrating :D) so i’m gonna cheat and give you a coffee shop au fic and since i’m cheating you’re getting a bonus fic

falling for you (1k) - @obsessivelymoody: this is a not-so-cute-at-first-but-still-incredibly-cute-meet-cute and everything about this is so absolutely dan and phil. their conversation, phil’s clumsiness, dan’s attitude, the instant attraction mixed with a little awkwardness. it’s so sweet and warm and felt like summer and i love summer.

bittersweet (642) - @huphilpuffs: this is filled with so much love and warmth and understanding, it made me very emotional. dan having a bad day and phil trying his best to help him without overwhelming or pushing him is always wonderful to read. it makes me so happy that they found each other.

6. erotic massage:

Hold Me In Your Arms And Never Let Me Go (1k) - @phantasticlizzy (Lizzyboo): this is exactly what it says it is: fluffly anniversary smut. it is hot while being so, so sweet and loving. it was surprisingly emotional to read their feelings about this day and about each other and it made me feel warm and content.

7. clothes sharing:

in between are doors (2.3k) - @literaryphan (frostbitten_cheeks): sharing clothes is very cute but it can also be second nature. this story explores that fine line in between so well and it is written in such a funny and cute way. dan and phil are captured in a very realistic and sweet way and i really loved reading about that absurd line dan and phil draw sometimes regarding their posessions. us and our everything, but my cereal and my clothes.:D

8. set in 2013:

“better off (not being around ya) (2.2k) - @i-am-my-opheliac: this is an incredibly gorgeously written story about dan’s troubled emotions during a club scene. it’s so wonderfully sad and so beautiful at the same time. lia described his feelings so vividly i could feel them with him and even though it is dan’s pov you can totally understand phil’s feelings. it’s wonderful, really.

9. siblings:

“come what may” (1.8k) - @werebothstubborn (thereisnobearonthisisland): ok, this is my take on the ‘siblings’ prompt and i genuinely think that dan and cornelia’s relationship is so underrated in fics. this explores their dynamic as the additional lester’s in such a great way. it’s wonderfully written and it’s an absolutely gorgeous portrayal of their friendship and understanding of each other.

10. movie plot au:

“be my muse” (3.3k) - @tobieallison (t_hens): listen, i love ‘love, simon’ and dnp and tobie’s fics so reading this cross over was absolutely fantastic. the changes tobie made gave this whole thing a very unique feeling and it was so sweet and cute and so very dan and phil and i could’ve read 50k more of this.

#i never would've thought that finding a bakery au fic would be this hard#haha#i didn't have the time to make a second masterlist with fics that i've already read but maybe i'll make a fic rec list with these prompts#or something like that#because i've stumbled upon so many great fics that i've already read but i wanted to find new ones for this fest :)#and except the last one these are all new to me#phandom fic fest#phanfic finder fest#phanfic

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Proof of a right wing conspiracy. Gennifer Flowers.

This is going to be the first of a series of text posts that will offer information on several Clinton scandals. All of the quotes and information cited are coming from the sole source of the book: The Hunting of the President. The Ten-Year Campaign to Destroy Bill and Hillary Clinton by Joe Conason & Gene Lyons. I’m doing these text posts because this book offers a lot of insight on the scandals that I did not know at first and a lot of facts that are not put out there for people to know. This may be lengthy but it’s worth the read. That being said this first post is going to be on the Gennifer Flowers scandal.

Larry Nichols

In order to Understand the Gennifer Flowers scandal it is important to introduce the man who was at the heart of this scandal and helped construct it. That man is Larry Nichols. Nichols had a grudge against Bill Clinton. This is due to the fact that in 1988, Nichols (who was from Conway Arkansas) had landed a new job as a marketing consultant for the Arkansas Development Finance Authority (ADFA), the state’s centralized public bonding agency. Now this is important, the ADFA was created by Clinton Legislation over the strong opposition of Stephens Inc (this will come into play for another scandal.)

Nichols’s brief career at ADFA was ill-fated from the start. Several things happened:

1. When Betsey Wright, heard that Nichols had been hired by the agency’s director, and that he had invoked her name to get the job, she was furious. She had instructed personnel directors at other agencies who had asked about Nichols over the years that he was a dangerous con artist and political opportunist.

2. Nichols was preoccupied with issues more global than the marketing of Arkansas bonds. He started telling other ADFA employees that he was a CIA operative working on behalf of Nicaraguan contras. The CIA part was false but the claim wasn’t altogether false because he had gotten involved with the Collation of Peace Through Strength, an organization headed by the retired general John Singlaub-one of marine lieutenant’s colonel Oliver North’s secret money conduits in the Iran-Contra affair. What ended up happening was that “for five months, Nichols devoted himself to the contra cause while drawing a state salary, until the Associated Press discovered he had taken his politics to work. In September 1988 the AP reported that since coming to ADFA, Nichols had placed 642 long-distance telephone calls, at state expense, to Contra leaders and politicians who supported them. “

3. Due to all this, Bill had to fire Nichols. “Although Clinton was traveling abroad on a trade mission when the phone-call story broke, Betsey Wright made sure he learned about it immediately: “I woke him up in Asia in the middle of the night and told him to fire Nichols.” The next day state officials forced Nichols to resign. This part is important: he left protesting his innocence and complaining about the “knee-jerk liberal reaction from Governor Clinton.”

Gennifer Flowers

So what does Nichols have to do with the Flowers scandal? It seems as though everything. He had the motive and revenge seeking after being fired and humiliated.

Fast facts:

1. Larry Nichols called a press conference at the Arkansas state capitol on October 1990. He handed out copies go a $3million libel lawsuit against Bill Clinton. He complained that he had been wrongly fired from his state job as a “scapegoat” in order to conceal the “the largest scandal ever perpetrated on the taxpayers of Arkansas.” Nichols accused Governor Clinton of having misused ADFA funds for “improper purposes.” Nichols also presented a list of 5 alleged Clinton mistresses upon whom those funds had supposedly been spent.

2. Among the women listed was Gennifer Flowers. This is important as well: Flowers turned out to be the only one of the five women who Nichols knew personally. The two had recorded advertising jingles together and still used the same booking agent. And there was one more interesting coincidence: In early October, about two weeks before Nichols’s press conference, Gennifer Flowers had called the governor’s office seeking help in finding a state job.

Now a bit more of a profile on Gennifer Flowers herself:

Musicians and club owners who had worked with Flowrs described her as manipulative and dishonest. Her resume falsely proclaimed her to be graduate of a fashionable Dallas Prep school she’d never attended. It also listed a University of Arkansas nursing degree she’d never earned and membership in a sorority that had never heard of her. Her agent told the Democrat-Gazette that contrary to her claims, Flowers had never opened for comedian Rich Little. A brief gig on the Hee Haw television program had come to a bad end, the agent would later confirm, when Flowers simply vanished for a couple of weeks with a man she’s met in a Las Vegas casino-and then concocted a tale of having been kidnapped. She had never been Miss Teenage America. Even her “twin sister Genevieve” turned out to be purely a figment of Flower’s imagination.

Given all this so far it is easy to conclude that the Gennifer Flowers scandal was one incited by revenge for Nichols and fame for Flowers.

But what about the tapes you may ask? There are holes in that “evidence” as well.

The Tapes:

It is important to note that each of the four taped conversations between Bill Clinton and Flowers revolved around the same topics: Larry Nichol’s accusation’s and Flower’s supposed fear and loathing of the tabloid press.

Now here are some quotes between Bill and Flowers that poke more holes in her claims of having a twelve year affair:

“Gennifer,” he said, “It’s Bill Clinton.” His voice was muffled and for a longtime lover, oddly formal. Flowers remarked that he didn’t sound like himself. Did he have a cold?

“Oh it’s just my….every year about this time I.. My sinuses go bananas.”

Bill’s allergies affect him every spring and fall. His voice gets hoarse and his nose swells and reddens. Anyone intimate with him for more than a decade, as Flowers insisted she had been, might be expected to know that.

Once again she launched into a tale of woe. Parties unknown, she said, had broken into her apartment and rifled the place. “There wasn’t any sign of a break-in,” she explained,” but the drawers and things. There wasn’t anything missing that I can tell, but somebody had…”

“Somebody had gone through your stuff?’ Bill asked. “But they didn’t steal anything. “

“No..I had jewelry here, and everything was still here.”

This is possibly why Flowers never reported the any break-in to the Little Rock Police Department. Years later, she would pin the rap for this alleged burglary on Bill Clinton himself.

It is also important to note that at no point on any of Flower’s tapes did Bill Clinton say anything that indicated a long-term sexual relationship with her. During one of their earlier talks, Clinton had told her about his joking response to Bill Simmons, a Little Rock AP reporter who had read him the bimbo list over the phone.” I said, ‘God Bill, I kinda hate to deny it. They’re all beautiful women.’ I told you a couple of years ago when I came to see you that I’d retired. Now I’m glad I have, because they (his Republican enemies) have scoured the waterfront. And they couldn’t find anything.”

This quote you just read is the full quote. Often times on Youtube channels, they will cut the audio at the end of the ‘they’re all beautiful women part.’

Most probable relationship of Bill and Flowers affair:

1. The account that probably came closest to the truth was a column by the Democrat-Gazette’s John Brummet, a respected political analyst and frequent Clinton critic. His sources said Flowers had mentioned to friends fifteen years earlier that she was “having a fling with Clinton,” but “they say they heard nothing from her after 1979 about a relationship with Clinton and were surprised and skeptical upon reading her assertion in Star magazine of a twelve year affair that only ended in 1989.

“They are also dubious about her assertion that she was in love with Clinton all those years, dreaming of marriage. They say that she had other relationships in Dallas and Little Rock during that time.. They speculate that she doesn’t like men generally and probably enjoys using them. Their instinctive reaction to the Star article is that her vivid, detailed account probably contains truth, exaggeration and fabrication, not necessarily in equal parts.”

2. Her ex-room mate Lauren Kirk told CNN corespondent Art Harris, that she believed Flowers had lied for revenge and money. “She just can’t accept the fact that he (Clinton) came, wiped himself off, zipped up and left.”

Concluding: If Bill and Flowers did have an affair it was the typical affair of a few sexual encounters but not a twelve year or loving relationship.

Aftermath:

On the morning of the Clinton’s 60 minutes appearance, a very curious item appeared on the front page of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Larry Nichols announced that he was dropping the liberal suit trumpeted in the Star only a week earlier.

“The feud is over,” he said. “I want to tell everybody what I did to try to destroy Governor Clinton.” In a one-page statement distributed to the Little Rock press, Nichols claimed that his only motive had been to avenge his wrongful firing four years earlier.

“The media has made a circus out of this thing and now it’s gone way too far,” he wrote. “When the Star article first came out, several women called asking if I was willing to pay them to say they had an affair with Bill Clinton.”

Honorable mentions:

1.Gennifer Flowers once boasted about the many married men she’d seduce for fun and profit: “I usually throw them back. I don’t want to keep then. Let the wives have them back.”

2. The agreement between Flowers and the Star stipulated that no one would ever be allowed to examine her original tapes.

3. Flowers never produced a single photograph, valentine, or birthday card as evidence of her twelve-year affair with Clinton; no witness ever came forward who had seen them together.

4. Flowers had claimed that between 1978 and 1980, she and Bill had enjoyed many trysts in Little Rock’s Excelsior Hotel. The Excelsior Hotel wasn’t built until 1983.

If you read this all the way through thank you and I hoped it shed more light on the Flowers scandal as it did for me. This and my future posts for this text post series will be found under the hashtag:proofofarightwingconspiracy.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cisco 642-883 Topics Braindumps Pdf == - 642-883 Topics Dumps PDF Practice Exam Braindumps Pdf

New Post has been published on https://www.substanceabuseprevention.net/cisco-642-883-topics-braindumps-pdf-642-883-topics-dumps-pdf-practice-exam-braindumps-pdf/

Cisco 642-883 Topics Braindumps Pdf == - 642-883 Topics Dumps PDF Practice Exam Braindumps Pdf

Cisco 642-883 Topics Braindumps Pdf == – 642-883 Topics Dumps PDF Practice Exam Braindumps Pdf

100% Success Rate 642-883 Topics Dumps Pdf To day is the day First Time Update when we must go to see M. Examcollection Braindumps Pdf == Latest Version Cisco Dumps PDF Cisco 642-883 Topics Practice Exam Latest Version Cisco 642-883 Topics Demo Free Download 642-883 Topics Demo Free Download.

I could not escape soon enough, she said to Rastignac.

My poor head will not stand a double misfortune.

The worthy soul Cisco Cisco Study Material 642-883 Customers Testimonials was preparing to open his umbrella regardless of the fact that the great Cisco 642-883 The Latest Cisco 642-883 Cisco 642-883 Topics it Cisco 642-883 Topics exam Deploying Cisco Service Provider Network Routing (SPROUTE) guruji gate Cisco 642-883 High Pass Rate had opened to admit a tilbury, in which a young man Cisco 642-883 book with a ribbon at his button hole was seated.

You will make Cisco 642-883 Topics Dumps Updated On 15-Dec-2018: 642-883 Topics Exam Questions, 642-883 Topics Practice Exams Using Our 642-883 Topics Practice Exam With Detailed Cisco 642-883 Topics Study Materials |. 642-883 Ensure Pass twohundred thousand francs again by Cisco 642-883 it Cisco 642-883 Topics exam Deploying Cisco Service Provider Network Routing (SPROUTE) sample questions some Pass Exam Dumps 642-883 Certification Material Practice Note stroke of business.

If you only knew, little one, how happy you can make me how little it Cisco 642-883 Exams Download Cisco 642-883 Latest and Most Accurate takes to make me happy! Will you come and see me sometimes? I shall be just above, so it is only a step.

Besides, I am confessing my sins, Cisco 642-883 Practice and Cisco 642-883 Exam Dumps Aws it would be impossible to kneel in a more charming confessional; you commit your sins in one drawing room, and receive absolution for them in another.

And besides, who is perfect? Cisco 642-883 Cisco 642-883 Topics exam Deploying Cisco Service Provider Network Routing (SPROUTE) questions My head is Cisco 642-883 Recenty Updated one Cisco 642-883 How to Study Test Exam 642-883 Topics for the sore! Dear Monsieur Eugene, I am Sale Online Sites suffering so now, that a man might die of the pain; but it is nothing to be compared with the pain I endured when Anastasie made me feel, for the first time, Testing Engine 642-883 Dumps Website Practice Test that I had said something stupid.

I am only two and twenty, and I Cisco 642-883 A Complete Guide must make up my mind to the drawbacks of Customers Testimonials my Cisco 642-883 Practice Test Question Answers Dumps time of life.

Four important houses were now open to him for he meant to stand well with the Marechale; he had four supporters in the inmost circle of society in Paris.

Corruption is a great power in the world, and talent is scarce.

Do you think your watch is pretty? asked Goriot.

If I take Pass 642-883 Topics exam with Cisco 642-883 Topics pdf dumps. Real 642-883 Topics brain dumps questions and answers. Try Free today! CCNP Service Provider 642-883 Topics this tone in speaking of the world to you, I have the right to do so; I know it well.

Michonneau; the old maid shrank and trembled under the influence of that strong Cisco 642-883 Exam Dumps Aws will, and collapsed into a Cisco 642-883 it Cisco 642-883 Topics exam Deploying Cisco Service Provider Network Routing (SPROUTE) time table Practise Questions chair.

On the opposite wall, at the further Cisco 642-883 Test Examination end of the graveled walk, a green marble arch was painted Cisco 642-883 kevin wallace once upon a time by a local artist, and in this semblance of a shrine a statue representing Cupid is installed; a Parisian Cupid, so blistered and disfigured that he looks like 100% Success Rate 642-883 Question Description Exam Study Materials a candidate for one of the adjacent hospitals, and might suggest an allegory to Cisco 642-883 Exam Dumps Released with Latest PDF Questions and VCE lovers of Cisco 642-883 it Cisco 642-883 Topics exam Deploying Cisco Service Provider Network Routing (SPROUTE) questions 642-883 Topics symbolism.

Her house known in the neighborhood as the Maison Vauquer receives men and women, old and young, Cisco 642-883 Braindumps Pdf and no Help you master the complex scenarios you will face on the exam 642-883 Certificate Sample Test word has ever been breathed Test Exam against her pespectable Cisco 642-883 latest dumps 2018 establishment; but, at the same time, it must be said Dumps Meaning Deploying Cisco Service Provider Network Routing (SPROUTE) Certification that Cisco 642-883 Easily To Pass as a matter of fact no Cisco 642-883 Exam Dumps With PDF and VCE Download (1-50) young woman Exam Dumps Reddit 642-883 Free Demo PDF Demo has been under her roof for thirty years, and that if a young man stays there for Cisco 642-883 How to Study for the any length of time it is a sure sign that his allowance must be of the slenderest.

Oh! this is cruel torture! I had just Cisco 642-883 brain Exam Material dump PDF contains Complete Pool of Questions and Answers given them each eight hundred thousand francs; they were bound to be civil to me Cisco 642-883 Exam Certification Dumps 100% Pass Rate Cisco 642-883 dumps free download after that, and their husbands too were civil.

On Sale In default of Cisco 642-883 Real Exam Q&A the pure and sacred love that fills a life, ambition may become something very noble, subduing to itself every thought of personal interest, and setting as the end the Cisco 642-883 Testing greatness, not of one man, but Exam Dumps Reddit 642-883 Past Exam Papers all the questions that you will face in the exam center of Cisco 642-883 Helpful Pass Easily with Cisco 642-883 Topics CCNP Service Provider Free a whole nation.

The servants have their orders, Cisco 642-883 Online Certification Exams and will not admit you.

Mme.

The womens dresses were faded, old fashioned, dyed and re dyed; they wore gloves Examcollection Braindumps Pdf == Dumps PDF 642-883 Topics Demo Free Download Cisco 642-883 Topics Practice Exam Latest Version Cisco 642-883 Topics Demo Free Download 642-883 Topics Dumps PDF. that were glazed with hard wear, much mended lace, Cisco 642-883 Great Dumps dingy ruffles, crumpled muslin fichus.

Tutorial Pdf It serves me right for wishing well to those Cisco 642-883 Simulation Exams Cisco 642-883 chinese dumps ladies at that poor mans expense.

Have you met Study Guide Pdf many men plucky enough when a comrade says, Let us bury a dead body! to go and do it without a word Cisco 642-883 which is a very common format found in all computers and gadgets or plaguing him by taking a high moral tone? High Pass Rate I have done it Cisco 642-883 Dumps Shop myself.

Pshaw! much Practice Exam Cisco First Time Update Cisco 642-883 Topics Dumps PDF Latest Version Cisco 642-883 Topics Practice Exam 642-883 Topics Demo Free Download. funnier things than THAT happen here! exclaimed Vautrin.

He took the Vicomtesses hand, kissed it, and went.

We women also Exam PDF And Exam VCE Simulator Cisco 642-883 it Cisco 642-883 Topics exam Deploying Cisco Service Provider Network Routing (SPROUTE) 2018 have our battles to fight.

She loved and she was loved; at any rate, she Cisco 642-883 Exam Description believed Cisco 642-883 Online Sale that she was loved; and what woman would not likewise have First Time Update believed Cisco 642-883 first-hand real Cisco 642-883 Topics exam Deploying Cisco Service Provider Network Routing (SPROUTE) study materials after seeing Rastignacs face and listening to the tones of his voice during that hour snatched under the Argus eyes of Free the Maison Practice Test Question Answers Dumps Vauquer? He had trampled on his conscience; he Cisco 642-883 Demo Download knew that he was doing wrong, and did Exam Syllabus it deliberately; he had Cisco 642-883 Measureup practice test for said to himself that a womans happiness should atone for this venial sin.

Vauquer took boarders who Dump came for their meals; but these externes usually only came to dinner, Cisco 642-883 Sale Online Stores for which they paid thirty francs a Pass Easily with 642-883 Topics Brain Dump Ensure Pass 642-883 Dumps Website Brain Dump month.

He sat at the foot of the Cisco 642-883 Exams Prep bed, and gazed at the face before him, so horribly changed that it was shocking to Best Certifications Dumps 642-883 Certification Exam Practice Test Question Answers Dumps see.

Tell her that CCNP Service Provider 642-883 Topics unless she comes, you will not love her any more.

Tis an effeminate age.

Do not be anxious about Examcollection Braindumps Pdf == Demo Free Download Cisco Dumps PDF Cisco 642-883 Topics Practice Exam Latest Version Cisco 642-883 Topics Practice Exam 642-883 Topics Practice Exam. him, she Exam Pdf Cisco 642-883 Exam Details 642-883 Topics <– and Topics said, however, as soon as Eugene began, our father has really Passing Score a strong constitution, but Exam Dumps Collection 642-883 High Exam Pass Rate 24 hours Pdf this morning we gave him Cisco 642-883 Real Questions Answers a shock.

My greatuncle, the Chevalier Brain Dumps 642-883 PDF Download Customers Testimonials de Rastignac, married the heiress of the Marcillac family.

Oh! my friend, do Free not marry; do not have children! You Cisco 642-883 Topics give them life; they give you your deathblow.

I shall have no peace until I know for certain that your fortune is secure.

de Nucingen to day, said [15-Dec-2018] Pass Cisco 642-883 Topics Exam by practicing with actual Cisco 642-883 Topics Exam questions. All 642-883 Topics Exam Brain Dumps are provided in PDF and Practice Exam formats. Eugene, addressing Goriot in an undertone.

Goriot has cost me Cisco 642-883 practice test ten francs already, the old scoundrel.

It was like balm to the law student, who was still smarting under the Duchess insolent scrutiny; she had looked at him as an auctioneer might look at some Cisco 642-883 Cisco 642-883 Exam VCE Exam Simulator article to appraise its value.

My Exams Material affairs seem to be in a promising way, said Eugene to Latest Exams Version 642-883 Computer Exam Exam PDF And Exam VCE Simulator himself.

What Deploying Cisco Service Provider Network Routing (SPROUTE) 642-883 does he go on living for? said Sylvie.

de Rochefides house.

Still, on the other hand, if you ask him for money, it [15-Dec-2018] Pass Cisco 642-883 Topics Exam by practicing with actual Cisco 642-883 Topics Exam questions. All 642-883 Topics Exam Brain Dumps are provided in PDF and Practice Exam formats. would put him on his guard, and he Cisco 642-883 Sale Online Sites is just the man to clear out without paying, and that would be an abominable sell.

The good man wiped his eyes, he was Deploying Cisco Service Provider Network Routing (SPROUTE) 642-883 crying.

She took his hand and held it Latest Dumps Update 642-883 High Exam Pass Rate 24 hours to her heart, a movement full of grace that expressed her deep gratitude.

You Cisco 642-883 For Sale have a few prejudices left; so you think that I am a scoundrel, do you? Well, M.

Just go Cisco 642-883 Exams Online away, M.

Exam Dumps Forum 642-883 Topics Exam Material.

New Update Posts

Cisco 100-105 Practice Exam

IASSC ICGB Practice Test

Cisco 400-051 Preparation Materials

Cloudera CCA-500 Demo

0 notes

Text

Simo Vehmas & Nick Watson, Moral wrongs, disadvantages, and disability: a critique of critical disability studies, 29 Disability & Society 638 (2014)

Abstract

Critical disability studies (CDS) has emerged as an approach to the study of disability over the last decade or so and has sought to present a challenge to the predominantly materialist line found in the more conventional disability studies approaches. In much the same way that the original development of the social model resulted in a necessary correction to the overly individualized accounts of disability that prevailed in much of the interpretive accounts which then dominated medical sociology, so too has CDS challenged the materialist line of disability studies. In this paper we review the ideas behind this development and analyse and critique some of its key ideas. The paper starts with a brief overview of the main theorists and approaches contained within CDS and then moves on to normative issues; namely, to the ethical and political applicability of CDS.

Points of interest

This article examines and critiques the ideas found within critical disability studies (CDS).

The article argues that the accounts offered by CDS do not engage fully with the key ethical and political issues faced by disabled people.

CDS does not examine how things ought to be for disabled people in terms of right and wrong, good and bad. Because of this omission it is not able to provide a good political or theoretical framework through which to discuss disability.

The paper argues that an examination of disability must involve an engagement with moral and political issues, and must be sensitive to individual experiences as well as the social, material and economic circumstances.

Introduction: critical disability studies

Critical disability studies (CDS) has emerged as an approach to the study of disability over the last decade or so and has sought to present a challenge to the predominantly Marxist/materialist line found in the more conventional disability studies approaches. The result of this development has been the production of some very interesting and worthwhile research and theorization around disability. In much the same way that the original development of the social model resulted in a necessary correction to the overly individualized accounts of disability that prevailed in much of the interpretive accounts which then dominated medical sociology, so too has CDS challenged the materialist line of disability studies.

The main aim of CDS is to deconstruct ideas about disability and to explore how they have come to dominate our approaches to the subject and how the ideologies that surround disability have been constructed. It is about unsettling ideas about disability and in so doing shaking up some of our assumptions about disability and critically engaging with the categories used to construct the ‘disability problem’. CDS seeks to deconstruct the binary distinctions that it claims are used to create difference and hierarchies and obscure connections between disabled and nondisabled people (Shildrick 2012Shildrick, M. 2012. “Critical Disability Studies: Rethinking the Conventions for the Age of Postmodernity.” In Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, edited by N. Watson, A.Roulstone and C. Thomas, 30–41. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]). Whilst there are many different theorists drawn upon by the various scholars writing in this paradigm, most of them can be loosely defined as post-structural anti-dualists.

Mariain Hill Scott (nee Corker) was one of the first academics from within disability studies to promote the ideas that laid the foundations of what has become CDS (Corker 1998Corker, M. 1999. “Differences, Conflations and Foundations: The Limits to ‘accurate’ Theoretical Representation of Disabled people’s Experiences.” Disability & Society 14 (5): 627–642.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar], 1999Corker, M. 1998. Deaf and Disabled or Deafness Disabled. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]). Drawing on the ideas of Judith Butler, she argued for a critical analysis of the terms used to define disability and impairment. She drew on socio-linguistic theory, in particular the work of Derrida, to argue that the project for disability theory should be to contest meanings, arguing that binary opposites, in which one term is given precedence over the other, exist so as to ‘deceive us into valuing one side of the dichotomy more than the other’ (Corker 1999Corker, M. 1999. “Differences, Conflations and Foundations: The Limits to ‘accurate’ Theoretical Representation of Disabled people’s Experiences.” Disability & Society 14 (5): 627–642.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar], 638). Her contention was that through deconstructing such meanings and breaking down binary opposites the concept of disability and impairment could be conceptualized so as to present the problems faced by disabled people as one that arose in the relationship between impairment and oppression, the former acting as an unexamined biological foundation for the latter. This contrasts with a social model analysis that presents disability as the collective experience of oppression. Corker argued for the development of a social space where identities could be formed and fashioned free from the normative constraints imposed by bipolar norms of disabled/non-disabled.

These ideas have been taken up by many others and further developed both in the United Kingdom and the United States and elsewhere (for example, Campbell 2009aCampbell, F. K. 2009a. Contours of Ableism. Basingstoke: Macmillan.10.1057/9780230245181[Crossref], [Google Scholar]; Goodley 2011Goodley, D. 2011. Disability Studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]; McRuer 2010; Shildrick 2012Shildrick, M. 2012. “Critical Disability Studies: Rethinking the Conventions for the Age of Postmodernity.” In Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, edited by N. Watson, A.Roulstone and C. Thomas, 30–41. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]). They, like Corker, have drawn on the ideas of Foucault, Butler and Derrida and have sought to unpack disability and impairment in terms of knowledge and power to unsettle ideas about both disability and normality as well as some of the key theories and assumptions that have been central to disability studies. Meekosha and Shuttleworth (2009Meekosha, H., and R. Shuttleworth. 2009. “What’s So ‘critical’ about Critical Disability Studies?” Australian Journal of Human Rights15 (1): 47–75.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Google Scholar]) locate the origins of this development with a general concern about the binary nature of disability studies and the resulting impairment/disablement divide, a by-product, they argue, of the social model’s simplistic materialist focus, both points made by Corker. Importantly they also cite the emergence of an interest in disability within the arts and humanities, particularly in the United States where much of the drive for this new approach to disability was originally located. In addition, Meekosha and Shuttleworth suggest that CDS marked an attempt by theorists to distance themselves from policy-makers and service providers who they felt had sought to co-opt the social model and use it for their own ends.

The use of what Shildrick (2012Shildrick, M. 2012. “Critical Disability Studies: Rethinking the Conventions for the Age of Postmodernity.” In Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, edited by N. Watson, A.Roulstone and C. Thomas, 30–41. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]), following Butler and Foucault, terms critique has also been central. Through the employment of critique, CDS seeks to examine not just disability but also its genealogy, and the methodologies that have been applied in its study; it aims to contest accepted ‘truths’ and ideas, of disability and of impairment, and through this of disability studies itself. As Foucault argued:

A critique is not a matter of saying things are not right as they are. It is a matter of pointing out on what kinds of assumptions, what kinds of familiar, unchallenged, unconsidered modes of thought the practices that we accept rest. (1997Foucault, M. 1997. “What is Critique?” In The Politics of Truth, edited by S. Lorringer and L.Hockoth, 41–82. New York: Semiotexte. [Google Scholar], 155)

CDS then sees as one its primary goals an attempt to not only breakdown the impaired/non-impaired dualism, but to explore how these dualisms have obscured connections between people with and without impairment and in so doing present the categories as fluid and unstable. The aim is to create a renewed, more reflexive and theoretically cautious approach.

Differences between disabled and non-disabled people are described as being socially produced, and it is also argued that these differences are constructed for a political reason; to maintain dominance (Goodley 2011Goodley, D. 2011. Disability Studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. London: Sage. [Google Scholar], 113). The standpoint of the privileged and powerful, in this case non-disabled people, has become the norm, and others are seen as deviant and inferior (Campbell 2009aCampbell, F. K. 2009a. Contours of Ableism. Basingstoke: Macmillan.10.1057/9780230245181[Crossref], [Google Scholar]). The aim is that through employing concepts such as ableism rather than the more typical disablism, the negative stereotypes and cultural values that surround disability and impairment can be challenged and focused away from the person with impairment. As Davis writes: ‘The problem is not the person with disabilities; the problem is the way that normalcy is constructed to create the “problem” of the disabled person’ (2010Davis, L. 2010. “Constructing Normalcy.” In The Disability Studies Reader 3rd ed., edited by L.Davis, 3–20. London: Routledge [Google Scholar], 9).

Critical disability studies and hidden ethical judgements

The ideas developed within CDS draw heavily on concepts developed in other areas of difference including ethnicity, sexuality and gender. Whilst it is not simply about conflating different approaches together with that of disability studies, the case for similarities are readily made (Shildrick 2012Shildrick, M. 2012. “Critical Disability Studies: Rethinking the Conventions for the Age of Postmodernity.” In Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, edited by N. Watson, A.Roulstone and C. Thomas, 30–41. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]). McCruer (2010McCruer, R. 2010. “Compulsory Ablebodiedness and Queer/Disabled Existence.” In The Disability Studies Reader. 3rd ed., edited by L. Davis, 383–392. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]), for example, drawing on the ideas of Judith Butler juxtaposes compulsory heterosexuality with compulsory ablebodiedness, arguing that privileging heterosexuality and ablebodiedness acts to the detriment of others. The argument is that by disrupting the categories disabled/non-disabled, the discrimination experienced by disabled people can be challenged.

This attempt at what Sayer (2011Sayer, A. 2011. Why Things Matter to People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511734779[Crossref], [Google Scholar]) has called normative disorientation found in much of the theorizing around ableism creates problems. For example, how can we discuss or debate prevention when a feature of ableism is described as a ‘belief that impairment (irrespective of “type”) is inherently negative which should, if the opportunity presents itself, be ameliorated, cured or indeed eliminated’ (Campbell 2009bCampbell, F. K. 2009b. “Disability Harms Exploring Internalized Ableism?” In Disability: Insights from across Fields and around the World. vol. I, edited by C. Marshall, E. Kendalland R. Gover, 19–34. Westport, CT: Praeger Press. [Google Scholar], 23)? Is the promotion of the use of folic acid before and during pregnancy based on an anti-disablist or perhaps ableist viewpoint; and if so, should CDS be campaigning against those who seek to promote these views? This gap is acknowledged by Meekosha (2011Meekosha, H. 2011. “Decolonising Disability: Thinking and Acting Globally.” Disability & Society 26 (6): 667–682.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]), but it has not been examined or unpacked. Whilst we may be accused here of constructing a ‘straw person argument’ it is consistent with Campbell’s claim.

This challenge to normativity, of what is good or bad, or right or wrong, characterizes much of the CDS literature. Whilst CDS often makes normative judgements about policies or about the current understanding of disability or how contemporary social organization is morally wrong, it offers no evaluative arguments on impairments or on the implications of living with an impairment. Shildrick (2012Shildrick, M. 2012. “Critical Disability Studies: Rethinking the Conventions for the Age of Postmodernity.” In Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, edited by N. Watson, A.Roulstone and C. Thomas, 30–41. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar], 40), for example, has argued that ‘all bodies are unstable and vulnerable’ and that there is ‘no single acceptable mode of embodiment’. Shildrick attempts a move to an ethical realm by posing what she describes as ‘an important ethical question: how can we engage with morphological difference that is not reducible to the binary of either sameness or difference?’ And, in line with this rather leading question, she continues: ‘If we are to have an ethically responsible encounter with corporeal difference, then, we need a strategy of queering the norms of embodiment, a commitment to deconstruct the apparent stability of distinct and bounded categories’ (Shildrick 2012Shildrick, M. 2012. “Critical Disability Studies: Rethinking the Conventions for the Age of Postmodernity.” In Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, edited by N. Watson, A.Roulstone and C. Thomas, 30–41. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar], 40). In Shildrick’s view, any strategy, political arrangement, or ethical conceptualization that is based on a group identity built upon a binary distinction or difference, is ethically wrong. This is an interesting suggestion but unfortunately Shildrick does not provide any ethical argument to support it or a practical example of how it may be enacted.

It is, as Shildrick argues, safe to suggest that there is no ‘single acceptable mode of embodiment’, but at the same time it seems equally safe to suggest that there are a lot of people who would argue that some forms of embodiment are preferential to others. Seeing impairments as acceptable forms of human diversity is not the same as seeing them as neutral or insignificant. When people say that some forms of embodiment are preferential to others, they are ultimately referring to ideas about human well-being. In other words, one reason why people generally prefer not to have impairments is ethical; they believe that some impairments may in and of themselves prevent people from acting and moving as they wish, from doing valued activities, or faring well in general. Thomas (1999Thomas, C. 1999. Female Forms: Experiencing and Understanding Disability. Buckingham: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]) coined the term ‘impairment effects’ to define these limitations and to separate them from those that arise from disablement. CDS is normative as well, albeit its normative focus is on social factors instead of individuals’ abilities. CDS, like the social model, contains a strong normative dimension that implies what is right or wrong as regards social arrangements, but neither model takes a clear normative approach to the lived, embodied and visceral experiences of having an impairment (Vehmas 2004Vehmas, S. 2004. “Ethical Analysis of the Concept of Disability.” Mental Retardation 42 (3): 209–222.10.1352/0047-6765(2004)42<209:EAOTCO>2.0.CO;2[Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar]).

Human beings are dialogical beings and the significance of disability or impairment and their impact on well-being will tend to be comparative. As Sayer argues: ‘we measure ourselves not so much against absolute standards but against what others are like, particularly those with whom we associate the most’ (2011Sayer, A. 2011. Why Things Matter to People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511734779[Crossref], [Google Scholar], 122). Evaluative judgements in relation to the individual experience of both disability and impairment are important. If we are to properly understand social phenomena, such as disability, we have to recognize their normative dimensions and the values attached to them. Value-laden statements, as Sayer (2011Sayer, A. 2011. Why Things Matter to People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511734779[Crossref], [Google Scholar]) argues, can strengthen the descriptive adequacy of accounts. Sayer demonstrates this by using the example of the Holocaust. This, he says, can be represented in two ways: ‘thousands died in the Nazi concentration camps’ and ‘thousands were systematically exterminated in the Nazi concentration camps’. The latter sentence is not only more value-laden than the first, but more accurate as well (Sayer 2011Sayer, A. 2011. Why Things Matter to People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511734779[Crossref], [Google Scholar], 45). We would argue that talking about ableism, disablism or oppression does not make sense without reference to normative judgements about people’s well-being, as without such a discussion only a partial picture will emerge. The same may also apply to judgements about fair social arrangements.

CDS does not engage with ethical issues to do with the role of impairment and disability in people’s well-being and the pragmatic and mundane issues of day-to-day living. Imagine, for example, a pregnant woman who has agreed, possibly with very little thought, to the routine of prenatal diagnostics, and who has been informed that the foetus she is carrying has Tay-Sachs disease. She now has to make the decision over whether to terminate the pregnancy or carry it to term. The value judgements that surround Tay-Sachs include the fact that it will cause pain and suffering to the child and he or she will probably die before the age of four. These are morally relevant considerations to the mother. Whilst CDS would probably guide her to confront ableist assumptions and challenge her beliefs about the condition, considerations having to do with pain and suffering are nevertheless morally significant. The way people see things, and the language that is used to describe certain conditions, can affect how they react to them, but freeing oneself from ableist assumptions may not in some cases be enough. There may be insurmountable realities attached to some impairments where parents feel that their personal and social circumstances would not enable them to provide the child or themselves with a satisfactory life (Vehmas 2003Vehmas, S. 2003. “Live and Let Die? Disability in Bioethics.” New Review of Bioethics 1 (1): 127–157.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Google Scholar]).

Impairment sometimes produces practical, difficult ethical choices and we need more concrete viewpoints than the ideas provided through ableism, which offers very little practical moral guidance. It is questionable whether the notion of ableism would help the parents in deciding whether to have a child who has a degenerative condition that results in early death. Campbell (2009aCampbell, F. K. 2009a. Contours of Ableism. Basingstoke: Macmillan.10.1057/9780230245181[Crossref], [Google Scholar], 39, 149 and 159), for example, discusses arguments about impairments as harmful conditions, the ethics of external bodily transplants as well as wrongful birth and life court cases (whether life with an impairment is preferable to non-existence), and how ableism impacts on discourse around these issues. Whilst her analysis of such ableist discourses suggests ethical judgements, she provides no arguments or conclusions as to whether, for example, external bodily transplants are ethically wrong or whether impairment may or may not constitute a moral harm.

Under the anti-dualistic stance adopted by CDS, even the well-being/ill-being dualism becomes an arbitrary and nonsensical construct. Under ableism it can be constructed as merely maintaining the dominance of those seemingly faring well (supposedly, ‘non-disabled’ people), and labels those faring less well as having lesser value.

There may not be a clear answer to what constitutes human well-being or flourishing, but in general we can and we need to agree about some necessary elements required for well-being. Also, as moral agents we have an obligation to make judgements about people’s well-being and act in ways that their well-being is enhanced (Eshleman 2009Eshleman, A. 2009. “Moral Responsibility.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2009 Edition), edited by E. N. Zalta, <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2009/entries/moral-responsibility/> [Google Scholar]). This is why we have, for example, coronary heart disease prevention programmes because the possible death or associated health problems are seen as harms. Possibly these policies are based on ableist perspective, but if that is the case then the normative use of ableism is null; eradicating supposedly ableist enterprises such as coronary heart disease prevention would be an example of reductio ad absurdum. Denying some aspects of well-being are so clear that their denial would be absurd, and simply morally wrong.

CDS raises ethical issues and insinuates normative judgements but does not provide supporting ethical arguments. This is a way of shirking from intellectual and ethical responsibility to provide sound arguments and conceptual tools for ethical decision-making that would benefit disabled people. If we are to describe disability, disablism, and oppression properly, we have to explicate the moral and political wrong related to these phenomena. Whilst CDS has produced useful analyses, for example, of the cultural reproduction of disability, it needs to engage more closely with the evaluative issues inherently related to disability. As Sayer has argued (against Foucault):

while one could hardly disagree that we should seek to uncover the hidden and unconsidered ideas on which practices are based, I would argue that critique is indeed exactly about identifying what things ‘are not right as they are’, and why. (Sayer 2011Sayer, A. 2011. Why Things Matter to People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511734779[Crossref], [Google Scholar], 244)

By settling almost exclusively to analyses of ableism without engaging properly with the ethical issues involved, CDS analyses are deficient. The moral wrongs related to disablism or ableism are matters of great concern to disabled people, and CDS should in its own part take the responsibility of remedying current wrongs disabled people suffer from.

Disability and disadvantage

In the final sections of this paper, we will discuss CDS in the light of the politics of disability. We will challenge its key ideas and their political use. We argue that deconstructing categories of difference is neither necessary nor desirable in the pursuit of justice for disabled people. Abolishing oppression requires recognition of the various ways different groups of people are marginalized and oppressed, and to do this requires more than an analysis of their categorization and their historical genealogy.

Tackling disadvantage has been the main theoretical and political aim of disability studies and from its first inception academics such as Oliver, Barnes and Finkelstein were interested in documenting the disadvantage experienced by disabled people and how it can be prevented or challenged. It shares with political philosophy a desire to identify and critique discrimination associated with the ill-treatment of disabled people and their subordination (Wolff and De-Shalit 2007Wolff, J., and A. De-Shalit. 2007. Disadvantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199278268.001.0001[Crossref], [Google Scholar], 3). Improving the position of the worst off is generally seen, at least in an egalitarian outlook, as a matter of justice because people’s social status and well-being is inevitably related to the way society is organized. In order to create fair social responses to disadvantage, we have to have a common understanding about disadvantage, and a reasonable (non-arbitrary) way of comparing disadvantages and correcting them.